In

biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary ...

, abiogenesis (from a- 'not' + Greek bios 'life' + genesis 'origin') or the origin of life is the

natural process by which

life has arisen from non-living matter, such as simple

organic compounds. The prevailing scientific hypothesis is that the transition from non-living to living entities on Earth was not a single event, but an evolutionary process of increasing complexity that involved the formation of a

habitable planet

Planetary habitability is the measure of a planet's or a natural satellite's potential to develop and maintain environments hospitable to life. Life may be generated directly on a planet or satellite endogenously or be transferred to it from a ...

, the prebiotic synthesis of

organic molecules

In chemistry, organic compounds are generally any chemical compounds that contain carbon-hydrogen or carbon-carbon bonds. Due to carbon's ability to catenate (form chains with other carbon atoms), millions of organic compounds are known. The s ...

, molecular

self-replication,

self-assembly,

autocatalysis

A single chemical reaction is said to be autocatalytic if one of the reaction products is also a catalyst for the same or a coupled reaction.Steinfeld J.I., Francisco J.S. and Hase W.L. ''Chemical Kinetics and Dynamics'' (2nd ed., Prentice-Hall 199 ...

, and the emergence of

cell membranes. Many proposals have been made for different stages of the process.

The study of abiogenesis aims to determine how pre-life

chemical reaction

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the chemical transformation of one set of chemical substances to another. Classically, chemical reactions encompass changes that only involve the positions of electrons in the forming and breakin ...

s gave rise to life under conditions strikingly different from those on Earth today. It primarily uses tools from biology and

chemistry, with more recent approaches attempting a synthesis of many sciences. Life functions through the specialized chemistry of

carbon and water, and builds largely upon four key families of chemicals:

lipids for cell membranes,

carbohydrates such as sugars,

amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

s for protein metabolism, and

nucleic acids DNA and RNA for the mechanisms of heredity. Any successful theory of abiogenesis must explain the origins and interactions of these classes of molecules. Many approaches to abiogenesis investigate how

self-replicating

Self-replication is any behavior of a dynamical system that yields construction of an identical or similar copy of itself. Biological cells, given suitable environments, reproduce by cell division. During cell division, DNA is replicated and ca ...

molecules, or their components, came into existence. Researchers generally think that current life descends from an

RNA world

The RNA world is a hypothetical stage in the evolutionary history of life on Earth, in which self-replicating RNA molecules proliferated before the evolution of DNA and proteins. The term also refers to the hypothesis that posits the existence ...

, although other self-replicating molecules may have preceded RNA.

The classic 1952

Miller–Urey experiment

The Miller–Urey experiment (or Miller experiment) is a famous chemistry experiment that simulated the conditions thought at the time (1952) to be present in the atmosphere of the early, prebiotic Earth, in order to test the hypothesis of the ...

demonstrated that most

amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

s, the chemical constituents of

proteins, can be synthesized from

inorganic compound

In chemistry, an inorganic compound is typically a chemical compound that lacks carbon–hydrogen bonds, that is, a compound that is not an organic compound. The study of inorganic compounds is a subfield of chemistry known as ''inorganic chemistr ...

s under conditions intended to replicate those of the

early Earth. External sources of energy may have triggered these reactions, including

lightning,

radiation, atmospheric entries of micro-meteorites and implosion of bubbles in sea and ocean waves. Other approaches ("metabolism-first" hypotheses) focus on understanding how

catalysis

Catalysis () is the process of increasing the rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed in the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recyc ...

in chemical systems on the early Earth might have provided the

precursor molecules necessary for self-replication.

A

genomics

Genomics is an interdisciplinary field of biology focusing on the structure, function, evolution, mapping, and editing of genomes. A genome is an organism's complete set of DNA, including all of its genes as well as its hierarchical, three-dim ...

approach has sought to characterise the

last universal common ancestor (LUCA) of modern organisms by identifying the genes shared by

Archaea and

Bacteria, members of the two major branches of life (where the

Eukaryotes belong to the archaean branch in the

two-domain system

The two-domain system is a biological classification by which all organisms in the tree of life are classified into two big domains, Bacteria and Archaea. It emerged from development in the knowledge of archaea diversity and challenge over the wi ...

). 355 genes appear to be common to all life; their nature implies that the LUCA was

anaerobic

Anaerobic means "living, active, occurring, or existing in the absence of free oxygen", as opposed to aerobic which means "living, active, or occurring only in the presence of oxygen." Anaerobic may also refer to:

* Anaerobic adhesive, a bonding a ...

with the

Wood–Ljungdahl pathway

The Wood–Ljungdahl pathway is a set of biochemical reactions used by some bacteria. It is also known as the reductive acetyl-coenzyme A (Acetyl-CoA) pathway. This pathway enables these organisms to use hydrogen as an electron donor, and ca ...

, deriving energy by

chemiosmosis

Chemiosmosis is the movement of ions across a semipermeable membrane bound structure, down their electrochemical gradient. An important example is the formation of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) by the movement of hydrogen ions (H+) across a membra ...

, and maintaining its hereditary material with

DNA, the

genetic code

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

, and

ribosomes. Although the LUCA lived over 4 billion years ago (4

Gya

A billion years or giga-annum (109 years) is a unit of time on the petasecond scale, more precisely equal to seconds (or simply 1,000,000,000 years).

It is sometimes abbreviated Gy, Ga ("giga-annum"), Byr and variants. The abbreviations Gya or ...

), researchers do not believe it was the first form of life. Earlier cells might have had a leaky membrane and been powered by a naturally-occurring

proton gradient

An electrochemical gradient is a gradient of electrochemical potential, usually for an ion that can move across a membrane. The gradient consists of two parts, the chemical gradient, or difference in solute concentration across a membrane, and th ...

near a deep-sea white smoker

hydrothermal vent

A hydrothermal vent is a fissure on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hotspot ...

.

Earth remains the only place in the

universe known to harbor life, and

fossil evidence from the Earth informs most studies of abiogenesis. The

Earth was formed 4.54 Gya; the earliest undisputed evidence of life on Earth dates from at least 3.5 Gya.

Fossil micro-organisms appear to have lived within hydrothermal vent precipitates dated 3.77 to 4.28 Gya

from Quebec, soon after

ocean formation 4.4 Gya during the

Hadean.

Overview

Life

Life consists of reproduction with (heritable) variations.

defines life as "a self-sustaining chemical system capable of Darwinian evolution."

Such a system is complex; the

last universal common ancestor (LUCA), presumably a single-celled organism which lived some 4 billion years ago, already had hundreds of

genes encoded in the

DNA genetic code

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

that is universal today. That in turn implies a suite of cellular machinery including

messenger RNA,

transfer RNAs, and

ribosomes to translate the code into

proteins. Those proteins included

enzymes to operate its

anaerobic respiration

Anaerobic respiration is respiration using electron acceptors other than molecular oxygen (O2). Although oxygen is not the final electron acceptor, the process still uses a respiratory electron transport chain.

In aerobic organisms undergoing r ...

via the

Wood–Ljungdahl metabolic pathway, and a

DNA polymerase

A DNA polymerase is a member of a family of enzymes that catalyze the synthesis of DNA molecules from nucleoside triphosphates, the molecular precursors of DNA. These enzymes are essential for DNA replication and usually work in groups to create ...

to replicate its genetic material.

The challenge for abiogenesis (origin of life)

[Compare: ] researchers is to explain how such a complex and tightly-interlinked system could develop by evolutionary steps, as at first sight

all its parts are necessary to enable it to function. For example, a cell, whether the LUCA or in a modern organism, copies its DNA with the DNA polymerase enzyme, which is in turn produced by translating the DNA polymerase gene in the DNA. Neither the enzyme nor the DNA can be produced without the other.

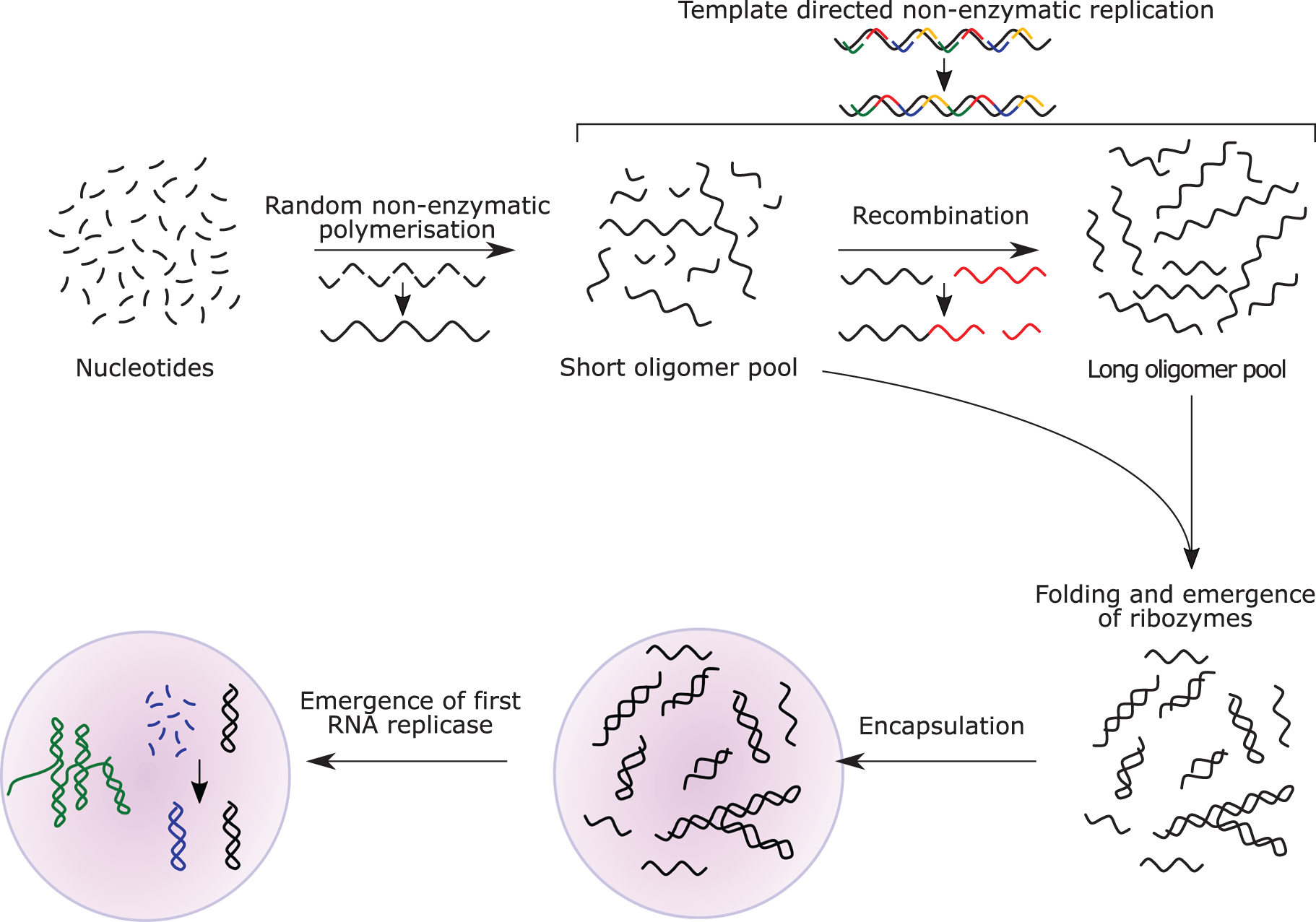

The evolutionary process could have involved molecular

self-replication,

self-assembly such as of

cell membranes, and

autocatalysis

A single chemical reaction is said to be autocatalytic if one of the reaction products is also a catalyst for the same or a coupled reaction.Steinfeld J.I., Francisco J.S. and Hase W.L. ''Chemical Kinetics and Dynamics'' (2nd ed., Prentice-Hall 199 ...

