demiurge on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In the Platonic, Neopythagorean, Middle Platonic, and Neoplatonic schools of

philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, the Demiurge () is an artisan

An artisan (from , ) is a skilled craft worker who makes or creates material objects partly or entirely by hand. These objects may be functional or strictly decorative, for example furniture, decorative art, sculpture, clothing, food ite ...

-like figure responsible for fashioning and maintaining the physical universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents. It comprises all of existence, any fundamental interaction, physical process and physical constant, and therefore all forms of matter and energy, and the structures they form, from s ...

. Various sects of Gnostics

Gnosticism (from Ancient Greek: , romanized: ''gnōstikós'', Koine Greek: �nostiˈkos 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems that coalesced in the late 1st century AD among early Christian sects. These diverse g ...

adopted the term ''demiurge''. Although a fashioner, the demiurge is not necessarily the same as the creator figure in the monotheistic

Monotheism is the belief that one God is the only, or at least the dominant deity.F. L. Cross, Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Monotheism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. A ...

sense, because the demiurge itself and the material from which the demiurge fashions the universe are both considered consequences of something else. Depending on the system, they may be considered either uncreated and eternal or the product of some other entity. Some of these systems are monotheistic, while others are henotheistic

Henotheism is the worship of a single, supreme god that does not deny the existence or possible existence of other deities that may be worshipped. Friedrich Schelling (1775–1854) coined the word, and Friedrich Welcker (1784–1868) ...

or polytheistic

Polytheism is the belief in or worship of more than one Deity, god. According to Oxford Reference, it is not easy to count gods, and so not always obvious whether an apparently polytheistic religion, such as Chinese folk religions, is really so, ...

.

The word ''demiurge'' is an English word derived from ''demiurgus'', a Latinised form of the Greek or . It was originally a common noun meaning "craftsman" or "artisan", but gradually came to mean "producer", and eventually "creator." The philosophical usage and the proper noun derive from Plato's ''Timaeus'', written 360 BC, where the demiurge is presented as the creator of the universe. The demiurge is also described as a creator in the Platonic ( 310–90 BC) and Middle Platonic ( 90 BC–AD 300) philosophical traditions. In the various branches of the Neoplatonic school (third century onwards), the demiurge is the fashioner of the real, perceptible world after the model of the Ideas, but (in most Neoplatonic systems) is still not itself " the One".

Within the vast spectrum of Gnostic traditions, views of the Demiurge range dramatically. It is generally understood and agreed upon to be a lesser divinity who governs the material universe. However, the nature of its rule over the material realm differs from sect to sect. Sethian Gnosticism portrays the Demiurge as an oppressive, ignorant ruler, intentionally binding souls in an inherently corrupt material realm. In contrast, Valentinian Gnosticism sees the Demiurge as a well-meaning but limited figure whose rule reflects ignorance rather than malice.

Plato and the ''Timaeus''

Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

, as the speaker Timaeus, refers to the Demiurge frequently in the Socratic dialogue

Socratic dialogue () is a genre of literary prose developed in Greece at the turn of the fourth century BC. The earliest ones are preserved in the works of Plato and Xenophon and all involve Socrates as the protagonist. These dialogues, and subse ...

'' Timaeus'' (28a ff.), 360 BC. The main character refers to the Demiurge as the entity who "fashioned and shaped" the material world. Timaeus describes the Demiurge as unreservedly benevolent, and so it desires a world as good as possible. The result of his work is a universe as a living god with lesser gods, such as the stars, planets, and gods of traditional religion, inside it. Plato argues that the cosmos needed a Demiurge because the cosmos needed a cause that makes Becoming resemble Being. ''Timaeus'' is a philosophical reconciliation of Hesiod's cosmology in his ''Theogony

The ''Theogony'' () is a poem by Hesiod (8th–7th century BC) describing the origins and genealogy, genealogies of the Greek gods, composed . It is written in the Homeric Greek, epic dialect of Ancient Greek and contains 1,022 lines. It is one ...

'', syncretically reconciling Hesiod to Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

, though other scholars have argued that Plato's theology 'invokes a broad cultural horizon without committing to any specific poetic or religious tradition'. Moreover, Plato believed that the Demiurge created other, so-called "lower" gods who, in turn, created humanity. Some scholars have argued that the lower gods are gods of traditional mythology, such as Zeus and Hera.

