RSA (cryptosystem) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The RSA (Rivest–Shamir–Adleman) cryptosystem is a public-key cryptosystem, one of the oldest widely used for secure data transmission. The initialism "RSA" comes from the surnames of Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir and Leonard Adleman, who publicly described the algorithm in 1977. An equivalent system was developed secretly in 1973 at Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), the British signals intelligence agency, by the English mathematician Clifford Cocks. That system was declassified in 1997.

In a public-key cryptosystem, the encryption key is public and distinct from the decryption key, which is kept secret (private).

An RSA user creates and publishes a public key based on two large

The idea of an asymmetric public-private key cryptosystem is attributed to Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman, who published this concept in 1976. They also introduced digital signatures and attempted to apply number theory. Their formulation used a shared-secret-key created from exponentiation of some number, modulo a prime number. However, they left open the problem of realizing a one-way function, possibly because the difficulty of factoring was not well-studied at the time. Moreover, like Diffie-Hellman, RSA is based on modular exponentiation.

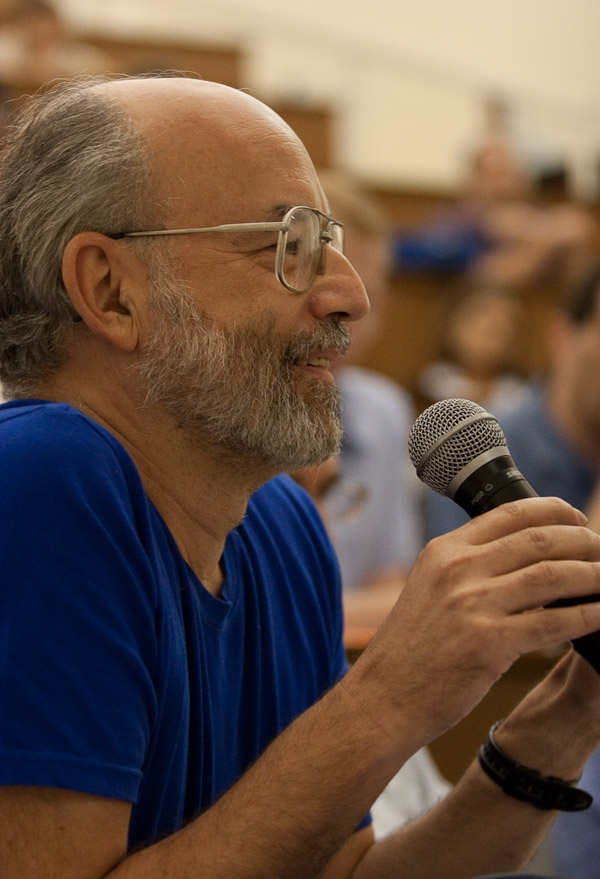

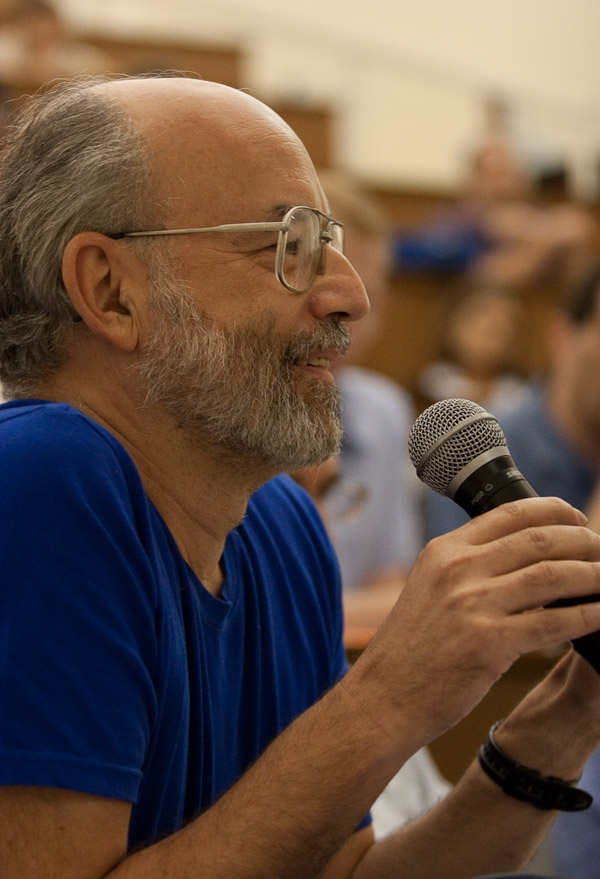

Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir, and Leonard Adleman at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology made several attempts over the course of a year to create a function that was hard to invert. Rivest and Shamir, as computer scientists, proposed many potential functions, while Adleman, as a mathematician, was responsible for finding their weaknesses. They tried many approaches, including " knapsack-based" and "permutation polynomials". For a time, they thought what they wanted to achieve was impossible due to contradictory requirements. In April 1977, they spent Passover at the house of a student and drank a good deal of wine before returning to their homes at around midnight. Rivest, unable to sleep, lay on the couch with a math textbook and started thinking about their one-way function. He spent the rest of the night formalizing his idea, and he had much of the paper ready by daybreak. The algorithm is now known as RSA the initials of their surnames in same order as their paper.

Clifford Cocks, an English mathematician working for the British intelligence agency Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), described a similar system in an internal document in 1973. However, given the relatively expensive computers needed to implement it at the time, it was considered to be mostly a curiosity and, as far as is publicly known, was never deployed. His ideas and concepts were not revealed until 1997 due to its top-secret classification.

Kid-RSA (KRSA) is a simplified, insecure public-key cipher published in 1997, designed for educational purposes. Kid-RSA gives insight into RSA and other public-key ciphers, analogous to simplified DES.

The idea of an asymmetric public-private key cryptosystem is attributed to Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman, who published this concept in 1976. They also introduced digital signatures and attempted to apply number theory. Their formulation used a shared-secret-key created from exponentiation of some number, modulo a prime number. However, they left open the problem of realizing a one-way function, possibly because the difficulty of factoring was not well-studied at the time. Moreover, like Diffie-Hellman, RSA is based on modular exponentiation.

Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir, and Leonard Adleman at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology made several attempts over the course of a year to create a function that was hard to invert. Rivest and Shamir, as computer scientists, proposed many potential functions, while Adleman, as a mathematician, was responsible for finding their weaknesses. They tried many approaches, including " knapsack-based" and "permutation polynomials". For a time, they thought what they wanted to achieve was impossible due to contradictory requirements. In April 1977, they spent Passover at the house of a student and drank a good deal of wine before returning to their homes at around midnight. Rivest, unable to sleep, lay on the couch with a math textbook and started thinking about their one-way function. He spent the rest of the night formalizing his idea, and he had much of the paper ready by daybreak. The algorithm is now known as RSA the initials of their surnames in same order as their paper.

Clifford Cocks, an English mathematician working for the British intelligence agency Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), described a similar system in an internal document in 1973. However, given the relatively expensive computers needed to implement it at the time, it was considered to be mostly a curiosity and, as far as is publicly known, was never deployed. His ideas and concepts were not revealed until 1997 due to its top-secret classification.

Kid-RSA (KRSA) is a simplified, insecure public-key cipher published in 1997, designed for educational purposes. Kid-RSA gives insight into RSA and other public-key ciphers, analogous to simplified DES.

FIPS 186-4

(Section B.3.1) may require that . Any "oversized" private exponents not meeting this criterion may always be reduced modulo to obtain a smaller equivalent exponent. Since any common factors of and are present in the factorisation of = = , it is recommended that and have only very small common factors, if any, besides the necessary 2. Note: The authors of the original RSA paper carry out the key generation by choosing and then computing as the modular multiplicative inverse of modulo , whereas most current implementations of RSA, such as those following PKCS#1, do the reverse (choose and compute ). Since the chosen key can be small, whereas the computed key normally is not, the RSA paper's algorithm optimizes decryption compared to encryption, while the modern algorithm optimizes encryption instead.

as The public key is . For a padded plaintext message , the encryption function is The private key is . For an encrypted ciphertext , the decryption function is For instance, in order to encrypt , one calculates To decrypt , one calculates Both of these calculations can be computed efficiently using the square-and-multiply algorithm for modular exponentiation. In real-life situations the primes selected would be much larger; in our example it would be trivial to factor (obtained from the freely available public key) back to the primes and . , also from the public key, is then inverted to get , thus acquiring the private key. Practical implementations use the Chinese remainder theorem to speed up the calculation using modulus of factors (mod ''pq'' using mod ''p'' and mod ''q''). The values , and , which are part of the private key are computed as follows: Here is how , and are used for efficient decryption (encryption is efficient by choice of a suitable and pair):

RFC 8017: PKCS #1: RSA Cryptography Specifications Version 2.2

*

Onur Aciicmez, Cetin Kaya Koc, Jean-Pierre Seifert: ''On the Power of Simple Branch Prediction Analysis''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Rsa Public-key encryption schemes Digital signature schemes

prime number

A prime number (or a prime) is a natural number greater than 1 that is not a Product (mathematics), product of two smaller natural numbers. A natural number greater than 1 that is not prime is called a composite number. For example, 5 is prime ...

s, along with an auxiliary value. The prime numbers are kept secret. Messages can be encrypted by anyone via the public key, but can only be decrypted by someone who knows the private key.

