pneumatic chemistry on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In the

history of science

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient history, ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural science, natural, social science, social, and formal science, formal. Pr ...

, pneumatic chemistry is an area of scientific research

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has been referred to while doing science since at least the 17th century. Historically, it was developed through the centuries from the ancient and medieval world. The ...

of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and early nineteenth centuries. Important goals of this work were the understanding of the physical properties of gases and how they relate to chemical reaction

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the chemistry, chemical transformation of one set of chemical substances to another. When chemical reactions occur, the atoms are rearranged and the reaction is accompanied by an Gibbs free energy, ...

s and, ultimately, the composition of matter

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic pa ...

. The rise of phlogiston theory

The phlogiston theory, a superseded scientific theory, postulated the existence of a fire-like element dubbed phlogiston () contained within combustible bodies and released during combustion. The name comes from the Ancient Greek (''burnin ...

, and its replacement by a new theory after the discovery of oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

as a gaseous component of the Earth atmosphere

The atmosphere of Earth is composed of a layer of gas mixture that surrounds the Earth's planetary surface (both lands and oceans), known collectively as air, with variable quantities of suspended aerosols and particulates (which create weather ...

and a chemical reagent

In chemistry, a reagent ( ) or analytical reagent is a substance or compound added to a system to cause a chemical reaction, or test if one occurs. The terms ''reactant'' and ''reagent'' are often used interchangeably, but reactant specifies a ...

participating in the combustion

Combustion, or burning, is a high-temperature exothermic redox chemical reaction between a fuel (the reductant) and an oxidant, usually atmospheric oxygen, that produces oxidized, often gaseous products, in a mixture termed as smoke. Combustion ...

reactions, were addressed in the era of pneumatic chemistry.

Air as a reagent

In the eighteenth century, as the field ofchemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

was evolving from alchemy

Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

, a field of the natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

was created around the idea of air as a reagent

In chemistry, a reagent ( ) or analytical reagent is a substance or compound added to a system to cause a chemical reaction, or test if one occurs. The terms ''reactant'' and ''reagent'' are often used interchangeably, but reactant specifies a ...

. Before this, air was primarily considered a static substance that would not react and simply existed. However, as Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier ( ; ; 26 August 17438 May 1794),

CNRS (

The pneumatic trough, while integral throughout the eighteenth century, was modified several times to collect gases more efficiently or just to collect more gas. For example, Cavendish noted that the amount of fixed air that was given off by a reaction was not entirely present above the water; this meant that fixed water was absorbing some of this air, and could not be used quantitatively to collect that particular air. So, he replaced the water in the trough with mercury instead, in which most airs were not soluble. By doing so, he could not only collect all airs given off by a reaction, but he could also determine the solubility of airs in water, beginning a new area of research for pneumatic chemists. While this was the major adaptation of the trough in the eighteenth century, several minor changes were made before and after this substitution of mercury for water, such as adding a shelf to rest the head on while gas collection occurred. This shelf would also allow for less conventional heads to be used, such as Brownrigg's animal

The pneumatic trough, while integral throughout the eighteenth century, was modified several times to collect gases more efficiently or just to collect more gas. For example, Cavendish noted that the amount of fixed air that was given off by a reaction was not entirely present above the water; this meant that fixed water was absorbing some of this air, and could not be used quantitatively to collect that particular air. So, he replaced the water in the trough with mercury instead, in which most airs were not soluble. By doing so, he could not only collect all airs given off by a reaction, but he could also determine the solubility of airs in water, beginning a new area of research for pneumatic chemists. While this was the major adaptation of the trough in the eighteenth century, several minor changes were made before and after this substitution of mercury for water, such as adding a shelf to rest the head on while gas collection occurred. This shelf would also allow for less conventional heads to be used, such as Brownrigg's animal

CNRS (

Stephen Hales

Stephen Hales (17 September 16774 January 1761) was an English clergyman who made major contributions to a range of scientific fields including botany, pneumatic chemistry and physiology. He was the first person to measure blood pressure. He al ...

. These reactions would give off different "airs" as chemists would call them, and these different airs contained more simple substances. Until Lavoisier, these airs were considered separate entities with different properties; Lavoisier was responsible largely for changing the idea of air as being constituted by these different airs that his contemporaries and earlier chemists had discovered.

