Ice Ax on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ice is

Ice possesses a regular

Ice possesses a regular  When ice melts, it absorbs as much

When ice melts, it absorbs as much

Most liquids under increased pressure freeze at ''higher'' temperatures because the pressure helps to hold the molecules together. However, the strong hydrogen bonds in water make it different: for some pressures higher than , water freezes at a temperature ''below'' . Ice, water, and

Most liquids under increased pressure freeze at ''higher'' temperatures because the pressure helps to hold the molecules together. However, the strong hydrogen bonds in water make it different: for some pressures higher than , water freezes at a temperature ''below'' . Ice, water, and

Ice is " slippery" because it has a low coefficient of friction. This subject was first scientifically investigated in the 19th century. The preferred explanation at the time was " pressure melting" -i.e. the blade of an ice skate, upon exerting pressure on the ice, would melt a thin layer, providing sufficient lubrication for the blade to glide across the ice. Yet, 1939 research by Frank P. Bowden and T. P. Hughes found that skaters would experience a lot more friction than they actually do if it were the only explanation. Further, the optimum temperature for figure skating is and for hockey; yet, according to pressure melting theory, skating below would be outright impossible. Instead, Bowden and Hughes argued that heating and melting of the ice layer is caused by friction. However, this theory does not sufficiently explain why ice is slippery when standing still even at below-zero temperatures.

Subsequent research suggested that ice molecules at the interface cannot properly bond with the molecules of the mass of ice beneath (and thus are free to move like molecules of liquid water). These molecules remain in a semi-liquid state, providing lubrication regardless of pressure against the ice exerted by any object. However, the significance of this hypothesis is disputed by experiments showing a high

Ice is " slippery" because it has a low coefficient of friction. This subject was first scientifically investigated in the 19th century. The preferred explanation at the time was " pressure melting" -i.e. the blade of an ice skate, upon exerting pressure on the ice, would melt a thin layer, providing sufficient lubrication for the blade to glide across the ice. Yet, 1939 research by Frank P. Bowden and T. P. Hughes found that skaters would experience a lot more friction than they actually do if it were the only explanation. Further, the optimum temperature for figure skating is and for hockey; yet, according to pressure melting theory, skating below would be outright impossible. Instead, Bowden and Hughes argued that heating and melting of the ice layer is caused by friction. However, this theory does not sufficiently explain why ice is slippery when standing still even at below-zero temperatures.

Subsequent research suggested that ice molecules at the interface cannot properly bond with the molecules of the mass of ice beneath (and thus are free to move like molecules of liquid water). These molecules remain in a semi-liquid state, providing lubrication regardless of pressure against the ice exerted by any object. However, the significance of this hypothesis is disputed by experiments showing a high

The term that collectively describes all of the parts of the Earth's surface where water is in frozen form is the ''

The term that collectively describes all of the parts of the Earth's surface where water is in frozen form is the ''

Multi-language

) ''World Meteorological Organization'' / '' Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute''. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

File:GreaseIce2.jpg, Grease ice in the

Ice which forms on moving water tends to be less uniform and stable than ice which forms on calm water.

Ice which forms on moving water tends to be less uniform and stable than ice which forms on calm water.

Ice forms on calm water from the shores, a thin layer spreading across the surface, and then downward. Ice on lakes is generally four types: primary, secondary, superimposed and agglomerate. Primary ice forms first. Secondary ice forms below the primary ice in a direction parallel to the direction of the heat flow. Superimposed ice forms on top of the ice surface from rain or water which seeps up through cracks in the ice which often settles when loaded with snow. An

Ice forms on calm water from the shores, a thin layer spreading across the surface, and then downward. Ice on lakes is generally four types: primary, secondary, superimposed and agglomerate. Primary ice forms first. Secondary ice forms below the primary ice in a direction parallel to the direction of the heat flow. Superimposed ice forms on top of the ice surface from rain or water which seeps up through cracks in the ice which often settles when loaded with snow. An

Snow crystals form when tiny supercooled cloud droplets (about 10

Snow crystals form when tiny supercooled cloud droplets (about 10

Ice pellets (

Ice pellets (

File:Saint-Amant_16_Gelée_blanche_2008.jpg, Grass partially covered in hoarfrost, 2008

File:Dülmen, Hausdülmen, Distel -- 2021 -- 5079.jpg, Frost on a thistle in Hausdülmen,

Ice has long been valued as a means of cooling. In 400 BC Iran,

Ice has long been valued as a means of cooling. In 400 BC Iran,

Between 1812 and 1822, under Lloyd Hesketh Bamford Hesketh's instruction, Gwrych Castle was built with 18 large towers, one of those towers is called the 'Ice Tower'. Its sole purpose was to store Ice.

Between 1812 and 1822, under Lloyd Hesketh Bamford Hesketh's instruction, Gwrych Castle was built with 18 large towers, one of those towers is called the 'Ice Tower'. Its sole purpose was to store Ice.

The earliest known written process to artificially make ice is by the 13th-century writings of Arab historian Ibn Abu Usaybia in his book ''Kitab Uyun al-anba fi tabaqat-al-atibba'' concerning medicine in which Ibn Abu Usaybia attributes the process to an even older author, Ibn Bakhtawayhi, of whom nothing is known.

Ice is now produced on an industrial scale, for uses including food storage and processing, chemical manufacturing, concrete mixing and curing, and consumer or packaged ice.

The earliest known written process to artificially make ice is by the 13th-century writings of Arab historian Ibn Abu Usaybia in his book ''Kitab Uyun al-anba fi tabaqat-al-atibba'' concerning medicine in which Ibn Abu Usaybia attributes the process to an even older author, Ibn Bakhtawayhi, of whom nothing is known.

Ice is now produced on an industrial scale, for uses including food storage and processing, chemical manufacturing, concrete mixing and curing, and consumer or packaged ice.

For ships, ice presents two distinct hazards. Firstly, spray and freezing rain can produce an ice build-up on the superstructure of a vessel sufficient to make it unstable, potentially to the point of

For ships, ice presents two distinct hazards. Firstly, spray and freezing rain can produce an ice build-up on the superstructure of a vessel sufficient to make it unstable, potentially to the point of

Ice plays a central role in winter recreation and in many sports such as

Ice plays a central role in winter recreation and in many sports such as

* Engineers used the substantial strength of pack ice when they constructed Antarctica's first floating ice pier in 1973. Such ice piers are used during cargo operations to load and offload ships. Fleet operations personnel make the floating pier during the winter. They build upon naturally occurring frozen seawater in

* Engineers used the substantial strength of pack ice when they constructed Antarctica's first floating ice pier in 1973. Such ice piers are used during cargo operations to load and offload ships. Fleet operations personnel make the floating pier during the winter. They build upon naturally occurring frozen seawater in

In the future, the

In the future, the

online review of this book

Webmineral listing for Ice

Estimating the bearing capacity of ice

{{Authority control Glaciology Minerals Transparent materials Articles containing video clips Limnology Oceanography Cryosphere

water

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance. It is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known liv ...

that is frozen into a solid

Solid is a state of matter where molecules are closely packed and can not slide past each other. Solids resist compression, expansion, or external forces that would alter its shape, with the degree to which they are resisted dependent upon the ...

state, typically forming at or below temperatures of 0 ° C, 32 ° F, or 273.15 K. It occurs naturally on Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

, on other planets, in Oort cloud

The Oort cloud (pronounced or ), sometimes called the Öpik–Oort cloud, is scientific theory, theorized to be a cloud of billions of Volatile (astrogeology), icy planetesimals surrounding the Sun at distances ranging from 2,000 to 200,000 A ...

objects, and as interstellar ice. As a naturally occurring crystalline inorganic solid with an ordered structure, ice is considered to be a mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid substance with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2011): Mi ...

. Depending on the presence of impurities

In chemistry and materials science, impurities are chemical substances inside a confined amount of liquid, gas, or solid. They differ from the chemical composition of the material or compound. Firstly, a pure chemical should appear in at least on ...

such as particles of soil

Soil, also commonly referred to as earth, is a mixture of organic matter, minerals, gases, water, and organisms that together support the life of plants and soil organisms. Some scientific definitions distinguish dirt from ''soil'' by re ...

or bubbles of air

An atmosphere () is a layer of gases that envelop an astronomical object, held in place by the gravity of the object. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A stellar atmosph ...

, it can appear transparent or a more or less opaque

Opacity is the measure of impenetrability to electromagnetic or other kinds of radiation, especially visible light. In radiative transfer, it describes the absorption and scattering of radiation in a medium, such as a plasma, dielectric, shie ...

bluish-white color.

