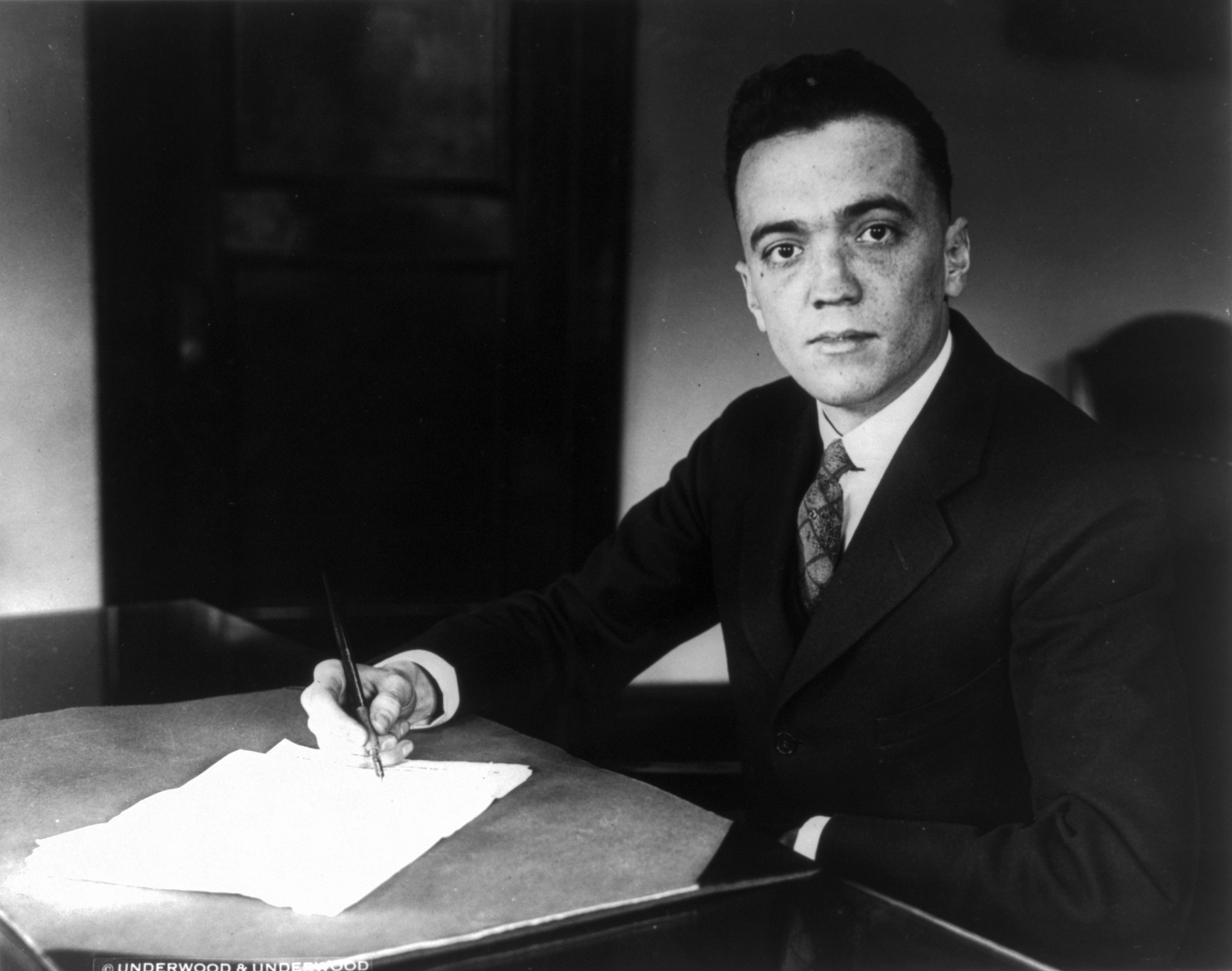

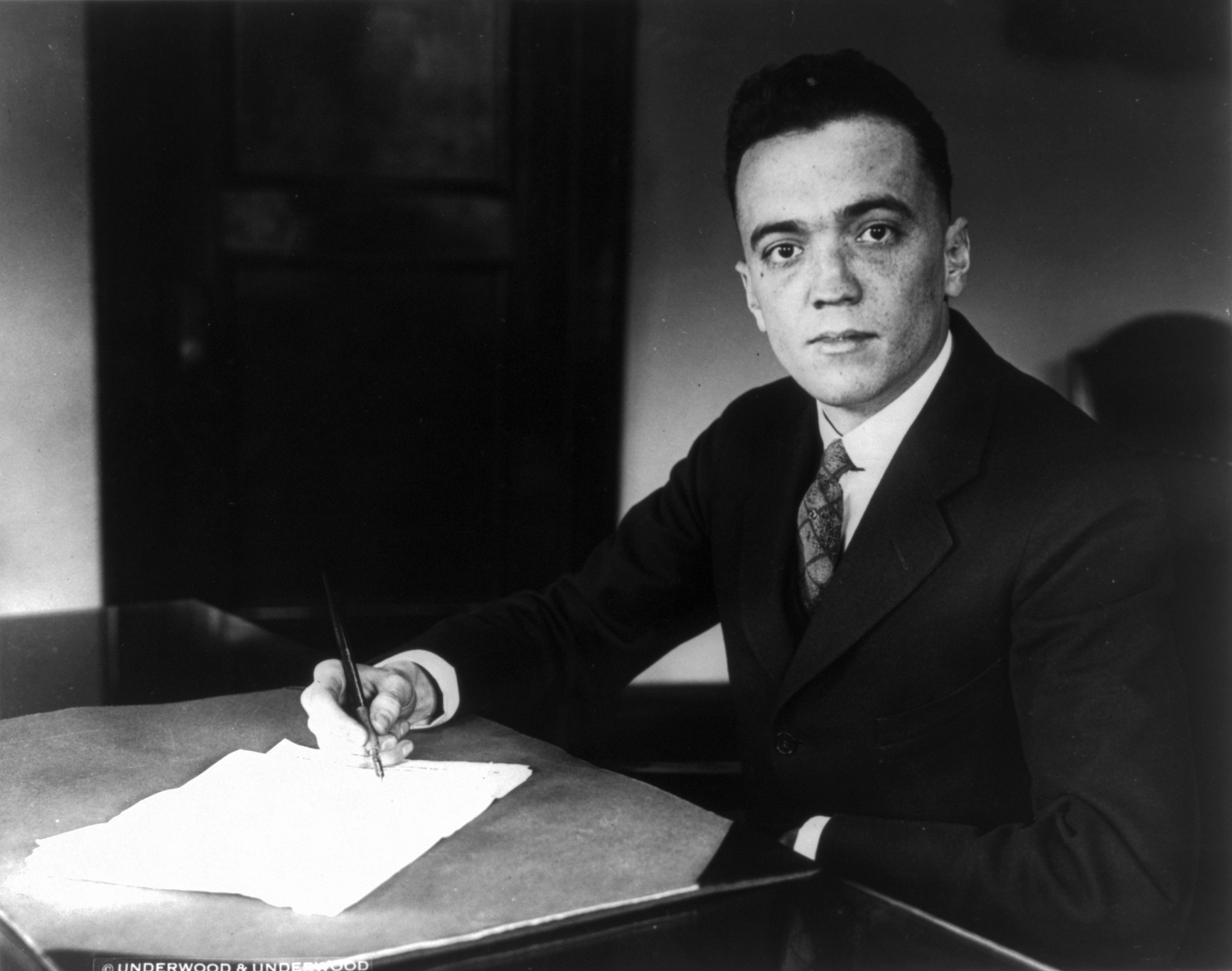

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American attorney and

law enforcement

Law enforcement is the activity of some members of the government or other social institutions who act in an organized manner to enforce the law by investigating, deterring, rehabilitating, or punishing people who violate the rules and norms gove ...

administrator who served as the fifth and final

director of the Bureau of Investigation (BOI) and the first

director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation is the head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), a United States federal law enforcement agency, and is responsible for its day-to-day operations. The FBI director is appointed for a ...

(FBI). President

Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States, serving from 1923 to 1929. A Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer from Massachusetts, he previously ...

first appointed Hoover as director of the BOI, the predecessor to the

FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

, in 1924. After 11 years in the post, Hoover became instrumental in founding the FBI in June 1935, where he remained as director for an additional 37 years until his death in May 1972 – serving a total of 48 years leading both the BOI and the FBI under eight Presidents.

