Hindu nationalism has been collectively referred to as the expression of political thought, based on the native social and cultural traditions of the

Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographic region of Asia below the Himalayas which projects into the Indian Ocean between the Bay of Bengal to the east and the Arabian Sea to the west. It is now divided between Bangladesh, India, and Pakista ...

. "Hindu nationalism" is a simplistic translation of . It is better described as "Hindu polity".

The native thought streams became highly relevant in Indian history when they helped form a distinctive identity about the Indian polity

[Chatterjee Partha (1986)] and provided a basis for questioning colonialism.

[Peter van der Veer, Hartmut Lehmann, Nation and religion: perspectives on Europe and Asia, Princeton University Press, 1999 p. 90] These also inspired

Indian nationalists during the

independence movement based on armed struggle,

[Li Narangoa, R. B. Cribb ''Imperial Japan and National Identities in Asia'', 1895–1945, Published by Routledge, 2003 p. 78] coercive politics,

[Bhatt, Chetan, ''Hindu Nationalism: Origins, Ideologies and Modern Myths'', Berg Publishers (2001), . P. 55] and non-violent protests.

They also influenced social reform movements and economic thinking in India.

[

Today, ]Hindutva

Hindutva (; ) is a Far-right politics, far-right political ideology encompassing the cultural justification of Hindu nationalism and the belief in establishing Hindu hegemony within India. The political ideology was formulated by Vinayak Da ...

(meaning ) is the dominant form of Hindu nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

politics in India. As a political ideology, the term Hindutva was articulated by Vinayak Damodar Savarkar

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar (28 May 1883 – 26 February 1966 ), was an Indian politician, activist and writer. Savarkar developed the Hindu nationalist political ideology of Hindutva while confined at Ratnagiri in 1922. The prefix "Veer" (mea ...

in 1923.fascist

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural soci ...

in the classical sense", adhering to a concept of homogenised majority and cultural hegemony

In Marxist philosophy, cultural hegemony is the dominance of a culturally diverse society by the ruling class who shape the culture of that society—the beliefs and explanations, perceptions, values, and mores—so that the worldview of the rul ...

. Some analysts dispute the "fascist" label, and suggest Hindutva is an extreme form of "conservatism

Conservatism is a Philosophy of culture, cultural, Social philosophy, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, Convention (norm), customs, and Value (ethics and social science ...

" or "ethnic absolutism". Some have also described Hindutva as a separatist ideology.Bharatiya Janata Party

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP; , ) is a political party in India and one of the two major List of political parties in India, Indian political parties alongside the Indian National Congress. BJP emerged out from Syama Prasad Mukherjee's ...

(BJP), the Hindu Nationalist volunteer organisation Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS,, ) is an Indian right-wing politics, right-wing, Hindutva, Hindu nationalist volunteer paramilitary organisation. It is the progenitor and leader of a large body of organisations called the Sangh Parivar ( ...

(RSS), Sanatan Sanstha,Vishva Hindu Parishad

Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP) () is an Indian Right-wing politics, right-wing Hindu organisation based on Hindutva, Hindu nationalism. The VHP was founded in 1964 by M. S. Golwalkar and S. S. Apte in collaboration with Chinmayananda Saraswati, ...

(VHP), and other organisations in an ecosystem called the Sangh Parivar.

Evolution of ideological terminology and influences

In the first half of the 20th century, factions of Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

continued to be identified with "Hindu politics" and ideas of a Hindu nation.[

The word "Hindu", throughout history, had been used as an inclusive description that lacked a definition and was used to refer to the native traditions and people of India. It was only in the late 18th century that the word "Hindu" came to be used extensively with religious connotation, while still being used as a ]synecdoche

Synecdoche ( ) is a type of metonymy; it is a figure of speech that uses a term for a part of something to refer to the whole (''pars pro toto''), or vice versa (''totum pro parte''). The term is derived . Common English synecdoches include '' ...

describing the indigenous traditions. Hindu nationalist ideologies and political languages were very diverse both linguistically and socially. Since Hinduism does not represent an identifiable religious group, terms such as 'Hindu nationalism', and 'Hindu', are considered problematic in the case of religious and nationalism discourse. As Hindus were identifiable as a homogeneous community, some individual Congress leaders were able to induce a symbolism with "Hindu" meaning inside the general stance of secular nationalism.[On Understanding Islam: Selected Studies, By Wilfred Cantwell Smith, Published by Walter de Gruyter, 1981, ]

The diversity of Indian cultural groups and moderate positions of Hindu nationalism have sometimes made it regarded as cultural nationalism rather than a religious one.

Shivaji

Shivaji I (Shivaji Shahaji Bhonsale, ; 19 February 1630 – 3 April 1680) was an Indian ruler and a member of the Bhonsle dynasty. Shivaji carved out his own independent kingdom from the Sultanate of Bijapur that formed the genesis of the ...

and his conquests are said to have served basis for Hindu nationalism. Hindutva creator Vinayak Damodar Savarkar

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar (28 May 1883 – 26 February 1966 ), was an Indian politician, activist and writer. Savarkar developed the Hindu nationalist political ideology of Hindutva while confined at Ratnagiri in 1922. The prefix "Veer" (mea ...

writes that Shivaji had 'electrified' minds of the Hindus all over India by defeating the forces of the Mughals.

Nepali Hindu nationalism and practices

Hinduization policy of the Gorkhali monarch

Maharajadhiraja

Maharajadhiraja Prithvi Narayan Shah

Prithvi Narayan Shah (; 7 January 1723 – 11 January 1775), was the last king of the Gorkha Kingdom and first king of the Kingdom of Nepal (also called the ''Kingdom of Gorkha''). Prithvi Narayan Shah started the unification of Nepal. He is a ...

proclaimed the newly unified Kingdom of Nepal

The Kingdom of Nepal was a Hindu monarchy in South Asia, founded in 1768 through the unification of Nepal, expansion of the Gorkha Kingdom. The kingdom was also known as the Gorkha Empire and was sometimes called History of Asal Hindustan, ...

as ''Asal Hindustan

''Hindūstān'' ( English: /ˈhɪndustæn/ or /ˈhɪndustɑn/, ; ) was a historical region, polity, and a name for India, historically used simultaneously for northern Indian subcontinent and the entire subcontinent, used in the modern day ...

'' ("Real Land of Hindus") because North India was ruled by the Islamic

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

Mughal rulers. The proclamation was made to enforce the Hindu social code Dharmaśāstra

''Dharmaśāstra'' () are Sanskrit Puranic Smriti texts on law and conduct, and refer to treatises (shastras, śāstras) on Dharma. Like Dharmasūtra which are based upon Vedas, these texts are also elaborate law commentaries based on vedas, D ...

over his reign and refer to his country as being inhabitable for Hindus

Hindus (; ; also known as Sanātanīs) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism, also known by its endonym Sanātana Dharma. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pp. 35–37 Historically, the term has also be ...

. He also referred to the rest of Northern India as ''Mughlan'' (Country of Mughals

The Mughal Empire was an early modern empire in South Asia. At its peak, the empire stretched from the outer fringes of the Indus River Basin in the west, northern Afghanistan in the northwest, and Kashmir in the north, to the highlands of pre ...

) and called the region infiltrated by Muslim foreigners. After the Gorkhali conquest of the Kathmandu valley

The Kathmandu Valley (), also known as the Nepal Valley or Nepa Valley (, Newar language, Nepal Bhasa: 𑐣𑐾𑐥𑐵𑑅 𑐐𑐵𑑅, नेपाः गाः), National Capital Area, is a bowl-shaped valley located in the Himalayas, Hima ...

, King Prithvi Narayan Shah expelled Christian Capuchin missionaries from Patan and renamed Nepal as ''Asali Hindustan

''Hindūstān'' ( English: /ˈhɪndustæn/ or /ˈhɪndustɑn/, ; ) was a historical region, polity, and a name for India, historically used simultaneously for northern Indian subcontinent and the entire subcontinent, used in the modern day ...

'' (the real land of Hindus

Hindus (; ; also known as Sanātanīs) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism, also known by its endonym Sanātana Dharma. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pp. 35–37 Historically, the term has also be ...

).Tagadhari

''Tagadhari'' () are members of a Nepalis, Nepalese Hindu group that is perceived as historically having a high socio-religious status in society. Tagadhari are identified by a ''sacred thread'' (Janai) around the torso, which is used for ritual ...

s enjoyed a privileged status in the Nepalese capital and they were also given greater access to the authorities after these events. Subsequently, Hinduisation became the main policy of the Kingdom of Nepal

The Kingdom of Nepal was a Hindu monarchy in South Asia, founded in 1768 through the unification of Nepal, expansion of the Gorkha Kingdom. The kingdom was also known as the Gorkha Empire and was sometimes called History of Asal Hindustan, ...

