Vladimir Konstantinovich Bukovsky (; 30 December 1942 – 27 October 2019) was a Soviet and Russian

human rights activist and writer. From the late 1950s to the mid-1970s, he was a prominent figure in the

Soviet dissident movement, well known at home and abroad. He spent a total of twelve years in the

psychiatric prison-hospitals,

labour camps, and

prison

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol, penitentiary, detention center, correction center, correctional facility, or remand center, is a facility where Prisoner, people are Imprisonment, imprisoned under the authority of the State (polity), state ...

s of the Soviet Union during

Brezhnev's rule.

After being expelled from the Soviet Union in late 1976, Bukovsky remained in

vocal opposition to the

Soviet system and the shortcomings of its

successor regimes in Russia. An activist, a writer,

[ Jacket] and a

neurophysiologist,

[.] he is celebrated for his part in the campaign to expose and halt the

political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union

There was systematic political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union, based on the interpretation of political opposition or dissent as a psychiatric problem. It was called "psychopathological mechanisms" of dissent.

During the leader ...

.

A member of the international advisory council of the

Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, a director of the Gratitude Fund (set up in 1998 to commemorate and support former dissidents),

and a member of the International Council of the New York City-based

Human Rights Foundation, Bukovsky was a Senior Fellow of the

Cato Institute

The Cato Institute is an American libertarian think tank headquartered in Washington, D.C. It was founded in 1977 by Ed Crane, Murray Rothbard, and Charles Koch, chairman of the board and chief executive officer of Koch Industries.Koch ...

in Washington, D.C.

["Vladimir Bukovsky"](_blank)

Cato Institute website

In 2001, Vladimir Bukovsky received the

Truman-Reagan Medal of Freedom, awarded annually since 1993 by the

Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation.

Early life

Vladimir Bukovsky was born to Russian parents in the town of

Belebey in the

Bashkir Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic

The Bashkir Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, also historically known as Soviet Bashkiria or simply Bashkiria, was an Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, autonomous republic of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR. ...

(today the Republic of

Bashkortostan

Bashkortostan, officially the Republic of Bashkortostan, sometimes also called Bashkiria, is a republic of Russia between the Volga river and the Ural Mountains in Eastern Europe. The republic borders Perm Krai to the north, Sverdlovsk Oblast ...

in the Russian Federation), to which his family was

evacuated during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. After the war he and his parents returned to Moscow where his father Konstantin (1908–1976) was a well-known Soviet journalist. During his last year at school Vladimir was expelled for

creating and editing an unauthorised magazine. To meet the requirements to apply for a university place he completed his secondary education at evening classes. Bukovsky was enrolled at biology department of

Moscow State University

Moscow State University (MSU), officially M. V. Lomonosov Moscow State University,. is a public university, public research university in Moscow, Russia. The university includes 15 research institutes, 43 faculties, more than 300 departments, a ...

, but he was expelled at age 19 for criticizing Soviet state organizations, such as

Komsomol.

Soviet era

Rallies

Mayakovsky Square

In September 1960, Bukovsky entered

Moscow University

Moscow State University (MSU), officially M. V. Lomonosov Moscow State University,. is a public research university in Moscow, Russia. The university includes 15 research institutes, 43 faculties, more than 300 departments, and six branches. Al ...

to study biology. There he and some friends decided to revive the informal

Mayakovsky Square poetry readings which began after a statue to the poet was unveiled in central Moscow in 1958. They made contact with earlier participants of the readings such as

Vladimir Osipov, the editor of ''Boomerang'' (1960), and

Yuri Galanskov who issued the ''

Phoenix'' (1961), two examples of literary

samizdat.

It was then that the 19-year-old Bukovsky wrote his critical notes on the Communist Youth League or

Komsomol. Later, this text was given the title "Theses on the Collapse of the Komsomol" by the

KGB

The Committee for State Security (, ), abbreviated as KGB (, ; ) was the main security agency of the Soviet Union from 1954 to 1991. It was the direct successor of preceding Soviet secret police agencies including the Cheka, Joint State Polit ...

. Bukovsky portrayed the

USSR

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

as an "illegal society" facing an acute ideological crisis. The Komsomol was "moribund", he asserted, having lost both moral and spiritual authority, and he called for its democratisation. This text, and his other activities, brought Bukovsky to the attention of the authorities. He was interrogated twice before being thrown out of the university in autumn 1961.

Bukovsky was arrested on 1 June 1963. He was later convicted, in absentia, by reason of his "insanity", under Article 70.1 ("

Anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda") of the

RSFSR

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

Criminal Code

A criminal code or penal code is a document that compiles all, or a significant amount of, a particular jurisdiction's criminal law. Typically a criminal code will contain offences that are recognised in the jurisdiction, penalties that might ...

. The official charge was the making and possession of photocopies of anti-Soviet literature, namely two copies of the banned work ''

The New Class'' by

Milovan Djilas.

Bukovsky was examined by Soviet psychiatrists, declared to be mentally ill ("

schizophrenia

Schizophrenia () is a mental disorder characterized variously by hallucinations (typically, Auditory hallucination#Schizophrenia, hearing voices), delusions, thought disorder, disorganized thinking and behavior, and Reduced affect display, f ...

"), and sent for treatment at the Special Psychiatric Hospital in Leningrad where he remained for almost two years, until February 1965.

[Victims of political terror in the USSR.](_blank)

Database of the Memorial Society. It was there he became acquainted with General

Petro Grigorenko, a fellow inmate.

