Gnosticism (from grc, γνωστικός, gnōstikós, , 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems which coalesced in the late 1st century AD among

Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

and

early Christian

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewish ...

sects. These various groups emphasized personal spiritual knowledge (''

gnosis

Gnosis is the common Greek noun for knowledge ( γνῶσις, ''gnōsis'', f.). The term was used among various Hellenistic religions and philosophies in the Greco-Roman world. It is best known for its implication within Gnosticism, where it s ...

'') above the orthodox teachings, traditions, and authority of religious institutions. Gnostic

cosmogony

Cosmogony is any model concerning the origin of the cosmos or the universe.

Overview

Scientific theories

In astronomy, cosmogony refers to the study of the origin of particular astrophysical objects or systems, and is most commonly used i ...

generally presents a distinction between a supreme, hidden

God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

and a malevolent

lesser divinity (sometimes associated with the

Yahweh

Yahweh *''Yahwe'', was the national god of ancient Israel and Judah. The origins of his worship reach at least to the early Iron Age, and likely to the Late Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately fr ...

of the

Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

) who is responsible for creating the

material universe.

Consequently, Gnostics considered material existence flawed or evil, and held the principal element of

salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its c ...

to be direct knowledge of the hidden divinity, attained via mystical or

esoteric

Western esotericism, also known as esotericism, esoterism, and sometimes the Western mystery tradition, is a term scholars use to categorise a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements that developed within Western society. These ideas a ...

insight. Many Gnostic texts deal not in concepts of

sin and

repentance, but with

illusion

An illusion is a distortion of the senses, which can reveal how the mind normally organizes and interprets sensory stimulation. Although illusions distort the human perception of reality, they are generally shared by most people.

Illusions may ...

and

enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

.

Gnostic writings flourished among certain Christian groups in the

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on th ...

world around the second century, when the

Fathers of the early Church denounced them as

heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

. Efforts to destroy these texts proved largely successful, resulting in the survival of very little writing by Gnostic theologians.

Nonetheless, early Gnostic teachers such as

Valentinus

Valentinus is a Roman masculine given name derived from the Latin word "valens" meaning "healthy, strong". It may refer to:

People Churchmen

*Pope Valentine (died 827)

*Saint Valentine, one or more martyred Christian saints

*Valentinus (Gnostic) ...

saw their beliefs as aligned with Christianity. In the Gnostic Christian tradition,

Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religi ...

is seen as a divine being which has taken human form in order to lead humanity back to recognition of its own divine nature. However, Gnosticism is not a single standardized system, and the emphasis on direct experience allows for a wide variety of teachings, including distinct currents such as

Valentinianism

Valentinianism was one of the major Gnostic Christian movements. Founded by Valentinus in the 2nd century AD, its influence spread widely, not just within Rome but also from Northwest Africa to Egypt through to Asia Minor and Syria in the East. L ...

and

Sethianism

The Sethians were one of the main currents of Gnosticism during the 2nd and 3rd century CE, along with Valentinianism and Basilideanism. According to John D. Turner, it originated in the 2nd century CE as a fusion of two distinct Hellenistic ...

. In the

Persian Empire, Gnostic ideas spread as far as China via the related movement

Manichaeism

Manichaeism (;

in New Persian ; ) is a former major religionR. van den Broek, Wouter J. Hanegraaff ''Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times''SUNY Press, 1998 p. 37 founded in the 3rd century AD by the Parthian prophet Mani ( ...

, while

Mandaeism

Mandaeism ( Classical Mandaic: ࡌࡀࡍࡃࡀࡉࡉࡀ ; Arabic: المندائيّة ), sometimes also known as Nasoraeanism or Sabianism, is a Gnostic, monotheistic and ethnic religion. Its adherents, the Mandaeans, revere Adam, Ab ...

, which is one of the only two surviving Gnostic religions from antiquity, is found in

Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

,

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkm ...

and diaspora communities.

Jorunn Buckley posits that the early

Mandaeans

Mandaeans ( ar, المندائيون ), also known as Mandaean Sabians ( ) or simply as Sabians ( ), are an ethnoreligious group who are followers of Mandaeism. They believe that John the Baptist was the final and most important prophet. They ...

may have been among the first to formulate what would go on to become Gnosticism within the early Jesus movement.

[

For centuries, most scholarly knowledge about Gnosticism was limited to the anti-heretical writings of orthodox Christian figures such as ]Irenaeus of Lyons

Irenaeus (; grc-gre, Εἰρηναῖος ''Eirēnaios''; c. 130 – c. 202 AD) was a Greek bishop noted for his role in guiding and expanding Christian communities in the southern regions of present-day France and, more widely, for the deve ...

and Hippolytus of Rome

Hippolytus of Rome (, ; c. 170 – c. 235 AD) was one of the most important second-third century Christian theologians, whose provenance, identity and corpus remain elusive to scholars and historians. Suggested communities include Rome, Palestin ...

. There was a renewed interest in Gnosticism after the 1945 discovery of Egypt's Nag Hammadi library

The Nag Hammadi library (also known as the " Chenoboskion Manuscripts" and the "Gnostic Gospels") is a collection of early Christian and Gnostic texts discovered near the Upper Egyptian town of Nag Hammadi in 1945.

Thirteen leather-bound papyr ...

, a collection of rare early Christian and Gnostic texts, including the Gospel of Thomas

The Gospel of Thomas (also known as the Coptic Gospel of Thomas) is an extra-canonical sayings gospel. It was discovered near Nag Hammadi, Egypt, in December 1945 among a group of books known as the Nag Hammadi library. Scholars speculat ...

and the Apocryphon of John. Elaine Pagels

Elaine Pagels, née Hiesey (born February 13, 1943), is an American historian of religion. She is the Harrington Spear Paine Professor of Religion at Princeton University. Pagels has conducted extensive research into early Christianity and Gnost ...

has noted the influence of sources from Hellenistic Judaism

Hellenistic Judaism was a form of Judaism in classical antiquity that combined Jewish religious tradition with elements of Greek culture. Until the early Muslim conquests of the eastern Mediterranean, the main centers of Hellenistic Judaism wer ...

, Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism is an Iranian religion and one of the world's oldest organized faiths, based on the teachings of the Iranian-speaking prophet Zoroaster. It has a dualistic cosmology of good and evil within the framework of a monotheistic ont ...

, and Platonism

Platonism is the philosophy of Plato and philosophical systems closely derived from it, though contemporary platonists do not necessarily accept all of the doctrines of Plato. Platonism had a profound effect on Western thought. Platonism at ...

on the Nag Hammadi texts.early Christianity

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Je ...

, an interreligious phenomenon, or an independent religion. Going further than this, other contemporary scholars such as Michael Allen Williams and David G. Robertsonheresiologists

In theology or the history of religion, heresiology is the study of heresy, and heresiographies are writings about the topic. Heresiographical works were common in both medieval Christianity and Islam.

Heresiology developed as a part of the emergi ...

for a disparate group of contemporaneous Christian groups.

Etymology

''Gnosis'' refers to knowledge based on personal experience or perception. In a religious context, ''gnosis'' is mystical

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight in u ...

or esoteric knowledge

Knowledge can be defined as awareness of facts or as practical skills, and may also refer to familiarity with objects or situations. Knowledge of facts, also called propositional knowledge, is often defined as true belief that is disti ...

based on direct participation with the divine. In most Gnostic systems, the sufficient cause of salvation is this "knowledge of" ("acquaintance with") the divine. It is an inward "knowing", comparable to that encouraged by Plotinus

Plotinus (; grc-gre, Πλωτῖνος, ''Plōtînos''; – 270 CE) was a philosopher in the Hellenistic philosophy, Hellenistic tradition, born and raised in Roman Egypt. Plotinus is regarded by modern scholarship as the founder of Neop ...

(neoplatonism

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonism, Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and Hellenistic religion, religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of ...

), and differs from proto-orthodox Christian views. Gnostics are "those who are oriented toward knowledge and understanding – or perception and learning – as a particular modality for living".Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institutio ...

in the comparison of "practical" (''praktikos'') and "intellectual" (''gnostikos''). Plato's use of "learned" is fairly typical of Classical texts.

By the Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

, it began also to be associated with Greco-Roman mysteries

Mystery religions, mystery cults, sacred mysteries or simply mysteries, were religious schools of the Greco-Roman world for which participation was reserved to initiates ''(mystai)''. The main characterization of this religion is the secrecy as ...

