Monopoly profit on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Monopoly profit is an inflated level of profit due to the monopolistic practices of an enterprise.Bradley R. Chiller, "Essentials of Economics", New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1991.

"GM, Ford, and Chrysler: The Detroit Three Are Back, Right?"

April 4, 2013.

Drake Bennett, "BusinessWeek"

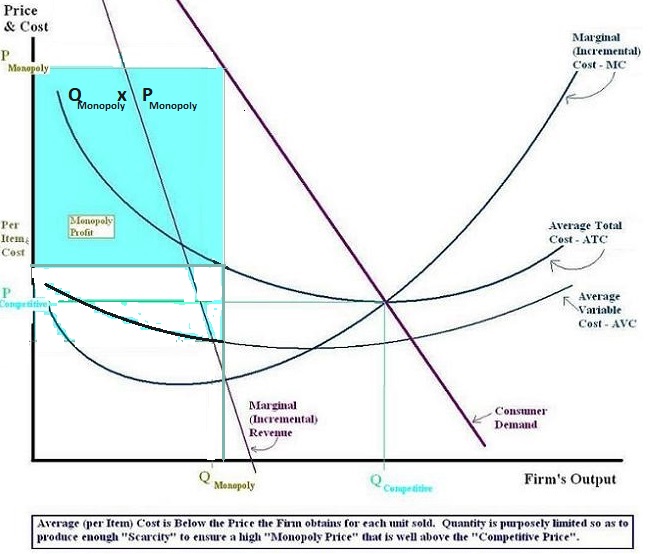

''The Debate Room'', April 4, 2013. By contrast, the lack of competition in a market ensures the firm (monopoly) has a downward sloping demand curve. Although raising prices causes the monopoly to lose some business, some sales can be made at higher prices. Although monopolists are constrained by consumer demand, they are not "price takers" because they can influence price through their production decisions. The monopolist can either have a ''target level of output'' that will ensure the monopoly price as the given consumer demand in the industry's market reacts to the fixed and limited market supply, or it can set a fixed monopoly price at the onset and adjust

By contrast, the lack of competition in a market ensures the firm (monopoly) has a downward sloping demand curve. Although raising prices causes the monopoly to lose some business, some sales can be made at higher prices. Although monopolists are constrained by consumer demand, they are not "price takers" because they can influence price through their production decisions. The monopolist can either have a ''target level of output'' that will ensure the monopoly price as the given consumer demand in the industry's market reacts to the fixed and limited market supply, or it can set a fixed monopoly price at the onset and adjust

Civil Action No. 98-1232, November 12, 2002. designed to prevent the predatory behavior. The company was successfully convicted of similar anti-competitive behavior in the

"Microsoft's Day in European Court"

April 24, 2006.

Jennifer L. Schenker, "BusinessWeek"

"Microsoft in Europe: The Real Stakes"

September 14, 2007.

Jennifer L. Schenker, "BusinessWeek"

"Endgame for Europe's Microsoft Case"

October 22, 2007. If firms in an industry collude they can also limit production to restrict supply, and ensure the price of the product remains high enough to ensure all of the firms in the industry achieve an economic profit. If a government feels it is impractical to have a competitive market, it sometimes tries to regulate the monopoly by controlling the price the monopoly charges for its product. The old AT&T monopoly, which existed before the courts ordered its breakup and tried to force competition in the market, had to get government approval to raise its prices. The government examined the monopoly's costs and determined if the monopoly should be allowed to raise its price; if the government felt that the cost did not justify a higher price, it rejected the monopoly's application. Although a regulated monopoly will not have a monopoly profit that is high as it would be in an unregulated situation, it still can have an economic profit that is still above what a competitive firm has in a truly competitive market.

