Frederick II (1 July 1534 – 4 April 1588) was King of

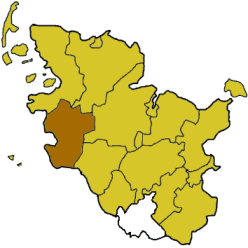

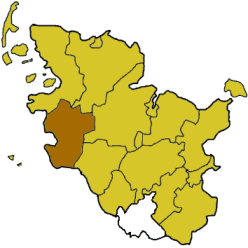

Denmark and Norway and Duke of

Schleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig ( da, Hertugdømmet Slesvig; german: Herzogtum Schleswig; nds, Hartogdom Sleswig; frr, Härtochduum Slaswik) was a duchy in Southern Jutland () covering the area between about 60 km (35 miles) north and 70 km ...

and

Holstein

Holstein (; nds, label=Northern Low Saxon, Holsteen; da, Holsten; Latin and historical en, Holsatia, italic=yes) is the region between the rivers Elbe and Eider. It is the southern half of Schleswig-Holstein, the northernmost state of German ...

from 1559 until his death.

A member of the

House of Oldenburg

The House of Oldenburg is a German dynasty with links to Denmark since the 15th century. It has branches that rule or have ruled in Denmark, Iceland, Greece, Norway, Russia, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Schleswig, Holstein, and Oldenburg. The cu ...

, Frederick began his personal rule of Denmark-Norway at the age of 24. He inherited a capable and strong kingdom, formed in large by

his father after the civil war known as the

Count's Feud

The Count's Feud ( da, Grevens Fejde), also called the Count's War, was a war of succession that raged in Denmark in 1534–36 and brought about the Reformation in Denmark. In the international context, it was part of the European wars of relig ...

, after which Denmark saw a period of economic recovery and of a great increase in the

centralised

Centralisation or centralization (see spelling differences) is the process by which the activities of an organisation, particularly those regarding planning and decision-making, framing strategy and policies become concentrated within a particu ...

authority of the Crown.

Frederick was, especially in his youth and unlike his father, belligerent and adversarial, aroused by honor and national pride, and so he began his reign auspiciously with a campaign under the aged

Johan Rantzau

Johan (also Johann) Rantzau (12 November 1492 – 12 December 1565) was a German- Danish general and statesman known for his role in the Count's Feud. His military leadership ensured the succession of Christian III to the throne, which bro ...

, which reconquered

Dithmarschen

Dithmarschen (, Low Saxon: ; archaic English: ''Ditmarsh''; da, Ditmarsken; la, label=Medieval Latin, Tedmarsgo) is a district in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. It is bounded by (from the north and clockwise) the districts of Nordfriesland, Schle ...

. However, after miscalculating the cost of the

Northern Seven Years' War

The Northern Seven Years' War (also known as the ''Nordic Seven Years' War'', the ''First Northern War'' or the ''Seven Years War in Scandinavia'') was fought between the Kingdom of Sweden (1523–1611), Kingdom of Sweden and a coalition of Denm ...

, he pursued a more prudent

foreign policy

A State (polity), state's foreign policy or external policy (as opposed to internal or domestic policy) is its objectives and activities in relation to its interactions with other states, unions, and other political entities, whether bilaterall ...

. The remainder of Frederick II's reign was a period of tranquillity, in which king and nobles prospered. Frederick spent more time hunting and feasting with his councillors, and focused on architecture and science. During his reign, many building projects were begun, including additions to the royal castles of

Kronborg

Kronborg is a castle and stronghold in the town of Helsingør, Denmark. Immortalized as Elsinore in William Shakespeare's play ''Hamlet'', Kronborg is one of the most important Renaissance castles in Northern Europe and was inscribed on the UNE ...

at

Elsinore and

Frederikborg Castle at

Hillerød

Hillerød () is a Denmark, Danish town with a population of 35,357 (1 January 2022)[Christian IV

Christian IV (12 April 1577 – 28 February 1648) was King of Denmark and Norway and Duke of Holstein and Schleswig from 1588 until his death in 1648. His reign of 59 years, 330 days is the longest of Danish monarchs and Scandinavian monar ...]

,

and often been portrayed with skepticism and resentment, resulting in the prevailing portrait of Frederick as a man and as king: an unlettered, inebriated, brutish sot.

[Lockhart, Paul D., page 36] This portrayal is, however, inequitable and inaccurate, and recent studies

[Thanks in large part to the research of historian Frede P. Jensen, who, after thorough archival studies, were able to provide a real and contemporary historical description of the King's character.] reappraise and acknowledge him as highly intelligent; he craved the company of

learned men, and in the correspondence and legislation he dictated to his secretaries he showed himself to be quick-witted and articulate.

Frederick was also open and loyal, and had a knack for establishing close personal bonds with fellow princes and with those who served him.

[''Grinder-Hansen, Poul, section 3-page 1'']

In 1572, Frederick

married his cousin Sophie of Mecklenburg. Their relationship is regarded as one of the happiest

royal marriages in

Renaissance Europe

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

. In the first ten years after the wedding, they had seven children, and are described as inseparable and harmonious.

Frederick was committed to becoming the mightiest king in

the North,

and for several years he fought

exhausting wars against his

archrival Erik XIV of Sweden

Eric XIV ( sv, Erik XIV; 13 December 153326 February 1577) was King of Sweden from 1560 until he was deposed in 1569. Eric XIV was the eldest son of Gustav I (1496–1560) and Catherine of Saxe-Lauenburg (1513–1535). He was also ruler of Es ...

, after which the battles changed character. It became a competition to see who could trace their

family history

Genealogy () is the study of families, family history, and the tracing of their Lineage (anthropology), lineages. Genealogists use oral interviews, historical records, genetic analysis, and other records to obtain information about a family a ...

the furthest, and who could construct the most formidable castles.

In the

1570s

The 1570s decade ran from January 1, 1570, to December 31, 1579.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:1570s

...

he constructed

Kronborg

Kronborg is a castle and stronghold in the town of Helsingør, Denmark. Immortalized as Elsinore in William Shakespeare's play ''Hamlet'', Kronborg is one of the most important Renaissance castles in Northern Europe and was inscribed on the UNE ...

, a large

Renaissance castle that became widely recognized abroad, and its

dance hall

Dance hall in its general meaning is a hall for dancing. From the earliest years of the twentieth century until the early 1960s, the dance hall was the popular forerunner of the discothèque or nightclub. The majority of towns and cities in ...

was the largest in

Northern Europe

The northern region of Europe has several definitions. A restrictive definition may describe Northern Europe as being roughly north of the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, which is about 54th parallel north, 54°N, or may be based on other g ...

at the time. He enjoyed entertaining guests and throwing elaborate festivities, which were well-known throughout Europe. During the same period, the

Danish-Norwegian fleet was developed into one of Europe's largest and most modern. As part of his efforts to strengthen the kingdoms, he provided much support for

science

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence for ...

and

culture

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups.Tyl ...

.

Early years and education

Frederick was born on 1 July 1534 at

Haderslevhus Castle

Haderslevhus (or Hansborg) is the name of a castle that once stood in the Danish city of Haderslev, until destroyed by a fire in 1644.

History

Like most of the medieval cities of trade, Haderslev had a royal castle, which was called Haderslevh ...

, the son of Duke Christian of

Schleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig ( da, Hertugdømmet Slesvig; german: Herzogtum Schleswig; nds, Hartogdom Sleswig; frr, Härtochduum Slaswik) was a duchy in Southern Jutland () covering the area between about 60 km (35 miles) north and 70 km ...

and

Holstein

Holstein (; nds, label=Northern Low Saxon, Holsteen; da, Holsten; Latin and historical en, Holsatia, italic=yes) is the region between the rivers Elbe and Eider. It is the southern half of Schleswig-Holstein, the northernmost state of German ...

