Harry Grindell Matthews on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Harry Grindell Matthews (17 March 1880 – 11 September 1941) was an English inventor who claimed to have invented a death ray in the 1920s.

In 1923, Matthews claimed that he had invented an electric ray that would put

In 1923, Matthews claimed that he had invented an electric ray that would put

Diabolic Rays

, ''Popular Radio'' magazine, New York, Vol. 6, No. 4, August 1924, p. 149-154. In the article, Grindell-Matthews briefly describes the rays and what they can do.

Harry Grindell Matthews website archive

{{DEFAULTSORT:Matthews, Harry Grindell 1941 deaths 1880 births Military personnel from Gloucestershire People from Winterbourne, Gloucestershire English inventors Pseudoscientific physicists British cinema pioneers British military personnel of the Second Boer War

Early life and inventions

Harry Grindell Matthews was born on 17 March 1880 inWinterbourne, Gloucestershire

Winterbourne is a large village and civil parish in the South Gloucestershire district, in the ceremonial county of Gloucestershire, England, lying just beyond the North Fringe of Bristol, north fringe of Bristol.OS Explorer Map, Bristol and Ba ...

. Matthews studied at the Merchant Venturers' School in Bristol and became an electronic engineer. During the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

, Matthews served in the South African Constabulary and was twice wounded.

In 1911, Matthews claimed that he had invented an Aerophone device, a radiotelephone

A radiotelephone (or radiophone), abbreviated RT, is a radio communication system for conducting a conversation; radiotelephony means telephony by radio. It is in contrast to ''radiotelegraphy'', which is radio transmission of telegrams (messag ...

, and transmitted messages between a ground station and an aeroplane from a distance of . His experiments attracted government attention, and on 4 July 1912, Matthews visited Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a royal official residence, residence in London, and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and r ...

. However, when the British Admiralty

The Admiralty was a Departments of the Government of the United Kingdom, department of the Government of the United Kingdom that was responsible for the command of the Royal Navy.

Historically, its titular head was the Lord High Admiral of the ...

requested a demonstration of the Aerophone, Matthews demanded that no experts be present at the scene. When four observers dismantled part of the apparatus before the demonstration began and took notes, Matthews cancelled the demonstration and drove observers away.

Newspapers rushed to Matthews' defence. The War Office denied tampering and claimed the demonstration was a failure. The government later stated that the affair was just a misunderstanding.

In 1914, after the outbreak of the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the British government announced an award of £25,000 to anyone who could create a weapon against zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp. 155� ...

s or remotely control uncrewed vehicles. Matthews claimed he had developed a remote control system using selenium

Selenium is a chemical element; it has symbol (chemistry), symbol Se and atomic number 34. It has various physical appearances, including a brick-red powder, a vitreous black solid, and a grey metallic-looking form. It seldom occurs in this elem ...

cells. Matthews successfully demonstrated it with a remotely controlled boat to representatives of the Admiralty at Richmond Park

Richmond Park, in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, is the largest of Royal Parks of London, London's Royal Parks and is of national and international importance for wildlife conservation. It was created by Charles I of England, Cha ...

's Penn Pond. Matthews received his £25,000, but the Admiralty never used the invention.

Next, Matthews appeared in public in 1921 and claimed to have invented the world's first talking picture, a farewell interview of Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton (15 February 1874 – 5 January 1922) was an Anglo-Irish Antarctic explorer who led three British expeditions to the Antarctic. He was one of the principal figures of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarcti ...

recorded on 16 September 1921, shortly before Shackleton's last expedition. The film was not commercially successful. Other talking-picture processes had been developed before that of Matthews, including processes by William K. L. Dickson, Photokinema

''Photo-Kinema'' (some sources say ''Phono-Kinema'') was a sound-on-disc system for motion pictures invented by Orlando Kellum.

1921 introduction

The system was first used for a small number of short films, mostly made in 1921. These films prese ...

(Orlando Kellum) and Phonofilm

Phonofilm is an optical sound-on-film system developed by inventors Lee de Forest and Theodore Case in the early 1920s.

In 1919 and 1920, de Forest, inventor of the audion tube, filed his first patents on a sound-on-film process, DeForest Phonofi ...

(Lee DeForest). However, Matthews claimed his process was the first sound-on-film

Sound-on-film is a class of sound film processes where the sound accompanying a picture is recorded on photographic film, usually, but not always, the same strip of film carrying the picture. Sound-on-film processes can either record an Analog s ...

.