Virtually all of the ice on Earth is of a hexagonal

In geometry, a hexagon (from Greek , , meaning "six", and , , meaning "corner, angle") is a six-sided polygon. The total of the internal angles of any simple (non-self-intersecting) hexagon is 720°.

Regular hexagon

A regular hexagon is d ...

crystalline structure

In crystallography, crystal structure is a description of ordered arrangement of atoms, ions, or molecules in a crystalline material. Ordered structures occur from intrinsic nature of constituent particles to form symmetric patterns that repeat ...

denoted as ''ice Ih'' (spoken as "ice one h"). Depending on temperature and pressure, at least nineteen phases ( packing geometries) can exist. The most common phase transition

In physics, chemistry, and other related fields like biology, a phase transition (or phase change) is the physical process of transition between one state of a medium and another. Commonly the term is used to refer to changes among the basic Sta ...

to ice Ih occurs when liquid water is cooled below (, ) at standard atmospheric pressure

The standard atmosphere (symbol: atm) is a unit of pressure defined as Pa. It is sometimes used as a ''reference pressure'' or ''standard pressure''. It is approximately equal to Earth's average atmospheric pressure at sea level.

History

The ...

. When water is cooled rapidly (quenching

In materials science, quenching is the rapid cooling of a workpiece in water, gas, oil, polymer, air, or other fluids to obtain certain material properties. A type of heat treating, quenching prevents undesired low-temperature processes, suc ...

), up to three types of amorphous ice can form. Interstellar ice is overwhelmingly low-density amorphous ice (LDA), which likely makes LDA ice the most abundant type in the universe. When cooled slowly, correlated proton tunneling occurs below (, ) giving rise to macroscopic quantum phenomena

Macroscopic quantum phenomena are processes showing Quantum mechanics, quantum behavior at the macroscopic scale, rather than at the Atom, atomic scale where quantum effects are prevalent. The best-known examples of macroscopic quantum phenomena ar ...

.

Ice is abundant on the Earth's surface, particularly in the polar regions and above the snow line

The climatic snow line is the boundary between a snow-covered and snow-free surface. The actual snow line may adjust seasonally, and be either significantly higher in elevation, or lower. The permanent snow line is the level above which snow wil ...

, where it can aggregate from snow to form glaciers

A glacier (; or ) is a persistent body of dense ice, a form of rock, that is constantly moving downhill under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires ...

and ice sheet

In glaciology, an ice sheet, also known as a continental glacier, is a mass of glacier, glacial ice that covers surrounding terrain and is greater than . The only current ice sheets are the Antarctic ice sheet and the Greenland ice sheet. Ice s ...

s. As snowflakes

A snowflake is a single ice crystal that is large enough to fall through the Earth's atmosphere as snow.Knight, C.; Knight, N. (1973). Snow crystals. Scientific American, vol. 228, no. 1, pp. 100–107.Hobbs, P.V. 1974. Ice Physics. Oxford: C ...

and hail

Hail is a form of solid Precipitation (meteorology), precipitation. It is distinct from ice pellets (American English "sleet"), though the two are often confused. It consists of balls or irregular lumps of ice, each of which is called a hailsto ...

, ice is a common form of precipitation

In meteorology, precipitation is any product of the condensation of atmospheric water vapor that falls from clouds due to gravitational pull. The main forms of precipitation include drizzle, rain, rain and snow mixed ("sleet" in Commonwe ...

, and it may also be deposited directly by water vapor

Water vapor, water vapour, or aqueous vapor is the gaseous phase of Properties of water, water. It is one Phase (matter), state of water within the hydrosphere. Water vapor can be produced from the evaporation or boiling of liquid water or from th ...

as frost

Frost is a thin layer of ice on a solid surface, which forms from water vapor that deposits onto a freezing surface. Frost forms when the air contains more water vapor than it can normally hold at a specific temperature. The process is simila ...

. The transition from ice to water is melting and from ice directly to water vapor is sublimation. These processes plays a key role in Earth's water cycle

The water cycle (or hydrologic cycle or hydrological cycle) is a biogeochemical cycle that involves the continuous movement of water on, above and below the surface of the Earth across different reservoirs. The mass of water on Earth remains fai ...

and climate

Climate is the long-term weather pattern in a region, typically averaged over 30 years. More rigorously, it is the mean and variability of meteorological variables over a time spanning from months to millions of years. Some of the meteoro ...

. In the recent decades, ice volume on Earth has been decreasing due to climate change

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in Global surface temperature, global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate variability and change, Climate change in ...

. The largest declines have occurred in the Arctic

The Arctic (; . ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the North Pole, lying within the Arctic Circle. The Arctic region, from the IERS Reference Meridian travelling east, consists of parts of northern Norway ( ...

and in the mountains located outside of the polar regions. The loss of grounded ice (as opposed to floating sea ice

Sea ice arises as seawater freezes. Because ice is less density, dense than water, it floats on the ocean's surface (as does fresh water ice). Sea ice covers about 7% of the Earth's surface and about 12% of the world's oceans. Much of the world' ...

) is the primary contributor to sea level rise

The sea level has been rising from the end of the last ice age, which was around 20,000 years ago. Between 1901 and 2018, the average sea level rose by , with an increase of per year since the 1970s. This was faster than the sea level had e ...

.

Humans have been using ice for various purposes for thousands of years. Some historic structures designed to hold ice to provide cooling are over 2,000 years old. Before the invention of refrigeration

Refrigeration is any of various types of cooling of a space, substance, or system to lower and/or maintain its temperature below the ambient one (while the removed heat is ejected to a place of higher temperature).IIR International Dictionary of ...

technology, the only way to safely store food without modifying it through preservative

A preservative is a substance or a chemical that is added to products such as food products, beverages, pharmaceutical drugs, paints, biological samples, cosmetics, wood, and many other products to prevent decomposition by microbial growth or ...

s was to use ice. Sufficiently solid surface ice makes waterway

A waterway is any Navigability, navigable body of water. Broad distinctions are useful to avoid ambiguity, and disambiguation will be of varying importance depending on the nuance of the equivalent word in other ways. A first distinction is ...

s accessible to land transport during winter, and dedicated ice road

An ice road or ice bridge is a human-made structure that runs on a frozen water surface (a river, a lake or a sea water expanse).Masterson, D. and Løset, S., 2011, ISO 19906: Bearing capacity of ice and ice roads, Proceedings of the 21st Int ...

s may be maintained. Ice also plays a major role in winter sports.

