Pyotr Stolypin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

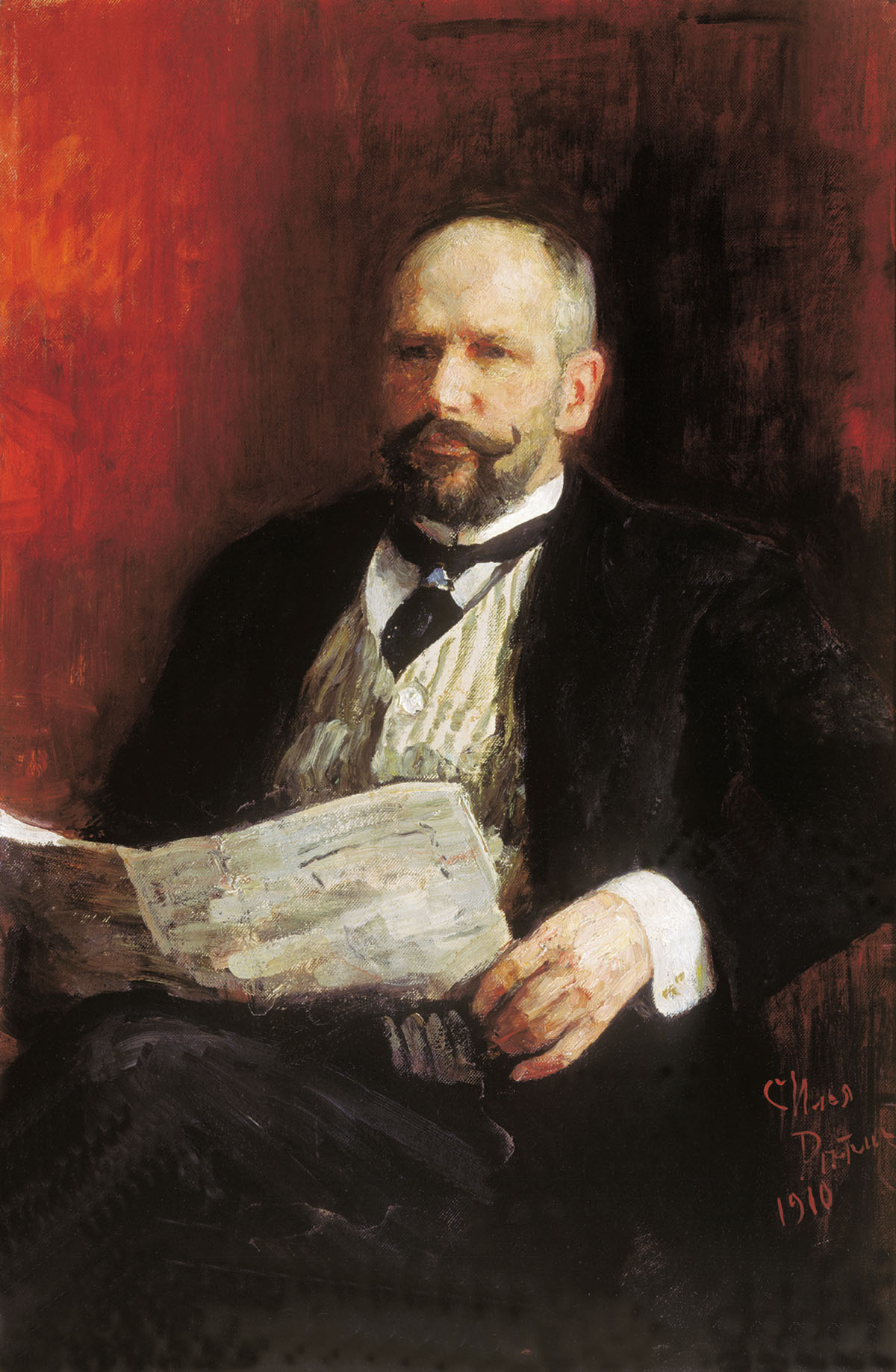

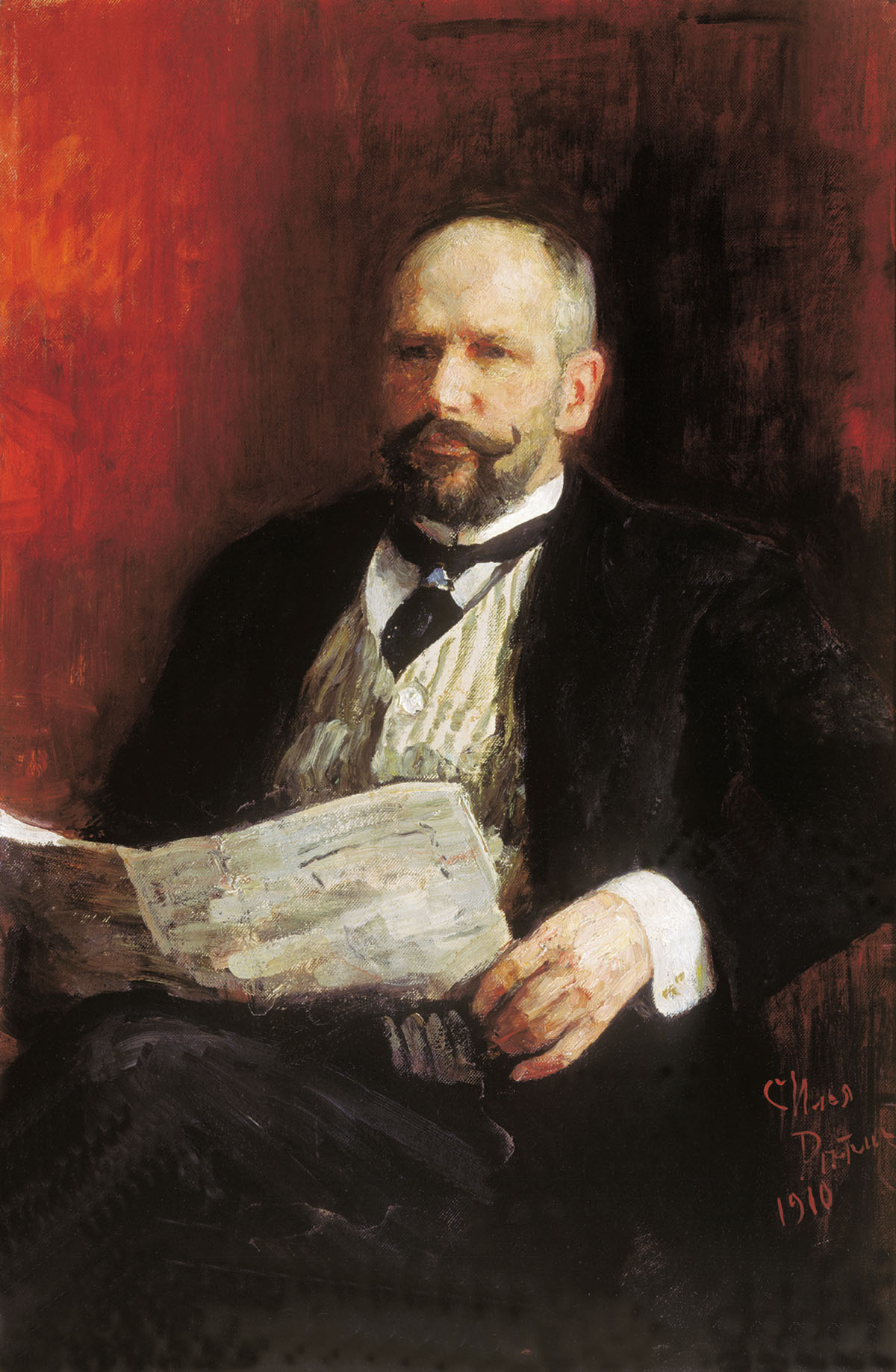

Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin ( rus, Пётр Аркадьевич Столыпин, p=pʲɵtr ɐrˈkadʲjɪvʲɪtɕ stɐˈlɨpʲɪn; – ) was a Russian statesman who served as the third

In February 1903, he became governor of

In February 1903, he became governor of

As governor in Saratov, Stolypin had become convinced that the

As governor in Saratov, Stolypin had become convinced that the

Stolypin traveled to Kiev despite police warnings of an assassination plot, as there had already been 10 attempts to kill him. On , Stolypin attended a performance of Rimsky-Korsakov's ''The Tale of Tsar Saltan'' at the Kiev Opera in the presence of the tsar and his eldest daughters, grand duchesses Olga and Tatiana. The theater was guarded by 90 men inside the building. According to Alexander Spiridovich, after the second act "Stolypin was standing in front of the ramp separating the parterre from the orchestra, his back to the stage. On his right were Baron Freedericksz and Gen. Sukhomlinov." His personal bodyguard had stepped out to smoke. Stolypin was shot twice, once in the arm and once in the chest, by Dmitry Bogrov, a Jewish leftist revolutionary. Bogrov ran to one of the entrances and was caught. Stolypin rose from his chair, removed his gloves and unbuttoned his jacket, exposing a blood-soaked waistcoat. He gave a gesture to tell the tsar to go back and made the sign of the cross. He remained conscious, but his condition deteriorated. He died four days later.

Bogrov was hanged 10 days after the assassination. The judicial investigation was halted by order of the tsar, giving rise to suggestions that the assassination was planned not by leftists, but by conservative monarchists opposed to Stolypin's reforms and his influence on the tsar. However, this has never been proven. On his request, Stolypin was buried in the city where he was murdered.

