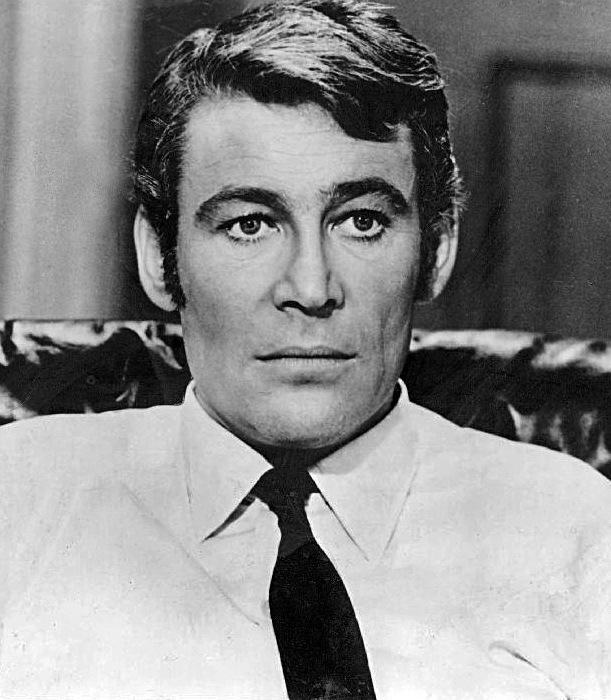

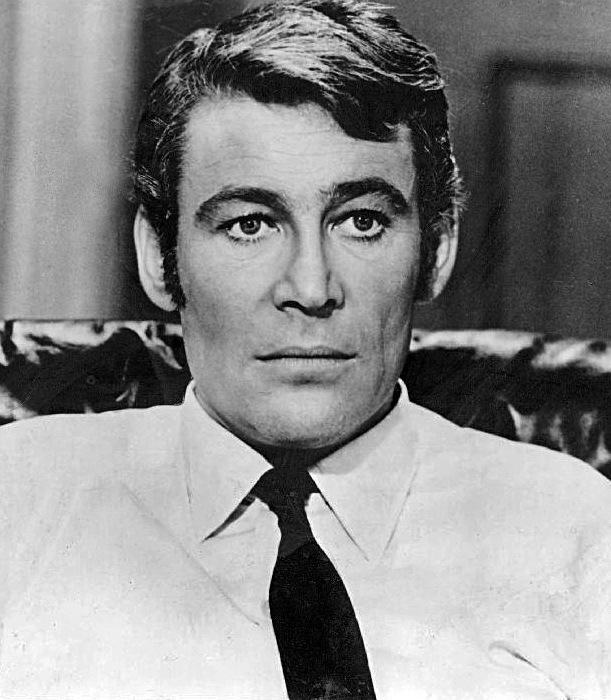

Peter O'Toole on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Peter Seamus O'Toole (; 2 August 1932 – 14 December 2013) was a British stage and film actor. He attended the

Even prior to the making of ''Lawrence of Arabia'', O'Toole announced he wanted to form a production company with Jules Buck. In November 1961 they said their company, known as Keep Films (also known as Tricolor Productions) would make a film starring Terry-Thomas, '' Operation Snatch''. In 1962 O'Toole and Buck announced they wanted to make a version of ''Waiting for Godot'' for £80,000. The film was never made. Instead their first production was '' Becket'' (1964), where O'Toole played King Henry II opposite Richard Burton. The film, done in association with Hal Wallis, was a financial success. O'Toole turned down the lead role in '' The Cardinal'' (1963). Instead he and Buck made another epic, ''

Even prior to the making of ''Lawrence of Arabia'', O'Toole announced he wanted to form a production company with Jules Buck. In November 1961 they said their company, known as Keep Films (also known as Tricolor Productions) would make a film starring Terry-Thomas, '' Operation Snatch''. In 1962 O'Toole and Buck announced they wanted to make a version of ''Waiting for Godot'' for £80,000. The film was never made. Instead their first production was '' Becket'' (1964), where O'Toole played King Henry II opposite Richard Burton. The film, done in association with Hal Wallis, was a financial success. O'Toole turned down the lead role in '' The Cardinal'' (1963). Instead he and Buck made another epic, '' He played Henry II again in ''

He played Henry II again in ''

O'Toole retired from acting in July 2012 owing to a recurrence of stomach cancer. He died on 14 December 2013 at

O'Toole retired from acting in July 2012 owing to a recurrence of stomach cancer. He died on 14 December 2013 at

"Peter O'Toole as Casanova"

University of Bristol Theatre Collection

The Making of ''Lawrence of Arabia''

Digitised BAFTA Journal, Winter 1962–63 (with additional notes by Bryan Hewitt)

Peter O'Toole Interview at 2002 Telluride Film Festival

conducted by

Peter O'Toole

(Aveleyman) {{DEFAULTSORT:Otoole, Peter 1932 births 2013 deaths 20th-century English male actors 21st-century English male actors Academy Honorary Award recipients Alumni of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art Best British Actor BAFTA Award winners Best Drama Actor Golden Globe (film) winners Best Musical or Comedy Actor Golden Globe (film) winners David di Donatello winners British people of Irish descent British people of Scottish descent British male film actors British male Shakespearean actors British male stage actors British male television actors British male voice actors Irish people of Scottish descent Irish male film actors Irish male stage actors Irish male television actors Irish male voice actors New Star of the Year (Actor) Golden Globe winners Outstanding Performance by a Supporting Actor in a Miniseries or Movie Primetime Emmy Award winners People with type 1 diabetes Royal Navy sailors Royal Shakespeare Company members People from Hunslet

Royal Academy of Dramatic Art

The Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA; ) is a drama school in London, England, that provides vocational conservatoire training for theatre, film, television, and radio. It is based in the Bloomsbury area of Central London, close to the Sena ...

and began working in the theatre, gaining recognition as a Shakespearean actor at the Bristol Old Vic

Bristol Old Vic is a British theatre company based at the Theatre Royal, Bristol. The present company was established in 1946 as an offshoot of the Old Vic in London. It is associated with the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School, which became a f ...

and with the English Stage Company. In 1959 he made his West End

West End most commonly refers to:

* West End of London, an area of central London, England

* West End theatre, a popular term for mainstream professional theatre staged in the large theatres of London, England

West End may also refer to:

Pl ...

debut in '' The Long and the Short and the Tall'', and played the title role

The title character in a narrative work is one who is named or referred to in the title of the work. In a performed work such as a play or film, the performer who plays the title character is said to have the title role of the piece. The title of ...

in ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depi ...

'' in the National Theatre's first production in 1963. Excelling on the London stage, O'Toole was known for his "hellraiser" lifestyle off it.

Making his film debut in 1959, O'Toole achieved international recognition playing T. E. Lawrence in ''Lawrence of Arabia

Thomas Edward Lawrence (16 August 1888 – 19 May 1935) was a British archaeologist, army officer, diplomat, and writer who became renowned for his role in the Arab Revolt (1916–1918) and the Sinai and Palestine Campaign (1915–19 ...

'' (1962) for which he received his first nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actor

The Academy Award for Best Actor is an award presented annually by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). It is given to an actor who has delivered an outstanding performance in a leading role in a film released that year. The a ...

. He was nominated for this award another seven times – for playing King Henry II in both '' Becket'' (1964) and ''The Lion in Winter

''The Lion in Winter'' is a 1966 play by James Goldman, depicting the personal and political conflicts of Henry II of England, his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine, their children and their guests during Christmas 1183. It premiered on Broadway at the ...

'' (1968), '' Goodbye, Mr. Chips'' (1969), '' The Ruling Class'' (1972), ''The Stunt Man

''The Stunt Man'' is a 1980 American action comedy film directed by Richard Rush, starring Peter O'Toole, Steve Railsback, and Barbara Hershey. The film was adapted by Lawrence B. Marcus and Rush from the 1970 novel of the same name by Paul Br ...

'' (1980), '' My Favorite Year'' (1982), and ''Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never f ...