Gnosticism

Gnosticism

Gnosticism (from Ancient Greek language, Ancient Greek: , Romanization of Ancient Greek, romanized: ''gnōstikós'', Koine Greek: Help:IPA/Greek, �nostiˈkos 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems that coalesced ...

presents a distinction between the highest, unknowable God or Supreme Being and the demiurgic "creator" of the material, identified in some traditions with Yahweh

Yahweh was an Ancient Semitic religion, ancient Semitic deity of Weather god, weather and List of war deities, war in the History of the ancient Levant, ancient Levant, the national god of the kingdoms of Kingdom of Judah, Judah and Kingdom ...

, the God of the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

. '' Supreme Being, with his creation initially having the malevolent intention of entrapping aspects of the divine ''in'' materiality. In other systems, the Demiurge is instead portrayed as "merely" incompetent or foolish: his creation is an unconscious attempt to replicate the divine world (the

In the Archontic, Sethian, and Ophite systems, which have many affinities with the doctrine of Valentinus, the making of the world is ascribed to a company of seven

In the Archontic, Sethian, and Ophite systems, which have many affinities with the doctrine of Valentinus, the making of the world is ascribed to a company of seven

''Ennead'' II, 9, 6.

/ref> they attempt to conceal rather than admit their indebtedness to ancient philosophy, which they have corrupted by their extraneous and misguided embellishments. Thus their understanding of the Demiurge is similarly flawed in comparison to Plato's original intentions. Whereas Plato's Demiurge is good wishing good on his creation, Gnosticism contends that the Demiurge is not only the originator of evil but is evil as well. Hence the title of Plotinus' refutation: "Against Those That Affirm the Creator of the Kosmos and the Kosmos Itself to be Evil" (generally quoted as "Against the Gnostics"). Plotinus argues of the disconnect or great barrier that is created between the ''nous'' or mind's

Demiurgus

'' in ''A Dictionary of Christian Biography, Literature, Sects and Doctrines'' by William Smith and Henry Wace (1877), a publication now in the public domain.''

Dark Mirrors of Heaven: Gnostic Cosmogony

* * * * {{Plato navbox Conceptions of God Concepts in ancient Greek metaphysics Concepts in ancient Greek philosophy of mind Creator deities Demons in Gnosticism Gnostic cosmology Gnostic deities History of religion Metaphysical theories Names of God in Gnosticism Neoplatonism Timaeus (Plato) Religious philosophical concepts Theories in ancient Greek philosophy

. '' Supreme Being, with his creation initially having the malevolent intention of entrapping aspects of the divine ''in'' materiality. In other systems, the Demiurge is instead portrayed as "merely" incompetent or foolish: his creation is an unconscious attempt to replicate the divine world (the

pleroma

Pleroma (, literally "fullness") generally refers to the totality of divine powers. It is used in Christian theological contexts, as well as in Gnosticism. The term also appears in the Epistle to the Colossians, which is traditionally attributed ...

) based on faint recollections, and thus ends up fundamentally flawed. Thus, in such systems, the Demiurge is a proposed solution to the problem of evil

The problem of evil is the philosophical question of how to reconcile the existence of evil and suffering with an Omnipotence, omnipotent, Omnibenevolence, omnibenevolent, and Omniscience, omniscient God.The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ...

: while the divine beings are omniscient and omnibenevolent, the Demiurge who rules over our own physical world is not.

Angels

Psalm 82 begins, "God stands in the assembly of El , in the midst of the gods he renders judgment", indicating a plurality of gods, although it does not indicate that these gods were co-actors in creation.Philo

Philo of Alexandria (; ; ; ), also called , was a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher who lived in Alexandria, in the Roman province of Egypt.

The only event in Philo's life that can be decisively dated is his representation of the Alexandrian J ...

had inferred from the expression "Let us make man" of the Book of Genesis

The Book of Genesis (from Greek language, Greek ; ; ) is the first book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. Its Hebrew name is the same as its incipit, first word, (In the beginning (phrase), 'In the beginning'). Genesis purpor ...

that God had used other beings as assistants in the creation of man, and he explains in this way why man is capable of vice as well as virtue, ascribing the origin of the latter to God, of the former to his helpers in the work of creation.

