Genghis Khan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Genghis Khan (born Temüjin; August 1227), also known as Chinggis Khan, was the founder and first khan of the

Temüjin was born into the

Temüjin was born into the

Temüjin returned to Dei Sechen to marry Börte when he reached the

Temüjin returned to Dei Sechen to marry Börte when he reached the

During the following years, Temüjin and Toghrul campaigned against the Merkits, the Naimans, and the Tatars; sometimes separately and sometimes together. In around 1201, a collection of dissatisfied tribes including the Onggirat, the Tayichiud, and the Tatars swore to break the domination of the Borjigin-Kereit alliance, electing Jamukha as their leader and gurkhan (). After some initial successes, Temüjin and Toghrul routed this loose confederation at Yedi Qunan, and Jamukha was forced to beg for Toghrul's clemency. Desiring complete supremacy in eastern Mongolia, Temüjin defeated first the Tayichiud and then, in 1202, the Tatars; after both campaigns, he executed the clan leaders and took the remaining warriors into his service. These included Sorkan-Shira, who had come to his aid previously, and a young warrior named Jebe, who, by killing Temüjin's horse and refusing to hide that fact, had displayed martial ability and personal courage.

The absorption of the Tatars left three military powers in the steppe: the Naimans in the west, the Mongols in the east, and the Kereit in between. Seeking to cement his position, Temüjin proposed that his son Jochi marry one of Toghrul's daughters. Led by Toghrul's son Senggum, the Kereit elite believed the proposal to be an attempt to gain control over their tribe, while the doubts over Jochi's parentage would have offended them further. In addition, Jamukha drew attention to the threat Temüjin posed to the traditional steppe

During the following years, Temüjin and Toghrul campaigned against the Merkits, the Naimans, and the Tatars; sometimes separately and sometimes together. In around 1201, a collection of dissatisfied tribes including the Onggirat, the Tayichiud, and the Tatars swore to break the domination of the Borjigin-Kereit alliance, electing Jamukha as their leader and gurkhan (). After some initial successes, Temüjin and Toghrul routed this loose confederation at Yedi Qunan, and Jamukha was forced to beg for Toghrul's clemency. Desiring complete supremacy in eastern Mongolia, Temüjin defeated first the Tayichiud and then, in 1202, the Tatars; after both campaigns, he executed the clan leaders and took the remaining warriors into his service. These included Sorkan-Shira, who had come to his aid previously, and a young warrior named Jebe, who, by killing Temüjin's horse and refusing to hide that fact, had displayed martial ability and personal courage.

The absorption of the Tatars left three military powers in the steppe: the Naimans in the west, the Mongols in the east, and the Kereit in between. Seeking to cement his position, Temüjin proposed that his son Jochi marry one of Toghrul's daughters. Led by Toghrul's son Senggum, the Kereit elite believed the proposal to be an attempt to gain control over their tribe, while the doubts over Jochi's parentage would have offended them further. In addition, Jamukha drew attention to the threat Temüjin posed to the traditional steppe

The Mongols had started raiding the border settlements of the Tangut-led Western Xia kingdom in 1205, ostensibly in retaliation for allowing Senggum, Toghrul's son, refuge. More prosaic explanations include rejuvenating the depleted Mongol economy with an influx of fresh goods and

The Mongols had started raiding the border settlements of the Tangut-led Western Xia kingdom in 1205, ostensibly in retaliation for allowing Senggum, Toghrul's son, refuge. More prosaic explanations include rejuvenating the depleted Mongol economy with an influx of fresh goods and

Genghis had now attained complete control of the eastern portion of the

Genghis had now attained complete control of the eastern portion of the

Serving as

Serving as

Genghis Khan left a vast and controversial legacy. His unification of the Mongol tribes and his foundation of the largest contiguous state in world history "permanently alter dthe worldview of European, Islamic, ndEast Asian civilizations", according to Atwood. His conquests enabled the creation of

Genghis Khan left a vast and controversial legacy. His unification of the Mongol tribes and his foundation of the largest contiguous state in world history "permanently alter dthe worldview of European, Islamic, ndEast Asian civilizations", according to Atwood. His conquests enabled the creation of

Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire was the List of largest empires, largest contiguous empire in human history, history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Euro ...

. After spending most of his life uniting the Mongol tribes, he launched a series of military campaigns, conquering large parts of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

and Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

.

Born between 1155 and 1167 and given the name Temüjin, he was the eldest child of Yesugei, a Mongol chieftain of the Borjigin clan, and his wife Hö'elün. When Temüjin was eight, his father died and his family was abandoned by its tribe. Reduced to near-poverty, Temüjin killed his older half-brother to secure his familial position. His charismatic personality helped to attract his first followers and to form alliances with two prominent steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without closed forests except near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the tropical and subtropica ...

leaders named Jamukha

Jamukha (), a military and political leader of the Jadaran tribe who was proclaimed Gurkhan, ''Gur Khan'' ('Universal Ruler') in 1201 by opposing factions, was a principal rival to Genghis Khan, Temüjin (proclaimed Genghis Khan in 1206) during ...

and Toghrul

Toghrul ( ''Tooril han''; ), also known as Wang Khan or Ong Khan ( ''Wan han''; ; died 1203), was a Khan (title), khan of the Keraites. He was the blood brother (anda (Mongol), anda) of the Mongol chief Yesugei and served as an important early ...

; they worked together to retrieve Temüjin's newlywed wife Börte, who had been kidnapped by raiders. As his reputation grew, his relationship with Jamukha deteriorated into open warfare. Temüjin was badly defeated in , and may have spent the following years as a subject of the Jin dynasty; upon reemerging in 1196, he swiftly began gaining power. Toghrul came to view Temüjin as a threat and launched a surprise attack on him in 1203. Temüjin retreated, then regrouped and overpowered Toghrul; after defeating the Naiman tribe and executing Jamukha, he was left as the sole ruler on the Mongolian steppe.

Temüjin formally adopted the title "Genghis Khan", the meaning of which is uncertain, at an assembly in 1206. Carrying out reforms designed to ensure long-term stability, he transformed the Mongols' tribal structure into an integrated meritocracy dedicated to the service of the ruling family. After thwarting a coup attempt from a powerful shaman

Shamanism is a spiritual practice that involves a practitioner (shaman) interacting with the spirit world through altered states of consciousness, such as trance. The goal of this is usually to direct spirits or spiritual energies into ...

