In the

history of Europe

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD 500), the Middle Ages (AD 500–1500), and the modern era (since AD 1500).

The first early Euro ...

, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the

post-classical

In Human history, world history, post-classical history refers to the period from about 500 CE to 1500 CE, roughly corresponding to the European Middle Ages. The period is characterized by the expansion of civilizations geographically an ...

period of

global history. It began with the

fall of the Western Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire, also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome, was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vast ...

and transitioned into the

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

and the

Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery (), also known as the Age of Exploration, was part of the early modern period and overlapped with the Age of Sail. It was a period from approximately the 15th to the 17th century, during which Seamanship, seafarers fro ...

. The Middle Ages is the middle period of the three traditional divisions of Western history:

classical antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

, the medieval period, and the

modern period

The modern era or the modern period is considered the current historical period of human history. It was originally applied to the history of Europe and Western history for events that came after the Middle Ages, often from around the year 1500 ...

. The medieval period is itself subdivided into the

Early,

High, and

Late Middle Ages

The late Middle Ages or late medieval period was the Periodization, period of History of Europe, European history lasting from 1300 to 1500 AD. The late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period ( ...

.

Population decline

Population decline, also known as depopulation, is a reduction in a human population size. Throughout history, Earth's total world population, human population has estimates of historical world population, continued to grow but projections sugg ...

,

counterurbanisation

Counterurbanization, Ruralization or deurbanization is a demographic and social process in which people move from urban areas to rural areas. It, as suburbanization, is inversely related to urbanization, and first occurs as a reaction to inner-c ...

, the collapse of centralised authority, invasions, and mass migrations of

tribe

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide use of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. The definition is contested, in part due to conflict ...

s, which had begun in

late antiquity

Late antiquity marks the period that comes after the end of classical antiquity and stretches into the onset of the Early Middle Ages. Late antiquity as a period was popularized by Peter Brown (historian), Peter Brown in 1971, and this periodiza ...

, continued into the Early Middle Ages. The large-scale movements of the

Migration Period

The Migration Period ( 300 to 600 AD), also known as the Barbarian Invasions, was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories ...

, including various

Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were tribal groups who lived in Northern Europe in Classical antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. In modern scholarship, they typically include not only the Roman-era ''Germani'' who lived in both ''Germania'' and parts of ...

, formed new kingdoms in what remained of the Western Roman Empire. In the 7th century,

North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

and the Middle East—once part of the

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

—came under the rule of the

Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate or Umayyad Empire (, ; ) was the second caliphate established after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and was ruled by the Umayyad dynasty. Uthman ibn Affan, the third of the Rashidun caliphs, was also a member o ...

, an Islamic empire, after conquest by

Muhammad's successors. Although there were substantial changes in society and political structures, the break with

classical antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

was incomplete. The still-sizeable Byzantine Empire, Rome's direct continuation, survived in the Eastern Mediterranean and remained a major power. The empire's law code, the ''

Corpus Juris Civilis

The ''Corpus Juris'' (or ''Iuris'') ''Civilis'' ("Body of Civil Law") is the modern name for a collection of fundamental works in jurisprudence, enacted from 529 to 534 by order of Byzantine Emperor Justinian I. It is also sometimes referred ...

'' or "Code of Justinian", was rediscovered in

Northern Italy

Northern Italy (, , ) is a geographical and cultural region in the northern part of Italy. The Italian National Institute of Statistics defines the region as encompassing the four Northwest Italy, northwestern Regions of Italy, regions of Piedmo ...

in the 11th century. In the West, most kingdoms incorporated the few extant Roman institutions. Monasteries were founded as campaigns to

Christianise the

remaining pagans across Europe continued. The

Franks

file:Frankish arms.JPG, Aristocratic Frankish burial items from the Merovingian dynasty

The Franks ( or ; ; ) were originally a group of Germanic peoples who lived near the Rhine river, Rhine-river military border of Germania Inferior, which wa ...

, under the

Carolingian dynasty

The Carolingian dynasty ( ; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Franks, Frankish noble family named after Charles Martel and his grandson Charlemagne, descendants of the Pippinids, Arnulfi ...

, briefly established the

Carolingian Empire

The Carolingian Empire (800–887) was a Franks, Frankish-dominated empire in Western and Central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as List of Frankish kings, kings of the Franks since ...

during the later 8th and early 9th centuries. It covered much of Western Europe but later succumbed to the pressures of internal civil wars combined with external invasions:

Vikings

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

from the north,

Magyars

Hungarians, also known as Magyars, are an ethnic group native to Hungary (), who share a common culture, language and history. They also have a notable presence in former parts of the Kingdom of Hungary. The Hungarian language belongs to the ...

from the east, and

Saracen

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

''Saracen'' ( ) was a term used both in Greek and Latin writings between the 5th and 15th centuries to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Rom ...

s from the south.

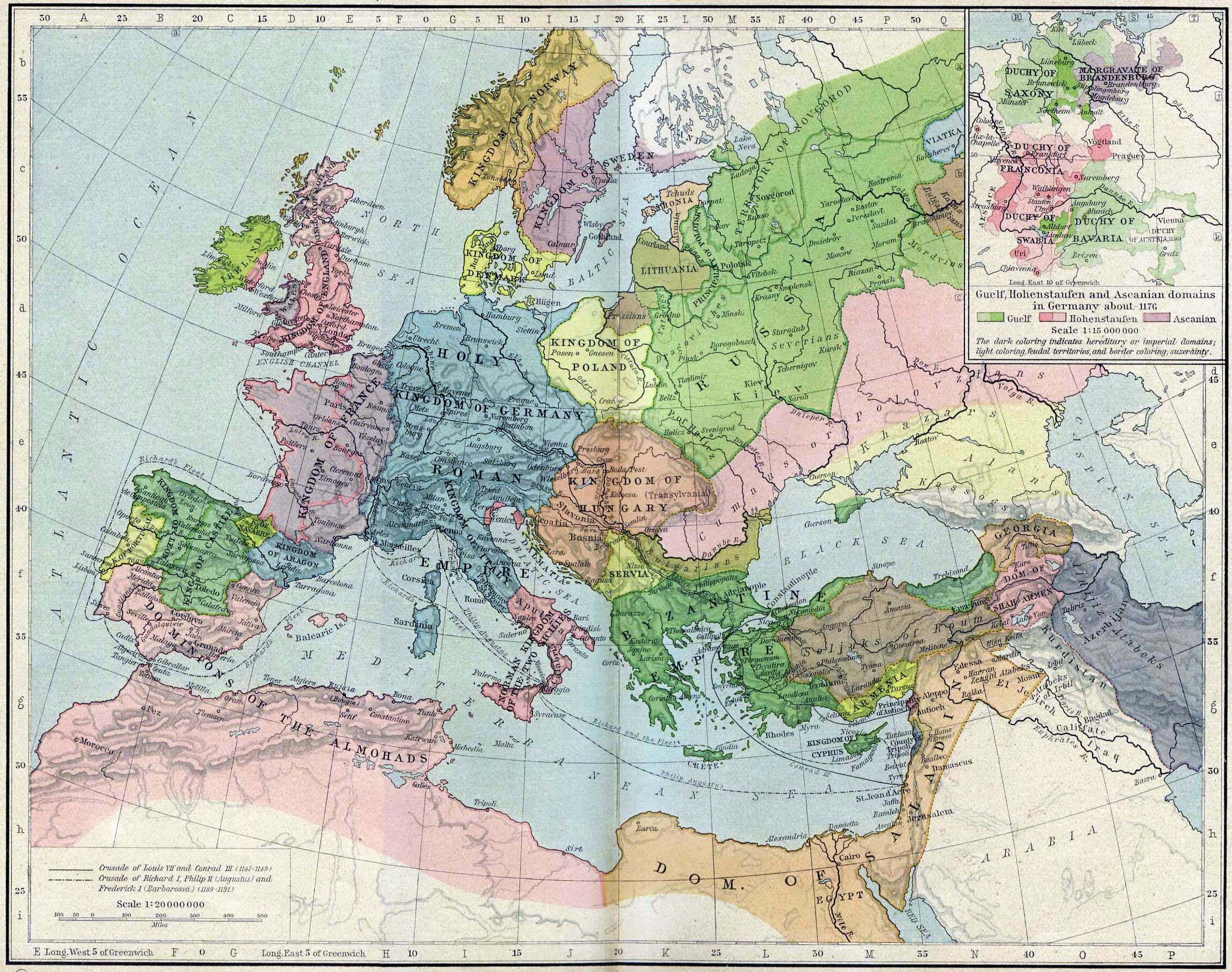

During the High Middle Ages, which began after 1000, the population of Europe increased significantly as technological and

agricultural innovations allowed trade to flourish and the

Medieval Warm Period

The Medieval Warm Period (MWP), also known as the Medieval Climate Optimum or the Medieval Climatic Anomaly, was a time of warm climate in the North Atlantic region that lasted from about to about . Climate proxy records show peak warmth occu ...

climate change allowed crop yields to increase.

