Kirchenkampf on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Kirchenkampf'' (, lit. 'church struggle') is a German term which pertains to the situation of the Christian churches in Germany during the Nazi period (1933–1945). Sometimes used ambiguously, the term may refer to one or more of the following different "church struggles":

# The internal dispute within German Protestantism between the

, ''Rutgers Journal of Law and Religion'', Winter 2001, publishing evidence compiled by the O.S.S. for the Nuremberg war-crimes trials of 1945 and 1946 Other historians maintain no such plan existed.

Nazism wanted to transform the subjective consciousness of the German people – their attitudes, values, and mentalities – into a single-minded, obedient ''

Nazism wanted to transform the subjective consciousness of the German people – their attitudes, values, and mentalities – into a single-minded, obedient ''

*Hitler makes efforts to assimilate the churches into the culture of Nazism.

*Hitler moves to eliminate

*Hitler makes efforts to assimilate the churches into the culture of Nazism.

*Hitler moves to eliminate

Prior to the Reichstag vote for the

Prior to the Reichstag vote for the

Leading Nazis varied in the importance they attached to the Church Struggle. Kershaw wrote that, to the new Nazi government, Race policy and the 'Church Struggle' were among the most important ideological spheres: "In both areas, the party had no difficulty in mobilizing its activists, whose radicalism in turn forced the government into legislative action. In fact the party leadership often found itself compelled to respond to pressures from below, stirred up by the ''

Leading Nazis varied in the importance they attached to the Church Struggle. Kershaw wrote that, to the new Nazi government, Race policy and the 'Church Struggle' were among the most important ideological spheres: "In both areas, the party had no difficulty in mobilizing its activists, whose radicalism in turn forced the government into legislative action. In fact the party leadership often found itself compelled to respond to pressures from below, stirred up by the ''

In January 1934, Hitler appointed

In January 1934, Hitler appointed

By early 1937, the church hierarchy in Germany, which had initially attempted to co-operate with the new government, had become highly disillusioned. In March,

By early 1937, the church hierarchy in Germany, which had initially attempted to co-operate with the new government, had become highly disillusioned. In March,

Kershaw wrote that the subjugation of the Protestant churches proved more difficult than Hitler had envisaged. With 28 separate regional churches, his bid to create a unified Reich Church through ''

Kershaw wrote that the subjugation of the Protestant churches proved more difficult than Hitler had envisaged. With 28 separate regional churches, his bid to create a unified Reich Church through ''

German Christians

Christianity is the largest religion in Germany. It was introduced to the area of modern Germany by 300 AD, while parts of that area belonged to the Roman Empire, and later, when Franks and other Germanic tribes converted to Christianity from t ...

(''Deutsche Christen'') and the Confessing Church

The Confessing Church (german: link=no, Bekennende Kirche, ) was a movement within German Protestantism during Nazi Germany that arose in opposition to government-sponsored efforts to unify all Protestant churches into a single pro-Nazi German E ...

(''Bekennende Kirche'') over control of the Protestant churches;

# The tensions between the Nazi regime and the Protestant church bodies; and

# The tensions between the Nazi regime and the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

.

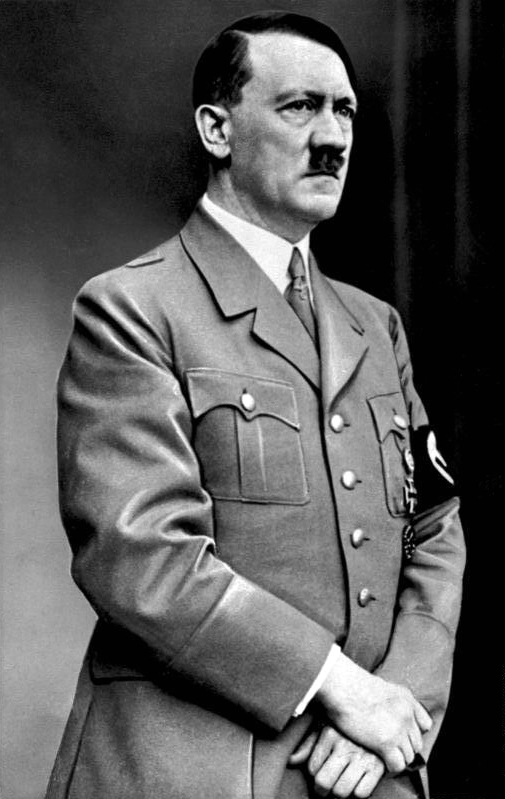

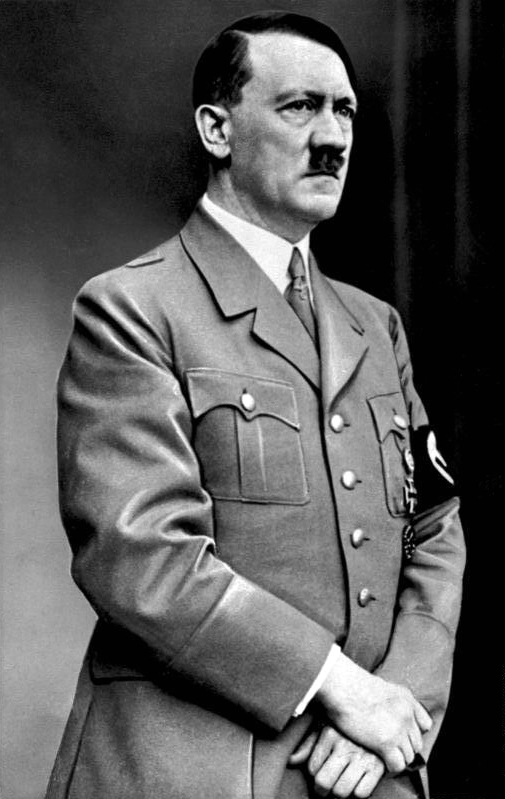

When Hitler obtained power in 1933, 95% of Germans were Christian, with 63% being Protestant and 32% being Catholic. Many historians maintain that Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and then ...

's goal in the ''Kirchenkampf'' entailed not only ideological struggle, but ultimately the eradication of the churches.The Nazi Master Plan: The Persecution of the Christian Churches, ''Rutgers Journal of Law and Religion'', Winter 2001, publishing evidence compiled by the O.S.S. for the Nuremberg war-crimes trials of 1945 and 1946 Other historians maintain no such plan existed.

The Salvation Army

The Salvation Army (TSA) is a Protestant church and an international charitable organisation headquartered in London, England. The organisation reports a worldwide membership of over 1.7million, comprising soldiers, officers and adherents col ...

, Christian Saints, Bruderhof, and the Seventh-day Adventist Church

The Seventh-day Adventist Church is an Adventist Protestant Christian denomination which is distinguished by its observance of Saturday, the seventh day of the week in the Christian (Gregorian) and the Hebrew calendar, as the Sabbath, and ...

all disappeared from Germany during the Nazi era.

Some leading Nazis such as Alfred Rosenberg

Alfred Ernst Rosenberg ( – 16 October 1946) was a Baltic German Nazi theorist and ideologue. Rosenberg was first introduced to Adolf Hitler by Dietrich Eckart and he held several important posts in the Nazi government. He was the head of ...

and Martin Bormann

Martin Ludwig Bormann (17 June 1900 – 2 May 1945) was a German Nazi Party official and head of the Nazi Party Chancellery. He gained immense power by using his position as Adolf Hitler's private secretary to control the flow of information ...

were vehemently anti-Christian, and sought to de-Christianize Germany in the long term in favor of a racialized form of Germanic paganism

Germanic paganism or Germanic religion refers to the traditional, culturally significant religion of the Germanic peoples. With a chronological range of at least one thousand years in an area covering Scandinavia, the British Isles, modern Germ ...

