S.S. Normandie on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The SS ''Normandie'' was a French

Work by the ''Société Anonyme des Chantiers de Penhoët'' began on the unnamed flagship on 26 January 1931 at

Work by the ''Société Anonyme des Chantiers de Penhoët'' began on the unnamed flagship on 26 January 1931 at

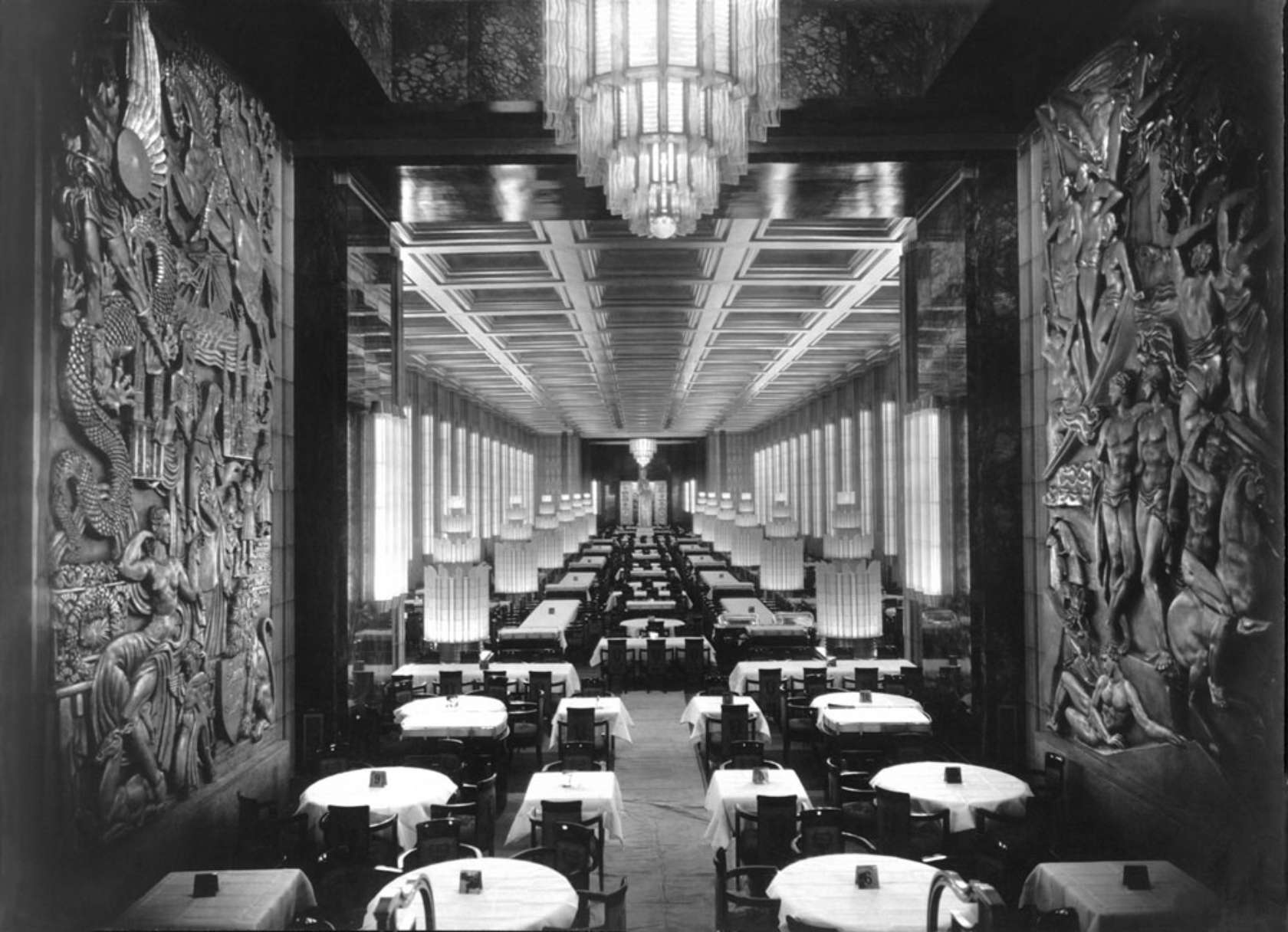

''Normandie''s first-class dining hall was the largest room afloat. At , it was longer than the

''Normandie''s first-class dining hall was the largest room afloat. At , it was longer than the

Part of ''Normandie''s problem lay in the fact that the majority of her passenger space was devoted solely to first class, which could carry up to 848 people. Less space and consideration were given to second and tourist class, which numbered only 670 and 454 passengers respectively. As a result, the consensus among North Atlantic passengers was that she was primarily a ship for the rich and famous. In contrast, in ''Queen Mary'', Cunard White Star had placed just as much emphasis on decor, space, and accommodation in second and tourist class as in first class. Thus ''Queen Mary'' accommodated American tourists, who had become numerous in the 1920s and 1930s. Many of these passengers could not afford first-class passage yet wanted to travel with much of the same comfort as those experienced in first. As a result, second and tourist class became a major cash source for shipping companies at that time. ''Queen Mary'' would accommodate these trends and subsequently the liner achieved greater popularity among North Atlantic travellers during the late thirties.

Another of the CGT's greatest triumphs also turned out to be one of ''Normandie''s greatest flaws: her decor. The ship's slick and modern Art Déco interiors proved to be somewhat intimidating and uncomfortable for her travellers, with some claiming that interiors gave them migraines. It was also here that ''Queen Mary'' triumphed over her French rival. Although also decorated in an Art Déco style, ''Queen Mary'' was more restrained in her appointments and was not as radical as ''Normandie'', and proved ultimately to be more popular with travellers.

Part of ''Normandie''s problem lay in the fact that the majority of her passenger space was devoted solely to first class, which could carry up to 848 people. Less space and consideration were given to second and tourist class, which numbered only 670 and 454 passengers respectively. As a result, the consensus among North Atlantic passengers was that she was primarily a ship for the rich and famous. In contrast, in ''Queen Mary'', Cunard White Star had placed just as much emphasis on decor, space, and accommodation in second and tourist class as in first class. Thus ''Queen Mary'' accommodated American tourists, who had become numerous in the 1920s and 1930s. Many of these passengers could not afford first-class passage yet wanted to travel with much of the same comfort as those experienced in first. As a result, second and tourist class became a major cash source for shipping companies at that time. ''Queen Mary'' would accommodate these trends and subsequently the liner achieved greater popularity among North Atlantic travellers during the late thirties.

Another of the CGT's greatest triumphs also turned out to be one of ''Normandie''s greatest flaws: her decor. The ship's slick and modern Art Déco interiors proved to be somewhat intimidating and uncomfortable for her travellers, with some claiming that interiors gave them migraines. It was also here that ''Queen Mary'' triumphed over her French rival. Although also decorated in an Art Déco style, ''Queen Mary'' was more restrained in her appointments and was not as radical as ''Normandie'', and proved ultimately to be more popular with travellers.

As a result, ''Normandie'' at many times throughout her service history carried less than half her full complement of passengers. Her German rivals ''Bremen'' and ''Europa'', and Italian rivals ''Rex'' and also suffered from this problem; despite their innovative designs and luxurious interiors, they made little profit for their respective companies. Contributing to this were international boycotts against

As a result, ''Normandie'' at many times throughout her service history carried less than half her full complement of passengers. Her German rivals ''Bremen'' and ''Europa'', and Italian rivals ''Rex'' and also suffered from this problem; despite their innovative designs and luxurious interiors, they made little profit for their respective companies. Contributing to this were international boycotts against

On 20 December 1941, the Auxiliary Vessels Board officially recorded

On 20 December 1941, the Auxiliary Vessels Board officially recorded

Enemy sabotage was widely suspected, but a congressional investigation in the wake of the sinking, chaired by

Enemy sabotage was widely suspected, but a congressional investigation in the wake of the sinking, chaired by

Also surviving are some examples of the 24,000 pieces of crystal, some from the massive Lalique torchères that adorned her dining salon. Also extant are some of the room's table silverware, chairs, and gold-plated bronze table bases. Custom-designed suite and cabin furniture as well as original artwork and statues that decorated the ship, or were built for use by the CGT aboard ''Normandie'', also survive today.

The eight-foot-high, 1,000-pound bronze figural sculpture of a woman named "''La Normandie''", which was at the top of the grand stairway from the first class smoking room up to the grill room café, was found in a New Jersey scrapyard in 1954 and was purchased for the then-new

Also surviving are some examples of the 24,000 pieces of crystal, some from the massive Lalique torchères that adorned her dining salon. Also extant are some of the room's table silverware, chairs, and gold-plated bronze table bases. Custom-designed suite and cabin furniture as well as original artwork and statues that decorated the ship, or were built for use by the CGT aboard ''Normandie'', also survive today.

