William Buckland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

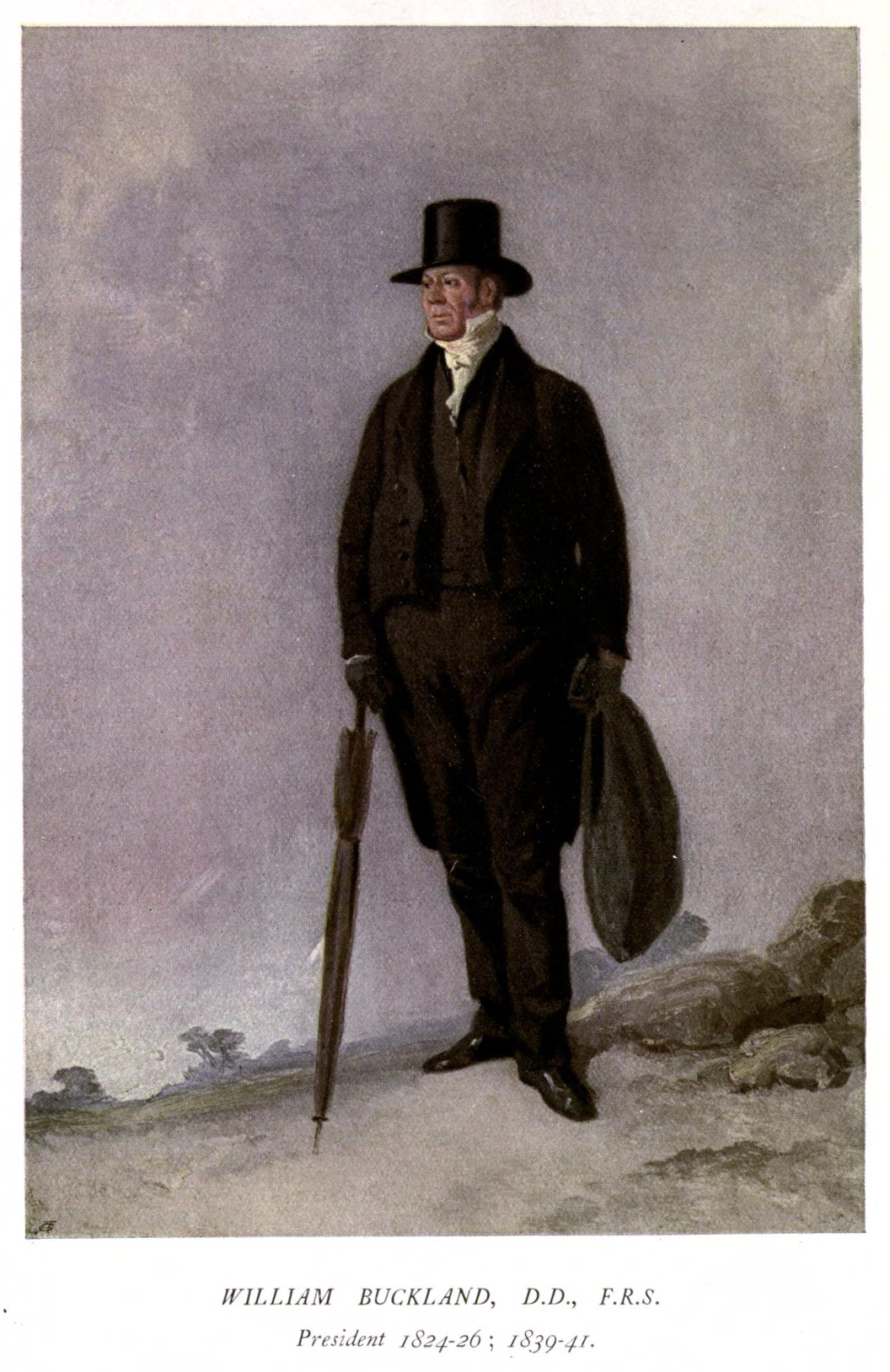

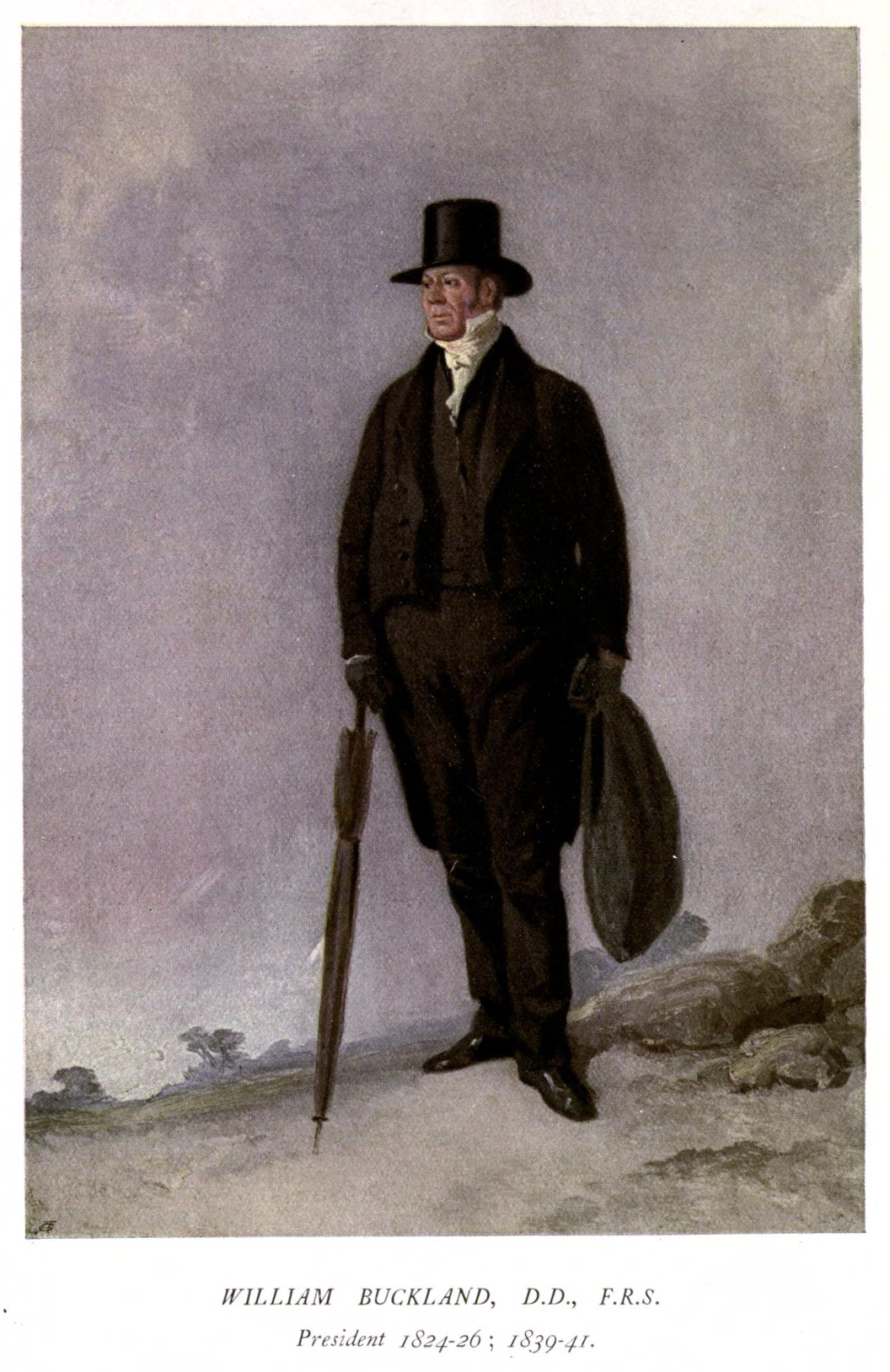

William Buckland DD, FRS (12 March 1784 – 14 August 1856) was an English theologian,

Buckland was born at

Buckland was born at

He continued to live in Corpus Christi College and, in 1824, he became president of the Geological Society of London. Here he announced the discovery, at Stonesfield, of fossil bones of a giant

He continued to live in Corpus Christi College and, in 1824, he became president of the Geological Society of London. Here he announced the discovery, at Stonesfield, of fossil bones of a giant

The fossil hunter

The fossil hunter

Buckland was commissioned to contribute one of the set of eight ''

Buckland was commissioned to contribute one of the set of eight ''

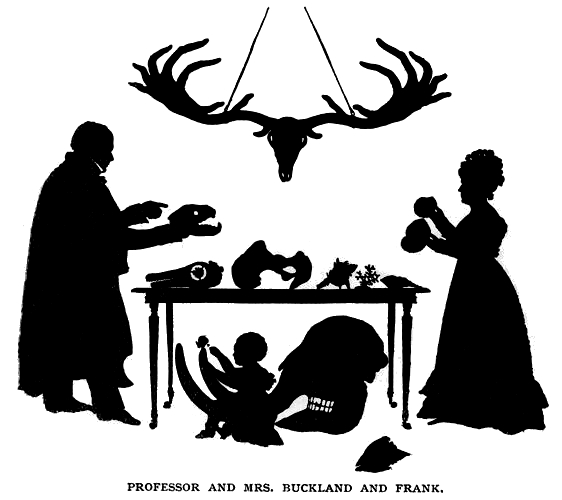

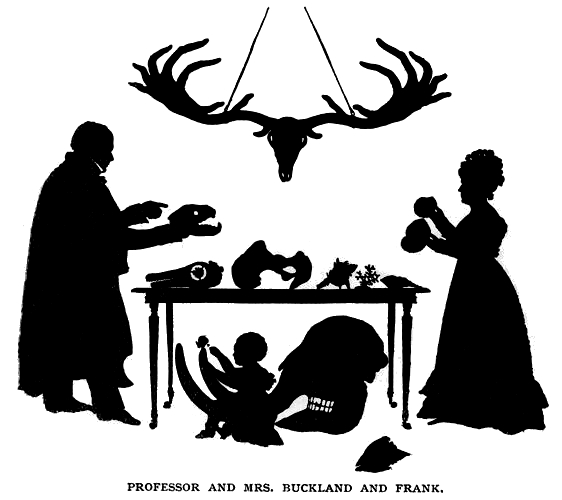

/ref> When he lectured indoors he would bring his presentations to life by imitating the movements of the dinosaurs under discussion. Buckland's passion for scientific observation and experiment extended to his home, where he had a table inlaid with

/ref> Not only was William Buckland's home filled with specimens – animal as well as mineral, live as well as dead – but he claimed to have eaten his way through the animal kingdom. Reportedly according to an anecdote recounted by Augustus Hare, the most distasteful animals Buckland consumed were in his opinion mole and bluebottle fly. Ostrich, hedgehogs, mice, frogs and snails, were among other animals reportedly served to guests. Buckland was followed in this hobby by his son Frank. One story recounted by Peter Lund Simmonds in 1859 reports that Buckland served soup to his guests before claiming that it was an alligator that he had dissected earlier that day, to the guests significant discomfort. When asked if he had really served an alligator, he reportedly responded "as good a calf's head as ever wore a coronet". According to one story, Buckland consumed, perhaps unintentionally, a portion of the mummified heart of the French King