Hoover expanded the FBI into a larger crime-fighting agency and instituted a number of modernizations to policing technology, such as a centralized

fingerprint

A fingerprint is an impression left by the friction ridges of a human finger. The recovery of partial fingerprints from a crime scene is an important method of forensic science. Moisture and grease on a finger result in fingerprints on surfa ...

file and

forensic

Forensic science combines principles of law and science to investigate criminal activity. Through crime scene investigations and laboratory analysis, forensic scientists are able to link suspects to evidence. An example is determining the time and ...

laboratories. Hoover also established and expanded a national

blacklist

Blacklisting is the action of a group or authority compiling a blacklist of people, countries or other entities to be avoided or distrusted as being deemed unacceptable to those making the list; if people are on a blacklist, then they are considere ...

, referred to as the

FBI Index or Index List.

Later in life and after his death, Hoover became a controversial figure as evidence of his secretive

abuses of power began to surface. He was also found to have routinely violated both the FBI's own policies and the very laws which the FBI was charged with enforcing, to have used the FBI to harass and sabotage political dissidents, and to have extensively collected information on officials and private citizens using illegal surveillance, wiretapping, and burglaries.

[

] Hoover consequently amassed a great deal of power and was able to intimidate and threaten high-ranking political figures.

[

]

Early life and education

Hoover was born on New Year's Day 1895 in Washington, D.C., to

German American

German Americans (, ) are Americans who have full or partial German ancestry.

According to the United States Census Bureau's figures from 2022, German Americans make up roughly 41 million people in the US, which is approximately 12% of the pop ...

Anna Marie (''née'' Scheitlin; 1860–1938) and Dickerson Naylor Hoover (1856–1921), chief of the printing division of the

United States Coast and Geodetic Survey

The United States Coast and Geodetic Survey ( USC&GS; known as the Survey of the Coast from 1807 to 1836, and as the United States Coast Survey from 1836 until 1878) was the first scientific agency of the Federal government of the United State ...

, formerly a plate maker for the same organization. Dickerson Hoover was of English and German ancestry. Hoover's maternal great-uncle, John Hitz, was a

Swiss

Swiss most commonly refers to:

* the adjectival form of Switzerland

* Swiss people

Swiss may also refer to: Places

* Swiss, Missouri

* Swiss, North Carolina

* Swiss, West Virginia

* Swiss, Wisconsin

Other uses

* Swiss Café, an old café located ...

honorary

consul general

A consul is an official representative of a government who resides in a foreign country to assist and protect citizens of the consul's country, and to promote and facilitate commercial and diplomatic relations between the two countries.

A consu ...

to the United States. Among his family, he was the closest to his mother, who despite being "inclined to instruction", showed great affection towards her son.

Hoover was born in a house on the present site of Capitol Hill United Methodist Church, located on

Seward Square near

Eastern Market in Washington's

Capitol Hill

Capitol Hill is a neighborhoods in Washington, D.C., neighborhood in Washington, D.C., located in both the Northeast, Washington, D.C., Northeast and Southeast, Washington, D.C., Southeast quadrants. It is bounded by 14th Street SE & NE, F S ...

neighborhood. A stained glass window in the church is dedicated to him. Hoover did not have a birth certificate filed upon his birth, although it was required in 1895 in Washington. Two of his siblings did have certificates, but Hoover's was not filed until 1938 when he was 43.

[Hoover had 7 Children

]

Hoover lived his entire life in Washington, D.C. He attended

Central High School, where he sang in the school choir, participated in the

Reserve Officers' Training Corps

The Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC; or ) is a group of college- and university-based officer-training programs for training commissioned officers of the United States Armed Forces.

While ROTC graduate officers serve in all branches o ...

program, and competed on the debate team.

During debates, he argued against women getting the right to vote and against the abolition of the death penalty. The school newspaper applauded his "cool, relentless logic".

[ Hoover ]stutter

Stuttering, also known as stammering, is a speech disorder characterized externally by involuntary repetitions and prolongations of sounds, syllables, words, or phrases as well as involuntary silent pauses called blocks in which the person who ...

ed as a boy, which he later learned to manage by teaching himself to talk quickly—a style that he carried through his adult career. He eventually spoke with such ferocious speed that stenographers had a hard time following him.

Hoover was 18 years old when he accepted his first job, an entry-level position as messenger in the orders department at the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is a research library in Washington, D.C., serving as the library and research service for the United States Congress and the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It also administers Copyright law o ...

. The library was a half mile from his house. The experience shaped both Hoover and the creation of the FBI profiles; as Hoover observed in a 1951 letter, "This job ... trained me in the value of collating material. It gave me an excellent foundation for my work in the FBI where it has been necessary to collate information and evidence."

In 1916, Hoover obtained a Bachelor of Laws

A Bachelor of Laws (; LLB) is an undergraduate law degree offered in most common law countries as the primary law degree and serves as the first professional qualification for legal practitioners. This degree requires the study of core legal subje ...

from the George Washington University Law School

The George Washington University Law School (GW Law) is the law school of George Washington University, a Private university, private research university in Washington, D.C. Established in 1865, GW Law is the oldest law school in Washington, D. ...

, where he was a member of the Alpha Nu Chapter of the Kappa Alpha Order, a Southern fraternity that was born out of a desire to "carry on the legacy of the 'incomparable flower of Southern Knighthood after the defeat of the Confederacy in 1865. Some prominent Kappa Alpha alumni, who had an influence on Hoover's future beliefs, included author Thomas Dixon and John Temple Graves. Hoover graduated with an LL.M. in 1917 from the same university. While a law student, Hoover became interested in the career of Anthony Comstock, the New York City U.S. Postal Inspector, who waged prolonged campaigns against fraud, vice

A vice is a practice, behaviour, Habit (psychology), habit or item generally considered morally wrong in the associated society. In more minor usage, vice can refer to a fault, a negative character trait, a defect, an infirmity, or a bad or unhe ...

, pornography, and birth control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth control only be ...

.[

]

Department of Justice

War Emergency Division

Immediately after getting his LL.M. degree, Hoover was hired by the Justice Department to work in the War Emergency Division.[

] He accepted the clerkship on July 27, 1917, aged 22. The job paid $990 a year ($ in dollars) and was exempt from the draft.Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

at the beginning of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

to arrest and jail allegedly disloyal foreigners without trial.

Bureau of Investigation

Head of the Radical Division

In August 1919, the 24-year-old Hoover became head of the Bureau of Investigation's new General Intelligence Division, also known as the Radical Division because its goal was to monitor and disrupt the work of domestic radicals.[

] America's First Red Scare

The first Red Scare was a period during History of the United States (1918–1945), the early 20th-century history of the United States marked by a widespread fear of Far-left politics, far-left movements, including Bolsheviks, Bolshevism a ...

was beginning, and one of Hoover's first assignments was to carry out the Palmer Raids

The Palmer Raids were a series of raids conducted in November 1919 and January 1920 by the United States Department of Justice under the administration of President Woodrow Wilson to capture and arrest suspected socialists, especially anarchist ...

.[

] Hoover and his chosen assistant, George Ruch, monitored a variety of U.S. radicals. Targets during this period included Marcus Garvey

Marcus Mosiah Garvey Jr. (17 August 188710 June 1940) was a Jamaican political activist. He was the founder and first President-General of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL) (commonly known a ...

;[

] Rose Pastor Stokes and Cyril Briggs;[

] Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born Anarchism, anarchist revolutionary, political activist, and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europ ...

and Alexander Berkman;[

] and future Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, advocating judicial restraint.

Born in Vienna, Frankfurter im ...

, who, Hoover maintained, was "the most dangerous man in the United States".[

] In 1920, at D.C.'s Federal Lodge No. 1 in Washington, D.C., the 25-year-old Hoover was initiated as a Freemason

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

. He went on to join the Scottish Rite

The Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry is a List of Masonic rites, rite within the broader context of Freemasonry. It is the most widely practiced List of Masonic rites, Rite in the world. In some parts of the world, and in the ...

in which he was made a 33rd Degree Inspector General Honorary in 1955.

Head of the Bureau of Investigation

In 1921, Hoover rose in the Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. An agency of the United States Department of Justice, the FBI is a member of ...

to deputy head, and in 1924 the Attorney General made him the acting director. On May 10, 1924, President Calvin Coolidge appointed Hoover as the fifth Director of the Bureau of Investigation, partly in response to allegations that the prior director, William J. Burns, was involved in the Teapot Dome scandal

The Teapot Dome scandal was a political corruption scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Warren G. Harding. It centered on Interior Secretary Albert B. Fall, who had leased Navy petroleum reserves at Teapot Do ...