(later King

Christian III of Denmark and Norway) and

Dorothea of Saxe-Lauenburg

Dorothea of Saxe-Lauenburg (9 July 1511 – 7 October 1571) was queen consort of Denmark and Norway by marriage to King Christian III of Denmark. She was known to having wielded influence upon the affairs of state in Denmark.Jorgensen, Ellen & Sk ...

, the daughter of

Magnus I, Duke of Saxe-Lauenburg

Magnus I of Saxe-Lauenburg (1 January 1470 – 1 August 1543) was a Duke of Saxe-Lauenburg from the House of Ascania.

Life

Magnus was born in Ratzeburg, the second son of John V, Duke of Saxe-Lauenburg and Dorothea of Brandenburg, daughter of F ...

. His mother was the sister of

Catherine

Katherine, also spelled Catherine, and other variations are feminine names. They are popular in Christian countries because of their derivation from the name of one of the first Christian saints, Catherine of Alexandria.

In the early Christ ...

, the first wife of the

Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

king

Gustav Vasa

Gustav I, born Gustav Eriksson of the Vasa noble family and later known as Gustav Vasa (12 May 1496 – 29 September 1560), was King of Sweden from 1523 until his death in 1560, previously self-recognised Protector of the Realm ('' Riksför ...

, and the mother of

Eric XIV

Eric XIV ( sv, Erik XIV; 13 December 153326 February 1577) was King of Sweden from 1560 until he was deposed in 1569. Eric XIV was the eldest son of Gustav I (1496–1560) and Catherine of Saxe-Lauenburg (1513–1535). He was also ruler of Es ...

, his future rival.

At the time of Frederick's birth,

a civil war of Denmark was coming to an end (just three days after Frederick's birth his father

Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

became King of Denmark). The previous king,

Frederick I Frederick I may refer to:

* Frederick of Utrecht or Frederick I (815/16–834/38), Bishop of Utrecht.

* Frederick I, Duke of Upper Lorraine (942–978)

* Frederick I, Duke of Swabia (1050–1105)

* Frederick I, Count of Zoll ...

, died on 10 April the year before, but the Danish

Council of the Realm

The Council of the Realm ( es, Consejo del Reino) was a corporate organ of Francoist Spain, created by the Law of Succession to the Headship of the State of 1947. Within the institutional complex created to hierarchize the regime of Francisco Fran ...

, which traditionally ruled the kingdom with the king, had not chosen a successor, and now Denmark had, for more than a year, functioned as an

Aristocratic

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At the time of the word's ...

Republic.

The father of the newborn Frederik, Christian, although eldest son of the late king, was not automatically King of Denmark, as the kingship in Denmark was not

hereditary

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic inform ...

, but

elective. Noblemen of the

Council of the Realm

The Council of the Realm ( es, Consejo del Reino) was a corporate organ of Francoist Spain, created by the Law of Succession to the Headship of the State of 1947. Within the institutional complex created to hierarchize the regime of Francisco Fran ...

could choose to pick another member of the royal family as king if they so decided.

Frederick I Frederick I may refer to:

* Frederick of Utrecht or Frederick I (815/16–834/38), Bishop of Utrecht.

* Frederick I, Duke of Upper Lorraine (942–978)

* Frederick I, Duke of Swabia (1050–1105)

* Frederick I, Count of Zoll ...

and his son Christian were staunch

Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

and adherents to the

Lutheran cause, however, in the

Council of the Realm

The Council of the Realm ( es, Consejo del Reino) was a corporate organ of Francoist Spain, created by the Law of Succession to the Headship of the State of 1947. Within the institutional complex created to hierarchize the regime of Francisco Fran ...

, which consisted of many

Catholic bishops

In the Catholic Church, a bishop is an ordained minister who holds the fullness of the sacrament of holy orders and is responsible for teaching doctrine, governing Catholics in his jurisdiction, sanctifying the world and representing the Ch ...

as well as a number of powerful noblemen from the old nobility, there were a majority to support the established

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. After a period of

interregnum and after subsequent risings in favour of the former

King Christian II, a period known as

the Count's Feud,

Christian III

Christian III (12 August 1503 – 1 January 1559) reigned as King of Denmark from 1534 and King of Norway from 1537 until his death in 1559. During his reign, Christian formed close ties between the church and the crown. He established ...

finally became victorious, and was proclaimed King of a new Protestant Denmark.

Proclaimed heir apparent

After

King Christian III's victory in the

Count's Feud

The Count's Feud ( da, Grevens Fejde), also called the Count's War, was a war of succession that raged in Denmark in 1534–36 and brought about the Reformation in Denmark. In the international context, it was part of the European wars of relig ...

, royal power had now returned to Denmark, and in such a way that the king could set his own terms.

[Lockhart, Paul D., page 28] In his ''

haandfæstning

A Haandfæstning ( Modern da, Håndfæstning & Modern no, Håndfestning, lit. "Handbinding", plural ''Haandfæstninger'') was a document issued by the kings of Denmark from 13th to the 17th century, preceding and during the realm's personal un ...

'', a document which all former Danish Kings must sign, and which regulates the relationship between king and

nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy (class), aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below Royal family, royalty. Nobility has often been an Estates of the realm, estate of the realm with many e ...

, he reduced the nobility's power, and established that the first son of the king should always be seen as

heir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

, and succeed his father automatically.

[''Grinder-Hansen, Poul, section 3-page 9'']

On 30 October 1536 Christian convened the

estates of the realm

The estates of the realm, or three estates, were the broad orders of social hierarchy used in Christendom (Christian Europe) from the Middle Ages to early modern Europe. Different systems for dividing society members into estates developed an ...

(''Rigsdag'') to

Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan ar ...

, were they formally proclaimed Frederick

heir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

and successor to the throne, granting him the title "Prince of Denmark".

In 1542, the Prince travelled around Denmark and was hailed by the people. In the Midsummer of 1548 Christian III and his son Frederick, in a fleet of 7 ships and together with 30 Danish nobles, sailed for

Oslo

Oslo ( , , or ; sma, Oslove) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population of ...

, were Frederick was hailed as heir apparent to the

Throne

A throne is the seat of state of a potentate or dignitary, especially the seat occupied by a sovereign on state occasions; or the seat occupied by a pope or bishop on ceremonial occasions. "Throne" in an abstract sense can also refer to the mona ...

of the

Kingdom of Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the ...

. The royal reception included Danish nobles holding fiefs in

Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

, received by Prince Frederik on his ship. The entire Norwegian nobility had been summoned to Oslo.

Upbringing

While

Christian III

Christian III (12 August 1503 – 1 January 1559) reigned as King of Denmark from 1534 and King of Norway from 1537 until his death in 1559. During his reign, Christian formed close ties between the church and the crown. He established ...

secured control of Denmark and Norway, his and

Dorothea's children grew up in the bosom of the family. In addition to

Anna

Anna may refer to:

People Surname and given name

* Anna (name)

Mononym

* Anna the Prophetess, in the Gospel of Luke

* Anna (wife of Artabasdos) (fl. 715–773)

* Anna (daughter of Boris I) (9th–10th century)

* Anna (Anisia) (fl. 1218 to 12 ...

, who was born in 1532, and Frederik from 1534, the group of siblings consisted of

Magnus

Magnus, meaning "Great" in Latin, was used as cognomen of Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus in the first century BC. The best-known use of the name during the Roman Empire is for the fourth-century Western Roman Emperor Magnus Maximus. The name gained wid ...