Stolypin traveled to Kiev despite police warnings of an assassination plot, as there had already been 10 attempts to kill him. On , Stolypin attended a performance of Rimsky-Korsakov's ''The Tale of Tsar Saltan'' at the Kiev Opera in the presence of the tsar and his eldest daughters, grand duchesses Olga and Tatiana. The theater was guarded by 90 men inside the building. According to Alexander Spiridovich, after the second act "Stolypin was standing in front of the ramp separating the parterre from the orchestra, his back to the stage. On his right were Baron Freedericksz and Gen. Sukhomlinov." His personal bodyguard had stepped out to smoke. Stolypin was shot twice, once in the arm and once in the chest, by Dmitry Bogrov, a Jewish leftist revolutionary. Bogrov ran to one of the entrances and was caught. Stolypin rose from his chair, removed his gloves and unbuttoned his jacket, exposing a blood-soaked waistcoat. He gave a gesture to tell the tsar to go back and made the sign of the cross. He remained conscious, but his condition deteriorated. He died four days later.

Bogrov was hanged 10 days after the assassination. The judicial investigation was halted by order of the tsar, giving rise to suggestions that the assassination was planned not by leftists, but by conservative monarchists opposed to Stolypin's reforms and his influence on the tsar. However, this has never been proven. On his request, Stolypin was buried in the city where he was murdered.

Since 1905 Russia had been plagued by widespread political dissatisfaction and revolutionary unrest. With broad support, leftist organizations waged a violent campaign against the autocracy; throughout Russia, many police officials and bureaucrats were assassinated. "Stolypin inspected rebellious areas unarmed and without bodyguards. During one of these trips, somebody dropped a bomb under his feet. There were casualties, but Stolypin survived." To respond to these attacks, Stolypin introduced a new court system of

Since 1905 Russia had been plagued by widespread political dissatisfaction and revolutionary unrest. With broad support, leftist organizations waged a violent campaign against the autocracy; throughout Russia, many police officials and bureaucrats were assassinated. "Stolypin inspected rebellious areas unarmed and without bodyguards. During one of these trips, somebody dropped a bomb under his feet. There were casualties, but Stolypin survived." To respond to these attacks, Stolypin introduced a new court system of

online

* Pares, Bernard. ''A History of Russia'' (1926) pp. 495–506

Online

* Pares, Bernard. '' The Fall of the Russian Monarchy'' (1939) pp. 94–143

Online

*

Stolypin and the Russian Agrarian Miracle

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Stolypin, Petr 1862 births 1911 deaths People murdered in 1911 Antisemitism in Russia Marshals of nobility Heads of government of the Russian Empire Interior ministers of the Russian Empire Assassinated politicians from the Russian Empire Assassinated prime ministers Burials at the Refectory Church, Kyiv Pechersk Lavra People from Dresden Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order Recipients of the Order of the White Eagle (Russia) Recipients of the Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers Russian anti-communists Untitled nobility from the Russian Empire Anti-Masonry People murdered in the Russian Empire

prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

and the interior minister

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a Cabinet (government), cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and iden ...

of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

from 1906 until his assassination in 1911. Known as the greatest reformer of Russian society and economy, he initiated reforms that caused unprecedented growth of the Russian state, which was halted by his assassination.

Born in Dresden

Dresden (; ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; , ) is the capital city of the States of Germany, German state of Saxony and its second most populous city after Leipzig. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, 12th most p ...

, in the Kingdom of Saxony

The Kingdom of Saxony () was a German monarchy in Central Europe between 1806 and 1918, the successor of the Electorate of Saxony. It joined the Confederation of the Rhine after the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, later joining the German ...

, to a prominent Russian aristocratic family, Stolypin became involved in government from his early 20s. His successes in public service led to rapid promotions, culminating in his appointment as interior minister under prime minister Ivan Goremykin

Ivan Logginovich Goremykin (; 8 November 183924 December 1917) was a Russian politician who served as the prime minister of the Russian Empire in 1906 and again from 1914 to 1916, during World War I. He was the last person to have the civil rank ...

in April 1906. In July, Goremykin resigned and was succeeded as prime minister by Stolypin.

As prime minister, Stolypin initiated major agrarian reform

Land reform (also known as agrarian reform) involves the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership, land use, and land transfers. The reforms may be initiated by governments, by interested groups, or by revolution.

Lan ...

s, known as the Stolypin reform, that granted the right of private land ownership to the peasantry. His tenure was also marked by increased revolutionary unrest, to which he responded with a new system of martial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

that allowed for the arrest, speedy trial, and execution of accused offenders. After numerous assassination attempts, Stolypin was fatally shot in September 1911 by revolutionary Dmitrii Bogrov in Kiev

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

.