, becoming synonymous with the Greek term ''musterion''. The adjective is not used in the New Testament, but Clement of Alexandria

Titus Flavius Clemens, also known as Clement of Alexandria ( grc , Κλήμης ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς; – ), was a Christian theologian and philosopher who taught at the Catechetical School of Alexandria. Among his pupils were Origen an ...

speaks of the "learned" (''gnostikos'') Christian in complimentary terms. The use of ''gnostikos'' in relation to heresy originates with interpreters of Irenaeus

Irenaeus (; grc-gre, Εἰρηναῖος ''Eirēnaios''; c. 130 – c. 202 AD) was a Greek bishop noted for his role in guiding and expanding Christian communities in the southern regions of present-day France and, more widely, for the dev ...

. Some scholars consider that Irenaeus sometimes uses ''gnostikos'' to simply mean "intellectual", whereas his mention of "the intellectual sect" is a specific designation. The term "Gnosticism" does not appear in ancient sources, and was first coined in the 17th century by Henry More

Henry More (; 12 October 1614 – 1 September 1687) was an English philosopher of the Cambridge Platonist school.

Biography

Henry was born in Grantham, Lincolnshire on 12 October 1614. He was the seventh son of Alexander More, mayor of Gran ...

in a commentary on the seven letters of the Book of Revelation

The Book of Revelation is the final book of the New Testament (and consequently the final book of the Christian Bible). Its title is derived from the first word of the Koine Greek text: , meaning "unveiling" or "revelation". The Book o ...

, where More used the term "Gnosticisme" to describe the heresy in Thyatira

Thyateira (also Thyatira) ( grc, Θυάτειρα) was the name of an ancient Greek city in Asia Minor, now the modern Turkish city of Akhisar ("white castle"). The name is probably Lydian. It lies in the far west of Turkey, south of Istanbu ...

. The term ''Gnosticism'' was derived from the use of the Greek adjective ''gnostikos'' (Greek γνωστικός, "learned", "intellectual") by St. Irenaeus (c. 185 AD) to describe the school of Valentinus

Valentinus is a Roman masculine given name derived from the Latin word "valens" meaning "healthy, strong". It may refer to:

People Churchmen

*Pope Valentine (died 827)

*Saint Valentine, one or more martyred Christian saints

*Valentinus (Gnostic) ...

as ''he legomene gnostike haeresis'' "the heresy called Learned (gnostic)."

Origins

The origins of Gnosticism are obscure and still disputed. The proto-orthodox Christian groups called Gnostics a heresy of Christianity, but according to the modern scholars the theology's origin is closely related to Jewish sectarian milieus and early Christian sects. Scholars debate Gnosticism's origins as having roots in Neoplatonism

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonism, Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and Hellenistic religion, religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of ...

and Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

, due to similarities in beliefs, but ultimately, its origins are currently unknown. As Christianity developed and became more popular, so did Gnosticism, with both proto-orthodox Christian and Gnostic Christian groups often existing in the same places. The Gnostic belief was widespread within Christianity until the proto-orthodox Christian communities expelled the group in the second and third centuries (AD). Gnosticism became the first group to be declared heretical

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

.

Some scholars prefer to speak of "gnosis" when referring to first-century ideas that later developed into Gnosticism, and to reserve the term "Gnosticism" for the synthesis of these ideas into a coherent movement in the second century. According to James M. Robinson

James McConkey Robinson (June 30, 1924 – March 22, 2016) was an American scholar who retired as Professor Emeritus of Religion at Claremont Graduate University, Claremont, California, specializing in New Testament Studies and Nag Hammadi ...

, no gnostic texts clearly pre-date Christianity, and "pre-Christian Gnosticism as such is hardly attested in a way to settle the debate once and for all."

Jewish Christian origins

Contemporary scholarship largely agrees that Gnosticism has Jewish Christian

Jewish Christians ( he, יהודים נוצרים, yehudim notzrim) were the followers of a Jewish religious sect that emerged in Judea during the late Second Temple period (first century AD). The Nazarene Jews integrated the belief of Jesus a ...

origins, originating in the late first century AD in nonrabbinical Jewish sects and early Christian sects. Ethel S. Drower adds "heterodox Judaism in Galilee

Galilee (; he, הַגָּלִיל, hagGālīl; ar, الجليل, al-jalīl) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Galilee traditionally refers to the mountainous part, divided into Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and Lower Gali ...

and Samaria

Samaria (; he, שֹׁמְרוֹן, translit=Šōmrōn, ar, السامرة, translit=as-Sāmirah) is the historic and biblical name used for the central region of Palestine, bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The first ...

appears to have taken shape in the form we now call Gnostic, and it may well have existed some time before the Christian era."[

Many heads of gnostic schools were identified as Jewish Christians by Church Fathers, and Hebrew words and names of God were applied in some gnostic systems.][Jewish Encyclopedia]

Gnosticism

/ref> The cosmogonic speculations among Christian Gnostics had partial origins in Maaseh Bereshit and '' Maaseh Merkabah''. This thesis is most notably put forward by Gershom Scholem (1897–1982) and Gilles Quispel (1916–2006). Scholem detected Jewish ''gnosis'' in the imagery of the merkavah, which can also be found in certain Gnostic documents. Quispel sees Gnosticism as an independent Jewish development, tracing its origins to Alexandrian Jews, to which group Valentinus was also connected.

Many of the Nag Hammadi texts make reference to Judaism, in some cases with a violent rejection of the Jewish God. Gershom Scholem once described Gnosticism as "the Greatest case of metaphysical anti-Semitism". Professor Steven Bayme Steven Bayme is an essayist and author. In 1997 he was National Director of Jewish Communal Affairs at the American Jewish Committee, and holds the rank of Adjunct Professor at the Wurzweiler School of Social Work, Yeshiva University. Bayme is a ...

said gnosticism would be better characterized as anti-Judaism

Anti-Judaism is the "total or partial opposition to Judaism as a religion—and the total or partial opposition to Jews as adherents of it—by persons who accept a competing system of beliefs and practices and consider certain genuine Judai ...

. Recent research into the origins of Gnosticism shows a strong Jewish influence, particularly from Hekhalot literature.[Idel, Moshe. ''Kabbalah: New Perspectives'', ]Yale University Press

Yale University Press is the university press of Yale University. It was founded in 1908 by George Parmly Day, and became an official department of Yale University in 1961, but it remains financially and operationally autonomous.

, Yale Univer ...

, 1990

p. 31

Within early Christianity, the teachings of Paul and John may have been a starting point for Gnostic ideas, with a growing emphasis on the opposition between flesh and spirit, the value of charisma, and the disqualification of the Jewish law. The mortal body belonged to the world of inferior, worldly powers (the ''archons

''Archon'' ( gr, ἄρχων, árchōn, plural: ἄρχοντες, ''árchontes'') is a Greek word that means "ruler", frequently used as the title of a specific public office. It is the masculine present participle of the verb stem αρχ-, mean ...

''), and only the spirit or soul could be saved. The term ''gnostikos'' may have acquired a deeper significance here.

Alexandria was of central importance for the birth of Gnosticism. The Christian ''ecclesia'' (i. e. congregation, church) was of Jewish–Christian origin, but also attracted Greek members, and various strands of thought were available, such as "Judaic apocalypticism

Apocalypticism is the religious belief that the end of the world is imminent, even within one's own lifetime. This belief is usually accompanied by the idea that civilization will soon come to a tumultuous end due to some sort of catastrophic ...

, speculation on divine wisdom, Greek philosophy, and Hellenistic mystery religions

Mystery religions, mystery cults, sacred mysteries or simply mysteries, were religious schools of the Greco-Roman world for which participation was reserved to initiates ''(mystai)''. The main characterization of this religion is the secrecy as ...

."

Regarding the angel Christology of some early Christians, Darrell Hannah notes:

The pseudepigraphical Christian text '' Ascension of Isaiah'' identifies Jesus with angel Christology:

The Shepherd of Hermas

''The Shepherd of Hermas'' ( el, Ποιμὴν τοῦ Ἑρμᾶ, ''Poimēn tou Herma''; la, Pastor Hermae), sometimes just called ''The Shepherd'', is a Christian literary work of the late first half of the second century, considered a valuab ...

is a Christian literary work considered as canonical scripture by some of the early Church fathers such as Irenaeus

Irenaeus (; grc-gre, Εἰρηναῖος ''Eirēnaios''; c. 130 – c. 202 AD) was a Greek bishop noted for his role in guiding and expanding Christian communities in the southern regions of present-day France and, more widely, for the dev ...