This study of gases was brought about by Hales with the invention of the pneumatic trough, an instrument capable of collecting the gas given off by reactions with reproducible results. The term ''gas'' was coined by J. B. van Helmont, in the early seventeenth century. This term was derived from the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

word ''χάος, chaos

Chaos or CHAOS may refer to:

Science, technology, and astronomy

* '' Chaos: Making a New Science'', a 1987 book by James Gleick

* Chaos (company), a Bulgarian rendering and simulation software company

* ''Chaos'' (genus), a genus of amoebae

* ...

'', as a result of his inability to collect properly the substances given off by reactions, as he was the first natural philosopher to make an attempt at carefully studying the third type of matter. However, it was not until Lavoisier performed his research in the eighteenth century that the word was used universally by scientists as a replacement for ''airs''.

Van Helmont (1579 – 1644) is sometimes considered the founder of pneumatic chemistry, as he was the first natural philosopher to take an interest in air as a reagent. Alessandro Volta

Alessandro Giuseppe Antonio Anastasio Volta (, ; ; 18 February 1745 – 5 March 1827) was an Italian chemist and physicist who was a pioneer of electricity and Power (physics), power, and is credited as the inventor of the electric battery a ...

began investigating pneumatic chemistry in 1776 and argued that there were different types of inflammable air based on experiments on marsh gases. Pneumatic chemists credited with discovering chemical elements include Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, Unitarian, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher, English Separatist, separatist theologian, Linguist, grammarian, multi-subject educator and Classical libera ...

, Henry Cavendish

Henry Cavendish ( ; 10 October 1731 – 24 February 1810) was an English experimental and theoretical chemist and physicist. He is noted for his discovery of hydrogen, which he termed "inflammable air". He described the density of inflammable a ...

, Joseph Black, Daniel Rutherford, and Carl Scheele. Other individuals who investigated gases during this period include Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, Alchemy, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the foun ...

, Stephen Hales

Stephen Hales (17 September 16774 January 1761) was an English clergyman who made major contributions to a range of scientific fields including botany, pneumatic chemistry and physiology. He was the first person to measure blood pressure. He al ...

, William Brownrigg, Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier ( ; ; 26 August 17438 May 1794), When reduced without charcoal, it gave off an air which supported respiration and combustion in an enhanced way. He concluded that this was just a pure form of common air and that i ...

, Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac

Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac ( , ; ; 6 December 1778 – 9 May 1850) was a French chemist and physicist. He is known mostly for his discovery that water is made of two parts hydrogen and one part oxygen by volume (with Alexander von Humboldt), f ...

, and John Dalton

John Dalton (; 5 or 6 September 1766 – 27 July 1844) was an English chemist, physicist and meteorologist. He introduced the atomic theory into chemistry. He also researched Color blindness, colour blindness; as a result, the umbrella term ...

.

History

Chemical revolution

"In the years between 1770 and 1785, chemists all over Europe started catching, isolating, and weighing different gasses." The pneumatic trough was integral to the work with gases (or, as contemporary chemists called them, airs). Work done by Joseph Black, Joseph Priestley, Herman Boerhaave, and Henry Cavendish revolved largely around the use of the instrument, allowing them to collect airs given off by different chemical reactions and combustion analyses. Their work led to the discovery of many types of airs, such as dephlogisticated air (discovered by Joseph Priestley). Moreover, the chemistry of airs was not limited to combustion analyses. During the eighteenth century, many chymists used the discovery of airs as a new path for exploring old problems, with one example being the field of medicinal chemistry. One particular Englishman, James Watt, began to take the idea of airs and use them in what was referred to as ''pneumatic therapy'', or the use of airs to make laboratories more workable with fresh airs and also aid patients with different illnesses, with varying degrees of success. Most human experimentation done was performed on the chymists themselves, as they believed that self-experimentation was a necessary part or progressing the field.Contributors

James Watt

James Watt

James Watt (; 30 January 1736 (19 January 1736 OS) – 25 August 1819) was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist who improved on Thomas Newcomen's 1712 Newcomen steam engine with his Watt steam engine in 1776, which was f ...

