Finland during World War II on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The aim of the invasion was to liberate the 'Red Finns' and eventually annex

The aim of the invasion was to liberate the 'Red Finns' and eventually annex

During the summer and autumn of 1941 the Finnish Army was on the offensive, retaking the territories lost in the Winter War. The Finnish army also advanced further, especially in the direction of

During the summer and autumn of 1941 the Finnish Army was on the offensive, retaking the territories lost in the Winter War. The Finnish army also advanced further, especially in the direction of

Heikki Ylikankaan selvitys Valtioneuvoston kanslialle

'', Government of Finland

During World War II, Finland was anomalous: It was the only European country bordering the Soviet Union in 1939 which was still unoccupied by 1945. It was a country which sided with Germany, but in which native Jews and almost all refugees were safe from persecution.Hannu Rautkallio, ''Finland and Holocaust'', New York, 1987 It was the only country that fought alongside Nazi Germany which maintained democracy throughout the war. It was in fact the only democracy in mainland Europe that remained so despite being an involved party in the war.

According to the Finnish records 19,085 Soviet prisoners of war died in Finnish prison camps during the Continuation War, which means that 29.6% of Soviet POWs taken by the Finns did not survive. The high number of fatalities was mainly due to malnutrition and diseases. However, about 1,000 POWs were shot, primarily when attempting to escape.

When the Finnish Army controlled East Karelia between 1941 and 1944, several concentration camps were set up for Russian civilians. The first camp was set up on 24 October 1941, in Petrozavodsk. Of these interned civilians 4,361 perished mainly due to malnourishment, 90% of them during the spring and summer of 1942.''Suur-Suomen kahdet kasvot'' – Laine, Antti; 1982, , Otava

Finland never signed the

During World War II, Finland was anomalous: It was the only European country bordering the Soviet Union in 1939 which was still unoccupied by 1945. It was a country which sided with Germany, but in which native Jews and almost all refugees were safe from persecution.Hannu Rautkallio, ''Finland and Holocaust'', New York, 1987 It was the only country that fought alongside Nazi Germany which maintained democracy throughout the war. It was in fact the only democracy in mainland Europe that remained so despite being an involved party in the war.

According to the Finnish records 19,085 Soviet prisoners of war died in Finnish prison camps during the Continuation War, which means that 29.6% of Soviet POWs taken by the Finns did not survive. The high number of fatalities was mainly due to malnutrition and diseases. However, about 1,000 POWs were shot, primarily when attempting to escape.

When the Finnish Army controlled East Karelia between 1941 and 1944, several concentration camps were set up for Russian civilians. The first camp was set up on 24 October 1941, in Petrozavodsk. Of these interned civilians 4,361 perished mainly due to malnourishment, 90% of them during the spring and summer of 1942.''Suur-Suomen kahdet kasvot'' – Laine, Antti; 1982, , Otava

Finland never signed the

excerpt

* Nenye, Vesa et al. ''Finland at War: The Continuation and Lapland Wars 1941–45'' (2016

excerpt

* Nordling, Carl O. "Stalin's insistent endeavors at conquering Finland." ''Journal of Slavic Military Studies'' (2003) 16#1 pp: 137–157. * Sander, Gordon F. ''The Hundred Day Winter War: Finland's Gallant Stand against the Soviet Army''. (2013

online review

* * *

online

* Kivimäki, Ville. "Between defeat and victory: Finnish memory culture of the Second World War." ''Scandinavian Journal of History'' 37.4 (2012): 482–504. * Kivimäki, Ville. "Introduction Three Wars and Their Epitaphs: The Finnish History and Scholarship of World War II." in ''Finland in World War II'' (Brill, 2012) pp. 1–4

online

*

Axis History Factbook – Finland

The Battles of the Winter War

Jaeger Platoon: Finnish Army 1918–1945 Web Site

{{DEFAULTSORT:Military History of Finland During World War Ii Politics of World War II 20th century in Finland Finland in World War II

Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Both ...

participated in the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

initially in a defensive war against the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, followed by another battle against the Soviet Union acting in concert with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and then finally fighting alongside the Allies against Germany.

The first two major conflicts in which Finland was directly involved were the defensive Winter War

The Winter War,, sv, Vinterkriget, rus, Зи́мняя война́, r=Zimnyaya voyna. The names Soviet–Finnish War 1939–1940 (russian: link=no, Сове́тско-финская война́ 1939–1940) and Soviet–Finland War 1 ...

against an invasion by the Soviet Union in 1939, followed by the offensive Continuation War, together with Germany and the other Axis Powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were N ...

against the Soviets, in 1941–1944. The third conflict, the Lapland War

During World War II, the Lapland War ( fi , Lapin sota; sv, Lapplandskriget; german: Lapplandkrieg) saw fighting between Finland and Nazi Germany – effectively from September to November 1944 – in Finland's northernmost region, Lapland. ...

against Germany in 1944–1945, followed the signing of the Moscow Armistice

The Moscow Armistice was signed between Finland on one side and the Soviet Union and United Kingdom on the other side on 19 September 1944, ending the Continuation War. The Armistice restored the Moscow Peace Treaty of 1940, with a number of modi ...

with the Allied Powers, which stipulated expulsion of Nazi German forces from Finnish territory.

By the end of hostilities, Finland remained an independent country, albeit " Finlandized", having to cede nearly 10% of its territory, including Viipuri (Finland's second-largest city opulation Registeror fourth-largest city hurch and Civil Register depending on the census data), pay out a large amount of war reparations to the Soviet Union, and formally acknowledge partial responsibility for the Continuation War.

Background

Finnish independence

In 1809, theRussian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. The ...

seized Finland from Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

in the Finnish War

The Finnish War ( sv, Finska kriget, russian: Финляндская война, fi, Suomen sota) was fought between the Kingdom of Sweden and the Russian Empire from 21 February 1808 to 17 September 1809 as part of the Napoleonic Wars. As a res ...

. Finland entered a personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interlink ...

with the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. The ...

as a grand duchy

A grand duchy is a country or territory whose official head of state or ruler is a monarch bearing the title of grand duke or grand duchess.

