evo-devo on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Evolutionary developmental biology, informally known as evo-devo, is a field of biological research that compares the developmental processes of different

Evolutionary developmental biology, informally known as evo-devo, is a field of biological research that compares the developmental processes of different

A

A

From the early 19th century through most of the 20th century,

From the early 19th century through most of the 20th century,  In 1917,

In 1917,

In 1961,

In 1961,

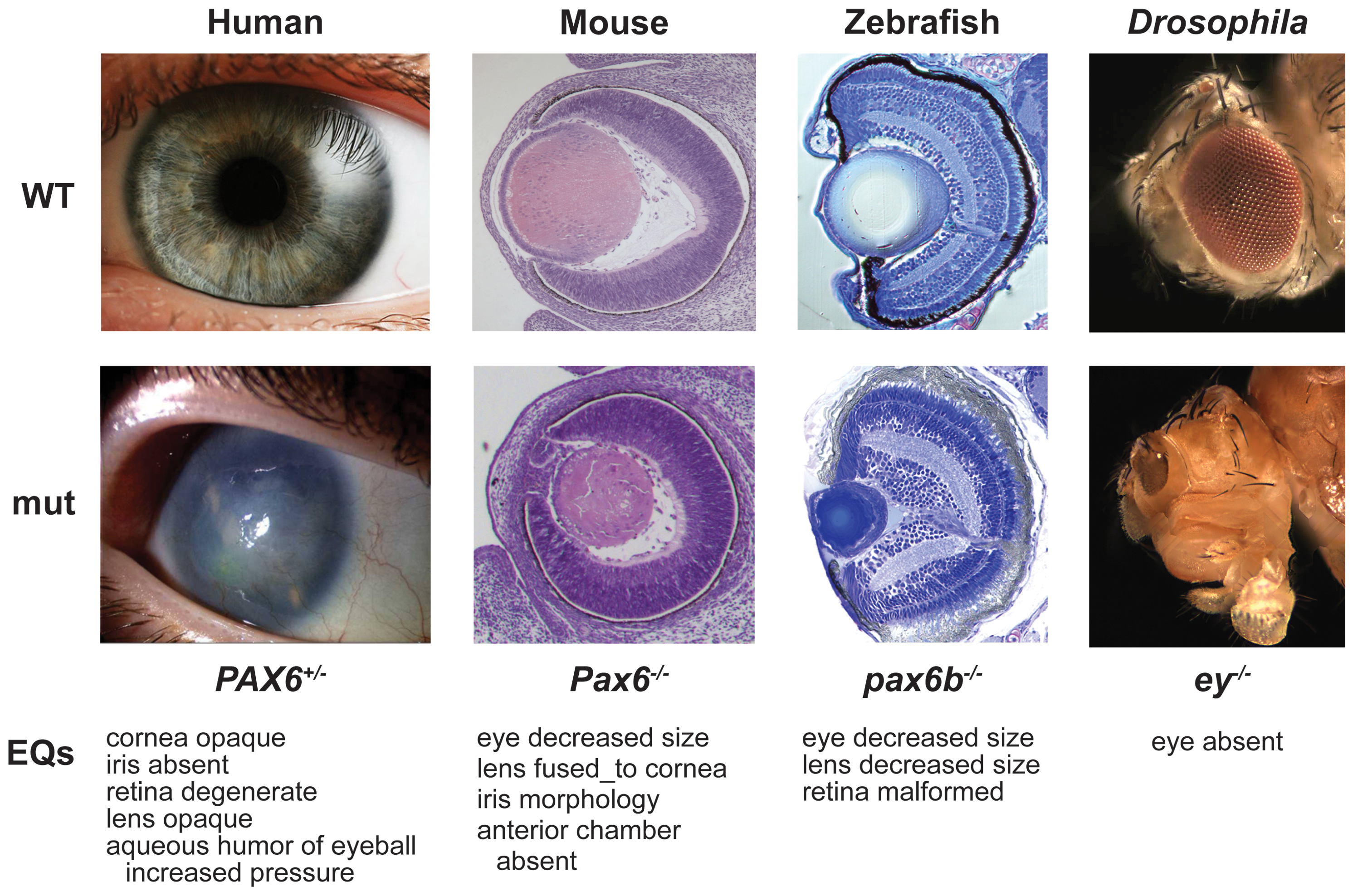

Using such a technique, in 1994 Walter Gehring found that the '' pax-6'' gene, vital for forming the eyes of fruit flies, exactly matches an eye-forming gene in mice and humans. The same gene was quickly found in many other groups of animals, such as