The glasnost rally, 5 December 1965

In December 1965, Bukovsky helped prepare a demonstration on

Pushkin Square in central Moscow to protest against the

trial

In law, a trial is a coming together of parties to a dispute, to present information (in the form of evidence) in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to adjudicate claims or disputes. One form of tribunal is a court. The tribunal, w ...

of the writers

Andrei Sinyavsky

Andrei Donatovich Sinyavsky (; 8 October 1925 – 25 February 1997) was a Russian writer and Soviet dissident known as a defendant in the Sinyavsky–Daniel trial of 1965.

Sinyavsky was a literary critic for ''Novy Mir'' and wrote works critic ...

and

Yuli Daniel. He circulated the "Civic Appeal" by mathematician and poet

Alexander Esenin-Volpin, which called on the authorities to obey the Soviet laws requiring

glasnost

''Glasnost'' ( ; , ) is a concept relating to openness and transparency. It has several general and specific meanings, including a policy of maximum openness in the activities of state institutions and freedom of information and the inadmissi ...

in the judicial process, e.g. the admission of the public and the media to any trial.

The demonstration on 5 December 1965 (Constitution Day) became known as the

Glasnost Meeting or rally, and marked the beginning of the openly active Soviet civil rights movement.

Bukovsky himself was unable to attend. Three days earlier he was arrested, charged with distributing the appeal, and kept in various

psikhushkas,

[ among them Hospital No 13 at Lublino, Stolbovaya and the Serbsky Institute, until July 1966.

]

The right to demonstrate, 1967

On 22 January 1967, Bukovsky, Vadim Delaunay, Yevgeny Kushev and Victor Khaustov held another demonstration on Pushkin Square. They were protesting against the recent arrests of Alexander Ginzburg

Alexander "Alik" Ilyich Ginzburg ( rus, Алекса́ндр Ильи́ч Ги́нзбург, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr ɨˈlʲjidʑ ˈɡʲinzbʊrk, a=Alyeksandr Il'yich Ginzburg.ru.vorb.oga; 21 November 1936 – 19 July 2002), was a Russian journalist ...

, Yuri Galanskov, Alexei Dobrovolsky and Vera Lashkova (finally prosecuted in January 1968 in the Trial of the FourPavel Litvinov

Pavel Mikhailovich Litvinov (; born 6 July 1940) is a Russian-born U.S. physicist, writer, teacher, Human rights movement in the Soviet Union, human rights activist and former Soviet dissidents, Soviet-era dissident.

Biography

The grandson of Iv ...

.Voronezh

Voronezh ( ; , ) is a city and the administrative centre of Voronezh Oblast in southwestern Russia straddling the Voronezh River, located from where it flows into the Don River. The city sits on the Southeastern Railway, which connects wes ...

Region to serve his sentence. He was released in January 1970.

The campaign against the abuse of psychiatry

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Soviet authorities began the widespread use of psychiatric treatment as a form of punishment and deterrence for the independent-minded. This involved unlimited detention in a psikhushka, as such places were popularly known, which might be conventional psychiatric hospitals or psychiatric prison-hospitals set up (e.g. the Leningrad Special Psychiatric Hospital) as part of an existing penal institution. Healthy individuals were held among mentally ill and often dangerous patients; they were forced to take various psychotropic drugs; they might also be incarcerated in prison-type institutions under overall control of the KGB.The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' (London) and later in the '' British Journal of Psychiatry''[ Bukovsky was arrested on 29 March and held in custody for nine months before being put on trial in January 1972.]World Psychiatric Association

The World Psychiatric Association (WPA) is an international Umbrella organization, umbrella organisation of psychiatric societies.

Objectives and goals

Originally created to produce world psychiatric congresses, it has evolved to hold regional ...

finally condemned Soviet practices at its Sixth World Congress in 1977 and set up a review committee to monitor misuse.

Final arrest (1971) and imprisonment

Following the release of the documents, Bukovsky was denounced in ''Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, 'Truth') is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most in ...

'' as a "malicious hooligan, engaged in anti-Soviet activities" and arrested on 29 March 1971.[For reactions in the West and the Soviet Union to the sentence se]

CCE 24.1 (5 March 1972), "The case of Vladimir Bukovsky".

For a KGB

The Committee for State Security (, ), abbreviated as KGB (, ; ) was the main security agency of the Soviet Union from 1954 to 1991. It was the direct successor of preceding Soviet secret police agencies including the Cheka, Joint State Polit ...

profile of Bukovsky, dated 18 May 1972, see:

While in prison Bukovsky and his fellow inmate, the psychiatrist Semyon Gluzman, wrote a brief 20-page ''Manual on Psychiatry for Dissidents'', which was widely published abroad, in Russian (1975) and in many other languages, including English, French, Italian, German, and Danish. It instructed potential victims of political psychiatry how to behave during interrogation to avoid being diagnosed as mentally ill.