Death ray

In 1923, Matthews claimed that he had invented an electric ray that would put

In 1923, Matthews claimed that he had invented an electric ray that would put magneto

A magneto is an electrical generator that uses permanent magnets to produce periodic pulses of alternating current. Unlike a dynamo, a magneto does not contain a commutator to produce direct current. It is categorized as a form of alternator, ...

s out of action. In a demonstration to select journalists, Matthews stopped a motorcycle engine from a distance. Matthews also claimed that with enough power it could shoot down aeroplanes, explode gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, charcoal (which is mostly carbon), and potassium nitrate, potassium ni ...

, stop ships, and incapacitate infantry from the distance of . Newspapers obliged by publishing sensational accounts of his invention.

The War Office contacted Matthews in February 1924 to request a demonstration of his ray. Matthews did not reply to them but spoke to journalists and demonstrated the ray to a ''Star'' reporter by igniting gunpowder from a distance. Matthews still refused to say how the ray worked but insisted it did. When the British government still refused to rush to buy his ideas, Matthews announced that he had an offer from France.

The Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force and civil aviation that existed from 1918 to 1964. It was under the political authority of the ...

was wary, partly because of previous bad experiences with would-be inventors. Matthews was invited back to London to demonstrate his ray to the armed forces on 26 April. In Matthews's laboratory, they saw how his ray switched on a light bulb

Electric light is an artificial light source powered by electricity.

Electric Light may also refer to:

* Light fixture, a decorative enclosure for an electric light source

* ''Electric Light'' (album), a 2018 album by James Bay

* Electric Light ( ...

and cut off a motor. Matthews failed to convince the officials, who also suspected trickery or a confidence game. When the British Admiralty requested further demonstration, Matthews refused to give it.

On 27 May 1924, the High Court in London granted an injunction

An injunction is an equitable remedy in the form of a special court order compelling a party to do or refrain from doing certain acts. It was developed by the English courts of equity but its origins go back to Roman law and the equitable rem ...

to Matthew's investors that forbade him from selling the rights to the death ray. When Major Wimperis arrived at Matthews's laboratory to negotiate a new deal, Matthews had already flown to Paris. Matthews's backers also appeared on the scene and rushed to Croydon airport

Croydon Airport was the UK's only international airport during the interwar period. It opened in 1920, located near Croydon, then part of Surrey. Built in a Neoclassical architecture, Neoclassical style, it was developed as Britain's main airp ...

to stop him, but it was too late.

Public furore attracted the interest of other would-be inventors who wanted to demonstrate death rays to the War Office

The War Office has referred to several British government organisations throughout history, all relating to the army. It was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, at ...

. None of them were convincing. On 28 May, Commander Kenworthy asked in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

what the government intended to do to stop Matthews from selling the ray to a foreign power. The Under Secretary for Air answered that Matthews was not willing to let them investigate the ray to their satisfaction. A government representative also stated that one ministry official had stood before the ray and survived. Newspapers continued to root for Matthews.

The government required that Matthews use the ray to stop a petrol motorcycle engine in the conditions that would satisfy the Air Ministry. Matthews would receive £1000 and further consideration. From France, Matthews answered that he was unwilling to give proof of that kind and already had eight bids to choose from. Matthews also claimed that he had lost sight in his left eye because of his experiments. His involvement with his French backer Eugene Royer aroused further suspicions in Britain.

Sir Samuel Instone and his brother Theodore offered Matthews a huge salary if he kept the ray in Britain and demonstrated that it actually worked. Matthews refused again—he did not want to give any proof that the ray worked as he claimed it would.

Matthews returned to London on 1 June 1924 and gave an interview to the ''Sunday Express

The ''Daily Express'' is a national daily United Kingdom middle-market newspaper printed in tabloid format. Published in London, it is the flagship of Express Newspapers, owned by publisher Reach plc. It was first published as a broadsheet ...

''. Matthews claimed that he had a deal with Royer. The press again took his side. The only demonstration Matthews was willing to give was to make a ''Pathé

Pathé SAS (; styled as PATHÉ!) is a French major film production and distribution company, owning a number of cinema chains through its subsidiary Pathé Cinémas and television networks across Europe.

It is the name of a network of Fren ...