The earliest Gnostic sects ascribe the work of creation to angels, some of them using the same passage in Genesis. So Irenaeus

Irenaeus ( or ; ; ) was a Greeks, Greek bishop noted for his role in guiding and expanding Christianity, Christian communities in the southern regions of present-day France and, more widely, for the development of Christian theology by oppos ...

tells of the system of Simon Magus, of the system of Menander, of the system of Saturninus, in which the number of these angels is reckoned as seven, and of the system of Carpocrates. In Basilides's system, he reports, the world was made by the angels who occupy the lowest heaven; but special mention is made of their chief, who is said to have been the God of the Jews, to have led that people out of the land of Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, and to have given them their law. The prophecies are ascribed not to the chief but to the other world-making angels.

The Latin translation, confirmed by Hippolytus of Rome

Hippolytus of Rome ( , ; Romanized: , – ) was a Bishop of Rome and one of the most important second–third centuries Christian theologians, whose provenance, identity and corpus remain elusive to scholars and historians. Suggested communitie ...

, makes Irenaeus

Irenaeus ( or ; ; ) was a Greeks, Greek bishop noted for his role in guiding and expanding Christianity, Christian communities in the southern regions of present-day France and, more widely, for the development of Christian theology by oppos ...

state that according to Cerinthus (who shows Ebionite influence), creation was made by a power quite separate from the Supreme God and ignorant of him. Theodoret, who here copies Irenaeus, turns this into the plural number "powers", and so Epiphanius of Salamis represents Cerinthus as agreeing with Carpocrates in the doctrine that the world was made by angels.

Yaldabaoth

In the Archontic, Sethian, and Ophite systems, which have many affinities with the doctrine of Valentinus, the making of the world is ascribed to a company of seven

In the Archontic, Sethian, and Ophite systems, which have many affinities with the doctrine of Valentinus, the making of the world is ascribed to a company of seven archons

''Archon'' (, plural: , ''árchontes'') is a Greek word that means "ruler", frequently used as the title of a specific public office. It is the masculine present participle of the verb stem , meaning "to be first, to rule", derived from the same ...

, whose names are given, but still more prominent is their chief, "Yaldabaoth" (also known as "Yaltabaoth" or "Ialdabaoth").

In the '' Apocryphon of John'' AD 120–180, the demiurge declares that he has made the world by himself:

Now theHe is demiurge and maker of man, but as a ray of light from above enters the body of man and gives him a soul, Yaldabaoth is filled with envy; he tries to limit man's knowledge by forbidding him the fruit of knowledge in paradise. At the consummation of all things, all light will return to thearchon ''Archon'' (, plural: , ''árchontes'') is a Greek word that means "ruler", frequently used as the title of a specific public office. It is the masculine present participle of the verb stem , meaning "to be first, to rule", derived from the same ...ruler"who is weak has three names. The first name is Yaltabaoth, the second is Saklas fool" and the third is Samael blind god" And he is impious in his arrogance which is in him. For he said, 'I am God and there is no other God beside me,' for he is ignorant of his strength, the place from which he had come.

Pleroma

Pleroma (, literally "fullness") generally refers to the totality of divine powers. It is used in Christian theological contexts, as well as in Gnosticism. The term also appears in the Epistle to the Colossians, which is traditionally attributed ...

. But Yaldabaoth, the demiurge, with the material world, will be cast into the lower depths.

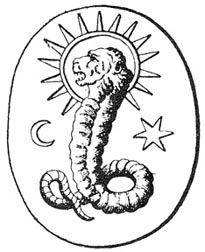

Yaldabaoth is frequently called "the Lion-faced", ''leontoeides'', and is said to have the body of a serpent. The demiurge is also described as having a fiery nature, applying the words of Moses to him: "the Lord our God is a burning and consuming fire". Hippolytus claims that Simon used a similar description.

In '' Pistis Sophia'', Yaldabaoth has already sunk from his high estate and resides in Chaos, where, with his forty-nine demons, he tortures wicked souls in boiling rivers of pitch, and with other punishments (pp. 257, 382). He is an archon with the face of a lion, half flame, and half darkness.

In the Nag Hammadi text '' On the Origin of the World'', the three sons of Yaldabaoth are listed as Yao, Eloai, and Astaphaios.

