Timeline of United States discoveries on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Timeline of United States discoveries encompasses the breakthroughs of human thought and knowledge of new scientific findings, phenomena, places, things, and what was previously unknown to exist. From a historical standpoint, the timeline below of United States discoveries dates from the 18th century to the current 21st century, which have been achieved by discoverers who are either native-born or naturalized citizens of the United States.

With an emphasis of discoveries in the fields of

Palmyra Atoll, a

Palmyra Atoll, a

Hadrosaurus was a dubious genus of a hadrosaurid dinosaur that lived near what is now the coast of New Jersey in the late

Hadrosaurus was a dubious genus of a hadrosaurid dinosaur that lived near what is now the coast of New Jersey in the late  The Red Delicious is a clone of

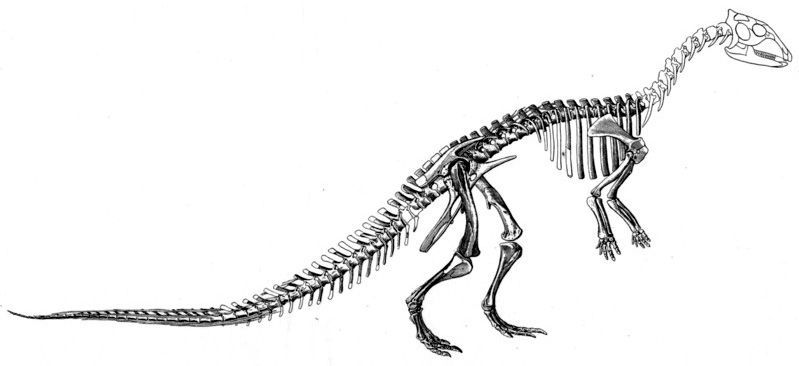

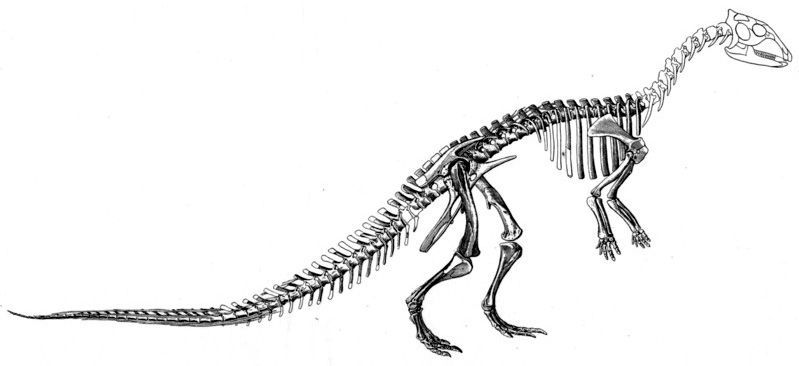

The Red Delicious is a clone of  Thescelosaurus was a bipedal dinosaur with a sturdy build, small wide hands, and a long pointed snout from the Late Cretaceous Period, approximately 66 million years ago. As a herbivore, Thescelosaurus was not a tall dinosaur and probably browsed the ground selectively to find food. Its leg structure and proportionally heavy build suggests that it was not a fast runner like other dinosaurs. The first fossils of Thescelosaurus were co-discovered in 1891 by John Bell Hatcher and William H. Utterback, in Wyoming. However, this discovery remained stored until Charles W. Gilmore named the dinosaur in 1913.

1892 Amalthea

Amalthea is the third moon of Jupiter in order of distance from the planet. It was discovered on September 9, 1892, by

Thescelosaurus was a bipedal dinosaur with a sturdy build, small wide hands, and a long pointed snout from the Late Cretaceous Period, approximately 66 million years ago. As a herbivore, Thescelosaurus was not a tall dinosaur and probably browsed the ground selectively to find food. Its leg structure and proportionally heavy build suggests that it was not a fast runner like other dinosaurs. The first fossils of Thescelosaurus were co-discovered in 1891 by John Bell Hatcher and William H. Utterback, in Wyoming. However, this discovery remained stored until Charles W. Gilmore named the dinosaur in 1913.

1892 Amalthea

Amalthea is the third moon of Jupiter in order of distance from the planet. It was discovered on September 9, 1892, by

Tyrannosaurus, a bipedal carnivore, is a genus of theropod dinosaur. The species Tyrannosaurus rex, commonly abbreviated to T. rex, is a fixture in popular culture. It lived throughout what is now western North America, with a much wider range than other tyrannosaurids. Fossils are found in a variety of rock formations dating to the last two million years of the

Tyrannosaurus, a bipedal carnivore, is a genus of theropod dinosaur. The species Tyrannosaurus rex, commonly abbreviated to T. rex, is a fixture in popular culture. It lived throughout what is now western North America, with a much wider range than other tyrannosaurids. Fossils are found in a variety of rock formations dating to the last two million years of the  Golden Delicious is a large, yellow skinned cultivar of apple and very sweet to the taste. The original Golden Delicious tree is thought to have been discovered by Anderson Mullins on a hill near Porter Creek in Clay County, West Virginia. The Stark Brothers Nursery soon purchased the tree which spawned a leading cultivar in the United States and abroad. The Golden Delicious is the state fruit of West Virginia.

1912 Smoking-cancer link

* Dr. Isaac Adler was the first to strongly suggest that lung cancer is related to smoking in 1912.

1914 Sinope

* Sinope is a retrograde irregular satellite of Jupiter discovered by Seth Barnes Nicholson at

Golden Delicious is a large, yellow skinned cultivar of apple and very sweet to the taste. The original Golden Delicious tree is thought to have been discovered by Anderson Mullins on a hill near Porter Creek in Clay County, West Virginia. The Stark Brothers Nursery soon purchased the tree which spawned a leading cultivar in the United States and abroad. The Golden Delicious is the state fruit of West Virginia.

1912 Smoking-cancer link

* Dr. Isaac Adler was the first to strongly suggest that lung cancer is related to smoking in 1912.

1914 Sinope

* Sinope is a retrograde irregular satellite of Jupiter discovered by Seth Barnes Nicholson at

/ref> 1927 Following the discovery of the planet Neptune in 1846, there was considerable speculation that another planet might exist beyond its orbit. The search began in the mid-19th century but culminated at the start of the 20th century with a quest for Planet X.

Following the discovery of the planet Neptune in 1846, there was considerable speculation that another planet might exist beyond its orbit. The search began in the mid-19th century but culminated at the start of the 20th century with a quest for Planet X.  In 1953, based on X-ray diffraction images and the information that the bases were paired,

In 1953, based on X-ray diffraction images and the information that the bases were paired,  Lucy is the common name of AL 288–1, several hundred pieces of bone representing about 40% of the skeleton of an individual Australopithecus afarensis. Lucy is reckoned to have lived 3.2 million years ago. This

Lucy is the common name of AL 288–1, several hundred pieces of bone representing about 40% of the skeleton of an individual Australopithecus afarensis. Lucy is reckoned to have lived 3.2 million years ago. This  The planet

The planet  First launched in 1715 from London, England, the ''Whydah'' was a three-masted ship of galley-style design measuring in length, rated at 300 tons burden, and could travel at speeds up to . Christened ''Whydah'' after the West African slave trading kingdom of

First launched in 1715 from London, England, the ''Whydah'' was a three-masted ship of galley-style design measuring in length, rated at 300 tons burden, and could travel at speeds up to . Christened ''Whydah'' after the West African slave trading kingdom of  The RMS ''Titanic'' was an ''Olympic'' class passenger liner owned by the

The RMS ''Titanic'' was an ''Olympic'' class passenger liner owned by the

Eris, formal designation 136199 Eris, is the largest-known dwarf planet in the Solar System and the ninth-largest body known to orbit the Sun directly. It is approximately 2,500 kilometres in diameter and 27% more massive than the dwarf planet Pluto. Eris was discovered in 2005 at W. M. Keck Observatory by American astronomer Michael E. Brown.

2005 Dysnomia (moon), Dysnomia

Dysnomia, officially (136199) Eris I Dysnomia, is the only known moon of the dwarf planet Eris. In conjunction of finding Eris, American astronomer Michael E. Brown discovered Eris' satellite, Dysnomia, at W. M. Keck Observatory in 2005.