. Jesus is identified with angel Christology in parable 5, when the author mentions a Son of God, as a virtuous man filled with a Holy "pre-existent spirit".

Neoplatonic influences

In the 1880s Gnostic connections with neo-Platonism were proposed. Ugo Bianchi, who organised the Congress of Messina of 1966 on the origins of Gnosticism, also argued for Orphic and Platonic origins. Gnostics borrowed significant ideas and terms from Platonism, using Greek philosophical concepts throughout their text, including such concepts as hypostasis

Hypostasis, hypostatic, or hypostatization (hypostatisation; from the Ancient Greek , "under state") may refer to:

* Hypostasis (philosophy and religion), the essence or underlying reality

** Hypostasis (linguistics), personification of entities

...

(reality, existence), ''ousia

''Ousia'' (; grc, οὐσία) is a philosophical and theological term, originally used in ancient Greek philosophy, then later in Christian theology. It was used by various ancient Greek philosophers, like Plato and Aristotle, as a primary d ...

'' (essence, substance, being), and demiurge (creator God). Both Sethian Gnostics and Valentinian Gnostics seem to have been influenced by Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institutio ...

, Middle Platonism

Middle Platonism is the modern name given to a stage in the development of Platonic philosophy, lasting from about 90 BC – when Antiochus of Ascalon rejected the scepticism of the new Academy – until the development of neoplatoni ...

, and Neo-Pythagoreanism

Neopythagoreanism (or neo-Pythagoreanism) was a school of Hellenistic philosophy which revived Pythagorean doctrines. Neopythagoreanism was influenced by middle Platonism and in turn influenced Neoplatonism. It originated in the 1st century BC ...

academies or schools of thought. Both schools attempted "an effort towards conciliation, even affiliation" with late antique philosophy,[Schenke, Hans Martin. "The Phenomenon and Significance of Gnostic Sethianism" in The Rediscovery of Gnosticism. E.J. Brill 1978] and were rebuffed by some Neoplatonists

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some i ...

, including Plotinus.

Persian origins or influences

Early research into the origins of Gnosticism proposed Persian origins or influences, spreading to Europe and incorporating Jewish elements. According to Wilhelm Bousset (1865–1920), Gnosticism was a form of Iranian and Mesopotamian syncretism, and Richard August Reitzenstein (1861–1931) situated the origins of Gnosticism in Persia.

Carsten Colpe (b. 1929) has analyzed and criticised the Iranian hypothesis of Reitzenstein, showing that many of his hypotheses are untenable. Nevertheless, Geo Widengren (1907–1996) argued for the origin of Mandaean Gnosticism in Mazdean (Zoroastrianism) Zurvanism, in conjunction with ideas from the Aramaic Mesopotamian world.

However, scholars specializing in Mandaeism such as Kurt Rudolph, Mark Lidzbarski, Rudolf Macúch, Ethel S. Drower, James F. McGrath

James Frank McGrath is the Clarence L. Goodwin Chair in New Testament Language and Literature at Butler University and is known for his work on Early Christianity, Mandaeism, criticism of the Christ myth theory, and the analysis of religion in ...

, Charles G. Häberl, Jorunn Jacobsen Buckley, and Şinasi Gündüz argue for a Palestinian origin. The majority of these scholars believe that the Mandaeans likely have a historical connection with John the Baptist's inner circle of disciples.

Buddhist parallels

In 1966, at the Congress of Median, Buddhologist Edward Conze

Edward Conze, born Eberhard Julius Dietrich Conze (1904–1979) was a scholar of Marxism and Buddhism, known primarily for his commentaries and translations of the Prajñāpāramitā literature.

Biography

Conze's parents, Dr. Ernst Conze (1872� ...

noted phenomenological commonalities between Mahayana Buddhism

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing bra ...

and Gnosticism, in his paper ''Buddhism and Gnosis'', following an early suggestion put forward by Isaac Jacob Schmidt

Isaac Jacob Schmidt (October 4, 1779 – August 27, 1847) was an Orientalist specializing in Mongolian and Tibetan. Schmidt was a Moravian missionary to the Kalmyks and devoted much of his labours to Bible translation.

Born in Amsterdam, he s ...

. The influence of Buddhism in any sense on either the ''gnostikos'' Valentinus (c.170) or the Nag Hammadi texts (3rd century) is not supported by modern scholarship, although Elaine Pagels

Elaine Pagels, née Hiesey (born February 13, 1943), is an American historian of religion. She is the Harrington Spear Paine Professor of Religion at Princeton University. Pagels has conducted extensive research into early Christianity and Gnost ...

(1979) called it a "possibility".

Characteristics

Cosmology

The Syrian–Egyptian traditions postulate a remote, supreme Godhead, the Monad. From this highest divinity emanate

''Emanate'' is the debut studio album by the French gothic metal band Penumbra (band), Penumbra, launched in 1999 originally under German label Serenades Records.

Track listing

# "Intro" - 02:11

# "Lycantrope"- 04:41

# "New Searing Senses" - 0 ...

lower divine beings, known as Aeons

The word aeon , also spelled eon (in American and Australian English), originally meant "life", "vital force" or "being", "generation" or "a period of time", though it tended to be translated as "age" in the sense of "ages", "forever", "timeles ...

. The Demiurge

In the Platonic, Neopythagorean, Middle Platonic, and Neoplatonic schools of philosophy, the demiurge () is an artisan-like figure responsible for fashioning and maintaining the physical universe. The Gnostics adopted the term ''demiurge''. ...

, one of those Aeons, creates the physical world. Divine elements "fall" into the material realm, and are locked within human beings. This divine element returns to the divine realm when Gnosis, esoteric

Western esotericism, also known as esotericism, esoterism, and sometimes the Western mystery tradition, is a term scholars use to categorise a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements that developed within Western society. These ideas a ...

or intuitive knowledge

Intuition is the ability to acquire knowledge without recourse to conscious reasoning. Different fields use the word "intuition" in very different ways, including but not limited to: direct access to unconscious knowledge; unconscious cognitio ...

of the divine element within, is obtained.

Dualism and monism

Gnostic systems postulate a dualism

Dualism most commonly refers to:

* Mind–body dualism, a philosophical view which holds that mental phenomena are, at least in certain respects, not physical phenomena, or that the mind and the body are distinct and separable from one another

** ...

between God and the world, varying from the "radical dualist" systems of Manichaeism

Manichaeism (;

in New Persian ; ) is a former major religionR. van den Broek, Wouter J. Hanegraaff ''Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times''SUNY Press, 1998 p. 37 founded in the 3rd century AD by the Parthian prophet Mani ( ...

to the "mitigated dualism" of classic gnostic movements. Radical dualism, or absolute dualism, posits two co-equal divine forces, while in ''mitigated dualism'' one of the two principles is in some way inferior to the other. In ''qualified monism'' the second entity may be divine or semi-divine. Valentinian Gnosticism is a form of monism

Monism attributes oneness or singleness (Greek: μόνος) to a concept e.g., existence. Various kinds of monism can be distinguished:

* Priority monism states that all existing things go back to a source that is distinct from them; e.g., i ...

, expressed in terms previously used in a dualistic manner.

Moral and ritual practice

Gnostics tended toward asceticism

Asceticism (; from the el, ἄσκησις, áskesis, exercise', 'training) is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from sensual pleasures, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their p ...

, especially in their sexual and dietary practice. In other areas of morality, Gnostics were less rigorously ascetic, and took a more moderate approach to correct behaviour. In normative early Christianity the Church administered and prescribed the correct behaviour for Christians, while in Gnosticism it was the internalised motivation that was important. Ritualistic behaviour was not important unless it was based on a personal, internal motivation. Ptolemy's '' Epistle to Flora'' describes a general asceticism, based on the moral inclination of the individual.

Concepts

Monad

In many Gnostic systems, God is known as the ''Monad'', the One. God is the high source of the pleroma, the region of light. The various emanations of God are called æons. According to Hippolytus, this view was inspired by the Pythagoreans

Pythagoreanism originated in the 6th century BC, based on and around the teachings and beliefs held by Pythagoras and his followers, the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras established the first Pythagorean community in the ancient Greek colony of Kroton, ...

