, house =

Bourbon

, father =

Louis XIII

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crow ...

, mother =

Anne of Austria

Anne of Austria (french: Anne d'Autriche, italic=no, es, Ana María Mauricia, italic=no; 22 September 1601 – 20 January 1666) was an infanta of Spain who became Queen of France as the wife of King Louis XIII from their marriage in 1615 unt ...

, birth_date =

, birth_place =

Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye

The Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye () is a former royal palace in the commune of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, in the ''département'' of Yvelines, about 19 km west of Paris, France. Today, it houses the '' musée d'Archéologie nationale'' (N ...

,

Saint-Germain-en-Laye,

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, death_date =

, death_place =

Palace of Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, u ...

,

Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, ...

, France

, burial_date = 9 September 1715

, burial_place =

Basilica of Saint-Denis

, religion =

Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

(

Gallican Rite)

, signature = Louis XIV Signature.svg

Louis XIV (Louis Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was

King of France

France was ruled by monarchs from the establishment of the Kingdom of West Francia in 843 until the end of the Second French Empire in 1870, with several interruptions.

Classical French historiography usually regards Clovis I () as the fir ...

from 14 May 1643 until his death in 1715. His reign of 72 years and 110 days is the

longest of any sovereign in history whose date is verifiable. Although Louis XIV's France was emblematic of the

age of absolutism in Europe, the King surrounded himself with a variety of significant political, military, and cultural figures, such as

Bossuet Bossuet is a French surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet

Jacques-Bénigne Lignel Bossuet (; 27 September 1627 – 12 April 1704) was a French bishop and theologian, renowned for his sermons and other addr ...

,

Colbert,

Le Brun,

Le Nôtre,

Lully,

Mazarin,

Molière

Jean-Baptiste Poquelin (, ; 15 January 1622 (baptised) – 17 February 1673), known by his stage name Molière (, , ), was a French playwright, actor, and poet, widely regarded as one of the greatest writers in the French language and world ...

,

Racine

Jean-Baptiste Racine ( , ) (; 22 December 163921 April 1699) was a French dramatist, one of the three great playwrights of 17th-century France, along with Molière and Corneille as well as an important literary figure in the Western traditi ...

,

Turenne, and

Vauban.

Louis began his personal rule of France in 1661, after the death of his chief minister, the

Cardinal Mazarin.

An adherent of the concept of the

divine right of kings

In European Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representin ...

, Louis continued his predecessors' work of creating a

centralised state governed from the capital. He sought to eliminate the remnants of

feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structu ...

persisting in parts of France; by compelling many members of the

nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The character ...

to inhabit his lavish

Palace of Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, u ...

, he succeeded in pacifying the aristocracy, many members of which had participated in

the Fronde during his minority. By these means he became one of the most powerful French monarchs and consolidated a system of

absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constituti ...

in France that endured until the

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

. Louis also enforced uniformity of religion under the

Gallican Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

. His

revocation of the

Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes () was signed in April 1598 by King Henry IV and granted the Calvinist Protestants of France, also known as Huguenots, substantial rights in the nation, which was in essence completely Catholic. In the edict, Henry aimed pr ...

abolished the rights of the

Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

Protestant minority and subjected them to a wave of

dragonnades

The ''Dragonnades'' were a French government policy instituted by King Louis XIV in 1681 to intimidate Huguenot (Protestant) families into converting to Catholicism. This involved the billeting of ill-disciplined dragoons in Protestant household ...

, effectively forcing Huguenots to emigrate or convert, as well as virtually destroying the French Protestant community.

During Louis's long reign, France emerged as the leading European power and regularly asserted its military strength. A

conflict with Spain marked his entire childhood, while during his reign, the kingdom took part in three major continental conflicts, each against powerful foreign alliances: the

Franco-Dutch War

The Franco-Dutch War, also known as the Dutch War (french: Guerre de Hollande; nl, Hollandse Oorlog), was fought between France and the Dutch Republic, supported by its allies the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, Brandenburg-Prussia and Denmark-Nor ...

, the

Nine Years' War

The Nine Years' War (1688–1697), often called the War of the Grand Alliance or the War of the League of Augsburg, was a conflict between Kingdom of France, France and a European coalition which mainly included the Holy Roman Empire (led by t ...

, and the

War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

. In addition, France also contested shorter wars, such as the

War of Devolution

In the 1667 to 1668 War of Devolution (, ), France occupied large parts of the Spanish Netherlands and Franche-Comté, both then provinces of the Holy Roman Empire (and properties of the King of Spain). The name derives from an obscure law k ...

and the

War of the Reunions. Warfare defined Louis's foreign policy and his personality shaped his approach. Impelled by "a mix of commerce, revenge, and pique", he sensed that war was the ideal way to enhance his glory. In peacetime, he concentrated on preparing for the next war. He taught his diplomats that their job was to create tactical and strategic advantages for the French military. Upon his death in 1715, Louis XIV left his great-grandson and successor,

Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reache ...

, a powerful kingdom, albeit in major debt after the thirteen-year-long War of the Spanish Succession.

Significant achievements during his reign which would go on to have a wide influence on the

early modern period well into the

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

and until today, include the construction of the

Canal du Midi

The Canal du Midi (; ) is a long canal in Southern France (french: le Midi). Originally named the ''Canal royal en Languedoc'' (Royal Canal in Languedoc) and renamed by French revolutionaries to ''Canal du Midi'' in 1789, the canal is conside ...

, the patronage of

artists

An artist is a person engaged in an activity related to creating art, practicing the arts, or demonstrating an art. The common usage in both everyday speech and academic discourse refers to a practitioner in the visual arts only. However, the ...

, and the founding of the

French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (French: ''Académie des sciences'') is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French scientific research. It was at ...

.

Early years

Louis XIV was born on 5 September 1638 in the

Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye

The Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye () is a former royal palace in the commune of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, in the ''département'' of Yvelines, about 19 km west of Paris, France. Today, it houses the '' musée d'Archéologie nationale'' (N ...

, to

Louis XIII

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crow ...

and

Anne of Austria

Anne of Austria (french: Anne d'Autriche, italic=no, es, Ana María Mauricia, italic=no; 22 September 1601 – 20 January 1666) was an infanta of Spain who became Queen of France as the wife of King Louis XIII from their marriage in 1615 unt ...

. He was named Louis Dieudonné (Louis the God-given) and bore the traditional title of French

heirs apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

: ''

Dauphin''. At the time of his birth, his parents had been married for 23 years. His mother had experienced four

stillbirth

Stillbirth is typically defined as fetal death at or after 20 or 28 weeks of pregnancy, depending on the source. It results in a baby born without signs of life. A stillbirth can result in the feeling of guilt or grief in the mother. The term ...

s between 1619 and 1631. Leading contemporaries thus regarded him as a divine gift and his birth a miracle of God.

Louis's relationship with his mother was uncommonly affectionate for the time. Contemporaries and eyewitnesses claimed that the Queen would spend all her time with Louis. Both were greatly interested in food and theatre, and it is highly likely that Louis developed these interests through his close relationship with his mother. This long-lasting and loving relationship can be evidenced by excerpts in Louis' journal entries, such as:

"Nature was responsible for the first knots which tied me to my mother. But attachments formed later by shared qualities of the spirit are far more difficult to break than those formed merely by blood."

It was his mother who gave Louis his belief in the absolute and divine power of his monarchical rule.