2005 Hydra (moon), Hydra

Hydra is the outer-most natural satellite of

Eris, formal designation 136199 Eris, is the largest-known dwarf planet in the Solar System and the ninth-largest body known to orbit the Sun directly. It is approximately 2,500 kilometres in diameter and 27% more massive than the dwarf planet Pluto. Eris was discovered in 2005 at W. M. Keck Observatory by American astronomer Michael E. Brown.

2005 Dysnomia (moon), Dysnomia

Dysnomia, officially (136199) Eris I Dysnomia, is the only known moon of the dwarf planet Eris. In conjunction of finding Eris, American astronomer Michael E. Brown discovered Eris' satellite, Dysnomia, at W. M. Keck Observatory in 2005.

2005 Hydra (moon), Hydra

Hydra is the outer-most natural satellite of

astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

, physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

, chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

, medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for patients, managing the Medical diagnosis, diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, ...

, biology

Biology is the scientific study of life and living organisms. It is a broad natural science that encompasses a wide range of fields and unifying principles that explain the structure, function, growth, History of life, origin, evolution, and ...

, geology

Geology (). is a branch of natural science concerned with the Earth and other astronomical objects, the rocks of which they are composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Earth ...

, paleontology

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure ge ...

, and archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

, United States citizens acclaimed in their professions have contributed much. For example, the "Bone Wars

The Bone Wars, also known as the Great Dinosaur Rush, was a period of intense and ruthlessly competitive fossil hunting and discovery during the Gilded Age of American history, marked by a heated rivalry between Edward Drinker Cope (of the Aca ...

," beginning in 1877 and ending in 1892, was an intense period of rivalry between two American paleontologists, Edward Drinker Cope

Edward Drinker Cope (July 28, 1840 – April 12, 1897) was an American zoologist, paleontology, paleontologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist, herpetology, herpetologist, and ichthyology, ichthyologist. Born to a wealthy Quaker fam ...

and Othniel Charles Marsh

Othniel Charles Marsh (October 29, 1831 – March 18, 1899) was an American professor of paleontology. A prolific fossil collector, Marsh was one of the preeminent paleontologists of the nineteenth century. Among his legacies are the discovery or ...

, who initiated several expeditions throughout North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

in the pursuit of discovering, identifying, and finding new species of dinosaur fossils. In total, their large efforts resulted in when 142 species of dinosaurs being discovered. With the founding of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the United States's civil space program, aeronautics research and space research. Established in 1958, it su ...

(NASA) in 1958, a vision and continued commitment by the United States of finding extraterrestrial and astronomical discoveries has helped the world to better understand the Solar System

The Solar SystemCapitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Sola ...

and universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents. It comprises all of existence, any fundamental interaction, physical process and physical constant, and therefore all forms of matter and energy, and the structures they form, from s ...

. As one example, in 2008, the ''Phoenix'' lander discovered the presence of frozen water on the planet Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun. It is also known as the "Red Planet", because of its orange-red appearance. Mars is a desert-like rocky planet with a tenuous carbon dioxide () atmosphere. At the average surface level the atmosph ...

of which scientists such as Peter H. Smith

Peter Hopkinson Smith (born January 17, 1940) is a scholar of Latin American history, politics, economics, and diplomacy. He is a distinguished Professor Emeritus of Political Science and the Simon Bolivar Professor of Latin American Studies a ...

of the University of Arizona

The University of Arizona (Arizona, U of A, UArizona, or UA) is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Tucson, Arizona, United States. Founded in 1885 by the 13th Arizona Territorial Legislature, it ...

Lunar and Planetary Laboratory (LPL) had suspected before the mission confirmed its existence.

Eighteenth century

1747Charge conservation

In physics, charge conservation is the principle, of experimental nature, that the total electric charge in an isolated system never changes. The net quantity of electric charge, the amount of positive charge minus the amount of negative charg ...

* In physics, charge conservation is the principle that electric charge

Electric charge (symbol ''q'', sometimes ''Q'') is a physical property of matter that causes it to experience a force when placed in an electromagnetic field. Electric charge can be ''positive'' or ''negative''. Like charges repel each other and ...

can neither be created nor destroyed. The quantity of electric charge, the amount of positive charge

Electric charge (symbol ''q'', sometimes ''Q'') is a physical property of matter that causes it to experience a force when placed in an electromagnetic field. Electric charge can be ''positive'' or ''negative''. Like charges repel each other and ...

minus the amount of negative charge in the universe, is always conserved. As part of his groundbreaking work in electricity, Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

around the year 1747 discovered the principle of charge conservation when he came to the conclusion that the two states of electricity, positive and negative, the charge is never created or destroyed but instead transferable from one place to another.

1796 Johnston Atoll

Johnston Atoll is an Unincorporated territories of the United States, unincorporated territory of the United States, under the jurisdiction of the United States Air Force (USAF). The island is closed to public entry, and limited access for mana ...

* Johnston Atoll, a territory of the United States

Territories of the United States are sub-national administrative divisions and dependent territory, dependent territories overseen by the federal government of the United States. The American territories differ from the U.S. states and Indi ...

, part of the Pacific Islands Heritage Marine National Monument, and a part of the wider United States Minor Outlying Islands

The United States Minor Outlying Islands is a statistical designation applying to the minor outlying islands and groups of islands that comprise eight United States insular areas in the Pacific Ocean (Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Isla ...

, is a 50-square-mile (130 km2) atoll in the North Pacific Ocean

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north'' ...

about west of the U.S. state of Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; ) is an island U.S. state, state of the United States, in the Pacific Ocean about southwest of the U.S. mainland. One of the two Non-contiguous United States, non-contiguous U.S. states (along with Alaska), it is the only sta ...

. There are four islands located on the coral reef platform, two natural islands, Johnston Island and Sand Island, which have been expanded by coral dredging, as well as North Island (Akau) and East Island (Hikina), an additional two artificial islands formed by coral dredging. The sovereignty of Johnston Atoll was disputed and claimed by the Kingdom of Hawaii

The Hawaiian Kingdom, also known as the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ɛ ɐwˈpuni həˈvɐjʔi, was an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country from 1795 to 1893, which eventually encompassed all of the inhabited Hawaii ...

beginning in 1858 until Hawaii itself was eventually annexed by the United States as the Hawaii Territory

The Territory of Hawaii or Hawaii Territory ( Hawaiian: ''Panalāʻau o Hawaiʻi'') was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from April 30, 1900, until August 21, 1959, when most of its territory, excluding ...

in 1898. Johnston Atoll is now administered and managed by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service

The United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS or FWS) is a List of federal agencies in the United States, U.S. federal government agency within the United States Department of the Interior which oversees the management of fish, wildlife, ...

, an agency of the United States Department of Interior

The United States Department of the Interior (DOI) is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the management and conservation of most federal lands and natural resources. It also administers programs relating t ...

. In 1796, Johnston Atoll was discovered accidentally by U.S. Captain Joseph Pierpoint when his ship, the American brig ''Sally'', ran aground.

1798 Tabuaeran

Tabuaeran, also known as Fanning Island, is an atoll that is part of the Line Islands of the central Pacific Ocean and part of the island nation of Kiribati. The land area is , and the population in 2015 was 2,315. The maximum elevation is abou ...

* Tabuaeran, also known as Fanning Island or Fanning Atoll (both Gilbertese and English names are recognized) is one of the Line Islands

The Line Islands, Teraina Islands or Equatorial Islands () are a chain of 11 atolls (with partly or fully enclosed lagoons, except Vostok and Jarvis) and coral islands (with a surrounding reef) in the central Pacific Ocean, south of the Hawa ...

located in the central Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

. With a population of approximately 2,500, much of the island's economy relies upon the cruise industry. Formerly under British rule, Tabuaeran now is a part of the Republic of Kiribati. Tabuaeran was discovered on June 11, 1798, by U.S. Captain Edmund Fanning, at 3 a.m., while on a voyage to China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

aboard his ship, ''Betsy''.

1798 Teraina

Teraina (written also Teeraina, also known as Washington Island – these two names are Constitution of Kiribati, constitutional) is a coral atoll in the central Pacific Ocean and part of the Northern Line Islands which belong to Kiribati. Ob ...

* Teraina, also known as Washington Island, is an inhabited coral atoll located in the central Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

that is north of the equator

The equator is the circle of latitude that divides Earth into the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Southern Hemisphere, Southern Hemispheres of Earth, hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, about in circumferen ...

