HMS Exeter (68) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

HMS ''Exeter'' was the second and last

In 1932 ''Exeter'' had her side plating extended to enclose her open main deck as far back as the fore funnel.Raven & Roberts, p. 266. During that same refit, her pair of fixed catapults were finally installed for her

In 1932 ''Exeter'' had her side plating extended to enclose her open main deck as far back as the fore funnel.Raven & Roberts, p. 266. During that same refit, her pair of fixed catapults were finally installed for her

On 13 February Allied reconnaissance aircraft spotted Japanese invasion convoys north of

On 13 February Allied reconnaissance aircraft spotted Japanese invasion convoys north of

The following day, after making temporary repairs and refuelling, the ''Exeter'', escorted by ''Encounter'' and the American destroyer , was ordered to steam to Colombo, via the

The following day, after making temporary repairs and refuelling, the ''Exeter'', escorted by ''Encounter'' and the American destroyer , was ordered to steam to Colombo, via the

The wreck was discovered and positively identified by a group of exploration divers specifically searching for ''Exeter'' aboard MV ''Empress'' on 21 February 2007. The wreck was found lying on its starboard side in Indonesian waters at a depth of about , north-west of

The wreck was discovered and positively identified by a group of exploration divers specifically searching for ''Exeter'' aboard MV ''Empress'' on 21 February 2007. The wreck was found lying on its starboard side in Indonesian waters at a depth of about , north-west of

heavy cruiser

A heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range and high speed, armed generally with naval guns of roughly 203 mm (8 inches) in calibre, whose design parameters were dictated by the Washington Naval Treat ...

built for the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

during the late 1920s. Aside from a temporary deployment with the Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between ...

during the Abyssinia Crisis

The Abyssinia Crisis, also known in Italy as the Walwal incident, was an international crisis in 1935 that originated in a dispute over the town of Walwal, which then turned into a conflict between Fascist Italy and the Ethiopian Empire (then co ...

of 1935–1936, she spent the bulk of the 1930s assigned to the Atlantic Fleet or the North America and West Indies Station

The North America and West Indies Station was a formation or command of the United Kingdom's Royal Navy stationed in North American waters from 1745 to 1956, with main bases at the Imperial fortresses of Bermuda and Halifax, Nova Scotia. The ...

. When World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

began in September 1939, the cruiser was assigned to patrol South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a considerably smaller portion in the Northern Hemisphere. It can also be described as the southern Subregion#Americas, subregion o ...

n waters against German commerce raider

Commerce raiding is a form of naval warfare used to destroy or disrupt logistics of the enemy on the open sea by attacking its merchant shipping, rather than engaging its combatants or enforcing a blockade against them. Privateering is a fo ...

s. ''Exeter'' was one of three British cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several operational roles from search-and-destroy to ocean escort to sea ...

s that fought the German heavy cruiser , later that year in the Battle of the River Plate. She was severely damaged during the battle, and she was under repair for over a year.

After repairs were completed the ship spent most of 1941 on convoy

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

escort duties before she was transferred to the Far East

The Far East is the geographical region that encompasses the easternmost portion of the Asian continent, including North Asia, North, East Asia, East and Southeast Asia. South Asia is sometimes also included in the definition of the term. In mod ...

after the start of the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War or the Pacific Theatre, was the Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II fought between the Empire of Japan and the Allies of World War II, Allies in East Asia, East and Southeast As ...

in December. ''Exeter'' was generally assigned to escorting convoys to and from Singapore

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree ...

during the Malayan Campaign

The Malayan campaign, referred to by Japanese sources as the , was a military campaign fought by Allies of World War II, Allied and Axis powers, Axis forces in British Malaya, Malaya, from 8 December 1941 – 15 February 1942 during the World War ...

, and she continued on those duties in early February 1942 as the Japanese prepared to invade the Dutch East Indies. Later that month, she was assigned to the Striking Force of the joint American-British-Dutch-Australian Command

The American-British-Dutch-Australian (ABDA) Command, or ABDACOM, was the short-lived supreme command for all Allied forces in South East Asia in early 1942, during the Pacific War in World War II. The command consisted of the forces of Austra ...

(ABDACOM), and she took on a more active role in the defence of the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies (; ), was a Dutch Empire, Dutch colony with territory mostly comprising the modern state of Indonesia, which Proclamation of Indonesian Independence, declared independence on 17 Au ...

. The culmination of this was her engagement in the Battle of the Java Sea

The Battle of the Java Sea (, ) was a decisive naval battle of the Pacific campaign of World War II.

Allied navies suffered a disastrous defeat at the hand of the Imperial Japanese Navy on 27 February 1942 and in secondary actions over succ ...

later in the month as the Allies attempted to intercept several Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, Potsdam Declaration, when it was dissolved followin ...

invasion convoys. ''Exeter'' was crippled early in the battle, and she did not play much of a role as she withdrew. Two days later, she attempted to escape approaching Japanese forces, but she was intercepted and sunk by Japanese ships at the beginning of March in the Second Battle of the Java Sea.

Most of her crewmen survived the sinking and were rescued by the Japanese. About a quarter of them died during Japanese captivity. Her wreck was discovered in early 2007, and it was declared a war grave, but by 2016 her remains, along with other WWII wrecks, had been destroyed by illegal salvagers.

Design and description

''Exeter'' was ordered two years after hersister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same Ship class, class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They o ...

and her design incorporated improvements in light of experience with the latter. Her beam was increased by to compensate for increases in topweight, and her boiler uptakes were trunked backwards from the boiler rooms, allowing for straight funnel

A funnel is a tube or pipe that is wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, used for guiding liquid or powder into a small opening.