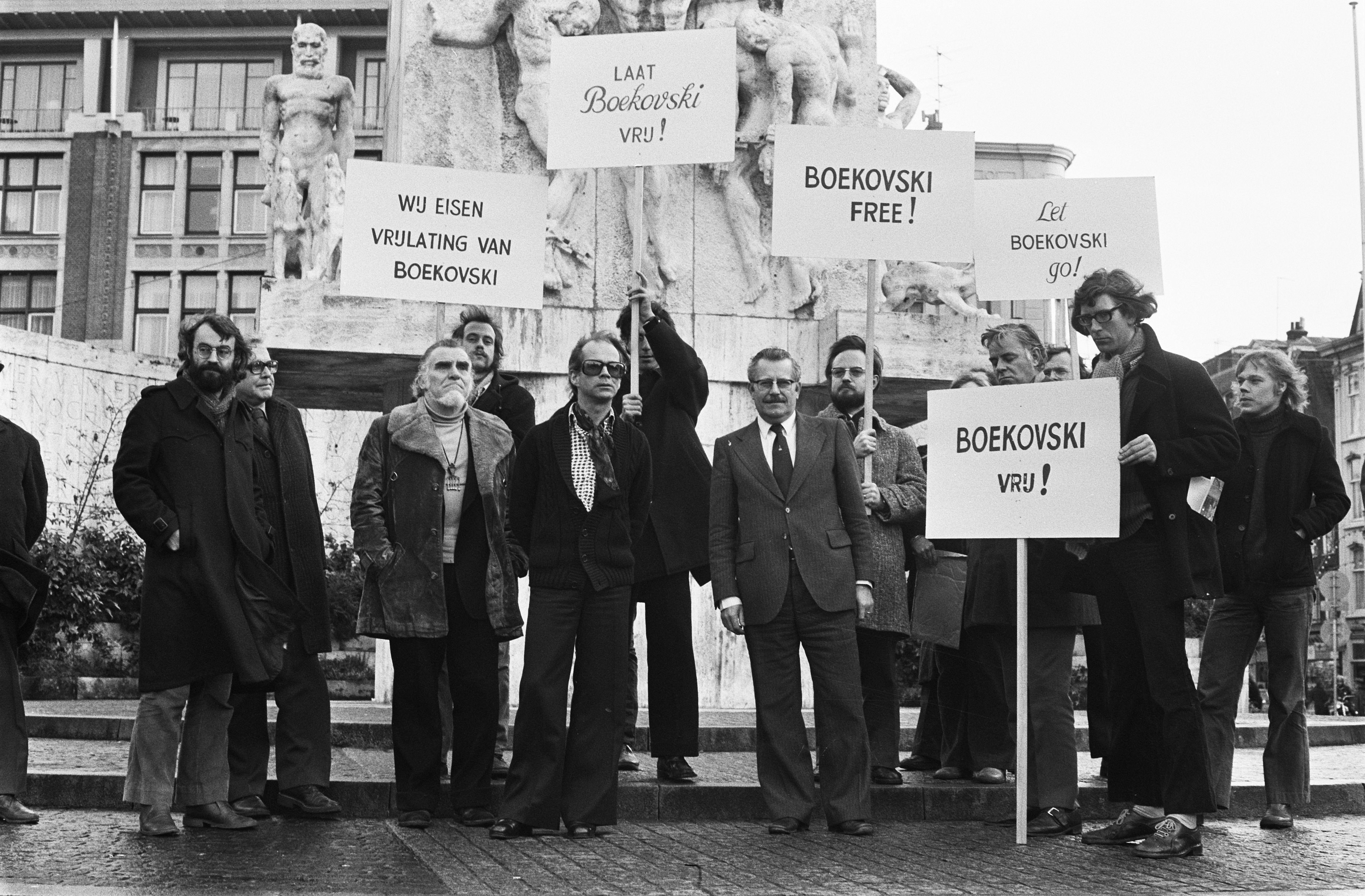

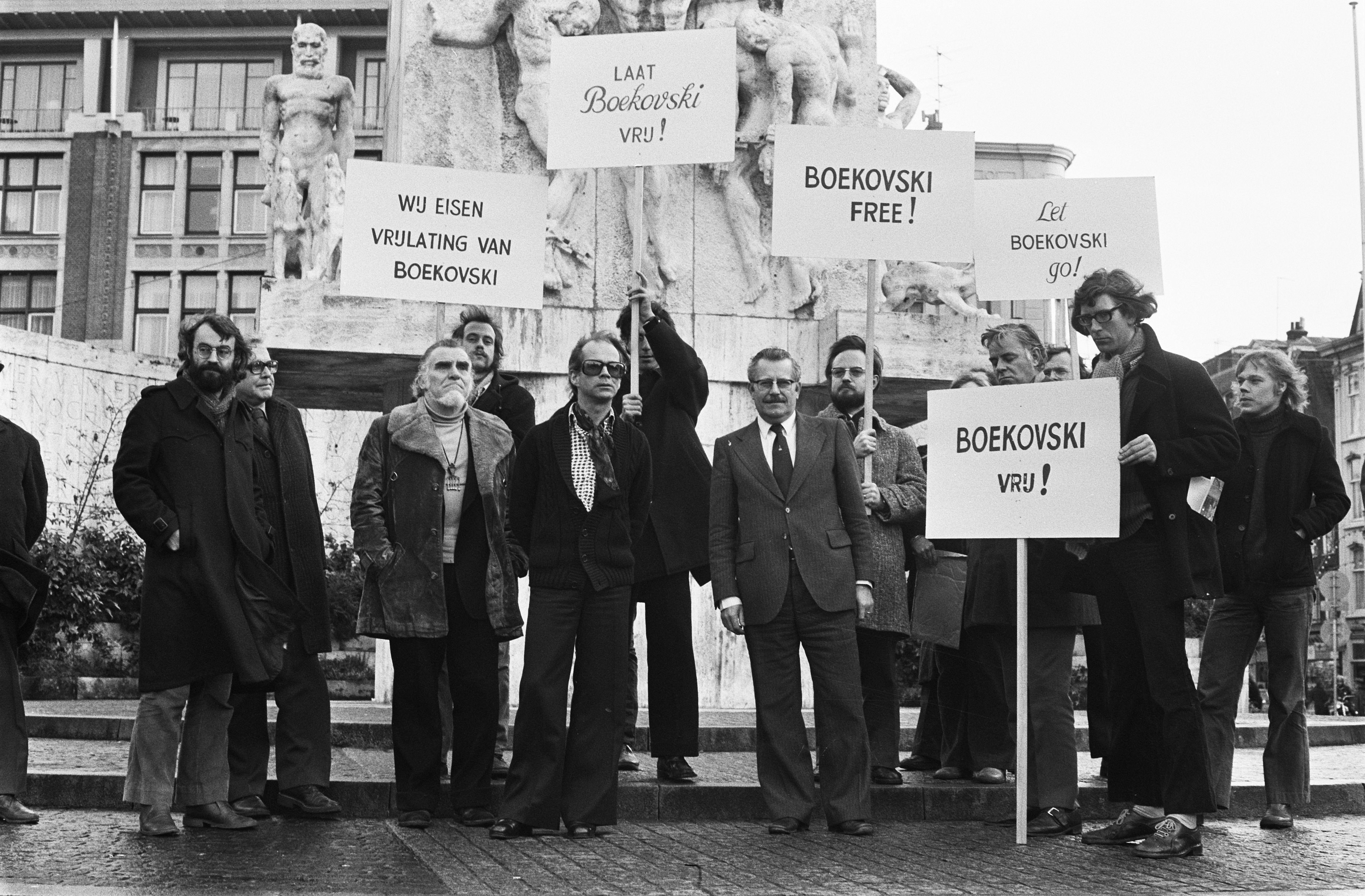

Deportation from the USSR (1976)

The fate of Bukovsky and other political prisoners in the Soviet Union had been repeatedly brought to world attention by Western diplomats and human rights groups such as the relatively new

The fate of Bukovsky and other political prisoners in the Soviet Union had been repeatedly brought to world attention by Western diplomats and human rights groups such as the relatively new Amnesty International

Amnesty International (also referred to as Amnesty or AI) is an international non-governmental organization focused on human rights, with its headquarters in the United Kingdom. The organization says that it has more than ten million members a ...

formed in 1961.Zürich

Zurich (; ) is the list of cities in Switzerland, largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zurich. It is in north-central Switzerland, at the northwestern tip of Lake Zurich. , the municipality had 448,664 inhabitants. The ...

airport by the Soviet government for the imprisoned general secretary of the Communist Party of Chile

The Communist Party of Chile (, ) is a communist party in Chile. It was founded in 1912 as the Socialist Workers' Party () and adopted its current name in 1922. The party established a youth wing, the Communist Youth of Chile (, JJ.CC), in 1932.

...

, Luis Corvalán.Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

in handcuffs.Soviet dissidents

Soviet dissidents were people who disagreed with certain features of Soviet ideology or with its entirety and who were willing to speak out against them. The term ''dissident'' was used in the Soviet Union (USSR) in the period from the mid-1960 ...

.Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

met with Bukovsky at the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

. In the USSR the meeting was seen by dissidents and rights activists as a sign of the newly elected president's willingness to stress human rights in his foreign policy; the event provoked harsh criticism by Soviet leaders.

Bukovsky moved to Great Britain where he settled in Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

and resumed his studies in biology, disrupted fifteen years earlier (see above) by his expulsion from Moscow University.

Life in the West

Bukovsky gained a master's degree in Biology

Biology is the scientific study of life and living organisms. It is a broad natural science that encompasses a wide range of fields and unifying principles that explain the structure, function, growth, History of life, origin, evolution, and ...

at Cambridge University

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

. He also wrote and published ''To Build a Castle: My Life as a Dissenter'' (1978). (The title in Russian, ''And the Wind Returns ...'', is a Biblical allusion.) The book was translated into English, French and German. It was published in Russian the following year by Chalidze publishers in New York. Today the Russian original is available online via a number of websites.

