Elizabeth of Russia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Elizabeth Petrovna (russian: Елизаве́та (Елисаве́та) Петро́вна) (), also known as Yelisaveta or Elizaveta, reigned as

Elizabeth was born at Kolomenskoye, near

Elizabeth was born at Kolomenskoye, near

With much of his fame resting on his effective efforts to modernize Russia, Tsar Peter desired to see his children married into the royal houses of Europe, something which his immediate predecessors had consciously tended to avoid. Peter's son Aleksei Petrovich, born of his first marriage to a Russian noblewoman, had no problem securing a bride from the ancient house of Brunswick-Lüneburg. However, the Tsar experienced difficulties in arranging similar marriages for the daughters born of his second wife. When Peter offered either of his daughters in marriage to the future

With much of his fame resting on his effective efforts to modernize Russia, Tsar Peter desired to see his children married into the royal houses of Europe, something which his immediate predecessors had consciously tended to avoid. Peter's son Aleksei Petrovich, born of his first marriage to a Russian noblewoman, had no problem securing a bride from the ancient house of Brunswick-Lüneburg. However, the Tsar experienced difficulties in arranging similar marriages for the daughters born of his second wife. When Peter offered either of his daughters in marriage to the future

While

While

Elizabeth crowned herself Empress in the Dormition Cathedral on 25 April 1742 (O.S.), which would become standard for all emperors of Russia until 1896. At the age of thirty-three, with relatively little political experience, she found herself at the head of a great empire at one of the most critical periods of its existence. Her proclamation explained that the preceding reigns had led Russia to ruin: "The Russian people have been groaning under the enemies of the Christian faith, but she has delivered them from the degrading foreign oppression."

Russia had been under the domination of German advisers, so its Empress exiled the most unpopular of them, including

Elizabeth crowned herself Empress in the Dormition Cathedral on 25 April 1742 (O.S.), which would become standard for all emperors of Russia until 1896. At the age of thirty-three, with relatively little political experience, she found herself at the head of a great empire at one of the most critical periods of its existence. Her proclamation explained that the preceding reigns had led Russia to ruin: "The Russian people have been groaning under the enemies of the Christian faith, but she has delivered them from the degrading foreign oppression."

Russia had been under the domination of German advisers, so its Empress exiled the most unpopular of them, including

Despite the substantial changes made by Peter the Great, he had not exercised a really formative influence on the intellectual attitudes of the ruling classes as a whole. Although Elizabeth lacked the early education necessary to flourish as an intellectual (once finding the reading of secular literature to be "injurious to health"), she was clever enough to know its benefits and made considerable groundwork for her eventual successor, Catherine the Great. She made education freely available to all social classes (except for serfs), encouraged establishment of the very first university in Russia founded in Moscow by Mikhail Lomonosov, and helped to finance the establishment of the

Despite the substantial changes made by Peter the Great, he had not exercised a really formative influence on the intellectual attitudes of the ruling classes as a whole. Although Elizabeth lacked the early education necessary to flourish as an intellectual (once finding the reading of secular literature to be "injurious to health"), she was clever enough to know its benefits and made considerable groundwork for her eventual successor, Catherine the Great. She made education freely available to all social classes (except for serfs), encouraged establishment of the very first university in Russia founded in Moscow by Mikhail Lomonosov, and helped to finance the establishment of the

A gifted diplomat, Elizabeth hated bloodshed and conflict and went to great lengths to alter the Russian system of punishment, even outlawing

A gifted diplomat, Elizabeth hated bloodshed and conflict and went to great lengths to alter the Russian system of punishment, even outlawing

Elizabeth enjoyed and excelled in architecture, overseeing and financing many construction projects during her reign. One of the many projects from the Italian architect

Elizabeth enjoyed and excelled in architecture, overseeing and financing many construction projects during her reign. One of the many projects from the Italian architect

As an unmarried and childless empress, it was imperative for Elizabeth to find a legitimate heir to secure the

As an unmarried and childless empress, it was imperative for Elizabeth to find a legitimate heir to secure the

Elizabeth abolished the cabinet council system that had been used under Anna, and reconstituted the Senate as it had been under Peter the Great, with the chiefs of the departments of state (none of them German) attending. Her first task after this was to address the war with Sweden. On 23 January 1743, direct negotiations between the two powers were opened at

Elizabeth abolished the cabinet council system that had been used under Anna, and reconstituted the Senate as it had been under Peter the Great, with the chiefs of the departments of state (none of them German) attending. Her first task after this was to address the war with Sweden. On 23 January 1743, direct negotiations between the two powers were opened at