, born 1540, and

John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

, who was born in 1545 and called

John the Younger, to distinguish him from Christian III's half-brother,

John the Elder

John the Presbyter was an obscure figure of the early Church who is either distinguished from or identified with the Apostle John and/or John of Patmos. He appears in fragments from the church father Papias of Hierapolis as one of the author's ...

. Youngest was

a girl

A, or a, is the first letter and the first vowel of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''a'' (pronounced ), plural ''aes' ...

who was born in 1546 and named after her mother.

It was the usual pedagogical view of the time that parents were so inclined to spoil their own children that the upbringing of the children should be delegated to other members of the family,

[''Grinder-Hansen, Poul, section 4-page 1''] typically the child's maternal grandparents. But

Queen Dorothea didn't want to send the children away when in

infancy. Moreover,

her own mother was suspected of nurturing Catholic sympathies, and in the religious era, a Lutheran Danish king could not in good conscience expose his child to Catholic influences. Another contributing factor has probably been the royal couple's concern by leaving the children too much out of sight in the tense political situation that prevailed in the first ten years of Frederik's life.

Education

Frederik's education, although profound and thorough, was focused on the

ecclesiastical and

lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

doctrine, Frederick mainly learning instructions in theology.

[Lockhart, Paul D., page 35] While a princely educational program, which included learning the art of

stewardship, diplomacy and war, was proposed and planned by the Danish Chancellor, it was not executed in full as the Danish Chancellor's relationship with

Christian III

Christian III (12 August 1503 – 1 January 1559) reigned as King of Denmark from 1534 and King of Norway from 1537 until his death in 1559. During his reign, Christian formed close ties between the church and the crown. He established ...

deteriorated before the education could begin.

[''Grinder-Hansen, Poul, section 4-page 2'']

Life at the court of

Christian III

Christian III (12 August 1503 – 1 January 1559) reigned as King of Denmark from 1534 and King of Norway from 1537 until his death in 1559. During his reign, Christian formed close ties between the church and the crown. He established ...

and

Dorothea

Dorothea (also spelled Dorothée, Dorotea or other variants) is a female given name from Greek (Dōrothéa) meaning "God's Gift". It may refer to:

People

* Dorothea Binz (1920–1947), German concentration camp officer executed for war cr ...

was imbued with a fervent

Lutheran Christianity

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

with which all their children naturally grew up. In March 1538

Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

Wolfgang von Utenhof proposed an educational program for the young Prince Frederick. He was to have a Danish

court steward, but he also had to work with and be inspected daily by a

chamberlain

Chamberlain may refer to:

Profession

*Chamberlain (office), the officer in charge of managing the household of a sovereign or other noble figure

People

*Chamberlain (surname)

**Houston Stewart Chamberlain (1855–1927), German-British philosop ...

, who was to be a reliable and sobering man from the

Holstein

Holstein (; nds, label=Northern Low Saxon, Holsteen; da, Holsten; Latin and historical en, Holsatia, italic=yes) is the region between the rivers Elbe and Eider. It is the southern half of Schleswig-Holstein, the northernmost state of German ...

nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy (class), aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below Royal family, royalty. Nobility has often been an Estates of the realm, estate of the realm with many e ...

. The prince had to learn

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, German,

Danish

Danish may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Denmark

People

* A national or citizen of Denmark, also called a "Dane," see Demographics of Denmark

* Culture of Denmark

* Danish people or Danes, people with a Danish a ...

, French and other languages, and when he got older he had to learn

fencing

Fencing is a group of three related combat sports. The three disciplines in modern fencing are the foil, the épée, and the sabre (also ''saber''); winning points are made through the weapon's contact with an opponent. A fourth discipline, ...

and other chivalry exercises. He was to have 10–15 young men for company both in his studies and in his chivalrous exercises.

To which extent this educational program was followed is not known. In 1541, Frederick aged 7, he began his schooling. Frederick was appointed

Hans Svenning, a reputed Danish

humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

and professor of

rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate parti ...

at

University of Copenhagen

The University of Copenhagen ( da, Københavns Universitet, KU) is a prestigious public university, public research university in Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark. Founded in 1479, the University of Copenhagen is the second-oldest university in ...

, as teacher.

Dyslexia

Christian III

Christian III (12 August 1503 – 1 January 1559) reigned as King of Denmark from 1534 and King of Norway from 1537 until his death in 1559. During his reign, Christian formed close ties between the church and the crown. He established ...

and

Dorothea

Dorothea (also spelled Dorothée, Dorotea or other variants) is a female given name from Greek (Dōrothéa) meaning "God's Gift". It may refer to:

People

* Dorothea Binz (1920–1947), German concentration camp officer executed for war cr ...

had probably been expecting a lot from Frederick's schooling.

[''Grinder-Hansen, Poul, section 4-page 3''] The son was obviously bright and had a good memory. So much bigger has the disappointment, and the amazement, been when the teaching started. Frederick learned to write beautiful and clear letters, but when it came to reading and spelling, the royal student was "a disaster".

For

Hans Svaning

Hans Svaning (1503 – 20 September 1584) was a Danish historian. Biography

Svaning was born at the village of Svaninge on Funen.

He attended Vor Frue skole in Copenhagen and the University of Wittenberg graduating in 1529 and in 1533 receiving ...

, this deranged spelling of Frederick's could only be seen as sloppy and laziness, given that the royal boy otherwise seemed smart enough.

[''Grinder-Hansen, Poul, section 4-page 4''] Time and time again, Frederick has been punished, probably not only by the teacher, but also by his strict mother, who would gladly step in if Svaning's teaching was not sufficient.

Because of Frederick's heavy

dyslexia, he was perceived by his contemporaries as unlettered and illiterate. Both Frederick's father and mother looked with skepticism at the heir to the throne, and they kept him under the watchful eye of knowledgeable men as far as possible to prevent him from publicly speaking out. Neither did his father entrust Frederik with any administrative duties.

Malmøhus

It was only at the age of 20 in 1554 that Frederik was allowed to hold his own court at

Malmö Castle

Malmö Castle ( sv, Malmöhus, da, Malmøhus) is a fortress located in Malmö, Scania, Sweden.

It is owned by the Swedish state and is managed by the State Property Agency. Malmöhus is part of Malmö Museums.

History

The first castle was ...

in

Scania

Scania, also known by its native name of Skåne (, ), is the southernmost of the historical provinces of Sweden, provinces (''landskap'') of Sweden. Located in the south tip of the geographical region of Götaland, the province is roughly conte ...

, but under the supervision of the middle-aged lensman ('

Fief

A fief (; la, feudum) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an Lord, overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a for ...

-man')

Ejler Hardenberg, who was appointed the prince's court master. At the same time, political training began, which was put in the hands of the two driven noblemen

Eiler Rønnow and Erik Rosenkrantz.

[''Grinder-Hansen, Poul, section 4-page 5''] The years in

Scania

Scania, also known by its native name of Skåne (, ), is the southernmost of the historical provinces of Sweden, provinces (''landskap'') of Sweden. Located in the south tip of the geographical region of Götaland, the province is roughly conte ...

, must have felt like a liberation for Frederick.

He had finally escaped from the royal court with its tightly regulated existences and pious daily lives. Just outside the moats around

Malmö Castle

Malmö Castle ( sv, Malmöhus, da, Malmøhus) is a fortress located in Malmö, Scania, Sweden.

It is owned by the Swedish state and is managed by the State Property Agency. Malmöhus is part of Malmö Museums.

