History of Los Angeles on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The modern history of

The lives of the Tongva were governed by a set of religious and cultural practices that included belief in creative supernatural forces. They worshipped Chinigchinix, a creator god, and Chukit, a female virgin god. Their Great Morning Ceremony was based on a belief in the afterlife. In a purification ritual, they drank '' tolguache'', a

The lives of the Tongva were governed by a set of religious and cultural practices that included belief in creative supernatural forces. They worshipped Chinigchinix, a creator god, and Chukit, a female virgin god. Their Great Morning Ceremony was based on a belief in the afterlife. In a purification ritual, they drank '' tolguache'', a

Zúñiga's party arrived at the mission on 18 July 1781. Some had

Zúñiga's party arrived at the mission on 18 July 1781. Some had

The first settlers built a water system consisting of ditches (''zanjas'') leading from the river through the middle of town and into the farmlands. Indians were employed to haul fresh drinking water from a special pool farther upstream. The city was first known as a producer of fine wine grapes. The raising of cattle and the commerce in tallow and hides came later.

Because of the great economic potential for Los Angeles, the demand for Indian labor grew rapidly. Yaanga began attracting Indians from the Channel Islands and as far away as

The first settlers built a water system consisting of ditches (''zanjas'') leading from the river through the middle of town and into the farmlands. Indians were employed to haul fresh drinking water from a special pool farther upstream. The city was first known as a producer of fine wine grapes. The raising of cattle and the commerce in tallow and hides came later.

Because of the great economic potential for Los Angeles, the demand for Indian labor grew rapidly. Yaanga began attracting Indians from the Channel Islands and as far away as

Mexico's independence from Spain on September 28, 1821, was celebrated with great festivity throughout Alta California. No longer subjects of the king, people were now ''ciudadanos'', citizens with rights under the law. In the plazas of Monterey, Santa Barbara, Los Angeles, and other settlements, people swore allegiance to the new government, the Spanish flag was lowered, and the flag of independent Mexico raised.

Independence brought other advantages, including economic growth. There was a corresponding increase in population as more Indians were assimilated and others arrived from America, Europe, and other parts of Mexico. Before 1820, there were just 650 people in the pueblo. By 1841, the population nearly tripled to 1,680.

Mexico's independence from Spain on September 28, 1821, was celebrated with great festivity throughout Alta California. No longer subjects of the king, people were now ''ciudadanos'', citizens with rights under the law. In the plazas of Monterey, Santa Barbara, Los Angeles, and other settlements, people swore allegiance to the new government, the Spanish flag was lowered, and the flag of independent Mexico raised.

Independence brought other advantages, including economic growth. There was a corresponding increase in population as more Indians were assimilated and others arrived from America, Europe, and other parts of Mexico. Before 1820, there were just 650 people in the pueblo. By 1841, the population nearly tripled to 1,680.

According to historian Mary P. Ryan, "The U.S. army swept into California with the surveyor as well as the sword and quickly translated Spanish and Mexican practices into cartographic representations." Under colonial law, land held by grantees was not disposable. It reverted to the government. It was determined that under U.S. property law, lands owned by the city were disposable. Also, the ''diseños'' (property sketches) held by residents did not secure title in an American court.

California's new military governor Bennett C. Riley ruled that land could not be sold that was not on a city map. In 1849, Lieutenant

According to historian Mary P. Ryan, "The U.S. army swept into California with the surveyor as well as the sword and quickly translated Spanish and Mexican practices into cartographic representations." Under colonial law, land held by grantees was not disposable. It reverted to the government. It was determined that under U.S. property law, lands owned by the city were disposable. Also, the ''diseños'' (property sketches) held by residents did not secure title in an American court.

California's new military governor Bennett C. Riley ruled that land could not be sold that was not on a city map. In 1849, Lieutenant  Los Angeles had several active "Vigilance Committees" during that era. Between 1850 and 1870, mobs carried out approximately 35 lynchings of Mexicans—more than four times the number that occurred in San Francisco. Los Angeles was described as "undoubtedly the toughest town of the entire nation." The homicide rate between 1847 and 1870 averaged 158 per 100,000 (13 murders per year), which was 10 to 20 times the annual murder rates for

Los Angeles had several active "Vigilance Committees" during that era. Between 1850 and 1870, mobs carried out approximately 35 lynchings of Mexicans—more than four times the number that occurred in San Francisco. Los Angeles was described as "undoubtedly the toughest town of the entire nation." The homicide rate between 1847 and 1870 averaged 158 per 100,000 (13 murders per year), which was 10 to 20 times the annual murder rates for

When New England author and Indian-rights activist

When New England author and Indian-rights activist

In the 1870s, Los Angeles was still little more than a village of 5,000. By 1900, there were over 100,000 occupants of the city. Several men actively promoted Los Angeles, working to develop it into a great city and to make themselves rich. Angelenos set out to remake their geography to challenge San Francisco with its port facilities, railway terminal, banks and factories. The Farmers and Merchants Bank of Los Angeles was the first incorporated bank in Los Angeles, founded in 1871 by John G. Downey and Isaias W. Hellman. Wealthy Easterners who came as tourists recognized the growth opportunities and invested heavily in the region. During the 1880s and 1890s, the central business district (CBD) grew along Main and Spring streets towards Second Street and beyond. In Downtown Los Angeles, there was an archaeological excavation in 1996 on the site of

In the 1870s, Los Angeles was still little more than a village of 5,000. By 1900, there were over 100,000 occupants of the city. Several men actively promoted Los Angeles, working to develop it into a great city and to make themselves rich. Angelenos set out to remake their geography to challenge San Francisco with its port facilities, railway terminal, banks and factories. The Farmers and Merchants Bank of Los Angeles was the first incorporated bank in Los Angeles, founded in 1871 by John G. Downey and Isaias W. Hellman. Wealthy Easterners who came as tourists recognized the growth opportunities and invested heavily in the region. During the 1880s and 1890s, the central business district (CBD) grew along Main and Spring streets towards Second Street and beyond. In Downtown Los Angeles, there was an archaeological excavation in 1996 on the site of

The San Pedro forces eventually prevailed (though it required Banning and Downey to turn their railroad over to the Southern Pacific). Work on the San Pedro breakwater began in 1899 and was finished in 1910. Otis Chandler and his allies secured a change in state law in 1909 that allowed Los Angeles to absorb San Pedro and Wilmington, using a long, narrow corridor of land to connect them with the rest of the city. The debacle of the future Los Angeles harbor was termed the Free Harbor Fight.

Streetcar service in Los Angeles began with horsecars (1874–1897), cable cars (1885–1902) and electric streetcars starting in 1887–1963. In 1898, Henry Huntington and a San Francisco syndicate led by Isaias W. Hellman purchased five trolley lines, consolidated them into the

The San Pedro forces eventually prevailed (though it required Banning and Downey to turn their railroad over to the Southern Pacific). Work on the San Pedro breakwater began in 1899 and was finished in 1910. Otis Chandler and his allies secured a change in state law in 1909 that allowed Los Angeles to absorb San Pedro and Wilmington, using a long, narrow corridor of land to connect them with the rest of the city. The debacle of the future Los Angeles harbor was termed the Free Harbor Fight.

Streetcar service in Los Angeles began with horsecars (1874–1897), cable cars (1885–1902) and electric streetcars starting in 1887–1963. In 1898, Henry Huntington and a San Francisco syndicate led by Isaias W. Hellman purchased five trolley lines, consolidated them into the

On Christmas Day, 1913, police attempted to break up an IWW rally of 500 taking place in the Plaza. Encountering resistance, the police waded into the crowd attacking them with their clubs. One citizen was killed. In the aftermath, the authorities attempted to impose martial law in the wake of growing protests. Seventy-three people were arrested in connection with the riots. The city council introduced new measures to control public speaking. The ''Times'' called onlookers and taco vendors "cultural subversives."

The open shop campaign continued from strength to strength, although not without meeting opposition from workers. By 1923, the

On Christmas Day, 1913, police attempted to break up an IWW rally of 500 taking place in the Plaza. Encountering resistance, the police waded into the crowd attacking them with their clubs. One citizen was killed. In the aftermath, the authorities attempted to impose martial law in the wake of growing protests. Seventy-three people were arrested in connection with the riots. The city council introduced new measures to control public speaking. The ''Times'' called onlookers and taco vendors "cultural subversives."