After he settled in the West, Bukovsky wrote many essays and polemical articles. These not only criticised the Soviet regime and, later, that of Vladimir Putin, but also exposed "Western gullibility" in the face of Soviet abuses and, in some cases, what he believed to be Western complicity in such crimes. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. It is bordered by Pakistan to the Durand Line, east and south, Iran to the Afghanistan–Iran borde ...

, Bukovsky campaigned with some success for an official UK and US boycott of the summer 1980 Olympics in Moscow. During the same years he voiced concern about the activities and policies of the Western peace movements.

In 1983, together with Cuban dissident Armando Valladares, Bukovsky co-founded and was later elected president of

In 1983, together with Cuban dissident Armando Valladares, Bukovsky co-founded and was later elected president of Resistance International

Resistance International was an international anti-communist organisation that existed between 1983 and 1988. It anticipated and embodied the so-called Reagan Doctrine which took final shape in 1985. Resistance International was set up in France i ...

.Jeane Kirkpatrick

Jeane Duane Kirkpatrick (née Jordan; November 19, 1926December 7, 2006) was an American diplomat and political scientist who played a major role in the foreign policy of the Ronald Reagan administration. An ardent anticommunist, she was a lon ...

while Midge Decter, Yuri Yarim-Agaev, Richard Perle

Richard Norman Perle (born September 16, 1941) is an American political advisor who served as the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Global Strategic Affairs under President Ronald Reagan. He began his political career as a senior staff member to ...

, Saul Bellow

Saul Bellow (born Solomon Bellows; June 10, 1915April 5, 2005) was a Canadian-American writer. For his literary work, Bellow was awarded the Pulitzer Prize, the 1976 Nobel Prize in Literature, and the National Medal of Arts. He is the only write ...

, Robert Conquest and Martin Colman were on the body's advisory committee. The Foundation aimed to be a co-ordinating centre for dissident and democratic movements seeking to overturn communism in Eastern Europe and elsewhere. It organised protests in the communist countries and in the West, and opposed western financial assistance to communist governments. The Foundation also created the National Council to Support Democratic Movements (National Council for Democracy) with the goal of aiding the emergence of democratic rule-of-law governments, and providing assistance with the writing of constitutions and the formation of civil institutions.

In March 1987, Bukovsky and nine other émigré authors ( Ernst Neizvestny, Yury Lyubimov, Vasily Aksyonov and Leonid Plyushch among them) caused a furore in the West and then in the Soviet Union itself when they raised doubts about the substance and sincerity of Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet and Russian politician who served as the last leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

's reforms.