Manorialism

Manorialism, also known as seigneurialism, the manor system or manorial system, was the method of land ownership (or "Land tenure, tenure") in parts of Europe, notably France and later England, during the Middle Ages. Its defining features incl ...

, the organisation of

peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasan ...

s into villages that owed rent and labour services to the

nobles

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally appointed by and ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. T ...

, and

feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of struc ...

, the political structure whereby

knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

s and lower-status nobles owed military service to their

overlord

An overlord in the English feudal system was a lord of a manor who had subinfeudated a particular manor, estate or fee, to a tenant. The tenant thenceforth owed to the overlord one of a variety of services, usually military service or ...

s in return for the right to rent from lands and

manors, were two of the ways society was organised in the High Middle Ages. This period also saw the collapse of the unified Christian church with the

East–West Schism

The East–West Schism, also known as the Great Schism or the Schism of 1054, is the break of communion (Christian), communion between the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church. A series of Eastern Orthodox – Roman Catholic eccle ...

of 1054. The

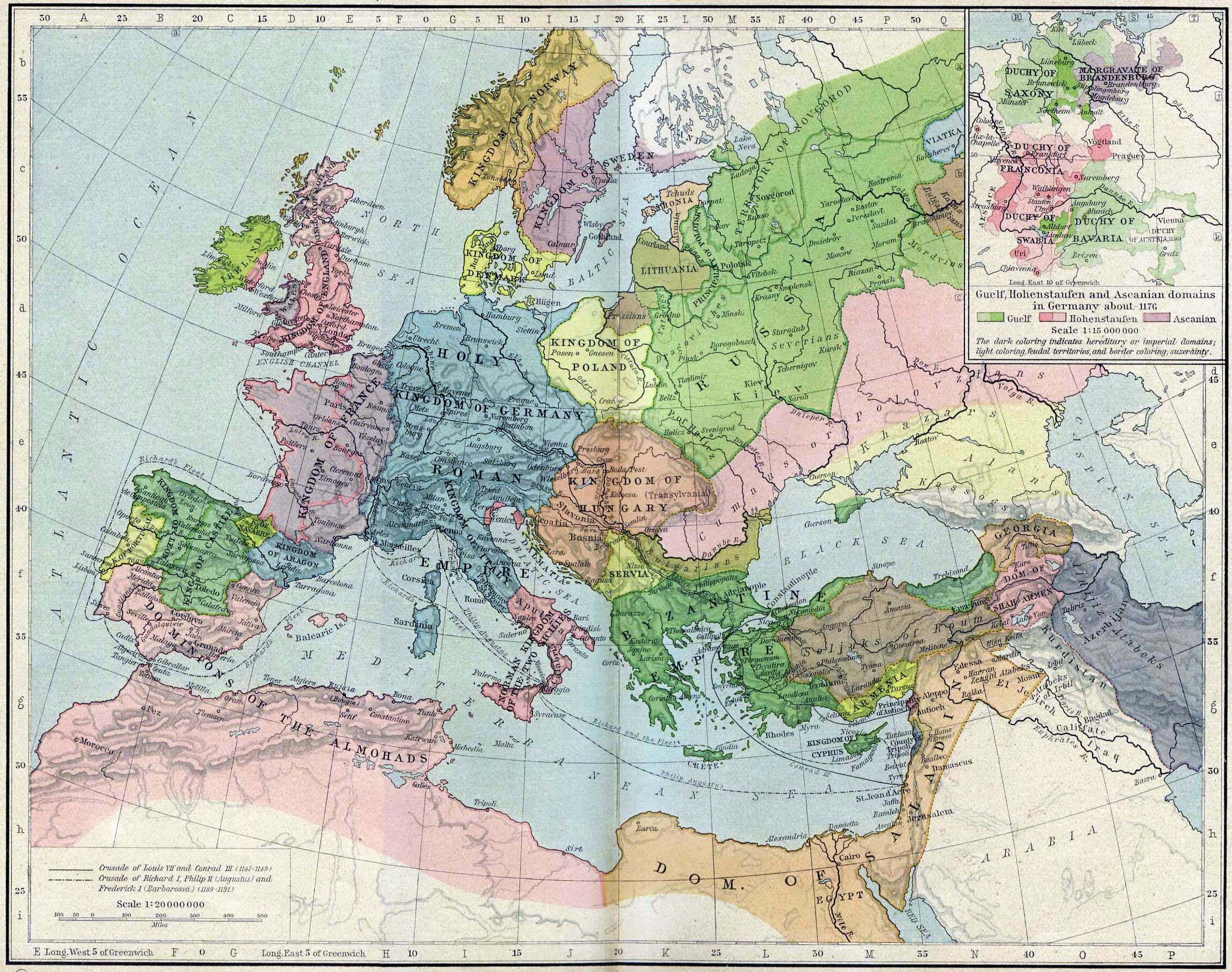

Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

, first preached in 1095, were military attempts by Western European Christians to regain control of the

Holy Land

The term "Holy Land" is used to collectively denote areas of the Southern Levant that hold great significance in the Abrahamic religions, primarily because of their association with people and events featured in the Bible. It is traditionall ...

from

Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

s. Kings became the heads of centralised

nation-states, reducing crime and violence but making the ideal of a unified

Christendom more distant. Intellectual life was marked by

scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval European philosophical movement or methodology that was the predominant education in Europe from about 1100 to 1700. It is known for employing logically precise analyses and reconciling classical philosophy and Ca ...

, a philosophy that emphasised joining faith to reason, and by the founding of

universities

A university () is an educational institution, institution of tertiary education and research which awards academic degrees in several Discipline (academia), academic disciplines. ''University'' is derived from the Latin phrase , which roughly ...

. The theology of

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

, the paintings of

Giotto

Giotto di Bondone (; – January 8, 1337), known mononymously as Giotto, was an List of Italian painters, Italian painter and architect from Florence during the Late Middle Ages. He worked during the International Gothic, Gothic and Italian Ren ...

, the poetry of

Dante

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

and

Chaucer, the travels of

Marco Polo

Marco Polo (; ; ; 8 January 1324) was a Republic of Venice, Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in ''The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known a ...

, and the

Gothic architecture

Gothic architecture is an architectural style that was prevalent in Europe from the late 12th to the 16th century, during the High Middle Ages, High and Late Middle Ages, surviving into the 17th and 18th centuries in some areas. It evolved f ...

of cathedrals such as

Chartres

Chartres () is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Eure-et-Loir Departments of France, department in the Centre-Val de Loire Regions of France, region in France. It is located about southwest of Paris. At the 2019 census, there were 1 ...

are among the outstanding achievements toward the end of this period and into the Late Middle Ages.

