Marbled Paper on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Paper marbling is a method of

Paper marbling is a method of

There are several methods for making marbled

There are several methods for making marbled

Paper marbling is a method of

Paper marbling is a method of aqueous

An aqueous solution is a solution in which the solvent is water. It is mostly shown in chemical equations by appending (aq) to the relevant chemical formula. For example, a solution of table salt, also known as sodium chloride (NaCl), in wat ...

surface design, which can produce patterns similar to smooth marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock consisting of carbonate minerals (most commonly calcite (CaCO3) or Dolomite (mineral), dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2) that have recrystallized under the influence of heat and pressure. It has a crystalline texture, and is ty ...

or other kinds of stone

In geology, rock (or stone) is any naturally occurring solid mass or aggregate of minerals or mineraloid matter. It is categorized by the minerals included, its Chemical compound, chemical composition, and the way in which it is formed. Rocks ...

. The patterns are the result of color floated on either plain water or a viscous

Viscosity is a measure of a fluid's rate-dependent resistance to a change in shape or to movement of its neighboring portions relative to one another. For liquids, it corresponds to the informal concept of ''thickness''; for example, syrup h ...

solution known as size

Size in general is the Magnitude (mathematics), magnitude or dimensions of a thing. More specifically, ''geometrical size'' (or ''spatial size'') can refer to three geometrical measures: length, area, or volume. Length can be generalized ...

, and then carefully transferred to an absorbent surface, such as paper

Paper is a thin sheet material produced by mechanically or chemically processing cellulose fibres derived from wood, Textile, rags, poaceae, grasses, Feces#Other uses, herbivore dung, or other vegetable sources in water. Once the water is dra ...

or fabric. Through several centuries, people have applied marbled materials to a variety of surfaces. It is often employed as a writing surface for calligraphy

Calligraphy () is a visual art related to writing. It is the design and execution of lettering with a pen, ink brush, or other writing instruments. Contemporary calligraphic practice can be defined as "the art of giving form to signs in an e ...

, and especially book covers and endpapers in bookbinding

Bookbinding is the process of building a book, usually in codex format, from an ordered stack of paper sheets with one's hands and tools, or in modern publishing, by a series of automated processes. Firstly, one binds the sheets of papers alon ...

and stationery

Stationery refers to writing materials, including cut paper, envelopes, continuous form paper, and other office supplies. Stationery usually specifies materials to be written on by hand (e.g., letter paper) or by equipment such as computer p ...

. Part of its appeal is that each print is a unique monotype

Monotyping is a type of printmaking made by drawing or painting on a smooth, non-absorbent surface. The surface, or matrix, was historically a copper etching plate, but in contemporary work it can vary from zinc or glass to acrylic glass. The ...

.

Procedure

There are several methods for making marbled

There are several methods for making marbled paper

Paper is a thin sheet material produced by mechanically or chemically processing cellulose fibres derived from wood, Textile, rags, poaceae, grasses, Feces#Other uses, herbivore dung, or other vegetable sources in water. Once the water is dra ...

s. A shallow tray is filled with water, and various kinds of ink or paint colors are carefully applied to the surface with an ink brush

A Chinese writing brush () is a paintbrush used as a writing tool in Chinese calligraphy as well as in Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese which all have roots in Chinese calligraphy. They are also used in Chinese painting and other brush pain ...

. Various additives or surfactant

Surfactants are chemical compounds that decrease the surface tension or interfacial tension between two liquids, a liquid and a gas, or a liquid and a solid. The word ''surfactant'' is a Blend word, blend of "surface-active agent",

coined in ...

chemicals are used to help float the colors. A drop of "negative" color made of plain water with the addition of surfactant

Surfactants are chemical compounds that decrease the surface tension or interfacial tension between two liquids, a liquid and a gas, or a liquid and a solid. The word ''surfactant'' is a Blend word, blend of "surface-active agent",

coined in ...

is used to drive the drop of color into a ring. The process is repeated until the surface of the water is covered with concentric rings. The floating colors are then carefully manipulated either by blowing on them directly or through a straw, fanning the colors, or carefully using a human hair to stir the colors.

In the 19th century, the Kyoto

Kyoto ( or ; Japanese language, Japanese: , ''Kyōto'' ), officially , is the capital city of Kyoto Prefecture in the Kansai region of Japan's largest and most populous island of Honshu. , the city had a population of 1.46 million, making it t ...

-based Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

master Tokutaro Yagi developed an alternative method that employed a split piece of bamboo

Bamboos are a diverse group of mostly evergreen perennial plant, perennial flowering plants making up the subfamily (biology), subfamily Bambusoideae of the grass family Poaceae. Giant bamboos are the largest members of the grass family, in th ...

to gently stir the colors, resulting in concentric spiral designs. A sheet of ''washi

is traditional Japanese paper processed by hand using fibers from the inner bark of the gampi tree, the mitsumata shrub (''Edgeworthia chrysantha''), or the paper mulberry (''kōzo'') bush.

''Washi'' is generally tougher than ordinary ...

'' paper is then carefully laid onto the water surface to capture the floating design. The paper, which is often made of (paper mulberry

The paper mulberry (''Broussonetia papyrifera'', syn. ''Morus papyrifera'' L.) is a species of flowering plant in the family Moraceae. It is native to Asia,unsized and strong enough to withstand being immersed in water without tearing.

Another method of marbling more familiar to Europeans and Americans is made on the surface of a viscous mucilage, known as ''size'' or ''sizing'' in English. While this method is often referred to as " Turkish marbling" in English and called in modern Turkish, ethnic

An intriguing reference which some think may be a form of marbling is found in a compilation completed in 986 CE entitled ''Four Treasures of the Scholar's Study'' (; ) or edited by the 10th century