The great event of Elizabeth's later years was the

The great event of Elizabeth's later years was the

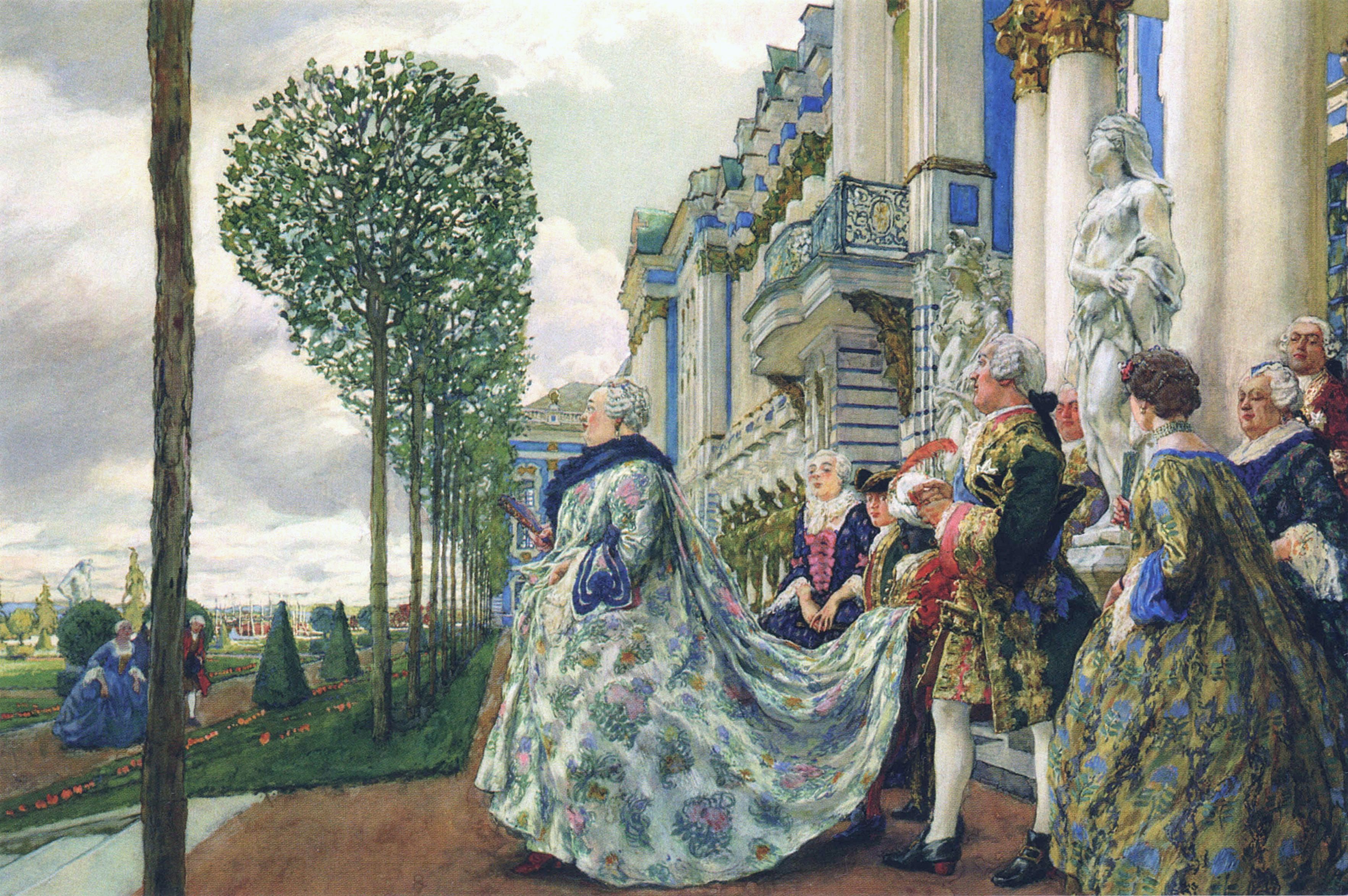

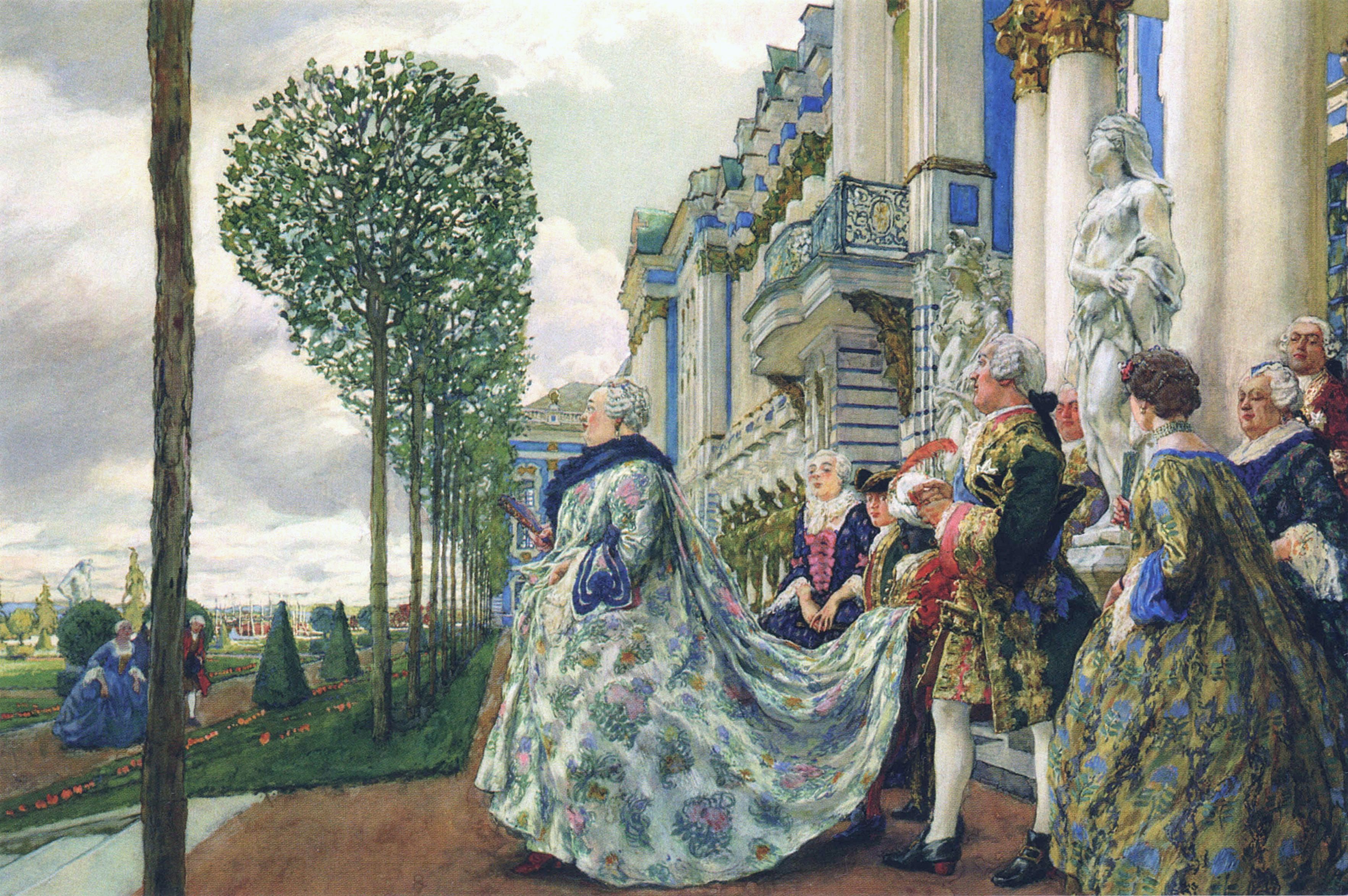

Elizabeth's court was one of the most splendid in all Europe. As historian

Elizabeth's court was one of the most splendid in all Europe. As historian

Empress of Russia

The emperor or empress of all the Russias or All Russia, ''Imperator Vserossiyskiy'', ''Imperatritsa Vserossiyskaya'' (often titled Tsar or Tsarina/Tsaritsa) was the monarch of the Russian Empire.

The title originated in connection with Russia' ...

from 1741 until her death in 1762. She remains one of the most popular Russian monarchs because of her decision not to execute a single person during her reign, her numerous construction

Construction is a general term meaning the art and science to form Physical object, objects, systems, or organizations,"Construction" def. 1.a. 1.b. and 1.c. ''Oxford English Dictionary'' Second Edition on CD-ROM (v. 4.0) Oxford University Pr ...

projects, and her strong opposition to Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

n policies.

The second-eldest daughter of Tsar Peter the Great (), Elizabeth lived through the confused successions of her father's descendants following her half-brother Alexei's death in 1718. The throne first passed to her mother Catherine I of Russia

Catherine I ( rus, Екатери́на I Алексе́евна Миха́йлова, Yekaterína I Alekséyevna Mikháylova; born , ; – ) was the second wife and empress consort of Peter the Great, and Empress Regnant of Russia from 1725 u ...

(), then to her nephew Peter II, who died in 1730 and was succeeded by Elizabeth's first cousin Anna. After the brief rule of Anna's infant great-nephew, Ivan VI, Elizabeth seized the throne with the military's support and declared her own nephew, the future Peter III, her heir.

During her reign Elizabeth continued the policies of her father and brought about a remarkable Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

in Russia. Her domestic policies allowed the nobles to gain dominance in local government while shortening their terms of service to the state. She encouraged Mikhail Lomonosov's foundation of the University of Moscow

M. V. Lomonosov Moscow State University (MSU; russian: Московский государственный университет имени М. В. Ломоносова) is a public research university in Moscow, Russia and the most prestigious ...