Relatively rare until the abolition of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, the term was often used in the o ...

with extensive autonomy

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy, from , ''autonomos'', from αὐτο- ''auto-'' "self" and νόμος ''nomos'', "law", hence when combined understood to mean "one who gives oneself one's ow ...

. During the period of Russian rule the country generally prospered. On 6 December 1917, during the Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

, the Finnish parliament ( ''Suomen Eduskunta'') declared independence from Russia, which was accepted by the Bolshevik government of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

on 31 December. In January 1918, the ''Eduskunta'' ordered General Carl Mannerheim to use local Finnish White Guards to disarm Finnish Red Guards

Red Guards () were a mass student-led paramilitary social movement mobilized and guided by Chairman Mao Zedong in 1966 through 1967, during the first phase of the Cultural Revolution, which he had instituted.Teiwes According to a Red Guard le ...

and Russian troops throughout the country, a process which began on 27 January and led to the beginning of the Finnish Civil War

The Finnish Civil War; . Other designations: Brethren War, Citizen War, Class War, Freedom War, Red Rebellion and Revolution, . According to 1,005 interviews done by the newspaper ''Aamulehti'', the most popular names were as follows: Civil W ...

.

After the Eastern Front and peace negotiations between the Bolsheviks and Germany collapsed, German troops intervened in the country and occupied Helsinki and Finland. The Red faction was defeated and the survivors were subjected to a reign of terror, in which at least 12,000 people died. A new government, with Juho Kusti Paasikivi

Juho Kusti Paasikivi (; 27 November 1870 – 14 December 1956) was the seventh president of Finland (1946–1956). Representing the Finnish Party until its dissolution in 1918 and then the National Coalition Party, he also served as Prime Minister ...

as prime minister, pursued a pro-German policy and sought to annex Russian Karelia, which had a Finnish-speaking majority, despite never having been a part of Finland.

Treaty of Tartu

After the extinction of the Hohenzollern monarchy on 9 November 1918, Poland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania became independent, German troops left Finland, and British ships patrolled the Baltic Sea. Mannerheim was elected regent by the ''Eduskunta'', and Finnish policy became pro-Entente as the western powers intervened in theRussian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

(7 November 1917 – 16 June 1923). Mannerheim favoured intervention against the Bolsheviks but suspicion of the White Russians who refused to recognise Finnish independence led to his aggressive policy being overruled; then, the Bolshevik victory in Russia forestalled Finnish hostilities.

Paasikivi led a delegation to Tartu

Tartu is the second largest city in Estonia after the Northern European country's political and financial capital, Tallinn. Tartu has a population of 91,407 (as of 2021). It is southeast of Tallinn and 245 kilometres (152 miles) northeast o ...

, in Estonia, with instructions to establish a frontier from Lake Ladoga in the south, via Lake Onega to the White Sea in the north. The importance of the Murmansk railway, built in 1916, led the Soviet delegation to reject the Finnish border proposal, and the treaty of 14 October 1920 recognised a border agreement in which Finland obtained the northern port of Petsamo (Pechenga), an outlet to the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

, and a border roughly the same as that of the former Grand Duchy of Finland

The Grand Duchy of Finland ( fi, Suomen suuriruhtinaskunta; sv, Storfurstendömet Finland; russian: Великое княжество Финляндское, , all of which literally translate as Grand Principality of Finland) was the predecess ...

. Claims on areas of Eastern Karelia were abandoned and the Soviets accepted that the south-eastern border would not be moved west of Petrograd.

Winter War

During theInterwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the First World War to the beginning of the Second World War. The interwar period was relative ...

, relations between Finland and the Soviet Union were tense. Some elements in Finland maintained the dream of a "Greater Finland" which included the Soviet-controlled part of Karelia

Karelia ( Karelian and fi, Karjala, ; rus, Каре́лия, links=y, r=Karélija, p=kɐˈrʲelʲɪjə, historically ''Korjela''; sv, Karelen), the land of the Karelian people, is an area in Northern Europe of historical significance fo ...

, while the proximity of the Finnish border to Leningrad

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

(now Saint Petersburg) caused worry among the Soviet leadership. On 23 August 1939, Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and the Soviet Union signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

, long_name = Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

, image = Bundesarchiv Bild 183-H27337, Moskau, Stalin und Ribbentrop im Kreml.jpg

, image_width = 200

, caption = Stalin and Ribbentrop shaking ...

, which included a secret clause demarcating Finland as part of the Soviet sphere of influence.

On 12 October the Soviet Union began negotiations with Finland regarding the disposition of the Karelian Isthmus

The Karelian Isthmus (russian: Карельский перешеек, Karelsky peresheyek; fi, Karjalankannas; sv, Karelska näset) is the approximately stretch of land, situated between the Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga in northwestern R ...

, the Hanko Peninsula

The Hanko Peninsula ( fi, Hankoniemi; ), also spelled Hango, is the southernmost point of mainland Finland. The soil is a sandy moraine, the last tip of the Salpausselkä ridge, and vegetation consists mainly of pine and low shrubs. The peninsu ...

, and various islands in the Gulf of Finland, all of which were considered by the Finns to be Finnish territory. No agreement was reached. On 26 November the Soviet Union accused the Finnish army of shelling the village of Mainila. It was subsequently found that the Soviets had in fact shelled their own village, in order to create a pretext for withdrawal from their non-aggression pact with Finland. On 30 November 1939, the Soviet Union attacked Finland. The attack was denounced by the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

, and as a result, the Soviet Union was expelled from that body on 14 December.

Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Both ...

to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

. To this end, a puppet government, the Finnish Democratic Republic

The Finnish Democratic Republic ( fi, Suomen kansanvaltainen tasavalta or ''Suomen kansantasavalta'', sv, Demokratiska Republiken Finland, Russian: ''Финляндская Демократическая Республика''), also known as t ...

, was established in Terijoki under the leadership of the exiled O. W. Kuusinen. The first attack, on 30 November 1939, was an aerial bombardment of the city of Helsinki, with subsidiary attacks all along the Finnish-Soviet border. This had the effect of instantly unifying the once deeply-divided Finnish people in defense of their homes and country, without any referendums needing to be carried out.