. The Nazi Party saw the church struggle as an important ideological battleground. Hitler biographer Ian Kershaw

Sir Ian Kershaw (born 29 April 1943) is an English historian whose work has chiefly focused on the social history of 20th-century Germany. He is regarded by many as one of the world's leading experts on Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany, and is pa ...

wrote of the struggle in terms of an ongoing and escalating conflict between the Nazi state and the Christian churches. Historian Susannah Heschel

Susannah Heschel (born 15 May 1956) is an American scholar and the Eli M. Black Distinguished Professor of Jewish Studies at Dartmouth College. The author and editor of numerous books and articles, she is a Guggenheim Fellow and the recipient of ...

wrote that the ''Kirchenkampf'' refers only to an internal dispute between members of the Confessing Church

The Confessing Church (german: link=no, Bekennende Kirche, ) was a movement within German Protestantism during Nazi Germany that arose in opposition to government-sponsored efforts to unify all Protestant churches into a single pro-Nazi German E ...

and members of the (Nazi-backed) "German Christians

Christianity is the largest religion in Germany. It was introduced to the area of modern Germany by 300 AD, while parts of that area belonged to the Roman Empire, and later, when Franks and other Germanic tribes converted to Christianity from t ...

" over control of the Protestant church. Pierre Aycoberry wrote that for Catholics the phrase ''kirchenkampf'' was reminiscent of the ''kulturkampf

(, 'culture struggle') was the conflict that took place from 1872 to 1878 between the Catholic Church led by Pope Pius IX and the government of Prussia led by Otto von Bismarck. The main issues were clerical control of education and ecclesiastic ...

'' of Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of J ...

's time – a campaign which had sought to reduce the influence of the Catholic Church in majority Protestant Germany.

Background

Nazism wanted to transform the subjective consciousness of the German people – their attitudes, values, and mentalities – into a single-minded, obedient ''

Nazism wanted to transform the subjective consciousness of the German people – their attitudes, values, and mentalities – into a single-minded, obedient ''Volksgemeinschaft

''Volksgemeinschaft'' () is a German expression meaning "people's community", "folk community",Richard Grunberger, ''A Social History of the Third Reich'', London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971, p. 44. "national community", or "racial community", ...

'' or "National People's Community". According to Ian Kershaw

Sir Ian Kershaw (born 29 April 1943) is an English historian whose work has chiefly focused on the social history of 20th-century Germany. He is regarded by many as one of the world's leading experts on Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany, and is pa ...

, in order to achieve this, the Nazis believed they would have to replace class, religious and regional allegiances by a "massively enhanced national self-awareness to mobilize the German people psychologically for the coming struggle and to boost their morale during the inevitable war". According to Anton Gill

Anton Gill (born in 1948) is a British writer of historical fiction and nonfiction. He won the H. H. Wingate Award for non-fiction for ''The Journey Back From Hell'', an account of the lives of survivors after their liberation from Nazi concentr ...

, the Nazis disliked universities, intellectuals and the Catholic and Protestant churches, their long term plan being to "de-Christianise Germany after the final victory". The Nazis co-opted the term ''Gleichschaltung

The Nazi term () or "coordination" was the process of Nazification by which Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party successively established a system of totalitarian control and coordination over all aspects of German society and societies occupied b ...

'' (coordination) to mean conformity and subservience to the Nazi Party line: "there was to be no law but Hitler, and ultimately no god but Hitler". Other authors, such as Richard Steigmann-Gall

Richard Steigmann-Gall (Born October 3, 1965) is an Associate Professor of History at Kent State University, and the former Director of the Jewish Studies Program from 2004 to 2010.

Education

He received his BA in history in 1989 and MA ...

, argue that there were anti-Christian individuals in the Nazi Party but that they did not represent the movement's position.

Nazi ideology

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

conflicted with traditional Christian beliefs in various respects – Nazis criticized Christian notions of "meekness and guilt" on the basis that they "repressed the violent instincts necessary to prevent inferior races from dominating Aryans". Aggressive anti-church radicals like Alfred Rosenberg

Alfred Ernst Rosenberg ( – 16 October 1946) was a Baltic German Nazi theorist and ideologue. Rosenberg was first introduced to Adolf Hitler by Dietrich Eckart and he held several important posts in the Nazi government. He was the head of ...

and Martin Bormann

Martin Ludwig Bormann (17 June 1900 – 2 May 1945) was a German Nazi Party official and head of the Nazi Party Chancellery. He gained immense power by using his position as Adolf Hitler's private secretary to control the flow of information ...

saw the conflict with the churches as a priority concern, and anti-church and anti-clerical sentiments were strong among grassroots party activists. East Prussian Party ''Gauleiter

A ''Gauleiter'' () was a regional leader of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) who served as the head of a ''Administrative divisions of Nazi Germany, Gau'' or ''Reichsgau''. ''Gauleiter'' was the third-highest Ranks and insignia of the Nazi Party, rank in ...

'' Erich Koch

Erich Koch (19 June 1896 – 12 November 1986) was a ''Gauleiter'' of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in East Prussia from 1 October 1928 until 1945. Between 1941 and 1945 he was Chief of Civil Administration (''Chef der Zivilverwaltung'') of Bezirk ...

on the other hand, said that Nazism "had to develop from a basic Prussian-Protestant attitude and from Luther's unfinished Reformation". Hitler himself disdained Christianity, as Alan Bullock

Alan Louis Charles Bullock, Baron Bullock, (13 December 1914 – 2 February 2004) was a British historian. He is best known for his book '' Hitler: A Study in Tyranny'' (1952), the first comprehensive biography of Adolf Hitler, which influence ...

noted:

In ''Mein Kampf

(; ''My Struggle'' or ''My Battle'') is a 1925 autobiographical manifesto by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler. The work describes the process by which Hitler became antisemitic and outlines his political ideology and future plans for Germ ...

'', although Hitler claimed that he was doing the work of the Lord by fighting Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, nevertheless, in another chapter, ''Philosophy and Organization'', he denounced Christianity as a "spiritual terror" that spread into the Ancient world

Ancient history is a time period from the beginning of writing and recorded human history to as far as late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the Sumerian cuneiform script. Ancient history cove ...

.

Though raised a Catholic, Hitler rejected the Judeo-Christian

The term Judeo-Christian is used to group Christianity and Judaism together, either in reference to Christianity's derivation from Judaism, Christianity's borrowing of Jewish Scripture to constitute the "Old Testament" of the Christian Bible, or ...

conception of God and religion. Though he retained some regard for the organizational power of Catholicism, he had utter contempt for its central teachings, which he said, if taken to their conclusion, "would mean the systematic cultivation of the human failure". Hitler ultimately believed "one is either a Christian or a German" – to be both was impossible. However, important German conservative elements, such as the officer corps, opposed Nazi persecution of the churches and, in office, Hitler restrained his anticlerical instincts out of political considerations.

Hitler biographer Ian Kershaw wrote that, while many ordinary people were apathetic, after years of warning from Catholic clergy, Germany's Catholic population greeted the Nazi takeover with apprehension and uncertainty, while among German Protestants, many were optimistic a strengthened Germany might bring with it "inner, moral revitalisation". However, within a short period, the Nazi government's conflict with the churches was to become a source of great bitterness.

Five stages

The ''Kirchenkampf'' can be divided into five stages.First (spring to fall 1933)

*Hitler makes efforts to assimilate the churches into the culture of Nazism.

*Hitler moves to eliminate

*Hitler makes efforts to assimilate the churches into the culture of Nazism.

*Hitler moves to eliminate Political Catholicism

The Catholic Church and politics concerns the interplay of Catholicism with religious, and later secular, politics. Historically, the Church opposed liberal ideas such as democracy, freedom of speech, and the separation of church and state unde ...

: dissolution of Catholic aligned political parties and signing of ''Reichskonkordat

The ''Reichskonkordat'' ("Concordat between the Holy See and the German Reich") is a treaty negotiated between the Vatican and the emergent Nazi Germany. It was signed on 20 July 1933 by Cardinal Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli, who later be ...

'' with Vatican. Sporadic persecution of Catholics.

