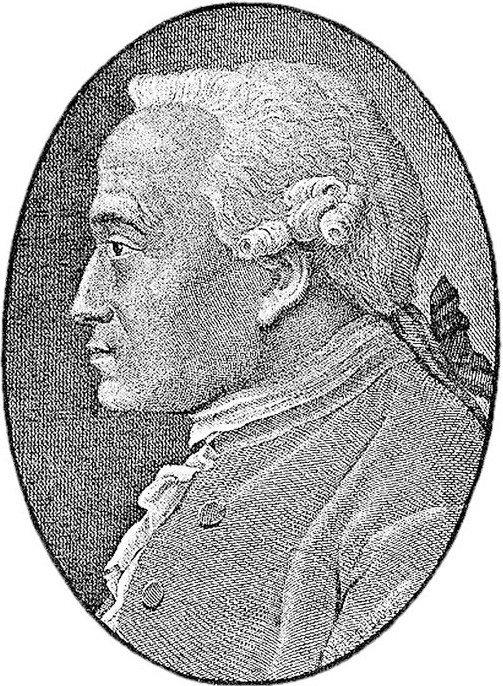

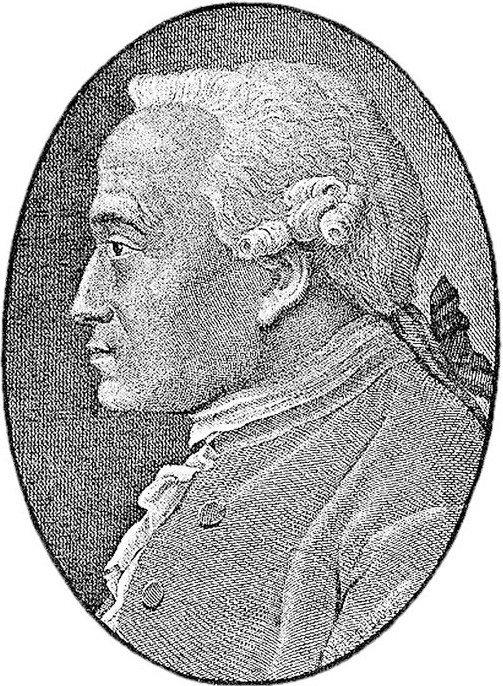

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German

philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

and one of the central

Enlightenment thinkers. Born in

Königsberg

Königsberg (; ; ; ; ; ; , ) is the historic Germany, German and Prussian name of the city now called Kaliningrad, Russia. The city was founded in 1255 on the site of the small Old Prussians, Old Prussian settlement ''Twangste'' by the Teuton ...

, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in

epistemology

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Also called "the theory of knowledge", it explores different types of knowledge, such as propositional knowledge about facts, practical knowle ...

,

metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of ...

,

ethics

Ethics is the philosophy, philosophical study of Morality, moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates Normativity, normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches inclu ...

, and

aesthetics

Aesthetics (also spelled esthetics) is the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature of beauty and taste (sociology), taste, which in a broad sense incorporates the philosophy of art.Slater, B. H.Aesthetics ''Internet Encyclopedia of Ph ...

have made him one of the most influential and highly discussed figures in modern

Western philosophy

Western philosophy refers to the Philosophy, philosophical thought, traditions and works of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the Pre ...

.

In his doctrine of

transcendental idealism

Transcendental idealism is a philosophical system founded by German philosopher Immanuel Kant in the 18th century. Kant's epistemological program is found throughout his '' Critique of Pure Reason'' (1781). By ''transcendental'' (a term that des ...

, Kant argued that

space

Space is a three-dimensional continuum containing positions and directions. In classical physics, physical space is often conceived in three linear dimensions. Modern physicists usually consider it, with time, to be part of a boundless ...

and

time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

are mere "forms of intuition" that structure all

experience

Experience refers to Consciousness, conscious events in general, more specifically to perceptions, or to the practical knowledge and familiarity that is produced by these processes. Understood as a conscious event in the widest sense, experience i ...

and that the objects of experience are mere "appearances". The nature of things as they are in themselves is unknowable to us. Nonetheless, in an attempt to counter the philosophical doctrine of

skepticism, he wrote the ''

Critique of Pure Reason

The ''Critique of Pure Reason'' (; 1781; second edition 1787) is a book by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, in which the author seeks to determine the limits and scope of metaphysics. Also referred to as Kant's "First Critique", it was foll ...

'' (1781/1787), his best-known work. Kant drew a parallel to the

Copernican Revolution in his proposal to think of the objects of experience as conforming to our spatial and temporal forms of

intuition

Intuition is the ability to acquire knowledge without recourse to conscious reasoning or needing an explanation. Different fields use the word "intuition" in very different ways, including but not limited to: direct access to unconscious knowledg ...

and the

categories of our understanding so that we have ''

a priori

('from the earlier') and ('from the later') are Latin phrases used in philosophy to distinguish types of knowledge, Justification (epistemology), justification, or argument by their reliance on experience. knowledge is independent from any ...

'' cognition of those objects.

Kant believed that

reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing valid conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, religion, scien ...

is the source of

morality

Morality () is the categorization of intentions, Decision-making, decisions and Social actions, actions into those that are ''proper'', or ''right'', and those that are ''improper'', or ''wrong''. Morality can be a body of standards or principle ...

and that aesthetics arises from a faculty of disinterested judgment. Kant's religious views were deeply connected to his moral theory. Their exact nature remains in dispute. He hoped that perpetual peace could be secured through an international federation of

republican states and

international cooperation

In international relations, multilateralism refers to an alliance of multiple countries pursuing a common goal. Multilateralism is based on the principles of inclusivity, equality, and cooperation, and aims to foster a more peaceful, prosperous, an ...

. His

cosmopolitan reputation is called into question by his promulgation of

scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that the Human, human species is divided into biologically distinct taxa called "race (human categorization), races", and that empirical evi ...

for much of his career, although he altered his views on the subject in the last decade of his life.