The eight-foot-high, 1,000-pound bronze figural sculpture of a woman named "''La Normandie''", which was at the top of the grand stairway from the first class smoking room up to the grill room café, was found in a New Jersey scrapyard in 1954 and was purchased for the then-new

How Biggest Ship Was Safely Launched, February 1933, ''Popular Science''

slipway and launching of French passenger liner ''Normandie'' in 1933—excellent drawing and illustrations showing basics of process

"The Queen Of The Seven Seas" ''Popular Mechanics'', June 1935

"Normandie a Marvel in Speed and Comfort" ''Popular Mechanics'', August 1935

detailed drawings on steam-electric drive system

"Across the Atlantic in a Blue Ribbon Winner" ''Popular Mechanics'', October 1935

The ''Normandie'' – virtual reality tour of the Art Deco masterpiece

* Pictures in the official French Lines Archives

SS ''Normandie''

(French captions)

*

Hommage Au Normandie Exhibition, New York

SS ''Normandie'' – Ocean Liner Museum Exhibit in New York City

, - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Normandie 1932 ships Art Deco ships Blue Riband holders Maritime incidents in February 1942 Ocean liners Passenger ships of France Ships built in France Ship fires Ships of the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique Shipwrecks of the New York (state) coast Turbo-electric steamships United States home front during World War II Transportation accidents in New York City

ocean liner

An ocean liner is a passenger ship primarily used as a form of transportation across seas or oceans. Ocean liners may also carry cargo or mail, and may sometimes be used for other purposes (such as for pleasure cruises or as hospital ships).

C ...

built in Saint-Nazaire

Saint-Nazaire (; ; Gallo: ''Saint-Nazère/Saint-Nazaer'') is a commune in the Loire-Atlantique department in western France, in traditional Brittany.

The town has a major harbour on the right bank of the Loire estuary, near the Atlantic Ocean ...

, France, for the French Line ''Compagnie Générale Transatlantique

The Compagnie Générale Transatlantique (CGT, and commonly named "Transat"), typically known overseas as the French Line, was a French shipping company. Established in 1855 by the brothers Émile and Issac Péreire under the name ''Compagnie ...

'' (CGT). She entered service in 1935 as the largest and fastest passenger ship afloat, crossing the Atlantic in a record 4.14 days, and remains the most powerful steam turbo-electric

A turbo-electric transmission uses electric generators to convert the mechanical energy of a turbine (steam or gas) into electric energy, which then powers electric motors and converts back into mechanical energy that power the driveshafts.

Tur ...

-propelled passenger ship ever built.

''Normandie''s novel design and lavish interiors led many to consider her the greatest of ocean liners,''Floating Palaces.'' (1996) A&E. TV Documentary. Narrated by Fritz Weaver and she would go on to heavily influence the French arm of the Streamline Moderne

Streamline Moderne is an international style of Art Deco architecture and design that emerged in the 1930s. Inspired by aerodynamic design, it emphasized curving forms, long horizontal lines, and sometimes nautical elements. In industrial desig ...

design movement (called the ''style paquebot'', or "ocean liner style"). Despite this, she was not a commercial success and relied partly on government subsidy to operate. During service as the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the f ...

of the CGT, she made 139 westbound transatlantic crossing

Transatlantic crossings are passages of passengers and cargo across the Atlantic Ocean between Europe or Africa and the Americas. The majority of passenger traffic is across the North Atlantic between Western Europe and North America. Centuri ...

s from her home port of Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, ver ...

to New York City. ''Normandie'' held the Blue Riband

The Blue Riband () is an unofficial accolade given to the passenger liner crossing the Atlantic Ocean in regular service with the record highest average speed. The term was borrowed from horse racing and was not widely used until after 1910 ...

for the fastest transatlantic crossing at several points during her service career, during which the was her main rival.

During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, ''Normandie'' was seized by U.S. authorities at New York and renamed USS ''Lafayette''. In 1942, while being converted to a troopship

A troopship (also troop ship or troop transport or trooper) is a ship used to carry soldiers, either in peacetime or wartime. Troopships were often drafted from commercial shipping fleets, and were unable land troops directly on shore, typicall ...

, the liner caught fire and capsized onto her port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as ...

side and came to rest, half submerged, on the bottom of the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between Ne ...

at Pier 88 (the site of the current New York Passenger Ship Terminal

The Manhattan Cruise Terminal, formerly known as the New York Passenger Ship Terminal or Port Authority Passenger Ship Terminal is a ship terminal for ocean-going passenger ships in Hell's Kitchen, Manhattan, New York City.

History

The New Y ...

). Although salvaged at great expense, restoration was deemed too costly and she was scrapped in October 1946.

Origins

The origins of ''Normandie'' can be traced to the 1920s, when the U.S. put restrictions on immigration, greatly reducing the traditional market for steerage-class passengers from Europe, and placing a new emphasis on upper-class tourists, largely Americans, many of them wanting to escape prohibition. Companies likeCunard

Cunard () is a British shipping and cruise line based at Carnival House at Southampton, England, operated by Carnival UK and owned by Carnival Corporation & plc. Since 2011, Cunard and its three ships have been registered in Hamilton, Ber ...

and the White Star Line

The White Star Line was a British shipping company. Founded out of the remains of a defunct packet company, it gradually rose up to become one of the most prominent shipping lines in the world, providing passenger and cargo services between ...

planned to build their own superliners to rival newer ships of the day; such vessels included the record-breaking and , both German. The French Line ''Compagnie Générale Transatlantique

The Compagnie Générale Transatlantique (CGT, and commonly named "Transat"), typically known overseas as the French Line, was a French shipping company. Established in 1855 by the brothers Émile and Issac Péreire under the name ''Compagnie ...

'' (CGT) began to plan its own superliner.

The CGT's flagship was the , which had modern Art Deco

Art Deco, short for the French ''Arts Décoratifs'', and sometimes just called Deco, is a style of visual arts, architecture, and product design, that first appeared in France in the 1910s (just before World War I), and flourished in the Unit ...

interiors but a conservative hull design. The designers intended their new superliner to be similar to earlier French Line ships. Then they were approached by Vladimir Yourkevitch

Vladimir Yourkevitch (russian: Владимир Иванович Юркевич, also spelled Yourkevich, 1885 in Moscow – December 13, 1964) was a Russian naval engineer, and a designer of the ocean liner SS ''Normandie''. He worked in R ...

, a former ship architect for the Imperial Russian Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy () operated as the navy of the Russian Tsardom and later the Russian Empire from 1696 to 1917. Formally established in 1696, it lasted until dissolved in the wake of the February Revolution of 1917. It developed from ...

who had emigrated to France after the 1917 revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of governme ...

. Yourkevitch's ideas included a slanting clipper-like bow and a bulbous forefoot beneath the waterline, in combination with a slim hydrodynamic hull. His concepts worked wonderfully in scale models, confirming the design's performance advantages. The French engineers were impressed and asked Yourkevitch to join their project. He also approached Cunard with his ideas, but was rejected because the bow was deemed too radical.

The CGT commissioned artists to create posters and publicity for the liner. One of the most famous posters was by Adolphe Mouron Cassandre

Cassandre, pseudonym of Adolphe Jean-Marie MouronNotice d'autorité personne ...

, another Russian emigrant to France. Another poster, by Albert Sébille, showed the interior layout in a cutaway diagram long. This poster is displayed in the ''Musée national de la Marine

The Musée national de la Marine (National Navy Museum) is a maritime museum located in the Palais de Chaillot, Trocadéro, in the 16th arrondissement of Paris. It has annexes at Brest, Port-Louis, Rochefort ( Musée National de la Marine de ...

'' in Paris.