.Kingdom of Nepal

The Kingdom of Nepal was a Hindu monarchy in South Asia, founded in 1768 through the unification of Nepal, expansion of the Gorkha Kingdom. The kingdom was also known as the Gorkha Empire and was sometimes called History of Asal Hindustan, ...

, to build a haven for Hindus there.

Ideals of the Bharadari government

The policies of the old Bharadari governments of the Gorkha Kingdom were derived from ancient Hindu

Hindus (; ; also known as Sanātanīs) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism, also known by its endonym Sanātana Dharma. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pp. 35–37 Historically, the term has also be ...

texts such as the Dharmashastra The King was considered an incarnation of Lord Vishnu

Vishnu (; , , ), also known as Narayana and Hari, is one of the Hindu deities, principal deities of Hinduism. He is the supreme being within Vaishnavism, one of the major traditions within contemporary Hinduism, and the god of preservation ( ...

and was the chief authority over legislative, judiciary and executive functions. The judiciary functions were decided based on the principles of Hindu Dharma codes of conduct. The king had full rights to expel any person who offended the country and also to pardon the offenders and grant their return to the country. The government in practicality was not an absolute monarchy due to the dominance of Nepalese political clans such as the Pande family and the Thapa family, making the Shah monarch a puppet ruler. These basic Hindu templates provide the evidence that Nepal was administered as a Hindu

Hindus (; ; also known as Sanātanīs) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism, also known by its endonym Sanātana Dharma. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pp. 35–37 Historically, the term has also be ...

state.

Hindu civil code and legal regulations

The Nepali

The Nepali civil code

A civil code is a codification of private law relating to property law, property, family law, family, and law of obligations, obligations.

A jurisdiction that has a civil code generally also has a code of civil procedure. In some jurisdiction ...

, '' Muluki Ain'', was commissioned by Jung Bahadur Rana after his European tour and enacted in 1854. It was rooted in traditional Hindu Law

Hindu law, as a historical term, refers to the code of laws applied to Hindus, Buddhists, Jains and Sikhs in British India. Hindu law, in modern scholarship, also refers to the legal theory, jurisprudence and philosophical reflections on the na ...

and codified social practices for several centuries in Nepal. The law also comprised ''Prāyaścitta

''Prāyaścitta'' () is the Sanskrit word which means "atonement, penance, expiation". In Hinduism, it is a ''dharma''-related term and refers to voluntarily accepting one's errors and misdeeds, confession, repentance, means of penance and expiat ...

'' (avoidance and removal of sin) and '' Ācāra'' (the customary law of different communities). It was an attempt to include the entire Hindu as well as the non-Hindu population of Nepal of that time into a single hierarchic civic code from the perspective of the Khas

Khas peoples or Khas Tribes, (; ) popularly known as Khashiya are an Indo-Aryan ethno-linguistic group native to the Himalayan region of the Indian subcontinent, in what is now the South Asian country of Nepal, as well as the Indian stat ...

rulers. The Nepalese ''jati'' arrangement in terms of Hindu

Hindus (; ; also known as Sanātanīs) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism, also known by its endonym Sanātana Dharma. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pp. 35–37 Historically, the term has also be ...

Varnashrama takes the Tagadhari to be the highest in the hierarchy. The ethnolinguistic group of people of Tamang, Sherpa and Tharu origin were tagged under the title ''Matwali'' ("Liquor Drinkers"), while those of Khas

Khas peoples or Khas Tribes, (; ) popularly known as Khashiya are an Indo-Aryan ethno-linguistic group native to the Himalayan region of the Indian subcontinent, in what is now the South Asian country of Nepal, as well as the Indian stat ...

, Newari and Terai

The Terai or Tarai is a lowland region in parts of southern Nepal and northern India that lies to the south of the outer foothills of the Himalayas, the Sivalik Hills and north of the Indo-Gangetic Plain.

This lowland belt is characterised by ...

origin were termed ''Tagadhari'' ("Wearers of the Sacred Thread"). The Tagadhari castes could not be enslaved following any criminal punishment unless they had been expelled from the caste. The main broad caste categories in Nepal are ''Tagadharis'' (sacred thread bearers), ''Matwalis'' (liquor drinkers) and ''Dalit

Dalit ( from meaning "broken/scattered") is a term used for untouchables and outcasts, who represented the lowest stratum of the castes in the Indian subcontinent. They are also called Harijans. Dalits were excluded from the fourfold var ...

s'' (or untouchables).

Modern age and the Hindu Renaissance in the 19th century

Many Hindu reform movements originated in the nineteenth century. These movements led to fresh interpretations of the ancient scriptures of Upanishads and Vedanta

''Vedanta'' (; , ), also known as ''Uttara Mīmāṃsā'', is one of the six orthodox (Āstika and nāstika, ''āstika'') traditions of Hindu philosophy and textual exegesis. The word ''Vedanta'' means 'conclusion of the Vedas', and encompa ...

and also emphasised on social reform.[ The marked feature of these movements was that they countered the notion of the superiority of ]Western culture

Western culture, also known as Western civilization, European civilization, Occidental culture, Western society, or simply the West, refers to the Cultural heritage, internally diverse culture of the Western world. The term "Western" encompas ...

during the colonial era. This led to the upsurge of patriotic ideas that formed the cultural and ideological basis for the independence movement in Colonial India.[

]

Brahmo Samaj

The Brahmo Samaj was started by a Bengali scholar, Ram Mohan Roy in 1828. Ram Mohan Roy endeavoured to create from the ancient Upanishadic texts, a vision of rationalist 'modern' India. Socially, he criticized the ongoing superstitions, and believed in a monotheistic Vedic religion. His major emphasis was social reform. He fought against Caste discrimination and advocated equal rights for women. Although the Brahmos found favourable responses from the British government

His Majesty's Government, abbreviated to HM Government or otherwise UK Government, is the central government, central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. and Westernized Indians, they were largely isolated from the larger Hindu society due to their intellectual Vedantic and Unitarian views. However their efforts to systematise Hindu spirituality based on rational and logical interpretation of the ancient Indian texts would be carried forward by other movements in Bengal and across India.

Arya Samaj

Arya Samaj

Arya Samaj () is a monotheistic Indian Hindu reform movement that promotes values and practices based on the belief in the infallible authority of the Vedas. Dayananda Saraswati founded the samaj in the 1870s.

Arya Samaj was the first Hindu ...

is considered one of the overarching Hindu renaissance movements of the late nineteenth century. Swami Dayananda, the founder of Arya Samaj, rejected idolatry, caste restriction and untouchability, child marriage and advocated equal status and opportunities for women. He opposed "Brahmanism" (which he believed had led to the corruption of the knowledge of Vedas) as much as he opposed Christianity and Islam.[ Although Arya Samaj was often considered as a social movement, many revolutionaries and political leaders of the ]Indian Independence movement

The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events in South Asia with the ultimate aim of ending British Raj, British colonial rule. It lasted until 1947, when the Indian Independence Act 1947 was passed.

The first nationalistic ...

like Ramprasad Bismil, Bhagat Singh, Shyamji Krishnavarma, Bhai Paramanand and Lala Lajpat Rai were inspired by it.

Swami Vivekananda

Another 19th-century Hindu reformer was

Another 19th-century Hindu reformer was Swami Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda () (12 January 1863 – 4 July 1902), born Narendranath Datta, was an Indian Hindus, Hindu monk, philosopher, author, religious teacher, and the chief disciple of the Indian mystic Ramakrishna. Vivekananda was a major figu ...

. Vivekananda as a student was educated in contemporary Western thought

Western philosophy refers to the philosophical thought, traditions and works of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the pre-Socratics. ...

.[ He joined Brahmo Samaj briefly before meeting Ramakrishna, who was a priest in the temple of the goddess ]Kali

Kali (; , ), also called Kalika, is a major goddess in Hinduism, primarily associated with time, death and destruction. Kali is also connected with transcendental knowledge and is the first of the ten Mahavidyas, a group of goddesses who p ...

in Calcutta and who was to become his guru.[ Under the influence of ]Orientalism

In art history, literature, and cultural studies, Orientalism is the imitation or depiction of aspects of the Eastern world (or "Orient") by writers, designers, and artists from the Western world. Orientalist painting, particularly of the Middle ...

, Perennialism and Universalism

Universalism is the philosophical and theological concept within Christianity that some ideas have universal application or applicability.

A belief in one fundamental truth is another important tenet in universalism. The living truth is se ...

, Vivekananda re-interpreted Advaita Vedanta, presenting it as the essence of Hindu spirituality, and the development of human's religiosity. This project started with Ram Mohan Roy of Brahmo Samaj, who collaborated with the Unitarian Church, and propagated a strict monotheism. This reinterpretation produced neo-Vedanta

Neo-Vedanta, also called neo-Hinduism, Hindu modernism, Global Hinduism and Hindu Universalism, are terms to characterize interpretations of Hinduism that developed in the 19th century. The term "Neo-Vedanta" was coined by German Indologist ...