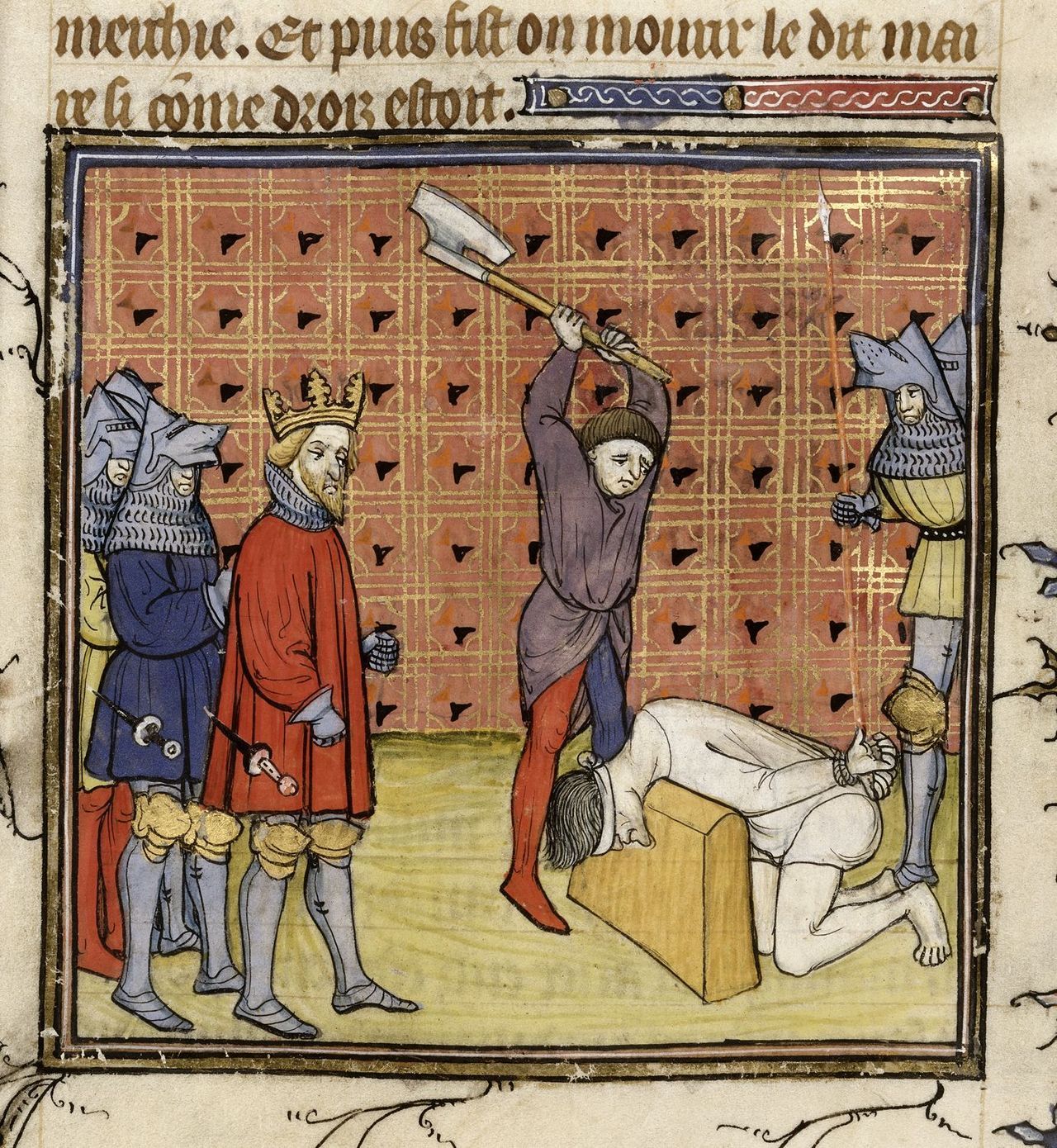

The Late Middle Ages was marked by difficulties and calamities, including famine, plague, and war, which significantly diminished the population of Europe; between 1347 and 1350, the

Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

killed about a third of Europeans. Controversy,

heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Heresy in Christian ...

, and the

Western Schism within the

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

paralleled the interstate conflict, civil strife, and

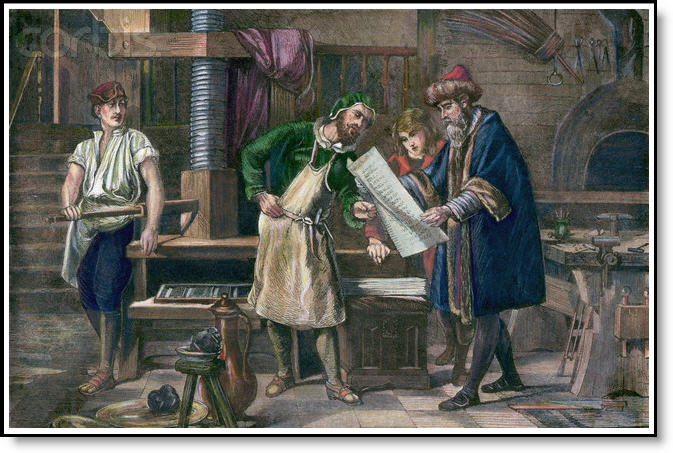

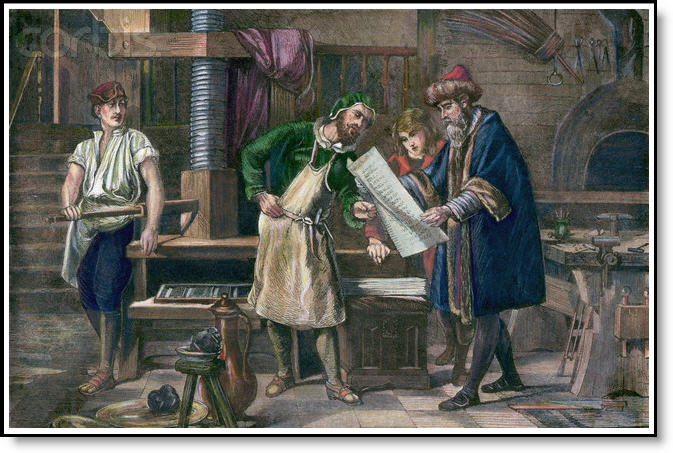

peasant revolts that occurred in the kingdoms. Cultural and technological developments transformed European society, concluding the Late Middle Ages and beginning the

early modern period

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

.

Terminology and periodisation

The Middle Ages is one of the three major periods in the most enduring scheme for analysing

European history:

classical civilisation or

antiquity, the Middle Ages and the

modern period

The modern era or the modern period is considered the current historical period of human history. It was originally applied to the history of Europe and Western history for events that came after the Middle Ages, often from around the year 1500 ...

.

[Power ''Central Middle Ages'' p. 3] The "Middle Ages" first appears in Latin in 1469 as ''media tempestas'' or "middle season".

[Miglio "Curial Humanism" ''Interpretations of Renaissance Humanism'' p. 112] In early usage, there were many variants, including ''medium aevum'', or "middle age", first recorded in 1604,

[Albrow ''Global Age'' p. 205] and ''media saecula'', or "middle centuries", first recorded in 1625.

The adjective "medieval" (or sometimes "mediaeval"

or "mediæval"),

["Mediaeval" ''Compact Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary''] meaning pertaining to the Middle Ages, derives from .

[Flexner (ed.) ''Random House Dictionary'' p. 1194]

Medieval writers divided history into periods such as the "

Six Ages" or the "

Four Empires" and considered their time to be the last before the end of the world.

[Mommsen "Petrarch's Conception of the 'Dark Ages'" ''Speculum'' pp. 236–237] When referring to their own times, they spoke of them as being "modern".

[Singman ''Daily Life'' p. x] In the 1330s, the Italian humanist and poet

Petrarch

Francis Petrarch (; 20 July 1304 – 19 July 1374; ; modern ), born Francesco di Petracco, was a scholar from Arezzo and poet of the early Italian Renaissance, as well as one of the earliest Renaissance humanism, humanists.

Petrarch's redis ...

referred to pre-Christian times as ('ancient') and to the Christian period as ('new').

[Knox]

History of the Idea of the Renaissance

Petrarch regarded the post-Roman centuries as "

dark" compared to the "light" of

classical antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

.

[Mommsen "Petrarch's Conception of the 'Dark Ages'" ''Speculum'' pp. 227–228] Leonardo Bruni was the first historian to use

tripartite periodisation in his ''History of the Florentine People'' (1442), with a middle period "between the fall of the Roman Empire and the revival of city life sometime in late eleventh and twelfth centuries".

[Bruni ''History of the Florentine people'' pp. xvii–xviii] Tripartite

periodisation became standard after the 17th-century German historian

Christoph Cellarius divided history into three periods: ancient, medieval, and modern.

[Murray "Should the Middle Ages Be Abolished?" ''Essays in Medieval Studies'' p. 4]

The most commonly given starting point for the Middle Ages is around 500, with the date of 476 first used by Bruni.

Later starting dates are sometimes used in the outer parts of Europe. For Europe as a whole, 1500 is often considered to be the end of the Middle Ages, but there is no universally agreed upon end date. Depending on the context, events such as the

conquest of Constantinople by the Turks in 1453,

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed Voyages of Christopher Columbus, four Spanish-based voyages across the At ...

's first voyage to the

Americas

The Americas, sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America and South America.''Webster's New World College Dictionary'', 2010 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio. When viewed as a sing ...

in 1492, or the

Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

in 1517 are sometimes used.

English historians often use the

Battle of Bosworth Field

The Battle of Bosworth or Bosworth Field ( ) was the last significant battle of the Wars of the Roses, the civil war between the houses of House of Lancaster, Lancaster and House of York, York that extended across England in the latter half ...

in 1485 to mark the end of the period. For Spain, dates commonly used are the death of King

Ferdinand II in 1516, the death of Queen

Isabella I of Castile in 1504, or the

conquest of Granada in 1492.

Historians from

Romance-speaking

The Romance languages, also known as the Latin or Neo-Latin languages, are the languages that are directly descended from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic branch of the Indo-European language family.