. When Hoover took over the Bureau of Investigation, it had approximately 650 employees, including 441 Special Agents. Hoover fired all female agents and banned the future hiring of them. Hoover was sometimes unpredictable in his leadership. He frequently fired Bureau agents, singling out those he thought "looked stupid like truck drivers," or whom he considered "pinheads". He also relocated agents who had displeased him to career-ending assignments and locations. Melvin Purvis was a prime example: Purvis was one of the most effective agents in capturing and breaking up 1930s gangs, and it is alleged that Hoover maneuvered him out of the Bureau because he was envious of the substantial public recognition Purvis received.

In December 1929, Hoover oversaw the protection detail for the Japanese Naval Delegation who were visiting Washington, D.C., on their way to attend negotiations for the 1930 London Naval Treaty (officially called Treaty for the Limitation and Reduction of Naval Armament). The Japanese delegation was greeted at Washington Union (train) Station by U.S. Secretary of State Henry L. Stimson and the Japanese Ambassador Katsuji Debuchi. The Japanese delegation then visited the White House to meet with President

Hoover was sometimes unpredictable in his leadership. He frequently fired Bureau agents, singling out those he thought "looked stupid like truck drivers," or whom he considered "pinheads". He also relocated agents who had displeased him to career-ending assignments and locations. Melvin Purvis was a prime example: Purvis was one of the most effective agents in capturing and breaking up 1930s gangs, and it is alleged that Hoover maneuvered him out of the Bureau because he was envious of the substantial public recognition Purvis received.

In December 1929, Hoover oversaw the protection detail for the Japanese Naval Delegation who were visiting Washington, D.C., on their way to attend negotiations for the 1930 London Naval Treaty (officially called Treaty for the Limitation and Reduction of Naval Armament). The Japanese delegation was greeted at Washington Union (train) Station by U.S. Secretary of State Henry L. Stimson and the Japanese Ambassador Katsuji Debuchi. The Japanese delegation then visited the White House to meet with President Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was the 31st president of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933. A wealthy mining engineer before his presidency, Hoover led the wartime Commission for Relief in Belgium and ...

.

Depression-era gangsters

In the early 1930s, criminal gangs carried out large numbers of bank robberies in the Midwest

The Midwestern United States (also referred to as the Midwest, the Heartland or the American Midwest) is one of the four census regions defined by the United States Census Bureau. It occupies the northern central part of the United States. It ...

. They used their superior firepower and fast getaway cars to elude local law enforcement agencies and avoid arrest. Many of these criminals frequently made newspaper headlines across the United States, particularly John Dillinger

John Herbert Dillinger (; June 22, 1903 – July 22, 1934) was an American gangster during the Great Depression. He commanded the Dillinger Gang, which was accused of robbing twenty-four banks and four police stations. Dillinger was imprison ...

, who became famous for leaping over bank cages, and repeatedly escaping from jails

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol, penitentiary, detention center, correction center, correctional facility, or remand center, is a facility where people are imprisoned under the authority of the state, usually as punishment for various cri ...

and police traps.

The robbers operated across state lines, and Hoover pressed to have their crimes recognized as federal offenses so that he and his men would have the authority to pursue them and get the credit for capturing them. Initially, the Bureau suffered some embarrassing foul-ups, in particular with Dillinger and his conspirators. A raid on a summer lodge in Manitowish Waters, Wisconsin, called " Little Bohemia", left a Bureau agent and a civilian bystander dead and others wounded; all the gangsters escaped.

Hoover realized that his job was then on the line, and he pulled out all stops to capture the culprits. In late July 1934, Special Agent Melvin Purvis, the Director of Operations in the Chicago office, received a tip on Dillinger's whereabouts that paid off when Dillinger was located, ambushed, and killed by Bureau agents outside the Biograph Theater.FBI Laboratory

The FBI Laboratory (also called the Laboratory Division) is a division within the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation that provides forensic analysis support services to the FBI, as well as to state and local Law enforcement agency, l ...

, a division established in 1932 to examine and analyze evidence

Evidence for a proposition is what supports the proposition. It is usually understood as an indication that the proposition is truth, true. The exact definition and role of evidence vary across different fields. In epistemology, evidence is what J ...

found by the FBI.

American Mafia

During the 1930s, Hoover persistently denied the existence of organized crime

Organized crime is a category of transnational organized crime, transnational, national, or local group of centralized enterprises run to engage in illegal activity, most commonly for profit. While organized crime is generally thought of as a f ...

, despite numerous organized crime shootings as Mafia

"Mafia", as an informal or general term, is often used to describe criminal organizations that bear a strong similarity to the Sicilian Mafia, original Mafia in Sicily, to the Italian-American Mafia, or to other Organized crime in Italy, organiz ...

groups struggled for control of the lucrative profits deriving from illegal alcohol sales during Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic b ...

, and later for control of prostitution, illegal drugs

Illegal may refer to:

Law

* Violation of law

** Crime

In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable by a State (polity), state or other authority. The term ''crime'' does not, in modern criminal law, have any simple and uni ...

and other criminal enterprises. Hoover was reluctant to pursue the Mafia as he knew that organized crime investigations typically required excessive man hours while resulting in a relatively small number of arrests. He also feared that placing underpaid FBI agents—who had a starting annual salary $5,500 in the mid 1950s—in close contact with wealthy mobsters could undermine the FBI's reputation of incorruptibility.[The FBI in Boston: Hoover, Lies and Murder](_blank)

George Hassett, ''Crime Magazine'' (May 13, 2013)

Many writers believe Hoover's denial of the Mafia's existence and his failure to use the full force of the FBI to investigate it were due to Mafia gangsters Meyer Lansky

Meyer Lansky (born Maier Suchowljansky; July 4, 1902 – January 15, 1983), known as the "Mob's Accountant", was an American organized crime figure who, along with his associate Lucky Luciano, Charles "Lucky" Luciano, was instrumental in the dev ...

and Frank Costello

Frank Costello (; born Francesco Castiglia ; January 26, 1891 – February 18, 1973) was an Italian-American crime boss of the Luciano crime family.

Born in Italy, he moved with his family to the United States as a child. As a youth he joined N ...

's possession of embarrassing photographs of Hoover in the company of his ''protégé'', FBI Deputy Director Clyde Tolson.Walter Winchell

Walter Winchell (April 7, 1897 – February 20, 1972) was a syndicated American newspaper gossip columnist and radio news commentator. Originally a vaudeville performer, Winchell began his newspaper career as a Broadway reporter, critic and c ...

.[

] Hoover had a reputation as "an inveterate horseplayer" and was known to send Special Agents to place $100 bets for him.[Sifakis, p.127.] Hoover once said the Bureau had "much more important functions" than arresting bookmakers and gamblers.Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

he was able to focus the FBI's attention on these investigations. From the mid-1940s through the mid-1950s, he paid little attention to criminal vice

A vice is a practice, behaviour, Habit (psychology), habit or item generally considered morally wrong in the associated society. In more minor usage, vice can refer to a fault, a negative character trait, a defect, an infirmity, or a bad or unhe ...

rackets such as illegal drugs, prostitution, extortion

Extortion is the practice of obtaining benefit (e.g., money or goods) through coercion. In most jurisdictions it is likely to constitute a criminal offence. Robbery is the simplest and most common form of extortion, although making unfounded ...

, and flatly denied the existence of the Mafia in the United States. In the 1950s, evidence of the FBI's unwillingness to investigate the Mafia became a topic of public criticism. After the Apalachin meeting of crime bosses in 1957, Hoover could no longer deny the existence of a nationwide crime syndicate. In fact, Cosa Nostra

The Sicilian Mafia or Cosa Nostra (, ; "our thing"), also referred to as simply Mafia, is a criminal society and criminal organization originating on the island of Sicily and dates back to the mid-19th century. Emerging as a form of local protect ...

's control of the Syndicate's many branches operating criminal activities throughout North America prevailed and was heavily reported in popular newspapers and magazines. Hoover created the "Top Hoodlum Program" and went after the syndicate's top bosses throughout the country.

Investigation of subversion and radicals

Hoover was concerned about what he claimed was

Hoover was concerned about what he claimed was subversion

Subversion () refers to a process by which the values and principles of a system in place are contradicted or reversed in an attempt to sabotage the established social order and its structures of Power (philosophy), power, authority, tradition, h ...