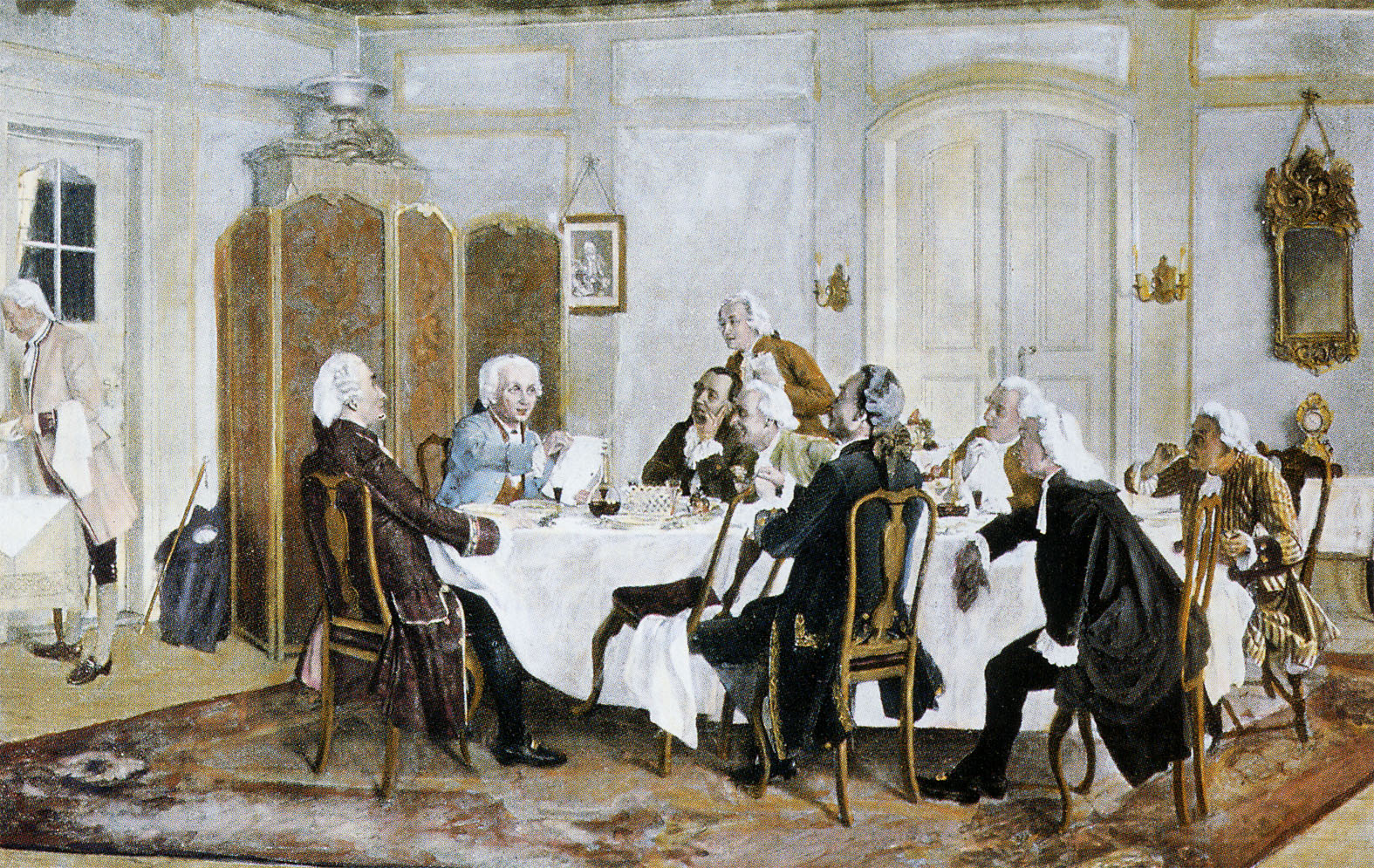

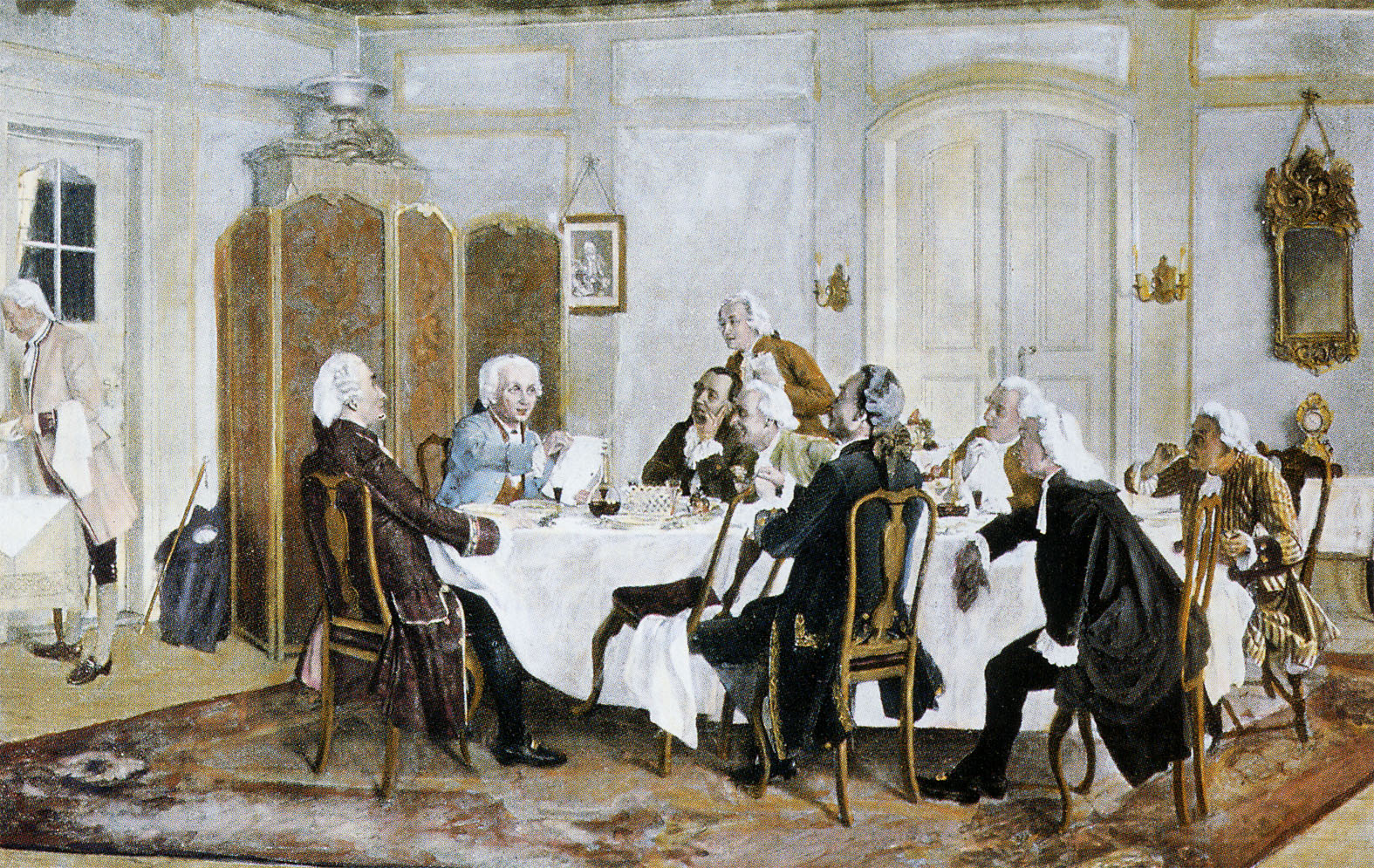

Early life

Immanuel Kant was born on 22 April 1724 into a

Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

n German family of

Lutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

faith in

Königsberg

Königsberg (; ; ; ; ; ; , ) is the historic Germany, German and Prussian name of the city now called Kaliningrad, Russia. The city was founded in 1255 on the site of the small Old Prussians, Old Prussian settlement ''Twangste'' by the Teuton ...

, East Prussia. His mother, Anna Regina Reuter, was born in Königsberg to a father from

Nuremberg

Nuremberg (, ; ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the Franconia#Towns and cities, largest city in Franconia, the List of cities in Bavaria by population, second-largest city in the States of Germany, German state of Bav ...

. Her surname is sometimes erroneously given as Porter. Kant's father, Johann Georg Kant, was a German harness-maker from

Memel, at the time Prussia's most northeastern city (now

Klaipėda

Klaipėda ( ; ) is a city in Lithuania on the Baltic Sea coast. It is the List of cities in Lithuania, third-largest city in Lithuania, the List of cities in the Baltic states by population, fifth-largest city in the Baltic States, and the capi ...

, Lithuania). It is possible that the Kants got their name from the village of Kantvainiai (German: ''Kantwaggen'' – today part of

Priekulė) and were of

Kursenieki origin.

Kant was baptized as Emanuel and later changed the spelling of his name to Immanuel after learning

Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

. He was the fourth of nine children (six of whom reached adulthood). The Kant household stressed the

pietist

Pietism (), also known as Pietistic Lutheranism, is a movement within Lutheranism that combines its emphasis on biblical doctrine with an emphasis on individual piety and living a holy Christianity, Christian life.

Although the movement is ali ...

values of religious devotion, humility, and a literal interpretation of the

Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

. The young Immanuel's education was strict, punitive, and disciplinary and focused on Latin and religious instruction over mathematics and science. In his later years, Kant lived a strictly ordered life. It was said that neighbors would set their clocks by his daily walks. Kant considered marriage two times, first a widow and then a Westphalian girl, but both times waited too long. Though he never married, he seems to have had a rewarding social life; he was a popular teacher as well as a modestly successful author, even before starting on his major philosophical works.

Young scholar

Kant showed a great aptitude for study at an early age. He first attended the

Collegium Fridericianum, from which he graduated at the end of the summer of 1740. In 1740, aged 16, he enrolled at the

University of Königsberg, where he would later remain for the rest of his professional life. He studied the philosophy of

Gottfried Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (or Leibnitz; – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat who is credited, alongside Isaac Newton, Sir Isaac Newton, with the creation of calculus in ad ...

and

Christian Wolff under

Martin Knutzen (Associate Professor of Logic and Metaphysics from 1734 until he died in 1751), a

rationalist who was also familiar with developments in British philosophy and science and introduced Kant to the new mathematical physics of

Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

. Knutzen dissuaded Kant from the theory of

pre-established harmony, which he regarded as "the pillow for the lazy mind". He also dissuaded Kant from

idealism

Idealism in philosophy, also known as philosophical realism or metaphysical idealism, is the set of metaphysics, metaphysical perspectives asserting that, most fundamentally, reality is equivalent to mind, Spirit (vital essence), spirit, or ...