Return to the Soviet Union (1991)

In April 1991, Vladimir Bukovsky visited Moscow for the first time since his deportation fifteen years before.

In the run-up to the 1991 presidential election, Boris Yeltsin

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin (1 February 1931 – 23 April 2007) was a Soviet and Russian politician and statesman who served as President of Russia from 1991 to 1999. He was a member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) from 1961 to ...

's campaign team included Bukovsky on their list of potential vice-presidential running-mates.Hero of the Soviet Union

The title Hero of the Soviet Union () was the highest distinction in the Soviet Union, awarded together with the Order of Lenin personally or collectively for heroic feats in service to the Soviet state and society. The title was awarded both ...

was selected. On 5 December 1991, both of Bukovsky's Soviet-era convictions were annulled by a decree of the RSFSR Supreme Court. The following year President Yeltsin formally restored Bukovsky's Russian citizenship: he had never been deprived of his Soviet citizenship, despite deportation from the country.

Post-Soviet period

British and European psychiatrists assessing the documents on psychiatric abuse released by Bukovsky characterised him in 1971: "The information we have about ladimir Bukovskysuggests that he is the sort of person who might be embarrassing to authorities in any country because he seems unwilling to compromise for convenience and personal comfort, and believes in saying what he thinks in situations which he clearly knows could endanger him. But such people often have much to contribute, and deserve considerable respect."

Soon after the collapse of the Soviet Union Vladimir Bukovsky was again out of favour with the Russian authorities. He supported Yeltsin against the Supreme Soviet in the 1993 Russian constitutional crisis in October that year but criticised the new Constitution of Russia

The Constitution of the Russian Federation () was adopted by national referendum on 12 December 1993 and enacted on 25 December 1993. The latest significant reform occurred in 2020, marked by extensive amendments that altered various sections ...

approved two months later, as being designed to ensure a continuation of Yeltsin's power. According to Bukovsky, Yeltsin became a hostage of the security agencies from 1994 onwards, and a restoration of KGB rule was inevitable.

''Judgment in Moscow''

In 1992, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union was formally dissolved as a sovereign state and subject of international law on 26 December 1991 by Declaration No. 142-N of the Soviet of the Republics of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. Declaration No. 142-Н of ...

, President Yeltsin's government invited Bukovsky to serve as an expert witness at the trial before the Constitutional Court

A constitutional court is a high court that deals primarily with constitutional law. Its main authority is to rule on whether laws that are challenged are in fact unconstitutional, i.e. whether they conflict with constitutionally established ru ...

where Russia's communists were suing Yeltsin for banning their Party and taking its property. The respondent's case was that the CPSU

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),. Abbreviated in Russian as КПСС, ''KPSS''. at some points known as the Russian Communist Party (RCP), All-Union Communist Party and Bolshevik Party, and sometimes referred to as the Soviet ...

itself had been an unconstitutional organisation.security clearance

A security clearance is a status granted to individuals allowing them access to classified information (state or organizational secrets) or to restricted areas, after completion of a thorough background check. The term "security clearance" is ...

), including KGB

The Committee for State Security (, ), abbreviated as KGB (, ; ) was the main security agency of the Soviet Union from 1954 to 1991. It was the direct successor of preceding Soviet secret police agencies including the Cheka, Joint State Polit ...

reports to the Central Committee. The copies were then smuggled to the West.

Bukovsky hoped that an international tribunal in Moscow might play a similar role to the first Nuremberg Trial (1945–1946) in post-Nazi Germany and help the country begin to overcome the legacy of Communism.

It took several years and a team of assistants to piece together the scanned fragments (many only half a page in width) of the hundreds of documents photocopied by Bukovsky and then, in 1999, to make them available online. Many of the same documents were extensively quoted and cited in Bukovsky's ''Judgment in Moscow'' (1995), where he described and analysed what he had uncovered about recent Soviet history and about the relations of the USSR and the CPSU with the West.Random House

Random House is an imprint and publishing group of Penguin Random House. Founded in 1927 by businessmen Bennett Cerf and Donald Klopfer as an imprint of Modern Library, it quickly overtook Modern Library as the parent imprint. Over the foll ...

bought the rights to the manuscript, but the publisher, in Bukovsky's words, tried to make the author "rewrite the whole book from the liberal left political perspective." Bukovsky resisted, explaining to the Random House editor that he was "allergic to political censorship" because of "certain peculiarities of my biography". (The contract was subsequently cancelled.).Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet and Russian politician who served as the last leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

by the British authorities after submitting to Westminster Magistrates' Court

Westminster Magistrates' Court is a Magistrates' court (England and Wales), magistrates' court at 181 Marylebone Road, London. The Chief Magistrate of England and Wales, who is the Senior Judiciary of England and Wales#District judges, Distric ...

materials on crimes against humanity

Crimes against humanity are certain serious crimes committed as part of a large-scale attack against civilians. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity can be committed during both peace and war and against a state's own nationals as well as ...

that the former Soviet leader had allegedly committed in the late 1980s and early 1990s by ordering military suppression of demonstrations in Lithuania

Lithuania, officially the Republic of Lithuania, is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, bordered by Latvia to the north, Belarus to the east and south, P ...

, Tbilisi

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი, ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), ( ka, ტფილისი, tr ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Georgia (country), largest city of Georgia ( ...

, Baku

Baku (, ; ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Azerbaijan, largest city of Azerbaijan, as well as the largest city on the Caspian Sea and in the Caucasus region. Baku is below sea level, which makes it the List of capital ci ...

and Tajikistan

Tajikistan, officially the Republic of Tajikistan, is a landlocked country in Central Asia. Dushanbe is the capital city, capital and most populous city. Tajikistan borders Afghanistan to the Afghanistan–Tajikistan border, south, Uzbekistan to ...