Strategic goals of the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army ( Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, afte ...

included cutting Finland in half and capturing Petsamo in the north and Helsinki in the south. The leader of the Leningrad Military District, Andrei Zhdanov

Andrei Aleksandrovich Zhdanov ( rus, Андре́й Алекса́ндрович Жда́нов, p=ɐnˈdrej ɐlʲɪˈksandrəvʲɪtɕ ˈʐdanəf, links=yes; – 31 August 1948) was a Soviet politician and cultural ideologist. After World Wa ...

, commissioned a celebratory piece from Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, , group=n (9 August 1975) was a Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist who became internationally known after the premiere of his First Symphony in 1926 and was regarded throughout his life as a major compo ...

, '' Suite on Finnish Themes'', intended to be performed as the marching bands of the Red Army paraded through Helsinki. The Soviets had been building up their forces on the border during the earlier negotiations, and now fielded four armies

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

composed of 16 divisions, with another three being brought into position; meanwhile, the Finnish army had just 9 smaller divisions.Chew, p.6 The Soviets also enjoyed overwhelming superiority in the number of armour and air units deployed. The Finns had to defend a border that was some 1287 km (800 miles) in length, putting them at a significant disadvantage.

The Winter War was fought in three stages: the initial Soviet advance, a short lull, and then a renewed Soviet offensive. The war was fought mainly in three areas. The Karelian Isthmus and the area of Lake Ladoga were the primary focus of the Soviet war effort. A two-pronged attack was launched in this region, with one pincer engaging Finnish forces on the Isthmus while the other went around Lake Ladoga in an attempt at encircling the defenders. This force was then to advance to and capture the city of Viipuri. The second front was in central Karelia, where Soviet forces were to advance to the city of Oulu

Oulu ( , ; sv, Uleåborg ) is a city, municipality and a seaside resort of about 210,000 inhabitants in the region of North Ostrobothnia, Finland. It is the most populous city in northern Finland and the fifth most populous in the country afte ...

, cutting the country in half. Finally, a drive from the north was intended to capture the Petsamo region. By late December the Soviets had become bogged down, with the two main fronts at a standstill as the Finns counterattacked with greater strength than anticipated. With the failure of two of its three offensives by the end of December, Soviet headquarters ordered a cessation of operations. By 27 December, it was observed that the Soviets were digging in on the Karelian Isthmus. In the north, the Finns had been pushed back to Nautsi

Nautsi (russian: Наутси) was a rural locality in Pechengsky District of Murmansk Oblast, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union. It lies on the east bank of the Paatsjoki River, which forms part of the border between Norway and Russia. Prior to it a ...

, but with reinforcements, had been able to take the higher ground and halt the Soviet advance south of Petsamo. During this period the Finns harassed supply columns and carried out raids against fortified Soviet positions. A lull followed in January 1940, as the Soviet army reassessed its strategy, and rearmed and resupplied. On 29 January, Molotov put an end to the puppet Terijoki Government

The Finnish Democratic Republic ( fi, Suomen kansanvaltainen tasavalta or ''Suomen kansantasavalta'', sv, Demokratiska Republiken Finland, Russian: ''Финляндская Демократическая Республика''), also known as ...

and recognized the Ryti–Tanner government as the legal government of Finland, informing it that the USSR was willing to negotiate peace.

The last phase began in February 1940, with a major artillery barrage that began on the 2nd and lasted until the 11th, accompanied by reconnaissance raids at key objectives. The Soviets, using new equipment and materials, also began using the tactic of rotating troops from the reserve to the front, thus keeping constant pressure on the Finnish defenders. It seemed that the Red Army had inexhaustible amounts of ammunition and supplies, as attacks were always preceded by barrages, followed by aerial assaults and then random troop movements against the lines. Finnish military and government leaders realized that their only hope of preserving their nation lay in negotiating a peace treaty with Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

.

The tenacity of the Finnish people, both military and civilian, in the face of a superior opponent gained the country much sympathy throughout the world; however, material support from other countries was very limited, as none of Finland's neighbors were willing to commit their militaries to a war against the USSR. The need for a diplomatic solution became even more apparent after Soviet forces broke through the Finnish defensive line on the Karelian Isthmus and moved on towards Viipuri.

A peace proposal authored by Molotov was sent to Helsinki in mid-February. It placed heavy demands on Finland, claiming more land for the USSR and imposing significant diplomatic and military sanctions. By 28 February, Molotov had made his offer into an ultimatum with a 48-hour time limit, which pushed the Finnish leadership to act quickly. On 12 March 1940, the Moscow Peace Treaty

The Moscow Peace Treaty was signed by Finland and the Soviet Union on 12 March 1940, and the ratifications were exchanged on 21 March. It marked the end of the 105-day Winter War, upon which Finland ceded border areas to the Soviet Union. The ...

was signed, with hostilities ending the following day. By the terms of the treaty, Finland ceded 9% of its territory to the USSR. This was more territory than the Soviets had originally demanded.

Interim peace

The period of peace following the Winter War was widely regarded in Finland as temporary, even when peace was announced in March 1940. A period of frantic diplomatic efforts and rearmament followed. The Soviet Union kept up intense pressure on Finland, thereby hastening the Finnish efforts to improve the security of the country. Defensive arrangements were attempted with Sweden and the United Kingdom, but the political and military situation in the context of theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

rendered these efforts fruitless. Finland then turned to Nazi Germany for military aid. As the German offensive against the Soviet Union (Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

) approached, the cooperation between the two countries intensified. German troops arrived in Finland and took up positions, mostly in Lapland, from where they would invade the Soviet Union.