Physical properties

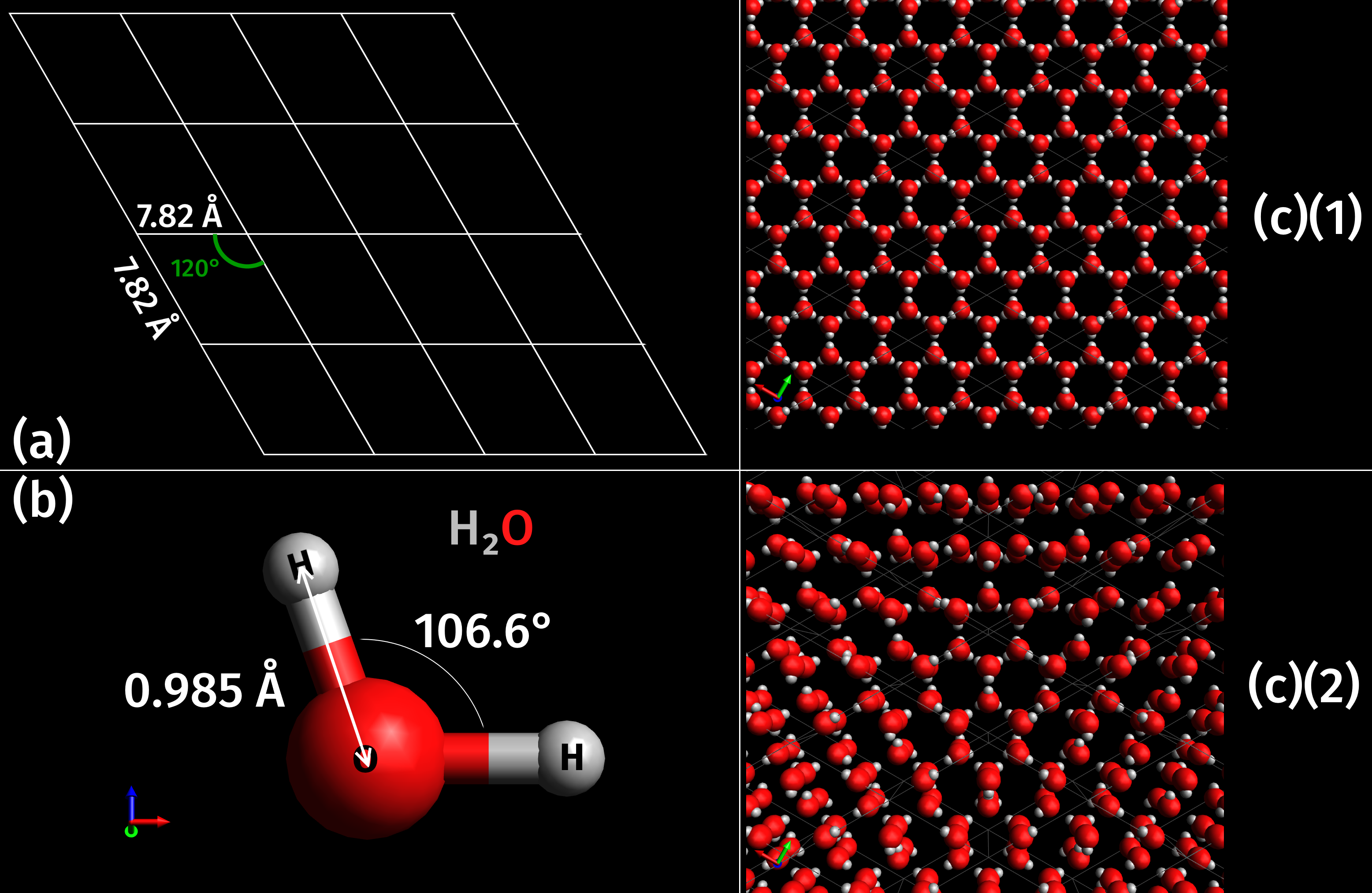

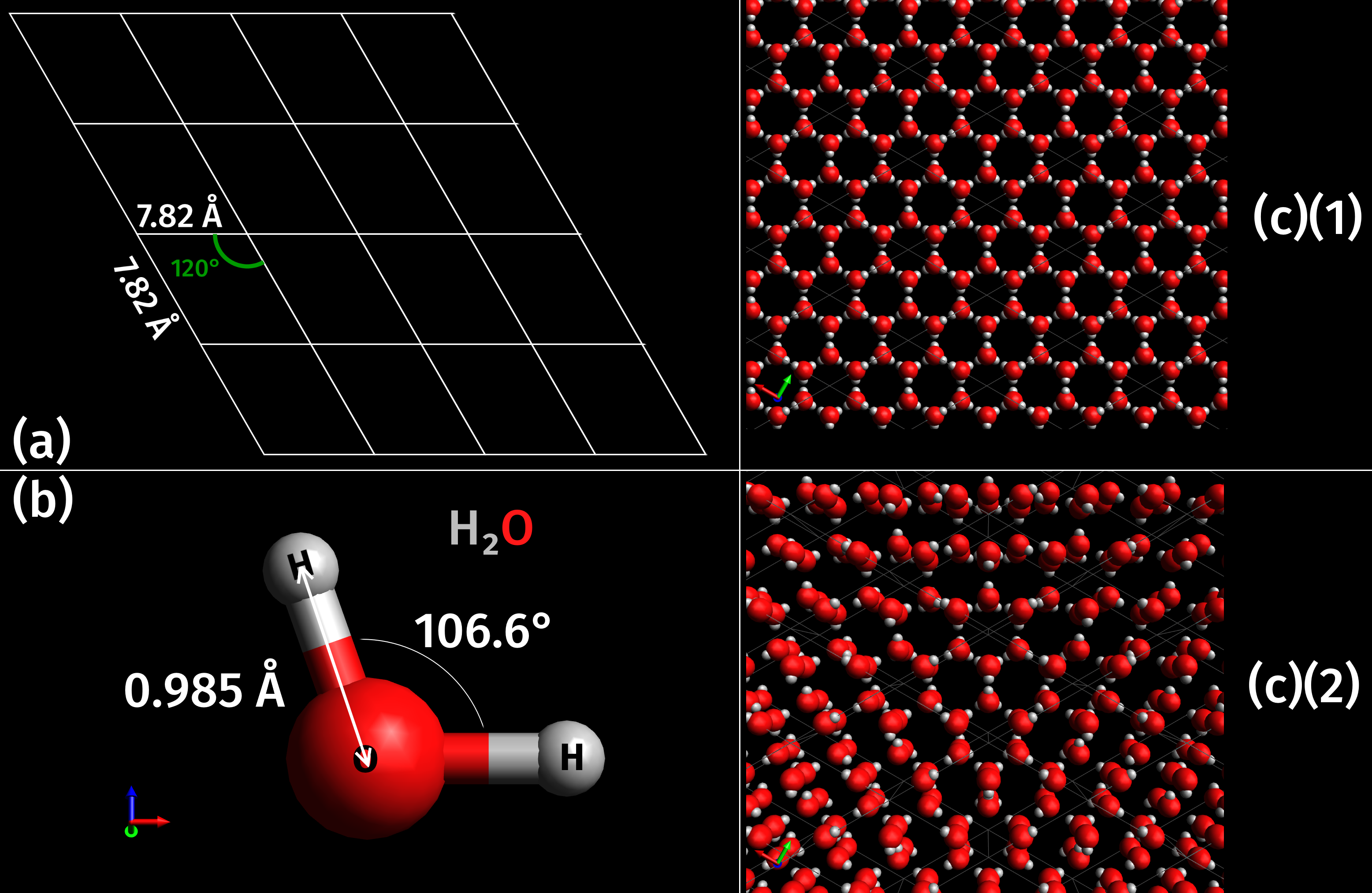

Ice possesses a regular

Ice possesses a regular crystalline

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macrosc ...

structure based on the molecule

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms that are held together by Force, attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions that satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemi ...

of water, which consists of a single oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

atom covalently

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electrons to form electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs. The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atoms ...

bonded to two hydrogen atom

A hydrogen atom is an atom of the chemical element hydrogen. The electrically neutral hydrogen atom contains a single positively charged proton in the nucleus, and a single negatively charged electron bound to the nucleus by the Coulomb for ...

s, or H–O–H. However, many of the physical properties of water and ice are controlled by the formation of hydrogen bond

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (H-bond) is a specific type of molecular interaction that exhibits partial covalent character and cannot be described as a purely electrostatic force. It occurs when a hydrogen (H) atom, Covalent bond, covalently b ...

s between adjacent oxygen and hydrogen atoms; while it is a weak bond, it is nonetheless critical in controlling the structure of both water and ice.

An unusual property of water is that its solid form—ice frozen at atmospheric pressure

Atmospheric pressure, also known as air pressure or barometric pressure (after the barometer), is the pressure within the atmosphere of Earth. The standard atmosphere (symbol: atm) is a unit of pressure defined as , which is equivalent to 1,013. ...

—is approximately 8.3% less dense than its liquid form; this is equivalent to a volumetric expansion of 9%. The density

Density (volumetric mass density or specific mass) is the ratio of a substance's mass to its volume. The symbol most often used for density is ''ρ'' (the lower case Greek letter rho), although the Latin letter ''D'' (or ''d'') can also be u ...

of ice is 0.9167–0.9168 g/cm3 at 0 °C and standard atmospheric pressure (101,325 Pa), whereas water has a density of 0.9998–0.999863 g/cm3 at the same temperature and pressure. Liquid water is densest, essentially 1.00 g/cm3, at 4 °C and begins to lose its density as the water molecules begin to form the hexagonal

In geometry, a hexagon (from Greek , , meaning "six", and , , meaning "corner, angle") is a six-sided polygon. The total of the internal angles of any simple (non-self-intersecting) hexagon is 720°.

Regular hexagon

A regular hexagon is d ...

crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macros ...

s of ice

Ice is water that is frozen into a solid state, typically forming at or below temperatures of 0 ° C, 32 ° F, or 273.15 K. It occurs naturally on Earth, on other planets, in Oort cloud objects, and as interstellar ice. As a naturally oc ...

as the freezing point is reached. This is due to hydrogen bonding dominating the intermolecular forces, which results in a packing of molecules less compact in the solid. The density of ice increases slightly with decreasing temperature and has a value of 0.9340 g/cm3 at −180 °C (93 K).

When water freezes, it increases in volume (about 9% for fresh water). The effect of expansion during freezing can be dramatic, and ice expansion is a basic cause of freeze-thaw weathering of rock in nature and damage to building foundations and roadways from frost heaving

Frost heaving (or a frost heave) is an upwards swelling of soil during freezing conditions caused by an increasing presence of ice as it grows towards the surface, upwards from the depth in the soil where freezing temperatures have penetrated int ...

