Indigenous languages of the Americas on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Indigenous languages of the Americas are the

There are approximately 296 spoken (or formerly spoken) Indigenous languages north of Mexico, 269 of which are grouped into 29 families (the remaining 27 languages are either isolates or unclassified). The Na-Dené, Algic, and Uto-Aztecan families are the largest in terms of number of languages. Uto-Aztecan has the most speakers (1.95 million) if the languages in Mexico are considered (mostly due to 1.5 million speakers of

There are approximately 296 spoken (or formerly spoken) Indigenous languages north of Mexico, 269 of which are grouped into 29 families (the remaining 27 languages are either isolates or unclassified). The Na-Dené, Algic, and Uto-Aztecan families are the largest in terms of number of languages. Uto-Aztecan has the most speakers (1.95 million) if the languages in Mexico are considered (mostly due to 1.5 million speakers of

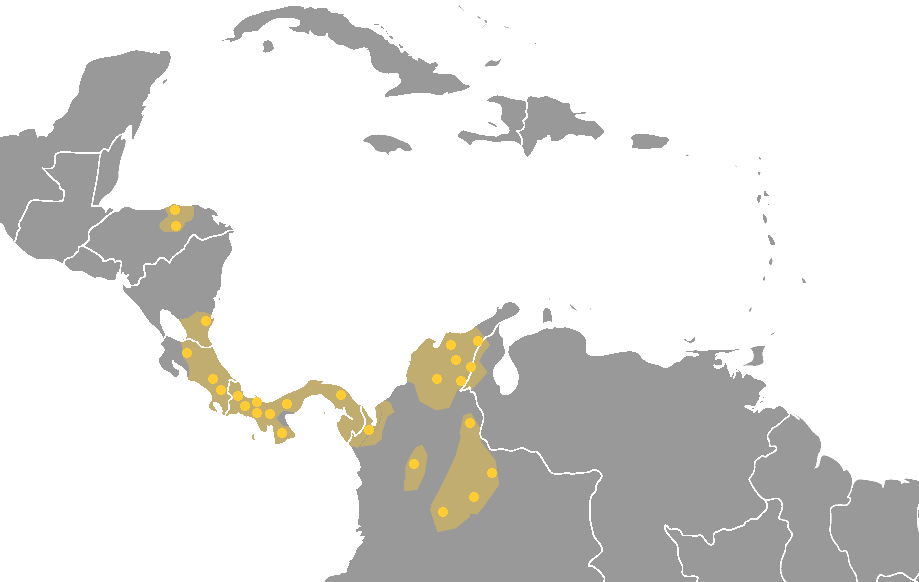

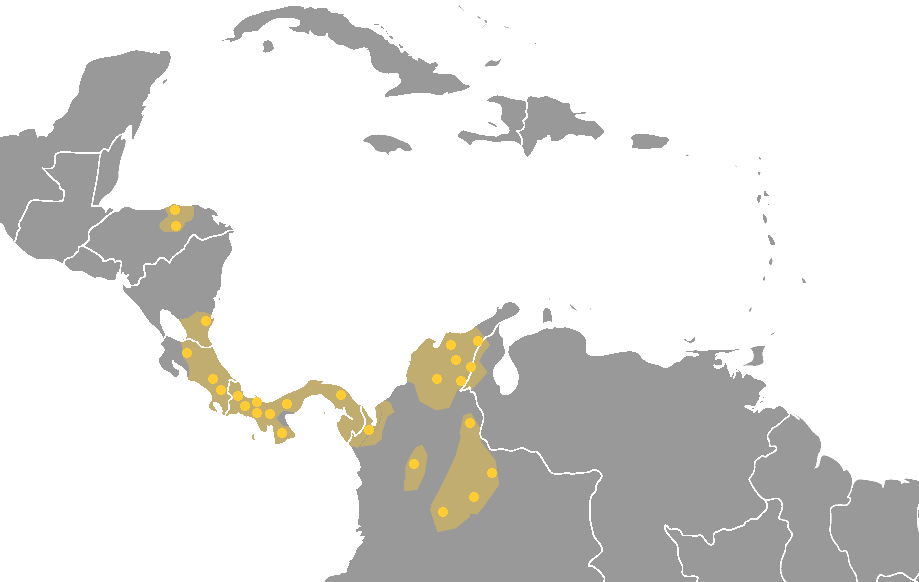

In Central America the Mayan languages are among those used today. Mayan languages are spoken by at least six million Indigenous Maya, primarily in Guatemala, Mexico, Belize and Honduras. In 1996, Guatemala formally recognized 21 Mayan languages by name, and Mexico recognizes eight more. The Mayan language family is one of the best documented and most studied in the Americas. Modern Mayan languages descend from Proto-Mayan, a language thought to have been spoken at least 4,000 years ago; it has been partially reconstructed using the comparative method.

* Alagüilac ''(Guatemala)'' ''†''

* Chibchan (

In Central America the Mayan languages are among those used today. Mayan languages are spoken by at least six million Indigenous Maya, primarily in Guatemala, Mexico, Belize and Honduras. In 1996, Guatemala formally recognized 21 Mayan languages by name, and Mexico recognizes eight more. The Mayan language family is one of the best documented and most studied in the Americas. Modern Mayan languages descend from Proto-Mayan, a language thought to have been spoken at least 4,000 years ago; it has been partially reconstructed using the comparative method.