Under the name of ''Nebro'' (rebel), Yaldabaoth is called an angel in the apocryphal ''Gospel of Judas

The Gospel of Judas is a non-canonical religious text. Its content consists of conversations between Jesus and his disciples, especially Judas Iscariot. The only copy of it known to exist is a Coptic language text that is part of the Codex ...

''. He is first mentioned in "The Cosmos, Chaos, and the Underworld" as one of the twelve angels to come "into being orule over chaos and the nderworld. He comes from heaven, and it is said his "face flashed with fire and isappearance was defiled with blood". Nebro creates six angels in addition to the angel Saklas to be his assistants. These six, in turn, create another twelve angels "with each one receiving a portion in the heavens".

Names

The etymology of the name ''Yaldabaoth'' has been subject to many speculative theories. Until 1974, etymologies deriving from the unattestedAramaic

Aramaic (; ) is a Northwest Semitic language that originated in the ancient region of Syria and quickly spread to Mesopotamia, the southern Levant, Sinai, southeastern Anatolia, and Eastern Arabia, where it has been continually written a ...

: בהותא, romanized: ''bāhūthā'', supposedly meaning " chaos", represented the majority view. Following an analysis by the Jewish historian of religion Gershom Scholem published in 1974, this etymology no longer enjoyed any notable support. His analysis showed the unattested Aramaic term to have been fabulated and attested only in a single corrupted text from 1859, with its claimed translation having been transposed from the reading of an earlier etymology, whose explanation seemingly equated " darkness" and "chaos" when translating an unattested supposed plural form of .

" Samael" literally means "Blind God" or "God of the Blind" in Hebrew (). This being is considered not only blind, or ignorant of its own origins, but may, in addition, be evil; its name is also found in Judaism

Judaism () is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic, Monotheism, monotheistic, ethnic religion that comprises the collective spiritual, cultural, and legal traditions of the Jews, Jewish people. Religious Jews regard Judaism as their means of o ...

as the Angel of Death and in Christian demonology. This link to Judeo-Christian tradition leads to a further comparison with Satan

Satan, also known as the Devil, is a devilish entity in Abrahamic religions who seduces humans into sin (or falsehood). In Judaism, Satan is seen as an agent subservient to God, typically regarded as a metaphor for the '' yetzer hara'', or ' ...

. Another alternative title for the demiurge is "Saklas", Aramaic for "fool". In the '' Apocryphon of John'', Yaldabaoth is also known as both Sakla and Samael. Marvin Meyer and James M. Robinson, ''The Nag Hammadi Scriptures: The International Edition''. HarperOne, 2007.

The angelic name " Ariel" (Hebrew: 'the lion of God') has also been used to refer to the Demiurge and is called his "perfect" name; in some Gnostic lore, Ariel has been called an ancient or original name for Ialdabaoth. The name has also been inscribed on amulets as "Ariel Ialdabaoth", and the figure of the archon inscribed with "Aariel".

Marcion

According to Marcion, the title God was given to the Demiurge, who was to be sharply distinguished from the higher Good God. The former was ''díkaios'', severely just, the latter ''agathós'', or loving-kind; the former was the "god of this world", the God of theOld Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

, the latter the true God of the New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

. Christ, in reality, is the Son of the Good God. The true believer in Christ entered into God's kingdom; the unbeliever remained forever the slave of the Demiurge.

Valentinus

It is in the system of Valentinus that the name ''Dēmiurgos'' is used, which occurs nowhere in Irenaeus except in connection with the Valentinian system. When it is employed by other Gnostics either it is not used in a technical sense, or its use has been borrowed from Valentinus. But it is only the name that can be said to be specially Valentinian; the personage intended by it corresponds more or less closely with the Yaldabaoth of the Ophites, the great Archon of Basilides, the Elohim of Justinus, etc. The Valentinian theory elaborates that from Achamoth (''he kátō sophía'' or lower wisdom) three kinds of substance take their origin, the spiritual (''pneumatikoí''), the animal (''psychikoí'') and the material (''hylikoí''). The Demiurge belongs to the second kind, as he was the offspring of a union of Achamoth with matter. And as Achamoth herself was only the daughter of '' Sophía'' the last of the thirty Aeons, the Demiurge was distant by many emanations from the Propatôr, or Supreme God. In creating this world out of Chaos the Demiurge was unconsciously influenced for good; and the universe, to the surprise even of its Maker, became almost perfect. The Demiurge regretted even its slight imperfection, and as he thought himself the Supreme God, he attempted to remedy this by sending a Messiah. To this Messiah, however, was actually united with Jesus the Saviour, Who redeemed men. These are either ''hylikoí'' or ''pneumatikoí''. The first, or material men, will return to the grossness of matter and finally be consumed by fire; the second, or animal men, together with the Demiurge, will enter a middle state, neither Pleroma nor ''hyle''; the purely spiritual men will be completely freed from the influence of the Demiurge and together with the Saviour and Achamoth, his spouse, will enter the Pleroma divested of body (''hyle'') and soul (''psyché''). In this most common form of Gnosticism the Demiurge had an inferior though not intrinsically evil function in the universe as the head of the animal, or psychic world.The devil