Buckland at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History''The Life and Correspondence of William Buckland... By his daughter, Mrs. Gordon''

(London : J. Murray, 1894) – digital facsimile available from

''Reliquiæ Diluvianæ''

(English) – digital facsimile available from

here

{{DEFAULTSORT:Buckland, William 1784 births 1856 deaths Presidents of the Geological Society of London People from Axminster Catastrophism Christian Old Earth creationists British Christian creationists Doctors of Divinity English Anglicans People educated at Blundell's School Alumni of Corpus Christi College, Oxford English geologists English palaeontologists Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Fellows of the Royal Society Fellows of Christ Church, Oxford Deans of Westminster Recipients of the Copley Medal Wollaston Medal winners Fellows of the Geological Society of London 19th-century English scientists 18th-century English people 19th-century English people People educated at Winchester College Enlightenment scientists Parson-naturalists Writers about religion and science Authors of the Bridgewater Treatises People associated with the Ashmolean Museum

geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the structure, composition, and History of Earth, history of Earth. Geologists incorporate techniques from physics, chemistry, biology, mathematics, and geography to perform research in the Field research, ...

and palaeontologist

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geolo ...

.

His work in the early 1820s proved that Kirkdale Cave in North Yorkshire

North Yorkshire is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in Northern England.The Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority areas of City of York, York and North Yorkshire (district), North Yorkshire are in Yorkshire and t ...

had been a prehistoric hyena

Hyenas or hyaenas ( ; from Ancient Greek , ) are feliform carnivoran mammals belonging to the family Hyaenidae (). With just four extant species (each in its own genus), it is the fifth-smallest family in the order Carnivora and one of the sma ...

den, for which he was awarded the Copley Medal

The Copley Medal is the most prestigious award of the Royal Society of the United Kingdom, conferred "for sustained, outstanding achievements in any field of science". The award alternates between the physical sciences or mathematics and the bio ...

. It was praised as an example of how scientific analysis could reconstruct events in the distant past. He pioneered the use of fossilised faeces

Feces (also known as faeces American and British English spelling differences#ae and oe, or fæces; : faex) are the solid or semi-solid remains of food that was not digested in the small intestine, and has been broken down by bacteria in the ...

in reconstructing ecosystems, coining the term coprolite

A coprolite (also known as a coprolith) is fossilized feces. Coprolites are classified as trace fossils as opposed to body fossils, as they give evidence for the animal's behaviour (in this case, diet) rather than morphology. The name ...

s. Buckland also wrote the first full account of a fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

, which he named ''Megalosaurus

''Megalosaurus'' (meaning "great lizard", from Ancient Greek, Greek , ', meaning 'big', 'tall' or 'great' and , ', meaning 'lizard') is an extinct genus of large carnivorous theropod dinosaurs of the Middle Jurassic Epoch (Bathonian stage, 166 ...

'' in 1824.

Buckland followed the Gap Theory in interpreting the biblical account of ''Genesis'' as two widely separated episodes of creation. It had emerged as a way to reconcile the scriptural account with discoveries in geology suggesting the earth was very old. Early in his career Buckland believed he had found evidence of the biblical flood, but later saw that the glaciation theory of Louis Agassiz

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz ( ; ) FRS (For) FRSE (May 28, 1807 – December 14, 1873) was a Swiss-born American biologist and geologist who is recognized as a scholar of Earth's natural history.

Spending his early life in Switzerland, he recei ...

gave a better explanation, and played a significant role in promoting it.

Buckland served as Dean of Westminster from 1845 until his death 1856.

Early life

Axminster

Axminster is a market town and civil parishes in England, civil parish on the eastern border of the county of Devon in England. It is from the county town of Exeter. The town is built on a hill overlooking the River Axe, Devon, River Axe which ...

in DevonChisholm, 1911 and, as a child, would accompany his father, the Rector of Templeton and Trusham, on his walks where interest in road improvements led to collecting fossil shells, including ammonite

Ammonoids are extinct, (typically) coiled-shelled cephalopods comprising the subclass Ammonoidea. They are more closely related to living octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish (which comprise the clade Coleoidea) than they are to nautiluses (family N ...

s, from the Early Jurassic

The Early Jurassic Epoch (geology), Epoch (in chronostratigraphy corresponding to the Lower Jurassic series (stratigraphy), Series) is the earliest of three epochs of the Jurassic Period. The Early Jurassic starts immediately after the Triassic� ...

Lias rocks exposed in local quarries.

He was educated first at Blundell's School

Blundell's School is an Private schools in the United Kingdom, independent co-educational boarding school, boarding and Day school, day school in the English Public School (United Kingdom), public school tradition, located in Tiverton, Devon, T ...

, Tiverton, Devon, and then at Winchester College

Winchester College is an English Public school (United Kingdom), public school (a long-established fee-charging boarding school for pupils aged 13–18) with some provision for day school, day attendees, in Winchester, Hampshire, England. It wa ...

, from where he won a scholarship to Corpus Christi College, Oxford

Corpus Christi College (formally, Corpus Christi College in the University of Oxford; informally abbreviated as Corpus or CCC) is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1517 by Richard Fo ...

, matriculating in 1801 and graduating BA in 1805. He also attended lectures of John Kidd on mineralogy and chemistry, developed an interest in geology

Geology (). is a branch of natural science concerned with the Earth and other astronomical objects, the rocks of which they are composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Earth ...