* Alagüilac ''(Guatemala)'' ''†''

* Chibchan (

Although both North and

Although both North and

Debian North American Indigenous Languages Project

Catálogo de línguas indígenas sul-americanas

Diccionario etnolingüístico y guía bibliográfica de los pueblos indígenas sudamericanos

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20180929134719/http://www.athenapub.com/salang1.htm South American Languages

Indigenous Peoples Languages: Articles, News, Videos

Documentation Center of the Linguistic Minorities of Panama

The Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America

Indigenous Language Institute

The Society for the Study of the Indigenous Languages of the Americas

(SSILA)

(collection of ethnographic, linguistic, & historical material)

* ttp://www.albany.edu/anthro/maldp/ Project for the Documentation of the Languages of Mesoamerica

Programa de Formación en Educación Intercultural Bilingüe para los Países Andinos

(University of California at Davis)

Native Languages of the Americas

(Saskatchewan Indian Cultural Centre)

Alaska Native Language Center

{{DEFAULTSORT:Indigenous Languages Of The Americas Languages

language

Language is a structured system of communication that consists of grammar and vocabulary. It is the primary means by which humans convey meaning, both in spoken and signed language, signed forms, and may also be conveyed through writing syste ...

s that were used by the Indigenous peoples of the Americas

In the Americas, Indigenous peoples comprise the two continents' pre-Columbian inhabitants, as well as the ethnic groups that identify with them in the 15th century, as well as the ethnic groups that identify with the pre-Columbian population of ...

before the arrival of non-Indigenous peoples. Over a thousand of these languages are still used today, while many more are now extinct

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

. The Indigenous languages of the Americas are not all related to each other; instead, they are classified into a hundred or so language families

A language family is a group of languages related through descent from a common ancestor, called the proto-language of that family. The term ''family'' is a metaphor borrowed from biology, with the tree model used in historical linguistics ana ...

and isolates, as well as several extinct languages that are unclassified due to the lack of information on them.

Many proposals have been made to relate some or all of these languages to each other, with varying degrees of success. The most widely reported is Joseph Greenberg's Amerind hypothesis, which, however, nearly all specialists reject because of severe methodological flaws; spurious data; and a failure to distinguish cognation, contact, and coincidence.

According to UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

, most of the Indigenous languages of the Americas are critically endangered, and many are dormant (without native speakers but with a community of heritage-language users) or entirely extinct.. (Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com) The most widely spoken Indigenous languages are Southern Quechua (spoken primarily in southern Peru and Bolivia) and Guarani (centered in Paraguay, where it shares national language status with Spanish), with perhaps six or seven million speakers apiece (including many of European descent in the case of Guarani). Only half a dozen others have more than a million speakers; these are Aymara of Bolivia and Nahuatl

Nahuatl ( ; ), Aztec, or Mexicano is a language or, by some definitions, a group of languages of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Varieties of Nahuatl are spoken by about Nahuas, most of whom live mainly in Central Mexico and have smaller popul ...

of Mexico, with almost two million each; the Mayan languages Kekchi and K’iche’ of Guatemala and Yucatec of Mexico, with about 1 million apiece; and perhaps one or two additional Quechuan languages in Peru and Ecuador. In the United States, 372,000 people reported speaking an Indigenous language at home in the 2010 census. In Canada, 133,000 people reported speaking an Indigenous language at home in the 2011 census. In Greenland, about 90% of the population speaks Greenlandic, the most widely spoken Eskaleut language.

Background

Over a thousand known languages were spoken by various peoples in North and South America prior to their first contact with Europeans. These encounters occurred between the beginning of the 11th century (with the Nordic settlement ofGreenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

and failed efforts in Newfoundland and Labrador

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the populatio ...

) and the end of the 15th century (the voyages of Christopher Columbus). Several Indigenous cultures of the Americas had also developed their own writing system

A writing system comprises a set of symbols, called a ''script'', as well as the rules by which the script represents a particular language. The earliest writing appeared during the late 4th millennium BC. Throughout history, each independen ...

s, the best known being the Maya script. The Indigenous languages of the Americas had widely varying demographics, from the Quechuan languages, Aymara, Guarani, and Nahuatl

Nahuatl ( ; ), Aztec, or Mexicano is a language or, by some definitions, a group of languages of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Varieties of Nahuatl are spoken by about Nahuas, most of whom live mainly in Central Mexico and have smaller popul ...

, which had millions of active speakers, to many languages with only several hundred speakers. After pre-Columbian times, several Indigenous creole language

A creole language, or simply creole, is a stable form of contact language that develops from the process of different languages simplifying and mixing into a new form (often a pidgin), and then that form expanding and elaborating into a full-fl ...

s developed in the Americas, based on European, Indigenous and African languages.

The European colonizing nations and their successor states had widely varying attitudes towards Native American languages. In Brazil, friars learned and promoted the Tupi language. In many Spanish colonies, Spanish missionaries often learned local languages and culture in order to preach to the natives in their own tongue and relate the Christian message to their Indigenous religions. In the British American colonies, John Eliot of the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1628–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around Massachusetts Bay, one of the several colonies later reorganized as the Province of M ...

translated the Bible into the Massachusett language, also called Wampanoag, or Natick (1661–1663); he published the first Bible printed in North America, the '' Eliot Indian Bible''.

The Europeans also suppressed use of Indigenous languages, establishing their own languages for official communications, destroying texts in other languages, and insisted that Indigenous people learn European languages in schools. As a result, Indigenous languages suffered from cultural suppression and loss of speakers. By the 18th and 19th centuries, Spanish, English, Portuguese, French, and Dutch, brought to the Americas by European settlers and administrators, had become the official or national languages of modern nation-states of the Americas.

Many Indigenous languages have become critically endangered, but others are vigorous and part of daily life for millions of people. Several Indigenous languages have been given official status in the countries where they occur, such as Guaraní in Paraguay

Paraguay, officially the Republic of Paraguay, is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the Argentina–Paraguay border, south and southwest, Brazil to the Brazil–Paraguay border, east and northeast, and Boli ...

. In other cases official status is limited to certain regions where the languages are most spoken. Although sometimes enshrined in constitutions as official, the languages may be used infrequently in ''de facto'' official use. Examples are Quechua in Peru and Aymara in Bolivia, where in practice, Spanish is dominant in all formal contexts.