The open shop campaign continued from strength to strength, although not without meeting opposition from workers. By 1923, the  The immigrants arriving in the city to find jobs sometimes brought the revolutionary zeal and idealism of their homelands. These included anarchists such as Russian

The immigrants arriving in the city to find jobs sometimes brought the revolutionary zeal and idealism of their homelands. These included anarchists such as Russian

The

The  Today, the Los Angeles River functions mainly as a flood control. A drop of rain falling in the San Gabriel Mountains will reach the sea faster than an auto can drive. During today's rainstorms, the volume of the Los Angeles River at Long Beach can be as large as the

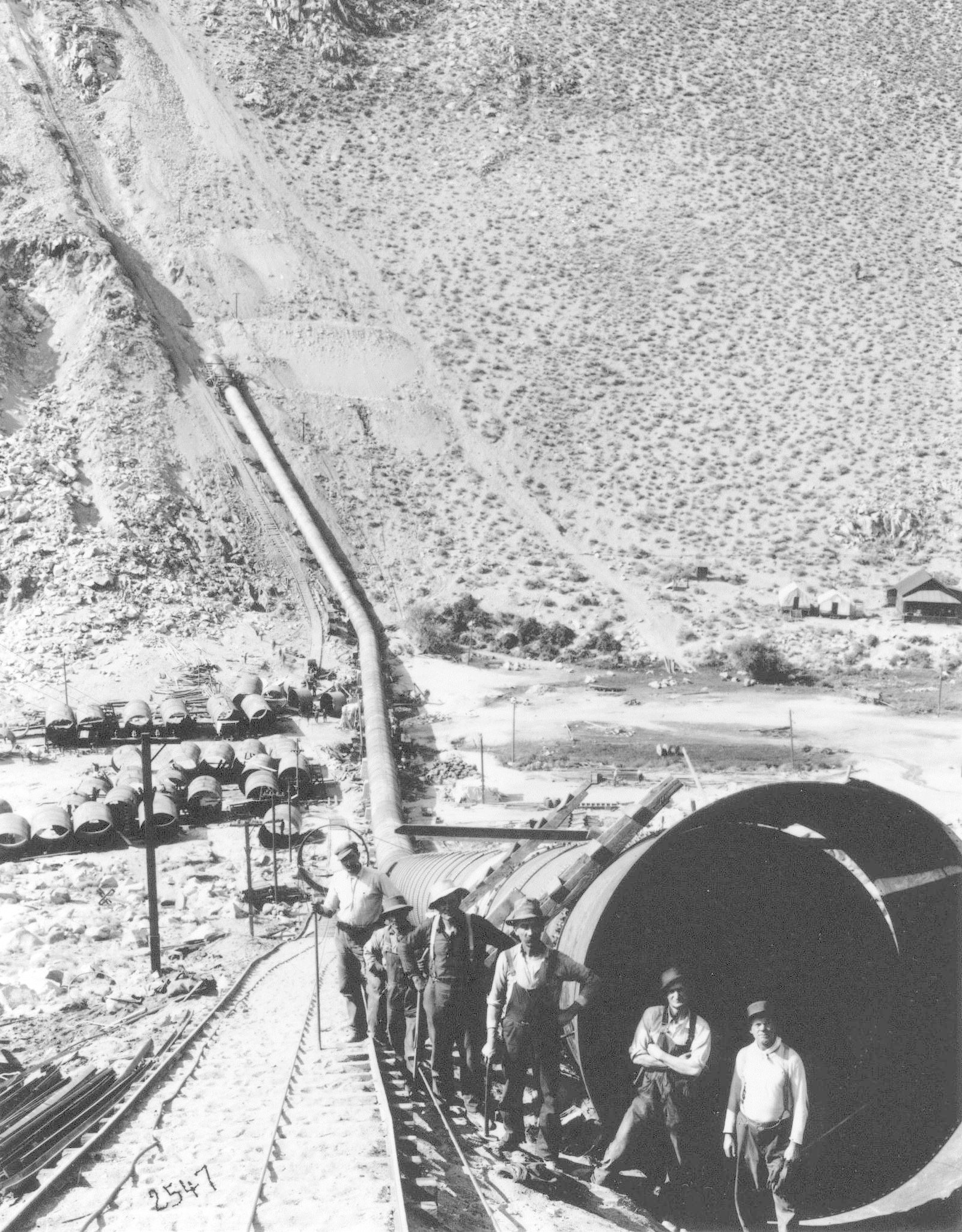

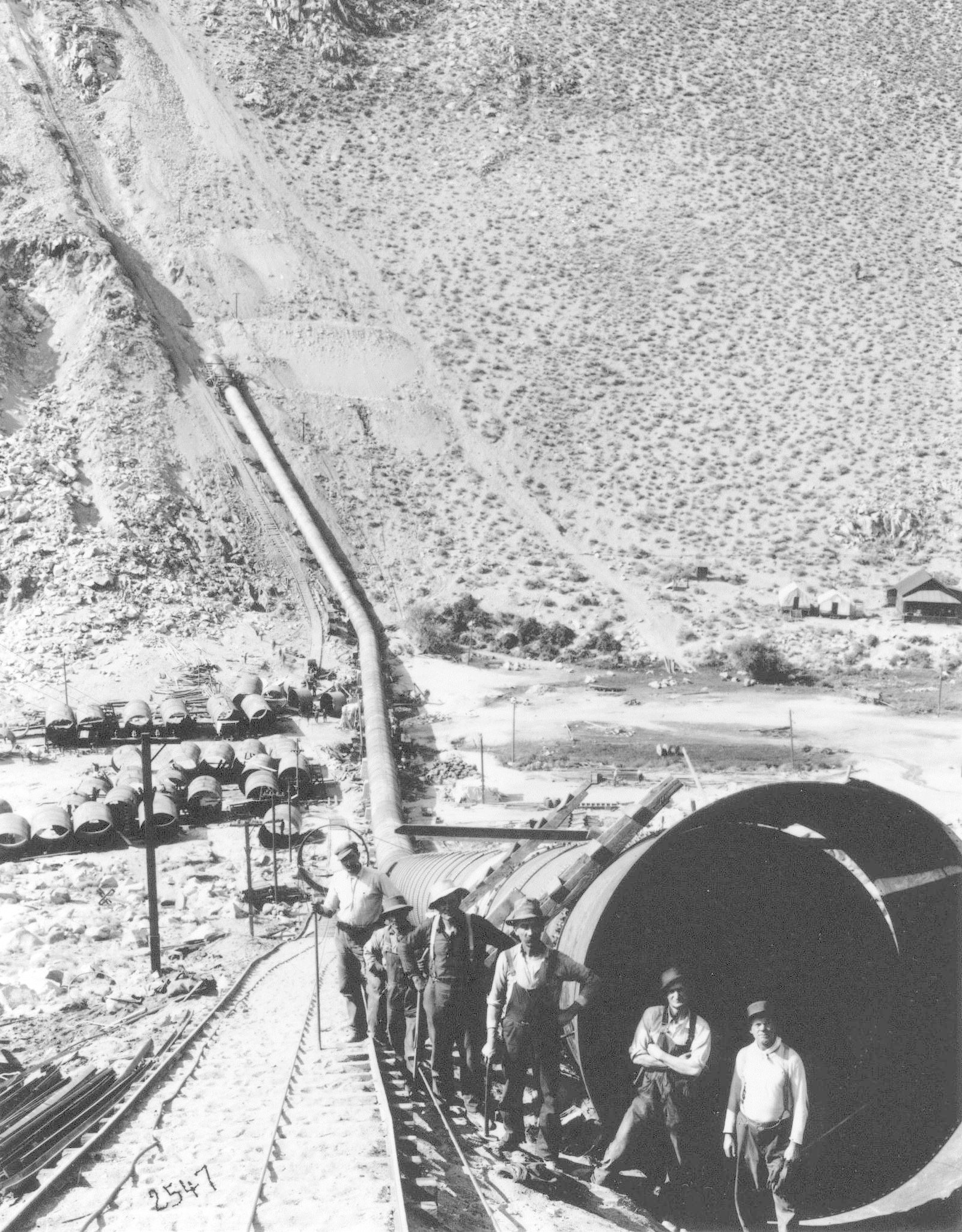

Today, the Los Angeles River functions mainly as a flood control. A drop of rain falling in the San Gabriel Mountains will reach the sea faster than an auto can drive. During today's rainstorms, the volume of the Los Angeles River at Long Beach can be as large as the  Lippencott performed water surveys in the Owens Valley for the Service while secretly receiving a salary from the City of Los Angeles. He succeeded in persuading Owens Valley farmers and mutual water companies to pool their interests and surrender the water rights to 200,000 acres (800 km2) of land to Fred Eaton, Lippencott's agent and a former mayor of Los Angeles. Lippencott then resigned from the Reclamation Service, took a job with the Los Angeles Water Department as assistant to Mulholland, and turned over the Reclamation Service maps, field surveys and stream measurements to the city. Those studies served as the basis for designing the longest aqueduct in the world.