, who called the first thing that came into existence the ''Monad'', which begat the dyad, which begat the numbers, which begat the point, begetting lines, etc.

Pleroma

''Pleroma'' (Greek πλήρωμα, "fullness") refers to the totality of God's powers. The heavenly pleroma is the center of divine life, a region of light "above" (the term is not to be understood spatially) our world, occupied by spiritual beings such as aeons (eternal beings) and sometimes archons. Jesus is interpreted as an intermediary aeon who was sent from the pleroma, with whose aid humanity can recover the lost knowledge of the divine origins of humanity. The term is thus a central element of Gnostic cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosophe ...

.

Pleroma is also used in the general Greek language, and is used by the Greek Orthodox church

The term Greek Orthodox Church (Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the entire body of Orthodox (Chalcedonian) Christianity, sometimes also call ...

in this general form, since the word appears in the Epistle to the Colossians

The Epistle to the Colossians is the twelfth book of the New Testament. It was written, according to the text, by Paul the Apostle and Timothy, and addressed to the church in Colossae, a small Phrygian city near Laodicea and approximately ...

. Proponents of the view that Paul was actually a gnostic, such as Elaine Pagels

Elaine Pagels, née Hiesey (born February 13, 1943), is an American historian of religion. She is the Harrington Spear Paine Professor of Religion at Princeton University. Pagels has conducted extensive research into early Christianity and Gnost ...

, view the reference in Colossians as a term that has to be interpreted in a gnostic sense.

Emanation

The Supreme Light or Consciousness descends through a series of stages, gradations, worlds, or hypostases, becoming progressively more material and embodied. In time it will turn around to return to the One (epistrophe), retracing its steps through spiritual knowledge and contemplation.

Aeon

In many Gnostic systems, the aeons are the various emanations of the superior God or Monad. Beginning in certain Gnostic texts with the hermaphroditic aeon Barbelo,

Sophia

In Gnostic tradition, the term ''Sophia'' (Σοφία, Greek for "wisdom") refers to the final and lowest emanation of God, and is identified with the '' anima mundi'' or world-soul. In most, if not all, versions of the gnostic myth, Sophia births the demiurge, who in turn brings about the creation of materiality. The positive or negative depiction of materiality thus resides a great deal on mythic depictions of Sophia's actions. She is occasionally referred to by the Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

equivalent of ''Achamoth'' (this is a feature of Ptolemy's version of the Valentinian gnostic myth). Jewish Gnosticism with a focus on Sophia was active by 90 AD.

''Sophia'', emanating without her partner, resulted in the production of the ''Demiurge'' (Greek: lit. "public builder"),

Demiurge

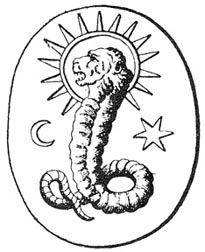

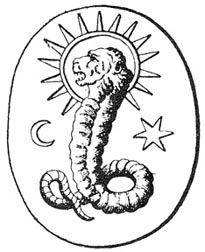

The term ''demiurge'' derives from the

The term ''demiurge'' derives from the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

ized form of the Greek term ''dēmiourgos'', δημιουργός, literally "public or skilled worker". This figure is also called "Yaldabaoth",Aramaic

The Aramaic languages, short Aramaic ( syc, ܐܪܡܝܐ, Arāmāyā; oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; tmr, אֲרָמִית), are a language family containing many varieties (languages and dialects) that originated i ...

: ''sæmʻa-ʼel'', "blind god"), or "Saklas" ( Syriac: ''sækla'', "the foolish one"), who is sometimes ignorant of the superior god, and sometimes opposed to it; thus in the latter case he is correspondingly malevolent. Other names or identifications are Ahriman

Angra Mainyu (; Avestan: 𐬀𐬢𐬭𐬀⸱𐬨𐬀𐬌𐬥𐬌𐬌𐬎 ''Aŋra Mainiiu'') is the Avestan-language name of Zoroastrianism's hypostasis of the "destructive/evil spirit" and the main adversary in Zoroastrianism either of the ...

, El, Satan

Satan,, ; grc, ὁ σατανᾶς or , ; ar, شيطانالخَنَّاس , also known as the Devil, and sometimes also called Lucifer in Christianity, is an entity in the Abrahamic religions that seduces humans into sin or falsehoo ...

, and Yahweh

Yahweh *''Yahwe'', was the national god of ancient Israel and Judah. The origins of his worship reach at least to the early Iron Age, and likely to the Late Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately fr ...

.

The demiurge creates the physical universe and the physical aspect of humanity.archons

''Archon'' ( gr, ἄρχων, árchōn, plural: ἄρχοντες, ''árchontes'') is a Greek word that means "ruler", frequently used as the title of a specific public office. It is the masculine present participle of the verb stem αρχ-, mean ...

who preside over the material realm and, in some cases, present obstacles to the soul seeking ascent from it.ascetic

Asceticism (; from the el, ἄσκησις, áskesis, exercise', 'training) is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from sensual pleasures, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their p ...

tendency to view material existence negatively, which then becomes more extreme when materiality, including the human body, is perceived as evil and constrictive, a deliberate prison for its inhabitants.

Moral judgements of the demiurge vary from group to group within the broad category of Gnosticism, viewing materiality as being inherently evil, or as merely flawed and as good as its passive constituent matter allows.

Archon

In late antiquity some variants of Gnosticism used the term archon to refer to several servants of the demiurge.Origen

Origen of Alexandria, ''Ōrigénēs''; Origen's Greek name ''Ōrigénēs'' () probably means "child of Horus" (from , "Horus", and , "born"). ( 185 – 253), also known as Origen Adamantius, was an early Christian scholar, ascetic, and the ...

's ''Contra Celsum

''Against Celsus'' (Greek: Κατὰ Κέλσου ''Kata Kelsou''; Latin: ''Contra Celsum''), preserved entirely in Greek, is a major apologetics work by the Church Father Origen of Alexandria, written in around 248 AD, countering the writin ...

'', a sect called the Ophites posited the existence of seven archons, beginning with Iadabaoth or Ialdabaoth, who created the six that follow: Iao, Sabaoth

Judaism considers some names of God so holy that, once written, they should not be erased: YHWH, Adonai, El ("God"), Elohim ("God," a plural noun), Shaddai ("Almighty"), and Tzevaot (" fHosts"); some also include Ehyeh ("I Will Be").This is t ...

, Adonaios, Elaios, Astaphanos, and Horaios.

Other concepts

Other Gnostic concepts are:

* sarkic

Sarkic, from the Greek ''σάρξ'', flesh (or hylic, from the Greek ''ὕλη'', stuff, or matter) in Gnosticism describes the lowest level of human nature—the fleshly, instinctive level. This is not the notion of body as opposed to thought; ...

– earthly, hidebound, ignorant, uninitiated. The lowest level of human thought; the fleshly, instinctive level of thinking.

* hylic – lowest order of the three types of human. Unable to be saved since their thinking is entirely material, incapable of understanding the gnosis.

* psychic – "soulful", partially initiated. Matter-dwelling spirits

* pneumatic – "spiritual", fully initiated, immaterial souls escaping the doom of the material world via gnosis.

* kenoma – the visible or manifest cosmos, "lower" than the pleroma

* charisma

Charisma () is a personal quality of presence or charm that compels its subjects.

Scholars in sociology, political science, psychology, and management reserve the term for a type of leadership seen as extraordinary; in these fields, the term "ch ...

– gift, or energy, bestowed by pneumatics through oral teaching and personal encounters

* logos

''Logos'' (, ; grc, λόγος, lógos, lit=word, discourse, or reason) is a term used in Western philosophy, psychology and rhetoric and refers to the appeal to reason that relies on logic or reason, inductive and deductive reasoning. Aristo ...

– the divine ordering principle of the cosmos; personified as Christ. See also Odic force

The Odic force (also called Od �d Odyle, Önd, Odes, Odylic, Odyllic, or Odems) is the name given in the mid-19th century to a hypothetical vital energy or life force by Baron Carl von Reichenbach. Von Reichenbach coined the name from that of ...

.

* hypostasis

Hypostasis, hypostatic, or hypostatization (hypostatisation; from the Ancient Greek , "under state") may refer to:

* Hypostasis (philosophy and religion), the essence or underlying reality

** Hypostasis (linguistics), personification of entities

...