In the North American Arctic region, Greenland in 2009 elected Kalaallisut as its sole official language. In the United States, the Navajo language is the most spoken Native American language, with more than 200,000 speakers in the Southwestern United States. The US Marine Corps recruited Navajo men, who were established as code talkers

A code talker was a person employed by the military during wartime to use a little-known language as a means of secret communication. The term is most often used for United States service members during the World Wars who used their knowledge ...

during World War II.

Origins

In ''American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America'' (1997), Lyle Campbell lists several hypotheses for the historical origins of Amerindian languages. * A single, one-language migration (not widely accepted) * A few linguistically distinct migrations (favored by Edward Sapir) * Multiple migrations * Multilingual migrations (single migration with multiple languages) * The influx of already diversified but related languages from the Old World * Extinction of Old World linguistic relatives (while the New World ones survived) * Migration along the Pacific coast instead of by the Bering Strait Roger Blench (2008) has advocated the theory of multiple migrations along the Pacific coast of peoples from northeastern Asia, who already spoke diverse languages. These proliferated in the New World.Numbers of speakers and political recognition

Countries like Mexico, Bolivia, Venezuela, Guatemala, and Guyana recognize most Indigenous languages. Bolivia and Venezuela give all Indigenous languages official status. Canada, Argentina, and the U.S. allow provinces and states to decide. Brazil limits recognition to localities. * Bolivia: Official status for all Indigenous languages. * Venezuela: Official status for all Indigenous languages. * Mexico: Recognizes all Indigenous languages. * Guatemala: Recognizes all Indigenous languages. * Guyana: Recognizes most Indigenous languages. * Colombia: Local recognition at the department level. * Canada: Bill C-91 Indigenous Languages Act and Indigenous languages recognition in Parliament. * Argentina: Provincial determination of language policies. * United States: State determination of language policies. * Brazil: Local recognition of Indigenous languages. Canada Bill C-91, passed in 2019, supports Indigenous languages through sustainable funding and the Office of the Commissioner of Indigenous Languages. The first Commissioner of Indigenous languages in Canada is Ronald E. Ignace. Colombia Colombia delegates local Indigenous language recognition to the department level according to the Colombian Constitution of 1991. * Bullet points represent minority language status. Political entities withofficial language

An official language is defined by the Cambridge English Dictionary as, "the language or one of the languages that is accepted by a country's government, is taught in schools, used in the courts of law, etc." Depending on the decree, establishmen ...

status are highlighted in bold.

Language families and unclassified languages

Notes: * Extinct languages or families are indicated by: ''†''. * The number of family members is indicated in parentheses (for example, Arauan (9) means the Arauan family consists of nine languages). * For convenience, the following list of language families is divided into three sections based on political boundaries of countries. These sections correspond roughly with the geographic regions (North, Central, and South America) but are not equivalent. This division cannot fully delineate Indigenous culture areas.Northern America

There are approximately 296 spoken (or formerly spoken) Indigenous languages north of Mexico, 269 of which are grouped into 29 families (the remaining 27 languages are either isolates or unclassified). The Na-Dené, Algic, and Uto-Aztecan families are the largest in terms of number of languages. Uto-Aztecan has the most speakers (1.95 million) if the languages in Mexico are considered (mostly due to 1.5 million speakers of

There are approximately 296 spoken (or formerly spoken) Indigenous languages north of Mexico, 269 of which are grouped into 29 families (the remaining 27 languages are either isolates or unclassified). The Na-Dené, Algic, and Uto-Aztecan families are the largest in terms of number of languages. Uto-Aztecan has the most speakers (1.95 million) if the languages in Mexico are considered (mostly due to 1.5 million speakers of Nahuatl

Nahuatl ( ; ), Aztec, or Mexicano is a language or, by some definitions, a group of languages of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Varieties of Nahuatl are spoken by about Nahuas, most of whom live mainly in Central Mexico and have smaller popul ...

); Na-Dené comes in second with approximately 200,000 speakers (nearly 180,000 of these are speakers of Navajo), and Algic in third with about 180,000 speakers (mainly Cree

The Cree, or nehinaw (, ), are a Indigenous peoples of the Americas, North American Indigenous people, numbering more than 350,000 in Canada, where they form one of the country's largest First Nations in Canada, First Nations. They live prim ...

and Ojibwe

The Ojibwe (; Ojibwe writing systems#Ojibwe syllabics, syll.: ᐅᒋᐺ; plural: ''Ojibweg'' ᐅᒋᐺᒃ) are an Anishinaabe people whose homeland (''Ojibwewaki'' ᐅᒋᐺᐘᑭ) covers much of the Great Lakes region and the Great Plains, n ...

). Na-Dené and Algic have the widest geographic distributions: Algic currently spans from northeastern Canada across much of the continent down to northeastern Mexico (due to later migrations of the Kickapoo) with two outliers in California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

( Yurok and Wiyot); Na-Dené spans from Alaska and western Canada through Washington, Oregon

Oregon ( , ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is a part of the Western U.S., with the Columbia River delineating much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while t ...

, and California to the U.S. Southwest and northern Mexico (with one outlier in the Plains). Several families consist of only 2 or 3 languages. Demonstrating genetic relationships has proved difficult due to the great linguistic diversity present in North America. Two large (super-) family proposals, Penutian

Penutian is a proposed grouping of language family, language families that includes many Native Americans in the United States, Native American languages of western North America, predominantly spoken at one time in British Columbia, Washington ( ...

and Hokan, look particularly promising. However, even after decades of research, a large number of families remain.

North America is notable for its linguistic diversity, especially in California. This area has 18 language families comprising 74 languages (compared to five families in Europe: Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the northern Indian subcontinent, most of Europe, and the Iranian plateau with additional native branches found in regions such as Sri Lanka, the Maldives, parts of Central Asia (e. ...