By July 1905, the ''Times'' began to warn the voters of Los Angeles that the county would soon dry up unless they voted bonds for building the aqueduct. Artificial drought conditions were created when water was run into the sewers to decrease the supply in the reservoirs and residents were forbidden to water their lawns and gardens.

On election day, the people of Los Angeles voted for $22.5 million worth of bonds to build an aqueduct from the Owens River and to defray other expenses of the project. With this money, and with an

Lippencott performed water surveys in the Owens Valley for the Service while secretly receiving a salary from the City of Los Angeles. He succeeded in persuading Owens Valley farmers and mutual water companies to pool their interests and surrender the water rights to 200,000 acres (800 km2) of land to Fred Eaton, Lippencott's agent and a former mayor of Los Angeles. Lippencott then resigned from the Reclamation Service, took a job with the Los Angeles Water Department as assistant to Mulholland, and turned over the Reclamation Service maps, field surveys and stream measurements to the city. Those studies served as the basis for designing the longest aqueduct in the world.

By July 1905, the ''Times'' began to warn the voters of Los Angeles that the county would soon dry up unless they voted bonds for building the aqueduct. Artificial drought conditions were created when water was run into the sewers to decrease the supply in the reservoirs and residents were forbidden to water their lawns and gardens.

On election day, the people of Los Angeles voted for $22.5 million worth of bonds to build an aqueduct from the Owens River and to defray other expenses of the project. With this money, and with an

The opening of the Los Angeles Aqueduct provided the city with four times as much water as it required, and the offer of water service became a powerful lure for neighboring communities. The city, saddled with a large bond and excess water, locked in customers through annexation by refusing to supply other communities. Harry Chandler, a major investor in

The opening of the Los Angeles Aqueduct provided the city with four times as much water as it required, and the offer of water service became a powerful lure for neighboring communities. The city, saddled with a large bond and excess water, locked in customers through annexation by refusing to supply other communities. Harry Chandler, a major investor in

The police Intelligence Squad spied on anyone even suspected of criticizing the police. They included journalist Carey McWilliams, the District Attorney, Judge Fletcher Bowron, and two of the county supervisors.

The persistent courage of Clinton, Superior Court Judge and later Mayor, Fletcher Bowron, and former police detective Harry J. Raymond turned the tide. The police became so nervous that the Intelligence Squad blew up Raymond's car and nearly killed him. The public was so enraged by the bombing that it quickly voted Shaw out of office, one of the first big-city recalls in the country's history. The head of the intelligence squad, Earl E. Kynette, was convicted and sentenced to two years to life. Police Chief James Davis and 23 other officers were forced to resign.

Fletcher Bowron replaced Shaw as mayor in 1938 to preside over one of the more dynamic periods in the history of the city. His "Los Angeles Urban Reform Revival" brought major changes to the government of Los Angeles.

In 1950, he appointed William H. Parker as chief of police. Parker pushed for more independence from political pressures that enabled him to create a more professionalized police force. The public supported him and voted in charter changes that isolated the police department from the rest of government.

Through the 1960s, the LAPD was promoted as one of the more efficient departments in the world. But Parker's administration increasingly was charged with

The police Intelligence Squad spied on anyone even suspected of criticizing the police. They included journalist Carey McWilliams, the District Attorney, Judge Fletcher Bowron, and two of the county supervisors.

The persistent courage of Clinton, Superior Court Judge and later Mayor, Fletcher Bowron, and former police detective Harry J. Raymond turned the tide. The police became so nervous that the Intelligence Squad blew up Raymond's car and nearly killed him. The public was so enraged by the bombing that it quickly voted Shaw out of office, one of the first big-city recalls in the country's history. The head of the intelligence squad, Earl E. Kynette, was convicted and sentenced to two years to life. Police Chief James Davis and 23 other officers were forced to resign.

Fletcher Bowron replaced Shaw as mayor in 1938 to preside over one of the more dynamic periods in the history of the city. His "Los Angeles Urban Reform Revival" brought major changes to the government of Los Angeles.

In 1950, he appointed William H. Parker as chief of police. Parker pushed for more independence from political pressures that enabled him to create a more professionalized police force. The public supported him and voted in charter changes that isolated the police department from the rest of government.

Through the 1960s, the LAPD was promoted as one of the more efficient departments in the world. But Parker's administration increasingly was charged with

Mines Field opened as the private airport in 1930, and the city purchased it to be the municipal airfield in 1937. The name became Los Angeles Airport in 1941 and Los Angeles International Airport in 1949. In the 1930s, the main airline airports were

Mines Field opened as the private airport in 1930, and the city purchased it to be the municipal airfield in 1937. The name became Los Angeles Airport in 1941 and Los Angeles International Airport in 1949. In the 1930s, the main airline airports were

During

During  As with a few other wartime industrial cities in the U.S., Los Angeles experienced a racial-related conflict stemming from the

As with a few other wartime industrial cities in the U.S., Los Angeles experienced a racial-related conflict stemming from the  While Los Angeles County never faced enemy bombing and invasion, it nevertheless became an integral part of the American Theater on the night of February 24–25, 1942, during the false Battle of Los Angeles, which occurred a day after the Japanese naval

While Los Angeles County never faced enemy bombing and invasion, it nevertheless became an integral part of the American Theater on the night of February 24–25, 1942, during the false Battle of Los Angeles, which occurred a day after the Japanese naval

After the war, hundreds of land developers bought land cheap, subdivided it, built on it, and got rich. Real-estate development replaced oil and agriculture as Southern California's principal industry. In July 1955,

After the war, hundreds of land developers bought land cheap, subdivided it, built on it, and got rich. Real-estate development replaced oil and agriculture as Southern California's principal industry. In July 1955,

The COVID-19 pandemic started in Los Angeles in 2020. The first death from COVID in L.A. County was reported on March 11, 2020. Over the next few weeks, much of the city shut down, including businesses, schools, and parks. On March 20, Eric Garcetti ordered a stay-at-home order. Some of these restrictions lasted until the end of the year, or were reinstated when a new surge of COVID started in November 2020.

During the summer of 2020, L.A. also experienced mass protests of the Black Lives Matter movement as a part of the George Floyd protests, nationwide protests over police brutality, brought on by the killing of unarmed Black man George Floyd in Minnesota. L.A. had some rioting during this time, as protesters fought with the LAPD.

In January 2021, L.A. County became the nation's leading hotspot for COVID-19, being the nation's first county to receive 1 million cases of the disease since the start of the pandemic; NBC News reported on January 14, 2021 that one person in L.A. County died from the disease every 6 minutes. For the next few years, COVID surged every summer in the city. During the pandemic, there was an increase of crime within L.A. While crime went down over the next few years, L.A. experienced a homelessness crisis, as many public parks became occupied by homeless camps. The city also created a task force to prevent homeless people from receiving COVID-19.

Karen Bass was elected mayor in 2022. During her term, scrutiny was given toward List of LASD deputy gangs, criminal gangs made up of acting deputies of the L.A. County Sheriff's Department. Many criminal charges were filed towards the officers.

In 2023, Hollywood writers 2023 Hollywood labor disputes, went on strike again, partially because of the fear of artificial intelligence—which had made significant advances in the past few years—taking the place of writers. Hollywood production was again shut down, and the writers achieved some of their goals as exploitation of A.I. was curbed, but the question of A.I.'s use in other fields of filmmaking was left open.

From January 7 to January 31, 2025, the series of January 2025 Southern California wildfires, wildfires affected the Greater Los Angeles, Los Angeles metropolitan area and surrounding regions. The fires, which include the Palisades Fire, Eaton Fire, Hurst Fire, and Sunset Fire, were exacerbated by very low humidity, dry conditions, and hurricane-force Santa Ana winds that in some places exceeded 80 miles per hour (130 km/h). As of April 3, the wildfires have resulted in 30 deaths, destroyed or damaged more than 5,000 structures, and forced more than 137,000 people to evacuate. Insured losses were expected to exceed $20 billion, a new record for wildfire-related insurance claims in US history.

The COVID-19 pandemic started in Los Angeles in 2020. The first death from COVID in L.A. County was reported on March 11, 2020. Over the next few weeks, much of the city shut down, including businesses, schools, and parks. On March 20, Eric Garcetti ordered a stay-at-home order. Some of these restrictions lasted until the end of the year, or were reinstated when a new surge of COVID started in November 2020.

During the summer of 2020, L.A. also experienced mass protests of the Black Lives Matter movement as a part of the George Floyd protests, nationwide protests over police brutality, brought on by the killing of unarmed Black man George Floyd in Minnesota. L.A. had some rioting during this time, as protesters fought with the LAPD.