.

Potential 1996 presidential candidacy

In early 1996, a group of Moscow academics, journalists and intellectuals suggested that Vladimir Bukovsky should run for President of Russia as an alternative candidate to both incumbent President Boris Yeltsin

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin (1 February 1931 – 23 April 2007) was a Soviet and Russian politician and statesman who served as President of Russia from 1991 to 1999. He was a member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) from 1961 to ...

and his main challenger Gennady Zyuganov

Gennady Andreyevich Zyuganov (; born 26 June 1944) is a Russian politician who has been the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation and served as Member of the State Duma since 1993. He is also the Chair of the Union ...

of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation. However, no formal nomination process was initiated.

''Memento Gulag''

In 2001, Bukovsky was elected President of the '' Comitatus pro Libertatibus – Comitati per le Libertà – Freedom Committees'' in Florence, an Italian libertarian

Libertarianism (from ; or from ) is a political philosophy that holds freedom, personal sovereignty, and liberty as primary values. Many libertarians believe that the concept of freedom is in accord with the Non-Aggression Principle, according ...

organisation which promoted an annual ''Memento Gulag'', or Memorial Day devoted to the Victims of Communism, on 7 November (the anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of two revolutions in Russia in 1917. It was led by Vladimir L ...

).Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ) is the capital and largest city of Romania. The metropolis stands on the River Dâmbovița (river), Dâmbovița in south-eastern Romania. Its population is officially estimated at 1.76 million residents within a greater Buc ...

, Berlin, La Roche sur Yon and Paris.

Contacts with Boris Nemtsov and the Russian opposition

In 2002, Boris Nemtsov

Boris Yefimovich Nemtsov; (9 October 195927 February 2015) was a Russian physicist, liberalism in Russia, liberal politician, and outspoken critic of Vladimir Putin. Early in his political career, he was involved in the introduction of reform ...

, former Deputy Prime Minister of Russia who was then an elected member of the State Duma

A duma () is a Russian assembly with advisory or legislative functions.

The term ''boyar duma'' is used to refer to advisory councils in Russia from the 10th to 17th centuries. Starting in the 18th century, city dumas were formed across Russia ...

and leader of the Union of Rightist Forces, paid a visit to Bukovsky in Cambridge. He wanted to discuss the strategy of the Russian opposition. It was imperative, Bukovsky told Nemtsov, that Russian liberals adopt an uncompromising stand toward what he saw as the authoritarian government of President Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer who has served as President of Russia since 2012, having previously served from 2000 to 2008. Putin also served as Prime Minister of Ru ...

.

In January 2004, with Garry Kasparov

Garry Kimovich Kasparov (born Garik Kimovich Weinstein on 13 April 1963) is a Russian Grandmaster (chess), chess grandmaster, former World Chess Champion (1985–2000), political activist and writer. His peak FIDE chess Elo rating system, ra ...

, Boris Nemtsov

Boris Yefimovich Nemtsov; (9 October 195927 February 2015) was a Russian physicist, liberalism in Russia, liberal politician, and outspoken critic of Vladimir Putin. Early in his political career, he was involved in the introduction of reform ...

, Vladimir V. Kara-Murza and others, Bukovsky was a co-founder of Committee 2008. This umbrella organisation of the Russian democratic opposition was formed to ensure free and fair elections in 2008 when a successor to Vladimir Putin was elected.

In 2005, Bukovsky was among the prominent dissidents of the 1960s and 1970s ( Gorbanevskaya, Sergei Kovalyov, Eduard Kuznetsov, Alexander Podrabinek, Yelena Bonner) who took part in a documentary series by Vladimir Kara-Murza Jr. '' They Chose Freedom''.[They Chose Freedom](_blank)

a documentary series made by the 23-year-old journalist Vladimir Kara-Murza (in Russian) In 2013 Bukovsky was featured in a documentary series by Natella Boltyanskaya '' Parallels, Events, People''.

In 2009, Bukovsky joined the council of the new Solidarnost coalition which brought together a wide range of extra-parliamentary opposition forces.

Criticism of torture in Abu Ghraib prison

As revelations mounted about the sanctioned torture of captives in the Guantánamo Bay detention camp, Abu Ghraib and the CIA secret prisons, Bukovsky entered the discussion with an uncompromising attack on the official if covert rationalisation of torture. In an 18 December 2005 op-ed in ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'', locally known as ''The'' ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'' or ''WP'', is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C., the national capital. It is the most widely circulated newspaper in the Washington m ...

'', Bukovsky recounted his experience under torture in Lefortovo prison in 1971.Torture Memos

A set of legal memoranda known as the "Torture Memos" (officially the Memorandum Regarding Military Interrogation of Alien Unlawful Combatants Held Outside The United States) were drafted by John Yoo as Deputy Assistant Attorney General of the ...

on 20 January 2009, two days after taking office.

Russian agents in the European Union

In ''EUSSR'', a booklet written with Pavel Stroilov and published in 2004, Bukovsky exposed what he saw as the "Soviet roots of European Integration". Two years later, in an interview with ''The Brussels Journal'', Bukovsky said he had read confidential documents from secret Soviet files in 1992 which confirmed the existence of a "conspiracy" to turn the European Union into a socialist organisation. The European Union was a "monster", he argued, and it must be destroyed, the sooner the better, "before it develops into a full-fledged totalitarian state".GRU

Gru is a fictional character and the main protagonist of the ''Despicable Me'' film series.