, in which Advaita Vedanta was combined with disciplines such as yoga

Yoga (UK: , US: ; 'yoga' ; ) is a group of physical, mental, and spiritual practices or disciplines that originated with its own philosophy in ancient India, aimed at controlling body and mind to attain various salvation goals, as pra ...

and the concept of social service to attain perfection from the ascetic traditions in what Vivekananda called the "practical Vedanta". The practical side essentially included participation in social reform.[

He made Hindu spirituality, intellectually available to the Westernized audience. His famous speech in the ]Parliament of the World's Religions

There have been several meetings referred to as a Parliament of the World's Religions, the first being the World's Parliament of Religions of 1893, which was an attempt to create a global dialogue of faiths. The event was celebrated by another c ...

at Chicago on 11 September 1893, followed a huge reception of his thought in the West and made him a well-known figure in the West and subsequently in India too.[ His influence can still be recognised in popular Western ]spirituality

The meaning of ''spirituality'' has developed and expanded over time, and various meanings can be found alongside each other. Traditionally, spirituality referred to a religious process of re-formation which "aims to recover the original shape o ...

, such as nondualism, New Age

New Age is a range of Spirituality, spiritual or Religion, religious practices and beliefs that rapidly grew in Western world, Western society during the early 1970s. Its highly eclecticism, eclectic and unsystematic structure makes a precise d ...

and the veneration of Ramana Maharshi

Ramana Maharshi (; ; 30 December 1879 – 14 April 1950) was an Indian Hindu Sage (philosophy), sage and ''jivanmukta'' (liberated being). He was born Venkataraman Iyer, but is mostly known by the name Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi.

He was b ...

.

A major element of Vivekananda's message was nationalism. He saw his effort very much in terms of a revitalisation of the Hindu nation, which carried Hindu spirituality and which could counter Western materialism. The notions of the superiority of Western culture

Western culture, also known as Western civilization, European civilization, Occidental culture, Western society, or simply the West, refers to the Cultural heritage, internally diverse culture of the Western world. The term "Western" encompas ...

against the culture of India

Indian culture is the cultural heritage, heritage of social norms and history of science and technology on the Indian subcontinent, technologies that originated in or are associated with the ethno-linguistically diverse nation of India, pert ...

, were to be questioned based on Hindu spirituality. It also became a main inspiration for Hindu nationalism today.[ "Vivekananda is like Gita for the RSS" was the lifelong pet sentence of one of the most revered leaders of the ]Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS,, ) is an Indian right-wing politics, right-wing, Hindutva, Hindu nationalist volunteer paramilitary organisation. It is the progenitor and leader of a large body of organisations called the Sangh Parivar ( ...

(RSS), Babasaheb Apte. Some historians have observed that this helped the nascent Independence movement with a distinct national identity and kept it from being the simple derivative function of European nationalism.[

]

Shaping of Hindu Polity & Nationalism in the 20th century

Sri Aurobindo

Sri Aurobindo

Sri Aurobindo (born Aurobindo Ghose; 15 August 1872 – 5 December 1950) was an Indian Modern yoga gurus, yogi, maharishi, and Indian nationalist. He also edited the newspaper Bande Mataram (publication), ''Bande Mataram''.

Aurobindo st ...

was a nationalist and one of the first to embrace the idea of complete political independence for India. He was inspired by the writings of Swami Vivekananda and the novels of Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay.[William Theodore De Bary, Stephen N Hay, Sources of Indian Tradition, Published by Motilal Banarsidass Publisher, 1988, ] He "based his claim for freedom for India on the inherent right to freedom, not on any charge of misgovernment or oppression". He believed that the primary requisite for national progress, national reform, is the free habit of free and healthy national thought and action and that it was impossible in a state of servitude.[Peter Heehs, Religious nationalism and beyond, August 2004] He was part of the '' Anushilan Samiti'', a revolutionary group working towards the goal of Indian independence In his brief political career spanning only four years, he led a delegation from Bengal to the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

session of 1907[ and contributed to the revolutionary newspaper Bande Mataram.

In his famous ''Uttarpara Speech'', he outlined the essence and the goal of India's nationalist movement thus:

In the same speech, he also gave a comprehensive perspective of Hinduism, which is at variance with the geocentric view developed by the later day Hindu nationalist ideologues such as Veer Savarkar and Deendayal Upadhyay:

In 1910, he withdrew from political life and spent his remaining life doing spiritual exercises and writing.][ But his works kept inspiring revolutionaries and struggles for independence, including the famous Chittagong Uprising. Both Swami Vivekananda and Sri Aurobindo are credited with having founded the basis for a vision of freedom and glory for India in the spirituality and heritage of Hinduism.

]

Independence movement

In 1924, Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

wrote:

The influence of the Hindu renaissance movements was such that by the turn of the 20th century, there was a confluence of ideas of Hindu cultural nationalism with the ideas of Indian nationalism.[ Both could be spoken synonymously even by tendencies that were seemingly opposed to sectarian communalism and Hindu majoritism.][ The Hindu renaissance movements held considerable influence over the revolutionary movements against British rule and formed the philosophical basis for the struggles and political movements that originated in the first decade of the twentieth century.

]

Revolutionary movements

Anushilan Samiti and Jugantar

Anushilan Samiti was one of the prominent revolutionary movements in India in the early part of the twentieth century. It was started as a cultural society in 1902, by Aurobindo and the followers of Bankim Chandra to propagate the teachings of the Bhagavad Gita

The Bhagavad Gita (; ), often referred to as the Gita (), is a Hindu texts, Hindu scripture, dated to the second or first century BCE, which forms part of the Hindu epic, epic poem Mahabharata. The Gita is a synthesis of various strands of Ind ...

. But soon the Samiti had its goal to overthrow British colonial rule in India[ Various branches of the Samiti sprung across India in the guise of suburban fitness clubs but secretly imparted arms training to its members with the implicit aim of using them against the British colonial administration.][By J. C. Johari, Voices of Indian Freedom Movement, Published by Akashdeep Pub. House]

On 30 April 1908 at Muzaffarpur, two revolutionaries, Khudiram Bose and Prafulla Chaki, threw bombs at a British convoy aimed at British officer Kingsford. Both were arrested trying to flee. Aurobindo was also arrested on 2 May 1908 and sent to Alipore Jail. The report sent from Andrew Fraser, the then Lt Governor of Bengal to Lord Minto in England declared that although Sri Aurobindo came to Calcutta in 1906 as a Professor at the National College, "he has ever since been the principal advisor of the revolutionary party. It is of utmost importance to arrest his potential for mischief, for he is the prime mover and can easily set tools, one to replace another". But charges against Aurobindo were never proved and he was acquitted. Many members of the group faced charges and were transported and imprisoned for life. Others went into hiding.[Arun Chandra Guha Aurobindo and Jugantar, Published by Sahitya Sansad, 1970]

In 1910, when, Aurobindo withdrew from political life and decided to live a life of renounciate,[ the Anushilan Samiti declined. One of the revolutionaries, Bagha Jatin, who managed to escape the trial started a group which would be called Jugantar. Jugantar continued with its armed struggle against the colonial government, but the arrests of its key members and subsequent trials weakened its influence. Many of its members were imprisoned for life in the notorious Andaman Cellular jail.][

]

India House

A revolutionary movement was started by Shyamji Krishnavarma, a Sanskritist and an Arya Samajist, in London, under the name of India House in 1905. The brain behind this movement was said to be V D Savarkar. Krishnaverma also published a monthly "''Indian Sociologist''", where the idea of an armed struggle against the British colonial government was openly espoused.[Anthony Parel, Hind Swaraj and other writings By Gandhi, Published by Cambridge University Press, 1997, ] The movement had become well known for its activities in the Indian expatriates in London. When Gandhi visited London in 1909, he shared a platform with the revolutionaries where both the parties politely agreed to disagree, on the question of adopting a violent struggle and whether Ramayana

The ''Ramayana'' (; ), also known as ''Valmiki Ramayana'', as traditionally attributed to Valmiki, is a smriti text (also described as a Sanskrit literature, Sanskrit Indian epic poetry, epic) from ancient India, one of the two important epics ...

justified such violence. Gandhi, while admiring the "patriotism" of the young revolutionaries, had "dissented vociferously" from their "violent blueprints" for social change. In turn, the revolutionaries disliked his adherence to constitutionalism

Constitutionalism is "a compound of ideas, attitudes, and patterns of behavior elaborating the principle that the authority of government derives from and is limited by a body of fundamental law".

Political organizations are constitutional to ...

and his close contacts with moderate leaders of the Indian National Congress. Moreover, they considered his method of "passive resistance" effeminate and humiliating.

The India House was soon to face closure following the assassination of William Hutt Curzon Wyllie by the revolutionary Madan Lal Dhingra, who was close to India House. Savarkar also faced charges and was transported. Shyamji Krishna Varma fled to Paris.[ India House gave formative support to ideas that were later formulated by Savarkar in his book named ']Hindutva

Hindutva (; ) is a Far-right politics, far-right political ideology encompassing the cultural justification of Hindu nationalism and the belief in establishing Hindu hegemony within India. The political ideology was formulated by Vinayak Da ...