. It is also a common cause of the flooding of houses when water pipes burst due to the pressure of expanding water when it freezes.

Because ice is less dense than liquid water, it floats, and this prevents bottom-up freezing of the bodies of water. Instead, a sheltered environment for animal and plant life is formed beneath the floating ice, which protects the underside from short-term weather extremes such as wind chill

Wind chill (popularly wind chill factor) is the sensation of cold produced by the wind for a given ambient air temperature on exposed skin as the air motion accelerates the rate of heat transfer from the body to the surrounding atmosphere. Its va ...

. Sufficiently thin floating ice allows light to pass through, supporting the photosynthesis

Photosynthesis ( ) is a system of biological processes by which photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical energy necessary to fuel their metabo ...

of bacterial and algal colonies. When sea water freezes, the ice is riddled with brine-filled channels which sustain sympagic organisms such as bacteria, algae, copepod

Copepods (; meaning 'oar-feet') are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat (ecology), habitat. Some species are planktonic (living in the water column), some are benthos, benthic (living on the sedimen ...

s and annelid

The annelids (), also known as the segmented worms, are animals that comprise the phylum Annelida (; ). The phylum contains over 22,000 extant species, including ragworms, earthworms, and leeches. The species exist in and have adapted to vario ...

s. In turn, they provide food for animals such as krill

Krill ''(Euphausiids)'' (: krill) are small and exclusively marine crustaceans of the order (biology), order Euphausiacea, found in all of the world's oceans. The name "krill" comes from the Norwegian language, Norwegian word ', meaning "small ...

and specialized fish like the bald notothen

The bald notothen (''Pagothenia borchgrevinki''), also known as the bald rockcod, is a species of marine ray-finned fish belonging to the family Nototheniidae, the notothens or cod icefishes. It is native to the Southern Ocean.

Taxonomy

The bal ...

, fed upon in turn by larger animals such as emperor penguins and minke whales.

energy

Energy () is the physical quantity, quantitative physical property, property that is transferred to a physical body, body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of Work (thermodynamics), work and in the form of heat and l ...

as it would take to heat an equivalent mass of water by . During the melting process, the temperature remains constant at . While melting, any energy added breaks the hydrogen bonds between ice (water) molecules. Energy becomes available to increase the thermal energy (temperature) only after enough hydrogen bonds are broken that the ice can be considered liquid water. The amount of energy consumed in breaking hydrogen bonds in the transition from ice to water is known as the ''heat of fusion

In thermodynamics, the enthalpy of fusion of a substance, also known as (latent) heat of fusion, is the change in its enthalpy resulting from providing energy, typically heat, to a specific quantity of the substance to change its state from a s ...

''.

As with water, ice absorbs light at the red end of the spectrum preferentially as the result of an overtone of an oxygen–hydrogen (O–H) bond stretch. Compared with water, this absorption is shifted toward slightly lower energies. Thus, ice appears blue, with a slightly greener tint than liquid water. Since absorption is cumulative, the color effect intensifies with increasing thickness or if internal reflections cause the light to take a longer path through the ice. Other colors can appear in the presence of light absorbing impurities, where the impurity is dictating the color rather than the ice itself. For instance, iceberg

An iceberg is a piece of fresh water ice more than long that has broken off a glacier or an ice shelf and is floating freely in open water. Smaller chunks of floating glacially derived ice are called "growlers" or "bergy bits". Much of an i ...

s containing impurities (e.g., sediments, algae, air bubbles) can appear brown, grey or green.

Because ice in natural environments is usually close to its melting temperature, its hardness shows pronounced temperature variations. At its melting point, ice has a Mohs hardness

The Mohs scale ( ) of mineral hardness is a qualitative ordinal scale, from 1 to 10, characterizing scratch resistance of mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid substance with a fair ...

of 2 or less, but the hardness increases to about 4 at a temperature of and to 6 at a temperature of , the vaporization point of solid carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

(dry ice).

Phases

Most liquids under increased pressure freeze at ''higher'' temperatures because the pressure helps to hold the molecules together. However, the strong hydrogen bonds in water make it different: for some pressures higher than , water freezes at a temperature ''below'' . Ice, water, and

Most liquids under increased pressure freeze at ''higher'' temperatures because the pressure helps to hold the molecules together. However, the strong hydrogen bonds in water make it different: for some pressures higher than , water freezes at a temperature ''below'' . Ice, water, and water vapour

Water vapor, water vapour, or aqueous vapor is the gaseous phase of water. It is one state of water within the hydrosphere. Water vapor can be produced from the evaporation or boiling of liquid water or from the sublimation of ice. Water vapor ...

can coexist at the triple point

In thermodynamics, the triple point of a substance is the temperature and pressure at which the three Phase (matter), phases (gas, liquid, and solid) of that substance coexist in thermodynamic equilibrium.. It is that temperature and pressure at ...

, which is exactly at a pressure of 611.657 Pa. The kelvin

The kelvin (symbol: K) is the base unit for temperature in the International System of Units (SI). The Kelvin scale is an absolute temperature scale that starts at the lowest possible temperature (absolute zero), taken to be 0 K. By de ...

was defined as of the difference between this triple point and absolute zero

Absolute zero is the lowest possible temperature, a state at which a system's internal energy, and in ideal cases entropy, reach their minimum values. The absolute zero is defined as 0 K on the Kelvin scale, equivalent to −273.15 ° ...

, though this definition changed in May 2019. Unlike most other solids, ice is difficult to superheat. In an experiment, ice at −3 °C was superheated to about 17 °C for about 250 picosecond

A picosecond (abbreviated as ps) is a unit of time in the International System of Units (SI) equal to 10−12 or (one trillionth) of a second. That is one trillionth, or one millionth of one millionth of a second, or 0.000 000 000 ...

s.

Subjected to higher pressures and varying temperatures, ice can form in nineteen separate known crystalline phases at various densities, along with hypothetical proposed phases of ice that have not been observed. With care, at least fifteen of these phases (one of the known exceptions being ice X) can be recovered at ambient pressure and low temperature in metastable

In chemistry and physics, metastability is an intermediate energetic state within a dynamical system other than the system's state of least energy.

A ball resting in a hollow on a slope is a simple example of metastability. If the ball is onl ...

form. The types are differentiated by their crystalline structure, proton ordering, and density. There are also two metastable phases of ice under pressure, both fully hydrogen-disordered; these are Ice IV and Ice XII. Ice XII was discovered in 1996. In 2006, Ice XIII and Ice XIV were discovered. Ices XI, XIII, and XIV are hydrogen-ordered forms of ices I, V, and XII respectively. In 2009, ice XV was found at extremely high pressures and −143 °C. At even higher pressures, ice is predicted to become a metal

A metal () is a material that, when polished or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electrical resistivity and conductivity, electricity and thermal conductivity, heat relatively well. These properties are all associated wit ...

; this has been variously estimated to occur at 1.55 TPa or 5.62 TPa.

As well as crystalline forms, solid water can exist in amorphous states as amorphous solid water (ASW) of varying densities. In outer space, hexagonal crystalline ice is present in the ice volcanoes, but is extremely rare otherwise. Even icy moons like Ganymede are expected to mainly consist of other crystalline forms of ice. Water in the interstellar medium

The interstellar medium (ISM) is the matter and radiation that exists in the outer space, space between the star systems in a galaxy. This matter includes gas in ionic, atomic, and molecular form, as well as cosmic dust, dust and cosmic rays. It f ...

is dominated by amorphous ice, making it likely the most common form of water in the universe. Low-density ASW (LDA), also known as hyperquenched glassy water, may be responsible for noctilucent clouds

Noctilucent clouds (NLCs), or night shining clouds, are tenuous cloud-like phenomena in the upper atmosphere of Earth. When viewed from space, they are called polar mesospheric clouds (PMCs), detectable as a diffuse scattering layer of water ice ...

on Earth and is usually formed by deposition of water vapor in cold or vacuum conditions. High-density ASW (HDA) is formed by compression of ordinary ice I or LDA at GPa pressures. Very-high-density ASW (VHDA) is HDA slightly warmed to 160 K under 1–2 GPa pressures.

Ice from a theorized superionic water may possess two crystalline structures. At pressures in excess of such ''superionic ice'' would take on a body-centered cubic

In crystallography, the cubic (or isometric) crystal system is a crystal system where the Crystal structure#Unit cell, unit cell is in the shape of a cube. This is one of the most common and simplest shapes found in crystals and minerals.