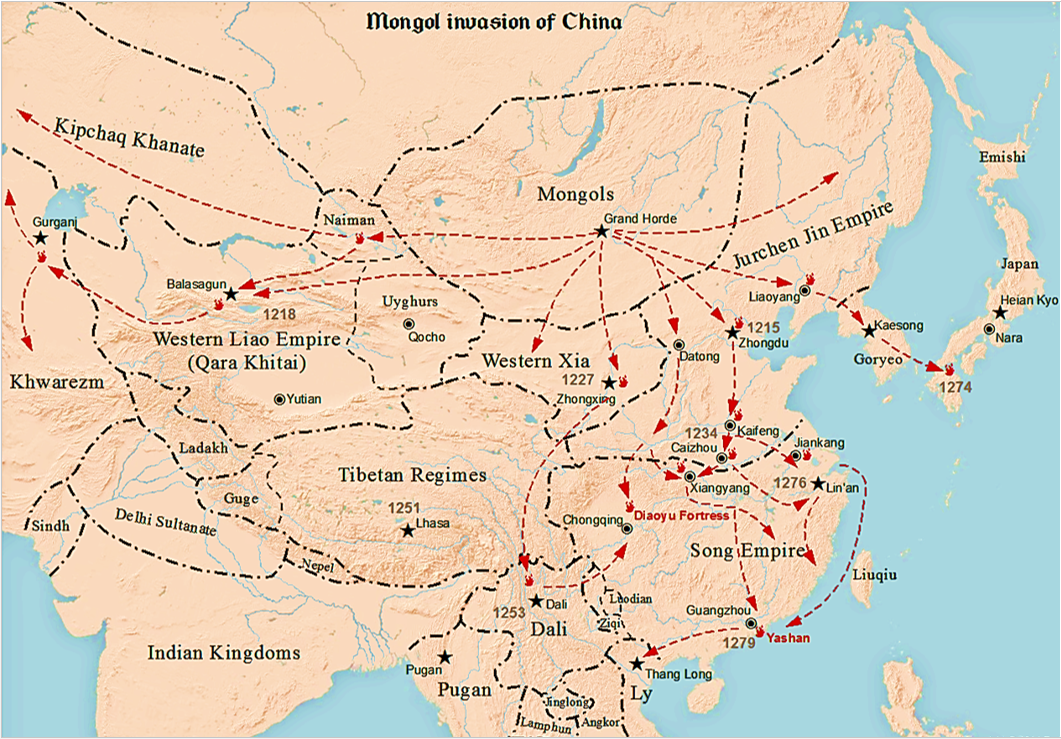

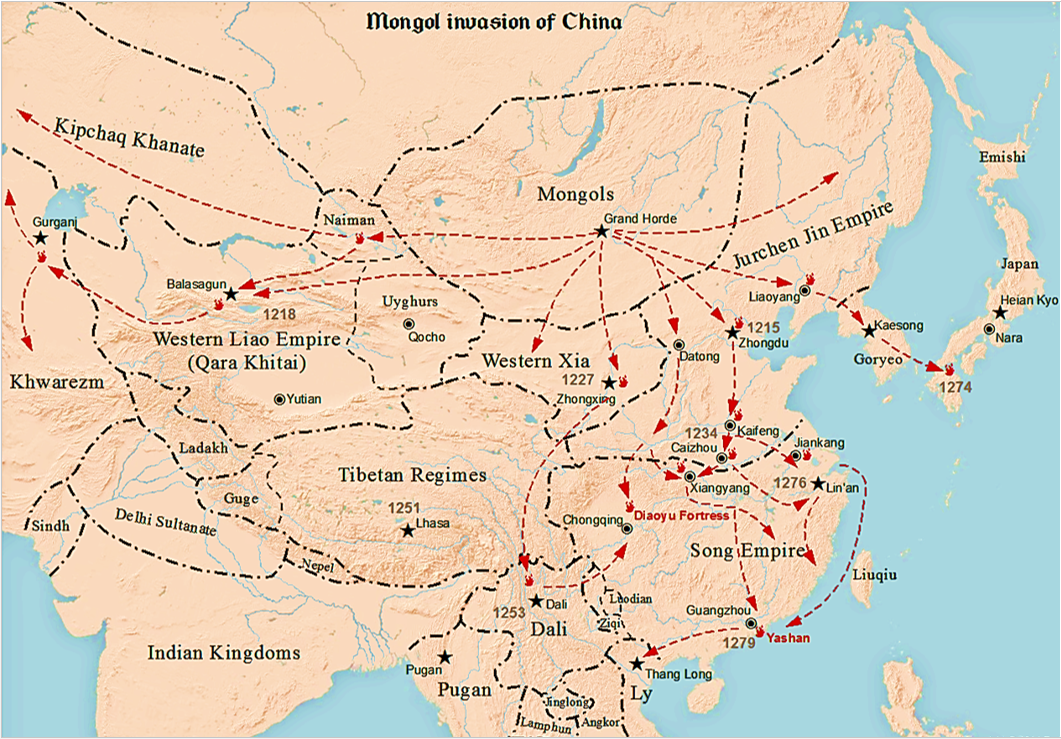

, Genghis began to consolidate his power. In 1209, he led a large-scale raid into the neighbouring Western Xia, who agreed to Mongol terms the following year. He then launched a campaign against the Jin dynasty, which lasted for four years and ended in 1215 with the capture of the Jin capital Zhongdu. His general Jebe annexed the Central Asian state of Qara Khitai in 1218. Genghis was provoked to invade the Khwarazmian Empire

The Khwarazmian Empire (), or simply Khwarazm, was a culturally Persianate society, Persianate, Sunni Muslim empire of Turkic peoples, Turkic ''mamluk'' origin. Khwarazmians ruled large parts of present-day Central Asia, Afghanistan, and Iran ...

the following year by the execution of his envoys; the campaign toppled the Khwarazmian state and devastated the regions of Transoxiana

Transoxiana or Transoxania (, now called the Amu Darya) is the Latin name for the region and civilization located in lower Central Asia roughly corresponding to eastern Uzbekistan, western Tajikistan, parts of southern Kazakhstan, parts of Tu ...

and Khorasan, while Jebe and his colleague Subutai

Subutai (c. 1175–1248) was a Mongol general and the primary military strategist of Genghis Khan and Ögedei Khan. He ultimately directed more than 20 campaigns, during which he conquered more territory than any other commander in history a ...

led an expedition that reached Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

and Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rus', also known as Kyivan Rus,.

* was the first East Slavs, East Slavic state and later an amalgam of principalities in Eastern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical At ...

. In 1227, Genghis died while subduing the rebellious Western Xia; following a two-year interregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of revolutionary breach of legal continuity, discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one m ...

, his third son and heir Ögedei acceded to the throne in 1229.

Genghis Khan remains a controversial figure. He was generous and intensely loyal to his followers, but ruthless towards his enemies. He welcomed advice from diverse sources in his quest for world domination, for which he believed the shamanic supreme deity Tengri

Tengri (; Old Uyghur: ; Middle Turkic: ; ; ; ; ; ; ; Proto-Turkic: / ; Mongolian script: , ; , ; , ) is the all-encompassing God of Heaven in the traditional Turkic, Yeniseian, Mongolic, and various other nomadic religious beliefs. So ...

had destined him. The Mongol army under Genghis killed millions of people, yet his conquests also facilitated unprecedented commercial and cultural exchange over a vast geographical area. He is remembered as a backwards, savage tyrant in Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

and the Arab world

The Arab world ( '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, comprises a large group of countries, mainly located in West Asia and North Africa. While the majority of people in ...

, while recent Western scholarship has begun to reassess its previous view of him as a barbarian warlord. He was posthumously deified in Mongolia

Mongolia is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south and southeast. It covers an area of , with a population of 3.5 million, making it the world's List of countries and dependencies by po ...

; modern Mongolians recognise him as the founding father of their nation.

Name and title

There is no universal romanisation system used for Mongolian; as a result, modern spellings of Mongolian names vary greatly and may result in considerably different pronunciations from the original. Thehonorific

An honorific is a title that conveys esteem, courtesy, or respect for position or rank when used in addressing or referring to a person. Sometimes, the term "honorific" is used in a more specific sense to refer to an Honorary title (academic), h ...

most commonly rendered as "Genghis" ultimately derives from the Mongolian , which may be romanised as . This was adapted into Chinese as , and into Persian as . As Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

lacks a sound similar to , represented in the Mongolian and Persian romanisations by , writers transcribed the name as , while Syriac authors used .

In addition to "Genghis", introduced into English during the 18th century based on a misreading of Persian sources, modern English spellings include "Chinggis", "Chingis", "Jinghis", and "Jengiz". His birth name "Temüjin" (; ) is sometimes also spelled "Temuchin" in English.

When Genghis's grandson Kublai Khan established the Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty ( ; zh, c=元朝, p=Yuáncháo), officially the Great Yuan (; Mongolian language, Mongolian: , , literally 'Great Yuan State'), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after Div ...

in 1271, he bestowed the temple name ''Taizu'' (, meaning 'Supreme Progenitor') and the posthumous name

A posthumous name is an honorary Personal name, name given mainly to revered dead people in East Asian cultural sphere, East Asian culture. It is predominantly used in Asian countries such as China, Korea, Vietnam, Japan, Malaysia and Thailand. ...

''Shengwu Huangdi'' (, meaning 'Holy-Martial Emperor') upon his grandfather. Kublai's great-grandson Külüg Khan

Külüg Khan (Mongolian language, Mongolian: Хүлэг; Mongolian script: ; ), born Khayishan (Mongolian: Хайсан ; , , meaning "wall"), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Wuzong of Yuan () (August 4, 1281 – January 27, 1311), ...

later expanded this title into ''Fatian Qiyun Shengwu Huangdi'' (, meaning 'Interpreter of the Heavenly Law, Initiator of the Good Fortune, Holy-Martial Emperor').