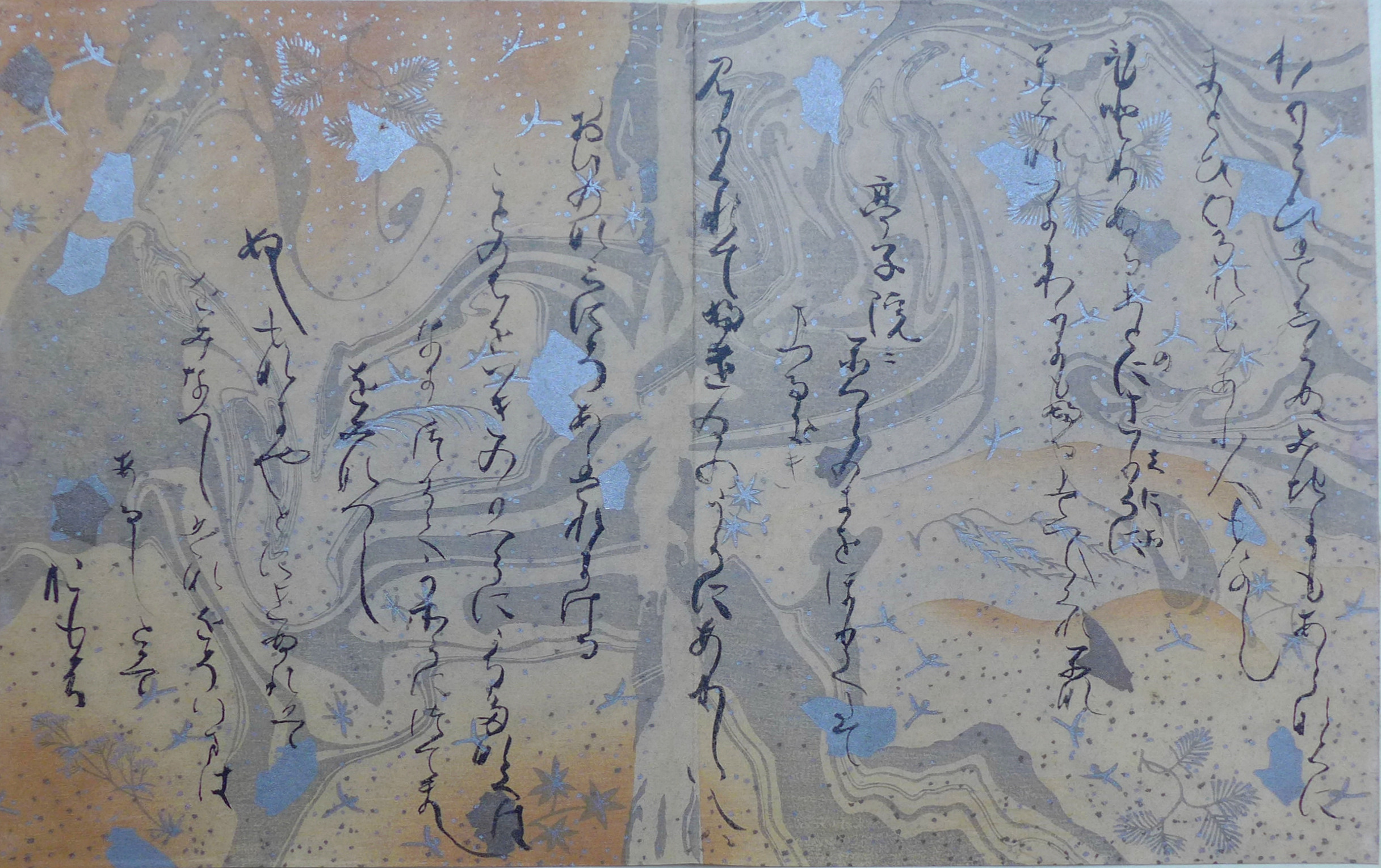

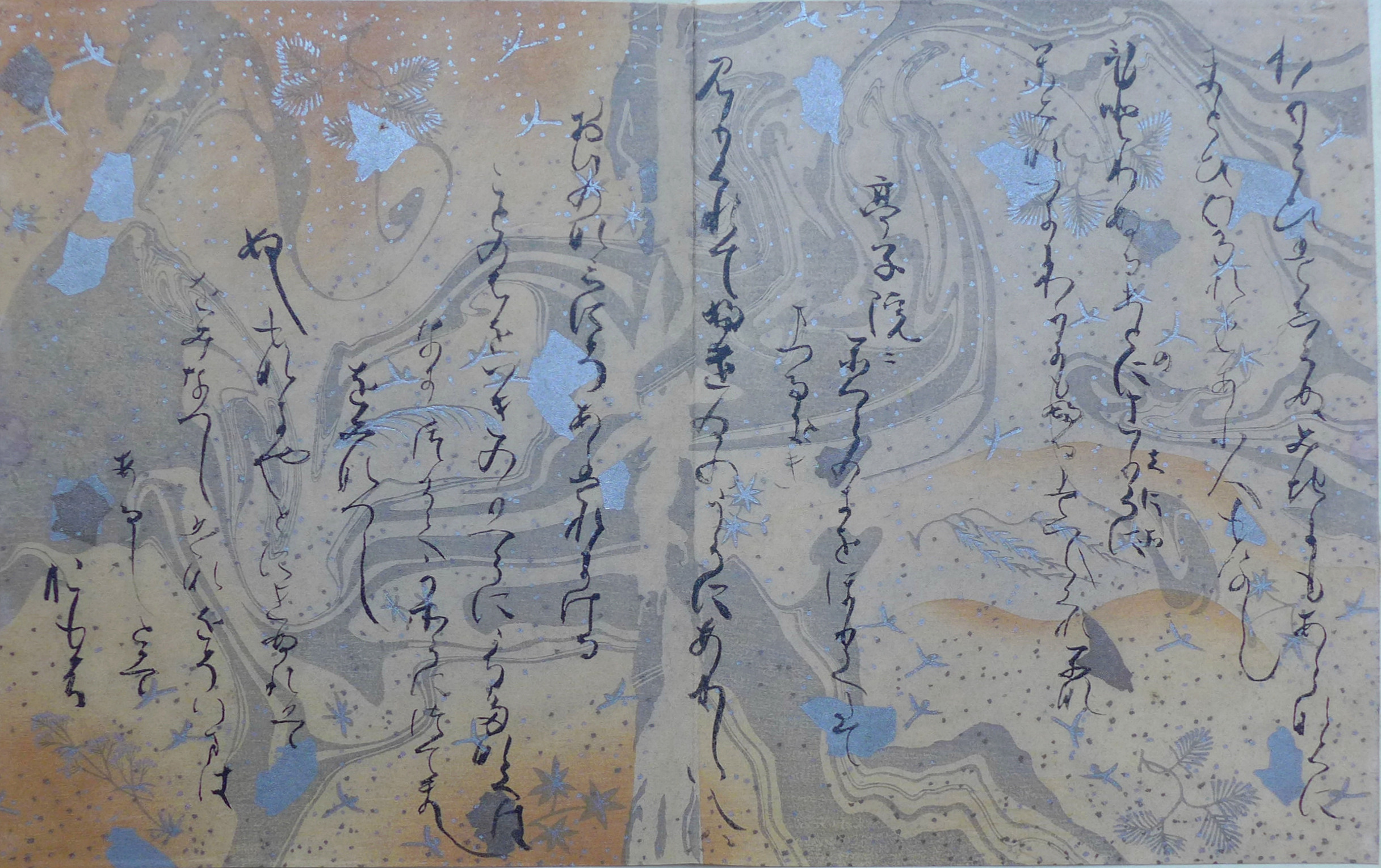

An intriguing reference which some think may be a form of marbling is found in a compilation completed in 986 CE entitled ''Four Treasures of the Scholar's Study'' (; ) or edited by the 10th century  In contrast, , which means 'floating ink' in Japanese, appears to be the earliest form of marbling during the 12th-century Sanjuurokuninshuu , located in Nishihonganji , Kyoto. Author Einen Miura states that the oldest reference to papers are in the ''waka'' poems of Shigeharu, (825–880 CE), a son of the famed Heian-era poet Narihira (Muira 14) in the