, northwest of Tabuaeran

Tabuaeran, also known as Fanning Island, is an atoll that is part of the Line Islands of the central Pacific Ocean and part of the island nation of Kiribati. The land area is , and the population in 2015 was 2,315. The maximum elevation is abou ...

, northwest of Christmas Island

Christmas Island, officially the Territory of Christmas Island, is an States and territories of Australia#External territories, Australian external territory in the Indian Ocean comprising the island of the same name. It is about south o ...

, and southeast of the U.S. territory of Palmyra Atoll

Palmyra Atoll (), also referred to as Palmyra Island, is one of the Line Islands, Northern Line Islands (southeast of Kingman Reef and north of Kiribati). It is located almost due south of the Hawaiian Islands, roughly one-third of the way be ...

. Formerly under British rule, Teraina is now a part of the Republic of Kiribati. Obsolete names of Teraina are Prospect Island and New York Island. The island consists of nine Polynesian villages. Teraina was discovered by U.S. Captain Edmund Fanning, in the American ship ''Betsy'', on June 12, 1798.

1798 Palmyra Atoll

Palmyra Atoll (), also referred to as Palmyra Island, is one of the Line Islands, Northern Line Islands (southeast of Kingman Reef and north of Kiribati). It is located almost due south of the Hawaiian Islands, roughly one-third of the way be ...

Palmyra Atoll, a

Palmyra Atoll, a territory of the United States

Territories of the United States are sub-national administrative divisions and dependent territory, dependent territories overseen by the federal government of the United States. The American territories differ from the U.S. states and Indi ...

, part of the Pacific Islands Heritage Marine National Monument, and a part of the wider United States Minor Outlying Islands

The United States Minor Outlying Islands is a statistical designation applying to the minor outlying islands and groups of islands that comprise eight United States insular areas in the Pacific Ocean (Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Isla ...

, is a atoll located in the North Pacific Ocean

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north'' ...

almost due south of the Hawaiian Islands

The Hawaiian Islands () are an archipelago of eight major volcanic islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the Pacific Ocean, North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the Hawaii (island), island of Hawaii in the south to nort ...

, roughly halfway between the U.S. state of Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; ) is an island U.S. state, state of the United States, in the Pacific Ocean about southwest of the U.S. mainland. One of the two Non-contiguous United States, non-contiguous U.S. states (along with Alaska), it is the only sta ...

and the U.S. territory of American Samoa

American Samoa is an Territories of the United States, unincorporated and unorganized territory of the United States located in the Polynesia region of the Pacific Ocean, South Pacific Ocean. Centered on , it is southeast of the island count ...

. The atoll consists of an extensive reef, two shallow lagoons, and some 50 sand and reef-rock islets and bars covered with lush, tropical vegetation. The islets of the atoll are all connected, except Sand Island and the two Home Islets in the west and Barren Island in the east. The largest island is Cooper Island in the north, followed by Kaula Island in the south. Cooper Island is privately owned by The Nature Conservancy

The Nature Conservancy (TNC) is a global environmental organization headquartered in Arlington, Virginia, United States. it works via affiliates or branches in 79 countries and territories, as well as across every state in the US.

Founded in ...

and managed as a nature reserve. The rest of the atoll is managed by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service

The United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS or FWS) is a List of federal agencies in the United States, U.S. federal government agency within the United States Department of the Interior which oversees the management of fish, wildlife, ...

and is directly administered by the Office of Insular Affairs

The Office of Insular Affairs (OIA) is a unit of the United States Department of the Interior that oversees federal administration of several United States insular areas. It is the successor to the Bureau of Insular Affairs of the War Departm ...

, an agency of the United States Department of Interior

The United States Department of the Interior (DOI) is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the management and conservation of most federal lands and natural resources. It also administers programs relating t ...

. Palmyra Atoll's history is long and colorful. It was first sighted on June 14, 1798, by Captain Edmund Fanning and officially discovered in 1802 by Captain Sawle of the American ship ''Palmyra''.

1798 Kingman Reef

Kingman Reef () is a largely submerged, uninhabited, triangle-shaped reef, geologically an atoll, east-west and north-south, in the North Pacific Ocean, roughly halfway between the Hawaiian Islands and American Samoa. It has an area of 3 hecta ...

* Kingman Reef, a territory of the United States

Territories of the United States are sub-national administrative divisions and dependent territory, dependent territories overseen by the federal government of the United States. The American territories differ from the U.S. states and Indi ...

, part of the Pacific Islands Heritage Marine National Monument, and a part of the wider United States Minor Outlying Islands

The United States Minor Outlying Islands is a statistical designation applying to the minor outlying islands and groups of islands that comprise eight United States insular areas in the Pacific Ocean (Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Isla ...

, is a largely submerged, uninhabited triangular shaped reef, 9.5 nautical miles (18 kilometers) east-west and 5 nautical miles (9 kilometers) north-south, located in the North Pacific Ocean

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north'' ...

, roughly halfway between the Hawaiian Islands

The Hawaiian Islands () are an archipelago of eight major volcanic islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the Pacific Ocean, North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the Hawaii (island), island of Hawaii in the south to nort ...

and the U.S. territory of American Samoa

American Samoa is an Territories of the United States, unincorporated and unorganized territory of the United States located in the Polynesia region of the Pacific Ocean, South Pacific Ocean. Centered on , it is southeast of the island count ...

. It is the northernmost of the Northern Line Islands and lies 36 nautical miles (67 kilometers) northwest of the next closest island, the U.S. territory of Palmyra Atoll

Palmyra Atoll (), also referred to as Palmyra Island, is one of the Line Islands, Northern Line Islands (southeast of Kingman Reef and north of Kiribati). It is located almost due south of the Hawaiian Islands, roughly one-third of the way be ...

, and 930 nautical miles (1,720 kilometers) south of Honolulu, Hawaii

Honolulu ( ; ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, located in the Pacific Ocean. It is the county seat of the Consolidated city-county, consolidated City and County of Honol ...

. Kingman Reef is now administered and managed by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service

The United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS or FWS) is a List of federal agencies in the United States, U.S. federal government agency within the United States Department of the Interior which oversees the management of fish, wildlife, ...

, an agency of the United States Department of Interior

The United States Department of the Interior (DOI) is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the management and conservation of most federal lands and natural resources. It also administers programs relating t ...

. First known as "Dangerous Reef", Kingman Reef was discovered on June 14, 1798, by U.S. Captain Edmund Fanning.

Nineteenth century

1821South Orkney Islands

The South Orkney Islands are a group of List of Antarctic and sub-Antarctic islands, islands in the Southern Ocean, about north-east of the tip of the Antarctic PeninsulaSouthern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the world ocean, generally taken to be south of 60th parallel south, 60° S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is the seco ...

, about northeast of the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula

The Antarctic Peninsula, known as O'Higgins Land in Chile and Tierra de San Martin in Argentina, and originally as Graham Land in the United Kingdom and the Palmer Peninsula in the United States, is the northernmost part of mainland Antarctica.

...

. As part of the British Antarctic Territory, the islands have a total area of about . In December 1821, Captain Nathaniel B. Palmer as commander of the ''James Monroe'', along with British sealer George Powell, co-discovered the South Orkney Islands.

1822 Howland Island

Howland Island () is a coral island and strict nature reserve located just north of the equator in the central Pacific Ocean, about southwest of Honolulu. The island lies almost halfway between Hawaii and Australia and is an Territories of the ...

* Howland Island, a territory of the United States

Territories of the United States are sub-national administrative divisions and dependent territory, dependent territories overseen by the federal government of the United States. The American territories differ from the U.S. states and Indi ...

and a part of the United States Minor Outlying Islands

The United States Minor Outlying Islands is a statistical designation applying to the minor outlying islands and groups of islands that comprise eight United States insular areas in the Pacific Ocean (Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Isla ...

, is an uninhabited coral island located just north of the equator in the central Pacific Ocean, about southwest of Honolulu, Hawaii. The island lies almost halfway between the U. S state of Hawaii and Australia. Its nearest neighbor is Baker Island

Baker Island, once known as New Nantucket in the early 19th century, is a small, uninhabited atoll located just north of the Equator in the central Pacific Ocean, approximately southwest of Honolulu. Positioned almost halfway between Hawaii a ...

