, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''

Plus ultra'' (

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

)

(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem =

(English: "Royal March")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital =

Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

, coordinates =

, largest_city =

Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

, languages_type = Official language

, languages =

Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

, ethnic_groups =

, ethnic_groups_year =

, ethnic_groups_ref =

, religion =

, religion_ref =

, religion_year = 2020

, demonym =

, government_type =

Unitary

Unitary may refer to:

Mathematics

* Unitary divisor

* Unitary element

* Unitary group

* Unitary matrix

* Unitary morphism

* Unitary operator

* Unitary transformation

* Unitary representation In mathematics, a unitary representation of a grou ...

parliamentary

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

, leader_title1 =

Monarch

A monarch is a head of stateWebster's II New College DictionarMonarch Houghton Mifflin. Boston. 2001. p. 707. Life tenure, for life or until abdication, and therefore the head of state of a monarchy. A monarch may exercise the highest authority ...

, leader_name1 =

Felipe VI

Felipe VI (;,

* eu, Felipe VI.a,

* ca, Felip VI,

* gl, Filipe VI, . Felipe Juan Pablo Alfonso de Todos los Santos de Borbón y Grecia; born 30 January 1968) is King of Spain. He is the son of former King Juan Carlos I and Queen Sofía, an ...

, leader_title2 =

Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

, leader_name2 =

Pedro Sánchez

Pedro Sánchez Pérez-Castejón (; born 29 February 1972) is a Spanish politician who has been Prime Minister of Spain since June 2018. He has also been Secretary-General of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) since June 2017, having p ...

, legislature =

Cortes Generales

The Cortes Generales (; en, Spanish Parliament, lit=General Courts) are the bicameral legislative chambers of Spain, consisting of the Congress of Deputies (the lower house), and the Senate (the upper house).

The Congress of Deputies m ...

, upper_house =

Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, lower_house =

Congress of Deputies

The Congress of Deputies ( es, link=no, Congreso de los Diputados, italic=unset) is the lower house of the Cortes Generales, Spain's legislative branch. The Congress meets in the Palacio de las Cortes, Madrid, Palace of the Parliament () in Ma ...

, sovereignty_type =

Formation

Formation may refer to:

Linguistics

* Back-formation, the process of creating a new lexeme by removing or affixes

* Word formation, the creation of a new word by adding affixes

Mathematics and science

* Cave formation or speleothem, a secondar ...

, established_event1 =

''De facto''

, established_date1 = 20 January 1479

, established_event2 = ''

De jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legall ...

''

, established_date2 = 9 June 1715

, established_event3 =

First constitution

, established_date3 = 19 March 1812

, established_event4 =

, established_date4 = 29 December 1978

, established_event5 =

, established_date5 = 1 January 1986

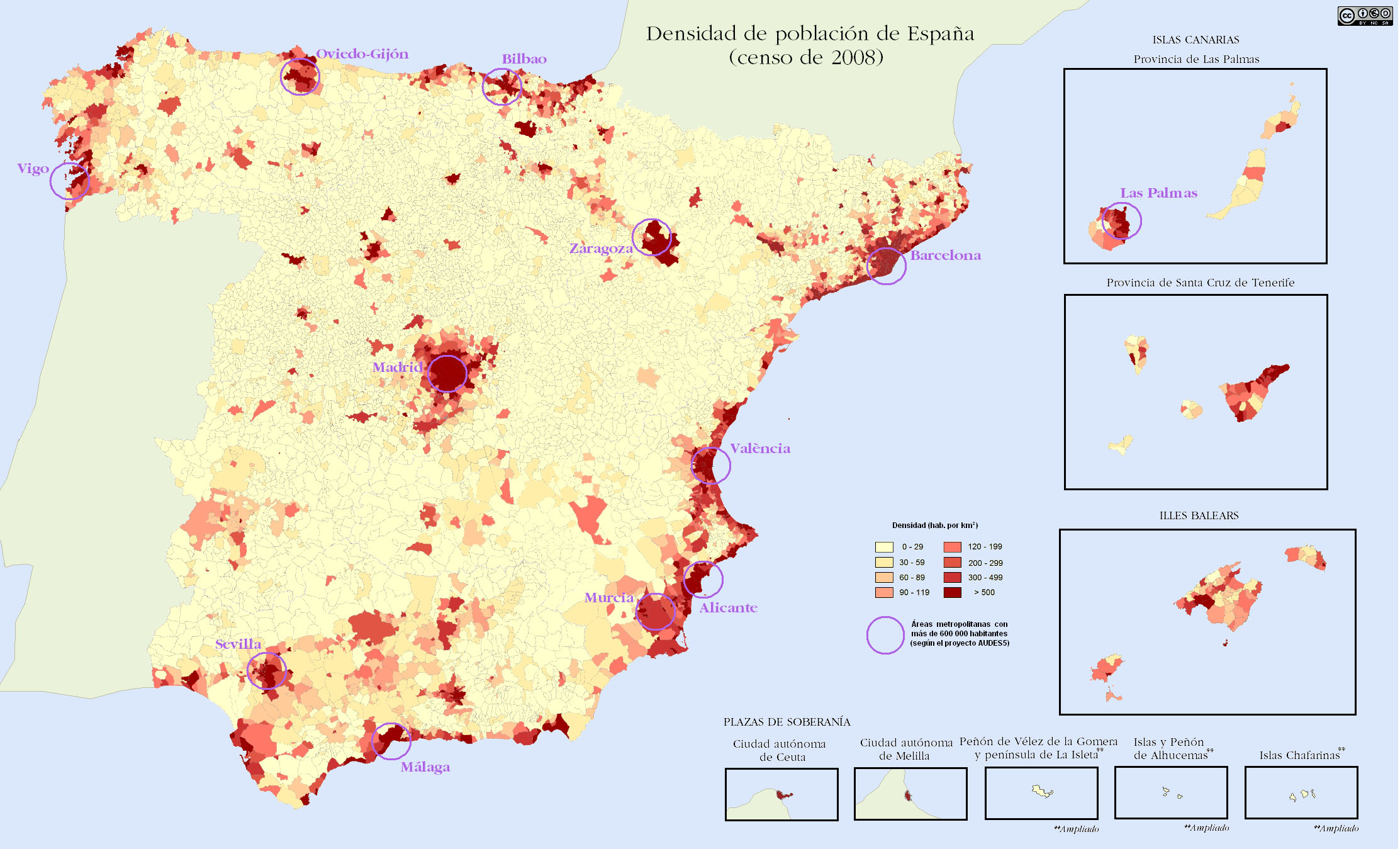

, area_km2 = 505,990

, area_rank = 51st

, area_sq_mi = 195,364

, percent_water = 0.89 (2015)