*Preparation to create unified single '' Reichskirche'' from the 28 regional Protestant churches: Hitler installs pro-Nazi chaplain Ludwig Müller

Johan Heinrich Ludwig Müller (23 June 1883 – 31 July 1945) was a German theologian, a Lutheran pastor, and leading member of the pro-Nazi "German Christians" (german: Deutsche Christen) faith movement. In 1933 he was appointed by the Nazi go ...

as Reich Bishop; splitting German Protestants.

Second (fall 1933 to fall 1934)

*Regime attempts to bring churches under control of the Nazi state (''Gleichschaltung

The Nazi term () or "coordination" was the process of Nazification by which Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party successively established a system of totalitarian control and coordination over all aspects of German society and societies occupied b ...

'').

*Nazi breaches of Concordat commence immediately after signing: sterilization law promulgated, Catholic Youth Leagues dissolved; clergy, nuns and lay leaders harassed.

*Heretical views of Reich Bishop and ''German Christians

Christianity is the largest religion in Germany. It was introduced to the area of modern Germany by 300 AD, while parts of that area belonged to the Roman Empire, and later, when Franks and other Germanic tribes converted to Christianity from t ...

'', leads Martin Neimoller to found ''Pastors' Emergency League

The ''Pfarrernotbund'' ( en, Emergency Covenant of Pastors) was an organisation founded on 21 September 1933 to unite German evangelical theologians, pastors and church office-holders against the introduction of the Aryan paragraph into the 28 Pro ...

'' which grows into Confessing Church

The Confessing Church (german: link=no, Bekennende Kirche, ) was a movement within German Protestantism during Nazi Germany that arose in opposition to government-sponsored efforts to unify all Protestant churches into a single pro-Nazi German E ...

, which reasserts authority of Bible and from which some clergymen oppose regime.

Third (fall 1934 to February 1937)

*Regime tries to bring the Protestant churches under its control by taking charge of church finances and governance structures. *Failure of Müller to unite Protestants in Nazified Church sees Hitler appointHans Kerrl

Hanns Kerrl (11 December 1887 – 14 December 1941) was a German Nazi politician. His most prominent position, from July 1935, was that of Reichsminister of Church Affairs. He was also President of the Prussian Landtag (1932–1933) and head of ...

as Minister for Church Affairs.

*1936, Nazis remove crucifixes in schools. Catholic Bishop of Münster, Clemens von Galen, protests and public demonstrations follow.

*1936 – Confessing Church protest to Hitler against antisemitism, "anti-Christian" tendencies of regime, and interference in church affairs. Hundreds of pastors arrested, funds of the church confiscated, collections forbidden.

Fourth (February 1937 to 1939)

*More open conflict based on "Nazism itself and its anti-Christian worldviews". Regime increases imprisonment of resistant clergy. *March 1937:Pope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI ( it, Pio XI), born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti (; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939), was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to his death in February 1939. He was the first sovereign of Vatican City fro ...

issues ''Mit brennender Sorge

''Mit brennender Sorge'' ( , in English "With deep anxiety") ''On the Church and the German Reich'' is an encyclical of Pope Pius XI, issued during the Nazi Germany, Nazi era on 10 March 1937 (but bearing a date of Passion Sunday, 14 March)." ...

'' encyclical, denouncing aspects of Nazi ideology

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

, protesting regime's violations of Concordat and treatment of Catholics, and abuse of human rights.

* Regime responds with intensification of Church Struggle. Trumped up "immorality trials" against clergy and anti-church propaganda campaign. Christmas 1937 address, Pope tells cardinals "rarely has there been a persecution so grave"

*1 July 1937, Confessing Church banned. Martin Niemöller

Friedrich Gustav Emil Martin Niemöller (; 14 January 18926 March 1984) was a German theologian and Lutheran pastor. He is best known for his opposition to the Nazi regime during the late 1930s and for his widely quoted 1946 poem " First they ca ...

arrested. Theological universities closed, pastors and theologians arrested.

Fifth stage (1939 to 1945)

*More clergy were imprisoned – Clergy Barracks established at Dachau. *July–August 1941 – CardinalClemens August Graf von Galen

Clemens Augustinus Emmanuel Joseph Pius Anthonius Hubertus Marie Graf von Galen (16 March 1878 – 22 March 1946), better known as ''Clemens August Graf von Galen'', was a German count, Bishop of Münster, and cardinal of the Catholic Churc ...

's sermons denounce lawlessness of Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one organi ...

, confiscations of church properties, and Nazi euthanasia. Government takes program underground.

*Clergy were drafted into the military

*Church publications were censored or banned

*Services and functions restricted or banned

*22 March 1942, the German Catholic Bishops issued a pastoral letter on "The Struggle against Christianity and the Church".

*Inspired by Cardinal Clemens August Graf von Galen

Clemens Augustinus Emmanuel Joseph Pius Anthonius Hubertus Marie Graf von Galen (16 March 1878 – 22 March 1946), better known as ''Clemens August Graf von Galen'', was a German count, Bishop of Münster, and cardinal of the Catholic Churc ...

, the White Rose

The White Rose (german: Weiße Rose, ) was a Nonviolence, non-violent, intellectual German resistance to Nazism, resistance group in Nazi Germany which was led by five students (and one professor) at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, ...

group becomes active in 1942; group members are arrested by the Gestapo and executed in 1943.

*Nazi assault on churches and "Christian conscience" motivates many of the July Plot participants in failed 1944 coup against Hitler. Leading clerical resistors Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Dietrich Bonhoeffer (; 4 February 1906 – 9 April 1945) was a German Lutheran pastor, theologian and anti-Nazi dissident who was a key founding member of the Confessing Church. His writings on Christianity's role in the secular world have ...

and Alfred Delp

Alfred Delp (, 15 September 1907 – 2 February 1945) was a German Jesuit priest and philosopher of the German Resistance. A member of the inner Kreisau Circle resistance group, he is considered a significant figure in Catholic resistan ...

are implicated. Both executed in 1945.

Nazi persecution of the Christian churches

Prior to the Reichstag vote for the

Prior to the Reichstag vote for the Enabling Act

An enabling act is a piece of legislation by which a legislative body grants an entity which depends on it (for authorization or legitimacy) the power to take certain actions. For example, enabling acts often establish government agencies to car ...

under which Hitler gained the "temporary" dictatorial powers with which he went on to permanently dismantle the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

, Hitler promised the Reichstag on 23 March 1933, that he would not interfere with the rights of the churches. However, with power secured in Germany, Hitler quickly broke this promise. He divided the Lutheran Church (Germany's main Protestant denomination) and instigated a brutal persecution of the Jehovah's Witnesses. He dishonoured a Concordat signed with the Vatican and permitted a persecution of the Catholic Church in Germany. A special Priests Barracks was established at Dachau Concentration Camp

,

, commandant = List of commandants

, known for =

, location = Upper Bavaria, Southern Germany

, built by = Germany

, operated by = ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS)

, original use = Political prison

, construction ...

for clergy who had opposed the Hitler regime – its occupants were mainly Polish Catholic clergy.

Leading Nazis varied in the importance they attached to the Church Struggle. Kershaw wrote that, to the new Nazi government, Race policy and the 'Church Struggle' were among the most important ideological spheres: "In both areas, the party had no difficulty in mobilizing its activists, whose radicalism in turn forced the government into legislative action. In fact the party leadership often found itself compelled to respond to pressures from below, stirred up by the ''

Leading Nazis varied in the importance they attached to the Church Struggle. Kershaw wrote that, to the new Nazi government, Race policy and the 'Church Struggle' were among the most important ideological spheres: "In both areas, the party had no difficulty in mobilizing its activists, whose radicalism in turn forced the government into legislative action. In fact the party leadership often found itself compelled to respond to pressures from below, stirred up by the ''Gauleiter

A ''Gauleiter'' () was a regional leader of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) who served as the head of a ''Administrative divisions of Nazi Germany, Gau'' or ''Reichsgau''. ''Gauleiter'' was the third-highest Ranks and insignia of the Nazi Party, rank in ...