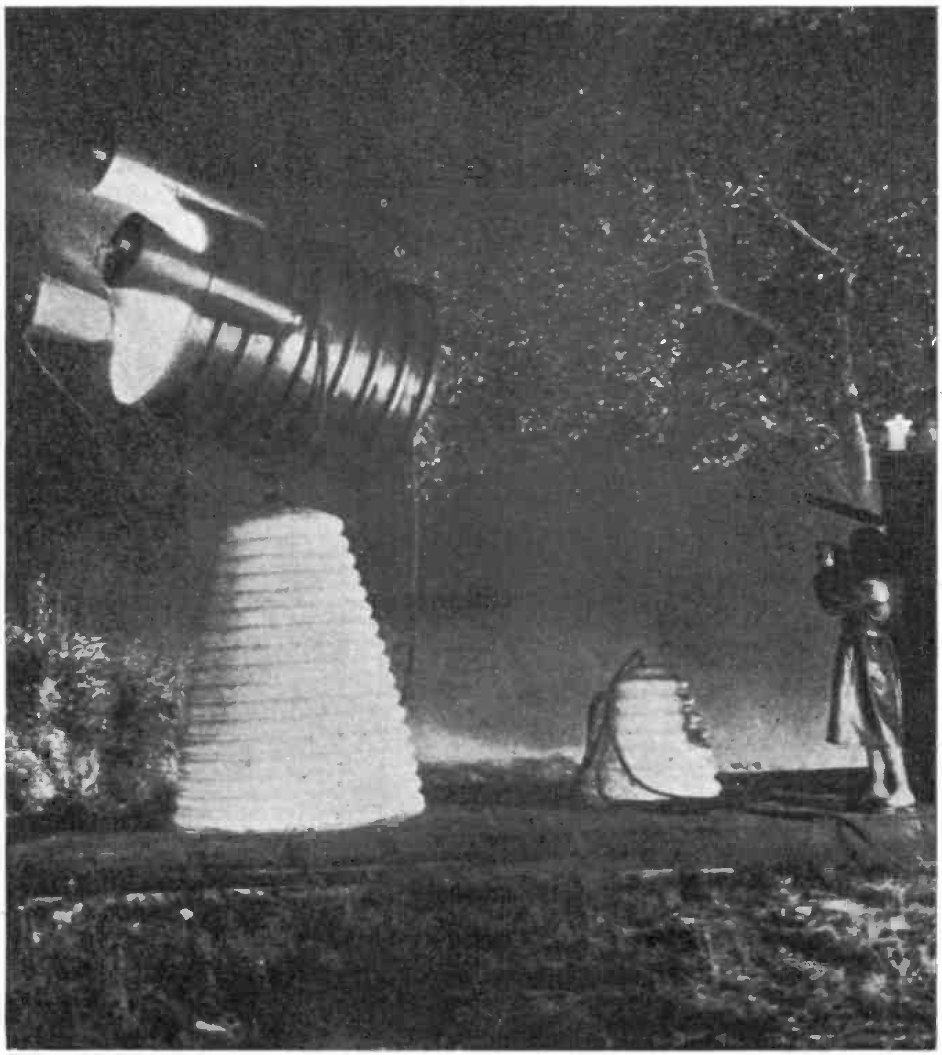

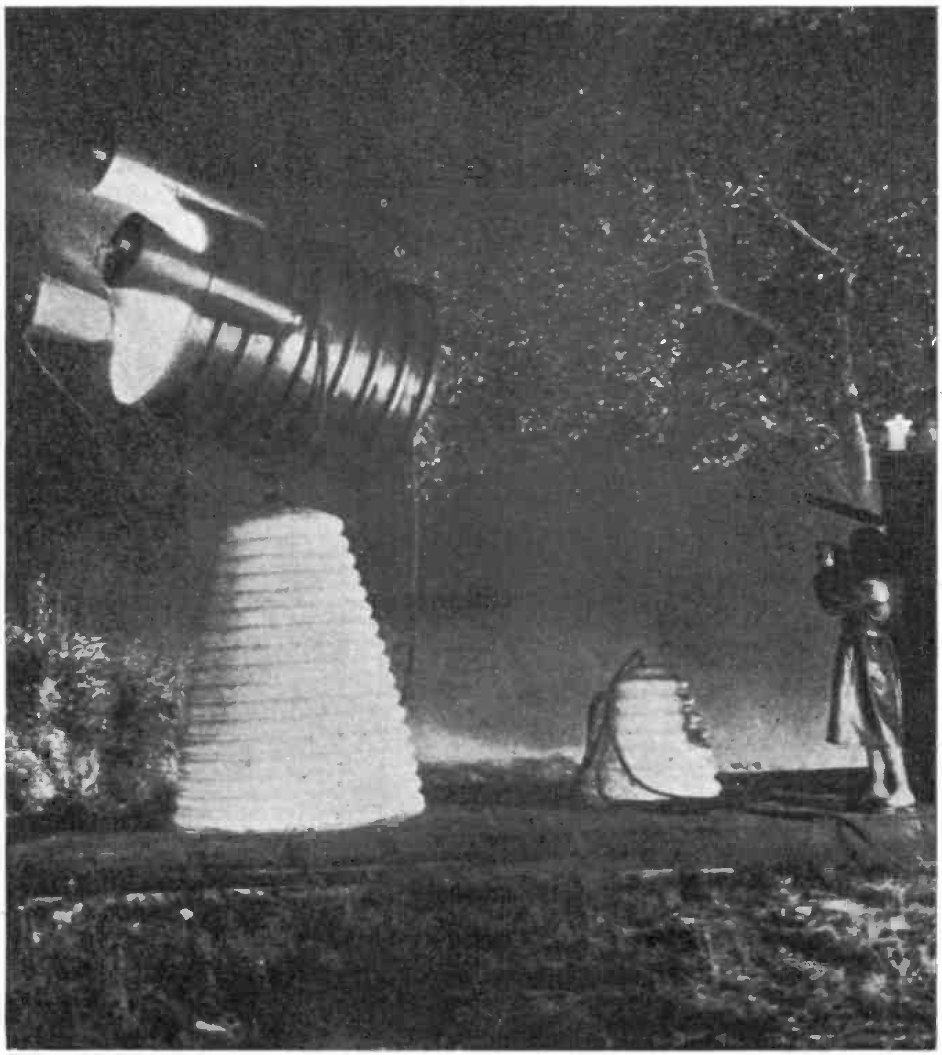

'' film ''The Death Ray'' to propagate his ideas to his satisfaction. The device in the movie bore no resemblance to the one government officials had seen.

In July 1924, Matthews left for the US to market his invention. When Matthews was offered $25,000 to demonstrate his beam to the Radio World Fair at Madison Square Garden

Madison Square Garden, colloquially known as the Garden or by its initials MSG, is a multi-purpose indoor arena in New York City. It is located in Midtown Manhattan between Seventh Avenue (Manhattan), Seventh and Eighth Avenue (Manhattan), Eig ...

, he again refused and claimed, without foundation, that he was not permitted to demonstrate it outside England. US scientists were not impressed. One Professor Woods offered to stand before the death ray device to demonstrate his disbelief. Regardless, when Matthews returned to Britain, he claimed that the USA had bought his ray but refused to say who had done it and for how much. Matthews moved to the US and began to work for Warner Bros.

Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. (WBEI), commonly known as Warner Bros. (WB), is an American filmed entertainment studio headquartered at the Warner Bros. Studios complex in Burbank, California and the main namesake subsidiary of Warner Bro ...

Further inventions

In 1925, Matthews invented what he called the "luminaphone". On 24 December 1930, Matthews was back in England with his new creation – a Sky Projector that projected pictures onto clouds. Matthews demonstrated it inHampstead

Hampstead () is an area in London, England, which lies northwest of Charing Cross, located mainly in the London Borough of Camden, with a small part in the London Borough of Barnet. It borders Highgate and Golders Green to the north, Belsiz ...

by projecting an angel, the message "Happy Christmas", and a reportedly "accurate" clock face. Matthews demonstrated it again in New York. This invention was unsuccessful, and by 1931, Matthews faced bankruptcy. Matthews used most of his investors' money to live in expensive hotels.

In 1934, Matthews had a new set of investors and relocated to Tor Clawdd, Betws, South Wales