'' (2006) – and holds the record for the most Oscar nominations for acting without a win (tied with Glenn Close). In 2002, he was awarded the Academy Honorary Award

The Academy Honorary Award – instituted in 1950 for the 23rd Academy Awards (previously called the Special Award, which was first presented at the 1st Academy Awards in 1929) – is given annually by the Board of Governors of the Academy of M ...

for his career achievements.

O'Toole was the recipient of four Golden Globe Awards

The Golden Globe Awards are accolades bestowed by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association beginning in January 1944, recognizing excellence in both American and international film and television. Beginning in 2022, there are 105 members of ...

, one BAFTA Award for Best British Actor

Best Actor in a Leading Role is a British Academy Film Awards, British Academy Film Award presented annually by the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) to recognize an actor who has delivered an outstanding leading performance in ...

and one Primetime Emmy Award

The Primetime Emmy Awards, or Primetime Emmys, are part of the extensive range of Emmy Awards for artistic and technical merit for the American television industry. Bestowed by the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (ATAS), the Primetime ...

. Other performances include ''What's New Pussycat?

''What's New Pussycat?'' is a 1965 screwball comedy film directed by Clive Donner, written by Woody Allen in his first produced screenplay, and starring Allen in his acting debut, along with Peter Sellers, Peter O'Toole, Romy Schneider, Capuc ...

'' (1965), ''How to Steal a Million

''How to Steal a Million'' is a 1966 American heist comedy film directed by William Wyler and starring Audrey Hepburn, Peter O'Toole, Eli Wallach, Hugh Griffith, and Charles Boyer. The film is set and was filmed in Paris, though the character ...

'' (1966), '' Supergirl'' (1984), and minor roles in '' The Last Emperor'' (1987) and ''Troy

Troy ( el, Τροία and Latin: Troia, Hittite: 𒋫𒊒𒄿𒊭 ''Truwiša'') or Ilion ( el, Ίλιον and Latin: Ilium, Hittite: 𒃾𒇻𒊭 ''Wiluša'') was an ancient city located at Hisarlik in present-day Turkey, south-west of Çan ...

'' (2004). He also voiced Anton Ego, the restaurant critic in Pixar

Pixar Animation Studios (commonly known as Pixar () and stylized as P I X A R) is an American computer animation studio known for its critically and commercially successful computer animated feature films. It is based in Emeryville, Californ ...

's ''Ratatouille

Ratatouille ( , ), oc, ratatolha , is a French Provençal dish of stewed vegetables which originated in Nice, and is sometimes referred to as ''ratatouille niçoise'' (). Recipes and cooking times differ widely, but common ingredients include ...

'' (2007).

Early life and education

Peter Seamus O'Toole was born on 2 August 1932, the son of Constance Jane Eliot (née Ferguson), a Scottish nurse,O'Toole, Peter. ''Loitering with Intent: Child'' (Large print edition), Macmillan London Ltd., London, 1992. ; pg. 10, "My mother, Constance Jane, had led a troubled and a harsh life. Orphaned early, she had been reared in Scotland and shunted between relatives;..." and Patrick Joseph "Spats" O'Toole, an Irish metal plater, football player, andbookmaker

A bookmaker, bookie, or turf accountant is an organization or a person that accepts and pays off bets on sporting and other events at agreed-upon odds.

History

The first bookmaker, Ogden, stood at Newmarket in 1795.

Range of events

Book ...

. O'Toole claimed he was not certain of his birthplace or date, stating in his autobiography that he accepted 2 August as his birth date but had a birth certificate from England and Ireland. Records from the Leeds General Registry Office confirm he was born at St James's University Hospital in Leeds

Leeds () is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the thi ...

, Yorkshire, England on 2 August 1932. He had an elder sister named Patricia and grew up in the south Leeds suburb of Hunslet. When he was one year old, his family began a five-year tour of major racecourse towns in Northern England. He and his sister were brought up in their father's Catholic faith. O'Toole was evacuated from Leeds early in the Second World War, and went to a Catholic school for seven or eight years: St Joseph's Secondary School, just outside Leeds. He later said, "I used to be scared stiff of the nuns: their whole denial of womanhood—the black dresses and the shaving of the hair—was so horrible, so terrifying. ..Of course, that's all been stopped. They're sipping gin and tonic in the Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

pubs now, and a couple of them flashed their pretty ankles at me just the other day."

Upon leaving school, O'Toole obtained employment as a trainee journalist and photographer on the ''Yorkshire Evening Post

The ''Yorkshire Evening Post'' is a daily evening publication (delivered to newsagents every morning) published by Yorkshire Post Newspapers in Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. The paper provides a regional slant on the day's news, and tradi ...

'', until he was called up for national service as a signaller in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by Kingdom of England, English and Kingdom of Scotland, Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were foug ...

. As reported in a radio interview in 2006 on NPR, he was asked by an officer whether he had something he had always wanted to do. His reply was that he had always wanted to try being either a poet or an actor. He attended the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art

The Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA; ) is a drama school in London, England, that provides vocational conservatoire training for theatre, film, television, and radio. It is based in the Bloomsbury area of Central London, close to the Sena ...

(RADA) from 1952 to 1954 on a scholarship. This came after being rejected by the Abbey Theatre

The Abbey Theatre ( ga, Amharclann na Mainistreach), also known as the National Theatre of Ireland ( ga, Amharclann Náisiúnta na hÉireann), in Dublin, Ireland, is one of the country's leading cultural institutions. First opening to the pu ...

's drama school in Dublin by the director Ernest Blythe

Ernest Blythe (; 13 April 1889 – 23 February 1975) was an Irish journalist, managing director of the Abbey Theatre, and politician who served as Minister for Finance from 1923 to 1932, Minister for Posts and Telegraphs and Vice-President of ...

, because he could not speak the Irish language

Irish (an Caighdeán Oifigiúil, Standard Irish: ), also known as Gaelic, is a Goidelic languages, Goidelic language of the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, which is a part of the Indo-European languages, Indo-European lang ...

. At RADA, he was in the same class as Albert Finney

Albert Finney (9 May 1936 – 7 February 2019) was an English actor. He attended the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and worked in the theatre before attaining prominence on screen in the early 1960s, debuting with ''The Entertainer'' (1960), ...

, Alan Bates

Sir Alan Arthur Bates (17 February 1934 – 27 December 2003) was an English actor who came to prominence in the 1960s, when he appeared in films ranging from the popular children's story '' Whistle Down the Wind'' to the " kitchen sink" dram ...

and Brian Bedford

Brian Bedford (16 February 1935 – 13 January 2016) was an English actor. He appeared in film and on stage, and was an actor-director of Shakespeare productions. Bedford was nominated for seven Tony Awards for his theatrical work.

He served ...

. O'Toole described this as "the most remarkable class the academy ever had, though we weren't reckoned for much at the time. We were all considered dotty."

Acting career

1950s

O'Toole began working in the theatre, gaining recognition as a Shakespearean actor at theBristol Old Vic

Bristol Old Vic is a British theatre company based at the Theatre Royal, Bristol. The present company was established in 1946 as an offshoot of the Old Vic in London. It is associated with the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School, which became a f ...

and with the English Stage Company, before making his television debut in 1954. He played a soldier in an episode of '' The Scarlet Pimpernel'' in 1954. He was based at the Bristol Old Vic from 1956 to 1958, appearing in productions of ''King Lear

''King Lear'' is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare.

It is based on the mythological Leir of Britain. King Lear, in preparation for his old age, divides his power and land between two of his daughters. He becomes destitute and insane a ...

'' (1956), '' The Recruiting Officer'' (1956), ''Major Barbara

''Major Barbara'' is a three-act English play by George Bernard Shaw, written and premiered in 1905 and first published in 1907. The story concerns an idealistic young woman, Barbara Undershaft, who is engaged in helping the poor as a Major i ...

'' (1956), ''Othello

''Othello'' (full title: ''The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice'') is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare, probably in 1603, set in the contemporary Ottoman–Venetian War (1570–1573) fought for the control of the Island of Cyp ...