– literally "that which stands beneath" the inner reality, emanation (appearance) of God, known to psychics

* ousia

''Ousia'' (; grc, οὐσία) is a philosophical and theological term, originally used in ancient Greek philosophy, then later in Christian theology. It was used by various ancient Greek philosophers, like Plato and Aristotle, as a primary d ...

– essence of God, known to pneumatics. Specific individual things or being.

Jesus as Gnostic saviour

Jesus is identified by some Gnostics as an embodiment of the supreme being

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

who became incarnate to bring ''gnōsis'' to the earth,Docetist

In the history of Christianity, docetism (from the grc-koi, δοκεῖν/δόκησις ''dokeĩn'' "to seem", ''dókēsis'' "apparition, phantom") is the heterodox doctrine that the phenomenon of Jesus, his historical and bodily existence, an ...

movement. Among the Mandaeans

Mandaeans ( ar, المندائيون ), also known as Mandaean Sabians ( ) or simply as Sabians ( ), are an ethnoreligious group who are followers of Mandaeism. They believe that John the Baptist was the final and most important prophet. They ...

, Jesus was considered a ''mšiha kdaba'' or "false messiah

This is a list of notable people who have been said to be a messiah, either by themselves or by their followers. The list is divided into categories, which are sorted according to date of birth (where known).

Jewish messiah claimants

In Judaism, ...

" who perverted the teachings entrusted to him by John the Baptist

John the Baptist or , , or , ;Wetterau, Bruce. ''World history''. New York: Henry Holt and Company. 1994. syc, ܝܘܿܚܲܢܵܢ ܡܲܥܡܕ݂ܵܢܵܐ, Yoḥanān Maʿmḏānā; he, יוחנן המטביל, Yohanān HaMatbil; la, Ioannes Bapti ...

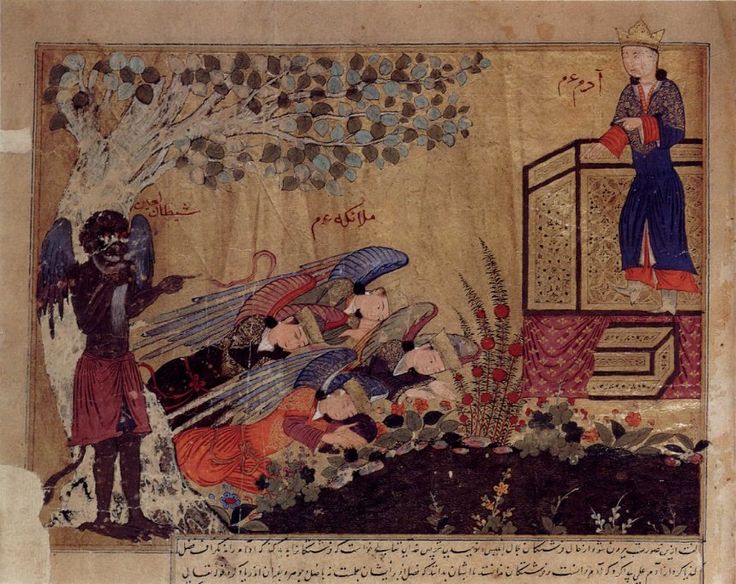

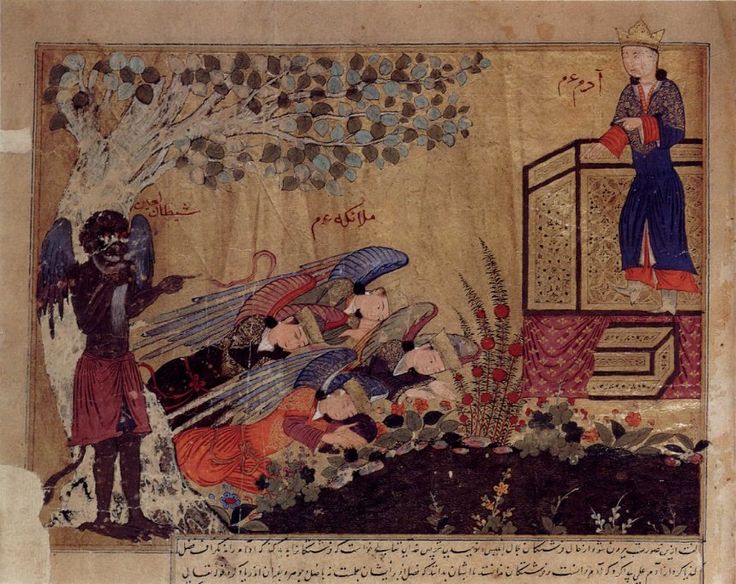

.Seth

Seth,; el, Σήθ ''Sḗth''; ; "placed", "appointed") in Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Mandaeism, and Sethianism, was the third son of Adam and Eve and brother of Cain and Abel, their only other child mentioned by name in the Hebrew Bible. ...

, third son of Adam and Eve

Adam and Eve, according to the creation myth of the Abrahamic religions, were the first man and woman. They are central to the belief that humanity is in essence a single family, with everyone descended from a single pair of original ancestors ...

, as salvific figures.

Development

Three periods can be discerned in the development of Gnosticism:

* Late-first century and early second century: development of Gnostic ideas, contemporaneous with the writing of the New Testament;

* mid-second century to early third century: high point of the classical Gnostic teachers and their systems, "who claimed that their systems represented the inner truth revealed by Jesus";

* end of the second century to the fourth century: reaction by the proto-orthodox church and condemnation as heresy, and subsequent decline.

During the first period, three types of tradition developed:

* Genesis was reinterpreted in Jewish milieus, viewing Yahweh

Yahweh *''Yahwe'', was the national god of ancient Israel and Judah. The origins of his worship reach at least to the early Iron Age, and likely to the Late Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately fr ...

as a jealous God who enslaved people; freedom was to be obtained from this jealous God;

* A wisdom tradition developed, in which Jesus' sayings were interpreted as pointers to an esoteric wisdom, in which the soul could be divinized through identification with wisdom. Some of Jesus' sayings may have been incorporated into the gospels to put a limit on this development. The conflicts described in 1 Corinthians may have been inspired by a clash between this wisdom tradition and Paul's gospel of crucifixion and arising;

* A mythical story developed about the descent of a heavenly creature to reveal the Divine world as the true home of human beings. Jewish Christianity saw the Messiah, or Christ, as "an eternal aspect of God's hidden nature, his "spirit" and "truth", who revealed himself throughout sacred history".

The movement spread in areas controlled by the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Medite ...

and Arian

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by G ...

Goths, and the Persian Empire. It continued to develop in the Mediterranean and Middle East before and during the 2nd and 3rd centuries, but decline also set in during the third century, due to a growing aversion from the Nicene Church, and the economic and cultural deterioration of the Roman Empire. Conversion to Islam, and the Albigensian Crusade

The Albigensian Crusade or the Cathar Crusade (; 1209–1229) was a military and ideological campaign initiated by Pope Innocent III to eliminate Catharism in Languedoc, southern France. The Crusade was prosecuted primarily by the French crow ...

(1209–1229), greatly reduced the remaining number of Gnostics throughout the Middle Ages, though Mandaean communities still exist in Iraq, Iran and diaspora communities. Gnostic and pseudo-gnostic ideas became influential in some of the philosophies of various esoteric mystical

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight in u ...

movements of the 19th and 20th centuries in Europe and North America, including some that explicitly identify themselves as revivals or even continuations of earlier gnostic groups.

Relation with early Christianity

Dillon notes that Gnosticism raises questions about the development of early Christianity

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Je ...

.

Orthodoxy and heresy

The Christian heresiologists, most notably Irenaeus

Irenaeus (; grc-gre, Εἰρηναῖος ''Eirēnaios''; c. 130 – c. 202 AD) was a Greek bishop noted for his role in guiding and expanding Christian communities in the southern regions of present-day France and, more widely, for the dev ...

, regarded Gnosticism as a Christian heresy. Modern scholarship notes that early Christianity was diverse, and Christian orthodoxy only settled in the 4thcentury, when the Roman Empire declined and Gnosticism lost its influence. Gnostics and proto-orthodox Christians shared some terminology. Initially, they were hard to distinguish from each other.

According to Walter Bauer, "heresies" may well have been the original form of Christianity in many regions. This theme was further developed by Elaine Pagels, who argues that "the proto-orthodox church found itself in debates with gnostic Christians that helped them to stabilize their own beliefs." According to Gilles Quispel, Catholicism arose in response to Gnosticism, establishing safeguards in the form of the monarchic episcopate, the creed, and the canon of holy books.