'' playing their own game, or emanating sometimes from radical activists at a local level". As time went on, anti-clericalism and anti-church sentiment among grass roots party activists "simply couldn't be eradicated" and they could "draw on the verbal violence of party leaders towards the churches for their encouragement.

Hitler himself possessed radical instincts in relation to the continuing conflict with the Catholic and Protestant churches in Germany. Though he occasionally spoke of wanting to delay the Church struggle and was prepared to restrain his anti-clericalism out of political considerations, his "own inflammatory comments gave his immediate underlings all the license they needed to turn up the heat in the 'Church Struggle, confident that they were 'working towards the Fuhrer'".

Bullock wrote that the churches and the army were the only two institutions to retain some independence in Nazi Germany and "among the most courageous demonstrations of opposition during the war were the sermons preached by the Catholic Bishop of Munster and the Protestant Pastor, Dr Niemoller..." but that "Neither the Catholic Church nor the Evangelical Church, however, as institutions, felt it possible to take up an attitude of open opposition to the regime". In the Nazi police state, the ability of the church and its members to oppose Nazi policy was severely restricted. In 1935, when Protestant pastors read a protest statement from the pulpits of Confessing churches, the Nazi authorities briefly arrested over 700 pastors and the Gestapo confiscated copies of Pius XI

Pope Pius XI ( it, Pio XI), born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti (; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939), was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to his death in February 1939. He was the first sovereign of Vatican City from ...

's 1937 anti-Nazi papal encyclical ''Mit brennender Sorge

''Mit brennender Sorge'' ( , in English "With deep anxiety") ''On the Church and the German Reich'' is an encyclical of Pope Pius XI, issued during the Nazi Germany, Nazi era on 10 March 1937 (but bearing a date of Passion Sunday, 14 March)." ...

'' from diocesan offices throughout Germany. For refusing to declare loyalty to the Reich, or be conscripted into the army, Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses is a millenarian restorationist Christian denomination with nontrinitarian beliefs distinct from mainstream Christianity. The group reports a worldwide membership of approximately 8.7 million adherents involved in ...

were declared "enemies", with 6000 of a total population of 30,000 sent to the concentration camps.

Alfred Rosenberg

Alfred Ernst Rosenberg ( – 16 October 1946) was a Baltic German Nazi theorist and ideologue. Rosenberg was first introduced to Adolf Hitler by Dietrich Eckart and he held several important posts in the Nazi government. He was the head of ...

, an "outspoken pagan", held among offices the title of "the Fuehrer's Delegate for the Entire Intellectual and Philosophical Education and Instruction for the National Socialist Party". He also saw Nazism and Christianity as incompatible.http://www.catholiceducation.org/articles/persecution/pch0229.htm In his '' Myth of the Twentieth Century'' (1930), Rosenberg wrote that the main enemies of the Germans were the "Russian Tartars" and "Semites" – with "Semites" including Christians, especially the Catholic Church.

Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 19 ...

, the Nazi Minister for Propaganda, was among the most aggressive anti-church Nazi radicals. Goebbels led the Nazi persecution of the German clergy and, as the war progressed, on the "Church Question", he wrote "after the war it has to be generally solved... There is, namely, an insoluble opposition between the Christian and a heroic-German world view". Worried about the dissention caused by the Kirchenkampf, Hitler told Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 19 ...

in the summer of 1935 he sought "peace with the Churches" – "at least for a period of time". As with the "Jewish question", the radicals nonetheless pushed the church struggle forward, especially in Catholic areas, so that by the winter of 1935–1936 there was growing dissatisfaction with the Nazis in those areas. Kershaw noted that in early 1937, Hitler again told his inner circle that he "did not want a 'Church struggle" at this juncture", he expected "the great world struggle in a few years' time". Nevertheless, Hitler's impatience with the churches "prompted frequent outbursts of hostility. In early 1937 he was declaring that 'Christianity was ripe for destruction' (''Untergang''), and that the Churches must yield to the 'primacy of the state', railing against any compromise with 'the most horrible institution imaginable'."

Martin Bormann

Martin Ludwig Bormann (17 June 1900 – 2 May 1945) was a German Nazi Party official and head of the Nazi Party Chancellery. He gained immense power by using his position as Adolf Hitler's private secretary to control the flow of information ...

became Hitler's private secretary and ''de facto'' "deputy" Führer in April 1941. He was a leading advocate of the Kirchenkampf. Bormann was a rigid guardian of Nazi orthodoxy and saw Christianity and Nazism as "'incompatible,' primarily because the essential elements of Christianity were 'taken over from Judaism.'" He said publicly in 1941 that "National Socialism and Christianity are irreconcilable". Bormann's view of Christianity was epitomized in a confidential memo to ''Gauleiters'' in 1942; it reignited the fight against Christianity which had been in a détente, stating that the power of the churches "must absolutely and finally be broken" as Nazism "was completely incompatible with Christianity."

William Shirer

William Lawrence Shirer (; February 23, 1904 – December 28, 1993) was an American journalist and war correspondent. He wrote ''The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich'', a history of Nazi Germany that has been read by many and cited in scholarly w ...

wrote that the German people were not greatly aroused by the persecution of the churches by the Nazi government. The great majority were not moved to face death or imprisonment for the sake of freedom of worship, being too impressed by Hitler's early foreign policy successes and the restoration of the German economy. Few paused to reflect "that under the leadership of Rosenberg, Bormann and Himmler, who were backed by Hitler, the Nazi regime intended to destroy Christianity in Germany, if it could, and substitute the old paganism of the early tribal Germanic gods and the new paganism of the Nazi extremists."

Because the Nazi Gleichschaltung

The Nazi term () or "coordination" was the process of Nazification by which Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party successively established a system of totalitarian control and coordination over all aspects of German society and societies occupied b ...

policy of forced coordination encountered such forceful opposition from the churches, Hitler decided to postpone the struggle until after the war. During the war, Rosenberg, the party's official ideologist outlined the future envisioned for religion in Germany, with a thirty-point program for the future of the German churches. Among its articles: (1) the National Reich Church of Germany was to claim exclusive control over all churches in the Reich; (5) “the strange and foreign Christian faiths imported into Germany in the ill-omened year 800” were to be exterminated; (7) priests/pastors were to be replaced with National Reich Orators; (13) publication of the Bible was to cease; (14) ''Mein Kampf

(; ''My Struggle'' or ''My Battle'') is a 1925 autobiographical manifesto by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler. The work describes the process by which Hitler became antisemitic and outlines his political ideology and future plans for Germ ...

'' was to be considered the foremost source of ethics; (18) crucifixes, Bibles and saints to be removed from altars; (19) ''Mein Kampf'' was to be placed on altars "to the German nation and therefore to God the most sacred book"; (30) the Christian cross to be removed from all churches and replaced with the swastika. Albeit an investigation led by the Gestapo in 1941 in response to President Franklin D. Roosevelt's accusation of a Nazi conspiracy "to abolish all existing religions -- Catholic, Protestant, Mohammedan, Hindu, Buddhist, and Jewish alike" and impose a nazified international church established that the creator of the thirty-point program for the future of the German churches was Fritz Bildt, a fanatical Nazi and known troublemaker, rather than Alfred Rosenberg, who in 1937 tried to proclaim the program in the Garrison Church in Stettin shortly before the divine service began, he was forcibly removed from the pulpit and fined RMKS 500, having admitted to being the sole author and distributor of the program.

Catholic Church

A threatening, though initially mainly sporadic persecution of theCatholic Church in Germany

, native_name_lang = de

, image = Hohe_Domkirche_St._Petrus.jpg

, imagewidth = 200px

, alt =

, caption = Cologne Cathedral, Cologne

, abbreviation =

, type = Nati ...

followed the Nazi takeover. Hitler moved quickly to eliminate Political Catholicism

The Catholic Church and politics concerns the interplay of Catholicism with religious, and later secular, politics. Historically, the Church opposed liberal ideas such as democracy, freedom of speech, and the separation of church and state unde ...