, 37 nautical miles (68 kilometers) to the south. Now known as a National Wildlife Refuge

The National Wildlife Refuge System (NWRS) is a system of protected areas of the United States managed by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), an agency within the United States Department of the Interior, Department of the Interi ...

, Howland Island is an insular area

In the law of the United States, an insular area is a U.S.-associated jurisdiction that is not part of a U.S. state or the Washington, D.C., District of Columbia. This includes fourteen Territories of the United States, U.S. territories adminis ...

administered and managed by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service

The United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS or FWS) is a List of federal agencies in the United States, U.S. federal government agency within the United States Department of the Interior which oversees the management of fish, wildlife, ...

. First known as "Worth Island", Howland Island as it later was named, was discovered by U.S. Captain George B. Worth aboard the whaler ''Oena'' in 1822.

1825 Baker Island

Baker Island, once known as New Nantucket in the early 19th century, is a small, uninhabited atoll located just north of the Equator in the central Pacific Ocean, approximately southwest of Honolulu. Positioned almost halfway between Hawaii a ...

* Baker Island, a territory of the United States

Territories of the United States are sub-national administrative divisions and dependent territory, dependent territories overseen by the federal government of the United States. The American territories differ from the U.S. states and Indi ...

and a part of the United States Minor Outlying Islands

The United States Minor Outlying Islands is a statistical designation applying to the minor outlying islands and groups of islands that comprise eight United States insular areas in the Pacific Ocean (Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Isla ...

, is an uninhabited atoll located just north of the equator in the central Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

about southwest of Honolulu, Hawaii

Honolulu ( ; ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, located in the Pacific Ocean. It is the county seat of the Consolidated city-county, consolidated City and County of Honol ...

. The island lies almost halfway between the U.S. state of Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; ) is an island U.S. state, state of the United States, in the Pacific Ocean about southwest of the U.S. mainland. One of the two Non-contiguous United States, non-contiguous U.S. states (along with Alaska), it is the only sta ...

and Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

. Its nearest neighbor is Howland Island

Howland Island () is a coral island and strict nature reserve located just north of the equator in the central Pacific Ocean, about southwest of Honolulu. The island lies almost halfway between Hawaii and Australia and is an Territories of the ...

, 37 nautical miles (68 kilometers) to the north. Now known as a National Wildlife Refuge

The National Wildlife Refuge System (NWRS) is a system of protected areas of the United States managed by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), an agency within the United States Department of the Interior, Department of the Interi ...

, Baker Island is an insular area

In the law of the United States, an insular area is a U.S.-associated jurisdiction that is not part of a U.S. state or the Washington, D.C., District of Columbia. This includes fourteen Territories of the United States, U.S. territories adminis ...

administered and managed by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service

The United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS or FWS) is a List of federal agencies in the United States, U.S. federal government agency within the United States Department of the Interior which oversees the management of fish, wildlife, ...

. According to an article in ''Pacific Magazine'' dated in 2000, Baker island was reportedly first sighted in 1825 by U.S. Captain Obed Starbuck in the ship ''Lopez''. The newly discovered island was named New Nantucket (and also as Phoebe). It was in 1832 that U.S. Captain Michael Baker, after whom the island is now named, also came to the island aboard the whaler ''Gideon Howard''.

1831 Chloroform

Chloroform, or trichloromethane (often abbreviated as TCM), is an organochloride with the formula and a common solvent. It is a volatile, colorless, sweet-smelling, dense liquid produced on a large scale as a precursor to refrigerants and po ...

* Chloroform is a chemical compound in the trihalomethane

In chemistry, trihalomethanes (THMs) are chemical compounds in which three of the four hydrogen atoms of methane () are replaced by halogen atoms. Trihalomethanes with all the same halogen atoms are called haloforms. Many trihalomethanes find uses ...

family that does not undergo combustion in air, although it will burn when mixed with more flammable substances. Chloroform was first discovered in July 1831 by American physician Samuel Guthrie Samuel Guthrie may refer to:

*Samuel Guthrie (politician) (1885–1960), British Columbia CCF MLA

*Samuel Guthrie (physician) (1782–1848), U.S. physician who discovered chloroform

*Samuel Zachary Guthrie, alias Cannonball (comics), Cannonball, a M ...

, independently a few months later by French chemist Eugène Soubeiran and then by German chemist Justus von Liebig

Justus ''Freiherr'' von Liebig (12 May 1803 – 18 April 1873) was a Germans, German scientist who made major contributions to the theory, practice, and pedagogy of chemistry, as well as to agricultural and biology, biological chemistry; he is ...

.

1858 Hadrosaurus foulki

Hadrosaurus was a dubious genus of a hadrosaurid dinosaur that lived near what is now the coast of New Jersey in the late

Hadrosaurus was a dubious genus of a hadrosaurid dinosaur that lived near what is now the coast of New Jersey in the late Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era (geology), Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ...

, around 80 million years ago. It was likely bipedal for the purposes of running, but could use its forelegs to support itself while grazing. Like all hadrosaurids, Hadrosaurus was herbivorous. Its teeth suggest it ate twigs and leaves. In the summer of 1858 while vacationing in Haddonfield, New Jersey, William Parker Foulke

William Parker Foulke (1816–1865) discovered the first full dinosaur skeleton in North America ('' Hadrosaurus foulkii'', which means "Foulke's big lizard") in Haddonfield, New Jersey, in 1858.

Born in Philadelphia, and a descendant of Welsh ...

discovered the world's first nearly-complete skeleton of any species of dinosaur, the Hadrosaurus (named by Joseph Leidy

Joseph Mellick Leidy (September 9, 1823 – April 30, 1891) was an American paleontologist, parasitologist and anatomist.

Leidy was professor of anatomy at the University of Pennsylvania, later becoming a professor of natural history at Swarth ...

), an event that would rock the scientific world and forever change our view of natural history. To this day, Haddonfield, New Jersey is considered to be "ground zero" of dinosaur paleontology.

1859 Midway Atoll

Midway Atoll (colloquialism, colloquial: Midway Islands; ; ) is a atoll in the North Pacific Ocean. Midway Atoll is an insular area of the United States and is an Insular area#Unorganized unincorporated territories, unorganized and unincorpo ...

Midway Atoll, better known as Midway Island or collectively as the Midway islands, is a territory of the United States

Territories of the United States are sub-national administrative divisions and dependent territory, dependent territories overseen by the federal government of the United States. The American territories differ from the U.S. states and Indi ...

and a part of the wider United States Minor Outlying Islands

The United States Minor Outlying Islands is a statistical designation applying to the minor outlying islands and groups of islands that comprise eight United States insular areas in the Pacific Ocean (Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Isla ...

that is located in the North Pacific Ocean

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north'' ...

near the northwestern end of the Hawaiian Islands

The Hawaiian Islands () are an archipelago of eight major volcanic islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the Pacific Ocean, North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the Hawaii (island), island of Hawaii in the south to nort ...

. As a 2.4-square-mile (6.2 km2) atoll, Midway Atoll is one-third of the way between Honolulu, Hawaii

Honolulu ( ; ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, located in the Pacific Ocean. It is the county seat of the Consolidated city-county, consolidated City and County of Honol ...

and Tokyo, Japan

Tokyo, officially the Tokyo Metropolis, is the capital of Japan, capital and List of cities in Japan, most populous city in Japan. With a population of over 14 million in the city proper in 2023, it is List of largest cities, one of the most ...

, approximately 140 nautical miles (259 kilometers) east of the International Date Line

The International Date Line (IDL) is the line extending between the South and North Poles that is the boundary between one calendar day and the next. It passes through the Pacific Ocean, roughly following the 180.0° line of longitude and de ...

, about 2,800 nautical miles (5,200 kilometers) west of San Francisco, California

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

, and 2,200 nautical miles (4,100 kilometers) east of Tokyo, Japan. Midway Atoll consists of a ring-shaped barrier reef and several sand islets. The two significant pieces of land, Sand Island and Eastern Island, provide habitat for millions of seabirds. Because of the importance of marine and biological environment, Midway Atoll is an insular area known as the Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge that is administered and managed by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service

The United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS or FWS) is a List of federal agencies in the United States, U.S. federal government agency within the United States Department of the Interior which oversees the management of fish, wildlife, ...

, an agency of the United States Department of Interior

The United States Department of the Interior (DOI) is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the management and conservation of most federal lands and natural resources. It also administers programs relating t ...