In contrast, , which means 'floating ink' in Japanese, appears to be the earliest form of marbling during the 12th-century Sanjuurokuninshuu , located in Nishihonganji , Kyoto. Author Einen Miura states that the oldest reference to papers are in the ''waka'' poems of Shigeharu, (825–880 CE), a son of the famed Heian-era poet Narihira (Muira 14) in the

The method of floating colors on the surface of

The method of floating colors on the surface of

File:Art of Bookbinding p108 School of Arts cut.png, Marbling tray and tools from ''School of Arts'' (1750)

File:Encyclopedie volume 4-275.png, Marblers at work, from ''l'Encyclopedie'' of Diderot and d'Alembert

File:Encyclopedie volume 4-276.png, An edge marbler and paper finisher with related equipment, from ''l'Encyclopedie''

Marblers still make marbled paper and fabric, even applying the technique to three-dimensional surfaces. Aside from continued traditional applications, artists now explore using the method as a kind of painting technique, and as an element in

Marblers still make marbled paper and fabric, even applying the technique to three-dimensional surfaces. Aside from continued traditional applications, artists now explore using the method as a kind of painting technique, and as an element in

File:Marbled endpaper, between 1720 and 1770, from Quintilian ed. Burmann, Leiden 1720.jpg, Marbled endpaper from a book bound in the Netherlands or Germany between 1720 and 1770

File:PaperMarbling005France1735.jpg, Marbled endpaper from a book bound in France around 1735

File:PaperMarbling001England1830.jpg, Paper marbling from a book bound in England around 1830

File:Galileo-6.jpg, Paper marbling in a 1718 copy of '' Opere di Galileo Galilei''

File:PaperMarbling003France1880.jpg, Marbled endpaper from a book bound in France around 1880

File:PaperMarbling003France1880Detail.jpg, Marbled endpaper from a book bound in France around 1880 (detail)

File:Combed Marbled Design (London, 1847).jpg, A combed marbled pattern from the front flyleaf of a binding of ''The Playmate: A Pleasant Companion for Spare Hours'' by Joseph Cundall, Printed by Barclay, 1847.

File:Combed marbled paper.jpg, Combed marbled paper, from the front flyleaf of a binding of ''Oriental Fragments'' by Maria Hack, printed in London for Harvey and Dartman, 1828.

File:1902MarbledTheLifeOfTheBeeByMaeterlinck.jpg, 1912 edition of Dodd, Mead and Company's The Life of the Bee by

See also

Richard J. Wolfe Collection of Paper Marbling and Allied Book Arts.

University of Chicago Library

Decorated and Decorative Paper Collection

from the

Marbled paper (archived 2019)

by Joel Silver, from Nov./Dec. 2005 issue of ''Fine Books'' magazine

Art of the Marbler

1970 film by Bedfordshire Record Office of Cockerell marbling

Ebru Art

A short video from the American Islamic College that shows artist Garip Ay perform the art of Turkish Ebru {{Authority control Paper Paper art Handicrafts

Turkic peoples

Turkic peoples are a collection of diverse ethnic groups of West Asia, West, Central Asia, Central, East Asia, East, and North Asia as well as parts of Europe, who speak Turkic languages.. "Turkic peoples, any of various peoples whose members ...

were not the only practitioners of the art, as Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

, Tajiks

Tajiks (; ; also spelled ''Tadzhiks'' or ''Tadjiks'') is the name of various Persian-speaking Eastern Iranian groups of people native to Central Asia, living primarily in Afghanistan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. Even though the term ''Tajik'' ...

, and people of India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

n origin also made these papers. The use of the term ''Turkish'' by Europeans

Europeans are the focus of European ethnology, the field of anthropology related to the various ethnic groups that reside in the states of Europe. Groups may be defined by common ancestry, language, faith, historical continuity, etc. There are ...

is most likely due to both the fact that many first encountered the art in Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

, as well as essentialist references to all Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

s as Turks, much as Europeans were referred to as in Turkish and Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

, which literally means Frankish

Frankish may refer to:

* Franks, a Germanic tribe and their culture

** Frankish language or its modern descendants, Franconian languages, a group of Low Germanic languages also commonly referred to as "Frankish" varieties

* Francia, a post-Roman ...

.

Historic forms of marbling used both organic and inorganic pigments mixed with water for colors, and sizes were traditionally made from gum tragacanth (''Astragalus

Astragalus may refer to:

* ''Astragalus'' (plant), a large genus of herbs and small shrubs

*Astragalus (bone)

The talus (; Latin for ankle or ankle bone; : tali), talus bone, astragalus (), or ankle bone is one of the group of foot bones known ...

'' spp.), gum karaya, guar gum

Guar gum, also called guaran, is a galactomannan polysaccharide extracted from guar beans that has thickening and stabilizing properties useful in food, feed, and industrial applications. The guar seeds are mechanically dehusked, hydrated, mi ...

, fenugreek

Fenugreek (; ''Trigonella foenum-graecum'') is an annual plant in the family Fabaceae, with leaves consisting of three small Glossary_of_leaf_morphology#Leaf_and_leaflet_shapes, obovate to oblong leaflets. It is cultivated worldwide as a semiar ...

(''Trigonella foenum-graecum''), fleabane, linseed

Flax, also known as common flax or linseed, is a flowering plant, ''Linum usitatissimum'', in the family Linaceae. It is cultivated as a food and fiber crop in regions of the world with temperate climates. In 2022, France produced 75% of the ...

, and psyllium

Psyllium (), or ispaghula (), is the common name used for several members of the plant genus ''Plantago'' whose seeds are used commercially for the production of mucilage. Psyllium is mainly used as a dietary fiber to relieve symptoms of both ...