. Two thousand functionaries of the Bavarian People's Party

The Bavarian People's Party (german: Bayerische Volkspartei; BVP) was the Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria ...

were rounded up by police in late June 1933, and it, along with the national Catholic Centre Party

The Centre Party (german: Zentrum), officially the German Centre Party (german: link=no, Deutsche Zentrumspartei) and also known in English as the Catholic Centre Party, is a Catholic political party in Germany, influential in the German Empire ...

, ceased to exist in early July. Vice Chancellor Franz von Papen

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, Erbsälzer zu Werl und Neuwerk (; 29 October 18792 May 1969) was a German conservative politician, diplomat, Prussian nobleman and General Staff officer. He served as the chancellor of Germany i ...

meanwhile negotiated the ''Reichskonkordat

The ''Reichskonkordat'' ("Concordat between the Holy See and the German Reich") is a treaty negotiated between the Vatican and the emergent Nazi Germany. It was signed on 20 July 1933 by Cardinal Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli, who later be ...

'' treaty with the Vatican, which prohibited clergy from participating in politics. Kershaw wrote that the Vatican was anxious to reach agreement with the new government, despite "continuing molestation of Catholic clergy, and other outrages committed by Nazi radicals against the Church and its organisations".

Concordat

The Concordat was signed at the Vatican on 20 July 1933, by Germany's Deputy Reich ChancellorFranz von Papen

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, Erbsälzer zu Werl und Neuwerk (; 29 October 18792 May 1969) was a German conservative politician, diplomat, Prussian nobleman and General Staff officer. He served as the chancellor of Germany i ...

, and Cardinal Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli

Pope Pius XII ( it, Pio XII), born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli (; 2 March 18769 October 1958), was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death in October 1958. Before his e ...

(later Pope Pius XII). In his 1937 anti-Nazi encyclical, Pope Pius XI said that the Holy See had signed the Concordat "In spite of many serious misgivings" and in the hope it might "safeguard the liberty of the church in her mission of salvation in Germany". The treaty consisted of 34 articles and a supplementary protocol. Article 1 guaranteed "freedom of profession and public practice of the Catholic religion" and acknowledged the right of the church to regulate its own affairs. Within three months of the signing of the document, Cardinal Adolf Bertram

Adolf Bertram (14 March 1859 – 6 July 1945) was archbishop of Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland) and a cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church.

Early life

Adolf Bertram was born in Hildesheim, Royal Prussian Province of Hanover (now Lower Saxony), ...

, head of the German Catholic Bishops Conference, was writing in a pastoral letter of "grievous and gnawing anxiety" with regard to the government's actions towards Catholic organizations, charitable institutions, youth groups, press, Catholic Action

Catholic Action is the name of groups of lay Catholics who advocate for increased Catholic influence on society. They were especially active in the nineteenth century in historically Catholic countries under anti-clerical regimes such as Spain, Ita ...

and the mistreatment of Catholics for their political beliefs. According to Paul O'Shea, Hitler had a "blatant disregard" for the Concordat, and its signing was to him merely a first step in the "gradual suppression of the Catholic Church in Germany". Anton Gill

Anton Gill (born in 1948) is a British writer of historical fiction and nonfiction. He won the H. H. Wingate Award for non-fiction for ''The Journey Back From Hell'', an account of the lives of survivors after their liberation from Nazi concentr ...

wrote that "with his usual irresistible, bullying technique, Hitler then proceeded to take a mile where he had been given an inch" and closed all Catholic institutions whose functions weren't strictly religious:

The Concordat, wrote William Shirer

William Lawrence Shirer (; February 23, 1904 – December 28, 1993) was an American journalist and war correspondent. He wrote ''The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich'', a history of Nazi Germany that has been read by many and cited in scholarly w ...

, "was hardly put to paper before it was being broken by the Nazi Government". On 25 July, the Nazis promulgated their sterilization law, an offensive policy in the eyes of the Catholic Church. Five days later, moves began to dissolve the Catholic Youth League. Clergy, nuns and lay leaders began to be targeted, leading to thousands of arrests over the ensuing years, often on trumped up charges of currency smuggling or "immorality".

Ongoing "struggle"

In Hitler's bloodynight of the long knives

The Night of the Long Knives (German: ), or the Röhm purge (German: ''Röhm-Putsch''), also called Operation Hummingbird (German: ''Unternehmen Kolibri''), was a purge that took place in Nazi Germany from 30 June to 2 July 1934. Chancellor Ad ...

purge of 1934, Erich Klausener

Erich Klausener (25 January 1885 – 30 June 1934) was a German Roman Catholic, Catholic politician and Catholic martyr in the "Night of the Long Knives", a purge that took place in Nazi Germany from 30 June to 2 July 1934, when the Nazi regime c ...

, the head of Catholic Action, was assassinated by the Gestapo. Catholic publications were shut down. The Gestapo began to violate the sanctity of the confessional.

In January 1934, Hitler appointed

In January 1934, Hitler appointed Alfred Rosenberg

Alfred Ernst Rosenberg ( – 16 October 1946) was a Baltic German Nazi theorist and ideologue. Rosenberg was first introduced to Adolf Hitler by Dietrich Eckart and he held several important posts in the Nazi government. He was the head of ...

as the cultural and educational leader of the Reich. Rosenberg was a neo-pagan and notoriously anti-Catholic. In his '' Myth of the Twentieth Century'' (1930), Rosenberg had described the Catholic Church as one of the main enemies of Nazism. The church responded on 16 February 1934 with the banning of Rosenberg's book. The Sanctum Officium recommended that Rosenberg's book be put on the ''Index Librorum Prohibitorum

The ''Index Librorum Prohibitorum'' ("List of Prohibited Books") was a list of publications deemed heretical or contrary to morality by the Sacred Congregation of the Index (a former Dicastery of the Roman Curia), and Catholics were forbidden ...

'' (forbidden books list of the Catholic Church) for scorning and rejecting "all dogmas of the Catholic Church, indeed the very fundamentals of the Christian religion". Clemens August Graf von Galen

Clemens Augustinus Emmanuel Joseph Pius Anthonius Hubertus Marie Graf von Galen (16 March 1878 – 22 March 1946), better known as ''Clemens August Graf von Galen'', was a German count, Bishop of Münster, and cardinal of the Catholic Churc ...

, the Bishop of Münster

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

, derided the neo-pagan theories of Rosenberg as perhaps no more than "an occasion for laughter in the educated world", but warned that "his immense importance lies in the acceptance of his basic notions as the authentic philosophy of National Socialism and in his almost unlimited power in the field of German education. Herr Rosenberg must be taken seriously if the German situation is to be understood."

Under Nazi youth leader Baldur von Schirach

Baldur Benedikt von Schirach (9 May 1907 – 8 August 1974) was a German politician who is best known for his role as the Nazi Party national youth leader and head of the Hitler Youth from 1931 to 1940. He later served as ''Gauleiter'' and ''Re ...

, Catholic youth organizations were disbanded and Catholic children corralled into the Hitler Youth

The Hitler Youth (german: Hitlerjugend , often abbreviated as HJ, ) was the youth organisation of the Nazi Party in Germany. Its origins date back to 1922 and it received the name ("Hitler Youth, League of German Worker Youth") in July 1926. ...

. Pope Pius XI issued a message to the youth of Germany on 2 April 1934, noting propaganda and pressure being exerted to point German youth "away from Christ and back to paganism". The Pope again condemned the new paganism to 5,000 German pilgrims in Rome in May and in other addresses later that year.