In January 2021, L.A. County became the nation's leading hotspot for COVID-19, being the nation's first county to receive 1 million cases of the disease since the start of the pandemic; NBC News reported on January 14, 2021 that one person in L.A. County died from the disease every 6 minutes. For the next few years, COVID surged every summer in the city. During the pandemic, there was an increase of crime within L.A. While crime went down over the next few years, L.A. experienced a homelessness crisis, as many public parks became occupied by homeless camps. The city also created a task force to prevent homeless people from receiving COVID-19.

Karen Bass was elected mayor in 2022. During her term, scrutiny was given toward List of LASD deputy gangs, criminal gangs made up of acting deputies of the L.A. County Sheriff's Department. Many criminal charges were filed towards the officers.

In 2023, Hollywood writers 2023 Hollywood labor disputes, went on strike again, partially because of the fear of artificial intelligence—which had made significant advances in the past few years—taking the place of writers. Hollywood production was again shut down, and the writers achieved some of their goals as exploitation of A.I. was curbed, but the question of A.I.'s use in other fields of filmmaking was left open.

From January 7 to January 31, 2025, the series of January 2025 Southern California wildfires, wildfires affected the Greater Los Angeles, Los Angeles metropolitan area and surrounding regions. The fires, which include the Palisades Fire, Eaton Fire, Hurst Fire, and Sunset Fire, were exacerbated by very low humidity, dry conditions, and hurricane-force Santa Ana winds that in some places exceeded 80 miles per hour (130 km/h). As of April 3, the wildfires have resulted in 30 deaths, destroyed or damaged more than 5,000 structures, and forced more than 137,000 people to evacuate. Insured losses were expected to exceed $20 billion, a new record for wildfire-related insurance claims in US history.

Historical Census Populations of Counties and Incorporated Cities in California, 1850–2010

'

online

* * Holli, Melvin G., and Jones, Peter d'A., eds. ''Biographical Dictionary of American Mayors, 1820-1980'' (Greenwood Press, 1981) short scholarly biographies each of the city's mayors 1820 to 1980

online

see index at p. 409 for list. * Hart, James D. '' A Companion to California'' (2nd ed. U of California Press, 1987), 610pp; excellent encyclopedic coverage of 3000 topics; not online. * Longstreth, Richard. ''The Drive-In, the Supermarket, and the Transformation of Commercial Space in Los Angeles, 1914–1941'' (MIT Press, 1999) * Lotchin, Roger W. ed. ''The Way We Really Were: The Golden State in the Second Great War'' (University of Illinois Press, 2000), essays by experts. * Pitt, Leonard. ''Los Angeles A to Z: An Encyclopedia of the City and County.'' (University of California Press, 1997) 625pp; excellent encyclopedic coverage of 2000 topics; not online. * Rolle, Andrew, and Arthur C. Verge. ''California: A history'' (John Wiley & Sons, 2014). * Schiesl, Martin J. "Progressive Reform in Los Angeles under Mayor Alexander, 1909-1913." ''California Historical Quarterly'' 54.1 (1975): 37-56. * Some of the best cultural history appears in the appropriate chapters of the multi-volume History of California by Kevin Starr, including ** ''Americans and the California Dream, 1850–1915'' (1973) ** ''Inventing the Dream: California through the Progressive Era'' (1985) ** ''Material Dreams: Southern California through the 1920s'' (1990) * Verge, Arthur C. "The impact of the Second World War on Los Angeles: 1939-1945" (PhD dissertation, University of Southern California; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 1988. DP28798). * Verge, Arthur C. "The Impact of the Second World War on Los Angeles." ''Pacific Historical Review'' 63.3 (1994): 289-314

online

* [http://www.lafire.com/famous_fires/fires.htm Historical archives of the Los Angeles Fire Department]

LA as Subject (KCET.org)

1947 project

about a range of Los Angeles history

Changing Times: Los Angeles in Photographs

UCLA Library Digital Collections {{Authority control History of Los Angeles

Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

began in 1781 when 44 settlers from central New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

(modern Mexico) established a permanent settlement in what is now Downtown Los Angeles

Downtown Los Angeles (DTLA) is the central business district of the city of Los Angeles. It is part of the Central Los Angeles region and covers a area. As of 2020, it contains over 500,000 jobs and has a population of roughly 85,000 residents ...

, as instructed by Spanish Governor of Las Californias, Felipe de Neve, and authorized by Viceroy Antonio María de Bucareli. After sovereignty changed from Mexico to the United States in 1849, great changes came from the completion of the Santa Fe railroad

The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway , often referred to as the Santa Fe or AT&SF, was one of the largest Class 1 railroads in the United States between 1859 and 1996.

The Santa Fe was a pioneer in intermodal freight transport; at variou ...

line from Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

to Los Angeles in 1885. "Overlanders" flooded in, mostly white Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

from the Midwest

The Midwestern United States (also referred to as the Midwest, the Heartland or the American Midwest) is one of the four census regions defined by the United States Census Bureau. It occupies the northern central part of the United States. It ...

and Upland South

The Upland South and Upper South are two overlapping cultural and geographic subregions in the inland part of the Southern United States. They differ from the Deep South and Atlantic coastal plain by terrain, history, economics, demographics, a ...

.

Los Angeles had a strong economic base in farming, oil, tourism, real estate and movies. It grew rapidly with many suburban areas inside and outside the city limits. Its motion picture industry made the city world-famous, and World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

brought new industry, especially high-tech aircraft construction. Politically the city was moderately conservative, with a weak labor union sector.

Since the 1960s, growth has slowed—and traffic delays have become infamous. Los Angeles was a pioneer in freeway development as the public transit system deteriorated. New arrivals, especially from Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

and Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

, have transformed the demographic base since the 1960s. Old industries have declined, including farming, oil, military and aircraft, but tourism, entertainment and high-tech remain strong. Over time, droughts and wildfires

A wildfire, forest fire, or a bushfire is an unplanned and uncontrolled fire in an area of Combustibility and flammability, combustible vegetation. Depending on the type of vegetation present, a wildfire may be more specifically identified as a ...

have increased in frequency and become less seasonal and more year-round, further straining the city's water security

The aim of water security is to maximize the benefits of water for humans and ecosystems. The second aim is to limit the risks of destructive impacts of water to an acceptable level. These risks include too much water (flood), too little water (d ...

.

Indigenous history

By 3000 BCE, the area was occupied by the Hokan-speaking people of the Milling Stone Period who fished, hunted sea mammals, and gathered wild seeds. They were later replaced by migrants—possibly fleeing drought in theGreat Basin

The Great Basin () is the largest area of contiguous endorheic watersheds, those with no outlets to the ocean, in North America. It spans nearly all of Nevada, much of Utah, and portions of California, Idaho, Oregon, Wyoming, and Baja Californi ...

—who spoke a Uto-Aztecan language

The Uto-Aztecan languages are a family of native American languages, consisting of over thirty languages. Uto-Aztecan languages are found almost entirely in the Western United States and Mexico. The name of the language family reflects the common ...

called Tongva

The Tongva ( ) are an Indigenous peoples of California, Indigenous people of California from the Los Angeles Basin and the Channel Islands of California, Southern Channel Islands, an area covering approximately . In the precolonial era, the peop ...

. The Tongva

The Tongva ( ) are an Indigenous peoples of California, Indigenous people of California from the Los Angeles Basin and the Channel Islands of California, Southern Channel Islands, an area covering approximately . In the precolonial era, the peop ...

people called the Los Angeles region Yaa in that tongue.

By the 1700s CE, there were 250,000 to 300,000 native people in California and 5,000 in the Los Angeles basin

The Los Angeles Basin is a sedimentary Structural basin, basin located in Southern California, in a region known as the Peninsular Ranges. The basin is also connected to an wikt:anomalous, anomalous group of east–west trending chains of mountai ...

. The land occupied and used by the Tongva covered about . It included the enormous floodplain

A floodplain or flood plain or bottomlands is an area of land adjacent to a river. Floodplains stretch from the banks of a river channel to the base of the enclosing valley, and experience flooding during periods of high Discharge (hydrolog ...

drained by the Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

and San Gabriel rivers and the southern Channel Islands

The Channel Islands are an archipelago in the English Channel, off the French coast of Normandy. They are divided into two Crown Dependencies: the Jersey, Bailiwick of Jersey, which is the largest of the islands; and the Bailiwick of Guernsey, ...

, including the Santa Barbara, San Clemente

San Clemente (; Spanish for " St. Clement" ) is a coastal city in southern Orange County, California, United States. It was named in 1925 after the Spanish colonial island (which was named after a Pope from the first century). Located in the O ...