.

The precursors to the development of a living cell like the LUCA are clear enough, if disputed in their details: a habitable world is formed with a supply of minerals and liquid water. Prebiotic synthesis creates a range of simple organic compounds, which are assembled into polymers such as proteins and RNA. The process after the LUCA, too, is readily understood: Darwinian evolution caused the development of a wide range of species with varied forms and biochemical capabilities. The derivation of living things such as the LUCA from simple components, however, is far from understood.

Although Earth remains the only place where life is known,

the science of

astrobiology

Astrobiology, and the related field of exobiology, is an interdisciplinary scientific field that studies the origins, early evolution, distribution, and future of life in the universe. Astrobiology is the multidisciplinary field that investig ...

seeks evidence of life on other planets. The 2015 NASA strategy on the origin of life aimed to solve the puzzle by identifying interactions, intermediary structures and functions, energy sources, and environmental factors that contributed to the diversity, selection, and replication of evolvable macromolecular systems,

and mapping the chemical landscape of potential primordial informational

polymers. The advent of polymers that could replicate, store genetic information, and exhibit properties subject to selection was, it suggested, most likely a critical step in the

emergence of prebiotic chemical evolution.

Those polymers derived, in turn, from simple

organic compounds such as

nucleobases,

amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

s and

sugars that could have been formed by reactions in the environment.

A successful theory of the origin of life must explain how all these chemicals came into being.

Conceptual history until the 1960s

Spontaneous generation

One ancient view of the origin of life, from

Aristotle until the 19th century, is of

spontaneous generation

Spontaneous generation is a superseded scientific theory that held that living creatures could arise from nonliving matter and that such processes were commonplace and regular. It was hypothesized that certain forms, such as fleas, could arise f ...

. This theory held that "lower" animals were generated by decaying organic substances, and that life arose by chance.

This was questioned from the 17th century, in works like

Thomas Browne's ''

Pseudodoxia Epidemica''. In 1665,

Robert Hooke published the first drawings of a

microorganism. In 1676,

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek

Antonie Philips van Leeuwenhoek ( ; ; 24 October 1632 – 26 August 1723) was a Dutch microbiologist and microscopist in the Golden Age of Dutch science and technology. A largely self-taught man in science, he is commonly known as " the ...

drew and described microorganisms, probably

protozoa

Protozoa (singular: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a group of single-celled eukaryotes, either free-living or parasitic, that feed on organic matter such as other microorganisms or organic tissues and debris. Histo ...

and

bacteria. Van Leeuwenhoek disagreed with spontaneous generation, and by the 1680s convinced himself, using experiments ranging from sealed and open meat incubation and the close study of insect reproduction, that the theory was incorrect. In 1668

Francesco Redi

Francesco Redi (18 February 1626 – 1 March 1697) was an Italian physician, naturalist, biologist, and poet. He is referred to as the "founder of experimental biology", and as the "father of modern parasitology". He was the first person to ch ...

showed that no

maggots appeared in meat when flies were prevented from laying eggs.

By the middle of the 19th century, spontaneous generation was considered disproven.

Panspermia

Another ancient idea dating back to

Anaxagoras

Anaxagoras (; grc-gre, Ἀναξαγόρας, ''Anaxagóras'', "lord of the assembly"; 500 – 428 BC) was a Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. Born in Clazomenae at a time when Asia Minor was under the control of the Persian Empire, ...

in the 5th century BC is

panspermia

Panspermia () is the hypothesis, first proposed in the 5th century BCE by the Greek philosopher Anaxagoras, that life exists throughout the Universe, distributed by space dust, meteoroids, asteroids, comets, and planetoids, as well as by spacecr ...

,

the idea that

life exists throughout the

universe, distributed by

meteoroids

A meteoroid () is a small rocky or metallic body in outer space.

Meteoroids are defined as objects significantly smaller than asteroids, ranging in size from grains to objects up to a meter wide. Objects smaller than this are classified as micr ...

,

asteroids

An asteroid is a minor planet of the inner Solar System. Sizes and shapes of asteroids vary significantly, ranging from 1-meter rocks to a dwarf planet almost 1000 km in diameter; they are rocky, metallic or icy bodies with no atmosphere.

...

,

comets

A comet is an icy, small Solar System body that, when passing close to the Sun, warms and begins to release gases, a process that is called outgassing. This produces a visible atmosphere or coma, and sometimes also a tail. These phenomena are ...

and

planetoids

According to the International Astronomical Union (IAU), a minor planet is an astronomical object in direct orbit around the Sun that is exclusively classified as neither a planet nor a comet. Before 2006, the IAU officially used the term ''minor ...

. It does not attempt to explain how life originated in itself, but shifts the origin of life on Earth to another heavenly body. The advantage is that life is not required to have formed on each planet it occurs on, but rather in a more limited set of locations (potentially even a single location), and then spread about the

galaxy

A galaxy is a system of stars, stellar remnants, interstellar gas, dust, dark matter, bound together by gravity. The word is derived from the Greek ' (), literally 'milky', a reference to the Milky Way galaxy that contains the Solar System. ...

to other star systems via cometary or meteorite impact.

"A warm little pond": primordial soup

The idea that life originated from non-living matter in slow stages appeared in

Herbert Spencer's 1864–1867 book ''Principles of Biology'', and in

William Turner Thiselton-Dyer

Sir William Turner Thiselton-Dyer (28 July 1843 – 23 December 1928) was a leading British botanist, and the third director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

Life and career

Thiselton-Dyer was born in Westminster, London. He was a son of ...

's 1879 paper "On spontaneous generation and evolution". On 1 February 1871

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

wrote about these publications to

Joseph Hooker, and set out his own speculation, suggesting that the original spark of life may have begun in a "warm little pond, with all sorts of ammonia and phosphoric salts, light, heat, electricity, , present, that a compound was chemically formed ready to undergo still more complex changes." Darwin went on to explain that "at the present day such matter would be instantly devoured or absorbed, which would not have been the case before living creatures were formed."

Alexander Oparin

Alexander Ivanovich Oparin (russian: Александр Иванович Опарин; – April 21, 1980) was a Soviet biochemist notable for his theories about the origin of life, and for his book ''The Origin of Life''. He also studied the bi ...

in 1924 and

J. B. S. Haldane in 1929 proposed that the first molecules constituting the earliest cells slowly self-organized from a

primordial soup.

[

* ] Haldane suggested that the Earth's prebiotic oceans consisted of a "hot dilute soup" in which organic compounds could have formed.

J. D. Bernal

John Desmond Bernal (; 10 May 1901 – 15 September 1971) was an Irish scientist who pioneered the use of X-ray crystallography in molecular biology. He published extensively on the history of science. In addition, Bernal wrote popular book ...

showed that such mechanisms could form most of the necessary molecules for life from inorganic precursors. In 1967, he suggested three "stages": the origin of biological

monomers; the origin of biological polymers; and the evolution from molecules to cells.

Miller–Urey experiment

In 1952,

Stanley Miller

Stanley Lloyd Miller (March 7, 1930 – May 20, 2007) was an American chemist who made landmark experiments in the origin of life by demonstrating that a wide range of vital organic compounds can be synthesized by fairly simple chemical process ...

and

Harold Urey carried out a chemical experiment to demonstrate how organic molecules could have formed spontaneously from inorganic precursors under

prebiotic conditions like those posited by the Oparin-Haldane hypothesis. It used a highly

reducing (lacking oxygen) mixture of gases—

methane,

ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous wa ...

, and

hydrogen, as well as

water vapor—to form simple organic monomers such as amino acids.

Bernal said of the Miller–Urey experiment that "it is not enough to explain the formation of such molecules, what is necessary, is a physical-chemical explanation of the origins of these molecules that suggests the presence of suitable sources and sinks for free energy." However, current scientific consensus describes the primitive atmosphere as weakly reducing or neutral,

diminishing the amount and variety of amino acids that could be produced. The addition of

iron and

carbonate

A carbonate is a salt of carbonic acid (H2CO3), characterized by the presence of the carbonate ion, a polyatomic ion with the formula . The word ''carbonate'' may also refer to a carbonate ester, an organic compound containing the carbonate g ...

minerals, present in early oceans, however produces a diverse array of amino acids.

Later work has focused on two other potential reducing environments:

outer space and deep-sea hydrothermal vents.

Producing a habitable Earth

Early universe with first stars

Soon after the

Big Bang

The Big Bang event is a physical theory that describes how the universe expanded from an initial state of high density and temperature. Various cosmological models of the Big Bang explain the evolution of the observable universe from the ...

, which occurred roughly 14 Gya, the only chemical elements present in the universe were hydrogen, helium, and lithium, the three lightest atoms in the periodic table. These elements gradually came together to form stars. These early stars were massive and short-lived, producing all the heavier elements through

stellar nucleosynthesis

Stellar nucleosynthesis is the creation (nucleosynthesis) of chemical elements by nuclear fusion reactions within stars. Stellar nucleosynthesis has occurred since the original creation of hydrogen, helium and lithium during the Big Bang. A ...