The fi ...

countries tend to divide the Middle Ages into two parts: an earlier "High" and later "Low" period. English-speaking historians, following their German counterparts, generally subdivide the Middle Ages into three intervals: "Early", "High", and "Late".

In the 19th century, the entire Middle Ages were often referred to as the "

Dark Ages",

[Mommsen "Petrarch's Conception of the 'Dark Ages'" ''Speculum'' p. 226] but with the adoption of these subdivisions, use of this term was restricted to the Early Middle Ages, at least among historians.

Later Roman Empire

The

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

reached its greatest territorial extent during the 2nd century AD; the following two centuries witnessed the slow decline of Roman control over its outlying territories.

[Cunliffe ''Europe Between the Oceans'' pp. 391–393] Economic issues, including inflation, and external pressure on the frontiers combined to create the

Crisis of the Third Century

The Crisis of the Third Century, also known as the Military Anarchy or the Imperial Crisis, was a period in History of Rome, Roman history during which the Roman Empire nearly collapsed under the combined pressure of repeated Barbarian invasions ...

, with emperors coming to the throne only to be rapidly replaced by new usurpers.

[Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 3–5] Military expenses increased steadily during the 3rd century, mainly in response to the

war with the

Sasanian Empire

The Sasanian Empire (), officially Eranshahr ( , "Empire of the Iranian peoples, Iranians"), was an List of monarchs of Iran, Iranian empire that was founded and ruled by the House of Sasan from 224 to 651. Enduring for over four centuries, th ...

, which revived in the middle of the 3rd century.

The army doubled in size, and cavalry and smaller units replaced the

Roman legion

The Roman legion (, ) was the largest military List of military legions, unit of the Roman army, composed of Roman citizenship, Roman citizens serving as legionary, legionaries. During the Roman Republic the manipular legion comprised 4,200 i ...

as the main tactical unit.

[Brown ''World of Late Antiquity'' pp. 24–25] The need for revenue led to increased taxes and a decline in numbers of the

curial, or landowning, class, and decreasing numbers of them willing to shoulder the burdens of holding office in their native towns.

[Heather ''Fall of the Roman Empire'' p. 111] More bureaucrats were needed in the central administration to deal with the needs of the army, which led to complaints from civilians that there were more tax-collectors in the empire than tax-payers.

The Emperor

Diocletian

Diocletian ( ; ; ; 242/245 – 311/312), nicknamed Jovius, was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Diocles to a family of low status in the Roman province of Dalmatia (Roman province), Dalmatia. As with other Illyri ...

(r. 284–305) split the empire into separately administered

eastern and

western halves in 286; the empire was not considered divided by its inhabitants or rulers, as legal and administrative

promulgation

Promulgation is the formal proclamation or the declaration that a new statute, statutory or administrative law is enacted after its final Enactment of a bill, approval. In some jurisdiction (area), jurisdictions, this additional step is necessary ...

s in one division were considered valid in the other.

[Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' p. 9] In 330, after a period of civil war,

Constantine the Great

Constantine I (27 February 27222 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was a Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337 and the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity. He played a Constantine the Great and Christianity, pivotal ro ...

(r. 306–337) refounded the city of

Byzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion () was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium'' continued to be used as a n ...

as the newly renamed eastern capital,

Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

.

[Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' p. 24] Diocletian's reforms strengthened the governmental bureaucracy, reformed taxation, and strengthened the army, which bought the empire time but did not resolve the problems it was facing: excessive taxation, a declining birthrate, and pressures on its frontiers, among others.

[Cunliffe ''Europe Between the Oceans'' pp. 405–406] Civil war between rival emperors became common in the middle of the 4th century, diverting soldiers from the empire's frontier forces and allowing

invaders to encroach.

[Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 31–33] For much of the 4th century, Roman society stabilised in a new form that differed from the earlier

classical period, with a widening gulf between the rich and poor, and a decline in the vitality of the smaller towns.

[Brown ''World of Late Antiquity'' p. 34] Another change was the

Christianisation, or conversion of the empire to

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

, a gradual process that lasted from the 2nd to the 5th centuries.

[Brown ''World of Late Antiquity'' pp. 65–68][Brown ''World of Late Antiquity'' pp. 82–94]

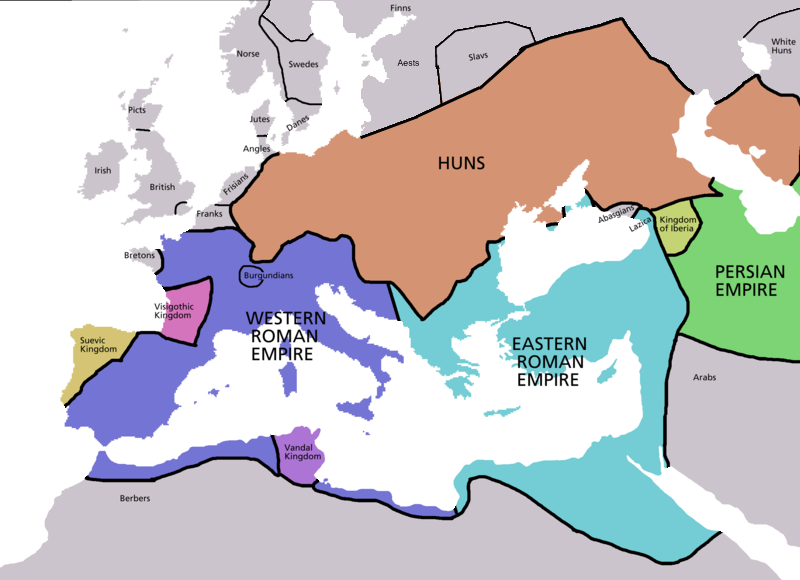

In 376, the

Goths

The Goths were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe. They were first reported by Graeco-Roman authors in the 3rd century AD, living north of the Danube in what is ...

, fleeing from the

Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th centuries AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was par ...

, received permission from Emperor

Valens

Valens (; ; 328 – 9 August 378) was Roman emperor from 364 to 378. Following a largely unremarkable military career, he was named co-emperor by his elder brother Valentinian I, who gave him the Byzantine Empire, eastern half of the Roman Em ...

(r. 364–378) to settle in the Roman province of

Thracia

Thracia or Thrace () is the ancient name given to the southeastern Balkans, Balkan region, the land inhabited by the Thracians. Thrace was ruled by the Odrysian kingdom during the Classical Greece, Classical and Hellenistic period, Hellenis ...

in the

Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

. The settlement did not go smoothly, and the Goths began to raid and plunder when Roman officials mishandled the situation. Valens, attempting to put down the disorder, was killed fighting the Goths at the

Battle of Adrianople on 9 August 378.

[Bauer ''History of the Medieval World'' pp. 47–49] In addition to the threat from such tribal confederacies in the north, internal divisions within the empire, especially within the Christian Church, caused problems.

[Bauer ''History of the Medieval World'' pp. 56–59] In 400, the

Visigoths

The Visigoths (; ) were a Germanic people united under the rule of a king and living within the Roman Empire during late antiquity. The Visigoths first appeared in the Balkans, as a Roman-allied Barbarian kingdoms, barbarian military group unite ...

invaded the Western Roman Empire and, although briefly forced back from Italy, in 410

sacked the city of Rome.

[Bauer ''History of the Medieval World'' pp. 80–83] In 406 the

Alans

The Alans () were an ancient and medieval Iranian peoples, Iranic Eurasian nomads, nomadic pastoral people who migrated to what is today North Caucasus – while some continued on to Europe and later North Africa. They are generally regarded ...

,

Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic people who were first reported in the written records as inhabitants of what is now Poland, during the period of the Roman Empire. Much later, in the fifth century, a group of Vandals led by kings established Vand ...

, and

Suevi

file:1st century Germani.png, 300px, The approximate positions of some Germanic peoples reported by Graeco-Roman authors in the 1st century. Suebian peoples in red, and other Irminones in purple.

The Suebi (also spelled Suavi, Suevi or Suebians ...

crossed into

Gaul

Gaul () was a region of Western Europe first clearly described by the Roman people, Romans, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, and Northern Italy. It covered an area of . Ac ...

; over the next three years they spread across Gaul and in 409 crossed the

Pyrenees Mountains into modern-day Spain.

[Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 59–60] The

Migration Period

The Migration Period ( 300 to 600 AD), also known as the Barbarian Invasions, was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories ...

began, when various peoples, initially largely

Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were tribal groups who lived in Northern Europe in Classical antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. In modern scholarship, they typically include not only the Roman-era ''Germani'' who lived in both ''Germania'' and parts of ...

, moved across Europe. The

Franks

file:Frankish arms.JPG, Aristocratic Frankish burial items from the Merovingian dynasty

The Franks ( or ; ; ) were originally a group of Germanic peoples who lived near the Rhine river, Rhine-river military border of Germania Inferior, which wa ...