. Since the late 19th century, a boiled extract of the carrageenan

Carrageenans or carrageenins ( ; ) are a family of natural linear sulfation, sulfated polysaccharides. They are extracted from red algae, red edible seaweeds. Carrageenans are widely used in the food industry, for their gelling, thickening, an ...

-rich alga known as Irish moss (''Chondrus crispus

''Chondrus crispus''—commonly called Irish moss or carrageenan moss (Irish ''carraigín'', "little rock")—is a species of red algae which grows abundantly along the rocky parts of the Atlantic coasts of Europe and North America. In its fresh ...

''), has been employed for sizing. Today, many marblers use powdered carrageenan extracted from various seaweeds. Another plant-derived mucilage

Mucilage is a thick gluey substance produced by nearly all plants and some microorganisms. These microorganisms include protists which use it for their locomotion, with the direction of their movement always opposite to that of the secretion of ...

is made from sodium alginate

Alginic acid, also called algin, is a naturally occurring, edible polysaccharide found in brown algae. It is hydrophilic and forms a viscous gum when hydrated. When the alginic acid binds with sodium and calcium ions, the resulting salts are kn ...

. In recent years, a synthetic size made from hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, a common ingredient in instant wallpaper paste

Adhesive flakes that are mixed with water to produce wallpaper paste

Wallpaper adhesive or wallpaper paste is a specific adhesive, based on modified starch, methylcellulose, or clay which is used to fix wallpaper to walls.

Wallpaper pastes ha ...

, is often used as a size for floating acrylic and oil paint

Oil paint is a type of slow-drying paint that consists of particles of pigment suspended in a drying oil, commonly linseed oil. Oil paint also has practical advantages over other paints, mainly because it is waterproof.

The earliest surviving ...

s.

In the size-based method, colors made from pigments

A pigment is a powder used to add or alter color or change visual appearance. Pigments are completely or nearly solubility, insoluble and reactivity (chemistry), chemically unreactive in water or another medium; in contrast, dyes are colored sub ...

are mixed with a surfactant

Surfactants are chemical compounds that decrease the surface tension or interfacial tension between two liquids, a liquid and a gas, or a liquid and a solid. The word ''surfactant'' is a Blend word, blend of "surface-active agent",

coined in ...

such as ox gall. Sometimes, oil or turpentine

Turpentine (which is also called spirit of turpentine, oil of turpentine, terebenthine, terebenthene, terebinthine and, colloquially, turps) is a fluid obtainable by the distillation of resin harvested from living trees, mainly pines. Principall ...

may be added to a color, to achieve special effects. The colors are then spattered or dropped onto the size, one color after another until there is a dense pattern of several colors. Straw from the broom corn was used to make a kind of whisk for sprinkling the paint, or horsehair

Horsehair is the long hair growing on the Mane (horse), manes and Tail (horse), tails of horses. It is used for various purposes, including upholstery, brushes, the Bow (music), bows of musical instruments, a hard-wearing Textile, fabric called ...

to create a kind of drop-brush. Each successive layer of pigment

A pigment is a powder used to add or alter color or change visual appearance. Pigments are completely or nearly solubility, insoluble and reactivity (chemistry), chemically unreactive in water or another medium; in contrast, dyes are colored sub ...

spreads slightly less than the last, and the colors may require additional surfactant

Surfactants are chemical compounds that decrease the surface tension or interfacial tension between two liquids, a liquid and a gas, or a liquid and a solid. The word ''surfactant'' is a Blend word, blend of "surface-active agent",

coined in ...

to float and uniformly expand. Once the colors are laid down, various tools and implements such as rakes, combs, and styluses are often used in a series of movements to create more intricate designs.

Cobb paper or cloth is often mordant

A mordant or dye fixative is a substance used to set (i.e., bind) dyes on fabrics. It does this by forming a coordination complex with the dye, which then attaches to the fabric (or tissue). It may be used for dyeing fabrics or for intensifying ...

ed beforehand with aluminium sulfate

Aluminium sulfate is a salt with the chemical formula, formula . It is soluble in water and is mainly used as a Coagulation (water treatment), coagulating agent (promoting particle collision by neutralizing charge) in the purification of drinking ...

(alum) and gently laid onto the floating colors (although methods such as Turkish and Japanese do not require mordanting). The colors are thereby transferred and adhered to the surface of the paper or material. The paper or material is then carefully lifted off the size and hung up to dry. Some marblers gently drag the paper over a rod to draw off the excess size. If necessary, excess bleeding colors and sizing can be rinsed off, and then the paper or fabric is allowed to dry. After the print is made, any color residues remaining on the size are carefully skimmed off of the surface, in order to clear it before starting a new pattern.

Contemporary marblers employ a variety of modern materials, some in place of or in combination with the more traditional ones. A wide variety of colors are used today in place of the historic pigment colors. Plastic broom straw can be used instead of broom corn, as well as bamboo sticks, plastic pipettes

A pipette (sometimes spelled as pipet) is a type of laboratory tool commonly used in chemistry and biology to transport a measured volume of liquid, often as a media dispenser. Pipettes come in several designs for various purposes with differing ...

, and eye droppers to drop the colors on the surface of the size. Ox gall is still commonly used as a surfactant

Surfactants are chemical compounds that decrease the surface tension or interfacial tension between two liquids, a liquid and a gas, or a liquid and a solid. The word ''surfactant'' is a Blend word, blend of "surface-active agent",

coined in ...

for watercolors and gouache

Gouache (; ), body color, or opaque watercolor is a water-medium paint consisting of natural pigment, water, a binding agent (usually gum arabic or dextrin), and sometimes additional inert material. Gouache is designed to be opaque. Gouach ...

, but synthetic surfactants

Surfactants are chemical compounds that decrease the surface tension or interfacial tension between two liquids, a liquid and a gas, or a liquid and a solid. The word ''surfactant'' is a blend of "surface-active agent",

coined in 1950. As t ...

are used in conjunction with acrylic, PVA, and oil-based paints.

History in East Asia

An intriguing reference which some think may be a form of marbling is found in a compilation completed in 986 CE entitled ''Four Treasures of the Scholar's Study'' (; ) or edited by the 10th century

An intriguing reference which some think may be a form of marbling is found in a compilation completed in 986 CE entitled ''Four Treasures of the Scholar's Study'' (; ) or edited by the 10th century scholar-official

The scholar-officials, also known as literati, scholar-gentlemen or scholar-bureaucrats (), were government officials and prestigious scholars in Chinese society, forming a distinct social class.

Scholar-officials were politicians and governmen ...