Stolypin was a monarchist and hoped to strengthen the throne by modernizing the rural Russian economy. Modernity and efficiency, rather than democracy, were his goals. He argued that the land question could be resolved and revolution averted only when the peasant commune was abolished and a stable landowning class of peasants, the kulak

Kulak ( ; rus, кула́к, r=kulák, p=kʊˈɫak, a=Ru-кулак.ogg; plural: кулаки́, ''kulakí'', 'fist' or 'tight-fisted'), also kurkul () or golchomag (, plural: ), was the term which was used to describe peasants who owned over ...

s, had a stake in the ''status quo''. His successes and failures have been the subject of controversy among scholars, who agree that he was one of the last major statesmen of Imperial Russia with cogent and forceful public reform policies.

Early life and career

Stolypin was born atDresden

Dresden (; ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; , ) is the capital city of the States of Germany, German state of Saxony and its second most populous city after Leipzig. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, 12th most p ...

in the Kingdom of Saxony

The Kingdom of Saxony () was a German monarchy in Central Europe between 1806 and 1918, the successor of the Electorate of Saxony. It joined the Confederation of the Rhine after the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, later joining the German ...

, on 14 April 1862, and was baptized on 24 May in the Russian Orthodox Church

The Russian Orthodox Church (ROC; ;), also officially known as the Moscow Patriarchate (), is an autocephaly, autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodox Christian church. It has 194 dioceses inside Russia. The Primate (bishop), p ...

in that city. His father, Arkady Dmitrievich Stolypin (1821–99), was a Russian envoy at the time.

Stolypin's family was prominent in the Russian aristocracy, his forebears having served the tsars since the 16th century, and as a reward for their service had accumulated huge estates in several provinces. His father was a general in the Russian artillery, the governor of Eastern Rumelia and commandant of the Kremlin

The Moscow Kremlin (also the Kremlin) is a fortified complex in Moscow, Russia. Located in the centre of the country's capital city, the Moscow Kremlin (fortification), Kremlin comprises five palaces, four cathedrals, and the enclosing Mosco ...

Palace guard. He was married twice. His second wife, Natalia Mikhailovna Stolypina (''née'' Gorchakova; 1827–89), was the daughter of Prince Mikhail Dmitrievich Gorchakov, the Commanding general of the Russian infantry during the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

and later the viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory.

The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the Anglo-Norman ''roy'' (Old Frenc ...

of Congress Poland

Congress Poland or Congress Kingdom of Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It was established w ...

.

Pyotr grew up on the family estate ''Serednikovo'' () in Solnechnogorsky District, once inhabited by Mikhail Lermontov

Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov ( , ; rus, Михаи́л Ю́рьевич Ле́рмонтов, , mʲɪxɐˈil ˈjʉrʲjɪvʲɪtɕ ˈlʲerməntəf, links=yes; – ) was a Russian Romanticism, Romantic writer, poet and painter, sometimes called ...

, near Moscow Governorate

The Moscow Governorate was a province ('' guberniya'') of the Tsardom of Russia, and the Russian Empire. It was bordered by Tver Governorate to the north, Vladimir Governorate to the northeast, Ryazan Governorate to the southeast, Tula Gove ...

. In 1879 the family moved to Oryol

Oryol ( rus, Орёл, , ɐˈrʲɵl, a=ru-Орёл.ogg, links=y, ), also transliterated as Orel or Oriol, is a Classification of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Oryol Oblast, Russia, situated on the Oka Rive ...

. Stolypin and his brother Aleksandr studied at the Oryol Boys College where he was described by his teacher, B. Fedorova, as 'standing out among his peers for his rationalism and character.'

In 1881 Stolypin studied agriculture at St. Petersburg University

Saint Petersburg State University (SPBGU; ) is a public research university in Saint Petersburg, Russia, and one of the oldest and most prestigious universities in Russia. Founded in 1724 by a decree of Peter the Great, the university from the be ...

where one of his teachers was Dmitri Mendeleev

Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev ( ; ) was a Russian chemist known for formulating the periodic law and creating a version of the periodic table of elements. He used the periodic law not only to correct the then-accepted properties of some known ele ...

. He entered government service upon graduating in 1885, writing his thesis on tobacco growing in the south of Russia. It is unclear if he joined the Ministry of State Property or Internal Affairs.

In 1884, Stolypin married Olga Borisovna von Neidhart whose family was of a similar standing to Stolypin's. They married whilst Stolypin was still a student, an uncommon occurrence at the time. The marriage began in tragic circumstances: Olga had been engaged to Stolypin's brother, Mikhail, who died in a duel. The marriage was a happy one, devoid of scandal. The couple had five daughters and one son.

Lithuania

Stolypin spent much of his life and career inLithuania

Lithuania, officially the Republic of Lithuania, is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, bordered by Latvia to the north, Belarus to the east and south, P ...

, then administratively known as Northwestern Krai

Northwestern Krai () was a ''krai'' of the Russian Empire (unofficial subdivision) in the territories of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania (present-day Belarus and Lithuania). The administrative center was in Vilna (now Vilnius). Northwestern ...

of the Russian Empire.