, the highest-ranking Russian educational institution. Her court became one of the most splendid in all Europe, especially regarding architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing building ...

: she modernized Russia's road

A road is a linear way for the conveyance of traffic that mostly has an improved surface for use by vehicles (motorized and non-motorized) and pedestrians. Unlike streets, the main function of roads is transportation.

There are many types of ...

s, encouraged Ivan Shuvalov

Ivan Ivanovich Shuvalov (russian: link=no, Ива́н Ива́нович Шува́лов; 1 November 172714 November 1797) was called the Maecenas of the Russian Enlightenment and the first Russian Minister of Education. Russia's first theat ...

's foundation of the Imperial Academy of Arts

The Russian Academy of Arts, informally known as the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts, was an art academy in Saint Petersburg, founded in 1757 by the founder of the Imperial Moscow University Ivan Shuvalov under the name ''Academy of the T ...

, and financed grandiose Baroque projects of her favourite architect, Bartolomeo Rastrelli

Francesco Bartolomeo Rastrelli (russian: Франче́ско Бартоломе́о (Варфоломе́й Варфоломе́евич) Растре́лли; 1700 in Paris, Kingdom of France – 29 April 1771 in Saint Petersburg, Russian Emp ...

, particularly in Peterhof Palace

The Peterhof Palace ( rus, Петерго́ф, Petergóf, p=pʲɪtʲɪrˈɡof,) (an emulation of early modern Dutch "Pieterhof", meaning "Pieter's Court"), is a series of palaces and gardens located in Petergof, Saint Petersburg, Russia, commi ...

. The Winter Palace

The Winter Palace ( rus, Зимний дворец, Zimnij dvorets, p=ˈzʲimnʲɪj dvɐˈrʲɛts) is a palace in Saint Petersburg that served as the official residence of the Russian Emperor from 1732 to 1917. The palace and its precincts now ...

and the Smolny Cathedral

Smolny Convent or Smolny Convent of the Resurrection (''Voskresensky'', Russian: Воскресенский новодевичий Смольный монастырь), located on Ploschad Rastrelli (Rastrelli Square), on the left bank of the Ri ...

in Saint Petersburg are among the chief monuments of her reign.

Elizabeth led the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

during the two major European conflicts of her time: the War of Austrian Succession

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

(1740–1748) and the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (175 ...

(1756–1763). She and diplomat Aleksey Bestuzhev-Ryumin

Count Alexey Petrovich Bestuzhev-Ryumin (russian: Алексе́й Петро́вич Бесту́жев-Рю́мин; 1 June 1693 – 21 April 1766) was a Russian diplomat and chancellor. He was one of the most influential and successful diplomats ...

solved the first event by forming an alliance with Austria and France, but indirectly caused the second. Russian troops enjoyed several victories against Prussia and briefly occupied Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

, but when Frederick the Great

Frederick II (german: Friedrich II.; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was King in Prussia from 1740 until 1772, and King of Prussia from 1772 until his death in 1786. His most significant accomplishments include his military successes in the S ...

was finally considering surrender in January 1762, the Russian Empress died. She was the last agnatic member of the House of Romanov

The House of Romanov (also transcribed Romanoff; rus, Романовы, Románovy, rɐˈmanəvɨ) was the reigning dynasty, imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after the Tsarina, Anastacia of Russia, Anastasi ...

to reign over the Russian Empire.

Early life

Childhood and teenage years

Elizabeth was born at Kolomenskoye, near

Elizabeth was born at Kolomenskoye, near Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

, on 18 December 1709 ( O.S.). Her parents were Peter the Great, Tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East and South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" in the European medieval sense of the ter ...

of Russia and Catherine

Katherine, also spelled Catherine, and other variations are feminine names. They are popular in Christian countries because of their derivation from the name of one of the first Christian saints, Catherine of Alexandria.

In the early Christ ...

. Catherine was the daughter of Samuel Skowroński, a subject of Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a European state that existed from the 13th century to 1795, when the territory was partitioned among the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Habsburg Empire of Austria. The state was founded by Lit ...

. Although no documentary record exists, her parents were said to have married secretly at the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

at some point between 23 October and 1 December 1707. Their official marriage was at Saint Isaac's Cathedral

Saint Isaac's Cathedral or Isaakievskiy Sobor (russian: Исаа́киевский Собо́р) is a large architectural landmark cathedral that currently functions as a museum with occasional church services in Saint Petersburg, Russia. It is ...

in Saint Petersburg on 9 February 1712. On this day, the two children previously born to the couple ( Anna and Elizabeth) were legitimized by their father and given the title of Tsarevna

Tsarevna (russian: Царевна) was the daughter of a Tsar of Russia before the 18th century. The name is meant as a daughter of a Tsar, or as a wife of a Tsarevich.

All of them were unmarried, and grew old in convents or in the Terem Palace, ...

("princess

Princess is a regal rank and the feminine equivalent of prince (from Latin '' princeps'', meaning principal citizen). Most often, the term has been used for the consort of a prince, or for the daughter of a king or prince.

Princess as a subs ...

") on 6 March 1711. Of the twelve children born to Peter and Catherine (five sons and seven daughters), only the sisters survived to adulthood. They had one older surviving sibling, crown prince Alexei Petrovich, who was Peter's son by his first wife, noblewoman Eudoxia Lopukhina

Tsarina Eudoxia Fyodorovna Lopukhina ( rus, Евдоки́я Фёдоровна Лопухина́, Yevdokíya Fyodorovna Lopukhiná; in Moscow – in Moscow) was a Russian Tsaritsa as the first wife of Peter I of Russia, and the last ethnic ...

.

As a child, Elizabeth was the favorite of her father, whom she resembled both physically and temperamentally. Even though he adored his daughter, Peter did not devote time or attention to her education; having both a son and grandson from his first marriage to a noblewoman, he did not anticipate that a daughter born to his former maid might one day inherit the Russian throne, which had until that point never been occupied by a woman; as such, it was left to Catherine to raise the girls, a task met with considerable difficulty due to her own lack of education. Despite this, Elizabeth was still considered to be a bright girl, if not brilliant, and had a French governess who gave lessons of mathematics, arts, languages, and sports. She grew interested in architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing building ...

, became fluent in Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

, German, and French, and became an excellent dancer and rider. Like her father, she was physically active and loved horseriding

Equestrianism (from Latin , , , 'horseman', 'horse'), commonly known as horse riding (Commonwealth English) or horseback riding (American English), includes the disciplines of riding, driving, and vaulting. This broad description includes the ...

, hunting

Hunting is the human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, or killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to harvest food (i.e. meat) and useful animal products ( fur/ hide, bone/tusks, horn/antler, ...

, sledging, skating, and gardening.

From her earliest years, Elizabeth was recognised as a vivacious young woman, and was regarded as the leading beauty of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

. The wife of the British ambassador described Grand Duchess Elizabeth as "fair, with light brown hair, large sprightly blue eyes, fine teeth and a pretty mouth. She is inclinable to be fat, but is very genteel and dances better than anyone I ever saw. She speaks German, French and Italian, is extremely gay, and talks to everyone..."