, and under his leadership the FBI investigated tens of thousands of suspected subversives and radicals. According to critics, Hoover tended to exaggerate the dangers of these alleged subversives and many times overstepped his bounds in his pursuit of eliminating that perceived threat.Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA (CPUSA), officially the Communist Party of the United States of America, also referred to as the American Communist Party mainly during the 20th century, is a communist party in the United States. It was established ...

(CPUSA) had dwindled to less than 10,000, of whom some 1,500 were informants for the FBI.

Florida and Long Island U-boat landings

The FBI investigated rings of German saboteurs and spies starting in the late 1930s and had primary responsibility for counterespionage. The first arrests of German agents were made in 1938 and continued throughout World War II. In the Quirin affair during World War II, German U-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

s set two small groups of Nazi agents ashore in Florida and on Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated continental island in southeastern New York (state), New York state, extending into the Atlantic Ocean. It constitutes a significant share of the New York metropolitan area in both population and land are ...

to cause acts of sabotage

Sabotage is a deliberate action aimed at weakening a polity, government, effort, or organization through subversion, obstruction, demoralization (warfare), demoralization, destabilization, divide and rule, division, social disruption, disrupti ...

within the country. The two teams were apprehended after one of the agents contacted the FBI and told them everything – he was also charged and convicted.

Wiretapping

During this time period, President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

, out of concern over Nazi agents in the United States, gave "qualified permission" to wiretap

Wiretapping, also known as wire tapping or telephone tapping, is the monitoring of telephone and Internet-based conversations by a third party, often by covert means. The wire tap received its name because, historically, the monitoring connecti ...

persons "suspected ... fsubversive activities". He went on to add in 1941 that the U.S. Attorney General

The United States attorney general is the head of the United States Department of Justice and serves as the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government. The attorney general acts as the principal legal advisor to the president of the ...

had to be informed of its use in each case. Attorney General Robert H. Jackson

Robert Houghwout Jackson (February 13, 1892 – October 9, 1954) was an American lawyer, jurist, and politician who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1941 until his death in 1954. He had previously served as Un ...

left it to Hoover to decide how and when to use wiretaps, as he found the "whole business" distasteful. Jackson's successor at the post of Attorney General, Francis Biddle

Francis Beverley Biddle (May 9, 1886 – October 4, 1968) was an American lawyer and judge who was the United States Attorney General during World War II. He also served as the primary American judge during Nuremberg trials following World War I ...

, did turn down Hoover's requests on occasion. An example of J. Edgar Hoover approving wiretaps is the Nixon wiretaps.

Concealed espionage discoveries

In the late 1930s, President Franklin D. Roosevelt gave Hoover the task to investigate both foreign espionage in the United States and the activities of domestic communists and fascists. When the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

began in the late 1940s, the FBI under Hoover undertook the intensive surveillance of communists and other left-wing activists in the United States.Venona project

The Venona project was a United States counterintelligence program initiated during World War II by the United States Army's Signal Intelligence Service and later absorbed by the National Security Agency (NSA), that ran from February 1, 1943, u ...

, a pre-World War II joint project with the British to eavesdrop on Soviet spies in the UK and the United States. They did not initially realize that espionage was being committed, but the Soviets' multiple use of one-time pad

The one-time pad (OTP) is an encryption technique that cannot be Cryptanalysis, cracked in cryptography. It requires the use of a single-use pre-shared key that is larger than or equal to the size of the message being sent. In this technique, ...

ciphers (which with single use are unbreakable) created redundancies that allowed some intercepts to be decoded. These established that espionage was being carried out. Hoover kept the intercepts – America's greatest counterintelligence

Counterintelligence (counter-intelligence) or counterespionage (counter-espionage) is any activity aimed at protecting an agency's Intelligence agency, intelligence program from an opposition's intelligence service. It includes gathering informati ...

secret – in a locked safe in his office. He chose not to inform President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

, Attorney General J. Howard McGrath, or Secretaries of State Dean Acheson

Dean Gooderham Acheson ( ; April 11, 1893October 12, 1971) was an American politician and lawyer. As the 51st United States Secretary of State, U.S. Secretary of State, he set the foreign policy of the Harry S. Truman administration from 1949 to ...

and General George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (31 December 1880 – 16 October 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army under pres ...

while they held office. He informed the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA; ) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and ...

(CIA) of the Venona Project in 1952.

Plans for expanding the FBI to do global intelligence

After World War II, Hoover advanced plans to create a "World-Wide Intelligence Service". These plans were shot down by the Truman administration. Truman objected to the plan, emerging bureaucratic competitors opposed the centralization of power inherent in the plans, and there was a considerable aversion to creating an American version of the "Gestapo".

Plans for suspending ''habeas corpus''

In 1946, Attorney General Tom C. Clark

Thomas Campbell Clark (September 23, 1899June 13, 1977) was an American lawyer who served as the 59th United States Attorney General, United States attorney general from 1945 to 1949 and as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United St ...

authorized Hoover to compile a list of potentially disloyal Americans who might be detained during a wartime national emergency. In 1950, at the outbreak of the Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

, Hoover submitted a plan to President Truman to suspend the writ of ''habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a legal procedure invoking the jurisdiction of a court to review the unlawful detention or imprisonment of an individual, and request the individual's custodian (usually a prison official) to ...

'' and detain 12,000 Americans suspected of disloyalty. Truman did not act on the plan.

COINTELPRO and the 1950s

In 1956, Hoover was becoming increasingly frustrated by

In 1956, Hoover was becoming increasingly frustrated by U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

decisions that limited the Justice Department's ability to prosecute people for their political opinions, most notably communists. Some of his aides reported that he purposely exaggerated the threat of communism to "ensure financial and public support for the FBI." At this time he formalized a covert "dirty tricks" program under the name COINTELPRO. COINTELPRO was first used to disrupt the CPUSA, where Hoover ordered observation and pursuit of targets that ranged from suspected citizen spies to larger celebrity figures, such as Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is considered o ...

, whom he saw as spreading Communist propaganda

Communist propaganda is the artistic and social promotion of the ideology of communism, communist worldview, communist society, and interests of the communist movement. While it tends to carry a negative connotation in the Western world, the te ...

.

COINTELPRO's methods included infiltration, burglaries, setting up illegal wiretaps, planting forged documents, and spreading false rumors about key members of target organizations. Some authors have charged that COINTELPRO methods also included inciting violence and arranging murders. This program remained in place until it was exposed to the public in 1971, after the burglary by a group of eight activists of many internal documents from an office in Media, Pennsylvania

Media is a borough (Pennsylvania), borough in and the county seat of Delaware County, Pennsylvania, United States. It is located about west of Philadelphia. It is part of the Delaware Valley, also known as the Philadelphia metropolitan area.

...

, whereupon COINTELPRO became the cause of some of the harshest criticism of Hoover and the FBI. COINTELPRO's activities were investigated in 1975 by the United States Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, called the "Church Committee

The Church Committee (formally the United States Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities) was a US Senate select committee in 1975 that investigated abuses by the Central Intelligence ...

" after its chairman, Senator Frank Church (D-Idaho); the committee declared COINTELPRO's activities were illegal and contrary to the Constitution.

Hoover amassed significant power by collecting files containing large amounts of compromising and potentially embarrassing information on many powerful people, especially politicians. According to Laurence Silberman, appointed Deputy Attorney General in early 1974, FBI Director Clarence M. Kelley thought such files either did not exist or had been destroyed. After ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'', locally known as ''The'' ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'' or ''WP'', is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C., the national capital. It is the most widely circulated newspaper in the Washington m ...

'' broke a story in January 1975, Kelley searched and found them in his outer office. The House Judiciary Committee

The U.S. House Committee on the Judiciary, also called the House Judiciary Committee, is a standing committee of the United States House of Representatives. It is charged with overseeing the administration of justice within the federal courts, f ...

then demanded that Silberman testify about them.

Reaction to civil rights groups

In 1956, several years before he targeted

In 1956, several years before he targeted Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister, civil and political rights, civil rights activist and political philosopher who was a leader of the civil rights move ...

, Hoover had a public showdown with T. R. M. Howard, a civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

leader from Mound Bayou, Mississippi

Mound Bayou is a city in Bolivar County, Mississippi, Bolivar County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 1,533 at the 2010 United States Census, 2010 census, down from 2,102 in 2000. It was founded as an independent black community in ...