Basic classical and neoclassical theory

Traditional economics state that in a competitive market, no firm can command elevated premiums for the price of goods and services as a result of sufficient competition. In contrast, insufficient competition can provide a producer with disproportionate pricing power. Withholding production to drive prices higher produces additional profit, which is called ''monopoly profits''.Roger LeRoy Miller, ''Intermediate Microeconomics: Theory Issues Applications'', Third Edition, New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc, 1982. According to classical and neoclassical economic thought, firms in a perfectly competitive market are price takers because no firm can charge a price that is different from theequilibrium price

In economics, economic equilibrium is a situation in which the economic forces of supply and demand are balanced, meaning that economic variables will no longer change.

Market equilibrium in this case is a condition where a market price is esta ...

set within the entire industry's perfectly competitive market.Tirole, Jean, ''The Theory of Industrial Organization'', Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1988. Since a competitive market has many competing firms, a customer can buy widgets from any of the competing firms.Edwin Mansfield, "Micro-Economics Theory and Applications, 3rd Edition", New York and London: W.W. Norton and Company, 1979.John Black, ''Oxford Dictionary of Economics'', New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. Because of this tight competition, competing firms in a market each have their own horizontal demand curve

A demand curve is a graph depicting the inverse demand function, a relationship between the price of a certain commodity (the ''y''-axis) and the quantity of that commodity that is demanded at that price (the ''x''-axis). Demand curves can be us ...

that is fixed at a single price established by market equilibrium for the entire industry as a whole. Each firm in a competitive market has buyers for its product as long as the firm charges "no more than" the single price. Since firms cannot control the activities of other firms that produce the same widget sold within the market, a firm that charges a price that is higher than the industry's market equilibrium price would lose business; customers would respond by buying their widgets from other competing firms that charge the lower market equilibrium price, which makes deviation from the market equilibrium price impossible.

Perfect competition is commonly characterized by an idealized situation in which all firms within the industry produce exact comparable goods that are perfect substitutes. With the exception of commodity markets

A commodity market is a market that trades in the primary economic sector rather than manufactured products. The primary sector includes agricultural products, energy products, and metals. Soft commodities may be perishable and harvested, w ...

, this idealized situation does not typically exist in many actual markets, but in many cases, there exist similar products that are easily interchangeable because they are close substitutes (for example, butter and margarine).Henderson, James M., and Richard E. Quandt, "Micro Economic Theory, A Mathematical Approach. 3rd Edition", New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1980. Glenview, Illinois: Scott, Foresmand and Company, 1988. A significant rise in a product's price tends to cause customers to switch from this good to a lower priced close substitute.Roger LeRoy Miller, "Intermediate Microeconomics Theory Issues Applications, Third Edition", New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc, 1982.

See Reference to "Price Elasticity" as it relates to "substitutability", as well as the "Marginal Rate of Technical Substitution" In some cases, firms that produce differing but similar goods have similar production processes, which makes it relatively easy for one-good firms to switch

In electrical engineering, a switch is an electrical component that can disconnect or connect the conducting path in an electrical circuit, interrupting the electric current or diverting it from one conductor to another. The most common type o ...

their manufacturing processes to produce a different but similar good. This would be the case when the cost of changing the firm's manufacturing process to produce the similar good can be somewhat immaterial in relationship to the firm's overall profit and cost. Since consumers tend to replace goods whose prices are high with cheaper close substitutes, and the existence of close substitutes whose manufacturing processes are similar allows a firm producing a low-priced good to easily switch over to producing the other higher priced good, the competition model accurately explains why the existence of different similar goods form competitive forces that deny any single firm the ability to establish a monopoly in their product. This effect is observable in a high profit and production cost industry, such as the car industry, and other industries facing competition from imports.Drake Bennett, "BusinessWeek""GM, Ford, and Chrysler: The Detroit Three Are Back, Right?"

April 4, 2013.