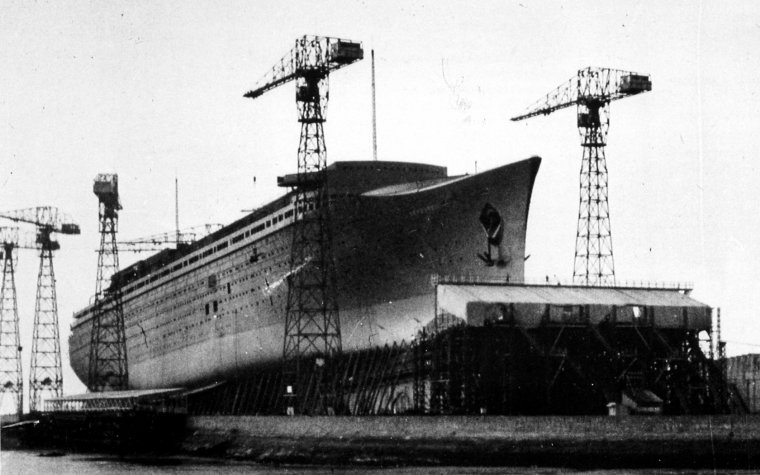

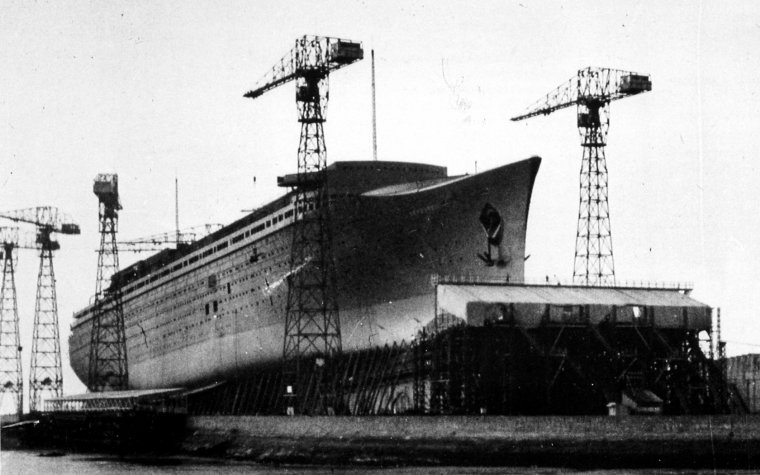

Construction and launch

Work by the ''Société Anonyme des Chantiers de Penhoët'' began on the unnamed flagship on 26 January 1931 at

Work by the ''Société Anonyme des Chantiers de Penhoët'' began on the unnamed flagship on 26 January 1931 at Saint-Nazaire

Saint-Nazaire (; ; Gallo: ''Saint-Nazère/Saint-Nazaer'') is a commune in the Loire-Atlantique department in western France, in traditional Brittany.

The town has a major harbour on the right bank of the Loire estuary, near the Atlantic Ocean ...

, soon after the stock market crash of 1929

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Great Crash, was a major American stock market crash that occurred in the autumn of 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange colla ...

. While the French continued construction, the competing White Star Line ship (intended as ''Oceanic'', and started before the crash) was cancelled and Cunard's was put on hold. French builders also ran into difficulty and had to ask for government money; this subsidy was questioned in the press. Still, the ship's construction was followed by newspapers and national interest was deep, as she was designed to represent France in the nation-state contest of the great liners and was built in a French shipyard using French parts.

The growing hull in Saint-Nazaire had no formal designation except "T-6" ("T" for "Transat", an alternate name for the French Line, and "6" for "6th"), the contract name. Many names were suggested including ''Doumer'', after Paul Doumer

Joseph Athanase Doumer, commonly known as Paul Doumer (; 22 March 18577 May 1932), was the President of France from 13 June 1931 until his assassination on 7 May 1932.

Biography

Joseph Athanase Doumer was born in Aurillac, in the Cantal ''dépa ...

, the recently assassinated President of France

The president of France, officially the president of the French Republic (french: Président de la République française), is the executive head of state of France, and the commander-in-chief of the French Armed Forces. As the presidency is ...

; and originally, ''La Belle France.'' Finally ''Normandie'' was chosen. In France, boat prefixes properly depend on the boat name's gender, but non-sailors mostly use the masculine form, inherited from the French terms for boat, which can be "''paquebot''", "''navire''", "''bateau''", or "''bâtiment''", but English speakers refer to boats as feminine ("she's a beauty") and the GCT carried many rich American customers. The CGT wrote that their boat was to be called simply "''Normandie''", preceded by neither "le" nor "la" (French masculine/feminine for "the") to avoid any confusion.

On 29 October 1932 – three years to the day after the stock market crash – ''Normandie'' was launched in front of 200,000 spectators. The 27,567-ton hull that slid into the river Loire

The Loire (, also ; ; oc, Léger, ; la, Liger) is the longest river in France and the 171st longest in the world. With a length of , it drains , more than a fifth of France's land, while its average discharge is only half that of the Rhôn ...

was the largest launched and the wave washed up the shoreline and over several hundred spectators, but with no injury. The ship was dedicated by Madame Marguerite Lebrun

Marguerite Jeanne Emilie Marguerite Lebrun ( Nivoit; October 12, 1878 - October 25, 1947) was the wife of Albert Lebrun, who was President of France from 1932 to 1940. She was a right wing activist and the founder of École des parents ("''Pare ...

, wife of Albert Lebrun

Albert François Lebrun (; 29 August 1871 – 6 March 1950) was a French politician, President of France from 1932 to 1940. He was the last president of the Third Republic. He was a member of the centre-right Democratic Republican Alliance (AR ...

, the President of France. She was outfitted until early 1935, her interiors, funnels, engines, and other fittings put in to make her into a working vessel. Finally, in May 1935, ''Normandie'' was ready for trials, which were watched by reporters. The superiority of Yourkevitch's hull was visible: hardly a wave was created off the bulbous bow. The ship reached a top speed of and performed an emergency stop from that speed in .

In addition to hull design which let her attain speed at far less power than other big liners, ''Normandie'' had a turbo-electric transmission

A turbo-electric transmission uses electric generators to convert the mechanical energy of a turbine (steam or gas) into electric energy, which then powers electric motors and converts back into mechanical energy that power the driveshafts. ...

, with turbo-generators and electric propulsion motors built by Alsthom

Alstom SA is a French multinational rolling stock manufacturer operating worldwide in rail transport markets, active in the fields of passenger transportation, signalling, and locomotives, with products including the AGV, TGV, Eurostar, Avelia ...

of Belfort

Belfort (; archaic german: Beffert/Beffort) is a city in the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region in Northeastern France, situated between Lyon and Strasbourg, approximately from the France–Switzerland border. It is the prefecture of the Terr ...

. The CGT chose turbo-electric transmission for the ability to use full power in reverse, and because, according to CGT officials, it was quieter and more easily controlled and maintained. The engine installation was heavier than conventional turbines and slightly less efficient at high speed but allowed all propellers to operate even if one engine was not running. This system also made it possible to eliminate astern turbines. An early form of radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, w ...

was installed to prevent collisions. The rudder frame, including the 125-ton cast steel connecting rod, was produced by Škoda Works

The Škoda Works ( cs, Škodovy závody, ) was one of the largest European industrial conglomerates of the 20th century, founded by Czech engineer Emil Škoda in 1859 in Plzeň, then in the Kingdom of Bohemia, Austrian Empire. It is the prede ...

in Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

.