'' (1956), and ''The Slave of Truth'' (1956). He was Henry Higgins in '' Pygmalion'' (1957), Lysander in ''A Midsummer Night's Dream

''A Midsummer Night's Dream'' is a comedy written by William Shakespeare 1595 or 1596. The play is set in Athens, and consists of several subplots that revolve around the marriage of Theseus and Hippolyta. One subplot involves a conflict ...

'' (1957), Uncle Gustve in ''Oh! My Papa!'' (1957), and Jimmy Porter in ''Look Back in Anger

''Look Back in Anger'' (1956) is a realist play written by John Osborne. It focuses on the life and marital struggles of an intelligent and educated but disaffected young man of working-class origin, Jimmy Porter, and his equally competent yet i ...

'' (1957). O'Toole was Tanner in Shaw's '' Man and Superman'' (1958), a performance he reprised often during his career. He was also in ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depi ...

'' (1958), ''The Holiday'' (1958), ''Amphitryon '38'' (1958), and '' Waiting for Godot'' (1958) (as Vladimir). He hoped ''The Holiday'' would take him to the West End but it ultimately folded in the provinces; during that show he met Sian Phillips who became his first wife.

O'Toole continued to appear on television, being in episodes of ''Armchair Theatre

''Armchair Theatre'' is a British television drama anthology series of single plays that ran on the ITV network from 1956 to 1974. It was originally produced by ABC Weekend TV. Its successor Thames Television took over from mid-1968.

The Canad ...

'' ("The Pier", 1957), and '' BBC Sunday-Night Theatre'' ("The Laughing Woman", 1958) and was in the TV adaptation of '' The Castiglioni Brothers'' (1958). He made his London debut in a musical ''Oh, My Papa''. O'Toole gained fame on the West End

West End most commonly refers to:

* West End of London, an area of central London, England

* West End theatre, a popular term for mainstream professional theatre staged in the large theatres of London, England

West End may also refer to:

Pl ...

in the play '' The Long and the Short and the Tall'', performed at the Royal Court starting January 1959. His co-stars included Robert Shaw and Edward Judd and it was directed by Lindsay Anderson. He reprised his performance for television on ''Theatre Night'' in 1959 (although he did not appear in the 1961 film version). The show transferred to the West End in April and won O'Toole Best Actor of the Year in 1959.

1960s

O'Toole was in much demand. He reportedly received five offers of long-term contracts but turned them down. His first role was a small role in Disney's version of ''Kidnapped

Kidnapped may refer to:

* subject to the crime of kidnapping

In criminal law, kidnapping is the unlawful confinement of a person against their will, often including transportation/asportation. The asportation and abduction element is typically ...

'' (1960), playing the bagpipes opposite Peter Finch. His second feature was '' The Savage Innocents'' (1960) with Anthony Quinn

Manuel Antonio Rodolfo Quinn Oaxaca (April 21, 1915 – June 3, 2001), known professionally as Anthony Quinn, was a Mexican-American actor. He was known for his portrayal of earthy, passionate characters "marked by a brutal and elemental ...

for director Nicholas Ray

Nicholas Ray (born Raymond Nicholas Kienzle Jr., August 7, 1911 – June 16, 1979) was an American film director, screenwriter, and actor best known for the 1955 film ''Rebel Without a Cause.'' He is appreciated for many narrative features pr ...

. With his then-wife Sian Phillips he did ''Siwan: The King's Daughter'' (1960) for TV. In 1960 he had a nine-month season at the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford, appearing in ''The Taming of the Shrew

''The Taming of the Shrew'' is a comedy by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1590 and 1592. The play begins with a framing device, often referred to as the induction, in which a mischievous nobleman tricks a drunken ...

'' (as Petruchio), ''The Merchant of Venice

''The Merchant of Venice'' is a play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1596 and 1598. A merchant in Venice named Antonio defaults on a large loan provided by a Jewish moneylender, Shylock.

Although classified as ...

'' (as Shylock) and ''Troilus and Cressida

''Troilus and Cressida'' ( or ) is a play by William Shakespeare, probably written in 1602.

At Troy during the Trojan War, Troilus and Cressida begin a love affair. Cressida is forced to leave Troy to join her father in the Greek camp. M ...

'' (as Thersites). He could have made more money in films but said "You've got to go to Stratford when you've got the chance."

O'Toole had been seen in ''The Long and the Short and the Tall'' by Jules Buck

Jules Buck (July 30, 1917 – July 19, 2001) was an American film producer.

Career

He was a cameraman for John Huston's war documentaries and began producing as assistant to Mark Hellinger.

In 1952 he moved to Paris, then London, where he creat ...

who later established a company with the actor. Buck cast O'Toole in '' The Day They Robbed the Bank of England'' (1961), a heist thriller from director John Guillermin. O'Toole was billed third, beneath Aldo Ray and Elizabeth Sellars. The same year he appeared in several episodes of the TV series '' Rendezvous'' ("End of a Good Man", "Once a Horseplayer", "London-New York"). He lost the role in the film adaptation of ''Long and the Short and the Tall'' to Laurence Harvey. "It broke my heart", he said later.

''Lawrence of Arabia'' (1962)

O'Toole's major break came in November 1960 when he was chosen to play the eponymous hero T. E. Lawrence in Sir David Lean

Sir David Lean (25 March 190816 April 1991) was an English film director, producer, screenwriter and editor. Widely considered one of the most important figures in British cinema, Lean directed the large-scale epics '' The Bridge on the Rive ...

's epic ''Lawrence of Arabia

Thomas Edward Lawrence (16 August 1888 – 19 May 1935) was a British archaeologist, army officer, diplomat, and writer who became renowned for his role in the Arab Revolt (1916–1918) and the Sinai and Palestine Campaign (1915–19 ...

'' (1962), after Albert Finney

Albert Finney (9 May 1936 – 7 February 2019) was an English actor. He attended the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and worked in the theatre before attaining prominence on screen in the early 1960s, debuting with ''The Entertainer'' (1960), ...

reportedly turned down the role. The role introduced him to a global audience and earned him the first of his eight nominations for the Academy Award for Best Actor

The Academy Award for Best Actor is an award presented annually by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). It is given to an actor who has delivered an outstanding performance in a leading role in a film released that year. The a ...

. He received the BAFTA Award for Best British Actor

Best Actor in a Leading Role is a British Academy Film Awards, British Academy Film Award presented annually by the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) to recognize an actor who has delivered an outstanding leading performance in ...

. His performance was ranked number one in ''Premiere

A première, also spelled premiere, is the debut (first public presentation) of a play, film, dance, or musical composition.

A work will often have many premières: a world première (the first time it is shown anywhere in the world), its f ...

'' magazine's list of the 100 Greatest Performances of All Time. In 2003, Lawrence as portrayed by O'Toole was selected as the tenth-greatest hero in cinema history by the American Film Institute

The American Film Institute (AFI) is an American nonprofit film organization that educates filmmakers and honors the heritage of the motion picture arts in the United States. AFI is supported by private funding and public membership fees.

Lead ...

.

O'Toole played Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depi ...

under Laurence Olivier

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier (; 22 May 1907 – 11 July 1989) was an English actor and director who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud, was one of a trio of male actors who dominated the British stage o ...

's direction in the premiere production of the Royal National Theatre

The Royal National Theatre in London, commonly known as the National Theatre (NT), is one of the United Kingdom's three most prominent publicly funded performing arts venues, alongside the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Royal Opera House. I ...

in 1963. He performed in ''Baal

Baal (), or Baal,; phn, , baʿl; hbo, , baʿal, ). ( ''baʿal'') was a title and honorific meaning "owner", " lord" in the Northwest Semitic languages spoken in the Levant during antiquity. From its use among people, it came to be applied ...

'' (1963) at the Phoenix Theatre.