, Uralic, Turkic, Kartvelian, and Afroasiatic and one isolate, Basque

Basque may refer to:

* Basques, an ethnic group of Spain and France

* Basque language, their language

Places

* Basque Country (greater region), the homeland of the Basque people with parts in both Spain and France

* Basque Country (autonomous co ...

).

Another area of considerable diversity appears to have been the Southeastern Woodlands; however, many of these languages became extinct from European contact and as a result they are, for the most part, absent from the historical record. This diversity has influenced the development of linguistic theories and practice in the US.

Due to the diversity of languages in North America, it is difficult to make generalizations for the region. Most North American languages have a relatively small number of vowels (i.e. three to five vowels). Languages of the western half of North America often have relatively large consonant inventories. The languages of the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (PNW; ) is a geographic region in Western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though no official boundary exists, the most common ...

are notable for their complex phonotactics

Phonotactics (from Ancient Greek 'voice, sound' and 'having to do with arranging') is a branch of phonology that deals with restrictions in a language on the permissible combinations of phonemes. Phonotactics defines permissible syllable struc ...

(for example, some languages have words that lack vowel

A vowel is a speech sound pronounced without any stricture in the vocal tract, forming the nucleus of a syllable. Vowels are one of the two principal classes of speech sounds, the other being the consonant. Vowels vary in quality, in loudness a ...

s entirely). The languages of the Plateau

In geology and physical geography, a plateau (; ; : plateaus or plateaux), also called a high plain or a tableland, is an area of a highland consisting of flat terrain that is raised sharply above the surrounding area on at least one side. ...

area have relatively rare pharyngeals and epiglottals (they are otherwise restricted to Afroasiatic languages

The Afroasiatic languages (also known as Afro-Asiatic, Afrasian, Hamito-Semitic, or Semito-Hamitic) are a language family (or "phylum") of about 400 languages spoken predominantly in West Asia, North Africa, the Horn of Africa, and parts of th ...

and the languages of the Caucasus). Ejective consonants are also common in western North America, although they are rare elsewhere (except, again, for the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region spanning Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising parts of Southern Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The Caucasus Mountains, i ...

region, parts of Africa, and the Mayan family).

Head-marking is found in many languages of North America (as well as in Central and South America), but outside of the Americas it is rare. Many languages throughout North America are polysynthetic ( Eskaleut languages are extreme examples), although this is not characteristic of all North American languages (contrary to what was believed by 19th-century linguists). Several families have unique traits, such as the inverse number marking of the Tanoan languages, the lexical affix

In linguistics, an affix is a morpheme that is attached to a word stem to form a new word or word form. The main two categories are Morphological derivation, derivational and inflectional affixes. Derivational affixes, such as ''un-'', ''-ation' ...

es of the Wakashan, Salishan and Chimakuan languages, and the unusual verb structure of Na-Dené.

The classification below is a composite of Goddard (1996), Campbell (1997), and Mithun (1999).

* Adai ''†''

* Algic (30)

* Alsea (2) ''†''

* Atakapa ''†''

* Beothuk ''†''

* Caddoan (5)

* Cayuse ''†''

* Chimakuan (2) ''†''

* Chimariko ''†''

* Chinookan (3) ''†''

* Chitimacha ''†''

* Chumashan (6) ''†''

* Coahuilteco ''†''

* Comecrudan (United States & Mexico) (3) ''†''

* Coosan (2) ''†''

* Cotoname ''†''

* Eskaleut (7)

* Esselen ''†''

* Haida

* Iroquoian (11)

* Kalapuyan (3) ''†''

* Karankawa ''†''

* Karuk

* Keresan (2)

* Kutenai

* Maiduan (4)

* Muskogean (9)

* Na-Dené (United States, Canada & Mexico) (39)

* Natchez ''†''

* Palaihnihan (2) ''†''

* Plateau Penutian (4)

* Pomoan (7)

* Salinan ''†''

* Salishan (23)

* Shastan (4) ''†''

* Siouan (19)

* Siuslaw ''†''

* Solano ''†''

* Takelma ''†''

* Tanoan (7)

* Timucua ''†''

* Tonkawa ''†''

* Tsimshianic (2)

* Tunica ''†''

* Utian (15)

* Uto-Aztecan (33)

* Wakashan (7)

* Wappo ''†''

* Washo

* Wintuan (4)

* Yana ''†''

* Yokutsan (3)

* Yuchi ''†''

* Yuki ''†''

* Yuman–Cochimí (11)

* Zuni

Central America and Mexico

In Central America the Mayan languages are among those used today. Mayan languages are spoken by at least six million Indigenous Maya, primarily in Guatemala, Mexico, Belize and Honduras. In 1996, Guatemala formally recognized 21 Mayan languages by name, and Mexico recognizes eight more. The Mayan language family is one of the best documented and most studied in the Americas. Modern Mayan languages descend from Proto-Mayan, a language thought to have been spoken at least 4,000 years ago; it has been partially reconstructed using the comparative method.

* Alagüilac ''(Guatemala)'' ''†''

* Chibchan (

In Central America the Mayan languages are among those used today. Mayan languages are spoken by at least six million Indigenous Maya, primarily in Guatemala, Mexico, Belize and Honduras. In 1996, Guatemala formally recognized 21 Mayan languages by name, and Mexico recognizes eight more. The Mayan language family is one of the best documented and most studied in the Americas. Modern Mayan languages descend from Proto-Mayan, a language thought to have been spoken at least 4,000 years ago; it has been partially reconstructed using the comparative method.

* Alagüilac ''(Guatemala)'' ''†''

* Chibchan (Central America

Central America is a subregion of North America. Its political boundaries are defined as bordering Mexico to the north, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the southwest. Central America is usually ...