. During a national speaking tour, Howard had criticized the FBI's failure to investigate thoroughly the racially motivated murders of George W. Lee, Lamar Smith, and Emmett Till

Emmett Louis Till (July 25, 1941 – August 28, 1955) was an African American youth, who was 14 years old when he was abducted and Lynching in the United States, lynched in Mississippi in 1955 after being accused of offending a white woman, ...

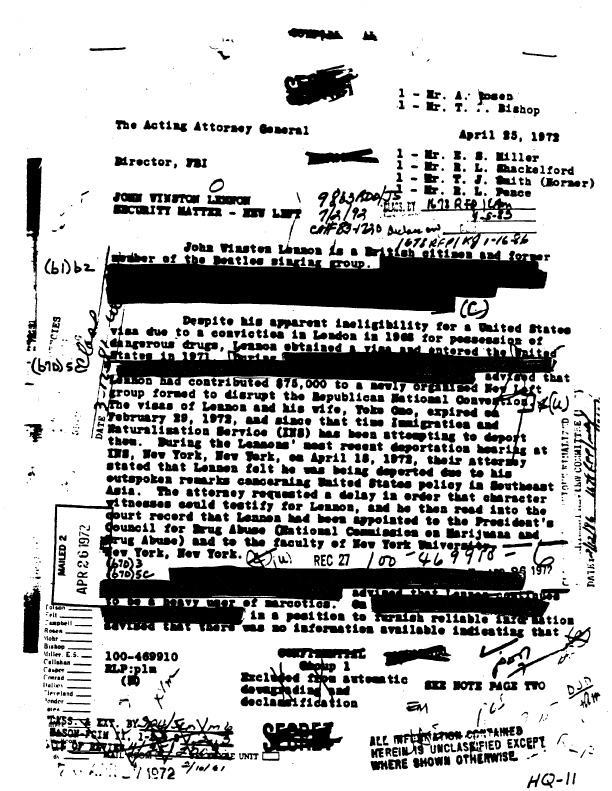

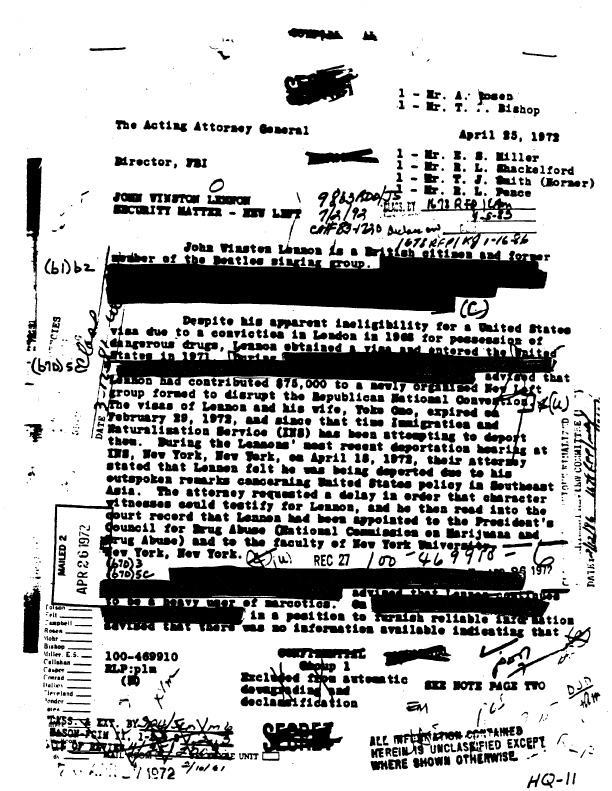

. Hoover wrote an open letter to the press singling out these statements as "irresponsible". In the 1960s, Hoover's FBI monitored John Lennon

John Winston Ono Lennon (born John Winston Lennon; 9 October 19408 December 1980) was an English singer-songwriter, musician and activist. He gained global fame as the founder, co-lead vocalist and rhythm guitarist of the Beatles. Lennon's ...

, Malcolm X

Malcolm X (born Malcolm Little, later el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz; May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965) was an African American revolutionary, Islam in the United States, Muslim minister and human rights activist who was a prominent figur ...

, and Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali (; born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.; January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer and social activist. A global cultural icon, widely known by the nickname "The Greatest", he is often regarded as the gr ...

. The COINTELPRO tactics were later extended to organizations such as the Nation of Islam

The Nation of Islam (NOI) is a religious organization founded in the United States by Wallace Fard Muhammad in 1930. A centralized and hierarchical organization, the NOI is committed to black nationalism and focuses its attention on the Afr ...

, the Black Panther Party

The Black Panther Party (originally the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense) was a Marxism–Leninism, Marxist–Leninist and Black Power movement, black power political organization founded by college students Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newto ...

, King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African Americans, African-American civil rights organization based in Atlanta, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. SCLC is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., ...

and others. Hoover's moves against people who maintained contacts with subversive elements, some of whom were members of the civil rights movement, also led to accusations of trying to undermine their reputations.

The treatment of Martin Luther King Jr. and actress Jean Seberg are two examples: Jacqueline Kennedy

Jacqueline Lee Kennedy Onassis ( ; July 28, 1929 – May 19, 1994) was an American writer, book editor, and socialite who served as the first lady of the United States from 1961 to 1963, as the wife of President John F. Kennedy. A popular f ...

recalled that Hoover told President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the first Roman Catholic and youngest person elected p ...

that King had tried to arrange a sex party while in the capital for the March on Washington

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (commonly known as the March on Washington or the Great March on Washington) was held in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963. The purpose of the march was to advocate for the civil and economic rig ...

and that Hoover told Robert F. Kennedy that King had made derogatory comments during the President's funeral. Under Hoover's leadership, the FBI sent an anonymous blackmail letter to King shortly before he accepted the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, indicating "There is only one thing left for you to do", which King interpreted as an exhortation for him to commit suicide;Roy Wilkins

Roy Ottoway Wilkins (August 30, 1901 – September 8, 1981) was an American civil rights leader from the 1930s to the 1970s. Wilkins' most notable role was his leadership of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), ...

and urged King to step aside and let other men lead the movement. The

The Church Committee

The Church Committee (formally the United States Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities) was a US Senate select committee in 1975 that investigated abuses by the Central Intelligence ...

, a U.S. Senate subcommittee led by U.S. Senator Frank Church which investigated numerous controversial FBI activities, found in 1976 that the FBI's intent was to push King out of SCLC leadership.Andrew Young

Andrew Jackson Young Jr. (born March 12, 1932) is an American politician, diplomat, and activist. Beginning his career as a pastor, Young was an early leader in the civil rights movement, serving as executive director of the Southern Christia ...

claimed in a 2013 interview with the Academy of Achievement

The American Academy of Achievement, colloquially known as the Academy of Achievement, is a nonprofit educational organization that recognizes some of the highest-achieving people in diverse fields and gives them the opportunity to meet one ano ...

that the main source of tension between the SCLC and FBI was the government agency's lack of black agents, and that both parties were willing to co-operate with each other by the time the Selma to Montgomery marches

The Selma to Montgomery marches were three Demonstration (protest), protest marches, held in 1965, along the highway from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital of Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery. The marches were organized by Nonviolence, nonvi ...

had taken place.

In one 1965 incident, white civil rights worker Viola Liuzzo was murdered by Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

smen, who had given chase and fired shots into her car after noticing that her passenger was a young black man; one of the Klansmen was Gary Thomas Rowe, an acknowledged FBI informant.[Gary May, The Informant: The FBI, the Ku Klux Klan, and the Murder of Viola Luzzo, Yale University Press, 2005.] The FBI spread rumors that Liuzzo was a member of the CPUSA and had abandoned her children to have sexual relationships with African Americans involved in the civil rights movement.Weather Underground

The Weather Underground was a far-left Marxist militant organization first active in 1969, founded on the Ann Arbor campus of the University of Michigan. Originally known as the Weathermen, or simply Weatherman, the group was organized as a f ...

per testimony from William C. Sullivan.

Late career and death

One of his biographers, Kenneth Ackerman, wrote that the allegation that Hoover's secret files kept presidents from firing him "is a myth".[

] President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

was recorded in 1971 as stating that one of the reasons he would not fire Hoover was that he was afraid of Hoover's reprisals against him. Similarly, Presidents Harry S. Truman and John F. Kennedy considered dismissing Hoover as FBI Director, but ultimately concluded that the political cost of doing so would be too great.Jack Valenti

Jack Joseph Valenti (September 5, 1921 – April 26, 2007) was an American political advisor and lobbyist who served as a Special Assistant to U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson. He was also the longtime president of the Motion Picture Association ...

