History of medieval Tunisia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The medieval era of Tunisia began with what would eventually return

*I. ''

*I. ''

Berber, however, no longer is widely spoken in present-day Tunisia; e.g., centuries ago many of its

Berber, however, no longer is widely spoken in present-day Tunisia; e.g., centuries ago many of its

In their medieval Islamic history the Berbers may be divided into three major tribal groups: the Zanata, the

In their medieval Islamic history the Berbers may be divided into three major tribal groups: the Zanata, the

The Zirid dynasty (972–1148) began their rule as agents of the Shi'a

The Zirid dynasty (972–1148) began their rule as agents of the Shi'a

Since their origins with Abu Zakariya the Hafsids had represented their regime as heir to the Almohad movement founded by the Mahdi

Since their origins with Abu Zakariya the Hafsids had represented their regime as heir to the Almohad movement founded by the Mahdi

After an hiatus under the

After an hiatus under the

The Norman kingdom of Africa

{{History of Africa Medieval Islamic world

Ifriqiya

Ifriqiya ( '), also known as al-Maghrib al-Adna (), was a medieval historical region comprising today's Tunisia, eastern Algeria, and Tripolitania (roughly western Libya). It included all of what had previously been the Byzantine province of ...

(Tunisia and the entire Maghrib) to local Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–196 ...

rule. The Shia Islam

Shia Islam is the second-largest Islamic schools and branches, branch of Islam. It holds that Muhammad in Islam, Muhammad designated Ali ibn Abi Talib () as both his political Succession to Muhammad, successor (caliph) and as the spiritual le ...

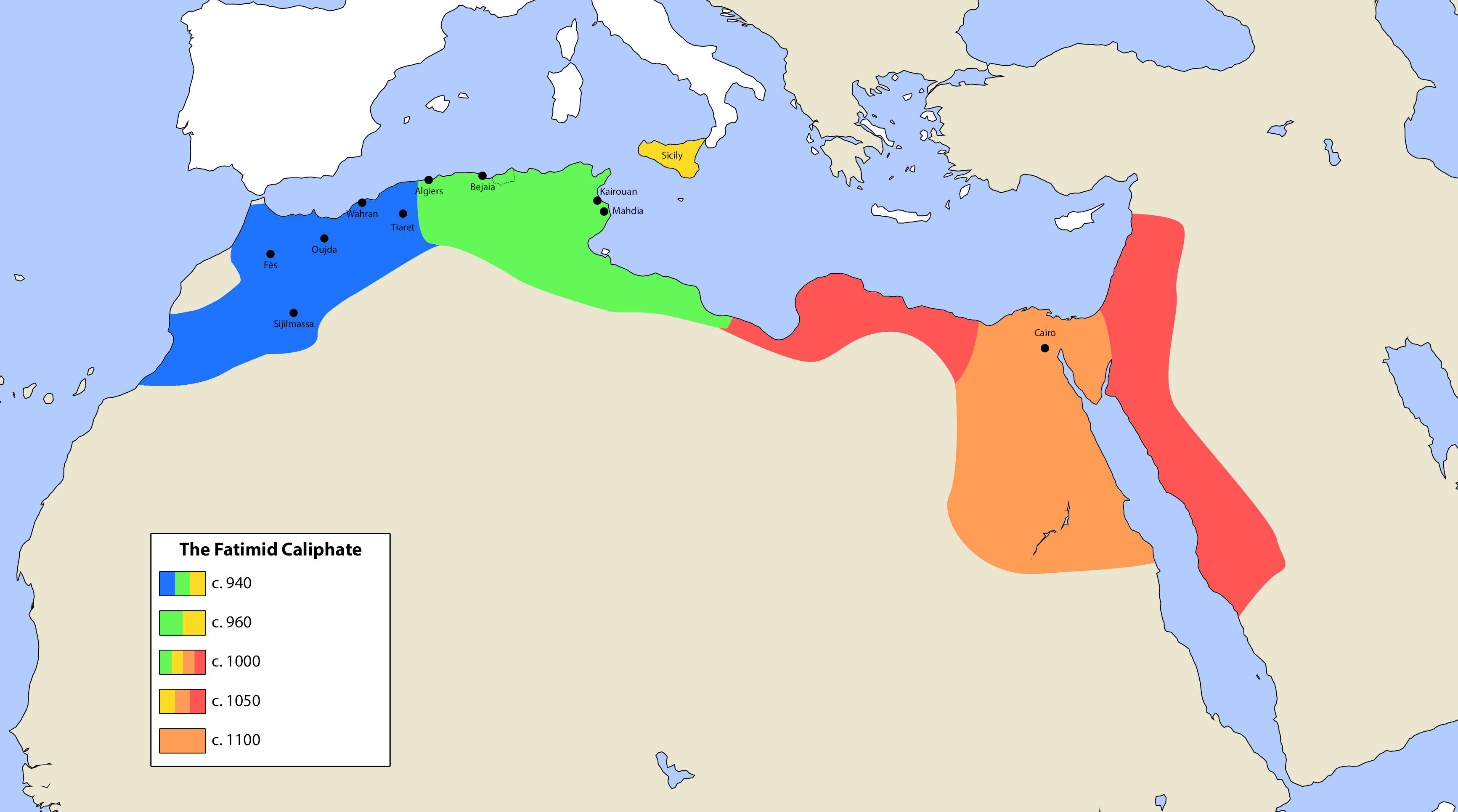

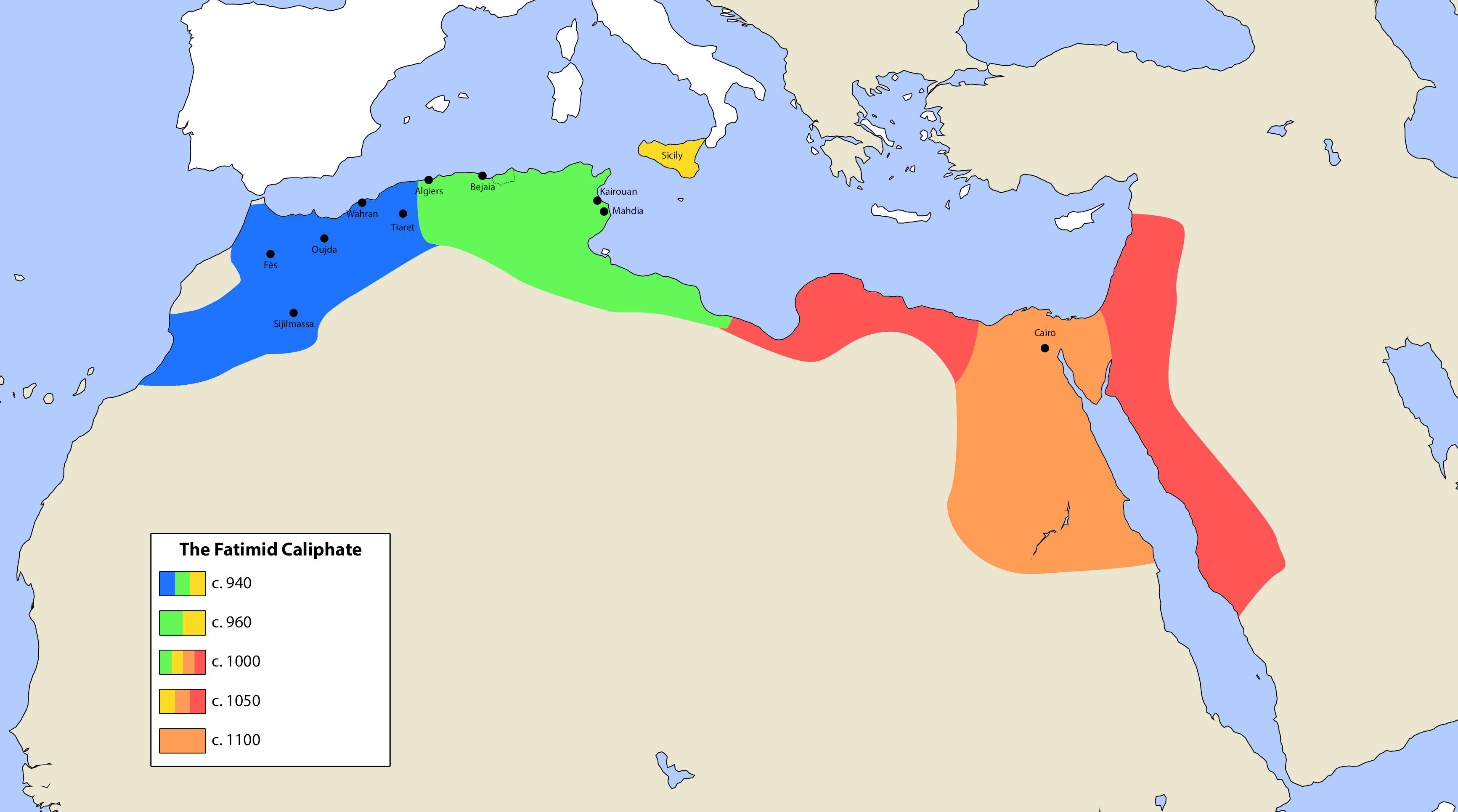

ic Fatimid Caliphate

The Fatimid Caliphate (; ), also known as the Fatimid Empire, was a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries CE under the rule of the Fatimids, an Isma'ili Shi'a dynasty. Spanning a large area of North Africa and West Asia, i ...

departed to their newly conquered territories in Egypt leaving the Zirid dynasty to govern in their stead. The Zirids would eventually break all ties to the Fatimids and formally embrace Sunni Islam

Sunni Islam is the largest Islamic schools and branches, branch of Islam and the largest religious denomination in the world. It holds that Muhammad did not appoint any Succession to Muhammad, successor and that his closest companion Abu Bakr ...

ic doctrines.