In January 1935, Nazi interior minister Wilhelm Frick

Wilhelm Frick (12 March 1877 – 16 October 1946) was a prominent German politician of the Nazi Party (NSDAP), who served as Reich Minister of the Interior in Adolf Hitler's cabinet from 1933 to 1943 and as the last governor of the Protectorate ...

urged "putting an end to Church influence over public life". In April, the daily publication of religious papers was banned and soon after, censorship of weekly periodicals was introduced. The American National Catholic Welfare Conference The National Catholic Welfare Council (NCWC) was the annual meeting of the American Catholic hierarchy and its standing secretariat; it was established in 1919 as the successor to the emergency organization, the National Catholic War Council.

It co ...

complained that anti-church songs were chanted by Hitler Youth and "anti-Christian slogans were chanted from trucks, which bore on their sides scurrilous cartoons of priests and nuns" while Catholic Youth organizations were "accused of the palpable absurdity of communist plotting". On 12 May, members of the Hitler Youth attacked Caspar Klein, the Archbishop of Paderborn.

Goering issued a decree against Political Catholicism

The Catholic Church and politics concerns the interplay of Catholicism with religious, and later secular, politics. Historically, the Church opposed liberal ideas such as democracy, freedom of speech, and the separation of church and state unde ...

in July. In August, Nazi stormtroopers held anti-clerical protests in Munich and Freiberg-im-Breisgau. Nazi propagandist Julius Streicher

Julius Streicher (12 February 1885 – 16 October 1946) was a member of the Nazi Party, the ''Gauleiter'' (regional leader) of Franconia and a member of the '' Reichstag'', the national legislature. He was the founder and publisher of the virul ...

accused clergy and nuns of sexual perversion. The "morality trials" of Catholic clergy and nuns began in the summer of 1935 and the "threat of criminal prosecution on charges designed by the Propaganda Ministry as a goad to drive the clergy to accept the subversion of Christian teachings in the Reich". In the 1936 campaign against the monasteries and convents, the authorities charged 276 members of religious orders with the offence of "homosexuality".

Under Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich ( ; ; 7 March 1904 – 4 June 1942) was a high-ranking German SS and police official during the Nazi era and a principal architect of the Holocaust.

He was chief of the Reich Security Main Office (inclu ...

and Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

, the Security Police, and the SD were responsible for suppressing internal and external enemies of the Nazi state. Among those enemies were "political churches" – such as Lutheran and Catholic clergy who opposed the Hitler regime. Such dissidents were arrested and sent to concentration camps. According to Himmler biographer Peter Longerich

Peter Longerich (born 1955) is a German professor of history and German historian. He is regarded by fellow historians, including Ian Kershaw, Richard Evans, Timothy Snyder, Mark Roseman and Richard Overy, as one of the leading German authori ...

, Himmler was vehemently opposed to Christian sexual morality and the "principle of Christian mercy", both of which he saw as a dangerous obstacle to his planned battle with "subhumans". In 1937 he wrote:

Himmler saw the main task of his ''Schutzstaffel

The ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS; also stylized as ''ᛋᛋ'' with Armanen runes; ; "Protection Squadron") was a major paramilitary organization under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany, and later throughout German-occupied Europe d ...

'' (SS) organization to be that of "acting as the vanguard in overcoming Christianity and restoring a 'Germanic' way of living" in order to prepare for the coming conflict between "humans and subhumans": Longerich wrote that, while the Nazi movement as a whole launched itself against Jews and Communists, "by linking de-Christianization with re-Germanization, Himmler had provided the SS with a goal and purpose all of its own." He set about making his SS the focus of a "cult of the Teutons".

Goebbels noted the mood of Hitler in his diary on 25 October 1936: "Trials against the Catholic Church temporarily stopped. Possibly wants peace, at least temporarily. Now a battle with Bolshevism. Wants to speak with Faulhaber". On 4 November 1936, Hitler met Faulhaber. Hitler spoke for the first hour, then Faulhaber told him that the Nazi government had been waging war on the church for three years – 600 religious teachers had lost their jobs in Bavaria alone – and the number was set to rise to 1700 and the government had instituted laws the church could not accept – like the sterilization of criminals and the handicapped. While the Catholic Church respected the notion of authority, nevertheless, "when your officials or your laws offend Church dogma or the laws of morality, and in so doing offend our conscience, then we must be able to articulate this as responsible defenders of moral laws". Hitler told Faulhaber that the radical Nazis could not be contained until there was peace with the church and that either the Nazis and the church would fight Bolshevism together, or there would be war against the church. Kershaw cites the meeting as an example of Hitler's ability to "pull the wool over the eyes even of hardened critics" for "Faulhaber – a man of sharp acumen, who had often courageously criticized the Nazi attacks on the Catholic Church – went away convinced that Hitler was deeply religious".

''Mit brennender Sorge''

By early 1937, the church hierarchy in Germany, which had initially attempted to co-operate with the new government, had become highly disillusioned. In March,

By early 1937, the church hierarchy in Germany, which had initially attempted to co-operate with the new government, had become highly disillusioned. In March, Pope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI ( it, Pio XI), born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti (; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939), was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to his death in February 1939. He was the first sovereign of Vatican City fro ...

issued the ''Mit brennender Sorge

''Mit brennender Sorge'' ( , in English "With deep anxiety") ''On the Church and the German Reich'' is an encyclical of Pope Pius XI, issued during the Nazi Germany, Nazi era on 10 March 1937 (but bearing a date of Passion Sunday, 14 March)." ...

'' (german: "With burning concern") encyclical. The Pope asserted the inviolability of human rights and expressed deep concern at the Nazi regime's flouting of the 1933 Concordat, its treatment of Catholics and abuse of Christian values. It accused the government of "systematic hostility leveled at the Church" and of sowing the "tares of suspicion, discord, hatred, calumny, of secret and open fundamental hostility to Christ and His Church" and Pius noted on the horizon the "threatening storm clouds" of religious wars of extermination over Germany.

The Vatican had the text smuggled into Germany and printed and distributed in secret. Written in German, not the usual Latin, it was read from the pulpits of all German Catholic churches on one of the church's busiest Sundays, Palm Sunday

Palm Sunday is a Christian moveable feast that falls on the Sunday before Easter. The feast commemorates Christ's triumphal entry into Jerusalem, an event mentioned in each of the four canonical Gospels. Palm Sunday marks the first day of Holy ...

. According to Gill, "Hitler was beside himself with rage. Twelve presses were seized, and hundreds of people sent either to prison or the camps." This despite Article 4 of the Concordat giving a guarantee of freedom of correspondence between the Vatican and the German clergy.

The Nazis responded with, an intensification of the Church Struggle, beginning around April. Goebbels noted heightened verbal attacks on the clergy from Hitler in his diary and wrote that Hitler had approved the start of trumped up "immorality trials" against clergy and anti-church propaganda campaign. Goebbels' orchestrated attack included a staged "morality trial" of 37 Franciscans.

In his Christmas Eve 1937 address, Pope Pius XI told the College of Cardinals, that despite what "some people" had been saying, "In Germany, in fact, there is religious persecution ... indeed rarely has there been a persecution so grave, so terrible, so painful, so sad in its deep effects ... Our protest therefore could not be more explicit or more resolute before the whole world".

Prelude to World War II

In March 1938, Nazi Minister of StateAdolf Wagner

Adolf Wagner (1 October 1890 – 12 April 1944) was a Nazi Party official and politician who served as the Party's ''Gauleiter'' in Munich and as the powerful Interior Minister of Bavaria throughout most of the Third Reich.

Early years

Born in ...

spoke of the need to continue the fight against Political Catholicism and Alfred Rosenberg

Alfred Ernst Rosenberg ( – 16 October 1946) was a Baltic German Nazi theorist and ideologue. Rosenberg was first introduced to Adolf Hitler by Dietrich Eckart and he held several important posts in the Nazi government. He was the head of ...

said that the churches of Germany "as they exist at present, must vanish from the life of our people". In the space of a few months, Bishop Johannes Baptista Sproll of Rothenberg, Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber

Michael Cardinal ''Ritter'' von Faulhaber (5 March 1869 – 12 June 1952) was a German Catholic prelate who served as Archbishop of Munich for 35 years, from 1917 to his death in 1952. Created Cardinal in 1921, von Faulhaber criticized the Weima ...

of Munich, and Cardinal Theodor Innitzer

Theodor Innitzer (25 December 1875 – 9 October 1955) was Archbishop of Vienna and a cardinal of the Catholic Church.