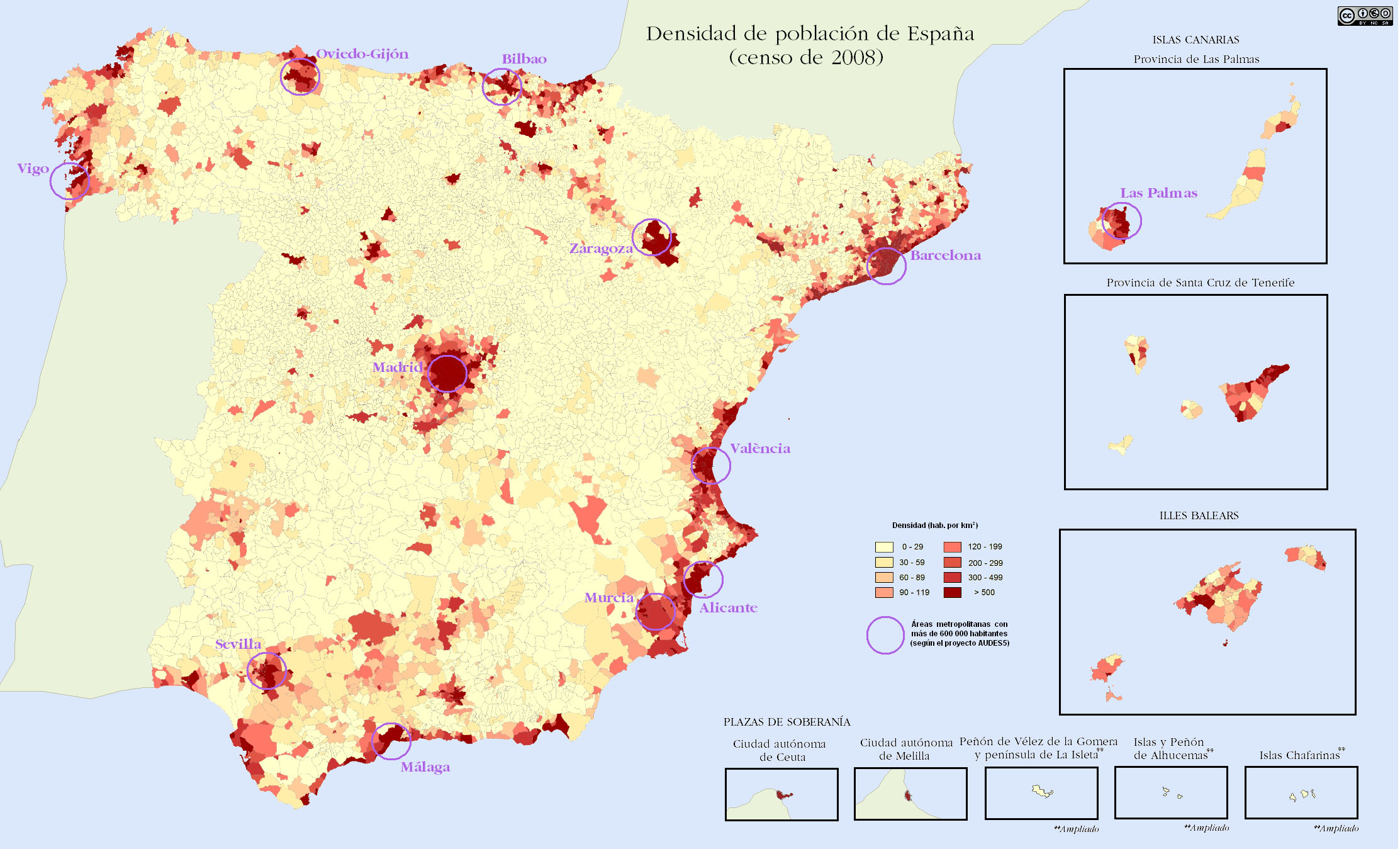

, population_estimate = 47,163,418

, population_estimate_year = 2022

, population_estimate_rank = 31st

, population_density_km2 = 94

, population_density_sq_mi = 243

, population_density_rank = 120th

, GDP_PPP =

, GDP_PPP_year = 2022

, GDP_PPP_rank = 16th

, GDP_PPP_per_capita = $46,511

, GDP_PPP_per_capita_rank = 37th

, GDP_nominal =

, GDP_nominal_year = 2022

, GDP_nominal_rank = 16th

, GDP_nominal_per_capita = $29,198

, GDP_nominal_per_capita_rank = 40th

, Gini = 33.0

, Gini_year = 2021

, Gini_change = increase

, Gini_ref =

, Gini_rank =

, HDI = 0.905

, HDI_year = 2021

, HDI_change = increase

, HDI_ref =

, HDI_rank = 27th

, currency =

Euro

The euro ( symbol: €; code: EUR) is the official currency of 19 out of the member states of the European Union (EU). This group of states is known as the eurozone or, officially, the euro area, and includes about 340 million citizens . ...

(

€

The euro sign () is the currency sign used for the euro, the official currency of the eurozone and unilaterally adopted by Kosovo and Montenegro. The design was presented to the public by the European Commission on 12 December 1996. It consists o ...

)

, currency_code = EUR

, time_zone =

WET and

CET

, utc_offset = ±0 to +1

, DST_note = Note: most of Spain observes CET/CEST, except the

Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, :es:Canarias, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to ...

which observe WET/WEST.

, time_zone_DST =

WEST

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some ...

and

CEST

, utc_offset_DST = +1 to +2

, date_format = // (

CE)

, drives_on = right

, calling_code =

+34

, iso3166code = ES

, cctld =

.es

.es (espana) is the country code top-level domain (ccTLD) for Spain. It is administered by the Network Information Centre of Spain.

Registrations are permitted at the second level or at the third level beneath various generic second level categ ...

, today =

Spain ( es, España, links=no, ), or the Kingdom of Spain (), is a country primarily located in southwestern

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

with parts of territory in the

Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

and across the

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

.

The largest part of Spain is situated on the

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

; its territory also includes the

Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, :es:Canarias, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to ...

in the Atlantic Ocean, the

Balearic Islands

The Balearic Islands ( es, Islas Baleares ; or ca, Illes Balears ) are an archipelago in the Balearic Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The archipelago is an autonomous community and a province of Spain; its capital is ...

in the Mediterranean Sea, and the

autonomous cities of

Ceuta

Ceuta (, , ; ar, سَبْتَة, Sabtah) is a Spanish autonomous city on the north coast of Africa.

Bordered by Morocco, it lies along the boundary between the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. It is one of several Spanish territori ...

and

Melilla

Melilla ( , ; ; rif, Mřič ; ar, مليلية ) is an autonomous city of Spain located in north Africa. It lies on the eastern side of the Cape Three Forks, bordering Morocco and facing the Mediterranean Sea. It has an area of . It was pa ...

in Africa. The country's mainland is bordered to the south by

Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = "Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gibr ...

; to the south and east by the Mediterranean Sea; to the north by

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

,

Andorra

, image_flag = Flag of Andorra.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Andorra.svg

, symbol_type = Coat of arms

, national_motto = la, Virtus Unita Fortior, label=none (Latin)"United virtue is stro ...

and the

Bay of Biscay

The Bay of Biscay (), known in Spain as the Gulf of Biscay ( es, Golfo de Vizcaya, eu, Bizkaiko Golkoa), and in France and some border regions as the Gulf of Gascony (french: Golfe de Gascogne, oc, Golf de Gasconha, br, Pleg-mor Gwaskogn), ...

; and to the west by

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of th ...

and the Atlantic Ocean. With an area of , Spain is the second-largest country in the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

(EU) and, with a population exceeding 47.4 million, the

fourth-most populous EU member state. Spain's capital and largest city is

Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

; other major

urban areas

An urban area, built-up area or urban agglomeration is a human settlement with a high population density and infrastructure of built environment. Urban areas are created through urbanization and are categorized by urban morphology as cities, ...

include

Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

,

Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. The wider urban area al ...

,

Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Penins ...

,

Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Province of Zaragoza, Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Ara ...

,

Málaga

Málaga (, ) is a municipality of Spain, capital of the Province of Málaga, in the autonomous community of Andalusia. With a population of 578,460 in 2020, it is the second-most populous city in Andalusia after Seville and the sixth most po ...

,

Murcia

Murcia (, , ) is a city in south-eastern Spain, the capital and most populous city of the autonomous community of the Region of Murcia, and the seventh largest city in the country. It has a population of 460,349 inhabitants in 2021 (about one ...

,

Palma de Mallorca

Palma (; ; also known as ''Palma de Mallorca'', officially between 1983–88, 2006–08, and 2012–16) is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of the Balearic Islands in Spain. It is situated on the south coast of Mallorca ...