During this time there arose in Maghrib two strong local successive movements dedicated to Muslim purity in its practice. The Almoravids emerged in the far western area in al-Maghrib al-Aksa (Morocco) establishing an empire stretching as far north as modern Spain (al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

) and south to Mauretania; Almoravid rule never included Ifriqiya. Later, the Berber religious leader Ibn Tumart

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad Ibn Tūmart (, ca. 1080–1130) was a Muslim religion, religious scholar, teacher and political leader, from the Sous in southern present-day Morocco. He founded and served as the spiritual and first military leader ...

founded the Almohad

The Almohad Caliphate (; or or from ) or Almohad Empire was a North African Berber Muslim empire founded in the 12th century. At its height, it controlled much of the Iberian Peninsula (Al-Andalus) and North Africa (the Maghreb).

The Almohad ...

movement, supplanted the Almoravids, and would eventually bring under the movement's control al-Maghrib and al-Andalus. Almohad rule would be succeeded by the Tunis-based Hafsids

The Hafsid dynasty ( ) was a Sunni Muslim dynasty of Berber descentC. Magbaily Fyle, ''Introduction to the History of African Civilization: Precolonial Africa'', (University Press of America, 1999), 84. that ruled Ifriqiya (modern day Tunisia, w ...

. The Hafsids were a local Berber dynasty and would retain control with varying success until the arrival of the Ottomans in the western Mediterranean.

Berber sovereignty

Following theFatimids

The Fatimid Caliphate (; ), also known as the Fatimid Empire, was a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries CE under the rule of the Fatimid dynasty, Fatimids, an Isma'ili Shi'a dynasty. Spanning a large area of North Africa ...

, for the next half millennium Berber Ifriqiya

Ifriqiya ( '), also known as al-Maghrib al-Adna (), was a medieval historical region comprising today's Tunisia, eastern Algeria, and Tripolitania (roughly western Libya). It included all of what had previously been the Byzantine province of ...

enjoyed self-rule (1048−1574). The Fatimids

The Fatimid Caliphate (; ), also known as the Fatimid Empire, was a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries CE under the rule of the Fatimid dynasty, Fatimids, an Isma'ili Shi'a dynasty. Spanning a large area of North Africa ...

were Shi'a

Shia Islam is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that Muhammad designated Ali ibn Abi Talib () as both his political successor ( caliph) and as the spiritual leader of the Muslim community ( imam). However, his right is understoo ...

, specifically of the more controversial Isma'ili

Ismailism () is a branch of Shia Islam. The Isma'ili () get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma'il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor (Imamate in Nizari doctrine, imām) to Ja'far al-Sadiq, wherein they differ from the ...

branch. They originated in Islamic lands far to the east. Today, and for many centuries, the majority of Tunisians identify as Sunni

Sunni Islam is the largest branch of Islam and the largest religious denomination in the world. It holds that Muhammad did not appoint any successor and that his closest companion Abu Bakr () rightfully succeeded him as the caliph of the Mu ...

(also from the east, but who oppose the Shi'a). In Ifriqiyah, at the time of the Fatimids, there was disdain for any rule from the east regardless if it was Sunni or Shi'a. Hence the rise in medieval Tunisia (Ifriqiya) of regimes not beholden to the east (al-Mashriq), which marks a new and a popular era of Berber sovereignty.

Initially the local agents of the Fatimids managed to inspire the allegiance of Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–196 ...

elements around Ifriqiya by appealing to Berber distrust of the Islamic east, here in the form of Aghlabid

The Aghlabid dynasty () was an Arab dynasty centered in Ifriqiya (roughly present-day Tunisia) from 800 to 909 that conquered parts of Sicily, Southern Italy, and possibly Sardinia, nominally as vassals of the Abbasid Caliphate. The Aghlabids ...

rule. Thus, the Fatimids were ultimately successful in acquiring local state power. Nonetheless, once installed in Ifriqiya, Fatimid rule greatly disrupted social harmony; they imposed high, unorthodox taxes, leading to a Kharijite

The Kharijites (, singular ) were an Islamic sect which emerged during the First Fitna (656–661). The first Kharijites were supporters of Ali who rebelled against his acceptance of arbitration talks to settle the conflict with his challeng ...

revolt. Later, the Fatimids of Ifriqiya managed to accomplish their long-held, grand design for the conquest of Islamic Egypt; soon thereafter their leadership relocated to Cairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

. The Fatimids left the Berber Zirids as their local vassals to govern in the Maghrib. Originally only a client of the Fatimid Shi'a Caliphate in Egypt, the Zirids eventually expelled the Shi'a Fatimids from Ifriqiya. In revenge, the Fatimids sent the disruptive Banu Hilal

The Banu Hilal () was a confederation of Arab tribes from the Najd region of the central Arabian Peninsula that emigrated to the Maghreb region of North Africa in the 11th century. They ruled the Najd, and campaigned in the borderlands between I ...

against Ifriqiya, which led to a period of social chaos and economic decline.

The independent Zirid dynasty has been viewed historically as a Berber kingdom; the Zirids were essentially founded by a leader among the Sanhaja

The Sanhaja (, or زناگة ''Znāga''; , pl. Iẓnagen, and also Aẓnaj, pl. Iẓnajen) were once one of the largest Berbers, Berber tribal confederations, along with the Zenata, Zanata and Masmuda confederations. Many tribes in Algeria, Libya ...

Berbers. Concurrently, the Sunni Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba

A caliphate ( ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with Khalifa, the title of caliph (; , ), a person considered a political–religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of ...

were opposing and battling against the Shi'a Fatimids. Perhaps because Tunisians have long been Sunnis themselves, they may currently evidence faint pride in the Fatimid Caliphate

The Fatimid Caliphate (; ), also known as the Fatimid Empire, was a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries CE under the rule of the Fatimids, an Isma'ili Shi'a dynasty. Spanning a large area of North Africa and West Asia, i ...

's rôle in Islamic history. In addition to their above grievances against the Fatimids (per the Banu Hilal), during the Fatimid era the prestige of cultural leadership within al-Maghrib shifted decisively away from Ifriqiya

Ifriqiya ( '), also known as al-Maghrib al-Adna (), was a medieval historical region comprising today's Tunisia, eastern Algeria, and Tripolitania (roughly western Libya). It included all of what had previously been the Byzantine province of ...

and instead came to be the prize of al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

.

During the interval of generally disagreeable Shi'a rule, the Berber people appear to have ideologically moved away from a popular antagonism against the Islamic east (al-Mashriq), and toward an acquiescence to its Sunni orthodoxy, though of course mediated by their own Maliki

The Maliki school or Malikism is one of the four major madhhab, schools of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas () in the 8th century. In contrast to the Ahl al-Hadith and Ahl al-Ra'y schools of thought, the ...

school of law (viewed as one of the four orthodox madhhab

A ''madhhab'' (, , pl. , ) refers to any school of thought within fiqh, Islamic jurisprudence. The major Sunni Islam, Sunni ''madhhab'' are Hanafi school, Hanafi, Maliki school, Maliki, Shafi'i school, Shafi'i and Hanbali school, Hanbali.

They ...

by the Sunni). Professor Abdallah Laroui remarks that while enjoying sovereignty the Berber Maghrib experimented with several doctrinal viewpoints during the 9th to the 13th centuries, including the Khariji, Zaydi

Zaydism () is a branch of Shia Islam that emerged in the eighth century following Zayd ibn Ali's unsuccessful rebellion against the Umayyad Caliphate. Zaydism is one of the three main branches of Shi'ism, with the other two being Twelverism ...

, Shi'a

Shia Islam is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that Muhammad designated Ali ibn Abi Talib () as both his political successor ( caliph) and as the spiritual leader of the Muslim community ( imam). However, his right is understoo ...

, and Almohad

The Almohad Caliphate (; or or from ) or Almohad Empire was a North African Berber Muslim empire founded in the 12th century. At its height, it controlled much of the Iberian Peninsula (Al-Andalus) and North Africa (the Maghreb).

The Almohad ...

. Eventually they settled on an orthodoxy, on Maliki Sunni doctrines. This progression indicates a grand period of Berber self-definition.