(958–996 CE). This compilation contains information on inkstick, inkstone, ink brush

A Chinese writing brush () is a paintbrush used as a writing tool in Chinese calligraphy as well as in Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese which all have roots in Chinese calligraphy. They are also used in Chinese painting and other brush pain ...

, and paper in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, which are collectively called the four treasures of the study

Four Treasures of the Study is an expression used to denote the brush, ink, paper and ink stone used in Chinese calligraphy and spread into other East Asian calligraphic traditions. The name appears to originate in the time of the Souther ...

. The text mentions a kind of decorative paper called () meaning 'drifting-sand' or 'flowing-sand notepaper' that was made in what is now the region of Sichuan

Sichuan is a province in Southwestern China, occupying the Sichuan Basin and Tibetan Plateau—between the Jinsha River to the west, the Daba Mountains to the north, and the Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau to the south. Its capital city is Cheng ...

(Su 4: 7a–8a).

This paper was made by dragging a piece of paper through a fermented flour paste mixed with various colors, creating a free and irregular design. A second type was made with a paste prepared from honey locust pods, mixed with croton oil

Croton oil (''Crotonis oleum'') is an oil prepared from the seeds of '' Croton tiglium'', a tree belonging to the order Euphorbiales and family Euphorbiaceae, and native or cultivated in India and the Malay Archipelago. Small doses taken interna ...

, and thinned with water. Presumably, both black and colored inks were employed. Ginger

Ginger (''Zingiber officinale'') is a flowering plant whose rhizome, ginger root or ginger, is widely used as a spice and a folk medicine. It is an herbaceous perennial that grows annual pseudostems (false stems made of the rolled bases of l ...

, possibly in the form of an oil or extract, was used to disperse the colors, or “scatter” them, according to the interpretation given by T.H. Tsien. The colors were said to gather together when a hair-brush was beaten over the design, as dandruff

Dandruff is a skin condition of the scalp. Symptoms include flaking and sometimes mild itchiness. It can result in social or self-esteem problems. A more severe form of the condition, which includes inflammation of the skin, is known as s ...

particles was applied to the design by beating a hairbrush over top. The finished designs, which were thought to resemble human figures, clouds, or flying birds, were then transferred to the surface of a sheet of paper. An example of paper decorated with floating ink has never been found in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

. Whether or not the above methods employed floating colors remains to be determined (Tsien 94–5).

Su Yijian was an Imperial scholar-official

The scholar-officials, also known as literati, scholar-gentlemen or scholar-bureaucrats (), were government officials and prestigious scholars in Chinese society, forming a distinct social class.

Scholar-officials were politicians and governmen ...

and served as the chief of the Hanlin Academy

The Hanlin Academy was an academic and administrative institution of higher learning founded in the 8th century Tang China by Emperor Xuanzong in Chang'an. It has also been translated as "College of Literature" and "Academy of the Forest of Pen ...

from about 985–993 CE. He compiled the work from a wide variety of earlier sources and was familiar with the subject, given his profession. Yet it is important to note that it is uncertain how personally acquainted he was with the various methods for making decorative papers that he compiled. He most likely reported information given to him, without having a full understanding of the methods used. His original sources may have predated him by several centuries. Not only is it necessary to identify the original source to attribute a firm date for the information, but also the account remains uncorroborated due to a lack of any surviving physical evidence of marbling in Chinese manuscripts.

In contrast, , which means 'floating ink' in Japanese, appears to be the earliest form of marbling during the 12th-century Sanjuurokuninshuu , located in Nishihonganji , Kyoto. Author Einen Miura states that the oldest reference to papers are in the ''waka'' poems of Shigeharu, (825–880 CE), a son of the famed Heian-era poet Narihira (Muira 14) in the

In contrast, , which means 'floating ink' in Japanese, appears to be the earliest form of marbling during the 12th-century Sanjuurokuninshuu , located in Nishihonganji , Kyoto. Author Einen Miura states that the oldest reference to papers are in the ''waka'' poems of Shigeharu, (825–880 CE), a son of the famed Heian-era poet Narihira (Muira 14) in the Kokin Wakashū

The , commonly abbreviated as , is an early anthology of the '' waka'' form of Japanese poetry, dating from the Heian period. An imperial anthology, it was conceived by Emperor Uda () and published by order of his son Emperor Daigo () in abou ...

, but the verse has not been identified and even if found, it may be spurious. Various claims have been made regarding the origins of . Some think that may have derived from an early form of ink divination (encromancy). Another theory is that the process may have derived from a form of popular entertainment at the time, in which a freshly painted Sumi painting was immersed into water, and the ink slowly dispersed from the paper and rose to the surface, forming curious designs, but no physical evidence supporting these allegations has ever been identified.

According to legend, Jizemon Hiroba is credited as the inventor of . It is said that he felt divinely inspired to make paper after he offered spiritual devotions at the Kasuga Shrine

is a Shinto shrine in Nara, Nara Prefecture, Japan. It is the shrine of the Fujiwara family, established in 768 CE and rebuilt several times over the centuries. The interior is famous for its many bronze lanterns, as well as the many stone la ...

in Nara Prefecture

is a Prefectures of Japan, prefecture of Japan located in the Kansai region of Honshu. Nara Prefecture has a population of 1,321,805 and has a geographic area of . Nara Prefecture borders Kyoto Prefecture to the north, Osaka Prefecture to the ...

. He then wandered the country looking for the best water with which to make his papers. He arrived in Echizen, Fukui Prefecture

is a Prefectures of Japan, prefecture of Japan located in the Chūbu region of Honshū. Fukui Prefecture has a population of 737,229 (1 January 2025) and has a geographic area of 4,190 Square kilometre, km2 (1,617 sq mi). Fukui Prefecture border ...

where he found the water especially conducive to making . He settled there, and his family carried on with the tradition to this day. The Hiroba family claims to have made this form of marbled paper since 1151 CE for 55 generations (Narita, 14).

History in the Islamic world

The method of floating colors on the surface of

The method of floating colors on the surface of mucilaginous

Mucilage is a thick gluey substance produced by nearly all plants and some microorganisms. These microorganisms include protists which use it for their locomotion, with the direction of their movement always opposite to that of the secretion of ...

sizing

Sizing or size is a substance that is applied to, or incorporated into, other materials—especially papers and textiles—to act as a protective filler or glaze. Sizing is used in papermaking and textile manufacturing to change the absorption ...

is thought to have emerged in the regions of Greater Iran

Greater Iran or Greater Persia ( ), also called the Iranosphere or the Persosphere, is an expression that denotes a wide socio-cultural region comprising parts of West Asia, the South Caucasus, Central Asia, South Asia, and East Asia (specifica ...

and Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

by the late 15th century. It may have first appeared during the end of the Timurid dynasty

The Timurid dynasty, self-designated as Gurkani (), was the ruling dynasty of the Timurid Empire (1370–1507). It was a Sunni Islam, Sunni Muslim dynasty or Barlās clan of Turco-Mongol originB.F. Manz, ''"Tīmūr Lang"'', in Encyclopaedia of I ...