Drake Bennett, "BusinessWeek"

''The Debate Room'', April 4, 2013.

output

Output may refer to:

* The information produced by a computer, see Input/output

* An output state of a system, see state (computer science)

* Output (economics), the amount of goods and services produced

** Gross output in economics, the valu ...

until it can ensure no excess inventories

Inventory (British English) or stock (American English) is a quantity of the goods and materials that a business holds for the ultimate goal of resale, production or utilisation.

Inventory management is a discipline primarily about specifying ...

occur at the final output level chosen. At each price, the firm must accept the level of output as determined by the market's consumer demand, and every output quantity is identified with a price that is determined by the market's consumer demand. The price and output are co-determined by consumer demand and the firm's production cost structure.

A firm with monopoly power sets a monopoly price that maximizes the monopoly profit. The most profitable price for the monopoly occurs when output level ensures the marginal cost

In economics, the marginal cost is the change in the total cost that arises when the quantity produced is increased, i.e. the cost of producing additional quantity. In some contexts, it refers to an increment of one unit of output, and in others it ...

(MC) equals the marginal revenue (MR) associated with the demand curve. Under normal market conditions for a monopolist, this monopoly price is higher than the marginal (economic) cost of producing the product, indicating that the price paid by the consumer, which is equal to their marginal benefit

Marginal utility, in mainstream economics, describes the change in ''utility'' (pleasure or satisfaction resulting from the consumption) of one unit of a good or service. Marginal utility can be positive, negative, or zero. Negative marginal utilit ...

, is above the firm's MC.

Persistence

Withoutbarriers to entry

In theories of Competition (economics), competition in economics, a barrier to entry, or an economic barrier to entry, is a fixed cost that must be incurred by a new entrant, regardless of production or sales activities, into a Market (economics) ...

and collusion

Collusion is a deceitful agreement or secret cooperation between two or more parties to limit open competition by deceiving, misleading or defrauding others of their legal right. Collusion is not always considered illegal. It can be used to att ...

in a market, the existence of a monopoly and monopoly profit cannot persist in the long run

In economics, the long-run is a theoretical concept in which all markets are in equilibrium, and all prices and quantities have fully adjusted and are in equilibrium. The long-run contrasts with the short-run, in which there are some constraints a ...

. Normally, when economic profit exists within an industry

Industry may refer to:

Economics

* Industry (economics), a generally categorized branch of economic activity

* Industry (manufacturing), a specific branch of economic activity, typically in factories with machinery

* The wider industrial sector ...

, economic agents form new firms in the industry to obtain at least a portion of the existing economic profit. As new firms enter the industry, they increase the supply of the product available in the market, and they are forced to charge a lower price to entice consumers to buy the additional supply they are supplying as competition. Since consumers flock toward the lowest price (in search of a bargain), older firms within the industry may lose their existing customers to the new firms entering the industry, and are forced to lower their prices to match the prices set by the new firms. New firms continue to enter the industry until the price of the product is lowered to the point that it is the same as the average economic cost of producing the product, and economic profit disappears. When this happens, economic agents outside of the industry find no advantage to entering the industry, supply of the product stops increasing, and the price charged for the product stabilizes.

Normally, a firm that introduces a brand new product can initially secure a monopoly for a short while. At this stage, the initial price the consumer must pay for the product is high, and the demand for, as well as the availability of the product in the market, will be limited. As time passes, when the profitability of the product is well established, the number of firms that produce this product will increase until the available product supply becomes relatively large, and the product's price shrinks down to the level of the average economic cost of producing the product. When this occurs, all monopoly associated with producing and selling the product disappears, and the initial monopoly turns into a (perfectly) competitive industry.

When consumers have complete information about the prices available in the market and the quality of the products sold by the various firms, there cannot be a persistent monopolistic situation in the absence of barriers to entry and collusion.Steven M. Sheffrin, "Rational Expectations", New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987. John Black, "Oxford Dictionary of Economics", New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. Various barriers to entry include patent rights and the monopolization of a natural resource needed to produce a product. The American firm Alcoa Aluminum is a historical example of a monopoly due to natural resource control; its control of "practically every source of bauxite

Bauxite () is a sedimentary rock with a relatively high aluminium content. It is the world's main source of aluminium and gallium. Bauxite consists mostly of the aluminium minerals gibbsite (), boehmite (γ-AlO(OH)), and diaspore (α-AlO(OH) ...

in the United States" was one key reason that " twas, for a long time, the sole producer of aluminum in the United States".