Funnels are usually made of stainless steel, aluminium, glass, or plastic. The material used in its constructi ...

s further removed from the bridge

A bridge is a structure built to Span (engineering), span a physical obstacle (such as a body of water, valley, road, or railway) without blocking the path underneath. It is constructed for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle, whi ...

rather than the raked funnels on ''York'' to ensure adequate dispersal of the flue gases. As the gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechanis ...

s had proved not strong enough to accommodate the aircraft catapult

An aircraft catapult is a device used to help fixed-wing aircraft gain enough airspeed and lift for takeoff from a limited distance, typically from the deck of a ship. They are usually used on aircraft carrier flight decks as a form of assist ...

originally intended, ''Exeter'' was given a pair of fixed catapults angled out from amidships in a "V" shape, with the associated crane placed to starboard. Consequently, the bridge was lowered (that of ''York'' being tall to give a view over the intended aircraft), and was of a streamlined

Streamlines, streaklines and pathlines are field lines in a fluid flow.

They differ only when the flow changes with time, that is, when the flow is not steady flow, steady.

Considering a velocity vector field in three-dimensional space in the f ...

, enclosed design that was incorporated into later cruisers.

''Exeter'' was slightly lighter than expected and displaced at standard load and at deep load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into weig ...

. The ship had an overall length

The overall length (OAL) of an ammunition cartridge is a measurement from the base of the brass shell casing to the tip of the bullet, seated into the brass casing. Cartridge overall length, or "COL", is important to safe functioning of reloads i ...

of , a beam of and a draught of at deep load. She was powered by four Parsons geared steam turbine

A steam turbine or steam turbine engine is a machine or heat engine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work utilising a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Sir Charles Par ...

sets, each driving one shaft, using steam provided by eight Admiralty 3-drum boilers. The turbines developed a total of and gave a maximum speed of . The ship could carry of fuel oil

Fuel oil is any of various fractions obtained from the distillation of petroleum (crude oil). Such oils include distillates (the lighter fractions) and residues (the heavier fractions). Fuel oils include heavy fuel oil (bunker fuel), marine f ...

which gave her a range of at . The ship's complement was 628 officers and ratings.

The main armament of the ''York''-class ships consisted of six BL Mk VIII guns in three twin-gun turrets, designated "A", "B", and "Y" from fore to aft. "A" and "B" were superfiring

Superfiring armament is a naval design technique in which two or more turrets are located one behind the other, with the rear turret located above ("super") the one in front so that it can fire over the first. This configuration meant that both ...

forward of the superstructure and "Y" was aft of it. Defence against aircraft was provided by four QF Mk V anti-aircraft (AA) guns in single mounts amidships and a pair of two-pounder () light AA guns ("pom-poms") in single mounts. The ships also fitted with two triple torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

above-water mounts for torpedoes.Raven & Roberts, p. 414

The cruisers lacked a full-length waterline

The waterline is the line where the hull of a ship meets the surface of the water.

A waterline can also refer to any line on a ship's hull that is parallel to the water's surface when the ship is afloat in a level trimmed position. Hence, wate ...

armour belt. The sides of ''Exeter''s boiler and engine rooms and the sides of the magazine

A magazine is a periodical literature, periodical publication, print or digital, produced on a regular schedule, that contains any of a variety of subject-oriented textual and visual content (media), content forms. Magazines are generally fin ...

s were protected by of armour. The transverse bulkheads at the end of her propulsion machinery rooms were thick. The top of the magazines were protected by of armour and their ends were thick. The lower deck over the machinery spaces and steering gear had a thickness of .

Modifications

In 1932 ''Exeter'' had her side plating extended to enclose her open main deck as far back as the fore funnel.Raven & Roberts, p. 266. During that same refit, her pair of fixed catapults were finally installed for her

In 1932 ''Exeter'' had her side plating extended to enclose her open main deck as far back as the fore funnel.Raven & Roberts, p. 266. During that same refit, her pair of fixed catapults were finally installed for her Fairey IIIF

The Fairey Aviation Company Fairey III was a family of British reconnaissance biplanes that enjoyed a very long production and service history in both landplane and seaplane variants. First flying on 14 September 1917, examples were still in u ...

floatplane

A floatplane is a type of seaplane with one or more slender floats mounted under the fuselage to provide buoyancy. By contrast, a flying boat uses its fuselage for buoyancy. Either type of seaplane may also have landing gear suitable for land, ...

s. In 1934–1935, two quadruple mounts for Vickers antiaircraft

Anti-aircraft warfare (AAW) is the counter to aerial warfare and includes "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It encompasses surface-based, subsurface ( submarine-launched), and air-ba ...

machineguns replaced the pair of two-pounder "pom-poms" originally installed.

While under repair in 1940–1941 after her battle with the ''Admiral Graf Spee'', the Royal Navy decided to upgrade her armament and fire-control systems. The bridge was rebuilt and enlarged to accommodate a second High-Angle Control System aft of the Director-Control Tower (DCT) on top of the bridge, her single four-inch AA guns were replaced with twin-gun mounts for Mark XVI guns of the same calibre and a pair of octuple mounts for two-pounder "pom-poms" were added abreast her aft superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

. Enclosures ("tubs") for single Oerlikon guns were added to the roof of both 'B' and 'Y' turrets,Whitley, p. 95 but these weapons were never installed, because of shortages in production, and lighter tripod-mounted machine guns were substituted. The pole mast

Mast, MAST or MASt may refer to:

Engineering

* Mast (sailing), a vertical spar on a sailing ship

* Flagmast, a pole for flying a flag

* Guyed mast, a structure supported by guy-wires

* Mooring mast, a structure for docking an airship

* Radio mas ...

s were replaced by stronger tripod masts because the Type 279 early-warning radar

An early-warning radar is any radar system used primarily for the long-range detection of its targets, i.e., allowing defences to be alerted as ''early'' as possible before the intruder reaches its target, giving the air defences the maximum tim ...

had separate transmitting and receiving aerials, one at each masthead. In addition, a Type 284 fire-control radar

A fire-control radar (FCR) is a radar that is designed specifically to provide information (mainly target azimuth, elevation, range and range rate) to a fire-control system in order to direct weapons such that they hit a target. They are someti ...

was fitted to the DCT.