Sources

As the sources are written in more than a dozen languages from across Eurasia, modern historians have found it difficult to compile information on the life of Genghis Khan. All accounts of his adolescence and rise to power derive from two Mongolian-language sources—the '' Secret History of the Mongols'', and the '' Altan Debter'' (''Golden Book''). The latter, now lost, served as inspiration for two Chinese chronicles—the 14th-century '' History of Yuan'' and the '' Shengwu qinzheng lu'' (''Campaigns of Genghis Khan''). The ''History of Yuan'', while poorly edited, provides a large amount of detail on individual campaigns and people; the ''Shengwu'' is more disciplined in its chronology, but does not criticise Genghis and occasionally contains errors. The ''Secret History'' survived through beingtransliterated

Transliteration is a type of conversion of a text from one writing system, script to another that involves swapping Letter (alphabet), letters (thus ''wikt:trans-#Prefix, trans-'' + ''wikt:littera#Latin, liter-'') in predictable ways, such as ...

into Chinese characters

Chinese characters are logographs used Written Chinese, to write the Chinese languages and others from regions historically influenced by Chinese culture. Of the four independently invented writing systems accepted by scholars, they represe ...

during the 14th and 15th centuries. Its historicity has been disputed: the 20th-century sinologist Arthur Waley

Arthur David Waley (born Arthur David Schloss, 19 August 188927 June 1966) was an English orientalist and sinologist who achieved both popular and scholarly acclaim for his translations of Chinese and Japanese poetry. Among his honours were ...

considered it a literary work with no historiographical value, but more recent historians have given it much more credence. Although it is clear that its chronology is suspect and that some passages were removed or modified for better narration, the ''Secret History'' is valued highly because the anonymous author is often critical of Genghis Khan: in addition to presenting him as indecisive and as having a phobia of dogs, the ''Secret History'' also recounts taboo events such as his fratricide and the possibility of his son Jochi's illegitimacy.

Multiple chronicles in Persian have also survived, which display a mix of positive and negative attitudes towards Genghis Khan and the Mongols. Both Minhaj-i Siraj Juzjani and Ata-Malik Juvayni completed their respective histories in 1260. Juzjani was an eyewitness to the brutality of the Mongol conquests, and the hostility of his chronicle reflects his experiences. His contemporary Juvayni, who had travelled twice to Mongolia and attained a high position in the administration of a Mongol successor state, was more sympathetic; his account is the most reliable for Genghis Khan's western campaigns. The most important Persian source is the '' Jami' al-tawarikh'' (''Compendium of Chronicles'') compiled by Rashid al-Din on the order of Genghis's descendant Ghazan in the early 14th century. Ghazan allowed Rashid privileged access to both confidential Mongol sources such as the ''Altan Debter'' and to experts on the Mongol oral tradition, including Kublai Khan's ambassador Bolad Chingsang. As he was writing an official chronicle, Rashid censored inconvenient or taboo details.

There are many other contemporary histories which include additional information on Genghis Khan and the Mongols, although their neutrality and reliability are often suspect. Additional Chinese sources include the chronicles of the dynasties conquered by the Mongols, and the Song diplomat Zhao Hong, who visited the Mongols in 1221. Arabic sources include a contemporary biography of the Khwarazmian prince Jalal al-Din by his companion al-Nasawi. There are also several later Christian chronicles, including the '' Georgian Chronicles'', and works by European travellers such as Carpini and Marco Polo

Marco Polo (; ; ; 8 January 1324) was a Republic of Venice, Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in ''The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known a ...

.

Early life

Birth and childhood

The year of Temüjin's birth is disputed, as historians favour different dates: 1155, 1162 or 1167. Some traditions place his birth in the Year of the Pig, which was either 1155 or 1167. While a dating to 1155 is supported by the writings of both Zhao Hong and Rashid al-Din, other major sources such as the ''History of Yuan'' and the ''Shengwu'' favour the year 1162. The 1167 dating, favoured by the sinologist Paul Pelliot, is derived from a minor source—a text of the Yuan artist Yang Weizhen—but is more compatible with the events of Genghis Khan's life than a 1155 placement, which implies that he did not have children until after the age of thirty and continued actively campaigning into his seventh decade. 1162 is the date accepted by most historians; the historian Paul Ratchnevsky noted that Temüjin himself may not have known the truth. The location of Temüjin's birth, which the ''Secret History'' records as Delüün Boldog on the Onon River, is similarly debated: it has been placed at either Dadal in Khentii Province or in southern Agin-Buryat Okrug, Russia. Temüjin was born into the

Temüjin was born into the Borjigin

A Borjigin is a member of the Mongol sub-clan that started with Bodonchar Munkhag of the Kiyat clan. Yesugei's descendants were thus said to be Kiyat-Borjigin. The senior Borjigids provided ruling princes for Mongolia and Inner Mongolia u ...

clan of the Mongol tribe to Yesügei, a chieftain who claimed descent from the legendary warlord Bodonchar Munkhag, and his principal wife Hö'elün, originally of the Olkhonud clan, whom Yesügei had abducted from her Merkit bridegroom Chiledu. The origin of his birth name is contested: the earliest traditions hold that his father had just returned from a successful campaign against the Tatars

Tatars ( )Tatar

in the Collins English Dictionary are a group of Turkic peoples across Eas ...

with a captive named Temüchin-uge, after whom he named the newborn in celebration of his victory, while later traditions highlight the in the Collins English Dictionary are a group of Turkic peoples across Eas ...

root

In vascular plants, the roots are the plant organ, organs of a plant that are modified to provide anchorage for the plant and take in water and nutrients into the plant body, which allows plants to grow taller and faster. They are most often bel ...

(meaning 'iron') and connect to theories that "Temüjin" means 'blacksmith'.

Several legends surround Temüjin's birth. The most prominent is that he was born clutching a blood clot in his hand, a motif in Asian folklore indicating the child would be a warrior. Others claimed that Hö'elün was impregnated by a ray of light which announced the child's destiny, a legend which echoed that of the mythical Borjigin ancestor Alan Gua. Yesügei and Hö'elün had three younger sons after Temüjin: Qasar, Hachiun, and Temüge, as well as one daughter, Temülün. Temüjin also had two half-brothers, Behter and Belgutei, from Yesügei's secondary wife Sochigel, whose identity is uncertain. The siblings grew up at Yesugei's main camp on the banks of the Onon, where they learned how to ride a horse and shoot a bow.

When Temüjin was eight years old, his father decided to betroth him to a suitable girl. Yesügei took his heir to the pastures of Hö'elün's prestigious Onggirat tribe, which had intermarried with the Mongols on many previous occasions. There, he arranged a betrothal between Temüjin and Börte, the daughter of an Onggirat chieftain named Dei Sechen. As the betrothal meant Yesügei would gain a powerful ally and as Börte commanded a high bride price

Bride price, bride-dowry, bride-wealth, bride service or bride token, is money, property, or other form of wealth paid by a groom or his family to the woman or the family of the woman he will be married to or is just about to marry. Bride dowry ...

, Dei Sechen held the stronger negotiating position, and demanded that Temüjin remain in his household to work off his future debt. Accepting this condition, Yesügei requested a meal from a band of Tatars he encountered while riding homewards alone, relying on the steppe tradition of hospitality to strangers. However, the Tatars recognised their old enemy and slipped poison into his food. Yesügei gradually sickened but managed to return home; close to death, he requested a trusted retainer called Münglig to retrieve Temüjin from the Onggirat. He died soon after.

Adolescence

Yesügei's death shattered the unity of his people, which included members of the Borjigin, Tayichiud, and other clans. As Temüjin was not yet ten and Behter around two years older, neither was considered experienced enough to rule. The Tayichiud faction excluded Hö'elün from theancestor worship

The veneration of the dead, including one's ancestors, is based on love and respect for the deceased. In some cultures, it is related to beliefs that the dead have a continued existence, and may possess the ability to influence the fortune of t ...

ceremonies which followed a ruler's death and soon abandoned her camp. The ''Secret History'' relates that the entire Borjigin clan followed, despite Hö'elün's attempts to shame them into staying by appealing to their honour. Rashid al-Din and the ''Shengwu'' however imply that Yesügei's brothers stood by the widow. It is possible that Hö'elün may have refused to join in levirate marriage

Levirate marriage is a type of marriage in which the brother of a deceased man is obliged to marry his brother's widow. Levirate marriage has been practiced by societies with a strong clan structure in which exogamous marriage (i.e. marriage o ...

with one, resulting in later tensions, or that the author of the ''Secret History'' dramatised the situation. All the sources agree that most of Yesügei's people renounced his family in favour of the Tayichiuds and that Hö'elün's family were reduced to a much harsher life. Taking up a hunter-gatherer

A hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living in a community, or according to an ancestrally derived Lifestyle, lifestyle, in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local naturally occurring sources, esp ...

lifestyle, they collected roots and nuts, hunted for small animals, and caught fish.

Tensions developed as the children grew older. Both Temüjin and Behter had claims to be their father's heir: although Temüjin was the child of Yesügei's chief wife, Behter was at least two years his senior. There was even the possibility that, as permitted under levirate law, Behter could marry Hö'elün upon attaining his majority

A majority is more than half of a total; however, the term is commonly used with other meanings, as explained in the "#Related terms, Related terms" section below.