, and carried out field research on strata

In geology and related fields, a stratum (: strata) is a layer of Rock (geology), rock or sediment characterized by certain Lithology, lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separated by v ...

during his vacations. He went on to obtain his MA degree in 1808, became a Fellow

A fellow is a title and form of address for distinguished, learned, or skilled individuals in academia, medicine, research, and industry. The exact meaning of the term differs in each field. In learned society, learned or professional society, p ...

of Corpus Christi in 1809, and was ordained as a priest. He continued to make frequent geological excursions, on horseback, to various parts of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales.

In 1813, Buckland was appointed Reader in mineralogy, in succession to John Kidd, giving lively and popular lectures with increasing emphasis on geology and palaeontology

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geo ...

. As an unofficial curator

A curator (from , meaning 'to take care') is a manager or overseer. When working with cultural organizations, a curator is typically a "collections curator" or an "exhibitions curator", and has multifaceted tasks dependent on the particular ins ...

of the Ashmolean Museum

The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology () on Beaumont Street in Oxford, England, is Britain's first public museum. Its first building was erected in 1678–1683 to house the cabinet of curiosities that Elias Ashmole gave to the University ...

, he built up collections, touring Europe and coming into contact with scholars including Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

.

Career, work and discoveries

Rejection of flood geology and Kirkdale Cave

In 1818, Buckland was elected a fellow of theRoyal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

. That year he persuaded the Prince Regent to endow an additional Readership, this time in Geology and he became the first holder of the new appointment, delivering his inaugural address on 15 May 1819. This was published in 1820 as ''Vindiciæ Geologiæ; or the Connexion of Geology with Religion explained'', both justifying the new science of geology and reconciling geological evidence with the biblical

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) biblical languages ...

accounts of creation and Noah's Flood

The Genesis flood narrative (chapters 6–9 of the Book of Genesis) is a Hebrew flood myth. It tells of God's decision to return the universe to its pre- creation state of watery chaos and remake it through the microcosm of Noah's ark.

The B ...

.

At a time when others were coming under the opposing influence of James Hutton

James Hutton (; 3 June Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. 1726 – 26 March 1797) was a Scottish geologist, Agricultural science, agriculturalist, chemist, chemical manufacturer, Natural history, naturalist and physician. Often referred to a ...

's theory of uniformitarianism

Uniformitarianism, also known as the Doctrine of Uniformity or the Uniformitarian Principle, is the assumption that the same natural laws and processes that operate in our present-day scientific observations have always operated in the universe in ...

, Buckland developed a new hypothesis that the word "beginning" in Genesis meant an undefined period between the origin of the earth and the creation of its current inhabitants, during which a long series of extinctions and successive creations of new kinds of plants and animals had occurred. Thus, his catastrophism

In geology, catastrophism is the theory that the Earth has largely been shaped by sudden, short-lived, violent events, possibly worldwide in scope.

This contrasts with uniformitarianism (sometimes called gradualism), according to which slow inc ...

theory incorporated a version of Old Earth creationism

Old Earth Creationism (OEC) is an umbrella of theological views encompassing certain varieties of creationism which may or can include day-age creationism, gap creationism, progressive creationism, and sometimes theistic evolution.

Broadly speak ...

or Gap creationism

Gap creationism (also known as ruin-restoration creationism, restoration creationism, or "the Gap Theory") is a form of creationism that posits that the six-'' yom'' creation period, as described in the Book of Genesis, involved six literal 24-h ...

. Buckland believed in a global deluge during the time of Noah but was not a supporter of flood geology

Flood geology (also creation geology or diluvial geology) is a Pseudoscience, pseudoscientific attempt to interpret and reconcile :geology, geological features of the Earth in accordance with a literal belief in the Genesis flood narrative, th ...

as he believed that only a small amount of the strata could have been formed in the single year occupied by the deluge.

From his investigations of fossil bones at Kirkdale Cave, in Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ) is an area of Northern England which was History of Yorkshire, historically a county. Despite no longer being used for administration, Yorkshire retains a strong regional identity. The county was named after its county town, the ...

, he concluded that the cave had actually been inhabited by hyaenas in antediluvian times, and that the fossils were the remains of these hyaenas and the animals they had eaten, rather than being remains of animals that had perished in the Flood and then carried from the tropics by the surging waters, as he and others had at first thought. In 1822 he wrote:

It must already appear probable, from the facts above described, particularly from the comminuted state and apparently gnawed condition of the bones, that the cave in Kirkdale was, during a long succession of years, inhabited as a den of hyaenas, and that they dragged into its recesses the other animal bodies whose remains are found mixed indiscriminately with their own: this conjecture is rendered almost certain by the discovery I made, of many small balls of the solid calcareous excrement of an animal that had fed on bones... It was at first sight recognised by the keeper of the Menagerie at Exeter Change, as resembling, in both form and appearance, the faeces of the spotted or cape hyaena, which he stated to be greedy of bones beyond all other beasts in his care.While criticised by some, Buckland's analysis of Kirkland Cave and other bone caves was widely seen as a model for how careful analysis could be used to reconstruct the Earth's past, and the Royal Society awarded Buckland the

Copley Medal

The Copley Medal is the most prestigious award of the Royal Society of the United Kingdom, conferred "for sustained, outstanding achievements in any field of science". The award alternates between the physical sciences or mathematics and the bio ...

in 1822 for his paper on Kirkdale Cave.Rudwick, Martin ''Bursting The Limits of Time: The Reconstruction of Geohistory in the Age of Revolution'' (2005) pp. 622–638, 631 At the presentation the society's president, Humphry Davy

Sir Humphry Davy, 1st Baronet (17 December 177829 May 1829) was a British chemist and inventor who invented the Davy lamp and a very early form of arc lamp. He is also remembered for isolating, by using electricity, several Chemical element, e ...