History

The first castle was ...

was the lively trading town of

Malmö

Malmö (, ; da, Malmø ) is the largest city in the Swedish county (län) of Scania (Skåne). It is the third-largest city in Sweden, after Stockholm and Gothenburg, and the sixth-largest city in the Nordic region, with a municipal populat ...

, which offered a young man all-out experiences.

While spending many of his youth years in

Scania

Scania, also known by its native name of Skåne (, ), is the southernmost of the historical provinces of Sweden, provinces (''landskap'') of Sweden. Located in the south tip of the geographical region of Götaland, the province is roughly conte ...

, he became known as the "

Prince

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. Th ...

of Scania" (''princeps Scaniæ'') ().

It is not known whether this title was ever officially decreed to him.

Travels to Germany with his brother-in-law

The only political education that Frederik received came from his close friendship with his brother-in-law,

Elector Augustus of Saxony (reigned 1553–86). Some authors have later stated that Augustus was "the only strong emotional support" Frederick received in his youth.

Augustus, who was the husband of Frederik's elder sister

Anne

Anne, alternatively spelled Ann, is a form of the Latin female given name Anna. This in turn is a representation of the Hebrew Hannah, which means 'favour' or 'grace'. Related names include Annie.

Anne is sometimes used as a male name in the ...

, took Frederik under his wing, chaperoning him on a trip throughout the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

in 1557–58. Here Frederik made the acquaintance of the new emperor,

Ferdinand I (reigned 1558–64) at his

coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a coronation crown, crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the ...

, his son and heir apparent

Maximilian

Maximilian, Maximillian or Maximiliaan (Maximilien in French) is a male given name.

The name " Max" is considered a shortening of "Maximilian" as well as of several other names.

List of people

Monarchs

*Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor (1459� ...

(emperor 1564–76),

William of Orange, and a host of other more prominent German Protestant princes. The experience nurtured in Frederik a lasting appreciation of the great complexity of German politics and a taste for all things military.

This was most troubling to Frederick's father, the ageing

Christian III

Christian III (12 August 1503 – 1 January 1559) reigned as King of Denmark from 1534 and King of Norway from 1537 until his death in 1559. During his reign, Christian formed close ties between the church and the crown. He established ...

, who feared that in the Empire Frederick would develop ambitions that would exceed both his abilities and the resources of his kingdoms, and that the trip would ultimately drag Denmark-Norway into the maelstrom of German princely politics.

Peder Oxe

In 1552, Steward of the Realm,

Peder Oxe

Peter is a common masculine given name. It is derived directly from Greek , ''Petros'' (an invented, masculine form of Greek ''petra,'' the word for "rock" or "stone"), which itself was a translation of Aramaic ''Kefa'' ("stone, rock"), the new na ...

(1520–1575), had been raised to Councillor of State (''Rigsraad''). During the spring of 1557, Oxe and

the King had quarreled over a mutual property exchange. Failing to compromise matters with the King, Oxe had fled to Germany in 1558.

Reign

Proclaimed King

Frederick's father

Christian III

Christian III (12 August 1503 – 1 January 1559) reigned as King of Denmark from 1534 and King of Norway from 1537 until his death in 1559. During his reign, Christian formed close ties between the church and the crown. He established ...

died on 1 January 1559 at

Koldinghus

Koldinghus is a Danish royal castle in the town of Kolding on the south central part of the Jutland peninsula. The castle was founded in the 13th century and was expanded since with many functions ranging from fortress, royal residency, ruin, mus ...

. Frederick was not present at his father's bedside when he died, a circumstance that did not endear the new king, now King Frederick II of Denmark-Norway, to the councillors who had grown to appreciate and revere Christian.

On 12 August 1559 Frederick signed his

haandfæstning

A Haandfæstning ( Modern da, Håndfæstning & Modern no, Håndfestning, lit. "Handbinding", plural ''Haandfæstninger'') was a document issued by the kings of Denmark from 13th to the 17th century, preceding and during the realm's personal un ...

(lit. "Handbinding" viz. curtailment of the monarch's power, a Danish parallel to the

Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called (also ''Magna Charta''; "Great Charter"), is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by the ...

) and on 20 August 1559 Frederick II was

crowned at the

Church of Our Lady in Copenhagen by a Danish

superintendent

Superintendent may refer to:

*Superintendent (police), Superintendent of Police (SP), or Senior Superintendent of Police (SSP), a police rank

*Prison warden or Superintendent, a prison administrator

*Superintendent (ecclesiastical), a church exec ...

, with

Nicolaus Palladius and

Jens Skielderup two Norwegian

superintendent

Superintendent may refer to:

*Superintendent (police), Superintendent of Police (SP), or Senior Superintendent of Police (SSP), a police rank

*Prison warden or Superintendent, a prison administrator

*Superintendent (ecclesiastical), a church exec ...

assisting, symbolizing the relationship between the kingdoms of

Denmark and Norway. Week-long and elaborate celebrations are said to have taken place after the coronation.

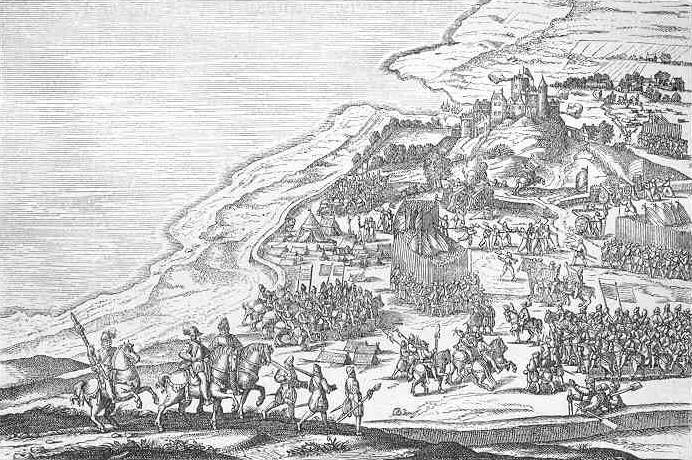

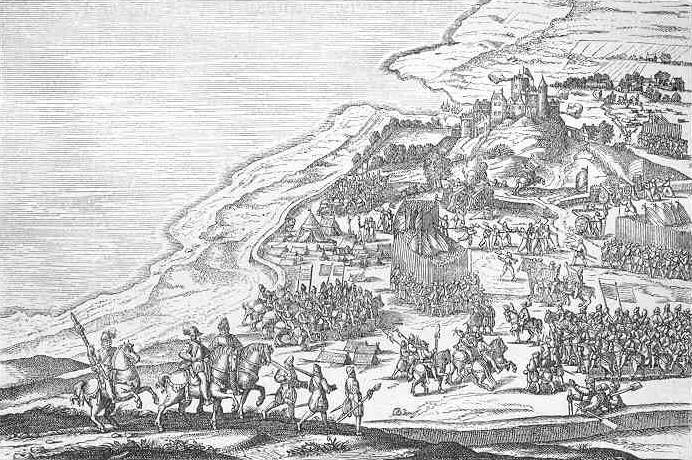

Conquest of Ditmarschen

Within weeks of Christian's passing, Frederick joined with his uncles in

Holstein

Holstein (; nds, label=Northern Low Saxon, Holsteen; da, Holsten; Latin and historical en, Holsatia, italic=yes) is the region between the rivers Elbe and Eider. It is the southern half of Schleswig-Holstein, the northernmost state of German ...

,

John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

and

Adolf

Adolf (also spelt Adolph or Adolphe, Adolfo and when Latinised Adolphus) is a given name used in German-speaking countries, Scandinavia, the Netherlands and Flanders, France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Latin America and to a lesser extent in vari ...