During his childhood, he was taken care of by the governesses

Françoise de Lansac and

Marie-Catherine de Senecey

Marie-Catherine de Senecey, née ''de La Rochefoucauld-Randan'' (1588–1677) was a French courtier. She served as '' Première dame d'honneur'' to the queen of France, Anne of Austria, from 1626 until 1638, and royal governess to king Louis XIV o ...

. In 1646,

Nicolas V de Villeroy became the young king's tutor. Louis XIV became friends with Villeroy's young children, particularly

François de Villeroy, and divided his time between the

Palais-Royal

The Palais-Royal () is a former royal palace located in the 1st arrondissement of Paris, France. The screened entrance court faces the Place du Palais-Royal, opposite the Louvre. Originally called the Palais-Cardinal, it was built for Cardinal R ...

and the nearby Hotel de Villeroy.

Minority and the ''Fronde''

Accession

Sensing imminent death, Louis XIII decided to put his affairs in order in the spring of 1643, when Louis XIV was four years old. In defiance of custom, which would have made Queen Anne the sole

regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

of France, the king decreed that a regency council would rule on his son's behalf. His lack of faith in Queen Anne's political abilities was his primary rationale. He did, however, make the concession of appointing her head of the council.

Louis XIII died on 14 May 1643, and on 18 May, Queen Anne had her husband's will annulled by the ''

Parlement de Paris'' (a judicial body comprising mostly nobles and high clergymen). This action abolished the regency council and made Anne the sole Regent of France. Anne exiled some of her husband's ministers (Chavigny, Bouthilier), and she nominated Brienne as her minister of foreign affairs.

Anne kept the direction of religious policy strongly in her hand until 1661; her most important political decisions were to nominate

Cardinal Mazarin as her chief minister and the continuation of her late husband's and

Cardinal Richelieu

Armand Jean du Plessis, Duke of Richelieu (; 9 September 1585 – 4 December 1642), known as Cardinal Richelieu, was a French clergyman and statesman. He was also known as ''l'Éminence rouge'', or "the Red Eminence", a term derived from the ...

's policy, despite their persecution of her, for the sake of her son. Anne wanted to give her son absolute authority and a victorious kingdom. Her rationales for choosing Mazarin were mainly his ability and his total dependence on her, at least until 1653 when she was no longer regent. Anne protected Mazarin by arresting and exiling her followers who conspired against him in 1643: the

Duke of Beaufort

Duke of Beaufort (), a title in the Peerage of England, was created by Charles II in 1682 for Henry Somerset, 3rd Marquess of Worcester, a descendant of Charles Somerset, 1st Earl of Worcester, legitimised son of Henry Beaufort, 3rd Duke of S ...

and

Marie de Rohan. She left the direction of the daily administration of policy to Cardinal Mazarin.

The best example of Anne's statesmanship and the partial change in her heart towards her native Spain is seen in her keeping of one of Richelieu's men, the Chancellor of France

Pierre Séguier, in his post. Séguier was the person who had interrogated Anne in 1637, treating her like a "common criminal" as she described her treatment following the discovery that she was giving military secrets and information to Spain. Anne was virtually under house arrest for a number of years during her husband's rule. By keeping him in his post, Anne was giving a sign that the interests of France and her son Louis were the guiding spirit of all her political and legal actions. Though not necessarily opposed to Spain, she sought to end the war with a French victory, in order to establish a lasting peace between the Catholic nations.

The Queen also gave a partial Catholic orientation to French foreign policy. This was felt by the Netherlands, France's Protestant ally, which negotiated a separate peace with Spain in 1648.

In 1648, Anne and Mazarin successfully negotiated the

Peace of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia (german: Westfälischer Friede, ) is the collective name for two peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought pe ...

, which ended the

Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of batt ...

. Its terms ensured

Dutch independence from

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, awarded some autonomy to the various German princes of the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

, and granted Sweden seats on the

Imperial Diet and territories to control the mouths of the

Oder

The Oder ( , ; Czech, Lower Sorbian and ; ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river in total length and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows ...

,

Elbe

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Re ...

, and

Weser

The Weser () is a river of Lower Saxony in north-west Germany. It begins at Hannoversch Münden through the confluence of the Werra and Fulda. It passes through the Hanseatic city of Bremen. Its mouth is further north against the ports o ...

rivers. France, however, profited most from the settlement. Austria, ruled by the

Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

Emperor

Ferdinand III, ceded all Habsburg lands and claims in

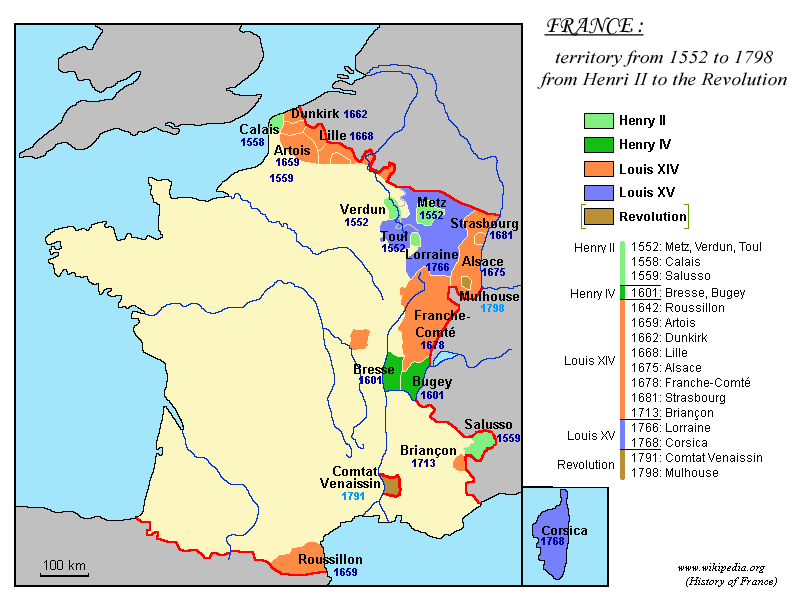

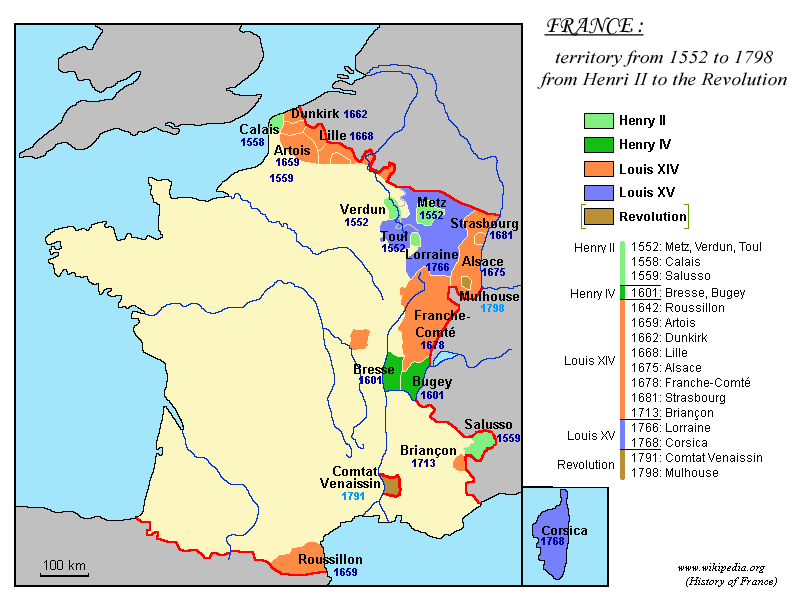

Alsace

Alsace (, ; ; Low Alemannic German/ gsw-FR, Elsàss ; german: Elsass ; la, Alsatia) is a cultural region and a territorial collectivity in eastern France, on the west bank of the upper Rhine next to Germany and Switzerland. In 2020, it had ...

to France and acknowledged her ''de facto'' sovereignty over the

Three Bishoprics of

Metz

Metz ( , , lat, Divodurum Mediomatricorum, then ) is a city in northeast France located at the confluence of the Moselle and the Seille rivers. Metz is the prefecture of the Moselle department and the seat of the parliament of the Grand ...