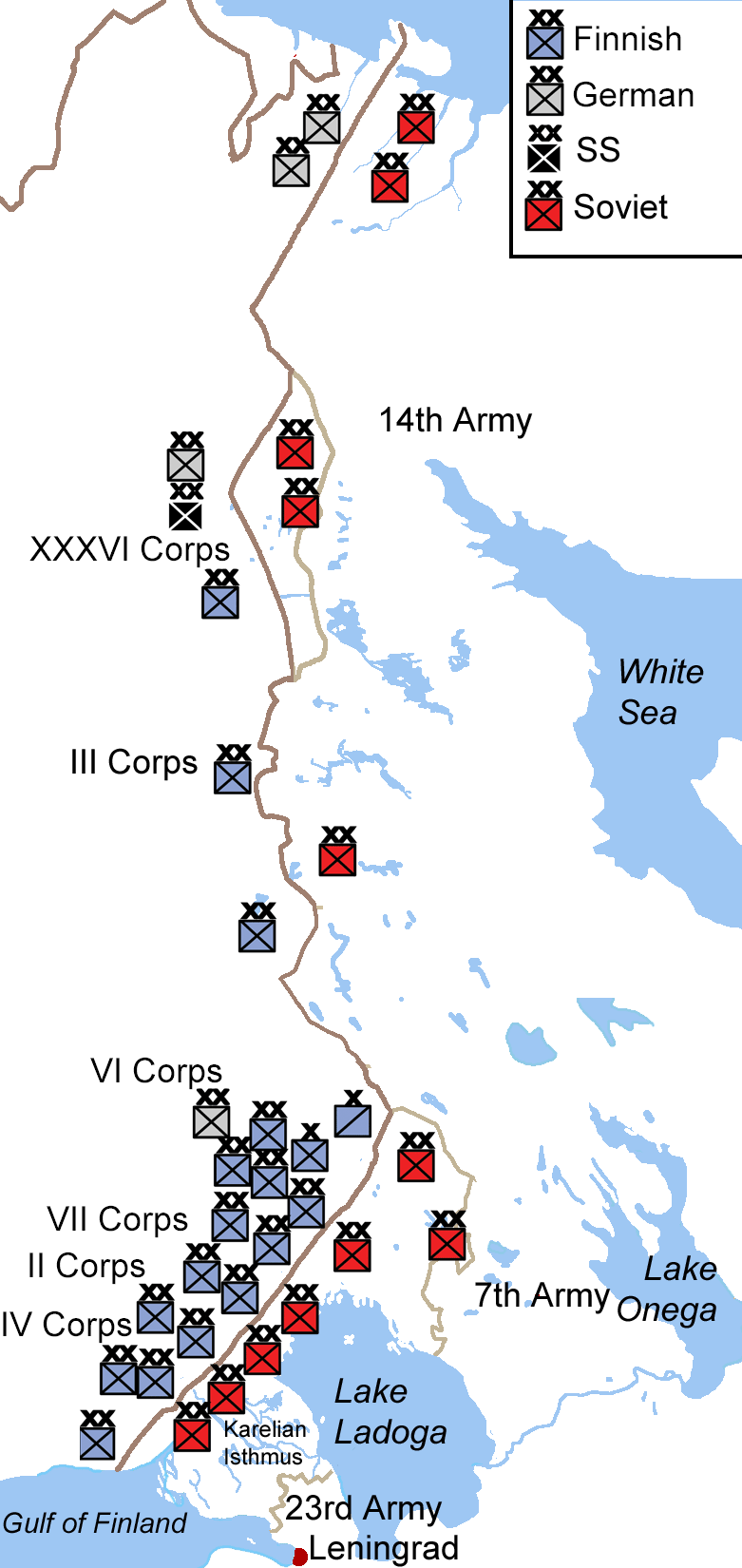

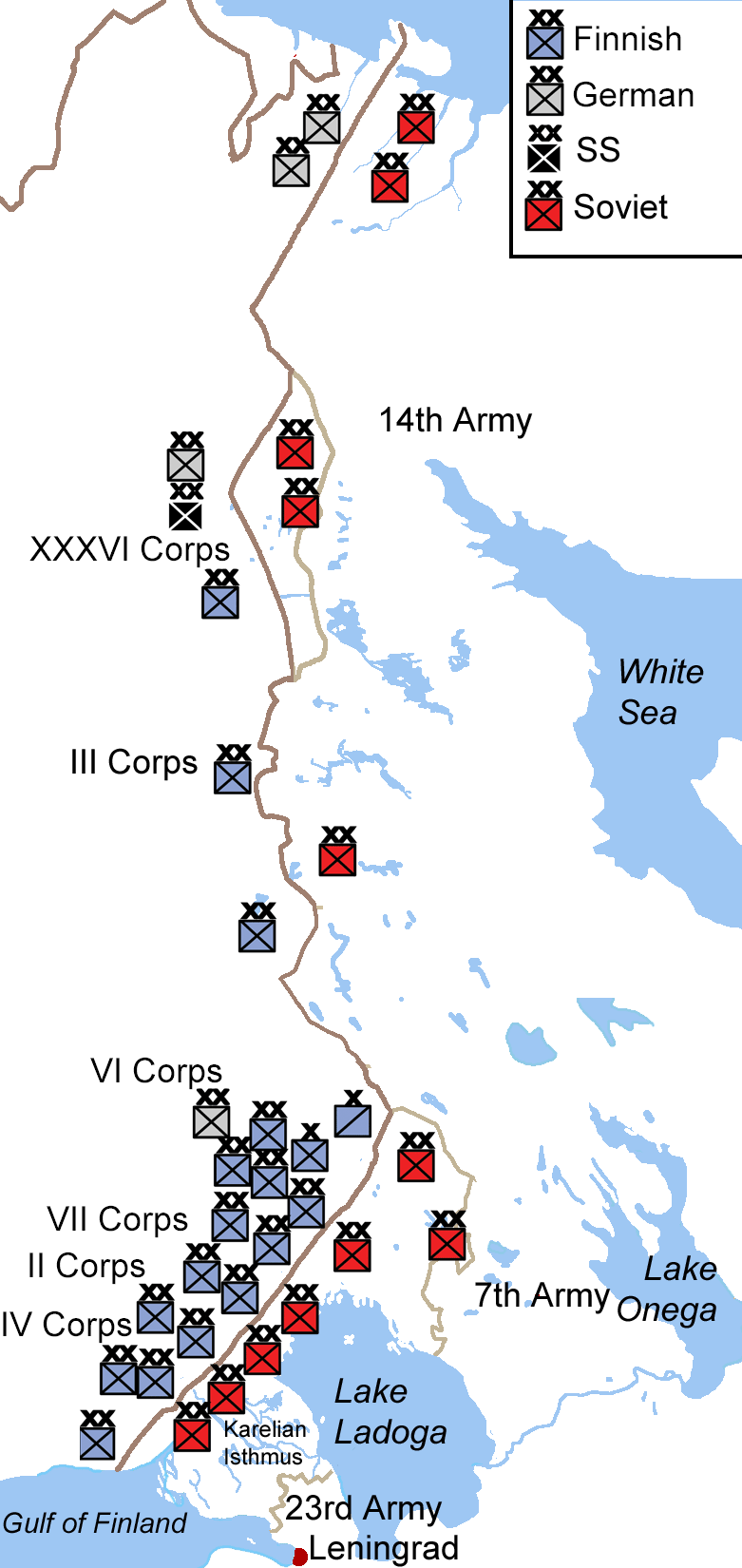

Operation Barbarossa began on 22 June 1941. On 25 June the Soviet Union launched an air raid against Finnish cities, after which Finland declared war and also allowed German troops stationed in Finland to begin offensive warfare. The resulting war was known to the Finns as the Continuation War.

Continuation War

During the summer and autumn of 1941 the Finnish Army was on the offensive, retaking the territories lost in the Winter War. The Finnish army also advanced further, especially in the direction of

During the summer and autumn of 1941 the Finnish Army was on the offensive, retaking the territories lost in the Winter War. The Finnish army also advanced further, especially in the direction of Lake Onega

Lake Onega (; also known as Onego, rus, Оне́жское о́зеро, r=Onezhskoe ozero, p=ɐˈnʲɛʂskəɪ ˈozʲɪrə; fi, Ääninen, Äänisjärvi; vep, Änine, Änižjärv) is a lake in northwestern Russia, on the territory of the Rep ...

, (east from Lake Ladoga), closing the blockade of the city of Leningrad from the north, and occupying Eastern Karelia, which had never been a part of Finland before. This resulted with Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

asking Roosevelt

Roosevelt may refer to:

*Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919), 26th U.S. president

*Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882–1945), 32nd U.S. president

Businesses and organisations

* Roosevelt Hotel (disambiguation)

* Roosevelt & Son, a merchant bank

* Roosev ...

for help in restoring peaceful relations between Finland and the Soviet Union on 4 August 1941. Finland's refusal of the Soviet offer of territorial concessions in exchange for a peace treaty would later cause Great Britain to declare war on Finland on 6 December (The US maintained diplomatic relations with Finland until the summer of 1944). The German and Finnish troops in Northern Finland were less successful, failing to take the Russian port city of Murmansk

Murmansk ( Russian: ''Мурманск'' lit. " Norwegian coast"; Finnish: ''Murmansk'', sometimes ''Muurmanski'', previously ''Muurmanni''; Norwegian: ''Norskekysten;'' Northern Sámi: ''Murmánska;'' Kildin Sámi: ''Мурман ланнҍ ...

during Operation Silver Fox

Operation Silver Fox (german: Silberfuchs; fi, Hopeakettu) from 29 June to 17 November 1941, was a joint German– Finnish military operation during the Continuation War on the Eastern Front of World War II against the Soviet Union. The object ...

.

On 31 July 1941 the United Kingdom launched raids on Kirkenes and Petsamo to demonstrate support for the Soviet Union. These raids were unsuccessful.

In December 1941, the Finnish army took defensive positions. This led to a long period of relative calm in the front line, lasting until 1944. During this period, starting at 1941 but especially after the major German defeat in the Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad (23 August 19422 February 1943) was a major battle on the Eastern Front of World War II where Nazi Germany and its allies unsuccessfully fought the Soviet Union for control of the city of Stalingrad (later r ...

, intermittent peace inquiries took place. These negotiations did not lead to any settlement.

On 16 March 1944, the President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United St ...

, Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As th ...

, called for Finland to disassociate itself from Nazi Germany.

On 9 June 1944, the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army ( Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, afte ...

launched a major strategic offensive against Finland, attaining vast numerical superiority and surprising the Finnish army. This attack pushed the Finnish forces approximately to the same positions as they were holding at the end of the Winter War. Eventually, the Soviet offensive was fought to a standstill in the Battle of Tali-Ihantala

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

, while still tens or hundreds of kilometres in front of the main Finnish line of fortifications, the Salpa Line

The Salpa Line ( fi, Salpalinja, literally ''Latch line''; sv, Salpalinjen), or its official name, Suomen Salpa (''Finland's Latch''), is a bunker line on the eastern border of Finland. It was built in 1940–1941 during the Interim Peace betwee ...

. However, the war had exhausted Finnish resources and it was believed that the country would not be able to hold against another major attack.

The worsening situation in 1944 had led to Finnish president Risto Ryti

Risto Heikki Ryti (; 3 February 1889 – 25 October 1956) served as the fifth president of Finland from 1940 to 1944. Ryti started his career as a politician in the field of economics and as a political background figure during the interwar peri ...

giving Germany his personal guarantee that Finland would not negotiate peace with the Soviet Union for as long as he was the president. In exchange, Germany delivered weapons to the Finns. After the Soviet offensive was halted, however, Ryti resigned. Due to the war, elections could not be held, and therefore the Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

selected the Marshal of Finland Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim

Baron Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim (, ; 4 June 1867 – 27 January 1951) was a Finnish military leader and statesman. He served as the military leader of the Whites in the Finnish Civil War of 1918, as Regent of Finland (1918–1919), as comm ...

, the Finnish commander-in-chief, as president and charged him with negotiating a peace.

The Finnish front had become a sideshow for the Soviet leadership, as they were in a race to reach Berlin before the Western Allies

The Allies, formally referred to as the United Nations from 1942, were an international military coalition formed during the Second World War (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis powers, led by Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and Fascist Italy. ...

. This, and the heavy casualties inflicted on the Red Army by the Finns, led to the transfer of most troops from the Finnish front. On 4 September 1944 a ceasefire was agreed, and the Moscow armistice

The Moscow Armistice was signed between Finland on one side and the Soviet Union and United Kingdom on the other side on 19 September 1944, ending the Continuation War. The Armistice restored the Moscow Peace Treaty of 1940, with a number of modi ...

between the Soviet Union and United Kingdom on one side and Finland on the other was signed on 19 September.