, whose final capital was in the city of Herat

Herāt (; Dari/Pashto: هرات) is an oasis city and the third-largest city in Afghanistan. In 2020, it had an estimated population of 574,276, and serves as the capital of Herat Province, situated south of the Paropamisus Mountains (''Se ...

, located in Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. It is bordered by Pakistan to the Durand Line, east and south, Iran to the Afghanistan–Iran borde ...

today. Other sources suggest it emerged during the subsequent Shaybanid dynasty, in the cities of Samarqand

Samarkand ( ; Uzbek and Tajik: Самарқанд / Samarqand, ) is a city in southeastern Uzbekistan and among the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Central Asia. Samarkand is the capital of the Samarkand Region and a district-level ...

or Bukhara

Bukhara ( ) is the List of cities in Uzbekistan, seventh-largest city in Uzbekistan by population, with 280,187 residents . It is the capital of Bukhara Region.

People have inhabited the region around Bukhara for at least five millennia, and t ...

, in what is now modern Uzbekistan

, image_flag = Flag of Uzbekistan.svg

, image_coat = Emblem of Uzbekistan.svg

, symbol_type = Emblem of Uzbekistan, Emblem

, national_anthem = "State Anthem of Uzbekistan, State Anthem of the Republ ...

. Whether or not this method was somehow related to earlier Chinese or Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

ese methods mentioned above has never been concretely proven.

Several Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

historical accounts refer to () , often shortened to (). Annemarie Schimmel translated this term as 'clouded paper' in English. While Sami Frashëri claimed in his Kamus-ı Türki, that the term was "more properly derived from the Chagatai word " (); however, he did not reference any source to support this assertion. In contrast, most historical Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

, Turkish, and Urdu

Urdu (; , , ) is an Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan language spoken chiefly in South Asia. It is the Languages of Pakistan, national language and ''lingua franca'' of Pakistan. In India, it is an Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of Indi ...

texts refer to the paper as alone. Today in Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

, the art is commonly known as , a cognate

In historical linguistics, cognates or lexical cognates are sets of words that have been inherited in direct descent from an etymological ancestor in a common parent language.

Because language change can have radical effects on both the s ...

of the term first documented in the 19th century. In Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

, many now employ a variant term, (), meaning 'cloud and wind' for a modern method made with oil colors.

The art first emerged and evolved during the long 16th century in Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

and Transoxiana

Transoxiana or Transoxania (, now called the Amu Darya) is the Latin name for the region and civilization located in lower Central Asia roughly corresponding to eastern Uzbekistan, western Tajikistan, parts of southern Kazakhstan, parts of Tu ...

then spread to the Ottoman Turkey

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Central Euro ...

, as well as Mughal and the Deccan Sultanates

The Deccan sultanates is a historiographical term referring to five late medieval to early modern Persianate Indian Muslim kingdoms on the Deccan Plateau between the Krishna River and the Vindhya Range. They were created from the disintegrati ...

in India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

. Within these regions, various methods emerged in which colors were made to float on the surface of a bath of viscous liquid mucilage or ''size

Size in general is the Magnitude (mathematics), magnitude or dimensions of a thing. More specifically, ''geometrical size'' (or ''spatial size'') can refer to three geometrical measures: length, area, or volume. Length can be generalized ...

'', made from various plants including fenugreek

Fenugreek (; ''Trigonella foenum-graecum'') is an annual plant in the family Fabaceae, with leaves consisting of three small Glossary_of_leaf_morphology#Leaf_and_leaflet_shapes, obovate to oblong leaflets. It is cultivated worldwide as a semiar ...

seed, onion

An onion (''Allium cepa'' , from Latin ), also known as the bulb onion or common onion, is a vegetable that is the most widely cultivated species of the genus '' Allium''. The shallot is a botanical variety of the onion which was classifie ...

, gum tragacanth (''astragalus

Astragalus may refer to:

* ''Astragalus'' (plant), a large genus of herbs and small shrubs

*Astragalus (bone)

The talus (; Latin for ankle or ankle bone; : tali), talus bone, astragalus (), or ankle bone is one of the group of foot bones known ...

'') and ''salep

Salep, also spelled sahlep salepi or sahlab,; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; is a flour made from the tubers of the orchid genus ''Orchis'' (including species '' Orchis mascula'' and ''Orchis militaris''). These tubers contain a nutritious, starchy polysacc ...

'' (the roots of Orchis mascula), among others.

A pair of leaves purported to be the earliest examples of this paper, preserved in the Kronos collection, bears rudimentary droplet-motifs. One of the sheets bears an accession notation on the reverse stating "These abris are rare" () and adds that it was "among the gifts from Iran" to the royal library of Ghiyath Shah, the ruler of the Malwa Sultanate

The Malwa Sultanate was a late medieval kingdom in the Malwa, Malwa region, covering the present day Indian states of Madhya Pradesh and south-eastern Rajasthan from 1401 to 1562. It was founded by Dilawar Khan, who following Timur's invasion ...

, dated Hijri year

The Hijri year () or era () is the era used in the Islamic lunar calendar. It begins its count from the Islamic New Year in which Muhammad and his followers migrated from Mecca to Yathrib (now Medina) in 622 CE. This event, known as the Hij ...

1 Dhu al-Hijjah

Dhu al-Hijjah (also Dhu al-Hijja ) is the twelfth and final month in the Islamic calendar. Being one of the four sacred months during which war is forbidden, it is the month in which the '' Ḥajj'' () takes place as well as Eid al-Adha ().

T ...

901/11 August 1496 of the Common Era

Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE) are year notations for the Gregorian calendar (and its predecessor, the Julian calendar), the world's most widely used calendar era. Common Era and Before the Common Era are alternatives to the ...

.

Approximately a century later, a technically advanced approach using finely prepared mineral and organic pigments and combs to manipulate the floating colors resulted in comparatively elaborate, intricate, and mesmerizing overall designs. Both literary and physical evidence suggests that before 1600, a Safavid

The Guarded Domains of Iran, commonly called Safavid Iran, Safavid Persia or the Safavid Empire, was one of the largest and longest-lasting Iranian empires. It was ruled from 1501 to 1736 by the Safavid dynasty. It is often considered the begi ...