, Santa Catalina, and San Nicolas Islands. They were part of a sophisticated group of trading partners that included the Chumash

Chumash may refer to:

*Chumash (Judaism), a Hebrew word for the Pentateuch, used in Judaism

*Chumash people, a Native American people of southern California

*Chumashan languages, Indigenous languages of California

See also

* Pentateuch (dis ...

to the west, the Cahuilla

The Cahuilla, also known as ʔívil̃uqaletem or Ivilyuqaletem, are a Native Americans in the United States, Native American people of the various tribes of the Cahuilla Nation, living in the inland areas of southern California. ...

and Mojave to the east, and the Juaneños and Luiseño

The Luiseño or Payómkawichum are an Indigenous people of California who, at the time of the first contacts with the Spanish in the 16th century, inhabited the coastal area of southern California, ranging from the present-day southern part of ...

s to the south. Their trade extended to the Colorado River

The Colorado River () is one of the principal rivers (along with the Rio Grande) in the Southwestern United States and in northern Mexico. The river, the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), 5th longest in the United St ...

and included slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

.

The lives of the Tongva were governed by a set of religious and cultural practices that included belief in creative supernatural forces. They worshipped Chinigchinix, a creator god, and Chukit, a female virgin god. Their Great Morning Ceremony was based on a belief in the afterlife. In a purification ritual, they drank '' tolguache'', a

The lives of the Tongva were governed by a set of religious and cultural practices that included belief in creative supernatural forces. They worshipped Chinigchinix, a creator god, and Chukit, a female virgin god. Their Great Morning Ceremony was based on a belief in the afterlife. In a purification ritual, they drank '' tolguache'', a hallucinogenic

Hallucinogens, also known as psychedelics, entheogens, or historically as psychotomimetics, are a large and diverse class of psychoactive drugs that can produce altered states of consciousness characterized by major alterations in thought, moo ...

made from jimson weed and salt water. Their language was called Kizh or Kij, and they practiced cremation. Boscana, Gerónimo, "Chinigchinish: An Historical Account of the Origins, Customs, and Traditions of the Indians of Alta California" in

Generations before the arrival of the Europeans, the Tongva had identified and lived in the best sites for human occupation. The survival and success of Los Angeles depended greatly on the presence of a nearby and prosperous Tongva village called Yaanga

Yaanga was a large Tongva (or Kizh) village, originally located near what is now downtown Los Angeles, just west of the Los Angeles River and beneath U.S. Route 101 in California, U.S. Route 101. People from the village were recorded as ''Yabit ...

, which was located by the freshwater artesian aquifer

An artesian well is a well that brings groundwater to the surface without pumping because it is under pressure within a body of rock or sediment known as an aquifer. When trapped water in an aquifer is surrounded by layers of Permeability (ea ...

of the Los Angeles River

The Los Angeles River (), historically known as by the Tongva and the by the Spanish, is a major river in Los Angeles County, California. Its headwaters are in the Simi Hills and Santa Susana Mountains, and it flows nearly from Canoga Park ...

. Its residents provided the colonists with seafood, fish, bowls, pelts, and baskets. For pay, they dug ditches, hauled water, and provided domestic help. They often intermarried with the Mexican colonists.

Spanish era

In 1542 and 1602, the first Europeans to visit the region were CaptainJuan Rodríguez Cabrillo

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo (; 1497 – January 3, 1543) was a Portuguese maritime explorer best known for investigations of the west coast of North America, undertaken on behalf of the Spanish Empire. He was the first European to explore presen ...

and Captain Sebastián Vizcaíno

Sebastián Vizcaíno (c. 1548–1624) was a Spanish soldier, entrepreneur, explorer, and diplomat whose varied roles took him to New Spain, the Baja California peninsula, the California coast and Asia.

Early career

Vizcaíno was born in ...

. The first permanent non-native presence began when the Portolá expedition

thumbnail, 250px, Point of San Francisco Bay Discovery

The Portolá expedition was a Spanish voyage of exploration in 1769–1770 that was the first recorded European exploration of the interior of the present-day California. It was led by Gas ...

arrived on August 2, 1769.

Plans for the pueblo

Although Los Angeles was a town that was founded by Mexican families fromSonora

Sonora (), officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Sonora (), is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the Administrative divisions of Mexico, Federal Entities of Mexico. The state is divided into Municipalities of Sonora, 72 ...

, it was the Spanish governor of California who named the settlement.

In 1777, Governor Felipe de Neve toured Alta California

Alta California (, ), also known as Nueva California () among other names, was a province of New Spain formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but was made a separat ...

and decided to establish civic pueblos for the support of the military ''presidio

A presidio (''jail, fortification'') was a fortified base established by the Spanish Empire mainly between the 16th and 18th centuries in areas under their control or influence. The term is derived from the Latin word ''praesidium'' meaning ''pr ...

s''. The new pueblos reduced the secular power of the missions by reducing the military's dependence on them. At the same time, they promoted the development of industry and agriculture.

Governor de Neve identified Santa Barbara, San Jose, and Los Angeles as sites for his new pueblos. His plans for them closely followed a set of Spanish city-planning laws contained in the Laws of the Indies

The Laws of the Indies () are the entire body of laws issued by the Spanish Crown in 1573 for the American and the Asian possessions of its empire. They regulated social, political, religious, and economic life in these areas. The laws are com ...

promulgated by King Philip II in 1573. Those laws were responsible for laying the foundations of the largest cities in the region at the time, including Los Angeles, San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

, Tucson

Tucson (; ; ) is a city in Pima County, Arizona, United States, and its county seat. It is the second-most populous city in Arizona, behind Phoenix, Arizona, Phoenix, with a population of 542,630 in the 2020 United States census. The Tucson ...

, San Antonio

San Antonio ( ; Spanish for " Saint Anthony") is a city in the U.S. state of Texas and the most populous city in Greater San Antonio. San Antonio is the third-largest metropolitan area in Texas and the 24th-largest metropolitan area in the ...

, Sonoma, Monterey

Monterey ( ; ) is a city situated on the southern edge of Monterey Bay, on the Central Coast of California. Located in Monterey County, the city occupies a land area of and recorded a population of 30,218 in the 2020 census.

The city was fou ...

, Santa Fe, and Laredo.

The Spanish system called for an open central plaza, surrounded by a fortified church, administrative buildings, and streets laid out in a grid, defining rectangles of limited size to be used for farming (''suertes'') and residences (''solares'').

It was in accordance with such precise planning—specified in the Law of the Indies—that Governor de Neve founded the pueblo of San Jose de Guadalupe, California's first municipality

A municipality is usually a single administrative division having municipal corporation, corporate status and powers of self-government or jurisdiction as granted by national and regional laws to which it is subordinate.

The term ''municipality' ...

, on the great plain of Santa Clara on 29 November 1777.

''Pobladores''

The Pobladores ("settlers") is the name given to the 22 adults and 22 children from Sonora who founded Los Angeles. Twenty were of African American or Native American descent. In December 1777, Viceroy Antonio María de Bucareli y Ursúa and Commandant General Teodoro de Croix gave approval for the founding of a civic municipality at Los Angeles and a new ''presidio,'' or garrison, at Santa Barbara. Croix put the California lieutenant governorFernando Rivera y Moncada

Fernando Javier Rivera y Moncada (c. 1725 – July 18, 1781) was a soldier of the Spanish Empire who served in The Californias (''Las Californias''), the far northwest frontier of New Spain. He participated in several early overland exploration ...

in charge of recruiting colonists for the new settlements. He was originally to recruit 55 soldiers, 22 settlers with families and a thousand head of livestock that would include horses for the military. After an exhaustive search that took him to Mazatlán

Mazatlán () is a city in the Mexican list of states of Mexico, state of Sinaloa. The city serves as the municipal seat for the surrounding , known as the Mazatlán Municipality. It is located on the Pacific Ocean, Pacific coast across from th ...

, Rosario, and Durango, Rivera y Moncada recruited only 12 settlers and 45 soldiers. Like the settlers of most towns in New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

, they had a mix of Indian and Spanish backgrounds. The Quechan

The Quechan ( Quechan: ''Kwatsáan'' 'those who descended'), or Yuma, are a Native American tribe who live on the Fort Yuma Indian Reservation on the lower Colorado River in Arizona and California just north of the Mexican border. Despite ...

Revolt killed 95 settlers and soldiers, including Rivera y Moncada.

According to Croix's ''Reglamento'', the newly baptized Indians were no longer to reside in the mission but had to live in their traditional ''rancherías'' (villages). Governor de Neve's plans for the Indians' role in his new town drew instant disapproval from the mission priests.