Tunis under the Almohads

The Almohad Caliphate (; or or from ) or Almohad Empire was a North African Berber Muslim empire founded in the 12th century. At its height, it controlled much of the Iberian Peninsula (Al-Andalus) and North Africa (the Maghreb).

The Almohad ...

would become the permanent capital of Ifriqiya. The social discord between Berber and Arab would move toward resolution. In fact it might be said that the history of the Ifriqiya prior to this period was prologue, which merely set the stage; henceforth, the memorable events acted on that stage would come to compose the History of Tunisia for its modern people. Prof. Perkins mentions the preceding history of rule from the east (al-Mashriq), and comments that following the Fatimids departure there arose in Tunisia an intent to establish a "Muslim state geared to the interests of its Berber majority." Thus commenced the medieval era of their sovereignty.

Berber language history

Result of migrations

Twenty or soBerber languages

The Berber languages, also known as the Amazigh languages or Tamazight, are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They comprise a group of closely related but mostly mutually unintelligible languages spoken by Berbers, Berber communities, ...

(also called ''Tamazight'') are spoken in North Africa. Berber speakers were once predominant over all this large area, but as a result of Arabization

Arabization or Arabicization () is a sociology, sociological process of cultural change in which a non-Arab society becomes Arabs, Arab, meaning it either directly adopts or becomes strongly influenced by the Arabic, Arabic language, Arab cultu ...

and later local migrations, today Berber languages are reduced to several large regions (in Morocco, Algeria, and the central Sahara) or remain as smaller language islands.Cf., Joseph R. Applegate, "The Berber Languages" at 96-118, 96-97, in ''Afroasiatic. A Survey'' (1971). Several linguists characterize the Berber spoken as one language with many dialect variations, spread out in discrete regions, without ongoing standardization. The Berber languages may be classified as follows (with some more widely known languages or language groups shown in ''italics''). Ethnic historical correspondence is suggested by the designation , Tribe, .

*I. ''

*I. ''Guanche Guanche may refer to:

*Guanches, the indigenous people of the Canary Islands

*Guanche language, an extinct language, spoken by the Guanches until the 16th or 17th century

*''Conus guanche

''Conus guanche'' is a species of sea snail, a marine ga ...

'' xtinct- (Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; ) or Canaries are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean and the southernmost Autonomous communities of Spain, Autonomous Community of Spain. They are located in the northwest of Africa, with the closest point to the cont ...

).

*II. '' Old Libyan'' xtinct- (West of ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

).

*III. Berber Proper.

**A. Eastern: '' Siwa, Awjila

Awjila (Arabic: أوجلة; Latin: ''Augila'') is an oasis town in the Al Wahat District in the Cyrenaica region of northeastern Libya. Since classical times, it has been known as a place where high-quality dates are farmed. The oasis was ment ...

, Sokna'' - (Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

& Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

).

**B. ''Tuareg

The Tuareg people (; also spelled Twareg or Touareg; endonym, depending on variety: ''Imuhaɣ'', ''Imušaɣ'', ''Imašeɣăn'' or ''Imajeɣăn'') are a large Berber ethnic group, traditionally nomadic pastoralists, who principally inhabit th ...

'' - (Central Sahara

The Sahara (, ) is a desert spanning across North Africa. With an area of , it is the largest hot desert in the world and the list of deserts by area, third-largest desert overall, smaller only than the deserts of Antarctica and the northern Ar ...

region). , Sanhaja,

**C. Western: '' Zenaga'' - (Mauritania

Mauritania, officially the Islamic Republic of Mauritania, is a sovereign country in Maghreb, Northwest Africa. It is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Western Sahara to Mauritania–Western Sahara border, the north and northwest, ...

& Senegal

Senegal, officially the Republic of Senegal, is the westernmost country in West Africa, situated on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. It borders Mauritania to Mauritania–Senegal border, the north, Mali to Mali–Senegal border, the east, Guinea t ...

). , Sanhaja,

**D. Northern Berber languages - ( Maghrib).

***1. Atlas

An atlas is a collection of maps; it is typically a bundle of world map, maps of Earth or of a continent or region of Earth. Advances in astronomy have also resulted in atlases of the celestial sphere or of other planets.

Atlases have traditio ...

: '' Shilha, Central Morocco Tamazight'' - (Morocco

Morocco, officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It has coastlines on the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to Algeria–Morocc ...

& Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

). , Masmuda,

***2. '' Kabyle'' - (East of Algiers

Algiers is the capital city of Algeria as well as the capital of the Algiers Province; it extends over many Communes of Algeria, communes without having its own separate governing body. With 2,988,145 residents in 2008Census 14 April 2008: Offi ...

). , Sanhaja,

***3. '' Zenati'' - (Morocco, Algeria, & Tunisia

Tunisia, officially the Republic of Tunisia, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered by Algeria to the west and southwest, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Tunisia also shares m ...

). , Zenata,

''Nota Bene'': The classification and nomenclature of Berber languages lack complete consensus.

Script, writings

The Libyan Berbers developed their own writing system, evidently derived from Phoenician, as early as the 4th century BC. It was a ''boustrophic'' script, i.e., written left to right then right to left on alternating lines, or up and down in columns. Most of these early inscriptions were funerary and short in length. Several longer texts exist, taken from Thugga, modern Dougga, Tunisia. Both are bilingual, being written in Punic with its letters and in Berber with its letters. One throws some light on the governing institutions of the Berbers in the 2nd century BC. The other text begins: "This temple the citizens of Thugga built for KingMasinissa

Masinissa (''c.'' 238 BC – 148 BC), also spelled Massinissa, Massena and Massan, was an ancient Numidian king best known for leading a federation of Massylii Berber tribes during the Second Punic War (218–201 BC), ultimately uniting the ...

.... " Today the script descendent from the ancient Libyan remains in use; it is called ''Tifinagh

Tifinagh ( Tuareg Berber language: ; Neo-Tifinagh: ; Berber Latin alphabet: ; ) is a script used to write the Berber languages. Tifinagh is descended from the ancient Libyco-Berber alphabet. The traditional Tifinagh, sometimes called Tuareg Tifi ...

''.

Zenata

The Zenata (; ) are a group of Berber tribes, historically one of the largest Berber confederations along with the Sanhaja and Masmuda. Their lifestyle was either nomadic or semi-nomadic.

Society

The 14th-century historiographer Ibn Khaldun repo ...

Berbers became Arabized. Today in Tunisia the small minority that speaks Berber may be heard on Jerba island, around the salt lakes

A salt lake or saline lake is a landlocked body of water that has a concentration of salts (typically sodium chloride) and other dissolved minerals significantly higher than most lakes (often defined as at least three grams of salt per liter). I ...

region, and near the desert

A desert is a landscape where little precipitation occurs and, consequently, living conditions create unique biomes and ecosystems. The lack of vegetation exposes the unprotected surface of the ground to denudation. About one-third of the la ...

, as well as along the mountainous border with Algeria (across this frontier to the west lies a large region where the Zenati Berber languages and dialects predominate). In contrast, use of Berber is relatively common in Morocco, and also in Algeria, and in the remote central Sahara. Berber poetry endures, as well as a traditional Berber literature.

Berber tribal affiliations

The grand tribal identities of Berber antiquity were said to be theMauri

Mauri (from which derives the English term "Moors") was the Latin designation for the Berber population of Mauretania, located in the west side of North Africa on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, Mauretania Tingitana and Mauretania Caesarien ...

, the Numidians

The Numidians were the Berber population of Numidia (present-day Algeria). The Numidians were originally a semi-nomadic people, they migrated frequently as nomads usually do, but during certain seasons of the year, they would return to the same ...

, and the Gaetulians. The Mauri inhabited the far west (ancient Mauritania, now Morocco and central Algeria). The Numidians were located between the Mauri and the city-state of Carthage. Both had large sedentary populations. The Gaetulians were less settled, with large pastoral

The pastoral genre of literature, art, or music depicts an idealised form of the shepherd's lifestyle – herding livestock around open areas of land according to the seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. The target au ...

elements, and lived in the near south on the margins of the Sahara. The medieval historian of the Maghrib, Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldun (27 May 1332 – 17 March 1406, 732–808 Hijri year, AH) was an Arabs, Arab Islamic scholar, historian, philosopher and sociologist. He is widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest social scientists of the Middle Ages, and cons ...

, is credited or blamed for theorizing a causative dynamic to the different tribal confederacies over time. Issues concerning tribal social-economies and their influence have generated a large literature, which critics say is overblown. Abdallah Laroui discounts the impact of tribes, declaring the subject a form of obfuscation which cloaks suspect colonial ideologies. While Berber tribal society has made an impact on culture and government, their continuance was chiefly due to strong foreign interference which usurped the primary domain of the government institutions, and derailed their natural political development. Rather than there being a predisposition for tribal structures, the Berber's survival strategy in the face of foreign occupation was to figuratively retreat into their own way of life through their enduring tribal networks. On the other hand, as it is accepted and understood, tribal societies in the Middle East have continued over millennia and from time to time flourish.