'. Hindutva was to gain relevance in the run-up to the Indian Independence and form the core ideology of the political party Hindu Mahasabha

Akhil Bharatiya Hindu Mahasabha (), simply known as Hindu Mahasabha, is a Hindu nationalism, Hindu nationalist political party in India.

Founded in 1915 by Madan Mohan Malviya, the Mahasabha functioned mainly as a pressure group advocating th ...

, of which Savarkar became president in 1937. It also formed the key ideology, under the euphemistic relabelling ''Rashtriyatva'' (nationalism), for the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS,, ) is an Indian right-wing politics, right-wing, Hindutva, Hindu nationalist volunteer paramilitary organisation. It is the progenitor and leader of a large body of organisations called the Sangh Parivar ( ...

founded in 1925, and of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh

The Akhil Bharatiya Jana Sangh ( BJS or JS, short name: Jan Sangh) was a Hindutva political party active in India. It was established on 21 October 1951 in Delhi by three founding members: Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, Balraj Madhok and Deendayal ...

(the present-day ruling Bharatiya Janata Party

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP; , ) is a political party in India and one of the two major List of political parties in India, Indian political parties alongside the Indian National Congress. BJP emerged out from Syama Prasad Mukherjee's ...

) under another euphemistic relabelling ''Bharatiyata'' (Indianness).

Indian National Congress

Lal-Bal-Pal

" Lal-Bal-Pal" is the phrase that is used to refer to the three nationalist leaders Lala Lajpat Rai,

" Lal-Bal-Pal" is the phrase that is used to refer to the three nationalist leaders Lala Lajpat Rai, Bal Gangadhar Tilak

Bal Gangadhar Tilak (; born Keshav Gangadhar Tilak (pronunciation: eʃəʋ ɡəŋɡaːd̪ʱəɾ ʈiɭək; 23 July 1856 – 1 August 1920), endeared as Lokmanya (IAST: ''Lokamānya''), was an Indian nationalist, teacher, and an independence ...

and Bipin Chandra Pal who held sway over the Indian Nationalist movement and the independence struggle in the early parts of twentieth century.

Lala Lajpat Rai belonged to the northern province of Punjab. He was influenced greatly by the Arya Samaj and was part of the Hindu reform movement.Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

in 1888 and became a prominent figure in the Indian Independence Movement.[Lajpat Rai, Bal Ram Nanda, ''The Collected Works of Lala Lajpat Rai'', Published by Manohar, 2005, ] He started numerous educational institutions. The National College at Lahore

Lahore ( ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Administrative units of Pakistan, Pakistani province of Punjab, Pakistan, Punjab. It is the List of cities in Pakistan by population, second-largest city in Pakistan, after Karachi, and ...

started by him became the centre for revolutionary ideas and was the college where revolutionaries like Bhagat Singh studied. While leading a procession against the Simon Commission

The Indian Statutory Commission, also known as the Simon Commission, was a group of seven members of the British Parliament under the chairmanship of John Simon. The commission arrived in the Indian subcontinent in 1928 to study constitutional ...

, he was fatally injured in the lathi charge. His death led revolutionaries like Chandrashekar Azad and Bhagat Singh to assassinate the British police officer J. P. Saunders, who they believed was responsible for the death of Lala Lajpat Rai.Bal Gangadhar Tilak

Bal Gangadhar Tilak (; born Keshav Gangadhar Tilak (pronunciation: eʃəʋ ɡəŋɡaːd̪ʱəɾ ʈiɭək; 23 July 1856 – 1 August 1920), endeared as Lokmanya (IAST: ''Lokamānya''), was an Indian nationalist, teacher, and an independence ...

was a nationalist leader from the Central Indian province of Maharashtra. He has been widely acclaimed the "Father of Indian unrest" who used the press and Hindu occasions like Ganesh Chaturthi and symbols like the Cow to create unrest against the British administration in India. Tilak joined the Indian National Congress in 1890. Under the influence of such leaders, the political discourse of the Congress moved from the polite accusation that colonial rule was "un-British" to the forthright claim of Tilak that "Swaraj is my birthright and I will have it".

Bipin Chandra Pal of Bengal was another prominent figure of the Indian nationalist movement, who is considered a modern Hindu reformer, who stood for Hindu cultural nationalism and was opposed to sectarian communalism and Hindu majoritism.Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

in 1886 and was also one of the key members of the revolutionary India House.

Gandhi and Rāmarājya

Though

Though Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

never called himself a "Hindu nationalist"; he believed in and propagated concepts like Dharma

Dharma (; , ) is a key concept in various Indian religions. The term ''dharma'' does not have a single, clear Untranslatability, translation and conveys a multifaceted idea. Etymologically, it comes from the Sanskrit ''dhr-'', meaning ''to hold ...

and introduced the concept of the "Rāma Rājya" (Rule of Lord Rāma) as part of his social and political philosophy. Gandhi said "By political independence I do not mean an imitation to the British House of commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the upper house, the House of Lords, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. The House of Commons is an elected body consisting of 650 memb ...

, or the soviet rule of Russia or the Fascist rule of Italy or the Nazi rule of Germany. They have systems suited to their genius. We must have ours suited to ours. What that can be is more than I can tell. I have described it as Ramarajya i.e., sovereignty of the people based on pure moral authority."

Gandhi emphasised that "Rāma Rājya" to him meant peace and justice, adding that "the ancient ideal of Ramarajya is undoubtedly one of true democracy in which the meanest citizen could be sure of swift justice without an elaborate and costly procedure". He also emphasised that it meant respect for all religions: "My Hinduism teaches me to respect all religions. In this lies the secret of Ramarajya".

While Gandhi had clarified that "by Ram Rajya I do not mean Hindu Raj. I mean by Ram Rajya, Divine Raj, the kingdom of God," his concept of "Rama Rajya" became a major concept in Hindu nationalism.

Madan Mohan Malviya

Madan Mohan Malviya, an educationist and a politician with the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

was also a vociferous proponent of the philosophy of ''Bhagavad Gita'' (Bhagavad Gītā). He was the president of the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

in the year 1909 and 1918.Satyameva Jayate

Satyameva Jayate (; ) is a part of a ''mantra'' from the Hindu texts, Hindu scripture ''Mundaka Upanishad''. Following the independence of India, it was adopted as the national motto of India on 26 January 1950, the day India became a Republic ...

" (Truth alone triumphs), from the Mundaka Upanishad

The Mundaka Upanishad (, ) is an ancient Sanskrit Vedic text, embedded inside Atharva Veda. It is a Mukhya (primary) Upanishad, and is listed as number 5 in the Muktika canon of 108 Upanishads of Hinduism. It is among the most widely translat ...

, which today is the national motto of the Republic of India. He founded the Benaras Hindu University

Banaras Hindu University (BHU), formerly Benares Hindu University, is a collegiate, central, and research university located in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India, and founded in 1916. The university incorporated the Central Hindu College, ...

in 1919 and became its first Vice-Chancellor.

Keshav Baliram Hedgewar

Another leader of prime importance in the ascent of Hindu nationalism was Keshav Baliram Hedgewar of

Another leader of prime importance in the ascent of Hindu nationalism was Keshav Baliram Hedgewar of Nagpur

Nagpur (; ISO 15919, ISO: ''Nāgapura'') is the second capital and third-largest city of the Indian state of Maharashtra. It is called the heart of India because of its central geographical location. It is the largest and most populated city i ...

. Hedgewar as a medical student in Calcutta had been part of the revolutionary activities of the Hindu Mahasabha, Anushilan Samiti and Jugantar.[Chitkara M G, Hindutva, Published by APH Publishing, 1997 ] He was charged with sedition in 1921 by the British Administration and served a year in prison. He was briefly a member of the Indian National Congress.[ In 1925, he left the Congress to form the ]Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS,, ) is an Indian right-wing politics, right-wing, Hindutva, Hindu nationalist volunteer paramilitary organisation. It is the progenitor and leader of a large body of organisations called the Sangh Parivar ( ...

(RSS) with the help of Hindu Mahasabha Leader B. S. Moonje, Bapuji Soni, Gatate Ji etc., which would become the focal point of Hindu movements in Independent India.Satyagraha

Satyāgraha (from ; ''satya'': "truth", ''āgraha'': "insistence" or "holding firmly to"), or "holding firmly to truth",' or "truth force", is a particular form of nonviolent resistance or civil resistance. Someone who practises satyagraha is ...

movement against the British Government, Hedgewar participated in the movement in his capacity and did not let the RSS join the freedom movement officially. The RSS portrayed itself as a social movement rather than a political party, and did not play a central role in any of the Indian independence movement

The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events in South Asia with the ultimate aim of ending British Raj, British colonial rule. It lasted until 1947, when the Indian Independence Act 1947 was passed.