There ...

structure. However, at pressures in excess of the structure may shift to a more stable face-centered cubic

In crystallography, the cubic (or isometric) crystal system is a crystal system where the unit cell is in the shape of a cube. This is one of the most common and simplest shapes found in crystals and minerals.

There are three main varieties o ...

lattice. It is speculated that superionic ice could compose the interior of ice giants such as Uranus and Neptune.

Friction properties

Ice is " slippery" because it has a low coefficient of friction. This subject was first scientifically investigated in the 19th century. The preferred explanation at the time was " pressure melting" -i.e. the blade of an ice skate, upon exerting pressure on the ice, would melt a thin layer, providing sufficient lubrication for the blade to glide across the ice. Yet, 1939 research by Frank P. Bowden and T. P. Hughes found that skaters would experience a lot more friction than they actually do if it were the only explanation. Further, the optimum temperature for figure skating is and for hockey; yet, according to pressure melting theory, skating below would be outright impossible. Instead, Bowden and Hughes argued that heating and melting of the ice layer is caused by friction. However, this theory does not sufficiently explain why ice is slippery when standing still even at below-zero temperatures.

Subsequent research suggested that ice molecules at the interface cannot properly bond with the molecules of the mass of ice beneath (and thus are free to move like molecules of liquid water). These molecules remain in a semi-liquid state, providing lubrication regardless of pressure against the ice exerted by any object. However, the significance of this hypothesis is disputed by experiments showing a high

Ice is " slippery" because it has a low coefficient of friction. This subject was first scientifically investigated in the 19th century. The preferred explanation at the time was " pressure melting" -i.e. the blade of an ice skate, upon exerting pressure on the ice, would melt a thin layer, providing sufficient lubrication for the blade to glide across the ice. Yet, 1939 research by Frank P. Bowden and T. P. Hughes found that skaters would experience a lot more friction than they actually do if it were the only explanation. Further, the optimum temperature for figure skating is and for hockey; yet, according to pressure melting theory, skating below would be outright impossible. Instead, Bowden and Hughes argued that heating and melting of the ice layer is caused by friction. However, this theory does not sufficiently explain why ice is slippery when standing still even at below-zero temperatures.

Subsequent research suggested that ice molecules at the interface cannot properly bond with the molecules of the mass of ice beneath (and thus are free to move like molecules of liquid water). These molecules remain in a semi-liquid state, providing lubrication regardless of pressure against the ice exerted by any object. However, the significance of this hypothesis is disputed by experiments showing a high coefficient of friction

Friction is the force resisting the relative motion of solid surfaces, fluid layers, and material elements sliding against each other. Types of friction include dry, fluid, lubricated, skin, and internal -- an incomplete list. The study of t ...

for ice using atomic force microscopy

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) or scanning force microscopy (SFM) is a very-high-resolution type of scanning probe microscopy (SPM), with demonstrated resolution on the order of fractions of a nanometer, more than 1000 times better than the opti ...

. Thus, the mechanism controlling the frictional properties of ice is still an active area of scientific study. A comprehensive theory of ice friction must take into account all of the aforementioned mechanisms to estimate friction coefficient of ice against various materials as a function of temperature and sliding speed. 2014 research suggests that frictional heating is the most important process under most typical conditions.

Natural formation

The term that collectively describes all of the parts of the Earth's surface where water is in frozen form is the ''

The term that collectively describes all of the parts of the Earth's surface where water is in frozen form is the ''cryosphere

The cryosphere is an umbrella term for those portions of Earth's surface where water is in solid form. This includes sea ice, ice on lakes or rivers, snow, glaciers, ice caps, ice sheets, and frozen ground (which includes permafrost). Thus, there ...

.'' Ice is an important component of the global climate, particularly in regard to the water cycle. Glaciers and snowpack

Snowpack is an accumulation of snow that compresses with time and melts seasonally, often at high elevation or high latitude. Snowpacks are an important water resource that feed streams and rivers as they melt, sometimes leading to flooding. Snow ...

s are an important storage mechanism for fresh water; over time, they may sublimate or melt. Snowmelt

In hydrology, snowmelt is surface runoff produced from melting snow. It can also be used to describe the period or season during which such runoff is produced. Water produced by snowmelt is an important part of the annual water cycle in many part ...

is an important source of seasonal fresh water. The World Meteorological Organization

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for promoting international cooperation on atmospheric science, climatology, hydrology an ...

defines several kinds of ice depending on origin, size, shape, influence and so on."WMO SEA-ICE NOMENCLATURE"Multi-language

) ''World Meteorological Organization'' / '' Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute''. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

Clathrate hydrate

Clathrate hydrates, or gas hydrates, clathrates, or hydrates, are crystalline water-based solids physically resembling ice, in which small non-polar molecules (typically gases) or polar molecules with large hydrophobic moieties are trapped ins ...

s are forms of ice that contain gas molecules trapped within its crystal lattice.

In the oceans

Ice that is found at sea may be in the form ofdrift ice

Drift or Drifts may refer to:

Geography

* Drift or ford (crossing) of a river

* Drift (navigation), difference between heading and course of a vessel

* Drift, Kentucky, unincorporated community in the United States

* In Cornwall, England:

** D ...

floating in the water, fast ice

Fast ice (also called ''land-fast ice'', ''landfast ice'', and ''shore-fast ice'') is sea ice or lake ice that is "fastened" to the coastline, to the sea floor along shoals, or to grounded icebergs.Leppäranta, M. 2011. The Drift of Sea Ice. B ...

fixed to a shoreline or anchor ice if attached to the seafloor. Ice which calves (breaks off) from an ice shelf

An ice shelf is a large platform of glacial ice floating on the ocean, fed by one or multiple tributary glaciers. Ice shelves form along coastlines where the ice thickness is insufficient to displace the more dense surrounding ocean water. T ...

or a coastal glacier may become an iceberg. The aftermath of calving events produces a loose mixture of snow and ice known as Ice mélange

Ice mélange refers to a mixture of sea ice types, icebergs, and snow without a clearly defined Drift ice, floe that forms from shearing and fracture at the ice front. Ice mélange is commonly the result of an ice calving event where ice breaks ...

.

Sea ice forms in several stages. At first, small, millimeter-scale crystals accumulate on the water surface in what is known as frazil ice. As they become somewhat larger and more consistent in shape and cover, the water surface begins to look "oily" from above, so this stage is called grease ice. Then, ice continues to clump together, and solidify into flat cohesive pieces known as ice floe

An ice floe () is a segment of floating ice defined as a flat piece at least across at its widest point, and up to more than across. Drift ice is a floating field of sea ice composed of several ice floes. They may cause ice jams on freshwate ...

s. Ice floes are the basic building blocks of sea ice cover, and their horizontal size (defined as half of their diameter

In geometry, a diameter of a circle is any straight line segment that passes through the centre of the circle and whose endpoints lie on the circle. It can also be defined as the longest Chord (geometry), chord of the circle. Both definitions a ...

) varies dramatically, with the smallest measured in centimeters and the largest in hundreds of kilometers. An area which is over 70% ice on its surface is said to be covered by pack ice.

Fully formed sea ice can be forced together by currents and winds to form pressure ridges up to tall. On the other hand, active wave activity can reduce sea ice to small, regularly shaped pieces, known as pancake ice. Sometimes, wind and wave activity "polishes" sea ice to perfectly spherical pieces known as ice eggs

Ice eggs, or ice balls, are a rare phenomenon caused by a process in which small pieces of sea ice in open water are rolled over by wind and currents in freezing conditions and grow into spheroid pieces of ice. They may collect into heaps of ba ...

.

Bering Sea

The Bering Sea ( , ; rus, Бе́рингово мо́ре, r=Béringovo móre, p=ˈbʲerʲɪnɡəvə ˈmorʲe) is a marginal sea of the Northern Pacific Ocean. It forms, along with the Bering Strait, the divide between the two largest landmasse ...

File:Greenland East Coast 7.jpg, Loose drift ice on the east coast of Greenland

File:Jää on kulmunud pallideks (Looduse veidrused). 05.jpg, Ice eggs (diameter 5–10 cm) on Stroomi Beach, Tallinn, Estonia

File:IceNomenclature-2LightPack.jpg, Ice floes in Antarctica, 1919

File:Ridge MOSAiC.jpg, A first-year sea ice ridge in the Central Arctic, photographed by the MOSAiC expedition on July 4, 2020

File:A_Mélange_of_Ice_-_NASA_Earth_Observatory.jpg, Ice mélange on Greenland's western coast, 2012

File:Anchor ice under sea ice.JPG, Anchor ice on the seafloor at McMurdo Sound

The McMurdo Sound is a sound in Antarctica, known as the southernmost passable body of water in the world, located approximately from the South Pole.