Marriage plans

Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached ...

, the Bourbons of France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

snubbed him due to the girls' post-facto legitimization.

In 1724, Peter betrothed his daughters to two young princes, first cousins to each other, who hailed from the tiny north German principality of Holstein-Gottorp

Holstein-Gottorp or Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp () is the historiographical name, as well as contemporary shorthand name, for the parts of the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, also known as Ducal Holstein, that were ruled by the dukes of Schlesw ...

and whose family was undergoing a period of political and economic turmoil. Anna Petrovna (aged 16) was to marry Charles Frederick, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp

Charles Frederick, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp () (30 April 1700 – 18 June 1739) was a Prince of Sweden and Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp and an important member of European royalty. His dynasty, the Dukes of Schleswig-Holstein-Gott ...

, who was then living in exile in Russia as Peter's guest after having failed in his attempt to succeed his maternal uncle as King of Sweden and whose patrimony was at that time under Danish occupation. Despite all this, the prince was of impeccable birth and well-connected to many royal houses; it was a respectable and politically useful alliance. In the same year, Elizabeth was betrothed to marry Charles Frederick's first cousin, Charles Augustus of Holstein-Gottorp

Holstein-Gottorp or Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp () is the historiographical name, as well as contemporary shorthand name, for the parts of the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, also known as Ducal Holstein, that were ruled by the dukes of Schlesw ...

, the eldest son of Christian Augustus, Prince of Eutin. Anna Petrovna's wedding took place in 1725 as planned, even though her father had died () a few weeks before the nuptials. In Elizabeth's case, however, her fiancé died on 31 May 1727, before her wedding could be celebrated. This came as a double blow to Elizabeth, because her mother (who had ascended to the throne as Catherine I) had died just two weeks previously, on 17 May 1727.

By the end of May 1727, 17-year-old Elizabeth had lost her fiancé and both of her parents. Furthermore, her half-nephew Peter II had ascended the throne. Her marriage prospects continued to fail to improve three years later, when her nephew died and was succeeded on the throne by Elizabeth's first cousin Anna, daughter of Ivan V

Ivan V Alekseyevich (russian: Иван V Алексеевич; – ) was Tsar of Russia between 1682 and 1696, jointly ruling with his younger half-brother Peter I. Ivan was the youngest son of Alexis I of Russia by his first wife, Maria M ...

. There was little love lost between the cousins and no prospect of either any Russian nobleman or any foreign prince seeking Elizabeth's hand in marriage. Nor could she marry a commoner because it would cost her royal status, property rights and claim to the throne. The fact that Elizabeth was something of a beauty did not improve marriage prospects, but instead earned her resentment. When the Empress Anna asked the Chinese minister in Saint Petersburg to identify the most beautiful woman at her court, he pointed to Elizabeth, much to Anna's displeasure.

Elizabeth's response to the lack of marriage prospects was to take Alexander Shubin, a handsome sergeant in the Semyonovsky Life Guards Regiment

The Semyonovsky Lifeguard Regiment (, ) was one of the two oldest guard regiments of the Imperial Russian Army. The other one was the Preobrazhensky Regiment. In 2013, it was recreated for the Russian Armed Forces as a rifle regiment, its name ...

, as her lover. When Empress Anna found out about this, she banished him to Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive region, geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a ...

. After consoling herself, Elizabeth turned to handsome coachmen and footmen for her sexual pleasure. She eventually found a long-term companion in Alexei Razumovsky, a kind-hearted and handsome Ukrainian peasant serf with a good bass voice

Bass or Basses may refer to:

Fish

* Bass (fish), various saltwater and freshwater species

Music

* Bass (sound), describing low-frequency sound or one of several instruments in the bass range:

** Bass (instrument), including:

** Acoustic bass gu ...

. Razumovsky had been brought from his village to Saint Petersburg by a nobleman to sing for a church choir, but the Grand Duchess purchased the talented serf from the nobleman for her own choir. A simple-minded man, Razumovsky never showed interest in affairs of state during all the years of his relationship with Elizabeth, which spanned from the days of her obscurity to the height of her power. As the couple was devoted to each other, there is reason to believe that they might even have married in a secret ceremony. In 1742, the Holy Roman Emperor made Razumovsky a count

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility. Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty''. New York: ...

of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

. In 1756, Elizabeth made him a prince

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. T ...

and field marshal.

Imperial coup

While

While Aleksandr Danilovich Menshikov

Prince Aleksander Danilovich Menshikov (russian: Алекса́ндр Дани́лович Ме́ншиков, tr. ; – ) was a Russian statesman, whose official titles included Generalissimo, Prince of the Russian Empire and Duke of Izhora ...

remained in power (until September 1727), the government of Elizabeth's adolescent nephew Peter II (reigned 1727–1730) treated her with liberality and distinction. However, the Dolgorukov

The House of Dolgorukov () is a princely Russian family of Rurikid stock. They are a cadet branch of the Obolenskiy family (until 1494 the rulers of Obolensk, one of the Upper Oka Principalities) and as such claiming patrilineal descent from ...

s, an ancient boyar family, deeply resented Menshikov. With Peter II's attachment to Prince Ivan Dolgorukov and two of their family members on the Supreme State Council, they had the leverage for a successful . Menshikov was arrested, stripped of all his honours and properties, and exiled to northern Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive region, geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a ...

, where he died in November 1729. The Dolgorukovs hated the memory of Peter the Great and practically banished his daughter from Court.

During the reign of her cousin Anna (1730–1740), Elizabeth was gathering support in the background. Being the daughter of Peter the Great, she enjoyed much support from the Russian Guards regiments. She often visited the elite Guards regiments, marking special events with the officers and acting as godmother to their children. After the death of Empress Anna, the regency of Anna Leopoldovna

Anna Leopoldovna (russian: А́нна Леопо́льдовна; 18 December 1718 – 19 March 1746), born Elisabeth Katharina Christine von Mecklenburg-Schwerin and also known as Anna Carlovna (А́нна Ка́рловна), was regent of R ...

for the infant Ivan VI was marked by high taxes and economic problems. The French ambassador in Saint Petersburg, the Marquis de La Chétardie was deeply involved in planning a coup to depose the regent, whose foreign policy was opposed to the interests of France, and bribed numerous officers in the Imperial Guard to support Elizabeth's coup. The French adventurer Jean Armand de Lestocq

Count Jean Armand de L'Estocq (German: ''Johann Hermann Lestocq'', Russian: ''Иван Иванович Лесток''; 29 April 1692, in Lüneburg – 12 June 1767, in Saint Petersburg) was a French adventurer who wielded immense influence on the ...

helped her actions according to the advice of the marquis de La Chétardie and the Swedish ambassador, who were particularly interested in toppling the regime of Anna Leopoldovna.