The security of RSA relies on the practical difficulty of factoring the product of two large prime number

A prime number (or a prime) is a natural number greater than 1 that is not a Product (mathematics), product of two smaller natural numbers. A natural number greater than 1 that is not prime is called a composite number. For example, 5 is prime ...

s, the " factoring problem". Breaking RSA encryption is known as the RSA problem. Whether it is as difficult as the factoring problem is an open question. There are no published methods to defeat the system if a large enough key is used.

RSA is a relatively slow algorithm. Because of this, it is not commonly used to directly encrypt user data. More often, RSA is used to transmit shared keys for symmetric-key cryptography, which are then used for bulk encryption–decryption.

History

The idea of an asymmetric public-private key cryptosystem is attributed to Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman, who published this concept in 1976. They also introduced digital signatures and attempted to apply number theory. Their formulation used a shared-secret-key created from exponentiation of some number, modulo a prime number. However, they left open the problem of realizing a one-way function, possibly because the difficulty of factoring was not well-studied at the time. Moreover, like Diffie-Hellman, RSA is based on modular exponentiation.

Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir, and Leonard Adleman at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology made several attempts over the course of a year to create a function that was hard to invert. Rivest and Shamir, as computer scientists, proposed many potential functions, while Adleman, as a mathematician, was responsible for finding their weaknesses. They tried many approaches, including " knapsack-based" and "permutation polynomials". For a time, they thought what they wanted to achieve was impossible due to contradictory requirements. In April 1977, they spent Passover at the house of a student and drank a good deal of wine before returning to their homes at around midnight. Rivest, unable to sleep, lay on the couch with a math textbook and started thinking about their one-way function. He spent the rest of the night formalizing his idea, and he had much of the paper ready by daybreak. The algorithm is now known as RSA the initials of their surnames in same order as their paper.

Clifford Cocks, an English mathematician working for the British intelligence agency Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), described a similar system in an internal document in 1973. However, given the relatively expensive computers needed to implement it at the time, it was considered to be mostly a curiosity and, as far as is publicly known, was never deployed. His ideas and concepts were not revealed until 1997 due to its top-secret classification.

Kid-RSA (KRSA) is a simplified, insecure public-key cipher published in 1997, designed for educational purposes. Kid-RSA gives insight into RSA and other public-key ciphers, analogous to simplified DES.

The idea of an asymmetric public-private key cryptosystem is attributed to Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman, who published this concept in 1976. They also introduced digital signatures and attempted to apply number theory. Their formulation used a shared-secret-key created from exponentiation of some number, modulo a prime number. However, they left open the problem of realizing a one-way function, possibly because the difficulty of factoring was not well-studied at the time. Moreover, like Diffie-Hellman, RSA is based on modular exponentiation.

Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir, and Leonard Adleman at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology made several attempts over the course of a year to create a function that was hard to invert. Rivest and Shamir, as computer scientists, proposed many potential functions, while Adleman, as a mathematician, was responsible for finding their weaknesses. They tried many approaches, including " knapsack-based" and "permutation polynomials". For a time, they thought what they wanted to achieve was impossible due to contradictory requirements. In April 1977, they spent Passover at the house of a student and drank a good deal of wine before returning to their homes at around midnight. Rivest, unable to sleep, lay on the couch with a math textbook and started thinking about their one-way function. He spent the rest of the night formalizing his idea, and he had much of the paper ready by daybreak. The algorithm is now known as RSA the initials of their surnames in same order as their paper.

Clifford Cocks, an English mathematician working for the British intelligence agency Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), described a similar system in an internal document in 1973. However, given the relatively expensive computers needed to implement it at the time, it was considered to be mostly a curiosity and, as far as is publicly known, was never deployed. His ideas and concepts were not revealed until 1997 due to its top-secret classification.

Kid-RSA (KRSA) is a simplified, insecure public-key cipher published in 1997, designed for educational purposes. Kid-RSA gives insight into RSA and other public-key ciphers, analogous to simplified DES.

Patent

A patent describing the RSA algorithm was granted to MIT on 20 September 1983: "Cryptographic communications system and method". From DWPI's abstract of the patent: A detailed description of the algorithm was published in August 1977, in Scientific American's Mathematical Games column. This preceded the patent's filing date of December 1977. Consequently, the patent had no legal standing outside theUnited States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

. Had Cocks' work been publicly known, a patent in the United States would not have been legal either.