,

Verdun

Verdun (, , , ; official name before 1970 ''Verdun-sur-Meuse'') is a large city in the Meuse department in Grand Est, northeastern France. It is an arrondissement of the department.

Verdun is the biggest city in Meuse, although the capital ...

, and

Toul

Toul () is a commune in the Meurthe-et-Moselle department in north-eastern France.

It is a sub-prefecture of the department.

Geography

Toul is between Commercy and Nancy, and the river Moselle and Canal de la Marne au Rhin.

Climate

Toul ...

. Moreover, eager to emancipate themselves from Habsburg domination, petty German states sought French protection. This anticipated the formation of the 1658

League of the Rhine, leading to the further diminution of Imperial power.

Early acts

As the Thirty Years' War came to an end, a civil war known as

the Fronde (after the slings used to smash windows) erupted in France. It effectively checked France's ability to exploit the Peace of Westphalia. Anne and Mazarin had largely pursued the policies of

Cardinal Richelieu

Armand Jean du Plessis, Duke of Richelieu (; 9 September 1585 – 4 December 1642), known as Cardinal Richelieu, was a French clergyman and statesman. He was also known as ''l'Éminence rouge'', or "the Red Eminence", a term derived from the ...

, augmenting the Crown's power at the expense of the nobility and the '. Anne interfered much more in internal policy than foreign affairs; she was a very proud queen who insisted on the divine rights of the King of France.

All this led her to advocate a forceful policy in all matters relating to the King's authority, in a manner that was much more radical than the one proposed by Mazarin. The Cardinal depended totally on Anne's support and had to use all his influence on the Queen to temper some of her radical actions. Anne imprisoned any aristocrat or member of parliament who challenged her will; her main aim was to transfer to her son an absolute authority in the matters of finance and justice. One of the leaders of the Parlement of Paris, whom she had jailed, died in prison.

The ', political heirs of the disaffected feudal aristocracy, sought to protect their traditional feudal privileges from the increasingly centralized royal government. Furthermore, they believed their traditional influence and authority was being usurped by the recently ennobled bureaucrats (the ', or "nobility of the robe"), who administered the kingdom and on whom the monarchy increasingly began to rely. This belief intensified the nobles' resentment.

In 1648, Anne and Mazarin attempted to tax members of the '. The members refused to comply and ordered all of the king's earlier financial edicts burned. Buoyed by the victory of (later known as ') at the

Battle of Lens

The Battle of Lens (20 August 1648) was a French victory under Louis II de Bourbon, Prince de Condé against the Spanish army under Archduke Leopold Wilhelm in the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648). It was the last major battle of the war and a ...

, Mazarin, on Queen Anne's insistence, arrested certain members in a show of force. The most important arrest, from Anne's point of view, concerned

Pierre Broussel, one of the most important leaders in the '.

People in France were complaining about the expansion of royal authority, the high rate of taxation, and the reduction of the authority of the Parlement de Paris and other regional representative entities. Paris erupted in rioting as a result, and Anne was forced, under intense pressure, to free Broussel. Moreover, on the night of 9–10 February 1651, when Louis was twelve, a mob of angry Parisians broke into the royal palace and demanded to see their king. Led into the royal bed-chamber, they gazed upon Louis, who was feigning sleep, were appeased, and then quietly departed. The threat to the royal family prompted Anne to flee Paris with the king and his courtiers.

Shortly thereafter, the conclusion of the

Peace of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia (german: Westfälischer Friede, ) is the collective name for two peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought pe ...

allowed Condé's army to return to aid Louis and his court. Condé's family was close to Anne at that time, and he agreed to help her attempt to restore the king's authority. The queen's army, headed by Condé, attacked the rebels in Paris; the rebels were under the political control of Anne's old friend

Marie de Rohan. Beaufort, who had escaped from the prison where Anne had incarcerated him five years before, was the military leader in Paris, under the nominal control of Conti. After a few battles, a political compromise was reached; the

Peace of Rueil

The Peace of Rueil (french: Paix de Rueil, or ), signed 11 March 1649, signalled an end to the opening episodes of the Fronde (a period of civil war in the Kingdom of France) after little blood had been shed. The articles ended all hostilitie ...

was signed, and the court returned to Paris.

Unfortunately for Anne, her partial victory depended on Condé, who wanted to control the queen and destroy Mazarin's influence. It was Condé's sister who pushed him to turn against the queen. After striking a deal with her old friend Marie de Rohan, who was able to impose the nomination of as minister of justice, Anne arrested Condé, his brother

Armand de Bourbon, Prince of Conti, and the husband of their sister Anne Genevieve de Bourbon,

duchess of Longueville

Countess of Longueville

House of Orléans-Longueville, 1443–1505

Duchess of Longueville

House of Orléans-Longueville, 1505–1694

{, width=95% class="wikitable"

!width = "8%" , Picture

!width = "10%" , Name

!width = "9%" , Fat ...

. This situation did not last long, and Mazarin's unpopularity led to the creation of a coalition headed mainly by Marie de Rohan and the duchess of Longueville. This aristocratic coalition was strong enough to liberate the princes, exile Mazarin, and impose a condition of virtual house arrest on Queen Anne.

All these events were witnessed by Louis and largely explained his later distrust of Paris and the higher aristocracy. "In one sense, Louis' childhood came to an end with the outbreak of the Fronde. It was not only that life became insecure and unpleasant – a fate meted out to many children in all ages – but that Louis had to be taken into the confidence of his mother and Mazarin on political and military matters of which he could have no deep understanding". "The family home became at times a near-prison when Paris had to be abandoned, not in carefree outings to other chateaux but in humiliating flights". The royal family was driven out of Paris twice in this manner, and at one point Louis XIV and Anne were held under virtual arrest in the royal palace in Paris. The Fronde years planted in Louis a hatred of Paris and a consequent determination to move out of the ancient capital as soon as possible, never to return.

Just as the first ' (the ' of 1648–1649) ended, a second one (the ' of 1650–1653) began. Unlike that which preceded it, tales of sordid intrigue and half-hearted warfare characterized this second phase of upper-class insurrection. To the aristocracy, this rebellion represented a protest for the reversal of their political demotion from

vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerai ...

s to

courtiers. It was headed by the highest-ranking French nobles, among them Louis' uncle

Gaston, Duke of Orléans

'' Monsieur'' Gaston, Duke of Orléans (Gaston Jean Baptiste; 24 April 1608 – 2 February 1660), was the third son of King Henry IV of France and his second wife, Marie de' Medici. As a son of the king, he was born a '' Fils de France''. He lat ...

and first cousin

Anne Marie Louise d'Orléans, Duchess of Montpensier, known as ';

Princes of the Blood such as Condé, his brother

Armand de Bourbon, Prince of Conti, and their sister the

Duchess of Longueville

Countess of Longueville

House of Orléans-Longueville, 1443–1505

Duchess of Longueville

House of Orléans-Longueville, 1505–1694

{, width=95% class="wikitable"

!width = "8%" , Picture

!width = "10%" , Name

!width = "9%" , Fat ...