-era émigré to India named Muḥammad Ṭāhir developed many of these innovations. Later that century, Indian marblers combined the technique with stencil

Stencilling produces an image or pattern on a surface by applying pigment to a surface through an intermediate object, with designed holes in the intermediate object. The holes allow the pigment to reach only some parts of the surface creatin ...

and resist

A resist, used in many areas of manufacturing and art, is something that is added to parts of an object to create a pattern by protecting these parts from being affected by a subsequent stage in the process. Often the resist is then removed.

For ...

masking methods to create miniature paintings, attributed to the Deccan sultanates

The Deccan sultanates is a historiographical term referring to five late medieval to early modern Persianate Indian Muslim kingdoms on the Deccan Plateau between the Krishna River and the Vindhya Range. They were created from the disintegrati ...

and especially the city of Bijapur

Bijapur (officially Vijayapura) is the district headquarters of Bijapur district of the Karnataka state of India. It is also the headquarters for Bijapur Taluk. Bijapur city is well known for its historical monuments of architectural importa ...

in particular, during the Adil Shahi

The Sultanate of Bijapur was an early modern kingdom in the western Deccan and South India, ruled by the Muslim Adil Shahi (or Adilshahi) dynasty. Bijapur had been a '' taraf'' (province) of the Bahmani Kingdom prior to its independence in 14 ...

dynasty in the 17th century.

The earliest examples of Ottoman marbled paper may be the margins attached to a cut paper découpage manuscript of the () by the poet Arifi (popularly known as the Ball and Polo-stick' completed by Mehmed bin Gazanfer in 1539–40. Recipes ascribed to one early master by the name of Shebek, appear posthumously in the earliest, anonymously compiled Ottoman miscellany

A miscellany (, ) is a collection of various pieces of writing by different authors. Meaning a mixture, medley, or assortment, a miscellany can include pieces on many subjects and in a variety of different forms. In contrast to anthologies, w ...

on the art known as the (, 'An Arrangement of a Treatise on Ebrî'), dated on the basis of internal evidence to after 1615. Many in Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

attribute another famous 18th-century master Hatip Mehmed Efendi (died 1773) with developing motif and perhaps early floral designs and refer to them as "Hatip" designs, although similar evidence also survives from Iran and India, which await further study.

The current Turkish tradition of dates to the mid-19th century, with a series of masters associated with a branch of the Naqshbandi

Naqshbandi (Persian: نقشبندیه) is a major Sufi order within Sunni Islam, named after its 14th-century founder, Baha' al-Din Naqshband. Practitioners, known as Naqshbandis, trace their spiritual lineage (silsila) directly to the Prophet ...

Sufi

Sufism ( or ) is a mysticism, mystic body of religious practice found within Islam which is characterized by a focus on Islamic Tazkiyah, purification, spirituality, ritualism, and Asceticism#Islam, asceticism.

Practitioners of Sufism are r ...

order based at what is known as the (Lodge of the Uzbeks), located in Sultantepe, near Üsküdar

Üsküdar () is a municipality and district of Istanbul Province, Turkey. Its area is 35 km2, and its population is 524,452 (2022). It is a large and densely populated district on the Anatolian (Asian) shore of the Bosphorus. It is border ...

. The founder of this line, Sadık Effendi (died 1846) allegedly first learned the art in Bukhara

Bukhara ( ) is the List of cities in Uzbekistan, seventh-largest city in Uzbekistan by population, with 280,187 residents . It is the capital of Bukhara Region.

People have inhabited the region around Bukhara for at least five millennia, and t ...

and brought it to Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

, then taught it to his sons Edhem and Salıh. Based upon this later practice, many Turkish marblers assert that Sufis practiced the art for centuries; however, little evidence supports this claim. Sadık's son Edhem Effendi (died 1904) manufactured papers as a kind of cottage industry

The putting-out system is a means of subcontracting work, like a tailor. Historically, it was also known as the workshop system and the domestic system. In putting-out, work is contracted by a central agent to subcontractors who complete the p ...

for the , to supply Istanbul's burgeoning printing industry with the paper, purportedly tied into bundles and sold by weight. Many of his papers feature designs made with turpentine, analogous to what English-speaking marblers refer to as the ''stormont'' pattern.

The premier student of Edhem Efendi, Necmeddin Okyay (1885–1976), first taught the art at the Fine Arts Academy in Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

. He famously innovated elaborate floral designs, in addition to '','' a method of writing traditional calligraphy using a gum arabic

Gum arabic (gum acacia, gum sudani, Senegal gum and by other names) () is a tree gum exuded by two species of '' Acacia sensu lato:'' '' Senegalia senegal,'' and '' Vachellia seyal.'' However, the term "gum arabic" does not indicate a partic ...

resist masking applied before marbling the sheet. Okyay's premier student, Mustafa Düzgünman (1920–1990), taught many contemporary marblers in Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

today. He codified the traditional repertoire of patterns, to which he only added a floral daisy design, after the manner of his teacher.

History in Europe

In the 17th century, European travelers to theMiddle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

collected examples of these papers and bound them into album amicorum

The ''album amicorum'' ('album of friends', friendship book) was an early form of the poetry book, the autograph book and the modern friendship book. It emerged during the reformation, Reformation period, during which it was popular to collect ...

, which literally means "album of friends" in Latin, and is a forerunner of the modern autograph

An autograph is a person's own handwriting or signature. The word ''autograph'' comes from Ancient Greek (, ''autós'', "self" and , ''gráphō'', "write"), and can mean more specifically: Gove, Philip B. (ed.), 1981. ''Webster's Third New Intern ...

album. Eventually, the technique for making the papers reached Europe, where they became a popular covering material not only for book covers and end-papers, but also for lining chests, drawers, and bookshelves. By the late 17th century, Europeans also started to marbled the edges of books.

The methods of marbling attracted the curiosity of intellectuals, philosophers, and scientists. Gerhard ter Brugghen published the earliest European technical account, written in Dutch, in his in Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , ; ; ) is the capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, largest city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It has a population of 933,680 in June 2024 within the city proper, 1,457,018 in the City Re ...

in 1616, while the first German account was written by Daniel Schwenter

Daniel Schwenter (Schwender) (31 January 1585 – 19 January 1636) was a German Orientalist, mathematician, inventor, poet, and librarian.

Biography

Schwenter was born in Nuremberg. He was professor of oriental languages and mathematics at ...