It is a subset of a Set (mathematics), set consisting of more than half of the se ...

and become Temüjin's stepfather. As the friction, exacerbated by frequent disputes over the division of hunting spoils, intensified, Temüjin and his younger brother Qasar ambushed and killed Behter. This taboo act was omitted from the official chronicles but not from the ''Secret History'', which recounts that Hö'elün angrily reprimanded her sons. Behter's younger full-brother Belgutei did not seek vengeance, and became one of Temüjin's highest-ranking followers alongside Qasar. Around this time, Temüjin developed a close friendship with Jamukha

Jamukha (), a military and political leader of the Jadaran tribe who was proclaimed Gurkhan, ''Gur Khan'' ('Universal Ruler') in 1201 by opposing factions, was a principal rival to Genghis Khan, Temüjin (proclaimed Genghis Khan in 1206) during ...

, another boy of aristocratic descent; the ''Secret History'' notes that they exchanged knucklebones and arrows as gifts and swore the pact—the traditional oath of Mongol blood brother

Blood brother can refer to two or more people not related by birth who have sworn loyalty to each other. This is in modern times usually done in a ceremony, known as a blood oath, where each person makes a small cut, usually on a finger, han ...

s–at eleven.

As the family lacked allies, Temüjin was taken prisoner on multiple occasions. Captured by the Tayichiuds, he escaped during a feast and hid first in the Onon and then in the tent of Sorkan-Shira, a man who had seen him in the river and not raised the alarm. Sorkan-Shira sheltered Temüjin for three days at great personal risk before helping him to escape. Temüjin was assisted on another occasion by Bo'orchu, an adolescent who aided him in retrieving stolen horses. Soon afterwards, Bo'orchu joined Temüjin's camp as his first ('personal companion'; ). These incidents, related by the ''Secret History'', are indicative of the emphasis its author put on Genghis' personal charisma.

Rise to power

Early campaigns

Temüjin returned to Dei Sechen to marry Börte when he reached the

Temüjin returned to Dei Sechen to marry Börte when he reached the age of majority

The age of majority is the threshold of legal adulthood as recognized or declared in law. It is the moment when a person ceases to be considered a minor (law), minor, and assumes legal control over their person, actions, and decisions, thus te ...

at fifteen. Delighted to see the son-in-law he feared had died, Dei Sechen consented to the marriage and accompanied the newlyweds back to Temüjin's camp; his wife Čotan presented Hö'elün with an expensive sable cloak. Seeking a patron, Temüjin chose to regift the cloak to Toghrul

Toghrul ( ''Tooril han''; ), also known as Wang Khan or Ong Khan ( ''Wan han''; ; died 1203), was a Khan (title), khan of the Keraites. He was the blood brother (anda (Mongol), anda) of the Mongol chief Yesugei and served as an important early ...

, khan (ruler) of the Kerait tribe, who had fought alongside Yesügei and sworn the pact with him. Toghrul ruled a vast territory in central Mongolia but distrusted many of his followers. In need of loyal replacements, he was delighted with the valuable gift and welcomed Temüjin into his protection. The two grew close, and Temüjin began to build a following, as such as Jelme entered into his service. Temüjin and Börte had their first child, a daughter named Qojin, around this time.

Soon afterwards, seeking revenge for Yesügei's abduction of Hö'elün, around 300 Merkits raided Temüjin's camp. While Temüjin and his brothers were able to hide on Burkhan Khaldun mountain, Börte and Sochigel were abducted. In accordance with levirate law, Börte was given in marriage to the younger brother of the now-deceased Chiledu. Temüjin appealed for aid from Toghrul and his childhood Jamukha, who had risen to become chief of the Jadaran tribe. Both chiefs were willing to field armies of 20,000 warriors, and with Jamukha in command, the campaign was soon won. A now-pregnant Börte was recovered successfully and soon gave birth to a son, Jochi

Jochi (; ), also spelled Jüchi, was a prince of the early Mongol Empire. His life was marked by controversy over the circumstances of his birth and culminated in his estrangement from his family. He was nevertheless a prominent Military of the ...

; although Temüjin raised him as his own, questions over his true paternity followed Jochi throughout his life. This is narrated in the ''Secret History'' and contrasts with Rashid al-Din's account, which protects the family's reputation by removing any hint of illegitimacy. Over the next decade and a half, Temüjin and Börte had three more sons ( Chagatai, Ögedei, and Tolui) and four more daughters ( Checheyigen, Alaqa, Tümelün, and Al-Altan).

The followers of Temüjin and Jamukha camped together for a year and a half, during which their leaders reforged their pact and slept together under one blanket, according to the ''Secret History''. The source presents this period as close friends bonding, but Ratchnevsky questioned if Temüjin actually entered into Jamukha's service in return for the assistance with the Merkits. Tensions arose and the two leaders parted, ostensibly on account of a cryptic remark made by Jamukha on the subject of camping; in any case, Temüjin followed the advice of Hö'elün and Börte and began to build an independent following. The major tribal rulers remained with Jamukha, but forty-one leaders gave their support to Temüjin along with many commoners: these included Subutai

Subutai (c. 1175–1248) was a Mongol general and the primary military strategist of Genghis Khan and Ögedei Khan. He ultimately directed more than 20 campaigns, during which he conquered more territory than any other commander in history a ...

and others of the Uriankhai, the Barulas, the Olkhonuds, and many more. Many were attracted by Temüjin's reputation as a fair and generous lord who could offer better lives, while his shamans prophesied that heaven had allocated him a great destiny.

Temüjin was soon acclaimed by his close followers as khan of the Mongols. Toghrul was pleased at his vassal's elevation but Jamukha was resentful. Tensions escalated into open hostility, and in around 1187 the two leaders clashed in battle at Dalan Baljut: the two forces were evenly matched but Temüjin suffered a clear defeat. Later chroniclers including Rashid al-Din instead state that he was victorious but their accounts contradict themselves and each other.

Modern historians such as Ratchnevsky and Timothy May consider it very likely that Temüjin spent a large portion of the decade following the clash at Dalan Baljut as a servant of the Jurchen Jin dynasty in North China

North China () is a list of regions of China, geographical region of the People's Republic of China, consisting of five province-level divisions of China, provincial-level administrative divisions, namely the direct-administered municipalities ...

. Zhao Hong recorded that the future Genghis Khan spent several years as a slave of the Jin. Formerly seen as an expression of nationalistic arrogance, the statement is now thought to be based in fact, especially as no other source convincingly explains Temüjin's activities between Dalan Baljut and . Taking refuge across the border was a common practice both for disaffected steppe leaders and disgraced Chinese officials. Temüjin's reemergence having retained significant power indicates that he probably profited in the service of the Jin. As he later overthrew that state, such an episode, detrimental to Mongol prestige, was omitted from all their sources. Zhao Hong was bound by no such taboos.

Defeating rivals

The sources do not agree on the events of Temüjin's return to the steppe. In early summer 1196, he participated in a joint campaign with the Jin against the Tatars, who had begun to act contrary to Jin interests. As a reward, the Jin awarded him the honorific , the meaning of which probably approximated "commander of hundreds" in Jurchen. At around the same time, he assisted Toghrul with reclaiming the lordship of the Kereit, which had been usurped by one of Toghrul's relatives with the support of the powerful Naiman tribe. The actions of 1196 fundamentally changed Temüjin's position in the steppe—although nominally still Toghrul's vassal, he was ''de facto'' an equal ally. Jamukha behaved cruelly following his victory at Dalan Baljut—he allegedly boiled seventy prisoners alive and humiliated the corpses of leaders who had opposed him. A number of disaffected followers, including Yesügei's follower Münglig and his sons, defected to Temüjin as a consequence; they were also probably attracted by his newfound wealth. Temüjin subdued the disobedient Jurkin tribe that had previously offended him at a feast and refused to participate in the Tatar campaign. After executing their leaders, he had Belgutei symbolically break a leading Jurkin's back in a stagedwrestling

Wrestling is a martial art, combat sport, and form of entertainment that involves grappling with an opponent and striving to obtain a position of advantage through different throws or techniques, within a given ruleset. Wrestling involves di ...

match in retribution. This latter incident, which contravened Mongol customs of justice, was only noted by the author of the ''Secret History'', who openly disapproved. These events occurred c. 1197.

During the following years, Temüjin and Toghrul campaigned against the Merkits, the Naimans, and the Tatars; sometimes separately and sometimes together. In around 1201, a collection of dissatisfied tribes including the Onggirat, the Tayichiud, and the Tatars swore to break the domination of the Borjigin-Kereit alliance, electing Jamukha as their leader and gurkhan (). After some initial successes, Temüjin and Toghrul routed this loose confederation at Yedi Qunan, and Jamukha was forced to beg for Toghrul's clemency. Desiring complete supremacy in eastern Mongolia, Temüjin defeated first the Tayichiud and then, in 1202, the Tatars; after both campaigns, he executed the clan leaders and took the remaining warriors into his service. These included Sorkan-Shira, who had come to his aid previously, and a young warrior named Jebe, who, by killing Temüjin's horse and refusing to hide that fact, had displayed martial ability and personal courage.