; dukes of

legitimised royal descent, such as

Henri, Duke of Longueville, and

François, Duke of Beaufort; so-called "

foreign princes" such as

Frédéric Maurice, Duke of Bouillon, his brother

Marshal

Marshal is a term used in several official titles in various branches of society. As marshals became trusted members of the courts of Medieval Europe, the title grew in reputation. During the last few centuries, it has been used for elevated o ...

Turenne, and

Marie de Rohan, Duchess of Chevreuse; and

scions of France's oldest families, such as

François de La Rochefoucauld.

Queen Anne played the most important role in defeating the Fronde because she wanted to transfer absolute authority to her son. In addition, most of the princes refused to deal with Mazarin, who went into exile for a number of years. The ' claimed to act on Louis' behalf, and in his real interest, against his mother and Mazarin.

Queen Anne had a very close relationship with the Cardinal, and many observers believed that Mazarin became Louis XIV's stepfather by a secret marriage to Queen Anne. However, Louis' coming-of-age and subsequent

coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the presentation of o ...

deprived them of the ' pretext for revolt. The ' thus gradually lost steam and ended in 1653, when Mazarin returned triumphantly from exile. From that time until his death, Mazarin was in charge of foreign and financial policy without the daily supervision of Anne, who was no longer regent.

During this period, Louis fell in love with Mazarin's niece

Marie Mancini, but Anne and Mazarin ended the king's infatuation by sending Mancini away from court to be married in Italy. While Mazarin might have been tempted for a short period of time to marry his niece to the King of France, Queen Anne was absolutely against this; she wanted to marry her son to the daughter of her brother,

Philip IV of Spain

Philip IV ( es, Felipe, pt, Filipe; 8 April 160517 September 1665), also called the Planet King (Spanish: ''Rey Planeta''), was King of Spain from 1621 to his death and (as Philip III) King of Portugal from 1621 to 1640. Philip is remembered ...

, for both dynastic and political reasons. Mazarin soon supported the Queen's position because he knew that her support for his power and his foreign policy depended on making peace with Spain from a strong position and on the Spanish marriage. Additionally, Mazarin's relations with Marie Mancini were not good, and he did not trust her to support his position. All of Louis' tears and his supplications to his mother did not make her change her mind. The Spanish marriage would be very important both for its role in ending the war between France and Spain, because many of the claims and objectives of Louis' foreign policy for the next 50 years would be based upon this marriage, and because it was through this marriage that the Spanish throne would ultimately be delivered to the House of Bourbon (which holds it to this day).

Personal reign and reforms

Coming of age and early reforms

Louis XIV was declared to have reached the age of majority on 7 September 1651. On the death of Mazarin, in March 1661, Louis assumed personal control of the reins of government and astonished his court by declaring that he would rule without a chief minister: "Up to this moment I have been pleased to entrust the government of my affairs to the late Cardinal. It is now time that I govern them myself. You

e was talking to the secretaries and ministers of state

E, or e, is the fifth letter and the second vowel letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''e'' (pronounced ); plu ...

will assist me with your counsels when I ask for them. I request and order you to seal no orders except by my command . . . I order you not to sign anything, not even a passport . . . without my command; to render account to me personally each day and to favor no one". Louis was able to capitalize on the widespread public yearning for law and order, that resulted from prolonged foreign wars and domestic civil strife, to further consolidate central political authority and reform at the expense of the feudal aristocracy. Praising his ability to choose and encourage men of talent, the historian

Chateaubriand noted: "it is the voice of genius of all kinds which sounds from the tomb of Louis".

Louis began his personal reign with administrative and fiscal reforms. In 1661, the treasury verged on bankruptcy. To rectify the situation, Louis chose

Jean-Baptiste Colbert

Jean-Baptiste Colbert (; 29 August 1619 – 6 September 1683) was a French statesman who served as First Minister of State from 1661 until his death in 1683 under the rule of King Louis XIV. His lasting impact on the organization of the country ...

as

Controller-General of Finances The Controller-General or Comptroller-General of Finances (french: Contrôleur général des finances) was the name of the minister in charge of finances in France from 1661 to 1791. It replaced the former position of Superintendent of Finances ('' ...

in 1665. However, Louis first had to neutralize

Nicolas Fouquet, the

Superintendent of Finances, in order to give Colbert a free hand. Although Fouquet's financial indiscretions were not very different from Mazarin's before him or Colbert's after him, his ambition was worrying to Louis. He had, for example, built an opulent château at

Vaux-le-Vicomte where he entertained Louis and his court ostentatiously, as if he were wealthier than the king himself. The court was left with the impression that the vast sums of money needed to support his lifestyle could only have been obtained through

embezzlement

Embezzlement is a crime that consists of withholding assets for the purpose of conversion of such assets, by one or more persons to whom the assets were entrusted, either to be held or to be used for specific purposes. Embezzlement is a type ...

of government funds.

Fouquet appeared eager to succeed Mazarin and Richelieu in assuming power, and he indiscreetly purchased and privately fortified the remote island of

Belle Île. These acts sealed his doom. Fouquet was charged with embezzlement. The ''Parlement'' found him guilty and sentenced him to exile. However, Louis altered the sentence to life imprisonment and abolished Fouquet's post.

With Fouquet dismissed, Colbert reduced the national debt through more efficient taxation. The principal taxes included the ''aides'' and ''douanes'' (both

customs duties

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and p ...

), the ''

gabelle'' (a tax on salt), and the ''

taille'' (a tax on land). The ''taille'' was reduced at first; financial officials were forced to keep regular accounts, auctioning certain taxes instead of selling them privately to a favoured few, revising inventories and removing unauthorized exemptions (for example, in 1661 only 10 per cent from the royal domain reached the King). Reform proved difficult because the ''taille'' was levied by officers of the Crown who had purchased their post at a high price: punishment of abuses necessarily lowered the value of the post. Nevertheless, excellent results were achieved: the deficit of 1661 turned into a surplus in 1666. The interest on the debt was reduced from 52 million to 24 million livres. The ''taille'' was reduced to 42 million in 1661 and 35 million in 1665; finally the revenue from indirect taxation progressed from 26 million to 55 million. The revenues of the royal domain were raised from 80,000 livres in 1661 to 5.5 million livres in 1671. In 1661, the receipts were equivalent to 26 million British pounds, of which 10 million reached the treasury. The expenditure was around 18 million pounds, leaving a deficit of 8 million. In 1667, the net receipts had risen to 20 million

pounds sterling, while expenditure had fallen to 11 million, leaving a surplus of 9 million pounds.

To support the reorganized and enlarged army, the panoply of Versailles, and the growing civil administration, the king needed a good deal of money. Finance had always been the weak spot in the French monarchy: methods of collecting taxes were costly and inefficient; direct taxes passed through the hands of many intermediate officials; and indirect taxes were collected by private concessionaries, called tax farmers, who made a substantial profit. Consequently, the state always received far less than what the taxpayers actually paid.

The main weakness arose from an old bargain between the French crown and nobility: the king might raise taxes without consent if only he refrained from taxing the nobles. Only the "unprivileged" classes paid direct taxes, and this term came to mean the peasants only, since many bourgeois, in one way or another, obtained exemptions.

The system was outrageously unjust in throwing a heavy tax burden on the poor and helpless. Later, after 1700, the French ministers who were supported by Louis' secret wife Madame De Maintenon, were able to convince the king to change his fiscal policy. Louis was willing enough to tax the nobles but was unwilling to fall under their control, and only towards the close of his reign, under extreme stress of war, was he able, for the first time in French history, to impose direct taxes on the aristocratic elements of the population. This was a step toward equality before the law and toward sound public finance, but so many concessions and exemptions were won by nobles and bourgeois that the reform lost much of its value.