Historical Jesus

The Gnostic movements may contain information about the historical Jesus, since some texts preserve sayings which show similarities with canonical sayings. Especially the Gospel of Thomas

The Gospel of Thomas (also known as the Coptic Gospel of Thomas) is an extra-canonical sayings gospel. It was discovered near Nag Hammadi, Egypt, in December 1945 among a group of books known as the Nag Hammadi library. Scholars speculat ...

has a significant amount of parallel sayings. Yet, a striking difference is that the canonical sayings center on the coming endtime, while the Thomas-sayings center on a kingdom of heaven that is already here, and not a future event. According to Helmut Koester, this is because the Thomas-sayings are older, implying that in the earliest forms of Christianity Jesus was regarded as a wisdom-teacher. An alternative hypothesis states that the Thomas authors wrote in the second century, changing existing sayings and eliminating the apocalyptic concerns. According to April DeConick, such a change occurred when the end time did not come, and the Thomasine tradition turned toward a "new theology of mysticism" and a "theological commitment to a fully-present kingdom of heaven here and now, where their church had attained Adam and Eve's divine status before the Fall."

Johannine literature

The prologue of the Gospel of John

The Gospel of John ( grc, Εὐαγγέλιον κατὰ Ἰωάννην, translit=Euangélion katà Iōánnēn) is the fourth of the four canonical gospels. It contains a highly schematic account of the ministry of Jesus, with seven "sig ...

describes the incarnated Logos

''Logos'' (, ; grc, λόγος, lógos, lit=word, discourse, or reason) is a term used in Western philosophy, psychology and rhetoric and refers to the appeal to reason that relies on logic or reason, inductive and deductive reasoning. Aristo ...

, the light that came to earth, in the person of Jesus. The '' Apocryphon of John'' contains a scheme of three descendants from the heavenly realm, the third one being Jesus, just as in the Gospel of John. The similarities probably point to a relationship between gnostic ideas and the Johannine community. According to Raymond Brown, the Gospel of John shows "the development of certain gnostic ideas, especially Christ as heavenly revealer, the emphasis on light versus darkness, and anti-Jewish animus." The Johannine material reveals debates about the redeemer myth. The Johannine letters show that there were different interpretations of the gospel story, and the Johannine images may have contributed to second-century Gnostic ideas about Jesus as a redeemer who descended from heaven. According to DeConick, the Gospel of John shows a "transitional system from early Christianity to gnostic beliefs in a God who transcends our world." According to DeConick, ''John'' may show a bifurcation of the idea of the Jewish God into Jesus' Father in Heaven and the Jews' father, "the Father of the Devil" (most translations say "of ourfather the Devil"), which may have developed into the gnostic idea of the Monad and the Demiurge.

Paul and Gnosticism

Tertullian

Tertullian (; la, Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus; 155 AD – 220 AD) was a prolific early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive corpus of ...

calls Paul "the apostle of the heretics", because Paul's writings were attractive to gnostics, and interpreted in a gnostic way, while Jewish Christians found him to stray from the Jewish roots of Christianity. In I Corinthians Paul refers to some church members as "having knowledge" ( gr, τὸν ἔχοντα γνῶσιν, ''ton echonta gnosin''). James Dunn claims that in some cases, Paul affirmed views that were closer to gnosticism than to proto-orthodox Christianity.

According to Clement of Alexandria

Titus Flavius Clemens, also known as Clement of Alexandria ( grc , Κλήμης ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς; – ), was a Christian theologian and philosopher who taught at the Catechetical School of Alexandria. Among his pupils were Origen an ...

, the disciples of Valentinus said that Valentinus was a student of a certain Theudas, who was a student of Paul, and Elaine Pagels notes that Paul's epistles were interpreted by Valentinus in a gnostic way, and Paul could be considered a proto-gnostic as well as a proto-Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

. Many Nag Hammadi texts, including, for example, the ''Prayer of Paul'' and the Coptic ''Apocalypse of Paul'', consider Paul to be "the great apostle". The fact that he claimed to have received his gospel directly by revelation from God appealed to the gnostics, who claimed ''gnosis'' from the risen Christ. The Naassenes

The Naassenes (Greek ''Naasseni,'' possibly from Hebrew נָחָשׁ ''naḥaš'', snake) were a Christian Gnostic sect known only through the writings of Hippolytus of Rome.

The Naassenes claimed to have been taught their doctrines by Mariamne, ...

, Cainites, and Valentinians referred to Paul's epistles. Timothy Freke and Peter Gandy have expanded upon this idea of Paul as a gnostic teacher; although their premise that Jesus was invented by early Christians based on an alleged Greco-Roman mystery cult has been dismissed by scholars. However, his revelation was different from the gnostic revelations.

Major movements

Judean-Israelite Gnosticism

Although Elkesaites and Mandaeans were found mainly in Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

in the first few centuries of the common era, their origins appear be to Judean / Israelite in the Jordan valley.

Elkesaites

The Elkesaites were a Judeo-Christian baptismal sect that originated in the Transjordan and were active between 100 to 400 CE.Essenes

The Essenes (; Hebrew: , ''Isiyim''; Greek: Ἐσσηνοί, Ἐσσαῖοι, or Ὀσσαῖοι, ''Essenoi, Essaioi, Ossaioi'') were a mystic Jewish sect during the Second Temple period that flourished from the 2nd century BCE to the 1st ce ...

:Epiphanius of Salamis

Epiphanius of Salamis ( grc-gre, Ἐπιφάνιος; c. 310–320 – 403) was the bishop of Salamis, Cyprus, at the end of the 4th century. He is considered a saint and a Church Father by both the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic Churches. He ...

(). '' Panarion''

1:19

Mandaeism

Mandaeism is a Gnostic,

Mandaeism is a Gnostic, monotheistic

Monotheism is the belief that there is only one deity, an all-supreme being that is universally referred to as God. Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Monotheism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxfor ...

and ethnic religion

In religious studies, an ethnic religion is a religion or belief associated with a particular ethnic group. Ethnic religions are often distinguished from universal religions, such as Christianity or Islam, in which gaining converts is a pr ...

.ethnoreligious group

An ethnoreligious group (or an ethno-religious group) is a grouping of people who are unified by a common religious and ethnic background.

Furthermore, the term ethno-religious group, along with ethno-regional and ethno-linguistic groups, is a ...

that speak a dialect of Eastern Aramaic

The Eastern Aramaic languages have developed from the varieties of Aramaic that developed in and around Mesopotamia ( Iraq, southeast Turkey, northeast Syria and northwest and southwest Iran), as opposed to western varieties of the Levant (m ...

known as Mandaic. They are the only surviving Gnostics from antiquity.Tigris

The Tigris () is the easternmost of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, and empties into the ...

and the rivers that surround the Shatt-al-Arab waterway, part of southern Iraq and Khuzestan Province

Khuzestan Province (also spelled Xuzestan; fa, استان خوزستان ''Ostān-e Xūzestān'') is one of the 31 provinces of Iran. It is in the southwest of the country, bordering Iraq and the Persian Gulf. Its capital is Ahvaz and it cover ...

in Iran. Mandaeism is still practiced in small numbers, in parts of southern Iraq and the Iranian province of Khuzestan

Khuzestan Province (also spelled Xuzestan; fa, استان خوزستان ''Ostān-e Xūzestān'') is one of the 31 provinces of Iran. It is in the southwest of the country, bordering Iraq and the Persian Gulf. Its capital is Ahvaz and it cover ...

, and there are thought to be between 60,000 and 70,000 Mandaeans worldwide.[Iraqi minority group needs U.S. attention](_blank)

, Kai Thaler, ''Yale Daily News'', March 9, 2007.

The name 'Mandaean' comes from the Aramaic '' manda'' meaning knowledge.John the Baptist

John the Baptist or , , or , ;Wetterau, Bruce. ''World history''. New York: Henry Holt and Company. 1994. syc, ܝܘܿܚܲܢܵܢ ܡܲܥܡܕ݂ܵܢܵܐ, Yoḥanān Maʿmḏānā; he, יוחנן המטביל, Yohanān HaMatbil; la, Ioannes Bapti ...

is a key figure in the religion, as an emphasis on baptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost inv ...

is part of their core beliefs. According to Nathaniel Deutsch

Nathaniel Deutsch is a professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz, where he holds the Baumgarten Endowed Chair in Jewish Studies. He is also the Director of the Center for Jewish Studies and the Director of the Humanities Institute.