& South America) (22)

* Coahuilteco ''†''

* Comecrudan (Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

& Mexico) (3) ''†''

* Cotoname ''†''

* Cuitlatec ''(Mexico: Guerrero)'' ''†''

* Epi-Olmec ''(Mexico: language of undeciphered inscriptions)'' ''†''

* Guaicurian (8) ''†''

* Huave

* Jicaquean (2)

* Lencan (2) ''†''

* Maratino ''(northeastern Mexico)'' ''†''

* Mayan (31)

* Misumalpan (5)

* Mixe–Zoquean (19)

* Naolan ''(Mexico: Tamaulipas)'' ''†''

* Oto-Manguean

The Oto-Manguean or Otomanguean () languages are a large family comprising several subfamilies of indigenous languages of the Americas. All of the Oto-Manguean languages that are now spoken are indigenous to Mexico, but the Manguean languages, Ma ...

(27)

* Pericú ''†''

* Purépecha

* Quinigua ''(northeast Mexico)'' ''†''

* Seri

* Solano ''†''

* Tequistlatecan (3)

* Totonacan (2)

* Uto-Aztecan (United States & Mexico) (33)

* Xincan (5) ''†''

* Yuman (United States & Mexico) (11)

South America and the Caribbean

Although both North and

Although both North and Central America

Central America is a subregion of North America. Its political boundaries are defined as bordering Mexico to the north, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the southwest. Central America is usually ...

are very diverse areas, South America has a linguistic diversity rivalled by only a few other places in the world with approximately 350 languages still spoken and several hundred more spoken at first contact but now extinct. The situation of language documentation and classification into genetic families is not as advanced as in North America (which is relatively well studied in many areas). Kaufman (1994: 46) gives the following appraisal:

Since the mid 1950s, the amount of published material on SA outh Americahas been gradually growing, but even so, the number of researchers is far smaller than the growing number of linguistic communities whose speech should be documented. Given the current employment opportunities, it is not likely that the number of specialists in SA Indian languages will increase fast enough to document most of the surviving SA languages before they go out of use, as most of them unavoidably will. More work languishes in personal files than is published, but this is a standard problem. It is fair to say that SA andAs a result, many relationships between languages and language families have not been determined and some of those relationships that have been proposed are on somewhat shaky ground. The list of language families, isolates, and unclassified languages below is a rather conservative one based on Campbell (1997). Many of the proposed (and often speculative) groupings of families can be seen in Campbell (1997), Gordon (2005), Kaufman (1990, 1994), Key (1979), Loukotka (1968), and in the Language stock proposals section below. * Aguano ''†'' * Aikaná ''(Brazil: Rondônia)'' * Andaquí ''†'' * Andoque ''(Colombia, Peru)'' * Andoquero ''†'' * Arauan (9) * Arawakan (South America & Caribbean) (64) * Arutani * Aymaran (3) * Baenan ''(Brazil: Bahia)'' ''†'' * Barbacoan (8) * Betoi ''(Colombia)'' ''†'' * Bororoan * Botocudoan (3) * Cahuapanan (2) * Camsá ''(Colombia)'' * Candoshi * Canichana ''(Bolivia)'' *New Guinea New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; , fossilized , also known as Papua or historically ) is the List of islands by area, world's second-largest island, with an area of . Located in Melanesia in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is ...are linguistically the poorest documented parts of the world. However, in the early 1960s fairly systematic efforts were launched inPapua New Guinea Papua New Guinea, officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea, is an island country in Oceania that comprises the eastern half of the island of New Guinea and offshore islands in Melanesia, a region of the southwestern Pacific Ocean n ..., and that areamuch smaller than SA, to be sureis in general much better documented than any part of Indigenous SA of comparable size.

Carabayo

The Carabayo (who perhaps call themselves Yacumo) are an uncontacted people of Colombia living in at least three long houses, known as '' malokas'', along the Rio Puré (now the Río Puré National Park) in the southeastern corner of the cou ...

* Cariban (29)

* Catacaoan ''†''

* Cayubaba ''(Bolivia)''

* Chapacuran (9)

* Charruan ''†''

* Chibchan (Central America & South America) (22)

* Chimuan (3) ''†''

* Chipaya–Uru

* Chiquitano

* Choco (10)

* Chon (2) ''†''

* Chono ''†''

* Coeruna ''(Brazil)'' ''†''

* Cofán ''(Colombia, Ecuador)''

* Cueva ''†''

* Culle ''(Peru)'' ''†''

* Cunza ''(Chile, Bolivia, Argentina)'' ''†''

* Esmeraldeño ''†''

* Fulnió

* Gamela ''(Brazil: Maranhão)'' ''†''

* Gorgotoqui ''(Bolivia)'' ''†''

* Guaicuruan (7)

* Guajiboan (4)

* Guamo ''(Venezuela)'' ''†''

* Guató

* Harakmbut (2)

* Hibito–Cholon ''†''

* Himarimã

* Hodï ''(Venezuela)''

* Huamoé ''(Brazil: Pernambuco)'' ''†''

* Huaorani ''(Ecuador, Peru)''

* Huarpe ''†''

* Irantxe ''(Brazil: Mato Grosso)''

* Itonama ''(Bolivia)''

* Jabutian

* Je (13)

* Jeikó ''†''

* Jirajaran (3) ''†''

* Jivaroan (2)

* Kaimbe ''†''

* Kaliana ''†''

* Kamakanan ''†''

* Kapixaná ''(Brazil: Rondônia)''

* Karajá

* Karirí ''(Brazil: Paraíba, Pernambuco, Ceará) ''†''

* Katembrí ''†''

* Katukinan (3)

* Kawésqar ''(Chile)''

* Kwaza (Koayá) ''(Brazil: Rondônia)

* Leco

* Lule ''(Argentina)''

* Máku ''†''

* Malibú ''†''

* Mapudungun ''(Chile, Argentina)''

* Mascoyan (5)

* Matacoan (4)

* Matanawí ''†''

* Maxakalían (3)

* Mocana ''(Colombia: Tubará)'' ''†''

* Mosetenan

* Movima ''(Bolivia)''

* Munichi ''(Peru)'' ''†''