Zúñiga's party arrived at the mission on 18 July 1781. Some had

Zúñiga's party arrived at the mission on 18 July 1781. Some had smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

, so all were quarantined a short distance away from the mission. Members of the other party arrived at different times by August. They made their way to Los Angeles and probably received their land before September.

The official date for the founding of the city is September 4, 1781. The families had arrived from New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

earlier in 1781, in two groups, and some of them had most likely been working on their assigned plots of land since the early summer.

The name first given to the settlement is debated. Historian Doyce B. Nunis has said that the Spanish named it "El Pueblo de la Reina de los Angeles" ("The Town of the Queen of the Angels"). For proof, he pointed to a map dated 1785, where that phrase was used. Frank Weber, the diocesan archivist, replied, however, that the name given by the founders was "El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora de los Angeles de Porciuncula", or "the town of Our Lady of the Angels of Porciuncula." and that the map was in error.

Spanish pueblo

The town grew as soldiers and other settlers came into town and stayed. In 1784 a chapel was built on the original Plaza. The original Plaza was located a block north and west of the present one — its southeast corner being roughly where the northwesternmost point of the present plaza is, at the former intersection of Upper Main and Marchessault streets. It was also oriented diagonally, i.e. at precisely a 90-degree angle to the four compass points. The ''pobladores'' were given title to their land two years later. By 1800, there were 29 buildings that surrounded the Plaza, flat-roofed, one-story adobe buildings with thatched roofs made of tule. By 1821, Los Angeles had grown into a self-sustaining farming community, the largest in Southern California. The Spanish land grant to the city lands of Los Angeles was roughly a square of on each side, for an area of four square Spanish leagues, with the boundaries corresponding to present-day Fountain Avenue, Indiana Street, Exposition Boulevard and Hoover Street. Each settler received four rectangles of land, ''suertes'', for farming, two irrigated plots and two dry ones. When the settlers arrived, the Los Angeles floodplain was heavily wooded with willows and oaks. TheLos Angeles River

The Los Angeles River (), historically known as by the Tongva and the by the Spanish, is a major river in Los Angeles County, California. Its headwaters are in the Simi Hills and Santa Susana Mountains, and it flows nearly from Canoga Park ...

flowed all year. Wildlife was plentiful, including deer and black bears, and even an occasional grizzly bear

The grizzly bear (''Ursus arctos horribilis''), also known as the North American brown bear or simply grizzly, is a population or subspecies of the brown bear inhabiting North America.

In addition to the mainland grizzly (''Ursus arctos horr ...

. There were abundant wetlands and swamps. Steelhead trout and salmon

Salmon (; : salmon) are any of several list of commercially important fish species, commercially important species of euryhaline ray-finned fish from the genera ''Salmo'' and ''Oncorhynchus'' of the family (biology), family Salmonidae, native ...

swam the rivers.

The first settlers built a water system consisting of ditches (''zanjas'') leading from the river through the middle of town and into the farmlands. Indians were employed to haul fresh drinking water from a special pool farther upstream. The city was first known as a producer of fine wine grapes. The raising of cattle and the commerce in tallow and hides came later.

Because of the great economic potential for Los Angeles, the demand for Indian labor grew rapidly. Yaanga began attracting Indians from the Channel Islands and as far away as

The first settlers built a water system consisting of ditches (''zanjas'') leading from the river through the middle of town and into the farmlands. Indians were employed to haul fresh drinking water from a special pool farther upstream. The city was first known as a producer of fine wine grapes. The raising of cattle and the commerce in tallow and hides came later.

Because of the great economic potential for Los Angeles, the demand for Indian labor grew rapidly. Yaanga began attracting Indians from the Channel Islands and as far away as San Diego

San Diego ( , ) is a city on the Pacific coast of Southern California, adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a population of over 1.4 million, it is the List of United States cities by population, eighth-most populous city in t ...

and San Luis Obispo

; ; ; Chumashan languages, Chumash: ''tiłhini'') is a city and county seat of San Luis Obispo County, California, United States. Located on the Central Coast (California), Central Coast of California, San Luis Obispo is roughly halfway betwee ...

. The village began to look like a refugee camp. Unlike the missions, the ''pobladores'' paid Indians for their labor. In exchange for their work as farm workers, ''vaqueros'', ditch diggers, water haulers, and domestic help; they were paid in clothing and other goods as well as cash and alcohol. The ''pobladores'' bartered with them for prized sea-otter and seal pelts, sieves, trays, baskets, mats, and other woven goods. This commerce greatly contributed to the economic success of the town and the attraction of other Indians to the city.

During the 1780s, San Gabriel Mission became the object of an Indian revolt. The mission had expropriated all the suitable farming land; the Indians found themselves abused and forced to work on lands that they once owned. A young Indian healer, Toypurina, began touring the area, preaching against the injustices suffered by her people. She won over four ''rancherías'' and led them in an attack on the mission at San Gabriel. The soldiers were able to defend the mission, and arrested 17, including Toypurina.

In 1787, Governor Pedro Fages

Pedro Fages (1734–1794) was a Spanish soldier, explorer, and first lieutenant governor of the province of the Californias under Gaspar de Portolá. Fages claimed the governorship after Portolá's departure, acting as governor in opposition ...

outlined his "Instructions for the Corporal Guard of the Pueblo of Los Angeles." The instructions included rules for employing Indians, not using corporal punishment, and protecting the Indian ''rancherías''. As a result, Indians found themselves with more freedom to choose between the benefits of the missions and the pueblo-associated ''rancherías''.

In 1795, Sergeant Pablo Cota led an expedition from the Simi Valley

Simi Valley (; Chumash: ''Shimiyi'') is a city in the valley of the same name in southeastern Ventura County, California, United States. It is from Downtown Los Angeles, making it part of the Greater Los Angeles Area. Simi Valley borders Th ...

through the Conejo-Calabasas region and into the San Fernando Valley

The San Fernando Valley, known locally as the Valley, is an urbanized valley in Los Angeles County, Los Angeles County, California. Situated to the north of the Los Angeles Basin, it comprises a large portion of Los Angeles, the Municipal corpo ...

. His party visited the'' rancho'' of Francisco Reyes. They found the local Indians hard at work as ''vaqueros'' and caring for crops. Padre Vincente de Santa Maria was traveling with the party and made these observations:

All of pagandom (Indians) is fond of the pueblo of Los Angeles, of the rancho of Reyes, and of the ditches (water system). Here we see nothing but pagans, clad in shoes, with sombreros and blankets, and serving as muleteers to the settlers and rancheros, so that if it were not for the gentiles there were neither pueblos nor ranches. These pagan Indians care neither for the missions nor for the missionaries.Not only economic ties but also marriage drew many Indians into the life of the pueblo. In 1784, only three years after the founding, the first recorded marriages in Los Angeles took place. The two sons of settler Basilio Rosas, Maximo and José Carlos, married two young Indian women, María Antonia and María Dolores. The construction on the Plaza of La Iglesia de Nuestra Señora de Los Ángeles took place between 1818 and 1822, much of it with Indian labor. The new church completed Governor de Neve's planned transition of authority from mission to pueblo. The ''angelinos'' no longer had to make the bumpy ride to Sunday Mass at Mission San Gabriel. In 1811, the population of Los Angeles had increased to more than five hundred persons, of which ninety-one were heads of families. In 1820, the route of El Camino Viejo was established from Los Angeles, over the mountains to the north and up the west side of the

San Joaquin Valley

The San Joaquin Valley ( ; Spanish language in California, Spanish: ''Valle de San Joaquín'') is the southern half of California's Central Valley (California), Central Valley. Famed as a major breadbasket, the San Joaquin Valley is an importa ...

to the east side of San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay (Chochenyo language, Chochenyo: 'ommu) is a large tidal estuary in the United States, U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the cities of San Francisco, California, San ...

.

Mexican era

Mexico's independence from Spain on September 28, 1821, was celebrated with great festivity throughout Alta California. No longer subjects of the king, people were now ''ciudadanos'', citizens with rights under the law. In the plazas of Monterey, Santa Barbara, Los Angeles, and other settlements, people swore allegiance to the new government, the Spanish flag was lowered, and the flag of independent Mexico raised.

Independence brought other advantages, including economic growth. There was a corresponding increase in population as more Indians were assimilated and others arrived from America, Europe, and other parts of Mexico. Before 1820, there were just 650 people in the pueblo. By 1841, the population nearly tripled to 1,680.

Mexico's independence from Spain on September 28, 1821, was celebrated with great festivity throughout Alta California. No longer subjects of the king, people were now ''ciudadanos'', citizens with rights under the law. In the plazas of Monterey, Santa Barbara, Los Angeles, and other settlements, people swore allegiance to the new government, the Spanish flag was lowered, and the flag of independent Mexico raised.