Early life

Innitzer was born in Neugeschrei (Nové Zvolání), part of the town Weipert (Vejprty) in Bohemia, at that time Au ...

of Vienna were physically attacked by Nazis.

After initially offering support to the Anschluss, Austria's Innitzer became a critic of the Nazis and was subject to violent intimidation from them. With power secured in Austria, the Nazis repeated their persecution of the church and in October, a Nazi mob ransacked Innitzer's residence, after he had denounced Nazi persecution of the church. ''L'Osservatore Romano

''L'Osservatore Romano'' (, 'The Roman Observer') is the daily newspaper of Vatican City State which reports on the activities of the Holy See and events taking place in the Catholic Church and the world. It is owned by the Holy See but is not a ...

'' reported on 15 October that Hitler Youth and the SA had gathered at Innitzer's cathedral during a service Catholic Youth and started "counter-shouts and whistlings: 'Down with Innitzer! Our faith is Germany'". The mob later gathered at the cardinal's residence and the following day stoned the building, broke in and ransacked it – bashing a secretary unconscious, and storming another house of the cathedral curia and throwing its curate out the window. The American National Catholic Welfare Conference The National Catholic Welfare Council (NCWC) was the annual meeting of the American Catholic hierarchy and its standing secretariat; it was established in 1919 as the successor to the emergency organization, the National Catholic War Council.

It co ...

wrote that Pope Pius, "again protested against the violence of the Nazis, in language recalling Nero and Judas the Betrayer, comparing Hitler with Julian the Apostate."

On 10 February 1939, Pope Pius XI died. Eugenio Pacelli was elected his successor three weeks later and became Pius XII

Pius ( , ) Latin for "pious", is a masculine given name. Its feminine form is Pia.

It may refer to:

People Popes

* Pope Pius (disambiguation)

* Antipope Pius XIII (1918-2009), who led the breakaway True Catholic Church sect

Given name

* Pius B ...

. Europe was on the brink of World War II.

World War II

''Summi Pontificatus

''Summi Pontificatus'' is an encyclical of Pope Pius XII published on 20 October 1939. The encyclical is subtitled "on the unity of human society". It was the first encyclical of Pius XII and was seen as setting "a tone" for his papacy. It c ...

'' ("On the Limitations of the Authority of the State"), issued 20 October 1939, was the first papal encyclical issued by Pope Pius XII, and established some of the themes of his papacy. During the drafting of the letter, the Second World War commenced with the Nazi/Soviet invasion of Catholic Poland. Couched in diplomatic language, Pius endorses Catholic resistance, and states his disapproval of the war, racism, anti-semitism, the Nazi/Soviet invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week aft ...

and the persecutions of the church.

In March 1941, Vatican Radio decried the wartime position of the Catholic Church in Germany: "The religious situation in Germany is pathetic. All young men that feel their vocation is to take Holy Orders must forego this desire. The number of monasteries and convents which have been dissolved has become even larger. The development and maintenance of the Christian life has been rendered difficult. All that remains of the once great Catholic press in Germany are a few Parish magazines. The threat of a national religion is looming increasingly over all religious life. This national religion is based solely on the Fuhrer's will".

On 26 July 1941, Bishop August Graf von Galen wrote to the government to complain "The Secret Police has continued to rob the property of highly respected German men and women merely because they belonged to Catholic orders". Often Galen directly protested to Hitler over violations of the Concordat. When in 1936, Nazis removed crucifixes in school, protest by Galen led to public demonstration. Like Konrad von Preysing

Johann Konrad Maria Augustin Felix, Graf von Preysing Lichtenegg-Moos (30 August 1880 – 21 December 1950) was a German prelate of the Roman Catholic Church. Considered a significant figure in Catholic resistance to Nazism, he served as ...

, he assisted with the drafting of the 1937 papal encyclical. His three powerful sermons of July and August 1941 earned him the nickname of the "Lion of Munster". The sermons were printed and distributed illegally. He denounced the lawlessness of the Gestapo, the confiscations of church properties and the cruel program of Nazi euthanasia. He attacked the Gestapo for seizing church properties and converting them to their own purposes – including use as cinemas and brothels.

On 26 June 1941, the German bishops drafted a pastoral letter from their Fulda Conference

The German Bishops' Conference (german: Deutsche Bischofskonferenz) is the episcopal conference of the bishops of the Roman Catholic dioceses in Germany. Members include diocesan bishops, coadjutors, auxiliary bishops, and diocesan administrat ...

, to be read from all pulpits on 6 July: "Again and again have the bishops brought their justified claims and complaints before the proper authorities... Through this pastoral declaration the Bishops want you to see the real situation of the church". The bishops wrote that the church faced "restrictions and limitations put on the teaching of their religion and on church life" and of great obstacles in the fields of Catholic education, freedom of service and religious festivals, the practice of charity by religious orders and the role of preaching morals. Catholic presses had been silenced and kindergartens closed and religious instruction in schools nearly stamped out:

Letter of the bishops

The following year, on 22 March 1942, the German bishops issued a pastoral letter on "The Struggle against Christianity and the Church": The letter launched a defence of human rights and the rule of law and accused the Reich Government of "unjust oppression and hated struggle against Christianity and the Church", despite the loyalty of German Catholics to the Fatherland, and brave service of Catholics soldiers. It accused the regime of seeking to rid Germany of Christianity: The letter outlined serial breaches of the 1933 Concordat, reiterated complaints of the suffocation of Catholic schooling, presses and hospitals and said that the "Catholic faith has been restricted to such a degree that it has disappeared almost entirely from public life" and even worship within churches in Germany "is frequently restricted or oppressed", while in the conquered territories (and even in the Old Reich), churches had been "closed by force and even used for profane purposes". The freedom of speech of clergymen had been suppressed and priests were being "watched constantly" and punished for fulfilling "priestly duties" and incarcerated in Concentration camps without legal process. Religious orders had been expelled from schools, and their properties seized, while seminaries had been confiscated "to deprive the Catholic priesthood of successors". The bishops denounced the Nazi euthanasia program and declared their support for human rights and personal freedom under God and "just laws" of all people:Protestant churches

Kershaw wrote that the subjugation of the Protestant churches proved more difficult than Hitler had envisaged. With 28 separate regional churches, his bid to create a unified Reich Church through ''

Kershaw wrote that the subjugation of the Protestant churches proved more difficult than Hitler had envisaged. With 28 separate regional churches, his bid to create a unified Reich Church through ''Gleichschaltung

The Nazi term () or "coordination" was the process of Nazification by which Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party successively established a system of totalitarian control and coordination over all aspects of German society and societies occupied b ...

'' ultimately failed, and Hitler became uninterested in supporting the so-called "German Christians

Christianity is the largest religion in Germany. It was introduced to the area of modern Germany by 300 AD, while parts of that area belonged to the Roman Empire, and later, when Franks and other Germanic tribes converted to Christianity from t ...

" Nazi-aligned movement. Historian Susannah Heschel

Susannah Heschel (born 15 May 1956) is an American scholar and the Eli M. Black Distinguished Professor of Jewish Studies at Dartmouth College. The author and editor of numerous books and articles, she is a Guggenheim Fellow and the recipient of ...

wrote that the ''Kirchenkampf'' is "sometimes mistakenly understood as referring to the Protestant churches' resistance to National Socialism, but the term in fact refers to the internal dispute between members of the ''Bekennende Kirche'' Confessing Church

The Confessing Church (german: link=no, Bekennende Kirche, ) was a movement within German Protestantism during Nazi Germany that arose in opposition to government-sponsored efforts to unify all Protestant churches into a single pro-Nazi German E ...

and members of the azi-backed''Deutsche Christen'' German Christians

Christianity is the largest religion in Germany. It was introduced to the area of modern Germany by 300 AD, while parts of that area belonged to the Roman Empire, and later, when Franks and other Germanic tribes converted to Christianity from t ...

for control of the Protestant church."