The absorption of the Tatars left three military powers in the steppe: the Naimans in the west, the Mongols in the east, and the Kereit in between. Seeking to cement his position, Temüjin proposed that his son Jochi marry one of Toghrul's daughters. Led by Toghrul's son Senggum, the Kereit elite believed the proposal to be an attempt to gain control over their tribe, while the doubts over Jochi's parentage would have offended them further. In addition, Jamukha drew attention to the threat Temüjin posed to the traditional steppe

During the following years, Temüjin and Toghrul campaigned against the Merkits, the Naimans, and the Tatars; sometimes separately and sometimes together. In around 1201, a collection of dissatisfied tribes including the Onggirat, the Tayichiud, and the Tatars swore to break the domination of the Borjigin-Kereit alliance, electing Jamukha as their leader and gurkhan (). After some initial successes, Temüjin and Toghrul routed this loose confederation at Yedi Qunan, and Jamukha was forced to beg for Toghrul's clemency. Desiring complete supremacy in eastern Mongolia, Temüjin defeated first the Tayichiud and then, in 1202, the Tatars; after both campaigns, he executed the clan leaders and took the remaining warriors into his service. These included Sorkan-Shira, who had come to his aid previously, and a young warrior named Jebe, who, by killing Temüjin's horse and refusing to hide that fact, had displayed martial ability and personal courage.

The absorption of the Tatars left three military powers in the steppe: the Naimans in the west, the Mongols in the east, and the Kereit in between. Seeking to cement his position, Temüjin proposed that his son Jochi marry one of Toghrul's daughters. Led by Toghrul's son Senggum, the Kereit elite believed the proposal to be an attempt to gain control over their tribe, while the doubts over Jochi's parentage would have offended them further. In addition, Jamukha drew attention to the threat Temüjin posed to the traditional steppe aristocracy

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense Economy, economic, Politics, political, and soc ...

by his habit of promoting commoners to high positions, which subverted social norms. Yielding eventually to these demands, Toghrul attempted to lure his vassal into an ambush, but his plans were overheard by two herdsmen. Temüjin was able to gather some of his forces, but was soundly defeated at the Battle of Qalaqaljid Sands.

Retreating southeast to Baljuna, an unidentified lake or river, Temüjin waited for his scattered forces to regroup: Bo'orchu had lost his horse and was forced to flee on foot, while Temüjin's badly wounded son Ögedei had been transported and tended to by Borokhula, a leading warrior. Temüjin called in every possible ally and swore a famous oath of loyalty, later known as the Baljuna Covenant, to his faithful followers, which subsequently granted them great prestige. The oath-takers of Baljuna were a very heterogeneous group—men from nine different tribes who included Christians, Muslims, and Buddhists, united only by loyalty to Temüjin and to each other. This group became a model for the later empire, termed a "proto-government of a proto-nation" by historian John Man. The Baljuna Covenant was omitted from the ''Secret History''—as the group was predominantly non-Mongol, the author presumably wished to downplay the role of other tribes.

A involving Qasar allowed the Mongols to ambush the Kereit at the Jej'er Heights, but though the ensuing battle still lasted three days, it ended in a decisive victory for Temüjin. Toghrul and Senggum were both forced to flee, and while the latter escaped to Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ), or Greater Tibet, is a region in the western part of East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are other ethnic groups s ...

, Toghrul was killed by a Naiman who did not recognise him. Temüjin sealed his victory by absorbing the Kereit elite into his own tribe: he took the princess Ibaqa as a wife, and married her sister Sorghaghtani and niece Doquz to his youngest son Tolui. The ranks of the Naimans had swelled due to the arrival of Jamukha and others defeated by the Mongols, and they prepared for war. Temüjin was informed of these events by Alaqush, the sympathetic ruler of the Ongud tribe. In May 1204, at the Battle of Chakirmaut in the Altai Mountains

The Altai Mountains (), also spelled Altay Mountains, are a mountain range in Central Asia, Central and East Asia, where Russia, China, Mongolia, and Kazakhstan converge, and where the rivers Irtysh and Ob River, Ob have their headwaters. The ...

, the Naimans were decisively defeated: their leader Tayang Khan was killed, and his son Kuchlug was forced to flee west. The Merkits were decimated later that year, while Jamukha, who had abandoned the Naimans at Chakirmaut, was betrayed to Temüjin by companions who were executed for their lack of loyalty. According to the ''Secret History'', Jamukha convinced his childhood to execute him honourably; other accounts state that he was killed by dismemberment.

Early reign: reforms and Chinese campaigns (1206–1215)

of 1206 and reforms

Now sole ruler of the steppe, Temüjin held a large assembly called a at the source of the Onon River in 1206. Here, he formally adopted the title "Genghis Khan", the etymology and meaning of which have been much debated. Some commentators hold that the title had no meaning, simply representing Temüjin's eschewal of the traditional title, which had been accorded to Jamukha and was thus of lesser worth. Another theory suggests that the word "Genghis" bears connotations of strength, firmness, hardness, or righteousness. A third hypothesis proposes that the title is related to the Turkic ('ocean'), the title "Genghis Khan" would mean "master of the ocean", and as the ocean was believed to surround the earth, the title thus ultimately implied "Universal Ruler". Having attained control over one million people, Genghis Khan began a "social revolution", in May's words. As traditional tribal systems had primarily evolved to benefit small clans and families, they were unsuitable as the foundations for larger states and had been the downfall of previous steppe confederations. Genghis thus began a series of administrative reforms designed to suppress the power of tribal affiliations and to replace them with unconditional loyalty to the khan and the ruling family. As most of the traditional tribal leaders had been killed during his rise to power, Genghis was able to reconstruct the Mongol social hierarchy in his favour. The highest tier was occupied solely by his and his brothers' families, who became known as the ( 'Golden Family') or ( 'white bone'); underneath them came the ( 'black bone'; sometimes ), composed of the surviving pre-empire aristocracy and the most important of the new families. To break any concept of tribal loyalty, Mongol society was reorganised into a military decimal system. Every man between the age of fifteen and seventy was conscripted into a ( ), a unit of a thousand soldiers, which was further subdivided into units of hundreds (, ) and tens (, ). The units also encompassed each man's household, meaning that each military was supported by a of households in what May has termed "amilitary–industrial complex

The expression military–industrial complex (MIC) describes the relationship between a country's military and the Arms industry, defense industry that supplies it, seen together as a vested interest which influences public policy. A driving fac ...

". Each operated as both a political and social unit, while the warriors of defeated tribes were dispersed to different to make it difficult for them to rebel as a single body. This was intended to ensure the disappearance of old tribal identities, replacing them with loyalty to the "Great Mongol State", and to commanders who had gained their rank through merit and loyalty to the khan. This particular reform proved extremely effective—even after the division of the Mongol Empire, fragmentation never happened along tribal lines. Instead, the descendants of Genghis continued to reign unchallenged, in some cases until as late as the 1700s, and even powerful non-imperial dynasts such as Timur and Edigu were compelled to rule from behind a puppet ruler of his lineage.

Genghis's senior were appointed to the highest ranks and received the greatest honours. Bo'orchu and Muqali were each given ten thousand men to lead as commanders of the right and left wings of the army respectively. The other were each given commands of one of the ninety-five . In a display of Genghis' meritocratic ideals, many of these men were born to low social status: Ratchnevsky cited Jelme and Subutai, the sons of blacksmiths, in addition to a carpenter, a shepherd, and even the two herdsmen who had warned Temüjin of Toghrul's plans in 1203. As a special privilege, Genghis allowed certain loyal commanders to retain the tribal identities of their units. Alaqush of the Ongud was allowed to retain five thousand warriors of his tribe because his son had entered into an alliance pact with Genghis, marrying his daughter Alaqa.

A key tool which underpinned these reforms was the expansion of the ('bodyguard'). After Temüjin defeated Toghrul in 1203, he had appropriated this Kereit institution in a minor form, but at the 1206 its numbers were greatly expanded, from 1,150 to 10,000 men. The was not only the khan's bodyguard, but his household staff, a military academy, and the centre of governmental administration. All the warriors in this elite corps were brothers or sons of military commanders and were essentially hostages. The members of the nevertheless received special privileges and direct access to the khan, whom they served and who in return evaluated their capabilities and their potential to govern or command. Commanders such as Subutai, Chormaqan, and Baiju all started out in the , before being given command of their own force.