On the night of 25 November 1741 (O.S.), Elizabeth seized power with the help of the Preobrazhensky Life Guards Regiment. Arriving at the regimental headquarters wearing a warrior's metal breastplate over her dress and grasping a silver cross, she challenged them: "Whom do you want to serve: me, your natural sovereign, or those who have stolen my inheritance?" Won over, the regiment marched to the Winter Palace

The Winter Palace ( rus, Зимний дворец, Zimnij dvorets, p=ˈzʲimnʲɪj dvɐˈrʲɛts) is a palace in Saint Petersburg that served as the official residence of the Russian Emperor from 1732 to 1917. The palace and its precincts now ...

and arrested the infant Emperor, his parents, and their own lieutenant-colonel, Count Burkhard Christoph von Munnich. It was a daring coup and, amazingly, succeeded without bloodshed. Elizabeth had vowed that if she became Empress, she would not sign a single death sentence, an extraordinary promise at the time but one that she kept throughout her life.

Despite Elizabeth's promise, there was still cruelty in her regime. Although she initially thought of allowing the young tsar and his mother to leave Russia, she imprisoned them later in a Shlisselburg Fortress The fortress at Shlisselburg is one of a series of fortifications built in Shlisselburg on Orekhovy Island in Lake Ladoga, near the present-day city of Saint Petersburg, Russia. The first fortress was built in 1323. It was the scene of many confli ...

, worried that they would stir up trouble for her in other parts of Europe. Fearing a coup on Ivan's favour, Elizabeth set about destroying all papers, coins or anything else depicting or mentioning Ivan. She had issued an order that if any attempt were made for the adult Ivan to escape, he was to be eliminated. Catherine the Great upheld the order, and when an attempt was made, he was killed and secretly buried within the fortress.

Another case was Countess Natalia Lopukhina

Natalia Fyodorovna Lopukhina (November 11 1699– March 11 1763) was a Russian noble, court official and alleged political conspirator. She was a daughter of Matryona Balk, who was sister of Anna Mons and Willem Mons. She is famous for the Lopu ...

. The circumstances of Elizabeth's birth would later be used by her political opponents to challenge her right to the throne on grounds of illegitimacy. When Countess Lopukhina's son, Ivan Lopukhin, complained of Elizabeth in a tavern, he implicated his mother, himself and others in a plot to reinstate Ivan VI as tsar. Ivan Lopukhin was overheard and tortured for information. All male conspirators were sentenced to death while the female conspirators had their tongues removed and were publicly flogged.

Reign

Andrey Osterman

Count Andrey Ivanovich Osterman (''Heinrich Johann Friedrich Ostermann''; russian: Андрей Иванович Остерман) (9 June 1686 31 May 1747) was a German-born Russian statesman who came to prominence under Tsar Peter I of Russia ...

and Burkhard Christoph von Münnich. She passed down several pieces of legislation that undid much of the work her father had done to limit the power of the church.

With all her shortcomings (documents often waited months for her signature), Elizabeth had inherited her father's genius for government. Her usually keen judgment and her diplomatic tact again and again recalled Peter the Great. What sometimes appeared as irresolution and procrastination was most often a wise suspension of judgment under exceptionally difficult circumstances. From the Russian point of view, her greatness as a stateswoman consisted of her steady appreciation of national interests and her determination to promote them against all obstacles.

Educational reforms

Despite the substantial changes made by Peter the Great, he had not exercised a really formative influence on the intellectual attitudes of the ruling classes as a whole. Although Elizabeth lacked the early education necessary to flourish as an intellectual (once finding the reading of secular literature to be "injurious to health"), she was clever enough to know its benefits and made considerable groundwork for her eventual successor, Catherine the Great. She made education freely available to all social classes (except for serfs), encouraged establishment of the very first university in Russia founded in Moscow by Mikhail Lomonosov, and helped to finance the establishment of the

Despite the substantial changes made by Peter the Great, he had not exercised a really formative influence on the intellectual attitudes of the ruling classes as a whole. Although Elizabeth lacked the early education necessary to flourish as an intellectual (once finding the reading of secular literature to be "injurious to health"), she was clever enough to know its benefits and made considerable groundwork for her eventual successor, Catherine the Great. She made education freely available to all social classes (except for serfs), encouraged establishment of the very first university in Russia founded in Moscow by Mikhail Lomonosov, and helped to finance the establishment of the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts

The Russian Academy of Arts, informally known as the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts, was an art academy in Saint Petersburg, founded in 1757 by the founder of the Imperial Moscow University Ivan Shuvalov under the name ''Academy of the Thr ...

.

Internal peace

capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

. According to historian Robert Nisbet Bain

Robert Nisbet Bain (1854–1909) was a British historian and linguist who worked for the British Museum.

Life

Bain was born in London in 1854 to David and Elizabeth (born Cowan) Bain.

Bain was a fluent linguist who could use over twenty la ...

, it was one of her "chief glories that, so far as she was able, she put a stop to that mischievous contention of rival ambitions at Court, which had disgraced the reigns of Peter II, Anna, and Ivan VI, and enabled foreign powers to freely interfere in the domestic affairs of Russia."

Construction projects

Elizabeth enjoyed and excelled in architecture, overseeing and financing many construction projects during her reign. One of the many projects from the Italian architect

Elizabeth enjoyed and excelled in architecture, overseeing and financing many construction projects during her reign. One of the many projects from the Italian architect Bartolomeo Rastrelli

Francesco Bartolomeo Rastrelli (russian: Франче́ско Бартоломе́о (Варфоломе́й Варфоломе́евич) Растре́лли; 1700 in Paris, Kingdom of France – 29 April 1771 in Saint Petersburg, Russian Emp ...

was the reconstruction of Peterhof Palace

The Peterhof Palace ( rus, Петерго́ф, Petergóf, p=pʲɪtʲɪrˈɡof,) (an emulation of early modern Dutch "Pieterhof", meaning "Pieter's Court"), is a series of palaces and gardens located in Petergof, Saint Petersburg, Russia, commi ...

, adding several wings between 1745 and 1755. Her most famous creations were the Winter Palace

The Winter Palace ( rus, Зимний дворец, Zimnij dvorets, p=ˈzʲimnʲɪj dvɐˈrʲɛts) is a palace in Saint Petersburg that served as the official residence of the Russian Emperor from 1732 to 1917. The palace and its precincts now ...

, though she died before its completion, and the Smolny Convent

Smolny Convent or Smolny Convent of the Resurrection (''Voskresensky'', Russian language, Russian: Воскресенский новодевичий Смольный монастырь), located on Ploschad Rastrelli (Rastrelli Square), on the le ...

. The Palace is said to contain 1,500 rooms, 1,786 doors, and 1,945 windows, including bureaucratic offices and the Imperial Family's living quarters arranged in two enfilades, from the top of the Jordan Staircase. Regarding the latter building, historian Robert Nisbet Bain stated that "No other Russian sovereign ever erected so many churches."

The expedited completion of buildings became a matter of importance to the Empress and work continued throughout the year, even in winter's severest months. 859,555 ruble

The ruble (American English) or rouble (Commonwealth English) (; rus, рубль, p=rublʲ) is the currency unit of Belarus and Russia. Historically, it was the currency of the Russian Empire and of the Soviet Union.