Berber tribal identities survived undiminished during the long period of dominance by the city-state of Carthage. Under centuries of Roman rule also tribal ways were maintained. The sustaining social customs would include: communal self-defense and group liability, marriage alliances, collective religious practices, reciprocal gift-giving, family working relationships and wealth. Abdallah Laroui summarizes the abiding results under foreign rule (here, by Carthage and by Rome) as: Social (assimilated, nonassimilated, free); Geographical (city, country, desert); Economic (commerce, agriculture, nomadism

Nomads are communities without fixed habitation who regularly move to and from areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, Nomadic pastoralism, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and Merchant, trader nomads. In the twentieth century, ...

); and, Linguistic (e.g., Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, Punico-Berber, Berber).

During the initial centuries of the Islamic era, it was said that the Berbers tribes were divided into two blocs, the Butr (Zanata and allies) and the Baranis (Sanhaja, Masmuda, and others). The etymology

Etymology ( ) is the study of the origin and evolution of words—including their constituent units of sound and meaning—across time. In the 21st century a subfield within linguistics, etymology has become a more rigorously scientific study. ...

is unclear, perhaps deriving from tribal customs for clothing ("abtar" and "burnous"), or perhaps words coined to distinguish the nomad (Butr) from the farmer (Baranis). The Arabs drew most of their early recruits from the Butr. Later, legends arose which spoke of an obscure, ancient invasion of North Africa by the Himyarite

Himyar was a polity in the southern highlands of Yemen, as well as the name of the region which it claimed. Until 110 BCE, it was integrated into the Qataban, Qatabanian kingdom, afterwards being recognized as an independent kingdom. According ...

Arabs of Yemen

Yemen, officially the Republic of Yemen, is a country in West Asia. Located in South Arabia, southern Arabia, it borders Saudi Arabia to Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, the north, Oman to Oman–Yemen border, the northeast, the south-eastern part ...

, from which a prehistoric ancestry

An ancestor, also known as a forefather, fore-elder, or a forebear, is a parent or ( recursively) the parent of an antecedent (i.e., a grandparent, great-grandparent, great-great-grandparent and so forth). ''Ancestor'' is "any person from ...

was evidently fabricated: Berber descent from two brothers, Burnus and Abtar, who were sons of Barr, the grandson of Canaan

CanaanThe current scholarly edition of the Septuagint, Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus Testamentum graece iuxta LXX interprets. 2. ed. / recogn. et emendavit Robert Hanhart. Stuttgart : D ...

(Canaan

CanaanThe current scholarly edition of the Septuagint, Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus Testamentum graece iuxta LXX interprets. 2. ed. / recogn. et emendavit Robert Hanhart. Stuttgart : D ...

being the grandson of Noah

Noah (; , also Noach) appears as the last of the Antediluvian Patriarchs (Bible), patriarchs in the traditions of Abrahamic religions. His story appears in the Hebrew Bible (Book of Genesis, chapters 5–9), the Quran and Baháʼí literature, ...

through his son Ham

Ham is pork from a leg cut that has been preserved by wet or dry curing, with or without smoking."Bacon: Bacon and Ham Curing" in '' Chambers's Encyclopædia''. London: George Newnes, 1961, Vol. 2, p. 39. As a processed meat, the term '' ...

). Both Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldun (27 May 1332 – 17 March 1406, 732–808 Hijri year, AH) was an Arabs, Arab Islamic scholar, historian, philosopher and sociologist. He is widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest social scientists of the Middle Ages, and cons ...

(1332–1406) and Ibn Hazm

Ibn Hazm (; November 994 – 15 August 1064) was an Andalusian Muslim polymath, historian, traditionist, jurist, philosopher, and theologian, born in the Córdoban Caliphate, present-day Spain. Described as one of the strictest hadith interpre ...

(994–1064) as well as Berber genealogists

Genealogy () is the study of families, family history, and the tracing of their lineages. Genealogists use oral interviews, historical records, genetic analysis, and other records to obtain information about a family and to demonstrate kins ...

held that the Himyarite Arab ancestry was totally unacceptable. This legendary ancestry, however, played a rôle in the long Arabization

Arabization or Arabicization () is a sociology, sociological process of cultural change in which a non-Arab society becomes Arabs, Arab, meaning it either directly adopts or becomes strongly influenced by the Arabic, Arabic language, Arab cultu ...

process that continued for centuries among the Berber peoples.

In their medieval Islamic history the Berbers may be divided into three major tribal groups: the Zanata, the

In their medieval Islamic history the Berbers may be divided into three major tribal groups: the Zanata, the Sanhaja

The Sanhaja (, or زناگة ''Znāga''; , pl. Iẓnagen, and also Aẓnaj, pl. Iẓnajen) were once one of the largest Berbers, Berber tribal confederations, along with the Zenata, Zanata and Masmuda confederations. Many tribes in Algeria, Libya ...

, and the Masmuda

The Masmuda (, Berber: ⵉⵎⵙⵎⵓⴷⵏ) is a Berber tribal confederation , one of the largest in the Maghreb, along with the Zenata and the Sanhaja. Today, the Masmuda confederacy largely corresponds to the speakers of the Tashelhit lan ...

. These tribal divisions are mentioned by Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406). The Zanata early on allied more closely with the Arabs and consequently became more Arabized, although Znatiya Berber is still spoken in small islands across Algeria and in northern Morocco (the Rif

The Rif (, ), also called Rif Mountains, is a geographic region in northern Morocco. It is bordered on the north by the Mediterranean Sea and Spain and on the west by the Atlantic Ocean, and is the homeland of the Rifians and the Jebala people ...

and north Middle Atlas). The Sanhaja are also widely dispersed throughout the Maghrib, among which are: the sedentary Kabyle on the coast west of modern Algiers

Algiers is the capital city of Algeria as well as the capital of the Algiers Province; it extends over many Communes of Algeria, communes without having its own separate governing body. With 2,988,145 residents in 2008Census 14 April 2008: Offi ...

, the nomadic Zanaga of southern Morocco (the south Anti-Atlas) and the western Sahara to Senegal

Senegal, officially the Republic of Senegal, is the westernmost country in West Africa, situated on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. It borders Mauritania to Mauritania–Senegal border, the north, Mali to Mali–Senegal border, the east, Guinea t ...

, and the Tuareg

The Tuareg people (; also spelled Twareg or Touareg; endonym, depending on variety: ''Imuhaɣ'', ''Imušaɣ'', ''Imašeɣăn'' or ''Imajeɣăn'') are a large Berber ethnic group, traditionally nomadic pastoralists, who principally inhabit th ...

(al-Tawarik), the well-known camel breeding nomads of the central Sahara

The Sahara (, ) is a desert spanning across North Africa. With an area of , it is the largest hot desert in the world and the list of deserts by area, third-largest desert overall, smaller only than the deserts of Antarctica and the northern Ar ...

. The descendants of the Masmuda are sedentary Berbers of Morocco, in the High Atlas, and from Rabat

Rabat (, also , ; ) is the Capital (political), capital city of Morocco and the List of cities in Morocco, country's seventh-largest city with an urban population of approximately 580,000 (2014) and a metropolitan population of over 1.2 million. ...

inland to Azru and Khanifra, the most populous of the modern Berber regions.Generally, Jamil M. Abun-Nasr, ''A History of the Maghrib'' (Cambridge Univ. 1971) at 8-9.Brett and Fentress, ''The Berbers'' (1996) at 131-132.

Medieval events in Ifriqiya

Ifriqiya ( '), also known as al-Maghrib al-Adna (), was a medieval historical region comprising today's Tunisia, eastern Algeria, and Tripolitania (roughly western Libya). It included all of what had previously been the Byzantine province of ...

and al-Maghrib often have tribal associations. Linked to the Kabyle ''Sanhaja'' were the Kutama

The Kutama (Berber: ''Ikutamen''; ) were a Berber tribe in northern Algeria classified among the Berber confederation of the Bavares. The Kutama are attested much earlier, in the form ''Koidamousii'' by the Greek geographer Ptolemy.

The Kutama p ...

tribes, whose support worked to establish the Fatimid Caliphate

The Fatimid Caliphate (; ), also known as the Fatimid Empire, was a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries CE under the rule of the Fatimids, an Isma'ili Shi'a dynasty. Spanning a large area of North Africa and West Asia, i ...

(909–1171, only until 1049 in Ifriqiya); their vassals and later successors in Ifriqiya the Zirids

The Zirid dynasty (), Banu Ziri (), was a Sanhaja Berber dynasty from what is now Algeria which ruled the central Maghreb from 972 to 1014 and Ifriqiya (eastern Maghreb) from 972 to 1148.

Descendants of Ziri ibn Manad, a military leader of th ...

(973–1160) were also ''Sanhaja''. The Almoravids

The Almoravid dynasty () was a Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire that stretched over the western Maghreb and Al-Andalus, starting in the 1050s and lasting until its fall to the Almo ...