.

Carbon, currently the

fourth most abundant chemical element in the universe (after

hydrogen,

helium and

oxygen), was formed mainly in

white dwarf stars

A white dwarf is a stellar core remnant composed mostly of electron-degenerate matter. A white dwarf is very dense: its mass is comparable to the Sun's, while its volume is comparable to the Earth's. A white dwarf's faint luminosity comes fr ...

, particularly those bigger than twice the mass of the sun.

As these stars reached the end of their

lifecycles, they ejected these heavier elements, among them carbon and oxygen, throughout the universe. These heavier elements allowed for the formation of new objects, including rocky planets and other bodies. According to the

nebular hypothesis, the formation and evolution of the

Solar System began 4.6 Gya with the

gravitational collapse of a small part of a giant

molecular cloud. Most of the collapsing mass collected in the center, forming the

Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

, while the rest flattened into a

protoplanetary disk out of which the

planets,

moons

A natural satellite is, in the most common usage, an astronomical body that orbits a planet, dwarf planet, or small Solar System body (or sometimes another natural satellite). Natural satellites are often colloquially referred to as ''moons'' ...

,

asteroid

An asteroid is a minor planet of the inner Solar System. Sizes and shapes of asteroids vary significantly, ranging from 1-meter rocks to a dwarf planet almost 1000 km in diameter; they are rocky, metallic or icy bodies with no atmosphere.

...

s, and other

small Solar System bodies

A small Solar System body (SSSB) is an object in the Solar System that is neither a planet, a dwarf planet, nor a natural satellite. The term was first defined in 2006 by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) as follows: "All other objects, ...

formed.

Emergence of Earth

The

Earth was formed 4.54 Gya.

The

Hadean Earth (from its formation until 4 Gya) was at first inhospitable to any living organisms. During its formation, the Earth lost a significant part of its initial mass, and consequentially lacked the

gravity to hold molecular hydrogen and the bulk of the original inert gases. The atmosphere consisted largely of water vapor,

nitrogen, and

carbon dioxide, with smaller amounts of

carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (chemical formula CO) is a colorless, poisonous, odorless, tasteless, flammable gas that is slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the simpl ...

,

hydrogen, and

sulfur compounds. The solution of carbon dioxide in water is thought to have made the seas slightly

acid

In computer science, ACID ( atomicity, consistency, isolation, durability) is a set of properties of database transactions intended to guarantee data validity despite errors, power failures, and other mishaps. In the context of databases, a sequ ...

ic, with a

pH of about 5.5. The Hadean atmosphere has been characterized as a "gigantic, productive outdoor chemical laboratory,"

similar to volcanic gases today which still support some abiotic chemistry.

may have

appeared as soon as 200 million years after the Earth formed, in a near-boiling (100 C) reducing environment, as the pH of 5.8 rose rapidly towards neutral. This scenario has found support from the dating of 4.404 Gya

zircon

Zircon () is a mineral belonging to the group of nesosilicates and is a source of the metal zirconium. Its chemical name is zirconium(IV) silicate, and its corresponding chemical formula is Zr SiO4. An empirical formula showing some of the ...

crystals from metamorphosed

quartzite of

Mount Narryer in Western Australia.

Despite the likely increased volcanism, the Earth may have been a water world between 4.4 and 4.3 Gya, with little if any continental crust, a turbulent atmosphere, and a

hydrosphere

The hydrosphere () is the combined mass of water found on, under, and above the surface of a planet, minor planet, or natural satellite. Although Earth's hydrosphere has been around for about 4 billion years, it continues to change in shape. This ...

subject to intense

ultraviolet light from a

T Tauri stage Sun, from

cosmic radiation

Cosmic rays are high-energy particles or clusters of particles (primarily represented by protons or atomic nuclei) that move through space at nearly the speed of light. They originate from the Sun, from outside of the Solar System in our own ...

, and from continued

asteroid

An asteroid is a minor planet of the inner Solar System. Sizes and shapes of asteroids vary significantly, ranging from 1-meter rocks to a dwarf planet almost 1000 km in diameter; they are rocky, metallic or icy bodies with no atmosphere.

...

and

comet

A comet is an icy, small Solar System body that, when passing close to the Sun, warms and begins to release gases, a process that is called outgassing. This produces a visible atmosphere or coma, and sometimes also a tail. These phenomena are ...

impacts.

The

Late Heavy Bombardment

The Late Heavy Bombardment (LHB), or lunar cataclysm, is a hypothesized event thought to have occurred approximately 4.1 to 3.8 billion years (Ga) ago, at a time corresponding to the Neohadean and Eoarchean eras on Earth. According to the hypot ...

hypothesis posits that the Hadean environment between 4.28

and 3.8 Gya was highly hazardous to life. Following the

Nice model, changes in the orbits of the

giant planets may have bombarded the Earth with asteroids and comets that pockmarked the

Moon and

inner planets

The Solar SystemCapitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar S ...

. Frequent collisions would have made

photosynthesis unviable.

The periods between such devastating events give time windows for the possible origin of life in early environments. If the deep marine hydrothermal setting was the site for the origin of life, then abiogenesis could have happened as early as 4.0-4.2 Gya. If the site was at the surface of the Earth, abiogenesis could have occurred only between 3.7 and 4.0 Gya. However, new lunar surveys and samples have led scientists, including an architect of the Nice model, to deemphasize the significance of the Late Heavy Bombardment.

If life evolved in the ocean at depths of more than ten meters, it would have been shielded both from late impacts and the then high levels of ultraviolet radiation from the sun. Geothermically heated oceanic crust could have yielded far more organic compounds through deep

hydrothermal vent

A hydrothermal vent is a fissure on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hotspot ...

s than the

Miller–Urey experiment

The Miller–Urey experiment (or Miller experiment) is a famous chemistry experiment that simulated the conditions thought at the time (1952) to be present in the atmosphere of the early, prebiotic Earth, in order to test the hypothesis of the ...

s indicated. The available energy is maximized at 100–150 °C, the temperatures at which

hyperthermophilic

A hyperthermophile is an organism that thrives in extremely hot environments—from 60 °C (140 °F) upwards. An optimal temperature for the existence of hyperthermophiles is often above 80 °C (176 °F). Hyperthermophiles are often within the doma ...

bacteria and

thermoacidophilic archaea live. These modern organisms may be among the closest surviving relatives of the LUCA.

Earliest evidence of life

Life existed on Earth more than 3.5 Gya,

during the

Eoarchean

The Eoarchean (; also spelled Eoarchaean) is the first era of the Archean Eon of the geologic record. It spans 400 million years, from the end of the Hadean Eon 4 billion years ago (4000 Mya) to the start of the Paleoarchean Era 3600 Mya. The ...

when sufficient crust had solidified following the molten Hadean.

The earliest physical evidence of life so far found consists of

microfossils

A microfossil is a fossil that is generally between 0.001 mm and 1 mm in size, the visual study of which requires the use of light or electron microscopy. A fossil which can be studied with the naked eye or low-powered magnification, ...

in the

Nuvvuagittuq Greenstone Belt

The Nuvvuagittuq Greenstone Belt (NGB; Inuktitut: ) is a sequence of metamorphosed mafic to ultramafic volcanic and associated sedimentary rocks (a greenstone belt) located on the eastern shore of Hudson Bay, 40 km southeast of Inukjuak, Que ...

of Northern Quebec, in

banded iron formation

Banded iron formations (also known as banded ironstone formations or BIFs) are distinctive units of sedimentary rock consisting of alternating layers of iron oxides and iron-poor chert. They can be up to several hundred meters in thickness a ...

rocks at least 3.77 and possibly 4.28 Gya. The micro-organisms lived within hydrothermal vent precipitates, soon after the 4.4 Gya

formation of oceans during the Hadean. The microbes resembled modern hydrothermal vent bacteria, supporting the view that abiogenesis began in such an environment.

Biogenic

graphite has been found in 3.7 Gya metasedimentary rocks from southwestern

Greenland and in

microbial mat

A microbial mat is a multi-layered sheet of microorganisms, mainly bacteria and archaea, or bacteria alone. Microbial mats grow at interfaces between different types of material, mostly on submerged or moist surfaces, but a few survive in desert ...

fossils from 3.49 Gya

Western Australian sandstone.

Evidence of early life in rocks from

Akilia Island, near the

Isua supracrustal belt in southwestern Greenland, dating to 3.7 Gya, have shown biogenic

carbon isotope

Carbon (6C) has 15 known isotopes, from to , of which and are stable. The longest-lived radioisotope is , with a half-life of years. This is also the only carbon radioisotope found in nature—trace quantities are formed cosmogenically by ...

s. In other parts of the Isua supracrustal belt, graphite inclusions trapped within

garnet crystals are connected to the other elements of life: oxygen, nitrogen, and possibly phosphorus in the form of

phosphate, providing further evidence for life 3.7 Gya. In the

Pilbara region of Western Australia, compelling evidence of early life was found in

pyrite

The mineral pyrite (), or iron pyrite, also known as fool's gold, is an iron sulfide with the chemical formula Fe S2 (iron (II) disulfide). Pyrite is the most abundant sulfide mineral.

Pyrite's metallic luster and pale brass-yellow hue giv ...

-bearing sandstone in a fossilized beach, with rounded tubular cells that

oxidized

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a ...

sulfur by photosynthesis in the absence of oxygen.

Zircon

Zircon () is a mineral belonging to the group of nesosilicates and is a source of the metal zirconium. Its chemical name is zirconium(IV) silicate, and its corresponding chemical formula is Zr SiO4. An empirical formula showing some of the ...

s from Western Australia imply that life existed on Earth at least 4.1 Gya.

[ Early edition, published online before print.]

The Pilbara region of Western Australia contains the Dresser Formation with rocks 3.48 Gya, including layered structures called

stromatolite

Stromatolites () or stromatoliths () are layered sedimentary formations (microbialite) that are created mainly by photosynthetic microorganisms such as cyanobacteria, sulfate-reducing bacteria, and Pseudomonadota (formerly proteobacteria). The ...

s. Their modern counterparts are created by photosynthetic micro-organisms including

cyanobacteria. These lie within undeformed hydrothermal-sedimentary strata; their texture indicates a biogenic origin. Parts of the Dresser formation preserve

hot springs on land, but other regions seem to have been shallow seas.

