Inostrancevia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Inostrancevia'' is an

Among all the fossils Amalitsky described before his death are two remarkably complete skeletons of large

Among all the fossils Amalitsky described before his death are two remarkably complete skeletons of large

extinct

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

of large carnivorous

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose nutrition and energy requirements are met by consumption of animal tissues (mainly mu ...

therapsids which lived during the Late Permian

Late or LATE may refer to:

Everyday usage

* Tardy, or late, not being on time

* Late (or the late) may refer to a person who is dead

Music

* ''Late'' (The 77s album), 2000

* Late (Alvin Batiste album), 1993

* Late!, a pseudonym used by Dave Groh ...

in what is now European Russia

European Russia is the western and most populated part of the Russia, Russian Federation. It is geographically situated in Europe, as opposed to the country's sparsely populated and vastly larger eastern part, Siberia, which is situated in Asia ...

and Southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost region of Africa. No definition is agreed upon, but some groupings include the United Nations geoscheme for Africa, United Nations geoscheme, the intergovernmental Southern African Development Community, and ...

. The first-known fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

s of this gorgonopsia

Gorgonopsia (from the Greek Gorgon, a mythological beast, and 'aspect') is an extinct clade of Saber-toothed predator, sabre-toothed therapsids from the Middle Permian, Middle to the Upper Permian, roughly between 270 and 252 million years ago. ...

n were discovered in the context of a long series of excavations carried out from 1899 to 1914 in the Northern Dvina

The Northern Dvina (, ; ) is a river in northern Russia flowing through Vologda Oblast and Arkhangelsk Oblast into the Dvina Bay of the White Sea. Along with the Pechora River to the east, it drains most of Northwest Russia into the Arctic O ...

, Russia. Among these are two near-complete skeletons embodying the first described specimens of this genus, being also the first gorgonopsian identified in Russia. Several other fossil materials were discovered there, and the various finds led to confusion as to the exact number of valid species, before only two of them were formally recognized, namely ''I. alexandri'' and ''I. latifrons''. A third species, ''I. uralensis'', was erected in 1974, but the fossil remains of this taxon

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; : taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular name and ...

are very thin and could come from another genus. More recent research carried out in Southern Africa has discovered specimens identified as belonging to this genus, with the specimens from South Africa and Mozambique being classified within the species ''I. africana''. The genus name honors Alexander Inostrantsev, professor of Vladimir P. Amalitsky, the paleontologist who described the taxon

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; : taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular name and ...

.

Possessing a skull

The skull, or cranium, is typically a bony enclosure around the brain of a vertebrate. In some fish, and amphibians, the skull is of cartilage. The skull is at the head end of the vertebrate.

In the human, the skull comprises two prominent ...

measuring approximately long depending on the species, all for a body length reaching , ''Inostrancevia'' is the largest known gorgonopsian, being rivaled in size only by the imposing '' Rubidgea''. It has a broad and elongated skull equipped with large oval-shaped temporal fenestra

Temporal fenestrae are openings in the temporal region of the skull of some amniotes, behind the orbit (eye socket). These openings have historically been used to track the evolution and affinities of reptiles. Temporal fenestrae are commonly (al ...

e. It also has very advanced dentition, possessing large canines, the longest of which can reach and which may have been used to shear the skin of prey. Like most other gorgonopsians, ''Inostrancevia'' had a particularly large jaw

The jaws are a pair of opposable articulated structures at the entrance of the mouth, typically used for grasping and manipulating food. The term ''jaws'' is also broadly applied to the whole of the structures constituting the vault of the mouth ...

opening angle, which would have allowed it to inflict fatal bites. Gorgonopsians in general would have been relatively fast predators, killing their prey by delivering slashing bites with their saber teeth. The skeleton is robustly constructed, but new studies are necessary for a better anatomical description and understanding about its paleobiological

Paleobiology (or palaeobiology) is an interdisciplinary field that combines the methods and findings found in both the earth sciences and the life sciences. An investigator in this field is known as a paleobiologist.

Paleobiology is closely rel ...

functioning.

Gorgonopsians were a group of carnivorous

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose nutrition and energy requirements are met by consumption of animal tissues (mainly mu ...

stem mammals with saber teeth that disappeared at the end of the Permian. The first classifications placed ''Inostrancevia'' as close to African taxa before 1948, the year in which Friedrich von Huene erected a distinct family, Inostranceviidae. Although this model was mainly followed in the scientific literature

Scientific literature encompasses a vast body of academic papers that spans various disciplines within the natural and social sciences. It primarily consists of academic papers that present original empirical research and theoretical ...

of the 20th and early 21st centuries, phylogenetic analysis

In biology, phylogenetics () is the study of the evolutionary history of life using observable characteristics of organisms (or genes), which is known as phylogenetic inference. It infers the relationship among organisms based on empirical data ...

published since 2018 considers it to belong to a group of derived gorgonopsians of Russian origin, now classified alongside the genera '' Suchogorgon'', '' Sauroctonus'' and '' Pravoslavlevia'', this latter and ''Inostrancevia'' forming the subfamily

In biological classification, a subfamily (Latin: ', plural ') is an auxiliary (intermediate) taxonomic rank, next below family but more inclusive than genus. Standard nomenclature rules end botanical subfamily names with "-oideae", and zo ...

Inostranceviinae. Russian and African fossil records show that ''Inostrancevia'' lived in river ecosystems containing many tetrapod

A tetrapod (; from Ancient Greek :wiktionary:τετρα-#Ancient Greek, τετρα- ''(tetra-)'' 'four' and :wiktionary:πούς#Ancient Greek, πούς ''(poús)'' 'foot') is any four-Limb (anatomy), limbed vertebrate animal of the clade Tetr ...

s, where it appears to have been the main predator. These faunas were mainly occupied by dicynodont

Dicynodontia is an extinct clade of anomodonts, an extinct type of non-mammalian therapsid. Dicynodonts were herbivores that typically bore a pair of tusks, hence their name, which means 'two dog tooth'. Members of the group possessed a horny, t ...

s and pareiasaur

Pareiasaurs (meaning "cheek lizards") are an extinct clade of large, herbivorous parareptiles. Members of the group were armoured with osteoderms which covered large areas of the body. They first appeared in southern Pangea during the Middle Per ...

s, which would most likely have constituted its prey. In the Russian territory, ''Inostrancevia'' would have been the only large gorgonopsian present, while it would have been briefly contemporary with the rubidgeines in Tanzania. When the rubidgeines disappeared from South African territory, ''Inostrancevia'' would have in turn occupied the role of apex predator before disappearing in turn during the Permian-Triassic extinction.

Research history

Russian discoveries

During the 1890s, Russian paleontologist Vladimir Amalitsky discovered freshwater sediments dating from theUpper Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years, from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.902 Mya. It is the sixth and last period o ...

in Northern Dvina

The Northern Dvina (, ; ) is a river in northern Russia flowing through Vologda Oblast and Arkhangelsk Oblast into the Dvina Bay of the White Sea. Along with the Pechora River to the east, it drains most of Northwest Russia into the Arctic O ...

, Arkhangelsk Oblast

Arkhangelsk Oblast ( rus, Архангельская область, p=ɐrˈxanɡʲɪlʲskəjə ˈobɫəsʲtʲ) is a federal subjects of Russia, federal subject of Russia (an oblast). It includes the Arctic Ocean, Arctic archipelagos of Franz ...

, northern European Russia

European Russia is the western and most populated part of the Russia, Russian Federation. It is geographically situated in Europe, as opposed to the country's sparsely populated and vastly larger eastern part, Siberia, which is situated in Asia ...

. The locality, known as PIN 2005, consists of a creek with sandstone

Sandstone is a Clastic rock#Sedimentary clastic rocks, clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of grain size, sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate mineral, silicate grains, Cementation (geology), cemented together by another mineral. Sand ...

and lens

A lens is a transmissive optical device that focuses or disperses a light beam by means of refraction. A simple lens consists of a single piece of transparent material, while a compound lens consists of several simple lenses (''elements'') ...

-shaped exposures in a bank

A bank is a financial institution that accepts Deposit account, deposits from the public and creates a demand deposit while simultaneously making loans. Lending activities can be directly performed by the bank or indirectly through capital m ...

escarpment

An escarpment is a steep slope or long cliff that forms as a result of faulting or erosion and separates two relatively level areas having different elevations.

Due to the similarity, the term '' scarp'' may mistakenly be incorrectly used inte ...