The first nationalistic ...

.Lahore Resolution

The Lahore Resolution, later called the Pakistan Resolution in Pakistan, was a formal political statement adopted by the All-India Muslim League on the occasion of its three-day general session in Lahore, Punjab, from 22 to 24 March 1940, call ...

demanding a separate Pakistan, the RSS campaigned for a Hindu nation, but stayed away from the independence struggle. When the British colonial government banned military drills and the use of uniforms in non-official organizations, Golwalkar terminated the RSS military department.

Bengali Hindu Homeland Movement

The Bengali Hindu Homeland Movement refers to the movement of the Bengali Hindu

Bengali Hindus () are adherents of Hinduism who ethnically, linguistically and genealogically identify as Bengalis. They make up the majority in the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, and Assam's Barak Valley ...

people for the Partition of Bengal in 1947 to create a homeland for themselves within India, in the wake of Muslim League's proposal and campaign to include the entire province of Bengal

Bengal ( ) is a Historical geography, historical geographical, ethnolinguistic and cultural term referring to a region in the Eastern South Asia, eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal. The region of Benga ...

within Pakistan, which was to be a homeland for the Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

s of British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance in South Asia. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one form or another ...

. The movement began in late 1946, especially after the Great Calcutta Killing and Noakhali genocide, gained significant momentum in April 1947 and in the end met with success on 20 June 1947 when the legislators from the Hindu majority areas returned their verdict in favour of Partition and the Bengal Presidency

The Bengal Presidency, officially the Presidency of Fort William in Bengal until 1937, later the Bengal Province, was the largest of all three presidencies of British India during Company rule in India, Company rule and later a Provinces o ...

was divided into West Bengal

West Bengal (; Bengali language, Bengali: , , abbr. WB) is a States and union territories of India, state in the East India, eastern portion of India. It is situated along the Bay of Bengal, along with a population of over 91 million inhabi ...

and East Pakistan

East Pakistan was the eastern province of Pakistan between 1955 and 1971, restructured and renamed from the province of East Bengal and covering the territory of the modern country of Bangladesh. Its land borders were with India and Burma, wit ...

.

Post-independence

After the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated on 30 January 1948 at age 78 in the compound of The Birla House (now Gandhi Smriti), a large mansion in central New Delhi. His assassin was Nathuram Godse, from Pune, Maharashtra, a Hindu nationalist, with ...

by Nathuram Godse

Nathuram Vinayak Godse (19 May 1910 – 15 November 1949) () was an Indian Hindu nationalist and political activist who was the assassin of Mahatma Gandhi. He shot Gandhi in the chest three times at point blank range at a multi-faith praye ...

, the Sangh Parivar was plunged into distress when the RSS was accused of involvement in his murder. Along with the conspirators and the assassin, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar (28 May 1883 – 26 February 1966 ), was an Indian politician, activist and writer. Savarkar developed the Hindu nationalist political ideology of Hindutva while confined at Ratnagiri in 1922. The prefix "Veer" (mea ...

was also arrested. The court acquitted Savarkar, and the RSS was found be to completely unlinked with the conspirators.[Report of Commission of Inquiry into Conspiracy to Murder Mahatma Gandhi, By India (Republic). Commission of Inquiry into Conspiracy to Murder Mahatma Gandhi, Jeevan Lal Kapur, Published by Ministry of Home affairs, 1970, page 165] The Hindu Mahasabha

Akhil Bharatiya Hindu Mahasabha (), simply known as Hindu Mahasabha, is a Hindu nationalism, Hindu nationalist political party in India.

Founded in 1915 by Madan Mohan Malviya, the Mahasabha functioned mainly as a pressure group advocating th ...

, of which Godse was a member, lost membership and popularity. The effects of public outrage had a permanent effect on the Hindu Mahasabha.

Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, which was started in 1925, had grown by the end of British rule in India.Nathuram Godse

Nathuram Vinayak Godse (19 May 1910 – 15 November 1949) () was an Indian Hindu nationalist and political activist who was the assassin of Mahatma Gandhi. He shot Gandhi in the chest three times at point blank range at a multi-faith praye ...

, a former member of the RSS.[—]

— Following the assassination, many prominent leaders of the RSS were arrested, and the RSS as an organisation was banned on 4 February 1948 by the then Home Minister Patel. During the court proceedings in relation to the assassination Godse began claiming that he had left the organisation in 1946.Supreme Court of India

The Supreme Court of India is the supreme judiciary of India, judicial authority and the supreme court, highest court of the Republic of India. It is the final Appellate court, court of appeal for all civil and criminal cases in India. It also ...

. Following his release in August 1948, Golwalkar wrote to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to lift the ban on RSS. After Nehru replied that the matter was the responsibility of the Home Minister, Golwalkar consulted Vallabhai Patel regarding the same. Patel then demanded an absolute pre-condition that the RSS adopt a formal written constitutionConstitution of India

The Constitution of India is the supreme law of India, legal document of India, and the longest written national constitution in the world. The document lays down the framework that demarcates fundamental political code, structure, procedures ...

, accept the Tricolor as the National Flag

A national flag is a flag that represents and national symbol, symbolizes a given nation. It is Fly (flag), flown by the government of that nation, but can also be flown by its citizens. A national flag is typically designed with specific meanin ...

of India, define the power of the head of the organisation, make the organisation democratic by holding internal elections, authorisation of their parents before enrolling the pre-adolescents into the movement, and to renounce violence and secrecy.[Martha Craven Nussbaum, The Clash Within: Democracy, Religious Violence, and India's Future, Published by Harvard University Press, 2007 ] RSS supported trade union, the Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh and political party Bharatiya Jana Sangh

The Akhil Bharatiya Jana Sangh ( BJS or JS, short name: Jan Sangh) was a Hindutva political party active in India. It was established on 21 October 1951 in Delhi by three founding members: Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, Balraj Madhok and Deendayal ...

also grew into considerable prominence by the end of the decade.

Another prominent development was the formation of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), an organisation of Hindu religious leaders, supported by the RSS, to unite the various Hindu religious denominations and to usher a social reform. The first VHP meeting in Mumbai was attended among others by all the Shankaracharyas, Jain leaders, Sikh leader Master Tara Singh Malhotra, the Dalai Lama

The Dalai Lama (, ; ) is the head of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism. The term is part of the full title "Holiness Knowing Everything Vajradhara Dalai Lama" (圣 识一切 瓦齐尔达喇 达赖 喇嘛) given by Altan Khan, the first Shu ...

and contemporary Hindu leaders like Swami Chinmayananda. From its initial years, the VHP led a concerted attack on the social evils of untouchability and casteism while launching social welfare programmes in the areas of education and health care, especially for the Scheduled Castes, backward classes, and the tribals.[Smith, David James, Hinduism and Modernity P189, Blackwell Publishing ]

The organisations started and supported by the RSS volunteers came to be known collectively as the Sangh Parivar. The next few decades saw a steady growth of the influence of the Sangh Parivar in the social and political space of India.

Ayodhya dispute

The Ayodhya dispute () is a political, historical and socio-religious debate in India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

, centred on a plot of land in the city of Ayodhya

Ayodhya () is a city situated on the banks of the Sarayu river in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. It is the administrative headquarters of the Ayodhya district as well as the Ayodhya division of Uttar Pradesh, India. Ayodhya became th ...

, located in Ayodhya

Ayodhya () is a city situated on the banks of the Sarayu river in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. It is the administrative headquarters of the Ayodhya district as well as the Ayodhya division of Uttar Pradesh, India. Ayodhya became th ...

district, Uttar Pradesh

Uttar Pradesh ( ; UP) is a States and union territories of India, state in North India, northern India. With over 241 million inhabitants, it is the List of states and union territories of India by population, most populated state in In ...

. The main issues revolve around access to a site traditionally regarded as the birthplace of the Hindu

Hindus (; ; also known as Sanātanīs) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism, also known by its endonym Sanātana Dharma. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pp. 35–37 Historically, the term has also be ...

deity Rama

Rama (; , , ) is a major deity in Hinduism. He is worshipped as the seventh and one of the most popular avatars of Vishnu. In Rama-centric Hindu traditions, he is considered the Supreme Being. Also considered as the ideal man (''maryāda' ...

, the history and location of the Babri Mosque at the site, and whether a previous Hindu temple was demolished or modified to create the mosque.

Sexual and gender minorities

Contrary to the lean of conservative parties in the western world, the BJP has been supported by sexual minorities such as women and LGBTQ. The party was influential in sponsoring a serious of agitations in support of women and protests against the rape and murder of a woman doctor, a movement that has been called "reclaim the night".

Hindutva and Hindu Rashtra

Sarkar

Professor Benoy Kumar Sarkar coined the term Hindu Rastra. In his book named ''Building of Hindu Rastra'' (হিন্দু রাস্ট্রের গড়ন) presented the idea of structural of Hindu state and directives for the socio-economic and political system of the Hindu state. He is deemed the pioneer ideologue of Hindu Rashtra. Many people identify his philosophy as 'Sarkarism'.