From 1869, Stolypin spent his childhood years in Kalnaberžė manor (now Kėdainiai district of Lithuania

Lithuania, officially the Republic of Lithuania, is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, bordered by Latvia to the north, Belarus to the east and south, P ...

), built by his father, a place that remained his favorite residence for the rest of life. In 1876, the Stolypin family moved to Vilna

Vilnius ( , ) is the capital of and List of cities in Lithuania#Cities, largest city in Lithuania and the List of cities in the Baltic states by population, most-populous city in the Baltic states. The city's estimated January 2025 population w ...

(now Vilnius), where he attended grammar school.

Stolypin served as marshal of the Kovno Governorate

Kovno Governorate was an administrative-territorial unit (''guberniya'') of the Russian Empire, with its capital in Kovno (Kaunas). It was formed on 18 December 1842 by Tsar Nicholas I of Russia, Nicholas I from the western part of Vilna Govern ...

(now Kaunas

Kaunas (; ) is the second-largest city in Lithuania after Vilnius, the fourth largest List of cities in the Baltic states by population, city in the Baltic States and an important centre of Lithuanian economic, academic, and cultural life. Kaun ...

, Lithuania) between 1889 and 1902. This public service gave him an inside view of local needs and allowed him to develop administrative skills. His thinking was influenced by the single-family farmstead system of the Northwestern Krai, and he later sought to introduce the land reform based on private ownership throughout the Russian Empire.

Stolypin's service in Kovno was deemed a success by the Russian government. He was promoted seven times, culminating in his promotion to the rank of state councilor

A State Councillor of the People's Republic of China () serves as a senior vice leader within the State Council and shares responsibilities with the Vice Premiers in assisting the Premier in the administration and coordination of governmental a ...

in 1901. Four of his daughters were also born during this period; his daughter Maria recalled: "this was the most calm period fhis life".

In May 1902 Stolypin was appointed governor in Grodno Governorate

Grodno Governorate was an administrative-territorial unit (''guberniya'') of the Northwestern Krai of the Russian Empire, with its capital in Grodno. It encompassed in area and consisted of a population of 1,603,409 inhabitants by 1897. Gro ...

, where he was the youngest person ever appointed to this position.

Governor of Saratov

In February 1903, he became governor of

In February 1903, he became governor of Saratov

Saratov ( , ; , ) is the largest types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and administrative center of Saratov Oblast, Russia, and a major port on the Volga River. Saratov had a population of 901,361, making it the List of cities and tow ...

. Stolypin is known for suppressing strikers and peasant unrest in January 1905. According to Orlando Figes

Orlando Guy Figes (; born 20 November 1959) is a British and German historian and writer. He was a professor of history at Birkbeck College, University of London, where he was made Emeritus Professor on his retirement in 2022.

Figes is known f ...

, its peasants were among the poorest and most rebellious in the whole of the country.O. Figes (1996) ''A People's Tragedy. The Russian Revolution 1891–1924'', p. 223. It seems he cooperated with the zemstvo

A zemstvo (, , , ''zemstva'') was an institution of local government set up in consequence of the emancipation reform of 1861 of Imperial Russia by Emperor Alexander II of Russia. Nikolay Milyutin elaborated the idea of the zemstvo, and the fi ...

s, the local government. He gained a reputation as the only governor able to keep a firm hold on his province during the Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905, also known as the First Russian Revolution, was a revolution in the Russian Empire which began on 22 January 1905 and led to the establishment of a constitutional monarchy under the Russian Constitution of 1906, t ...

, a period of widespread revolt. The roots of unrest lay partly in the Emancipation Reform of 1861

The emancipation reform of 1861 in Russia, also known as the Edict of Emancipation of Russia, ( – "peasants' reform of 1861") was the first and most important of the liberal reforms enacted during the reign of Emperor Alexander II of Russia. T ...

, which had given land to the Obshchina

An (, ; rus, община, p=ɐpˈɕːinə) or (, ; rus, мир, p=mʲir), also officially termed as a rural community (; ) between the 19th and 20th centuries, was a peasant village community (as opposed to an individual farmstead), or a ...

, instead of individually to the newly freed serfs

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed dur ...

. Stolypin was the first governor to use effective police methods. Some sources suggest that he had a police record on every adult male in his province.

Interior minister and prime minister

Stolypin's successes as provincial governor led to his appointment as interior minister underIvan Goremykin

Ivan Logginovich Goremykin (; 8 November 183924 December 1917) was a Russian politician who served as the prime minister of the Russian Empire in 1906 and again from 1914 to 1916, during World War I. He was the last person to have the civil rank ...

in April 1906. He advocated for a new track of the Trans-Siberian Railway

The Trans-Siberian Railway, historically known as the Great Siberian Route and often shortened to Transsib, is a large railway system that connects European Russia to the Russian Far East. Spanning a length of over , it is the longest railway ...

along the Russian side of the Amur

The Amur River () or Heilong River ( zh, s=黑龙江) is a perennial river in Northeast Asia, forming the natural border between the Russian Far East and Northeast China (historically the Outer Manchuria, Outer and Inner Manchuria). The Amur ...

river.