Opinions on the devil, and his relationship to the Demiurge, vary. The Ophites held that he and his demons constantly oppose and thwart the human race, as it was on their account the devil was cast down into this world. According to one variant of the Valentinian system, the Demiurge is also the maker, out of the appropriate substance, of an order of ''spiritual'' beings, the devil, the prince of this world, and his angels. But the devil, as being a ''spirit'' of wickedness, is able to recognise the higher spiritual world, of which his maker the Demiurge, who is only animal, has no real knowledge. The devil resides in this lower world, of which he is the prince, the Demiurge in the heavens; his mother Sophia in the middle region, above the heavens and below the Pleroma. The Valentinian Heracleon interpreted the devil as the ''principle'' of evil, that of ''hyle'' (matter). As he writes in his commentary on John 4:21,The mountain represents the Devil, or his world, since the Devil was one part of the whole of matter, but the world is the total mountain of evil, a deserted dwelling place of beasts, to which all who lived before the law and all Gentiles render worship. But Jerusalem represents the creation or the Creator whom the Jews worship. ... You then who are spiritual should worship neither the creation nor the Craftsman, but the Father of Truth.This vilification of the creator was held to be inimical to Christianity by the early fathers of the church. In refuting the beliefs of the gnostics,

Irenaeus

Irenaeus ( or ; ; ) was a Greeks, Greek bishop noted for his role in guiding and expanding Christianity, Christian communities in the southern regions of present-day France and, more widely, for the development of Christian theology by oppos ...

stated that "Plato is proved to be more religious than these men, for he allowed that the same God was both just and good, having power over all things, and himself executing judgment."

Platonism

Middle Platonism

In Numenius's Neo-Pythagorean and Middle Platonistcosmogony

Cosmogony is any model concerning the origin of the cosmos or the universe.

Overview

Scientific theories

In astronomy, cosmogony is the study of the origin of particular astrophysical objects or systems, and is most commonly used in ref ...

, the Demiurge is second God as the ''nous

''Nous'' (, ), from , is a concept from classical philosophy, sometimes equated to intellect or intelligence, for the cognitive skill, faculty of the human mind necessary for understanding what is truth, true or reality, real.

Alternative Eng ...

'' or thought of intelligibles and sensibles

Plotinus

The work of Plotinus and other later Platonists in the 3rd century AD to further clarify the Demiurge is known asNeoplatonism

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common id ...

. To Plotinus, the second emanation represents an uncreated second cause (see Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos (; BC) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher, polymath, and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His political and religious teachings were well known in Magna Graecia and influenced the philosophies of P ...

' Dyad). Plotinus sought to reconcile Aristotle's '' energeia'' with Plato's Demiurge, which, as Demiurge and mind (''nous''), is a critical component in the ontological

Ontology is the philosophical study of being. It is traditionally understood as the subdiscipline of metaphysics focused on the most general features of reality. As one of the most fundamental concepts, being encompasses all of reality and every ...

construct of human consciousness used to explain and clarify substance theory

Substance theory, or substance–attribute theory, is an ontological theory positing that objects are constituted each by a ''substance'' and properties borne by the substance but distinct from it. In this role, a substance can be referred to as ...

within Platonic realism

The Theory of Forms or Theory of Ideas, also known as Platonic idealism or Platonic realism, is a philosophical theory credited to the Classical Greek philosopher Plato.

A major concept in metaphysics, the theory suggests that the physical w ...