,

Las Palmas

Las Palmas (, ; ), officially Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, is a Spanish city and capital of Gran Canaria, in the Canary Islands, on the Atlantic Ocean.

It is the capital (jointly with Santa Cruz de Tenerife), the most populous city in the auto ...

de Gran Canaria and

Bilbao

)

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize = 275 px

, map_caption = Interactive map outlining Bilbao

, pushpin_map = Spain Basque Country#Spain#Europe

, pushpin_map_caption ...

.

Anatomically modern humans first arrived in the Iberian Peninsula around 42,000 years ago.

dwelled in the territory, in addition to the development of coastal trading colonies by

Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their his ...

ns and

Ancient Greeks

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

and the brief

Carthaginian rule over the Mediterranean coastline. The Roman conquest and colonization of the peninsula (

Hispania

Hispania ( la, Hispānia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: Hi ...

) ensued, bringing a

Roman acculturation of the population.

Receding of Western Roman imperial authority ushered in the

immigration of non-Roman peoples. Eventually, the

Visigoths

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is k ...

emerged as the dominant power in the peninsula by the fifth century. In the early eighth century, most of the peninsula was

conquered by the Umayyad Caliphate and during early Islamic rule,

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

became the dominant peninsular power, centered in

Córdoba. Several Christian kingdoms emerged in Northern Iberia, chief among them

León,

Castile,

Aragón

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises th ...

,

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of th ...

, and

Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

and over the next seven centuries, an intermittent southward expansion of these kingdoms, known as

Reconquista

The ' ( Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the N ...

, culminated with the Christian seizure of the

Emirate of Granada

)

, common_languages = Official language: Classical ArabicOther languages: Andalusi Arabic, Mozarabic, Berber, Ladino

, capital = Granada

, religion = Majority religion: Sunni IslamMinority religions:R ...

in 1492. Jews and Muslims were forced to choose between conversion to Catholicism or expulsion and the ''

Morisco

Moriscos (, ; pt, mouriscos ; Spanish for "Moorish") were former Muslims and their descendants whom the Roman Catholic church and the Spanish Crown commanded to convert to Christianity or face compulsory exile after Spain outlawed the open ...

'' converts were eventually

expelled.

The dynastic union of the

Crown of Castile

The Crown of Castile was a medieval polity in the Iberian Peninsula that formed in 1230 as a result of the third and definitive union of the crowns and, some decades later, the parliaments of the kingdoms of Castile and León upon the accessi ...

and the

Crown of Aragon

The Crown of Aragon ( , ) an, Corona d'Aragón ; ca, Corona d'Aragó, , , ; es, Corona de Aragón ; la, Corona Aragonum . was a composite monarchy ruled by one king, originated by the dynastic union of the Kingdom of Aragon and the County of ...

was followed by the

annexation of Navarre and the

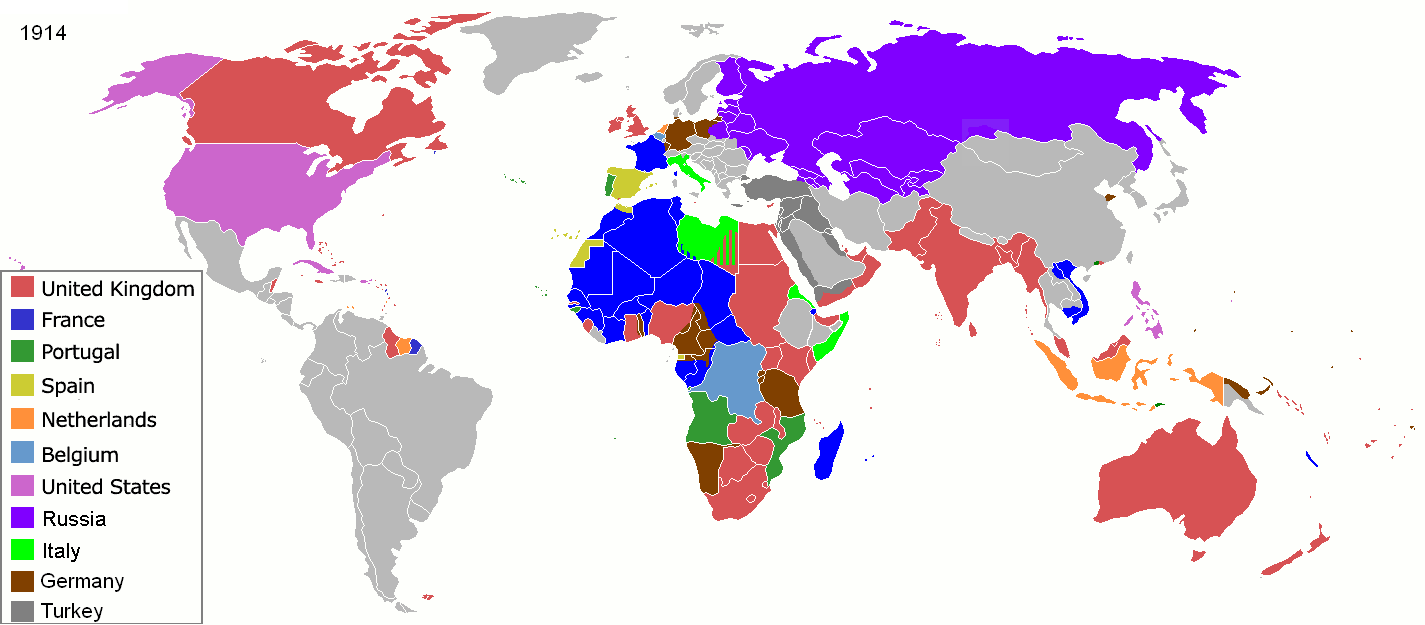

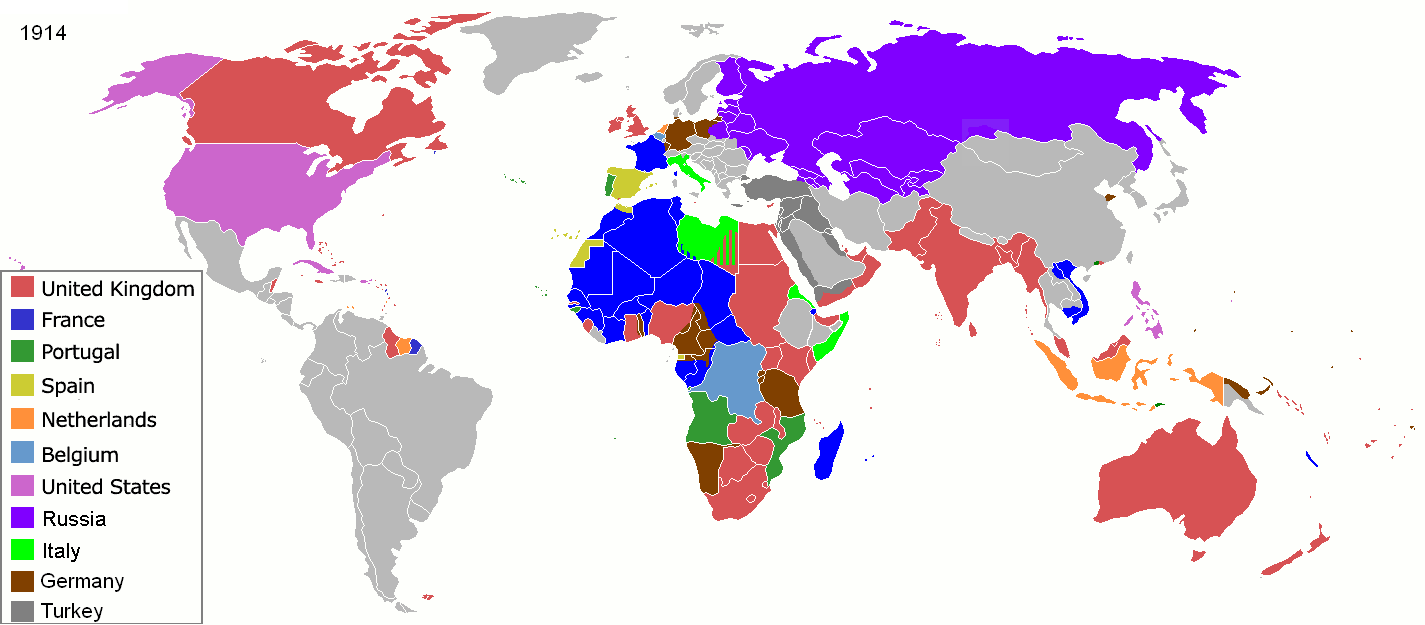

1580 incorporation of Portugal (which ended in 1640). In the wake of the Spanish colonization of the Americas after 1492, the Crown came to hold