Consolidation of power (1206–1210)

From 1204 to 1209, Genghis Khan was predominantly focused on consolidating and maintaining his new nation. He faced a challenge from theshaman

Shamanism is a spiritual practice that involves a practitioner (shaman) interacting with the spirit world through altered states of consciousness, such as trance. The goal of this is usually to direct spirits or spiritual energies into ...

Kokechu, whose father Münglig had been allowed to marry Hö'elün after he defected to Temüjin. Kokechu, who had proclaimed Temüjin as Genghis Khan and taken the Tengrist

Tengrism (also known as Tengriism, Tengerism, or Tengrianism) is a belief-system originating in the Eurasian Steppe, Eurasian steppes, based on shamanism and animism. It generally involves the titular sky god Tengri. According to some scholars, ...

title "Teb Tenggeri" ( "Wholly Heavenly") on account of his sorcery, was very influential among the Mongol commoners and sought to divide the imperial family. Genghis's brother Qasar was the first of Kokechu's targets—always distrusted by his brother, Qasar was humiliated and almost imprisoned on false charges before Hö'elün intervened by publicly reprimanding Genghis. Nevertheless, Kokechu's power steadily increased, and he publicly shamed Temüge, Genghis's youngest brother, when he attempted to intervene. Börte saw that Kokechu was a threat to Genghis's power and warned her husband, who still superstitiously revered the shaman but now recognised the political threat he posed. Genghis allowed Temüge to arrange Kokechu's death, and then usurped the shaman's position as the Mongols' highest spiritual authority.

During these years, the Mongols imposed their control on surrounding areas. Genghis dispatched Jochi northwards in 1207 to subjugate the , a collection of tribes on the edge of the Siberian taiga. Having secured a marriage alliance with the Oirats

Oirats (; ) or Oirds ( ; ), formerly known as Eluts and Eleuths ( or ; zh, 厄魯特, ''Èlǔtè'') are the westernmost group of Mongols, whose ancestral home is in the Altai Mountains, Altai region of Siberia, Xinjiang and western Mongolia.

...

and defeated the Yenisei Kyrgyz

The Yenisei Kyrgyz () were an ancient Turkic people who dwelled along the upper Yenisei River in the southern portion of the Minusinsk Depression from the 3rd century BCE to the 13th century CE. The heart of their homeland was the forested T ...

, he took control of the region's trade in grain and furs, as well as its gold mines. Mongol armies also rode westwards, defeating the Naiman-Merkit alliance on the River Irtysh in late 1208. Their khan was killed and Kuchlug fled into Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

. Led by Barchuk, the Uyghurs

The Uyghurs,. alternatively spelled Uighurs, Uygurs or Uigurs, are a Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group originating from and culturally affiliated with the general region of Central Asia and East Asia. The Uyghurs are recognized as the ti ...

freed themselves from the suzerainty of the Qara Khitai and pledged themselves to Genghis in 1211 as the first sedentary society to submit to the Mongols.

The Mongols had started raiding the border settlements of the Tangut-led Western Xia kingdom in 1205, ostensibly in retaliation for allowing Senggum, Toghrul's son, refuge. More prosaic explanations include rejuvenating the depleted Mongol economy with an influx of fresh goods and

The Mongols had started raiding the border settlements of the Tangut-led Western Xia kingdom in 1205, ostensibly in retaliation for allowing Senggum, Toghrul's son, refuge. More prosaic explanations include rejuvenating the depleted Mongol economy with an influx of fresh goods and livestock

Livestock are the Domestication, domesticated animals that are raised in an Agriculture, agricultural setting to provide labour and produce diversified products for consumption such as meat, Egg as food, eggs, milk, fur, leather, and wool. The t ...

, or simply subjugating a semi-hostile state to protect the nascent Mongol nation. Most Xia troops were stationed along the southern and eastern borders of the kingdom to guard against attacks from the Song

A song is a musical composition performed by the human voice. The voice often carries the melody (a series of distinct and fixed pitches) using patterns of sound and silence. Songs have a structure, such as the common ABA form, and are usu ...

and Jin dynasties respectively, while its northern border relied only on the Gobi desert for protection. After a raid in 1207 sacked the Xia fortress of Wulahai, Genghis decided to personally lead a full-scale invasion in 1209.

Wulahai was captured again in May and the Mongols advanced on the capital Zhongxing (modern-day Yinchuan

Yinchuan is the capital of the Ningxia, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, China, and was the capital of the Tangut people, Tangut-led Western Xia, Western Xia dynasty. It has an area of and a total population of 2,859,074 according to the 2020 C ...

) but suffered a reverse against a Xia army. After a two-month stalemate, Genghis broke the deadlock with a feigned retreat; the Xia forces were deceived out of their defensive positions and overpowered. Although Zhongxing was now mostly undefended, the Mongols lacked any siege equipment better than crude battering rams and were unable to progress the siege. The Xia requested aid from the Jin, but Emperor Zhangzong rejected the plea. Genghis's attempt to redirect the Yellow River

The Yellow River, also known as Huanghe, is the second-longest river in China and the List of rivers by length, sixth-longest river system on Earth, with an estimated length of and a Drainage basin, watershed of . Beginning in the Bayan H ...

into the city with a dam initially worked, but the poorly-constructed earthworks broke—possibly breached by the Xia—in January 1210 and the Mongol camp was flooded, forcing them to retreat. A peace treaty was soon formalised: the Xia emperor Xiangzong submitted and handed over tribute, including his daughter Chaka, in exchange for the Mongol withdrawal.

Campaign against the Jin (1211–1215)

Wanyan Yongji usurped the Jin throne in 1209. He had previously served on the steppe frontier and Genghis greatly disliked him. When asked to submit and pay the annual tribute to Yongji in 1210, Genghis instead mocked the emperor, spat, and rode away from the Jin envoy—a challenge that meant war. Despite the possibility of being outnumbered eight-to-one by 600,000 Jin soldiers, Genghis had prepared to invade the Jin since learning in 1206 that the state was wracked by internal instabilities. Genghis had two aims: to take vengeance for past wrongs committed by the Jin, foremost among which was the death of Ambaghai Khan in the mid-12th century, and to win the vast amounts of plunder his troops and vassals expected. After calling for a in March 1211, Genghis launched his invasion of Jin China in May, reaching the outer ring of Jin defences the following month. Theseborder

Borders are generally defined as geography, geographical boundaries, imposed either by features such as oceans and terrain, or by polity, political entities such as governments, sovereign states, federated states, and other administrative divisio ...

fortifications were guarded by Alaqush's Ongud, who allowed the Mongols to pass without difficulty. The three-pronged chevauchée aimed both to plunder and burn a vast area of Jin territory to deprive them of supplies and popular legitimacy, and to secure the mountain pass

A mountain pass is a navigable route through a mountain range or over a ridge. Since mountain ranges can present formidable barriers to travel, passes have played a key role in trade, war, and both Human migration, human and animal migration t ...

es which allowed access to the North China Plain

The North China Plain () is a large-scale downfaulted rift basin formed in the late Paleogene and Neogene and then modified by the deposits of the Yellow River. It is the largest alluvial plain of China. The plain is bordered to the north by th ...

. The Jin lost numerous towns and were hindered by a series of defections, the most prominent of which led directly to Muqali's victory at the Battle of Huan'erzhui in autumn 1211. The campaign was halted in 1212 when Genghis was wounded by an arrow during the unsuccessful siege of Xijing (modern Datong). Following this failure, Genghis set up a corps of siege engineers, which recruited 500 Jin experts over the next two years.

The defences of Juyong Pass had been strongly reinforced by the time the conflict resumed in 1213, but a Mongol detachment led by Jebe managed to infiltrate the pass and surprise the elite Jin defenders, opening the road to the Jin capital Zhongdu (modern-day Beijing

Beijing, Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Peking, is the capital city of China. With more than 22 million residents, it is the world's List of national capitals by population, most populous national capital city as well as ...

). The Jin administration began to disintegrate: after the Khitans, a tribe subject to the Jin, entered open rebellion, Hushahu, the commander of the forces at Xijing, abandoned his post and staged a coup in Zhongdu, killing Yongji and installing his own puppet ruler, Xuanzong. This governmental breakdown was fortunate for Genghis's forces; emboldened by their victories, they had seriously overreached and lost the initiative. Unable to do more than camp before Zhongdu's fortification

A fortification (also called a fort, fortress, fastness, or stronghold) is a military construction designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Lati ...

s while his army suffered from an epidemic and famine—they resorted to cannibalism according to Carpini, who may have been exaggerating—Genghis opened peace negotiations despite his commanders' militance. He secured tribute, including 3,000 horses, 500 slaves, a Jin princess, and massive amounts of gold and silk, before lifting the siege and setting off homewards in May 1214.