* Muran (4)

* Mutú

* Nadahup (5)

* Nambiquaran (5)

* Natú ''(Brazil: Pernambuco)'' ''†''

* Nonuya ''(Peru, Colombia)''

* Ofayé

* Old Catío–Nutabe ''(Colombia)'' ''†''

* Omurano ''(Peru)'' ''†''

* Otí ''(Brazil: São Paulo)'' ''†''

* Otomakoan (2) ''†''

* Paez (also known as Nasa Yuwe)

* Palta ''†''

* Pankararú ''(Brazil: Pernambuco)'' ''†''

* Pano–Tacanan (33)

* Panzaleo ''(Ecuador)'' ''†''

* Patagon ''†'' ''(Peru)''

* Peba–Yaguan (2)

* Pijao†

* Pre-Arawakan languages of the Greater Antilles ( Guanahatabey, Macorix, Ciguayo) ''†'' ''(Cuba, Hispaniola)''

* Puelche ''(Chile)'' ''†''

* Puinave

* Puquina ''(Bolivia)'' ''†''

* Purian (2) ''†''

* Quechuan (46)

* Rikbaktsá

* Saliban (2)

* Sechura ''†''

* Tabancale ''†'' ''(Peru)''

* Tairona ''(Colombia)'' ''†''

* Tarairiú ''(Brazil: Rio Grande do Norte)'' ''†''

* Taruma ''†''

* Taushiro ''(Peru)''

* Tequiraca ''(Peru)'' ''†''

* Teushen ''†'' ''(Patagonia, Argentina)''

* Ticuna ''(Colombia, Peru, Brazil)''

* Timotean (2) ''†''

* Tiniguan (2) ''†''

* Trumai ''(Brazil: Xingu, Mato Grosso)''

* Tucanoan (15)

* Tupian (70, including Guaraní)

* Tuxá ''(Brazil: Bahia, Pernambuco)'' ''†''

* Urarina

* Vilela

* Wakona ''†''

* Warao ''(Guyana, Surinam, Venezuela)''

* Witotoan (6)

* Xokó ''(Brazil: Alagoas, Pernambuco)'' ''†''

* Xukurú ''(Brazil: Pernambuco, Paraíba)'' ''†''

* Yaghan ''(Chile)'' ''†''

* Yanomaman (4)

* Yaruro

* Yuracare ''(Bolivia)''

* Yuri ''(Colombia, Brazil)'' ''†''

* Yurumanguí ''(Colombia)'' ''†''

* Zamucoan (2)

* Zaparoan (5)

Language stock proposals

Hypothetical language-family proposals of American languages are often cited as uncontroversial in popular writing. However, many of these proposals have not been fully demonstrated, or even demonstrated at all. Some proposals are viewed by specialists in a favorable light, believing that genetic relationships are very likely to be established in the future (for example, thePenutian

Penutian is a proposed grouping of language family, language families that includes many Native Americans in the United States, Native American languages of western North America, predominantly spoken at one time in British Columbia, Washington ( ...

stock). Other proposals are more controversial with many linguists believing that some genetic relationships of a proposal may be demonstrated but much of it undemonstrated (for example, Hokan–Siouan, which, incidentally, Edward Sapir called his "wastepaper basket stock"). Still other proposals are almost unanimously rejected by specialists (for example, Amerind). Below is a (partial) list of some such proposals:

* Algonquian–Wakashan

* Almosan–Keresiouan

* Amerind

* Algonkian–Gulf

* (macro-) Arawakan

* Arutani–Sape

* Aztec–Tanoan

* Chibchan–Paezan

* Chikitano–Boróroan

* Chimu–Chipaya

* Coahuiltecan

The Coahuiltecan were various small, autonomous bands of Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Native Americans who inhabited the Rio Grande valley in what is now northeastern Mexico and southern Texas. The various Coahuiltecan groups were hunter ga ...

* Cunza–Kapixanan

* Dené–Caucasian

* Dené–Yeniseian

* Esmeralda–Yaruroan

* Ge–Pano–Carib

* Guamo–Chapacuran

* Gulf

A gulf is a large inlet from an ocean or their seas into a landmass, larger and typically (though not always) with a narrower opening than a bay (geography), bay. The term was used traditionally for large, highly indented navigable bodies of s ...

* Macro-Kulyi–Cholónan

* Hokan

* Hokan–Siouan

* Je–Tupi–Carib

* Jivaroan–Cahuapanan

* Kalianan

* Kandoshi–Omurano–Taushiro

* (Macro-)Katembri–Taruma

* Kaweskar language area

* Keresiouan

* Lule–Vilelan

* Macro-Andean

* Macro-Carib

* Macro-Chibchan

* Macro-Gê

* Macro-Jibaro

* Macro-Lekoan

* Macro-Mayan

* Macro-Otomákoan

* Macro-Paesan

* Macro-Panoan

* Macro-Puinavean

* Macro-Siouan

* Macro-Tucanoan

* Macro-Tupí–Karibe

* Macro-Waikurúan

* Macro-Warpean

* Mataco–Guaicuru

* Mosan

* Mosetén–Chonan

* Mura–Matanawian

* Sapir's Na-Dené including Haida

* Nostratic–Amerind

* Paezan

* Paezan–Barbacoan

* Penutian

Penutian is a proposed grouping of language family, language families that includes many Native Americans in the United States, Native American languages of western North America, predominantly spoken at one time in British Columbia, Washington ( ...

**California Penutian

** Oregon Penutian

**Mexican Penutian

* Puinave–Maku

* Quechumaran

* Saparo–Yawan

* Sechura–Catacao

* Takelman

* Tequiraca–Canichana

* Ticuna–Yuri (Yuri–Ticunan)

* Totozoque

* Tunican

* Yok–Utian

* Yuki–Wappo

Good discussions of past proposals can be found in Campbell (1997) and Campbell & Mithun (1979).