. Midway Atoll is perhaps best known as the site of the Battle of Midway

The Battle of Midway was a major naval battle in the Pacific Ocean theater of World War II, Pacific Theater of World War II that took place on 4–7 June 1942, six months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and one month after the Battle of t ...

, fought in World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

on June 4–6, 1942 and the decisive turning point of the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War or the Pacific Theatre, was the Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II fought between the Empire of Japan and the Allies of World War II, Allies in East Asia, East and Southeast As ...

when the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

defeated an attack by the Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From Japan–Kor ...

. First known as "Middlebrooks Islands", Midway Atoll was discovered by U.S. Captain N.C. Brooks aboard his ship, ''Gambia'', on July 8, 1859.

1859 Petroleum jelly

Petroleum jelly, petrolatum (), white petrolatum, soft paraffin, or multi-hydrocarbon, CAS number 8009-03-8, is a semi-solid mixture of hydrocarbons (with carbon numbers mainly higher than 25), originally promoted as a topical ointment for i ...

Petroleum jelly, petrolatum or soft paraffin is a semi-solid mixture of hydrocarbons originally promoted as a topical ointment for its healing properties. The raw material for petroleum jelly was discovered in 1859 by Robert Chesebrough

Robert Augustus Chesebrough (; January 9, 1837September 8, 1933) was an English-born American chemist who discovered petroleum jelly—which he marketed as Vaseline—and founder of the Chesebrough Manufacturing Company.

Life and career

Bor ...

, a chemist from New York. In 1870, this product was branded as Vaseline Petroleum Jelly.

1873 Chemical potential

In thermodynamics, the chemical potential of a Chemical specie, species is the energy that can be absorbed or released due to a change of the particle number of the given species, e.g. in a chemical reaction or phase transition. The chemical potent ...

* The chemical potential, symbolized by μ, is a thermodynamic

Thermodynamics is a branch of physics that deals with heat, work, and temperature, and their relation to energy, entropy, and the physical properties of matter and radiation. The behavior of these quantities is governed by the four laws of th ...

concept developed by the American scientist Josiah Willard Gibbs

Josiah Willard Gibbs (; February 11, 1839 – April 28, 1903) was an American mechanical engineer and scientist who made fundamental theoretical contributions to physics, chemistry, and mathematics. His work on the applications of thermodynami ...

in his 1873 paper ''A Method of Geometrical Representation of the Thermodynamic Properties of Substances by Means of Surfaces. '' Gibbs's work had an enormous impact on the development of modern physical chemistry

Physical chemistry is the study of macroscopic and microscopic phenomena in chemical systems in terms of the principles, practices, and concepts of physics such as motion, energy, force, time, thermodynamics, quantum chemistry, statistical mech ...

.

1875 Red Delicious

Red Delicious is a variety of apple with a red exterior and sweet taste. Known as "the Reds" in the industry, this variety is the result of a chance seedling. It was first recognized in Madison County, Iowa, in 1872. Despite its name, it is not r ...

The Red Delicious is a clone of

The Red Delicious is a clone of apple

An apple is a round, edible fruit produced by an apple tree (''Malus'' spp.). Fruit trees of the orchard or domestic apple (''Malus domestica''), the most widely grown in the genus, are agriculture, cultivated worldwide. The tree originated ...

cultigen

A cultigen (), or cultivated plant, is a plant that has been deliberately altered or selected by humans, by means of genetic modification, graft-chimaeras, plant breeding, or wild or cultivated plant selection. These plants have commercial val ...

, now comprising more than 50 cultivars

A cultivar is a kind of cultivated plant that people have selected for desired traits and which retains those traits when propagated. Methods used to propagate cultivars include division, root and stem cuttings, offsets, grafting, tissue cult ...

. The Red Delicious apple was discovered in 1875 by Jesse Hiatt on his farm in Peru, Iowa. Believing that the seedling was nothing more than nuisance. After chopping down the tree three times, Hiatt decided to let the tree grow and eventually, it produced an unknown and new harvest of red apples. Hiatt would eventually sell the rights to this type of apple to the Stark Brothers Nurseries and Orchards who renamed it the Red Delicious.

1877 Deimos

Deimos is the smaller and outer of Mars' two moons. It was discovered by Asaph Hall

Asaph Hall III (October 15, 1829 – November 22, 1907) was an American astronomer who is best known for having discovered the two moons of Mars, Deimos and Phobos, in 1877. He determined the orbits of satellites of other planets and of doubl ...

in 1877.

1877 Phobos

Phobos is the larger and closer of Mars' two small moons. It was discovered by Asaph Hall

Asaph Hall III (October 15, 1829 – November 22, 1907) was an American astronomer who is best known for having discovered the two moons of Mars, Deimos and Phobos, in 1877. He determined the orbits of satellites of other planets and of doubl ...

in 1877.

1888 Cliff Palace

The Cliff Palace is the largest cliff dwelling in North America. The structure built by the Ancestral Puebloans

The Ancestral Puebloans, also known as Ancestral Pueblo peoples or the Basketmaker-Pueblo culture, were an ancient Native American culture of Pueblo peoples spanning the present-day Four Corners region of the United States, comprising southe ...

is located in Mesa Verde National Park

Mesa Verde National Park is a national park of the United States and UNESCO World Heritage Site located in Montezuma County, Colorado, and the only World Heritage Site in Colorado. The park protects some of the best-preserved Ancestral Puebloa ...

in their former homeland region. The cliff dwelling and park are in the southwestern corner of Colorado

Colorado is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States. It is one of the Mountain states, sharing the Four Corners region with Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. It is also bordered by Wyoming to the north, Nebraska to the northeast, Kansas ...

, in the Southwestern United States

The Southwestern United States, also known as the American Southwest or simply the Southwest, is a geographic and cultural list of regions of the United States, region of the United States that includes Arizona and New Mexico, along with adjacen ...

. The ancient ruins of Cliff Palace were co-discovered during a snowstorm in December 1888 by Richard Wetherill and Charlie Mason who were searching for stray cattle on Chapin Mesa.

1889 Torosaurus

''Torosaurus'' (meaning "perforated lizard", in reference to the large openings in its frill) is a genus of herbivorous Chasmosaurinae, chasmosaurine Ceratopsia, ceratopsian dinosaur that lived during the late Maastrichtian age of the Late Cret ...

Torosaurus was a herbivorous dinosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous Period about 70 million years ago in what is now North America. Torosaurus had an enormous head that measured in length. Its skull is one of the largest known up to date, no other land animal has ever had a skull larger than Torosaurus. Torosaurus frill made up about one-half the total skull length. The first fossils of Torosaurus were discovered in 1889, in Wyoming by John Bell Hatcher. The American paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh

Othniel Charles Marsh (October 29, 1831 – March 18, 1899) was an American professor of paleontology. A prolific fossil collector, Marsh was one of the preeminent paleontologists of the nineteenth century. Among his legacies are the discovery or ...

would later name the specimen ''Torosaurus latus'', in recognition of the bull-like size of its skull and its large eyebrow horns. Ever since, the specimen has been in display at the Peabody Museum in New Haven, Connecticut.

1891 Thescelosaurus

''Thescelosaurus'' ( ) is a genus of Ornithischia, ornithischian dinosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous period (geology), period in western North America. It was named and described in 1913 by the Paleontology, paleontologist Charles W. G ...

Thescelosaurus was a bipedal dinosaur with a sturdy build, small wide hands, and a long pointed snout from the Late Cretaceous Period, approximately 66 million years ago. As a herbivore, Thescelosaurus was not a tall dinosaur and probably browsed the ground selectively to find food. Its leg structure and proportionally heavy build suggests that it was not a fast runner like other dinosaurs. The first fossils of Thescelosaurus were co-discovered in 1891 by John Bell Hatcher and William H. Utterback, in Wyoming. However, this discovery remained stored until Charles W. Gilmore named the dinosaur in 1913.

1892 Amalthea

Amalthea is the third moon of Jupiter in order of distance from the planet. It was discovered on September 9, 1892, by

Thescelosaurus was a bipedal dinosaur with a sturdy build, small wide hands, and a long pointed snout from the Late Cretaceous Period, approximately 66 million years ago. As a herbivore, Thescelosaurus was not a tall dinosaur and probably browsed the ground selectively to find food. Its leg structure and proportionally heavy build suggests that it was not a fast runner like other dinosaurs. The first fossils of Thescelosaurus were co-discovered in 1891 by John Bell Hatcher and William H. Utterback, in Wyoming. However, this discovery remained stored until Charles W. Gilmore named the dinosaur in 1913.