Gru or GRU may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Gru (rapper), Serbian rapper

* Gru, an antagonist in '' The Kine Saga''

Organizations Georgia (c ...

classified as "agents of influence" and "confidential contacts":

This applied equally, Bukovsky cautioned, to post-Stalin generations of specialists on the USSR and Eastern Europe. They had been subjected to similar pressures and inducements in the 1970s and 1980s:

2008 presidential candidacy

In May 2007, Bukovsky announced his plans to run as candidate for president in the May 2008 Russian presidential election

8 (eight) is the natural number following 7 and preceding 9.

Etymology

English ''eight'', from Old English '', æhta'', Proto-Germanic ''*ahto'' is a direct continuation of Proto-Indo-European '' *oḱtṓ(w)-'', and as such cognate wi ...

.[Soviet dissident Vladimir Bukovsky has been nominated a candidate for president](_blank)

, Echo of Moscow, 16 December 2007[Bukovsky submitted his documents on time to the Central Electoral Commission](_blank)

, Newsru, 18 December 2007[CEC accepted documents from Vladimir Bukovsky](_blank)

, BBC Russian Service, 18 December 2007

Bukovsky's candidacy received the support of Grigory Yavlinsky, who announced on 14 December 2007 at the Yabloko party conference that he would forgo a campaign of his own and would instead support Bukovsky.

On 22 December 2007, the Central Electoral Commission turned down Bukovsky's application, on the grounds that he had failed to give information about his activities as a writer when submitting his documents, that he was holding a British residence permit, and that he had not been living in Russia during the past ten years.Supreme Court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

on 28 December 2007 and, subsequently, before its cassation board on 15 January 2008.

Conflict with Putin's regime

Bukovsky was among the first 34 signatories of " Putin must go", an online anti-Putin manifesto published on 10 March 2010. In May 2012, Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer who has served as President of Russia since 2012, having previously served from 2000 to 2008. Putin also served as Prime Minister of Ru ...

began his third term as president of the Russian Federation after serving four years as the country's prime minister. The following year, Bukovsky published a collection of interviews in Russia which described Putin and his team as ''The heirs of Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria ka, ლავრენტი პავლეს ძე ბერია} ''Lavrenti Pavles dze Beria'' ( – 23 December 1953) was a Soviet politician and one of the longest-serving and most influential of Joseph ...

'', Stalin's last and most notorious secret police chief.

In March 2014 Russia annexed Crimea after Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

had lost control of its government buildings, airports and military bases in Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

to unmarked soldiers and local pro-Russian militias. The West responded with sanctions targeted at Putin's immediate entourage, and Bukovsky expressed the hope that this would prove the end of his regime.

In October 2014, the Russian authorities declined to issue Bukovsky with a new foreign-travel passport. The Russian Foreign Ministry stated that it could not confirm Bukovsky's citizenship

Citizenship is a membership and allegiance to a sovereign state.

Though citizenship is often conflated with nationality in today's English-speaking world, international law does not usually use the term ''citizenship'' to refer to nationalit ...

. The response was met with surprise from the Presidential Human Rights Council and the Human Rights ombudsman of the Russian Federation.

On 17 March 2015, at the long-delayed inquiry into Alexander Litvinenko

Alexander Valterovich Litvinenko (30 August 1962 ( at WebCite) – 23 November 2006) was a British-naturalised Russian defector and former officer of the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) who specialised in tackling organized crime, ...

's fatal poisoning Bukovsky gave his views as to why Litvinenko had been assassinated. Interviewed on BBC TV eight years before, Bukovsky expressed no doubt that the Russian authorities were responsible for the London death of Litvinenko on 23 November 2006.

Child pornography case

On October 28, 2014, Bukovsky was accused in the UK of the possession of child pornography

Child pornography (also abbreviated as CP, also called child porn or kiddie porn, and child sexual abuse material, known by the acronym CSAM (underscoring that children can not be deemed willing participants under law)), is Eroticism, erotic ma ...

.Forensic

Forensic science combines principles of law and science to investigate criminal activity. Through crime scene investigations and laboratory analysis, forensic scientists are able to link suspects to evidence. An example is determining the time and ...

examination of Bukovsky's hard drive

A hard disk drive (HDD), hard disk, hard drive, or fixed disk is an electro-mechanical data storage device that stores and retrieves digital data using magnetic storage with one or more rigid rapidly rotating hard disk drive platter, pla ...

s revealed thousands of child abuse images and videoshunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance where participants fasting, fast as an act of political protest, usually with the objective of achieving a specific goal, such as a policy change. Hunger strikers that do not take fluids are ...

and sued the Crown Prosecution Service

The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) is the principal public agency for conducting criminal prosecutions in England and Wales. It is headed by the Director of Public Prosecutions.

The main responsibilities of the CPS are to provide legal adv ...

for libel.[Soviet-Era Dissident Vladimir Bukovsky Dies Aged 76](_blank)

by RFE/RL

Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) is a media organization broadcasting news and analyses in 27 languages to 23 countries across Eastern Europe, Central Asia, the Caucasus, and the Middle East. Headquartered in Prague since 1995, RFE/RL ...

, October 28, 2019 The initial examination of his computer by police expert did not find any evidence of the hacking.Bill Gertz

William D. Gertz (born March 28, 1952) is an American editor, columnist and reporter for ''The Washington Times''. He is the author of eight books and writes a weekly column on the Pentagon and national security issues called "Inside the Ring". Du ...

, Bukovsky was targeted "in a Russian disinformation operation shortly before he was to testify before the Owen commission in March 2015. A Russian hacker broke into his laptop computer and planted child pornography photographs on the device. A Russian intelligence agent then tipped off the European Union law enforcement agency, Europol

Europol, officially the European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation, is the law enforcement agency of the European Union (EU). Established in 1998, it is based in The Hague, Netherlands, and serves as the central hub for coordinating c ...