,

Alemanni

The Alemanni or Alamanni were a confederation of Germanic peoples, Germanic tribes

*

*

*

on the Upper Rhine River during the first millennium. First mentioned by Cassius Dio in the context of the campaign of Roman emperor Caracalla of 213 CE ...

, and the

Burgundians

The Burgundians were an early Germanic peoples, Germanic tribe or group of tribes. They appeared east in the middle Rhine region in the third century AD, and were later moved west into the Roman Empire, in Roman Gaul, Gaul. In the first and seco ...

all ended up in northern Gaul while the

Angles,

Saxons

The Saxons, sometimes called the Old Saxons or Continental Saxons, were a Germanic people of early medieval "Old" Saxony () which became a Carolingian " stem duchy" in 804, in what is now northern Germany. Many of their neighbours were, like th ...

, and

Jutes

The Jutes ( ) were one of the Germanic people, Germanic tribes who settled in Great Britain after the end of Roman rule in Britain, departure of the Roman Britain, Romans. According to Bede, they were one of the three most powerful Germanic na ...

settled in Britain,

and the Vandals went on to cross the strait of Gibraltar after which they conquered the province of

Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

.

[Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' p. 80] In the 430s the Huns began invading the empire; their king

Attila

Attila ( or ; ), frequently called Attila the Hun, was the ruler of the Huns from 434 until his death in early 453. He was also the leader of an empire consisting of Huns, Ostrogoths, Alans, and Gepids, among others, in Central Europe, C ...

(r. 434–453) led invasions into the Balkans in 442 and 447, Gaul in 451, and Italy in 452.

[James ''Europe's Barbarians'' pp. 67–68] The Hunnic threat remained until Attila's death in 453, when the

Hunnic confederation he led fell apart.

[Bauer ''History of the Medieval World'' pp. 117–118] These invasions by the tribes completely changed the political and demographic nature of what had been the Western Roman Empire.

[Cunliffe ''Europe Between the Oceans'' p. 417]

By the end of the 5th century, the western section of the empire was divided into smaller political units ruled by the tribes that had invaded in the early part of the century.

[Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' p. 79] The deposition of the last emperor of the west,

Romulus Augustulus

Romulus Augustus (after 511), nicknamed Augustulus, was Roman emperor of the Western Roman Empire, West from 31 October 475 until 4 September 476. Romulus was placed on the imperial throne while still a minor by his father Orestes (father of Ro ...

, in 476 has traditionally marked the end of the Western Roman Empire.

[Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' p. 86] By 493 the Italian peninsula was conquered by the

Ostrogoths

The Ostrogoths () were a Roman-era Germanic peoples, Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Goths, Gothic kingdoms within the Western Roman Empire, drawing upon the large Gothic populatio ...

.

[Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 107–109] The Eastern Roman Empire, often referred to as the Byzantine Empire after the fall of its western counterpart, had little ability to assert control over the lost western territories. The

Byzantine emperors maintained a claim over the territory, but while none of the new kings in the west dared to elevate himself to the position of emperor of the west, Byzantine control of most of the Western Empire could not be sustained; the reconquest of the Mediterranean periphery and the

Italian Peninsula (

Gothic War) in the reign of

Justinian

Justinian I (, ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was Roman emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign was marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovatio imperii'', or "restoration of the Empire". This ambition was ...

(r. 527–565) was the sole, and temporary, exception.

[Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 116–134]

Early Middle Ages

New societies

The political structure of Western Europe changed with the end of the united Roman Empire. Although the movements of peoples during this period are usually described as "invasions", they were not just military expeditions but migrations of entire peoples into the empire. Such movements were aided by the refusal of the Western Roman elites to support the army or pay the taxes that would have allowed the military to suppress the migration.

[Brown, ''World of Late Antiquity'', pp. 122–124] The emperors of the 5th century were often controlled by military strongmen such as

Stilicho (d. 408),

Aetius (d. 454),

Aspar (d. 471),

Ricimer (d. 472), or

Gundobad

Gundobad (; ; 452 – 516) was King of the Burgundians (473–516), succeeding his father Gundioc of Burgundy. Previous to this, he had been a patrician of the moribund Western Roman Empire in 472–473, three years before its collapse, suc ...

(d. 516), who were partly or fully of non-Roman background. When the line of Western emperors ceased, many of the kings who replaced them were from the same background. Intermarriage between the new kings and the Roman elites was common.

[Wickham, ''Inheritance of Rome'', pp. 95–98] This led to a fusion of Roman culture with the customs of the invading tribes, including the popular assemblies that allowed free male tribal members more say in political matters than was common in the Roman state.

[Wickham, ''Inheritance of Rome'', pp. 100–101] Material artefacts left by the Romans and the invaders are often similar, and tribal items were often modelled on Roman objects.

[Collins, ''Early Medieval Europe'', p. 100] Much of the scholarly and written culture of the new kingdoms was also based on Roman intellectual traditions.

[Collins, ''Early Medieval Europe'', pp. 96–97] An important difference was the new polities' gradual loss of tax revenue. Many new political entities no longer supported their armies through taxes; instead, they relied on granting them land or rents. This meant there was less need for large tax revenues, so the

taxation systems decayed.

[Wickham, ''Inheritance of Rome'', pp. 102–103] Warfare was common between and within the kingdoms. Slavery declined as the supply weakened, and society became more rural.

[Backman, ''Worlds of Medieval Europe'', pp. 86–91]

Between the 5th and 8th centuries, new peoples and individuals filled the political void left by the centralised Roman government.

The

Ostrogoths

The Ostrogoths () were a Roman-era Germanic peoples, Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Goths, Gothic kingdoms within the Western Roman Empire, drawing upon the large Gothic populatio ...

, a Gothic tribe, settled in

Roman Italy

Roman Italy is the period of ancient Italian history going from the founding of Rome, founding and Roman expansion in Italy, rise of ancient Rome, Rome to the decline and fall of the Western Roman Empire; the Latin name of the Italian peninsula ...

in the late fifth century under

Theoderic the Great (d. 526) and set up a

kingdom marked by its co-operation between the Italians and the Ostrogoths, at least until the last years of Theodoric's reign.

[James ''Europe's Barbarians'' pp. 82–88] The Burgundians settled in Gaul, and after an earlier realm was destroyed by the Huns in 436, formed a new kingdom in the 440s. Between today's

Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

and

Lyon

Lyon (Franco-Provençal: ''Liyon'') is a city in France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of the French Alps, southeast of Paris, north of Marseille, southwest of Geneva, Switzerland, north ...

, it grew to become the realm of

Burgundy

Burgundy ( ; ; Burgundian: ''Bregogne'') is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. ...

in the late 5th and early 6th centuries.

[James ''Europe's Barbarians'' pp. 77–78] Elsewhere in Gaul, the Franks and

Celtic Britons set up small polities.

Francia

The Kingdom of the Franks (), also known as the Frankish Kingdom, or just Francia, was the largest History of the Roman Empire, post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Franks, Frankish Merovingian dynasty, Merovingi ...

was centred in northern Gaul, and the first king of whom much is known is

Childeric I (d. 481). His grave was discovered in 1653 and is remarkable for its

grave goods, which included weapons and a large quantity of gold.

[James ''Europe's Barbarians'' pp. 79–80]

Under Childeric's son

Clovis I

Clovis (; reconstructed Old Frankish, Frankish: ; – 27 November 511) was the first List of Frankish kings, king of the Franks to unite all of the Franks under one ruler, changing the form of leadership from a group of petty kings to rule by a ...

(r. 509–511), the founder of the

Merovingian dynasty

The Merovingian dynasty () was the ruling family of the Franks from around the middle of the 5th century until Pepin the Short in 751. They first appear as "Kings of the Franks" in the Roman army of northern Gaul. By 509 they had united all the ...

, the Frankish kingdom expanded and converted to Christianity. The Britons, related to the natives of

Britannia

The image of Britannia () is the national personification of United Kingdom, Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used by the Romans in classical antiquity, the Latin was the name variously appli ...

– modern-day Great Britain – settled in what is now

Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

.

[James ''Europe's Barbarians'' pp. 78–81] Other monarchies were established by the

Visigothic Kingdom

The Visigothic Kingdom, Visigothic Spain or Kingdom of the Goths () was a Barbarian kingdoms, barbarian kingdom that occupied what is now southwestern France and the Iberian Peninsula from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the Germanic people ...

in the

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

, the

Suebi

file:1st century Germani.png, 300px, The approximate positions of some Germanic peoples reported by Graeco-Roman authors in the 1st century. Suebian peoples in red, and other Irminones in purple.