1892 Amalthea

Amalthea is the third moon of Jupiter in order of distance from the planet. It was discovered on September 9, 1892, by Edward Emerson Barnard

Edward Emerson Barnard (December 16, 1857 – February 6, 1923) was an American astronomer. He was commonly known as E. E. Barnard, and was recognized as a gifted observational astronomer. He is best known for his discovery of the high proper m ...

.

1899 Phoebe

* Phoebe is an irregular satellite of Saturn. It was discovered by William Henry Pickering

William Henry Pickering (February 15, 1858 – January 16, 1938) was an American astronomer. Pickering constructed and established several observatories or astronomical observation stations, notably including Percival Lowell's Flagstaff Obser ...

on March 17, 1899, from photographic plates that had been taken starting on August 16, 1898, at Arequipa, Peru by DeLisle Stewart.

Twentieth century

1902Tyrannosaurus

''Tyrannosaurus'' () is a genus of large theropod dinosaur. The type species ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' ( meaning 'king' in Latin), often shortened to ''T. rex'' or colloquially t-rex, is one of the best represented theropods. It lived througho ...

Tyrannosaurus, a bipedal carnivore, is a genus of theropod dinosaur. The species Tyrannosaurus rex, commonly abbreviated to T. rex, is a fixture in popular culture. It lived throughout what is now western North America, with a much wider range than other tyrannosaurids. Fossils are found in a variety of rock formations dating to the last two million years of the

Tyrannosaurus, a bipedal carnivore, is a genus of theropod dinosaur. The species Tyrannosaurus rex, commonly abbreviated to T. rex, is a fixture in popular culture. It lived throughout what is now western North America, with a much wider range than other tyrannosaurids. Fossils are found in a variety of rock formations dating to the last two million years of the Cretaceous Period

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ninth and longest geologi ...

, 67 to 66 million years ago. It was among the last non-avian dinosaurs to exist prior to the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction event. In 1902, the first skeleton of Tyrannosaurus was discovered in Hell Creek, Montana by American paleontologist Barnum Brown

Barnum Brown (February 12, 1873 – February 5, 1963), commonly referred to as Mr. Bones, was an American paleontologist. He discovered the first documented remains of ''Tyrannosaurus'' during a career that made him one of the most famous fossil ...

. In 1908, Brown discovered a better preserved skeleton of Tyrannosaurus.

1908 Seyfert galaxies

* Seyfert galaxies are a class of galaxies with nuclei that produce spectral line emission from highly ionized gas, named after Carl Keenan Seyfert, the astronomer who first identified the class in 1943 although they were first discovered by Edward A. Fath in 1908 while he was at the Lick Observatory

The Lick Observatory is an astronomical observatory owned and operated by the University of California. It is on the summit of Mount Hamilton (California), Mount Hamilton, in the Diablo Range just east of San Jose, California, United States. The ...

.

1909 Burgess shale

The Burgess Shale is a fossil-bearing deposit exposed in the Canadian Rockies of British Columbia, Canada. It is famous for the exceptional preservation of the soft parts of its fossils. At old (middle Cambrian), it is one of the earliest fos ...

The formation of Burgess shale — located in the Canadian Rockies

The Canadian Rockies () or Canadian Rocky Mountains, comprising both the Alberta Rockies and the British Columbian Rockies, is the Canadian segment of the North American Rocky Mountains. It is the easternmost part of the Canadian Cordillera, w ...

of British Columbia

British Columbia is the westernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Situated in the Pacific Northwest between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains, the province has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that ...

— is one of the world's most celebrated fossil fields, and the best of its kind. It is famous for the exceptional preservation of the soft parts of its fossils. It is (Middle Cambrian

The Cambrian ( ) is the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 51.95 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran period 538.8 Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Ordov ...

) old, one of the earliest soft-parts fossil beds. The rock unit is a black shale

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of Clay mineral, clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g., Kaolinite, kaolin, aluminium, Al2Silicon, Si2Oxygen, O5(hydroxide, OH)4) and tiny f ...

, and crops out at a number of localities near the town of Field, British Columbia

Field is an unincorporated community of approximately 169 people located in the Kicking Horse River valley of southeastern British Columbia,

Canada, within the confines of Yoho National Park. At an elevation of , it is west of Lake Louise a ...

in the Yoho National Park

Yoho National Park ( ) is a National Parks of Canada, national park of Canada. It is located within the Canadian Rockies, Rocky Mountains along the western slope of the Continental Divide of the Americas in southeastern British Columbia, bordere ...

. The Burgess Shale was discovered by American palaeontologist Charles Doolittle Walcott

Charles Doolittle Walcott (March 31, 1850February 9, 1927) was an American paleontologist, administrator of the Smithsonian Institution from 1907 to 1927, and director of the United States Geological Survey. He is famous for his discovery in 19 ...

in 1909, towards the end of the season's fieldwork. He returned in 1910 with his sons, establishing a quarry on the flanks of Fossil Ridge. The significance of soft-bodied preservation, and the range of organisms he recognized as new to science, led him to return to the quarry almost every year until 1924. At this point, aged 74, he had amassed over 65,000 specimens. Describing the fossils was a vast task, pursued by Walcott until his death in 1927.

1910 Propane

Propane () is a three-carbon chain alkane with the molecular formula . It is a gas at standard temperature and pressure, but becomes liquid when compressed for transportation and storage. A by-product of natural gas processing and petroleum ref ...

* Propane is a three-carbon alkane

In organic chemistry, an alkane, or paraffin (a historical trivial name that also has other meanings), is an acyclic saturated hydrocarbon. In other words, an alkane consists of hydrogen and carbon atoms arranged in a tree structure in whi ...

, normally a gas, but compressible to a transportable liquid. It is derived from other petroleum

Petroleum, also known as crude oil or simply oil, is a naturally occurring, yellowish-black liquid chemical mixture found in geological formations, consisting mainly of hydrocarbons. The term ''petroleum'' refers both to naturally occurring un ...

products during oil or natural gas processing. It is commonly used as a fuel for engines, barbecues, portable stoves, and residential central heating. Propane was first identified as a volatile component in gasoline by Dr. Walter O. Snelling of the U.S. Bureau of Mines in 1910.

1912 Golden Delicious

Golden Delicious is a cultivar of apple. It is one of the 15 most popular apple cultivars in the United States. It is not closely related to Red Delicious.

History

Golden Delicious arose from a chance seedling, possibly a hybrid of Grimes ...

Golden Delicious is a large, yellow skinned cultivar of apple and very sweet to the taste. The original Golden Delicious tree is thought to have been discovered by Anderson Mullins on a hill near Porter Creek in Clay County, West Virginia. The Stark Brothers Nursery soon purchased the tree which spawned a leading cultivar in the United States and abroad. The Golden Delicious is the state fruit of West Virginia.

1912 Smoking-cancer link

* Dr. Isaac Adler was the first to strongly suggest that lung cancer is related to smoking in 1912.

1914 Sinope

* Sinope is a retrograde irregular satellite of Jupiter discovered by Seth Barnes Nicholson at

Golden Delicious is a large, yellow skinned cultivar of apple and very sweet to the taste. The original Golden Delicious tree is thought to have been discovered by Anderson Mullins on a hill near Porter Creek in Clay County, West Virginia. The Stark Brothers Nursery soon purchased the tree which spawned a leading cultivar in the United States and abroad. The Golden Delicious is the state fruit of West Virginia.

1912 Smoking-cancer link

* Dr. Isaac Adler was the first to strongly suggest that lung cancer is related to smoking in 1912.

1914 Sinope

* Sinope is a retrograde irregular satellite of Jupiter discovered by Seth Barnes Nicholson at Lick Observatory

The Lick Observatory is an astronomical observatory owned and operated by the University of California. It is on the summit of Mount Hamilton (California), Mount Hamilton, in the Diablo Range just east of San Jose, California, United States. The ...

in 1914.