Construction and career

1928–1939

''Exeter'', the fourth ship of her name to serve in the Royal Navy, waslaid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one ...

on 1 August 1928, launched on 18 July 1929 and completed on 27 July 1931. The ship was then assigned to the 2nd Cruiser Squadron

The 2nd Cruiser Squadron was a formation of cruisers of the British Royal Navy from 1904 to 1919 and from 1921 to 1941 and again from 1946 to 1952.

History

First formation

The 2nd Cruiser Squadron was first formed in December, 1904 then placed ...

of the Atlantic Fleet, where she served between 1931 and 1933. In 1934 she was assigned, along with sister ship , to the 8th Cruiser Squadron based at the Royal Naval Dockyard in the Imperial fortress

Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, Lord Salisbury described Malta, Gibraltar, Bermuda, and Halifax as Imperial fortresses at the 1887 Colonial Conference, though by that point they had been so designated for decades. Later histor ...

colony

A colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule, which rules the territory and its indigenous peoples separated from the foreign rulers, the colonizer, and their ''metropole'' (or "mother country"). This separated rule was often orga ...

of Bermuda

Bermuda is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. The closest land outside the territory is in the American state of North Carolina, about to the west-northwest.

Bermuda is an ...

, on the America and West Indies Station

The North America and West Indies Station was a formation or command of the United Kingdom's Royal Navy stationed in North American waters from 1745 to 1956, with main bases at the Imperial fortresses of Bermuda and Halifax, Nova Scotia. The ...

. She remained there, aside from a temporary deployment to the Mediterranean during the Abyssinian crisis

The Abyssinia Crisis, also known in Italy as the Walwal incident, was an international crisis in 1935 that originated in a dispute over the town of Walwal, which then turned into a conflict between Fascist Italy and the Ethiopian Empire (then com ...

of 1935–1936, until 1939.

After re-commissioning in England on 29 December 1936, ''Exeter'' departed two days later, returning to Bermuda via St. Vincent, in the Cape Verde Islands

Cape Verde or Cabo Verde, officially the Republic of Cabo Verde, is an island country and archipelagic state of West Africa in the central Atlantic Ocean, consisting of ten volcanic islands with a combined land area of about . These islands ...

, Montevideo

Montevideo (, ; ) is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Uruguay, largest city of Uruguay. According to the 2023 census, the city proper has a population of 1,302,954 (about 37.2% of the country's total population) in an area of . M ...

and Punta del Este

Punta del Este () is a seaside city and peninsula on the Atlantic Coast in the Maldonado Department of southeastern Uruguay. Starting as a small town, Punta del Este grew to become a resort for the Latin and North American jet set and tourists. T ...

in Uruguay

Uruguay, officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay, is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast, while bordering the Río de la Plata to the south and the A ...

(meeting and exercising with her sister and the light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

), Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro, or simply Rio, is the capital of the Rio de Janeiro (state), state of Rio de Janeiro. It is the List of cities in Brazil by population, second-most-populous city in Brazil (after São Paulo) and the Largest cities in the America ...

and Ceará

Ceará (, ) is one of the 26 states of Brazil, located in the Northeast Region, Brazil, northeastern part of the country, on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast. It is the List of Brazilian states by population, eighth-largest Brazilian State by ...

in Brazil

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South America. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by area, fifth-largest country by area and the List of countries and dependencies by population ...

, Barbados

Barbados, officially the Republic of Barbados, is an island country in the Atlantic Ocean. It is part of the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies and the easternmost island of the Caribbean region. It lies on the boundary of the South American ...

(where the three cruisers joined the remainder of the squadron), and Tortola

Tortola () is the largest and most populated island of the British Virgin Islands, a group of islands that form part of the archipelago of the Virgin Islands. It has a surface area of with a total population of 23,908, with 9,400 residents in ...

in the British Virgin Islands

The British Virgin Islands (BVI), officially the Virgin Islands, are a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Caribbean, to the east of Puerto Rico and the United States Virgin Islands, US Virgin Islands and north-west ...

. It was initially intended for the entire squadron to be at Bermuda to take part in the ceremony there for the 12 May 1937 Coronation of George VI and Elizabeth

The coronation of the British monarch, coronation of George VI and his wife, Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, Elizabeth, as King of the United Kingdom, king and List of British royal consorts, queen of the United Kingdom and Commonwealth realm, ...

, but it was then decided to disperse the ships among the various colonies of the station, and ''Exeter'' left Bermuda on 6 May for Nassau, in the Bahamas

The Bahamas, officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an archipelagic and island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the Atlantic Ocean. It contains 97 per cent of the archipelago's land area and 88 per cent of its population. ...

, departed for Bermuda after taking part in the Bahamian parade. The ship had her bottom repainted at the dockyard in Bermuda at the end of May and her Royal Marine

The Royal Marines provide the United Kingdom's amphibious warfare, amphibious special operations capable commando force, one of the :Fighting Arms of the Royal Navy, five fighting arms of the Royal Navy, a Company (military unit), company str ...

detachment conducted combined exercises with the Bermuda Garrison

The Bermuda Garrison was the military establishment maintained on the British Overseas Territory and Imperial fortress of Bermuda by the regular British Army and its local-service militia and voluntary reserves from 1701 to 1957. The garrison ev ...

to practice raiding a hostile shore in June. The cruiser was scheduled to depart Bermuda on 21 June for a nine-month cruise, but the Governor of Trinidad signalled on 20 June for a cruiser to be sent to that colony due to riots that had broken out among strikers in the oil fields of Apex

The apex is the highest point of something. The word may also refer to:

Arts and media Fictional entities

* Apex (comics)

A-Bomb

Abomination

Absorbing Man

Abraxas

Abyss

Abyss is the name of two characters appearing in Ameri ...

and Fyzabad

Fyzabad is a town in southwestern Trinidad, south of San Fernando, west of Siparia and northeast of Point Fortin. It is named after the town of Faizabad in India. Colloquially it is known as "Fyzo" by many people.