, currencies named ''rub ...

s had been allocated to the project, a sum raised by a tax

A tax is a compulsory financial charge or some other type of levy imposed on a taxpayer (an individual or legal entity) by a governmental organization in order to fund government spending and various public expenditures (regional, local, or n ...

on state-owned taverns, but work temporarily ceased due to lack of resources. Ultimately, taxes were increased on salt and alcohol to completely fund the extra costs. However, Elizabeth's incredible extravagance ended up greatly benefiting the country's infrastructure. Needing goods shipped from all over the world, numerous road

A road is a linear way for the conveyance of traffic that mostly has an improved surface for use by vehicles (motorized and non-motorized) and pedestrians. Unlike streets, the main function of roads is transportation.

There are many types of ...

s in all Russia were modernized at her orders.

Selection of an heir

As an unmarried and childless empress, it was imperative for Elizabeth to find a legitimate heir to secure the

As an unmarried and childless empress, it was imperative for Elizabeth to find a legitimate heir to secure the Romanov dynasty

The House of Romanov (also transcribed Romanoff; rus, Романовы, Románovy, rɐˈmanəvɨ) was the reigning imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after the Tsarina, Anastasia Romanova, was married to ...

. She chose her nephew, Peter of Holstein-Gottorp. The young Peter had lost his mother shortly after he was born, and his father at the age of eleven. Elizabeth invited her young nephew to Saint Petersburg, where he was received into the Russian Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = ru

, image = Moscow July 2011-7a.jpg

, imagewidth =

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia

, abbreviation = ROC

, type ...

and proclaimed the heir to the throne on 7 November 1742. Keen to see the dynasty secured, Elizabeth immediately gave Peter the best Russian tutors and settled on Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst as a bride for her heir. Incidentally, Sophie's mother, Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp, was a sister of Elizabeth's own fiancé, who had died before the wedding. On her conversion to the Russian Orthodox Church, Sophie was given the name Catherine in memory of Elizabeth's mother. The marriage took place on 21 August 1745. Nine years later a son, the future Paul I Paul I may refer to:

*Paul of Samosata (200–275), Bishop of Antioch

* Paul I of Constantinople (died c. 350), Archbishop of Constantinople

*Pope Paul I (700–767)

*Paul I Šubić of Bribir (c. 1245–1312), Ban of Croatia and Lord of Bosnia

*Pau ...

, was born on 20 September 1754.

There is considerable speculation as to the actual paternity of Paul. It is suggested that he was not Peter's son at all but that his mother had engaged in an affair, to which Elizabeth had consented, with a young officer, Sergei Vasilievich Saltykov

Count Sergei Vasilievich Saltykov ( rus, link=no, Сергей Васильевич Салтыков, p=sʲɪrˈɡʲej vɐˈsʲilʲjɪvʲɪtɕ səltɨˈkof; c. 1726 – 1765) was a Russian officer (chamberlain (office), chamberlain) who became th ...

, who would have been Paul's biological father. Peter never gave any indication that he believed Paul to have been fathered by anyone but himself but took no interest in parenthood. Elizabeth most certainly took an active interest and acted as if she were his mother, instead of Catherine. Shortly after Paul’s birth the Empress ordered the midwife to take the baby and to follow her, and Catherine did not see her child for another month, for a short churching ceremony. Six months later, Elizabeth let Catherine see the child again. The child had, in effect, become a ward of the state and, in a larger sense, the property of the state.

Foreign policy

Elizabeth abolished the cabinet council system that had been used under Anna, and reconstituted the Senate as it had been under Peter the Great, with the chiefs of the departments of state (none of them German) attending. Her first task after this was to address the war with Sweden. On 23 January 1743, direct negotiations between the two powers were opened at

Elizabeth abolished the cabinet council system that had been used under Anna, and reconstituted the Senate as it had been under Peter the Great, with the chiefs of the departments of state (none of them German) attending. Her first task after this was to address the war with Sweden. On 23 January 1743, direct negotiations between the two powers were opened at Åbo

Turku ( ; ; sv, Åbo, ) is a city and former capital on the southwest coast of Finland at the mouth of the Aura River, in the region of Finland Proper (''Varsinais-Suomi'') and the former Turku and Pori Province (''Turun ja Porin lääni''; ...

. In the Treaty of Åbo

The Treaty of Åbo or the Treaty of Turku was a peace treaty signed between the Russian Empire and Sweden in Åbo ( fi, Turku) on in the end of the Russo-Swedish War of 1741–1743.

History

By the end of the war, the Imperial Russian Army had ...

, on 7 August 1743 (O.S.), Sweden ceded to Russia all of southern Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of B ...

east of the Kymmene River

The Kymi ( fi, Kymijoki, sv, Kymmene älv) is a river in Finland. It begins at Lake Päijänne, flows through the provinces of Päijänne Tavastia, Uusimaa and Kymenlaakso and discharges into the Gulf of Finland. The river passes the towns of H ...

, which became the boundary between the two states. The treaty also gave Russia the fortresses of Villmanstrand

Lappeenranta (; sv, Villmanstrand) is a city and municipality in the region of South Karelia, about from the Russian border and from the town of Vyborg (''Viipuri''). It is situated on the shore of the Lake Saimaa in southeastern Finland, and ...

and Fredrikshamn.

Bestuzhev

The concessions to Russia can be credited to the diplomatic ability of the new vice chancellor,Aleksey Bestuzhev-Ryumin

Count Alexey Petrovich Bestuzhev-Ryumin (russian: Алексе́й Петро́вич Бесту́жев-Рю́мин; 1 June 1693 – 21 April 1766) was a Russian diplomat and chancellor. He was one of the most influential and successful diplomats ...

, who had Elizabeth's support. She placed Bestuzhev at the head of foreign affairs immediately after her accession. He represented the anti-Franco-Prussian side of her council, and his objective was an alliance with England and Austria. At that time, it was probably advantageous to Russia. Both the Lopukhina affair

Natalia Fyodorovna Lopukhina (November 11 1699– March 11 1763) was a Russian noble, court official and alleged political conspirator. She was a daughter of Matryona Balk, who was sister of Anna Mons and Willem Mons. She is famous for the Lopu ...

and other attempts of Frederick the Great

Frederick II (german: Friedrich II.; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was King in Prussia from 1740 until 1772, and King of Prussia from 1772 until his death in 1786. His most significant accomplishments include his military successes in the S ...

and Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached ...

to get rid of Bestuzhev failed. Instead, they put the Russian court into the centre of a tangle of intrigue during the earlier years of Elizabeth's reign. Ultimately, the minister's strong support from the Empress prevailed.

Bestuzhev had many achievements. His effective diplomacy and 30,000 troops sent to the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

accelerated the peace negotiations, leading to the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (18 October 1748). He extricated his country from the Swedish imbroglio and reconciled his imperial mistress with the courts of Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

and London. He enabled Russia to assert herself effectually in Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, Sweden, and isolated the King of Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

by forcing him into hostile alliances. All this would have been impossible without the steady support of Elizabeth who trusted him completely in spite of the Chancellor's many enemies, most of whom were her personal friends.