Moscow armistice

The Moscow armistice was signed by Finland and the Soviet Union on 19 September 1944 ending the Continuation War, though the final peace treaty was not to be signed until 1947 in Paris. The conditions for peace were similar to those previously agreed in the 1940 Moscow Peace Treaty, with Finland being forced to cede parts of Finnish Karelia, a part of Salla and islands in the Gulf of Finland. The new armistice also handed the whole of Petsamo over to the Soviet Union. Finland also agreed to legalize communist parties and ban fascist organizations. Finally, the armistice also demanded that Finland must expel German troops from its territory, which was the cause of theLapland War

During World War II, the Lapland War ( fi , Lapin sota; sv, Lapplandskriget; german: Lapplandkrieg) saw fighting between Finland and Nazi Germany – effectively from September to November 1944 – in Finland's northernmost region, Lapland. ...

.

Lapland War

The Lapland War was fought between Finland and Nazi Germany in Lapland, the northernmost part of Finland. The main strategic interest of Germany in the region was thenickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow to ...

mines in the Petsamo area.

Initially the warfare was cautious on both sides, reflecting the previous cooperation of the two countries against their common enemy, but by the end of 1944 the fighting intensified. Finland and Germany had made an informal agreement and schedule for German troops to withdraw from Lapland to Norway. The Soviet Union did not accept this "friendliness" and pressured Finland to take a more active role in pushing the Germans out of Lapland, thus intensifying hostilities.

The Germans adopted a scorched-earth policy, and proceeded to lay waste to the entire northern half of the country as they retreated. Around 100,000 people lost their homes, adding to the burden of post-war reconstruction. The actual loss of life, however, was relatively light. Finland lost

approximately 1,000 troops and Germany about 2,000. The Finnish army expelled the last of the foreign troops from their soil in April 1945.

Post-war

The war caused great damage toinfrastructure

Infrastructure is the set of facilities and systems that serve a country, city, or other area, and encompasses the services and facilities necessary for its economy, households and firms to function. Infrastructure is composed of public and priv ...

and the economy. From the autumn of 1944, the Finnish army and navy performed many mine clearance operations, especially in Karelia, Lapland and the Gulf of Finland. Sea mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive device placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Unlike depth charges, mines are deposited and left to wait until they are triggered by the approach of, or contact with, any ...

clearance activities lasted until 1950. The mines caused many military and civilian casualties, particularly in Lapland.

As part of the Paris Peace Treaty

The Paris Peace Treaties (french: Traités de Paris) were signed on 10 February 1947 following the end of World War II in 1945.

The Paris Peace Conference lasted from 29 July until 15 October 1946. The victorious wartime Allied powers (princ ...

, Finland was classified as an ally of Nazi Germany, bearing its responsibility for the war. The treaty imposed heavy war reparations on Finland and stipulated the lease of the Porkkala

Porkkalanniemi ( sv, Porkala udd) is a peninsula in the Gulf of Finland, located at Kirkkonummi (Kyrkslätt) in Southern Finland.

The peninsula had great strategic value, as coastal artillery based there would be able to shoot more than half ...

area near the Finnish capital Helsinki

Helsinki ( or ; ; sv, Helsingfors, ) is the capital, primate, and most populous city of Finland. Located on the shore of the Gulf of Finland, it is the seat of the region of Uusimaa in southern Finland, and has a population of . The city' ...

as a military base for fifty years. The reparations were initially thought to be crippling for the economy, but a determined effort was made to pay them. The reparations were reduced by 25% in 1948 by the Soviet Union and were paid off in 1952. Porkkala was returned to Finnish control in 1956.

In subsequent years the position of Finland was unique in the Cold War. The country was heavily influenced by the Soviet Union, but was the only country on the Soviet pre-World War II border to retain democracy and a market economy

A market economy is an economic system in which the decisions regarding investment, production and distribution to the consumers are guided by the price signals created by the forces of supply and demand, where all suppliers and consumers are ...

. Finland entered into the Agreement of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance (YYA Treaty) with the Soviet Union in which the Soviet Union agreed to the neutral status of Finland. Arms purchases were balanced between East and West until the fall of the Soviet Union.

Assessment

Finland and Nazi Germany

During the Continuation War (1941–1944) Finland's wartime government claimed to be aco-belligerent

Co-belligerence is the waging of a war in cooperation against a common enemy with or without a formal treaty of military alliance. Generally, the term is used for cases where no alliance exists. Likewise, allies may not become co-belligerents in a ...

of Nazi Germany against the Soviet Union, and abstained from signing the Tripartite Pact

The Tripartite Pact, also known as the Berlin Pact, was an agreement between Germany, Italy, and Japan signed in Berlin on 27 September 1940 by, respectively, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Galeazzo Ciano and Saburō Kurusu. It was a defensive milita ...

. Finland was dependent on food, fuel, and armament shipments from Germany during this period, and was influenced to sign the Anti-Comintern Pact

The Anti-Comintern Pact, officially the Agreement against the Communist International was an anti-Communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on 25 November 1936 and was directed against the Communist International (Com ...

, a less formal alliance than the Tripartite Pact seen as by the Nazi leadership as a "litmus test of loyalty". The Finnish leadership adhered to many written and oral agreements on practical co-operation with Germany during the conflict. Finland was one of Germany's most important allies in the attack on the Soviet Union, allowing German troops to be based in Finland before the attack and joining in the attack on the USSR almost immediately. The 1947 Paris Peace treaty signed by Finland stated that Finland had been "an ally of Hitlerite Germany" and bore partial responsibility for the conflict.

Finland was an anomaly amongst German allies in that it retained an independent democratic government. Moreover, during the war, Finland kept its army outside the German command structure despite numerous attempts by the Germans to tie them more tightly together. Finland managed not to take part in the siege of Leningrad despite Hitler's wishes, and refused to cut the Murmansk railway.