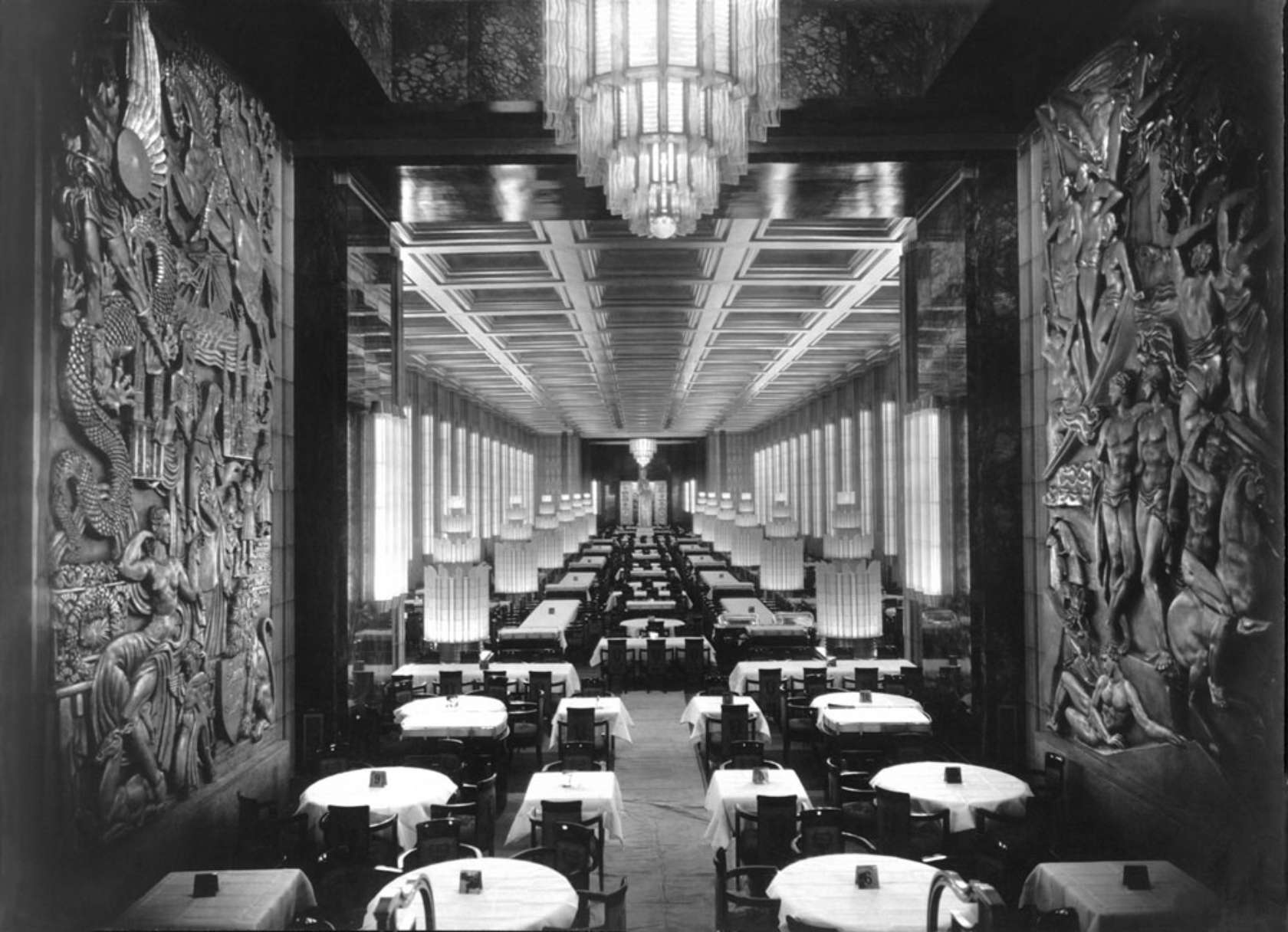

Interior

''Normandie''s luxurious interiors were designed inArt Déco

Art Deco, short for the French ''Arts Décoratifs'', and sometimes just called Deco, is a style of visual arts, architecture, and Industrial design, product design, that first appeared in France in the 1910s (just before World War I), and flour ...

and Streamline Moderne

Streamline Moderne is an international style of Art Deco architecture and design that emerged in the 1930s. Inspired by aerodynamic design, it emphasized curving forms, long horizontal lines, and sometimes nautical elements. In industrial desig ...

style by architect Pierre Patout

Pierre Patout (1879-1965) was a French architect and interior designer, who was one of the major figures of the Art Deco movement, as well as a pioneer of Streamline Moderne design. His works included the design of the main entrance and the Pavil ...

, one of the founders of the Art Deco

Art Deco, short for the French ''Arts Décoratifs'', and sometimes just called Deco, is a style of visual arts, architecture, and product design, that first appeared in France in the 1910s (just before World War I), and flourished in the Unit ...

style. Many sculptures and wall paintings made allusions to Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

, the province of France for which the ship was named. Drawings and photographs show a series of vast public rooms of great elegance. Her voluminous interior spaces were made possible by having the funnel uptakes split to pass along the sides of the ship, rather than straight upward. French architect Roger-Henri Expert

Roger-Henri Expert (18 April 1882 – 13 April 1955) was a French architect.

Life

The son of a merchant, Expert first studied painting at the École des beaux-arts in Bordeaux, then from 1906 attended the École nationale supérieure des Bea ...

was in charge of the overall decorative scheme.

Most of the public space was devoted to first-class passengers, including the dining room, first-class lounge, grill room, first-class swimming pool, theatre and winter garden

A winter garden is a kind of garden maintained in wintertime.

History

The origin of the winter garden dates back to the 17th to 19th centuries where European nobility would construct large conservatories that would house tropical and subtro ...

. The first-class swimming pool featured staggered depths, with a shallow training beach for children. The children's dining room was decorated by Jean de Brunhoff

Jean de Brunhoff (; 9 December 1899 – 16 October 1937) was a French writer and illustrator remembered best for creating the Babar series of children's books concerning a fictional elephant, the first of which was published in 1931.

Early life

...

, who covered the walls with Babar the Elephant

Babar the Elephant (, ; ) is an elephant character who first appeared in 1931 in the French children's book ''Histoire de Babar'' by Jean de Brunhoff.

The book is based on a tale that Brunhoff's wife, Cécile, had invented for their children. ...

and his ''entourage''.

The interiors were filled with grand perspectives, spectacular entryways, and long, wide staircases. First-class suites were given unique designs by select designers. The most luxurious accommodations were the Deauville and Trouville apartments, featuring dining rooms, baby grand pianos, multiple bedrooms, and private decks.

''Normandie''s first-class dining hall was the largest room afloat. At , it was longer than the

''Normandie''s first-class dining hall was the largest room afloat. At , it was longer than the Hall of Mirrors

The Hall of Mirrors (french: Grande Galerie, Galerie des Glaces, Galerie de Louis XIV) is a grand Baroque style gallery and one of the most emblematic rooms in the royal Palace of Versailles near Paris, France. The grandiose ensemble of the h ...

at the Palace of Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, u ...

, wide, and high. Passengers entered through doors adorned with bronze medallions by artist Raymond Subes. The room could seat 700 at 157 tables, with ''Normandie'' serving as a floating promotion for the most sophisticated French cuisine

French cuisine () is the cooking traditions and practices from France. It has been influenced over the centuries by the many surrounding cultures of Spain, Italy, Switzerland, Germany and Belgium, in addition to the food traditions of the r ...

of the period. As no natural light could enter it was illuminated by twelve tall pillars of Lalique

Lalique is a French glassmaker, founded by renowned glassmaker and jeweller René Lalique in 1888. Lalique is best known for producing glass art, including perfume bottles, vases, and hood ornaments during the early twentieth century. Following t ...

glass flanked by 38 matching columns along the walls. These, with chandeliers hung at each end of the room, earned the ''Normandie'' the nickname "Ship of Light" (similar to Paris as the "City of Light").

A popular feature was the café grill, which would be transformed into a nightclub

A nightclub (music club, discothèque, disco club, or simply club) is an entertainment venue during nighttime comprising a dance floor, lightshow, and a stage for live music or a disc jockey (DJ) who plays recorded music.

Nightclubs gener ...

. Adjoining the café grill was the first-class smoking room, which was paneled in large murals depicting ancient Egyptian life. The ship also had indoor and outdoor pools, a chapel, and a theatre which could double as a stage and cinema.

The machinery of ''Normandie''s top deck and forecastle

The forecastle ( ; contracted as fo'c'sle or fo'c's'le) is the upper deck of a sailing ship forward of the foremast, or, historically, the forward part of a ship with the sailors' living quarters. Related to the latter meaning is the phrase " b ...

was integrated within the ship, concealing it and releasing nearly all the exposed deck space for passengers. As such it was the only ocean liner to have a regulation-sized open air tennis court

A tennis court is the venue where the sport of tennis is played. It is a firm rectangular surface with a low net stretched across the centre. The same surface can be used to play both doubles and singles matches. A variety of surfaces can be ...

on board. The air conditioner units were concealed along with the kennels inside the third, dummy, funnel.

Career

''Normandie''s maiden voyage was on 29 May 1935. Fifty thousand saw her off at Le Havre on what was hoped would be a record-breaking crossing. She reached New York City after four days, three hours and two minutes, taking away theBlue Riband

The Blue Riband () is an unofficial accolade given to the passenger liner crossing the Atlantic Ocean in regular service with the record highest average speed. The term was borrowed from horse racing and was not widely used until after 1910 ...

from the Italian liner . This brought great pride for the French, who had not won the distinction before. Under the command of Captain René Pugnet, ''Normandie''s average on the maiden voyage was around and on the eastbound crossing to France, she averaged over , breaking records in both directions.

During the maiden voyage, the CGT refused to predict that their ship would win the Blue Riband. However, by the time the ship reached New York, medallions of the Blue Riband victory, made in France, were delivered to passengers and the ship flew a blue pennant. An estimated 100,000 spectators lined New York Harbor for ''Normandie''s arrival. All passengers were presented with a medal celebrating the occasion on behalf of the CGT.

''Normandie'' had a successful year but ''Queen Mary'', Cunard White Star Line

Cunard-White Star Line, Ltd, was a British shipping line which existed between 1934 and 1949.

History

The company was created to control the joint shipping assets of the Cunard Line and the White Star Line after both companies experienced fin ...