The absent-minded Goremykin had been described by his predecessor Sergei Witte as a bureaucratic nonentity. After two months, Dmitri Feodorovich Trepov suggested Goremykin step down and conducted secret negotiations with Pavel Milyukov

Pavel Nikolayevich Milyukov ( rus, Па́вел Никола́евич Милюко́в, p=mʲɪlʲʊˈkof; 31 March 1943) was a Russian historian and liberal politician. Milyukov was the founder, leader, and the most prominent member of the C ...

, who proposed a cabinet of only Kadets, which Trepov believed would fall afoul of Tsar Nicholas II. Trepov opposed Stolypin, who promoted a coalition cabinet

A coalition government, or coalition cabinet, is a government by political parties that enter into a power-sharing arrangement of the executive. Coalition governments usually occur when no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an e ...

. Georgy Lvov and Alexander Guchkov tried to convince the Tsar to accept liberals in the new government.

When Goremykin resigned on , Nicholas II appointed Stolypin as Prime Minister, while remaining as Minister of the Interior. He dissolved the Duma

A duma () is a Russian assembly with advisory or legislative functions.

The term ''boyar duma'' is used to refer to advisory councils in Russia from the 10th to 17th centuries. Starting in the 18th century, city dumas were formed across Russia ...

, despite the reluctance of some of its more radical members, to clear the field for cooperation with the new government. In response, 120 Kadet and 80 Trudovik and Social Democrat

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

deputies went to Vyborg

Vyborg (; , ; , ; , ) is a town and the administrative center of Vyborgsky District in Leningrad Oblast, Russia. It lies on the Karelian Isthmus near the head of Vyborg Bay, northwest of St. Petersburg, east of the Finnish capital H ...

(then under the autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland

The Grand Duchy of Finland was the predecessor state of modern Finland. It existed from 1809 to 1917 as an Autonomous region, autonomous state within the Russian Empire.

Originating in the 16th century as a titular grand duchy held by the Monarc ...

, beyond the reach of Russian police) and responded with the Vyborg Manifesto (or the "Vyborg Appeal"), written by Pavel Milyukov. Stolypin allowed the signers to return to the capital unmolested.

On 25 August 1906, three assassins from the Union of Socialists-Revolutionaries Maximalists, wearing military uniforms, bombed a public reception Stolypin was holding at his dacha

A dacha (Belarusian, Ukrainian language, Ukrainian and rus, дача, p=ˈdatɕə, a=ru-dacha.ogg) is a seasonal or year-round second home, often located in the exurbs of former Soviet Union, post-Soviet countries, including Russia. A cottage (, ...

on Aptekarsky Island. Stolypin was only slightly injured by flying splinters, but 28 others were killed. Stolypin's 15-year-old daughter lost both legs and later succumbed to her injuries at the hospital, and his 3-year-old son Arkady broke a leg, as the two stood on a balcony. Stolypin moved into the Winter Palace

The Winter Palace is a palace in Saint Petersburg that served as the official residence of the House of Romanov, previous emperors, from 1732 to 1917. The palace and its precincts now house the Hermitage Museum. The floor area is 233,345 square ...

. In October 1906, at the request of the tsar, Grigori Rasputin

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin ( – ) was a Russian Mysticism, mystic and faith healer. He is best known for having befriended the imperial family of Nicholas II of Russia, Nicholas II, the last Emperor of all the Russias, Emperor of Russia, th ...

paid a visit to the wounded child. On 9 November an imperial decree made far-reaching changes in land tenure law, disrupting in one sweep the communal and the household (family) property systems.

Stolypin changed the rules of the First Duma to attempt to make it more amenable to government proposals. On 8 June 1907, Stolypin dissolved the Second Duma, and 15 Kadets who had associated with terrorists were arrested; he also changed the weight of votes in favor of the nobility and wealthy, reducing the value of lower-class votes. The leading Kadets were ineligible. This affected the elections to the Third Duma, which returned much more conservative members eager to cooperate with the government. This changed Georgy Lvov from a moderate liberal into a radical.

As governor in Saratov, Stolypin had become convinced that the

As governor in Saratov, Stolypin had become convinced that the open field system

The open-field system was the prevalent agricultural system in much of Europe during the Middle Ages and lasted into the 20th century in Russia, Iran, and Turkey. Each manor or village had two or three large fields, usually several hundred acr ...

had to be abolished; communal land tenure

In Common law#History, common law systems, land tenure, from the French verb "" means "to hold", is the legal regime in which land "owned" by an individual is possessed by someone else who is said to "hold" the land, based on an agreement betw ...

had to go. The chief obstacle appeared to be the Mir (commune), so its dissolution and the individualization of peasant land ownership became the leading objectives of his agrarian policy. He introduced Denmark-style land reforms to allay peasant grievances and soothe dissent. Stolypin proposed his own landlord-sided reform in opposition to the previous democratic proposals which led to the dissolution of the first two Russian parliaments. Stolypin's reforms aimed to stem peasant unrest by creating a class of market-oriented smallholders who would support the social order. He was assisted by Alexander Krivoshein, who in 1908 became Minister of Agriculture. In June 1908 Stolypin lived in a wing of the Yelagin Palace where the Council of Ministers

Council of Ministers is a traditional name given to the supreme Executive (government), executive organ in some governments. It is usually equivalent to the term Cabinet (government), cabinet. The term Council of State is a similar name that also m ...

convened.