Captain James Clark Ross discovered the sound in February 1841 and named it after Lieutenant ...

, Antarctica.

On land

The largest ice formations on Earth are the twoice sheet

In glaciology, an ice sheet, also known as a continental glacier, is a mass of glacier, glacial ice that covers surrounding terrain and is greater than . The only current ice sheets are the Antarctic ice sheet and the Greenland ice sheet. Ice s ...

s which almost completely cover the world's largest island, Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

, and the continent of Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...

. These ice sheets have an average thickness of over and have existed for millions of years.

Other major ice formations on land include ice cap

In glaciology, an ice cap is a mass of ice that covers less than of land area (usually covering a highland area). Larger ice masses covering more than are termed ice sheets.

Description

By definition, ice caps are not constrained by topogra ...

s, ice fields, ice stream

An ice stream is a region of fast-moving ice within an ice sheet. It is a type of glacier, a body of ice that moves under its own weight. They can move upwards of a year, and can be up to in width, and hundreds of kilometers in length. They t ...

s and glacier

A glacier (; or ) is a persistent body of dense ice, a form of rock, that is constantly moving downhill under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires ...

s. In particular, the Hindu Kush

The Hindu Kush is an mountain range in Central Asia, Central and South Asia to the west of the Himalayas. It stretches from central and eastern Afghanistan into northwestern Pakistan and far southeastern Tajikistan. The range forms the wester ...

region is known as the Earth's "Third Pole" due to the large number of glaciers it contains. They cover an area of around , and have a combined volume of between 3,000-4,700 km3. These glaciers are nicknamed "Asian water towers", because their meltwater run-off feeds into rivers which provide water for an estimated two billion people.

Permafrost

Permafrost () is soil or underwater sediment which continuously remains below for two years or more; the oldest permafrost has been continuously frozen for around 700,000 years. Whilst the shallowest permafrost has a vertical extent of below ...

refers to soil

Soil, also commonly referred to as earth, is a mixture of organic matter, minerals, gases, water, and organisms that together support the life of plants and soil organisms. Some scientific definitions distinguish dirt from ''soil'' by re ...

or underwater sediment

Sediment is a solid material that is transported to a new location where it is deposited. It occurs naturally and, through the processes of weathering and erosion, is broken down and subsequently sediment transport, transported by the action of ...

which continuously remains below for two years or more. The ice within permafrost is divided into four categories: pore ice, vein ice (also known as ice wedges), buried surface ice and intrasedimental ice (from the freezing of underground waters). One example of ice formation in permafrost areas is aufeis - layered ice that forms in Arctic and subarctic stream valleys. Ice, frozen in the stream bed, blocks normal groundwater discharge, and causes the local water table to rise, resulting in water discharge on top of the frozen layer. This water then freezes, causing the water table to rise further and repeat the cycle. The result is a stratified ice deposit, often several meters thick. Snow line

The climatic snow line is the boundary between a snow-covered and snow-free surface. The actual snow line may adjust seasonally, and be either significantly higher in elevation, or lower. The permanent snow line is the level above which snow wil ...

and snow fields are two related concepts, in that snow fields accumulate on top of and ablate away to the equilibrium point (the snow line) in an ice deposit.

On rivers and streams

Ice jam

Ice jams occur when the ice that is drifting down-current in a river comes to a stop, for instance, at a river bend, when it contacts the river bed in a shallow area, or against bridge piers. Doing so increases the resistance to flow, thereby in ...

s (sometimes called "ice dams"), when broken chunks of ice pile up, are the greatest ice hazard on rivers. Ice jams can cause flooding, damage structures in or near the river, and damage vessels on the river. Ice jams can cause some hydropower

Hydropower (from Ancient Greek -, "water"), also known as water power or water energy, is the use of falling or fast-running water to Electricity generation, produce electricity or to power machines. This is achieved by energy transformation, ...

industrial facilities to completely shut down. An ice dam is a blockage from the movement of a glacier which may produce a proglacial lake

In geology, a proglacial lake is a lake formed either by the damming action of a moraine during the retreat of a melting glacier, a glacial ice dam, or by meltwater trapped against an ice sheet due to isostatic depression of the crust around t ...

. Heavy ice flows in rivers can also damage vessels and require the use of an icebreaker

An icebreaker is a special-purpose ship or boat designed to move and navigate through ice-covered waters, and provide safe waterways for other boats and ships. Although the term usually refers to ice-breaking ships, it may also refer to smaller ...

vessel to keep navigation possible.

Ice discs are circular formations of ice floating on river water. They form within eddy currents, and their position results in asymmetric melting, which makes them continuously rotate at a low speed.

On lakes

Ice forms on calm water from the shores, a thin layer spreading across the surface, and then downward. Ice on lakes is generally four types: primary, secondary, superimposed and agglomerate. Primary ice forms first. Secondary ice forms below the primary ice in a direction parallel to the direction of the heat flow. Superimposed ice forms on top of the ice surface from rain or water which seeps up through cracks in the ice which often settles when loaded with snow. An

Ice forms on calm water from the shores, a thin layer spreading across the surface, and then downward. Ice on lakes is generally four types: primary, secondary, superimposed and agglomerate. Primary ice forms first. Secondary ice forms below the primary ice in a direction parallel to the direction of the heat flow. Superimposed ice forms on top of the ice surface from rain or water which seeps up through cracks in the ice which often settles when loaded with snow. An ice shove

An ice shove (also known as fast ice, an ice surge, ice push, ice heave, shoreline ice pileup, ice piling, ice thrust, ice tsunami, ice ride-up, or ''ivu'' in Iñupiat) is a surge of ice from an ocean or large lake onto the shore.

Ice shoves are ...

occurs when ice movement, caused by ice expansion and/or wind action, occurs to the extent that ice pushes onto the shores of lakes, often displacing sediment that makes up the shoreline.

Shelf ice is formed when floating pieces of ice are driven by the wind piling up on the windward shore. This kind of ice may contain large air pockets under a thin surface layer, which makes it particularly hazardous to walk across it. Another dangerous form of rotten ice to traverse on foot is candle ice, which develops in columns perpendicular to the surface of a lake. Because it lacks a firm horizontal structure, a person who has fallen through has nothing to hold onto to pull themselves out.

As precipitation

Snow and freezing rain

Snow crystals form when tiny supercooled cloud droplets (about 10

Snow crystals form when tiny supercooled cloud droplets (about 10 μm

The micrometre (Commonwealth English as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; SI symbol: μm) or micrometer (American English), also commonly known by the non-SI term micron, is a unit of length in the International System ...

in diameter) freeze. These droplets are able to remain liquid at temperatures lower than , because to freeze, a few molecules in the droplet need to get together by chance to form an arrangement similar to that in an ice lattice; then the droplet freezes around this "nucleus". Experiments show that this "homogeneous" nucleation of cloud droplets only occurs at temperatures lower than . In warmer clouds an aerosol particle or "ice nucleus" must be present in (or in contact with) the droplet to act as a nucleus. Our understanding of what particles make efficient ice nuclei is poor – what we do know is they are very rare compared to that cloud condensation nuclei on which liquid droplets form. Clays, desert dust and biological particles may be effective, although to what extent is unclear. Artificial nuclei are used in cloud seeding

Cloud seeding is a type of weather modification that aims to change the amount or type of precipitation, mitigate hail, or disperse fog. The usual objective is to increase rain or snow, either for its own sake or to prevent precipitation from ...

. The droplet then grows by condensation of water vapor onto the ice surfaces.

Ice storm

An ice storm, also known as a glaze event or a silver storm, is a type of winter storm characterized by freezing rain. The National Weather Service, U.S. National Weather Service defines an ice storm as a storm which results in the accumulatio ...

is a type of winter storm characterized by freezing rain

Freezing rain is rain maintained at temperatures below melting point, freezing by the ambient air mass that causes freezing on contact with surfaces. Unlike rain and snow mixed, a mixture of rain and snow or ice pellets, freezing rain is made en ...

, which produces a glaze of ice on surfaces, including roads and power line

An overhead power line is a structure used in electric power transmission and Electric power distribution, distribution to transmit electrical energy along large distances. It consists of one or more electrical conductor, conductors (commonly mu ...

s. In the United States, a quarter of winter weather events produce glaze ice, and utilities need to be prepared to minimize damages.