History

Fyzabad was founde ...

, which had included the killings of two police officers. Workers in other industries had also staged sympathy strikes. ''Ajax'', which was in Nassau at the time, was ordered to Trinidad and ''Exeter'' followed the next day. On 2 July the marines of ''Exeter'' joined with those of ''Ajax'' and two-hundred police constable

A constable is a person holding a particular office, most commonly in law enforcement. The office of constable can vary significantly in different jurisdictions. ''Constable'' is commonly the rank of an officer within a police service. Other peo ...

s to assault the village of Fyzabad. The ship's marines were withdrawn on 5 July after the situation in Trinidad had stabilised, and the heavy cruiser departed immediately for Balboa, Panama

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in Latin America at the southern end of Central America, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and ...

to continue its summer (Southern Hemisphere ''winter'') cruise, which took her through the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal () is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean. It cuts across the narrowest point of the Isthmus of Panama, and is a Channel (geography), conduit for maritime trade between th ...

, up the Pacific coast of North America to HMCS Naden (the old Royal Naval Dockyard, Esquimalt), via San Diego

San Diego ( , ) is a city on the Pacific coast of Southern California, adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a population of over 1.4 million, it is the List of United States cities by population, eighth-most populous city in t ...

, California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

. ''Exeter''s return trip took her to both coasts of South America before arriving at Bermuda on 28 March 1938 together with the light cruiser . The German sail training ship ''Horst Wessel'' visited Bermuda from 21 to 25 May and the crew of ''Exeter'' hosted the German cadets during their stay.

Second World War

Battle of the River Plate

At the outbreak ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, she remained part of the South American Division with the ''Ajax''. The division was transferred to the South Atlantic Station

The Commander-in-Chief South Atlantic was an operational commander of the Royal Navy from 1939. The South American area was added to his responsibilities in 1960, and the post disestablished in 1967.

Immediately before the outbreak of the Sec ...

, with the addition of the heavy cruiser , under Commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* Commodore (rank), a naval rank

** Commodore (Royal Navy), in the United Kingdom

** Commodore (India), in India

** Commodore (United States)

** Commodore (Canada)

** Commodore (Finland)

** Commodore (Germany) or ' ...

Henry Harwood

Admiral Sir Henry Harwood Harwood, (19 January 1888 – 9 June 1950) was a Royal Navy officer who won fame in the Battle of the River Plate during the Second World War.

Early life

Following education at Stubbington House School, Harwood ent ...

. The ship, commanded by Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

Frederick Bell, was assigned to Force G to hunt for German commerce raiders off the eastern coast of South America on 6 October 1939. Two months later, Harwood ordered ''Exeter'' and the light cruiser to rendezvous with his own ''Ajax'' off the mouth of the Río de la Plata

The Río de la Plata (; ), also called the River Plate or La Plata River in English, is the estuary formed by the confluence of the Uruguay River and the Paraná River at Punta Gorda, Colonia, Punta Gorda. It empties into the Atlantic Ocean and ...

, while the heavy cruiser ''Cumberland'' was refitting in the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; ), commonly referred to as The Falklands, is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and from Cape Dub ...

. The two other ships arrived on 12 December, and then the ''Admiral Graf Spee'' spotted the ''Exeter'' during the following morning.

Captain Hans Langsdorff decided to engage the British and closed at full speed. The British doctrine on how to engage ships like the ''Admiral Graf Spee'' had been developed by Harwood in 1936 and specified that the British force act as two divisions. Following this procedure, ''Exeter'' operated as a division on her own while ''Achilles'' and ''Ajax'' formed the other, splitting the fire of the German ship. They were only partially successful as the German ship concentrated her main armament of six guns on ''Exeter'', and her secondary armament of eight guns on the light cruisers. Langsdorff opened fire on ''Exeter'' at 06:18 with high-explosive

An explosive (or explosive material) is a reactive substance that contains a great amount of potential energy that can produce an explosion if released suddenly, usually accompanied by the production of light, heat, sound, and pressure. An exp ...

shells and she returned fire two minutes later at a range of . The German ship straddled the British cruiser with her third salvo

A salvo is the simultaneous discharge of artillery or firearms including the firing of guns either to hit a target or to perform a salute. As a tactic in warfare, the intent is to cripple an enemy in many blows at once and prevent them from f ...

; shrapnel from the near misses killed the crew of the starboard torpedo tubes, started fires amidships and damaged both Supermarine Walrus

The Supermarine Walrus is a British single-engine Amphibious aircraft, amphibious biplane designed by Supermarine's R. J. Mitchell. Primarily used as a maritime patrol aircraft, it was the first British Squadron (aviation), squadron-service ai ...

seaplanes. After eight salvos from ''Exeter'', ''Admiral Graf Spee'' scored a direct hit on 'B' turret that knocked it out of action and shrapnel from the hit killed all of the bridge personnel except three. Bell, wounded in the face, transferred to the aft conning position to continue the battle. His ship was hit twice more shortly afterwards, but her powerplant was not damaged and she remained seaworthy, although her aircraft had to be jettisoned.Stephen, pp. 18–19

At 06:30, Langsdorff switched his fire to the light cruisers, but only inflicted shrapnel damage on them before some of ''Exeter''s torpedoes forced him to turn away at 06:37 to evade them. Her second torpedo attack at 06:43 was also unsuccessful. In the meanwhile, Langsdorff had switched his main guns back to the heavy cruiser and scored several more hits. They knocked out 'A' turret, started a fire amidships that damaged the ship's fire-control and navigation circuits, and caused a seven-degree list

A list is a Set (mathematics), set of discrete items of information collected and set forth in some format for utility, entertainment, or other purposes. A list may be memorialized in any number of ways, including existing only in the mind of t ...

with flooding. After "Y" turret had temporarily been disabled, Bell said, "I'm going to ram the --------. It will be the end of us but it will sink him too". The turret was repaired and she remained in action until flooding disabled the machinery for "Y" turret at 07:30. At 11:07, Bell informed Harwood that ''Exeter'' had a single eight-inch and a four-inch gun available in local control, and that she could make . Harwood ordered Bell to head to the Falklands for repair.