(1056–1147) first began far south of Morocco, among the Lamtuna ''Sanhaja''. From the ''Masmuda'' came Ibn Tumart

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad Ibn Tūmart (, ca. 1080–1130) was a Muslim religion, religious scholar, teacher and political leader, from the Sous in southern present-day Morocco. He founded and served as the spiritual and first military leader ...

and the Almohad movement (1130–1269), later supported by the ''Sanhaja''. Accordingly, it was from among the ''Masmuda'' that the Hafsid dynasty

The Hafsid dynasty ( ) was a Sunni Muslim dynasty of Berbers, Berber descentC. Magbaily Fyle, ''Introduction to the History of African Civilization: Precolonial Africa'', (University Press of America, 1999), 84. that ruled Ifriqiya (modern day Tu ...

(1227–1574) of Tunis

Tunis (, ') is the capital city, capital and largest city of Tunisia. The greater metropolitan area of Tunis, often referred to as "Grand Tunis", has about 2,700,000 inhabitants. , it is the third-largest city in the Maghreb region (after Casabl ...

originated.

Zirid Berber succession

Under the Fatimids

The Zirid dynasty (972–1148) began their rule as agents of the Shi'a

The Zirid dynasty (972–1148) began their rule as agents of the Shi'a Fatimids

The Fatimid Caliphate (; ), also known as the Fatimid Empire, was a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries CE under the rule of the Fatimid dynasty, Fatimids, an Isma'ili Shi'a dynasty. Spanning a large area of North Africa ...

(909−1171), who had conquered Egypt in 969. After removing their capital to Cairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

from Mahdiya in Ifriqiya, the Fatimids also withdrew from direct governance of al-Maghrib, which they delegated to a local vassal. Their Maghriban power, however, was not transferred to a loyal Kotama Berber, which tribe had provided crucial support to the Fatimids during their rise. Instead authority was given to a chief from among the Sanhaja

The Sanhaja (, or زناگة ''Znāga''; , pl. Iẓnagen, and also Aẓnaj, pl. Iẓnajen) were once one of the largest Berbers, Berber tribal confederations, along with the Zenata, Zanata and Masmuda confederations. Many tribes in Algeria, Libya ...

Berber confederacy of the central Magrib, Buluggin ibn Ziri (died 984). His father Ziri had been a loyal follower and soldier of the Fatimids.

For a time the region enjoyed great prosperity and the early Zirid court famously enjoyed luxury and the arts. Yet political affairs were turbulent. Bologguin's war against the Zenata

The Zenata (; ) are a group of Berber tribes, historically one of the largest Berber confederations along with the Sanhaja and Masmuda. Their lifestyle was either nomadic or semi-nomadic.

Society

The 14th-century historiographer Ibn Khaldun repo ...

Berbers to the west was fruitless. His son al-Mansur (r. 984–996) challenged rule by the Fatimid Shi'a Caliphate in Cairo, but without his intended effect; instead, the Kotama Berbers were inspired by the Fatimids to rebel; al-Manur did manage to subdue the Kotama. The Fatimids continued to demand tribute payments from the Zirids. After Buluggin's death, the Fatamid vassalage had eventually been split among two dynasties: for Ifriqiya the Zirid (972−1148); and for western lands n present-day Algeriathe Hammadid (1015–1152), named for Hammad, another descendant of Buluggin. The security of civic life declined, due largely to intermittent political quarrels between the Zirids and the Hammadids, including a civil war ending in 1016. Armed attacks also came from the Sunni

Sunni Islam is the largest branch of Islam and the largest religious denomination in the world. It holds that Muhammad did not appoint any successor and that his closest companion Abu Bakr () rightfully succeeded him as the caliph of the Mu ...

Umayyads of al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

and from the other Berbers, e.g., the Zanatas of Morocco.

Even though in this period the Maghrib often fell into conflict, becoming submerged in political confusion, the Fatimid province of Ifriqiya at first managed to continue in relative prosperity under the Zirid Berbers. Agriculture thrived (grains and olives), as did the artisans of the city (weavers, metalworkers, potters), and the Saharan trade,. The holy city of Kairouan

Kairouan (, ), also spelled El Qayrawān or Kairwan ( , ), is the capital of the Kairouan Governorate in Tunisia and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The city was founded by the Umayyads around 670, in the period of Caliph Mu'awiya (reigned 661� ...

served also as the chief political and cultural center of the Zirid state. Soon however the Saharan trade began to decline, caused by changing demand, and by the encroachments of rival traders: from Fatimid Egypt to the east, and from the rising power of the al-Murabit Berber movement in Morocco to the west. This decline in the Saharan trade caused a rapid deterioration in the commercial well-being of Kairouan. To compensate, the Zirids encouraged the sea trade of their coastal cities, which did begin to quicken; however, they faced rigorous competition from Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

traders of the rising city-states of Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

and Pisa

Pisa ( ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Tuscany, Central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for the Leaning Tow ...

.

Independence

In 1048, for both economic and popular reasons, the Zirids dramatically broke with theShi'a

Shia Islam is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that Muhammad designated Ali ibn Abi Talib () as both his political successor ( caliph) and as the spiritual leader of the Muslim community ( imam). However, his right is understoo ...

Fatimid Caliphate, who had ruled them from Cairo. Instead the Zirids chose to become Sunni

Sunni Islam is the largest branch of Islam and the largest religious denomination in the world. It holds that Muhammad did not appoint any successor and that his closest companion Abu Bakr () rightfully succeeded him as the caliph of the Mu ...

(always favored by most Maghribi Muslims) and hence declared their allegiance to the moribund Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate or Abbasid Empire (; ) was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib (566–653 CE), from whom the dynasty takes ...

in Baghdad

Baghdad ( or ; , ) is the capital and List of largest cities of Iraq, largest city of Iraq, located along the Tigris in the central part of the country. With a population exceeding 7 million, it ranks among the List of largest cities in the A ...

. Consequently, many shia were killed during disturbances throughout Ifriqiya. The Zirid state seized Fatimid wealth and coinage. Sunni Maliki jurists were reestablished as the prevailing school of law.

In retaliation, the Fatimid political leaders sent against the Zirids an invasion of nomad

Nomads are communities without fixed habitation who regularly move to and from areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the population of nomadic pa ...

ic Arabians, the Banu Hilal, who had already migrated into upper Egypt. These warrior bedouins were induced by the Fatimids to continue westward into Ifriqiya. Ominously, westward toward Zirid Ifriqiya came the entire Banu Hilal, along with them the Banu Sulaym, both Arab tribes quitting upper Egypt where they had been pasturing their animals.

The arriving Bedouin

The Bedouin, Beduin, or Bedu ( ; , singular ) are pastorally nomadic Arab tribes who have historically inhabited the desert regions in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, the Levant, and Mesopotamia (Iraq). The Bedouin originated in the Sy ...

s of the Banu Hilal

The Banu Hilal () was a confederation of Arab tribes from the Najd region of the central Arabian Peninsula that emigrated to the Maghreb region of North Africa in the 11th century. They ruled the Najd, and campaigned in the borderlands between I ...

defeated in battle the Zirid and Hammadid Berber armies in 1057, and sack the Zirid capital Kairouan. It has since been said that much of the Maghrib's misfortunes to follow can be traced to the chaos and regression occasioned by their arrival, although historical opinion is not unanimous. In Arab lore the Banu Hilal's leader Abu Zayd al-Hilali is a hero; he enjoys a victory parade in Tunis where he is made lord of al-Andalus, according to the folk epic Taghribat Bani Hilal. The Banu Hilal came from the tribal confederacy Banu 'Amir, located mostly in southwest Arabia.

In Tunisia as the Banu Hilali tribes looted the rural areas, the local sedentary populace were forced to take refuge in the main coastal cities as well as in fortified towns in northern Tunisia (Such as Tunis, Sfax, Mahdia, Bizerte...). During this time, Tunisia underwent rapid urbanisation as famines depopulated the countryside and industry shifted from agriculture to manufactures. The prosperous agriculture of central and northern Ifriqiya gave way to pastoralism

Pastoralism is a form of animal husbandry where domesticated animals (known as "livestock") are released onto large vegetated outdoor lands (pastures) for grazing, historically by nomadic people who moved around with their herds. The anim ...

for a time; consequently the economic well-being went into steep decline.

Even after the fall of the Zirids, the Banu Hilal were a source of disorder, as in the 1184 insurrection of the Banu Ghaniya The Banu Ghaniya were a Massufa Sanhaja Berber dynasty and a branch of the Almoravids.Arabization

Arabization or Arabicization () is a sociology, sociological process of cultural change in which a non-Arab society becomes Arabs, Arab, meaning it either directly adopts or becomes strongly influenced by the Arabic, Arabic language, Arab cultu ...