When the patent was issued, terms of patent were 17 years. The patent was about to expire on 21 September 2000, but RSA Security released the algorithm to the public domain on 6 September 2000.

Operation

The RSA algorithm involves four steps: key generation, key distribution, encryption, and decryption. A basic principle behind RSA is the observation that it is practical to find three very large positive integers , , and , such that for all integers (), both and have the same remainder when divided by (they are congruent modulo ):However, when given only and , it is extremely difficult to find . The integers and comprise the public key, represents the private key, and represents the message. The modular exponentiation to and corresponds to encryption and decryption, respectively. In addition, because the two exponents can be swapped, the private and public key can also be swapped, allowing for message signing and verification using the same algorithm.Key generation

The keys for the RSA algorithm are generated in the following way: # Choose two largeprime number

A prime number (or a prime) is a natural number greater than 1 that is not a Product (mathematics), product of two smaller natural numbers. A natural number greater than 1 that is not prime is called a composite number. For example, 5 is prime ...

s and .

#* To make factoring harder, and should be chosen at random, be both large and have a large difference. For choosing them the standard method is to choose random integers and use a primality test until two primes are found.

#* and are kept secret.

# Compute .

#* is used as the modulus for both the public and private keys. Its length, usually expressed in bits, is the key length.

#* is released as part of the public key.

# Compute , where is Carmichael's totient function. Since , and since and are prime, , and likewise . Hence .

#* The may be calculated through the Euclidean algorithm, since .

#* is kept secret.

# Choose an integer such that and ; that is, and are coprime.

#* having a short bit-length and small Hamming weight results in more efficient encryption the most commonly chosen value for is . The smallest (and fastest) possible value for is 3, but such a small value for has been shown to be less secure in some settings.

#* is released as part of the public key.

# Determine as ; that is, is the modular multiplicative inverse of modulo .

#* This means: solve for the equation ; can be computed efficiently by using the extended Euclidean algorithm, since, thanks to and being coprime, said equation is a form of Bézout's identity, where is one of the coefficients.

#* is kept secret as the ''private key exponent''.

The ''public key'' consists of the modulus and the public (or encryption) exponent . The ''private key'' consists of the private (or decryption) exponent , which must be kept secret. , , and must also be kept secret because they can be used to calculate . In fact, they can all be discarded after has been computed.

In the original RSA paper, the Euler totient function is used instead of for calculating the private exponent . Since is always divisible by , the algorithm works as well. The possibility of using Euler totient function results also from Lagrange's theorem applied to the multiplicative group of integers modulo ''pq''. Thus any satisfying also satisfies . However, computing modulo will sometimes yield a result that is larger than necessary (i.e. ). Most of the implementations of RSA will accept exponents generated using either method (if they use the private exponent at all, rather than using the optimized decryption method based on the Chinese remainder theorem described below), but some standards such aFIPS 186-4

(Section B.3.1) may require that . Any "oversized" private exponents not meeting this criterion may always be reduced modulo to obtain a smaller equivalent exponent. Since any common factors of and are present in the factorisation of = = , it is recommended that and have only very small common factors, if any, besides the necessary 2. Note: The authors of the original RSA paper carry out the key generation by choosing and then computing as the modular multiplicative inverse of modulo , whereas most current implementations of RSA, such as those following PKCS#1, do the reverse (choose and compute ). Since the chosen key can be small, whereas the computed key normally is not, the RSA paper's algorithm optimizes decryption compared to encryption, while the modern algorithm optimizes encryption instead.

Key distribution

Suppose that Bob wants to send information to Alice. If they decide to use RSA, Bob must know Alice's public key to encrypt the message, and Alice must use her private key to decrypt the message. To enable Bob to send his encrypted messages, Alice transmits her public key to Bob via a reliable, but not necessarily secret, route. Alice's private key is never distributed.Encryption

After Bob obtains Alice's public key, he can send a message to Alice. To do it, he first turns (strictly speaking, the un-padded plaintext) into an integer (strictly speaking, the padded plaintext), such that by using an agreed-upon reversible protocol known as a padding scheme. He then computes the ciphertext , using Alice's public key , corresponding to This can be done reasonably quickly, even for very large numbers, using modular exponentiation. Bob then transmits to Alice. Note that at least nine values of will yield a ciphertext equal to , but this is very unlikely to occur in practice.Decryption