, containing many particularly well-preserved fossil skeletons. This type of fauna from this period, previously known only from South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

and India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

, is considered as one of the greatest paleontological discoveries of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. After the preliminary reconnaissance of the place, Amalitsky conducts systematic research with his companion . The first excavations began in 1899, and several of her findings where sent to Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

, in order to be prepared there. The exhumations of the fossils then lasted until 1914, when the research stopped due to the start of the World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. When this event begins, Amalitsky tries to save his collection of fossils residing in Warsaw in order to transfer it to the Nizhny Novgorod

Nizhny Novgorod ( ; rus, links=no, Нижний Новгород, a=Ru-Nizhny Novgorod.ogg, p=ˈnʲiʐnʲɪj ˈnovɡərət, t=Lower Newtown; colloquially shortened to Nizhny) is a city and the administrative centre of Nizhny Novgorod Oblast an ...

oblast

An oblast ( or ) is a type of administrative division in Bulgaria and several post-Soviet states, including Belarus, Russia and Ukraine. Historically, it was used in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. The term ''oblast'' is often translated i ...

. However, the arrival of the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

in 1917 and the changing politics within the country indirectly led to his death in December of the same year. Subsequently, his fossil collection was transferred to Leningrad

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

and became an integral part of the geological department of the city's university. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, part of the fossils from the collection were transferred to the Paleontological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences

The Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS; ''Rossíyskaya akadémiya naúk'') consists of the national academy of Russia; a network of scientific research institutes from across the Russian Federation; and additional scientific and social units such ...

in Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

.

Among all the fossils Amalitsky described before his death are two remarkably complete skeletons of large

Among all the fossils Amalitsky described before his death are two remarkably complete skeletons of large gorgonopsia

Gorgonopsia (from the Greek Gorgon, a mythological beast, and 'aspect') is an extinct clade of Saber-toothed predator, sabre-toothed therapsids from the Middle Permian, Middle to the Upper Permian, roughly between 270 and 252 million years ago. ...

ns, since cataloged as PIN 1758 and PIN 2005/1578, in which he assigned within the new genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

and species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

''Inostranzevia alexandri''. The specimen PIN 2005/1578 is later recognized as its lectotype

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally associated. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes ...

. The taxon

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; : taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular name and ...

represents the first gorgonopsian to be identified in Russia, the fossils also preserving the first known near-complete postcranial remains identified in this group of therapsids. Although the animal was not officially described posthumously until 1922, the use of this name in scientific literature

Scientific literature encompasses a vast body of academic papers that spans various disciplines within the natural and social sciences. It primarily consists of academic papers that present original empirical research and theoretical ...

dates back to the beginning of the 20th century, notably in the works of Friedrich von Huene and Edwin Ray Lankester. Taxonomic issues regarding the original naming of the genus are the subject of a study which should be published later. Although the etymology

Etymology ( ) is the study of the origin and evolution of words—including their constituent units of sound and meaning—across time. In the 21st century a subfield within linguistics, etymology has become a more rigorously scientific study. ...

of the genus and type species

In International_Code_of_Zoological_Nomenclature, zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the spe ...

is not provided in the earliest-known descriptions of the taxon, the full name of the animal is named in honor of the renowned geologist , who was one of Amalitsky's teachers. Amalitsky's article generally describes all the fossil discoveries made in the Northern Dvina, and not ''Inostrancevia'' itself, the article mentioning that further research on this gorgonopsian was subject to research.

In 1927, one of Amalitsky's colleagues, Pavel Pravoslavlev, wrote two works, including a book, which are the first in-depth descriptions of the fossils today attributed to this taxon. In his works, Pravoslavlev changed the typography of the name "''Inostranzevia''" to "''Inostrancevia''". Although the original name has been used a few times in recent scientific literature

Scientific literature encompasses a vast body of academic papers that spans various disciplines within the natural and social sciences. It primarily consists of academic papers that present original empirical research and theoretical ...

, the second term has since entered into universal usage and must be maintained according to the rule of article 33.3.1 of the ICZN

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is a widely accepted convention in zoology that rules the formal scientific naming of organisms treated as animals. It is also informally known as the ICZN Code, for its formal author, t ...

. Among the many species of ''Inostrancevia'' erected and described on its part, only ''I. latifrons'' is found to be valid. The holotype of this species, cataloged PIN 2005/1857, consists of a large skull missing the lower jaw, discovered in the same locality as that of the first known specimens of ''I. alexandri''. Another skull was also discovered in the same locality as the holotype, while an incomplete skeleton was discovered in the village of Zavrazhye, located in Vladimir Oblast

Vladimir Oblast () is a federal subject of Russia (an oblast). Its administrative center is the city of Vladimir, which is located east of Moscow. As of the 2010 Census, the oblast's population was 1,443,693.

The UNESCO World Heritage L ...

. The specific name Specific name may refer to:

* in Database management systems, a system-assigned name that is unique within a particular database

In taxonomy, either of these two meanings, each with its own set of rules:

* Specific name (botany), the two-part (bino ...

''latifrons'' comes from the Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

''latus'' "broad" and ''frōns'' "forehead", in reference to the size and the more robust cranial constitution than that of ''I. alexandri''. In 1974, Leonid Petrovich Tatarinov carried out a large revision of the theriodont

The theriodonts (clade Theriodontia) are a major group of therapsids which appeared during the Middle Permian and which includes the gorgonopsians and the eutheriodonts, itself including the therocephalians and the cynodonts.

Naming

In 1876, ...

s then known in the USSR

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. In his work, he revises the validity of the taxa erected by Pravoslavlev and describes a third species of ''Inostrancevia'', ''I. uralensis'', on the basis of part of the skull. The holotype specimen, cataloged as PIN 2896/1, consists of a left basioccipital having been discovered in the locality of Blumental-3, located in the Orenburg Oblast

Orenburg Oblast (also Orenburzhye) is a federal subject of Russia (an oblast), mainly located in Eastern Europe. Its administrative center is the city of Orenburg. From 1938 to 1957, it bore the name Chkalov Oblast in honor of Valery Chkal ...

. The specific name ''uralensis'' refers to the Ural River

The Ural, also known as the Yaik , is a river flowing through Russia and Kazakhstan in the continental border between Europe and Asia. It originates in the southern Ural Mountains and discharges into the Caspian Sea. At , it is the third-longes ...

, where the holotype specimen of the taxon was found. However, due to its poor fossil preservation of this species, Tatarinov argues that it is possible that ''I. uralensis'' could belong to a new genus of large gorgonopsians.

African discoveries

In 2010, the Bloemfontein Museum sent an expedition to the farm of Nooitgedacht 68, located near the town of Bethulie, in the Karoo Basin, South Africa. It was during this same expedition that Nthaopa Ntheri discovered a partial skeleton of a large gorgonopsian which include an almost complete skull, cataloged as NMQR 4000. During a second expedition launched the following year,John Nyaphuli

Mosiuoa John Nyaphuli (March 12, 1933 The existence of these two specimens are mentioned in 2014 in the chapter of a work listing the discoveries made at this farm, but it was not until 2023 that Christian F. Kammerer and his colleagues made the first official description concerning these latter. Their descriptions unexpectedly confirm that these specimens belong to ''Inostrancevia'', which is a significant first given that the genus was historically only reported in Russia. The specimens nevertheless possessed some differences allowing them to be distinguished from the Russian lineages, they were then classified in the newly erected species ''I. africana'', the specimen NMQR 4000 being designated as the

''Inostrancevia'' is a gorgonopsian with a fairly robust morphology, the

''Inostrancevia'' is a gorgonopsian with a fairly robust morphology, the

The jaws of ''Inostrancevia'' are powerfully developed, equipped with teeth able to hold and tear the

The jaws of ''Inostrancevia'' are powerfully developed, equipped with teeth able to hold and tear the

From its original description published in 1922, ''Inostrancevia'' was immediately classified in the family Gorgonopsidae after anatomical comparisons made with the

From its original description published in 1922, ''Inostrancevia'' was immediately classified in the family Gorgonopsidae after anatomical comparisons made with the

One of the most recognizable characteristics of ''Inostrancevia'' (and other gorgonopsians, as well) is the presence of long, saber-like canines on the upper and lower jaws. How these animals would have used this dentition is debated. The bite force of saber-toothed predators (like ''Inostrancevia''), using three-dimensional analysis, was determined by Stephan Lautenschlager and colleagues in 2020. Their findings detailed that, despite morphological convergence among