As the northern Jin lands had been ravaged by plague and war, Xuanzong moved the capital and imperial court southwards to Kaifeng

Kaifeng ( zh, s=开封, p=Kāifēng) is a prefecture-level city in east-Zhongyuan, central Henan province, China. It is one of the Historical capitals of China, Eight Ancient Capitals of China, having been the capital eight times in history, and ...

. Interpreting this as an attempt to regroup in the south and then restart the war, Genghis concluded the terms of the peace treaty had been broken. He immediately prepared to return and capture Zhongdu. According to Christopher Atwood, it was only at this juncture that Genghis decided to fully conquer northern China. Muqali captured numerous towns in Liaodong during winter 1214–15, and although the inhabitants of Zhongdu surrendered to Genghis on 31 May 1215, the city was sacked. When Genghis returned to Mongolia in early 1216, Muqali was left in command in China. He waged a brutal but effective campaign against the unstable Jin regime until his death in 1223.

Later reign: western expansion and return to China (1216–1227)

Defeating rebellions and Qara Khitai (1216–1218)

In 1207, Genghis had appointed a man named Qorchi as governor of the subdued Hoi-yin Irgen tribes in Siberia. Appointed not for his talents but for prior services rendered, Qorchi's tendency to abduct women as concubines for hisharem

A harem is a domestic space that is reserved for the women of the house in a Muslim family. A harem may house a man's wife or wives, their pre-pubescent male children, unmarried daughters, female domestic Domestic worker, servants, and other un ...

caused the tribes to rebel and take him prisoner in early 1216. The following year, they ambushed and killed Boroqul, one of Genghis's highest-ranking . The khan was livid at the loss of his close friend and prepared to lead a retaliatory campaign; eventually dissuaded from this course, he dispatched his eldest son Jochi and a Dörbet commander. They managed to surprise and defeat the rebels, securing control over this economically important region.

Kuchlug, the Naiman prince who had been defeated in 1204, had usurped the throne of the Central Asian Qara Khitai dynasty between 1211 and 1213. He was a greedy and arbitrary ruler who probably earned the enmity of the native Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

ic populace whom he attempted to forcibly convert to Buddhism

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

. Genghis reckoned that Kuchlug could be a threat to his empire, and Jebe was sent with an army of 20,000 cavalry to the city of Kashgar; he undermined Kuchlug's rule by emphasising the Mongol policies of religious tolerance and gained the loyalty of the local elite. Kuchlug was forced to flee southwards to the Pamir Mountains

The Pamir Mountains are a Mountain range, range of mountains between Central Asia and South Asia. They are located at a junction with other notable mountains, namely the Tian Shan, Karakoram, Kunlun Mountains, Kunlun, Hindu Kush and the Himalaya ...

, but was captured by local hunters. Jebe had him beheaded and paraded his corpse through Qara Khitai, proclaiming the end of religious persecution in the region.

Invasion of the Khwarazmian Empire (1219–1221)

Silk Road

The Silk Road was a network of Asian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over , it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and religious interactions between the ...

, and his territory bordered that of the Khwarazmian Empire

The Khwarazmian Empire (), or simply Khwarazm, was a culturally Persianate society, Persianate, Sunni Muslim empire of Turkic peoples, Turkic ''mamluk'' origin. Khwarazmians ruled large parts of present-day Central Asia, Afghanistan, and Iran ...

, which ruled over much of Central Asia, Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

and Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. It is bordered by Pakistan to the Durand Line, east and south, Iran to the Afghanistan–Iran borde ...

. Merchants from both sides were eager to restart trading, which had halted during Kuchlug's rule; the Khwarazmian ruler Muhammad II dispatched an envoy shortly after the Mongol capture of Zhongdu, while Genghis instructed his merchants to obtain the high-quality textiles and steel of Central and Western Asia. Many members of the invested in one particular caravan of 450 merchants which set off to Khwarazmia in 1218 with a large quantity of wares. Inalchuq, the governor of the Khwarazmian border town of Otrar, decided to massacre the merchants on grounds of espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering, as a subfield of the intelligence field, is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information ( intelligence). A person who commits espionage on a mission-specific contract is called an ...

and seize the goods; Muhammad had grown suspicious of Genghis's intentions and either supported Inalchuq or turned a blind eye. A Mongol ambassador was sent with two companions to avert war, but Muhammad killed him and humiliated his companions. The killing of an envoy infuriated Genghis, who resolved to leave Muqali with a small force in North China and invade Khwarazmia with most of his army.

Muhammad's empire was large but disunited: he ruled alongside his mother Terken Khatun in what the historian Peter Golden terms "an uneasy diarchy", while the Khwarazmian nobility and populace were discontented with his warring and the centralisation of government. For these reasons and others he declined to meet the Mongols in the field, instead garrisoning his unruly troops in his major cities. This allowed the lightly armoured, highly mobile Mongol armies uncontested superiority outside city walls. Otrar was besieged in autumn 1219—the siege dragged on for five months, but in February 1220 the city fell and Inalchuq was executed. Genghis had meanwhile divided his forces. Leaving his sons Chagatai and Ögedei to besiege the city, he had sent Jochi northwards down the Syr Darya

The Syr Darya ( ),; ; ; ; ; /. historically known as the Jaxartes ( , ), is a river in Central Asia. The name, which is Persian language, Persian, literally means ''Syr Sea'' or ''Syr River''. It originates in the Tian Shan, Tian Shan Mountain ...

river and another force southwards into central Transoxiana

Transoxiana or Transoxania (, now called the Amu Darya) is the Latin name for the region and civilization located in lower Central Asia roughly corresponding to eastern Uzbekistan, western Tajikistan, parts of southern Kazakhstan, parts of Tu ...

, while he and Tolui took the main Mongol army across the Kyzylkum Desert, surprising the garrison of Bukhara

Bukhara ( ) is the List of cities in Uzbekistan, seventh-largest city in Uzbekistan by population, with 280,187 residents . It is the capital of Bukhara Region.

People have inhabited the region around Bukhara for at least five millennia, and t ...

in a pincer movement

The pincer movement, or double envelopment, is a maneuver warfare, military maneuver in which forces simultaneously attack both flanking maneuver, flanks (sides) of an enemy Military organization, formation. This classic maneuver has been im ...

.

Bukhara's citadel was captured in February 1220 and Genghis moved against Muhammad's residence Samarkand

Samarkand ( ; Uzbek language, Uzbek and Tajik language, Tajik: Самарқанд / Samarqand, ) is a city in southeastern Uzbekistan and among the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest continuously inhabited cities in Central As ...

, which fell the following month. Bewildered by the speed of the Mongol conquests, Muhammad fled from Balkh, closely followed by Jebe and Subutai; the two generals pursued the Khwarazmshah until he died from dysentry on a Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, described as the List of lakes by area, world's largest lake and usually referred to as a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia: east of the Caucasus, ...

island in winter 1220–21, having nominated his eldest son Jalal al-Din as his successor. Jebe and Subutai then set out on a -expedition around the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, described as the List of lakes by area, world's largest lake and usually referred to as a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia: east of the Caucasus, ...

. Later called the ''Great Raid'', this lasted four years and saw the Mongols come into contact with Europe for the first time. Meanwhile, the Khwarazmian capital of Gurganj

Konye-Urgench (, ; , ), also known as Old Urgench or Urganj, was a city in north Turkmenistan, just south from its border with Uzbekistan. It is the site of the ancient town of Gurgānj, which contains the ruins of the capital of Khwarazm. Its in ...

was being besieged by Genghis's three eldest sons. The long siege ended in spring 1221 amid brutal urban conflict. Jalal al-Din moved southwards to Afghanistan, gathering forces on the way and defeating a Mongol unit under the command of Shigi Qutuqu, Genghis's adopted son, in the Battle of Parwan. Jalal was weakened by arguments among his commanders, and after losing decisively at the Battle of the Indus in November 1221, he was compelled to escape across the Indus river

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayas, Himalayan river of South Asia, South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in the Western Tibet region of China, flows northw ...

into India.

Genghis's youngest son Tolui was concurrently conducting a brutal campaign in the regions of Khorasan. Every city that resisted was destroyed—Nishapur

Nishapur or Neyshabur (, also ) is a city in the Central District (Nishapur County), Central District of Nishapur County, Razavi Khorasan province, Razavi Khorasan province, Iran, serving as capital of both the county and the district.

Ni ...