The ship was hit by a total of seven 283 mm shells that killed 61 of her crew and wounded another 23. In return, the cruiser had hit ''Admiral Graf Spee'' three times; one shell penetrated her main armour belt and narrowly missed detonating in one of her engine rooms, but the most important of these disabled her oil-purification equipment. Without it, the ship was unlikely to be able to reach Germany. Several days later, unable to be repaired and apparently confronted by powerful Royal Navy reinforcements (including HMS ''Cumberland''), the ''Admiral Graf Spee'' was scuttled by her captain in the harbour of Montevideo.

Although very heavily damaged, ''Exeter'' was still able to make good speed—18 knots—though four feet down by the bows, with a list of about eight degrees to starboard, and decks covered in fuel oil and water, making movement within the ship very difficult. She made for Port Stanley

Stanley (also known as Port Stanley) is the capital city of the Falkland Islands. It is located on the island of East Falkland, on a north-facing slope in one of the wettest parts of the islands. At the 2016 census, the city had a population o ...

for emergency repairs which took until January 1940. There were rumours that she would remain in Stanley, becoming a rusting hulk, until the end of the war, but First Lord of the Admiralty

First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the title of the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible f ...

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

wrote to the First Sea Lord

First Sea Lord, officially known as First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff (1SL/CNS), is the title of a statutory position in the British Armed Forces, held by an Admiral (Royal Navy), admiral or a General (United Kingdom), general of the ...

and others "We ought not readily to accept the non-repair during the war of ''Exeter''. She should be strengthened and strutted internally as far as possible . . . and come home". She was repaired and modernised at HM Dockyard, Devonport between 14 February 1940 and 10 March 1941;

Captain W.N.T. Beckett was appointed to relieve Bell on 12 December 1940. Then, on 10 March 1941, the day that ''Exeter'' was due to be recommissioned, Beckett died at Saltash Hospital from complications following exploratory surgery to repair poison gas injuries that he had received earlier in his career. His replacement was Captain Oliver Gordon.

To the Far East

Upon returning to the fleet, ''Exeter'' primarily spent time on 'working up' exercises, however she also conducted several patrols in northern waters, one on which she stopped in Iceland to refuel. On 22 May she departed from Britain (for the last time as it would turn out), escorting Convoy WS-8B to Aden (Yemen) via Freetown and Durban, South Africa (the beginning of which occurred at the very same time as the hunt for the . was taking place). ''Exeter'' henceforth became attached to the East Indies Squadron (later redesignated as theFar East Fleet

The Far East Fleet (also called the Far East Station) was a fleet of the Royal Navy from 1952 to 1971.

During the Second World War, the Eastern Fleet included many ships and personnel from other navies, including the navies of the Netherlands, ...

).

''Exeter'' then stayed on escort duty in the Indian Ocean (primarily off the coast of Africa) and the northern Arabian Sea (where she visited Bombay, India) until 13 October.ADM 53/114258 On that day ''Exeter'' departed Aden for Colombo

Colombo, ( ; , ; , ), is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. The Colombo metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of 5.6 million, and 752,993 within the municipal limits. It is the ...

, British Ceylon

British Ceylon (; ), officially British Settlements and Territories in the Island of Ceylon with its Dependencies from 1802 to 1833, then the Island of Ceylon and its Territories and Dependencies from 1833 to 1931 and finally the Island of Cey ...

) via Bombay

Mumbai ( ; ), also known as Bombay ( ; its official name until 1995), is the capital city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of Maharashtra. Mumbai is the financial centre, financial capital and the list of cities i ...

, British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance in South Asia. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one form or another ...

arriving on 24 October. ''Exeter'' then spent several days in a graving dock and after undocking (on the 29th) conducted exercises off Colombo and visited the Maldives

The Maldives, officially the Republic of Maldives, and historically known as the Maldive Islands, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in South Asia located in the Indian Ocean. The Maldives is southwest of Sri Lanka and India, abou ...

.

Upon return to Trincomalee (Ceylon) from the Maldives on 14 November, ''Exeter'' then departed for Calcutta on the 16th to cover a small two-ship convoy that left Calcutta for Rangoon (Burma) on the 26th and 27th. After the successful completion of that duty she was then tasked to escort another ship from Calcutta to Rangoon on 6 December. However, during that convoy, on 8 December, ''Exeter'' was ordered to urgently proceed to Singapore to reinforce Force Z, as the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War or the Pacific Theatre, was the Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II fought between the Empire of Japan and the Allies of World War II, Allies in East Asia, East and Southeast As ...

had just begun. ''Exeter'' arrived at Singapore during the afternoon of 10 December, too late to support and as they had both been sunk earlier that day, but some of the survivors from these two ships were treated in ''Exeter''s sick bay

A sick bay is a compartment in a ship, or a section of another organisation, such as a school or college, used for medical purposes.

The sick bay contains the ship's medicine chest, which may be divided into separate cabinets, such as a refrige ...

.Cox, p. 109

''Exeter'' thus returned to Colombo the next day (11 December) and spent the next two months – until almost mid-February 1942 – escorting convoys (primarily from Bombay and Colombo) bound for Singapore – which fell to the Japanese on 15 February. During this time, in early 1942, ''Exeter'' was attached to the newly formed ABDA Command, (American-British-Dutch-Australian Command

The American-British-Dutch-Australian (ABDA) Command, or ABDACOM, was the short-lived supreme command for all Allied forces in South East Asia in early 1942, during the Pacific War in World War II. The command consisted of the forces of Austra ...