Louis and Colbert also had wide-ranging plans to bolster French commerce and trade. Colbert's

mercantilist

Mercantilism is an economic policy that is designed to maximize the exports and minimize the imports for an economy. It promotes imperialism, colonialism, tariffs and subsidies on traded goods to achieve that goal. The policy aims to reduc ...

administration established new industries and encouraged manufacturers and inventors, such as the

Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of ...

silk manufacturers and the

Gobelins manufactory

The Gobelins Manufactory () is a historic tapestry factory in Paris, France. It is located at 42 avenue des Gobelins, near Les Gobelins métro station in the 13th arrondissement of Paris. It was originally established on the site as a medieva ...

, a producer of tapestries. He invited manufacturers and artisans from all over Europe to France, such as

Murano

Murano is a series of islands linked by bridges in the Venetian Lagoon, northern Italy. It lies about north of Venice and measures about across with a population of just over 5,000 (2004 figures). It is famous for its glass making. It was on ...

glassmakers, Swedish ironworkers, and Dutch shipbuilders. In this way, he aimed to decrease foreign imports while increasing French exports, hence reducing the net outflow of precious metals from France.

Louis instituted reforms in military administration through

Michel le Tellier and the latter's son

François-Michel le Tellier, Marquis de Louvois. They helped to curb the independent spirit of the nobility, imposing order on them at court and in the army. Gone were the days when generals protracted war at the frontiers while bickering over precedence and ignoring orders from the capital and the larger politico-diplomatic picture. The old military aristocracy (the ''Noblesse d'épée'', or "nobility of the sword") ceased to have a monopoly over senior military positions and rank. Louvois, in particular, pledged to modernize the army and re-organize it into a professional, disciplined, well-trained force. He was devoted to the soldiers' material well-being and morale, and even tried to direct campaigns.

Relations with the major colonies

Legal matters did not escape Louis' attention, as is reflected in the numerous "

Great Ordinances

{{unreferenced, date=April 2022

:''The phrase "Great Ordinance" was also an early term for artillery, more usually spelt "Great Ordnance".''

In French political history, a great ordinance or grand ordinance (French – Grande ordonnance) was an im ...

" he enacted. Pre-revolutionary France was a patchwork of legal systems, with as many legal customs as there were provinces, and two co-existing legal traditions—

customary law

A legal custom is the established pattern of behavior that can be objectively verified within a particular social setting. A claim can be carried out in defense of "what has always been done and accepted by law".

Customary law (also, consuetudina ...

in the north and

Roman civil law in the south. The ''Grande Ordonnance de Procédure Civile'' of 1667, also known as the ''Code Louis'', was a comprehensive legal code attempting a uniform regulation of

civil procedure throughout legally irregular France. Among other things, it prescribed baptismal, marriage and death records in the state's registers, not the church's, and it strictly regulated the right of the ''Parlements'' to remonstrate. The ''Code Louis'' played an important part in French legal history as the basis for the

Napoleonic code, from which many modern legal codes are, in turn, derived.

One of Louis' more infamous decrees was the ''Grande Ordonnance sur les Colonies'' of 1685, also known as the ''

Code Noir

The (, ''Black code'') was a decree passed by the French King Louis XIV in 1685 defining the conditions of slavery in the French colonial empire. The decree restricted the activities of free people of color, mandated the conversion of all e ...

'' ("black code"). Although it sanctioned slavery, it attempted to humanise the practice by prohibiting the separation of families. Additionally, in the colonies, only Roman Catholics could own slaves, and these had to be baptised.

Louis ruled through a number of councils:

* Conseil d'en haut ("High Council", concerning the most important matters of state)—composed of the king, the crown prince, the controller-general of finances, and the secretaries of state in charge of various departments. The members of that council were called ministers of state.

* Conseil des dépêches ("Council of Messages", concerning notices and administrative reports from the provinces).

* Conseil de Conscience ("Council of Conscience", concerning religious affairs and episcopal appointments).

* Conseil royal des finances ("Royal Council of Finances") who was headed by the "chef du conseil des finances" (an honorary post in most cases)—this was one of the few posts in the council that was opened to the high aristocracy.

Early wars in the Low Countries

Spain

The death of his maternal uncle King

Philip IV of Spain

Philip IV ( es, Felipe, pt, Filipe; 8 April 160517 September 1665), also called the Planet King (Spanish: ''Rey Planeta''), was King of Spain from 1621 to his death and (as Philip III) King of Portugal from 1621 to 1640. Philip is remembered ...

, in 1665, precipitated the

War of Devolution

In the 1667 to 1668 War of Devolution (, ), France occupied large parts of the Spanish Netherlands and Franche-Comté, both then provinces of the Holy Roman Empire (and properties of the King of Spain). The name derives from an obscure law k ...

. In 1660, Louis had married Philip IV's eldest daughter,

Maria Theresa

Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina (german: Maria Theresia; 13 May 1717 – 29 November 1780) was ruler of the Habsburg dominions from 1740 until her death in 1780, and the only woman to hold the position '' suo jure'' (in her own right) ...

, as one of the provisions of the 1659

Treaty of the Pyrenees

The Treaty of the Pyrenees (french: Traité des Pyrénées; es, Tratado de los Pirineos; ca, Tractat dels Pirineus) was signed on 7 November 1659 on Pheasant Island, and ended the Franco-Spanish War that had begun in 1635.

Negotiations were ...

. The marriage treaty specified that Maria Theresa was to renounce all claims to Spanish territory for herself and all her descendants. Mazarin and

Lionne, however, made the renunciation conditional on the full payment of a Spanish dowry of 500,000

écus. The dowry was never paid and would later play a part persuading his maternal first cousin

Charles II of Spain

Charles II of Spain (''Spanish: Carlos II,'' 6 November 1661 – 1 November 1700), known as the Bewitched (''Spanish: El Hechizado''), was the last Habsburg ruler of the Spanish Empire. Best remembered for his physical disabilities and the War ...

to leave his empire to Philip, Duke of Anjou (later

Philip V of Spain

Philip V ( es, Felipe; 19 December 1683 – 9 July 1746) was King of Spain from 1 November 1700 to 14 January 1724, and again from 6 September 1724 to his death in 1746. His total reign of 45 years is the longest in the history of the Spanish mo ...

), the grandson of Louis XIV and Maria Theresa.

The War of Devolution did not focus on the payment of the dowry; rather, the lack of payment was what Louis XIV used as a pretext for nullifying Maria Theresa's renunciation of her claims, allowing the land to "devolve" to him. In

Brabant Brabant is a traditional geographical region (or regions) in the Low Countries of Europe. It may refer to:

Place names in Europe

* London-Brabant Massif, a geological structure stretching from England to northern Germany

Belgium

* Province of Bra ...

(the location of the land in dispute), children of first marriages traditionally were not disadvantaged by their parents' remarriages and still inherited property. Louis' wife was Philip IV's daughter by his first marriage, while the new king of Spain, Charles II, was his son by a subsequent marriage. Thus, Brabant allegedly "devolved" to Maria Theresa, giving France a justification to attack the

Spanish Netherlands

Spanish Netherlands ( Spanish: Países Bajos Españoles; Dutch: Spaanse Nederlanden; French: Pays-Bas espagnols; German: Spanische Niederlande.) (historically in Spanish: ''Flandes'', the name "Flanders" was used as a '' pars pro toto'') was the ...