, the idea that reality is purely mental, which most philosophers in the 18th century regarded negatively. The theory of

transcendental idealism

Transcendental idealism is a philosophical system founded by German philosopher Immanuel Kant in the 18th century. Kant's epistemological program is found throughout his '' Critique of Pure Reason'' (1781). By ''transcendental'' (a term that des ...

that Kant later included in the ''

Critique of Pure Reason

The ''Critique of Pure Reason'' (; 1781; second edition 1787) is a book by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, in which the author seeks to determine the limits and scope of metaphysics. Also referred to as Kant's "First Critique", it was foll ...

'' was developed partially in opposition to traditional idealism. Kant had contacts with students, colleagues, friends and diners who frequented the local

Masonic lodge

A Masonic lodge (also called Freemasons' lodge, or private lodge or constituent lodge) is the basic organisational unit of Freemasonry.

It is also a commonly used term for a building where Freemasons meet and hold their meetings. Every new l ...

.

His father's stroke and subsequent death in 1746 interrupted his studies. Kant left Königsberg shortly after August 1748; he would return there in August 1754. He became a private tutor in the towns surrounding Königsberg, but continued his scholarly research. In 1749, he published his first philosophical work, ''

Thoughts on the True Estimation of Living Forces

''Thoughts on the True Estimation of Living Forces'' () is Immanuel Kant's first published work, published in 1749. It is the first of Kant's works on natural philosophy.

The ''True Estimation'' is divided into a preface and three chapters. Chap ...

'' (written in 1745–1747).

Early work

Kant is best known for his work in the philosophy of ethics and metaphysics, but he made significant contributions to other disciplines. In 1754, while contemplating on a prize question by the

Berlin Academy about the problem of Earth's rotation, he argued that the Moon's gravity would slow down Earth's spin and he also put forth the argument that gravity would eventually cause the Moon's

tidal locking

Tidal locking between a pair of co-orbiting astronomical body, astronomical bodies occurs when one of the objects reaches a state where there is no longer any net change in its rotation rate over the course of a complete orbit. In the case where ...

to

coincide with the Earth's rotation.

The next year, he expanded this reasoning to the

formation and evolution of the Solar System in his ''

Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens''.

In 1755, Kant received a license to lecture in the University of Königsberg and began lecturing on a variety of topics including mathematics, physics, logic, and metaphysics. In his 1756 essay on the theory of winds, Kant laid out an original insight into the

Coriolis force.

In 1756, Kant also published three papers on the

1755 Lisbon earthquake

The 1755 Lisbon earthquake, also known as the Great Lisbon earthquake, impacted Portugal, the Iberian Peninsula, and Northwest Africa on the morning of Saturday, 1 November, All Saints' Day, Feast of All Saints, at around 09:40 local time. In ...

. Kant's theory, which involved shifts in huge caverns filled with hot gases, though inaccurate, was one of the first systematic attempts to explain earthquakes in natural rather than supernatural terms. In 1757, Kant began lecturing on geography making him one of the first lecturers to explicitly teach geography as its own subject.

Geography was one of Kant's most popular lecturing topics and, in 1802, a compilation by Friedrich Theodor Rink of Kant's lecturing notes, ''Physical Geography'', was released. After Kant became a professor in 1770, he expanded the topics of his lectures to include lectures on natural law, ethics, and anthropology, along with other topics.

In the ''Universal Natural History'', Kant laid out the

nebular hypothesis, in which he deduced that the

Solar System

The Solar SystemCapitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Sola ...

had formed from a large cloud of gas, a

nebula

A nebula (; or nebulas) is a distinct luminescent part of interstellar medium, which can consist of ionized, neutral, or molecular hydrogen and also cosmic dust. Nebulae are often star-forming regions, such as in the Pillars of Creation in ...

. Kant also correctly deduced that the

Milky Way

The Milky Way or Milky Way Galaxy is the galaxy that includes the Solar System, with the name describing the #Appearance, galaxy's appearance from Earth: a hazy band of light seen in the night sky formed from stars in other arms of the galax ...

was a

large disk of stars, which he theorized formed from a much larger spinning gas cloud. He further suggested that other distant "nebulae" might be other galaxies. These postulations opened new horizons for astronomy, for the first time extending it beyond the solar system to galactic and intergalactic realms.

From then on, Kant turned increasingly to philosophical issues, although he continued to write on the sciences throughout his life. In the early 1760s, Kant produced a series of important works in philosophy. ''

The False Subtlety of the Four Syllogistic Figures'', a work in logic, was published in 1762. Two more works appeared the following year: ''Attempt to Introduce the Concept of Negative Magnitudes into Philosophy'' and ''

The Only Possible Argument in Support of a Demonstration of the Existence of God''. By 1764, Kant had become a notable popular author, and wrote ''

Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime''; he was second to

Moses Mendelssohn in a Berlin Academy prize competition with his ''Inquiry Concerning the Distinctness of the Principles of Natural Theology and Morality'' (often referred to as "The Prize Essay"). In 1766 Kant wrote a critical piece on

Emanuel Swedenborg

Emanuel Swedenborg (; ; born Emanuel Swedberg; (29 January 168829 March 1772) was a Swedish polymath; scientist, engineer, astronomer, anatomist, Christian theologian, philosopher, and mysticism, mystic. He became best known for his book on the ...

's ''Dreams of a Spirit-Seer''.

In 1770, Kant was appointed Full Professor of Logic and Metaphysics at the University of Königsberg. In defense of this appointment, Kant wrote his

inaugural dissertation ''On the Form and Principles of the Sensible and the Intelligible World''. This work saw the emergence of several central themes of his mature work, including the distinction between the faculties of intellectual thought and sensible receptivity. To miss this distinction would mean to commit the error of

subreption Subreption (, "the act of stealing", from ''surripere'', "to take away secretly"; ) is a legal concept in Roman law, in the canon law of the Catholic Church, and in Scots law, as well as a philosophical concept.

Roman law

The term "subreption" o ...

, and, as he says in the last chapter of the dissertation, only in avoiding this error does metaphysics flourish.

While it is true that Kant wrote his greatest works relatively late in life, there is a tendency to underestimate the value of his earlier works. Recent Kant scholarship has devoted more attention to these "pre-critical" writings and has recognized a degree of continuity with his mature work.

Publication of the ''Critique of Pure Reason''

At age 46, Kant was an established scholar and an increasingly influential philosopher, and much was expected of him. In correspondence with his ex-student and friend

Markus Herz

Markus Herz (; Berlin, 17 January 1747 – Berlin, 19 January 1803) was a German Jewish physician and lecturer on philosophy.

Biography

Born in Berlin to very poor parents, Herz was destined for a mercantile career, and in 1762 went to Köni ...

, Kant admitted that, in the inaugural dissertation, he had failed to account for the relation between our sensible and intellectual faculties. He needed to explain how we combine what is known as sensory knowledge with the other type of knowledgethat is, reasoned knowledgethese two being related but having very different processes. Kant also credited

David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist who was best known for his highly influential system of empiricism, philosophical scepticism and metaphysical naturalism. Beg ...

with awakening him from a "" in which he had unquestioningly accepted the tenets of both religion and

natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

.

Hume, in his 1739 ''

Treatise on Human Nature'', had argued that we know the mind only through a subjective, essentially illusory series of perceptions. Ideas such as

causality,

morality

Morality () is the categorization of intentions, Decision-making, decisions and Social actions, actions into those that are ''proper'', or ''right'', and those that are ''improper'', or ''wrong''. Morality can be a body of standards or principle ...

, and

objects are not evident in experience, so their reality may be questioned. Kant felt that reason could remove this skepticism, and he set himself to solving these problems. Although fond of company and conversation with others, Kant isolated himself, and resisted friends' attempts to bring him out of his isolation. When Kant emerged from his silence in 1781, the result was the ''Critique of Pure Reason'', printed by

Johann Friedrich Hartknoch. Kant countered Hume's

empiricism

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological view which holds that true knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience and empirical evidence. It is one of several competing views within epistemology, along ...

by claiming that some knowledge exists inherently in the mind, independent of experience.

He drew a parallel to the

Copernican revolution in his proposal that worldly objects can be intuited ''

a priori

('from the earlier') and ('from the later') are Latin phrases used in philosophy to distinguish types of knowledge, Justification (epistemology), justification, or argument by their reliance on experience. knowledge is independent from any ...