) which came into being in early January in Singapore, but soon shifted its headquarters to Java in the Dutch East Indies (present day Indonesia).

The Gaspar Strait sortie

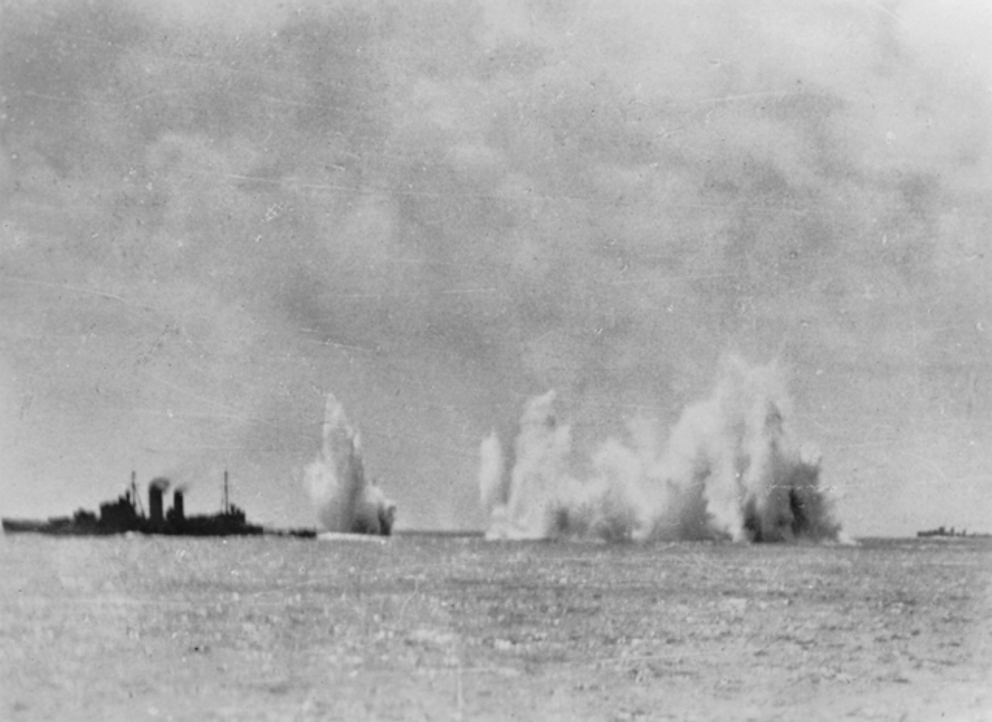

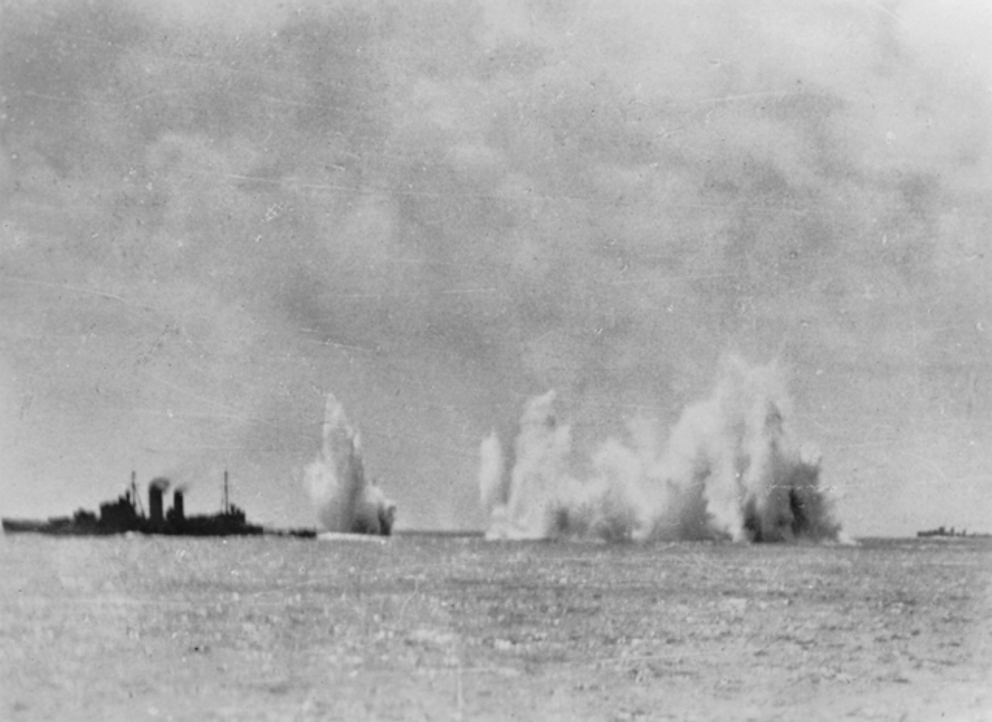

On 13 February Allied reconnaissance aircraft spotted Japanese invasion convoys north of

On 13 February Allied reconnaissance aircraft spotted Japanese invasion convoys north of Bangka Island

Bangka is an island lying east of Sumatra, Indonesia. It is administered under the province of the Bangka Belitung Islands, being one of its namesakes alongside the smaller island of Belitung across the Gaspar Strait. The 9th largest island in ...

and the new commander of ABDA naval forces, Vice Admiral

Vice admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, usually equivalent to lieutenant general and air marshal. A vice admiral is typically senior to a rear admiral and junior to an admiral.

Australia

In the Royal Australian Navy, the rank of Vice ...

Conrad Helfrich of the Royal Netherlands Navy

The Royal Netherlands Navy (, ) is the Navy, maritime service branch of the Netherlands Armed Forces. It traces its history to 8 January 1488, making it the List of navies, third-oldest navy in the world.