Partnership with Jules Buck

Even prior to the making of ''Lawrence of Arabia'', O'Toole announced he wanted to form a production company with Jules Buck. In November 1961 they said their company, known as Keep Films (also known as Tricolor Productions) would make a film starring Terry-Thomas, '' Operation Snatch''. In 1962 O'Toole and Buck announced they wanted to make a version of ''Waiting for Godot'' for £80,000. The film was never made. Instead their first production was '' Becket'' (1964), where O'Toole played King Henry II opposite Richard Burton. The film, done in association with Hal Wallis, was a financial success. O'Toole turned down the lead role in '' The Cardinal'' (1963). Instead he and Buck made another epic, ''

Even prior to the making of ''Lawrence of Arabia'', O'Toole announced he wanted to form a production company with Jules Buck. In November 1961 they said their company, known as Keep Films (also known as Tricolor Productions) would make a film starring Terry-Thomas, '' Operation Snatch''. In 1962 O'Toole and Buck announced they wanted to make a version of ''Waiting for Godot'' for £80,000. The film was never made. Instead their first production was '' Becket'' (1964), where O'Toole played King Henry II opposite Richard Burton. The film, done in association with Hal Wallis, was a financial success. O'Toole turned down the lead role in '' The Cardinal'' (1963). Instead he and Buck made another epic, ''Lord Jim

''Lord Jim'' is a novel by Joseph Conrad originally published as a serial in ''Blackwood's Magazine'' from October 1899 to November 1900. An early and primary event in the story is the abandonment of a passenger ship in distress by its crew, i ...

'' (1965), based on the novel by Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Polish-British novelist and short story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in the English language; though he did not sp ...

directed by Richard Brooks. He and Buck intended to follow this with a biopic of Will Adams and a film about the Charge of the Light Brigade

The Charge of the Light Brigade was a failed military action involving the British light cavalry led by Lord Cardigan against Russian forces during the Battle of Balaclava on 25 October 1854 in the Crimean War. Lord Raglan had intended to s ...

, but neither project happened. Instead O'Toole went into ''What's New Pussycat?

''What's New Pussycat?'' is a 1965 screwball comedy film directed by Clive Donner, written by Woody Allen in his first produced screenplay, and starring Allen in his acting debut, along with Peter Sellers, Peter O'Toole, Romy Schneider, Capuc ...

'' (1965), a comedy based on a script by Woody Allen

Heywood "Woody" Allen (born Allan Stewart Konigsberg; November 30, 1935) is an American film director, writer, actor, and comedian whose career spans more than six decades and multiple Academy Award-winning films. He began his career writing ...

, taking over a role originally meant for Warren Beatty and starring alongside Peter Sellers

Peter Sellers (born Richard Henry Sellers; 8 September 1925 – 24 July 1980) was an English actor and comedian. He first came to prominence performing in the BBC Radio comedy series ''The Goon Show'', featured on a number of hit comic songs ...

. It was a huge success.

He and Buck helped produce '' The Party's Over'' (1965). O'Toole returned to the stage with ''Ride a Cock Horse'' at the Piccadilly Theatre in 1965, which was harshly reviewed. He made a heist film with Audrey Hepburn

Audrey Hepburn (born Audrey Kathleen Ruston; 4 May 1929 – 20 January 1993) was a British actress and humanitarian. Recognised as both a film and fashion icon, she was ranked by the American Film Institute as the third-greatest female screen ...

, ''How to Steal a Million

''How to Steal a Million'' is a 1966 American heist comedy film directed by William Wyler and starring Audrey Hepburn, Peter O'Toole, Eli Wallach, Hugh Griffith, and Charles Boyer. The film is set and was filmed in Paris, though the character ...

'' (1966), directed by William Wyler

William Wyler (; born Willi Wyler (); July 1, 1902 – July 27, 1981) was a Swiss-German-American film director and producer who won the Academy Award for Best Director three times, those being for '' Mrs. Miniver'' (1942), '' The Best Years o ...

. He played the Three Angels in the all-star '' The Bible: In the Beginning...'' (1966), directed by John Huston

John Marcellus Huston ( ; August 5, 1906 – August 28, 1987) was an American film director, screenwriter, actor and visual artist. He wrote the screenplays for most of the 37 feature films he directed, many of which are today considered ...

. In 1966 at the Gaiety Theatre in Dublin he appeared in productions of '' Juno and the Paycock'' and '' Man and Superman''. Sam Spiegel, producer of ''Lawrence of Arabia'', reunited O'Toole with Omar Sharif in '' The Night of the Generals'' (1967), which was a box office disappointment. O'Toole played in an adaptation of Noël Coward

Sir Noël Peirce Coward (16 December 189926 March 1973) was an English playwright, composer, director, actor, and singer, known for his wit, flamboyance, and what ''Time (magazine), Time'' magazine called "a sense of personal style, a combina ...

's '' Present Laughter'' for TV in 1968, and had a cameo in '' Casino Royale'' (1967).

The Lion in Winter'' (1968)

He played Henry II again in ''

He played Henry II again in ''The Lion in Winter

''The Lion in Winter'' is a 1966 play by James Goldman, depicting the personal and political conflicts of Henry II of England, his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine, their children and their guests during Christmas 1183. It premiered on Broadway at the ...

'' (1968) alongside Katharine Hepburn

Katharine Houghton Hepburn (May 12, 1907 – June 29, 2003) was an American actress in film, stage, and television. Her career as a Hollywood leading lady spanned over 60 years. She was known for her headstrong independence, spirited perso ...

, and was nominated for an Oscar again – one of the few times an actor had been nominated playing the same character in different films. The film was also successful at the box office.

Less popular was '' Great Catherine'' (1968) with Jeanne Moreau

Jeanne Moreau (; 23 January 1928 – 31 July 2017) was a French actress, singer, screenwriter, director, and socialite. She made her theatrical debut in 1947, and established herself as one of the leading actresses of the Comédie-Française. M ...

, an adaptation of the play by George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

which Buck and O'Toole co-produced.

''Goodbye Mr Chips'' (1969)

In 1969, he played the title role in the film '' Goodbye, Mr. Chips'', a musical adaptation of James Hilton's novella, starring opposite Petula Clark. He was nominated for an Academy Award as Best Actor and won a Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy. O'Toole fulfilled a lifetime ambition in 1970 when he performed on stage in Samuel Beckett

Samuel Barclay Beckett (; 13 April 1906 – 22 December 1989) was an Irish novelist, dramatist, short story writer, theatre director, poet, and literary translator. His literary and theatrical work features bleak, impersonal and tragicomic ex ...

's '' Waiting for Godot'', alongside Donal McCann

Donal McCann (7 May 1943 – 17 July 1999) was an Irish stage, film, and television actor best known for his roles in the works of Brian Friel and for his lead role in John Huston's last film, ''The Dead''. In 2020, he was listed as number 4 ...

, at Dublin's Abbey Theatre

The Abbey Theatre ( ga, Amharclann na Mainistreach), also known as the National Theatre of Ireland ( ga, Amharclann Náisiúnta na hÉireann), in Dublin, Ireland, is one of the country's leading cultural institutions. First opening to the pu ...

.

In other films he played a man in love with his sister (played by Susannah York) in '' Country Dance'' (1970). O'Toole starred in a war film for director Peter Yates, '' Murphy's War'' (1971), appearing alongside Sian Phillips. He was reunited with Richard Burton in a film version of ''Under Milk Wood

''Under Milk Wood'' is a 1954 radio drama by Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, commissioned by the BBC and later adapted for the stage. A film version, '' Under Milk Wood'' directed by Andrew Sinclair, was released in 1972, and another adaptatio ...

'' (1972) by Dylan Thomas

Dylan Marlais Thomas (27 October 1914 – 9 November 1953) was a Welsh poet and writer whose works include the poems " Do not go gentle into that good night" and " And death shall have no dominion", as well as the "play for voices" ''Unde ...

, produced by himself and Buck; Elizabeth Taylor

Dame Elizabeth Rosemond Taylor (February 27, 1932 – March 23, 2011) was a British-American actress. She began her career as a child actress in the early 1940s and was one of the most popular stars of classical Hollywood cinema in the 1950s. ...

co-starred. The film was not a popular success.