One of the most recognizable characteristics of ''Inostrancevia'' (and other gorgonopsians, as well) is the presence of long, saber-like canines on the upper and lower jaws. How these animals would have used this dentition is debated. The bite force of saber-toothed predators (like ''Inostrancevia''), using three-dimensional analysis, was determined by Stephan Lautenschlager and colleagues in 2020. Their findings detailed that, despite morphological convergence among

''Inostrancevia'' is currently the only formally recognized gorgonopsian genus that had a transcontinental distribution, being present in both territories from which the group's fossils are unanimously recorded, namely in

''Inostrancevia'' is currently the only formally recognized gorgonopsian genus that had a transcontinental distribution, being present in both territories from which the group's fossils are unanimously recorded, namely in

In the Russian fossil record, ''Inostrancevia'' is currently the only large gorgonopsian to have been documented, with ''Pravoslavlevia'' being a smaller representative. In Tanzania, however, the taxon was coeval with a considerable number of other gorgonopsians, including even the large rubidgeines '' Dinogorgon'' and '' Rubidgea''. In South Africa, ''Inostrancevia'' would probably have occupied the place of the main apex predator after the extinction of the rubidgeines. However, it is possible that ''I. africana'' would not have been the only gorgonopsian to have been discovered on the Nooitgedacht 68 farm, because an indeterminate specimen belonging to this group is also listed there. Another specimen described in 2025 provides evidence that ''I. africana'' was also present in what is now Mozambique. In southern Africa, dicynodonts are the most abundant fossil tetrapods, while in the Russian archives only '' Vivaxosaurus'' is known. Apart from gorgonopsians, the genus was also contemporaneous with other

In the Russian fossil record, ''Inostrancevia'' is currently the only large gorgonopsian to have been documented, with ''Pravoslavlevia'' being a smaller representative. In Tanzania, however, the taxon was coeval with a considerable number of other gorgonopsians, including even the large rubidgeines '' Dinogorgon'' and '' Rubidgea''. In South Africa, ''Inostrancevia'' would probably have occupied the place of the main apex predator after the extinction of the rubidgeines. However, it is possible that ''I. africana'' would not have been the only gorgonopsian to have been discovered on the Nooitgedacht 68 farm, because an indeterminate specimen belonging to this group is also listed there. Another specimen described in 2025 provides evidence that ''I. africana'' was also present in what is now Mozambique. In southern Africa, dicynodonts are the most abundant fossil tetrapods, while in the Russian archives only '' Vivaxosaurus'' is known. Apart from gorgonopsians, the genus was also contemporaneous with other

holotype

A holotype (Latin: ''holotypus'') is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of s ...

of this species, while NMQR 3707 was bequeathed as a paratype

In zoology and botany, a paratype is a specimen of an organism that helps define what the scientific name of a species and other taxon actually represents, but it is not the holotype (and in botany is also neither an isotype (biology), isotype ...

. The specific name, meaning "Africa" in Latin, refers to the first proven presence of its kind within that continent. However, the article officially describing this animal focuses primarily on the stratigraphic

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock layers (strata) and layering (stratification). It is primarily used in the study of sedimentary and layered volcanic rocks.

Stratigraphy has three related subfields: lithost ...

significance of the findings and is only a brief introduction to the anatomy of the new fossil material, being the subject for future study. In 2018, fieldwork in the Metangula graben, Mozambique, uncovered a partial skull of a large gorgonopsian now numbered as PPM2018-7Z. In a 2025 paper, this specimen was identified as ''I. africana'' based on diagnosis provided by Kammerer and colleagues two years earlier. Additionally, in June 2007, a team of paleontologists discovered an isolated left premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammals h ...

, cataloged as NMT RB380, in the Ruhuhu Basin, southern Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

. The fossil bone was subsequently scanned and identified as ''Inostrancevia'' sp. in a 2024 study led by Anna J. Brant and Christian A. Sidor.

Synonyms and formerly assigned species

In his two works published in 1927, Pravoslavlev also named several additional gorgonopsian taxa. In their broad revision of the classification of therapsids published in 1956, David Watson and Alfred Romer recognized without argumentation almost all of the taxa erected by Pravoslavlev as valid, but their opinions were never followed in subsequent works. In addition of ''I. latifrons'', Pravoslavlev names and describes two additional species of the genus ''Inostrancevia'': ''I. parva'' and ''I. proclivis''. In 1940, the paleontologist Ivan Yefremov expressed doubts about this classification, and considered that the holotype specimen of ''I. parva'' should be viewed as a juvenile of the genus and not as a distinct species. It was in 1953 that Boris Pavlovich Vyuschkov completely revised the species named for ''Inostrancevia''. For ''I. parva'', he moves it to a new genus, which he names '' Pravoslavlevia'', in honor of the original author who named the species. Although being a distinct and valid genus, ''Pravoslavlevia'' turns out to be a closely related taxon. Also in his article, he considers that ''I. proclivis'' is a junior synonym of ''I. alexandri'', but remains open to the question of the existence of this species, arguing his opinion with the insufficient preservation of type specimens. This taxon will be definitively judged as being conspecific to ''I. alexandri'' in the revision of the genus carried out by Tatarinov in 1974. In the first work published earlier the same year, Pravoslavlev erected another genus of gorgonopsians, ''Amalitzkia'', with the type species ''A. annae''. In his larger work published subsequently, he erected a second species under the name of ''A. wladimiri''. The genus as well as the two species are named in honor of the couple of paleontologists who carried out the work on the first known specimens of ''I. alexandri''. In 1953, Vjuschkov discovered that the genus ''Amalitzkia'' is a junior synonym of ''Inostrancevia'', renaming ''A. wladimiri'' to ''I. wladimiri'', before the latter was itself recognized as a junior synonym of ''I. latifrons'' by later publications. For some unclear reason, Vjuschkov refers ''A. annae'' as a ''nomen nudum

In Taxonomy (biology), taxonomy, a ''nomen nudum'' ('naked name'; plural ''nomina nuda'') is a designation which looks exactly like a scientific name of an organism, and may have originally been intended to be one, but it has not been published ...

'', when his description is quite viable. Just like ''A. wladimiri'', ''A. annae'' will be synonymized with ''I. latifrons'' by Tatarinov in 1974.

In 2003, Mikhail F. Ivakhnenko erected a new genus of Russian gorgonopsian under the name of '' Leogorgon klimovensis'', on the basis of a partial braincase

In human anatomy, the neurocranium, also known as the braincase, brainpan, brain-pan, or brainbox, is the upper and back part of the skull, which forms a protective case around the brain. In the human skull, the neurocranium includes the calv ...

and a large referred canine, both discovered in the Klimovo-1 locality, in the Vologda Oblast

Vologda Oblast (, ; ) is a federal subjects of Russia, federal subject of Russia (an oblast). Its administrative center is Vologda. The oblast has a population of 1,202,444 (Russian Census (2010), 2010 Census). The largest city is Cherepovets, t ...

. In his official description, Ivakhnenko classifies this taxon among the subfamily Rubidgeinae, whose fossils are exclusively known from what is now Africa. This would therefore make ''Leogorgon'' the first known representative of this group to have lived outside this continent. In 2008, however, Ivakhnenko noted that, due to its poorly known anatomy, ''Leogorgon'' could be a relative of the Russian Phthinosuchidae rather than the sole Russian representative of the Rubidgeinae. In 2016, Kammerer formally rejected Ivakhnenko's classifications, because the holotype braincase of ''Leogorgon'' likely came from a dicynodont

Dicynodontia is an extinct clade of anomodonts, an extinct type of non-mammalian therapsid. Dicynodonts were herbivores that typically bore a pair of tusks, hence their name, which means 'two dog tooth'. Members of the group possessed a horny, t ...

, while the attributed canine tooth is indistinguishable from that of ''Inostrancevia''. Since then, ''Leogorgon'' has been recognized as a ''nomen dubium

In binomial nomenclature, a ''nomen dubium'' (Latin for "doubtful name", plural ''nomina dubia'') is a scientific name that is of unknown or doubtful application.

Zoology

In case of a ''nomen dubium,'' it may be impossible to determine whether a ...

'' of which part of the fossils possibly come from ''Inostrancevia''.