, in a

military campaign

A military campaign is large-scale long-duration significant military strategy plan incorporating a series of interrelated military operations or battles forming a distinct part of a larger conflict often called a war. The term derives from the ...

to conquer the

Ditmarschen, under

Johan Rantzau

Johan (also Johann) Rantzau (12 November 1492 – 12 December 1565) was a German- Danish general and statesman known for his role in the Count's Feud. His military leadership ensured the succession of Christian III to the throne, which bro ...

. Frederik II's

great-uncle

An uncle is usually defined as a male relative who is a sibling of a parent or married to a sibling of a parent. Uncles who are related by birth are second-degree relatives. The female counterpart of an uncle is an aunt, and the reciprocal rela ...

,

King John, had failed to subjugate the peasant republic in 1500, but the Frederick's 1559-campaign was a quick and relatively painless victory for the Danish Kingdom. The brevity and low cost of the campaign were cold comforts to the members of the

Council of the Realm

The Council of the Realm ( es, Consejo del Reino) was a corporate organ of Francoist Spain, created by the Law of Succession to the Headship of the State of 1947. Within the institutional complex created to hierarchize the regime of Francisco Fran ...

,

Johan Friis

Johan Friis (20 February 1494 – 5 December 1570) was a Danish statesman. He served as Chancellor under King Christian III of Denmark.

Biography

He was born at Lundbygård manor as the son of Jesper Friis til Lundbygård and Anne Johansda ...

in particular. Friis had warned Frederick that a very real threat of conflict with Sweden loomed just over the horizon, but the king had not listened, and had not even consulted with the Council about the Ditmarschen.

Early relationship with the Council of the Realm

The adversarial king–Council relationship improved relatively quickly however, and not because Frederik caved in to conciliar opposition. Rather, the two parties quickly learned to work together because their interests, and the Kingdom's, required that they did so. From an early time, the council invested much power in Frederick, as they had no desire to go back to the destructive near-anarchy of the pre-civil war years.

Frederik would soon learn how to play the constitutional game, that is required in a consensual monarchy, such as Denmark; namely to humour the Council without sacrificing his own royal interests. This meant showing generosity to the conciliar

aristocracy

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At t ...

through various gifts and concessions, which he did in grand style. Shortly before the signing of his coronation charter (''

haandfæstning

A Haandfæstning ( Modern da, Håndfæstning & Modern no, Håndfestning, lit. "Handbinding", plural ''Haandfæstninger'') was a document issued by the kings of Denmark from 13th to the 17th century, preceding and during the realm's personal un ...

''),

Andreas von Barby, leader of the German Chancery, died. Barby was not well liked in the Council of the Realm, but he was extreamly wealthy. The extensive

fief

A fief (; la, feudum) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an Lord, overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a for ...

s in his possession reverted to the Crown, and Frederik was careful to distribute out these properties among the leading members of the Council of the Realm. Throughout his reign, Frederik would reward his conciliar aristocracy generously. Fiefs were distributed on highly favourable terms.

The substantially warmer relationship between king and Council of the Realm after the

Ditmarschen campaign is best illustrated by the Danish central administration's performance in the greatest national crisis of the reign, the

Northern Seven Years' War

The Northern Seven Years' War (also known as the ''Nordic Seven Years' War'', the ''First Northern War'' or the ''Seven Years War in Scandinavia'') was fought between the Kingdom of Sweden (1523–1611), Kingdom of Sweden and a coalition of Denm ...

(1563–70) against Sweden.

Relationship with Livonia

From his predecessor, Frederick inherited the

Livonian War

The Livonian War (1558–1583) was the Russian invasion of Old Livonia, and the prolonged series of military conflicts that followed, in which Tsar Ivan the Terrible of Russia (Muscovy) unsuccessfully fought for control of the region (pre ...

. In 1560, he installed his younger brother,

Magnus of Holstein

Magnus of Denmark or Magnus of Holstein ( – ) was a Prince of Denmark, Duke of Holstein, and a member of the House of Oldenburg. As a vassal of Tsar Ivan IV of Russia, he was the titular King of Livonia from 1570 to 1578.

Early life

Duke Magnu ...

(1540–1583), in the

Bishopric of Ösel–Wiek

The Bishopric of Ösel–Wiek ( et, Saare-Lääne piiskopkond; german: Bistum Ösel–Wiek; Low German: ''Bisdom Ösel–Wiek''; contemporary la, Ecclesia Osiliensis) was a Roman Catholic diocese and semi-independent prince-bishopric (part of ...

. King Frederick II largely tried to avoid conflict in

Livonia

Livonia ( liv, Līvõmō, et, Liivimaa, fi, Liivinmaa, German and Scandinavian languages: ', archaic German: ''Liefland'', nl, Lijfland, Latvian and lt, Livonija, pl, Inflanty, archaic English: ''Livland'', ''Liwlandia''; russian: Ли ...

and consolidated amicable relations with Tsar

Ivan IV of Russia

Ivan IV Vasilyevich (russian: Ива́н Васи́льевич; 25 August 1530 – ), commonly known in English as Ivan the Terrible, was the grand prince of Moscow from 1533 to 1547 and the first Tsar of all Russia from 1547 to 1584.

Iva ...

in the 1562

Treaty of Mozhaysk

The Treaty of Mozhaysk (also Moshaisk or other transliterations of Можайск) was a Danish-Russian treaty concluded on 7 August 1562, during the Livonian War. While not an actual alliance, the treaty confirmed the amicable Dano-Russian relat ...

. His brother Magnus was later made titular King of Livonia, as a vassal of Tsar Ivan IV.

Northern Seven Years' War

King Frederick's competition with Sweden for supremacy in the

Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

* Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originati ...

broke out into open warfare in 1563, the start of the

Northern Seven Years' War

The Northern Seven Years' War (also known as the ''Nordic Seven Years' War'', the ''First Northern War'' or the ''Seven Years War in Scandinavia'') was fought between the Kingdom of Sweden (1523–1611), Kingdom of Sweden and a coalition of Denm ...

, the dominating conflict of his rule.

The leading councillors,

Johan Friis

Johan Friis (20 February 1494 – 5 December 1570) was a Danish statesman. He served as Chancellor under King Christian III of Denmark.

Biography

He was born at Lundbygård manor as the son of Jesper Friis til Lundbygård and Anne Johansda ...

foremost among them, had feared a Swedish onslaught for several years, and after the succession of Frederick II's first cousin, the ambitious and unbalanced

Eric XIV

Eric XIV ( sv, Erik XIV; 13 December 153326 February 1577) was King of Sweden from 1560 until he was deposed in 1569. Eric XIV was the eldest son of Gustav I (1496–1560) and Catherine of Saxe-Lauenburg (1513–1535). He was also ruler of Es ...

(reigned 1560–1568) to the

Vasa throne a confrontation appeared inevitable. Still, few councillors wanted war, and they preferred to wait until it was forced upon them, while Frederik preferred a

preemptive strike

A preemptive war is a war that is commenced in an attempt to repel or defeat a perceived imminent offensive or invasion, or to gain a strategic advantage in an impending (allegedly unavoidable) war ''shortly before'' that attack materializes. It ...

. Despite its initial opposition to the war, the

Council of the Realm

The Council of the Realm ( es, Consejo del Reino) was a corporate organ of Francoist Spain, created by the Law of Succession to the Headship of the State of 1947. Within the institutional complex created to hierarchize the regime of Francisco Fran ...

went along with the king. Frederik II, wisely, made no effort to exclude the council from the direction of the war, and though he retained chief operational control he entrusted much responsibility to his councillors, including Holger Ottesen

Rosenkrants,

Marshal

Marshal is a term used in several official titles in various branches of society. As marshals became trusted members of the courts of Medieval Europe, the title grew in reputation. During the last few centuries, it has been used for elevated o ...