1970s

''The Ruling Class'' (1972) O'Toole received another Oscar nomination for his performance in '' The Ruling Class'' (1972), done for his own company. In 1972, he played bothMiguel de Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (; 29 September 1547 (assumed) – 22 April 1616 NS) was an Early Modern Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelists. He is best know ...

and his fictional creation Don Quixote

is a Spanish epic novel by Miguel de Cervantes. Originally published in two parts, in 1605 and 1615, its full title is ''The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha'' or, in Spanish, (changing in Part 2 to ). A founding work of Wester ...

in ''Man of La Mancha

''Man of La Mancha'' is a 1965 musical with a book by Dale Wasserman, music by Mitch Leigh, and lyrics by Joe Darion. It is adapted from Wasserman's non-musical 1959 teleplay '' I, Don Quixote'', which was in turn inspired by Miguel de Cerva ...

'', the motion picture adaptation of the 1965 hit Broadway musical, opposite Sophia Loren

Sofia Costanza Brigida Villani Scicolone (; born 20 September 1934), known professionally as Sophia Loren ( , ), is an Italian actress. She was named by the American Film Institute as one of the greatest female stars of Classical Hollywood ci ...

. The film was a critical and commercial failure, criticised for using mostly non-singing actors. His singing was dubbed by tenor

A tenor is a type of classical male singing voice whose vocal range lies between the countertenor and baritone voice types. It is the highest male chest voice type. The tenor's vocal range extends up to C5. The low extreme for tenors i ...

Simon Gilbert, but the other actors did their own singing. O'Toole and co-star James Coco, who played both Cervantes's manservant and Sancho Panza

Sancho Panza () is a fictional character in the novel ''Don Quixote'' written by Spanish author Don Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra in 1605. Sancho acts as squire to Don Quixote and provides comments throughout the novel, known as ''sanchismos'', ...

, both received Golden Globe

The Golden Globe Awards are accolades bestowed by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association beginning in January 1944, recognizing excellence in both American and international film and television. Beginning in 2022, there are 105 members of t ...

nominations for their performances.

O'Toole did not make a film for several years. He performed at the Bristol Old Vic from 1973 to 1974 in ''Uncle Vanya

''Uncle Vanya'' ( rus, Дя́дя Ва́ня, r=Dyádya Ványa, p=ˈdʲædʲə ˈvanʲə) is a play by the Russian playwright Anton Chekhov. It was first published in 1898, and was first produced in 1899 by the Moscow Art Theatre under the dire ...

'', ''Plunder'', ''The Apple Cart

''The Apple Cart: A Political Extravaganza'' is a 1928 play by George Bernard Shaw. It is a satirical comedy about several political philosophies which are expounded by the characters, often in lengthy monologues. The plot follows the fictional ...

'' and ''Judgement''. He returned to films with '' Rosebud'' (1975), a flop thriller for Otto Preminger

Otto Ludwig Preminger ( , ; 5 December 1905 – 23 April 1986) was an Austrian-American theatre and film director, film producer, and actor.

He directed more than 35 feature films in a five-decade career after leaving the theatre. He first gai ...

, where O'Toole replaced Robert Mitchum

Robert Charles Durman Mitchum (August 6, 1917 – July 1, 1997) was an American actor. He rose to prominence with an Academy Award nomination for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, Best Supporting Actor for ''The Story of G.I. Jo ...

at the last minute. He followed it with '' Man Friday'' (1975), an adaptation of the Robinson Crusoe

''Robinson Crusoe'' () is a novel by Daniel Defoe, first published on 25 April 1719. The first edition credited the work's protagonist Robinson Crusoe as its author, leading many readers to believe he was a real person and the book a tr ...

story, which was the last work from Keep Films. O'Toole made ''Foxtrot

The foxtrot is a smooth, progressive dance characterized by long, continuous flowing movements across the dance floor. It is danced to big band (usually vocal) music. The dance is similar in its look to waltz, although the rhythm is in a ti ...

'' (1976), directed by Arturo Ripstein. He was critically acclaimed for his performance in '' Rogue Male'' (1976) for British television. He did ''Dead Eyed Dicks'' on stage in Sydney in 1976. Less well received was '' Power Play'' (1978), made in Canada, and '' Zulu Dawn'' (1979), shot in South Africa. He toured ''Uncle Vanya

''Uncle Vanya'' ( rus, Дя́дя Ва́ня, r=Dyádya Ványa, p=ˈdʲædʲə ˈvanʲə) is a play by the Russian playwright Anton Chekhov. It was first published in 1898, and was first produced in 1899 by the Moscow Art Theatre under the dire ...

'' and '' Present Laughter'' on stage. In 1979, O'Toole starred as Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was the second Roman emperor. He reigned from AD 14 until 37, succeeding his stepfather, the first Roman emperor Augustus. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC. His father ...

in the '' Penthouse''-funded biopic, ''Caligula

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (31 August 12 – 24 January 41), better known by his nickname Caligula (), was the third Roman emperor, ruling from 37 until his assassination in 41. He was the son of the popular Roman general Germanic ...

''.

1980s

''The Stunt Man'' (1980) In 1980, he received critical acclaim for playing the director in the behind-the-scenes film ''The Stunt Man

''The Stunt Man'' is a 1980 American action comedy film directed by Richard Rush, starring Peter O'Toole, Steve Railsback, and Barbara Hershey. The film was adapted by Lawrence B. Marcus and Rush from the 1970 novel of the same name by Paul Br ...

''. His performance earned him an Oscar nomination. He appeared in a mini series for Irish TV ''Strumpet City

''Strumpet City'' is a 1969 historical novel by James Plunkett set in Dublin, Ireland, around the time of the 1913 Dublin Lock-out. In 1980, it was adapted into a successful TV drama by Hugh Leonard for RTÉ, Ireland's national broadcaster. The ...

'', where he played James Larkin

James Larkin (28 January 1874 – 30 January 1947), sometimes known as Jim Larkin or Big Jim, was an Irish republicanism, Irish republican, socialist and trade union leader. He was one of the founders of the Irish Labour Party (Ireland), Labou ...

. He followed this with another mini series ''Masada

Masada ( he, מְצָדָה ', "fortress") is an ancient fortification in the Southern District of Israel situated on top of an isolated rock plateau, akin to a mesa. It is located on the eastern edge of the Judaean Desert, overlooking the ...

'' (1981), playing Lucius Flavius Silva. In 1980 he performed in ''MacBeth

''Macbeth'' (, full title ''The Tragedie of Macbeth'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It is thought to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the damaging physical and psychological effects of political ambition on those w ...

'' at the Old Vic for $500 a week (), a performance that famously earned O'Toole some of the worst reviews of his career.

''My Favorite Year'' (1982)

O'Toole was nominated for another Oscar for '' My Favorite Year'' (1982), a light romantic comedy about the behind-the-scenes at a 1950s TV variety-comedy show, in which O'Toole plays an ageing swashbuckling film star reminiscent of Errol Flynn. He returned to the stage in London with a performance in ''Man and Superman'' (1982) that was better received than his ''MacBeth''. He focused on television, doing an adaptation of '' Man and Superman'' (1983), '' Svengali'' (1983), ''Pygmalion'' (1984), and ''Kim

Kim or KIM may refer to:

Names

* Kim (given name)

* Kim (surname)

** Kim (Korean surname)

*** Kim family (disambiguation), several dynasties

**** Kim family (North Korea), the rulers of North Korea since Kim Il-sung in 1948

** Kim, Vietnamese ...

'' (1984), and providing the voice of Sherlock Holmes for a series of animated TV movies. He did ''Pygmalion'' on stage in 1984 at the West End's Shaftesbury Theatre

The Shaftesbury Theatre is a West End theatre, located on Shaftesbury Avenue, in the London Borough of Camden. Opened in 1911 as the New Prince's Theatre, it was the last theatre to be built in Shaftesbury Avenue.

History

The theatre was d ...

.