, published posthumously in his in 1671 (Benson, "Curious Colors", 284; Wolfe, 16). Athanasius Kircher

Athanasius Kircher (2 May 1602 – 27 November 1680) was a German Society of Jesus, Jesuit scholar and polymath who published around 40 major works of comparative religion, geology, and medicine. Kircher has been compared to fellow Jes ...

published a Latin account in '' Ars Magna Lucis et Umbræ'' in Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

in 1646, widely disseminated knowledge of the art throughout Europe. Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a prominent figure during th ...

and Jean le Rond d'Alembert

Jean-Baptiste le Rond d'Alembert ( ; ; 16 November 1717 – 29 October 1783) was a French mathematician, mechanician, physicist, philosopher, and music theorist. Until 1759 he was, together with Denis Diderot, a co-editor of the ''Encyclopé ...

published a thorough overview of the art with illustrations of marblers at work together with images of the tools of the trade in their ''Encyclopédie

, better known as ''Encyclopédie'' (), was a general encyclopedia published in France between 1751 and 1772, with later supplements, revised editions, and translations. It had many writers, known as the Encyclopédistes. It was edited by Denis ...

''.

Elena Laura Jakobi is responsible for a conceptual history study of the terms and variants used to describe marbled paper between 1550 and 1800. The genesis, development, and differentiation of the terms are documented in German, Dutch, French, Italian, and Latin using 109 written sources.

In 1695, the Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the Kingdom of England, English Government's banker and debt manager, and still one ...

employed partially marbled papers banknote

A banknote or bank notealso called a bill (North American English) or simply a noteis a type of paper money that is made and distributed ("issued") by a bank of issue, payable to the bearer on demand. Banknotes were originally issued by commerc ...

s for several weeks until it discovered that William Chaloner had successfully forged similar notes (Benson, "Curious Colors", 289–294). Nevertheless, the Bank continued to issued partially marbled cheque

A cheque (or check in American English) is a document that orders a bank, building society, or credit union, to pay a specific amount of money from a person's account to the person in whose name the cheque has been issued. The person writing ...

s until the 1810s (Benson, "Curious Colors", 301–302). In 1731, English marbler Samuel Pope obtained a patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an sufficiency of disclosure, enabling discl ...

for security marbling, claiming that he invented the process, then sued his competitors for infringement; however, those he accused exposed him for patent fraud (Benson, "Curious Colors", 294–301). Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

obtained English marbled security papers employed for printing Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislature, legislative bodies, with some executive function, for the Thirteen Colonies of British America, Great Britain in North America, and the newly declared United States before, during, and after ...

$20 banknote in 1775, as well as promissory note

A promissory note, sometimes referred to as a note payable, is a legal instrument (more particularly, a financing instrument and a debt instrument), in which one party (the ''maker'' or ''issuer'') promises in writing to pay a determinate sum of ...

s to support the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

, threepence notes issued during the Copper Panic of 1789 The Copper Panic of 1789 was a monetary crisis of the early United States that was caused by debasement and loss of confidence in copper coins that occurred under the presidency of George Washington.

After the American Revolution, many states beg ...

, as well as his own personal cheque

A cheque (or check in American English) is a document that orders a bank, building society, or credit union, to pay a specific amount of money from a person's account to the person in whose name the cheque has been issued. The person writing ...

s (Benson, "Curious Colors", 302–307).

Nineteenth century

After English marbler Charles Woolnough published his ''The Art of Marbling'' (1853), the art production increased in the 19th century. In it, he describes how he adapted a method of marbling onto book cloth, which he exhibited at the Crystal Palace Exhibition in 1851. (Wolfe, 79) Josef Halfer, a bookbinder of German origin, who lived in Budakeszi,Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

conducted extensive experiments and devised further innovations, chiefly by adapting ''Chondrus crispus

''Chondrus crispus''—commonly called Irish moss or carrageenan moss (Irish ''carraigín'', "little rock")—is a species of red algae which grows abundantly along the rocky parts of the Atlantic coasts of Europe and North America. In its fresh ...

'' for sizing, which superseded Woolnough's methods in Europe and the US.

In the 21st century

Marblers still make marbled paper and fabric, even applying the technique to three-dimensional surfaces. Aside from continued traditional applications, artists now explore using the method as a kind of painting technique, and as an element in

Marblers still make marbled paper and fabric, even applying the technique to three-dimensional surfaces. Aside from continued traditional applications, artists now explore using the method as a kind of painting technique, and as an element in collage

Collage (, from the , "to glue" or "to stick together") is a technique of art creation, primarily used in the visual arts, but in music too, by which art results from an assembly of different forms, thus creating a new whole. (Compare with pasti ...

. In recent decades, international symposia and museum exhibitions featured the art. A marbling journal ''Ink & Gall'' sponsored the first International Marblers' Gathering held in Santa Fe, New Mexico

New Mexico is a state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States. It is one of the Mountain States of the southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. It also ...

in 1989. Active international groups can be found on social media networks such as Facebook and the International Marbling Network.

Another adaptation called body marbling has emerged at public events and festivals, applied with non-toxic, water-based neon or ultraviolet reactive paints.

Examples

Maurice Maeterlinck

Maurice Polydore Marie Bernard Maeterlinck (29 August 1862 – 6 May 1949), also known as Count/Comte Maeterlinck from 1932, was a Belgian playwright, poet, and essayist who was Flemish but wrote in French. He was awarded the 1911 Nobel Prize in ...

File:1902MarbledTheLifeOfTheBeeByMaeterlinckDetail.jpg, Frontispiece detail of The Life of the Bee

Richard J. Wolfe Collection of Paper Marbling and Allied Book Arts.

University of Chicago Library

See also

*Marbleizing

Marbleizing (also spelt marbleising) or faux marbling is the preparation and finishing of a surface to imitate the appearance of polished marble. It is typically used in buildings where the cost or weight of genuine marble would be prohibitive. F ...

* Water transfer printing

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * *External links

Decorated and Decorative Paper Collection

from the

University of Washington

The University of Washington (UW and informally U-Dub or U Dub) is a public research university in Seattle, Washington, United States. Founded in 1861, the University of Washington is one of the oldest universities on the West Coast of the Uni ...

libraries

:A database that showcases a selection of decorated and decorative papers, with dozens of pattern examples, two essays, and a bibliography

Marbled paper (archived 2019)

by Joel Silver, from Nov./Dec. 2005 issue of ''Fine Books'' magazine

Art of the Marbler

1970 film by Bedfordshire Record Office of Cockerell marbling

Ebru Art

A short video from the American Islamic College that shows artist Garip Ay perform the art of Turkish Ebru {{Authority control Paper Paper art Handicrafts