Alice can recover from by using her private key exponent by computing Given , she can recover the original message by reversing the padding scheme.Example

Here is an example of RSA encryption and decryption: # Choose two distinct prime numbers, such as #: and . # Compute giving #: # Compute the Carmichael's totient function of the product as giving #: # Choose any number that is coprime to 780. Choosing a prime number for leaves us only to check that is not a divisor of 780. #: Let . # Compute , the modular multiplicative inverse of , yieldingas The public key is . For a padded plaintext message , the encryption function is The private key is . For an encrypted ciphertext , the decryption function is For instance, in order to encrypt , one calculates To decrypt , one calculates Both of these calculations can be computed efficiently using the square-and-multiply algorithm for modular exponentiation. In real-life situations the primes selected would be much larger; in our example it would be trivial to factor (obtained from the freely available public key) back to the primes and . , also from the public key, is then inverted to get , thus acquiring the private key. Practical implementations use the Chinese remainder theorem to speed up the calculation using modulus of factors (mod ''pq'' using mod ''p'' and mod ''q''). The values , and , which are part of the private key are computed as follows: Here is how , and are used for efficient decryption (encryption is efficient by choice of a suitable and pair):

Signing messages

Suppose Alice uses Bob's public key to send him an encrypted message. In the message, she can claim to be Alice, but Bob has no way of verifying that the message was from Alice, since anyone can use Bob's public key to send him encrypted messages. In order to verify the origin of a message, RSA can also be used to sign a message. Suppose Alice wishes to send a signed message to Bob. She can use her own private key to do so. She produces a hash value of the message, raises it to the power of (modulo ) (as she does when decrypting a message), and attaches it as a "signature" to the message. When Bob receives the signed message, he uses the same hash algorithm in conjunction with Alice's public key. He raises the signature to the power of (modulo ) (as he does when encrypting a message), and compares the resulting hash value with the message's hash value. If the two agree, he knows that the author of the message was in possession of Alice's private key and that the message has not been tampered with since being sent. This works because ofexponentiation

In mathematics, exponentiation, denoted , is an operation (mathematics), operation involving two numbers: the ''base'', , and the ''exponent'' or ''power'', . When is a positive integer, exponentiation corresponds to repeated multiplication ...

rules:

Thus the keys may be swapped without loss of generality, that is, a private key of a key pair may be used either to:

# Decrypt a message only intended for the recipient, which may be encrypted by anyone having the public key (asymmetric encrypted transport).

# Encrypt a message which may be decrypted by anyone, but which can only be encrypted by one person; this provides a digital signature.

Proofs of correctness

Proof using Fermat's little theorem

The proof of the correctness of RSA is based on Fermat's little theorem, stating that for any integer and prime , not dividing . We want to show that for every integer when and are distinct prime numbers and and are positive integers satisfying . Since is, by construction, divisible by both and , we can write for some nonnegative integers and . To check whether two numbers, such as and , are congruent , it suffices (and in fact is equivalent) to check that they are congruent and separately. To show , we consider two cases: # If , is a multiple of . Thus ''med'' is a multiple of . So . # If , #: #: where we used Fermat's little theorem to replace with 1. The verification that proceeds in a completely analogous way: # If , ''med'' is a multiple of . So . # If , #: This completes the proof that, for any integer , and integers , such that ,Notes

Proof using Euler's theorem

Although the original paper of Rivest, Shamir, and Adleman used Fermat's little theorem to explain why RSA works, it is common to find proofs that rely instead on Euler's theorem. We want to show that , where is a product of two different prime numbers, and and are positive integers satisfying . Since and are positive, we can write for some non-negative integer . ''Assuming'' that is relatively prime to , we have where the second-last congruence follows from Euler's theorem. More generally, for any and satisfying , the same conclusion follows from Carmichael's generalization of Euler's theorem, which states that for all relatively prime to . When is not relatively prime to , the argument just given is invalid. This is highly improbable (only a proportion of numbers have this property), but even in this case, the desired congruence is still true. Either or , and these cases can be treated using the previous proof.Padding