.

Relations with the Dutch

During the

Eighty Years' War

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt ( nl, Nederlandse Opstand) ( c.1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish government. The causes of the war included the Ref ...

with

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, France supported the

Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands ( Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiograph ...

as part of a general policy of opposing Habsburg power.

Johan de Witt

Johan de Witt (; 24 September 1625 – 20 August 1672), ''lord of Zuid- en Noord-Linschoten, Snelrewaard, Hekendorp en IJsselvere'', was a Dutch statesman and a major political figure in the Dutch Republic in the mid-17th century, the F ...

, Dutch

Grand Pensionary from 1653 to 1672, viewed them as crucial for Dutch security and against his domestic

Orangist opponents. Louis provided support in the 1665-1667

Second Anglo-Dutch War

The Second Anglo-Dutch War or the Second Dutch War (4 March 1665 – 31 July 1667; nl, Tweede Engelse Oorlog "Second English War") was a conflict between England and the Dutch Republic partly for control over the seas and trade routes, whe ...

but used the opportunity to launch the

War of Devolution

In the 1667 to 1668 War of Devolution (, ), France occupied large parts of the Spanish Netherlands and Franche-Comté, both then provinces of the Holy Roman Empire (and properties of the King of Spain). The name derives from an obscure law k ...

in 1667. This captured

Franche-Comté

Franche-Comté (, ; ; Frainc-Comtou: ''Fraintche-Comtè''; frp, Franche-Comtât; also german: Freigrafschaft; es, Franco Condado; all ) is a cultural and historical region of eastern France. It is composed of the modern departments of Doubs, ...

and much of the

Spanish Netherlands

Spanish Netherlands ( Spanish: Países Bajos Españoles; Dutch: Spaanse Nederlanden; French: Pays-Bas espagnols; German: Spanische Niederlande.) (historically in Spanish: ''Flandes'', the name "Flanders" was used as a '' pars pro toto'') was the ...

; French expansion in this area was a direct threat to Dutch economic interests.

The Dutch opened talks with

Charles II of England

Charles II (29 May 1630 – 6 February 1685) was King of Scotland from 1649 until 1651, and King of England, Scotland and Ireland from the 1660 Restoration of the monarchy until his death in 1685.

Charles II was the eldest surviving child o ...

on a common diplomatic front against France, leading to the

Triple Alliance, between England, the Dutch and

Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic countries, Nordic c ...

. The threat of an escalation and a secret treaty to divide Spanish possessions with

Emperor Leopold

Leopold I (Leopold Ignaz Joseph Balthasar Franz Felician; hu, I. Lipót; 9 June 1640 – 5 May 1705) was Holy Roman Emperor, King of Hungary, Croatia, and Bohemia. The second son of Ferdinand III, Holy Roman Emperor, by his first wife, Maria A ...

, the other major claimant to the throne of Spain, led Louis to relinquish many of his gains in the 1668

Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle.

Louis placed little reliance on his agreement with

Leopold and as it was now clear French and Dutch aims were in direct conflict, he decided to first defeat the

Republic

A republic () is a " state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th ...

, then seize the Spanish Netherlands. This required breaking up the Triple Alliance; he paid Sweden to remain neutral and signed the 1670

Secret Treaty of Dover

The Treaty of Dover, also known as the Secret Treaty of Dover, was a treaty between England and France signed at Dover on 1 June 1670. It required that Charles II of England would convert to the Roman Catholic Church at some future date and th ...

with Charles, an Anglo-French alliance against the Dutch Republic. In May 1672, France invaded the

Republic

A republic () is a " state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th ...

, supported by

Münster

Münster (; nds, Mönster) is an independent city (''Kreisfreie Stadt'') in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is in the northern part of the state and is considered to be the cultural centre of the Westphalia region. It is also a state di ...

and the

Electorate of Cologne

The Electorate of Cologne (german: Kurfürstentum Köln), sometimes referred to as Electoral Cologne (german: Kurköln, links=no), was an ecclesiastical principality of the Holy Roman Empire that existed from the 10th to the early 19th century. ...

.

Rapid French advance led to a coup that toppled

De Witt and brought

William III to power.

Leopold viewed French expansion into the Rhineland as an increasing threat, especially after their seizure of the strategic

Duchy of Lorraine in 1670. The prospect of Dutch defeat led Leopold to an alliance with

Brandenburg-Prussia

Brandenburg-Prussia (german: Brandenburg-Preußen; ) is the historiographic denomination for the early modern realm of the Brandenburgian Hohenzollerns between 1618 and 1701. Based in the Electorate of Brandenburg, the main branch of the Hohe ...

on 23 June, followed by another with the Republic on 25th. Although Brandenburg was forced out of the war by the June 1673

Treaty of Vossem, in August an anti-French alliance was formed by the Dutch,

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, Emperor Leopold and the

Duke of Lorraine.

The French alliance was deeply unpopular in England, who made peace with the Dutch in the February 1674

Treaty of Westminster. However, French armies held significant advantages over their opponents; an undivided command, talented generals like

Turenne,

Condé and

Luxembourg

Luxembourg ( ; lb, Lëtzebuerg ; french: link=no, Luxembourg; german: link=no, Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, ; french: link=no, Grand-Duché de Luxembourg ; german: link=no, Großherzogtum Luxemburg is a small lan ...

and vastly superior logistics. Reforms introduced by

Louvois, the

Secretary of War, helped maintain large field armies that could be mobilised much more quickly, allowing them to mount offensives in early spring before their opponents were ready.

The French were forced to retreat from the Dutch Republic but these advantages allowed them to hold their ground in Alsace and the Spanish Netherlands while retaking Franche-Comté. By 1678, mutual exhaustion led to the

Treaty of Nijmegen

The Treaties of Peace of Nijmegen ('; german: Friede von Nimwegen) were a series of treaties signed in the Dutch city of Nijmegen between August 1678 and October 1679. The treaties ended various interconnected wars among France, the Dutch Repub ...

, which was generally settled in France's favour and allowed Louis to intervene in the

Scanian War

The Scanian War ( da, Skånske Krig, , sv, Skånska kriget, german: Schonischer Krieg) was a part of the Northern Wars involving the union of Denmark–Norway, Brandenburg and Sweden. It was fought from 1675 to 1679 mainly on Scanian soil, ...

. Despite military defeat, his ally Sweden regained much of what they had lost under the 1679 treaties of

Saint-Germain-en-Laye,

Fontainebleau

Fontainebleau (; ) is a commune in the metropolitan area of Paris, France. It is located south-southeast of the centre of Paris. Fontainebleau is a sub-prefecture of the Seine-et-Marne department, and it is the seat of the ''arrondissemen ...

and

Lund

Lund (, , ) is a city in the southern Swedish province of Scania, across the Öresund strait from Copenhagen. The town had 91,940 inhabitants out of a municipal total of 121,510 . It is the seat of Lund Municipality, Scania County. The Öre ...

imposed on

Denmark-Norway and Brandenburg.

Louis was at the height of his power, but at the cost of uniting his opponents; this increased as he continued his expansion. In 1679, he dismissed his foreign minister

Simon Arnauld, marquis de Pomponne, because he was seen as having compromised too much with the allies. Louis maintained the strength of his army, but in his next series of territorial claims avoided using military force alone. Rather, he combined it with legal pretexts in his efforts to augment the boundaries of his kingdom. Contemporary treaties were intentionally phrased ambiguously. Louis established the

Chambers of Reunion to determine the full extent of his rights and obligations under those treaties.