, said:

by these inquiries, a distinct epoch has, as it were, been established in the history of the revolutions of our globe: a point fixed from which our researches may be pursued through the immensity of ages, and the records of animate nature, as it were, carried back to the time of the creation.While Buckland's analysis convinced him that the bones found in Kirkdale Cave had not been washed into the cave by a global flood, he still believed the thin layer of mud that covered the remains of the hyaena den had been deposited in the subsequent 'Universal Deluge'. He developed these ideas into his great scientific work ''Reliquiæ Diluvianæ, or, Observations on the Organic Remains attesting the Action of a Universal Deluge'' which was published in 1823 and became a best seller. However, over the next decade as geology continued to progress Buckland changed his mind. In his famous Bridgewater Treatise, published in 1836, he acknowledged that the biblical account of Noah's flood could not be confirmed using geological evidence. By 1840 he was very actively promoting the view that what had been interpreted as evidence of the 'Universal Deluge' two decades earlier, and subsequently of deep submergence by a new generation of geologists such as Charles Lyell, was in fact evidence of a major glaciation.

''Megalosaurus''

He continued to live in Corpus Christi College and, in 1824, he became president of the Geological Society of London. Here he announced the discovery, at Stonesfield, of fossil bones of a giant

He continued to live in Corpus Christi College and, in 1824, he became president of the Geological Society of London. Here he announced the discovery, at Stonesfield, of fossil bones of a giant reptile

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology), orders: Testudines, Crocodilia, Squamata, and Rhynchocepha ...

which he named ''Megalosaurus

''Megalosaurus'' (meaning "great lizard", from Ancient Greek, Greek , ', meaning 'big', 'tall' or 'great' and , ', meaning 'lizard') is an extinct genus of large carnivorous theropod dinosaurs of the Middle Jurassic Epoch (Bathonian stage, 166 ...

'' ('great lizard') and wrote the first full account of what would later be called a dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

.

In 1825, Buckland was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (The Academy) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and other ...

. That year he resigned his college fellowship: he planned to take up the living of Stoke Charity in Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Berkshire to the north, Surrey and West Sussex to the east, the Isle of Wight across the Solent to the south, ...

but, before he could take up the appointment, he was made a Canon

Canon or Canons may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Canon (fiction), the material accepted as officially written by an author or an ascribed author

* Literary canon, an accepted body of works considered as high culture

** Western canon, th ...

of Christ Church, a rich reward for academic distinction without serious administrative responsibilities.

Marriage

In December 1825 he married Mary Morland of Abingdon, Oxfordshire, an accomplished illustrator and collector offossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

s. Their honeymoon

A honeymoon is a vacation taken by newlyweds after their wedding to celebrate their marriage. Today, honeymoons are often celebrated in destinations considered exotic or romantic. In a similar context, it may also refer to the phase in a couple ...

was a year touring Europe, with visits to famous geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the structure, composition, and History of Earth, history of Earth. Geologists incorporate techniques from physics, chemistry, biology, mathematics, and geography to perform research in the Field research, ...

s and geological sites. She continued to assist him in his work, as well as having nine children, five of whom survived to adulthood. His son Frank Buckland became a well known practical naturalist, author, and Inspector of Salmon Fisheries.

On one occasion, Mary helped him decipher footmarks found in a slab of sandstone by covering the kitchen table with paste, while he fetched their pet tortoise

Tortoises ( ) are reptiles of the family Testudinidae of the order Testudines (Latin for "tortoise"). Like other turtles, tortoises have a shell to protect from predation and other threats. The shell in tortoises is generally hard, and like o ...

and confirmed his intuition, that tortoise footprints matched the fossil marks. His daughter, author Elizabeth Oke Buckland Gordon, wrote a biography

A biography, or simply bio, is a detailed description of a person's life. It involves more than just basic facts like education, work, relationships, and death; it portrays a person's experience of these life events. Unlike a profile or curri ...

of her father that included appendices of positions held by Buckland, his membership in professional societies, and an index of his publications.

The Red Lady of Paviland

On 18 January 1823 Buckland walked into Paviland Cave in south Wales, where he discovered a skeleton which he named the Red Lady of Paviland, as he at first supposed it to be the remains of a local prostitute. Although Buckland found the skeleton in Paviland Cave in the same strata as the bones of extinct mammals (includingmammoth

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus.'' They lived from the late Miocene epoch (from around 6.2 million years ago) into the Holocene until about 4,000 years ago, with mammoth species at various times inhabi ...

), Buckland shared the view of Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

that no humans had coexisted with any extinct animals, and he attributed the skeleton's presence there to a grave having been dug in historical times, possibly by the same people who had constructed some nearby pre-Roman fortifications, into the older layers.

Carbon-data tests have since dated the skeleton

A skeleton is the structural frame that supports the body of most animals. There are several types of skeletons, including the exoskeleton, which is a rigid outer shell that holds up an organism's shape; the endoskeleton, a rigid internal fra ...

, now known to be male as from circa 33,000 years before present (BP).

It is the oldest anatomically modern human

Anatomy () is the branch of morphology concerned with the study of the internal structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science ...

found in the United Kingdom.