In 1933, the "German Christians" wanted Nazi doctrines on race and leadership to be applied to a Reich Church but had only around 3,000 of Germany's 17,000 pastors. In July, church leaders submitted a constitution for a Reich Church, which the Reichstag approved. The Church Federation proposed the well-qualified Pastor Friedrich von Bodelschwingh to be the new Reich Bishop, but Hitler endorsed his friend Ludwig Müller

Johan Heinrich Ludwig Müller (23 June 1883 – 31 July 1945) was a German theologian, a Lutheran pastor, and leading member of the pro-Nazi "German Christians" (german: Deutsche Christen) faith movement. In 1933 he was appointed by the Nazi go ...

, a Nazi and former naval chaplain, to serve as Reich Bishop. The Nazis terrorized supporters of Bodelschwingh, and dissolved various church organizations, ensuring the election of Muller as Reich Bishop. But Müller's heretical views against Paul the Apostle

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

and the Semitic origins of Christ and the Bible quickly alienated sections of the Protestant church. Pastor Martin Niemöller

Friedrich Gustav Emil Martin Niemöller (; 14 January 18926 March 1984) was a German theologian and Lutheran pastor. He is best known for his opposition to the Nazi regime during the late 1930s and for his widely quoted 1946 poem " First they ca ...

responded with the ''Pastors Emergency League'' which re-affirmed the Bible. The movement grew into the Confessing Church

The Confessing Church (german: link=no, Bekennende Kirche, ) was a movement within German Protestantism during Nazi Germany that arose in opposition to government-sponsored efforts to unify all Protestant churches into a single pro-Nazi German E ...

, from which some clergymen opposed the Nazi regime.

By 1934, the Confessing Church had declared itself the legitimate Protestant Church of Germany. Despite his closeness to Hitler, Müller had failed to unite Protestantism behind the Nazi Party. In response to the regime's attempt to establish a state church, in March 1935, the Confessing Church Synod announced:

The Nazis response to this synod announcement was to arrest 700 Confessing pastors. Müller resigned. To instigate a new effort at coordinating the Protestant churches, Hitler appointed another friend, Hans Kerrl

Hanns Kerrl (11 December 1887 – 14 December 1941) was a German Nazi politician. His most prominent position, from July 1935, was that of Reichsminister of Church Affairs. He was also President of the Prussian Landtag (1932–1933) and head of ...

to the position of Minister for Church Affairs. A relative moderate, Kerrl initially had some success in this regard, but amid continuing protests by the Confessing Church against Nazi policies, he accused churchmen of failing to appreciate the Nazi doctrine of "Race, blood and soil" and gave the following explanation of the Nazi conception of "Positive Christianity

Positive Christianity (german: Positives Christentum) was a movement within Nazi Germany which promoted the belief that the racial purity of the German people should be maintained by mixing racialistic Nazi ideology with either fundamental or s ...

", telling a group of submissive clergy:

At the end of 1935, the Nazis arrested 700 Confessing Church pastors. When in May 1936, the Confessing Church sent Hitler a memorandum courteously objecting to the "anti-Christian" tendencies of his regime, condemning anti-Semitism and asking for an end to interference in church affairs. Paul Berben wrote, "A Church envoy was sent to Hitler to protest against the religious persecutions, the concentration camps, and the activities of the Gestapo, and to demand freedom of speech, particularly in the press." The Nazi Minister of the Interior, Wilhelm Frick

Wilhelm Frick (12 March 1877 – 16 October 1946) was a prominent German politician of the Nazi Party (NSDAP), who served as Reich Minister of the Interior in Adolf Hitler's cabinet from 1933 to 1943 and as the last governor of the Protectorate ...

responded harshly. Hundreds of pastors were arrested, Dr Weissler, a signatory to the memorandum, was killed at Sachsenhausen concentration camp

Sachsenhausen () or Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg was a German Nazi concentration camp in Oranienburg, Germany, used from 1936 until April 1945, shortly before the defeat of Nazi Germany in May later that year. It mainly held political prisoners ...

and the funds of the church were confiscated and collections forbidden. Church resistance stiffened and by early 1937, Hitler had abandoned his hope of uniting the Protestant churches.

The Confessing Church was banned on 1 July 1937. Niemöller was arrested by the Gestapo and sent to the concentration camps. He remained mainly at Dachau until the fall of the regime. Theological universities were closed, and other pastors and theologians arrested.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Dietrich Bonhoeffer (; 4 February 1906 – 9 April 1945) was a German Lutheran pastor, theologian and anti-Nazi dissident who was a key founding member of the Confessing Church. His writings on Christianity's role in the secular world have ...

, another leading spokesman for the Confessing Church, was from the outset a critic of the Hitler regime's racism and became active in the German resistance – calling for Christians to speak out against Nazi atrocities. Arrested in 1943, he was implicated in the 1944 July Plot to assassinate Hitler and executed.

Another critic of the Nazi regime was Eberhard Arnold, a theologian who founded the Bruderhof. The Bruderhof refused to pledge allegiance to the Fuhrer, and refused to join the army. The community was raided and placed under surveillance in 1933, and then raided again in 1937 and shut down. Members were given 24 hours to leave the country.

The Nazi policy of interference in Protestantism did not achieve its aims. A majority of German Protestants sided neither with ''Deutsche Christen'', nor with the Confessing Church. Both groups also faced significant internal disagreements and division. Mary Fulbrook wrote in her history of Germany:

Long-term plans

Some historians maintain that Hitler's goal in the ''Kirchenkampf'' entailed not only ideological struggle, but ultimately the eradication of the church. Other historians maintain no such plan existed.Alan Bullock

Alan Louis Charles Bullock, Baron Bullock, (13 December 1914 – 2 February 2004) was a British historian. He is best known for his book '' Hitler: A Study in Tyranny'' (1952), the first comprehensive biography of Adolf Hitler, which influence ...

wrote that "once the war was over, itlerpromised himself, he would root out and destroy the influence of the Christian churches, but until then he would be circumspect". According to the ''Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various time ...

'', Hitler believed Christianity and Nazism were "incompatible" and intended to replace Christianity with a "racist form of warrior paganism".

See also

*Away from Rome!

''Away from Rome!'' (german: Los-von-Rom-Bewegung) was a religious movement founded in Austria by the Pan-German politician Georg Ritter von Schönerer aimed at conversion of all the Roman Catholic German-speaking population of Austria to Lutheran ...

*Catholic Church and Nazi Germany

Popes Pius XI (1922–1939) and Pius XII (1939–1958) led the Catholic Church during the rise and fall of Nazi Germany. Around a third of Germans were Catholic in the 1930s, most of them lived in Southern Germany; Protestants dominated the no ...

*Catholic resistance to Nazi Germany

*Christmas in Nazi Germany

*''Gottgläubig''

*''Mit brennender Sorge

''Mit brennender Sorge'' ( , in English "With deep anxiety") ''On the Church and the German Reich'' is an encyclical of Pope Pius XI, issued during the Nazi Germany, Nazi era on 10 March 1937 (but bearing a date of Passion Sunday, 14 March)." ...

''

*''The Ninth Day''

*Persecution of Jehovah's Witnesses in Nazi Germany

*

*Religion in Nazi Germany

*Religious aspects of Nazism

*White Rose

The White Rose (german: Weiße Rose, ) was a Nonviolence, non-violent, intellectual German resistance to Nazism, resistance group in Nazi Germany which was led by five students (and one professor) at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, ...

References

Footnotes

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{Use dmy dates, date=January 2019 Kirchenkampf,