a large overseas empire, which underpinned the emergence of a global trading system primarily fuelled by the precious metals extracted in the New World. Centralisation of the administration and further state-building in mainland Spain ensued in the 18th and 19th centuries, during which the Crown saw the loss of the bulk of its American colonies a few years after the

Peninsular War

The Peninsular War (1807–1814) was the military conflict fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Spain, Portugal, and the United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars. In Spai ...

. The country veered between different political regimes; monarchy and republic, and following a

1936–39 devastating civil war, the

Francoist dictatorship

Francoist Spain ( es, España franquista), or the Francoist dictatorship (), was the period of Spanish history between 1939 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death in 1975, Spa ...

that lasted until 1975. With the restoration of democracy under the

Constitution of Spain

The Spanish Constitution (Spanish, Asturleonese, and gl, Constitución Española; eu, Espainiako Konstituzioa; ca, Constitució Espanyola; oc, Constitucion espanhòla) is the democratic law that is supreme in the Kingdom of Spain. It was ...

and the entry into the European Union in 1986, the country experienced profound social and political change.

Spanish

art,

music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspe ...

,

literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to ...

and

cuisine

A cuisine is a style of cooking characterized by distinctive ingredients, techniques and dishes, and usually associated with a specific culture or geographic region. Regional food preparation techniques, customs, and ingredients combine to ...

have been influential worldwide, particularly in

Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

and the

Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America, North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World. ...

. As a reflection of its large

cultural wealth, Spain has the world's fourth-largest number of

World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for ...

s (49) and is the world's

second-most visited country. Its cultural influence extends over 570 million

Hispanophone

Hispanophone and Hispanic refers to anything relating to the Spanish language (the Hispanosphere).

In a cultural, rather than merely linguistic sense, the notion of "Hispanophone" goes further than the above definition. The Hispanic culture is th ...

s, making Spanish the world's

second-most spoken native language.

Spain is a

developed country

A developed country (or industrialized country, high-income country, more economically developed country (MEDC), advanced country) is a sovereign state that has a high quality of life, developed economy and advanced technological infrastruct ...

, a

secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin ''saeculum'', "worldly" or "of a generation"), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Anything that does not have an explicit reference to religion, either negativ ...

parliamentary democracy

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of t ...

and a

constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

, with King

Felipe VI

Felipe VI (;,

* eu, Felipe VI.a,

* ca, Felip VI,

* gl, Filipe VI, . Felipe Juan Pablo Alfonso de Todos los Santos de Borbón y Grecia; born 30 January 1968) is King of Spain. He is the son of former King Juan Carlos I and Queen Sofía, an ...

as

head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and ...

. It is a

high-income country

A developed country (or industrialized country, high-income country, more economically developed country (MEDC), advanced country) is a sovereign state that has a high quality of life, developed economy and advanced technological infrastruct ...

and an advanced economy, with the world's

sixteenth-largest economy by nominal GDP and the

sixteenth-largest by PPP. Spain has the twelve-highest

life expectancy

Life expectancy is a statistical measure of the average time an organism is expected to live, based on the year of its birth, current age, and other demographic factors like sex. The most commonly used measure is life expectancy at birth ...

in the world. It ranks particularly high in

healthcare quality

Health care quality is a level of value provided by any health care resource, as determined by some measurement. As with quality in other fields, it is an assessment of whether something is good enough and whether it is suitable for its purpose. ...

,

with its

healthcare system considered to be one of the most efficient worldwide. It is a world leader in

organ transplants

Organ transplantation is a medical procedure in which an organ is removed from one body and placed in the body of a recipient, to replace a damaged or missing organ. The donor and recipient may be at the same location, or organs may be transpor ...

and

organ donation

Organ donation is the process when a person allows an organ of their own to be removed and transplanted to another person, legally, either by consent while the donor is alive or dead with the assent of the next of kin.

Donation may be for re ...

. Spain is a member of the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

, the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

, the

Eurozone

The euro area, commonly called eurozone (EZ), is a currency union of 19 member states of the European Union (EU) that have adopted the euro (€) as their primary currency and sole legal tender, and have thus fully implemented EMU pol ...

, the

Council of Europe

The Council of Europe (CoE; french: Conseil de l'Europe, ) is an international organisation founded in the wake of World War II to uphold human rights, democracy and the rule of law in Europe. Founded in 1949, it has 46 member states, with a p ...

(CoE), the

Organization of Ibero-American States

The Organization of Ibero-American States ( es, Organización de Estados Iberoamericanos, pt, Organização de Estados Iberoamericanos, ca, Organització d'Estats Iberoamericans; abbreviated as OEI), formally the Organization of Ibero-American ...

(OEI), the

Union for the Mediterranean

The Union for the Mediterranean (UfM; french: Union pour la Méditerranée, ar, الإتحاد من أجل المتوسط ''Al-Ittiḥād min ajl al-Mutawasseṭ'') is an intergovernmental organization of 43 member states from Europe and the M ...

, the

North Atlantic Treaty Organization

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

(NATO), the

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD; french: Organisation de coopération et de développement économiques, ''OCDE'') is an intergovernmental organisation with 38 member countries, founded in 1961 to stimulate ...

(OECD),

Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) is the world's largest regional security-oriented intergovernmental organization with observer status at the United Nations. Its mandate includes issues such as arms control, pro ...

(OSCE), the

World Trade Organization

The World Trade Organization (WTO) is an intergovernmental organization that regulates and facilitates international trade. With effective cooperation

in the United Nations System, governments use the organization to establish, revise, and ...

(WTO) and many other international organisations.

Etymology

The origins of the

Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

name ''

Hispania

Hispania ( la, Hispānia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: Hi ...

'', and the modern ''España'', are uncertain, although the Phoenicians and Carthaginians referred to the region as ''Spania'', therefore the most widely accepted etymology is a

Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

-

Phoenician one. There have been a number of accounts and hypotheses of its origin:

The

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

scholar

Antonio de Nebrija proposed that the word ''Hispania'' evolved from the

Iberian word , meaning "city of the western world".

argued that the root of the term ''span'' is the

Phoenician word , meaning "to forge metals". Therefore, ''i-spn-ya'' would mean "the land where metals are forged". It may be a derivation of the Phoenician , meaning "island of rabbits", "land of rabbits" or "edge", a reference to Spain's location at the end of the Mediterranean; Roman coins struck in the region from the reign of

Hadrian

Hadrian (; la, Caesar Trâiānus Hadriānus ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He was born in Italica (close to modern Santiponce in Spain), a Roman ''municipium'' founded by Italic settlers in Hispania ...

show a female figure with a rabbit at her feet,

and

Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called " Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could s ...

called it the "land of the rabbits".