His writings on this subject amounted to nearly 30,000 pages. A complete list of his publications is contained in Bandyopadhyay's book ''The Political Ideas of Benoy Kumar Sarkar''.

* 1914/1921 ''The Positive Background of Hindu Sociology''

* 1916 ''The beginning of Hindu culture as world-power (A.D. 300-600)''

* 1916 ''Chinese Religion Through Hindu Eyes''

* 1918 ''Hindu achievements in exact science a study in the history of scientific development''

In 1919, he authored a study in the ''American Political Science Review'' presenting a "Hindu theory of international relations" which drew on thinkers such as Kautilya, Manu and Shookra, and the text of the Mahabharata.

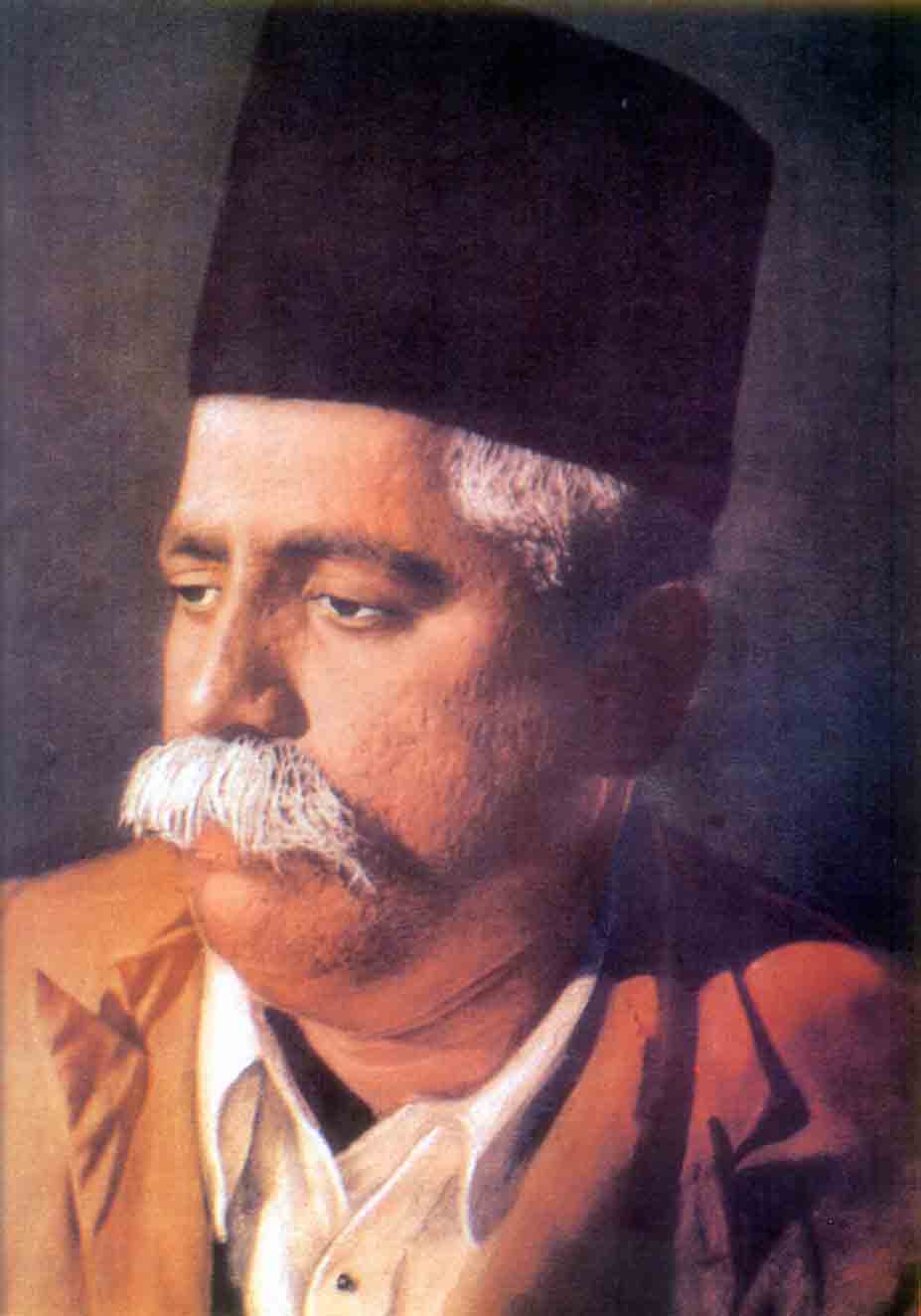

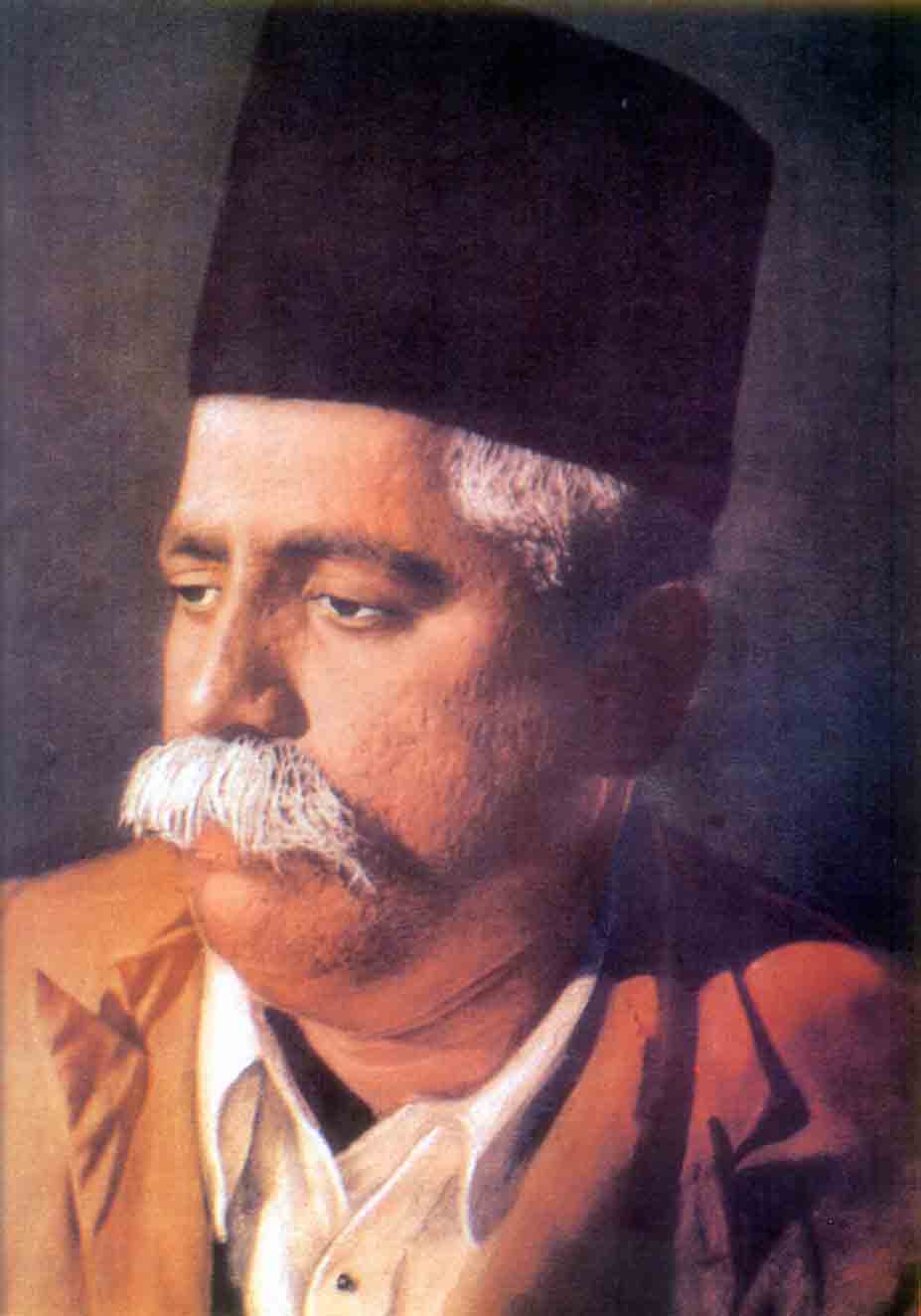

Savarkar

Savarkar was one of the first in the twentieth century to attempt a definitive description of the term "Hindu" in terms of what he called ''Hindutva'' meaning Hinduness.