. Use of the Berber languages

The Berber languages, also known as the Amazigh languages or Tamazight, are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They comprise a group of closely related but mostly mutually unintelligible languages spoken by Berbers, Berber communities, ...

decreased in rural areas as a result of the Bedouin ascendancy. Substantially weakened, Sanhaja

The Sanhaja (, or زناگة ''Znāga''; , pl. Iẓnagen, and also Aẓnaj, pl. Iẓnajen) were once one of the largest Berbers, Berber tribal confederations, along with the Zenata, Zanata and Masmuda confederations. Many tribes in Algeria, Libya ...

Zirid rule lingered, with civil society disrupted, and the regional economy now in chaos.

Normans in coastal Tunisia

Normans from Sicily raided the east coast of Ifriqiya for the first time in 1123. After some years of attacks, in 1148 Normans under George of Antioch conquered all the coastal cities of Tunisia: Bona (Annaba), Mahdia, Sfax, Gabès, and Tunis. Indeed, the Norman kingRoger II of Sicily

Roger II or Roger the Great (, , Greek language, Greek: Ρογέριος; 22 December 1095 – 26 February 1154) was King of Kingdom of Sicily, Sicily and Kingdom of Africa, Africa, son of Roger I of Sicily and successor to his brother Simon, C ...

was able to create a coastal dominion of the area between Bona and Tripoli that lasted from 1135 to 1160 and was supported mainly by the last local Christian communities.

These communities, usually Christian North African populations ( Roman Africans), holding to their religion since the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

, still spoke the African Romance

African Romance, African Latin or Afroromance is an extinct Romance languages, Romance language that was spoken in the various provinces of Africa (Roman province), Roman Africa by the African Romans under the later Roman Empire and its various ...

in a few places like Gabès

Gabès (, ; ), also spelled Cabès, Cabes, and Kabes, is the capital of the Gabès Governorate in Tunisia. Situated on the coast of the Gulf of Gabès, the city has a population of 167,863, making it the 6th largest city in Tunisia. Located 327 ...

and Gafsa

Gafsa (; ; ') is the capital of Gafsa Governorate in Tunisia. With a population of 120,739, Gafsa is the ninth-largest Tunisian city and is 335 km from the country's capital, Tunis.

Overview

Gafsa is the capital of Gafsa Governorate, in ...

: the most important testimony of the existence of the African Romance comes from the 12th-century Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi

Abu Abdullah Muhammad al-Idrisi al-Qurtubi al-Hasani as-Sabti, or simply al-Idrisi (; ; 1100–1165), was an Arab Muslim geographer and cartographer who served in the court of King Roger II at Palermo, Sicily. Muhammad al-Idrisi was born in C ...

, who wrote that the people of Gafsa (in central-south Tunisia) used a language that he called ''al-latini al-afriqi'' ("the Latin of Africa";).

Berber Islamic movements

In the medieval Maghrib, among the Berber tribes, two strong religious movements arose one after the other: theAlmoravids

The Almoravid dynasty () was a Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire that stretched over the western Maghreb and Al-Andalus, starting in the 1050s and lasting until its fall to the Almo ...

(1056–1147), and the Almohads

The Almohad Caliphate (; or or from ) or Almohad Empire was a North African Berber Muslim empire founded in the 12th century. At its height, it controlled much of the Iberian Peninsula (Al-Andalus) and North Africa (the Maghreb).

The Almohad ...

(1130–1269). Professor Jamil Abun-Nasr compares these movements with the 8th-and-9th-century Kharijites

The Kharijites (, singular ) were an Islamic sect which emerged during the First Fitna (656–661). The first Kharijites were supporters of Ali who rebelled against his acceptance of arbitration talks to settle the conflict with his challeng ...

in the Magrib including Ifriqiya: each a militant Berber movement of strong Muslim faith, each rebellious against a status quo of lax orthodoxy, each seeking to found a state in which "leading the Muslim good life was the professed aim of politics".Abun-Nasr, ''A History of the Maghrib'' (1971) at 119. These medieval Berber movements, the Almoravids and the Almohads, have been compared to the more recent Wahhabi

Wahhabism is an exonym for a Salafi revivalist movement within Sunni Islam named after the 18th-century Hanbali scholar Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. It was initially established in the central Arabian region of Najd and later spread to other ...

s, strict fundamentalists of Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in West Asia. Located in the centre of the Middle East, it covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries ...

.

The Almoravids rabic ''al-Murabitum'', from ''Ribat'', e.g., "defenders"began as an Islamic movement of the Sanhaja

The Sanhaja (, or زناگة ''Znāga''; , pl. Iẓnagen, and also Aẓnaj, pl. Iẓnajen) were once one of the largest Berbers, Berber tribal confederations, along with the Zenata, Zanata and Masmuda confederations. Many tribes in Algeria, Libya ...

Berbers, arising in the remote deserts of the southwest Maghrib. After a century, this movement had run its course, losing its cohesion and strength, thereafter becoming decadent. From their capital Marrakech

Marrakesh or Marrakech (; , ) is the fourth-largest city in Morocco. It is one of the four imperial cities of Morocco and is the capital of the Marrakesh–Safi Regions of Morocco, region. The city lies west of the foothills of the Atlas Mounta ...

the Almoravids had once governed a large empire stretching from Mauritania

Mauritania, officially the Islamic Republic of Mauritania, is a sovereign country in Maghreb, Northwest Africa. It is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Western Sahara to Mauritania–Western Sahara border, the north and northwest, ...

(south of Morocco) to al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

(southern Spain), yet Almoravid rule had never reached east far enough to include Ifriqiya.

The rival Almohads were also a Berber Islamic movement, whose founder was from the Masmuda

The Masmuda (, Berber: ⵉⵎⵙⵎⵓⴷⵏ) is a Berber tribal confederation , one of the largest in the Maghreb, along with the Zenata and the Sanhaja. Today, the Masmuda confederacy largely corresponds to the speakers of the Tashelhit lan ...

tribe. They defeated and supplanted the Amoravids and themselves established a large empire, which embraced the region of Ifriqiya

Ifriqiya ( '), also known as al-Maghrib al-Adna (), was a medieval historical region comprising today's Tunisia, eastern Algeria, and Tripolitania (roughly western Libya). It included all of what had previously been the Byzantine province of ...

, formerly ruled by the Zirids.

Almohads (al-Muwahiddin)

Mahdi of the Unitarians

TheAlmohad

The Almohad Caliphate (; or or from ) or Almohad Empire was a North African Berber Muslim empire founded in the 12th century. At its height, it controlled much of the Iberian Peninsula (Al-Andalus) and North Africa (the Maghreb).

The Almohad ...

movement rabic ''al-Muwahhidun'', "the Unitarians"ruled variously in the Maghrib starting about 1130 until 1248 (locally in Morocco until 1275). This movement had been founded by Ibn Tumart

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad Ibn Tūmart (, ca. 1080–1130) was a Muslim religion, religious scholar, teacher and political leader, from the Sous in southern present-day Morocco. He founded and served as the spiritual and first military leader ...

(1077–1130), a Masmuda

The Masmuda (, Berber: ⵉⵎⵙⵎⵓⴷⵏ) is a Berber tribal confederation , one of the largest in the Maghreb, along with the Zenata and the Sanhaja. Today, the Masmuda confederacy largely corresponds to the speakers of the Tashelhit lan ...

Berber from the Atlas Mountains

The Atlas Mountains are a mountain range in the Maghreb in North Africa. They separate the Sahara Desert from the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean; the name "Atlantic" is derived from the mountain range, which stretches around through M ...

of Morocco, who became the mahdi

The Mahdi () is a figure in Islamic eschatology who is believed to appear at the Eschatology, End of Times to rid the world of evil and injustice. He is said to be a descendant of Muhammad in Islam, Muhammad, and will appear shortly before Jesu ...

. After a pilgrimage to Mecca followed by study, he had returned to the Maghrib about 1218 inspired by the teachings of al-Ash'ari

Abu al-Hasan al-Ash'ari (; 874–936 CE) was an Arab Islamic theology, Muslim theologian known for being the eponymous founder of the Ash'ari school of kalam in Sunnism.

Al-Ash'ari was notable for taking an intermediary position between the two ...

and al-Ghazali

Al-Ghazali ( – 19 December 1111), archaically Latinized as Algazelus, was a Shafi'i Sunni Muslim scholar and polymath. He is known as one of the most prominent and influential jurisconsults, legal theoreticians, muftis, philosophers, the ...

. A charismatic leader, he preached an interior awareness of the Unity of God. A puritan and a hard-edged reformer, he gathered a strict following among the Berbers in the Atlas, founded a radical community, and eventually began an armed challenge to the current rulers, the Almoravids

The Almoravid dynasty () was a Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire that stretched over the western Maghreb and Al-Andalus, starting in the 1050s and lasting until its fall to the Almo ...

(1056–1147).