O'Toole returned to feature films in '' Supergirl'' (1984), '' Creator'' (1985), '' Club Paradise'' (1986), '' The Last Emperor'' (1987) as Sir Reginald Johnston, and '' High Spirits'' (1988). He appeared on Broadway in an adaptation of '' Pygmalion'' (1987), opposite Amanda Plummer. It ran for 113 performances.

''Jeffrey Bernard Is Unwell'' (1989)

He won a Laurence Olivier Award

The Laurence Olivier Awards, or simply the Olivier Awards, are presented annually by the Society of London Theatre to recognise excellence in professional theatre in London at an annual ceremony in the capital. The awards were originally known a ...

for his performance in '' Jeffrey Bernard Is Unwell'' (1989). His other appearances that decade include '' Uncle Silas'' (1989) for television.

1990s

O'Toole's performances in the 1990s include '' Wings of Fame'' (1990); ''The Rainbow Thief

''The Rainbow Thief'' is a 1990 film directed by filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky and written by Berta Domínguez D. It reunites '' Lawrence of Arabia'' co-stars Peter O'Toole and Omar Sharif in a fable of friendship. Christopher Lee also play ...

'' (1990), with Sharif; '' King Ralph'' (1991) with John Goodman

John Stephen Goodman (born June 20, 1952) is an American actor. He gained national fame for his role as the family patriarch Dan Conner in the ABC comedy series '' Roseanne'' (1988–1997; 2018), for which he received a Golden Globe Award, a ...

; ''Isabelle Eberhardt

Isabelle Wilhelmine Marie Eberhardt (17 February 1877 – 21 October 1904) was a Swiss explorer and author. As a teenager, Eberhardt, educated in Switzerland by her father, published short stories under a male pseudonym. She became interested ...

'' (1992); '' Rebecca's Daughters'' (1992), in Wales; '' Civvies'' (1992), a British TV series; '' The Seventh Coin'' (1993); '' Heaven & Hell: North & South, Book III'' (1994), for American TV; and '' Heavy Weather'' (1995), for British TV. He was in an adaptation of ''Gulliver's Travels

''Gulliver's Travels'', or ''Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World. In Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships'' is a 1726 prose satire by the Anglo-Irish writer and clergyman Jonathan ...

'' (1996), playing the Emperor of Lilliput; '' FairyTale: A True Story'' (1997), playing Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (22 May 1859 – 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for ''A Study in Scarlet'', the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Hol ...

; ''Phantoms

Phantom may refer to:

* Spirit (animating force), the vital principle or animating force within all living things

** Ghost, the soul or spirit of a dead person or animal that can appear to the living

Aircraft

* Boeing Phantom Ray, a stealthy unm ...

'' (1998), from a novel by Dean Koontz

Dean Ray Koontz (born July 9, 1945) is an American author. His novels are billed as suspense thrillers, but frequently incorporate elements of horror, fantasy, science fiction, mystery, and satire. Many of his books have appeared on ''The New ...

; and '' Molokai: The Story of Father Damien'' (1999). He won a Primetime Emmy Award

The Primetime Emmy Awards, or Primetime Emmys, are part of the extensive range of Emmy Awards for artistic and technical merit for the American television industry. Bestowed by the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (ATAS), the Primetime ...

for his role as Bishop Pierre Cauchon in the 1999 mini-series ''Joan of Arc

Joan of Arc (french: link=yes, Jeanne d'Arc, translit= �an daʁk} ; 1412 – 30 May 1431) is a patron saint of France, honored as a defender of the French nation for her role in the siege of Orléans and her insistence on the corona ...

''. He also produced and starred in a TV adaptation of '' Jeffrey Bernard Is Unwell'' (1999).

2000s

O'Toole's work in the next decade included '' Global Heresy'' (2002); ''The Final Curtain

''The Final Curtain'' is a compilation album and DVD by the Pompano Beach, Florida Rock music, rock band Further Seems Forever, released in 2007 by 567 Records. The album includes the band's final live performance recorded on June 17, 2006 at Th ...

'' (2003); '' Bright Young Things'' (2003); '' Hitler: The Rise of Evil'' (2003) for TV, as Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (; abbreviated ; 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German field marshal and statesman who led the Imperial German Army during World War I and later became President of Germany fr ...

; and '' Imperium: Augustus'' (2004) as Augustus Caesar

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Principate ...

. In 2004, he played King Priam in ''Troy

Troy ( el, Τροία and Latin: Troia, Hittite: 𒋫𒊒𒄿𒊭 ''Truwiša'') or Ilion ( el, Ίλιον and Latin: Ilium, Hittite: 𒃾𒇻𒊭 ''Wiluša'') was an ancient city located at Hisarlik in present-day Turkey, south-west of Çan ...

''. In 2005, he appeared on television as the older version of legendary 18th century Italian adventurer Giacomo Casanova

Giacomo Girolamo Casanova (, ; 2 April 1725 – 4 June 1798) was an Italian adventurer and author from the Republic of Venice. His autobiography, (''Story of My Life''), is regarded as one of the most authentic sources of information about the c ...

in the BBC drama serial '' Casanova''. The younger Casanova, seen for most of the action, was played by David Tennant

David John Tennant ('' né'' McDonald; born 18 April 1971) is a Scottish actor. He rose to fame for his role as the tenth incarnation of the Doctor (2005–2010 and 2013) in the BBC science-fiction TV show '' Doctor Who'', reprising the ...

, who had to wear contact lenses to match his brown eyes to O'Toole's blue. He followed it with a role in '' Lassie'' (2005).

''Venus'' (2006)

O'Toole was once again nominated for the Best Actor Academy Award for his portrayal of Maurice in the 2006 film ''Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never f ...

'', directed by Roger Michell

Roger Michell (5 June 1956 – 22 September 2021) was a South African-born British theatre, television and film director. He was best known for directing films such as ''Notting Hill'' and ''Venus'', as well as the 1995 made-for-television fi ...

, his eighth such nomination. He was in '' One Night with the King'' (2007) and co-starred in the Pixar

Pixar Animation Studios (commonly known as Pixar () and stylized as P I X A R) is an American computer animation studio known for its critically and commercially successful computer animated feature films. It is based in Emeryville, Californ ...

animated film ''Ratatouille

Ratatouille ( , ), oc, ratatolha , is a French Provençal dish of stewed vegetables which originated in Nice, and is sometimes referred to as ''ratatouille niçoise'' (). Recipes and cooking times differ widely, but common ingredients include ...

'' (2007), an animated film about a rat with dreams of becoming the greatest chef in Paris, as Anton Ego, a food critic. He had a small role in ''Stardust

Stardust may refer to:

* A type of cosmic dust, composed of particles in space

Entertainment Songs

* “Stardust” (1927 song), by Hoagy Carmichael

* “Stardust” (David Essex song), 1974

* “Stardust” (Lena Meyer-Landrut song), 2012

* ...

'' (2007). He also appeared in the second season of Showtime

Showtime or Show Time may refer to:

Film

* ''Showtime'' (film), a 2002 American action/comedy film

* ''Showtime'' (video), a 1995 live concert video by Blur

Television Networks and channels

* Showtime Networks, a division of Paramount Global ...

's drama series '' The Tudors'' (2008), portraying Pope Paul III

Pope Paul III ( la, Paulus III; it, Paolo III; 29 February 1468 – 10 November 1549), born Alessandro Farnese, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 October 1534 to his death in November 1549.

He came to ...

, who excommunicate

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

s King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disagr ...

from the church; an act which leads to a showdown between the two men in seven of the ten episodes. Also in 2008, he starred alongside Jeremy Northam and Sam Neill in the New Zealand/British film '' Dean Spanley'', based on an Alan Sharp adaptation of Irish author Lord Dunsany's short novel, ''My Talks with Dean Spanley''.

He was in ''Thomas Kinkade's Christmas Cottage

''Thomas Kinkade's Christmas Cottage'' is a 2008 Christmas biopic directed by Michael Campus, the first film he had directed in more than 30 years. It stars Jared Padalecki as painter Thomas Kinkade and features Peter O'Toole, Marcia Gay Harden and ...