Finnish Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

s were not persecuted, and even among extremists of the Finnish Right they were highly tolerated, as many leaders of the movement came from the clergy. Of approximately 500 Jewish refugees, eight were handed over to the Germans, a fact for which Finnish prime minister Paavo Lipponen

Paavo Tapio Lipponen (; born 23 April 1941) is a Finnish politician and former reporter. He was Prime Minister of Finland from 1995 to 2003, and Chairman of the Social Democratic Party of Finland from 1993 to 2005. He also served as Speaker of t ...

issued an official apology in 2000. The field synagogue

A synagogue, ', 'house of assembly', or ', "house of prayer"; Yiddish: ''shul'', Ladino: or ' (from synagogue); or ', "community". sometimes referred to as shul, and interchangeably used with the word temple, is a Jewish house of worsh ...

operated by the Finnish army was probably a unique phenomenon in the Eastern Front of the war. Finnish Jews fought alongside other Finns.

About 2,600–2,800 Soviet prisoners of war The following articles deal with Soviet prisoners of war.

* Camps for Russian prisoners and internees in Poland (1919–24)

* Soviet prisoners of war in Finland during World War II (1939–45)

*Nazi crimes against Soviet prisoners of war

During W ...

were handed over to the Germans in exchange for roughly 2,200 Finnic prisoners of war held by the Germans. In November 2003, the Simon Wiesenthal Center

The Simon Wiesenthal Center (SWC) is a Jewish human rights organization established in 1977 by Rabbi Marvin Hier. The center is known for Holocaust research and remembrance, hunting Nazi war criminals, combating anti-Semitism, tolerance educa ...

submitted an official request to Finnish President Tarja Halonen

Tarja Kaarina Halonen (; born 24 December 1943) is a Finnish politician who served as the 11th president of Finland, and the first woman to hold the position, from 2000 to 2012. She first rose to prominence as a lawyer with the Central Organisat ...

for a full-scale investigation by the Finnish authorities of the prisoner exchange. In the subsequent study by Professor Heikki Ylikangas it turned out that about 2,000 of the exchanged prisoners joined the Russian Liberation Army

The Russian Liberation Army; russian: Русская освободительная армия, ', abbreviated as (), also known as the Vlasov army after its commander Andrey Vlasov, was a collaborationist formation, primarily composed of Ru ...

. The rest, mostly army and political

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that studie ...

officers, (among them a name-based estimate of 74 Jews), most likely perished in Nazi concentration camps

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps, (officially) or (more commonly). The Nazi concentration camps are distinguished from other types of Nazi camps such as forced-labor camps, as well as conce ...

.Ylikangas, Heikki, Heikki Ylikankaan selvitys Valtioneuvoston kanslialle

'', Government of Finland

Finland and World War II overall

During World War II, Finland was anomalous: It was the only European country bordering the Soviet Union in 1939 which was still unoccupied by 1945. It was a country which sided with Germany, but in which native Jews and almost all refugees were safe from persecution.Hannu Rautkallio, ''Finland and Holocaust'', New York, 1987 It was the only country that fought alongside Nazi Germany which maintained democracy throughout the war. It was in fact the only democracy in mainland Europe that remained so despite being an involved party in the war.

According to the Finnish records 19,085 Soviet prisoners of war died in Finnish prison camps during the Continuation War, which means that 29.6% of Soviet POWs taken by the Finns did not survive. The high number of fatalities was mainly due to malnutrition and diseases. However, about 1,000 POWs were shot, primarily when attempting to escape.

When the Finnish Army controlled East Karelia between 1941 and 1944, several concentration camps were set up for Russian civilians. The first camp was set up on 24 October 1941, in Petrozavodsk. Of these interned civilians 4,361 perished mainly due to malnourishment, 90% of them during the spring and summer of 1942.''Suur-Suomen kahdet kasvot'' – Laine, Antti; 1982, , Otava

Finland never signed the

During World War II, Finland was anomalous: It was the only European country bordering the Soviet Union in 1939 which was still unoccupied by 1945. It was a country which sided with Germany, but in which native Jews and almost all refugees were safe from persecution.Hannu Rautkallio, ''Finland and Holocaust'', New York, 1987 It was the only country that fought alongside Nazi Germany which maintained democracy throughout the war. It was in fact the only democracy in mainland Europe that remained so despite being an involved party in the war.

According to the Finnish records 19,085 Soviet prisoners of war died in Finnish prison camps during the Continuation War, which means that 29.6% of Soviet POWs taken by the Finns did not survive. The high number of fatalities was mainly due to malnutrition and diseases. However, about 1,000 POWs were shot, primarily when attempting to escape.

When the Finnish Army controlled East Karelia between 1941 and 1944, several concentration camps were set up for Russian civilians. The first camp was set up on 24 October 1941, in Petrozavodsk. Of these interned civilians 4,361 perished mainly due to malnourishment, 90% of them during the spring and summer of 1942.''Suur-Suomen kahdet kasvot'' – Laine, Antti; 1982, , Otava

Finland never signed the Tripartite Pact

The Tripartite Pact, also known as the Berlin Pact, was an agreement between Germany, Italy, and Japan signed in Berlin on 27 September 1940 by, respectively, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Galeazzo Ciano and Saburō Kurusu. It was a defensive milita ...

, but was aided in its military assault on the Soviet Union by Germany from the beginning of Operation Barbarossa in 1941, and in its defence against Soviet attacks in 1944 prior to the separate peace with the Soviet Union in 1944. Finland was led by its elected president and parliament during the whole 1939–1945 period. As a result, some political scientists name it as one of the few instances where a democratic country was engaged in a war against one or more other democratic countries, namely the democracies in the Allied forces. However, nearly all Finnish military engagements in World War II were fought solely against an autocratic power, the Soviet Union, and the lack of direct conflicts specifically with other democratic countries leads others to exclude Finnish involvement in World War II as an example of a war between two or more democracies.Russert, Bruce. "The Fact of Democratic Peace," ''Grasping the Democratic Peace'', Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993.

Finnish President Tarja Halonen

Tarja Kaarina Halonen (; born 24 December 1943) is a Finnish politician who served as the 11th president of Finland, and the first woman to hold the position, from 2000 to 2012. She first rose to prominence as a lawyer with the Central Organisat ...