Supported by the Peasants' Land Bank, credit cooperatives proliferated from 1908, and Russian industry was booming. Stolypin tried to improve the lives of urban laborers and worked towards increasing the power of local governments, but the zemstvos adopted an attitude hostile to the government.

Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using Reforms of Russian orthography#The post-revolution re ...

was particularly indignant, writing to Stolypin: "Stop your horrible activity! Enough of looking up to Europe, it is high time Russia knew its own mind!" Tolstoy had argued similarly to Dostoyevsky, who was in favor of private ownership of land and wrote: "If you want to transform humanity for the better, to turn almost beasts into humans, give them land and you will reach your goal."

In his handling of the “Jewish Question”, Stolypin set a fine example for his fellow statesmen, petitioning the Tsar to dissolve the Pale of Settlement, visiting synagogues and inviting Jewish musicians to his home to play for his family.

In 1910, Stolypin's brother-in-law Sergey Sazonov became Minister of Foreign Affairs

In many countries, the ministry of foreign affairs (abbreviated as MFA or MOFA) is the highest government department exclusively or primarily responsible for the state's foreign policy and foreign relations, relations, diplomacy, bilateralism, ...

, replacing Count Alexander Izvolsky. Around 1910 the press started a campaign against Rasputin, accusing him of improper sexual relations. Stolypin wanted to ban Rasputin from the capital and threatened to prosecute him as a sectarian. Rasputin decamped to Jerusalem, returning to St. Petersburg only after Stolypin's death.

On 14 June 1910, Stolypin's land reforms came before the Duma as a formal law, including a proposal to spread the zemstvo

A zemstvo (, , , ''zemstva'') was an institution of local government set up in consequence of the emancipation reform of 1861 of Imperial Russia by Emperor Alexander II of Russia. Nikolay Milyutin elaborated the idea of the zemstvo, and the fi ...

system to the southwestern provinces of Asian Russia. Though the law seemed likely to pass, Stolypin's political opponents narrowly defeated it. In March 1911 Stolypin resigned from the fractious and chaotic Duma after the failure of his land-reform bill. Tsar Nicholas II decided to look for a successor to Stolypin and considered Sergei Witte, Vladimir Kokovtsov

Count Vladimir Nikolayevich Kokovtsov (; – 29 January 1943) was a Russian politician who served as the fourth prime minister of Russia from 1911 to 1914, during the reign of Emperor Nicholas II.

Early life

He was born in Borovichi, Borov ...

and Alexei Khvostov. The Moscow Times

''The Moscow Times'' (''MT'') is an Amsterdam-based independent English-language and Russian-language online newspaper. It was in print in Russia from 1992 until 2017 and was distributed free of charge at places frequented by English-speaking to ...

has summarized his career:

Assassination

Legacy

Since 1905 Russia had been plagued by widespread political dissatisfaction and revolutionary unrest. With broad support, leftist organizations waged a violent campaign against the autocracy; throughout Russia, many police officials and bureaucrats were assassinated. "Stolypin inspected rebellious areas unarmed and without bodyguards. During one of these trips, somebody dropped a bomb under his feet. There were casualties, but Stolypin survived." To respond to these attacks, Stolypin introduced a new court system of

Since 1905 Russia had been plagued by widespread political dissatisfaction and revolutionary unrest. With broad support, leftist organizations waged a violent campaign against the autocracy; throughout Russia, many police officials and bureaucrats were assassinated. "Stolypin inspected rebellious areas unarmed and without bodyguards. During one of these trips, somebody dropped a bomb under his feet. There were casualties, but Stolypin survived." To respond to these attacks, Stolypin introduced a new court system of martial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

, that allowed for the arrest and speedy trial of accused offenders. Over 3,000 (possibly 5,500) suspects were convicted and executed by these special courts between 1906 and 1909. In a Duma session on 17 November 1907, Kadet party member referred to the gallows as "Stolypin's efficient black Monday necktie". Outraged, Stolypin challenged Rodichev to a duel, but Rodichev apologized to avert it. Nevertheless, the expression became popular. The capacious railroad cars used for Siberian resettlement were named Stolypin cars.