Attacks against plain RSA

There are a number of attacks against plain RSA as described below. * When encrypting with low encryption exponents (e.g., ) and small values of the (i.e., ), the result of is strictly less than the modulus . In this case, ciphertexts can be decrypted easily by taking the th root of the ciphertext over the integers. * If the same clear-text message is sent to or more recipients in an encrypted way, and the receivers share the same exponent , but different , , and therefore , then it is easy to decrypt the original clear-text message via the Chinese remainder theorem. Johan Håstad noticed that this attack is possible even if the clear texts are not equal, but the attacker knows a linear relation between them. This attack was later improved by Don Coppersmith (see Coppersmith's attack). * Because RSA encryption is a deterministic encryption algorithm (i.e., has no random component) an attacker can successfully launch a chosen plaintext attack against the cryptosystem, by encrypting likely plaintexts under the public key and test whether they are equal to the ciphertext. A cryptosystem is called semantically secure if an attacker cannot distinguish two encryptions from each other, even if the attacker knows (or has chosen) the corresponding plaintexts. RSA without padding is not semantically secure. * RSA has the property that the product of two ciphertexts is equal to the encryption of the product of the respective plaintexts. That is, . Because of this multiplicative property, a chosen-ciphertext attack is possible. E.g., an attacker who wants to know the decryption of a ciphertext may ask the holder of the private key to decrypt an unsuspicious-looking ciphertext for some value chosen by the attacker. Because of the multiplicative property, ' is the encryption of . Hence, if the attacker is successful with the attack, they will learn from which they can derive the message by multiplying with the modular inverse of modulo . * Given the private exponent , one can efficiently factor the modulus . And given factorization of the modulus , one can obtain any private key (', ) generated against a public key (', ).Padding schemes

To avoid these problems, practical RSA implementations typically embed some form of structured, randomized padding into the value before encrypting it. This padding ensures that does not fall into the range of insecure plaintexts, and that a given message, once padded, will encrypt to one of a large number of different possible ciphertexts. Standards such as PKCS#1 have been carefully designed to securely pad messages prior to RSA encryption. Because these schemes pad the plaintext with some number of additional bits, the size of the un-padded message must be somewhat smaller. RSA padding schemes must be carefully designed so as to prevent sophisticated attacks that may be facilitated by a predictable message structure. Early versions of the PKCS#1 standard (up to version 1.5) used a construction that appears to make RSA semantically secure. However, at Crypto 1998, Bleichenbacher showed that this version is vulnerable to a practical adaptive chosen-ciphertext attack. Furthermore, at Eurocrypt 2000, Coron et al. showed that for some types of messages, this padding does not provide a high enough level of security. Later versions of the standard include Optimal Asymmetric Encryption Padding (OAEP), which prevents these attacks. As such, OAEP should be used in any new application, and PKCS#1 v1.5 padding should be replaced wherever possible. The PKCS#1 standard also incorporates processing schemes designed to provide additional security for RSA signatures, e.g. the Probabilistic Signature Scheme for RSA ( RSA-PSS). Secure padding schemes such as RSA-PSS are as essential for the security of message signing as they are for message encryption. Two USA patents on PSS were granted ( and ); however, these patents expired on 24 July 2009 and 25 April 2010 respectively. Use of PSS no longer seems to be encumbered by patents. Note that using different RSA key pairs for encryption and signing is potentially more secure.Security and practical considerations

Using the Chinese remainder algorithm

For efficiency, many popular crypto libraries (such as OpenSSL,Java

Java is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea (a part of Pacific Ocean) to the north. With a population of 156.9 million people (including Madura) in mid 2024, proje ...

and .NET) use for decryption and signing the following optimization based on the Chinese remainder theorem. The following values are precomputed and stored as part of the private key:

* and the primes from the key generation,

*

*

*

These values allow the recipient to compute the exponentiation more efficiently as follows:

,

,

,

.

This is more efficient than computing exponentiation by squaring, even though two modular exponentiations have to be computed. The reason is that these two modular exponentiations both use a smaller exponent and a smaller modulus.