's superliner, entered service in the summer of 1936. Cunard White Star said ''Queen Mary'' would surpass 80,000 tons. At 79,280 tons, ''Normandie'' would no longer be the world's largest. The CGT increased ''Normandie''s size, mainly through the addition of an enclosed tourist lounge on the aft boat deck. Following these and other alterations, she measured 83,423 gross register tons. Exceeding ''Queen Mary'' by 2,000 tons, she would soon become the world's largest in terms of overall measured gross registered tonnage and length once again, claiming it off ''Queen Mary'' who only held it for a short amount of time.

On 22 June 1936, a Blackburn Baffin

The Blackburn B-5 Baffin biplane torpedo bomber designed and produced by the British aircraft manufacturer Blackburn Aircraft. It was a development of the Ripon, the chief change being that a 545 hp (406 kW) Bristol Pegasus I.MS radi ...

, ''S5162'' of A Flight, RAF Gosport

Gosport ( ) is a town and non-metropolitan borough on the south coast of Hampshire, South East England. At the 2011 Census, its population was 82,662. Gosport is situated on a peninsula on the western side of Portsmouth Harbour, opposite th ...

, flown by Lt Guy Kennedy Horsey on torpedo-dropping practice, buzzed ''Normandie'' off Ryde Pier

Ryde Pier is an early 19th century pier serving the town of Ryde, on the Isle of Wight, off the south coast of England. It is the world's oldest seaside pleasure pier. Ryde Pier Head railway station is at the sea end of the pier, and Ryde Espla ...

and collided with a derrick

A derrick is a lifting device composed at minimum of one guyed mast, as in a gin pole, which may be articulated over a load by adjusting its guys. Most derricks have at least two components, either a guyed mast or self-supporting tower, an ...

which was transferring a motor car belonging to Arthur Evans

Sir Arthur John Evans (8 July 1851 – 11 July 1941) was a British archaeologist and pioneer in the study of Aegean civilization in the Bronze Age. He is most famous for unearthing the palace of Knossos on the Greek island of Crete. Based o ...

, MP, onto a barge

Barge nowadays generally refers to a flat-bottomed inland waterway vessel which does not have its own means of mechanical propulsion. The first modern barges were pulled by tugs, but nowadays most are pushed by pusher boats, or other vessels. ...

alongside the ship. The aircraft crashed onto ''Normandie''s bow. The pilot was taken off by tender, but the wreckage of the aircraft remained on board ''Normandie'' as she had to sail due to the tide. It was carried to Le Havre. A salvage team from the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

later removed the wreckage. Horsey was court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of mem ...

led and found guilty on two charges. Evans' car was wrecked in the accident, which was brought up in Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. ...

.

In August 1936, ''Queen Mary'' captured the Blue Riband, averaging , starting a fierce rivalry. ''Normandie'' held the size record until the arrival of (83,673 gross register tons) in 1940.

During refit, ''Normandie'' was modified to reduce vibration. Her three-bladed screws were replaced with four-bladed ones, and structural modifications were made to her lower aft section. These modifications reduced vibration at speed. In July 1937 she regained the Blue Riband, but ''Queen Mary'' took it back next year. After this the captain of ''Normandie'' sent a message saying, "Bravo to the ''Queen Mary'' until next time!" This rivalry could have gone on into the 1940s, but was ended by the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

.

''Normandie'' carried distinguished passengers, including the authors Colette

Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette (; 28 January 1873 – 3 August 1954), known mononymously as Colette, was a French author and woman of letters. She was also a mime, actress, and journalist. Colette is best known in the English-speaking world for her ...

and Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. His economical and understated style—which he termed the iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century fic ...

; the wife of French President Albert Lebrun

Albert François Lebrun (; 29 August 1871 – 6 March 1950) was a French politician, President of France from 1932 to 1940. He was the last president of the Third Republic. He was a member of the centre-right Democratic Republican Alliance (AR ...

; songwriters Noël Coward

Sir Noël Peirce Coward (16 December 189926 March 1973) was an English playwright, composer, director, actor, and singer, known for his wit, flamboyance, and what ''Time (magazine), Time'' magazine called "a sense of personal style, a combina ...

and Irving Berlin

Irving Berlin (born Israel Beilin; yi, ישראל ביילין; May 11, 1888 – September 22, 1989) was a Russian-American composer, songwriter and lyricist. His music forms a large part of the Great American Songbook.

Born in Imperial Russ ...

; and Hollywood celebrities such as Fred Astaire

Fred Astaire (born Frederick Austerlitz; May 10, 1899 – June 22, 1987) was an American dancer, choreographer, actor, and singer. He is often called the greatest dancer in Hollywood film history.

Astaire's career in stage, film, and tele ...

, Marlene Dietrich

Marie Magdalene "Marlene" DietrichBorn as Maria Magdalena, not Marie Magdalene, according to Dietrich's biography by her daughter, Maria Riva ; however Dietrich's biography by Charlotte Chandler cites "Marie Magdalene" as her birth name . (, ; ...

, Walt Disney

Walter Elias Disney (; December 5, 1901December 15, 1966) was an American animator, film producer and entrepreneur. A pioneer of the American animation industry, he introduced several developments in the production of cartoons. As a film p ...

, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr

Douglas Elton Fairbanks Jr., (December 9, 1909 – May 7, 2000) was an American actor, producer and decorated naval officer of World War II. He is best known for starring in such films as ''The Prisoner of Zenda'' (1937), '' Gunga Din'' (1939) ...

, and James Stewart. She also carried the von Trapp family singers of ''The Sound of Music

''The Sound of Music'' is a musical with music by Richard Rodgers, lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II, and a book by Howard Lindsay and Russel Crouse. It is based on the 1949 memoir of Maria von Trapp, ''The Story of the Trapp Family Singers''. ...

'' from New York to Southampton

Southampton () is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire, S ...

in 1938, and from Southampton, the family went to Scandinavia for a tour before returning to the U.S.

Planned running mate – SS ''Bretagne''

While ''Normandie'' rarely was occupied at over 60% of her capacity, her finances were such that she did not require government subsidies every year. She never repaid any of the loans that made her construction possible. The CGT considered a sister ship, SS ''Bretagne'', which was to be longer and larger. There were two competing designs for this ship one conservative, one radical. The conservative design was essentially ''Normandie'' with two funnels, possibly larger as well. The radical one was from ''Normandie''s designer, Vladimir Yourkevitch, and was super-streamlined with twin, side-by-side funnels just aft of the bridge. The more conservative design won, but the outbreak of the war halted the plan indefinitely.Popularity

Although ''Normandie'' was a critical success in her design and decor, ultimately North Atlantic passengers flocked to the more traditional ''Queen Mary''. Two of the ship's greatest attributes, in reality, turned out to be two of her biggest faults.

Part of ''Normandie''s problem lay in the fact that the majority of her passenger space was devoted solely to first class, which could carry up to 848 people. Less space and consideration were given to second and tourist class, which numbered only 670 and 454 passengers respectively. As a result, the consensus among North Atlantic passengers was that she was primarily a ship for the rich and famous. In contrast, in ''Queen Mary'', Cunard White Star had placed just as much emphasis on decor, space, and accommodation in second and tourist class as in first class. Thus ''Queen Mary'' accommodated American tourists, who had become numerous in the 1920s and 1930s. Many of these passengers could not afford first-class passage yet wanted to travel with much of the same comfort as those experienced in first. As a result, second and tourist class became a major cash source for shipping companies at that time. ''Queen Mary'' would accommodate these trends and subsequently the liner achieved greater popularity among North Atlantic travellers during the late thirties.

Another of the CGT's greatest triumphs also turned out to be one of ''Normandie''s greatest flaws: her decor. The ship's slick and modern Art Déco interiors proved to be somewhat intimidating and uncomfortable for her travellers, with some claiming that interiors gave them migraines. It was also here that ''Queen Mary'' triumphed over her French rival. Although also decorated in an Art Déco style, ''Queen Mary'' was more restrained in her appointments and was not as radical as ''Normandie'', and proved ultimately to be more popular with travellers.

Part of ''Normandie''s problem lay in the fact that the majority of her passenger space was devoted solely to first class, which could carry up to 848 people. Less space and consideration were given to second and tourist class, which numbered only 670 and 454 passengers respectively. As a result, the consensus among North Atlantic passengers was that she was primarily a ship for the rich and famous. In contrast, in ''Queen Mary'', Cunard White Star had placed just as much emphasis on decor, space, and accommodation in second and tourist class as in first class. Thus ''Queen Mary'' accommodated American tourists, who had become numerous in the 1920s and 1930s. Many of these passengers could not afford first-class passage yet wanted to travel with much of the same comfort as those experienced in first. As a result, second and tourist class became a major cash source for shipping companies at that time. ''Queen Mary'' would accommodate these trends and subsequently the liner achieved greater popularity among North Atlantic travellers during the late thirties.