During the 17th and early 18th centurie ...

, was ordered to assemble the Allied Striking Force of ''Exeter'' and three Dutch and one Australian light cruisers at Oosthaven on the morning of 14 February. Escorted by six American and three Dutch destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived i ...

s, the force departed that afternoon. The Dutch Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a flag officer rank used by English-speaking navies. In most European navies, the equivalent rank is called counter admiral.

Rear admiral is usually immediately senior to commodore and immediately below vice admiral. It is ...

Karel Doorman

Karel Willem Frederik Marie Doorman (23 April 1889 – 28 February 1942) was a Royal Netherlands Navy officer who during World War II commanded remnants of the short-lived American-British-Dutch-Australian Command naval strike forces in ...

, commanding the force, took his ships through the Gaspar Strait and then northwest towards Bangka Island. While passing through the strait, the Dutch destroyer struck a rock in poor visibility and another Dutch destroyer was tasked to take off her crew. The Japanese spotted the Allied ships around 08:00 and repeatedly attacked them. The first was a group of seven Nakajima B5N

The Nakajima B5N (, World War II Allied names for Japanese aircraft, Allied reporting name "Kate") was the standard Carrier-based aircraft, carrier-based torpedo bomber of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) for much of World War II. It also served ...

"Kate" torpedo bomber

A torpedo bomber is a military aircraft designed primarily to attack ships with aerial torpedoes. Torpedo bombers came into existence just before the World War I, First World War almost as soon as aircraft were built that were capable of carryin ...

s from the light carrier

A light aircraft carrier, or light fleet carrier, is an aircraft carrier smaller than the standard carriers of a navy. The precise definition of the type varies by country; light carriers typically have a complement of aircraft only one-half to ...

that attacked ''Exeter'' with bombs around 10:30. The blast from a near miss badly damaged her Walrus, but the ship was only damaged by shrapnel. They were followed shortly afterwards by a group of 23 Mitsubishi G3M

The was a Japanese bomber and transport aircraft used by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service (IJNAS) during World War II.

The Yokosuka L3Y (Allied reporting name "Tina"), was a transport variant of the aircraft manufactured by the Yokosu ...

"Nell" bombers from the Genzan Air Group

was an aircraft and airbase garrison unit of the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service during the Second Sino-Japanese War and Pacific campaign of World War II.

History

The Genzan Air Group was founded on 15 November 1940 at Genzan, Korea, then a ...

that inflicted no damage as they dropped their bombs from high altitude. Another group of six B5Ns attacked without effect at 11:30.

The repeated aerial attacks persuaded Doorman that further progress was unwise in the face of Japanese aerial supremacy and he ordered his ships to reverse course and head for Tanjung Priok at 12:42. The attacks continued as 27 G3Ms of the Mihoro Air Group then bombed from high altitude. Seven more B5Ns attacked fruitlessly at 14:30; a half-dozen more followed an hour later. The final attack was made by 17 Mitsubishi G4M

The Mitsubishi G4M is a twin-engine, land-based medium bomber formerly manufactured by the Mitsubishi Aircraft Company, a part of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, and operated by the Air Service (IJNAS) of the Imperial Japanese Navy from 1940 to ...

"Betty" bombers of the Kanoya Air Group shortly before dark. The Japanese attacks were almost entirely ineffectual, with no ship reporting anything more than shrapnel damage. In return, allied anti-aircraft fire was moderately effective with most of the attacking bombers damaged by shrapnel. In addition, one G4M crashed while attempting to land, and another was badly damaged upon landing.

First Battle of the Java Sea

On 25 February, Helfrich ordered all available warships to join Doorman's Eastern Striking Force atSurabaya

Surabaya is the capital city of East Java Provinces of Indonesia, province and the List of Indonesian cities by population, second-largest city in Indonesia, after Jakarta. Located on the northeastern corner of Java island, on the Madura Strai ...

. The ''Exeter'' and the Australian light cruiser , escorted by three British destroyers, , , and , set sail at once, leaving behind one Australian cruiser and two destroyers that were short of fuel. After they had arrived the following day, Doorman's entire force of five cruisers and nine destroyers departed Surabaya at 18:30 to patrol off Eastern Java in hopes of intercepting the oncoming invasion convoy which had been spotted earlier that morning. The Japanese were further north than he anticipated and his ships found nothing. His own ships were located at 09:35 on the following morning, 27 February, and were continuously tracked by the Japanese. Doorman ordered a return to Surabaya at 10:30, and his ships were attacked by eight bombers from the Kanoya Air Group at 14:37. They claimed to have made two hits on the ''Jupiter'', but actually they missed the British destroyer. Just as his leading ships were entering harbour, he received reports of enemy ships to the north and Doorman ordered his ships to turn about to intercept them.

Aware of Doorman's movements, the Japanese commander, Rear Admiral Takeo Takagi

was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War II. He was the commander of the IJN 6th Fleet, which oversaw the deployment of all submarines.

Biography

Takagi was a native of Iwaki city, Fukushima prefecture. He was a graduate o ...

, detached the convoy's two escorting destroyer flotilla

A flotilla (from Spanish, meaning a small ''flota'' ( fleet) of ships), or naval flotilla, is a formation of small warships that may be part of a larger fleet.

Composition

A flotilla is usually composed of a homogeneous group of the same cla ...

s, each consisting of a light cruiser and seven destroyers, to intercept the Allied ships in conjunction with his own pair of heavy cruisers ( and ) which were escorted by a pair of destroyers. His heavy cruisers opened fire at long range at 15:47 with little effect. The light cruisers and destroyers closed to ranges between and began firing Type 93 "Long Lance" torpedoes beginning at 16:03. All of these torpedoes failed to damage their targets, although one torpedo hit ''Exeter'' and failed to detonate at 16:35.Grove, p. 93 Three minutes later, ''Haguro'' changed the course of the battle when one of her shells penetrated the British ship's starboard

Port and starboard are Glossary of nautical terms (M-Z), nautical terms for watercraft and spacecraft, referring respectively to the left and right sides of the vessel, when aboard and facing the Bow (watercraft), bow (front).