The Suebi (also spelled Suavi, Suevi or Suebians ...

in northwestern Iberia, and the

Vandal Kingdom

The Vandal Kingdom () or Kingdom of the Vandals and Alans () was a confederation of Vandals and Alans, which was a barbarian kingdoms, barbarian kingdom established under Gaiseric, a Vandals, Vandalic warlord. It ruled parts of North Africa and th ...

in

North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

.

In the sixth century, the

Lombards

The Lombards () or Longobards () were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who conquered most of the Italian Peninsula between 568 and 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written betwee ...

settled in

Northern Italy

Northern Italy (, , ) is a geographical and cultural region in the northern part of Italy. The Italian National Institute of Statistics defines the region as encompassing the four Northwest Italy, northwestern Regions of Italy, regions of Piedmo ...

, replacing the Ostrogothic kingdom with a grouping of

duchies that occasionally selected a king to rule over them all. By the late sixth century, this arrangement had been replaced by a permanent monarchy, the

Kingdom of the Lombards

The Kingdom of the Lombards, also known as the Lombard Kingdom and later as the Kingdom of all Italy (), was an Early Middle Ages, early medieval state established by the Lombards, a Germanic people, on the Italian Peninsula in the latter part ...

.

[Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 196–208]

The invasions brought new ethnic groups to Europe, although some regions received a larger influx of new peoples than others. In Gaul, for instance, the invaders settled much more extensively in the north-east than in the south-west.

Slavs

The Slavs or Slavic people are groups of people who speak Slavic languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout the northern parts of Eurasia; they predominantly inhabit Central Europe, Eastern Europe, Southeastern Europe, and ...

settled in

Central and

Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

and the Balkan Peninsula. Changes in languages accompanied the settlement of peoples.

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, the literary language of the Western Roman Empire, was gradually replaced by

vernacular languages, which evolved from Latin but were distinct from it, collectively known as

Romance languages

The Romance languages, also known as the Latin or Neo-Latin languages, are the languages that are Language family, directly descended from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-E ...

. These changes from Latin to the new languages took many centuries. Greek remained the language of the Byzantine Empire, but the migrations of the Slavs added

Slavic languages

The Slavic languages, also known as the Slavonic languages, are Indo-European languages spoken primarily by the Slavs, Slavic peoples and their descendants. They are thought to descend from a proto-language called Proto-Slavic language, Proto- ...

to Eastern Europe.

[Davies ''Europe'' pp. 235–238]

Byzantine survival

As Western Europe witnessed the formation of new kingdoms, the Eastern Roman Empire remained intact and experienced an economic revival that lasted into the early 7th century. There were fewer invasions of the eastern section of the empire; most occurred in the Balkans. Peace with the

Sasanian Empire

The Sasanian Empire (), officially Eranshahr ( , "Empire of the Iranian peoples, Iranians"), was an List of monarchs of Iran, Iranian empire that was founded and ruled by the House of Sasan from 224 to 651. Enduring for over four centuries, th ...

, Rome's traditional enemy, lasted most of the 5th century. The Eastern Empire was marked by closer relations between the political state and the Christian Church, with doctrinal matters assuming an importance in Eastern politics that they did not have in Western Europe. Legal developments included the codification of

Roman law

Roman law is the law, legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (), to the (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor Justinian I.

Roman law also den ...

; the first effort—the ''

Codex Theodosianus''—was completed in 438.

[Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 81–83] Under Emperor Justinian (r. 527–565), another compilation took place—the ''

Corpus Juris Civilis

The ''Corpus Juris'' (or ''Iuris'') ''Civilis'' ("Body of Civil Law") is the modern name for a collection of fundamental works in jurisprudence, enacted from 529 to 534 by order of Byzantine Emperor Justinian I. It is also sometimes referred ...

''.

[Bauer ''History of the Medieval World'' pp. 200–202] Justinian also oversaw the construction of the

Hagia Sophia

Hagia Sophia (; ; ; ; ), officially the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque (; ), is a mosque and former Church (building), church serving as a major cultural and historical site in Istanbul, Turkey. The last of three church buildings to be successively ...

in Constantinople and the reconquest of North Africa from the Vandals and Italy from the Ostrogoths,

under

Belisarius

BelisariusSometimes called Flavia gens#Later use, Flavius Belisarius. The name became a courtesy title by the late 4th century, see (; ; The exact date of his birth is unknown. March 565) was a military commander of the Byzantine Empire under ...

(d. 565).

[Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 126, 130] The conquest of Italy was not complete, as a deadly outbreak of

plague in 542 led to the rest of Justinian's reign concentrating on defensive measures rather than further conquests.

[Bauer ''History of the Medieval World'' pp. 206–213]

At the Emperor's death, the Byzantines had control of

most of Italy, North Africa, and a small foothold in southern Spain. Historians have criticised Justinian's reconquests for overextending his realm and setting the stage for the

early Muslim conquests

The early Muslim conquests or early Islamic conquests (), also known as the Arab conquests, were initiated in the 7th century by Muhammad, the founder of Islam. He established the first Islamic state in Medina, Arabian Peninsula, Arabia that ...

, but many of the difficulties faced by Justinian's successors were due not just to over-taxation to pay for his wars but to the essentially civilian nature of the empire, which made raising troops difficult.

[Brown "Transformation of the Roman Mediterranean" ''Oxford Illustrated History of Medieval Europe'' pp. 8–9]

In the Eastern Empire, the Slavs' slow infiltration of the Balkans added further difficulty for Justinian's successors. It began gradually, but by the late 540s, Slavic tribes were in

Thrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

and

Illyrium and had defeated an imperial army near

Adrianople

Edirne (; ), historically known as Orestias, Adrianople, is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the Edirne Province, province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated from the Greek and from the Bulgarian borders, Edirne was the second c ...

in 551. In the 560s, the

Avars began to expand from their base on the north bank of the

Danube

The Danube ( ; see also #Names and etymology, other names) is the List of rivers of Europe#Longest rivers, second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest sou ...

; by the end of the 6th century, they were the dominant power in Central Europe and routinely able to force the Eastern emperors to pay tribute. They remained a strong power until 796.

[James ''Europe's Barbarians'' pp. 95–99]

An additional problem to face the empire came as a result of the involvement of Emperor

Maurice (r. 582–602) in Persian politics when he intervened in a

succession dispute. This led to a period of peace, but when Maurice was overthrown,

the Persians invaded and during the reign of Emperor

Heraclius

Heraclius (; 11 February 641) was Byzantine emperor from 610 to 641. His rise to power began in 608, when he and his father, Heraclius the Elder, the Exarch of Africa, led a revolt against the unpopular emperor Phocas.

Heraclius's reign was ...

(r. 610–641) controlled large chunks of the empire, including Egypt, Syria, and

Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

until Heraclius' successful counterattack. In 628, the empire secured a peace treaty and recovered its lost territories.

[Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 140–143]

Western society

In Western Europe, some older Roman elite families died out while others became more involved with ecclesiastical than secular affairs. Values attached to

Latin scholarship and

education

Education is the transmission of knowledge and skills and the development of character traits. Formal education occurs within a structured institutional framework, such as public schools, following a curriculum. Non-formal education als ...

mostly disappeared, and while literacy remained important, it became a practical skill rather than a sign of elite status. In the 4th century,

Jerome

Jerome (; ; ; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was an early Christian presbyter, priest, Confessor of the Faith, confessor, theologian, translator, and historian; he is commonly known as Saint Jerome.

He is best known ...

(d. 420) dreamed that God rebuked him for spending more time reading

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

than the

Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

. By the 6th century,

Gregory of Tours

Gregory of Tours (born ; 30 November – 17 November 594 AD) was a Gallo-Roman historian and Bishop of Tours during the Merovingian period and is known as the "father of French history". He was a prelate in the Merovingian kingdom, encom ...

(d. 594) had a similar dream, but instead of being chastised for reading Cicero, he was chastised for learning

shorthand

Shorthand is an abbreviated symbolic writing method that increases speed and brevity of writing as compared to Cursive, longhand, a more common method of writing a language. The process of writing in shorthand is called stenography, from the Gr ...

.

[Brown ''World of Late Antiquity'' pp. 174–175] By the late 6th century, the principal means of religious instruction in the Church had become music and art rather than the book.

[Brown ''World of Late Antiquity'' p. 181] Most intellectual efforts went towards imitating classical scholarship, but some

original works were created, along with now-lost oral compositions. The writings of

Sidonius Apollinaris (d. 489),

Cassiodorus

Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator (c. 485 – c. 585), commonly known as Cassiodorus (), was a Christian Roman statesman, a renowned scholar and writer who served in the administration of Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths. ''Senato ...