's research in pneumatic chemistry involved the use of inflammable ( H2) and dephlogisticated ( O2) airs to create water

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance. It is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known liv ...

. In 1783, James Watt showed that water was composed of inflammable and dephlogisticated airs, and that the masses of gases before combustion were exactly equal to the mass of water after combustion. Until this point, water was viewed as a fundamental element rather than a compound. James Watt also sought to explore the use of different " factitious airs" such as hydrocarbonate in medicinal treatments as "pneumatic therapy" by collaborating with Dr. Thomas Beddoes

Thomas Beddoes (13 April 176024 December 1808) was an English physician and scientific writer. He was born in Shifnal, Shropshire and died in Bristol fifteen years after opening his medical practice there. He was a reforming practitioner and te ...

and Erasmus Darwin to treat Jessie Watt, his daughter suffering from tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

, using fixed air.

Joseph Black

Joseph Black was a chemist who took interest in the pneumatic field after studying under William Cullen. He was first interested in the topic of magnesia alba, ormagnesium carbonate

Magnesium carbonate, (archaic name magnesia alba), is an inorganic salt that is a colourless or white solid. Several hydrated and Base (chemistry), basic forms of magnesium carbonate also exist as minerals.

Forms

The most common magnesium car ...

(MgCO3), and limestone

Limestone is a type of carbonate rock, carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material Lime (material), lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different Polymorphism (materials science) ...

, or calcium carbonate (CaCO3), and wrote a dissertation called "''De humore acido a cibis orto, et magnesia alba''" on the properties of both. His experiments on magnesium carbonate led him to discover that fixed air, or carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

(CO2), was being given off during reactions with various chemicals, including breathing

Breathing (spiration or ventilation) is the rhythmical process of moving air into ( inhalation) and out of ( exhalation) the lungs to facilitate gas exchange with the internal environment, mostly to flush out carbon dioxide and bring in oxy ...

. Despite him never using the pneumatic trough or other instrumentation invented to collect and analyze the airs, his inferences led to more research into fixed air instead of common air, with the trough actually being used.

Gaseous ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic chemical compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the chemical formula, formula . A Binary compounds of hydrogen, stable binary hydride and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinctive pu ...

was first isolated by Joseph Black in 1756 by reacting ''sal ammoniac'' (ammonium chloride

Ammonium chloride is an inorganic chemical compound with the chemical formula , also written as . It is an ammonium salt of hydrogen chloride. It consists of ammonium cations and chloride anions . It is a white crystalline salt (chemistry), sal ...

) with ''calcined magnesia'' (magnesium oxide

Magnesium oxide (MgO), or magnesia, is a white hygroscopic solid mineral that occurs naturally as periclase and is a source of magnesium (see also oxide). It has an empirical formula of MgO and consists of a lattice of Mg2+ ions and O2− ions ...

). It was isolated again by Peter Woulfe in 1767, by Carl Wilhelm Scheele

Carl Wilhelm Scheele (, ; 9 December 1742 – 21 May 1786) was a Swedish Pomerania, German-Swedish pharmaceutical chemist.

Scheele discovered oxygen (although Joseph Priestley published his findings first), and identified the elements molybd ...

in 1770

Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, Unitarian, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher, English Separatist, separatist theologian, Linguist, grammarian, multi-subject educator and Classical libera ...

, in ''Observations on different kinds of air,'' was one of the first people to describe air as being composed of different states of matter, and not as one element. Priestley elaborated on the notions of fixed air (CO2), mephitic air and inflammable air to include "inflammable nitrous air," " vitriolic acid air," " alkaline air" and " dephlogisticated air". Priestley also described the process of respiration in terms of phlogiston theory

The phlogiston theory, a superseded scientific theory, postulated the existence of a fire-like element dubbed phlogiston () contained within combustible bodies and released during combustion. The name comes from the Ancient Greek (''burnin ...

. Priestley also established a process for treating scurvy

Scurvy is a deficiency disease (state of malnutrition) resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, fatigue, and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, anemia, decreased red blood cells, gum d ...

and other ailments using fixed air in his ''Directions for impregnating water with fixed air.'' Priestley's work on pneumatic chemistry had an influence on his natural world views. His belief in an "aerial economy" stemmed from his belief in "dephlogisticated air" being the purest type of air and that phlogiston and combustion were at the heart of nature.