A barrier to entry can exist in a market situation that is characterized by a combination of high fixed costs in production and a relatively small demand within the firm's product market. Since a high fixed cost results in a higher product market unit cost

The unit cost is the price incurred by a company

A company, abbreviated as co., is a Legal personality, legal entity representing an association of legal people, whether Natural person, natural, Juridical person, juridical or a mixture ...

s at lower production levels, and lower unit costs at higher production levels, the combination of a small product market demand for the firm's product, and the high revenue levels the firm needs to cover the high fixed costs it faces, indicate the product market will be dominated by a single large firm that uses economies of scale

In microeconomics, economies of scale are the cost advantages that enterprises obtain due to their scale of operation, and are typically measured by the amount of Productivity, output produced per unit of cost (production cost). A decrease in ...

to minimize both its unit cost and its product price.The combination of high fixed costs and a small product market Demand

In economics, demand is the quantity of a goods, good that consumers are willing and able to purchase at various prices during a given time. In economics "demand" for a commodity is not the same thing as "desire" for it. It refers to both the desi ...

ensures any reduction in a firm's Market share

Market share is the percentage of the total revenue or sales in a Market (economics), market that a company's business makes up. For example, if there are 50,000 units sold per year in a given industry, a company whose sales were 5,000 of those ...

will significantly raise its unit cost

The unit cost is the price incurred by a company

A company, abbreviated as co., is a Legal personality, legal entity representing an association of legal people, whether Natural person, natural, Juridical person, juridical or a mixture ...

s. If entry of additional firms into the industry indicates total industrial production

Industrial production is a measure of output of the industrial sector of the economy. The industrial sector includes manufacturing, mining, and utilities. Although these sectors contribute only a small portion of gross domestic product (GDP), they ...

increases, a decline in the price

A price is the (usually not negative) quantity of payment or compensation expected, required, or given by one party to another in return for goods or services. In some situations, especially when the product is a service rather than a ph ...

charged for the product would have to occur in order to accommodate the sale of the additional quantity that is produced for the product market. Even a small rise in the number of firms within the industry can quickly cause a large drop in profitability because of the double-whammy of rising unit cost

The unit cost is the price incurred by a company

A company, abbreviated as co., is a Legal personality, legal entity representing an association of legal people, whether Natural person, natural, Juridical person, juridical or a mixture ...

s and a falling price

A price is the (usually not negative) quantity of payment or compensation expected, required, or given by one party to another in return for goods or services. In some situations, especially when the product is a service rather than a ph ...

. This would tend to discourage the entry of new firms into the industry.

See: Bradley R. Chiller's "Essentials of Economics"(1991), pages 143–144,

Henderson and Quandt, Microeconomic Theory A Mathematical Approach, pages 193–195

New firms would be reticent to enter a product market if an apparent slim economic profit can turn into an immediate economic loss for all firms upon a new entry. However, since the qualities of most economic markets make them contestable markets, there may be a greater magnitude ofproduct differentiation

In economics and marketing, product differentiation (or simply differentiation) is the process of distinguishing a product or service from others to make it more attractive to a particular target market. This involves differentiating it from c ...

within this overall market structure, making it similar to monopolistic competition

Monopolistic competition is a type of imperfect competition such that there are many producers competing against each other but selling products that are differentiated from one another (e.g., branding, quality) and hence not perfect substi ...

.