Vessels with bil ...

aft twin four-inch gun mount before detonating in the 'B' or aft boiler room, knocking six of her boilers off-line and killing 14 of her crew. The ship sheered out of line to avoid another torpedo and slowed, followed by all of the trailing cruisers. Moments later a torpedo fired from ''Haguro'' stuck the Dutch destroyer , breaking her in half and sinking her almost immediately. ''Perth'' laid a smoke screen

A smoke screen is smoke released to mask the movement or location of military units such as infantry, tanks, aircraft, or ships.

Smoke screens are commonly deployed either by a canister (such as a grenade) or generated by a vehicle (such as ...

to protect ''Exeter'' and the Allied ships sorted themselves into separate groups as they attempted to disengage. ''Exeter'' was escorted by one Dutch and all three British destroyers in one group and the other cruisers and the American destroyers formed the other group. The Japanese did not initially press their pursuit as they manoeuvered to use their torpedoes against the crippled ''Exeter'', which could only make , and her escorts.

The Japanese began launching torpedoes beginning at 17:20 at ranges of , but they all missed. For some reason, two Japanese destroyers, and , continued to close before firing their torpedoes at and ''Encounter'' and ''Electra'' pulled out of line to counter-attack. Engaging at close range as they closed, ''Electra'' damaged ''Asagumo'', but was sunk by the Japanese ship at 17:46. Meanwhile, ''Exeter'' continued south to Surabaya, escorted by the Dutch destroyer . Doorman's repeated unsuccessful, and ultimately fatal, attempts to reach the transports concentrated the Japanese on the task of protecting the transports and allowed the damaged British cruiser to reach harbour.

Second Battle of the Java Sea

The following day, after making temporary repairs and refuelling, the ''Exeter'', escorted by ''Encounter'' and the American destroyer , was ordered to steam to Colombo, via the

The following day, after making temporary repairs and refuelling, the ''Exeter'', escorted by ''Encounter'' and the American destroyer , was ordered to steam to Colombo, via the Sunda Strait

The Sunda Strait () is the strait between the Indonesian islands of Java island, Java and Sumatra. It connects the Java Sea with the Indian Ocean.

Etymology

The strait takes its name from the Sunda Kingdom, which ruled the western portion of Ja ...

. They departed on the evening of 28 February, but they were intercepted by the Japanese heavy cruisers ''Nachi'', ''Haguro'', , and , and by the destroyers , , , and on the morning of 1 March.

At about 0800, the British ships spotted two of the Japanese cruisers, one of which launched its spotting floatplanes. Two others were seen closing in, and both launched their aircraft before opening fire at about 09:30.Shores, Cull & Izawa 1993, p. 306 The Allied ships laid smoke and turned away to the east with the Japanese to their north and south.Dull, p. 87 ''Exeter'' was able to reach a speed of before the first hit on her detonated in her 'A', or forward, boiler room and catastrophically knocked out all power around 11:20. Now defenseless as no guns could train or traverse, and wanting to save as many lives as he could, and to avoid the ship's capture by the Japanese forces, Captain Gordon ordered the ship to be scuttled. As a result, ''Exeter'' began listing to port, and that list was said to be at "a considerable angle" by the time the abandonment was completed. Sensing a kill, the Japanese destroyers closed in and fired torpedoes, two of which (out of a total of 18 fired by Japanese combatants) from the ''Inazuma'', hit the ship – starboard amidships, and starboard just forward of A turret, as confirmed when the wreck was first discovered in 2007. As a result, ''Exeter'' rapidly righted herself, paused briefly, and then capsized to starboard. ''Encounter'' and ''Pope'' were also lost; ''Encounter'' approximately fifteen minutes after ''Exeter'', while ''Pope'' temporarily survived the initial melee, only to be sunk a couple of hours later. Japanese B5N Type-97s armed with one and four bombs assisted in the sinking of ''Pope'', already crippled by bombing from seaplanes and land-based air, and closed in to make a level bombing attack. No direct hits were scored, but several more near-misses hastened the abandonment and scuttling of the vessel, and she was finished off by gunfire with the late arrival of the two IJN cruisers ''Ashigara'' and ''Myoko''.

The Japanese rescued 652 men of the crew of ''Exeter'', including her captain, who became prisoners of war.

Wreck site

The wreck was discovered and positively identified by a group of exploration divers specifically searching for ''Exeter'' aboard MV ''Empress'' on 21 February 2007. The wreck was found lying on its starboard side in Indonesian waters at a depth of about , north-west of

The wreck was discovered and positively identified by a group of exploration divers specifically searching for ''Exeter'' aboard MV ''Empress'' on 21 February 2007. The wreck was found lying on its starboard side in Indonesian waters at a depth of about , north-west of Bawean Island

Bawean () is an island of Indonesia located approximately north of Surabaya in the Java Sea, off the coast of Java. It is administered by Gresik Regency of East Java province. It is approximately in diameter and is circumnavigated by a sing ...

– some from the estimated sinking position given by Captain Gordon after the war. In July 2008, performed a memorial service over the wreck of ''Exeter''. Aboard, along with several British dignitaries and high ranking naval officers, were a BBC film crew and four of HMS ''Exeter''s veteran survivors, and one of the 2007 wreck discovery dive team representing the other three dive team members. Her wreck, a British war grave, had been destroyed by illegal salvagers by the time another expedition surveyed the site in 2016.

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* *External links

* * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Exeter (68) York-class cruisers Ships built in Plymouth, Devon 1929 ships World War II cruisers of the United Kingdom Battle of the River Plate World War II shipwrecks in the Java Sea Maritime incidents in March 1942