Other species belonging to distinct lineages were sometimes inadvertently classified in the genus ''Inostrancevia''. For example, in 1940, Efremov classifies a gorgonopsian of then-problematic status as ''I. progressus''. However, in 1955, Alexey Bystrow moved this species to the separate genus '' Sauroctonus''. A large maxilla

In vertebrates, the maxilla (: maxillae ) is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxil ...

discovered in Vladimir Oblast

Vladimir Oblast () is a federal subject of Russia (an oblast). Its administrative center is the city of Vladimir, which is located east of Moscow. As of the 2010 Census, the oblast's population was 1,443,693.

The UNESCO World Heritage L ...

in the 1950s was also assigned to ''Inostrancevia'', but the fossil would be reassigned to a large therocephalian in 1997, and later designated as the holotype of the genus '' Megawhaitsia'' in 2008.

Description

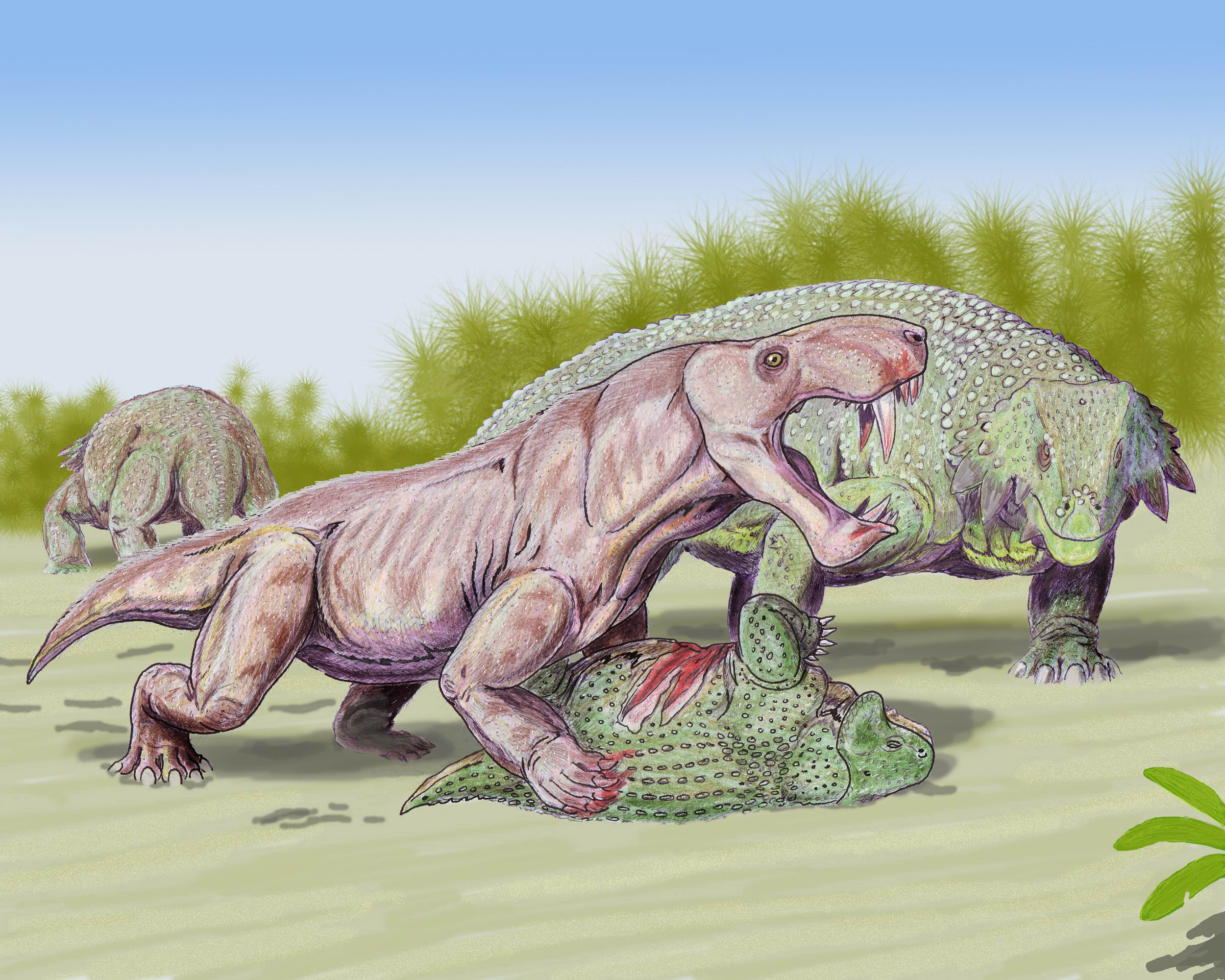

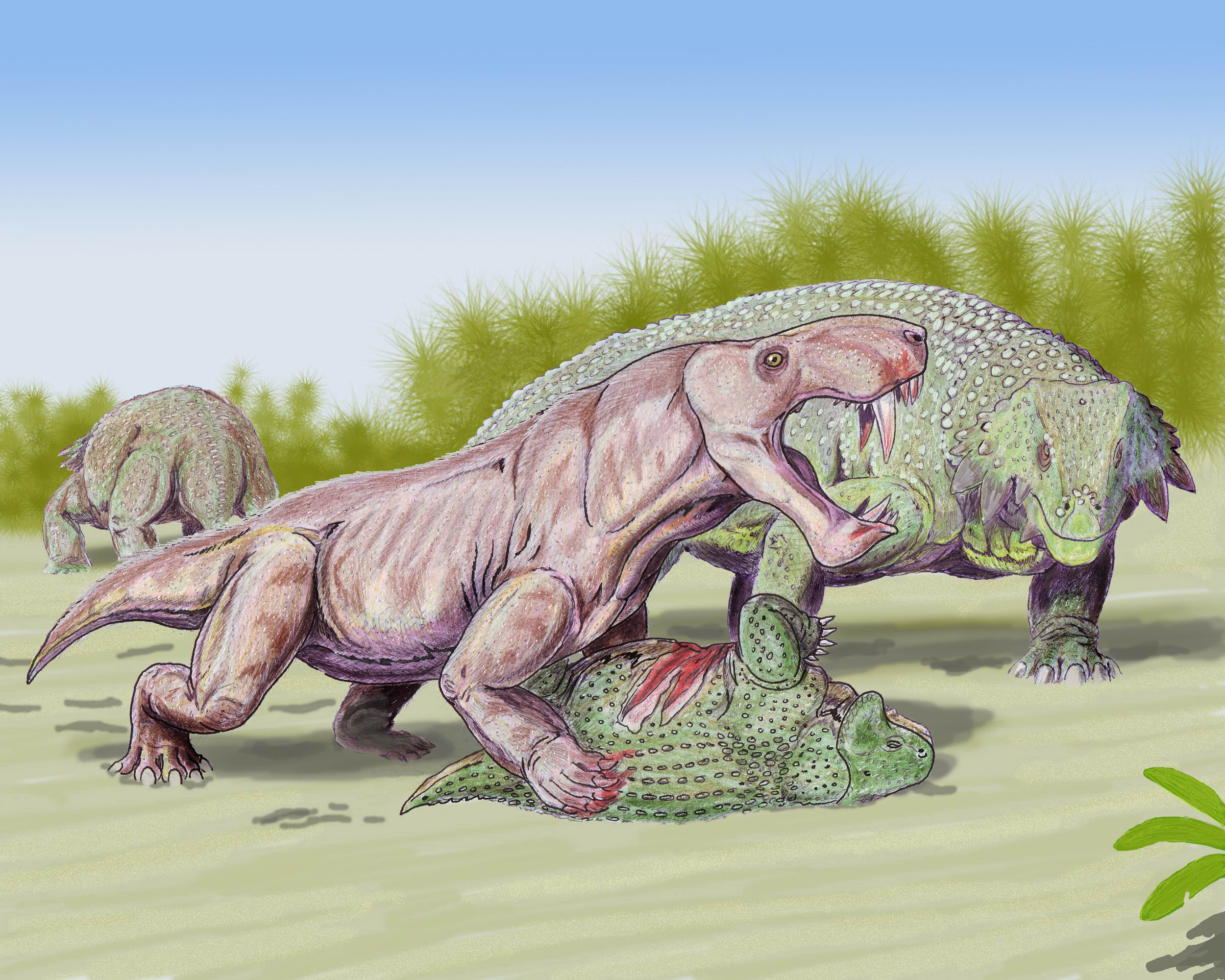

''Inostrancevia'' is a gorgonopsian with a fairly robust morphology, the

''Inostrancevia'' is a gorgonopsian with a fairly robust morphology, the Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many countries in the Americas

**Spanish cuisine

**Spanish history

**Spanish culture

...

paleoartist

Paleoart (also spelled palaeoart, paleo-art, or paleo art) is any original artistic work that attempts to depict prehistoric life according to scientific evidence.#Anson, Ansón, Fernández & Ramos (2015) pp. 28–34. Works of paleoart may be r ...