Savarkar was one of the first in the twentieth century to attempt a definitive description of the term "Hindu" in terms of what he called ''Hindutva'' meaning Hinduness.[Savarkar, Vinayak Damodar: Hindutva, Bharati Sahitya Sadan, Delhi 1989 (1923).] The coinage of the term "Hindutva" was an attempt by Savarkar who was non religious and a rationalist, to de-link it from any religious connotations that had become attached to it. He defined the word Hindu as: "He who considers India as both his Fatherland and Holyland". He thus defined Hindutva ("Hindu-ness") or Hindu as different from Hinduism.[ This definition kept the ]Abrahamic religions

The term Abrahamic religions is used to group together monotheistic religions revering the Biblical figure Abraham, namely Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The religions share doctrinal, historical, and geographic overlap that contrasts them wit ...

(Judaism, Christianity and Islam) outside its ambit and considered only native religious denominations as Hindu.

This distinction was emphasised on the basis of territorial loyalty rather than on religious practices. In this book which was written in the backdrop of the Khilafat Movement

The Khilafat movement (1919–22) was a political campaign launched by Indian Muslims in British India over British policy against Turkey and the planned dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire after World War I by Allied forces.

Leaders particip ...

and the subsequent Malabar rebellion, Savarkar wrote "Their uslims' and Christians'holy land is far off in Arabia or Palestine. Their mythology and Godmen, ideas and heroes are not the children of this soil. Consequently, their names and their outlook smack of foreign origin. Their love is divided".[The Hindu Phenomenon, Girilal Jain, .] The concept of Hindu Polity called for the protection of Hindu people and their culture and emphasised that political and economic systems should be based on native thought rather than on the concepts borrowed from the West.

Mukherjee

Mookerjee was the founder of the Nationalist

Mookerjee was the founder of the Nationalist Bharatiya Jana Sangh

The Akhil Bharatiya Jana Sangh ( BJS or JS, short name: Jan Sangh) was a Hindutva political party active in India. It was established on 21 October 1951 in Delhi by three founding members: Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, Balraj Madhok and Deendayal ...

party, the precursor of the Bharatiya Janata Party

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP; , ) is a political party in India and one of the two major List of political parties in India, Indian political parties alongside the Indian National Congress. BJP emerged out from Syama Prasad Mukherjee's ...

. Mookerjee was firmly against Nehru's invitation to the Pakistani PM, and their joint pact to establish minority commissions and guarantee minority rights in both countries. He wanted to hold Pakistan directly responsible for the terrible influx of millions of Hindu refugees from East Pakistan

East Pakistan was the eastern province of Pakistan between 1955 and 1971, restructured and renamed from the province of East Bengal and covering the territory of the modern country of Bangladesh. Its land borders were with India and Burma, wit ...

, who had left the state fearing religious suppression and violence aided by the state.

After consultation with Golwalkar of RSS, Mookerjee founded Bharatiya Jana Sangh on 21 October 1951 at Delhi and he became the first President of it. The BJS was ideologically close to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS,, ) is an Indian right-wing politics, right-wing, Hindutva, Hindu nationalist volunteer paramilitary organisation. It is the progenitor and leader of a large body of organisations called the Sangh Parivar ( ...

and widely considered the political arm of Hindu Nationalism

Hindu nationalism has been collectively referred to as the expression of political thought, based on the native social and cultural traditions of the Indian subcontinent. "Hindu nationalism" is a simplistic translation of . It is better descri ...

. It was opposed to appeasement of India's Muslims. The BJS also favored a uniform civil code governing personal law matters for both Hindus and Muslims, wanted to ban cow slaughter and end the special status given to the Muslim-majority state of Jammu and Kashmir. The BJS founded the Hindutva

Hindutva (; ) is a Far-right politics, far-right political ideology encompassing the cultural justification of Hindu nationalism and the belief in establishing Hindu hegemony within India. The political ideology was formulated by Vinayak Da ...

agenda which became the wider political expression of India's Hindu majority.

Mookerjee opposed the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

's decision to grant Kashmir

Kashmir ( or ) is the Northwestern Indian subcontinent, northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term ''Kashmir'' denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir P ...

a special status with its own flag and Prime Minister. According to Congress's decision, no one, including the President of India

The president of India (ISO 15919, ISO: ) is the head of state of the Republic of India. The president is the nominal head of the executive, the first citizen of the country, and the commander-in-chief, supreme commander of the Indian Armed ...

could enter into Kashmir

Kashmir ( or ) is the Northwestern Indian subcontinent, northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term ''Kashmir'' denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir P ...

without the permission of Kashmir's Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

. In opposition to this decision, he entered Kashmir on 11 May 1953. Thereafter, he was arrested and jailed in a dilapidated house.

Golwalkar

M. S. Golwalkar, the second head of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS,, ) is an Indian right-wing politics, right-wing, Hindutva, Hindu nationalist volunteer paramilitary organisation. It is the progenitor and leader of a large body of organisations called the Sangh Parivar ( ...

(RSS), was to further this non-religious, territorial loyalty based definition of "Hindu" in his book ''Bunch of Thoughts''. Hindutva and Hindu Rashtra would form the basis of Golwalkar's ideology and that of the RSS.

While emphasising religious pluralism

Religious pluralism is an attitude or policy regarding the diversity of religion, religious belief systems co-existing in society. It can indicate one or more of the following:

* Recognizing and Religious tolerance, tolerating the religio ...

, Golwalkar believed that Semitic monotheism and exclusivism were incompatible with and against the native Hindu culture. He wrote:

He added:

He further would echo the views of Savarkar on territorial loyalty, but with a degree of inclusiveness, when he wrote "So, all that is expected of our Muslim and Christian co-citizens is the shedding of the notions of their being 'religious minorities' as also their foreign mental complexion and merging themselves in the common national stream of this soil."[

After the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi, Golwalkar and Hindu Mahasabha's senior leaders such as Shyama Prasad Mukharji founded a new political party as Jan Sangh, many of Hindu Mahasabha members joined Jan Sangh.

]

Deendayal Upadhyaya

Deendayal Upadhyaya, another RSS ideologue, presented Integral Humanism as the political philosophy of the erstwhile Bharatiya Jana Sangh in the form of four lectures delivered in Bombay

Mumbai ( ; ), also known as Bombay ( ; its official name until 1995), is the capital city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of Maharashtra. Mumbai is the financial centre, financial capital and the list of cities i ...

on 22–25 April 1965 as an attempt to offer a third way, rejecting both communism and capitalism as the means for socio-economic emancipation.

Contemporary descriptions

Later thinkers of the RSS, like H. V. Sheshadri and K. S. Rao, were to emphasise on non-theocratic nature of the word "Hindu Rashtra", which they believed was often inadequately translated, ill interpreted and wrongly stereotyped as a theocratic state. In a book, H. V. Sheshadri, the senior leader of the RSS writes "As Hindu Rashtra is not a religious concept, it is also not a political concept. It is generally misinterpreted as a theocratic state or a religious Hindu state. Nation (Rashtra) and State (Rajya) are entirely different and should never be mixed up. The state is purely a political concept. The State changes as the political authority shifts from person to person or party to party. But the people in the Nation remain the same. They would maintain that the concept of Hindu Rashtra is in complete agreement with the principles of secularism and democracy.

The concept of "'Hindutva" continues to be espoused by organisations like the RSS and political parties like the Bharatiya Janata Party

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP; , ) is a political party in India and one of the two major List of political parties in India, Indian political parties alongside the Indian National Congress. BJP emerged out from Syama Prasad Mukherjee's ...

(BJP). But the definition does not have the same rigidity with respect to the concept of "holy land" laid down by Savarkar, and stresses on inclusivism and patriotism. BJP leader Atal Bihari Vajpayee

Atal Bihari Vajpayee (25 December 1924 – 16 August 2018) was an Indian poet, writer and statesman who served as the prime minister of India, first for a term of 13 days in 1996, then for a period of 13 months from 1998 ...

, in 1998, articulated the concept of "holy land" in Hindutva as follows: "Mecca can continue to be holy for the Muslims but India should be holier than the holy for them. You can go to a mosque and offer namaz, you can keep the ''roza''. We have no problem. But if you have to choose between Mecca or Islam and India you must choose India. All the Muslims should have this feeling: we will live and die only for this country."

In a 1995 landmark judgment, the Supreme Court of India

The Supreme Court of India is the supreme judiciary of India, judicial authority and the supreme court, highest court of the Republic of India. It is the final Appellate court, court of appeal for all civil and criminal cases in India. It also ...

observed that "Ordinarily, Hindutva is understood as a way of life or a state of mind and is not to be equated with or understood as religious Hindu fundamentalism. A Hindu may embrace a non-Hindu religion without ceasing to be a Hindu and since the Hindu is disposed to think synthetically and to regard other forms of worship, strange gods and divergent doctrines as inadequate rather than wrong or objectionable, he tends to believe that the highest divine powers complement each other for the well-being of the world and mankind."