File:Stromatolites.jpg, Stromatolite

Stromatolites () or stromatoliths () are layered sedimentary formations (microbialite) that are created mainly by photosynthetic microorganisms such as cyanobacteria, sulfate-reducing bacteria, and Pseudomonadota (formerly proteobacteria). The ...

s in the Siyeh Formation, Glacier National Park, dated 3.5 Gya, placing them among the earliest life-forms.

File:Stromatolites in Sharkbay.jpg, Modern stromatolites in Shark Bay, created by photosynthetic cyanobacteria.

Producing molecules: prebiotic synthesis

All

chemical element

A chemical element is a species of atoms that have a given number of protons in their nuclei, including the pure substance consisting only of that species. Unlike chemical compounds, chemical elements cannot be broken down into simpler sub ...

s except for hydrogen and helium derive from

stellar nucleosynthesis

Stellar nucleosynthesis is the creation (nucleosynthesis) of chemical elements by nuclear fusion reactions within stars. Stellar nucleosynthesis has occurred since the original creation of hydrogen, helium and lithium during the Big Bang. A ...

. The basic chemical ingredients of

life – the

carbon-hydrogen molecule (CH), the carbon-hydrogen positive ion (CH+) and the carbon ion (C+) – were produced by

ultraviolet light from stars.

Complex molecules, including organic molecules, form naturally both in space and on planets.

Organic molecules on the early Earth could have had either terrestrial origins, with organic molecule synthesis driven by impact shocks or by other energy sources, such as ultraviolet light,

redox coupling, or electrical discharges; or extraterrestrial origins (

pseudo-panspermia

Pseudo-panspermia (sometimes called soft panspermia, molecular panspermia or quasi-panspermia) is a well-supported hypothesis for a stage in the origin of life. The theory first asserts that many of the small organic molecules used for life origin ...

), with organic molecules formed in

interstellar dust clouds raining down on to the planet.

Observed extraterrestrial organic molecules

An organic compound is a chemical whose molecules contain carbon. Carbon is abundant in the Sun, stars, comets, and in the

atmospheres

The standard atmosphere (symbol: atm) is a unit of pressure defined as Pa. It is sometimes used as a ''reference pressure'' or ''standard pressure''. It is approximately equal to Earth's average atmospheric pressure at sea level.

History

The s ...

of most planets.

Organic compounds are relatively common in space, formed by "factories of complex molecular synthesis" which occur in

molecular clouds and

circumstellar envelopes, and chemically evolve after reactions are initiated mostly by

ionizing radiation.

and

pyrimidine

Pyrimidine (; ) is an aromatic, heterocyclic, organic compound similar to pyridine (). One of the three diazines (six-membered heterocyclics with two nitrogen atoms in the ring), it has nitrogen atoms at positions 1 and 3 in the ring. The othe ...

nucleobases including

guanine

Guanine () (symbol G or Gua) is one of the four main nucleobases found in the nucleic acids DNA and RNA, the others being adenine, cytosine, and thymine (uracil in RNA). In DNA, guanine is paired with cytosine. The guanine nucleoside is called ...

,

adenine

Adenine () (symbol A or Ade) is a nucleobase (a purine derivative). It is one of the four nucleobases in the nucleic acid of DNA that are represented by the letters G–C–A–T. The three others are guanine, cytosine and thymine. Its derivativ ...

,

cytosine

Cytosine () (symbol C or Cyt) is one of the four nucleobases found in DNA and RNA, along with adenine, guanine, and thymine (uracil in RNA). It is a pyrimidine derivative, with a heterocyclic aromatic ring and two substituents attached (an amin ...

,

uracil and

thymine

Thymine () (symbol T or Thy) is one of the four nucleobases in the nucleic acid of DNA that are represented by the letters G–C–A–T. The others are adenine, guanine, and cytosine. Thymine is also known as 5-methyluracil, a pyrimidine nuc ...

have been found in

meteorites. These could have provided the materials for

DNA and

RNA to form on the

early Earth.

The amino acid

glycine

Glycine (symbol Gly or G; ) is an amino acid that has a single hydrogen atom as its side chain. It is the simplest stable amino acid ( carbamic acid is unstable), with the chemical formula NH2‐ CH2‐ COOH. Glycine is one of the proteinogen ...

was found in material ejected from comet

Wild 2; it had earlier been detected in meteorites. Comets are encrusted with dark material, thought to be a

tar

Tar is a dark brown or black viscous liquid of hydrocarbons and free carbon, obtained from a wide variety of organic materials through destructive distillation. Tar can be produced from coal, wood, petroleum, or peat. "a dark brown or black b ...

-like organic substance formed from simple carbon compounds under ionizing radiation. A rain of material from comets could have brought such complex organic molecules to Earth.

It is estimated that during the Late Heavy Bombardment, meteorites may have delivered up to five million

ton

Ton is the name of any one of several units of measure. It has a long history and has acquired several meanings and uses.

Mainly it describes units of weight. Confusion can arise because ''ton'' can mean

* the long ton, which is 2,240 pounds

...

s of organic prebiotic elements to Earth per year.

PAH world hypothesis

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon

A polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) is a class of organic compounds that is composed of multiple aromatic rings. The simplest representative is naphthalene, having two aromatic rings and the three-ring compounds anthracene and phenanthrene. ...

s (PAH) are the most common and abundant polyatomic molecules in the

observable universe, and are a major store of carbon.

They seem to have formed shortly after the Big Bang,

and are associated with

new stars and

exoplanet

An exoplanet or extrasolar planet is a planet outside the Solar System. The first possible evidence of an exoplanet was noted in 1917 but was not recognized as such. The first confirmation of detection occurred in 1992. A different planet, init ...

s.

They are a likely constituent of Earth's primordial sea.

PAHs have been detected in

nebula

A nebula ('cloud' or 'fog' in Latin; pl. nebulae, nebulæ or nebulas) is a distinct luminescent part of interstellar medium, which can consist of ionized, neutral or molecular hydrogen and also cosmic dust. Nebulae are often star-forming region ...

e,

and in the

interstellar medium

In astronomy, the interstellar medium is the matter and radiation that exist in the space between the star systems in a galaxy. This matter includes gas in ionic, atomic, and molecular form, as well as dust and cosmic rays. It fills interstellar ...

, in comets, and in meteorites.

The PAH world hypothesis posits PAHs as precursors to the RNA world. A star, HH 46-IR, resembling the sun early in its life, is surrounded by a disk of material which contains molecules including cyanide compounds,

hydrocarbons, and carbon monoxide. PAHs in the interstellar medium can be transformed through

hydrogenation

Hydrogenation is a chemical reaction between molecular hydrogen (H2) and another compound or element, usually in the presence of a catalyst such as nickel, palladium or platinum. The process is commonly employed to reduce or saturate organic c ...

,

oxygenation, and

hydroxylation to more complex organic compounds used in living cells.

Nucleobases

The majority of organic compounds introduced on Earth by interstellar dust particles have helped to form complex molecules, thanks to their peculiar

surface-catalytic activities.

[ "Paper presented at the Symposium 'Astrochemistry: molecules in space and time' (Rome, 4–5 November 2010), sponsored by Fondazione 'Guido Donegani', Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei."] Studies of the

12C/

13C

isotopic ratios of organic compounds in the Murchison meteorite suggest that the RNA component uracil and related molecules, including

xanthine

Xanthine ( or ; archaically xanthic acid; systematic name 3,7-dihydropurine-2,6-dione) is a purine base found in most human body tissues and fluids, as well as in other organisms. Several stimulants are derived from xanthine, including caffein ...

, were formed extraterrestrially.

NASA studies of meteorites suggest that all four DNA

nucleobases (adenine, guanine and related organic molecules) have been formed in outer space.

The

cosmic dust permeating the universe contains complex organics ("amorphous organic solids with a mixed

aromatic

In chemistry, aromaticity is a chemical property of cyclic ( ring-shaped), ''typically'' planar (flat) molecular structures with pi bonds in resonance (those containing delocalized electrons) that gives increased stability compared to satu ...

–

aliphatic

In organic chemistry, hydrocarbons ( compounds composed solely of carbon and hydrogen) are divided into two classes: aromatic compounds and aliphatic compounds (; G. ''aleiphar'', fat, oil). Aliphatic compounds can be saturated, like hexane ...

structure") that could be created rapidly by stars.

Glycolaldehyde, a sugar molecule and RNA precursor, has been detected in regions of space including around

protostars and on meteorites.

Laboratory synthesis

As early as the 1860s, experiments demonstrated that biologically relevant molecules can be produced from interaction of simple carbon sources with abundant inorganic catalysts. The spontaneous formation of complex polymers from abiotically generated monomers under the conditions posited by the "soup" theory is not straightforward. Besides the necessary basic organic monomers, compounds that would have prohibited the formation of polymers were also formed in high concentration during the Miller–Urey and

Joan Oró experiments. Biology uses essentially 20 amino acids for its coded protein enzymes, representing a very small subset of the structurally possible products. Since life tends to use whatever is available, an explanation is needed for why the set used is so small.