, to the photos... It was a classic Russian disinformation and influence operation".

Death

Bukovsky died of a heart attack on 27 October 2019 at the age of 76 in Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

, Cambridgeshire.Highgate Cemetery

Highgate Cemetery is a place of burial in North London, England, designed by architect Stephen Geary. There are approximately 170,000 people buried in around 53,000 graves across the West and East sides. Highgate Cemetery is notable both for so ...

.

Bibliography

; In translation

* 1978: 352 pp.

** 1979: 386 pp.

** 1979:

** 2007:

* 1987:

* 1995: 616 pp.

**

** (1996) ''Abrechnung mit Moskau. Das sowjetische Unrechtsregime und die Schuld des Westens'', Bergisch Gladbach

**

*

''Judgment in Moscow: Soviet Crimes and Western Complicity''

(May 2019)

* 1999

''Soviet Archives''

Online archive compiled by Vladimir Bukovsky, prepared for publication by the late Julia Zaks (1938–2014) and Leonid Chernikhov

* 2016

''The Bukovsky Archives''

upgraded version of 1999 archive.

* 2019

''Judgment in Moscow: Soviet crimes and Western complicity''

; In Russian

* 1979: 382 pp. The first publication in Russian of Bukovsky's memoirs was given a Biblical title (see Ecclesiastes, v. 6).

* 1989: The first publication of Bukovsky's memoirs in the USSR.

* 1996:

* 2001:

* 2007: (First serialised in ''Teatr'' periodical, see above, 1989).

* 2008:

* 2013:

* 2014:

* 2015:

Documentaries

* ''Bukovsky'' (1977) – documentary by Alan Clarke.

* '' They Chose Freedom'' (2005) (4 parts) – documentary by Vladimir Kara-Murza Jr.

* ''Russia/Chechnya: Voices of Dissent'' (2005) ''–'' with Bukovsky, Yelena Bonner, Natalya Gorbanevskaya

Natalya Yevgenyevna Gorbanevskaya ( rus, Ната́лья Евге́ньевна Горбане́вская, p=nɐˈtalʲjə jɪvˈɡʲenʲjɪvnə ɡərbɐˈnʲefskəjə, a=Natal'ya Yevgen'yevna Gorbanyevskaya.ru.vorb.oga; 26 May 1936 – 29 No ...

, Anna Politkovskaya, Akhmed Zakayev and others.

References

''A Chronicle of Current Events'' (1968–1982)

Other

Further reading

In the Soviet Union

*

*

*

*

After his expulsion to the West

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Two years on

*

*

*

*

To Build a Castle (1978)

*

Judgement in Moscow (1995)

*

In the 21st century

*

*

External links

In English

* : May 1989, "The Democratic Revolution in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union" (forum).

Vladimir Bukovsky

News archives, links, photos, video, public domain writings, official statements, contact info, maintained by US group Bukovsky Center

Russia/Chechnya: Voices of Dissent (2005)

– features Vladimir Bukovsky, Yelena Bonner, Natalya Gorbanevskaya

Natalya Yevgenyevna Gorbanevskaya ( rus, Ната́лья Евге́ньевна Горбане́вская, p=nɐˈtalʲjə jɪvˈɡʲenʲjɪvnə ɡərbɐˈnʲefskəjə, a=Natal'ya Yevgen'yevna Gorbanyevskaya.ru.vorb.oga; 26 May 1936 – 29 No ...

, Anna Politkovskaya, Akhmed Zakayev and others.

* Uploaded on 7 January 2012.

The Bukovsky Archives: Communism on Trial

Contains over seven hundred classified Soviet documents (1937–1994), an abridged translation of ''Judgement in Moscow'', an

many of the author's key articles since 1976 ("Books, Articles & Letters")

"The suppression of dissent, 1970–1979"

in the Bukovsky Archives (above) includes documents concerning Bukovsky: his activities as a Soviet dissident; his periods of imprisonment in the USSR; his exchange in 1976 for Luis Corvalan; and his ongoing campaign in the West against the Soviet regime.

Tagged references to Bukovsky in the ''Chronicle of Current Events'' (1968–1982). Also see entry in that website'

Name Index

In Russian

* An Alphabet of Dissent: Bukovsky (2011)

* Bukovsky on Voice of America (2014)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bukovsky, Vladimir

1942 births

2019 deaths

20th-century Russian male writers

20th-century Russian writers

21st-century Russian writers

Alumni of King's College, Cambridge

Amnesty International prisoners of conscience held by the Soviet Union

Burials at Highgate Cemetery

Campaign Against Psychiatric Abuse

Cato Institute people

Inmates of Lefortovo Prison

Inmates of Vladimir Central Prison

Members of the Freedom Association

Neurophysiologists

People from Belebey

Psychiatric survivor activists

Russian anti-communists

Russian dissidents

Russian emigrants to the United Kingdom

Russian memoirists

Russian non-fiction writers

Russian activists

Russian political writers

Russian prisoners and detainees

Solidarnost politicians

Soviet dissidents

Soviet emigrants to the United Kingdom

Soviet expellees

Soviet human rights activists

Soviet male writers

Soviet non-fiction writers

Soviet prisoners and detainees

Soviet psychiatric abuse whistleblowers

Stanford University alumni

Male non-fiction writers

The fate of Bukovsky and other political prisoners in the Soviet Union had been repeatedly brought to world attention by Western diplomats and human rights groups such as the relatively new

The fate of Bukovsky and other political prisoners in the Soviet Union had been repeatedly brought to world attention by Western diplomats and human rights groups such as the relatively new  In 1983, together with Cuban dissident Armando Valladares, Bukovsky co-founded and was later elected president of

In 1983, together with Cuban dissident Armando Valladares, Bukovsky co-founded and was later elected president of