Coprolites and the Liassic food chain

The fossil hunter

The fossil hunter Mary Anning

Mary Anning (21 May 1799 – 9 March 1847) was an English fossil collector, fossil trade, dealer, and palaeontologist. She became known internationally for her discoveries in Jurassic marine fossil beds in the cliffs along the English Cha ...

noticed that stony objects known as "bezoar

A bezoar stone ( ) is a mass often found trapped in the gastrointestinal system, though it can occur in other locations. A pseudobezoar is an indigestible object introduced intentionally into the digestive system.

There are several varieties o ...

stones" were often found in the abdominal region of ichthyosaur

Ichthyosauria is an order of large extinct marine reptiles sometimes referred to as "ichthyosaurs", although the term is also used for wider clades in which the order resides.

Ichthyosaurians thrived during much of the Mesozoic era; based on fo ...

skeletons found in the Lias formation at Lyme Regis

Lyme Regis ( ) is a town in west Dorset, England, west of Dorchester, Dorset, Dorchester and east of Exeter. Sometimes dubbed the "Pearl of Dorset", it lies by the English Channel at the Dorset–Devon border. It has noted fossils in cliffs and ...

. She also noted that if such stones were broken open they often contained fossilised fish bones and scales, and sometimes bones from small ichthyosaur

Ichthyosauria is an order of large extinct marine reptiles sometimes referred to as "ichthyosaurs", although the term is also used for wider clades in which the order resides.

Ichthyosaurians thrived during much of the Mesozoic era; based on fo ...

s. These observations by Anning led Buckland to propose in 1829 that the stones were fossilised faeces. He coined the name coprolite

A coprolite (also known as a coprolith) is fossilized feces. Coprolites are classified as trace fossils as opposed to body fossils, as they give evidence for the animal's behaviour (in this case, diet) rather than morphology. The name ...

for them; the name came to be the general name for all fossilised faeces.

Buckland also concluded that the spiral markings on the fossils indicated that ichthyosaurs had spiral ridges in their intestines similar to those of modern shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch cartilaginous fish characterized by a ribless endoskeleton, dermal denticles, five to seven gill slits on each side, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the ...

s, and that some of these coprolite

A coprolite (also known as a coprolith) is fossilized feces. Coprolites are classified as trace fossils as opposed to body fossils, as they give evidence for the animal's behaviour (in this case, diet) rather than morphology. The name ...

s were black because the ichthyosaur had ingested ink sacs from belemnite

Belemnitida (or belemnites) is an extinct order (biology), order of squid-like cephalopods that existed from the Late Triassic to Late Cretaceous (And possibly the Eocene). Unlike squid, belemnites had an internal skeleton that made up the cone ...

s. He wrote a vivid description of the Liassic food chain based on these observations, which would inspire Henry De la Beche

Sir Henry Thomas De la Beche KCB, FRS (10 February 179613 April 1855) was an English geologist and palaeontologist, the first director of the Geological Survey of Great Britain, who helped pioneer early geological survey methods. He was the ...

to paint '' Duria Antiquior'', the first pictorial representation of a scene from the distant past. After De le Beche had a lithographic print made based on his original watercolour

Watercolor (American English) or watercolour ( Commonwealth English; see spelling differences), also ''aquarelle'' (; from Italian diminutive of Latin 'water'), is a painting method"Watercolor may be as old as art itself, going back to the ...

, Buckland kept a supply of the prints on hand to circulate at his lectures. He also discussed other similar objects found in other formations, including the fossilised hyena dung he had found in Kirkdale Cave. He concluded:

In all these various formations our Coprolites form records of warfare, waged by successive generations of inhabitants of our planet on one another: the imperishable phosphate of lime, derived from their digested skeletons, has become embalmed in the substance and foundations of the everlasting hills; and the general law of Nature which bids all to eat and be eaten in their turn, is shown to have been co-extensive with animal existence on our globe; theBuckland had been helping and encouragingCarnivora Carnivora ( ) is an order of placental mammals specialized primarily in eating flesh, whose members are formally referred to as carnivorans. The order Carnivora is the sixth largest order of mammals, comprising at least 279 species. Carnivor ...in each period of the world's history fulfilling their destined office, – to check excess in the progress of life, and maintain the balance of creation.

Roderick Murchison

Sir Roderick Impey Murchison, 1st Baronet (19 February 1792 – 22 October 1871) was a Scottish geologist who served as director-general of the British Geological Survey from 1855 until his death in 1871. He is noted for investigating and desc ...

for some years, and in 1831 was able to suggest a good starting point in South Wales

South Wales ( ) is a Regions of Wales, loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the Historic counties of Wales, historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire ( ...

for Murchison's researches into the rocks beneath the secondary strata associated with the age of reptiles. Murchison would later name these older strata, characterised by marine invertebrate

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordata, chordate s ...

fossils, as Silurian

The Silurian ( ) is a geologic period and system spanning 23.5 million years from the end of the Ordovician Period, at million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Devonian Period, Mya. The Silurian is the third and shortest period of t ...

, after a tribe that had lived in that area centuries earlier. In 1832 Buckland presided over the second meeting of the British Association

The British Science Association (BSA) is a charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA). The current Chief ...

, which was then held at Oxford.

Bridgewater Treatise

Buckland was commissioned to contribute one of the set of eight ''

Buckland was commissioned to contribute one of the set of eight ''Bridgewater Treatises

The Bridgewater Treatises (1833–36) are a series of eight works that were written by leading scientific figures appointed by the President of the Royal Society in fulfilment of a bequest of £8000, made by Francis Henry Egerton, 8th Earl of Bridg ...