Mauricio Antón describing it as a "scaled-up version" of '' Lycaenops''. The numerous descriptions given to this taxon make it one of the most emblematic animals of the Permian period, mainly because of its large size among gorgonopsians, rivaled only by the South African genus '' Rubidgea'', the latter having a roughly similar size. Gorgonopsians were skeletally robust, yet long-limbed for therapsids, with a somewhat dog

The dog (''Canis familiaris'' or ''Canis lupus familiaris'') is a domesticated descendant of the gray wolf. Also called the domestic dog, it was selectively bred from a population of wolves during the Late Pleistocene by hunter-gatherers. ...

-like stance, though with outwards-turned elbows. It is unknown whether non-mammaliaform

Mammaliaformes ("mammalian forms") is a clade of synapsid tetrapods that includes the crown group mammals and their closest extinct relatives; the group radiated from earlier probainognathian cynodonts during the Late Triassic. It is defined a ...

therapsids such as gorgonopsians were covered in hair or not.

The specimens PIN 2005/1578 and PIN 1758, belonging to ''I. alexandri'', are among the largest and most complete gorgonopsian fossils identified to date. Both specimens are around long, with the skulls alone measuring over . However, ''I. latifrons'', although known from more fragmentary fossils, is estimated to have a more imposing size, the skull being long, indicating that it would have measured and weighed more than . The size of ''I. uralensis'' is unknown due to very incomplete fossils, but it appears to be smaller than ''I. latifrons''. The two known specimens of ''I. africana'' are among the largest gorgonopsians to have been discovered in Africa, the holotype skull measuring , while that of the paratype reaches . These proportions are matched only by the largest known specimens of ''Rubidgea''. Based on comparisons with various other gorgonopsians, the Tanzanian specimen of ''Inostrancevia'' would have had a skull with an estimated length of between long. However, the authors mention that it is difficult to know if the specimen would have been similar in size to those of recognized species.

Skull

The overall shape of the skull of ''Inostrancevia'' is similar to those of other gorgonopsians, i. e. long and narrow. It has a broad back skull, a raised and elongatedsnout

A snout is the protruding portion of an animal's face, consisting of its nose, mouth, and jaw. In many animals, the structure is called a muzzle, Rostrum (anatomy), rostrum, beak or proboscis. The wet furless surface around the nostrils of the n ...

, relatively small eye sockets and thin cranial arches. The pineal foramen

A parietal eye (third eye, pineal eye) is a part of the epithalamus in some vertebrates. The eye is at the top of the head; is photoreceptive; and is associated with the pineal gland, which regulates circadian rhythmicity and hormone production ...

is located near the posterior edge of the parietals and rests on a strong projection in the middle of an elongated hollow like impression. The sagittal suture

The sagittal suture, also known as the interparietal suture and the ''sutura interparietalis'', is a dense, fibrous connective tissue joint between the two parietal bones of the skull. The term is derived from the Latin word ''sagitta'', meaning ...

is reinforced with complex curvatures. The ventral surface of the palatine bone

In anatomy, the palatine bones (; derived from the Latin ''palatum'') are two irregular bones of the facial skeleton in many animal species, located above the uvula in the throat. Together with the maxilla, they comprise the hard palate.

Stru ...

s is completely smooth, lacking traces of palatine teeth or tubercle

In anatomy, a tubercle (literally 'small tuber', Latin for 'lump') is any round nodule, small eminence, or warty outgrowth found on external or internal organs of a plant or an animal.

In plants

A tubercle is generally a wart-like projectio ...

s. Just like '' Viatkogorgon'', the top margin of the quadrate is thickened. The dentary bone appear to have a clearly visible chin

The chin is the forward pointed part of the anterior mandible (List_of_human_anatomical_regions#Regions, mental region) below the lower lip. A fully developed human skull has a chin of between 0.7 cm and 1.1 cm.

Evolution

The presence of a we ...

-like structure. The four recognized species are distinguished by their own specific characteristics. ''I. alexandri'' is distinguished by its relatively narrow occiput

The occipital bone () is a cranial dermal bone and the main bone of the occiput (back and lower part of the skull). It is trapezoidal in shape and curved on itself like a shallow dish. The occipital bone lies over the occipital lobes of the ...

, a broad and rounded oval temporal fenestra

Temporal fenestrae are openings in the temporal region of the skull of some amniotes, behind the orbit (eye socket). These openings have historically been used to track the evolution and affinities of reptiles. Temporal fenestrae are commonly (al ...

and the transverse flangues of the pterygoid with teeth. ''I. latifrons'' is distinguished by a comparatively lower and broader snout, larger parietal region, fewer teeth and a less developed palatal

The palate () is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity.

A similar structure is found in crocodilians, but in most other tetrapods, the oral and nasal cavities are not truly sepa ...

tuberosities. ''I. uralensis'' is characterized by a transversely elongated oval slot-like temporal fenestra. ''I. africana'' is characterized by the strong constriction of the jugal under the orbit, a proportionally longer snout, the pineal foramen located in a deep parietal depression, as well as a much more raised and massive dentary bone.

skin

Skin is the layer of usually soft, flexible outer tissue covering the body of a vertebrate animal, with three main functions: protection, regulation, and sensation.

Other animal coverings, such as the arthropod exoskeleton, have different ...

of prey. The teeth are also devoid of cusps and can be distinguished into three types: the incisor

Incisors (from Latin ''incidere'', "to cut") are the front teeth present in most mammals. They are located in the premaxilla above and on the mandible below. Humans have a total of eight (two on each side, top and bottom). Opossums have 18, wher ...

s, the canines and the postcanines. All teeth are more or less laterally compressed and have finely serrated front and rear edges. When the mouth is closed, the upper canines move into position at the sides of the mandible

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone i ...

, reaching its lower edge. The canines of ''Inostrancevia'' measuring between and , they are among the largest identified among non-mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

ian therapsids, only the anomodont

Anomodontia is an extinct group of non-mammalian therapsids from the Permian and Triassic periods. By far the most speciose group are the dicynodonts, a clade of beaked, tusked herbivores. Anomodonts were very diverse during the Middle Pe ...

''Tiarajudens

''Tiarajudens'' () (" Tiaraju tooth") is an extinct genus of saber-toothed herbivorous anomodonts which lived during the Middle Permian period (Capitanian stage) in what is now Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. It is known from the holotype UFRGS ...

'' have similarly sized canines. In his 1927 description, Pravoslavlev describes the teeth of ''Inostrancevia'' as reminding him of those of the saber-toothed cat

Machairodontinae (from Ancient Greek μάχαιρα '' machaira,'' a type of Ancient Greek sword and ὀδόντος ''odontos'' meaning tooth) is an extinct subfamily of carnivoran mammals of the cat family Felidae, representing the earliest ...

''Machairodus

''Machairodus'' (from , 'knife' and 'tooth') is a genus of large Machairodontinae, machairodont or ''saber-toothed cat'' that lived in Africa and Eurasia during the Middle Miocene, Middle to Late Miocene, from 12.5 million to 8.7 million years ...

''. In the upper and lower jaws, these canines are roughly equal in size and are slightly curved. The incisors turn out to be very robust. A unique trait among gorgonopsians, ''Inostrancevia'' only has four incisors on the premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammals h ...

, unlike other representatives of the group who generally have five. The postcanine teeth are present on the upper jaw, on its slightly upturned alveolar edges. In contrast, they are completely absent from the lower jaw. There are indications that the tooth replacement would have taken place by the young teeth, growing at the root

In vascular plants, the roots are the plant organ, organs of a plant that are modified to provide anchorage for the plant and take in water and nutrients into the plant body, which allows plants to grow taller and faster. They are most often bel ...

of the old ones and gradually supplanting them. The capsule of the canines is very large, containing up to three capsules of replacement canines at different stages of development.