Joseph Priestley chiefly researched with the pneumatic trough, but he was responsible for collecting several new water-soluble

In chemistry, solubility is the ability of a substance, the solute, to form a solution with another substance, the solvent. Insolubility is the opposite property, the inability of the solute to form such a solution.

The extent of the solub ...

airs. This was achieved primarily by his substitution of mercury for water, and implementing a shelf under the head for increased stability, capitalizing on the idea Cavendish proposed and popularizing the mercury pneumatic trough.

Herman Boerhaave

While not credited for direct research into the field of pneumatic chemistry, Boerhaave (teacher, researcher, and scholar) did publish the ''Elementa Chimiae'' in 1727. This treatise included support for Hales' work and also elaborated upon the idea of airs. Despite not publishing his own research, this section on airs in the ''Elementa Chimiae'' was cited by many other contemporaries and contained much of the current knowledge of the properties of airs. Boerhaave is also credited with adding to the world of chemical thermometry through his work with Daniel Fahrenheit, also discussed in ''Elementa Chimiae.''Henry Cavendish

Henry Cavendish

Henry Cavendish ( ; 10 October 1731 – 24 February 1810) was an English experimental and theoretical chemist and physicist. He is noted for his discovery of hydrogen, which he termed "inflammable air". He described the density of inflammable a ...

, despite not being the first to replace water in the trough with mercury, was among the first to observe that fixed air was insoluble over mercury and therefore could be collected more efficiently using the adapted instrument. He also characterized fixed air ( CO2) and inflammable air ( H2). Inflammable air was one of the first gases isolated and discovered using the pneumatic trough. However, he did not exploit his own idea to its limit, and therefore did not use the mercury pneumatic trough to its full extent. Cavendish is credited with nearly correctly analyzing the content of gases in the atmosphere. Cavendish also showed that inflammable air and atmospheric air could be combined and heated to produce water in 1784.