, a special assistant and confidant of President Lyndon Johnson, married to Johnson's personal secretary, but who allegedly maintained a gay relationship with a commercial photographer friend.

Hoover personally directed the FBI investigation of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy

John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, was assassinated while riding in a presidential motorcade through Dealey Plaza in Dallas, Texas, on November 22, 1963. Kennedy was in the vehicle with his wife Jacqueline Kennedy Onas ...

. In 1964, just days before Hoover testified in the earliest stages of the Warren Commission

The President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy, known unofficially as the Warren Commission, was established by President of the United States, President Lyndon B. Johnson through on November 29, 1963, to investigate the A ...

hearings, President Lyndon B. Johnson waived the then mandatory U.S. Government Service Retirement Age of 70, allowing Hoover to remain the FBI Director "for an indefinite period of time". The House Select Committee on Assassinations issued a report in 1979 critical of the performance by the FBI, the Warren Commission, and other agencies. The report criticized the FBI's (Hoover's) reluctance to investigate thoroughly the possibility of a conspiracy to assassinate the President.

When Nixon took office in January 1969, Hoover had just turned 74. There was a growing sentiment in Washington, D.C., that the aging FBI chief should retire, but Hoover's power and friends in Congress remained too strong for him to be forced to do so. Hoover remained director of the FBI until he died of a heart attack in his Washington home, on May 2, 1972,[

] whereupon operational command of the Bureau was passed onto Associate Director Clyde Tolson. On May 3, 1972, Nixon appointed L. Patrick Gray

Louis Patrick Gray III (July 18, 1916 – July 6, 2005) was acting director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) from May 3, 1972, to April 27, 1973. During this time, the FBI was in charge of the initial investigation into the burglari ...

– a Justice Department official with no FBI experience – as acting director of the FBI, with W. Mark Felt becoming associate director.

Hoover's body lay in state in the U.S. Capitol rotunda, where Chief Justice Warren Burger

Warren Earl Burger (September 17, 1907 – June 25, 1995) was an American attorney who served as the 15th chief justice of the United States from 1969 to 1986.

Born in Saint Paul, Minnesota, Burger graduated from the St. Paul College of Law i ...

eulogized him. Up to that time, Hoover was the only civil servant to have lain in state according to ''The New York Daily News''. At the time, ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' observed that this was "an honor accorded to only 21 persons before, of whom eight were Presidents or former Presidents." President Nixon delivered another eulogy at the funeral service in The National Presbyterian Church, and called Hoover "one of the Giants, hose

A hose is a flexible hollow tube or pipe designed to carry fluids from one location to another, often from a faucet or hydrant.

Early hoses were made of leather, although modern hoses are typically made of rubber, canvas, and helically wound w ...

long life brimmed over with magnificent achievement and dedicated service to this country which he loved so well". Hoover is buried in the Congressional Cemetery

The Congressional Cemetery, officially Washington Parish Burial Ground, is a historic and active cemetery located at 1801 E Street in Washington, D.C., in the Hill East neighborhood on the west bank of the Anacostia River. It is the only American ...

in Washington, D.C., next to the graves of his parents and a sister who had died in infancy.

Legacy

FBI

Biographer Kenneth D. Ackerman summarizes Hoover's legacy thus:

For better or worse, he built the FBI into a modern, national organization stressing professionalism and scientific crime-fighting. For most of his life, Americans considered him a hero. He made the G-Man brand so popular that, at its height, it was harder to become an FBI agent than to be accepted into an Ivy League college.

Hoover worked to groom the image of the FBI in American media; he was a consultant to Warner Brothers

Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. (WBEI), commonly known as Warner Bros. (WB), is an American filmed entertainment studio headquartered at the Warner Bros. Studios complex in Burbank, California and the main namesake subsidiary of Warner Bro ...

for a theatrical film about the FBI, '' The FBI Story'' (1959), and in 1965 on Warner's long-running spin-off television series, '' The F.B.I.'' President Harry S. Truman said that Hoover transformed the FBI into his private secret police

image:Putin-Stasi-Ausweis.png, 300px, Vladimir Putin's secret police identity card, issued by the East German Stasi while he was working as a Soviet KGB liaison officer from 1985 to 1989. Both organizations used similar forms of repression.

Secre ...

force:

... we want no Gestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

or secret police. The FBI is tending in that direction. They are dabbling in sex-life scandals and plain blackmail. J. Edgar Hoover would give his right eye to take over, and all congressmen and senators are afraid of him.

Because Hoover's actions came to be seen as abuses of power, FBI directors are now limited to one 10-year term, subject to extension by the U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and House have the authority under Article One of the ...

. Jacob Heilbrunn, journalist and senior editor at ''The'' ''National Interest'', gives a mixed assessment of Hoover's legacy:

The FBI Headquarters in Washington, D.C. is named the J. Edgar Hoover Building, after Hoover. Because of the controversial nature of Hoover's legacy, both Republicans and Democrats have periodically introduced legislation in the House and Senate to rename it. The first such proposal came just two months after the building's inauguration. On December 12, 1979, Gilbert Gude – a Republican congressman from Maryland – introduced H.R. 11137, which would have changed the name of the edifice from the "J. Edgar Hoover F.B.I. Building" to simply the "F.B.I. Building";Harry Reid

Harry Mason Reid Jr. (; December 2, 1939 – December 28, 2021) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States Senate, United States senator from Nevada from 1987 to 2017. He led the Senate Democratic Caucus from 2005 to 2 ...

sponsored an amendment to strip Hoover's name from the building, stating that "J. Edgar Hoover's name on the FBI building is a stain on the building."[O'Keefe, Ed. "FBI J. Edgar Hoover Building 'Deteriorating,' Report Says." ''Washington Post.'' November 9, 2011.](_blank)

Accessed September 29, 2012. and its naming might eventually be made moot by the FBI moving its headquarters to a new suburban site. Hoover's practice of violating civil liberties for the stated sake of national security has been questioned in reference to recent national surveillance programs. An example is a lecture titled ''Civil Liberties and National Security: Did Hoover Get it Right?'', given at The Institute of World Politics

The Institute of World Politics (IWP) is a private graduate school of national security, intelligence, and international affairs in Washington, D.C., and Reston, Virginia. Founded in 1990, the school offers courses related to intelligence, nati ...

on April 21, 2015.

Some qualified praise for Hoover came from the Soviet double agent Kim Philby

Harold Adrian Russell "Kim" Philby (1 January 191211 May 1988) was a British intelligence officer and a double agent for the Soviet Union. In 1963, he was revealed to be a member of the Cambridge Five, a spy ring that had divulged British secr ...

, who spent time in Washington. Philby respected the way Hoover had built the FBI as a serious intelligence agency from virtually nothing, but Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican Party (United States), Republican United States Senate, U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death at age ...

was a fake; and Hoover knew that McCarthy was a fake, but found it useful to manipulate McCarthy.

White Christian nationalism

Through his 2023 book ''The Gospel of J. Edgar Hoover'', Lerone Martin argues that an understated but long-lasting influence of Hoover has been to normalize " white Christian nationalism" in the country, Hoover framing his work with the FBI as a crusade modelled after Catholic orders such as the Jesuits

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

, despite himself being Protestant, favoring religiosity among FBI members (including "spiritual retreats") as well weaponizing traditional Christian rhetoric against what he perceived to be the atheist and Communist menace to the United States, for him founded on Christian principles. Martin also says that such social conservatism was not only religious but also racial in nature, as Hoover aimed to maintain the ethnic dynamics of his days, including the legal superiority of the White Americans

White Americans (sometimes also called Caucasian Americans) are Americans who identify as white people. In a more official sense, the United States Census Bureau, which collects demographic data on Americans, defines "white" as " person hav ...

over the minorities.

Private life

Pets

Hoover received his first dog from his parents when he was a child, after which he was never without one. He owned many throughout his lifetime and became an aficionado especially knowledgeable in breeding of pedigrees, particularly Cairn Terriers and Beagle

The Beagle is a small breed of scent hound, similar in appearance to the much larger foxhound. The beagle was developed primarily for hunting rabbit or hare, known as beagling. Possessing a great sense of smell and superior tracking inst ...

s. He gave many dogs to notable people, such as Presidents Herbert Hoover (not closely related) and Lyndon B. Johnson, and buried seven canine pets, including a Cairn Terrier named Spee De Bozo, at Aspen Hill Memorial Park, in Silver Spring, Maryland

Silver Spring is a census-designated place (CDP) in southeastern Montgomery County, Maryland, United States, near Washington, D.C. Although officially Unincorporated area, unincorporated, it is an edge city with a population of 81,015 at the 2020 ...