Another of the CGT's greatest triumphs also turned out to be one of ''Normandie''s greatest flaws: her decor. The ship's slick and modern Art Déco interiors proved to be somewhat intimidating and uncomfortable for her travellers, with some claiming that interiors gave them migraines. It was also here that ''Queen Mary'' triumphed over her French rival. Although also decorated in an Art Déco style, ''Queen Mary'' was more restrained in her appointments and was not as radical as ''Normandie'', and proved ultimately to be more popular with travellers.

As a result, ''Normandie'' at many times throughout her service history carried less than half her full complement of passengers. Her German rivals ''Bremen'' and ''Europa'', and Italian rivals ''Rex'' and also suffered from this problem; despite their innovative designs and luxurious interiors, they made little profit for their respective companies. Contributing to this were international boycotts against

As a result, ''Normandie'' at many times throughout her service history carried less than half her full complement of passengers. Her German rivals ''Bremen'' and ''Europa'', and Italian rivals ''Rex'' and also suffered from this problem; despite their innovative designs and luxurious interiors, they made little profit for their respective companies. Contributing to this were international boycotts against Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG),, is a country in Central Europe. It is the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany lies between the Baltic and North Sea to the north and the Alps to the sou ...

and Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

as the European geopolitical situation deteriorated through the 1930s. The Italian liners relied heavily on government subsidies, while the German Lloyd liners never received funding. In comparison, ''Normandie'' did not require government subsidies in service, with her income covering not only her operating expenses but generating revenue of 158,000,000 franc

The franc is any of various units of currency. One franc is typically divided into 100 centimes. The name is said to derive from the Latin inscription ''francorum rex'' (King of the Franks) used on early French coins and until the 18th centur ...

s.

In contrast, Cunard White Star's '' Britannic III'', '' Georgic II'', and much older ''Aquitania

Gallia Aquitania ( , ), also known as Aquitaine or Aquitaine Gaul, was a province of the Roman Empire. It lies in present-day southwest France, where it gives its name to the modern region of Aquitaine. It was bordered by the provinces of Galli ...

'', along with the Holland America Line

Holland America Line is an American-owned cruise line, a subsidiary of Carnival Corporation & plc headquartered in Seattle, Washington, United States.

Holland America Line was founded in Rotterdam, Netherlands, and from 1873 to 1989, it operated ...

's , were among the few North Atlantic liners to make a profit, carrying the lion's share of passengers in the years preceding the Second World War.

World War II

The outbreak of the war found ''Normandie'' in New York Harbor. Looming hostilities in Europe had compelled ''Normandie'' to seek haven in the U.S. The federal governmentinterned

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

her on 3 September 1939, the same day France declared war on Germany. Soon ''Queen Mary'', later refitted as a troopship

A troopship (also troop ship or troop transport or trooper) is a ship used to carry soldiers, either in peacetime or wartime. Troopships were often drafted from commercial shipping fleets, and were unable land troops directly on shore, typicall ...

, moored nearby. Then, two weeks later, ''Queen Elizabeth'' joined ''Queen Mary''. For five months, the three largest liners in the world were tied up side by side. ''Normandie'' remained in French hands, with French crewmembers on board, led by Captain Hervé Lehuédé, into the spring of 1940.

On 15 May 1940, during the Battle of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of French Third Rep ...

, the U.S. Treasury Department

The Department of the Treasury (USDT) is the national treasury and finance department of the federal government of the United States, where it serves as an executive department. The department oversees the Bureau of Engraving and Printing and t ...

detailed about 150 agents of the United States Coast Guard

The United States Coast Guard (USCG) is the maritime security, search and rescue, and law enforcement service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the country's eight uniformed services. The service is a maritime, military, mu ...

(USCG) to go aboard the ship and Manhattan's Pier 88 to defend it against possible sabotage

Sabotage is a deliberate action aimed at weakening a polity, effort, or organization through subversion, obstruction, disruption, or destruction. One who engages in sabotage is a ''saboteur''. Saboteurs typically try to conceal their identiti ...

. (At the time, U.S. law mandated the Coast Guard was a part of the Treasury during peacetime.) When the USCG became a part of the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

on 1 November 1941, ''Normandie''s USCG detail remained intact, mainly observing while the French crew maintained the vessel's boilers, machinery, and other equipment, including the fire-watch system. On 12 December 1941, five days after the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawa ...

, the USCG removed Captain Lehuédé and his crew and took possession of ''Normandie'' under the right of angary

Angary ('' la, jus angariae''; french: droit d'angarie''; german: Angarie''; from the Ancient Greek , ', "the office of an (courier or messenger)") is the right of a belligerent (most commonly, a government or other party in conflict) to seize and ...

, maintaining steam in the boilers and other activities on the idled vessel. However, the elaborate fire-watch system which ensured that any fire would be suppressed before it became a danger was abandoned.

''Lafayette'' conversion

On 20 December 1941, the Auxiliary Vessels Board officially recorded

On 20 December 1941, the Auxiliary Vessels Board officially recorded President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese f ...

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

's approval of ''Normandies transfer to the U.S. Navy. Plans called for the vessel to be turned into a troopship ("convoy unit loaded transport"). The Navy renamed her USS ''Lafayette'', in honor of both Marquis de la Fayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (, ), was a French aristocrat, freemason and military officer who fought in the American Revoluti ...

, the French general who fought on the Colonies

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state' ...

' behalf in the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolu ...

, and the alliance with France that made American independence possible. The name was a suggestion of J. P. "Jim" Warburg, advisory assistant to Colonel William J. Donovan

William Joseph "Wild Bill" Donovan (January 1, 1883 – February 8, 1959) was an American soldier, lawyer, intelligence officer and diplomat, best known for serving as the head of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursor to the Bu ...

, Coordinator of Information

The Office of the Coordinator of Information was an intelligence and propaganda agency of the United States Government, founded on July 11, 1941, by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, prior to U.S. involvement in the Second World War. It was intende ...

, which was passed through multiple channels including Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

Frank Knox

William Franklin Knox (January 1, 1874 – April 28, 1944) was an American politician, newspaper editor and publisher. He was also the Republican vice presidential candidate in 1936, and Secretary of the Navy under Franklin D. Roosevelt duri ...

; Admiral Harold R. Stark

Harold Rainsford Stark (November 12, 1880 – August 20, 1972) was an officer in the United States Navy during World War I and World War II, who served as the 8th Chief of Naval Operations from August 1, 1939 to March 26, 1942.

Early life a ...

, Chief of Naval Operations (CNO); and Rear Adm. Randall Jacobs, Chief of the Bureau of Navigation

The Bureau of Navigation, later the Bureau of Navigation and Steamboat Inspection and finally the Bureau of Marine Inspection and Navigation — not to be confused with the United States Navys Bureau of Navigation — was an agency of the United ...

. The name ''La Fayette'' (later universally and unofficially contracted to ''Lafayette'') was officially approved by the Secretary of the Navy on 31 December 1941, with the vessel classified as a transport, AP-53.

Earlier proposals included turning ''Lafayette'' into an aircraft carrier, but this was dropped in favor of immediate troop transport. The ship remained moored at Pier 88 for the conversion. A contract for her conversion to a troop transport was awarded to Robins Dry Dock and Repair Co., a subsidiary of Todd Shipyards

Todd or Todds may refer to:

Places

;Australia:

* Todd River, an ephemeral river

;United States:

* Todd Valley, California, also known as Todd, an unincorporated community

* Todd, Missouri, a ghost town

* Todd, North Carolina, an unincorporate ...

, on 27 December 1941. On that date, Capt. Clayton M. Simmers, the 3rd Naval District Materiel Officer, reported to the Bureau of Ships (BuShips) his estimate that the conversion work could be completed by 31 January 1942, and planning for the work proceeded on that basis.