Ibn Tumart

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad Ibn Tūmart (, ca. 1080–1130) was a Muslim religion, religious scholar, teacher and political leader, from the Sous in southern present-day Morocco. He founded and served as the spiritual and first military leader ...

the Almohad founder left writings in which his theological ideas mix with the political. Therein he claimed that the leader, the mahdi, is infallible. Ibn Tumart created a hierarchy from among his followers which persisted long after the Almohad era (i.e., in Tunisia under the Hafsids

The Hafsid dynasty ( ) was a Sunni Muslim dynasty of Berber descentC. Magbaily Fyle, ''Introduction to the History of African Civilization: Precolonial Africa'', (University Press of America, 1999), 84. that ruled Ifriqiya (modern day Tunisia, w ...

), based not only on a specie of ethnic loyalty, such as the "Council of Fifty" 'ahl al-Khamsin'' and the assembly of "Seventy" 'ahl al-Saqa'' but more significantly based on a formal structure for an inner circle of governance that would transcend tribal loyalties, namely, (a) his ''ahl al-dar'' or "people of the house", a sort of privy council, (b) his ''ahl al-'Ashra'' or the "Ten", originally composed of his first ten forminable followers, and (c) a variety of offices. Ibn Tumart trained his own ''talaba'' or ideologists, as well as his ''huffaz'', who function was both religious and military. There is lack of certainty about some details, but general agreement that Ibn Tumart sought to reduce the "influence of the traditional tribal framework." Later historical developments "were greatly facilitated by his original reorganization because it made possible collaboration among tribes" not likely to otherwise coalesce. These organizing and group solidarity preparations made by Ibn Tumart were "most methodical and efficient" and a "conscious replica" of Medina in the time of Muhammad.

The mahdi Ibn Tumart also had championed the idea of strict Islamic law and morals displacing unorthodox aspects of Berber custom. At his early base at Tinmal, Ibn Tumart functioned as "the custodian of the faith, the arbiter of moral questions, and the chief judge." Yet evidently because of the narrow legalism then common among Maliki

The Maliki school or Malikism is one of the four major madhhab, schools of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas () in the 8th century. In contrast to the Ahl al-Hadith and Ahl al-Ra'y schools of thought, the ...

jurists and because of their influence in the rival Almoravid regime, Ibn Tumart opposed the Maliki school of law favoring instead the Zahiri

The Zahiri school or Zahirism is a school of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was named after Dawud al-Zahiri and flourished in Spain during the Caliphate of Córdoba under the leadership of Ibn Hazm. It was also followed by the majo ...

te school.

Empire of a unified Maghrib

Following the Mahdi Ibn Tumart's death,Abd al-Mu'min

Abd al-Mu'min (c. 1094–1163) (; full name: ʿAbd al-Muʾmin ibn ʿAlī ibn ʿAlwī ibn Yaʿlā al-Kūmī Abū Muḥammad) was a prominent member of the Almohad movement. Although the Almohad movement itself was founded by Ibn Tumart, Abd al-Mu' ...

al-Kumi (c. 1090 – 1163) circa 1130 became the Almohad caliph—the first non-Arab to take such title. Abd al-Mu'min had been one of the original "Ten" followers of Ibn Tumart. He immediately launched attacks on the ruling Almoravid and had wrestled Morocco away from them by 1147, suppressing subsequent revolts there. Then he crossed the straits, occupying al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

(in southern Spain); yet Almohad rule there was uneven and divisive. Abd al-Mu'min spend many years "organizing his state internally with a view to establishing the government of the Almohad state in his family." "Abd al-Mu'min tried to create a unified Muslim community in the Maghrib on the basis of Ibn Tumart's teachings."

Meanwhile, the anarchy in Zirid Ifriqiya (Tunisia) made it a target for the Norman kingdom in Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

, who between 1134 and 1148 had taken control of Mahdia

Mahdia ( ') is a Tunisian coastal city with 76,513 inhabitants, south of Monastir, Tunisia, Monastir and southeast of Sousse.

Mahdia is a provincial centre north of Sfax. It is important for the associated fish-processing industry, as well as w ...

, Gabès

Gabès (, ; ), also spelled Cabès, Cabes, and Kabes, is the capital of the Gabès Governorate in Tunisia. Situated on the coast of the Gulf of Gabès, the city has a population of 167,863, making it the 6th largest city in Tunisia. Located 327 ...

, Sfax

Sfax ( ; , ) is a major port city in Tunisia, located southeast of Tunis. The city, founded in AD849 on the ruins of Taparura, is the capital of the Sfax Governorate (about 955,421 inhabitants in 2014), and a Mediterranean port. Sfax has a ...

, and the island of Jerba, all of which served as centers for commerce and trade. The only strong Muslim power then in the Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ), also known as the Arab Maghreb () and Northwest Africa, is the western part of the Arab world. The region comprises western and central North Africa, including Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, and Tunisia. The Maghreb al ...

was that of the newly emerging Almohads, led by their caliph a Berber Abd al-Mu'min

Abd al-Mu'min (c. 1094–1163) (; full name: ʿAbd al-Muʾmin ibn ʿAlī ibn ʿAlwī ibn Yaʿlā al-Kūmī Abū Muḥammad) was a prominent member of the Almohad movement. Although the Almohad movement itself was founded by Ibn Tumart, Abd al-Mu' ...

. He responded with several military campaigns into the eastern Maghrib which absorbed the Hammaid and Zirid states, and removed the Christians. Thus in 1152 he first attacked and occupied Bougie (in eastern Algeria), ruled by the Sanhaja Hammadids. His armies next entered Zirid Ifriqiya, a disorganized territory, taking Tunis. His armies also besieged Mahdia, held by Normans of Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

, compelling these Christians to negotiate their withdrawal in 1160. Yet Christian merchants, e.g., from Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

and Pisa

Pisa ( ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Tuscany, Central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for the Leaning Tow ...

, had already arrived to stay in Ifriqiya, so that such a foreign merchant presence (Italian and Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and ; ) is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces of Spain, ...

ese) continued.

With the capture of Tunis, Mahdia, and later Tripoli, the Almohad state reached from Morocco to Libya. "This was the first time that the Maghrib became united under one local political authority." "Abd al-Mu'min briefly presided over a unified North African empire--the first and last in its history under indigenous rule". It would be the high point of Maghribi political unity. Yet twenty years later, by 1184, the revolt in the Balearic Islands

The Balearic Islands are an archipelago in the western Mediterranean Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The archipelago forms a Provinces of Spain, province and Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Spain, ...

by the Banu Ghaniya The Banu Ghaniya were a Massufa Sanhaja Berber dynasty and a branch of the Almoravids.fiqh

''Fiqh'' (; ) is the term for Islamic jurisprudence.Fiqh

Encyclopædia Britannica ''Fiqh'' is of ...

of any established school of law. In practice, however, the Maliki school of law survived and by default worked at the margin. Eventually Maliki jurists came to be recognized in some official fashion, except during the reign of Abu Yusuf Ya'qub al-Mansur (1184–1199) who was loyal to Ibn Tumart's teachings. Yet the confused status continued to exist on and off, although at the end for the most part to function poorly. After of century of such oscillation, the caliph Abu al-'Ala Idris al-Ma'mun broke with the narrow ideology of the Almohad regimes (first articulated by the mahdi Ibn Tumart); circa 1230, he affirmed the reinstitution of the then-reviving Malikite rite, perennially popular in al-Maghrib.

The Muslim philosophers Encyclopædia Britannica ''Fiqh'' is of ...

Ibn Tufayl

Ibn Ṭufayl ( – 1185) was an Arab Andalusian Muslim polymath: a writer, Islamic philosopher, Islamic theologian, physician, astronomer, and vizier.

As a philosopher and novelist, he is most famous for writing the first philosophical no ...

(Abubacer to the Latins) of Granada (died 1185), and Ibn Rushd

Ibn Rushd (14 April 112611 December 1198), archaically Latinized as Averroes, was an Arab Muslim polymath and jurist from Al-Andalus who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psychology, math ...

(Averroës) of Córdoba (1126–1198), who was also appointed a Maliki judge, were dignitaries known to the Almohad court, whose capital became fixed at Marrakech

Marrakesh or Marrakech (; , ) is the fourth-largest city in Morocco. It is one of the four imperial cities of Morocco and is the capital of the Marrakesh–Safi Regions of Morocco, region. The city lies west of the foothills of the Atlas Mounta ...

. The Sufi master theologian Ibn 'Arabi

Ibn Arabi (July 1165–November 1240) was an Andalusian Sunni scholar, Sufi mystic, poet, and philosopher who was extremely influential within Islamic thought. Out of the 850 works attributed to him, some 700 are authentic, while over 400 ar ...

was born in Murcia in 1165. Under the Almohads architecture flourished, the Giralda being built in Seville and the pointed arch being introduced.

"There is no better indication of the importance of the Almohad empire than the fascination it has exerted on all subsequent rulers in the Magrib." It was an empire Berber in its inspiration, and whose imperial fortunes were under the direction of Berber leaders. The unitarian Almohads had gradually modified the original ambition of strictly implementing their founder's designs; in this way the Almohads were similar to the preceding Almoravids (also Berber). Yet their movement probably worked to deepen the religious awareness of the Muslim people across the Maghrib. Nonetheless, it could not suppress other traditions and teachings, and alternative expressions of Islam, including the popular cult of saints, the sufis, as well as the Maliki jurists, survived.