Stephen Hales

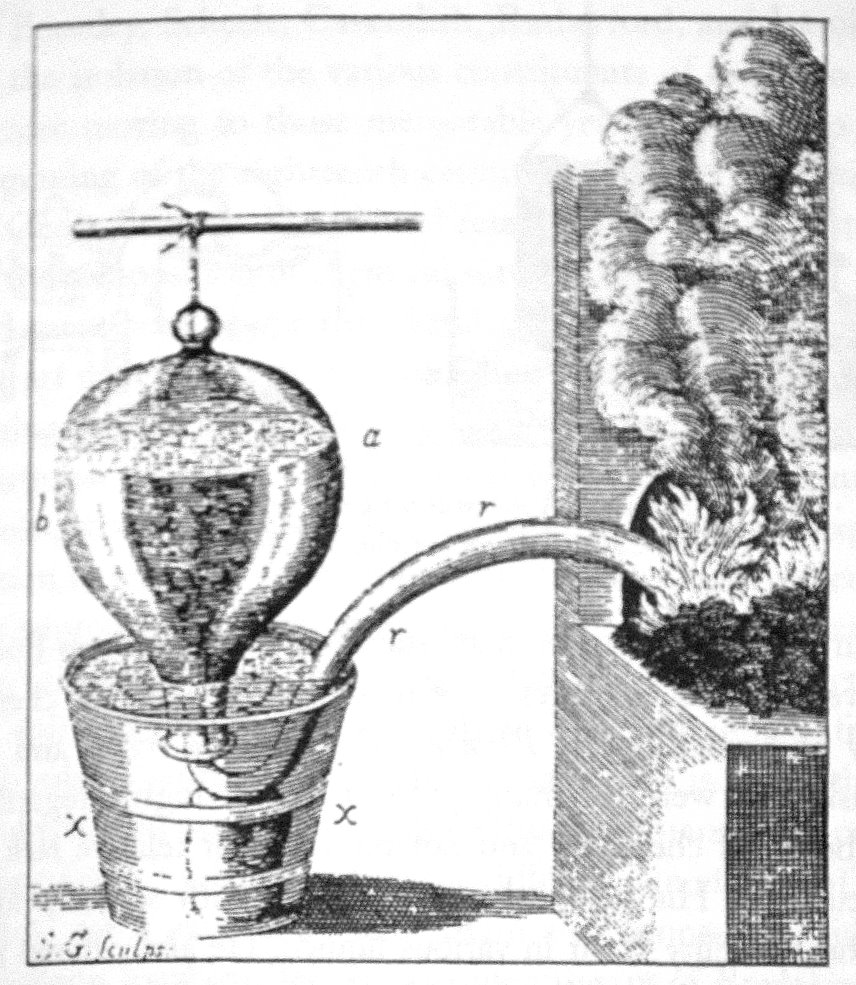

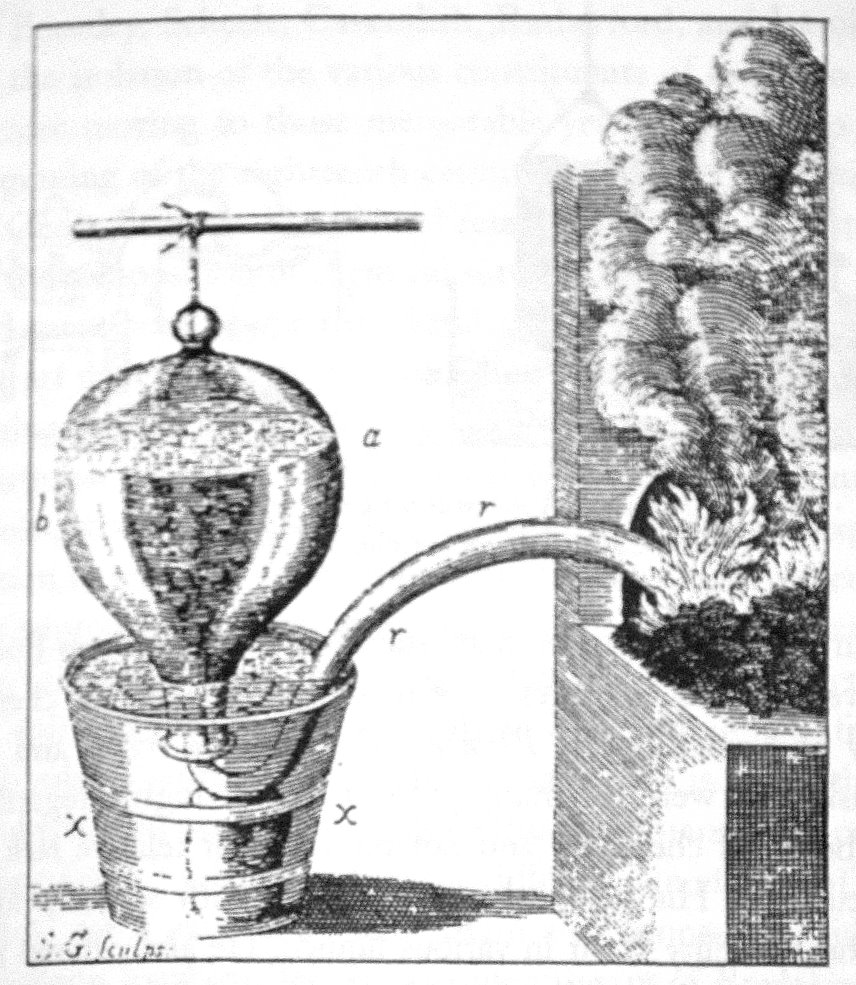

In the eighteenth century, with the rise of combustion analysis in chemistry,Stephen Hales

Stephen Hales (17 September 16774 January 1761) was an English clergyman who made major contributions to a range of scientific fields including botany, pneumatic chemistry and physiology. He was the first person to measure blood pressure. He al ...

invented the pneumatic trough in order to collect gases from the samples of matter he used; while uninterested in the properties of the gases he collected, he wanted to explore how much gas was given off from the materials he burned or let ferment

Fermentation is a type of anaerobic metabolism which harnesses the redox potential of the reactants to make adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and organic end products. Organic compound, Organic molecules, such as glucose or other sugars, are Catabo ...