, Merv

Merv (, ', ; ), also known as the Merve Oasis, was a major Iranian peoples, Iranian city in Central Asia, on the historical Silk Road, near today's Mary, Turkmenistan. Human settlements on the site of Merv existed from the 3rd millennium& ...

and Herat

Herāt (; Dari/Pashto: هرات) is an oasis city and the third-largest city in Afghanistan. In 2020, it had an estimated population of 574,276, and serves as the capital of Herat Province, situated south of the Paropamisus Mountains (''Se ...

, three of the largest and wealthiest cities in the world, were all annihilated. This campaign established Genghis's lasting image as a ruthless, inhumane conqueror. Contemporary Persian historians placed the death toll from the three sieges alone at over 5.7 million—a number regarded as grossly exaggerated by modern scholars. Nevertheless, even a total death toll of 1.25 million for the entire campaign, as estimated by John Man, would have been a demographic catastrophe.

Return to China and final campaign (1222–1227)

Genghis abruptly halted his Central Asian campaigns in 1221. Initially aiming to return viaIndia

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

, Genghis realised that the heat and humidity of the South Asian climate impeded his army's skills, while the omens were additionally unfavourable. Although the Mongols spent much of 1222 repeatedly overcoming rebellions in Khorasan, they withdrew completely from the region to avoid overextending themselves, setting their new frontier on the Amu Darya

The Amu Darya ( ),() also shortened to Amu and historically known as the Oxus ( ), is a major river in Central Asia, which flows through Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Afghanistan. Rising in the Pamir Mountains, north of the Hindu Ku ...

river. During his lengthy return journey, Genghis prepared a new administrative division which would govern the conquered territories, appointing (commissioners, "those who press the seal") and (local officials) to manage the region back to normalcy. He also summoned and spoke with the Taoist

Taoism or Daoism (, ) is a diverse philosophical and religious tradition indigenous to China, emphasizing harmony with the Tao ( zh, p=dào, w=tao4). With a range of meaning in Chinese philosophy, translations of Tao include 'way', 'road', ...

patriarch Changchun

Changchun is the capital and largest city of Jilin, Jilin Province, China, on the Songliao Plain. Changchun is administered as a , comprising seven districts, one county and three county-level cities. At the 2020 census of China, Changchun ha ...

in the Hindu Kush

The Hindu Kush is an mountain range in Central Asia, Central and South Asia to the west of the Himalayas. It stretches from central and eastern Afghanistan into northwestern Pakistan and far southeastern Tajikistan. The range forms the wester ...

. The khan listened attentively to Changchun's teachings and granted his followers numerous privileges, including tax exemption

Tax exemption is the reduction or removal of a liability to make a compulsory payment that would otherwise be imposed by a ruling power upon persons, property, income, or transactions. Tax-exempt status may provide complete relief from taxes, redu ...

s and authority over all monks throughout the empire—a grant which the Taoists later used to try to gain superiority over Buddhism.

The usual reason given for the halting of the campaign is that the Western Xia, having declined to provide auxiliaries for the 1219 invasion, had additionally disobeyed Muqali in his campaign against the remaining Jin in Shaanxi

Shaanxi is a Provinces of China, province in north Northwestern China. It borders the province-level divisions of Inner Mongolia to the north; Shanxi and Henan to the east; Hubei, Chongqing, and Sichuan to the south; and Gansu and Ningxia to t ...

. May has disputed this, arguing that the Xia fought in concert with Muqali until his death in 1223, when, frustrated by Mongol control and sensing an opportunity with Genghis campaigning in Central Asia, they ceased fighting. In either case, Genghis initially attempted to resolve the situation diplomatically, but when the Xia elite failed to come to an agreement on the hostages they were to send to the Mongols, he lost patience.

Returning to Mongolia in early 1225, Genghis spent the year in preparation for a campaign against them. This began in the first months of 1226 with the capture of Khara-Khoto on the Xia's western border. The invasion proceeded apace. Genghis ordered that the cities of the Gansu Corridor be sacked one by one, granting clemency only to a few. Having crossed the Yellow River

The Yellow River, also known as Huanghe, is the second-longest river in China and the List of rivers by length, sixth-longest river system on Earth, with an estimated length of and a Drainage basin, watershed of . Beginning in the Bayan H ...

in autumn, the Mongols besieged present-day Lingwu, located just south of the Xia capital Zhongxing, in November. On 4 December, Genghis decisively defeated a Xia relief army; the khan left the siege of the capital to his generals and moved southwards with Subutai to plunder and secure Jin territories.

Death and aftermath

Genghis fell from his horse while hunting in the winter of 1226–27 and became increasingly ill during the following months. This slowed the siege of Zhongxing's progress, as his sons and commanders urged him to end the campaign and return to Mongolia to recover, arguing that the Xia would still be there another year. Incensed by insults from Xia's leading commander, Genghis insisted that the siege be continued. He died on either 18 or 25 August 1227, but his death was kept a closely guarded secret and Zhongxing, unaware, fell the following month. The city was put to the sword and its population was treated with extreme savagery—the Xia civilization was essentially extinguished in what Man described as a "very successfulethnocide

Ethnocide is the extermination or destruction of ethnic identities. Bartolomé Clavero differentiates ethnocide from genocide by stating that "Genocide kills people while ethnocide kills social cultures through the killing of individual souls". ...

". The exact nature of the khan's death has been the subject of intense speculation. Rashid al-Din and the ''History of Yuan'' mention he suffered from an illness—possibly malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

, typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposu ...

, or bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of Plague (disease), plague caused by the Bacteria, bacterium ''Yersinia pestis''. One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and ...

. Marco Polo

Marco Polo (; ; ; 8 January 1324) was a Republic of Venice, Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in ''The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known a ...

claimed that he was shot by an arrow during a siege, while Carpini reported that Genghis was struck by lightning. Legends sprang up around the event—the most famous recounts how the beautiful Gurbelchin, formerly the Xia emperor's wife, injured Genghis's genitals with a dagger during sex.

After his death, Genghis was transported back to Mongolia and buried on or near the sacred Burkhan Khaldun peak in the Khentii Mountains, on a site he had chosen years before. Specific details of the funeral procession and burial were not made public knowledge; the mountain, declared ( "Great Taboo"; i.e. prohibited zone), was out of bounds to all but its Uriankhai guard. When Ögedei acceded to the throne in 1229, the grave was honoured with three days of offerings and the sacrifice of thirty maidens. Ratchnevsky theorised that the Mongols, who had no knowledge of embalming techniques, may have buried the khan in the Ordos to avoid his body decomposing in the summer heat while en route to Mongolia; Atwood rejects this hypothesis.

Succession

The tribes of the Mongol steppe had no fixed succession system, but often defaulted to some form of ultimogeniture—succession of the youngest son—because he would have had the least time to gain a following for himself and needed the help of his father's inheritance. However, this type of inheritance applied only to property, not to titles. The ''Secret History'' records that Genghis chose his successor while preparing for the Khwarazmian campaigns in 1219; Rashid al-Din, on the other hand, states that the decision came before Genghis's final campaign against the Xia. Regardless of the date, there were five possible candidates: Genghis's four sons and his youngest brother Temüge, who had the weakest claim and who was never seriously considered. Even though there was a strong possibility Jochi was illegitimate, Genghis was not particularly concerned by this; nevertheless, he and Jochi became increasingly estranged over time, due to Jochi's preoccupation with his own appanage. After the siege of Gurganj, where he only reluctantly participated in besieging the wealthy city that would become part of his territory, he failed to give Genghis the normal share of the booty, which exacerbated the tensions. Genghis was angered by Jochi's refusal to return to him in 1223, and was considering sending Ögedei and Chagatai to bring him to heel when news came that Jochi had died from an illness. Chagatai's attitude towards Jochi's possible succession—he had termed his elder brother "a Merkit bastard" and had brawled with him in front of their father—led Genghis to view him as uncompromising, arrogant, and narrow-minded, despite his great knowledge of Mongol legal customs. His elimination left Ögedei and Tolui as the two primary candidates. Tolui was unquestionably superior in military terms—his campaign in Khorasan had broken the Khwarazmian Empire, while his elder brother was far less able as a commander. Ögedei was also known to drink excessively even by Mongol standards—it eventually caused his death in 1241. However, he possessed talents all his brothers lacked—he was generous and generally well-liked. Aware of his own lack of military skill, he was able to trust his capable subordinates, and unlike his elder brothers, compromise on issues; he was also more likely to preserve Mongol traditions than Tolui, whose wife Sorghaghtani, herself a Nestorian Christian, was a patron of many religions including Islam. Ögedei was thus recognised as the heir to the Mongol throne. Serving as