Cities and territories, such as

Luxembourg

Luxembourg ( ; lb, Lëtzebuerg ; french: link=no, Luxembourg; german: link=no, Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, ; french: link=no, Grand-Duché de Luxembourg ; german: link=no, Großherzogtum Luxemburg is a small lan ...

and

Casale, were prized for their strategic positions on the frontier and access to important waterways. Louis also sought

Strasbourg

Strasbourg (, , ; german: Straßburg ; gsw, label= Bas Rhin Alsatian, Strossburi , gsw, label= Haut Rhin Alsatian, Strossburig ) is the prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est region of eastern France and the official seat of the ...

, an important strategic crossing on the left bank of the Rhine and theretofore a Free Imperial City of the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

, annexing it and other territories in 1681. Although a part of Alsace, Strasbourg was not part of Habsburg-ruled Alsace and was thus not ceded to France in the Peace of Westphalia.

Following these annexations, Spain declared war, precipitating the

War of the Reunions. However, the Spanish were rapidly defeated because the Emperor (distracted by the

Great Turkish War

The Great Turkish War (german: Großer Türkenkrieg), also called the Wars of the Holy League ( tr, Kutsal İttifak Savaşları), was a series of conflicts between the Ottoman Empire and the Holy League consisting of the Holy Roman Empire, Pola ...

) abandoned them, and the Dutch only supported them minimally. By the

Truce of Ratisbon, in 1684, Spain was forced to acquiesce in the French occupation of most of the conquered territories, for 20 years.

Louis' policy of the ''Réunions'' may have raised France to its greatest size and power during his reign, but it alienated much of Europe. This poor public opinion was compounded by French actions off the Barbary Coast and at Genoa. First, Louis had

Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques d ...

and

Tripoli, two Barbary pirate strongholds, bombarded to obtain a favourable treaty and the liberation of Christian slaves. Next, in 1684, a

punitive mission was launched against

Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

in retaliation for its support for Spain in previous wars. Although the Genoese submitted, and the

Doge led an official mission of apology to Versailles, France gained a reputation for brutality and arrogance. European apprehension at growing French might and the realisation of the extent of the

dragonnades

The ''Dragonnades'' were a French government policy instituted by King Louis XIV in 1681 to intimidate Huguenot (Protestant) families into converting to Catholicism. This involved the billeting of ill-disciplined dragoons in Protestant household ...

' effect (discussed below) led many states to abandon their alliances with France. Accordingly, by the late 1680s, France became increasingly isolated in Europe.

Non-European relations and the colonies

French colonies

French colonies multiplied in Africa, the Americas, and Asia during Louis' reign, and French explorers made important discoveries in North America. In 1673,

Louis Jolliet and

Jacques Marquette

Jacques Marquette S.J. (June 1, 1637 – May 18, 1675), sometimes known as Père Marquette or James Marquette, was a French Jesuit missionary who founded Michigan's first European settlement, Sault Sainte Marie, and later founded Saint Ign ...

discovered the

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

. In 1682,

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle (; November 22, 1643 – March 19, 1687), was a 17th-century French explorer and fur trader in North America. He explored the Great Lakes region of the United States and Canada, the Mississippi River, ...

, followed the

Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

to the

Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United ...

and claimed the vast Mississippi basin in Louis' name, calling it ''

Louisiane''. French trading posts were also established in India, at

Chandernagore and

Pondicherry, and in the Indian Ocean at

Île Bourbon. Throughout these regions Louis and Colbert embarked on an extensive program of architecture and urbanism meant to reflect the styles of Versailles and Paris and the 'gloire' of the realm.

Meanwhile, diplomatic relations were initiated with distant countries. In 1669,

Suleiman Aga

Müteferrika Süleyman Ağa, known as Suleiman Aga and Soleiman Agha in France, was an Ottoman Empire ambassador to the French king Louis XIV in 1669. Suleiman visited Versailles, but only wore a simple wool coat and refused to bow to Louis XIV, ...

led an

Ottoman embassy to revive the old

Franco-Ottoman alliance. Then, in 1682, after the reception of the Moroccan embassy of

Mohammed Tenim

Mohammad Temim (), also Haji Mohammad Temim (French: ''Aggi Mohamed'') was an ambassador of the Moroccan king Mulay Ismail to France. Mohammad Temim was accompanied by Ali Manino, as well as six other ambassadorial members. They visited Paris in ...

in France,

Moulay Ismail, Sultan of Morocco, allowed French consular and commercial establishments in his country. In 1699, Louis once again received a Moroccan ambassador,

Abdallah bin Aisha

Abdallah ben Aisha (), also Abdellah bin Aicha, was a Moroccan Admiral and ambassador to France and England in the 17th century. Abdallah departed for France on 11 November 1698 in order to negotiate a treaty.''In the Land of the Christians'' by ...

, and in 1715, he received a

Persian embassy led by

Mohammad Reza Beg

Mohammad Reza Beg (Persian: محمدرضا بیگ, in French-language sources; ''Méhémet Riza Beg''), was the Safavid mayor (''kalantar'') of Erivan (Iravan), and the ambassador to France during the reign of king Sultan Husayn (1694-1722). He ...

.

From farther afield, Siam dispatched an embassy in 1684, reciprocated by the French magnificently the next year under

Alexandre, Chevalier de Chaumont

Alexandre, Chevalier de Chaumont (1640 – 28 January 1710 in Paris) was the first French ambassador for King Louis XIV in Siam in 1685.Chakrabongse, C., 1960, Lords of Life, London: Alvin Redman Limited He was accompanied on his mission by Ab ...

. This, in turn, was succeeded by another Siamese embassy under

Kosa Pan, superbly received at Versailles in 1686. Louis then sent another embassy in 1687, under

Simon de la Loubère, and French influence grew at the Siamese court, which granted

Mergui

Myeik (, or ; mnw, ဗိက်, ; th, มะริด, , ; formerly Mergui, ) is a rural city in Tanintharyi Region in Myanmar (Burma), located in the extreme south of the country on the coast off an island on the Andaman Sea. , the estimat ...

as a naval base to France. However, the death of

Narai, King of Ayutthaya, the execution of his pro-French minister

Constantine Phaulkon

Constantine Phaulkon (Greek: Κωνσταντῖνος Γεράκης, ''Konstantinos Gerakis''; γεράκι is the Greek word for "falcon"; 1647 – 5 June 1688, also known as Costantin Gerachi, ''Capitão Falcão'' in Portuguese and simply as ' ...

, and the

Siege of Bangkok

The siege of Bangkok was a key event of the Siamese revolution of 1688, in which the Kingdom of Siam ousted the French from Siam. Following a coup d'état, in which the pro-Western king Narai was replaced by Phetracha, Siamese troops besieged the ...

in 1688 ended this era of French influence.

France also attempted to participate actively in

Jesuit missions

The phrase Jesuit missions usually refers to a Jesuit missionary enterprise in a particular area, involving a large number of Jesuit priests and brothers, and lasting over a long period of time.

List of some Jesuit missions

* Circular Mission ...

to China. To break the Portuguese dominance there, Louis sent Jesuit missionaries to the court of the

Kangxi Emperor

The Kangxi Emperor (4 May 1654– 20 December 1722), also known by his temple name Emperor Shengzu of Qing, born Xuanye, was the third emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the second Qing emperor to rule over China proper, reigning from 1661 to ...

in 1685:

Jean de Fontaney

Jean de Fontaney (1643–1710) was a French Jesuit who led a mission to China in 1687.Mungello, p. 329

Jean de Fontaney had been a teacher of mathematics and astronomy at the College Louis le Grand. He was asked by king Louis XIV to set up a mi ...