(also called idealism

Idealism in philosophy, also known as philosophical realism or metaphysical idealism, is the set of metaphysics, metaphysical perspectives asserting that, most fundamentally, reality is equivalent to mind, Spirit (vital essence), spirit, or ...

). In order to reconcile Aristotelian with Platonian philosophy, Plotinus metaphorically identified the demiurge (or ''nous'') within the pantheon of the Greek Gods as Zeus

Zeus (, ) is the chief deity of the List of Greek deities, Greek pantheon. He is a sky father, sky and thunder god in ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, who rules as king of the gods on Mount Olympus.

Zeus is the child ...

.

Henology

The first and highest aspect of God is described by Plato as the One (Τὸ Ἕν, 'To Hen'), the source, or the Monad. This is the God above the Demiurge, and manifests through the actions of the Demiurge. The Monad emanated the demiurge or ''Nous

''Nous'' (, ), from , is a concept from classical philosophy, sometimes equated to intellect or intelligence, for the cognitive skill, faculty of the human mind necessary for understanding what is truth, true or reality, real.

Alternative Eng ...

'' (consciousness) from its "indeterminate" vitality due to the monad being so abundant that it overflowed back onto itself, causing self-reflection. This self-reflection of the indeterminate vitality was referred to by Plotinus as the "Demiurge" or creator. The second principle is organization in its reflection of the nonsentient force or '' dynamis'', also called the one or the Monad. The dyad is ''energeia'' emanated by the one that is then the work, process or activity called ''nous'', Demiurge, mind, consciousness that organizes the indeterminate vitality into the experience called the material world, universe, cosmos. Plotinus also elucidates the equation of matter with nothing or non-being in '' The Enneads'' which more correctly is to express the concept of idealism

Idealism in philosophy, also known as philosophical realism or metaphysical idealism, is the set of metaphysics, metaphysical perspectives asserting that, most fundamentally, reality is equivalent to mind, Spirit (vital essence), spirit, or ...

or that there is not anything or anywhere outside of the "mind" or ''nous'' (cf. pantheism).

Plotinus' form of Platonic idealism is to treat the Demiurge, ''nous'', as the contemplative faculty (''ergon'') within man which orders the force (''dynamis'') into conscious reality. In this, he claimed to reveal Plato's true meaning: a doctrine he learned from Platonic tradition that did not appear outside the academy or in Plato's text. This tradition of creator God as ''nous'' (the manifestation of consciousness), can be validated in the works of pre-Plotinus philosophers such as Numenius, as well as a connection between Hebrew and Platonic cosmology (see also Philo

Philo of Alexandria (; ; ; ), also called , was a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher who lived in Alexandria, in the Roman province of Egypt.

The only event in Philo's life that can be decisively dated is his representation of the Alexandrian J ...

).

The Demiurge of Neoplatonism is the ''Nous'' (mind of God), and is one of the three ordering principles:

* '' Arche'' (Gr. 'beginning') – the source of all things,

* ''Logos

''Logos'' (, ; ) is a term used in Western philosophy, psychology and rhetoric, as well as religion (notably Logos (Christianity), Christianity); among its connotations is that of a rationality, rational form of discourse that relies on inducti ...

'' (Gr. 'reason/cause') – the underlying order that is hidden beneath appearances,

* ''Harmonia

In Greek mythology, Harmonia (; /Ancient Greek phonology, harmoˈnia/, "harmony", "agreement") is the goddess of harmony and concord. Her Greek opposite is Eris (mythology), Eris and her Roman mythology, Roman counterpart is Concordia (mythol ...

'' (Gr. 'harmony') – numerical ratios

In mathematics, a ratio () shows how many times one number contains another. For example, if there are eight oranges and six lemons in a bowl of fruit, then the ratio of oranges to lemons is eight to six (that is, 8:6, which is equivalent to th ...

in mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

.

Before Numenius of Apamea and Plotinus' '' Enneads'', no Platonic works ontologically clarified the Demiurge from the allegory

As a List of narrative techniques, literary device or artistic form, an allegory is a wikt:narrative, narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a meaning with moral or political signi ...

in Plato's ''Timaeus''. The idea of Demiurge was, however, addressed before Plotinus in the works of Christian writer Justin Martyr

Justin, known posthumously as Justin Martyr (; ), also known as Justin the Philosopher, was an early Christian apologist and Philosophy, philosopher.