There remains doubt whether, even without the disruption of Stolypin's murder and the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, his agricultural policy could have succeeded. The deep conservatism from the mass of peasants made them slow to respond. In 1914 the strip system was still widespread, with only around 10% of the land having been consolidated into farms.Lynch, Michael ''From Autocracy to Communism: Russia 1894–1941'' p. 42 Most peasants were unwilling to leave the security of the commune for the uncertainty of individual farming. Furthermore, by 1913, the government's own Ministry of Agriculture had itself begun to lose confidence in the policy. Nevertheless, Krivoshein became the most powerful figure in the Imperial government.

Lenin in the Paris newspaper said, "Social-Democrat" on 31 October 1911, wrote "Stolypin and the Revolution", calling for the "mortification of the uber-lyncher",

Opinion is divided on Stolypin's legacy, and historians disagree over how realistic Stolypin's policies were. Some approve of his firm hand to suppress revolt and anarchy in the unruly atmosphere after the 1905 Revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905, also known as the First Russian Revolution, was a revolution in the Russian Empire which began on 22 January 1905 and led to the establishment of a constitutional monarchy under the Russian Constitution of 1906, t ...

.oks/4051-lenin-vo-franczii.html?start=19 Lenin in France – Stolypin and the Revolution (Ленин во Франции – Столыпин и революция)]. leninism.su saying:

″Stolypin tried to pour new wine into old bottles, to reshape the old autocracy into a bourgeois monarchy; and the failure of Stolypin's policy is the failure of tsarism on this last, the last conceivable, road for tsarism."

In " Name of Russia (Russia TV), Name of Russia", a 2008 television poll to select "the greatest Russian", Stolypin placed second, behind Alexander Nevsky

Alexander Yaroslavich Nevsky (; ; monastic name: ''Aleksiy''; 13 May 1221 – 14 November 1263) was Prince of Novgorod (1236–1240; 1241–1256; 1258–1259), Grand Prince of Kiev (1249–1263), and Grand Prince of Vladimir (1252–1263).

...

and followed by Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

. He is seen by his admirers as the greatest statesman Russia ever had, the one who could have saved the country from revolution and the civil war.

On 27 December 2012, a monument to Pyotr Stolypin was unveiled in Moscow to mark the 150th anniversary of his birth. The monument, designed by Andrei Korobtsov is situated near the Russian White House, seat of the Government of Russia

The Russian Government () or fully titled the Government of the Russian Federation () is the highest federal executive governmental body of the Russian Federation. It is accountable to the president of the Russian Federation and controlled by ...

. At the foot of the pedestal, a bronze plaque quotes Stolypin: ''"We must all unite in defense of Russia, coordinate our efforts, our duties and our rights in order to maintain one of Russia's historic supreme rights – to be strong."''

Screen portrayals

Stolypin is portrayed byEric Porter

Eric Richard Porter (8 April 192815 May 1995) was an English actor of stage, film and television.

Early life

Porter was born in Shepherd's Bush, London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdo ...

in the opening scenes of the 1971 British film '' Nicholas and Alexandra'', fictitiously taking part in the Romanov dynasty tercentenary celebrations of 1913 before being assassinated later in the film, two years after his actual assassination.

Stolypin is portrayed by Frank Middlemass in episode 9 of the 1974 British miniseries ''Fall of Eagles

Autumn, also known as fall (especially in US & Canada), is one of the four temperate seasons on Earth. Outside the tropics, autumn marks the transition from summer to winter, in September (Northern Hemisphere) or March (Southern Hemisphere ...

'', ''Dress Rehearsal.''

See also

* Coup of June 1907 * Stolypin reformReferences

Further reading

* * Conroy, M.S. (1976), ''Peter Arkadʹevich Stolypin: Practical Politics in Late Tsarist Russia'', Westview Press, (Boulder), 1976. * Fuhrmann, Joseph T. (2013). Rasputin, the untold story (illustrated ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 314. . * * Lieven, Dominic, ed. ''The Cambridge History of Russia: Volume 2, Imperial Russia, 1689–1917'' (2015) * * * Pallot, Judith. ''Land reform in Russia, 1906–1917: peasant responses to Stolypin's project of rural transformation'' (1999)online

* Pares, Bernard. ''A History of Russia'' (1926) pp. 495–506

Online

* Pares, Bernard. '' The Fall of the Russian Monarchy'' (1939) pp. 94–143

Online

*

External links

* *Stolypin and the Russian Agrarian Miracle

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Stolypin, Petr 1862 births 1911 deaths People murdered in 1911 Antisemitism in Russia Marshals of nobility Heads of government of the Russian Empire Interior ministers of the Russian Empire Assassinated politicians from the Russian Empire Assassinated prime ministers Burials at the Refectory Church, Kyiv Pechersk Lavra People from Dresden Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order Recipients of the Order of the White Eagle (Russia) Recipients of the Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers Russian anti-communists Untitled nobility from the Russian Empire Anti-Masonry People murdered in the Russian Empire