Otte Krumpen, and

Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

Herluf Trolle

Herluf Trolle (14 January 1516 – 25 June 1565) was a Danish naval hero, Admiral of the Fleet and co-founder of Herlufsholm School (''Herlufsholm Skole og Gods''), a private boarding school at Næstved on the island of Zealand in Denmark.

...

.

[Lockhart, Paul D., page 39]

Only one constitutional crisis emerged during

the war; in late 1569, after six years of war, the Council decided not to provide the king with further grants of taxation. The war had been costly, both in lives and in gold, but since 1565 Denmark had made no appreciable gains. The council had already asked Frederik to make peace, and he had made a half-hearted attempt to do so in 1568, but neither Frederik nor his

Swedish opponent was willing to concede defeat.

The war developed into an extremely expensive

war of attrition

The War of Attrition ( ar, حرب الاستنزاف, Ḥarb al-Istinzāf; he, מלחמת ההתשה, Milhemet haHatashah) involved fighting between Israel and Egypt, Jordan, the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and their allies from ...

in which the areas of

Scania

Scania, also known by its native name of Skåne (, ), is the southernmost of the historical provinces of Sweden, provinces (''landskap'') of Sweden. Located in the south tip of the geographical region of Götaland, the province is roughly conte ...

were ravaged by the Swedes, and

Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

was almost lost. During this war, King Frederick II led his army personally on the battlefield, but although with some small success, overall without much result.

The council, in cutting off financial support, had hoped to coerce the king into ending the war. Frederik felt betrayed, and after some reflection, Frederick felt that the only honourable recourse was

abdication

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of duty, in other societ ...

.

With his

letter of resignation

A letter of resignation is written to announce the author's intent to leave a position currently held, such as an office, employment or commission.

Historical

A formal letter with minimal expression of courtesy is then-President Richard Nixon' ...

in the hands of the councillors, he left

the capital

''The Capital'' (also known as ''Capital Gazette'' as its online nameplate and informally), the Sunday edition is called ''The Sunday Capital'', is a daily newspaper published by Capital Gazette Communications in Annapolis, Maryland, to serve ...

to go hunting in the

countryside

In general, a rural area or a countryside is a geographic area that is located outside towns and cities. Typical rural areas have a low population density and small settlements. Agricultural areas and areas with forestry typically are descri ...

. The king, still unmarried, had no heir, and consequently the

Council of the Realm

The Council of the Realm ( es, Consejo del Reino) was a corporate organ of Francoist Spain, created by the Law of Succession to the Headship of the State of 1947. Within the institutional complex created to hierarchize the regime of Francisco Fran ...

had good reason to fear another leaderless

interregnum and even another civil war. It played into the king's hands; the Council begging for his return to the throne and allowed him to summon a

Diet

Diet may refer to:

Food

* Diet (nutrition), the sum of the food consumed by an organism or group

* Dieting, the deliberate selection of food to control body weight or nutrient intake

** Diet food, foods that aid in creating a diet for weight loss ...

to consider additional

tax levies

A tax levy under United States federal law is an administrative action by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) under statutory authority, generally without going to court, to seize property to satisfy a tax liability. The levy "includes the power ...

.

The conflict damaged his relationship with his noble councillors; however, the later

Sture murders of 24 May 1567 by the insane King Eric XIV in Sweden, eventually helped stabilize the situation in

Denmark-Norway. After King

John III of Sweden, King Eric's successor, refused to accept a peace favoring Denmark-Norway in the

Treaties of Roskilde (1568)

The Treaties of Roskilde of 18 and 22 November 1568 were peace treaties between the kingdoms of Denmark–Norway and the allied Free and Hanseatic City of Lübeck on one side, and the Swedish kingdom on the other side, supposed to end the No ...

, the ongoing war dragged on until it was ended by a status quo peace in the

Treaty of Stettin (1570)

The Treaty of Stettin (german: Frieden von Stettin, sv, Freden i Stettin, da, Freden i Stettin) of 13 December 1570, ended the Northern Seven Years' War fought between Sweden and Denmark with its internally fragmented alliance of Lübeck and Pol ...

, that let Denmark-Norway save face but also show limits of Danish and Norwegian military power.

Frederik II learned a great deal about kingship during the war with Sweden. He learned to include the

Council of the Realm

The Council of the Realm ( es, Consejo del Reino) was a corporate organ of Francoist Spain, created by the Law of Succession to the Headship of the State of 1947. Within the institutional complex created to hierarchize the regime of Francisco Fran ...

in most matters of policy, but he also learned that it was possible to manipulate the council, even to bend it to his own will, without humiliating it or undermining its authority.

He would later come to master this ability and use it extensively.

Later reign

During the eighteen remaining years of his reign, Frederik would come to drew extensively on the lessons he learned in the

Northern Seven Years' War

The Northern Seven Years' War (also known as the ''Nordic Seven Years' War'', the ''First Northern War'' or the ''Seven Years War in Scandinavia'') was fought between the Kingdom of Sweden (1523–1611), Kingdom of Sweden and a coalition of Denm ...

with

Eric XIV of Sweden

Eric XIV ( sv, Erik XIV; 13 December 153326 February 1577) was King of Sweden from 1560 until he was deposed in 1569. Eric XIV was the eldest son of Gustav I (1496–1560) and Catherine of Saxe-Lauenburg (1513–1535). He was also ruler of Est ...

. In the peacetime years, he maintained a rather peripatetic court, moving from residence to residence throughout the Danish countryside, spending a fair share of his time in

hunting

Hunting is the human activity, human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, or killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to harvest food (i.e. meat) and useful animal products (fur/hide (skin), hide, ...

. This allowed him the opportunity to meet members of the

Council individually and informally, in their home regions. As was required of the Danish King, he did summon the

Council of the Realm

The Council of the Realm ( es, Consejo del Reino) was a corporate organ of Francoist Spain, created by the Law of Succession to the Headship of the State of 1947. Within the institutional complex created to hierarchize the regime of Francisco Fran ...

once annually to meet at the ''herredag'', but most of his business with the council was done on a one-to-one basis.

[Lockhart, Paul D., page 40] This ensured a very close personal bond with each member of the council while minimizing the opportunity for the council to oppose him as a full body. Frederik's personable disposition also helped,

and so, too, did the informal nature of court life under Frederik II. The king

hunted,

feasted, and drank with his noble

councillor

A councillor is an elected representative for a local government council in some countries.

Canada

Due to the control that the provinces have over their municipal governments, terms that councillors serve vary from province to province. Unl ...

s and

adviser

An adviser or advisor is normally a person with more and deeper knowledge in a specific area and usually also includes persons with cross-functional and multidisciplinary expertise. An adviser's role is that of a mentor or guide and differs categor ...

s, and even with visiting

foreign dignitaries, treating them as his equal peers and companions rather than as political opponents or inferiors. The eighteenth-century chronicler

Ludvig Holberg

Ludvig Holberg, Baron of Holberg (3 December 1684 – 28 January 1754) was a writer, essayist, philosopher, historian and playwright born in Bergen, Norway, during the time of the Dano-Norwegian dual monarchy. He was influenced by Humanism, ...

claimed that when dining at his court, Frederik would frequently announce that ‘the king is not at home’, which signalled to his guests that all court

formalities were temporarily suspended, and that they could talk and joke as they pleased without restraint. The Danish court of Frederick II may have appeared to be unsophisticated to outside observers, but the openness and bawdiness of court life served Frederik's political purposes.