'', and that

intuition

Intuition is the ability to acquire knowledge without recourse to conscious reasoning or needing an explanation. Different fields use the word "intuition" in very different ways, including but not limited to: direct access to unconscious knowledg ...

is consequently distinct from

objective reality

The distinction between subjectivity and objectivity is a basic idea of philosophy, particularly epistemology and metaphysics. Various understandings of this distinction have evolved through the work of countless philosophers over centuries. One b ...

. Perhaps the most direct contested matter was Hume's argument against any necessary connection between causal events, which Hume characterized as the "cement of the universe". In the ''Critique of Pure Reason'', Kant argues for what he takes to be the ''a priori'' justification of such necessary connection.

Although now recognized as one of the greatest works in the history of philosophy, the ''Critique'' disappointed Kant's readers upon its initial publication. The book was long, over 800 pages in the original German edition, and written in a convoluted style. Kant was quite upset with its reception. His former student,

Johann Gottfried Herder criticized it for placing reason as an entity worthy of criticism by itself instead of considering the process of reasoning within the context of language and one's entire personality. Similarly to

Christian Garve and

Johann Georg Heinrich Feder, he rejected Kant's position that space and time possess a form that can be analyzed. Garve and Feder also faulted the ''Critique'' for not explaining differences in perception of sensations. Its density made it, as Herder said in a letter to

Johann Georg Hamann, a "tough nut to crack", obscured by "all this heavy gossamer". Its reception stood in stark contrast to the praise Kant had received for earlier works, such as his ''Prize Essay'' and shorter works that preceded the first ''Critique''. Recognizing the need to clarify the original treatise, Kant wrote the ''

Prolegomena to any Future Metaphysics'' in 1783 as a summary of its main views. Shortly thereafter, Kant's friend Johann Friedrich Schultz (1739–1805), a professor of mathematics, published ''Explanations of Professor Kant's Critique of Pure Reason'' (Königsberg, 1784), which was a brief but very accurate commentary on Kant's ''Critique of Pure Reason''.

Kant's reputation gradually rose through the latter portion of the 1780s, sparked by a series of important works: the 1784 essay, "

Answer to the Question: What is Enlightenment?"; 1785's ''

Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals'' (his first work on moral philosophy); and ''

Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science'' from 1786. Kant's fame ultimately arrived from an unexpected source. In 1786,

Karl Leonhard Reinhold published a series of public letters on Kantian philosophy. In these letters, Reinhold framed Kant's philosophy as a response to the central intellectual controversy of the era: the

pantheism controversy.

Friedrich Jacobi had accused the recently deceased

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (; ; 22 January 1729 – 15 February 1781) was a German philosopher, dramatist, publicist and art critic, and a representative of the Enlightenment era. His plays and theoretical writings substantially influenced the dev ...

(a distinguished dramatist and philosophical essayist) of

Spinozism. Such a charge, tantamount to an accusation of atheism, was vigorously denied by Lessing's friend

Moses Mendelssohn, leading to a bitter public dispute among partisans. The controversy gradually escalated into a debate about the values of the Enlightenment and the value of reason. Reinhold maintained in his letters that Kant's ''Critique of Pure Reason'' could settle this dispute by defending the authority and bounds of reason. Reinhold's

letters were widely read and made Kant the most famous philosopher of his era.

Later work

Kant published a second edition of the ''Critique of Pure Reason'' in 1787, heavily revising the first parts of the book. Most of his subsequent work focused on other areas of philosophy. He continued to develop his moral philosophy, notably in 1788's ''

Critique of Practical Reason'' (known as the second ''Critique''), and 1797's ''

Metaphysics of Morals''. The 1790 ''

Critique of the Power of Judgment'' (the third ''Critique'') applied the Kantian system to aesthetics and

teleology

Teleology (from , and )Partridge, Eric. 1977''Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English'' London: Routledge, p. 4187. or finalityDubray, Charles. 2020 912Teleology. In ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' 14. New York: Robert Appleton ...

. In 1792, Kant's attempt to publish the Second of the four Pieces of ''

Religion within the Bounds of Bare Reason'',

[Werner S. Pluhar, ]

Religion within the Bounds of Bare Reason

''. 2009

Description

Contents.

With a

Introduction

by Stephen Palmquist. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, in the journal ''Berlinische Monatsschrift'', met with opposition from

the King's

censorship

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governmen ...

commission, which had been established that same year in the context of the

French Revolution. Kant then arranged to have all four pieces published as a book, routing it through the philosophy department at the University of Jena to avoid the need for theological censorship. This insubordination earned him a now-famous reprimand from the King. When he nevertheless published a second edition in 1794, the censor was so irate that he arranged for a royal order that required Kant never to publish or even speak publicly about religion. Kant then published his response to the King's reprimand and explained himself in the preface of ''The Conflict of the Faculties'' (1798).

He also wrote a number of semi-popular essays on history, religion, politics, and other topics. These works were well received by Kant's contemporaries and confirmed his preeminent status in eighteenth-century philosophy. There were several journals devoted solely to defending and criticizing Kantian philosophy. Despite his success, philosophical trends were moving in another direction. Many of Kant's most important disciples and followers (including

Reinhold

Reinhold is a German language, German, male given name, originally composed of two elements. The first is from ''regin'', meaning "the (German)Gods" or as an emphatic prefix (very) and ''wald'' meaning "powerful". The second element having been re ...

,

Beck

Beck David Hansen (born Bek David Campbell; July 8, 1970), known mononymously as Beck, is an American musician, singer, songwriter, and record producer. He rose to fame in the early 1990s with his Experimental music, experimental and Lo-fi mus ...

, and

Fichte) transformed the Kantian position. The progressive stages of revision of Kant's teachings marked the emergence of

German idealism

German idealism is a philosophical movement that emerged in Germany in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It developed out of the work of Immanuel Kant in the 1780s and 1790s, and was closely linked both with Romanticism and the revolutionary ...

. In what was one of his final acts expounding a stance on philosophical questions, Kant opposed these developments and publicly denounced Fichte in an open letter in 1799.

In 1800, a student of Kant named Gottlob Benjamin Jäsche (1762–1842) published a manual of logic for teachers called ''Logik'', which he had prepared at Kant's request. Jäsche prepared the ''Logik'' using a copy of a textbook in logic by

Georg Friedrich Meier entitled ''Excerpt from the Doctrine of Reason'', in which Kant had written copious notes and annotations. The ''Logik'' has been considered of fundamental importance to Kant's philosophy, and the understanding of it. The great 19th-century logician

Charles Sanders Peirce

Charles Sanders Peirce ( ; September 10, 1839 – April 19, 1914) was an American scientist, mathematician, logician, and philosopher who is sometimes known as "the father of pragmatism". According to philosopher Paul Weiss (philosopher), Paul ...

remarked, in an incomplete review of

Thomas Kingsmill Abbott's English translation of the introduction to ''Logik'', that "Kant's whole philosophy turns upon his logic." Also,

Robert Schirokauer Hartman and Wolfgang Schwarz wrote in the translators' introduction to their English translation of the ''Logik'', "Its importance lies not only in its significance for the ''Critique of Pure Reason'', the second part of which is a restatement of fundamental tenets of the ''Logic'', but in its position within the whole of Kant's work."

Death and burial

Kant's health, long poor, worsened. He died at Königsberg on 12 February 1804, uttering ''Es ist gut'' ("It is good") before his death. His unfinished final work was published as ''

Opus Postumum''. Kant always cut a curious figure in his lifetime for his modest, rigorously scheduled habits, which have been referred to as clocklike.

Heinrich Heine

Christian Johann Heinrich Heine (; ; born Harry Heine; 13 December 1797 – 17 February 1856) was an outstanding poet, writer, and literary criticism, literary critic of 19th-century German Romanticism. He is best known outside Germany for his ...

observed the magnitude of "his destructive, world-crushing thoughts" and considered him a sort of philosophical "executioner", comparing him to

Robespierre with the observation that both men "represented in the highest the type of provincial bourgeois. Nature had destined them to weigh coffee and sugar, but Fate determined that they should weigh other things and placed on the scales of the one a king, on the scales of the other a god."

When his body was transferred to a new burial spot, his skull was measured during the exhumation and found to be larger than the average German male's with a "high and broad" forehead. His forehead has been an object of interest ever since it became well known through his portraits: "In Döbler's portrait and in Kiefer's faithful if expressionistic reproduction of it—as well as in many of the other late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century portraits of Kant—the forehead is remarkably large and decidedly retreating."