Government intervention

Competition laws were created to prevent powerful firms from using their economic power to artificially create the barriers to entry they need to protect their monopoly profits, including the use ofpredatory pricing

Predatory pricing, also known as price slashing, is a commercial pricing strategy which involves reducing the retail prices to a level lower than competitors to eliminate competition. Selling at lower prices than a competitor is known as underc ...

toward smaller competitors. In the United States, Microsoft Corporation

Microsoft Corporation is an American multinational corporation and technology company, technology conglomerate headquartered in Redmond, Washington. Founded in 1975, the company became influential in the History of personal computers#The ear ...

was initially convicted of breaking competition laws and engaging in anti-competitive behavior to form a barrier in '' United States v. Microsoft Corporation''; after a successful appeal on technical grounds, Microsoft agreed to a settlement with the Department of Justice in which they were faced with stringent oversight procedures and explicit requirements"United States of America, Plaintiff, v. Microsoft Corporation, Defendant", Final JudgementCivil Action No. 98-1232, November 12, 2002. designed to prevent the predatory behavior. The company was successfully convicted of similar anti-competitive behavior in the

European Economic Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organisation created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisbo ...

's second highest court, the Court of First Instance

A trial court or court of first instance is a court having original jurisdiction, in which trials take place. Appeals from the decisions of trial courts are usually heard by higher courts with the power of appellate review (appellate courts). ...

, in 2007.Andy Reinhardt, "BusinessWeek""Microsoft's Day in European Court"

April 24, 2006.

Jennifer L. Schenker, "BusinessWeek"

"Microsoft in Europe: The Real Stakes"

September 14, 2007.

Jennifer L. Schenker, "BusinessWeek"

"Endgame for Europe's Microsoft Case"

October 22, 2007. If firms in an industry collude they can also limit production to restrict supply, and ensure the price of the product remains high enough to ensure all of the firms in the industry achieve an economic profit. If a government feels it is impractical to have a competitive market, it sometimes tries to regulate the monopoly by controlling the price the monopoly charges for its product. The old AT&T monopoly, which existed before the courts ordered its breakup and tried to force competition in the market, had to get government approval to raise its prices. The government examined the monopoly's costs and determined if the monopoly should be allowed to raise its price; if the government felt that the cost did not justify a higher price, it rejected the monopoly's application. Although a regulated monopoly will not have a monopoly profit that is high as it would be in an unregulated situation, it still can have an economic profit that is still above what a competitive firm has in a truly competitive market.

See also

*Profit margin

Profit margin is a financial ratio that measures the percentage of profit earned by a company in relation to its revenue. Expressed as a percentage, it indicates how much profit the company makes for every dollar of revenue generated. Profit margi ...

References

Further reading

*Kahana, Nava and Katz, Eliakim. "Monopoly, Price Discrimination, and Rent-Seeking". ''Journal Public Choice''. 64:1 (January 1990). *Langbein, Laura and Wilson, Len. "Grounded Beefs: monopoly prices, Minority Business, and the price of Hamburgers at U.S. Airports". ''Public Administration Review''. 1994. *von Mises, Ludwig. "Monopoly Prices". ''Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics

The ''Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics'' is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal covering heterodox economics published by the Ludwig von Mises Institute.Lee, Frederic S., and Cronin, Bruce C. (2010)"Research Quality Rankings of Heter ...

'' 1:2 (June 1998).

*Edwin Mansfield, "Micro-Economics Theory & Applications, 3rd Edition", New York and London:W.W. Norton and Company, 1979.

*Roger LeRoy Miller, "Intermediate Microeconomics Theory Issues Applications, Third Edition", New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc, 1982.

*Henderson, James M., and Richard E. Quandt, "Micro Economic Theory, A Mathematical Approach. 3rd Edition", New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1980. Glenview, Illinois: Scott, Foresmand and Company, 1988,

*Binger, Brian R., and Elizabeth Hoffman. "Micro Economics with Calculus", Glenview, Illinois: Scott, Foresmand and Company, 1988.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Monopoly Profit

Market failure

Monopoly (economics)

Profit

Renting