Hindu Rashtra movements in Nepal

In 2008, Nepal was declared a secular state

is an idea pertaining to secularity, whereby a state is or purports to be officially neutral in matters of religion, supporting neither religion nor irreligion. A secular state claims to treat all its citizens equally regardless of relig ...

after the Maoist led 1996–2006 Nepalese Civil War and the following 2006 Nepalese revolution led to the abolition of monarchy of Nepal. Before becoming a secular republic, Kingdom of Nepal

The Kingdom of Nepal was a Hindu monarchy in South Asia, founded in 1768 through the unification of Nepal, expansion of the Gorkha Kingdom. The kingdom was also known as the Gorkha Empire and was sometimes called History of Asal Hindustan, ...

was the world's only country to have Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Hypernymy and hyponymy, umbrella term for a range of Indian religions, Indian List of religions and spiritual traditions#Indian religions, religious and spiritual traditions (Sampradaya, ''sampradaya''s) that are unified ...

as its state religion. Thereafter, the Rastriya Prajatantra Party Nepal changed its constitution to support monarchy and the re-establishment of the Hindu state. In December 2015, a pro-Hindu and a pro-monarchy protest was held at Kathmandu

Kathmandu () is the capital and largest city of Nepal, situated in the central part of the country within the Kathmandu Valley. As per the 2021 Nepal census, it has a population of 845,767 residing in 105,649 households, with approximately 4 mi ...

. The chairperson of CPN-Maoist Prachanda, claimed that Muslims were oppressed by the state and assured the Muslim crowd of Muslim Mukti Morcha to give special rights to Muslims in order to appease the community and garner Muslim support as his party faced losses in the Terai region during the 2008 Nepalese Constituent Assembly election. However, during the 2015 "Hindu Rashtra" campaigning in Nepal by the Rashtriya Prajatantra Party Nepal, the Nepalese Muslim groups demanded Nepal to be a "Hindu Rashtra" (Hindu Nation) under which they claimed to "feel secure" compared to the secular constitution. Nepalese Muslim groups also opined that the increasing influences of Christianity in Nepal that promote conversion against all other faiths is a reason they want Nepal to have a Hindu state identity under which all religions are protected.Kamal Thapa

Kamal Thapa () is a Nepalese politician belonging to Rastriya Prajatantra Party Nepal.

Thapa, has served as a Deputy Prime Minister of Nepal, Deputy Prime Minister and Ministry of Federal Affairs and General Administration (Nepal), Federal A ...

stated that Hindu statehood is the only means of establishing national unity and stability. He stated that the secularization of the state was done without the involvement of general public and thus, a referendum was due on the issue. Furthermore, chairperson Thapa argued that the conversion of Nepal into a secular republic was an organised attempt to weaken the national identity of Nepal and the religious conversions have seriously affected the indigenous and Dalit

Dalit ( from meaning "broken/scattered") is a term used for untouchables and outcasts, who represented the lowest stratum of the castes in the Indian subcontinent. They are also called Harijans. Dalits were excluded from the fourfold var ...

communities. The Rastriya Prajatantra Party Nepal has stated support for a Hindu state with religious freedom

Freedom of religion or religious liberty, also known as freedom of religion or belief (FoRB), is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice ...

and registered an amendment proposal for such on 19 March 2017.

On 30 November 2020, a pro-Hindu and a pro-monarchy protest was held at Kathmandu. Similar protests were held on other major cities like Pokhara

Pokhara ( ) is a metropolis, metropolitan city located in central Nepal, which serves as the capital of Gandaki Province. Named the country's "capital of tourism" it is the List of cities in Nepal, second largest city after Kathmandu, with 599,5 ...

and Butwal

Butwal (), officially Butwal Sub-Metropolitan City (), previously known as Khasyauli (Nepali: खस्यौली), is a sub-metropolitan city and economic hub in Lumbini Province in West Nepal. Butwal has a city population of 195,054 as per t ...

.

On 4 December 2020, mass protests were held at Maitighar that ended in Naya Baneshwor demanding the restoration of Hindu statehood with constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions. ...

. The protestors carried the national flags and posters of the founding father of modern Nepal, King Prithvi Narayan Shah

Prithvi Narayan Shah (; 7 January 1723 – 11 January 1775), was the last king of the Gorkha Kingdom and first king of the Kingdom of Nepal (also called the ''Kingdom of Gorkha''). Prithvi Narayan Shah started the unification of Nepal. He is a ...

, and chanted slogans supporting Hindu statehood. Protestors claimed the Hindu statehood is a means of national unity and well being of the people. This protest is considered one of the biggest pro-monarchy demonstrations.

On 11 January 2021, mass protests were held at Kathmandu

Kathmandu () is the capital and largest city of Nepal, situated in the central part of the country within the Kathmandu Valley. As per the 2021 Nepal census, it has a population of 845,767 residing in 105,649 households, with approximately 4 mi ...

demanding the restoration of Hindu statehood with monarchy. Police baton charged at the protestors around the Prime Minister's Office resulting in protestors responding with stones and sticks. In August 2021, similar protests led by former Nepal Army General Rookmangud Katawal were also observed.

See also

* Akhand Bharat

* Civilization state

* Ethnic relations in India

* Greater India

* Hindu revolution

* Hinduism in India

Hinduism is the largest and most practised religion in India. About 80% of the country's population is Hindu. India contains 94% of the global Hindu population. The vast majority of Indian Hindus belong to Vaishnavite, Shaivite, and Sh ...

* History of India

Anatomically modern humans first arrived on the Indian subcontinent between 73,000 and 55,000 years ago. The earliest known human remains in South Asia date to 30,000 years ago. Sedentism, Sedentariness began in South Asia around 7000 BCE; ...

* Indianisation

* Indocentrism

* Indomania

* Indosphere

* List of Hindu nationalist political parties

* List of Hindu organisations

* Religion in India

Religion in India is characterised by a diversity of religious beliefs and practices. Throughout India's history, religion has been an important part of the country's culture and the Indian subcontinent is the birthplace of four of the Major ...

* Religious violence in India

* Revocation of the special status of Jammu and Kashmir

* Saffron terror

References

Citations

Books

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Further reading

*

*

*

*

*

*

* Bacchetta, Paola."Gendered Fractures in Hindu Nationalism: On the Subject-Members of the Rashtra Sevika Samiti."In The Oxford India Hinduism: A Reader, edited by Vasudha Dalmia and Heinrich von Stietencron, 373–395. London and Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2006.

* Bacchetta, Paola. Gender in the Hindu Nation: RSS Women as Ideologues. New Delhi: Women Unlimited, 2004.

* Walter K. Andersen. 'Bharatiya Janata Party: Searching for the Hindu Nationalist Face', In The New Politics of the Right: Neo–Populist Parties and Movements in Established Democracies, ed. Hans–Georg Betz and Stefan Immerfall (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1998), pp. 219–232. ( or )

* Partha Banerjee, In the Belly of the Beast: The Hindu Supremacist RSS and BJP of India (Delhi: Ajanta, 1998).

*

* Ainslie T. Embree, 'The Function of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh: To Define the Hindu Nation', in Accounting for Fundamentalisms, The Fundamentalism Project 4, ed. Martin E. Marty and R. Scott Appleby (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1994), pp. 617–652. ()

*

*

* Arun Shourie, Goel, Sita Ram, et al. Time for Stock-Taking – Whither Sangh Parivar? (1997)

* Girilal Jain

The Hindu phenomenon

South Asia Books (1995). .

* H V Seshadri, K S Sudarshan, K. Surya Narayan Rao, Balraj Madhok

Suruchi Prakashan (1990), ASIN B001NX9MCA.

External links

*

*

*

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hindu Nationalism

*

Islamophobia in India

Hindu fundamentalism

Political fundamentalism in India

Anti-Christian sentiment in India

Anti-Islam sentiment in India

Neo-Vedanta

Hindu movements

Political ideologies

Religious nationalism

History of the Republic of India

Indian nationalism

Ethnic nationalism

Maharajadhiraja

Maharajadhiraja  The Nepali

The Nepali

Another 19th-century Hindu reformer was

Another 19th-century Hindu reformer was

" Lal-Bal-Pal" is the phrase that is used to refer to the three nationalist leaders Lala Lajpat Rai,

" Lal-Bal-Pal" is the phrase that is used to refer to the three nationalist leaders Lala Lajpat Rai,  Though

Though  Another leader of prime importance in the ascent of Hindu nationalism was Keshav Baliram Hedgewar of

Another leader of prime importance in the ascent of Hindu nationalism was Keshav Baliram Hedgewar of  Savarkar was one of the first in the twentieth century to attempt a definitive description of the term "Hindu" in terms of what he called ''Hindutva'' meaning Hinduness.Savarkar, Vinayak Damodar: Hindutva, Bharati Sahitya Sadan, Delhi 1989 (1923). The coinage of the term "Hindutva" was an attempt by Savarkar who was non religious and a rationalist, to de-link it from any religious connotations that had become attached to it. He defined the word Hindu as: "He who considers India as both his Fatherland and Holyland". He thus defined Hindutva ("Hindu-ness") or Hindu as different from Hinduism. This definition kept the