Capt. Robert G. Coman reported as ''Lafayettes prospective commanding officer on 31 January 1942, overseeing a skeleton

A skeleton is the structural frame that supports the body of an animal. There are several types of skeletons, including the exoskeleton, which is the stable outer shell of an organism, the endoskeleton, which forms the support structure inside ...

engineering force numbering 458 men. The complicated nature and enormous size of the conversion effort prevented Coman's crew from adhering to the original schedule; crew familiarization with the vessel was an issue, and additional crew members were arriving to assist the effort. On 6 February 1942, a request for a two-week delay for the first sailing of ''Lafayette'', originally scheduled for 14 February, was submitted to the Assistant Chief of Naval Operations. On that day, a schedule extension was granted due to a design plan change: elements of the superstructure were to be removed to improve stability, in work that was expected to take another 60 to 90 days. However, on 7 February, orders came from Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

that the reduction of the top-hamper had been abandoned and ''Lafayette'' was to sail on 14 February as planned. This abrupt reversal necessitated a frantic resumption of conversion work, and captains Coman and Simmers scheduled 9 February meetings in New York and Washington to lobby for further clarification of conversion plans; ultimately, these meetings would never take place.

Fire and capsizing

At 14:30 on 9 February 1942, sparks from awelding torch

Principle of burn cutting

Oxy-fuel welding (commonly called oxyacetylene welding, oxy welding, or gas welding in the United States) and oxy-fuel cutting are processes that use fuel gases (or liquid fuels such as gasoline or petrol, diesel, ...

used by workman Clement Derrick ignited a stack of life vests filled with flammable kapok

Kapok may refer to:

*Kapok tree, several species

*Kapok fibre, made from ''Ceiba pentandra'', one of the kapok tree species

*Kampong Kapok, a Bruneian village

*Kapok (Guitar Brand)

Kapok fibre is a cotton-like plant fibre obtained from the seed ...

that had been stored in ''Lafayette''s first-class lounge. The flammable varnished woodwork had not yet been removed, and the fire spread rapidly. The ship had a very efficient fire protection system, but it had been disconnected during the conversion and its internal pumping system was deactivated. The New York City Fire Department

The New York City Fire Department, officially the Fire Department of the City of New York (FDNY), is an American department of the government of New York City that provides fire protection services, technical rescue/special operations services ...

's hoses, unfortunately, did not fit the ship's French inlets. Before the fire department arrived, approximately 15 minutes after fire broke out, all onboard crew were using manual means in a vain attempt to stop the blaze. A strong northwesterly wind blowing over ''Lafayette''s port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as ...

quarter swept the blaze forward, eventually consuming the three upper decks of the ship within an hour of the start of the conflagration. Capt. Coman, along with Capt. Simmers, arrived about 15:25 to see his huge prospective command in flames.

As firefighters on shore and in fire boats poured water on the blaze, ''Lafayette'' developed a dangerous list

A ''list'' is any set of items in a row. List or lists may also refer to:

People

* List (surname)

Organizations

* List College, an undergraduate division of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America

* SC Germania List, German rugby uni ...

to port due to water pumped into the seaward side by fireboats. Vladimir Yourkevitch

Vladimir Yourkevitch (russian: Владимир Иванович Юркевич, also spelled Yourkevich, 1885 in Moscow – December 13, 1964) was a Russian naval engineer, and a designer of the ocean liner SS ''Normandie''. He worked in R ...

, the ship's designer, arrived at the scene to offer expertise but was barred by harbor police. Yourkevitch's suggestion was to enter the vessel and open the sea-cocks. This would flood the lower decks and make her settle the few feet to the bottom. With the ship stabilised, water could be pumped into burning areas without the risk of capsizing

Capsizing or keeling over occurs when a boat or ship is rolled on its side or further by wave action, instability or wind force beyond the angle of positive static stability or it is upside down in the water. The act of recovering a vessel fr ...

. The suggestion was rejected by the commander of the 3rd Naval District

The naval district was a U.S. Navy military and administrative command ashore. Apart from Naval District Washington, the Districts were disestablished and renamed Navy Regions about 1999, and are now under Commander, Naval Installations Command ...

, Rear Admiral Adolphus Andrews

Adolphus Andrews (October 7, 1879 – June 19, 1948) was a decorated officer in the United States Navy with the rank of Vice Admiral. A Naval Academy graduate and veteran of three wars, he is most noted for his service as Commander, Eastern Sea ...

.

Between 17:45 and 18:00 on 9 February 1942, authorities considered the fire under control and began winding down operations until 20:00. Water entering ''Lafayette'' through submerged openings and flowing to the lower decks negated efforts to counter-flood, and her list gradually increased to port. Shortly after midnight, Rear Adm. Andrews ordered ''Lafayette'' abandoned. The ship continued to list, a process hastened by the 6,000 tons of water that had been sprayed on her. New York fire officials were concerned that the fire could spread to the nearby buildings. ''Lafayette'' eventually capsized during the mid watch (02:45) on 10 February, nearly crushing a fire boat, and came to rest on her port side at an angle of approximately 80 degrees. Recognising that his incompetence had caused the disaster, Rear Adm. Andrews ordered all pressmen barred from viewing the moment of capsize in an effort to lower the level of publicity.

One man died in the tragedy – Frank "Trent" Trentacosta, 36, of Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. Kings County is the most populous Administrative divisions of New York (state)#County, county in the State of New York, ...

, a member of the fire watch. Some 94 USCG and Navy sailors, including some from ''Lafayettes pre-commissioning crew and men assigned to the receiving ship ''Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a port, seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the county seat, seat of King County, Washington, King County, Washington (state), Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in bo ...

'', 38 fire fighters, and 153 civilians were treated for various injuries, burns, smoke inhalation

Smoke inhalation is the breathing in of harmful fumes (produced as by-products of combusting substances) through the respiratory tract. This can cause smoke inhalation injury (subtype of acute inhalation injury) which is damage to the respiratory ...

, and exposure.

''Saboteur'' (film)

The ruined ''Lafayette'' after the fire can be seen briefly in the film ''Saboteur

Sabotage is a deliberate action aimed at weakening a polity, effort, or organization through subversion, obstruction, disruption, or destruction. One who engages in sabotage is a ''saboteur''. Saboteurs typically try to conceal their identitie ...

'' (1942). The ship is not identified in the film, but the antagonist smiles when he sees it, suggesting that he was responsible. The film's director, Alfred Hitchcock

Sir Alfred Joseph Hitchcock (13 August 1899 – 29 April 1980) was an English filmmaker. He is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in the history of cinema. In a career spanning six decades, he directed over 50 featur ...

, later said that "the Navy raised hell" about the implication that their security was so poor. The eastern seaboard of the U.S. was being attacked by German U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare ro ...

s at the time of the film's release, but information was suppressed by the Navy.

Investigation and salvage

Enemy sabotage was widely suspected, but a congressional investigation in the wake of the sinking, chaired by

Enemy sabotage was widely suspected, but a congressional investigation in the wake of the sinking, chaired by Representative

Representative may refer to:

Politics

*Representative democracy, type of democracy in which elected officials represent a group of people

*House of Representatives, legislative body in various countries or sub-national entities

*Legislator, someon ...

Patrick Henry Drewry

Patrick Henry Drewry (May 24, 1875 – December 21, 1947) was a Virginia lawyer and Democratic politician who served in the United States House of Representatives and state senate.

Early life and education

Born in Petersburg, Virginia, as o ...

( D-Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography an ...

), concluded that the fire was accidental. The investigation found evidence of carelessness, rule violations, lack of coordination between the various parties on board, lack of clear command structure

A command hierarchy is a group of people who carry out orders based on others' authority within the group. It can be viewed as part of a power structure, in which it is usually seen as the most vulnerable and also the most powerful part.

Mili ...

during the fire, and a hasty, poorly-planned conversion effort.

Members of organized crime

Organized crime (or organised crime) is a category of transnational, national, or local groupings of highly centralized enterprises run by criminals to engage in illegal activity, most commonly for profit. While organized crime is generally tho ...

retrospectively claimed that they had sabotaged the vessel. It was alleged that arson

Arson is the crime of willfully and deliberately setting fire to or charring property. Although the act of arson typically involves buildings, the term can also refer to the intentional burning of other things, such as motor vehicles, wat ...

had been organized by mobster Anthony Anastasio

Anthony Anastasio (; born Antonio Anastasio, ; February 24, 1906 – March 1, 1963) was an Italian-American mobster and labor racketeer for the Gambino crime family who controlled the Brooklyn dockyards for over thirty years. He controlled Bro ...

, who was a power in the local longshoremen's union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

, to provide leverage

Leverage or leveraged may refer to:

*Leverage (mechanics), mechanical advantage achieved by using a lever

* ''Leverage'' (album), a 2012 album by Lyriel

*Leverage (dance), a type of dance connection

*Leverage (finance), using given resources to ...

for the release of mob boss Charles "Lucky" Luciano

Charles "Lucky" Luciano (, ; born Salvatore Lucania ; November 24, 1897 – January 26, 1962) was an Italian-born gangster who operated mainly in the United States. Luciano started his criminal career in the Five Points gang and was instrumenta ...

from prison. Luciano's end of the bargain would be to ensure that there would be no further "enemy" sabotage in the ports where the mob had strong influence with the unions.