Car ...

, "Mandaean anthropogony echoes both rabbinic and gnostic accounts." Mandaeans

Mandaeans ( ar, المندائيون ), also known as Mandaean Sabians ( ) or simply as Sabians ( ), are an ethnoreligious group who are followers of Mandaeism. They believe that John the Baptist was the final and most important prophet. They ...

revere Adam

Adam; el, Ἀδάμ, Adám; la, Adam is the name given in Genesis 1-5 to the first human. Beyond its use as the name of the first man, ''adam'' is also used in the Bible as a pronoun, individually as "a human" and in a collective sense as " ...

, Abel

Abel ''Hábel''; ar, هابيل, Hābīl is a Biblical figure in the Book of Genesis within Abrahamic religions. He was the younger brother of Cain, and the younger son of Adam and Eve, the first couple in Biblical history. He was a shepherd ...

, Seth

Seth,; el, Σήθ ''Sḗth''; ; "placed", "appointed") in Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Mandaeism, and Sethianism, was the third son of Adam and Eve and brother of Cain and Abel, their only other child mentioned by name in the Hebrew Bible. ...

, Enos, Noah

Noah ''Nukh''; am, ኖህ, ''Noḥ''; ar, نُوح '; grc, Νῶε ''Nôe'' () is the tenth and last of the pre-Flood patriarchs in the traditions of Abrahamic religions. His story appears in the Hebrew Bible (Book of Genesis, chapters 5� ...

, Shem

Shem (; he, שֵׁם ''Šēm''; ar, سَام, Sām) ''Sḗm''; Ge'ez: ሴም, ''Sēm'' was one of the sons of Noah in the book of Genesis and in the book of Chronicles, and the Quran.

The children of Shem were Elam, Ashur, Arphaxad, L ...

, Aram, and especially John the Baptist. Significant amounts of original Mandaean Scripture, written in Mandaean Aramaic, survive in the modern era. The most important holy scripture is known as the Ginza Rabba

The Ginza Rabba ( myz, ࡂࡉࡍࡆࡀ ࡓࡁࡀ, translit=Ginzā Rbā, lit=Great Treasury), Ginza Rba, or Sidra Rabba ( myz, ࡎࡉࡃࡓࡀ ࡓࡁࡀ, translit=Sidrā Rbā, lit=Great Book), and formerly the Codex Nasaraeus, is the longest ...

and has portions identified by some scholars as being copied as early as the 2nd–3rd centuries,Qolastā

The Qolastā, Qulasta, or Qolusta ( myz, ࡒࡅࡋࡀࡎࡕࡀ; mid, Qōlutā, script=Latn) is the canonical prayer book of the Mandaeans, a Gnostic ethnoreligious group from Iraq and Iran. The Mandaic word ''qolastā'' means "collection". The p ...

, or Canonical Book of Prayer and the Mandaean Book of John (Sidra ḏ'Yahia) and other scriptures

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual pract ...

.

Mandaeans believe that there is a constant battle or conflict between the forces of good and evil. The forces of good are represented by ''Nhura'' (Light) and ''Maia Hayyi'' ( Living Water) and those of evil are represented by ''Hshuka'' (Darkness) and ''Maia Tahmi'' (dead or rancid water). The two waters are mixed in all things in order to achieve a balance. Mandaeans also believe in an afterlife or heaven called ''Alma d-Nhura'' (World of Light

In Mandaeism, the World of Light or Lightworld ( myz, ࡀࡋࡌࡀ ࡖࡍࡄࡅࡓࡀ, translit=alma ḏ-nhūra) is the primeval, transcendental world from which Tibil and the World of Darkness emerged.

Description

*The Great Life ('' Hayyi Ra ...

).World of Light

In Mandaeism, the World of Light or Lightworld ( myz, ࡀࡋࡌࡀ ࡖࡍࡄࡅࡓࡀ, translit=alma ḏ-nhūra) is the primeval, transcendental world from which Tibil and the World of Darkness emerged.

Description

*The Great Life ('' Hayyi Ra ...

is ruled by a Supreme God, known as Hayyi Rabbi ('The Great Life' or 'The Great Living God').[Drower, Ethel Stefana. ''The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran''. Oxford At The Clarendon Press, 1937.][ God is so great, vast, and incomprehensible that no words can fully depict how awesome God is. It is believed that an innumerable number of ]Uthra

An uthra or ʿutra ( myz, ࡏࡅࡕࡓࡀ; plural: ʿutri) is a "divine messenger of the light" in Mandaeism. Charles G. Häberl and James F. McGrath translate it as "excellency". Jorunn J. Buckley defines them as "Lightworld beings, called 'ut ...

s (angels or guardians),Ptahil

In Mandaeism, Ptahil ( myz, ࡐࡕࡀࡄࡉࡋ) also known as Ptahil-Uthra (uthra = angel or guardian), is the Fourth Life, the third of three emanations from the First Life, Hayyi Rabbi, after Yushamin and Abatur. Ptahil-Uthra alone does not con ...

).Krun

Krun (; myz, ࡊࡓࡅࡍ) or Akrun () is a Mandaean lord of the underworld. According to Mandaean cosmology, he dwells in the lowest depths of creation, supporting the entirety of the physical world.

In mythology

Krun is the greatest of the ...

) is the ruler of the World of Darkness formed from dark waters representing chaos.Ptahil

In Mandaeism, Ptahil ( myz, ࡐࡕࡀࡄࡉࡋ) also known as Ptahil-Uthra (uthra = angel or guardian), is the Fourth Life, the third of three emanations from the First Life, Hayyi Rabbi, after Yushamin and Abatur. Ptahil-Uthra alone does not con ...

, who fills the role of the demiurge

In the Platonic, Neopythagorean, Middle Platonic, and Neoplatonic schools of philosophy, the demiurge () is an artisan-like figure responsible for fashioning and maintaining the physical universe. The Gnostics adopted the term ''demiurge''. ...

, with help from dark powers, such as Ruha the Seven, and the Twelve.[Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen (2010). Turning the Tables on Jesus: The Mandaean View. In (pp94-111). Minneapolis: Fortress Press] Others claim a southwestern Mesopotamia origin.[Drower, Ethel Stefana. The Haran Gawaita and the Baptism of Hibil-Ziwa. Biblioteca Apostolica Vatican, 1953]

Due to paraphrases and word-for-word translations from the Mandaean originals found in the '' Psalms of Thomas'', it is now believed that the pre-Manichaean presence of the Mandaean religion is more than likely.[ ]Birger A. Pearson Birger A. Pearson (born 1934 in California, United States) is an American scholar and professor studying early Christianity and Gnosticism. He currently holds the positions of Professor Emeritus of Religious Studies at the University of California, ...

compares the '' Five Seals'' of Sethianism, which he believes is a reference to quintuple ritual immersion in water, to Mandaean '' masbuta''.

Samaritan Baptist sects

According to Magris, Samaritan Baptist sects were an offshoot of John the Baptist

John the Baptist or , , or , ;Wetterau, Bruce. ''World history''. New York: Henry Holt and Company. 1994. syc, ܝܘܿܚܲܢܵܢ ܡܲܥܡܕ݂ܵܢܵܐ, Yoḥanān Maʿmḏānā; he, יוחנן המטביל, Yohanān HaMatbil; la, Ioannes Bapti ...

. One offshoot was in turn headed by Dositheus, Simon Magus

Simon Magus ( Greek Σίμων ὁ μάγος, Latin: Simon Magus), also known as Simon the Sorcerer or Simon the Magician, was a religious figure whose confrontation with Peter is recorded in Acts . The act of simony, or paying for position, i ...

, and Menander

Menander (; grc-gre, Μένανδρος ''Menandros''; c. 342/41 – c. 290 BC) was a Greek dramatist and the best-known representative of Athenian New Comedy. He wrote 108 comedies and took the prize at the Lenaia festival eight times. His re ...

. It was in this milieu that the idea emerged that the world was created by ignorant angels. Their baptismal ritual removed the consequences of sin, and led to a regeneration by which natural death, which was caused by these angels, was overcome. The Samaritan leaders were viewed as "the embodiment of God's power, spirit, or wisdom, and as the redeemer and revealer of 'true knowledge.