'' (2008); and '' Iron Road'' (2009), a Canadian-Chinese miniseries. O'Toole's final performances came in '' Highway to Hell'' (2012) and '' For Greater Glory: The True Story of Cristiada'' (2012). On 10 July 2012, O'Toole released a statement announcing his retirement from acting. A number of films were released after his retirement and death: ''Decline of an Empire

''Decline of an Empire'' is a 2014 British biographical historical drama film, produced and directed by Michael Redwood, about the life of Catherine of Alexandria. It is one of the last film roles of Peter O'Toole, who died before the film was r ...

'' (2013), as Gallus; and '' Diamond Cartel'' (2017).

Personal life

Personal views

While studying at RADA in the early 1950s, O'Toole was active in protesting against British involvement in theKorean War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Korean War

, partof = the Cold War and the Korean conflict

, image = Korean War Montage 2.png

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Clockwise from top: ...

. Later, in the 1960s, he was an active opponent of the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

. He played a role in the creation of the current form of the well-known folk song "Carrickfergus

Carrickfergus ( , meaning " Fergus' rock") is a large town in County Antrim, Northern Ireland. It sits on the north shore of Belfast Lough, from Belfast. The town had a population of 27,998 at the 2011 Census. It is County Antrim's oldest ...

" which he related to Dominic Behan, who put it in print and made a recording in the mid-1960s.

Although he lost faith in organised religion as a teenager, O'Toole expressed positive sentiments regarding the life of Jesus Christ. In an interview for ''The New York Times'', he said "No one can take Jesus away from me... there's no doubt there was a historical figure of tremendous importance, with enormous notions. Such as peace." He called himself "a retired Christian" who prefers "an education and reading and facts" to faith.

Relationships

In 1959, he married Welsh actress Siân Phillips, with whom he had two daughters: actressKate Kate name may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Kate (given name), a list of people and fictional characters with the given name or nickname

* Gyula Káté (born 1982), Hungarian amateur boxer

* Lauren Kate (born 1981), American aut ...

and Patricia. They were divorced in 1979. Phillips later said in two autobiographies that O'Toole had subjected her to mental cruelty, largely fuelled by drinking, and was subject to bouts of extreme jealousy when she finally left him for a younger lover.

O'Toole and his girlfriend, model Karen Brown, had a son, Lorcan O'Toole (born 17 March 1983), when O'Toole was fifty years old. Lorcan, now an actor, was a pupil at Harrow School

Harrow School () is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school (English Independent school (United Kingdom), independent boarding school for boys) in Harrow on the Hill, Greater London, England. The school was founded in 1572 by John Lyon (sc ...

, boarding at West Acre from 1996.

Sports

O'Toole playedrugby league

Rugby league football, commonly known as just rugby league and sometimes football, footy, rugby or league, is a full-contact sport played by two teams of thirteen players on a rectangular field measuring 68 metres (75 yards) wide and 112 ...

as a child in Leeds and was also a rugby union

Rugby union, commonly known simply as rugby, is a Contact sport#Terminology, close-contact team sport that originated at Rugby School in the first half of the 19th century. One of the Comparison of rugby league and rugby union, two codes of ru ...

fan, attending Five Nations matches with friends and fellow rugby fans Richard Harris, Kenneth Griffith, Peter Finch and Richard Burton

Richard Burton (; born Richard Walter Jenkins Jr.; 10 November 1925 – 5 August 1984) was a Welsh actor. Noted for his baritone voice, Burton established himself as a formidable Shakespearean actor in the 1950s, and he gave a memorable p ...

. He was also a lifelong player, coach and enthusiast of cricket and a fan of Sunderland A.F.C. His support of Sunderland was passed on to him through his father, who was a labourer in Sunderland

Sunderland () is a port city in Tyne and Wear, England. It is the City of Sunderland's administrative centre and in the Historic counties of England, historic county of County of Durham, Durham. The city is from Newcastle-upon-Tyne and is on t ...

for many years. He was named their most famous fan. The actor in a later interview expressed that he no longer considered himself as much of a fan following the demolition of Roker Park and the subsequent move to the Stadium of Light. He described Roker Park as his last connection to the club and that everything "they meant to him was when they were at Roker Park".

O'Toole was interviewed at least three times by Charlie Rose

Charles Peete Rose Jr. (born January 5, 1942) is an American former television journalist and talk show host. From 1991 to 2017, he was the host and executive producer of the talk show '' Charlie Rose'' on PBS and Bloomberg LP.

Rose also co- ...

on his eponymous talk show

A talk show (or chat show in British English) is a television programming or radio programming genre structured around the act of spontaneous conversation.Bernard M. Timberg, Robert J. Erler'' (2010Television Talk: A History of the TV Talk S ...

. In a 17 January 2007 interview, O'Toole stated that British actor Eric Porter

Eric Richard Porter (8 April 192815 May 1995) was an English actor of stage, film and television.

Early life

Porter was born in Shepherd's Bush, London, to bus conductor Richard John Porter and Phoebe Elizabeth (née Spall). His parents hop ...

had most influenced him, adding that the difference between actors of yesterday and today is that actors of his generation were trained for "theatre, theatre, theatre". He also believes that the challenge for the actor is "to use his imagination to link to his emotion" and that "good parts make good actors". However, in other venues (including the DVD commentary for '' Becket''), O'Toole credited Donald Wolfit as being his most important mentor.

Health

Severe illness almost ended O'Toole's life in the late 1970s. His stomach cancer was misdiagnosed as resulting from his alcoholic excess. O'Toole underwent surgery in 1976 to have hispancreas

The pancreas is an organ of the digestive system and endocrine system of vertebrates. In humans, it is located in the abdomen behind the stomach and functions as a gland. The pancreas is a mixed or heterocrine gland, i.e. it has both an en ...

and a large portion of his stomach removed, which resulted in insulin

Insulin (, from Latin ''insula'', 'island') is a peptide hormone produced by beta cells of the pancreatic islets encoded in humans by the ''INS'' gene. It is considered to be the main anabolic hormone of the body. It regulates the metabol ...

-dependent diabetes

Diabetes, also known as diabetes mellitus, is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by a high blood sugar level (hyperglycemia) over a prolonged period of time. Symptoms often include frequent urination, increased thirst and increased ...

. In 1978, he nearly died from a blood disorder. He eventually recovered and returned to work. He resided on the Sky Road, just outside Clifden, Connemara

Connemara (; )( ga, Conamara ) is a region on the Atlantic coast of western County Galway, in the west of Ireland. The area has a strong association with traditional Irish culture and contains much of the Connacht Irish-speaking Gaeltacht, w ...

, County Galway from 1963, and at the height of his career maintained homes in Dublin, London and Paris (at the Ritz

Ritz or The Ritz may refer to:

Facilities and structures Hotels

* The Ritz Hotel, London, a hotel in London, England

* Hôtel Ritz Paris, a hotel in Paris, France

* Hotel Ritz (Madrid), a hotel in Madrid, Spain

* Hotel Ritz (Lisbon), a hotel in ...

, which was where his character supposedly lived in the film ''How to Steal a Million

''How to Steal a Million'' is a 1966 American heist comedy film directed by William Wyler and starring Audrey Hepburn, Peter O'Toole, Eli Wallach, Hugh Griffith, and Charles Boyer. The film is set and was filmed in Paris, though the character ...

'').

In an interview with National Public Radio

National Public Radio (NPR, stylized in all lowercase) is an American privately and state funded nonprofit media organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., with its NPR West headquarters in Culver City, California. It differs from othe ...

in December 2006, O'Toole revealed that he knew all 154 of Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

's sonnet

A sonnet is a poetic form that originated in the poetry composed at the Court of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II in the Sicilian city of Palermo. The 13th-century poet and notary Giacomo da Lentini is credited with the sonnet's inventio ...

s. A self-described romantic, O'Toole said of the sonnets that nothing in the English language compares with them, and read them daily. In ''Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never f ...