Kant's

mausoleum

A mausoleum is an external free-standing building constructed as a monument enclosing the burial chamber of a deceased person or people. A mausoleum without the person's remains is called a cenotaph. A mausoleum may be considered a type o ...

adjoins the northeast corner of

Königsberg Cathedral in

Kaliningrad, Russia. The mausoleum was constructed by the architect

Friedrich Lahrs and was finished in 1924, in time for the bicentenary of Kant's birth. Originally, Kant was buried inside the cathedral, but in 1880 his remains were moved to a

neo-Gothic chapel adjoining the northeast corner of the cathedral. Over the years, the chapel became dilapidated and was demolished to make way for the mausoleum, which was built on the same location. The tomb and its mausoleum are among the few artifacts of German times preserved by the

Soviets after they captured the city.

Into the 21st century, many newlyweds bring flowers to the mausoleum. Artifacts previously owned by Kant, known as ''Kantiana'', were included in the

Königsberg City Museum; however, the museum was destroyed during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. A replica of the statue of Kant that in German times stood in front of the main

University of Königsberg building was donated by a German entity in the early 1990s and placed in the same grounds. After

the expulsion of

Königsberg

Königsberg (; ; ; ; ; ; , ) is the historic Germany, German and Prussian name of the city now called Kaliningrad, Russia. The city was founded in 1255 on the site of the small Old Prussians, Old Prussian settlement ''Twangste'' by the Teuton ...

's German population at the end of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the University of Königsberg where Kant taught was replaced by the Russian-language Kaliningrad State University, which appropriated the campus and surviving buildings. In 2005, the university was renamed Immanuel Kant State University of Russia. The name change, which was considered a politically-charged issue due to the residents having mixed feelings about its German past, was announced at a ceremony attended by Russian president

Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer who has served as President of Russia since 2012, having previously served from 2000 to 2008. Putin also served as Prime Minister of Ru ...

and German chancellor

Gerhard Schröder

Gerhard Fritz Kurt Schröder (; born 7 April 1944) is a German former politician and Lobbying, lobbyist who served as Chancellor of Germany from 1998 to 2005. From 1999 to 2004, he was also the Leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (S ...

, and the university formed a Kant Society, dedicated to the study of

Kantianism. In 2010, the university was again renamed to

Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal University.

Philosophy

Like many of his contemporaries, Kant was greatly impressed with the scientific advances made by

Newton and others. This new evidence of the power of human reason called into question for many the traditional authority of politics and religion. In particular, the modern mechanistic view of the world called into question the very possibility of morality; for, if there is no agency, there cannot be any responsibility.

The aim of Kant's critical project is to secure human autonomy, the basis of religion and morality, from this threat of mechanism—and to do so in a way that preserves the advances of modern science. In the ''Critique of Pure Reason'', Kant summarizes his philosophical concerns in the following three questions:

# What can I know?

# What should I do?

# What may I hope?

The ''

Critique of Pure Reason

The ''Critique of Pure Reason'' (; 1781; second edition 1787) is a book by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, in which the author seeks to determine the limits and scope of metaphysics. Also referred to as Kant's "First Critique", it was foll ...

'' focuses upon the first question and opens a conceptual space for an answer to the second question. It argues that even though we cannot strictly ''know'' that we are free, we can—and for practical purposes, must—''think'' of ourselves as free. In Kant's own words, "I had to deny knowledge in order to make room for faith." Our rational faith in morality is further developed in the ''

Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals'' and the ''

Critique of Practical Reason''.

The ''

Critique of the Power of Judgment'' argues we may ''rationally'' hope for the harmonious unity of the theoretical and practical domains treated in the first two ''Critiques'' on the basis, not only of its conceptual possibility, but also on the basis of our affective experience of natural beauty and, more generally, the organization of the natural world. In ''

Religion within the Bounds of Mere Reason'', Kant endeavors to complete his answer to this third question.

These works all place the active, rational human

subject at the center of the cognitive and moral worlds. In brief, Kant argues that the

mind

The mind is that which thinks, feels, perceives, imagines, remembers, and wills. It covers the totality of mental phenomena, including both conscious processes, through which an individual is aware of external and internal circumstances ...

itself necessarily makes a constitutive contribution to

knowledge

Knowledge is an Declarative knowledge, awareness of facts, a Knowledge by acquaintance, familiarity with individuals and situations, or a Procedural knowledge, practical skill. Knowledge of facts, also called propositional knowledge, is oft ...

, that this contribution is transcendental rather than psychological, and that to act autonomously is to act according to rational moral principles.

Kant's critical project

Kant's 1781 (revised 1787) ''Critique of Pure Reason'' has often been cited as the most significant volume of metaphysics and

epistemology

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Also called "the theory of knowledge", it explores different types of knowledge, such as propositional knowledge about facts, practical knowle ...

in modern philosophy. In the first ''Critique'', and later on in other works as well, Kant frames the "general" and "real problem of pure reason" in terms of the following question: "How are synthetic judgments ''a priori'' possible?" To understand this claim, it is necessary to define some terms. First, Kant makes a distinction between two sources of knowledge:

# Cognitions ''a priori'': "cognition independent of all experience and even of all the impressions of the senses".

# Cognitions ''a posteriori'': cognitions that have their sources in experiencethat is, which are empirical.

Second, he makes a distinction in terms of the ''form'' of knowledge:

# Analytic judgements: judgements in which the predicate concept is contained in the subject concept; e.g., "All bachelors are unmarried", or "All bodies take up space". These can also be called "judgments of clarification".

# Synthetic judgements: judgements in which the predicate concept is not contained in the subject concept; e.g., "All bachelors are alone", "All swans are white", or "All bodies have weight". These can also be called "judgments of amplification".

An analytic judgement is true by nature of strictly conceptual relations. All analytic judgements are ''a priori'' since basing an analytic judgement on experience would be absurd. By contrast, a synthetic judgement is one the content of which includes something new in the sense that it is includes something not already contained in the subject concept. The truth or falsehood of a synthetic statement depends upon something more than what is contained in its concepts. The most obvious form of synthetic judgement is a simple empirical observation.

Philosophers such as

David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist who was best known for his highly influential system of empiricism, philosophical scepticism and metaphysical naturalism. Beg ...

believed that these were the only possible kinds of human reason and investigation, which Hume called "relations of ideas" and "matters of fact". Establishing the synthetic ''a priori'' as a third mode of knowledge would allow Kant to push back against Hume's skepticism about such matters as causation and metaphysical knowledge more generally. This is because, unlike ''a posteriori'' cognition, ''a priori'' cognition has "true or strict ... universality" and includes a claim of "necessity". Kant himself regards it as uncontroversial that we do have synthetic ''a priori'' knowledgeespecially in mathematics. That 7 + 5 = 12, he claims, is a result not contained in the concepts of seven, five, and the addition operation. Yet, although he considers the possibility of such knowledge to be obvious, Kant nevertheless assumes the burden of providing a philosophical proof that we have ''a priori'' knowledge in mathematics, the natural sciences, and metaphysics. It is the twofold aim of the ''Critique'' both ''to prove'' and ''to explain'' the possibility of this knowledge. Kant says "There are two stems of human cognition, which may perhaps arise from a common but to us unknown root, namely sensibility and understanding, through the first of which objects are ''given'' to us, but through the second of which they are ''thought''."

Kant's term for the object of sensibility is intuition, and his term for the object of the understanding is concept. In general terms, the former is a non-discursive representation of a ''particular'' object, and the latter is a discursive (or mediate) representation of a ''general type'' of object. The conditions of possible experience require both intuitions and concepts, that is, the affection of the receptive sensibility and the actively synthesizing power of the understanding. Thus the statement: "Thoughts without content are empty, intuitions without concepts are blind." Kant's basic strategy in the first half of his book will be to argue that some intuitions and concepts are purethat is, are contributed entirely by the mind, independent of anything empirical. Knowledge generated on this basis, under certain conditions, can be synthetic ''a priori''. This insight is known as Kant's "Copernican revolution", because, just as Copernicus advanced astronomy by way of a radical shift in perspective, so Kant here claims do the same for metaphysics. The second half of the ''Critique'' is the explicitly ''critical'' part. In this "transcendental dialectic", Kant argues that many of the claims of traditional rationalist metaphysics violate the criteria he claims to establish in the first, "constructive" part of his book. As Kant observes, however, "human reason, without being moved by the mere vanity of knowing it all, inexorably pushes on, driven by its own need to such questions that cannot be answered by any experiential use of reason". It is the project of "the critique of pure reason" to establish the limits as to just how far reason may legitimately so proceed.