Postcranial skeleton

Although the postcranial anatomy of ''Inostrancevia'' was first described in detail in 1927 by Pravoslavlev, new discoveries and anatomical descriptions of this taxon have led authors suggesting further revisions to broaden the skeletal understanding of the animal. The skeleton of ''Inostrancevia'' is of very robust constitution, mainly at the level of the limbs. Theungual

An ungual (from Latin ''unguis'', i.e. ''nail'') is a highly modified distal toe bone which ends in a hoof, claw, or nail. Elephants and ungulates have ungual phalanges, as did the sauropod

Sauropoda (), whose members are known as sauropods (; ...

phalanges

The phalanges (: phalanx ) are digit (anatomy), digital bones in the hands and foot, feet of most vertebrates. In primates, the Thumb, thumbs and Hallux, big toes have two phalanges while the other Digit (anatomy), digits have three phalanges. ...

have an acute triangular shape. ''Inostrancevia'' has the most autapomorphic postcranial skeleton identified on a gorgonopsian. The scapula

The scapula (: scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on either side ...

of this latter is unmistakable, with an enlarged plate-like blade unlike that of any other known gorgonopsians, but its anatomy is also unusual, with ridges and thickened tibiae, especially at their joint margins. The scapular blade of ''Inostrancevia'' being extremely enlarged, its morphology will most likely be subject to future study regarding its paleobiological

Paleobiology (or palaeobiology) is an interdisciplinary field that combines the methods and findings found in both the earth sciences and the life sciences. An investigator in this field is known as a paleobiologist.

Paleobiology is closely rel ...

function.

Classification and evolution

From its original description published in 1922, ''Inostrancevia'' was immediately classified in the family Gorgonopsidae after anatomical comparisons made with the

From its original description published in 1922, ''Inostrancevia'' was immediately classified in the family Gorgonopsidae after anatomical comparisons made with the type genus

In biological taxonomy, the type genus (''genus typica'') is the genus which defines a biological family and the root of the family name.

Zoological nomenclature

According to the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, "The name-bearin ...

'' Gorgonops''. This classification was maintained as such until 1948, when von Huene established a separate family of gorgonopsians, Inostranceviidae, to include ''Inostrancevia''. Huene's opinion was generally shared in various studies published subsequently during the 20th century and even into the 21st century, although with some alternative classifications. In 1974, Tatarinov classified ''Pravoslavlevia'' as a sister taxon

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and ...

of ''Inostrancevia'' within this family. In 1989, Denise Sigogneau-Russell

Denise Sigogneau-Russell (born ''c.'' 1941/42) is a French palaeontologist who specialises in mammals from the Mesozoic, particularly from France and the UK. She is currently based at the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle.

Background

Denise S ...

proposes a similar classification, but moves the taxon reuniting the two genera as a subfamily, being renamed Inostranceviinae, and is classified in the more general family Gorgonopsidae. In 2002, in his revision of the Russian gorgonopsians, Mikhail F. Ivakhnenko re-erects the family Inostranceviidae and classifies the taxon as one of the lineages of the superfamily "Rubidgeoidea", placed alongside the Rubidgeidae and Phtinosuchidae. One year later, in 2003, he reclassifies ''Inostrancevia'' in the family Inostranceviidae, similar to Tatarinov's proposal, but the latter classifies it alone, making it a monotypic taxon

In biology, a monotypic taxon is a taxonomic group (taxon) that contains only one immediately subordinate taxon. A monotypic species is one that does not include subspecies or smaller, infraspecific taxa. In the case of Genus, genera, the term ...

.

In a 2007 unpublished thesis, German paleontologist Eva V. I. Gebauer carried out the very first phylogenetic analysis

In biology, phylogenetics () is the study of the evolutionary history of life using observable characteristics of organisms (or genes), which is known as phylogenetic inference. It infers the relationship among organisms based on empirical data ...

of gorgonopsians. Based on observations made on the occipital bone

The occipital bone () is a neurocranium, cranial dermal bone and the main bone of the occiput (back and lower part of the skull). It is trapezoidal in shape and curved on itself like a shallow dish. The occipital bone lies over the occipital lob ...

s and canines, Gebauer moved ''Inostrancevia'' as a sister taxon to the Rubidgeinae, a lineage consisting of robust African gorgonopsians. In 2016 Christian F. Kammerer regarded Gebauer's analysis as "unsatisfactory", citing that many of the characters used by her analysis were based upon skull proportions that are variable within taxa, both individually and ontogenetically (i.e. traits that change through growth). In 2018, in their description of '' Nochnitsa'' and re-description of the skull of ''Viatkogorgon'', Kammerer and Vladimir Masyutin propose that all Russian and African taxa should be separately grouped into two distinct clades. For Russian genera (except basal taxa), this relationship is supported by notable cranial traits, such as the close contact between the pterygoid and the vomer

The vomer (; ) is one of the unpaired facial bones of the skull. It is located in the midsagittal line, and articulates with the sphenoid, the ethmoid, the left and right palatine bones, and the left and right maxillary bones. The vomer forms ...

. The classification proposed by Kammerer and Masyutin will serve as the basis for all other subsequent phylogenetic studies of gorgonopsians. Using this model, the 2023 study by Kammerer and colleagues describing ''I. africana'' recovers it as a sister taxon to ''I. alexandri'' within the Russian origin clade. As with previous classifications, ''Pravoslavlevia'' is still recovered as the sister taxon of ''Inostrancevia''. The following cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek language, Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an Phylogenetic tree, evolutionary tree because it does not s ...

shows the position of ''Inostrancevia'' within the Gorgonopsia after Kammerer and Rubidge (2022):

Gorgonopsians are a major group of carnivorous therapsids, the oldest known definitive specimen coming from the Mediterranean island of Majorca

Mallorca, or Majorca, is the largest of the Balearic Islands, which are part of Spain, and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, seventh largest island in the Mediterranean Sea.

The capital of the island, Palma, Majorca, Palma, i ...

, and which probably dates to the early Middle Permian

The Guadalupian is the second and middle series/epoch of the Permian. The Guadalupian was preceded by the Cisuralian and followed by the Lopingian. It is named after the Guadalupe Mountains of New Mexico and Texas, and dates between 272.95 ± 0. ...

, or even earlier. During the Middle Permian, the majority of representatives of this clade were quite small and their ecosystems were mainly dominated by dinocephalia

Dinocephalians (terrible heads) are a clade of large-bodied early therapsids that flourished in the Early and Middle Permian between 279.5 and 260 million years ago (Ma), but became extinct during the Capitanian mass extinction event. ...

ns, large therapsids characterized by strong bone robustness. However, some genera, notably ''Phorcys

In Greek mythology, Phorcys or Phorcus (; ) is a primordial sea god, generally cited (first in Hesiod) as the son of Pontus and Gaia (Earth). Classical scholar Karl Kerenyi conflated Phorcys with the similar sea gods Nereus and Proteus. His w ...

'', are relatively larger in size and already occupy the role of superpredator in one of the oldest geological strata of the Karoo Supergroup

The Karoo Supergroup is the most widespread stratigraphic unit in Africa south of the Kalahari Desert. The supergroup consists of a sequence of units, mostly of nonmarine origin, deposited between the Late Carboniferous and Early Jurassic, a per ...

. Gorgonopsians were the first group of predatory animals to develop saber teeth, long before true mammals and dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

s evolved. This feature later evolved independently multiple times in different predatory mammal groups, such as felids and thylacosmilids. Geographically, gorgonopsians are mainly distributed in the present territories of Africa and European Russia, with, however, an indeterminate specimen having been identified in the Turpan Depression

The Turpan Depression or Turfan Depression, is a fault-bounded trough located around and south of the city-oasis of Turpan, in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region in far Western China, about southeast of the regional capital Ürümqi. It includes ...

, in north-west China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, as well as a possible fragmentary specimen discovered in the Kundaram Formation, located in central India. After the Capitanian extinction, gorgonopsians began to occupy ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of Resource (biology), resources an ...

s abandoned by dinocephalians and large therocephalia

Therocephalia is an extinct clade of therapsids (mammals and their close extinct relatives) from the Permian and Triassic periods. The therocephalians ("beast-heads") are named after their large skulls, which, along with the structure of their te ...

ns, and adopted an increasingly imposing size, which very quickly gave them the role of superpredators. In Africa, it is mainly the rubidgeines who occupy this role, while in Russia, only ''Inostrancevia'' acquires as such, the only known gorgonopsian and contemporary of this latter, ''Pravoslalevia'', being considerably smaller.