(d. ), and

Boethius

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known simply as Boethius (; Latin: ''Boetius''; 480–524 AD), was a Roman Roman Senate, senator, Roman consul, consul, ''magister officiorum'', polymath, historian, and philosopher of the Early Middl ...

(d. c. 525) were typical of the age.

[Brown "Transformation of the Roman Mediterranean" ''Oxford Illustrated History of Medieval Europe'' pp. 45–49]

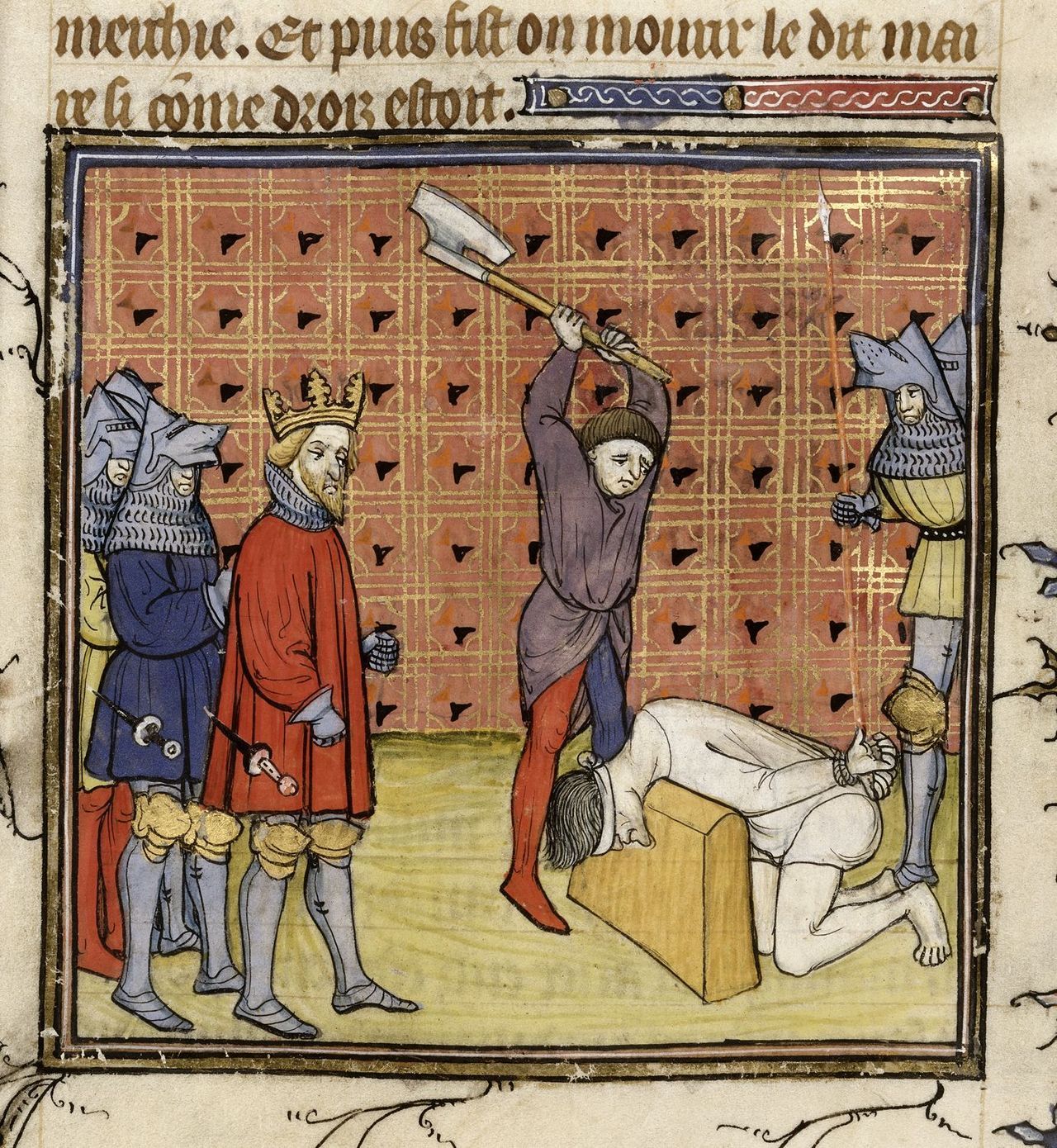

Changes also occurred among laypeople, as aristocratic culture focused on great feasts held in halls rather than on literary pursuits. Clothing for the elites was richly embellished with jewels and gold. Lords and kings supported the entourages of fighters who formed the backbone of the military forces. Family ties within the elites were important, as were the virtues of loyalty, courage, and honour. These ties led to the prevalence of feuds in aristocratic society, including those related by Gregory of Tours in

Merovingian

The Merovingian dynasty () was the ruling family of the Franks from around the middle of the 5th century until Pepin the Short in 751. They first appear as "Kings of the Franks" in the Roman army of northern Gaul. By 509 they had united all the ...

Gaul. Most feuds seem to have ended quickly with the payment of some

compensation.

[Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 189–193] Women took part in aristocratic society mainly in their roles as wives and mothers of men, with the role of mother of a ruler being especially prominent in Merovingian Gaul. In

Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

society, the lack of many child rulers meant a lesser role for women as queen mothers, but this was compensated for by the increased role played by

abbesses of monasteries. Only in Italy does it appear that women were always considered under the protection and control of a male relative.

[Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 195–199]

Peasant society is much less documented than the nobility. Most of the surviving information available to historians comes from

archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

; few detailed written records documenting peasant life remain from before the 9th century. Most of the descriptions of the lower classes come from either

law codes or writers from the upper classes.

[Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' p. 204] Landholding patterns in the West were not uniform; some areas had greatly fragmented landholding patterns, but in other areas, large contiguous blocks of land were the norm. These differences allowed for a wide variety of peasant societies, some dominated by aristocratic landholders and others having great autonomy.

[Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 205–210] Land settlement also varied greatly. Some peasants lived in large settlements that numbered as many as 700 inhabitants. Others lived in small groups of a few families and lived on isolated farms spread over the countryside. There were also areas where the pattern was a mix of two or more systems.

[Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 211–212] Unlike in the late Roman period, there was no sharp break between the legal status of the free peasant and the aristocrat, and a free peasant's family could rise into the aristocracy over several generations through military service to a powerful lord.

[Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' p. 215]

Roman city life and culture changed greatly in the early Middle Ages. Although Italian cities remained inhabited, they contracted significantly in size. For instance, Rome shrank from hundreds of thousands to around 30,000 by the end of the 6th century.

Roman temple

Ancient Roman temples were among the most important buildings in culture of ancient Rome, Roman culture, and some of the richest buildings in Architecture of ancient Rome, Roman architecture, though only a few survive in any sort of complete ...

s were converted into

Christian churches and city walls remained in use.

[Brown "Transformation of the Roman Mediterranean" ''Oxford Illustrated History of Medieval Europe'' pp. 24–26] In Northern Europe, cities also shrank, while civic monuments and other public buildings were raided for building materials. The establishment of new kingdoms often meant some growth for the towns chosen as capitals.

[Gies and Gies ''Life in a Medieval City'' pp. 3–4] Although there had been

Jewish communities in many Roman cities, the

Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

suffered periods of persecution after the conversion of the empire to Christianity. Officially, they were tolerated, if subject to conversion efforts, and were sometimes encouraged to settle in new areas.

[Loyn "Jews" ''Middle Ages'' p. 191]

Rise of Islam

Religious beliefs in the Eastern Roman Empire and Iran were in flux during the late sixth and early seventh centuries.

Judaism

Judaism () is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic, Monotheism, monotheistic, ethnic religion that comprises the collective spiritual, cultural, and legal traditions of the Jews, Jewish people. Religious Jews regard Judaism as their means of o ...

was an active proselytising faith, and at least one

Arab

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of years ...

political leader converted to it. In addition Jewish theologians wrote polemics defending their religion against Christian and Islamic influences.

Christianity had active missions competing with the Persians'

Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism ( ), also called Mazdayasnā () or Beh-dīn (), is an Iranian religions, Iranian religion centred on the Avesta and the teachings of Zoroaster, Zarathushtra Spitama, who is more commonly referred to by the Greek translation, ...

in seeking converts, especially among residents of the

Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

. All these strands came together with the emergence of

Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

in Arabia during the lifetime of

Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

(d. 632).

[Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 143–145] After his death, Islamic forces conquered much of the Eastern Roman Empire and Persia, starting with

Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

in 634–635, continuing with

Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

between 637 and 642, reaching

Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

in 640–641,

North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

in the later seventh century, and the

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

in 711.

[Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 149–151] By 714, Islamic forces controlled much of the peninsula in a region they called

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

.

[Reilly ''Medieval Spains'' pp. 52–53]

The Islamic conquests reached their peak in the mid-eighth century. The defeat of Muslim forces at the

Battle of Tours in 732 led to the reconquest of southern France by the Franks, but the main reason for the halt of Islamic growth in Europe was the overthrow of the

Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate or Umayyad Empire (, ; ) was the second caliphate established after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and was ruled by the Umayyad dynasty. Uthman ibn Affan, the third of the Rashidun caliphs, was also a member o ...

and its replacement by the

Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate or Abbasid Empire (; ) was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib (566–653 CE), from whom the dynasty takes ...

. The Abbasids moved their capital to

Baghdad

Baghdad ( or ; , ) is the capital and List of largest cities of Iraq, largest city of Iraq, located along the Tigris in the central part of the country. With a population exceeding 7 million, it ranks among the List of largest cities in the A ...

and were more concerned with the Middle East than Europe, losing control of sections of the Muslim lands. Umayyad descendants took over the Iberian Peninsula, the

Aghlabids

The Aghlabid dynasty () was an Arab dynasty centered in Ifriqiya (roughly present-day Tunisia) from 800 to 909 that conquered parts of Sicily, Southern Italy, and possibly Sardinia, nominally as vassals of the Abbasid Caliphate. The Aghlabids ...

controlled North Africa, and the

Tulunids became rulers of Egypt.

[Brown "Transformation of the Roman Mediterranean" ''Oxford Illustrated History of Medieval Europe'' p. 15] By the middle of the 8th century, new trading patterns were emerging in the Mediterranean; trade between the Franks and the Arabs replaced the old

Roman economy. Franks traded timber, furs, swords, and enslaved people in return for silks and other fabrics, spices, and precious metals from the Arabs.

[Cunliffe ''Europe Between the Oceans'' pp. 427–428]

Trade and economy

The migrations and invasions of the 4th and 5th centuries disrupted trade networks around the Mediterranean. African goods stopped being imported into Europe, first disappearing from the interior and, by the 7th century, found only in a few cities such as Rome or

Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

. By the end of the 7th century, under the impact of the

Muslim conquests, African products were no longer found in Western Europe. Replacing goods from long-range trade with local products was a trend throughout the old Roman lands in the Early Middle Ages. This was especially marked in the lands that did not lie on the Mediterranean, such as northern Gaul or Britain. Non-local goods appearing in the archaeological record are usually luxury goods. In northern Europe, not only were the trade networks local, but the goods carried were simple, with little pottery or other complex products. Around the Mediterranean, pottery remained prevalent and appears to have been traded over medium-range networks, not just produced locally.

[Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 218–219]

The various Germanic states in the west all had

coin

A coin is a small object, usually round and flat, used primarily as a medium of exchange or legal tender. They are standardized in weight, and produced in large quantities at a mint in order to facilitate trade. They are most often issued by ...

ages that imitated existing Roman and Byzantine forms. Gold continued to be minted until the end of the 7th century in 693–694, when it was replaced by silver in the Merovingian kingdom. The basic Frankish silver coin was the

denarius

The ''denarius'' (; : ''dēnāriī'', ) was the standard Ancient Rome, Roman silver coin from its introduction in the Second Punic War to the reign of Gordian III (AD 238–244), when it was gradually replaced by the ''antoninianus''. It cont ...

or

denier, while the Anglo-Saxon version was called a

penny

A penny is a coin (: pennies) or a unit of currency (: pence) in various countries. Borrowed from the Carolingian denarius (hence its former abbreviation d.), it is usually the smallest denomination within a currency system. At present, it is ...

. From these areas, the denier or penny spread throughout Europe from 700 to 1000. Copper or bronze coins were not struck, nor were gold, except in Southern Europe. No silver coins denominated in multiple units were minted.

[Grierson "Coinage and currency" ''Middle Ages'']

Church and monasticism

Christianity was a major unifying factor between Eastern and Western Europe before the Arab conquests, but the conquest of North Africa sundered maritime connections between those areas. Increasingly, the Byzantine Church differed in language, practices, and

liturgy

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and participation in the sacred through activities reflecting praise, thanksgiving, remembra ...

from the Western Church. The Eastern Church used Greek instead of Western Latin. Theological and political differences emerged, and by the early and middle 8th century, issues such as

iconoclasm,

clerical marriage, and

state control of the Church had widened to the extent that the cultural and religious differences were more significant than the similarities.

[Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 218–233] A formal break known as the

East–West Schism

The East–West Schism, also known as the Great Schism or the Schism of 1054, is the break of communion (Christian), communion between the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church. A series of Eastern Orthodox – Roman Catholic eccle ...

came in 1054, when the

papacy

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

and the

patriarchy of Constantinople clashed over

papal supremacy and

excommunicated each other, which led to the division of Christianity into two Churches—the Western branch became the

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

and the Eastern branch the

Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, officially the Orthodox Catholic Church, and also called the Greek Orthodox Church or simply the Orthodox Church, is List of Christian denominations by number of members, one of the three major doctrinal and ...

.

[Davies ''Europe'' pp. 328–332]

The

ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Empire survived the movements and invasions in the West mostly intact. Still, the papacy was little regarded, and few of the Western

bishop

A bishop is an ordained member of the clergy who is entrusted with a position of Episcopal polity, authority and oversight in a religious institution. In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance and administration of di ...

s looked to the bishop of Rome for religious or political leadership.

Many of the popes before 750 were more concerned with Byzantine affairs and Eastern theological controversies. The register, or archived copies of the letters, of Pope

Gregory the Great

Pope Gregory I (; ; – 12 March 604), commonly known as Saint Gregory the Great (; ), was the 64th Bishop of Rome from 3 September 590 until his death on 12 March 604. He is known for instituting the first recorded large-scale mission from Rom ...

(pope 590–604) survived. Of those 850 letters, most were concerned with affairs in Italy or Constantinople. The only part of Western Europe where the papacy had influence was Britain, where Gregory had sent the

Gregorian mission

The Gregorian missionJones "Gregorian Mission" ''Speculum'' p. 335 or Augustinian missionMcGowan "Introduction to the Corpus" ''Companion to Anglo-Saxon Literature'' p. 17 was a Christian mission sent by Pope Pope Gregory I, Gregory the Great ...

in 597 to convert the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity.

[Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 170–172] Irish missionaries were most active in Western Europe between the 5th and the 7th centuries, going first to England and Scotland and then on to the continent. Under such

monk

A monk (; from , ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a man who is a member of a religious order and lives in a monastery. A monk usually lives his life in prayer and contemplation. The concept is ancient and can be seen in many reli ...

s as

Columba

Columba () or Colmcille (7 December 521 – 9 June 597 AD) was an Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is today Scotland at the start of the Hiberno-Scottish mission. He founded the important abbey ...

(d. 597) and

Columbanus (d. 615), they founded monasteries, taught in Latin and Greek, and authored secular and religious works.

[Colish ''Medieval Foundations'' pp. 62–63]

The Early Middle Ages witnessed the rise of

monasticism

Monasticism (; ), also called monachism or monkhood, is a religion, religious way of life in which one renounces world (theology), worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual activities. Monastic life plays an important role in many Chr ...

in the West. The shape of European monasticism was determined by traditions and ideas that originated with the

Desert Fathers

The Desert Fathers were early Christian hermits and ascetics, who lived primarily in the Wadi El Natrun, then known as ''Skete'', in Roman Egypt, beginning around the Christianity in the ante-Nicene period, third century. The ''Sayings of the Dese ...

of

Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

and

Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

. Most European monasteries were of the type that focuses on the community experience of the spiritual life, called

cenobitism, which was pioneered by

Pachomius

Pachomius (; ''Pakhomios''; ; c. 292 – 9 May 348 AD), also known as Saint Pachomius the Great, is generally recognized as the founder of Christian cenobitic monasticism. Copts, Coptic churches celebrate his feast day on 9 May, and Eastern Or ...

(d. 348) in the 4th century. Monastic ideals spread from Egypt to Western Europe in the 5th and 6th centuries through

hagiographical literature such as the ''

Life of Anthony''.

[Lawrence ''Medieval Monasticism'' pp. 10–13] Benedict of Nursia

Benedict of Nursia (; ; 2 March 480 – 21 March 547), often known as Saint Benedict, was a Great Church, Christian monk. He is famed in the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Lutheran Churches, the Anglican Communion, and Old ...

(d. 547) wrote the

Benedictine Rule for Western monasticism during the 6th century, detailing the administrative and spiritual responsibilities of a community of monks led by an

abbot