1915 Zener diode

A Zener diode is a type of diode designed to exploit the Zener effect to affect electric current to flow against the normal direction from anode to cathode, when the voltage across its terminals exceeds a certain characteristic threshold, the ''Z ...

s

* A Zener diode is a type of diode that permits current in the forward direction like a normal diode, but also in the reverse direction if the voltage is larger than the breakdown voltage

The breakdown voltage of an insulator (electrical), insulator is the minimum voltage that causes a portion of an insulator to experience electrical breakdown and become electrically Conductor (material), conductive.

For diodes, the breakdown vo ...

known as "Zener knee voltage" or "Zener voltage". The device was named after Clarence Zener

Clarence Melvin Zener ( ; December 1, 1905 – July 2, 1993) was an American physicist who in 1934 was the first to describe the property concerning the breakdown of electrical insulators. These findings were later exploited by Bell Labs in the ...

, who discovered this electrical property.

1916 Barnard's Star

Barnard's Star is a small red dwarf star in the constellation of Ophiuchus. At a distance of from Earth, it is the fourth-nearest-known individual star to the Sun after the three components of the Alpha Centauri system, and is the c ...

* Barnard's Star is a very low-mass red dwarf star. At a distance of about 1.8 parsecs from the Solar System

The Solar SystemCapitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Sola ...

, or just under six light-years, Barnard's Star is the nearest-known star in the constellation Ophiuchus

Ophiuchus () is a large constellation straddling the celestial equator. Its name comes from the Ancient Greek (), meaning "serpent-bearer", and it is commonly represented as a man grasping a snake. The serpent is represented by the constellati ...

, and the fourth-closest known individual star to the Sun, after the three components of the Alpha Centauri

Alpha Centauri (, α Cen, or Alpha Cen) is a star system in the southern constellation of Centaurus (constellation), Centaurus. It consists of three stars: Rigil Kentaurus (), Toliman (), and Proxima Centauri (). Proxima Centauri ...

system. In 1916, Barnard's Star was discovered by American astronomer Edward Emerson Barnard

Edward Emerson Barnard (December 16, 1857 – February 6, 1923) was an American astronomer. He was commonly known as E. E. Barnard, and was recognized as a gifted observational astronomer. He is best known for his discovery of the high proper m ...

, whom the star was named after.

1916 Covalent bond

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electrons to form electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs. The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atom ...

ing

* The idea of covalent bonding can be traced several years to Gilbert N. Lewis

Gilbert Newton Lewis (October 23 or October 25, 1875 – March 23, 1946) was an American physical chemist and a dean of the college of chemistry at University of California, Berkeley. Lewis was best known for his discovery of the covalent bon ...

, who in 1916 described the sharing of electron pairs between atoms. He introduced the so-called Lewis notation or electron dot notation or The Lewis Dot Structure in which valence electrons are represented as dots around the atomic symbols.

1916 Heparin

Heparin, also known as unfractionated heparin (UFH), is a medication and naturally occurring glycosaminoglycan. Heparin is a blood anticoagulant that increases the activity of antithrombin. It is used in the treatment of myocardial infarction, ...

* Heparin, a highly sulfated glycosaminoglycan

Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) or mucopolysaccharides are long, linear polysaccharides consisting of repeating disaccharide units (i.e. two-sugar units). The repeating two-sugar unit consists of a uronic sugar and an amino sugar, except in the case o ...

, is widely used as an injectable anticoagulant and has the highest negative charge density of any known biological molecule. It can also be used to form an inner anticoagulant surface on various experimental and medical devices such as test tubes and renal dialysis machines. It was discovered by Jay McLean and William Henry Howell

William Henry Howell (February 20, 1860 – February 6, 1945) was an American physiologist. He pioneered the use of heparin as a blood anti-coagulant.

Early life

William Henry Howell was born on February 20, 1860, in Baltimore, Maryland. He gra ...

in 1916.

1917 Vitamin A

Vitamin A is a fat-soluble vitamin that is an essential nutrient. The term "vitamin A" encompasses a group of chemically related organic compounds that includes retinol, retinyl esters, and several provitamin (precursor) carotenoids, most not ...

* Vitamin A, a bi-polar molecule formed with bi-polar covalent bonds between carbon and hydrogen, is linked to a family of similarly shaped molecules, the retinoids, which complete the remainder of the vitamin sequence. Its important part is the retinyl group, which can be found in several forms. In foods of animal origin, the major form of vitamin A is an ester, primarily retinyl palmitate, which is converted to an alcohol in the small intestine. Vitamin A can also exist as an aldehyde, or as an acid. The discovery of vitamin A stemmed from research dating back to 1906, indicating that factors other than carbohydrates, proteins, and fats were necessary to keep cattle healthy. By 1917 one of these substances was independently discovered by Elmer McCollum

Elmer Verner McCollum (March 3, 1879 – November 15, 1967) was an American biochemist known for his work on the influence of diet on health.Kruse, 1961. McCollum is also remembered for starting the first rat colony in the United States to be us ...

at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, and Lafayette Mendel and Thomas Osborne at Yale University.

1923 Oviraptor

* Oviraptor is a genus of small Mongolian theropod dinosaur that lived during the late Campanian stage about 75 million years ago. In 1923, Roy Chapman Andrews

Roy Chapman Andrews (January 26, 1884 – March 11, 1960) was an American explorer, adventurer, and Natural history, naturalist who became the director of the American Museum of Natural History. He led a series of expeditions through the politi ...

discovered the first and so far the only fossils of Oviraptor to ever be found at the Djadochta Formation in Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of China. Its border includes two-thirds of the length of China's China–Mongolia border, border with the country of Mongolia. ...

. This species of dinosaur was named and described by Henry Fairfield Osborn

Henry Fairfield Osborn, Sr. (August 8, 1857 – November 6, 1935) was an American paleontologist, geologist and eugenics advocate. He was professor of anatomy at Columbia University, president of the American Museum of Natural History for 25 y ...

in 1924.

1924 Uncle Sam Diamond

* Uncle Sam is a 40.23-carat white diamond, the largest diamond ever found in North America. Discovered in 1924 at the Crater of Diamonds State Park

Crater of Diamonds State Park is a List of Arkansas state parks, Arkansas state park in Pike County, Arkansas, Pike County, Arkansas, in the United States. The park features a plowed field, one of the few diamond-bearing sites accessible to th ...

in Arkansas, the diamond was named after its discoverer, Wesley Oley Basham, who went by the nickname "Uncle Sam". Over the years, the Uncle Sam diamond was cut twice with the second cutting resulting in a 12.42-carat, emerald-cut gem.

1925 Cepheid variables

* Extragalactic astronomy is the branch of astronomy concerned with objects outside the Milky Way Galaxy. In other words, it is the study of all astronomical objects which are not covered by galactic astronomy. It was started by Edwin Hubble

Edwin Powell Hubble (November 20, 1889 – September 28, 1953) was an American astronomer. He played a crucial role in establishing the fields of extragalactic astronomy and observational cosmology.

Hubble proved that many objects previously ...

when, in 1925, he discovered the existence of Cepheid variable

A Cepheid variable () is a type of variable star that pulsates radially, varying in both diameter and temperature. It changes in brightness, with a well-defined stable period (typically 1–100 days) and amplitude. Cepheids are important cosmi ...

s in the Andromeda Galaxy. This discovery proved the existence of a galaxy over one million light-years away and thus extragalactic astronomy was created.Alt URL/ref> 1927

Electron diffraction

Electron diffraction is a generic term for phenomena associated with changes in the direction of electron beams due to elastic interactions with atoms. It occurs due to elastic scattering, when there is no change in the energy of the electrons. ...

* Electron diffraction is a collective scattering phenomenon with electrons being scattered by atoms in a regular crystal array. This can be understood in analogy to the Huygens principle for the diffraction of light. The incoming plane electron wave interacts with the atoms, and secondary waves are generated which interfere with each other. In 1927, two Americans named Clinton Davisson

Clinton Joseph Davisson (October 22, 1881 – February 1, 1958) was an American physicist who shared the 1937 Nobel Prize in Physics with George Paget Thomson "for their experimental discovery of the diffraction of electrons by crystals".

Earl ...

and Lester Germer

Lester Halbert Germer (October 10, 1896 – October 3, 1971) was an American physicist. With Clinton Davisson, he proved the wave-particle duality of matter in the Davisson–Germer experiment, which was important to the development of the e ...

had proven de Broglie's theory by discovering electron diffraction. This confirmation of the wavelike nature of an electron was discovered independently of Englishman George Paget Thomson

Sir George Paget Thomson (; 3 May 1892 – 10 September 1975) was an English physicist who shared the 1937 Nobel Prize in Physics with Clinton Davisson “for their experimental discovery of the diffraction of electrons by crystals”.