In one of the largest and most expensive salvage operations of its kind, estimated at $5 million at the time, the ship was stripped of superstructure and righted on 7 August 1943. She was renamed ''Lafayette'' and reclassified as an aircraft and transport ferry, APV-4, on 15 September 1943 and placed in drydock

A dry dock (sometimes drydock or dry-dock) is a narrow basin or vessel that can be flooded to allow a load to be floated in, then drained to allow that load to come to rest on a dry platform. Dry docks are used for the construction, maintenance, ...

the following month. However, extensive damage to her hull, deterioration of her machinery, and the necessity for employing manpower on other more critical war projects prevented resumption of the conversion program, with the cost of restoring her determined to be too great. Her hulk remained in the Navy's custody through the end of the war.

''Lafayette'' was stricken from the Naval Vessel Register

The ''Naval Vessel Register'' (NVR) is the official inventory of ships and service craft in custody of or titled by the United States Navy. It contains information on ships and service craft that make up the official inventory of the Navy from t ...

on 11 October 1945 without having ever sailed under the U.S. flag. President Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Frankli ...

authorized her disposal in an Executive Order on 8 September 1946, and she was sold as scrap on 3 October 1946 to Lipsett, Inc., an American salvage company based in New York City, for US$

The United States dollar (symbol: $; code: USD; also abbreviated US$ or U.S. Dollar, to distinguish it from other dollar-denominated currencies; referred to as the dollar, U.S. dollar, American dollar, or colloquially buck) is the official ...

161,680 (approx. $1,997,000 in 2017 value). After neither the Navy nor French Line offered a plan to salvage her, Yourkevitch, the ship's original designer, proposed to cut the ship down and restore her as a mid-sized liner. This plan also failed to draw backing. She was cut up for scrap beginning in October 1946 at Port Newark

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Ha ...

, New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York (state), New York; on the ea ...

, and completely scrapped by 31 December 1948.

Legacy

Designer Marin-Marie gave an innovative line to ''Normandie'', a silhouette which influenced ocean liners over the decades, including ''Queen Mary 2

RMS ''Queen Mary 2'' (also referred to as the ''QM2'') is a British transatlantic crossing, transatlantic ocean liner. She has served as the flagship of Cunard Line since succeeding ''Queen Elizabeth 2'' in 2004. As of 2022, ''Queen Mary 2'' ...

''. The ambience of classic transatlantic liners like ''Normandie'' (and her chief rival, ''Queen Mary'') was the source of inspiration for Disney Cruise Line

Disney Cruise Line is a cruise line operation that is a subsidiary of The Walt Disney Company. The company was incorporated in 1996 as Magical Cruise Company Limited, through the first vessel, ''Disney Magic'' and is domiciled in London, England ...

's matching vessels, ''Disney Magic

''Disney Magic'' is the first cruise ship owned and operated by Disney Cruise Line, a subsidiary of The Walt Disney Company. She has 11 public decks, can accommodate 2,700 passengers in 875 staterooms, and has a crew of approximately 950. The in ...

,'' ''Disney Wonder

''Disney Wonder'' is a cruise ship operated by Disney Cruise Line. She was the second ship to join the Disney fleet on entering service in 1999. ''Disney Wonder'' is of the same class as . The other three ships in the fleet are the , , and . The ...

'', ''Disney Dream

The ''Disney Dream'' is the third cruise ship operated by Disney Cruise Line, part of The Walt Disney Company. She is the first of the ''Dream''-class. She currently sails three-day, four-day, and occasional five-day cruises to the Bahamas. The ...

'', and ''Disney Fantasy

''Disney Fantasy'' is the fourth cruise ship owned and operated by Disney Cruise Line, a subsidiary of The Walt Disney Company, which entered service in 2012. Her sister ship, '' Disney Dream'', was launched in 2011. ''Disney Fantasy'' is the se ...

''.

''Normandie'' also inspired the architecture and design of the Normandie Hotel

The Normandie Hotel is a historic building located in the Isleta de San Juan, in San Juan, Puerto Rico which opened on October 10, 1942 as a hotel. Its design was inspired by the French transatlantic passenger ship SS ''Normandie'' in addition t ...

in San Juan San Juan, Spanish for Saint John, may refer to:

Places Argentina

* San Juan Province, Argentina

* San Juan, Argentina, the capital of that province

* San Juan, Salta, a village in Iruya, Salta Province

* San Juan (Buenos Aires Underground), ...

, Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and Unincorporated ...

. The hotel's roof sign is one of the two signs that adorned the top deck of ''Normandie'' but were removed from it during an early refitting. It also inspired the nickname 'The Normandie' given to the International Savings Society Apartments in Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flowin ...

, one of the most fashionable residential buildings during the city's pre-revolutionary heyday and home to several stars of China's mid-20th century film industry. ''Normandie'' name also inspired that of The Normandy

The Normandy is a cooperative apartment building at 140 Riverside Drive, between 86th and 87th Streets, adjacent to Riverside Park on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. Designed by architect Emery Roth in a mixture of the Art ...

apartment building in New York City.

Items from ''Normandie'' were sold at a series of auctions after her demise, and many pieces are considered valuable Art Déco treasures today. The rescued items include the ten large dining-room door medallions and fittings, and some of the individual Jean Dupas

Jean Théodore Dupas (21 February 1882 – 6 September 1964) was a French painter, artist, designer, poster artist, and decorator in the Art Nouveau and Art Deco styles.

Life

Dupas was born in Bordeaux. He won the Prix de Rome for painting in ...

glass panels that formed the large murals mounted at the four corners of her Grand Salon. One entire corner is preserved at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City, colloquially "the Met", is the largest art museum in the Americas. Its permanent collection contains over two million works, divided among 17 curatorial departments. The main building at 100 ...

in New York. The dining room door medallions are now on the exterior doors of Our Lady of Lebanon Maronite Cathedral in Brooklyn.

Also surviving are some examples of the 24,000 pieces of crystal, some from the massive Lalique torchères that adorned her dining salon. Also extant are some of the room's table silverware, chairs, and gold-plated bronze table bases. Custom-designed suite and cabin furniture as well as original artwork and statues that decorated the ship, or were built for use by the CGT aboard ''Normandie'', also survive today.

The eight-foot-high, 1,000-pound bronze figural sculpture of a woman named "''La Normandie''", which was at the top of the grand stairway from the first class smoking room up to the grill room café, was found in a New Jersey scrapyard in 1954 and was purchased for the then-new

Also surviving are some examples of the 24,000 pieces of crystal, some from the massive Lalique torchères that adorned her dining salon. Also extant are some of the room's table silverware, chairs, and gold-plated bronze table bases. Custom-designed suite and cabin furniture as well as original artwork and statues that decorated the ship, or were built for use by the CGT aboard ''Normandie'', also survive today.

The eight-foot-high, 1,000-pound bronze figural sculpture of a woman named "''La Normandie''", which was at the top of the grand stairway from the first class smoking room up to the grill room café, was found in a New Jersey scrapyard in 1954 and was purchased for the then-new Fontainebleau Hotel

The Fontainebleau Miami Beach (also known as Fontainebleau Hotel) is a hotel in Miami Beach, Florida. Designed by Morris Lapidus, the luxury hotel opened in 1954. In 2007, the Fontainebleau Hotel was ranked ninety-third in the American Institute ...

in Miami Beach

Miami Beach is a coastal resort city in Miami-Dade County, Florida. It was incorporated on March 26, 1915. The municipality is located on natural and man-made barrier islands between the Atlantic Ocean and Biscayne Bay, the latter of which s ...

, Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, a ...

. It was first displayed outside in the parterre

A ''parterre'' is a part of a formal garden constructed on a level substrate, consisting of symmetrical patterns, made up by plant beds, low hedges or coloured gravels, which are separated and connected by paths. Typically it was the part of ...

gardens near the formal pool and later indoors near the then-Fontainebleau Hilton's spa. In 2001, the hotel sold the statue to Celebrity Cruises

Celebrity Cruises is a cruise line headquartered in Miami, Florida and a wholly owned subsidiary of Royal Caribbean Group. Celebrity Cruises was founded in 1988 by the Greece-based Chandris Group, and merged with Royal Caribbean Cruise Line ...

, which placed it in the main dining room of their new ship ''Celebrity Summit

GTS ''Celebrity Summit'' is a owned and operated by Celebrity Cruises and as such one of the first cruise ships to be powered by more environmentally friendly gas turbines. Originally named ''Summit'', she was renamed with the "Celebrity" prefix ...