Paleobiology

Hunting strategy

One of the most recognizable characteristics of ''Inostrancevia'' (and other gorgonopsians, as well) is the presence of long, saber-like canines on the upper and lower jaws. How these animals would have used this dentition is debated. The bite force of saber-toothed predators (like ''Inostrancevia''), using three-dimensional analysis, was determined by Stephan Lautenschlager and colleagues in 2020. Their findings detailed that, despite morphological convergence among

One of the most recognizable characteristics of ''Inostrancevia'' (and other gorgonopsians, as well) is the presence of long, saber-like canines on the upper and lower jaws. How these animals would have used this dentition is debated. The bite force of saber-toothed predators (like ''Inostrancevia''), using three-dimensional analysis, was determined by Stephan Lautenschlager and colleagues in 2020. Their findings detailed that, despite morphological convergence among saber-toothed predator

A saber-tooth (alternatively spelled sabre-tooth) is any member of various extinct groups of predatory therapsids, predominantly carnivoran mammals, that are characterized by long, curved saber-shaped canine teeth which protruded from the mouth ...

s, there is a range of methods of possible killing techniques. The similarly-sized ''Rubidgea'' is capable of producing a bite force of 715 newtons

The newton (symbol: N) is the unit of force in the International System of Units (SI). Expressed in terms of SI base units, it is 1 kg⋅m/s2, the force that accelerates a mass of one kilogram at one metre per second squared.

The unit i ...

; although lacking the necessary jaw strength to crush bone, the analysis found that even the most massive gorgonopsians possessed a more powerful bite than other saber-toothed predators. The study also indicated that the jaw of ''Inostrancevia'' was capable of a massive gape, perhaps enabling it to deliver a lethal bite, and in a fashion similar to the hypothesised killing technique of ''Smilodon

''Smilodon'' is an extinct genus of Felidae, felids. It is one of the best known saber-toothed predators and prehistoric mammals. Although commonly known as the saber-toothed tiger, it was not closely related to the tiger or other modern cats ...

'' (or 'saber-toothed cat'). They also noted due to their effective jaw gape being below 60 degrees suggests their jaws were better built for inflicting damages on smaller or similar sized prey.

Antón provided an overview of gorgonopsian biology in is 2013 book, writing that despite their differences from saber-toothed mammals, many features of their skeletons indicated they were not sluggish reptiles but active predators. While their brains were relatively smaller than those of mammals, and their sideways placed eyes provided limited stereoscopic vision

Binocular vision is seeing with two eyes, which increases the size of the visual field. If the visual fields of the two eyes overlap, binocular depth can be seen. This allows objects to be recognized more quickly, camouflage to be detected, spa ...

, they had well-developed turbinals in their nasal cavity, a feature associated with an advanced sense of smell, which would have helped them track prey and carrion

Carrion (), also known as a carcass, is the decaying flesh of dead animals.

Overview

Carrion is an important food source for large carnivores and omnivores in most ecosystems. Examples of carrion-eaters (or scavengers) include crows, vultures ...

. The canine saber teeth were used for delivering the slashing killing-bite, while the incisors, which formed an arch in front of the saber teeth, held the prey and cut the flesh while feeding. To allow them to increase their gape when biting, gorgonopsians had several bones in their mandibles that could move in relation to each other and had a double articulation with the skull—unlike in mammals where the rear joint articular bone has become the malleus

The ''malleus'', or hammer, is a hammer-shaped small bone or ossicle of the middle ear. It connects with the incus, and is attached to the inner surface of the eardrum. The word is Latin for 'hammer' or 'mallet'. It transmits the sound vibra ...

ear bone. Antón envisioned gorgonopsians would hunt by leaving their cover when prey was close enough, and use their relatively greater speed to pounce quickly on it, grab it with their forelimbs, and bite any part of the body that would fit in their jaws. Such a bite would cause a large loss of blood, but the predator would continue to try to bite vulnerable parts of the body.

Motion

Antón stated in 2013 that while the post-cranial skeletons of gorgonopsians were basically reptilian, their stance was far more upright than in more primitive synapsids, likepelycosaur

Pelycosaur ( ) is an older term for basal or primitive Late Paleozoic synapsids, excluding the therapsids and their descendants. Previously, the term mammal-like reptile was used, and Pelycosauria was considered an order, but this is now thoug ...

s, which were more sprawling. Regular locomotion of gorgonopsians would have been similar to the "high walks" seen in crocodilia

Crocodilia () is an order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles that are known as crocodilians. They first appeared during the Late Cretaceous and are the closest living relatives of birds. Crocodilians are a type of crocodylomorph pseudosuchia ...

ns, wherein the belly is carried above the ground, with the feet pointing forwards, and the limbs carried under the trunk instead of to the sides. The forelimbs had a more horizontal posture than the hindlimbs, with the elbows pointing outwards during movement, but the gait of the hindlimbs would have resembled that of mammals. As in reptiles, the tail muscles (such as the caudofemoralis The caudofemoralis (from the Latin ''cauda'', tail and ''femur'', thighbone) is a muscle found in the pelvic limb of mostly all animals possessing a tail. It is thus found in nearly all tetrapods.

Location

The caudofemoralis spans plesiomorphica ...

) were important in flexion of the hindlimb, whereas the tails of mammals are merely for balance. Their feet were probably plantigrade

151px, Portion of a human skeleton, showing plantigrade habit

In terrestrial animals, plantigrade locomotion means walking with the toes and metatarsals flat on the ground. It is one of three forms of locomotion adopted by terrestrial mammals. ...

(where the soles were placed flat on the ground), though they were likely more swift and agile than their prey. Their feet were more symmetrical compared to the reptilian condition, making contact with the ground more efficient, similar to running mammals.

Palaeoecology

Paleoenvironment

''Inostrancevia'' is currently the only formally recognized gorgonopsian genus that had a transcontinental distribution, being present in both territories from which the group's fossils are unanimously recorded, namely in

''Inostrancevia'' is currently the only formally recognized gorgonopsian genus that had a transcontinental distribution, being present in both territories from which the group's fossils are unanimously recorded, namely in Southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost region of Africa. No definition is agreed upon, but some groupings include the United Nations geoscheme for Africa, United Nations geoscheme, the intergovernmental Southern African Development Community, and ...

and European Russia. In all the geological formations concerned, ''Inostrancevia'' would have been one if not the main apexpredator of these faunas, targeting a large majority of the tetrapod

A tetrapod (; from Ancient Greek :wiktionary:τετρα-#Ancient Greek, τετρα- ''(tetra-)'' 'four' and :wiktionary:πούς#Ancient Greek, πούς ''(poús)'' 'foot') is any four-Limb (anatomy), limbed vertebrate animal of the clade Tetr ...

s living alongside it, and more probably towards dicynodont

Dicynodontia is an extinct clade of anomodonts, an extinct type of non-mammalian therapsid. Dicynodonts were herbivores that typically bore a pair of tusks, hence their name, which means 'two dog tooth'. Members of the group possessed a horny, t ...

s and pareiasaur

Pareiasaurs (meaning "cheek lizards") are an extinct clade of large, herbivorous parareptiles. Members of the group were armoured with osteoderms which covered large areas of the body. They first appeared in southern Pangea during the Middle Per ...

s During the Late Permian

Late or LATE may refer to:

Everyday usage

* Tardy, or late, not being on time

* Late (or the late) may refer to a person who is dead

Music

* ''Late'' (The 77s album), 2000

* Late (Alvin Batiste album), 1993

* Late!, a pseudonym used by Dave Groh ...

when ''Inostrancevia'' lived, the Southern Urals (close in proximity to the Sokolki assemblage) were located around latitude 28– 34°N and defined as a " cold desert" dominated by fluvial

A river is a natural stream of fresh water that flows on land or inside caves towards another body of water at a lower elevation, such as an ocean, lake, or another river. A river may run dry before reaching the end of its course if it ru ...

deposits. The Salarevo Formation in particular (a horizon where the Russian species ''Inostrancevia'' hails from) was deposited in a seasonal, semi-arid

A semi-arid climate, semi-desert climate, or steppe climate is a aridity, dry climate sub-type. It is located on regions that receive precipitation below Evapotranspiration#Potential evapotranspiration, potential evapotranspiration, but not as l ...

-to-arid

Aridity is the condition of geographical regions which make up approximately 43% of total global available land area, characterized by low annual precipitation, increased temperatures, and limited water availability.Perez-Aguilar, L. Y., Plata ...

area with multiple shallow water lakes which was periodically flooded. The Paleoflora of much of European Russia at the time was dominated by a genus of peltaspermaceae

The Peltaspermales are an extinct order (biology), order of seed plants, often considered "Pteridospermatophyta, seed ferns". They span from the Late Carboniferous to the Early Jurassic or the Jurassic-Cretaceous Boundary. It includes at least on ...

n, ''Tatarina'', and other related genera, followed by ginkgophytes and conifers

Conifers () are a group of cone-bearing seed plants, a subset of gymnosperms. Scientifically, they make up the division Pinophyta (), also known as Coniferophyta () or Coniferae. The division contains a single extant class, Pinopsida. All e ...