The word in question (compare modern Hebrew , ) actually means "

Hyrax

Hyraxes (), also called dassies, are small, thickset, herbivorous mammals in the order Hyracoidea. Hyraxes are well-furred, rotund animals with short tails. Typically, they measure between long and weigh between . They are superficially simila ...

", possibly due to Phoenicians confusing the two animals.

''Hispania'' may derive from the poetic use of the term ''

Hesperia'', reflecting the

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

perception of Italy as a "western land" or "land of the setting sun" (, in

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

) and Spain, being still further west, as .

There is the claim that "Hispania" derives from the

Basque word meaning "edge" or "border", another reference to the fact that the Iberian Peninsula constitutes the southwest corner of the European continent.

Two 15th-century Spanish Jewish scholars,

Don Isaac Abrabanel

Isaac ben Judah Abarbanel ( he, יצחק בן יהודה אברבנאל; 1437–1508), commonly referred to as Abarbanel (), also spelled Abravanel, Avravanel, or Abrabanel, was a Portuguese Jewish statesman, philosopher, Bible commentator ...

and

Solomon ibn Verga, gave an explanation now considered folkloric: both men wrote in two different published works that the first Jews to reach Spain were brought by ship by Phiros who was confederate with the king of Babylon when he laid siege to Jerusalem. Phiros was a

Grecian

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser exten ...

by birth, but who had been given a kingdom in Spain. Phiros became related by marriage to Espan, the nephew of king Heracles, who also ruled over a kingdom in Spain. Heracles later renounced his throne in preference for his native Greece, leaving his kingdom to his nephew, Espan, from whom the country of ''España'' (Spain) took its name. Based upon their testimonies, this eponym would have already been in use in Spain by .

History

Prehistory and pre-Roman peoples

Archaeological research at

Atapuerca indicates the Iberian Peninsula was populated by

hominid

The Hominidae (), whose members are known as the great apes or hominids (), are a taxonomic family of primates that includes eight extant species in four genera: '' Pongo'' (the Bornean, Sumatran and Tapanuli orangutan); ''Gorilla'' (the ...

s 1.2 million years ago. In

Atapuerca fossils have been found of the earliest known

hominins in Europe, ''

Homo antecessor''. Modern humans first arrived in Iberia, from the north on foot, about 35,000 years ago. The best known artefacts of these prehistoric human settlements are the famous paintings in the

Altamira cave of Cantabria in northern Iberia, which were created from 35,600 to 13,500

BCE by

Cro-Magnon

Early European modern humans (EEMH), or Cro-Magnons, were the first early modern humans (''Homo sapiens'') to settle in Europe, migrating from Western Asia, continuously occupying the continent possibly from as early as 56,800 years ago. They i ...

.

Archaeological and genetic evidence suggests that the Iberian Peninsula acted as one of several major refugia from which northern Europe was repopulated following the end of the

last ice age.

The largest groups inhabiting the Iberian Peninsula before the Roman conquest were the

Iberians

The Iberians ( la, Hibērī, from el, Ἴβηρες, ''Iberes'') were an ancient people settled in the eastern and southern coasts of the Iberian peninsula, at least from the 6th century BC. They are described in Greek and Roman sources (amon ...

and the

Celts

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient ...

. The Iberians inhabited the Mediterranean side of the peninsula, from the northeast to the southeast. The Celts inhabited much of the interior and Atlantic side of the peninsula, from the northwest to the southwest.

Basques

The Basques ( or ; eu, euskaldunak ; es, vascos ; french: basques ) are a Southwestern European ethnic group, characterised by the Basque language, a common culture and shared genetic ancestry to the ancient Vascones and Aquitanians. Ba ...

occupied the western area of the Pyrenees mountain range and adjacent areas, the Phoenician-influenced

Tartessians

Tartessos ( es, Tarteso) is, as defined by archaeological discoveries, a historical civilization settled in the region of Southern Spain characterized by its mixture of local Paleohispanic and Phoenician traits. It had a proper writing system ...

culture flourished in the southwest and the

Lusitanians

The Lusitanians ( la, Lusitani) were an Indo-European speaking people living in the west of the Iberian Peninsula prior to its conquest by the Roman Republic and the subsequent incorporation of the territory into the Roman province of Lusitania. ...

and

Vettones

The Vettones (Greek: ''Ouettones'') were a pre-Roman people of the Iberian Peninsula of possibly Celtic ethnicity.

Origins

Lujan (2007) concludes that some of the names of the Vettones show clearly western Hispano-Celtic features. Reissued i ...

occupied areas in the central west. Several cities were founded along the coast by

Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their his ...

ns, and trading outposts and colonies were established by

Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, ot ...

in the East. Eventually, Phoenician-

Carthaginians

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' – the Latin equivalent of the ...

expanded inland towards the meseta; however, due to the bellicose inland tribes, the Carthaginians got settled in the coasts of the Iberian Peninsula.

Roman Hispania and the Visigothic Kingdom

During the

Second Punic War

The Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) was the second of three wars fought between Carthage and Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. For 17 years the two states struggled for supremacy, primarily in Ital ...

, roughly between 210 and 205 BCE the expanding

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

captured Carthaginian trading colonies along the Mediterranean coast. Although it took the Romans nearly two centuries to complete the

conquest of the Iberian Peninsula, they retained control of it for over six centuries. Roman rule was bound together by law, language, and the

Roman road

Roman roads ( la, viae Romanae ; singular: ; meaning "Roman way") were physical infrastructure vital to the maintenance and development of the Roman state, and were built from about 300 BC through the expansion and consolidation of the Roman Re ...

.

The cultures of the pre-Roman populations were gradually

Romanised

Romanization or romanisation, in linguistics, is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, and ...

(Latinised) at different rates depending on what part of the peninsula they lived in, with local leaders being admitted into the Roman aristocratic class.

Hispania served as a granary for the Roman market, and its harbours exported gold,

wool

Wool is the textile fibre obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have properties similar to animal wool. ...

,

olive oil

Olive oil is a liquid fat obtained from olives (the fruit of ''Olea europaea''; family Oleaceae), a traditional tree crop of the Mediterranean Basin, produced by pressing whole olives and extracting the oil. It is commonly used in cooking: ...

, and wine. Agricultural production increased with the introduction of irrigation projects, some of which remain in use. Emperors

Hadrian

Hadrian (; la, Caesar Trâiānus Hadriānus ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He was born in Italica (close to modern Santiponce in Spain), a Roman ''municipium'' founded by Italic settlers in Hispania ...

,

Trajan

Trajan ( ; la, Caesar Nerva Traianus; 18 September 539/11 August 117) was Roman emperor from 98 to 117. Officially declared ''optimus princeps'' ("best ruler") by the senate, Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presi ...

,

Theodosius I

Theodosius I ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος ; 11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also called Theodosius the Great, was Roman emperor from 379 to 395. During his reign, he succeeded in a crucial war against the Goths, as well as in two ...

, and the philosopher

Seneca were born in Hispania. Christianity was introduced into Hispania in the 1st century CE and it became popular in the cities in the 2nd century CE.

Most of Spain's present languages and religion, and the basis of its laws, originate from this period.

In the late 2nd century (starting in 170 CE) incursions of North-African

Mauri

Mauri (from which derives the English term "Moors") was the Latin designation for the Berber population of Mauretania, located in the part of North Africa west of Numidia, in present-day northern Morocco and northwestern Algeria.

Name

''Mauri'' ...

in the province of

Baetica

Hispania Baetica, often abbreviated Baetica, was one of three Roman provinces in Hispania (the Iberian Peninsula). Baetica was bordered to the west by Lusitania, and to the northeast by Hispania Tarraconensis. Baetica remained one of the basi ...

took place.