, speaking in 2005, said that "For us the world war meant a separate war against the Soviet Union and we did not incur any debt of gratitude to others". Finnish President Mauno Koivisto

Mauno Henrik Koivisto (; 25 November 1923 – 12 May 2017) was a Finnish politician who served as the ninth president of Finland from 1982 to 1994. He also served as the country's prime minister twice, from 1968 to 1970 and again from 1979 to 19 ...

also expressed similar views in 1993. However the view that Finland only fought separately during the Second World War remains controversial within Finland and was not generally accepted outside Finland. In a 2008 poll of 28 Finnish historians carried out by ''Helsingin Sanomat

''Helsingin Sanomat'', abbreviated ''HS'' and colloquially known as , is the largest subscription newspaper in Finland and the Nordic countries, owned by Sanoma. Except after certain holidays, it is published daily. Its name derives from that of ...

'', 16 said that Finland had been an ally of Nazi Germany, six said it had not been, and six did not take a position.

See also

*Military history of Finland during World War II

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

* Winter War

The Winter War,, sv, Vinterkriget, rus, Зи́мняя война́, r=Zimnyaya voyna. The names Soviet–Finnish War 1939–1940 (russian: link=no, Сове́тско-финская война́ 1939–1940) and Soviet–Finland War 1 ...

* Continuation War

* Lapland War

During World War II, the Lapland War ( fi , Lapin sota; sv, Lapplandskriget; german: Lapplandkrieg) saw fighting between Finland and Nazi Germany – effectively from September to November 1944 – in Finland's northernmost region, Lapland. ...

* Diplomatic history of World War II

The diplomatic history of World War II includes the major foreign policies and interactions inside the opposing coalitions, the Allies of World War II and the Axis powers, between 1939 and 1945.

High-level diplomacy began as soon as the war start ...

* East Karelian concentration camps East Karelian concentration camps were a set of concentration camps operated by the Finnish government in the areas of the Soviet Union occupied by the Finnish military administration during the Continuation War. These camps were organized by the a ...

* Nazism in Finland

In Finland, the far right was strongest in 1920–1940 when the Academic Karelia Society, Lapua Movement, Patriotic People's Movement (IKL) and Export Peace operated in the country and had hundreds of thousands of members. In addition to these ...

* Finnish Air Force

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, equipment = 159

, equipment_label ...

* History of Finland

The history of Finland begins around 9,000 BC during the end of the last glacial period. Stone Age cultures were Kunda, Comb Ceramic, Corded Ware, Kiukainen, and . The Finnish Bronze Age started in approximately 1,500 BC and the Iron Age sta ...

* Seitajärvi, devastated by Soviet partisan

Soviet partisans were members of resistance movements that fought a guerrilla war against Axis forces during World War II in the Soviet Union, the previously Soviet-occupied territories of interwar Poland in 1941–45 and eastern Finland. Th ...

attack in 1944

* Siege of Leningrad

The siege of Leningrad (russian: links=no, translit=Blokada Leningrada, Блокада Ленинграда; german: links=no, Leningrader Blockade; ) was a prolonged military blockade undertaken by the Axis powers against the Soviet Union, So ...

* Soviet prisoners of war in Finland

Soviet prisoners of war in Finland during World War II were captured in two Soviet- Finnish conflicts of that period: the Winter War and the Continuation War. The Finns took about 5,700 POWs during the Winter War, and due to the short length of ...

Footnotes

Bibliography

* Chew, Allen F.. ''The White Death''. East Lansing, MI, Michigan University State Press, 1971 * Condon, Richard W. ''The Winter War: Russia against Finland''. New York: Ballantine Books, 1972. * * Forster, Kent. "Finland's Foreign Policy 1940–1941: An Ongoing Historiographic Controversy," ''Scandinavian Studies'' (1979) 51#2 pp 109–123 * Jakobson, Max. ''The Diplomacy of the Winter War''. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1961. * Polvinen, Tuomo. "The Great Powers and Finland 1941–1944," ''Revue Internationale d'Histoire Militaire'' (1985), Issue 62, pp 133–152. * * Upton, Anthony F. ''Finland in Crisis 1940–1941: A Study in Small-Power Politics'' (Cornell University Press, 1965) * * Warner, Oliver. ''Marshal Mannerheim and the Finns''. Helsinki, Otava Publishing Co., 1967Further reading

* Chew, Allen F. ''The White Death: The Epic of the Soviet-Finnish Winter War'' (Michigan: Michigan State university press, 1971) * Kelly, Bernard. "Drifting Towards War: The British Chiefs of Staff, the USSR and the Winter War, November 1939 – March 1940." ''Contemporary British History'' (2009) 23#3 pp: 267–291. * * Krosby, H. Peter. ''Finland, Germany, and the Soviet Union, 1940-1941: The Petsamo Dispute'' (University of Wisconsin Press, 1968) * * Lunde, Henrik O. ''Finland's War of Choice: The Troubled German-Finnish Alliance in World War II'' (2011) * Nenye, Vesa et al. ''Finland at War: The Winter War 1939–40'' (2015excerpt

* Nenye, Vesa et al. ''Finland at War: The Continuation and Lapland Wars 1941–45'' (2016

excerpt

* Nordling, Carl O. "Stalin's insistent endeavors at conquering Finland." ''Journal of Slavic Military Studies'' (2003) 16#1 pp: 137–157. * Sander, Gordon F. ''The Hundred Day Winter War: Finland's Gallant Stand against the Soviet Army''. (2013

online review

* * *

Historiography and memory

* Forster, Kent. "Finland's Foreign Policy 1940–1941: An Ongoing Historiographic Controversy," ''Scandinavian Studies'' (1979) 51#2 pp 109–12online

* Kivimäki, Ville. "Between defeat and victory: Finnish memory culture of the Second World War." ''Scandinavian Journal of History'' 37.4 (2012): 482–504. * Kivimäki, Ville. "Introduction Three Wars and Their Epitaphs: The Finnish History and Scholarship of World War II." in ''Finland in World War II'' (Brill, 2012) pp. 1–4

online

*

External links

Axis History Factbook – Finland

The Battles of the Winter War

Jaeger Platoon: Finnish Army 1918–1945 Web Site

{{DEFAULTSORT:Military History of Finland During World War Ii Politics of World War II 20th century in Finland Finland in World War II