'', "On the Power, Wisdom and Goodness of God, as manifested in the Creation". This took him almost five years' work and was published in 1836 with the title ''Geology and Mineralogy considered with reference to Natural Theology''. His volume included a detailed compendium of his theories of day-age, gap theory and a form of progressive creationism

Progressive creationism is the religious belief that God created new forms of life gradually over a period of hundreds of millions of years. As a form of old Earth creationism, it accepts mainstream geological and cosmological estimates for the ...

where faunal succession revealed by the fossil record was explained by a series of successive divine

Divinity (from Latin ) refers to the quality, presence, or nature of that which is divine—a term that, before the rise of monotheism, evoked a broad and dynamic field of sacred power. In the ancient world, divinity was not limited to a singl ...

creations that prepared the earth for humans. In the introduction he expressed the argument from design by asserting that the families and phyla

Phyla, the plural of ''phylum'', may refer to:

* Phylum, a biological taxon between Kingdom and Class

* by analogy, in linguistics, a large division of possibly related languages, or a major language family which is not subordinate to another

Phy ...

of biology were "clusters of contrivance":

The myriads of petrified Remains which are disclosed by the researches of Geology all tend to prove that our Planet has been occupied in times preceding the Creation of the Human Race, by extinct species of Animals and Vegetables, made up, like living Organic Bodies, of 'Clusters of Contrivances,' which demonstrate the exercise of stupendous Intelligence and Power. They further show that these extinct forms of Organic Life were so closely allied, by Unity in the principles of their construction, to Classes, Orders, and Families, which make up the existing Animal and Vegetable Kingdoms, that they not only afford an argument of surpassing force, against the doctrines of the Atheist and Polytheist; but supply a chain of connected evidence, amounting to demonstration, of the continuous Being, and of many of the highest Attributes of the One Living and True God.Following

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

's return from the ''Beagle'' voyage, Buckland discussed with him the Galapagos land iguanas and Marine iguanas. He subsequently recommended Darwin's paper on the role of earthworm

An earthworm is a soil-dwelling terrestrial invertebrate that belongs to the phylum Annelida. The term is the common name for the largest members of the class (or subclass, depending on the author) Oligochaeta. In classical systems, they we ...

s in soil formation

Soil formation, also known as pedogenesis, is the process of soil genesis as regulated by the effects of place, environment, and history. Biogeochemical processes act to both create and destroy order ( anisotropy) within soils. These alteration ...

for publication, praising it as "a new & important theory to explain Phenomena of universal occurrence on the surface of the Earth—in fact a new Geological Power", while rightly rejecting Darwin's suggestion that chalkland could have been formed in a similar way.

Glaciation theory

By this time Buckland was a prominent and influential scientific celebrity and a friend of theTory

A Tory () is an individual who supports a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalist conservatism which upholds the established social order as it has evolved through the history of Great Britain. The To ...

prime minister, Sir Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet (5 February 1788 – 2 July 1850), was a British Conservative statesman who twice was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1834–1835, 1841–1846), and simultaneously was Chancellor of the Exchequer (1834–183 ...

. In co-operation with Adam Sedgwick

Adam Sedgwick FRS (; 22 March 1785 – 27 January 1873) was a British geologist and Anglican priest, one of the founders of modern geology. He proposed the Cambrian and Devonian period of the geological timescale. Based on work which he did ...

and Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known today for his association with Charles ...

, he prepared the report leading to the establishment of the Geological Survey of Great Britain.

Having become interested in the theory of Louis Agassiz

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz ( ; ) FRS (For) FRSE (May 28, 1807 – December 14, 1873) was a Swiss-born American biologist and geologist who is recognized as a scholar of Earth's natural history.

Spending his early life in Switzerland, he recei ...

, that polished and striated rocks as well as transported material, had been caused by ancient glacier

A glacier (; or ) is a persistent body of dense ice, a form of rock, that is constantly moving downhill under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires ...

s, he travelled to Switzerland, in 1838, to meet Agassiz and see for himself. He was convinced and was reminded of what he had seen in Scotland, Wales and northern England but had previously attributed to the Flood. When Agassiz came to Britain for the Glasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

meeting of the British Association, in 1840, they went on an extended tour of Scotland and found evidence there of former glaciation. In that year Buckland had become president of the Geological Society again and, despite their hostile reaction to his presentation of the theory, he was now satisfied that glaciation had been the origin of much of the surface deposits covering Britain.

In 1845 he was appointed by Sir Robert Peel to the vacant Deanery of Westminster (he succeeded Samuel Wilberforce

Samuel Wilberforce, Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (7 September 1805 – 19 July 1873) was an English bishop in the Church of England, and the third son of William Wilberforce. Known as "Soapy Sam", Wilberforce was one of the greatest public sp ...

). Soon after, he was inducted to the living of Islip, near Oxford, a preferment attached to the deanery. As Dean and head of Chapter, Buckland was involved in repair and maintenance of Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

and in preaching suitable sermons to the rural population of Islip, while continuing to lecture on geology at Oxford. In 1847, he was appointed a trustee in the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

and, in 1848, he was awarded the Wollaston Medal by the Geological Society of London.

Illness and death

Around the end of 1850, William Buckland contracted a disorder of the neck and brain, and died of it in 1856. Frank Buckland reported that an autopsy showed "the portion of the base of the skull upon which the brain rested, together with the two upper vertebrae of the neck, to be in an advanced state of caries, or decay. The irritation...was quite sufficient cause to give rise to all symptoms." Frank Buckland attributed the cause of death of both his parents to a severe accident years earlier. The plot for William's grave had been reserved, but when the gravedigger set to work, it was found that an outcrop of solidJurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 143.1 Mya. ...

limestone lay just below ground level and explosives had to be used for excavation. This may have been a last jest by the noted geologist, reminiscent of Richard Whately's ''Elegy intended for Professor Buckland'' written in 1820:

Known eccentricities

Buckland preferred to do his field palaeontology and geological work wearing anacademic gown

Academic dress is a traditional form of clothing for academic settings, mainly tertiary (and sometimes secondary) education, worn mainly by those who have obtained a university degree (or similar), or hold a status that entitles them to ass ...