Hard forms

Hail

Hail is a form of solid Precipitation (meteorology), precipitation. It is distinct from ice pellets (American English "sleet"), though the two are often confused. It consists of balls or irregular lumps of ice, each of which is called a hailsto ...

forms in storm cloud

In meteorology, a cloud is an aerosol consisting of a visible mass of miniature liquid droplets, frozen crystals, or other particles, suspended in the atmosphere of a planetary body or similar space. Water or various other chemicals may ...

s when supercooled

Supercooling, also known as undercooling, is the process of lowering the temperature of a liquid below its freezing point without it becoming a solid. Per the established international definition, supercooling means ''‘cooling a substance be ...

water droplets freeze on contact with condensation nuclei, such as dust

Dust is made of particle size, fine particles of solid matter. On Earth, it generally consists of particles in the atmosphere that come from various sources such as soil lifted by wind (an aeolian processes, aeolian process), Types of volcan ...

or dirt

Dirt is any matter considered unclean, especially when in contact with a person's clothes, skin, or possessions. In such cases, they are said to become dirty.

Common types of dirt include:

* Debris: scattered pieces of waste or remains

* Du ...

. The storm's updraft

In meteorology, an updraft (British English: ''up-draught'') is a small-scale air current, current of rising air, often within a cloud.

Overview

Vertical drafts, known as updrafts or downdrafts, are localized regions of warm or cool air that mov ...

blows the hailstones to the upper part of the cloud. The updraft dissipates and the hailstones fall down, back into the updraft, and are lifted up again. Hail has a diameter of or more. Within METAR

METAR is a format for reporting weather information. A METAR weather report is predominantly used by aircraft pilots, and by meteorologists, who use aggregated METAR information to assist in weather forecasting.

Raw METAR is highly standardize ...

code, GR is used to indicate larger hail, of a diameter of at least and GS for smaller. Stones of , and are the most frequently reported hail sizes in North America. Hailstones can grow to and weigh more than . In large hailstones, latent heat

Latent heat (also known as latent energy or heat of transformation) is energy released or absorbed, by a body or a thermodynamic system, during a constant-temperature process—usually a first-order phase transition, like melting or condensation. ...

released by further freezing may melt the outer shell of the hailstone. The hailstone then may undergo 'wet growth', where the liquid outer shell collects other smaller hailstones. The hailstone gains an ice layer and grows increasingly larger with each ascent. Once a hailstone becomes too heavy to be supported by the storm's updraft, it falls from the cloud.

Hail forms in strong thunderstorm

A thunderstorm, also known as an electrical storm or a lightning storm, is a storm characterized by the presence of lightning and its acoustics, acoustic effect on the Earth's atmosphere, known as thunder. Relatively weak thunderstorm ...

clouds, particularly those with intense updrafts, high liquid water content, great vertical extent, large water droplets, and where a good portion of the cloud layer is below freezing . Hail-producing clouds are often identifiable by their green coloration. The growth rate is maximized at about , and becomes vanishingly small much below as supercooled water droplets become rare. For this reason, hail is most common within continental interiors of the mid-latitudes, as hail formation is considerably more likely when the freezing level is below the altitude of . Entrainment

Entrainment may refer to:

* Air entrainment, the intentional creation of tiny air bubbles in concrete

* Brainwave entrainment, the practice of entraining one's brainwaves to a desired frequency

* Entrainment (biomusicology), the synchronization o ...

of dry air into strong thunderstorms over continents can increase the frequency of hail by promoting evaporative cooling which lowers the freezing level of thunderstorm clouds giving hail a larger volume to grow in. Accordingly, hail is actually less common in the tropics despite a much higher frequency of thunderstorms than in the mid-latitudes because the atmosphere

An atmosphere () is a layer of gases that envelop an astronomical object, held in place by the gravity of the object. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A stellar atmosph ...

over the tropics tends to be warmer over a much greater depth. Hail in the tropics occurs mainly at higher elevations.

Ice pellets (

Ice pellets (METAR

METAR is a format for reporting weather information. A METAR weather report is predominantly used by aircraft pilots, and by meteorologists, who use aggregated METAR information to assist in weather forecasting.

Raw METAR is highly standardize ...

code ''PL'') are a form of precipitation consisting of small, translucent

In the field of optics, transparency (also called pellucidity or diaphaneity) is the physical property of allowing light to pass through the material without appreciable light scattering by particles, scattering of light. On a macroscopic scale ...

balls of ice, which are usually smaller than hailstones. This form of precipitation is also referred to as "sleet" by the United States National Weather Service

The National Weather Service (NWS) is an Government agency, agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government that is tasked with providing weather forecasts, warnings of hazardous weather, and other weathe ...

. (In British English

British English is the set of Variety (linguistics), varieties of the English language native to the United Kingdom, especially Great Britain. More narrowly, it can refer specifically to the English language in England, or, more broadly, to ...

"sleet" refers to a mixture of rain and snow.) Ice pellets typically form alongside freezing rain, when a wet warm front

Warm, WARM, or Warmth may refer to:

* A somewhat high temperature; heat

* Kindness

Music Albums

* ''Warm'' (Herb Alpert album), 1969

* ''Warm'' (Jeff Tweedy album), 2018

* ''Warm'' (Johnny Mathis album), 1958, and the title song

* ''Warm'' ( ...

ends up between colder and drier atmospheric layers. There, raindrops would both freeze and shrink in size due to evaporative cooling. So-called snow pellets, or graupel

Graupel (; ), also called soft hail or hominy snow or granular snow or snow pellets, is precipitation that forms when supercooled water droplets in air are collected and freeze on falling snowflakes, forming balls of crisp, opaque rime.

Gra ...

, form when multiple water droplets freeze onto snowflakes until a soft ball-like shape is formed. So-called "diamond dust

Diamond dust is a ground-level cloud composed of tiny ice crystals. This meteorological phenomenon is also referred to simply as '' ice crystals'' and is reported in the METAR code as IC. Diamond dust generally forms under otherwise clear or ...

", (METAR code ''IC'') also known as ice needles or ice crystals, forms at temperatures approaching due to air with slightly higher moisture from aloft mixing with colder, surface-based air.

On surfaces

As water drips and re-freezes, it can form hangingicicle

An icicle is a spike of ice formed when water falling from an object freezes. Formation and dynamics

Icicles can form during bright, sunny, but subfreezing weather, when ice or snow melted by sunlight or some other heat source (such as a poor ...

s, or stalagmite

A stalagmite (, ; ; )

is a type of rock formation that rises from the floor of a cave due to the accumulation of material deposited on the floor from ceiling drippings. Stalagmites are typically composed of calcium carbonate, but may consist ...

-like structures on the ground. On sloped roofs, buildup of ice can produce an ice dam, which stops melt water from draining properly and potentially leads to damaging leaks. More generally, water vapor

Water vapor, water vapour, or aqueous vapor is the gaseous phase of Properties of water, water. It is one Phase (matter), state of water within the hydrosphere. Water vapor can be produced from the evaporation or boiling of liquid water or from th ...

depositing onto surfaces due to high relative humidity

Humidity is the concentration of water vapor present in the air. Water vapor, the gaseous state of water, is generally invisible to the human eye. Humidity indicates the likelihood for precipitation (meteorology), precipitation, dew, or fog t ...

and then freezing results in various forms of atmospheric icing

Atmospheric icing occurs in the atmosphere when water droplets suspended in air freeze on objects they come in contact with. It is not the same as freezing rain, which is caused directly by precipitation.

Atmospheric icing occurs on aircraft, ...

, or frost

Frost is a thin layer of ice on a solid surface, which forms from water vapor that deposits onto a freezing surface. Frost forms when the air contains more water vapor than it can normally hold at a specific temperature. The process is simila ...

. Inside buildings, this can be seen as ice on the surface of un-insulated windows. Hoar frost is common in the environment, particularly in the low-lying areas such as valley

A valley is an elongated low area often running between hills or mountains and typically containing a river or stream running from one end to the other. Most valleys are formed by erosion of the land surface by rivers or streams over ...

s. In Antarctica, the temperatures can be so low that electrostatic attraction

Coulomb's inverse-square law, or simply Coulomb's law, is an experimental law of physics that calculates the amount of force between two electrically charged particles at rest. This electric force is conventionally called the ''electrostatic f ...

is increased to the point hoarfrost on snow sticks together when blown by wind into tumbleweed

A tumbleweed is a structural part of the above-ground anatomy of a number of species of plants. It is a diaspore that, once mature and dry, detaches from its root or stem and rolls due to the force of the wind. In most such species, the tumbl ...

-like balls known as yukimarimo.