Most of his works are lost, but two apologies and a dialogue did survive. The ''First Apolog ...

who built his understanding of the Demiurge on the works of Numenius.

Plotinus' ''Against the Gnostics''

Gnosticism attributed falsehood or evil to the concept of the Demiurge or creator, though in some Gnostic traditions the creator is from a fallen, ignorant, or lesser—rather than evil—perspective, such as that of Valentinius. The Neoplatonic philosopher Plotinus addressed within his works Gnosticism's conception of the Demiurge, which he saw as un- Hellenic and blasphemous to the Demiurge or creator of Plato. Plotinus, along with his teacherAmmonius Saccas

Ammonius Saccas (; ; 175 AD243 AD) was a Hellenistic Platonist self-taught philosopher from Alexandria, generally regarded as the precursor of Neoplatonism or one of its founders. He is mainly known as the teacher of Plotinus, whom he taught f ...

, was the founder of Neoplatonism

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common id ...

. In the ninth tractate of the second of his ''Enneads'', Plotinus criticizes his opponents for their appropriation of ideas from Plato:

Of note here is the remark concerning the second hypostasis or Creator and third hypostasis or World Soul. Plotinus criticizes his opponents for "all the novelties through which they seek to establish a philosophy of their own" which, he declares, "have been picked up outside of the truth";"For, in sum, a part of their doctrine comes from Plato; all the novelties through which they seek to establish a philosophy of their own have been picked up outside of the truth." Plotinus, "Against the Gnostics"''Ennead'' II, 9, 6.

/ref> they attempt to conceal rather than admit their indebtedness to ancient philosophy, which they have corrupted by their extraneous and misguided embellishments. Thus their understanding of the Demiurge is similarly flawed in comparison to Plato's original intentions. Whereas Plato's Demiurge is good wishing good on his creation, Gnosticism contends that the Demiurge is not only the originator of evil but is evil as well. Hence the title of Plotinus' refutation: "Against Those That Affirm the Creator of the Kosmos and the Kosmos Itself to be Evil" (generally quoted as "Against the Gnostics"). Plotinus argues of the disconnect or great barrier that is created between the ''nous'' or mind's

noumenon

In philosophy, a noumenon (, ; from ; : noumena) is knowledge posited as an Object (philosophy), object that exists independently of human sense. The term ''noumenon'' is generally used in contrast with, or in relation to, the term ''Phenomena ...

(see Heraclitus

Heraclitus (; ; ) was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic philosopher from the city of Ephesus, which was then part of the Achaemenid Empire, Persian Empire. He exerts a wide influence on Western philosophy, ...

) and the material world (phenomenon

A phenomenon ( phenomena), sometimes spelled phaenomenon, is an observable Event (philosophy), event. The term came into its modern Philosophy, philosophical usage through Immanuel Kant, who contrasted it with the noumenon, which ''cannot'' be ...

) by believing the material world is evil.

The majority of scholars tend to understand Plotinus' opponents as being a Gnostic sect—certainly (specifically Sethian), several such groups were present in Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

and elsewhere about the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

during Plotinus' lifetime. Plotinus specifically points to the Gnostic doctrine of Sophia and her emission of the Demiurge.

Though the former understanding certainly enjoys the greatest popularity, the identification of Plotinus' opponents as Gnostic is not without some contention. Christos Evangeliou has contended that Plotinus' opponents might be better described as simply "Christian Gnostics", arguing that several of Plotinus' criticisms are as applicable to orthodox Christian doctrine as well. Also, considering the evidence from the time, Evangeliou thought the definition of the term "Gnostics" was unclear. Of note here is that while Plotinus' student Porphyry names Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

specifically in Porphyry's own works, and Plotinus is to have been a known associate of the Christian Origen

Origen of Alexandria (), also known as Origen Adamantius, was an Early Christianity, early Christian scholar, Asceticism#Christianity, ascetic, and Christian theology, theologian who was born and spent the first half of his career in Early cent ...

, none of Plotinus' works mention Christ or Christianity—whereas Plotinus specifically addresses his target in the ''Enneads'' as the Gnostics.

A. H. Armstrong identified the so-called "Gnostics" that Plotinus was attacking as Jewish and Pagan, in his introduction to the tract in his translation of the ''Enneads''. Armstrong alluding to Gnosticism being a Hellenic philosophical heresy of sorts, which later engaged Christianity and Neoplatonism.