Integer factorization and the RSA problem

The security of the RSA cryptosystem is based on two mathematical problems: the problem of factoring large numbers and the RSA problem. Full decryption of an RSA ciphertext is thought to be infeasible on the assumption that both of these problems are hard, i.e., no efficient algorithm exists for solving them. Providing security against ''partial'' decryption may require the addition of a secure padding scheme. The RSA problem is defined as the task of taking th roots modulo a composite : recovering a value such that , where is an RSA public key, and is an RSA ciphertext. Currently the most promising approach to solving the RSA problem is to factor the modulus . With the ability to recover prime factors, an attacker can compute the secret exponent from a public key , then decrypt using the standard procedure. To accomplish this, an attacker factors into and , and computes that allows the determination of from . No polynomial-time method for factoring large integers on a classical computer has yet been found, but it has not been proven that none exists; see integer factorization for a discussion of this problem. The first RSA-512 factorization in 1999 used hundreds of computers and required the equivalent of 8,400 MIPS years, over an elapsed time of about seven months. By 2009, Benjamin Moody could factor an 512-bit RSA key in 73 days using only public software (GGNFS) and his desktop computer (a dual-core Athlon64 with a 1,900 MHz CPU). Just less than 5 gigabytes of disk storage was required and about 2.5 gigabytes of RAM for the sieving process. Rivest, Shamir, and Adleman noted that Miller has shown that – assuming the truth of the extended Riemann hypothesis – finding from and is as hard as factoring into and (up to a polynomial time difference). However, Rivest, Shamir, and Adleman noted, in section IX/D of their paper, that they had not found a proof that inverting RSA is as hard as factoring. , the largest publicly known factored RSA number had 829 bits (250 decimal digits, RSA-250). Its factorization, by a state-of-the-art distributed implementation, took about 2,700 CPU-years. In practice, RSA keys are typically 1024 to 4096 bits long. In 2003, RSA Security estimated that 1024-bit keys were likely to become crackable by 2010. As of 2020, it is not known whether such keys can be cracked, but minimum recommendations have moved to at least 2048 bits. It is generally presumed that RSA is secure if is sufficiently large, outside of quantum computing. If is 300 bits or shorter, it can be factored in a few hours on a personal computer, using software already freely available. Keys of 512 bits have been shown to be practically breakable in 1999, when RSA-155 was factored by using several hundred computers, and these are now factored in a few weeks using common hardware. Exploits using 512-bit code-signing certificates that may have been factored were reported in 2011. A theoretical hardware device named TWIRL, described by Shamir and Tromer in 2003, called into question the security of 1024-bit keys. In 1994, Peter Shor showed that a quantum computer – if one could ever be practically created for the purpose – would be able to factor in polynomial time, breaking RSA; see Shor's algorithm.Faulty key generation

Finding the large primes and is usually done by testing random numbers of the correct size with probabilistic primality tests that quickly eliminate virtually all of the nonprimes. The numbers and should not be "too close", lest the Fermat factorization for be successful. If is less than (, which even for "small" 1024-bit values of is ), solving for and is trivial. Furthermore, if either or has only small prime factors, can be factored quickly by Pollard's ''p'' − 1 algorithm, and hence such values of or should be discarded. It is important that the private exponent be large enough. Michael J. Wiener showed that if is between and (which is quite typical) and , then can be computed efficiently from and . There is no known attack against small public exponents such as , provided that the proper padding is used. Coppersmith's attack has many applications in attacking RSA specifically if the public exponent is small and if the encrypted message is short and not padded. 65537 is a commonly used value for ; this value can be regarded as a compromise between avoiding potential small-exponent attacks and still allowing efficient encryptions (or signature verification). The NIST Special Publication on Computer Security (SP 800-78 Rev. 1 of August 2007) does not allow public exponents smaller than 65537, but does not state a reason for this restriction. In October 2017, a team of researchers from Masaryk University announced the ROCA vulnerability, which affects RSA keys generated by an algorithm embodied in a library from Infineon known as RSALib. A large number of smart cards and trusted platform modules (TPM) were shown to be affected. Vulnerable RSA keys are easily identified using a test program the team released.Importance of strong random number generation

A cryptographically strong random number generator, which has been properly seeded with adequate entropy, must be used to generate the primes and . An analysis comparing millions of public keys gathered from the Internet was carried out in early 2012 by Arjen K. Lenstra, James P. Hughes, Maxime Augier, Joppe W. Bos, Thorsten Kleinjung and Christophe Wachter. They were able to factor 0.2% of the keys using only Euclid's algorithm. They exploited a weakness unique to cryptosystems based on integer factorization. If is one public key, and is another, then if by chance (but is not equal to '), then a simple computation of factors both and ', totally compromising both keys. Lenstra et al. note that this problem can be minimized by using a strong random seed of bit length twice the intended security level, or by employing a deterministic function to choose given , instead of choosing and independently. Nadia Heninger was part of a group that did a similar experiment. They used an idea of Daniel J. Bernstein to compute the GCD of each RSA key against the product of all the other keys ' they had found (a 729-million-digit number), instead of computing each separately, thereby achieving a very significant speedup, since after one large division, the GCD problem is of normal size. Heninger says in her blog that the bad keys occurred almost entirely in embedded applications, including "firewalls, routers, VPN devices, remote server administration devices, printers, projectors, and VOIP phones" from more than 30 manufacturers. Heninger explains that the one-shared-prime problem uncovered by the two groups results from situations where the pseudorandom number generator is poorly seeded initially, and then is reseeded between the generation of the first and second primes. Using seeds of sufficiently high entropy obtained from key stroke timings or electronic diode noise or atmospheric noise from a radio receiver tuned between stations should solve the problem. Strong random number generation is important throughout every phase of public-key cryptography. For instance, if a weak generator is used for the symmetric keys that are being distributed by RSA, then an eavesdropper could bypass RSA and guess the symmetric keys directly.Timing attacks