. His lectures were notable for their dramatic delivery."Learning More... William Buckland" Oxford University Museum /ref> When he lectured indoors he would bring his presentations to life by imitating the movements of the dinosaurs under discussion. Buckland's passion for scientific observation and experiment extended to his home, where he had a table inlaid with

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

coprolite

A coprolite (also known as a coprolith) is fossilized feces. Coprolites are classified as trace fossils as opposed to body fossils, as they give evidence for the animal's behaviour (in this case, diet) rather than morphology. The name ...

s. The original table top is exhibited at the Lyme Regis Museum.Harry Hogger "19th century table created out of fossil poo recreated for descendants of original owner" ''Bridport News" 30 July 2013''/ref> Not only was William Buckland's home filled with specimens – animal as well as mineral, live as well as dead – but he claimed to have eaten his way through the animal kingdom. Reportedly according to an anecdote recounted by Augustus Hare, the most distasteful animals Buckland consumed were in his opinion mole and bluebottle fly. Ostrich, hedgehogs, mice, frogs and snails, were among other animals reportedly served to guests. Buckland was followed in this hobby by his son Frank. One story recounted by Peter Lund Simmonds in 1859 reports that Buckland served soup to his guests before claiming that it was an alligator that he had dissected earlier that day, to the guests significant discomfort. When asked if he had really served an alligator, he reportedly responded "as good a calf's head as ever wore a coronet". According to one story, Buckland consumed, perhaps unintentionally, a portion of the mummified heart of the French King

Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

during a dinner at Nuneham House

Nuneham House is an eighteenth century villa in the Palladian architecture, Palladian style, set in parkland at Nuneham Courtenay in Oxfordshire, England. It is currently owned by Oxford University and is used as a retreat centre by the Brahma K ...

, though the veracity of this particular story has been questioned. The Louis XIV heart story goes back at least as far as an 1863 book by Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (né Hathorne; July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, from a family long associat ...

''.''

Charles Darwin criticised Buckland for his behaviour in his autobiography, saying that "Buckland, who though very good-humoured and good-natured, seemed to me a vulgar and almost coarse man. He was incited more by a craving for notoriety, which sometimes made him act like a buffoon, than by a love of science."

Legacy

Dorsum Buckland, a wrinkle ridge on theMoon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It Orbit of the Moon, orbits around Earth at Lunar distance, an average distance of (; about 30 times Earth diameter, Earth's diameter). The Moon rotation, rotates, with a rotation period (lunar ...

, is named after him. Buckland Island (known today as Ani-Jima), in the Bonin Islands

The Bonin Islands, also known as the , is a list of islands of Japan, Japanese archipelago of over 30 subtropical and Island#Tropical islands, tropical islands located around SSE of Tokyo and northwest of Guam. The group as a whole has a total ...

(Ogasawara-Jima), was named after him by Captain Beechey on 9 June 1827. In 1846, William Buckland was rector of St. Nicholas in Islip and is commemorated on a plaque in the south aisle of the church and the "East Window" was dedicated to the memory of Buckland and his wife in 1861. A plaque is dedicated to him near his summer home by the Old Rectory, The Walk, Islip (10 August 2008). There is also a bust by Henry Weekes in the south aisle at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

.

In 1972, botanist Heikki Roivainen circumscribed '' Bucklandiella'', a genus of moss in the family Grimmiaceae, which was named in his honour. Buckland Peaks in New Zealand's Paparoa Range was named after him.

The Iñupiat village of Buckland () in Alaska's Northwest Arctic Borough

Northwest Arctic Borough is a List of boroughs and census areas in Alaska, borough located in the U.S. state of Alaska. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 7,793, up from 7,523 in 2010. The borough seat is Kotze ...

takes its English name from William Buckland, being named by Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

officer Frederick William Beechey in 1826.

See also

* History of palaeontologyNotes

References

* * ** * * * * ;Attribution *Further reading

* *External links

Buckland at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History

(London : J. Murray, 1894) – digital facsimile available from

Linda Hall Library

The Linda Hall Library is a privately endowed American library of science, engineering and technology located in Kansas City, Missouri, on the grounds of a urban arboretum. It claims to be the "largest independently funded public library of sc ...

* William Buckland (1823''Reliquiæ Diluvianæ''

(English) – digital facsimile available from

Linda Hall Library

The Linda Hall Library is a privately endowed American library of science, engineering and technology located in Kansas City, Missouri, on the grounds of a urban arboretum. It claims to be the "largest independently funded public library of sc ...

. A number of high-resolution images of the maps and other illustrations from this book are availablhere

{{DEFAULTSORT:Buckland, William 1784 births 1856 deaths Presidents of the Geological Society of London People from Axminster Catastrophism Christian Old Earth creationists British Christian creationists Doctors of Divinity English Anglicans People educated at Blundell's School Alumni of Corpus Christi College, Oxford English geologists English palaeontologists Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Fellows of the Royal Society Fellows of Christ Church, Oxford Deans of Westminster Recipients of the Copley Medal Wollaston Medal winners Fellows of the Geological Society of London 19th-century English scientists 18th-century English people 19th-century English people People educated at Winchester College Enlightenment scientists Parson-naturalists Writers about religion and science Authors of the Bridgewater Treatises People associated with the Ashmolean Museum