Amerindian linguist Lyle Campbell also assigned different percentage values of probability and confidence for various proposals of macro-families and language relationships, depending on his views of the proposals' strengths. For example, the Germanic language family

The Germanic languages are a branch of the Indo-European language family spoken natively by a population of about 515 million people mainly in Europe, North America, Oceania, and Southern Africa. The most widely spoken Germanic language, ...

would receive probability and confidence percentage values of +100% and 100%, respectively. However, if Turkish and Quechua were compared, the probability value might be −95%, while the confidence value might be 95%. 0% probability or confidence would mean complete uncertainty.

Pronouns

It has long been observed that a remarkable number of Native American languages have a pronominal pattern with first-person singular forms in ''n'' and second-person singular forms in ''m''. (Compare first-person singular ''m'' and second-person singular ''t'' across much of northern Eurasia, as in English ''me'' and ''thee'', Spanish ''me'' and ''te'', and Hungarian ''-m'' and ''-d''.) This pattern was first noted by Alfredo Trombetti in 1905. It caused Sapir to suggest that ultimately all Native American languages would turn out to be related. Johanna Nichols suggests that the pattern had spread through diffusion. This notion was rejected by Lyle Campbell, who argued that the frequency of the n/m pattern was not statistically elevated in either area compared to the rest of the world.Campbell 1997 Zamponi found that Nichols's findings were distorted by her small sample size. Looking at families rather than individual languages, he found a rate of 30% of families/protolanguages in North America, all on the western flank, compared to 5% in South America and 7% of non-American languages – though the percentage in North America, and especially the even higher number in the Pacific Northwest, drops considerably if Hokan andPenutian

Penutian is a proposed grouping of language family, language families that includes many Native Americans in the United States, Native American languages of western North America, predominantly spoken at one time in British Columbia, Washington ( ...

, or parts of them, are accepted as language families. If all the proposed Penutian and Hokan languages in the table below are related, then the frequency drops to 9% of North American families, statistically indistinguishable from the world average.

Linguistic areas

Unattested languages

Several languages are only known by mention in historical documents or from only a few names or words. It cannot be determined that these languages actually existed or that the few recorded words are actually of known or unknown languages. Some may simply be from a historian's errors. Others are of known people with no linguistic record (sometimes due to lost records). A short list is below. * Ais * Akokisa * Aranama * Ausaima * Avoyel * Bayagoula * Bidai * Cacán ( Diaguita– Calchaquí) * Calusa – Mayaimi – Tequesta * Cusabo * Eyeish * Grigra * Guale * Houma *Koroa

The Koroa were one of the groups of Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands who lived in the Mississippi Valley before French colonization. The Koroa lived in the Yazoo River basin in present-day northwest Mississippi.

Language

The Kor ...

* Mayaca (possibly related to Ais)

* Mobila

* Okelousa

* Opelousa

* Pascagoula

* Pensacola – Amacano - Chacato - Chine (Muscogean languages)

* Pijao language

* Pisabo (possibly the same language as Matsés)

* Quinipissa

* Taensa

* Tiou

* Yamacraw

* Yamasee

* Yazoo

Loukotka (1968) reports the names of hundreds of South American languages which do not have any linguistic documentation.

Pidgins and mixed languages

Various miscellaneous languages such aspidgin

A pidgin , or pidgin language, is a grammatically simplified form of contact language that develops between two or more groups of people that do not have a language in common: typically, its vocabulary and grammar are limited and often drawn f ...

s, mixed language

A mixed language, also referred to as a hybrid language or fusion language, is a type of contact language that arises among a bilingual group combining aspects of two or more languages but not clearly deriving primarily from any single language. ...

s, trade languages, and sign language

Sign languages (also known as signed languages) are languages that use the visual-manual modality to convey meaning, instead of spoken words. Sign languages are expressed through manual articulation in combination with #Non-manual elements, no ...

s are given below in alphabetical order.

# American Indian Pidgin English

# Algonquian-Basque pidgin

# Broken Oghibbeway

# Broken Slavey

# Bungee

# Callahuaya

# Carib Pidgin

# Carib Pidgin–Arawak Mixed Language

# Catalangu

# Chinook Jargon

Chinook Jargon (' or ', also known simply as ''Chinook'' or ''Jargon'') is a language originating as a pidgin language, pidgin trade language in the Pacific Northwest. It spread during the 19th century from the lower Columbia River, first to othe ...

# Delaware Jargon

# Eskimo Trade Jargon

# Greenlandic Pidgin (West Greenlandic Pidgin)

# Guajiro-Spanish

# Güegüence-Nicarao

# Haida Jargon

# Inuktitut-English Pidgin (Quebec)

# Jargonized Powhatan

# Keresan Sign Language

# Labrador Eskimo Pidgin

# Lingua Franca Apalachee

# Lingua Franca Creek

# Lingua Geral Amazônica

# Lingua Geral do Sul

# Loucheux Jargon

# Media Lengua

# Mednyj Aleut

# Michif

# Mobilian Jargon

# Montagnais Pidgin Basque

# Nootka Jargon

# Ocaneechi

# Pidgin Massachusett

# Plains Indian Sign Language

Writing systems

While most Indigenous languages have adopted the Latin script as the written form of their languages, a few languages have their own unique writing systems after encountering the Latin script (often through missionaries) that are still in use. All pre-Columbian Indigenous writing systems are no longer used.See also

* Amerind languages * Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America * Classification of indigenous peoples of the Americas * Classification of indigenous languages of the Americas * Haplogroup Q-M242 (Y-DNA) *Indigenous peoples of the Americas

In the Americas, Indigenous peoples comprise the two continents' pre-Columbian inhabitants, as well as the ethnic groups that identify with them in the 15th century, as well as the ethnic groups that identify with the pre-Columbian population of ...