The

Germanic Suebi

The Suebi (or Suebians, also spelled Suevi, Suavi) were a large group of Germanic peoples originally from the Elbe river region in what is now Germany and the Czech Republic. In the early Roman era they included many peoples with their own name ...

and

Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

, together with the

Sarmatian

The Sarmatians (; grc, Σαρμαται, Sarmatai; Latin: ) were a large confederation of ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic peoples of classical antiquity who dominated the Pontic steppe from about the 3rd century BC to the 4th cen ...

Alans

The Alans (Latin: ''Alani'') were an ancient and medieval Iranian nomadic pastoral people of the North Caucasus – generally regarded as part of the Sarmatians, and possibly related to the Massagetae. Modern historians have connected the A ...

entered the peninsula after 409, henceforth weakening the Western Roman Empire's jurisdiction over Hispania. These tribes had crossed the

Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, source ...

in early 407 and ravaged

Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

. The Suebi established a kingdom in north-western Iberia whereas the Vandals established themselves in the south of the peninsula by 420 before crossing over to North Africa in 429. As the western empire disintegrated, the social and economic base became greatly simplified: but even in modified form, the successor regimes maintained many of the institutions and laws of the late empire, including Christianity and assimilation to the evolving Roman culture.

The

Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

s established an occidental province,

Spania

Spania ( la, Provincia Spaniae) was a province of the Eastern Roman Empire from 552 until 624 in the south of the Iberian Peninsula and the Balearic Islands. It was established by the Emperor Justinian I in an effort to restore the western prov ...

, in the south, with the intention of reviving Roman rule throughout Iberia. Eventually, however, Hispania was reunited under

Visigothic rule. These

Visigoths

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is k ...

, or Western Goths, after

sacking Rome under the leadership of

Alaric (410 CE), turned towards the

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

, with

Athaulf as their leader, and occupied the northeastern portion.

Wallia

Wallia or Walha ( Spanish: ''Walia'', Portuguese ''Vália''), ( 385 – 418) was king of the Visigoths from 415 to 418, earning a reputation as a great warrior and prudent ruler. He was elected to the throne after Athaulf and then Sigeric were ...

extended his rule over most of the peninsula, confining the Suebians to Galicia.

Theodoric I

Theodoric I ( got, Þiudarīks; la, Theodericus; 390 or 393 – 20 or 24 June 451) was the King of the Visigoths from 418 to 451. Theodoric is famous for his part in stopping Attila (the Hun) at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains in 451, where ...

took part, with the Romans and Franks, in the

Battle of the Catalaunian Plains

The Battle of the Catalaunian Plains (or Fields), also called the Battle of the Campus Mauriacus, Battle of Châlons, Battle of Troyes or the Battle of Maurica, took place on June 20, 451 AD, between a coalition – led by the Western Roman ...

, where

Attila

Attila (, ; ), frequently called Attila the Hun, was the ruler of the Huns from 434 until his death in March 453. He was also the leader of a tribal empire consisting of Huns, Ostrogoths, Alans, and Bulgars, among others, in Central and E ...

was routed.

Euric

Euric (Gothic: ''* Aiwareiks'', see '' Eric''), also known as Evaric, or Eurico in Spanish and Portuguese (c. 420 – 28 December 484), son of Theodoric I, ruled as king (''rex'') of the Visigoths, after murdering his brother, Theodoric II, ...

(466 CE), who put an end to the last remnants of Roman power in the peninsula, may be considered the first monarch of Spain, though the Suebians still maintained their independence in Galicia. Euric was also the first king to give written laws to the Visigoths. In the following reigns the Catholic kings of France assumed the role of protectors of the Hispano-Roman Catholics against the Arianism of the Visigoths, and in the

wars which ensued

Alaric II

Alaric II ( got, 𐌰𐌻𐌰𐍂𐌴𐌹𐌺𐍃, , "ruler of all"; la, Alaricus; – August 507) was the King of the Visigoths from 484 until 507. He succeeded his father Euric as king of the Visigoths in Toulouse on 28 December 484; he wa ...

and

Amalaric

Amalaric ( got, *Amalareiks; Spanish and Portuguese: ''Amalarico''; 502–531) was king of the Visigoths from 522 until his death in battle in 531. He was a son of king Alaric II and his first wife Theodegotha, daughter of Theoderic the Great.

...

died.

Athanagild, having risen against King

Agila, called in the Byzantines and, in payment for the support they gave him, ceded to them the maritime places of the southeast (554 CE).

Liuvigild

Liuvigild, Leuvigild, Leovigild, or ''Leovigildo'' ( Spanish and Portuguese), ( 519 – 586) was a Visigothic King of Hispania and Septimania from 568 to 586. Known for his Codex Revisus or Code of Leovigild, a law allowing equal rights between ...

restored the political unity of the peninsula, subduing the Suebians, but the religious divisions of the country, reaching even the royal family, brought on a civil war.

St. Hermengild

Saint Hermenegild or Ermengild (died 13 April 585; es, San Hermenegildo; la, Hermenegildus, from Gothic ''*Airmana-gild'', "immense tribute"), was the son of king Liuvigild of the Visigothic Kingdom in the Iberian Peninsula and southern Fra ...

, the king's son, putting himself at the head of the Catholics, was defeated and taken prisoner, and suffered martyrdom for rejecting communion with the Arians.

Recared

Reccared I (or Recared; la, Flavius Reccaredus; es, Flavio Recaredo; 559 – December 601; reigned 586–601) was Visigothic King of Hispania and Septimania. His reign marked a climactic shift in history, with the king's renunciation of Arianis ...

, son of Liuvigild and brother of St. Hermengild, added religious unity to the political unity achieved by his father, accepting the Catholic faith in the

Third Council of Toledo (589 CE). The religious unity established by this council was the basis of that fusion of Goths with Hispano-Romans which produced the Spanish nation.

Sisebut

Sisebut ( la, Sisebutus, es, Sisebuto; also ''Sisebuth'', ''Sisebur'', ''Sisebod'' or ''Sigebut'') ( 565 – February 621) was King of the Visigoths and ruler of Hispania and Septimania from 612 until his death.

Biography

He campaigned succe ...

and

Suintila

Suintila, or ''Suinthila'', ''Swinthila'', ''Svinthila''; (ca. 588 – 633/635) was Visigothic King of Hispania, Septimania and Galicia from 621 to 631. He was a son of Reccared I and his wife Bado, and a brother of the general Geila. Under S ...

completed the expulsion of the Byzantines from Spain.

Intermarriage between Visigoths and Hispano-Romans was prohibited, though in practice it could not be entirely prevented and was eventually legalised by Liuvigild. The Spanish-Gothic scholars such as

Braulio of Zaragoza

Braulio ( la, Braulius Caesaraugustanus; 585 – 651 AD) was bishop of Zaragoza and a learned cleric living in the Kingdom of the Visigoths.

Life

Braulio was born of a noble Hispano-Roman family. His father was Bishop of Osma. In 610 Braulio ...

and

Isidore of Seville

Isidore of Seville ( la, Isidorus Hispalensis; c. 560 – 4 April 636) was a Spanish scholar, theologian, and archbishop of Seville. He is widely regarded, in the words of 19th-century historian Montalembert, as "the last scholar of ...

played an important role in keeping the classical

Greek and Roman culture. Isidore was one of the most influential clerics and philosophers in the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

in Europe, and his theories were also vital to the conversion of the Visigothic Kingdom from an

Arian

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God ...

domain to a Catholic one in the

Councils of Toledo

From the 5th century to the 7th century AD, about thirty synods, variously counted, were held at Toledo (''Concilia toletana'') in what would come to be part of Spain. The earliest, directed against Priscillianism, assembled in 400. The "thir ...