,

Joachim Bouvet,

Jean-François Gerbillon,

Louis Le Comte Louis le Comte (1655–1728), also Louis-Daniel Lecomte, was a French Jesuit who participated in the 1687 French Jesuit mission to China under Jean de Fontaney. He arrived in China on 7 February 1688.

He returned to France in 1691 as Procurator o ...

, and

Claude de Visdelou

Claude de Visdelou (12 August 1656 – 11 November 1737) was a French Jesuit missionary.

Life

De Visdelou was born at the Château de Bienassis, Erquy, Brittany. He entered the Society of Jesus on 5 September 1673, and was one of the missiona ...

. Louis also received a Chinese Jesuit,

Michael Shen Fu-Tsung, at Versailles in 1684. Furthermore, Louis' librarian and translator

Arcadio Huang

Arcadio Huang (, born in Xinghua, modern Putian, in Fujian, 15 November 1679, died on 1 October 1716 in Paris)Mungello, p.125 was a Chinese Christian convert, brought to Paris by the Missions étrangères. He took a pioneering role in the teachi ...

was Chinese.

Height of power

Centralisation of power

By the early 1680s, Louis had greatly augmented French influence in the world. Domestically, he successfully increased the influence of the crown and its authority over the church and aristocracy, thus consolidating absolute monarchy in France.

Louis initially supported traditional

Gallicanism, which limited

papal

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

authority in France, and convened an

Assembly of the French clergy in November 1681. Before its dissolution eight months later, the Assembly had accepted the

Declaration of the Clergy of France, which increased royal authority at the expense of papal power. Without royal approval, bishops could not leave France, and appeals could not be made to the pope. Additionally, government officials could not be excommunicated for acts committed in pursuance of their duties. Although the king could not make ecclesiastical law, all papal regulations without royal assent were invalid in France. Unsurprisingly, the Pope repudiated the Declaration.

[

] By attaching nobles to his court at Versailles, Louis achieved increased control over the French aristocracy. According to historian Philip Mansel, the king turned the palace into:

:an irresistible combination of marriage market, employment agency and entertainment capital of aristocratic Europe, boasting the best theatre, opera, music, gambling, sex and (most important) hunting.

Apartments were built to house those willing to pay court to the king.

By attaching nobles to his court at Versailles, Louis achieved increased control over the French aristocracy. According to historian Philip Mansel, the king turned the palace into:

:an irresistible combination of marriage market, employment agency and entertainment capital of aristocratic Europe, boasting the best theatre, opera, music, gambling, sex and (most important) hunting.

Apartments were built to house those willing to pay court to the king.[ For this purpose, an elaborate court ritual was created wherein the king became the centre of attention and was observed throughout the day by the public. With his excellent memory, Louis could then see who attended him at court and who was absent, facilitating the subsequent distribution of favours and positions. Another tool Louis used to control his nobility was censorship, which often involved the opening of letters to discern their author's opinion of the government and king.][ Moreover, by entertaining, impressing, and domesticating them with extravagant luxury and other distractions, Louis not only cultivated public opinion of him, but he also ensured the aristocracy remained under his scrutiny.

Louis's extravagance at Versailles extended far beyond the scope of elaborate court rituals. He took delivery of an African elephant as a gift from the king of Portugal. He encouraged leading nobles to live at Versailles. This, along with the prohibition of private armies, prevented them from passing time on their own estates and in their regional power bases, from which they historically waged local wars and plotted resistance to royal authority. Louis thus compelled and seduced the old military aristocracy (the "nobility of the sword") into becoming his ceremonial courtiers, further weakening their power. In their place, he raised commoners or the more recently ennobled bureaucratic aristocracy (the "nobility of the robe"). He judged that royal authority thrived more surely by filling high executive and administrative positions with these men because they could be more easily dismissed than nobles of ancient lineage and entrenched influence. It is believed that Louis's policies were rooted in his experiences during the ''Fronde'', when men of high birth readily took up the rebel cause against their king, who was actually the kinsman of some. This victory over the nobility may thus have ensured the end of major civil wars in France until the French Revolution about a century later.

]

France as the pivot of warfare

Under Louis, France was the leading European power, and most wars pivoted around its aggressiveness. No European state exceeded it in population, and no one could match its wealth, central location, and very strong professional army. It had largely avoided the devastation of the Thirty Years' War. Its weaknesses included an inefficient financial system that was hard-pressed to pay for its military adventures, and the tendency of most other powers to gang up against it.

During Louis's reign, France fought three major wars: the Franco-Dutch War

The Franco-Dutch War, also known as the Dutch War (french: Guerre de Hollande; nl, Hollandse Oorlog), was fought between France and the Dutch Republic, supported by its allies the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, Brandenburg-Prussia and Denmark-Nor ...

, the War of the League of Augsburg, and the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

. There were also two lesser conflicts: the War of Devolution

In the 1667 to 1668 War of Devolution (, ), France occupied large parts of the Spanish Netherlands and Franche-Comté, both then provinces of the Holy Roman Empire (and properties of the King of Spain). The name derives from an obscure law k ...

and the War of the Reunions. The wars were very expensive but defined Louis XIV's foreign policy, and his personality shaped his approach. Impelled "by a mix of commerce, revenge, and pique," Louis sensed that war was the ideal way to enhance his glory. In peacetime he concentrated on preparing for the next war. He taught his diplomats that their job was to create tactical and strategic advantages for the French military. By 1695, France retained much of its dominance but had lost control of the seas to England and Holland, and most countries, both Protestant and Catholic, were in alliance against it. Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban

Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, Seigneur de Vauban, later Marquis de Vauban (baptised 15 May 163330 March 1707), commonly referred to as ''Vauban'' (), was a French military engineer who worked under Louis XIV. He is generally considered the ...

, France's leading military strategist, warned Louis in 1689 that a hostile "Alliance" was too powerful at sea. He recommended that France fight back by licensing French merchants ships to privateer and seize enemy merchant ships while avoiding its navies:

:France has its declared enemies Germany and all the states that it embraces; Spain with all its dependencies in Europe, Asia, Africa and America; the Duke of Savoy n Italy

N, or n, is the fourteenth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''en'' (pronounced ), plural ''ens''.

History

...

England, Scotland, Ireland, and all their colonies in the East and West Indies; and Holland with all its possessions in the four corners of the world where it has great establishments. France has ... undeclared enemies, indirectly hostile, hostile, and envious of its greatness, Denmark, Sweden, Poland, Portugal, Venice, Genoa, and part of the Swiss Confederation, all of which states secretly aid France's enemies by the troops that they hire to them, the money they lend them and by protecting and covering their trade.

Vauban was pessimistic about France's so-called friends and allies:

:For lukewarm, useless, or impotent friends, France has the Pope, who is indifferent; the King of England ames II

Ames may refer to:

Places United States

* Ames, Arkansas, a place in Arkansas

* Ames, Colorado

* Ames, Illinois

* Ames, Indiana

* Ames, Iowa, the most populous city bearing this name

* Ames, Kansas

* Ames, Nebraska

* Ames, New York

* Ames, ...

expelled from his country; the Grand Duke of Tuscany; the Dukes of Mantua, Modena, and Parma ll in Italy

Ll/ll is a digraph that occurs in several languages

English

In English, often represents the same sound as single : . The doubling is used to indicate that the preceding vowel is (historically) short, or that the "l" sound is to be extended ...