Independence brought other advantages, including economic growth. There was a corresponding increase in population as more Indians were assimilated and others arrived from America, Europe, and other parts of Mexico. Before 1820, there were just 650 people in the pueblo. By 1841, the population nearly tripled to 1,680.

Secularization of the missions

During the rest of the 1820s, the agriculture and cattle ranching expanded as did the trade in hides and tallow. The new church was completed, and the political life of the city developed. Los Angeles was separated from Santa Barbara administration. The system of ditches which provided water from the river was rebuilt. In 1827 Jonathan Temple and John Rice opened the firstgeneral store

A general merchant store (also known as general merchandise store, general dealer, village shop, or country store) is a rural or small-town store that carries a general line of merchandise. It carries a broad selection of merchandise, someti ...

in the pueblo, soon followed by J. D. Leandry. Trade and commerce further increased with the secularization of the California missions by the Mexican Congress in 1833. Extensive mission lands suddenly became available to government officials, ranchers, and land speculators. The governor made more than 800 land grants during this period, including a grant of over 33,000-acres in 1839 to Francisco Sepúlveda which was later developed as the westside of Los Angeles.

Much of this progress, however, bypassed the Indians of the traditional villages who were not assimilated into the ''mestizo'' culture. Being regarded as minors who could not think for themselves, they were increasingly marginalized and relieved of their land titles, often by being drawn into debt or alcohol.

In 1835, the Mexican Congress declared Los Angeles a city, making it the official capital of Alta California. It was now the region's leading city. The same period also saw the arrival of many foreigners from the United States and Europe. They played a pivotal role in the U.S. takeover. Early California settler John Bidwell included several historical figures in his recollection of people he knew in March 1845.

It then had probably two hundred and fifty people, of whom I recall Don Abel Stearns, John Temple, Captain Alexander Bell, William Wolfskill, Lemuel Carpenter, David W. Alexander; also of Mexicans,Upon arriving in Los Angeles in 1831, Jean-Louis Vignes bought of land located between the original Pueblo and the banks of thePio Pico Pio or PIO may refer to: Places * Pio Lake, Italy * Pio Island, Solomon Islands * Pio Point, Bird Island, south Atlantic Ocean People * Pio (given name) * Pio (surname) * Pio (footballer, born 1986), Brazilian footballer * Pio (footballer, ...(governor), DonJuan Bandini Juan Bandini (1800 – November 4, 1859) was a Peruvian-born Californio public figure, politician, and ranchero. He is best known for his role in the development of San Diego in the mid-19th century. Early history Bandini was born in 1800 in Lima ..., and others.

Los Angeles River

The Los Angeles River (), historically known as by the Tongva and the by the Spanish, is a major river in Los Angeles County, California. Its headwaters are in the Simi Hills and Santa Susana Mountains, and it flows nearly from Canoga Park ...

. He planted a vineyard and prepared to make wine. He named his property ''El Aliso'' after the centuries-old tree found near the entrance. The grapes available at the time, of the Mission variety, were brought to Alta California by the Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent Religious institute, religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor bei ...

Brothers at the end of the 18th century. They grew well and yielded large quantities of wine, but Jean-Louis Vignes was not satisfied with the results.

In 1840, Jean-Louis Vignes made the first recorded shipment of California wine. The Los Angeles market was too small for his production, and he loaded a shipment on the ''Monsoon'', bound for Northern California. By 1842, he made regular shipments to Santa Barbara, Monterey

Monterey ( ; ) is a city situated on the southern edge of Monterey Bay, on the Central Coast of California. Located in Monterey County, the city occupies a land area of and recorded a population of 30,218 in the 2020 census.

The city was fou ...

and San Francisco. By 1849, ''El Aliso'', was the most extensive vineyard in California. Vignes owned over 40,000 vines and produced 150,000 bottles, or 1,000 barrels, per year.

In 1836, the Indian village of Yaanga was relocated near the future corner of Commercial and Alameda Streets. In 1845, it was relocated again to present-day Boyle Heights

Boyle may refer to:

Places United States

* Boyle, Kansas, an unincorporated community

* Boyle, Mississippi, a town

*Boyle County, Kentucky

*Boyle Heights, Los Angeles, a neighborhood

Elsewhere

* Boyle (crater), a lunar crater

* 11967 Boyle, ...

. With the coming of the U.S. citizens, disease took a great toll among Indians. Self-employed Indians were not allowed to sleep over in the city. They faced increasing competition for jobs as more Mexicans moved into the area and took over the labor force. Those who loitered or were drunk or unemployed were arrested and auctioned off as laborers to those who paid their fines. They were often paid for work with liquor, which only increased their problems.

U.S. Conquest of California

In May 1846, theMexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

started, soon leading to the American conquest of California. Because of Mexico's inability to defend its northern territories, California was exposed to invasion. On August 13, 1846, Commodore Robert F. Stockton

Robert Field Stockton (August 20, 1795 – October 7, 1866) was a United States Navy commodore, notable in the capture of California during the Mexican–American War. He was a naval innovator and an early advocate for a propeller-driven, steam- ...

, accompanied by John C. Frémont

Major general (United States), Major-General John Charles Frémont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was a United States Army officer, explorer, and politician. He was a United States senator from California and was the first History of the Repub ...

, seized the town; Governor Pico had fled to Mexico. From Stockton and Frémont until late 1849, all of California had a military governor. After three weeks of occupation, Stockton left, leaving Lieutenant Archibald H. Gillespie in charge. Subsequent dissatisfaction with Gillespie and his troops led to an uprising.

A force of 300 locals drove the Americans out, ending the first phase of the Battle of Los Angeles. Further small skirmishes took place. Stockton regrouped in San Diego and marched north with six hundred troops while Frémont marched south from Monterey with 400 troops. After a few skirmishes outside the city, the two forces entered Los Angeles, this time without bloodshed. Andrés Pico

Andrés Pico (November 18, 1810 – February 14, 1876) was a Californio who became a successful rancher, fought in the contested Battle of San Pascual during the Mexican–American War, and negotiated promises of post-war protections for Calif ...

was in charge; he signed the Treaty of Cahuenga

The Treaty of Cahuenga (), also called the Capitulation of Cahuenga (''Capitulación de Cahuenga''), was an 1847 agreement that ended the Conquest of California, resulting in a ceasefire between Californios and Americans. The treaty was signed ...

, also known as the Capitulation of Cahuenga, on 13 January 1847, ending the California phase of the Mexican–American War. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo officially ended the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). It was signed on 2 February 1848 in the town of Villa de Guadalupe, Mexico City, Guadalupe Hidalgo.

After the defeat of its army and the fall of the cap ...

, signed on 2 February 1848, ended the war and ceded California to the U.S.

Early American era

According to historian Mary P. Ryan, "The U.S. army swept into California with the surveyor as well as the sword and quickly translated Spanish and Mexican practices into cartographic representations." Under colonial law, land held by grantees was not disposable. It reverted to the government. It was determined that under U.S. property law, lands owned by the city were disposable. Also, the ''diseños'' (property sketches) held by residents did not secure title in an American court.

California's new military governor Bennett C. Riley ruled that land could not be sold that was not on a city map. In 1849, Lieutenant

According to historian Mary P. Ryan, "The U.S. army swept into California with the surveyor as well as the sword and quickly translated Spanish and Mexican practices into cartographic representations." Under colonial law, land held by grantees was not disposable. It reverted to the government. It was determined that under U.S. property law, lands owned by the city were disposable. Also, the ''diseños'' (property sketches) held by residents did not secure title in an American court.

California's new military governor Bennett C. Riley ruled that land could not be sold that was not on a city map. In 1849, Lieutenant Edward Ord

Edward Otho Cresap Ord (October 18, 1818 – July 22, 1883), frequently referred to as E. O. C. Ord, was an American engineer and United States Army officer who saw action in the Seminole War, the Indian Wars, and the American Civil War. He comma ...

surveyed Los Angeles to confirm and extend the streets of the city. His survey put the city into the real-estate business, creating its first real-estate boom and filling its treasury. Street names were changed from Spanish to English. Further surveys and street plans replaced the original plan for the pueblo with a new civic center south of the Plaza and a new use of space.

The fragmentation of Los Angeles real estate on the Anglo-Mexican axis had begun. Under the Spanish system, the residences of the power-elite clustered around the Plaza in the center of town. In the new U.S. system, the power elite resided in the outskirts. The emerging minorities, including the Chinese, Italians, French, and Russians, joined with the Mexicans near the Plaza.

In 1848, the gold discovered in Coloma first brought thousands of miners from Sonora in northern Mexico on the way to the gold fields. So many of them settled in the area north of the Plaza that it came to be known as "Sonoratown".