. On the other hand, ferns

The ferns (Polypodiopsida or Polypodiophyta) are a group of vascular plants (plants with xylem and phloem) that reproduce via spores and have neither seeds nor flowers. They differ from mosses by being vascular, i.e., having specialized tissue ...

were relatively rare and sphenophytes were only locally present. There are also hygrophyte and halophyte

A halophyte is a salt-tolerant plant that grows in soil or waters of high salinity, coming into contact with saline water through its roots or by salt spray, such as in saline semi-deserts, mangrove swamps, marshes and sloughs, and seashores. ...

plants in coastal areas as well as conifers that are more resistant to drought and higher altitudes.. The Upper ''Daptocephalus'' Assemblage Zone in South Africa would have been a well-drained floodplain

A floodplain or flood plain or bottomlands is an area of land adjacent to a river. Floodplains stretch from the banks of a river channel to the base of the enclosing valley, and experience flooding during periods of high Discharge (hydrolog ...

. The Usili Formation in Tanzania corresponds to an alluvial plain

An alluvial plain is a plain (an essentially flat landform) created by the deposition of sediment over a long period by one or more rivers coming from highland regions, from which alluvial soil forms. A ''floodplain'' is part of the process, bei ...

which would have had numerous small meandering streams passing through well-vegetated floodplains. The basement of this formation would also have housed a generally high phreatic zone

The phreatic zone, saturated zone, or zone of saturation, is the part of an aquifer, below the water table

The water table is the upper surface of the phreatic zone or zone of saturation. The zone of saturation is where the pores and fractur ...

.

Contemporary fauna

In the Russian fossil record, ''Inostrancevia'' is currently the only large gorgonopsian to have been documented, with ''Pravoslavlevia'' being a smaller representative. In Tanzania, however, the taxon was coeval with a considerable number of other gorgonopsians, including even the large rubidgeines '' Dinogorgon'' and '' Rubidgea''. In South Africa, ''Inostrancevia'' would probably have occupied the place of the main apex predator after the extinction of the rubidgeines. However, it is possible that ''I. africana'' would not have been the only gorgonopsian to have been discovered on the Nooitgedacht 68 farm, because an indeterminate specimen belonging to this group is also listed there. Another specimen described in 2025 provides evidence that ''I. africana'' was also present in what is now Mozambique. In southern Africa, dicynodonts are the most abundant fossil tetrapods, while in the Russian archives only '' Vivaxosaurus'' is known. Apart from gorgonopsians, the genus was also contemporaneous with other

In the Russian fossil record, ''Inostrancevia'' is currently the only large gorgonopsian to have been documented, with ''Pravoslavlevia'' being a smaller representative. In Tanzania, however, the taxon was coeval with a considerable number of other gorgonopsians, including even the large rubidgeines '' Dinogorgon'' and '' Rubidgea''. In South Africa, ''Inostrancevia'' would probably have occupied the place of the main apex predator after the extinction of the rubidgeines. However, it is possible that ''I. africana'' would not have been the only gorgonopsian to have been discovered on the Nooitgedacht 68 farm, because an indeterminate specimen belonging to this group is also listed there. Another specimen described in 2025 provides evidence that ''I. africana'' was also present in what is now Mozambique. In southern Africa, dicynodonts are the most abundant fossil tetrapods, while in the Russian archives only '' Vivaxosaurus'' is known. Apart from gorgonopsians, the genus was also contemporaneous with other theriodont

The theriodonts (clade Theriodontia) are a major group of therapsids which appeared during the Middle Permian and which includes the gorgonopsians and the eutheriodonts, itself including the therocephalians and the cynodonts.

Naming

In 1876, ...

s, such as therocephalia

Therocephalia is an extinct clade of therapsids (mammals and their close extinct relatives) from the Permian and Triassic periods. The therocephalians ("beast-heads") are named after their large skulls, which, along with the structure of their te ...

ns (mainly akidnognathids) and numerous basal cynodont

Cynodontia () is a clade of eutheriodont therapsids that first appeared in the Late Permian (approximately 260 Megaannum, mya), and extensively diversified after the Permian–Triassic extinction event. Mammals are cynodonts, as are their extin ...

s such as ''Dvinia

''Dvinia'' is an extinct genus of cynodonts found in the Salarevo Formation of Sokolki on the Northern Dvina River near Kotlas in Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. It is the only known member of the family Dviniidae. Its fossil remains date from th ...

'' and ''Procynosuchus

''Procynosuchus'' (Greek: "Before dog crocodile") is an extinct genus of cynodonts from the Late Permian. It is considered to be one of the earliest and most basal (phylogenetics), basal cynodonts. It was 60 cm (2 ft) long.

Remains of ...

''. Exclusively in the Usili Formation, ''Inostrancevia'' would have been contemporary with biarmosuchia

Biarmosuchia is an extinct clade of non-mammalian synapsids from the Permian. Biarmosuchians are the most basal group of the therapsids. They were moderately-sized, lightly built carnivores, intermediate in form between basal sphenacodont " pel ...

ns of the genera '' Burnetia'' and '' Pembacephalus''. A number of other non-synapsid

Synapsida is a diverse group of tetrapod vertebrates that includes all mammals and their extinct relatives. It is one of the two major clades of the group Amniota, the other being the more diverse group Sauropsida (which includes all extant rept ...

tetrapods were contemporaneous with ''Inostrancevia''. Among sauropsid

Sauropsida ( Greek for "lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the class Reptilia, though typically used in a broader sense to also include extinct stem-group relatives of modern reptiles and birds (which, as theropod dino ...

s, pareiasaurs, notably ''Scutosaurus

''Scutosaurus'' ("shield lizard") is an extinct genus of pareiasaur parareptiles. Its genus name refers to large plates of armor scattered across its body. It was a large anapsid reptile that, unlike most reptiles, held its legs underneath its b ...

'', are the tetrapods most present in the Russian fossil record, although other representatives such as '' Anthodon'' and ''Pareiasaurus

''Pareiasaurus'' (from , "cheek" and , "lizard") is an extinct genus of Pareiasauromorpha, pareiasauromorph reptile from the Permian period. It was a typical member of its family (biology), family, the pareiasaurids, which take their name from th ...

'' are known in African formations. Contemporary archosauromorphs such as '' Aenigmastropheus'' and '' Proterosuchus'' have only been identified in Africa, respectively in Tanzania and South Africa. Contemporary temnospondyl

Temnospondyli (from Greek language, Greek τέμνειν, ''temnein'' 'to cut' and σπόνδυλος, ''spondylos'' 'vertebra') or temnospondyls is a diverse ancient order (biology), order of small to giant tetrapods—often considered Labyrinth ...

s include '' Dvinosaurus'' in Russia and '' Peltobatrachus'' in Tanzania. Reptiliomorph

Reptiliomorpha (meaning reptile-shaped; in PhyloCode known as ''Pan-Amniota'') is a clade containing the amniotes and those tetrapods that share a more recent common ancestor with amniotes than with living amphibians (lissamphibians). It was defi ...

s like '' Chroniosuchus'' and '' Kotlassia'' have been identified in Russia.

Extinction

Gorgonopsians, including ''Inostrancevia'', disappeared in the LateLopingian

The Lopingian is the uppermost series/last epoch of the Permian. It is the last epoch of the Paleozoic. The Lopingian was preceded by the Guadalupian and followed by the Early Triassic.

The Lopingian is often synonymous with the informal te ...

during the Permian–Triassic extinction event

The Permian–Triassic extinction event (also known as the P–T extinction event, the Late Permian extinction event, the Latest Permian extinction event, the End-Permian extinction event, and colloquially as the Great Dying,) was an extinction ...

, mainly due to volcanic activities that originated in the Siberian Traps

The Siberian Traps () are a large region of volcanic rock, known as a large igneous province, in Siberia, Russia. The massive eruptive event that formed the trap rock, traps is one of the largest known Volcano, volcanic events in the last years ...

. The resulting eruption caused a significant climatic disruption unfavorable to their survival, leading to their extinction. Their ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.