Sugars

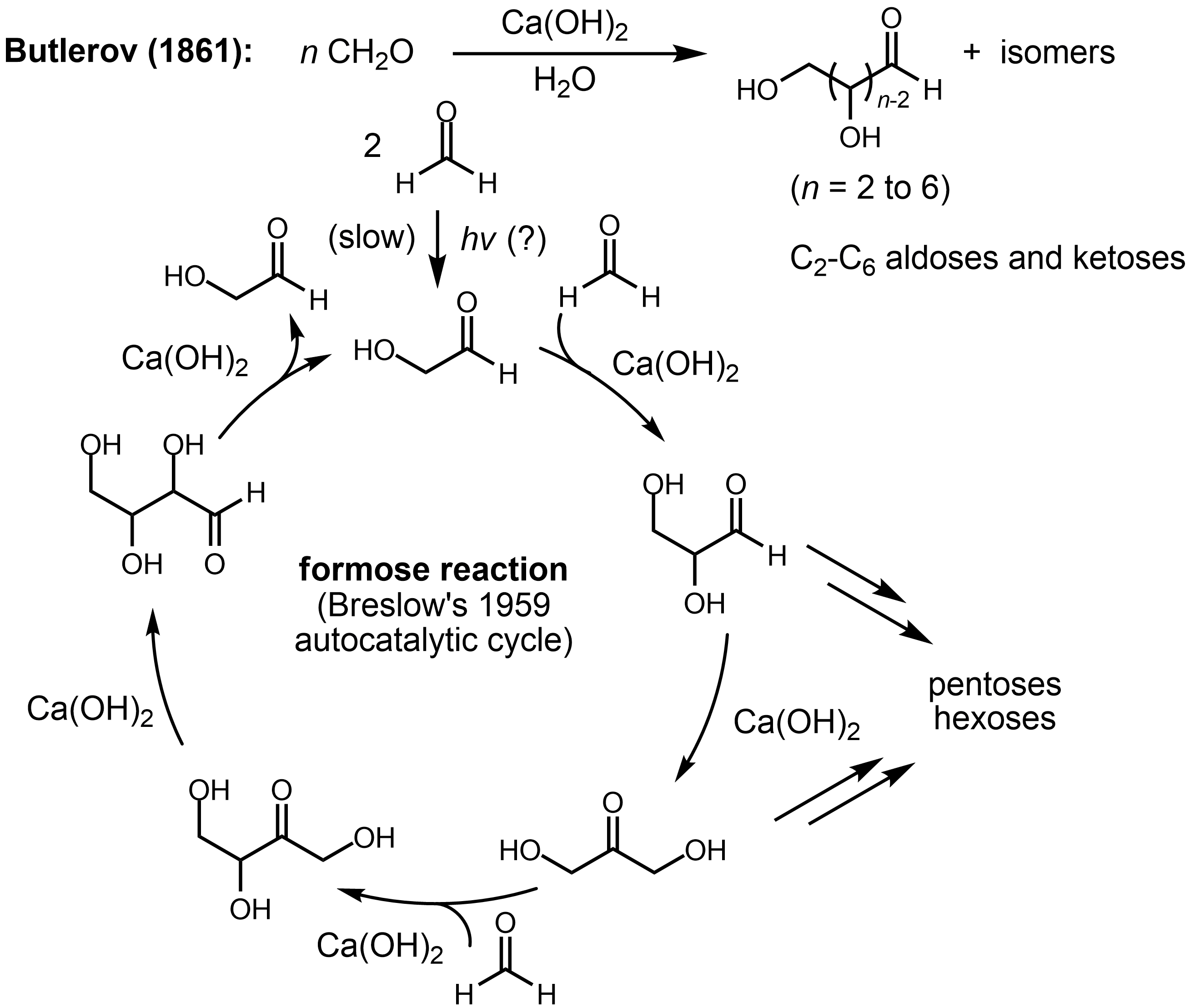

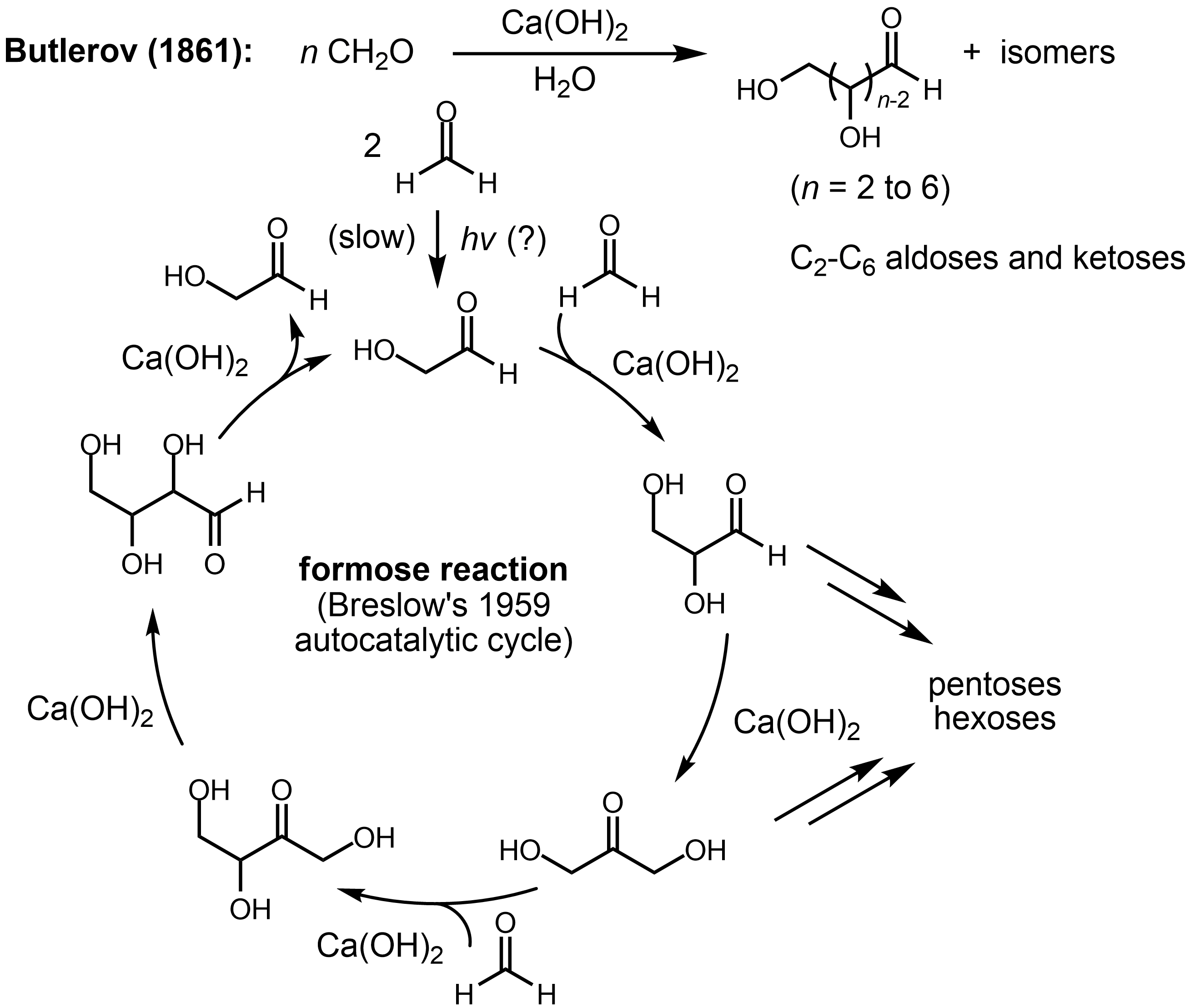

Alexander Butlerov

Alexander Butlerov showed in 1861 that the

formose reaction

The formose reaction, discovered by Aleksandr Butlerov in 1861, and hence also known as the Butlerov reaction, involves the formation of sugars from formaldehyde. The term formose is a portmanteau of formaldehyde and aldose.

Reaction and mechanism ...

created sugars including tetroses, pentoses, and hexoses when

formaldehyde is heated under basic conditions with divalent metal ions like calcium. R. Breslow proposed that the reaction was autocatalytic in 1959.

Nucleobases

Nucleobases like guanine and adenine can be synthesized from simple carbon and nitrogen sources like

hydrogen cyanide (HCN) and ammonia.

Formamide produces all four ribonucleotides when warmed with terrestrial minerals. Formamide is ubiquitous in the Universe, produced by the reaction of water and HCN. It can be concentrated by the evaporation of water.

HCN is poisonous only to

aerobic organism

Aerobic means "requiring air," in which "air" usually means oxygen.

Aerobic may also refer to

* Aerobic exercise, prolonged exercise of moderate intensity

* Aerobics, a form of aerobic exercise

* Aerobic respiration, the aerobic process of cel ...

s (

eukaryotes and aerobic bacteria), which did not yet exist. It can play roles in other chemical processes such as the synthesis of the amino acid

glycine

Glycine (symbol Gly or G; ) is an amino acid that has a single hydrogen atom as its side chain. It is the simplest stable amino acid ( carbamic acid is unstable), with the chemical formula NH2‐ CH2‐ COOH. Glycine is one of the proteinogen ...

.

DNA and RNA components including uracil, cytosine and thymine can be synthesized under outer space conditions, using starting chemicals such as

pyrimidine

Pyrimidine (; ) is an aromatic, heterocyclic, organic compound similar to pyridine (). One of the three diazines (six-membered heterocyclics with two nitrogen atoms in the ring), it has nitrogen atoms at positions 1 and 3 in the ring. The othe ...

found in meteorites. Pyrimidine may have been formed in

red giant

A red giant is a luminous giant star of low or intermediate mass (roughly 0.3–8 solar masses ()) in a late phase of stellar evolution. The outer atmosphere is inflated and tenuous, making the radius large and the surface temperature around or ...

stars or in interstellar dust and gas clouds.

All four RNA-bases may be synthesized from formamide in high-energy density events like extraterrestrial impacts.

Other pathways for synthesizing bases from inorganic materials have been reported.

Freezing temperatures are advantageous for the synthesis of purines, due to the concentrating effect for key precursors such as hydrogen cyanide. However, while adenine and

guanine

Guanine () (symbol G or Gua) is one of the four main nucleobases found in the nucleic acids DNA and RNA, the others being adenine, cytosine, and thymine (uracil in RNA). In DNA, guanine is paired with cytosine. The guanine nucleoside is called ...

require freezing conditions for synthesis,

cytosine

Cytosine () (symbol C or Cyt) is one of the four nucleobases found in DNA and RNA, along with adenine, guanine, and thymine (uracil in RNA). It is a pyrimidine derivative, with a heterocyclic aromatic ring and two substituents attached (an amin ...

and

uracil may require boiling temperatures. Seven different amino acids and eleven types of

nucleobases formed in ice when ammonia and

cyanide

Cyanide is a naturally occurring, rapidly acting, toxic chemical that can exist in many different forms.

In chemistry, a cyanide () is a chemical compound that contains a functional group. This group, known as the cyano group, consists of a ...

were left in a freezer for 25 years. S-

triazines (alternative nucleobases),

pyrimidine

Pyrimidine (; ) is an aromatic, heterocyclic, organic compound similar to pyridine (). One of the three diazines (six-membered heterocyclics with two nitrogen atoms in the ring), it has nitrogen atoms at positions 1 and 3 in the ring. The othe ...

s including cytosine and uracil, and adenine can be synthesized by subjecting a urea solution to freeze-thaw cycles under a reductive atmosphere, with spark discharges as an energy source. The explanation given for the unusual speed of these reactions at such a low temperature is

eutectic freezing, which crowds impurities in microscopic pockets of liquid within the ice, causing the molecules to collide more often.