.

Sexuality

Rumors began circulating in the 1940s that Hoover was homosexual

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between people of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" exc ...

. The historians John Stuart Cox and Athan G. Theoharis speculated that Clyde Tolson, who became an assistant director to Hoover in his mid 40s and became his primary heir, had a sexual relationship with Hoover until the latter's death.[

] Hoover reportedly hunted down and threatened anyone who made insinuations about his sexuality

Human sexuality is the way people experience and express themselves sexually. This involves biological, psychological, physical, erotic, emotional, social, or spiritual feelings and behaviors. Because it is a broad term, which has varied ...

.[

] Truman Capote

Truman Garcia Capote ( ; born Truman Streckfus Persons; September 30, 1924 – August 25, 1984) was an American novelist, screenwriter, playwright, and actor. Several of his short stories, novels, and plays have been praised as literary classics ...

, who enjoyed repeating salacious rumors about Hoover, once remarked that he was more interested in making Hoover angry than determining whether the rumors were true.Screw

A screw is an externally helical threaded fastener capable of being tightened or released by a twisting force (torque) to the screw head, head. The most common uses of screws are to hold objects together and there are many forms for a variety ...

'' published the first reference in print to Hoover's sexuality, titled "Is J. Edgar Hoover a Fag?"

Some associates and scholars dismiss rumors about Hoover's sexuality, and rumors about his relationship with Tolson in particular, as unlikely,[

] while others have described them as probable or even "confirmed".[

] Still other scholars have reported the rumors without expressing an opinion. Cox and Theoharis concluded that "the strange likelihood is that Hoover never knew sexual desire at all."[ Anthony Summers, who wrote ''Official and Confidential: The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover'' (1993), stated that there was no ambiguity about the FBI director's sexual proclivities and described him as "]bisexual

Bisexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior toward both males and females. It may also be defined as the attraction to more than one gender, to people of both the same and different gender, or the attraction t ...

with failed heterosexuality

Heterosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or Human sexual activity, sexual behavior between people of the opposite sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, heterosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or ...

".[

]

Hoover and Tolson

Hoover described Tolson as his alter ego

An alter ego (Latin for "other I") means an alternate Self (psychology), self, which is believed to be distinct from a person's normal or true original Personality psychology, personality. Finding one's alter ego will require finding one's other ...

: the men worked closely together during the day and, both single, frequently took meals, went to night clubs, and vacationed together.Mark Felt

William Mark Felt Sr. (August 17, 1913 – December 18, 2008) was an American law enforcement officer who worked for the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) from 1942 to 1973 and was known for his role in the Watergate scandal. Felt was ...

, say the relationship was "brotherly"; however, former FBI executive assistant director Mike Mason suggested that some of Hoover's colleagues denied that he had a sexual relationship with Tolson in an effort to protect Hoover's image.

The novelist William Styron

William Clark Styron Jr. (June 11, 1925 – November 1, 2006) was an American novelist and essayist who won major literary awards for his work.

Early life

Styron was born in the Hilton Village historic district of Newport News, Virginia, the so ...

told Summers that he once saw Hoover and Tolson in a California beach house, where the director was painting his friend's toenails, but subsequently clarified that he had not in fact witnessed this himself, although he believed the story to be true. Harry Hay, founder of the Mattachine Society

The Mattachine Society (), founded in 1950, was an early national gay rights organization in the United States, preceded by several covert and open organizations, such as Chicago's Society for Human Rights. Communist and labor activist Harry Ha ...

, one of the first gay rights

Rights affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) people vary greatly by country or jurisdiction—encompassing everything from the legal recognition of same-sex marriage to the death penalty for homosexuality.

Not ...

organizations, said Hoover and Tolson sat in boxes owned by and used exclusively by gay men at the Del Mar racetrack

The Del Mar Fairgrounds is an event venue in Del Mar, California. It hosts the annual San Diego County Fair. The venue sits on a property along the Pacific Ocean coastline. It includes the Del Mar Racetrack, built in 1936 by the Del Mar Thoroug ...

in California.American flag

The national flag of the United States, often referred to as the American flag or the U.S. flag, consists of thirteen horizontal Bar (heraldry), stripes, Variation of the field, alternating red and white, with a blue rectangle in the Canton ( ...

that draped Hoover's casket. Tolson is buried a few yards away from Hoover in the Congressional Cemetery.Meyer Lansky

Meyer Lansky (born Maier Suchowljansky; July 4, 1902 – January 15, 1983), known as the "Mob's Accountant", was an American organized crime figure who, along with his associate Lucky Luciano, Charles "Lucky" Luciano, was instrumental in the dev ...

is credited with having "controlled" compromising pictures of a sexual nature featuring Hoover with Tolson. In his book, ''Official and Confidential: The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover'', biographer Anthony Summers cites multiple primary sources regarding Lansky's use of blackmail

Blackmail is a criminal act of coercion using a threat.

As a criminal offense, blackmail is defined in various ways in common law jurisdictions. In the United States, blackmail is generally defined as a crime of information, involving a thr ...

to gain influence with politicians, policemen and judges. One stage for Lansky's acquisition of blackmail materials was orgies held by late attorney and Hoover protégé, Roy Cohn, and liquor magnate, Lewis Rosenstiel, who had lasting ties with the Mafia from his bootleg operations during Prohibition.

Other romantic allegations

One of Hoover's biographers, Richard Hack

Richard Hack (born March 20, 1951) is an Americans, American writer best known for his biographical books and screenplays. He is a frequent guest on talk shows and an outspoken critic of bias in television news.

Background

Born in Drexel Hill ...

, does not believe the director was gay. Hack notes that Hoover was romantically linked to actress Dorothy Lamour

Dorothy Lamour (born Mary Leta Dorothy Slaton; December 10, 1914 – September 22, 1996) was an American actress and singer. She is best remembered for having appeared in the ''Road to...'' movies, a series of successful comedies starring Bing C ...

in the late 1930s and early 1940s and that after Hoover's death, Lamour did not deny rumors that she had had an affair with him.Ginger Rogers

Ginger Rogers (born Virginia Katherine McMath; July 16, 1911 – April 25, 1995) was an American actress, dancer and singer during the Classical Hollywood cinema, Golden Age of Hollywood. She won an Academy Award for Best Actress for her starri ...

, so often that many of their mutual friends assumed the pair would eventually marry.

Pornography for blackmail

Hoover kept a large collection of pornographic films, photographs, and written materials, with particular emphasis on nude photos of celebrities. He reportedly used these for his own titillation and held them for blackmail

Blackmail is a criminal act of coercion using a threat.

As a criminal offense, blackmail is defined in various ways in common law jurisdictions. In the United States, blackmail is generally defined as a crime of information, involving a thr ...

purposes.

Cross-dressing story

Lewis Rosenstiel, founder of Schenley Industries

Schenley Industries was a liquor company based in New York City with headquarters in the Empire State Building and a distillery in Lawrenceburg, Indiana. It owned several brands of Bourbon whiskey, including Schenley, The Old Quaker Company, Cream ...

, was a close friend of Hoover's and the primary contributor to the J. Edgar Hoover Foundation. In his biography ''Official and Confidential: The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover'' (1993), journalist Anthony Summers quoted Rosenstiel's fourth wife, Susan, as claiming to have seen Hoover engaging in cross-dressing

Cross-dressing is the act of wearing clothes traditionally or stereotypically associated with a different gender. From as early as pre-modern history, cross-dressing has been practiced in order to disguise, comfort, entertain, and express onesel ...

in the 1950s at all-male parties at the Plaza Hotel

The Plaza Hotel (also known as The Plaza) is a luxury hotel and condominium apartment building in Midtown Manhattan in New York City. It is located on the western side of Grand Army Plaza, after which it is named, just west of Fifth Avenue, ...

with Rosenstiel, attorney Roy Cohn, and young male prostitutes.[

] Another Hoover biographer, Burton Hersh, later corroborated this story.Meyer Lansky

Meyer Lansky (born Maier Suchowljansky; July 4, 1902 – January 15, 1983), known as the "Mob's Accountant", was an American organized crime figure who, along with his associate Lucky Luciano, Charles "Lucky" Luciano, was instrumental in the dev ...

and Frank Costello

Frank Costello (; born Francesco Castiglia ; January 26, 1891 – February 18, 1973) was an Italian-American crime boss of the Luciano crime family.