John D. Turner, professor of religious studies at the University of Nebraska, and famed translator and editor of the Nag Hammadi library

The Nag Hammadi library (also known as the Chenoboskion Manuscripts and the Gnostic Gospels) is a collection of early Christian and Gnostic texts discovered near the Upper Egyptian town of Nag Hammadi in 1945.

Thirteen leather-bound papyrus c ...

, stated that the text Plotinus and his students read was Sethian Gnosticism, which predates Christianity. It appears that Plotinus attempted to clarify how the philosophers of the academy had not arrived at the same conclusions (such as dystheism or misotheism for the creator God as an answer to the problem of evil

The problem of evil is the philosophical question of how to reconcile the existence of evil and suffering with an Omnipotence, omnipotent, Omnibenevolence, omnibenevolent, and Omniscience, omniscient God.The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ...

) as the targets of his criticism.

Iamblichus

Later, the Neoplatonist Iamblichus changed the role of the "One", effectively altering the role of the Demiurge as second cause or dyad, which was one of the reasons that Iamblichus and his teacher Porphyry came into conflict. The figure of the Demiurge emerges in the theoretic of Iamblichus, which conjoins the transcendent, incommunicable “One,” or Source. Here, at the summit of this system, the Source and Demiurge (material realm) coexist via the process of '' henosis''. Iamblichus describes the One as a monad whose first principle or emanation is intellect (''nous''), while among "the many" that follow it there is a second, super-existent "One" that is the producer of intellect or soul (''psyche''). The "One" is further separated into spheres of intelligence; the first and superior sphere is objects of thought, while the latter sphere is the domain of thought. Thus, a triad is formed of the intelligible ''nous'', the intellective ''nous'', and the '' psyche'' in order to reconcile further the various Hellenistic philosophical schools ofAristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

's ''actus'' and ''potentia'' (actuality and potentiality) of the unmoved mover

The unmoved mover () or prime mover () is a concept advanced by Aristotle as a primary cause (or first uncaused cause) or " mover" of all the motion in the universe. As is implicit in the name, the moves other things, but is not itself moved by ...

and Plato's Demiurge.

Then within this intellectual triad Iamblichus assigns the third rank to the Demiurge, identifying it with the perfect or Divine ''nous'' with the intellectual triad being promoted to a ''hebdomad'' (pure intellect).

In the theoretic of Plotinus, ''nous'' produces nature through intellectual mediation, thus the intellectualizing gods are followed by a triad of psychic gods.

Later representations

Cathars

Catharism apparently inherited their idea of Satan as the creator of the evil world from Gnosticism.Gilles Quispel

Gilles Quispel (30 May 1916 – 2 March 2006) was a Dutch theologian and historian of Christianity and Gnosticism. He was professor of early Christian history at Utrecht University.

Early life and education

Born in Rotterdam, he was the son of ...

writes, "There is a direct link between ancient Gnosticism and Catharism. The Cathars held that the creator of the world, Satanael, had usurped the name of God, but that he had subsequently been unmasked and told that he was not really God."Quispel, Gilles and Van Oort, Johannes (2008), p. 143.

Modern influence

Emil Cioran also wrote his ''Le mauvais démiurge'' ("The Evil Demiurge"), published in 1969, influenced by Gnosticism and Schopenhauerian interpretation of Platonic ontology, as well as that of Plotinus.See also

* Albinus (philosopher) * Azazil * Devil in Christianity * Problem of the creator of God * Tenth intellect (Isma'ilism) * UrizenReferences

Notes

Sources

* 'Demiurgus

'' in ''A Dictionary of Christian Biography, Literature, Sects and Doctrines'' by William Smith and Henry Wace (1877), a publication now in the public domain.''

External links

Dark Mirrors of Heaven: Gnostic Cosmogony

* * * * {{Plato navbox Conceptions of God Concepts in ancient Greek metaphysics Concepts in ancient Greek philosophy of mind Creator deities Demons in Gnosticism Gnostic cosmology Gnostic deities History of religion Metaphysical theories Names of God in Gnosticism Neoplatonism Timaeus (Plato) Religious philosophical concepts Theories in ancient Greek philosophy