Producing suitable vesicles

The

lipid world theory postulates that the first self-replicating object was

lipid-like. Phospholipids form

lipid bilayers in water while under agitation—the same structure as in cell membranes. These molecules were not present on early Earth, but other

amphiphilic

An amphiphile (from the Greek αμφις amphis, both, and φιλíα philia, love, friendship), or amphipath, is a chemical compound possessing both hydrophilic (''water-loving'', polar) and lipophilic (''fat-loving'') properties. Such a compoun ...

long-chain molecules also form membranes. These bodies may expand by insertion of additional lipids, and may spontaneously split into two

offspring of similar size and composition. The main idea is that the molecular composition of the lipid bodies is a preliminary to information storage, and that evolution led to the appearance of polymers like RNA that store information. Studies on vesicles from amphiphiles that might have existed in the prebiotic world have so far been limited to systems of one or two types of amphiphiles.

A lipid bilayer membrane could be composed of a huge number of combinations of arrangements of amphiphiles. The best of these would have favored the constitution of a hypercycle, actually a positive

feedback

Feedback occurs when outputs of a system are routed back as inputs as part of a chain of cause-and-effect that forms a circuit or loop. The system can then be said to ''feed back'' into itself. The notion of cause-and-effect has to be handled c ...

composed of two mutual catalysts represented by a membrane site and a specific compound trapped in the vesicle. Such site/compound pairs are transmissible to the daughter vesicles leading to the emergence of distinct

lineages of vesicles, which would have allowed Darwinian natural selection.

A

protocell is a

self-organized, self-ordered, spherical collection of

lipids proposed as a stepping-stone to the origin of life.

The theory of classical irreversible thermodynamics treats self-assembly under a generalized chemical potential within the framework of

dissipative systems.

A central question in evolution is how simple protocells first arose and differed in reproductive contribution to the following generation, thus driving the evolution of life. A functional protocell has (as of 2014) not yet been achieved in a laboratory setting.

Self-assembled

vesicles

Vesicle may refer to:

; In cellular biology or chemistry

* Vesicle (biology and chemistry), a supramolecular assembly of lipid molecules, like a cell membrane

* Synaptic vesicle

; In human embryology

* Vesicle (embryology), bulge-like features o ...

are essential components of primitive cells.

The

second law of thermodynamics requires that the universe move in a direction in which

entropy increases, yet life is distinguished by its great degree of organization. Therefore, a boundary is needed to separate

life processes from non-living matter.

Irene Chen and

Jack W. Szostak

Jack William Szostak (born November 9, 1952) is a Canadian American biologist of Polish British descent, Nobel Prize laureate, university professor at the University of Chicago, former Professor of Genetics at Harvard Medical School, and Alexan ...

suggest that elementary protocells can give rise to cellular behaviors including primitive forms of differential reproduction, competition, and energy storage.

Competition for membrane molecules would favor stabilized membranes, suggesting a selective advantage for the evolution of cross-linked fatty acids and even the

phospholipid

Phospholipids, are a class of lipids whose molecule has a hydrophilic "head" containing a phosphate group and two hydrophobic "tails" derived from fatty acids, joined by an alcohol residue (usually a glycerol molecule). Marine phospholipids typ ...

s of today.

Such

micro-encapsulation would allow for metabolism within the membrane and the exchange of small molecules, while retaining large biomolecules inside. Such a membrane is needed for a cell to create its own

electrochemical gradient

An electrochemical gradient is a gradient of electrochemical potential, usually for an ion that can move across a membrane. The gradient consists of two parts, the chemical gradient, or difference in solute concentration across a membrane, and ...

to store energy by pumping ions across the membrane.

Producing biology

Energy and entropy

Life requires a loss of

entropy, or disorder, when molecules organize themselves into living matter. The emergence of life and increased complexity does not contradict the

second law of thermodynamics, which states that overall entropy never decreases, since a living organism creates order in some places (e.g. its living body) at the expense of an increase of entropy elsewhere (e.g. heat and waste production).

Multiple sources of energy were available for chemical reactions on the early Earth. Heat from

geothermal processes is a standard energy source for chemistry. Other examples include sunlight, lightning,

atmospheric entries of micro-meteorites,

and implosion of bubbles in sea and ocean waves.

This has been confirmed by experiments

and simulations.

Unfavorable reactions can be driven by highly favorable ones, as in the case of iron-sulfur chemistry. For example, this was probably important for

carbon fixation

Biological carbon fixation or сarbon assimilation is the process by which inorganic carbon (particularly in the form of carbon dioxide) is converted to organic compounds by living organisms. The compounds are then used to store energy and a ...

. Carbon fixation by reaction of CO

2 with H

2S via iron-sulfur chemistry is favorable, and occurs at neutral pH and 100 °C. Iron-sulfur surfaces, which are abundant near hydrothermal vents, can drive the production of small amounts of amino acids and other biomolecules.

Chemiosmosis

In 1961,

Peter Mitchell Peter or Pete Mitchell may refer to:

Media

*Pete Mitchell (broadcaster) (1958–2020), British broadcaster

* Peter Mitchell (newsreader) (born 1960), Australian journalist

* Peter Mitchell (photographer) (born 1943), British documentary photographe ...

proposed

chemiosmosis

Chemiosmosis is the movement of ions across a semipermeable membrane bound structure, down their electrochemical gradient. An important example is the formation of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) by the movement of hydrogen ions (H+) across a membra ...

as a cell's primary system of energy conversion. The mechanism, now ubiquitous in living cells, powers energy conversion in micro-organisms and in the

mitochondria of eukaryotes, making it a likely candidate for early life. Mitochondria produce

adenosine triphosphate

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is an organic compound that provides energy to drive many processes in living cells, such as muscle contraction, nerve impulse propagation, condensate dissolution, and chemical synthesis. Found in all known forms of ...

(ATP), the energy currency of the cell used to drive cellular processes such as chemical syntheses. The mechanism of ATP synthesis involves a closed membrane in which the

ATP synthase

ATP synthase is a protein that catalyzes the formation of the energy storage molecule adenosine triphosphate (ATP) using adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and inorganic phosphate (Pi). It is classified under ligases as it changes ADP by the formation ...

enzyme is embedded. The energy required to release strongly-bound ATP has its origin in

protons that move across the membrane.

In modern cells, those proton movements are caused by the pumping of ions across the membrane, maintaining an electrochemical gradient. In the first organisms, the gradient could have been provided by the difference in chemical composition between the flow from a

hydrothermal vent

A hydrothermal vent is a fissure on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hotspot ...

and the surrounding seawater,

or perhaps meteoric quinones that were conducive to the development of chemiosmotic energy across lipid membranes if at a terrestrial origin.

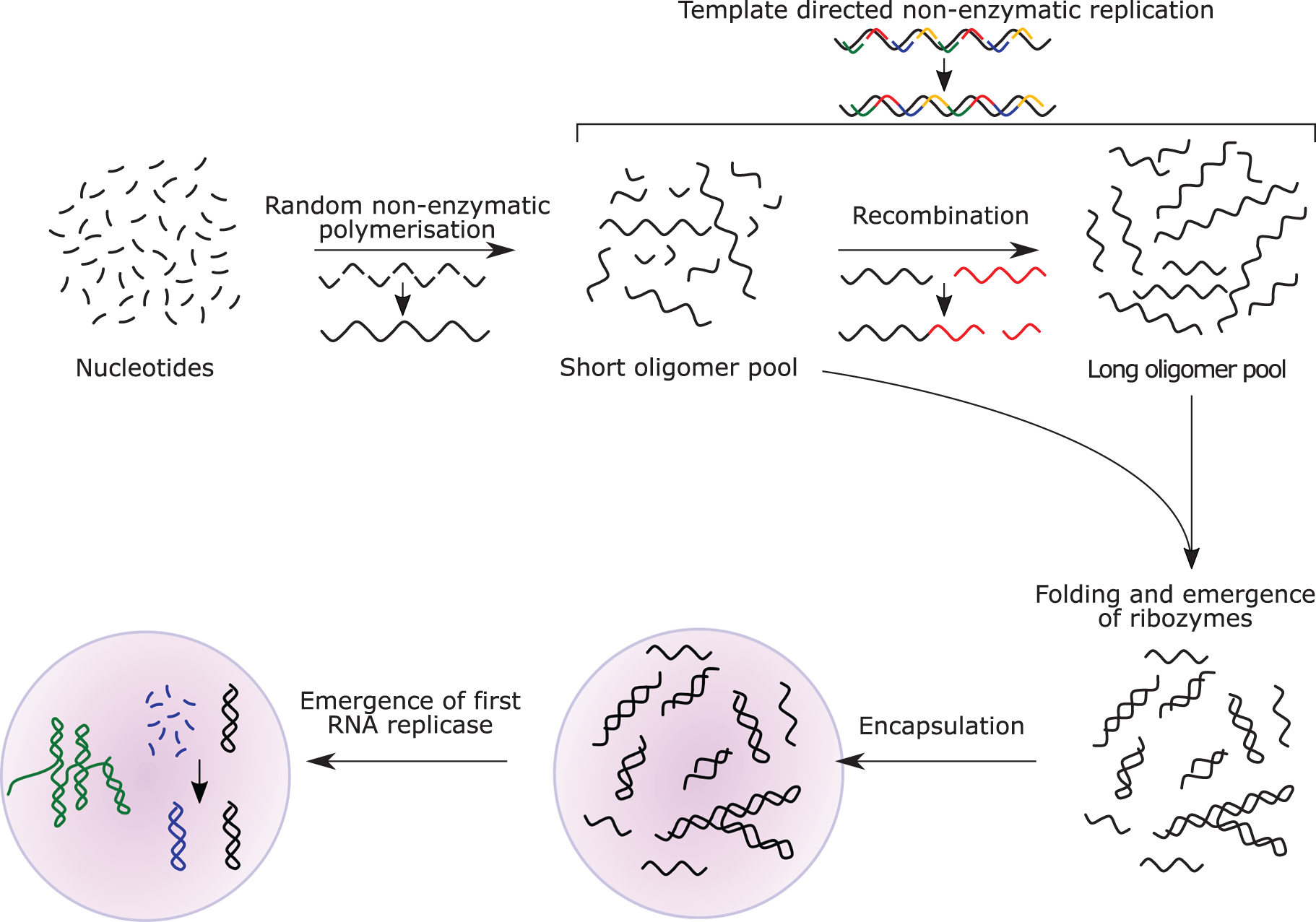

The RNA world

The

RNA world

The RNA world is a hypothetical stage in the evolutionary history of life on Earth, in which self-replicating RNA molecules proliferated before the evolution of DNA and proteins. The term also refers to the hypothesis that posits the existence ...

hypothesis describes an early Earth with self-replicating and catalytic RNA but no DNA or proteins. Many researchers concur that an RNA world must have preceded the DNA-based life that now dominates.