. Isidore created the first western

encyclopedia

An encyclopedia (American English) or encyclopædia (British English) is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge either general or special to a particular field or discipline. Encyclopedias are divided into articles ...

which had a huge impact during the Middle Ages.

Muslim era and ''Reconquista''

From 711 to 718, as part of the expansion of the

Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by th ...

, which had

conquered North Africa from the

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

, nearly all of the Iberian Peninsula was conquered by Muslim armies from across the Strait of Gibraltar, resulting in the collapse of the Visigothic Kingdom. Only a small area in the mountainous north of the peninsula stood out of the territory seized during the initial invasion. The

Kingdom of Asturias-León consolidated upon this pocket of territory. Other Christian kingdoms such as

Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

and

Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to s ...

in the mountainous north eventually surged upon the consolidation of counties of the Carolingian ''

Marca Hispanica

The Hispanic March or Spanish March ( es, Marca Hispánica, ca, Marca Hispànica, Aragonese and oc, Marca Hispanica, eu, Hispaniako Marka, french: Marche d'Espagne), was a military buffer zone beyond the former province of Septimania, estab ...

''. For several centuries, the fluctuating frontier between the Muslim and Christian controlled areas of the peninsula was along the

Ebro

, name_etymology =

, image = Zaragoza shel.JPG

, image_size =

, image_caption = The Ebro River in Zaragoza

, map = SpainEbroBasin.png

, map_size =

, map_caption = The Ebro ...

and

Douro

The Douro (, , ; es, Duero ; la, Durius) is the highest-flow river of the Iberian Peninsula. It rises near Duruelo de la Sierra in Soria Province, central Spain, meanders south briefly then flows generally west through the north-west part o ...

valleys.

Under

Islamic law

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the ...

, Christians and Jews were given the subordinate status of

dhimmi

' ( ar, ذمي ', , collectively ''/'' "the people of the covenant") or () is a historical term for non-Muslims living in an Islamic state with legal protection. The word literally means "protected person", referring to the state's obligatio ...

. This status permitted Christians and Jews to practice their religions as ''

People of the Book

People of the Book or Ahl al-kitāb ( ar, أهل الكتاب) is an Islamic term referring to those religions which Muslims regard as having been guided by previous revelations, generally in the form of a scripture. In the Quran they are ide ...

'' but they were required to pay a special tax and had legal and social rights inferior to those of Muslims.

Conversion to

Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

proceeded at an increasing pace. The ''

muladíes'' (Muslims of ethnic Iberian origin) are believed to have formed the majority of the population of Al-Andalus by the end of the 10th century.

The Muslim society was itself diverse and beset by social tensions. The North-African

Berber people

, image = File:Berber_flag.svg

, caption = The Berber ethnic flag

, population = 36 million

, region1 = Morocco

, pop1 = 14 million to 18 million

, region2 = Algeria

, pop2 ...

s, who had provided the bulk of the invading armies,

clashed with the Arab leadership from the

Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

. Over time, large Moorish populations became established, especially in the

Guadalquivir River

The Guadalquivir (, also , , ) is the fifth-longest river in the Iberian Peninsula and the second-longest river with its entire length in Spain. The Guadalquivir is the only major navigable river in Spain. Currently it is navigable from the Gul ...

valley, the coastal plain of

Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. The wider urban area al ...

, the

Ebro River

, name_etymology =

, image = Zaragoza shel.JPG

, image_size =

, image_caption = The Ebro River in Zaragoza

, map = SpainEbroBasin.png

, map_size =

, map_caption = The Ebro ...

valley and (towards the end of this period) in the mountainous region of

Granada

Granada (,, DIN: ; grc, Ἐλιβύργη, Elibýrgē; la, Illiberis or . ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains, at the c ...

.

A series of

Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

incursions raided the coasts of the Iberian Peninsula in the 9th and 10th centuries. The first recorded Viking raid on Iberia took place in 844; it ended in failure with many Vikings killed by the Galicians'

ballista

The ballista (Latin, from Greek βαλλίστρα ''ballistra'' and that from βάλλω ''ballō'', "throw"), plural ballistae, sometimes called bolt thrower, was an ancient missile weapon that launched either bolts or stones at a distant ...

s; and seventy of the Vikings' longships captured on the beach and burned by the troops of King

Ramiro I of Asturias

Ramiro I (c. 790 – 1 February 850) was king of Asturias (modern-day Spain) from 842 until his death in 850. Son of King Bermudo I, he became king following a succession struggle after his predecessor, Alfonso II, died without children. During ...

.

Córdoba, the capital of the caliphate since

Abd-ar-Rahman III

ʿAbd al-Rahmān ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn al-Ḥakam al-Rabdī ibn Hishām ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Dākhil () or ʿAbd al-Rahmān III (890 - 961), was the Umayyad Emir of Córdoba from 912 to 9 ...

, was the largest, richest and most sophisticated city in western Europe. Mediterranean trade and cultural exchange flourished.

Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

imported a rich intellectual tradition from the Middle East and North Africa. Some important philosophers at the time were

Averroes

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psy ...

,

Ibn Arabi

Ibn ʿArabī ( ar, ابن عربي, ; full name: , ; 1165–1240), nicknamed al-Qushayrī (, ) and Sulṭān al-ʿĀrifīn (, , ' Sultan of the Knowers'), was an Arab Andalusian Muslim scholar, mystic, poet, and philosopher, extremely influen ...

and

Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah ...

. The

Romanised

Romanization or romanisation, in linguistics, is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, and ...

cultures of the Iberian Peninsula interacted with

Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

and

Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

cultures in complex ways, giving the region a distinctive culture.

Outside the cities, where the vast majority lived, the land ownership system from Roman times remained largely intact as Muslim leaders rarely dispossessed landowners and the introduction of new crops and techniques led to an expansion of agriculture introducing new produces which originally came from Asia or the former territories of the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

.

In the 11th century, the Caliphate of Córdoba collapsed, fracturing into a series of petty kingdoms (''

Taifa

The ''taifas'' (singular ''taifa'', from ar, طائفة ''ṭā'ifa'', plural طوائف ''ṭawā'if'', a party, band or faction) were the independent Muslim principalities and kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula (modern Portugal and Spain), re ...

s''), often subject to the payment of a form of

protection money

A protection racket is a type of racket and a scheme of organized crime perpetrated by a potentially hazardous organized crime group that generally guarantees protection outside the sanction of the law to another entity or individual from vi ...

(''

Parias

In medieval Spain, ''parias'' (from medieval Latin ''pariāre'', "to make equal n account, i.e. pay) were a form of tribute paid by the ''taifas'' of al-Andalus to the Christian kingdoms of the north. ''Parias'' dominated relations between the ...

'') to the Northern Christian kingdoms, which otherwise undertook a southward territorial expansion. The capture of the strategic city of

Toledo in 1085 marked a significant shift in the balance of power in favour of the Christian kingdoms. The arrival from North Africa of the Islamic ruling sects of the

Almoravids

The Almoravid dynasty ( ar, المرابطون, translit=Al-Murābiṭūn, lit=those from the ribats) was an imperial Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire in the 11th century that s ...

and the

Almohads

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the unity of God) was a North African Berber Muslim empire ...

achieved temporary unity upon the Muslim-ruled territory, with a stricter, less tolerant application of Islam, and partially reversed some Christian territorial gains.

The

Kingdom of León

The Kingdom of León; es, Reino de León; gl, Reino de León; pt, Reino de Leão; la, Regnum Legionense; mwl, Reino de Lhion was an independent kingdom situated in the northwest region of the Iberian Peninsula. It was founded in 910 when t ...

was the strongest Christian kingdom for centuries. In 1188 the first modern parliamentary session in Europe was held in

León (

Cortes of León

Cortes, Cortés, Cortês, Corts, or Cortès may refer to:

People

* Cortes (surname), including a list of people with the name

** Hernán Cortés (1485–1547), a Spanish conquistador

Places

* Cortes, Navarre, a village in the South border o ...