In 1585, he visited Norway for the first and only time as king, but only went to

Bohuslen.

Financial situation

The great cost of the

Northern Seven Years' War

The Northern Seven Years' War (also known as the ''Nordic Seven Years' War'', the ''First Northern War'' or the ''Seven Years War in Scandinavia'') was fought between the Kingdom of Sweden (1523–1611), Kingdom of Sweden and a coalition of Denm ...

, some 1.1 million

rigsdaler, was recovered chiefly from higher taxation on both Danish and Norwegian farm properties.

[Lockhart, Paul D., page 41] After state finances collapsed in the aftermath of the war, King Frederick II called

Peder Oxe

Peter is a common masculine given name. It is derived directly from Greek , ''Petros'' (an invented, masculine form of Greek ''petra,'' the word for "rock" or "stone"), which itself was a translation of Aramaic ''Kefa'' ("stone, rock"), the new na ...

home to address the kingdom's economy. The taking over of Danish administration and finances by the able councillor, provided a marked improvement for the national treasury. Councillors of experience, including

Niels Kaas

Niels Kaas (1535 – 29 June 1594) was a Danish politician who served as Chancellor of Denmark from 1573 until his death. He was influential in the negotiation of the Peace of Stettin and in the upbringing of Christian IV. Kaas also played an i ...

,

Arild Huitfeldt

Arild Huitfeldt (Arvid) (11 September 1546 – 16 December 1609) was a Danish historian and state official, known for his vernacular Chronicle of Denmark.

Life

Huitfeldt was born into an aristocratic family from Scania, part of the Kingdom of ...

, and

Christoffer Valkendorff

Christoffer Valkendorff (1 September 152517 January 1601) was a Danish-Norwegian statesman and landowner. His early years in the service of Frederick II brought him both to Norway, Ösel and Livland. He later served both as Treasurer and ''Stad ...

, took care of the domestic administration. Subsequently, government finances were put in order and Denmark-Norway's economy improved. One of the chief expedients of the improved state of affairs was the raising of the

Sound Dues. Oxe, as lord treasurer, reduced the national debt considerably and redeemed portions of

crown lands.

Constructions in reign

After the

Northern Seven Years' War

The Northern Seven Years' War (also known as the ''Nordic Seven Years' War'', the ''First Northern War'' or the ''Seven Years War in Scandinavia'') was fought between the Kingdom of Sweden (1523–1611), Kingdom of Sweden and a coalition of Denm ...

a period of affluence and growth followed in Danish history. The greater financial liquidity of the crown and the king's decreased dependence on the

Council for funding, while not meaning that Frederick was actively seeking to sidestep conciliar control,

it did allow him to be less frugal than his late father,

Christian III

Christian III (12 August 1503 – 1 January 1559) reigned as King of Denmark from 1534 and King of Norway from 1537 until his death in 1559. During his reign, Christian formed close ties between the church and the crown. He established ...

, had been. Considerable funds were devoted to an expansion of

the Danish fleet and of the facilities for its support, not merely for security purposes but also to aid Frederick's active endeavours to rid the

Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

of

pirates. The increased revenues likewise enabled Frederik to undertake the construction of Denmark's first national

road network A street network is a system of interconnecting lines and points (called ''edges'' and ''nodes'' in network science) that represent a system of streets or roads for a given area. A street network provides the foundation for network analysis; for exa ...

, the so-called ''kongevej'' ('

King's Road

King's Road or Kings Road (or sometimes the King's Road, especially when it was the king's private road until 1830, or as a colloquialism by middle/upper class London residents), is a major street stretching through Chelsea and Fulham, both ...

'), connecting the larger towns and the royal residences.

The most visible area of expenditure, however, was the royal castles and the court itself. Frederick spent freely on the reconstruction of several royal residences and other cities:

*

Antvorskov

Antvorskov Monastery (Danish: ''Antvorskov Kloster'') was the principal Scandinavian monastery of the Catholic Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, located about one kilometer south of the town of Slagelse on Zealand, Denmark.

It served as the Scand ...

(near Slagelse, Sjælland), was one of Frederick's favourite hunting-castles. He later died at

Antvorskov

Antvorskov Monastery (Danish: ''Antvorskov Kloster'') was the principal Scandinavian monastery of the Catholic Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, located about one kilometer south of the town of Slagelse on Zealand, Denmark.

It served as the Scand ...

.

* In 1567, King Frederick II founded

Fredrikstad

Fredrikstad (; previously ''Frederiksstad''; literally "Fredrik's Town") is a city and municipality in Viken county, Norway. The administrative centre of the municipality is the city of Fredrikstad.

The city of Fredrikstad was founded in 15 ...

in Norway.

Frederik II Upper Secondary School in

Fredrikstad

Fredrikstad (; previously ''Frederiksstad''; literally "Fredrik's Town") is a city and municipality in Viken county, Norway. The administrative centre of the municipality is the city of Fredrikstad.

The city of Fredrikstad was founded in 15 ...

, one of the largest schools of its kind in Norway, is named after Frederick.

* He also rebuilt

Kronborg

Kronborg is a castle and stronghold in the town of Helsingør, Denmark. Immortalized as Elsinore in William Shakespeare's play ''Hamlet'', Kronborg is one of the most important Renaissance castles in Northern Europe and was inscribed on the UNE ...

in

Elsinore from a medieval fortress into a magnificent

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

castle, between 1574 and 1585.

* In 1560 Frederick converted the North Sealand farm Hillerødsholm into a great

Renaissance castle,

Frederiksborg.

* In 1561, Frederik II developed and fortified

Skanderborg

Skanderborg is a town in Skanderborg municipality, Denmark. It is situated on the north and north eastern brinks of Skanderborg Lake and there are several smaller ponds and bodies of water within the city itself, like Lillesø, Sortesø, Døj S ...

Castle with materials from

Øm Abbey

Øm Abbey (''Øm Kloster'') was a Cistercian monastery founded in 1172 in the Diocese of Aarhus near the town of Rye, between the lakes of Mossø and Gudensø in central Jutland, Denmark. It is one of many former monasteries and abbeys in the ...

.

For all Frederick's egalitarian behaviour at his court, Frederick was acutely aware of his elevated status. Like most monarchs of his day, he sought to bolster his international reputation through a measure of ostentatious display, in his patronage of artists and musicians, as well as in the elaborate ceremonies staged for royal weddings and other public celebrations.

Kronborg and " The King's Sound"

Frederick II had claimed naval supremacy in 'the king's sound', as he called

The Sound and, indeed, the whole expanse of waters lying between his Norwegian and Icelandic possessions. In 1583 he secured an agreement by which England made an annual payment for permission to sail there, and France later followed suit.

He also tried to bring the Icelandic trade and fisheries into the hands of his own subjects instead of Englishmen and Germans and encouraged adventurers such as

Magnus Heinason

Magnus Heinason (Mogens Heinesøn) (1548 – 18 January 1589) was a Faroese naval hero, trader and privateer.

Magnus Heinason served William the Silent and his son Maurice of Nassau, Prince of Orange for 10 years as a privateer, fighting t ...

, to whom he gave a monopoly of trade with the

Faeroes

The Faroe Islands ( ), or simply the Faroes ( fo, Føroyar ; da, Færøerne ), are a North Atlantic island group and an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark.

They are located north-northwest of Scotland, and about halfway betwee ...

, a half-share in ships captured on unlawful passage to the

White Sea

The White Sea (russian: Белое море, ''Béloye móre''; Karelian and fi, Vienanmeri, lit. Dvina Sea; yrk, Сэрако ямʼ, ''Serako yam'') is a southern inlet of the Barents Sea located on the northwest coast of Russia. It is s ...