[*

*

* : "There is now strong evidence indicating that an RNA World did indeed exist before DNA- and protein-based life."

* : "]he RNA world's existence

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

has broad support within the community today." However, RNA-based life may not have been the first to exist.

Another model echoes Darwin's "warm little pond" with cycles of wetting and drying.

RNA is central to the translation process. Small RNAs can catalyze all the chemical groups and information transfers required for life.

RNA both expresses and maintains genetic information in modern organisms; and the chemical components of RNA are easily synthesized under the conditions that approximated the early Earth, which were very different from those that prevail today. The structure of the

ribozyme has been called the "smoking gun", with a central core of RNA and no amino acid side chains within 18

Å of the

active site

In biology and biochemistry, the active site is the region of an enzyme where substrate molecules bind and undergo a chemical reaction. The active site consists of amino acid residues that form temporary bonds with the substrate (binding site) ...

that catalyzes peptide bond formation.

The concept of the RNA world was proposed in 1962 by

Alexander Rich, and the term was coined by

Walter Gilbert in 1986.

There were initial difficulties in the explanation of the abiotic synthesis of the nucleotides

cytosine

Cytosine () (symbol C or Cyt) is one of the four nucleobases found in DNA and RNA, along with adenine, guanine, and thymine (uracil in RNA). It is a pyrimidine derivative, with a heterocyclic aromatic ring and two substituents attached (an amin ...

and

uracil. Subsequent research has shown possible routes of synthesis; for example, formamide produces all four

ribonucleotides and other biological molecules when warmed in the presence of various terrestrial minerals.

RNA replicase

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) or RNA replicase is an enzyme that catalyzes the replication of RNA from an RNA template. Specifically, it catalyzes synthesis of the RNA strand complementary to a given RNA template. This is in contrast to t ...

can function as both code and catalyst for further RNA replication, i.e. it can be

autocatalytic

A single chemical reaction is said to be autocatalytic if one of the reaction products is also a catalyst for the same or a coupled reaction.Steinfeld J.I., Francisco J.S. and Hase W.L. ''Chemical Kinetics and Dynamics'' (2nd ed., Prentice-Hall 199 ...

.

Jack Szostak

Jack William Szostak (born November 9, 1952) is a Canadian American biologist of Polish British descent, Nobel Prize laureate, university professor at the University of Chicago, former Professor of Genetics at Harvard Medical School, and Alexan ...

has shown that certain catalytic RNAs can join smaller RNA sequences together, creating the potential for self-replication. The RNA replication systems, which include two ribozymes that catalyze each other's synthesis, showed a doubling time of the product of about one hour, and were subject to Darwinian

natural selection under the experimental conditions.

If such conditions were present on early Earth, then natural selection would favor the proliferation of such

autocatalytic set

An autocatalytic set is a collection of entities, each of which can be created catalytically by other entities within the set, such that as a whole, the set is able to catalyze its own production. In this way the set ''as a whole'' is said to be ...

s, to which further functionalities could be added.

Self-assembly of RNA may occur spontaneously in hydrothermal vents.

A preliminary form of

tRNA

Transfer RNA (abbreviated tRNA and formerly referred to as sRNA, for soluble RNA) is an adaptor molecule composed of RNA, typically 76 to 90 nucleotides in length (in eukaryotes), that serves as the physical link between the mRNA and the amino a ...

could have assembled into such a replicator molecule.

Possible precursors to protein synthesis include the synthesis of short peptide cofactors or the self-catalysing duplication of RNA. It is likely that the ancestral ribosome was composed entirely of RNA, although some roles have since been taken over by proteins. Major remaining questions on this topic include identifying the selective force for the evolution of the ribosome and determining how the

genetic code

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

arose.

Eugene Koonin

Eugene Viktorovich Koonin (Russian: Евге́ний Ви́кторович Ку́нин; born October 26, 1956) is a Russian-American biologist and Senior Investigator at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). He is a recognise ...

has argued that "no compelling scenarios currently exist for the origin of replication and translation, the key processes that together comprise the core of biological systems and the apparent pre-requisite of biological evolution. The RNA World concept might offer the best chance for the resolution of this conundrum but so far cannot adequately account for the emergence of an efficient RNA replicase or the translation system."

Phylogeny and LUCA

Starting with the work of

Carl Woese

Carl Richard Woese (; July 15, 1928 – December 30, 2012) was an American microbiologist and biophysicist. Woese is famous for defining the Archaea (a new domain of life) in 1977 through a pioneering phylogenetic taxonomy of 16S ribosomal RNA, ...

from 1977 onwards,

genomics

Genomics is an interdisciplinary field of biology focusing on the structure, function, evolution, mapping, and editing of genomes. A genome is an organism's complete set of DNA, including all of its genes as well as its hierarchical, three-dim ...

studies have placed the

last universal common ancestor (LUCA) of all modern life-forms between

Bacteria and a clade formed by

Archaea and

Eukaryota in the phylogenetic tree of life. It lived over 4 Gya.

A minority of studies have placed the LUCA in Bacteria, proposing that Archaea and Eukaryota are evolutionarily derived from within Eubacteria;

Thomas Cavalier-Smith suggested that the phenotypically diverse bacterial phylum

Chloroflexota contained the LUCA.

Phylogenetic tree

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological spec ...

showing the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) at the root. The major clades are the Bacteria on one hand, and the Archaea and Eukaryota on the other.

In 2016, a set of 355

genes likely present in the LUCA was identified. A total of 6.1 million prokaryotic genes from Bacteria and Archaea were sequenced, identifying 355 protein clusters from amongst 286,514 protein clusters that were probably common to the LUCA. The results suggest that the LUCA was

anaerobic

Anaerobic means "living, active, occurring, or existing in the absence of free oxygen", as opposed to aerobic which means "living, active, or occurring only in the presence of oxygen." Anaerobic may also refer to:

* Anaerobic adhesive, a bonding a ...

with a

Wood–Ljungdahl pathway

The Wood–Ljungdahl pathway is a set of biochemical reactions used by some bacteria. It is also known as the reductive acetyl-coenzyme A (Acetyl-CoA) pathway. This pathway enables these organisms to use hydrogen as an electron donor, and ca ...

, nitrogen- and carbon-fixing, thermophilic. Its

cofactors

Cofactor may also refer to:

* Cofactor (biochemistry), a substance that needs to be present in addition to an enzyme for a certain reaction to be catalysed

* A domain parameter in elliptic curve cryptography, defined as the ratio between the order ...

suggest dependence upon an environment rich in

hydrogen, carbon dioxide,

iron, and

transition metals. Its genetic material was probably DNA, requiring the 4-nucleotide

genetic code

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

,

messenger RNA,

transfer RNAs, and

ribosomes to translate the code into

proteins such as

enzymes. LUCA likely inhabited an anaerobic

hydrothermal vent

A hydrothermal vent is a fissure on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hotspot ...

setting in a geochemically active environment. It was evidently already a complex organism, and must have had precursors; it was not the first living thing.

The physiology of LUCA has been in dispute.

File:LUCA systems and environment.svg, LUCA systems and environment

Leslie Orgel argued that early translation machinery for the genetic code would be susceptible to

error catastrophe

Error catastrophe refers to the cumulative loss of genetic information in a lineage of organisms due to high mutation rates. The mutation rate above which error catastrophe occurs is called the error threshold. Both terms were coined by Manfred ...

. Geoffrey Hoffmann however showed that such machinery can be stable in function against "Orgel's paradox".