). The

Kingdom of Castile

The Kingdom of Castile (; es, Reino de Castilla, la, Regnum Castellae) was a large and powerful state on the Iberian Peninsula during the Middle Ages. Its name comes from the host of castles constructed in the region. It began in the 9th ce ...

, formed from Leonese territory, was its successor as strongest kingdom. The kings and the nobility fought for power and influence in this period. The example of the Roman emperors influenced the political objective of the Crown, while the nobles benefited from

feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structu ...

.

Muslim strongholds in the

Guadalquivir Valley such as Córdoba (1236) and

Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Penins ...

(1248) fell to Castile in the 13th century. The

County of Barcelona

The County of Barcelona ( la, Comitatus Barcinonensis, ca, Comtat de Barcelona) was originally a frontier region under the rule of the Carolingian dynasty. In the 10th century, the Counts of Barcelona became progressively independent, heredi ...

and the

Kingdom of Aragon

The Kingdom of Aragon ( an, Reino d'Aragón, ca, Regne d'Aragó, la, Regnum Aragoniae, es, Reino de Aragón) was a medieval and early modern kingdom on the Iberian Peninsula, corresponding to the modern-day autonomous community of Aragon ...

entered in a dynastic union and gained territory and power in the Mediterranean. In 1229

Majorca

Mallorca, or Majorca, is the largest island in the Balearic Islands, which are part of Spain and located in the Mediterranean.

The capital of the island, Palma, is also the capital of the autonomous community of the Balearic Islands. The Bale ...

was conquered, so was

Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. The wider urban area al ...

in 1238. In the 13th and 14th centuries, the North-African

Marinid

The Marinid Sultanate was a Berber Muslim empire from the mid-13th to the 15th century which controlled present-day Morocco and, intermittently, other parts of North Africa (Algeria and Tunisia) and of the southern Iberian Peninsula (Spain) ar ...

s established some enclaves around the Strait of Gibraltar.

From the mid 13th century, literature and philosophy started to flourish again in the Christian peninsular kingdoms, based on Roman and Gothic traditions. An important philosopher from this time is

Ramon Llull

Ramon Llull (; c. 1232 – c. 1315/16) was a philosopher, theologian, poet, missionary, and Christian apologist from the Kingdom of Majorca.

He invented a philosophical system known as the ''Art'', conceived as a type of universal logic to pro ...

.

Abraham Cresques

Abraham Cresques (, 1325–1387), whose real name was Cresques (son of) Abraham, was a 14th-century Jewish cartographer from Palma, Majorca (then part of the Crown of Aragon). In collaboration with his son, Jehuda Cresques, Cresques is credit ...

was a prominent Jewish cartographer.

Roman law

Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the '' Corpus Juris Civilis'' (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor J ...

and its institutions were the model for the legislators. The king

Alfonso X of Castile

Alfonso X (also known as the Wise, es, el Sabio; 23 November 1221 – 4 April 1284) was King of Castile, León and Galicia from 30 May 1252 until his death in 1284. During the election of 1257, a dissident faction chose him to be king of Ger ...

focused on strengthening this Roman and Gothic past, and also on linking the Iberian Christian kingdoms with the rest of medieval European

Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwin ...

. Alfonso worked for being elected emperor of the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

and published the

Siete Partidas

The ''Siete Partidas'' (, "Seven-Part Code") or simply ''Partidas'', was a Castilian statutory code first compiled during the reign of Alfonso X of Castile (1252–1284), with the intent of establishing a uniform body of normative rules for the ...

code. The

Toledo School of Translators

The Toledo School of Translators ( es, Escuela de Traductores de Toledo) is the group of scholars who worked together in the city of Toledo during the 12th and 13th centuries, to translate many of the Judeo-Islamic philosophies and scientific w ...

is the name that commonly describes the group of scholars who worked together in the city of Toledo during the 12th and 13th centuries, to translate many of the philosophical and scientific works from

Classical Arabic

Classical Arabic ( ar, links=no, ٱلْعَرَبِيَّةُ ٱلْفُصْحَىٰ, al-ʿarabīyah al-fuṣḥā) or Quranic Arabic is the standardized literary form of Arabic used from the 7th century and throughout the Middle Ages, most notab ...

,

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic pe ...

, and

Ancient Hebrew.

The 13th century also witnessed the Crown of Aragon, centred in Spain's north east, expand its reach across islands in the Mediterranean, to

Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

and Naples. Around this time the universities of

Palencia (1212/1263) and

Salamanca

Salamanca () is a city in western Spain and is the capital of the Province of Salamanca in the autonomous community of Castile and León. The city lies on several rolling hills by the Tormes River. Its Old City was declared a UNESCO World Herit ...

(1218/1254) were established. The

Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

of 1348 and 1349 devastated Spain.

In 1311, Catalan mercenaries won a victory at the

Battle of Halmyros, seizing the

Frankish Duchy of Athens

The Duchy of Athens (Greek: Δουκᾶτον Ἀθηνῶν, ''Doukaton Athinon''; Catalan: ''Ducat d'Atenes'') was one of the Crusader states set up in Greece after the conquest of the Byzantine Empire during the Fourth Crusade as part of th ...

.

[

The royal line of Aragon became extinct with ]Martin the Humane

Martin the Humane (29 July 1356 – 31 May 1410), also called the Elder and the Ecclesiastic, was King of Aragon, Valencia, Sardinia and Corsica and Count of Barcelona from 1396 and King of Sicily from 1409 (as Martin II). He failed to secure the ...

, and the Compromise of Caspe

The 1412 Compromise of Caspe (''Compromís de Casp'' in Catalan) was an act and resolution of parliamentary representatives of the constituent realms of the Crown of Aragon (the Kingdom of Aragon, Kingdom of Valencia, and Principality of Cata ...

gave the Crown to the House of Trastámara

The House of Trastámara ( Spanish, Aragonese and Catalan: Casa de Trastámara) was a royal dynasty which first ruled in the Crown of Castile and then expanded to the Crown of Aragon in the late middle ages to the early modern period.

They were ...

, already reigning in Castile.

As in the rest of Europe during the Late Middle Ages, antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

greatly increased during the 14th century in the Christian kingdoms. (A key event in that regard was the Black Death, as Jews were accused of poisoning the waters.) There were mass killings in Aragon in the mid-14th century, and 12,000 Jews were killed in Toledo. In 1391, Christian mobs went from town to town throughout Castile and Aragon, killing an estimated 50,000 Jews. Women and children were sold as slaves to Muslims, and many synagogues were converted into churches. According to Hasdai Crescas

Hasdai ben Abraham Crescas (; he, חסדאי קרשקש; c. 1340 in Barcelona – 1410/11 in Zaragoza) was a Spanish-Jewish philosopher and a renowned halakhist (teacher of Jewish law). Along with Maimonides ("Rambam"), Gersonides ("Ralbag"), ...

, about 70 Jewish communities were destroyed.

This period saw a contrast in landowning characteristics between the western and north-western territories in Andalusia, where the nobility and the religious orders succeeded into the creation of large ''latifundia'' entitled to them, whereas in the Kingdom of Granada (eastern Andalusia), a Crown-auspiciated distribution of the land to medium and small farmers took place.

Upon the conclusion of the Granada War

The Granada War ( es, Guerra de Granada) was a series of military campaigns between 1482 and 1491 during the reign of the Catholic Monarchs, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon, against the Nasrid dynasty's Emirate of Granada. It e ...

, the Nasrid Sultanate of Granada (the remaining Muslim-ruled polity in the Iberian Peninsula after 1246) capitulated in 1492 to the military strength of the Catholic Monarchs