Educa ...

.

1928 Jones Diamond The Jones Diamond, also known as the Punch Jones Diamond, The Grover Jones Diamond, or The Horseshoe Diamond, was a 34.48 carat (6.896 g) alluvial diamond found in Peterstown, West Virginia by members of the Jones family. It remains the largest all ...

* The Jones Diamond is a bluish-white diamond weighing 34.48 carats (6.896 g), measuring 5/8 of an inch (15.8 mm) across, and possessing 12 diamond-shaped faces. It is considered to be the largest alluvial diamond from North America. The Jones Diamond was discovered by William P. "Punch" Jones and his father Grover while pitching horseshoes in 1928. They thought the stone was a piece of quartz which was common in the area. Keeping it in a cigar box in their tool shed for 14 years, the Jones's sent the gem to the geology department at Virginia Polytechnic Institute

The Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, commonly referred to as Virginia Tech (VT), is a Public university, public Land-grant college, land-grant research university with its main campus in Blacksburg, Virginia, United States ...

in 1942 where they were informed that it was an alluvial diamond and not a quartz crystal. The diamond was then sent to the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

in Washington D.C. for safekeeping until 1964, when it returned to the Jones family who kept it for another 20 years in a safe deposit box at their local bank in Virginia. In 1984, the Jones family finally sold the diamond at Sotheby's

Sotheby's ( ) is a British-founded multinational corporation with headquarters in New York City. It is one of the world's largest brokers of fine art, fine and decorative art, jewellery, and collectibles. It has 80 locations in 40 countries, an ...

auction in New York City to a private collector of jewelry.

1930 Pluto

Pluto (minor-planet designation: 134340 Pluto) is a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, a ring of Trans-Neptunian object, bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune. It is the ninth-largest and tenth-most-massive known object to directly orbit the Su ...

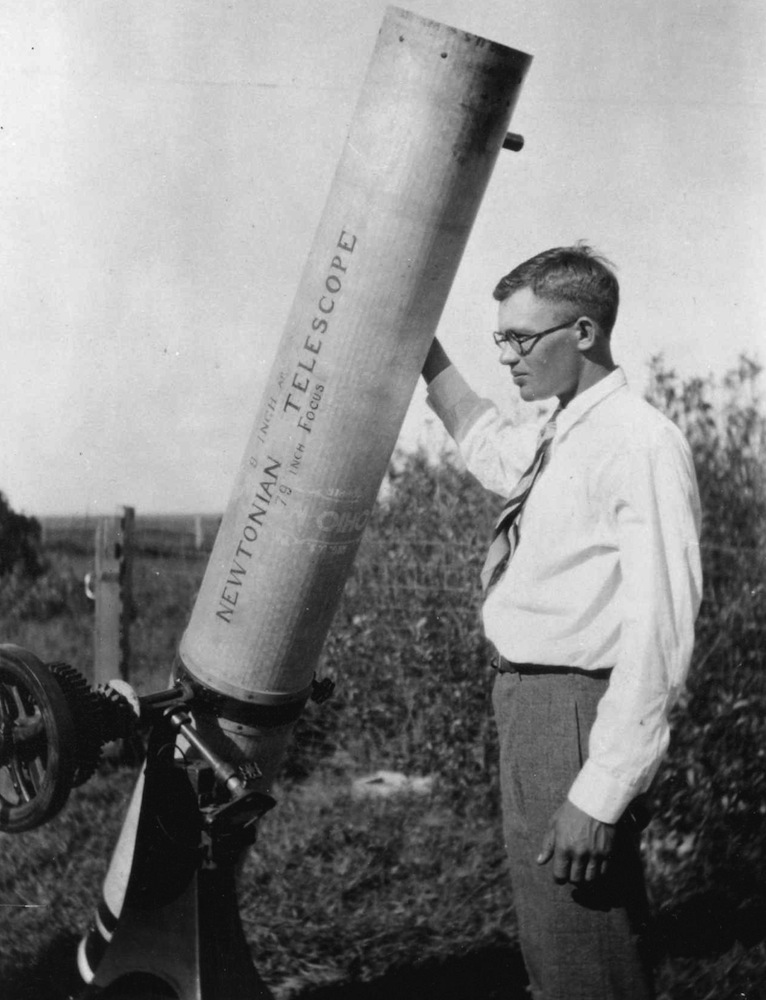

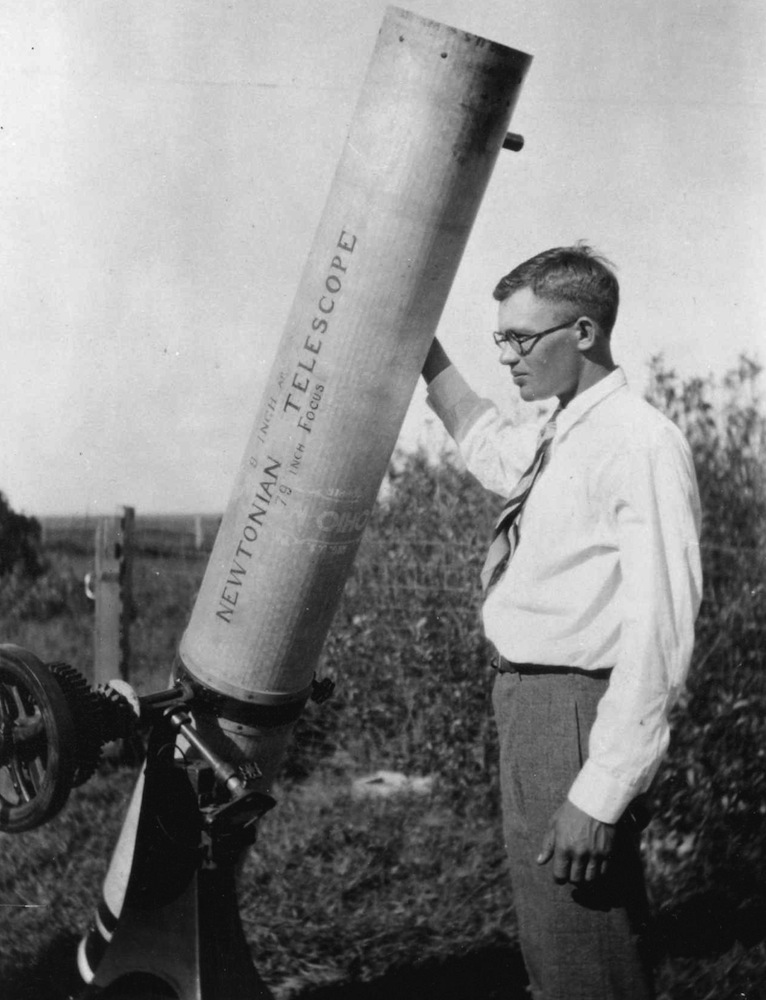

Following the discovery of the planet Neptune in 1846, there was considerable speculation that another planet might exist beyond its orbit. The search began in the mid-19th century but culminated at the start of the 20th century with a quest for Planet X.

Following the discovery of the planet Neptune in 1846, there was considerable speculation that another planet might exist beyond its orbit. The search began in the mid-19th century but culminated at the start of the 20th century with a quest for Planet X. Percival Lowell

Percival Lowell (; March 13, 1855 – November 12, 1916) was an American businessman, author, mathematician, and astronomer who fueled speculation that there were canals on Mars, and furthered theories of a ninth planet within the Solar System ...

proposed the Planet X hypothesis to explain apparent discrepancies in the orbits of the gas giants, particularly Uranus and Neptune, speculating that the gravity of a large unseen planet could have perturbed Uranus enough to account for the irregularities. The discovery of Pluto by Clyde Tombaugh

Clyde William Tombaugh (; February 4, 1906 – January 17, 1997) was an American astronomer best known for discovering Pluto, the first object to be identified in what would later be recognized as the Kuiper belt, in 1930.

Raised on farms in ...

in 1930 initially appeared to validate Lowell's hypothesis, and Pluto

Pluto (minor-planet designation: 134340 Pluto) is a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, a ring of Trans-Neptunian object, bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune. It is the ninth-largest and tenth-most-massive known object to directly orbit the Su ...