Suitable geological environments

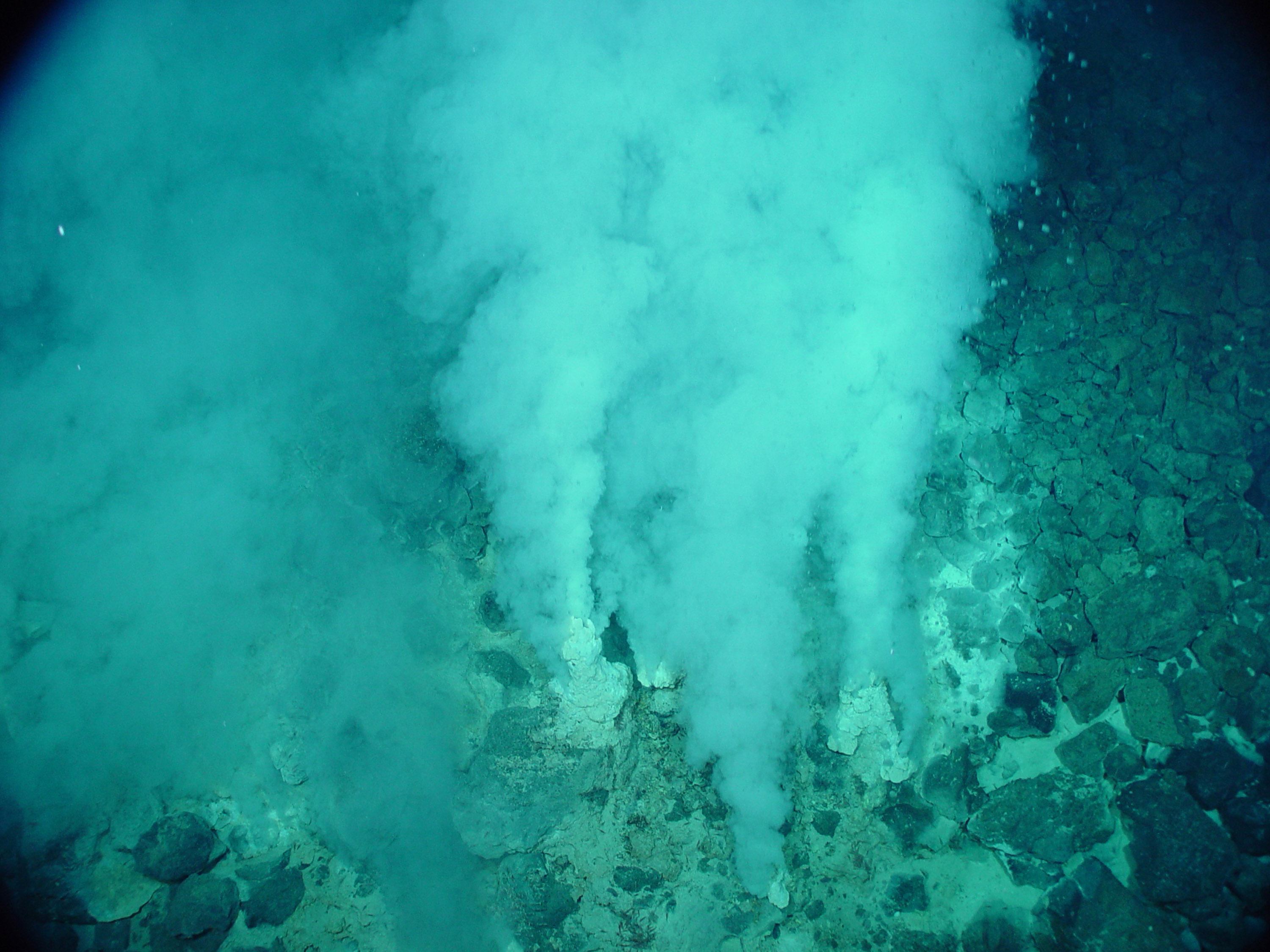

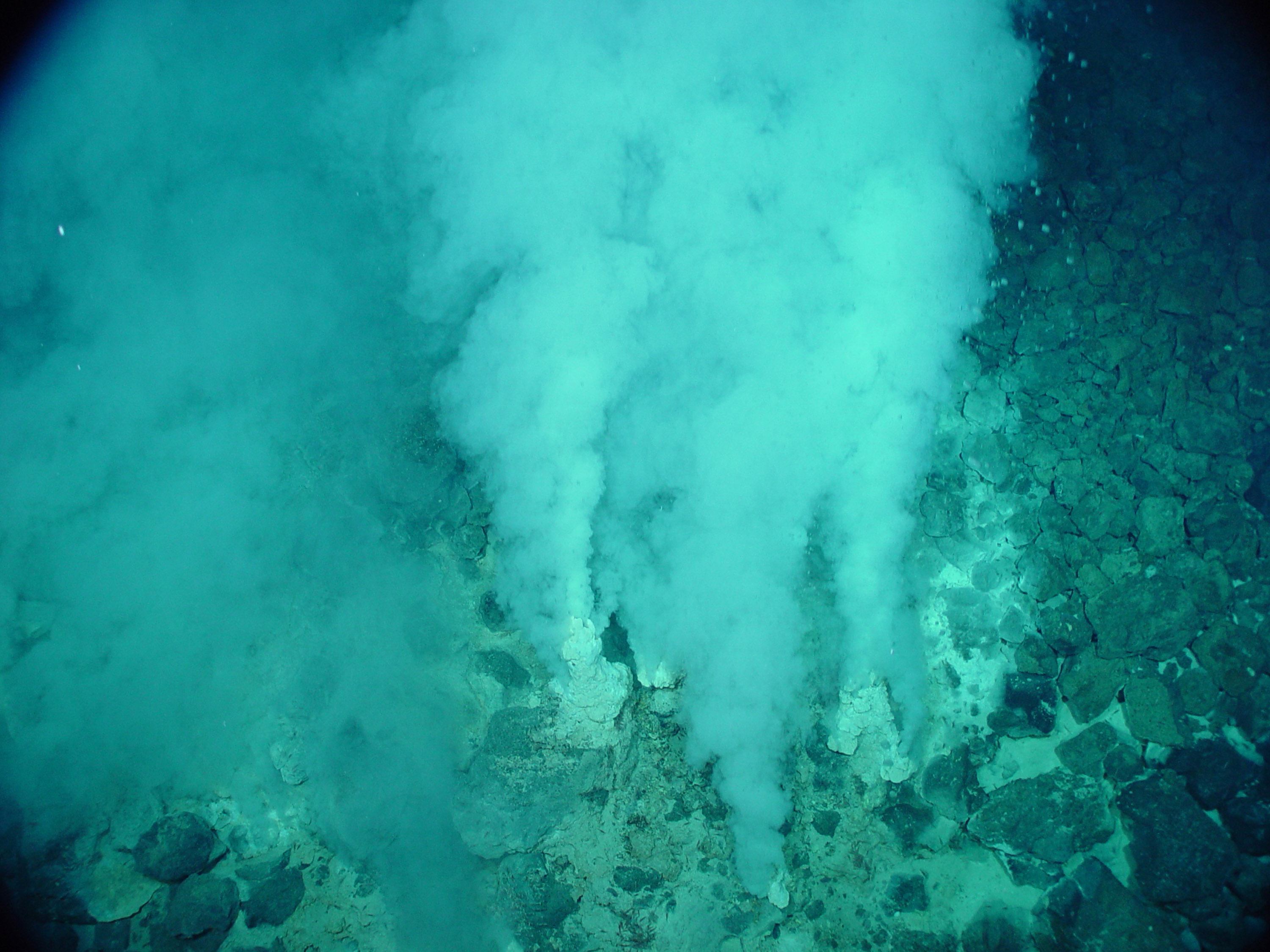

Deep sea hydrothermal vents

Early micro-fossils may have come from a hot world of gases such as

methane,

ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous wa ...

,

carbon dioxide and

hydrogen sulphide, toxic to much current life. Analysis of the

tree of life places thermophilic and hyperthermophilic

bacteria and

archaea closest to the root, suggesting that life may have evolved in a hot environment. The deep sea or alkaline

hydrothermal vent

A hydrothermal vent is a fissure on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hotspot ...

theory posits that life began at submarine hydrothermal vents.

Martin and Russell have suggested "that life evolved in structured iron monosulphide precipitates in a seepage site hydrothermal mound at a redox, pH, and temperature gradient between sulphide-rich hydrothermal fluid and iron(II)-containing waters of the Hadean ocean floor. The naturally arising, three-dimensional compartmentation observed within fossilized seepage-site metal sulphide precipitates indicates that these inorganic compartments were the precursors of cell walls and membranes found in free-living prokaryotes. The known capability of FeS and NiS to catalyze the synthesis of the acetyl-methylsulphide from carbon monoxide and methylsulphide, constituents of hydrothermal fluid, indicates that pre-biotic syntheses occurred at the inner surfaces of these metal-sulphide-walled compartments".

These form where hydrogen-rich fluids emerge from below the sea floor, as a result of

serpentinization

Serpentinization is a hydration and metamorphic transformation of ferromagnesian minerals, such as olivine and pyroxene, in mafic and ultramafic rock to produce serpentinite. Minerals formed by serpentinization include the serpentine group miner ...

of ultra-

mafic olivine with seawater and a pH interface with carbon dioxide-rich ocean water. The vents form a sustained chemical energy source derived from redox reactions, in which electron donors (molecular hydrogen) react with electron acceptors (carbon dioxide); see

Iron–sulfur world theory. These are

exothermic reactions.

Russell demonstrated that alkaline vents created an abiogenic

proton motive force

Chemiosmosis is the movement of ions across a semipermeable membrane bound structure, down their electrochemical gradient. An important example is the formation of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) by the movement of hydrogen ions (H+) across a membra ...

chemiosmotic gradient,

ideal for abiogenesis. Their microscopic compartments "provide a natural means of concentrating organic molecules," composed of iron-sulfur minerals such as

mackinawite

Mackinawite is an iron nickel sulfide mineral with the chemical formula (where x = 0 to 0.11). The mineral crystallizes in the tetragonal crystal system and has been described as a distorted, close packed, cubic array of S atoms with some of the ...

, endowed these mineral cells with the catalytic properties envisaged by

Günter Wächtershäuser.

This movement of ions across the membrane depends on a combination of two factors:

#

Diffusion force caused by concentration gradient—all particles including ions tend to diffuse from higher concentration to lower.

# Electrostatic force caused by electrical potential gradient—

cations

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convent ...

like

protons H

+ tend to diffuse down the electrical potential,

anions

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by con ...

in the opposite direction.

These two gradients taken together can be expressed as an

electrochemical gradient

An electrochemical gradient is a gradient of electrochemical potential, usually for an ion that can move across a membrane. The gradient consists of two parts, the chemical gradient, or difference in solute concentration across a membrane, and ...

, providing energy for abiogenic synthesis. The proton motive force can be described as the measure of the potential energy stored as a combination of proton and voltage gradients across a membrane (differences in proton concentration and electrical potential).

The surfaces of mineral particles inside deep-ocean hydrothermal vents have catalytic properties similar to those of enzymes and can create simple organic molecules, such as

methanol (CH

3OH),

formic,

acetic and

pyruvic acid

Pyruvic acid (CH3COCOOH) is the simplest of the alpha-keto acids, with a carboxylic acid and a ketone functional group. Pyruvate, the conjugate base, CH3COCOO−, is an intermediate in several metabolic pathways throughout the cell.

Pyruvic ac ...

s out of the dissolved CO

2 in the water, if driven by an applied voltage or by reaction with H

2 or H

2S.

The research reported by Martin in 2016 supports the thesis that life arose at hydrothermal vents, that spontaneous chemistry in the Earth's crust driven by rock–water interactions at disequilibrium thermodynamically underpinned life's origin and that the founding lineages of the archaea and bacteria were H

2-dependent autotrophs that used CO

2 as their terminal acceptor in energy metabolism. Martin suggests, based upon this evidence, that the LUCA "may have depended heavily on the geothermal energy of the vent to survive".

Pores at deep sea hydrothermal vents are suggested to have been occupied

by membrane-bound compartments which promoted biochemical reactions.

Hot springs

Mulkidjanian and co-authors think that marine environments did not provide the ionic balance and composition universally found in cells, or the ions required by essential proteins and ribozymes, especially with respect to high K

+/Na

+ ratio, Mn

2+, Zn

2+ and phosphate concentrations. They argue that the only environments that mimic the needed conditions on Earth are hot springs similar to ones at Kamchatka.

Mineral deposits in these environments under an anoxic atmosphere would have suitable pH (while current pools in an oxygenated atmosphere would not), contain precipitates of photocatalytic sulfide minerals that absorb harmful ultraviolet radiation, have wet-dry cycles that concentrate substrate solutions to concentrations amenable to spontaneous formation of biopolymers created both by chemical reactions in the hydrothermal environment, and by exposure to

UV light during transport from vents to adjacent pools that would promote the formation of biomolecules. The hypothesized pre-biotic environments are similar to hydrothermal vents, with additional components that help explain peculiarities of the LUCA.