Kocher described a new attack on RSA in 1995: if the attacker Eve knows Alice's hardware in sufficient detail and is able to measure the decryption times for several known ciphertexts, Eve can deduce the decryption key quickly. This attack can also be applied against the RSA signature scheme. In 2003, Boneh and Brumley demonstrated a more practical attack capable of recovering RSA factorizations over a network connection (e.g., from a Secure Sockets Layer (SSL)-enabled webserver). This attack takes advantage of information leaked by the Chinese remainder theorem optimization used by many RSA implementations. One way to thwart these attacks is to ensure that the decryption operation takes a constant amount of time for every ciphertext. However, this approach can significantly reduce performance. Instead, most RSA implementations use an alternate technique known as cryptographic blinding. RSA blinding makes use of the multiplicative property of RSA. Instead of computing , Alice first chooses a secret random value and computes . The result of this computation, after applying Euler's theorem, is , and so the effect of can be removed by multiplying by its inverse. A new value of is chosen for each ciphertext. With blinding applied, the decryption time is no longer correlated to the value of the input ciphertext, and so the timing attack fails.Adaptive chosen-ciphertext attacks

In 1998, Daniel Bleichenbacher described the first practical adaptive chosen-ciphertext attack against RSA-encrypted messages using the PKCS #1 v1 padding scheme (a padding scheme randomizes and adds structure to an RSA-encrypted message, so it is possible to determine whether a decrypted message is valid). Due to flaws with the PKCS #1 scheme, Bleichenbacher was able to mount a practical attack against RSA implementations of the Secure Sockets Layer protocol and to recover session keys. As a result of this work, cryptographers now recommend the use of provably secure padding schemes such as Optimal Asymmetric Encryption Padding, and RSA Laboratories has released new versions of PKCS #1 that are not vulnerable to these attacks. A variant of this attack, dubbed "BERserk", came back in 2014. It impacted the Mozilla NSS Crypto Library, which was used notably by Firefox and Chrome.Side-channel analysis attacks

A side-channel attack using branch-prediction analysis (BPA) has been described. Many processors use a branch predictor to determine whether a conditional branch in the instruction flow of a program is likely to be taken or not. Often these processors also implement simultaneous multithreading (SMT). Branch-prediction analysis attacks use a spy process to discover (statistically) the private key when processed with these processors. Simple Branch Prediction Analysis (SBPA) claims to improve BPA in a non-statistical way. In their paper, "On the Power of Simple Branch Prediction Analysis", the authors of SBPA (Onur Aciicmez and Cetin Kaya Koc) claim to have discovered 508 out of 512 bits of an RSA key in 10 iterations. A power-fault attack on RSA implementations was described in 2010. The author recovered the key by varying the CPU power voltage outside limits; this caused multiple power faults on the server.Tricky implementation

There are many details to keep in mind in order to implement RSA securely (strong PRNG, acceptable public exponent, etc.). This makes the implementation challenging, to the point that the book ''Practical Cryptography With Go'' suggests avoiding RSA if possible.Implementations

Some cryptography libraries that provide support for RSA include: * Botan * Bouncy Castle * cryptlib * Crypto++ * Libgcrypt * Nettle * OpenSSL * wolfCrypt * GnuTLS * mbed TLS * LibreSSLSee also

* Acoustic cryptanalysis *Computational complexity theory

In theoretical computer science and mathematics, computational complexity theory focuses on classifying computational problems according to their resource usage, and explores the relationships between these classifications. A computational problem ...

* Diffie–Hellman key exchange

* Digital Signature Algorithm

* Elliptic-curve cryptography

* Key exchange

* Key management

* Key size

* Public-key cryptography

* Rabin cryptosystem

* Trapdoor function

Notes

References

Further reading

* *External links

* The Original RSA Patent as filed with the U.S. Patent Office by Rivest; Ronald L. (Belmont, MA), Shamir; Adi (Cambridge, MA), Adleman; Leonard M. (Arlington, MA), December 14, 1977, .RFC 8017: PKCS #1: RSA Cryptography Specifications Version 2.2

*

Onur Aciicmez, Cetin Kaya Koc, Jean-Pierre Seifert: ''On the Power of Simple Branch Prediction Analysis''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Rsa Public-key encryption schemes Digital signature schemes