* Language families and languages

* Languages of Peru

* List of endangered languages in Canada

* List of endangered languages in Mexico

* List of endangered languages in the United States

* List of endangered languages with mobile apps

* List of indigenous languages of South America

* List of indigenous languages in Argentina

* Mesoamerican languages

* Native American Languages Act of 1990

References

Bibliography

*. * * *North America

* * * * * * * Goddard, Ives. (1999). ''Native languages and language families of North America'' (rev. and enlarged ed. with additions and corrections). ap Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press (Smithsonian Institution). (Updated version of the map in Goddard 1996). . * * * * Nater, Hank F. (1984). The Bella Coola Language. Mercury Series; Canadian Ethnology Service (No. 92). Ottawa: National Museums of Canada. * Powell, John W. (1891). Indian linguistic families of America north of Mexico. Seventh annual report, Bureau of American Ethnology (pp. 1–142). Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. (Reprinted in P. Holder (Ed.), 1966, ''Introduction to Handbook of American Indian languages by Franz Boas and Indian linguistic families of America, north of Mexico, by J. W. Powell'', Lincoln: University of Nebraska). * Powell, John W. (1915). ''Linguistic families of American Indians north of Mexico by J. W. Powell, revised by members of the staff of the Bureau of American Ethnology''. (Map). Bureau of American Ethnology miscellaneous publication (No. 11). Baltimore: Hoen. * Sebeok, Thomas A. (Ed.). (1973). ''Linguistics in North America'' (parts 1 & 2). Current trends in linguistics (Vol. 10). The Hauge: Mouton. (Reprinted as Sebeok 1976). * Sebeok, Thomas A. (Ed.). (1976). ''Native languages of the Americas''. New York: Plenum. * Sherzer, Joel. (1973). Areal linguistics in North America. In T. A. Sebeok (Ed.), ''Linguistics in North America'' (part 2, pp. 749–795). Current trends in linguistics (Vol. 10). The Hauge: Mouton. (Reprinted in Sebeok 1976). * Sherzer, Joel. (1976). ''An areal-typological study of American Indian languages north of Mexico''. Amsterdam: North-Holland. * Sletcher, Michael, 'North American Indians', in Will Kaufman and Heidi Macpherson, eds., ''Britain and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History'', (2 vols., Oxford, 2005). * Sturtevant, William C. (Ed.). (1978–present). ''Handbook of North American Indians'' (Vol. 1–20). Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution. (Vols. 1–3, 16, 18–20 not yet published). * Vaas, Rüdiger: 'Die Sprachen der Ureinwohner'. In: Stoll, Günter, Vaas, Rüdiger: ''Spurensuche im Indianerland.'' Hirzel. Stuttgart 2001, chapter 7. * Voegelin, Carl F.; & Voegelin, Florence M. (1965). Classification of American Indian languages. ''Languages of the world'', Native American fasc. 2, sec. 1.6). ''Anthropological Linguistics'', ''7'' (7): 121–150. *South America

* Adelaar, Willem F. H.; & Muysken, Pieter C. (2004). ''The languages of the Andes''. Cambridge language surveys. Cambridge University Press. * Fabre, Alain. (1998). "Manual de las lenguas indígenas sudamericanas, I-II". München: Lincom Europa. * Kaufman, Terrence. (1990). Language history in South America: What we know and how to know more. In D. L. Payne (Ed.), ''Amazonian linguistics: Studies in lowland South American languages'' (pp. 13–67). Austin: University of Texas Press. . * Kaufman, Terrence. (1994). The native languages of South America. In C. Mosley & R. E. Asher (Eds.), ''Atlas of the world's languages'' (pp. 46–76). London: Routledge. * Key, Mary R. (1979). ''The grouping of South American languages''. Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag. * Loukotka, Čestmír. (1968). ''Classification of South American Indian languages''. Los Angeles: Latin American Studies Center, University of California. * Mason, J. Alden. (1950). The languages of South America. In J. Steward (Ed.), ''Handbook of South American Indians'' (Vol. 6, pp. 157–317). Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology bulletin (No. 143). Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. * Migliazza, Ernest C.; & Campbell, Lyle. (1988). ''Panorama general de las lenguas indígenas en América''. Historia general de América (Vol. 10). Caracas: Instituto Panamericano de Geografía e Historia. * Rodrigues, Aryon. (1986). ''Linguas brasileiras: Para o conhecimento das linguas indígenas''. São Paulo: Edições Loyola. * Rowe, John H. (1954). Linguistics classification problems in South America. In M. B. Emeneau (Ed.), ''Papers from the symposium on American Indian linguistics'' (pp. 10–26). University of California publications in linguistics (Vol. 10). Berkeley: University of California Press. * Sapir, Edward. (1929). Central and North American languages. In ''The encyclopædia britannica: A new survey of universal knowledge'' (14 ed.) (Vol. 5, pp. 138–141). London: The Encyclopædia Britannica Company, Ltd. * Voegelin, Carl F.; & Voegelin, Florence M. (1977). ''Classification and index of the world's languages''. Amsterdam: Elsevier. .Debian North American Indigenous Languages Project

External links

Catálogo de línguas indígenas sul-americanas

Diccionario etnolingüístico y guía bibliográfica de los pueblos indígenas sudamericanos

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20180929134719/http://www.athenapub.com/salang1.htm South American Languages

Indigenous Peoples Languages: Articles, News, Videos

Documentation Center of the Linguistic Minorities of Panama

The Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America

Indigenous Language Institute

The Society for the Study of the Indigenous Languages of the Americas

(SSILA)

(collection of ethnographic, linguistic, & historical material)

* ttp://www.albany.edu/anthro/maldp/ Project for the Documentation of the Languages of Mesoamerica

Programa de Formación en Educación Intercultural Bilingüe para los Países Andinos

(University of California at Davis)

Native Languages of the Americas

(Saskatchewan Indian Cultural Centre)

Alaska Native Language Center

{{DEFAULTSORT:Indigenous Languages Of The Americas Languages