Born in Italy, he moved with his family to the United States as a child. As a youth he joined N ...

obtained photos of Hoover having sex with Tolson and used them to ensure that the FBI did not target their illegal activities.[

] Additionally, Summers claimed that Hoover was friends with Billy Byars Jr., an alleged child pornographer and producer of the film '' The Genesis Children''.[

]

Fashion expert Tim Gunn

Timothy MacKenzie Gunn (born July 29, 1953) is an American author, academic, and television personality. He served on the faculty of Parsons School of Design from 1982 to 2007 and was chair of fashion design at the school from August 2000 to March ...

relayed a story on the radio news quiz show " Wait Wait...Don't Tell Me!". Gunn's father was Hoover's speech writer, and as a child Tim Gunn and his sister were on a tour of the FBI offices when their father asked them if they would like to meet Vivian Vance

Vivian Vance (born Vivian Roberta Jones; July 26, 1909 – August 17, 1979) was an American actress best known for playing landlady Ethel Mertz on the sitcom ''I Love Lucy'' (1951–1957), for which she won the 1953 Primetime Emmy Award for Outs ...

. They had a pleasant meeting with a woman in Hoover's office. Reflecting on this later as adults the Gunn children realized that Hoover was not present in the office and deemed this highly unusual. Later when Gunn included this visit in his "Gunn's Golden Rules" book the Simon and Schuster legal team attempted to corroborate the story of Vivian Vance visiting the FBI offices. Her biographers could not confirm this and a search of the FBI visitor logs did not show Vance had visited. Gunn's conclusion was that Hoover was impersonating Vance the day of his visit.

Another Hoover biographer who heard the rumors of homosexuality and blackmail, said he was unable to corroborate them, though it has been acknowledged that Lansky and other organized crime figures had frequently been allowed to visit the Del Charro Hotel in La Jolla, California

La Jolla ( , ) is a hilly, seaside neighborhood in San Diego, California, occupying of curving coastline along the Pacific Ocean. The population reported in the 2010 census was 46,781. The climate is mild, with an average daily temperature o ...

, which was owned by Hoover's friend, and staunch Lyndon B. Johnson supporter, Clint Murchison Sr.[ Hoover and Tolson also frequently visited the Del Charro Hotel.][

] Summers quoted a source named Charles Krebs as saying, "on three occasions that I knew about, maybe four, boys were driven down to La Jolla at Hoover's request."Christine Jorgensen

Christine Jorgensen (; May 30, 1926 – May 3, 1989) was an American actress, singer, recording artist, and transgender activist. A trans woman, she was the first person to become widely known in the United States for having Sex reassignment ...

wanna-be was too delicious not to savor." Biographer Kenneth Ackerman says that Summers' accusations have been "widely debunked by historians". The journalist Liz Smith wrote that Cohn told her about Hoover's rumored transvestism "long before it became common gossip."

Lavender Scare

The attorney Roy Cohn served as general counsel on the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations during Senator Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican Party (United States), Republican United States Senate, U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death at age ...

's tenure as chairman and assisted Hoover during the 1950s investigations of Communists and was generally known to be a closeted

''Closeted'' and ''in the closet'' are metaphors for LGBTQ people who have not disclosed their sexual orientation or gender identity and aspects thereof, including sexual identity and sexual behavior. This metaphor is associated and sometime ...

homosexual.[

] According to Richard Hack, Cohn's opinion was that Hoover was too frightened of his own sexuality to have anything approaching a normal sexual or romantic relationship.Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

to sign Executive Order 10450

President Dwight D. Eisenhower issued Executive Order 10450 on April 27, 1953. Effective May 27, 1953, it revoked President Truman's Executive Order 9835 of 1947 and dismantled its Loyalty Review Board program. Instead, it charged the heads ...

on April 29, 1953, that barred homosexuals from obtaining jobs at the federal level.

In his 2004 study of the event, historian David K. Johnson attacked the speculations about Hoover's homosexuality as relying on "the kind of tactics Hoover and the security program he oversaw perfected: guilt by association, rumor, and unverified gossip". He views Rosenstiel as a liar who was paid for her story, whose "description of Hoover in drag engaging in sex with young blond boys in leather while desecrating the Bible is clearly a homophobic

Homophobia encompasses a range of negative attitudes and feelings toward homosexuality or people who identify or are perceived as being lesbian, Gay men, gay or bisexual. It has been defined as contempt, prejudice, aversion, hatred, or ant ...

fantasy". He believes only those who have forgotten the virulence of the decades-long campaign against homosexuals in government can believe reports that Hoover appeared in compromising situations.

Supportive friends

Some people associated with Hoover have supported the rumors about his homosexuality.[

] According to Anthony Summers, Hoover often frequented New York City's Stork Club

Stork Club was a nightclub in Manhattan, New York City. During its existence from 1929 to 1965, it became one of the most prestigious clubs in the world. A symbol of café society, the wealthy elite, including movie stars, celebrities, showgi ...

. Luisa Stuart, a model who was 18 or 19 at the time, told Summers that she had seen Hoover holding hands with Tolson as they all rode in a limo uptown to the Cotton Club in 1936.[ Actress and singer ]Ethel Merman

Ethel Merman (born Ethel Agnes Zimmermann; January 16, 1908 – February 15, 1984) was an American singer and actress. Known for her distinctive, powerful voice, and her leading roles in musical theatre, musical theater,Obituary ''Variety Obitua ...

was a friend of Hoover's since 1938, and familiar with all parties during his alleged romance of Lela Rogers. In a 1978 interview and in response to Anita Bryant

Anita Jane Bryant (March 25, 1940 – December 16, 2024) was an American singer and anti-gay rights activist. She had three top 20 hits in the United States in the early 1960s. She was the 1958 Miss Oklahoma beauty pageant winner, and a brand ...

's anti-gay campaign, she said: "Some of my best friends are homosexual: Everybody knew about J. Edgar Hoover, but he was the best chief the FBI ever had."

Alleged African-American ancestry

Since the release of the 2011 film ''J. Edgar

''J. Edgar'' is a 2011 American Biographical film, biographical drama film based on the career of Federal Bureau of Investigation, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, directed, produced and scored by Clint Eastwood. Written by Dustin Lance Black, the ...

'', Hoover's genealogy has become a topic of interest. There are theories that Hoover had African-American heritage, which have been investigated and yet unsubstantiated.

Written works

Hoover was the nominal author of a number of books and articles, for which he received the credit and royalties, although it is widely believed that all of these were ghostwritten by FBI employees.

*

*

*

*

*

Honors

*1938: Oklahoma Baptist University awarded Hoover an honorary doctorate during commencement exercises, at which he spoke.

*1939: the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, NGO, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the ...

awarded Hoover its Public Welfare Medal

The Public Welfare Medal is awarded by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences "in recognition of distinguished contributions in the application of science to the public welfare." It is the most prestigious honor conferred by the academy. First awar ...

.[

]

*1950: King George VI of the United Kingdom appointed Hoover Honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire.

*1955: President Dwight D. Eisenhower awarded Hoover the National Security Medal

The National Security Medal is a decoration of the United States of America officially established by President Harry S. Truman in Executive Order 10431 of January 19, 1953. The medal was originally awarded to any person, without regard to natio ...

.Schaumburg, Illinois

Schaumburg ( ) is a village in Cook County, Illinois, Cook and DuPage County, Illinois, DuPage counties in the U.S. state of Illinois. Per the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 78,723, making Schaumburg the most populou ...

, a grade school was named after J. Edgar Hoover. However, in 1994, after information about Hoover's illegal activities was released, the school's name was changed to commemorate President Herbert Hoover instead.

Theater and media portrayals

Hoover has been portrayed by numerous actors in films and stage productions featuring him as FBI Director. The first known portrayal was by Kent Rogers in the 1941 Looney Tunes

''Looney Tunes'' is an American media franchise produced and distributed by Warner Bros. The franchise began as a series of animated short films that originally ran from 1930 to 1969, alongside its spin-off series ''Merrie Melodies'', during t ...

short " Hollywood Steps Out". Some notable portrayals (listed chronologically) include:

* Hoover portrayed himself (filmed from behind) in a cameo, addressing FBI agents in the 1959 film '' The FBI Story''.

* Dorothi Fox "portrayed" Hoover in disguise in the 1971 film ''Bananas