'', he recites Sonnet 18 ("Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?"). O'Toole wrote two memoirs. ''Loitering With Intent: The Child'' chronicles his childhood in the years leading up to World War II and was a ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' Notable Book of the Year in 1992. His second, ''Loitering With Intent: The Apprentice'', is about his years spent training with a cadre of friends at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art

The Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA; ) is a drama school in London, England, that provides vocational conservatoire training for theatre, film, television, and radio. It is based in the Bloomsbury area of Central London, close to the Sena ...

.

Death

O'Toole retired from acting in July 2012 owing to a recurrence of stomach cancer. He died on 14 December 2013 at

O'Toole retired from acting in July 2012 owing to a recurrence of stomach cancer. He died on 14 December 2013 at Wellington Hospital Wellington Hospital might refer to:

* Wellington Hospital, New Zealand, a hospital in Wellington, New Zealand

* Wellington Hospital, London

The Wellington Hospital in St John's Wood, London is the largest private hospital in the United Kingdom, an ...

in St John's Wood

St John's Wood is a district in the City of Westminster, London, lying 2.5 miles (4 km) northwest of Charing Cross. Traditionally the northern part of the ancient parish and Metropolitan Borough of Marylebone, it extends east to west fr ...

, London, at the age of 81. His funeral was held at Golders Green Crematorium

Golders Green Crematorium and Mausoleum was the first crematorium to be opened in London, and one of the oldest crematoria in Britain. The land for the crematorium was purchased in 1900, costing £6,000 (the equivalent of £135,987 in 2021), ...

in London on 21 December 2013, where his body was cremated in a wicker coffin. His family stated their intention to fulfil his wishes and take his ashes to the west of Ireland.

Legacy

On 18 May 2014, a new prize was launched in memory of Peter O'Toole at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School; this includes an annual award given to two young actors from the School, including a professional contract at Bristol Old Vic Theatre. He has a memorial plaque in St Paul's, the Actors' Church inCovent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist sit ...

, London.

On 21 April 2017, the Harry Ransom Center

The Harry Ransom Center (until 1983 the Humanities Research Center) is an archive, library and museum at the University of Texas at Austin, specializing in the collection of literary and cultural artifacts from the Americas and Europe for the pu ...

at the University of Texas at Austin

The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin, UT, or Texas) is a public research university in Austin, Texas. It was founded in 1883 and is the oldest institution in the University of Texas System. With 40,916 undergraduate students, 11,075 ...

announced that Kate O'Toole had placed her father's archive at the humanities research centre. The collection includes O'Toole's scripts, extensive published and unpublished writings, props, photographs, letters, medical records, and more. It joins the archives of several of O'Toole's collaborators and friends including Donald Wolfit, Eli Wallach, Peter Glenville, Sir Tom Stoppard

Sir Tom Stoppard (born , 3 July 1937) is a Czech born British playwright and screenwriter. He has written for film, radio, stage, and television, finding prominence with plays. His work covers the themes of human rights, censorship, and politi ...

, and Dame Edith Evans.

Acting credits

Awards and honours

O'Toole was the recipient of numerous nominations and awards. He was offered aknighthood

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the Christian denomination, church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood ...

but rejected it in objection to Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. She was the first female British prime ...

's policies. He received four Golden Globe Award

The Golden Globe Awards are accolades bestowed by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association beginning in January 1944, recognizing excellence in both American and international film and television. Beginning in 2022, there are 105 members of t ...

s, one BAFTA Award for Best British Actor

Best Actor in a Leading Role is a British Academy Film Awards, British Academy Film Award presented annually by the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) to recognize an actor who has delivered an outstanding leading performance in ...

(for ''Lawrence of Arabia'') and one Primetime Emmy Award

The Primetime Emmy Awards, or Primetime Emmys, are part of the extensive range of Emmy Awards for artistic and technical merit for the American television industry. Bestowed by the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (ATAS), the Primetime ...

.

Academy Award nominations

O'Toole was nominated eight times for the Academy Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role

Best or The Best may refer to:

People

* Best (surname), people with the surname Best

* Best (footballer, born 1968), retired Portuguese footballer

Companies and organizations

* Best & Co., an 1879–1971 clothing chain

* Best Lock Corporation ...

, but was never able to win a competitive Oscar. In 2002, the Academy honoured him with an Academy Honorary Award

The Academy Honorary Award – instituted in 1950 for the 23rd Academy Awards (previously called the Special Award, which was first presented at the 1st Academy Awards in 1929) – is given annually by the Board of Governors of the Academy of M ...

for his entire body of work and his lifelong contribution to film. O'Toole initially balked about accepting, and wrote the Academy a letter saying that he was "still in the game" and would like more time to "win the lovely bugger outright". The Academy informed him that they would bestow the award whether he wanted it or not. He told ''Charlie Rose

Charles Peete Rose Jr. (born January 5, 1942) is an American former television journalist and talk show host. From 1991 to 2017, he was the host and executive producer of the talk show '' Charlie Rose'' on PBS and Bloomberg LP.

Rose also co- ...

'' in January 2007 that his children admonished him, saying that it was the highest honour one could receive in the filmmaking industry. O'Toole agreed to appear at the ceremony and receive his Honorary Oscar. It was presented to him by Meryl Streep

Mary Louise Meryl Streep (born June 22, 1949) is an American actress. Often described as "the best actress of her generation", Streep is particularly known for her versatility and accent adaptability. She has received numerous accolades throu ...

, who has the most Oscar nominations of any actor or actress (19). He joked with Robert Osborne, during an interview at Turner Classic Movies

Turner Classic Movies (TCM) is an American movie-oriented pay-TV network owned by Warner Bros. Discovery. Launched in 1994, Turner Classic Movies is headquartered at Turner's Techwood broadcasting campus in the Midtown business district of ...

' film festival that he's the "Biggest Loser of All Time", due to his lack of an Academy Award, after many nominations.

Bibliography

* ''Loitering with Intent: The Child'' (1992) * ''Loitering with Intent: The Apprentice'' (1997)See also

* List of British Academy Award nominees and winners *List of actors with Academy Award nominations

This list of actors with Academy Award nominations includes all male and female actors with Academy Award nominations for lead and supporting roles in motion pictures, and the total nominations and wins for each actor. Nominations in non-acting c ...

* List of actors with two or more Academy Award nominations in acting categories

Notes

References

External links

* * * * *"Peter O'Toole as Casanova"

University of Bristol Theatre Collection

University of Bristol

The University of Bristol is a Red brick university, red brick Russell Group research university in Bristol, England. It received its royal charter in 1909, although it can trace its roots to a Society of Merchant Venturers, Merchant Venturers' sc ...

The Making of ''Lawrence of Arabia''

Digitised BAFTA Journal, Winter 1962–63 (with additional notes by Bryan Hewitt)

Peter O'Toole Interview at 2002 Telluride Film Festival

conducted by

Roger Ebert

Roger Joseph Ebert (; June 18, 1942 – April 4, 2013) was an American film critic, film historian, journalist, screenwriter, and author. He was a film critic for the ''Chicago Sun-Times'' from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, Ebert beca ...

Peter O'Toole

(Aveleyman) {{DEFAULTSORT:Otoole, Peter 1932 births 2013 deaths 20th-century English male actors 21st-century English male actors Academy Honorary Award recipients Alumni of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art Best British Actor BAFTA Award winners Best Drama Actor Golden Globe (film) winners Best Musical or Comedy Actor Golden Globe (film) winners David di Donatello winners British people of Irish descent British people of Scottish descent British male film actors British male Shakespearean actors British male stage actors British male television actors British male voice actors Irish people of Scottish descent Irish male film actors Irish male stage actors Irish male television actors Irish male voice actors New Star of the Year (Actor) Golden Globe winners Outstanding Performance by a Supporting Actor in a Miniseries or Movie Primetime Emmy Award winners People with type 1 diabetes Royal Navy sailors Royal Shakespeare Company members People from Hunslet