The Almohad empire (like its predecessor the Almoravid) eventually weakened and dissolved. Except for the Muslim Kingdom of Granada, Spain was lost. In Morocco, the Almohads were to be followed by the Merinids; in Ifriqiya (Tunisia), by the Hafsids

The Hafsid dynasty ( ) was a Sunni Muslim dynasty of Berber descentC. Magbaily Fyle, ''Introduction to the History of African Civilization: Precolonial Africa'', (University Press of America, 1999), 84. that ruled Ifriqiya (modern day Tunisia, w ...

(who claimed to be the heirs of the unitarian Almohads).

Hafsid dynasty of Tunis

TheHafsid dynasty

The Hafsid dynasty ( ) was a Sunni Muslim dynasty of Berbers, Berber descentC. Magbaily Fyle, ''Introduction to the History of African Civilization: Precolonial Africa'', (University Press of America, 1999), 84. that ruled Ifriqiya (modern day Tu ...

(1230–1574) succeeded Almohad

The Almohad Caliphate (; or or from ) or Almohad Empire was a North African Berber Muslim empire founded in the 12th century. At its height, it controlled much of the Iberian Peninsula (Al-Andalus) and North Africa (the Maghreb).

The Almohad ...

rule in Ifriqiya, with the Hafsids claiming to represent the true spiritual heritage of its founder, the Mahdi Ibn Tumart

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad Ibn Tūmart (, ca. 1080–1130) was a Muslim religion, religious scholar, teacher and political leader, from the Sous in southern present-day Morocco. He founded and served as the spiritual and first military leader ...

(c. 1077 – 1130). For a brief moment a Hafsid sovereign would be recognized as the Caliph

A caliphate ( ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with Khalifa, the title of caliph (; , ), a person considered a political–religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of ...

of Islam. Tunisia under the Hafsids would eventually regain for a time cultural primacy in the Maghrib.

Political chronology

Abu Hafs 'Umar Inti was one of the ''Ten'', the crucial group composed of very early adherents to the ''Almohad'' movement 'al-Muwahhidun'' circa 1121. These ''Ten'' were companions of Ibn Tumart the Mahdi, and formed an inner circle consulted on all important matters. Abu Hafs 'Umar Inti, wounded in battle nearMarrakesh

Marrakesh or Marrakech (; , ) is the fourth-largest city in Morocco. It is one of the four imperial cities of Morocco and is the capital of the Marrakesh–Safi Regions of Morocco, region. The city lies west of the foothills of the Atlas Mounta ...

in 1130, was for a long time a powerful figure within the Almohad movement. His son 'Umar al-Hintati was appointed by the Almohad caliph Muhammad an-Nasir as governor of Ifriqiya in 1207 and served until his death in 1221. His son, the grandson of Abu Hafs, was Abu Zakariya.

Abu Zakariya (1203–1249) served the Almohads in Ifriqiya as governor of Gabès

Gabès (, ; ), also spelled Cabès, Cabes, and Kabes, is the capital of the Gabès Governorate in Tunisia. Situated on the coast of the Gulf of Gabès, the city has a population of 167,863, making it the 6th largest city in Tunisia. Located 327 ...

, then in 1226 as governor of Tunis

Tunis (, ') is the capital city, capital and largest city of Tunisia. The greater metropolitan area of Tunis, often referred to as "Grand Tunis", has about 2,700,000 inhabitants. , it is the third-largest city in the Maghreb region (after Casabl ...

. In 1229 during disturbances within the Almohad movement, Abu Zakariya declared his independence, having the Mahdi's name declared at Friday prayer, but himself taking the title of Amir

Emir (; ' (), also transliterated as amir, is a word of Arabic origin that can refer to a male monarch, aristocrat, holder of high-ranking military or political office, or other person possessing actual or ceremonial authority. The title has ...

: hence, the start of the Hafsid dynasty (1229–1574). In the next few years he secured his hold on the cities of Ifriqiya, then captured Tripolitania

Tripolitania (), historically known as the Tripoli region, is a historic region and former province of Libya.

The region had been settled since antiquity, first coming to prominence as part of the Carthaginian empire. Following the defeat ...

(1234) to the east, and to the west Algiers

Algiers is the capital city of Algeria as well as the capital of the Algiers Province; it extends over many Communes of Algeria, communes without having its own separate governing body. With 2,988,145 residents in 2008Census 14 April 2008: Offi ...

(1235) and later Tlemcen

Tlemcen (; ) is the second-largest city in northwestern Algeria after Oran and is the capital of Tlemcen Province. The city has developed leather, carpet, and textile industries, which it exports through the port of Rachgoun. It had a population of ...

(1242). He solidified his rule among the Berber confederacies. Government structure of the Hafsid state followed the Almohad model, a rather strict hierarchy and centralization. Abu Zakariya's succession to the Almohad movement was acknowledged as the only state maintaining Almohad traditions, and was recognized in Friday prayer by many states in Al-Andalus and in Morocco (including the Merinids). Diplomatic relations were opened with Frederick II of Sicily, Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

, Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

, and Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and ; ) is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces of Spain, ...

. Abu Zakariya the founder of the Hafsids became the foremost ruler in the Maghrib.

For an historic moment, the son of Abu Zakariya and self-declared caliph of the Hafsids, al-Mustansir (r.1249-1277), was recognised as Caliph

A caliphate ( ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with Khalifa, the title of caliph (; , ), a person considered a political–religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of ...

by Mecca and the Islamic world (1259–1261), following termination of the Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate or Abbasid Empire (; ) was the third caliphate to succeed the prophets and messengers in Islam, Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib (566–653 C ...

caliphate by the Mongols in 1258. Yet the moment passed as a rival claimant to the title advanced; the Hafsids remained a local sovereignty.

Since their origins with Abu Zakariya the Hafsids had represented their regime as heir to the Almohad movement founded by the Mahdi

Since their origins with Abu Zakariya the Hafsids had represented their regime as heir to the Almohad movement founded by the Mahdi Ibn Tumart

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad Ibn Tūmart (, ca. 1080–1130) was a Muslim religion, religious scholar, teacher and political leader, from the Sous in southern present-day Morocco. He founded and served as the spiritual and first military leader ...

, whose name was invoked during Friday prayer at emirate mosques until the 15th century. Hafsid government was accordingly constituted after the Almohad model created by the Mahdi, i.e., it being rigorous hierarchy

A hierarchy (from Ancient Greek, Greek: , from , 'president of sacred rites') is an arrangement of items (objects, names, values, categories, etc.) that are represented as being "above", "below", or "at the same level as" one another. Hierarchy ...

. The Amir held all power with a code of etiquette surrounding his person, although as sovereign he did not always hold himself aloof. The Amir's counsel was the ''Ten'', composed of the chief Almohad shaiks. Next in order was the ''Fifty'' assembled from petty shaiks, with ordinary shaiks thereafter. The early Hafsids had a censor, the ''mazwar'', who supervised the ranking of the designated shaiks and assigned them to specified categories. Originally there were three ministers 'wazir'', plural ''wuzara'' of the army (commander and logistics); of finance (accounting and tax); and, of state (correspondence and police). Over the centuries the office of ''Hajib'' increased in importance, at first being major-domo of the palace, then intermediary between the Amir and his cabinet, and finally de facto the first minister. State authority was publicly asserted by impressive processions: high officials on horseback parading to the sound of kettledrums and tambors, with colorful silk banners held high, all in order to cultivate a regal pomp. In provinces where the Amir enjoyed recognized authority, his governors were usually close family members, assisted by an experienced official. Elsewhere provincial appointees had to contend with strong local oligarchies

Oligarchy (; ) is a form of government in which power rests with a small number of people. Members of this group, called oligarchs, generally hold usually hard, but sometimes soft power through nobility, fame, wealth, or education; or thr ...

or leading families. Regarding the rural tribes, various strategies were employed; for those on good terms their tribal shaik might work as a double agent, serving as their representative to the central government, and also as government agent to his fellow tribal members.

In 1270 King Louis IX of France

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), also known as Saint Louis, was King of France from 1226 until his death in 1270. He is widely recognized as the most distinguished of the Direct Capetians. Following the death of his father, Louis VI ...

, whose brother was the king of Sicily, landed an army near Tunis; disease devastated their camp. Later, Hafsid influence was reduced by the rise of the Moroccan Marinids of Fez, who captured and lost Tunis twice (1347, and 1357). Yet Hafsid fortunes would recover; two notable rulers being Abu Faris (1394–1434) and his grandson Abu 'Amr 'Uthman (r. 1435–1488).

Toward the end, internal disarray within the Hafsid dynasty created vulnerabilities, while a great power struggle arose between Spaniard and Turk over control of the Mediterranean. The Hafsid dynasts became pawns, subject to the rival strategies of the combatants. By 1574 Ifriqiya had been incorporated into the Ottoman Empire