Doctrine of transcendental idealism

The section of the ''Critique'' entitled "The transcendental aesthetic" introduces Kant's famous metaphysics of

transcendental idealism

Transcendental idealism is a philosophical system founded by German philosopher Immanuel Kant in the 18th century. Kant's epistemological program is found throughout his '' Critique of Pure Reason'' (1781). By ''transcendental'' (a term that des ...

. Something is "transcendental" if it is a necessary condition for the possibility of experience, and "idealism" denotes some form of mind-dependence that must be further specified. The correct interpretation of Kant's own specification remains controversial. The metaphysical thesis then states that human beings only experience and know phenomenal appearances, not independent things-in-themselves, because space and time are nothing but the subjective forms of intuition that we ourselves contribute to experience. Nevertheless, although Kant says that space and time are "transcendentally ideal"—the ''pure forms'' of human sensibility, rather than part of nature or reality as it exists in-itself—he also claims that they are "empirically real", by which he means "that 'everything that can come before us externally as an object' is in both space and time, and that our internal intuitions of ourselves are in time". However Kant's doctrine is interpreted, he wished to distinguish his position from the

subjective idealism of

Berkeley.

Paul Guyer

Paul Guyer () is an American philosopher and a leading scholar of Immanuel Kant and of aesthetics. From 2012, he was Jonathan Nelson Professor of Philosophy and Humanities at Brown University until his retirement in 2023. In 2025, he was elected t ...

, although critical of many of Kant's arguments in this section, writes of the "Transcendental Aesthetic" that it "not only lays the first stone in Kant's constructive theory of knowledge; it also lays the foundation for both his critique and his reconstruction of traditional metaphysics. It argues that all genuine knowledge requires a sensory component, and thus that metaphysical claims that transcend the possibility of sensory confirmation can never amount to knowledge."

Interpretive disagreements

One interpretation, known as the "two-world" interpretation, regards Kant's position as a statement of epistemological limitation, meaning that we are not able to transcend the bounds of our own mind, and therefore cannot access the "

thing-in-itself". On this particular view, the thing-in-itself is not numerically identical to the phenomenal empirical object. Kant also spoke, however, of the thing-in-itself or ''transcendent object'' as a product of the (human) understanding as it attempts to conceive of objects in abstraction from the conditions of sensibility. Following this line of thought, a different interpretation argues that the thing-in-itself does not represent a separate ontological domain but simply a way of considering objects by means of the understanding alone; this is known as the "two-aspect" view. On this alternative view, the same objects to which we attribute empirical properties like color, size, and shape are also, when considered as they are in themselves, the things-in-themselves, otherwise inaccessible to human knowledge.

Kant's theory of judgment

Following the "Transcendental Analytic" is the "Transcendental Logic". Whereas the former was concerned with the contributions of the sensibility, the latter is concerned, first, with the contributions of the understanding ("Transcendental Analytic") and, second, with the faculty of ''reason'' as the source of both metaphysical errors and genuine regulatory principles ("Transcendental Dialectic"). The "Transcendental Analytic" is further divided into two sections. The first, "Analytic of Concepts", is concerned with establishing the universality and necessity of the ''pure'' concepts of the understanding (i.e., the categories). This section contains Kant's famous "transcendental deduction". The second, "Analytic of Principles", is concerned with the application of those pure concepts in ''empirical'' judgments. This second section is longer than the first and is further divided into many sub-sections.

Transcendental deduction of the categories of the understanding

The "Analytic of Concepts" argues for the universal and necessary validity of the pure concepts of the understanding, or the categories, for instance, the concepts of substance and causation. These twelve basic categories define what it is to be a ''thing in general''that is, they articulate the necessary conditions according to which something is a possible object of experience. These, in conjunction with the ''a priori'' forms of intuition, are the basis of all synthetic ''a priori'' cognition. According to

Guyer and

Wood

Wood is a structural tissue/material found as xylem in the stems and roots of trees and other woody plants. It is an organic materiala natural composite of cellulosic fibers that are strong in tension and embedded in a matrix of lignin t ...

, "Kant's idea is that just as there are certain essential features of all judgments, so there must be certain corresponding ways in which we form the concepts of objects so that judgments may be about objects."

Kant provides two central lines of argumentation in support of his claims about the categories. The first, known as the "metaphysical deduction", proceeds analytically from a table of the Aristotelian logical functions of judgment. As Kant was aware, this assumes precisely what the skeptic rejects, namely, the existence of synthetic ''a priori'' cognition. For this reason, Kant also supplies a synthetic argument that does not depend upon the assumption in dispute.

This argument, provided under the heading "Transcendental Deduction of the Pure Concepts of the Understanding", is widely considered to be both the most important and the most difficult of Kant's arguments in the ''Critique''. Kant himself said that it is the one that cost him the most labor. Frustrated by its confused reception in the first edition of his book, he rewrote it entirely for the second edition.

The "Transcendental Deduction" gives Kant's argument that these pure concepts apply universally and necessarily to the objects that are given in experience. According to Guyer and Wood, "He centers his argument on the premise that our experience can be ascribed to a single identical subject, via what he calls the 'transcendental unity of apperception,' only if the elements of experience given in intuition are synthetically combined so as to present us with objects that are thought through the categories."

Kant's principle of apperception is that "The I think must be able to accompany all my representations; for otherwise something would be represented in me that could not be thought at all, which is as much as to say that the representation would either be impossible or else at least would be nothing for me." The ''necessary'' possibility of the self-ascription of the representations of self-consciousness, identical to itself through time, is an ''a priori'' conceptual truth that cannot be based on experience. This is only a bare sketch of one of the arguments that Kant presents.

Principles of pure understanding

Kant's deduction of the categories in the "Analytic of Concepts", if successful, demonstrates its claims about the categories only in an abstract way. The task of the "Analytic of Principles" is to show both ''that'' they must universally apply to objects given in actual experience (i.e., manifolds of intuition) and ''how'' it is they do so. In the first book of this section on the "

schematism", Kant connects each of the purely logical categories of the understanding to the temporality of intuition to show that, although non-empirical, they do have purchase upon the objects of experience. The second book continues this line of argument in four chapters, each associated with one of the category groupings. In some cases, it adds a connection to the spatial dimension of intuition to the categories it analyzes. The fourth chapter of this section, "The Analogies of Experience", marks a shift from "mathematical" to "dynamical" principles, that is, to those that deal with relations among objects. Some commentators consider this the most significant section of the ''Critique''. The analogies are three in number:

# ''Principle of persistence of substance'': Kant is here concerned with the general conditions of determining time-relations among the objects of experience. He argues that the unity of time implies that "all change must consist in the alteration of states in an underlying substance, whose existence and quantity must be unchangeable or conserved."

# ''Principle of temporal succession according to the law of causality'': Here Kant argues that "we can make determinate judgments about the objective succession of events, as contrasted to merely subjective successions of representations, only if every objective alteration follows a necessary rule of succession, or a causal law." This is Kant's most direct rejoinder to

Hume's skepticism about causality.

# ''Principle of simultaneity according to the law of reciprocity or community'': The final analogy argues that "determinate judgments that objects (or states of substance) in different regions of space exists simultaneously are possible only if such objects stand in mutual causal relation of community or reciprocal interaction." This is Kant's rejoinder to

Leibniz's thesis in the ''

Monadology''.

The fourth section of this chapter, which is not an analogy, deals with the empirical use of the modal categories. That was the end of the chapter in the A edition of the ''Critique''. The B edition includes one more short section, "The Refutation of Idealism". In this section, by analysis of the concept of self-consciousness, Kant argues that his transcendental idealism is a "critical" or "formal" idealism that does not deny the existence of reality apart from our subjective representations. The final chapter of "The Analytic of Principles" distinguishes ''phenomena'', of which we can have genuine knowledge, from ''noumena'', a term which refers to objects of pure thought that we cannot know, but to which we may still refer "in a negative sense". An Appendix to the section further develops Kant's criticism of Leibnizian-Wolffian rationalism by arguing that its "dogmatic" metaphysics confuses the "mere features of concepts through which we think things ...

ithfeatures of the objects themselves". Against this, Kant reasserts his own insistence upon the necessity of a sensible component in all genuine knowledge.