The Simonians were centered on Simon Magus, the magician baptised by Philip and rebuked by Peter in Acts 8, who became in early Christianity the archetypal false teacher. The ascription by Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, and others of a connection between schools in their time and the individual in Acts 8 may be as legendary as the stories attached to him in various apocryphal books. Justin Martyr identifies Menander of Antioch as Simon Magus' pupil. According to Hippolytus, Simonianism is an earlier form of the Valentinian doctrine.

The Quqites were a group who followed a Samaritan, Iranian

Iranian may refer to:

* Iran, a sovereign state

* Iranian peoples, the speakers of the Iranian languages. The term Iranic peoples is also used for this term to distinguish the pan ethnic term from Iranian, used for the people of Iran

* Iranian lan ...

type of Gnosticism in 2nd-century AD Erbil

Erbil, also called Hawler (, ar, أربيل, Arbīl; syr, ܐܲܪܒܹܝܠ, Arbel), is the capital and most populated city in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. It lies in the Erbil Governorate. It has an estimated population of around 1,600,000.

H ...

and in the vicinity of what is today northern Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

. The sect was named after their founder Quq, known as "the potter". The Quqite ideology arose in Edessa

Edessa (; grc, Ἔδεσσα, Édessa) was an ancient city ('' polis'') in Upper Mesopotamia, founded during the Hellenistic period by King Seleucus I Nicator (), founder of the Seleucid Empire. It later became capital of the Kingdom of Os ...

, Syria, in the 2nd century. The Quqites stressed the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;["Tanach"](_blank)

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

, made changes in the New Testament, associated twelve prophets with twelve apostles, and held that the latter corresponded to the same number of gospels. Their beliefs seem to have been eclectic, with elements of Judaism, Christianity, paganism, astrology, and Gnosticism.

Syrian-Egyptian Gnosticism

Syrian-Egyptian Gnosticism includes Sethianism

The Sethians were one of the main currents of Gnosticism during the 2nd and 3rd century CE, along with Valentinianism and Basilideanism. According to John D. Turner, it originated in the 2nd century CE as a fusion of two distinct Hellenistic ...

, Valentinianism

Valentinianism was one of the major Gnostic Christian movements. Founded by Valentinus in the 2nd century AD, its influence spread widely, not just within Rome but also from Northwest Africa to Egypt through to Asia Minor and Syria in the East. L ...

, Basilideans, Thomasine traditions, and Serpent Gnostics, as well as a number of other minor groups and writers. Hermeticism is also a western Gnostic tradition, though it differs in some respects from these other groups.Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

forms. Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

and several of his apostles, such as Thomas the Apostle

Thomas the Apostle ( arc, 𐡀𐡌𐡅𐡕𐡌, hbo, תוֹמא הקדוש or תוֹמָא שליחא (''Toma HaKadosh'' "Thomas the Holy" or ''Toma Shlikha'' "Thomas the Messenger/Apostle" in Hebrew-Aramaic), syc, ܬܐܘܡܐ, , meaning "twi ...

, claimed as the founder of the Thomasine form of Gnosticism, figure in many Gnostic texts. Mary Magdalene

Mary Magdalene (sometimes called Mary of Magdala, or simply the Magdalene or the Madeleine) was a woman who, according to the four canonical gospels, traveled with Jesus as one of his followers and was a witness to his crucifixion and

resurr ...

is respected as a Gnostic leader, and is considered superior to the twelve apostles

In Christian theology and ecclesiology, the apostles, particularly the Twelve Apostles (also known as the Twelve Disciples or simply the Twelve), were the primary disciples of Jesus according to the New Testament. During the life and minis ...

by some gnostic texts, such as the Gospel of Mary

The Gospel of Mary is a non-canonical text discovered in 1896 in a 5th-century papyrus codex written in Sahidic Coptic. This Berlin Codex was purchased in Cairo by German diplomat Carl Reinhardt.

Although the work is popularly known as the Go ...

. John the Evangelist

John the Evangelist ( grc-gre, Ἰωάννης, Iōánnēs; Aramaic: ܝܘܚܢܢ; Ge'ez: ዮሐንስ; ar, يوحنا الإنجيلي, la, Ioannes, he, יוחנן cop, ⲓⲱⲁⲛⲛⲏⲥ or ⲓⲱ̅ⲁ) is the name traditionally given t ...

is claimed as a Gnostic by some Gnostic interpreters, as is even St. Paul. Most of the literature from this category is known to us through the Nag Hammadi Library.

Sethite-Barbeloite

Sethianism was one of the main currents of Gnosticism during the 2nd to 3rd centuries, and the prototype of Gnosticism as condemned by Irenaeus. Sethianism attributed its ''gnosis'' to Seth

Seth,; el, Σήθ ''Sḗth''; ; "placed", "appointed") in Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Mandaeism, and Sethianism, was the third son of Adam and Eve and brother of Cain and Abel, their only other child mentioned by name in the Hebrew Bible. ...

, third son of Adam and Eve

Adam and Eve, according to the creation myth of the Abrahamic religions, were the first man and woman. They are central to the belief that humanity is in essence a single family, with everyone descended from a single pair of original ancestors ...

and '' Norea'', wife of Noah

Noah ''Nukh''; am, ኖህ, ''Noḥ''; ar, نُوح '; grc, Νῶε ''Nôe'' () is the tenth and last of the pre-Flood patriarchs in the traditions of Abrahamic religions. His story appears in the Hebrew Bible (Book of Genesis, chapters 5� ...

, who also plays a role in Mandeanism and Manicheanism. Their main text is the ''Apocryphon of John'', which does not contain Christian elements, and is an amalgam of two earlier myths. Earlier texts such as Apocalypse of Adam show signs of being pre-Christian and focus on the Seth, third son of Adam and Eve. Later Sethian texts continue to interact with Platonism. Sethian texts such as Zostrianos and Allogenes draw on the imagery of older Sethian texts, but utilize "a large fund of philosophical conceptuality derived from contemporary Platonism, (that is, late middle Platonism) with no traces of Christian content."

According to John D. Turner, German and American scholarship views Sethianism as "a distinctly inner-Jewish, albeit syncretistic and heterodox, phenomenon", while British and French scholarship tends to see Sethianism as "a form of heterodox Christian speculation". Roelof vandenBroek notes that "Sethianism" may never have been a separate religious movement, and that the term refers rather to a set of mythological themes which occur in various texts.

According to Smith, Sethianism may have begun as a pre-Christian tradition, possibly a syncretic

Syncretism () is the practice of combining different beliefs and various schools of thought. Syncretism involves the merging or assimilation of several originally discrete traditions, especially in the theology and mythology of religion, thu ...

cult that incorporated elements of Christianity and Platonism as it grew. According to Temporini, Vogt, and Haase, early Sethians may be identical to or related to the Nazarenes (sect), the Ophites, or the sectarian group called heretics by Philo

Philo of Alexandria (; grc, Φίλων, Phílōn; he, יְדִידְיָה, Yəḏīḏyāh (Jedediah); ), also called Philo Judaeus, was a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher who lived in Alexandria, in the Roman province of Egypt.

Philo's dep ...

.

According to Turner, Sethianism was influenced by Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesu ...

and Middle Platonism

Middle Platonism is the modern name given to a stage in the development of Platonic philosophy, lasting from about 90 BC – when Antiochus of Ascalon rejected the scepticism of the new Academy – until the development of neoplatoni ...

, and originated in the second century as a fusion of a Jewish baptizing group of possibly priestly lineage, the so-called ''Barbeloites'', named after Barbelo, the first emanation of the Highest God, and a group of Biblical exegetes, the ''Sethites'', the "seed of Seth

Seth,; el, Σήθ ''Sḗth''; ; "placed", "appointed") in Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Mandaeism, and Sethianism, was the third son of Adam and Eve and brother of Cain and Abel, their only other child mentioned by name in the Hebrew Bible. ...

". At the end of the second century, Sethianism grew apart from the developing Christian orthodoxy, which rejected the docetian view of the Sethians on Christ. In the early third century, Sethianism was fully rejected by Christian heresiologists, as Sethianism shifted toward the contemplative practices of Platonism while losing interest in their primal origins. In the late third century, Sethianism was attacked by neo-Platonists like Plotinus

Plotinus (; grc-gre, Πλωτῖνος, ''Plōtînos''; – 270 CE) was a philosopher in the Hellenistic philosophy, Hellenistic tradition, born and raised in Roman Egypt. Plotinus is regarded by modern scholarship as the founder of Neop ...