However, on 14 February 1758, Bestuzhev was removed from office. The future Catherine II recorded, "He was relieved of all his decorations and rank, without a soul being able to reveal for what crimes or transgressions the first gentleman of the Empire was so despoiled, and sent back to his house as a prisoner." No specific crime was ever pinned on Bestuzhev. Instead, it was inferred that he had attempted to sow discord between the Empress and her heir and his consort. Enemies of the pro-Austrian Bestuzhev were his rivals; the Shuvalov family, Vice-Chancellor Mikhail Vorontsov, and the French ambassador.

Seven Years' War

The great event of Elizabeth's later years was the

The great event of Elizabeth's later years was the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (175 ...

. Elizabeth regarded the Convention of Westminster

The Diplomatic Revolution of 1756 was the reversal of longstanding alliances in Europe between the War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years' War. Austria went from an ally of Britain to an ally of France, the Dutch Republic, a long st ...

(16 January 1756) in which Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

and Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

agreed to unite their forces to oppose the entry of or the passage through Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

of troops of every foreign power, as utterly subversive of the previous conventions between Great Britain and Russia. Elizabeth sided against Prussia over a personal dislike of Frederick the Great

Frederick II (german: Friedrich II.; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was King in Prussia from 1740 until 1772, and King of Prussia from 1772 until his death in 1786. His most significant accomplishments include his military successes in the S ...

. She wanted him reduced within proper limits so that he might no longer be a danger to the empire. Elizabeth acceded to the Second Treaty of Versailles

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds each ...

, thus entering into an alliance with France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

and Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

against Prussia. On 17 May 1757 the Russian army, 85,000 strong, advanced against Königsberg

Königsberg (, ) was the historic Prussian city that is now Kaliningrad, Russia. Königsberg was founded in 1255 on the site of the ancient Old Prussian settlement ''Twangste'' by the Teutonic Knights during the Northern Crusades, and was name ...

.

The serious illness of the Empress, which began with a fainting-fit at Tsarskoe Selo

Tsarskoye Selo ( rus, Ца́рское Село́, p=ˈtsarskəɪ sʲɪˈlo, a=Ru_Tsarskoye_Selo.ogg, "Tsar's Village") was the town containing a former residence of the Russian imperial family and visiting nobility, located south from the c ...

(19 September 1757), the fall of Bestuzhev (21 February 1758) and the cabals and intrigues of the various foreign powers at Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, did not interfere with the progress of the war. The crushing defeat of Kunersdorf (12 August 1759) at last brought Frederick to the verge of ruin. From that day, he despaired of success, but he was saved for the moment by the jealousies of the Russian and Austrian commanders, which ruined the military plans of the allies.

From the end of 1759 to the end of 1761, the firmness of the Russian Empress was the one constraining political force that held together the heterogeneous, incessantly jarring elements of the anti-Prussian combination. From the Russian point of view, her greatness as a stateswoman consisted of her steady appreciation of Russian interests and her determination to promote them against all obstacles. She insisted throughout that the King of Prussia must be rendered harmless to his neighbours for the future and that the only way to do so was to reduce him to the rank of a Prince-Elector

The prince-electors (german: Kurfürst pl. , cz, Kurfiřt, la, Princeps Elector), or electors for short, were the members of the electoral college that elected the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

From the 13th century onwards, the prin ...

.

Frederick himself was quite aware of his danger. "I'm at the end of my resources," he wrote at the beginning of 1760. "The continuance of this war means for me utter ruin. Things may drag on perhaps till July, but then a catastrophe must come." On 21 May 1760, a fresh convention was signed between Russia and Austria, a secret clause of which, never communicated to the court of Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, ...

, guaranteed East Prussia to Russia as an indemnity for war expenses. The failure of the campaign of 1760, wielded by the inept Count Buturlin

Count Aleksander Borisovich Buturlin (Russian language, Russian, in full: граф Александр Борисович Бутурлин; 1694 – 1767) was a Russian general and courtier whose career was much furthered by his good looks and pers ...

, induced the court of Versailles on the evening of 22 January 1761 to present to the court of Saint Petersburg a dispatch to the effect that the king of France, by reason of the condition of his dominions, absolutely desired peace. The Russian empress' reply was delivered to the two ambassadors on 12 February. It was inspired by the most uncompromising hostility towards the king of Prussia. Elizabeth would not consent to any pacific overtures until the original object of the league had been accomplished.

Simultaneously, Elizabeth had conveyed to Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached ...

a confidential letter in which she proposed the signature of a new treaty of alliance of a more comprehensive and explicit nature than the preceding treaties between the two powers without the knowledge of Austria. Elizabeth's object in the mysterious negotiation seems to have been to reconcile France and Great Britain, in return for which signal service France was to throw all her forces into the German war. This project, which lacked neither ability nor audacity, foundered upon Louis XV's invincible jealousy of the growth of Russian influence in Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whic ...

and his fear of offending the Porte. It was finally arranged by the allies that their envoys at Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

should fix the date for the assembling of a peace congress and that in the meantime, the war against Prussia should be vigorously prosecuted. In 1760 a Russian flying column

A flying column is a small, independent, military land unit capable of rapid mobility and usually composed of all arms. It is often an ''ad hoc'' unit, formed during the course of operations.

The term is usually, though not necessarily, appli ...

briefly occupied Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

. Russian victories placed Prussia in serious danger.

The campaign of 1761 was almost as abortive as the campaign of 1760. Frederick acted on the defensive with consummate skill, and the capture of the Prussian fortress of Kolberg on Christmas Day 1761, by Rumyantsev, was the sole Russian success. Frederick, however, was now at the last gasp. On 6 January 1762, he wrote to Count Karl-Wilhelm Finck von Finckenstein, "We ought now to think of preserving for my nephew, by way of negotiation, whatever fragments of my territory we can save from the avidity of my enemies." A fortnight later, he wrote to Prince Ferdinand of Brunswick, "The sky begins to clear. Courage, my dear fellow. I have received the news of a great event." The Miracle of the House of Brandenburg

The Miracle of the House of Brandenburg is the name given by Frederick II of Prussia to the failure of Russia and Austria to follow up their victory over him at the Battle of Kunersdorf on 12 August 1759 during the Seven Years' War. The name is s ...

that snatched him from destruction was the death of the Russian empress, on 5 January 1762 ( N.S.).

Siberia

In 1742, the imperial government at Saint Petersburg ordered a Russian military expedition to conquer the Chukchi andKoryaks

Koryaks () are an indigenous people of the Russian Far East, who live immediately north of the Kamchatka Peninsula in Kamchatka Krai and inhabit the coastlands of the Bering Sea. The cultural borders of the Koryaks include Tigilsk in the south ...

, but the expedition failed and its commander, Major Dmitry Pavlutsky Dmitry Ivanovich Pavlutsky (russian: Дмитрий Иванович Павлуцкий; died 21 March 1747) was a Russian polar explorer and leader of military expeditions in Chukotka, best known for his campaigns of genocide against the indigenou ...