. Hales was successful in preventing the air from losing its "elasticity," i.e. preventing it from experiencing a loss in volume, by bubbling the gas through water, and therefore dissolving the soluble gases.

After the invention of the pneumatic trough, Stephen Hales continued his research into the different airs, and performed many Newtonian analyses of the various properties of them. He published his book ''Vegetable Staticks'' in 1727, which had a profound impact on the field of pneumatic chemistry, as many researchers cited this in their academic papers. In ''Vegetable Staticks'', Hales not only introduced his trough, but also published the results he obtained from the collected air, such as the elasticity and composition of airs along with their ability to mix with others.

Instrumentation

Pneumatic trough

Stephen Hales

Stephen Hales (17 September 16774 January 1761) was an English clergyman who made major contributions to a range of scientific fields including botany, pneumatic chemistry and physiology. He was the first person to measure blood pressure. He al ...

, called the creator of pneumatic chemistry, created the pneumatic trough in 1727. This instrument was widely used by many chemists to explore the properties of different airs, such as what was called inflammable air (what is modernly called hydrogen). Lavoisier used this in addition to his gasometer to collect gases and analyze them, aiding him in creating his list of simple substances.

The pneumatic trough, while integral throughout the eighteenth century, was modified several times to collect gases more efficiently or just to collect more gas. For example, Cavendish noted that the amount of fixed air that was given off by a reaction was not entirely present above the water; this meant that fixed water was absorbing some of this air, and could not be used quantitatively to collect that particular air. So, he replaced the water in the trough with mercury instead, in which most airs were not soluble. By doing so, he could not only collect all airs given off by a reaction, but he could also determine the solubility of airs in water, beginning a new area of research for pneumatic chemists. While this was the major adaptation of the trough in the eighteenth century, several minor changes were made before and after this substitution of mercury for water, such as adding a shelf to rest the head on while gas collection occurred. This shelf would also allow for less conventional heads to be used, such as Brownrigg's animal

The pneumatic trough, while integral throughout the eighteenth century, was modified several times to collect gases more efficiently or just to collect more gas. For example, Cavendish noted that the amount of fixed air that was given off by a reaction was not entirely present above the water; this meant that fixed water was absorbing some of this air, and could not be used quantitatively to collect that particular air. So, he replaced the water in the trough with mercury instead, in which most airs were not soluble. By doing so, he could not only collect all airs given off by a reaction, but he could also determine the solubility of airs in water, beginning a new area of research for pneumatic chemists. While this was the major adaptation of the trough in the eighteenth century, several minor changes were made before and after this substitution of mercury for water, such as adding a shelf to rest the head on while gas collection occurred. This shelf would also allow for less conventional heads to be used, such as Brownrigg's animal bladder

The bladder () is a hollow organ in humans and other vertebrates that stores urine from the kidneys. In placental mammals, urine enters the bladder via the ureters and exits via the urethra during urination. In humans, the bladder is a distens ...

.

A practical application of a pneumatic trough was the eudiometer, which was used by Jan Ingenhousz to show that plants produced dephlogisticated air when exposed to sunlight

Sunlight is the portion of the electromagnetic radiation which is emitted by the Sun (i.e. solar radiation) and received by the Earth, in particular the visible spectrum, visible light perceptible to the human eye as well as invisible infrare ...

, a process now called photosynthesis

Photosynthesis ( ) is a system of biological processes by which photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical energy necessary to fuel their metabo ...

.Geerdt Magiels (2009) ''From Sunlight to Insight. Jan IngenHousz, the discovery of photosynthesis & science in the light of ecology'', Chapter 5: A crucial instrument: the rise and fall of the eudiometer, pages=199-231, VUB Press

Gasometer

During his chemical revolution, Lavoisier created a new instrument for precisely measuring out gases. He called this instrument the '' gazomètre''. He had two different versions; the one he used in demonstrations to the Académie and to the public, which was a large expensive version meant to make people believe that it had a large precision, and the smaller, more lab practical, version with a similar precision. This more practical version was cheaper to construct, allowing more chemists to use Lavoisier's instrument.See also

* Beehive shelf * Pneumatic InstitutionNotes and references

{{reflist History of chemistry Gases Chemistry experiments