Critique of metaphysics

The second of the two Divisions of "The Transcendental Logic", "The Transcendental Dialectic", contains the "negative" portion of Kant's ''Critique'', which builds upon the "positive" arguments of the preceding "Transcendental Analytic" to expose the limits of metaphysical speculation. In particular, it is concerned to demonstrate as spurious the efforts of reason to arrive at knowledge independent of sensibility. This endeavor, Kant argues, is doomed to failure, which he claims to demonstrate by showing that reason, unbounded by sense, is always capable of generating opposing or otherwise incompatible conclusions. Like "the light dove, in free flight cutting through the air, the resistance of which it feels", reason "could get the idea that it could do even better in airless space". Against this, Kant claims that, absent epistemic friction, there can be no knowledge. Nevertheless, Kant's critique is not entirely destructive. He presents the speculative excesses of traditional metaphysics as inherent in our very capacity of reason. Moreover, he argues that its products are not without some (carefully qualified) ''regulative'' value.

On the concepts of pure reason

Kant calls the basic concepts of metaphysics "ideas". They are different from the concepts of understanding in that they are not limited by the critical stricture limiting knowledge to the conditions of possible experience and its objects. "Transcendental illusion" is Kant's term for the tendency of reason to produce such ideas. Although reason has a "logical use" of simply drawing inferences from principles, in "The Transcendental Dialectic", Kant is concerned with its purportedly "real use" to arrive at conclusions by way of unchecked regressive syllogistic ratiocination. The three categories of ''relation'', pursued without regard to the limits of possible experience, yield the three central ideas of traditional metaphysics:

# ''The soul'': the concept of substance as the ultimate subject;

# ''The world in its entirety'': the concept of causation as a completed series; and

# ''God'': the concept of community as the common ground of all possibilities.

Although Kant denies that these ideas can be objects of genuine cognition, he argues that they are the result of reason's inherent drive to unify cognition into a systematic whole. Leibnizian-Wolffian metaphysics was divided into four parts: ontology, psychology, cosmology, and theology. Kant replaces the first with the positive results of the first part of the ''Critique''. He proposes to replace the following three with his later doctrines of anthropology, the metaphysical foundations of natural science, and the critical postulation of human freedom and morality.

Dialectical inferences of pure reason

In the second of the two Books of "The Transcendental Dialectic", Kant undertakes to demonstrate the contradictory nature of unbounded reason. He does this by developing contradictions in each of the three metaphysical disciplines that he contends are in fact pseudosciences. This section of the ''Critique'' is long and Kant's arguments are extremely detailed. In this context, it not possible to do much more than enumerate the topics of discussion. The first chapter addresses what Kant terms the ''paralogisms''i.e., false inferencesthat pure reason makes in the metaphysical discipline of rational psychology. He argues that one cannot take the mere thought of "I" in the proposition "I think" as the proper cognition of "I" as an object. In this way, he claims to debunk various metaphysical theses about the substantiality, unity, and self-identity of the soul. The second chapter, which is the longest, takes up the topic Kant calls the

''antinomies of pure reason''that is, the contradictions of reason with itselfin the metaphysical discipline of rational cosmology. Originally, Kant had thought that all transcendental illusion could be analyzed in

antinomic terms. He presents four cases in which he claims reason is able to prove opposing theses with equal plausibility:

# That "reason seems to be able to prove that the universe is both finite and infinite in space and time";

# that "reason seems to be able to prove that matter both is and is not infinitely divisible into ever smaller parts";

# that "reason seems to be able to prove that free will cannot be a causally efficacious part of the world (because all of nature is deterministic) and yet that it must be such a cause"; and,

# that "reason seems to be able to prove that there is and there is not a necessary being (which some would identify with God)".

Kant further argues in each case that his doctrine of transcendental idealism is able to resolve the antinomy. The third chapter examines fallacious arguments about God in rational theology under the heading of the "Ideal of Pure Reason". (Whereas an ''idea'' is a pure concept generated by reason, an ''ideal'' is the concept of an idea as an ''individual thing''.) Here Kant addresses and claims to refute three traditional arguments for the existence of God: the

ontological argument

In the philosophy of religion, an ontological argument is a deductive philosophical argument, made from an ontological basis, that is advanced in support of the existence of God. Such arguments tend to refer to the state of being or existing. ...

, the

cosmological argument, and the

physio-theological argument (i.e., the argument from design). The results of the transcendental dialectic so far appear to be entirely negative. In an Appendix to this section, Kant rejects such a conclusion. The ideas of pure reason, he argues, have an important ''regulatory'' function in directing and organizing our theoretical and practical inquiry. Kant's later works elaborate upon this function at length and in detail.

Moral thought

Kant developed his ethics, or moral philosophy, in three works: ''

Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals'' (1785), ''

Critique of Practical Reason'' (1788), and ''

Metaphysics of Morals'' (1797).

With regard to

morality

Morality () is the categorization of intentions, Decision-making, decisions and Social actions, actions into those that are ''proper'', or ''right'', and those that are ''improper'', or ''wrong''. Morality can be a body of standards or principle ...

, Kant argued that the source of the

good

In most contexts, the concept of good denotes the conduct that should be preferred when posed with a choice between possible actions. Good is generally considered to be the opposite of evil. The specific meaning and etymology of the term and its ...

lies not in anything outside the

human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are Hominidae, great apes characterized by their Prehistory of nakedness and clothing ...

subject, either in

nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

or given by

God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

, but rather is only the good will itself. A good will is one that acts from duty in accordance with the universal moral law that the autonomous human being freely gives itself. This law obliges one to treat humanityunderstood as rational agency, and represented through oneself as well as othersas an

end in itself rather than (merely) as

means to other ends the individual might hold. Kant is known for his theory that all

moral obligation

An obligation is a course of action which someone is required to take, be it a legal obligation or a moral obligation. Obligations are constraints; they limit freedom. People who are under obligations may choose to freely act under obligations. ...

is grounded in what he calls the "

categorical imperative

The categorical imperative () is the central philosophical concept in the deontological Kantian ethics, moral philosophy of Immanuel Kant. Introduced in Kant's 1785 ''Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals'', it is a way of evaluating motivati ...

", which is derived from the concept of

duty. He argues that the moral law is a principle of

reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing valid conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, religion, scien ...

itself, not based on contingent facts about the world, such as what would make us happy; to act on the moral law has no other motive than "worthiness to be happy".

Idea of freedom

In the ''Critique of Pure Reason'', Kant distinguishes between the transcendental idea of freedom, which as a psychological concept is "mainly empirical" and refers to "whether a faculty of beginning a series of successive things or states from itself is to be assumed",

[Kant, ''CPuR'' A448/B467] and the practical concept of freedom as the independence of our will from the "coercion" or "necessitation through sensuous impulses". Kant finds it a source of difficulty that the practical idea of freedom is founded on the transcendental idea of freedom, but for the sake of practical interests uses the practical meaning, taking "no account of ... its transcendental meaning", which he feels was properly "disposed of" in the Third Antinomy, and as an element in the question of the freedom of the will is for philosophy "a real stumbling block" that has embarrassed speculative reason.

Kant calls ''practical'' "everything that is possible through freedom"; he calls the pure practical laws that are never given through sensuous conditions, but are held analogously with the universal law of causality, moral laws. Reason can give us only the "pragmatic laws of free action through the senses", but pure practical laws given by reason ''a priori'' dictate "what is to be done".

Kant's categories of freedom function primarily as conditions for the possibility for actions (i) to be free, (ii) to be understood as free, and (iii) to be morally evaluated. For Kant, although actions as theoretical objects are constituted by means of the theoretical categories, actions as practical objects (objects of practical use of reason, and which can be good or bad) are constituted by means of the categories of freedom. Only in this way can actions, as phenomena, be a consequence of freedom, and be understood and evaluated as such.

Categorical imperative

Kant makes a distinction between categorical and

hypothetical imperatives. A ''hypothetical'' imperative is one that must be obeyed to satisfy contingent desires. A ''categorical'' imperative binds

rational agents regardless of their desires: for example, all rational agents have a duty to respect other rational agents as individual ends in themselves, regardless of circumstances, even though it is sometimes in one's selfish interest to not do so. These imperatives are morally binding because of the categorical form of their maxims, rather than contingent facts about an agent. Unlike hypothetical imperatives, which bind us insofar as we are part of a group or society which we owe duties to, we cannot opt out of the categorical imperative, because we cannot opt out of being rational agents. We owe a duty to rationality by virtue of being rational agents; therefore, rational moral principles apply to all rational agents at all times. Stated in other terms, with all forms of instrumental rationality excluded from morality, "the moral law itself, Kant holds, can only be the form of lawfulness itself, because nothing else is left once all content has been rejected".