During the Gold Rush

A gold rush or gold fever is a discovery of gold—sometimes accompanied by other precious metals and rare-earth minerals—that brings an onrush of miners seeking their fortune. Major gold rushes took place in the 19th century in Australia, ...

years in northern California, Los Angeles became known as the "Queen of the Cow Counties" for its role in supplying beef and other foodstuffs to hungry miners in the north. Among the cow counties, Los Angeles County had the largest herds in the state followed closely by Santa Barbara and Monterey Counties.

With the temporary absence of a legal system, the city quickly was submerged in lawlessness. Many of the New York regiment disbanded at the end of the war and charged with maintaining order were thugs and brawlers. They roamed the streets joined by gamblers, outlaws, and prostitutes driven out of San Francisco and mining towns of the north by Vigilance Committees or lynch mobs. Los Angeles came to be known as the "toughest and most lawless city west of Santa Fe."

Some of the residents resisted the new powers by resorting to banditry against the gringos. In 1856, Juan Flores threatened Southern California with a full-scale revolt. He was hanged in Los Angeles in front of 3,000 spectators. Tiburcio Vasquez, a legend in his own time among the Mexican-born population for his daring feats against the Anglos, was captured in present-day Santa Clarita, California

Santa Clarita (; Spanish for "Little St. Clare") is a city in northwestern Los Angeles County, California, United States. With a 2020 census population of 228,673, it is the third-most populous city in Los Angeles County, the 17th-most popul ...

, on May 14, 1874. He was found guilty of two counts of murder by a San Jose jury in 1874, and was hanged there in 1875.

Los Angeles had several active "Vigilance Committees" during that era. Between 1850 and 1870, mobs carried out approximately 35 lynchings of Mexicans—more than four times the number that occurred in San Francisco. Los Angeles was described as "undoubtedly the toughest town of the entire nation." The homicide rate between 1847 and 1870 averaged 158 per 100,000 (13 murders per year), which was 10 to 20 times the annual murder rates for

Los Angeles had several active "Vigilance Committees" during that era. Between 1850 and 1870, mobs carried out approximately 35 lynchings of Mexicans—more than four times the number that occurred in San Francisco. Los Angeles was described as "undoubtedly the toughest town of the entire nation." The homicide rate between 1847 and 1870 averaged 158 per 100,000 (13 murders per year), which was 10 to 20 times the annual murder rates for New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

during the same period.

The fear of Mexican violence and the racially motivated violence inflicted on them further marginalized the Mexicans, greatly reducing their economic and political opportunities.

John Gately Downey, the seventh governor of California was sworn into office on January 14, 1860, thereby becoming the first governor from Southern California. Governor Downey was born and raised in Castlesampson, County Roscommon, Ireland, and came to Los Angeles in 1850. He was responsible for keeping California in the Union during the Civil War.

Plight of the Indigenous

Los Angeles was incorporated as a U.S. city on April 4, 1850. Five months later, California was admitted into the Union. Although the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo required the U.S. to grant citizenship to the Native Americans of former Mexican territories, it did not happen for another 80 years. TheConstitution of California

The Constitution of California () is the primary organizing law for the U.S. state of California, describing the duties, powers, structures and functions of the government of California. California's constitution was drafted in both English ...

deprived Indians of any protection under the law, considering them as non-persons. As a result, it was impossible to bring a White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wa ...

to trial for killing an Indigenous or forcing Indigenous off their properties. Whites concluded that the "quickest and best way to get rid of (their) troublesome presence was to kill them off, (and) this procedure was adopted as a standard for many years."

With the coming of the U.S. citizens, disease took a great toll among the Native Americans. Self-employed Natives were not allowed to sleep over in the city. They faced increasing competition for jobs as more Mexicans moved into the area and took over the labor force. Those who loitered or were drunk or unemployed were arrested and auctioned off as laborers to those who paid their fines. They were often paid for work with liquor, which only increased their problems.

When New England author and Indian-rights activist

When New England author and Indian-rights activist Helen Hunt Jackson

Helen Hunt Jackson (pen name, H.H.; born Helen Maria Fiske; October 15, 1830 – August 12, 1885) was an American poet and writer who became an activist on behalf of improved treatment of Native Americans by the United States government. She de ...

toured the Indian villages of Southern California in 1883, she was appalled by the racism of the Anglos living there. She wrote that they treated Indians worse than animals, hunted them for sport, robbed them of their farmlands, and brought them to the edge of extermination. While Indians were depicted by Whites as lazy and shiftless, she found most of them to be hard-working craftsmen and farmers. Jackson's tour inspired her to write her 1884 novel '' Ramona'', which she hoped would give a human face to the atrocities and indignities suffered by the Indians in California, and it did. The novel was enormously successful, inspiring four movies and a yearly pageant in Hemet, California. Many of the Indian villages of Southern California survived because of her efforts, including Morongo, Cahuilla

The Cahuilla, also known as ʔívil̃uqaletem or Ivilyuqaletem, are a Native Americans in the United States, Native American people of the various tribes of the Cahuilla Nation, living in the inland areas of southern California. ...

, Soboba, Temecula

Temecula (; , ; Luiseño: ''Temeekunga'') is a city in southwestern Riverside County, California, United States. The city had a population of 110,003 as of the 2020 census and was incorporated on December 1, 1989. The city is a tourist and ...

, Pechanga, and Warner Springs

Warner Springs is set of springs and a small unincorporated area, unincorporated community in northern San Diego County, California. It is on the Pacific Crest Trail.

Geography

Warner Springs has a post office; its ZIP Code is 92086. It is loca ...

.

Remarkably, the Tongva

The Tongva ( ) are an Indigenous peoples of California, Indigenous people of California from the Los Angeles Basin and the Channel Islands of California, Southern Channel Islands, an area covering approximately . In the precolonial era, the peop ...

also survived. in 2006, the ''Los Angeles Times'' reported that there were 2,000 of them still living in Southern California. Some were organizing to protect burial and cultural sites. Others were trying to obtain federal recognition as a tribe.

Industrial expansion and growth

In the 1870s, Los Angeles was still little more than a village of 5,000. By 1900, there were over 100,000 occupants of the city. Several men actively promoted Los Angeles, working to develop it into a great city and to make themselves rich. Angelenos set out to remake their geography to challenge San Francisco with its port facilities, railway terminal, banks and factories. The Farmers and Merchants Bank of Los Angeles was the first incorporated bank in Los Angeles, founded in 1871 by John G. Downey and Isaias W. Hellman. Wealthy Easterners who came as tourists recognized the growth opportunities and invested heavily in the region. During the 1880s and 1890s, the central business district (CBD) grew along Main and Spring streets towards Second Street and beyond. In Downtown Los Angeles, there was an archaeological excavation in 1996 on the site of

In the 1870s, Los Angeles was still little more than a village of 5,000. By 1900, there were over 100,000 occupants of the city. Several men actively promoted Los Angeles, working to develop it into a great city and to make themselves rich. Angelenos set out to remake their geography to challenge San Francisco with its port facilities, railway terminal, banks and factories. The Farmers and Merchants Bank of Los Angeles was the first incorporated bank in Los Angeles, founded in 1871 by John G. Downey and Isaias W. Hellman. Wealthy Easterners who came as tourists recognized the growth opportunities and invested heavily in the region. During the 1880s and 1890s, the central business district (CBD) grew along Main and Spring streets towards Second Street and beyond. In Downtown Los Angeles, there was an archaeological excavation in 1996 on the site of Union Station

A union station, union terminal, joint station, or joint-use station is a railway station at which the tracks and facilities are shared by two or more separate railway company, railway companies, allowing passengers to connect conveniently bet ...

which took place during the demolition of the parking structure as well as a massive excavation of the basement. Artifact deposits were typically trash pits and privies from the brothels and boarding house

A boarding house is a house (frequently a family home) in which lodging, lodgers renting, rent one or more rooms on a nightly basis and sometimes for extended periods of weeks, months, or years. The common parts of the house are maintained, and ...

s that formerly existed in that area. In addition, there was also a sheet refuse of artifacts from Old Chinatown, the nearby residential area. This area of Downtown Los Angeles was known as the crib District which was heavily occupied by brothels and saloons.

By the 1880s, families began moving out of Aliso Street near Chinatown

Chinatown ( zh, t=唐人街) is the catch-all name for an ethnic enclave of Chinese people located outside Greater China, most often in an urban setting. Areas known as "Chinatown" exist throughout the world, including Europe, Asia, Africa, O ...

to more upscale neighborhoods which transformed residences into boarding houses or parlor houses otherwise known as brothels occupied by prostitutes. A 1996 archaeological excavation at Union Station