South Wales ( ) is a Regions of Wales, loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the Historic counties of Wales, historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire ( ...

. Matthews built a fortified laboratory and airfield. In 1935, Matthews claimed that he worked on aerial mines and, in 1937, invented a system for detecting submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

s. In 1938, Matthews married Ganna Walska, a Polish-American opera singer, perfumer, and feminist, whose four previous husbands had owned fortunes totalling $125,000,000.

In 1935, Matthews became involved with the left-wing Lucy (fascist supporter), Lady Houston, and intended to conduct experiments in French naval submarine detection from her luxury yacht, the ''Liberty''. In 2010, new research chronicled the episode, explaining how Matthews was frustrated in carrying out his aims.

Later, Matthews propagated the idea of the "stratoplane" and joined the British Interplanetary Society

The British Interplanetary Society (BIS), founded in Liverpool in 1933 by Philip E. Cleator, is the oldest existing space advocacy organisation in the world. Its aim is exclusively to support and promote astronautics and space exploration.

St ...

. His reputation preceded him, and the British Government was no longer interested in his ideas.

Personal life

Harry Grindell Matthews was the fifth husband of singer Ganna Walska; they married in 1938. Matthews died of a heart attack on 11 September 1941.See also

* Samuel Alfred Warner – a purported inventor of naval weapons in the first half of the 19th century.References

External links

* * *H. Grindell-Matthews,Diabolic Rays

, ''Popular Radio'' magazine, New York, Vol. 6, No. 4, August 1924, p. 149-154. In the article, Grindell-Matthews briefly describes the rays and what they can do.

Harry Grindell Matthews website archive

{{DEFAULTSORT:Matthews, Harry Grindell 1941 deaths 1880 births Military personnel from Gloucestershire People from Winterbourne, Gloucestershire English inventors Pseudoscientific physicists British cinema pioneers British military personnel of the Second Boer War