Kant provides three formulations for the categorical imperative. He claims that these are necessarily equivalent, as all being expressions of the pure universality of the moral law as such; many scholars are not convinced. The formulas are as follows:

* ''Formula of Universal Law'':

**"Act only in accordance with that maxim through which you at the same time can will that it become a universal law";

[Kant, ''G'' 4:421] alternatively,

***''Formula of the Law of Nature'': "So act, as if the maxim of your action were to become through your will a universal law of nature."

* ''Formula of Humanity as End in Itself'':

**"So act that you use humanity, as much in your own person as in the person of every other, always at the same time as an end and never merely as a means".

* ''Formula of Autonomy'':

**"the idea of the will of every rational being as a will giving universal law", or "Not to choose otherwise than so that the maxims of one's choice are at the same time comprehended with it in the same volition as universal law"; alternatively,

***''Formula of the Realm of Ends'': "Act in accordance with maxims of a universally legislative member for a merely possible realm of ends."

Kant defines ''maxim'' as a "subjective principle of volition", which is distinguished from an "objective principle or 'practical law. While "the latter is valid for every rational being and is a 'principle according to which they ought to act

a maxim 'contains the practical rule which reason determines in accordance with the conditions of the subject (often their ignorance or inclinations) and is thus the principle according to which the subject does act.

Maxims fail to qualify as practical laws if they produce a contradiction in conception or a contradiction in the will when universalized. A contradiction in conception happens when, if a maxim were to be universalized, it ceases to make sense, because the "maxim would necessarily destroy itself as soon as it was made a universal law". For example, if the maxim 'It is permissible to break promises' was universalized, no one would trust any promises made, so the idea of a promise would become meaningless; the maxim would be

self-contradictory because, when it is universalized, promises cease to be meaningful. The maxim is not moral because it is logically impossible to universalizethat is, we could not conceive of a world where this maxim was universalized. A maxim can also be immoral if it creates a contradiction in the will when universalized. This does not mean a logical contradiction, but that universalizing the maxim leads to a state of affairs that no ''rational'' being would desire.

"The Doctrine of Virtue"

As Kant explains in the 1785 ''

Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals'' and as its title directly indicates, that text is "nothing more than the search for and establishment of the ''supreme principle of morality''". His promised ''Metaphysics of Morals'' was much delayed and did not appear until its two parts, "The Doctrine of Right" and "The Doctrine of Virtue", were published separately in 1797 and 1798. The first deals with political philosophy, the second with ethics. "The Doctrine of Virtue" provides "a very different account of ordinary moral reasoning" than the one suggested by the ''Groundwork''. It is concerned with ''duties of virtue'' or "ends that are at the same time duties". It is here, in the domain of ethics, that the greatest innovation by ''The Metaphysics of Morals'' is to be found. According to Kant's account, "ordinary moral reasoning is fundamentally teleologicalit is reasoning about what ends we are constrained by morality to pursue, and the priorities among these ends we are required to observe".

There are two sorts of ends that it is our duty to have: our own perfection and the happiness of others (''MS'' 6:385). "Perfection" includes both our natural perfection (the development of our talents, skills, and capacities of understanding) and moral perfection (our virtuous disposition) (''MS'' 6:387). A person's "happiness" is the greatest rational whole of the ends the person set for the sake of her own satisfaction (''MS'' 6:387–388).

Kant's elaboration of this teleological doctrine offers up a moral theory very different from the one typically attributed to him on the basis of his foundational works alone.

Political philosophy

In ''Towards Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Project'', Kant listed several conditions that he thought necessary for ending wars and creating a lasting peace. They included a world of constitutional republics. His

classical republican theory was extended in the ''Doctrine of Right'', the first part of the ''

Metaphysics of Morals'' (1797). Kant believed that

universal history Universal history may refer to:

* Universal history (genre), a literary genre

**''Jami' al-tawarikh'', 14th-century work of literature and history, produced by the Mongol Ilkhanate in Persia

** Universal History (Sale et al), ''Universal History'' ...

leads to the ultimate world of republican states at peace, but his theory was not pragmatic. The process was described in ''Perpetual Peace'' as natural rather than rational:

Kant's political thought can be summarized as republican government and international organization: "In more characteristically Kantian terms, it is doctrine of the state based upon the law (''

Rechtsstaat

''Rechtsstaat'' (; lit. "state of law"; "legal state") is a doctrine in continental European legal thinking, originating in Germany, German jurisprudence. It can be translated into English as "rule of law", alternatively "legal state", state of l ...

'') and of eternal peace. Indeed, in each of these formulations, both terms express the same idea: that of legal constitution or of 'peace through law. "Kant's political philosophy, being essentially a legal doctrine, rejects by definition the opposition between moral education and the play of passions as alternate foundations for social life. The state is defined as the union of men under law. The state rightly so called is constituted by laws which are necessary a priori because they flow from the very concept of law. A regime can be judged by no other criteria nor be assigned any other functions, than those proper to the lawful order as such."

Kant opposed "democracy", which at his time meant

direct democracy

Direct democracy or pure democracy is a form of democracy in which the Election#Electorate, electorate directly decides on policy initiatives, without legislator, elected representatives as proxies, as opposed to the representative democracy m ...

, believing that majority rule posed a threat to individual liberty. He stated that "''democracy'' in the strict sense of the word is necessarily a ''despotism'' because it establishes an executive power in which all decide for and, if need be, against one (who thus does not agree), so that all, who are nevertheless not all, decide; and this is a contradiction of the general will with itself and with freedom."

As with most writers at the time, Kant distinguished three forms of governmentnamely, democracy, aristocracy, and monarchywith

mixed government

Mixed government (or a mixed constitution) is a form of government that combines elements of democracy, aristocracy and monarchy, ostensibly making impossible their respective degenerations which are conceived in Aristotle's ''Politics'' as a ...

as the most ideal form of it. He believed in

republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

an ideals and forms of governance, and

rule of law

The essence of the rule of law is that all people and institutions within a Body politic, political body are subject to the same laws. This concept is sometimes stated simply as "no one is above the law" or "all are equal before the law". Acco ...

brought on by them. Although Kant published this as a "popular piece",

Mary J. Gregor points out that two years later, in ''The Metaphysics of Morals'', Kant claims to demonstrate ''systematically'' that "establishing universal and lasting peace constitutes not merely a part of the doctrine of right, but rather the entire final end of the doctrine of right within the limits of mere reason".

''The Doctrine of Right'', published in 1797, contains Kant's most mature and systematic contribution to political philosophy. It addresses duties according to law, which are "concerned only with protecting the external freedom of individuals" and indifferent to incentives. Although there is a moral duty "to limit ourselves to actions that are right, that duty is not part of

ightitself". Its basic political idea is that "each person's entitlement to be his or her own master is only consistent with the entitlements of others if public legal institutions are in place". He formulates the universal principle of right as:

Religious writings

Starting in the 20th century, commentators tended to see Kant as having a strained relationship with religion, although in the nineteenth century this had not been the prevalent view.

Karl Leonhard Reinhold, whose letters helped make Kant famous, wrote: "I believe that I may infer without reservation that the interest of religion, and of Christianity in particular, accords completely with the result of the Critique of Reason." According to

Johann Schultz, who wrote one of the first commentaries on Kant: "And does not this system itself cohere most splendidly with the Christian religion? Do not the divinity and beneficence of the latter become all the more evident?" The reason for these views was Kant's moral theology and the widespread belief that his philosophy was the great antithesis to

Spinozism, which was widely seen as a form of sophisticated pantheism or even atheism. As Kant's philosophy disregarded the possibility of arguing for God through pure reason alone, for the same reasons it also disregarded the possibility of arguing against God through pure reason alone.

Kant directs his strongest criticisms of the organization and practices of religious organizations at those that encourage what he sees as a religion of counterfeit service to God. Among the major targets of his criticism are external ritual, superstition, and a hierarchical church order. He sees these as efforts to make oneself pleasing to God in ways other than conscientious adherence to the principle of moral rightness in choosing and acting upon one's maxims. Kant's criticisms on these matters, along with his rejection of certain theoretical proofs for the existence of God that were grounded in pure reason (particularly the

ontological argument