, was killed in 1747. On 12 March 1747, a party of 500 Chukchi warriors raided the Russian stockade of Anadyrsk

Anadyrsk was an important Russian ostrog (fortified settlement) in far northeastern Siberia from 1649 to 1764. It was on the Anadyr River, near the head of small-boat navigation, about 300 miles upstream, 12 miles northeast of the present Mark ...

. By 1750, it had become clear the Chukchi would be difficult to conquer. The Empress then changed her tactical approach and established a formal peace with them.

Court

Elizabeth's court was one of the most splendid in all Europe. As historian

Elizabeth's court was one of the most splendid in all Europe. As historian Mikhail Shcherbatov

Prince Mikhailo Mikhailovich Shcherbatov (russian: Михаи́л Миха́йлович Щерба́тов; 22 July 1733 – 12 December 1790) was a leading ideologue and exponent of the Russian Enlightenment, on the par with Mikhail Lomonosov a ...

stated, the court was "arrayed in cloth of gold, her nobles satisfied with only the most luxurious garments, the most expensive foods, the rarest drinks, that largest number of servants and they applied this standard of lavishness to their dress as well"."The Iron-Fisted Fashionista" Russian Life Nov.-Dec. 2009 by Lev Berdnikov, pg. 54 A great number of silver and gold objects were produced, the most the country had seen thus far in its history. It was common to order over a thousand bottles of French champagnes and wines to be served at one event and to serve pineapple

The pineapple (''Ananas comosus'') is a tropical plant with an edible fruit; it is the most economically significant plant in the family Bromeliaceae. The pineapple is indigenous to South America, where it has been cultivated for many centuri ...

s at all receptions, despite the difficulty of procuring the fruit in such quantities.

French plays quickly became the most popular and often were performed twice a week. In tandem, music became very important. Many attribute its popularity to Elizabeth's supposed husband, the "Emperor of the Night", Alexei Razumovsky, who reportedly relished music. Elizabeth spared no expense in importing leading musical talents from Germany, France, and Italy. She reportedly owned 15,000 dresses, several thousand pairs of shoes and a seemingly unlimited number of stockings.

Attractive in her youth and vain as an adult, Elizabeth passed various decrees intended to make herself stand out: she issued an edict

An edict is a decree or announcement of a law, often associated with monarchism, but it can be under any official authority. Synonyms include "dictum" and "pronouncement".

''Edict'' derives from the Latin edictum.

Notable edicts

* Telepinu Pro ...

against anyone wearing the same hairstyle, dress, or accessory as the Empress. One woman accidentally wore the same item as the Empress and was lashed across the face for it.'The Iron-Fisted Fashionista' Russian Life Nov.-

Dec. 2009 by Lev Berdnikov, pg. 59 Another law required French fabric salesmen to sell to the Empress first, and those who disregarded that law were arrested. One famous story exemplifying her vanity is that once Elizabeth got a bit of powder in her hair and was unable to remove it except by cutting a patch of her hair. She made all of the court ladies cut patches out of their hair too, which they did "with tears in their eyes". This aggressive vanity became a tenet of the court throughout her reign, particularly as she grew older. According to historian Tamara Talbot Rice, "Later in life her outbursts of anger were directed either against people who were thought to have endangered Russia's security or against women whose beauty rivaled her own".

Despite her volatile and often violent reactions to others regarding her appearance, Elizabeth was ebullient in most other matters, particularly when it came to court entertainment. It was reported that she threw two balls a week; one would be a large event with an average of 800 guests in attendance, most of whom were the nation's leading merchants, members of the lower nobility and guards stationed in and around the city of the event. The other ball was a much smaller affair reserved for her closest friends and members of the highest echelons of nobility. The smaller gatherings began as masked balls, but evolved into the famous metamorphoses balls by 1744. At these metamorphoses balls, guests were expected to dress as the opposite sex, with Elizabeth often dressing up as Cossack or carpenter in honour of her father. Costumes not permitted at the event were those of pilgrims and harlequins, which she considered profane and indecent respectively. Most courtiers thoroughly disliked the balls, as most guests by decree looked ridiculous, but Elizabeth adored them; as Catherine the Great's advisor Potemkin posited, this was because she was "the only woman who looked truly fine and completely a man.... As she was tall and possessed a powerful body, male attire suited her". Kazimierz Waliszewski

Kazimierz Klemens Waliszewski (1849–1935) was a Polish author of history who wrote primarily about Russian history. He studied in Warsaw and Paris.

Background

Waliszewski was born in Gole, in Congress Poland. He wrote detailed, scholarly wor ...

noted that Elizabeth had beautiful legs, and loved to wear male attire because of the tight trousers.Kazimierz Waliszewski "La Dernière Des Romanov, Élisabeth Ire, Impératrice De Russie, 1741–1762". Plon-Nourrit et cie, 1902

Though the balls were by far her most personally beloved and lavish events, Elizabeth often threw children's birthday parties and wedding receptions for those affiliated with her Court, going so far as to provide dowries

A dowry is a payment, such as property or money, paid by the bride's family to the groom or his family at the time of marriage. Dowry contrasts with the related concepts of bride price and dower. While bride price or bride service is a payment b ...

for each of her ladies-in-waiting.

Death

In the late 1750s, Elizabeth's health started to decline. She suffered a series ofdizzy spell

Orthostatic hypotension, also known as postural hypotension, is a medical condition wherein a person's blood pressure drops when standing up or sitting down. Primary orthostatic hypertension is also often referred to as neurogenic orthostatic hyp ...

s and refused to take the

medication she had been prescribed. The Empress forbade the word "death" in her presence until she suffered a stroke on 24 December 1761 (O.S.). Knowing that she was dying, Elizabeth used her last remaining strength to make her confession, to recite with her confessor the prayer for the dying, and to say farewell to the few people who wished to be with her, including Peter and Catherine and Counts Alexei and Kirill Razumovsky

Count Kirill Grigoryevich Razumovski, anglicized as Cyril Grigoryevich Razumovski (russian: Кирилл Григорьевич Разумовский, uk, Кирило Григорович Розумовський ''Kyrylo Hryhorovych Rozumovs ...

.

The Empress died the next day, Orthodox Christmas, 1761. For her lying in state, she was dressed in a shimmering silver dress. It was said that she was beautiful in death as she had been in life. She was buried in the Peter and Paul Cathedral in Saint Petersburg on 3 February 1762 (O.S.) six weeks after her lying in state.

Ancestry

See also

*Tsars of Russia family tree

The following is a family tree of the monarchs of Russia.

Rurik dynasty

Romanov dynasty

Gallery

File:Ruriks.jpg,

File:Romanov f ...

References

Works cited

* * * * * * * * * *Further reading

External links

* – Historical reconstruction "The Romanovs". StarMedia. Babich-Design (Russia, 2013) {{DEFAULTSORT:Elizabeth Of Russia 1709 births 1762 deaths 18th-century Russian monarchs 18th-century women from the Russian Empire Royalty from Moscow Russian empresses regnant House of Romanov Eastern Orthodox monarchs Burials at Saints Peter and Paul Cathedral, Saint Petersburg 18th-century women rulers Leaders who took power by coup People of the Silesian Wars Daughters of Russian emperors Recipients of the Order of the White Eagle (Poland)