, and backing for a bold but unsuccessful attempt to reach east

Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is t ...

.

Relationship with the Church

The necessity of maintaining order within the church meant that royal interference into

ecclesiastical affairs was unavoidable. There was no longer an

archbishop

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdi ...

within the

hierarchy

A hierarchy (from Greek: , from , 'president of sacred rites') is an arrangement of items (objects, names, values, categories, etc.) that are represented as being "above", "below", or "at the same level as" one another. Hierarchy is an important ...

, so the king was the final authority in matters that could not be settled by the bishops alone. As his father,

Christian III

Christian III (12 August 1503 – 1 January 1559) reigned as King of Denmark from 1534 and King of Norway from 1537 until his death in 1559. During his reign, Christian formed close ties between the church and the crown. He established ...

, put it, kings were the ‘father to the superintendents’.

[Lockhart, Paul D., page 66]

As protector of the church and therefore of the clergy, Frederick frequently intervened in disputes between clergy and

laity

In religious organizations, the laity () consists of all members who are not part of the clergy, usually including any non-ordained members of religious orders, e.g. a nun or a lay brother.

In both religious and wider secular usage, a layperson ...

, even when the issues involved were trivial ones.

Frederik II, repeatedly came to the defence of new parish priests whose congregations tried to force them to marry their predecessors’

widow

A widow (female) or widower (male) is a person whose spouse has Death, died.

Terminology

The state of having lost one's spouse to death is termed ''widowhood''. An archaic term for a widow is "relict," literally "someone left over". This word ...

s, and sometimes to protect preachers from the wrath of overbearing noblemen. Conversely, the king – and especially Frederik II – would see to it personally that unruly, incompetent, or disreputable priests lost their parishes, or he would

pardon

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the ju ...

those who had been punished by their superintendents for minor infractions. Protecting and disciplining the clergy was, after all, part of the king's obligation to the

state church

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular, is not necessarily a t ...

.

[Lockhart, Paul D., page 67]

Frederik II was more active than his late father in extending his royal authority into areas that the 1537 Ordinance had protected from secular power. Frederik consulted with members of the

theological faculty at the

University of Copenhagen

The University of Copenhagen ( da, Københavns Universitet, KU) is a prestigious public university, public research university in Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark. Founded in 1479, the University of Copenhagen is the second-oldest university in ...

—the so-called ‘most learned ones’ (''højlærde'')—but he did not shy away from making changes in the most minute liturgical matters. He stipulated the books that every parish priest should have in his library, set standardized times for worship services in the towns, and set minimal standards of competence for all preachers.

Although Frederick interfered much in

ecclesiastical affairs,

Paul Douglas Lockhart pointed out, that Frederick "was not interested in dictating conscience", stating that "he wanted only to prevent useless religious disputes, disputes that could weaken the kingdom and leave it vulnerable to Catholic aggression".

Book of Concord

A good testimony of Frederik's stubborn resistance to all religious controversy can be found in his response to the late sixteenth-century

Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

statement of faith,

the Formula and Book of Concord.

The ‘Concord’, which was written by leading

Saxon

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

divines and sponsored by Frederik II's brother-in-law,

Augustus, Elector of Saxony

Augustus (31 July 152611 February 1586) was Elector of Saxony from 1553 to 1586.

First years

Augustus was born in Freiberg, the youngest child and third (but second surviving) son of Henry IV, Duke of Saxony, and Catherine of Mecklenburg. He con ...

, was an attempt to promote unity among the German Lutheran princes. As a unifier, however, the Concord was an abject failure.

[Lockhart, Paul D., page 71]

August had recently purged his court of

Calvinists and

Philippists

The Philippists formed a party in early Lutheranism. Their opponents were called Gnesio-Lutherans.

Before Luther's death

''Philippists'' was the designation usually applied in the latter half of the sixteenth century to the followers of Phili ...

, and

orthodox Lutherans like

Jacob Andreae composed the document. The Concord was extremely orthodox.

Frederik II had already clashed with his old friend and companion Augustus over theological issues: in 1575, Augustus had complained profoundly about the Calvinist sentiments expounded by

Niels Hemmingsen

Niels Hemmingsen (''Nicolaus Hemmingius'') (May/June 1513 – 23 May 1600) was a 16th-century Danish Lutheran theologian. He was pastor of the Church of the Holy Ghost, Copenhagen and professor at the University of Copenhagen.

Biography

B ...

in the

treatise

A treatise is a formal and systematic written discourse on some subject, generally longer and treating it in greater depth than an essay, and more concerned with investigating or exposing the principles of the subject and its conclusions."Treat ...

Syntagma institutionum christianarum (1574). Though Frederik tried to defend

Hemmingsen, who was his favourite divine, he also wanted to keep Augustus' friendship, and he therefor dismissed Hemmingsen – with honour – from his post at the

University of Copenhagen

The University of Copenhagen ( da, Københavns Universitet, KU) is a prestigious public university, public research university in Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark. Founded in 1479, the University of Copenhagen is the second-oldest university in ...

in 1579. Frederik was not nearly so receptive to August's promotion of the Concord.

[Lockhart, Paul D., page 70]

Like many other contemporaries of his time, Frederick believed that the Book of Concord promoted discord, and not harmony. Ignoring Augustus's warnings that a Calvinist plot had taken root in Denmark's clergy, he banned the Concord from his lands in July 1580.

Possession of the book, or even discussion of its contents, would be punished severely.

The king burned his own personal copies, which were sent to him by his sister

Anne

Anne, alternatively spelled Ann, is a form of the Latin female given name Anna. This in turn is a representation of the Hebrew Hannah, which means 'favour' or 'grace'. Related names include Annie.

Anne is sometimes used as a male name in the ...

, wife of Augustus. The Concord, he argued, contained "teachings which are foreign and alien to us and to our churches,

nd whichcould easily disrupt the unity which ... these kingdoms have hitherto maintained".

Marriage Ordinance

Frederik II's ‘Marriage Ordinance’ of 1582, inspired by

Niels Hemmingsen

Niels Hemmingsen (''Nicolaus Hemmingius'') (May/June 1513 – 23 May 1600) was a 16th-century Danish Lutheran theologian. He was pastor of the Church of the Holy Ghost, Copenhagen and professor at the University of Copenhagen.

Biography

B ...

’s writings on the institution, allowed divorce for a wide range of reasons, including

infidelity

Infidelity (synonyms include cheating, straying, adultery, being unfaithful, two-timing, or having an affair) is a violation of a couple's emotional and/or sexual exclusivity that commonly results in feelings of anger, sexual jealousy, and riva ...

,

impotence

Erectile dysfunction (ED), also called impotence, is the type of sexual dysfunction in which the penis fails to become or stay erect during sexual activity. It is the most common sexual problem in men.Cunningham GR, Rosen RC. Overview of mal ...

,

leprosy

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease (HD), is a long-term infection by the bacteria ''Mycobacterium leprae'' or ''Mycobacterium lepromatosis''. Infection can lead to damage of the nerves, respiratory tract, skin, and eyes. This nerve damag ...

,

venereal disease

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), also referred to as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and the older term venereal diseases, are infections that are Transmission (medicine), spread by Human sexual activity, sexual activity, especi ...

, and

outlaw

An outlaw, in its original and legal meaning, is a person declared as outside the protection of the law. In pre-modern societies, all legal protection was withdrawn from the criminal, so that anyone was legally empowered to persecute or kill them ...

ry.

Areas of interest