Sometimes, drops of water crystallize on cold objects as rime instead of glaze. Soft rime has a density between a quarter and two thirds that of pure ice, due to a high proportion of trapped air, which also makes soft rime appear white. Hard rime is denser, more transparent, and more likely to appear on ships and aircraft. Cold wind specifically causes what is known as ''advection frost'' when it collides with objects. When it occurs on plants, it often causes damage to them. Various methods exist to protect agricultural crops from frost - from simply covering them to using wind machines. In recent decades, irrigation sprinkler

An irrigation sprinkler (also known as a water sprinkler or simply a sprinkler) is a device used to irrigate (water) agricultural crops, lawns, landscapes, golf courses, and other areas. They are also used for cooling and for the control of airb ...

s have been calibrated to spray just enough water to preemptively create a layer of ice that would form slowly and so avoid a sudden temperature shock to the plant, and not be so thick as to cause damage with its weight.

North Rhine-Westphalia

North Rhine-Westphalia or North-Rhine/Westphalia, commonly shortened to NRW, is a States of Germany, state () in Old states of Germany, Western Germany. With more than 18 million inhabitants, it is the List of German states by population, most ...

, Germany

File:Frostweb.jpg, A spiderweb

A spider web, spiderweb, spider's web, or cobweb (from the archaic word ''Wikt:coppe, coppe'', meaning 'spider') is a structure created by a spider out of proteinaceous spider silk extruded from its spinnerets, generally meant to catch its prey ...

covered in frost

File:Icy Japanese Maple branch, Boxborough, Massachusetts, 2008.jpg, Ice on deciduous tree after freezing rain

File:Ice on stairway, 1968 (32085554416).jpg, Icicles on a stairway

A stairwell or stair room is a room in a building where a stair is located, and is used to connect walkways between floors so that one can move in height. Collectively, a set of stairs and a stairwell is referred to as a staircase or stairway. ...

in Seattle

Seattle ( ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Washington and in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. With a population of 780,995 in 2024, it is the 18th-most populous city in the United States. The city is the cou ...

, 1968

File:WindowFrostNewmarketOntario1986.jpg, Fern frost on a window

File:HoarFrost.jpg, Hoar frost atop snow

File:Yukimarimo south pole dawn 2009.jpg, Yukimarimo at South Pole Station

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

, Antarctica, in 2008

Ablation

Ablation of ice refers to both itsmelting

Melting, or fusion, is a physical process that results in the phase transition of a substance from a solid to a liquid. This occurs when the internal energy of the solid increases, typically by the application of heat or pressure, which inc ...

and its dissolution.

The melting of ice entails the breaking of hydrogen bonds

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (H-bond) is a specific type of molecular interaction that exhibits partial covalent character and cannot be described as a purely electrostatic force. It occurs when a hydrogen (H) atom, covalently bonded to a mo ...

between the water molecules. The ordering of the molecules in the solid breaks down to a less ordered state and the solid melts to become a liquid. This is achieved by increasing the internal energy of the ice beyond the melting point

The melting point (or, rarely, liquefaction point) of a substance is the temperature at which it changes state of matter, state from solid to liquid. At the melting point the solid and liquid phase (matter), phase exist in Thermodynamic equilib ...

. When ice melts it absorbs as much energy as would be required to heat an equivalent amount of water by 80 °C. While melting, the temperature of the ice surface remains constant at 0 °C. The rate of the melting process depends on the efficiency of the energy exchange process. An ice surface in fresh water

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salt (chemistry), salts and other total dissolved solids. The term excludes seawater and brackish water, but it does include ...

melts solely by free convection with a rate that depends linearly on the water temperature, ''T''∞, when ''T''∞ is less than 3.98 °C, and superlinearly when ''T''∞ is equal to or greater than 3.98 °C, with the rate being proportional to (T∞ − 3.98 °C)''α'', with ''α'' = for ''T''∞ much greater than 8 °C, and α = for in between temperatures ''T''∞.

In salty ambient conditions, dissolution rather than melting often causes the ablation of ice. For example, the temperature of the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five oceanic divisions. It spans an area of approximately and is the coldest of the world's oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, ...

is generally below the melting point of ablating sea ice. The phase transition from solid to liquid is achieved by mixing salt

In common usage, salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl). When used in food, especially in granulated form, it is more formally called table salt. In the form of a natural crystalline mineral, salt is also known as r ...

and water molecules, similar to the dissolution of sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecul ...

in water, even though the water temperature is far below the melting point of the sugar. However, the dissolution rate is limited by salt concentration and is therefore slower than melting.

Role in human activities

Cooling

Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

engineers had already developed techniques for ice storage in the desert through the summer months. During the winter, ice was transported from harvesting pools and nearby mountains in large quantities to be stored in specially designed, naturally cooled ''refrigerators'', called yakhchal (meaning ''ice storage''). Yakhchals were large underground spaces (up to 5000 m3) that had thick walls (at least two meters at the base) made of a specific type of mortar called '' sarooj'' made from sand, clay, egg whites, lime, goat hair, and ash. The mortar was resistant to heat transfer, helping to keep the ice cool enough not to melt; it was also impenetrable by water. Yakhchals often included a qanat

A qanāt () or kārīz () is a water supply system that was developed in ancient Iran for the purpose of transporting usable water to the surface from an aquifer or a well through an underground aqueduct. Originating approximately 3,000 years ...

and a system of windcatcher

A windcatcher, wind tower, or wind scoop () is a traditional architectural element used to create cross ventilation and passive cooling in buildings. Windcatchers come in various designs, depending on whether local prevailing winds are unidi ...

s that could lower internal temperatures to frigid levels, even during the heat of the summer. One use for the ice was to create chilled treats for royalty.

Harvesting

There were thriving industries in 16th–17th century England whereby low-lying areas along theThames Estuary

The Thames Estuary is where the River Thames meets the waters of the North Sea, in the south-east of Great Britain.

Limits

An estuary can be defined according to different criteria (e.g. tidal, geographical, navigational or in terms of salinit ...

were flooded during the winter, and ice harvested in carts and stored inter-seasonally in insulated wooden houses as a provision to an icehouse often located in large country houses, and widely used to keep fish fresh when caught in distant waters. This was allegedly copied by an Englishman who had seen the same activity in China. Ice was imported into England from Norway on a considerable scale as early as 1823.

In the United States, the first cargo of ice was sent from New York City to Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the List of municipalities in South Carolina, most populous city in the U.S. state of South Carolina. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint of South Carolina's coastline on Charleston Harbor, an inlet of the Atla ...

, in 1799, and by the first half of the 19th century, ice harvesting had become a big business. Frederic Tudor

Frederic Tudor (September 4, 1783 – February 6, 1864) was an American businessman and merchant. Known as Boston's "Ice King", he was the founder of the Tudor Ice Company and a pioneer of the international ice trade in the early 19th century. H ...

, who became known as the "Ice King", worked on developing better insulation products for long distance shipments of ice, especially to the tropics; this became known as the ice trade.

Between 1812 and 1822, under Lloyd Hesketh Bamford Hesketh's instruction, Gwrych Castle was built with 18 large towers, one of those towers is called the 'Ice Tower'. Its sole purpose was to store Ice.

Between 1812 and 1822, under Lloyd Hesketh Bamford Hesketh's instruction, Gwrych Castle was built with 18 large towers, one of those towers is called the 'Ice Tower'. Its sole purpose was to store Ice.

Trieste

Trieste ( , ; ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital and largest city of the Regions of Italy#Autonomous regions with special statute, autonomous region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, as well as of the Province of Trieste, ...

sent ice to Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, Corfu

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

, and Zante

Zakynthos (also spelled Zakinthos; ; ) or Zante (, , ; ; from the Venetian form, traditionally Latinized as Zacynthus) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea. It is the third largest of the Ionian Islands, with an area of , and a coastline in ...

; Switzerland, to France; and Germany sometimes was supplied from Bavaria

Bavaria, officially the Free State of Bavaria, is a States of Germany, state in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the list of German states by area, largest German state by land area, comprising approximately 1/5 of the total l ...

n lakes. From 1930s and up until 1994, the Hungarian Parliament

The National Assembly ( ) is the parliament of Hungary. The unicameral body consists of 199 (386 between 1990 and 2014) members elected to four-year terms. Election of members is done using a semi-proportional representation: a mixed-member ...

building used ice harvested in the winter from Lake Balaton

Lake Balaton () is a freshwater rift lake in the Transdanubian region of Hungary. It is the List of largest lakes of Europe, largest lake in Central Europe, and one of the region's foremost tourist destinations. The Zala River provides the larges ...

for air conditioning.