Using such a technique, in 1994 Walter Gehring found that the '' pax-6'' gene, vital for forming the eyes of fruit flies, exactly matches an eye-forming gene in mice and humans. The same gene was quickly found in many other groups of animals, such as

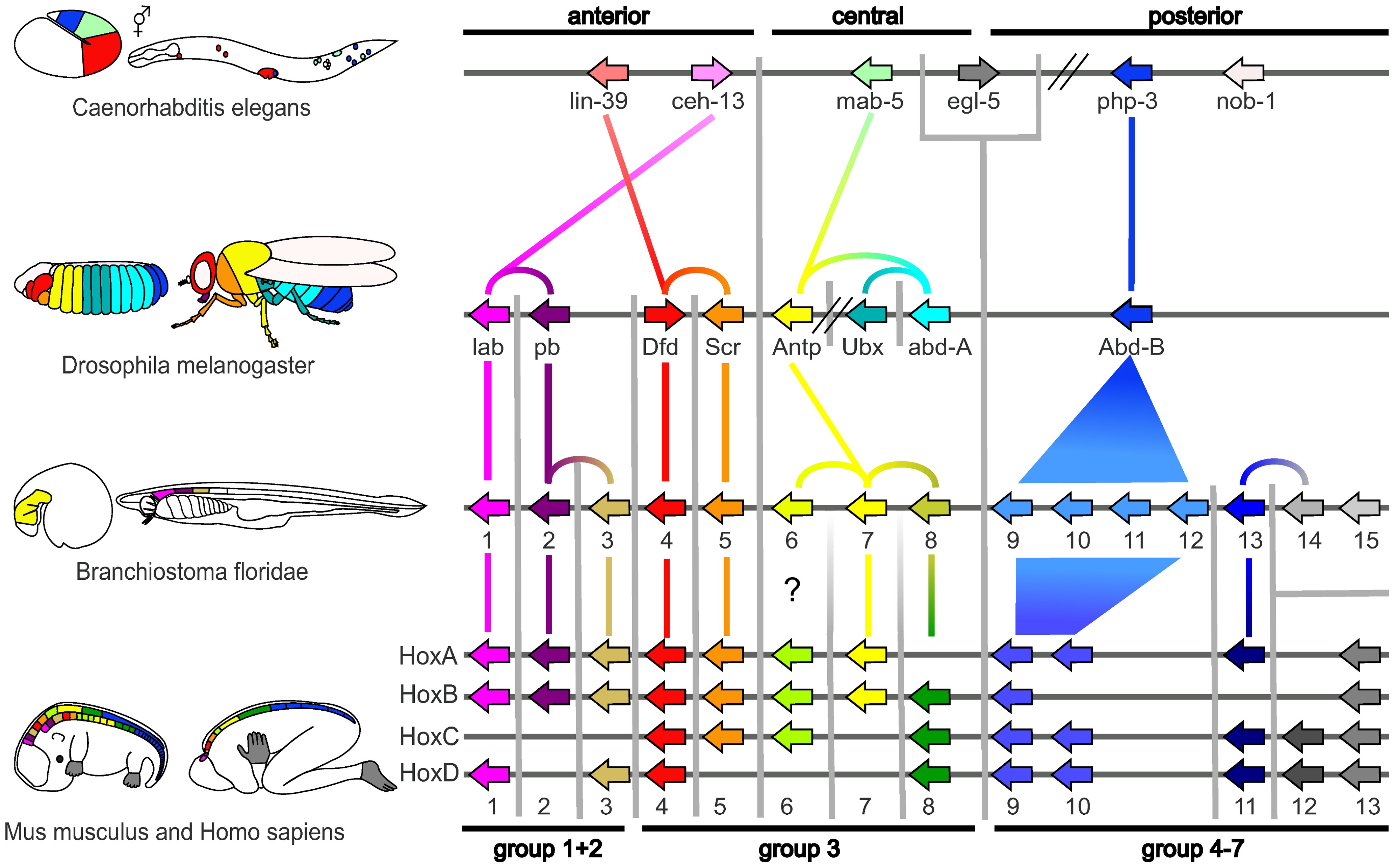

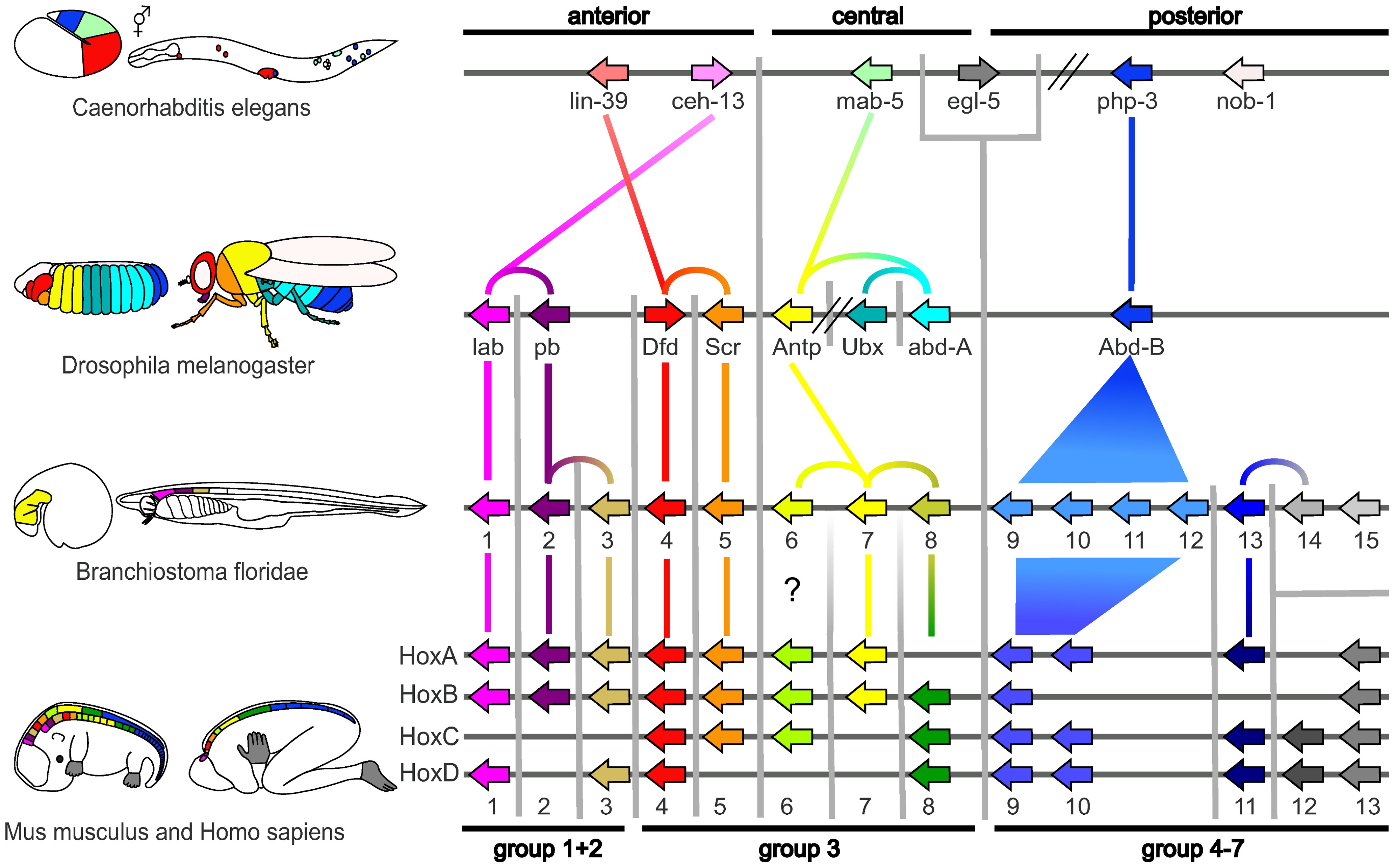

A small fraction of the genes in an organism's genome control the organism's development. These genes are called the developmental-genetic toolkit. They are highly conserved among

A small fraction of the genes in an organism's genome control the organism's development. These genes are called the developmental-genetic toolkit. They are highly conserved among

The protein products of the regulatory toolkit are reused not by duplication and modification, but by a complex mosaic of pleiotropy, being applied unchanged in many independent developmental processes, giving pattern to many dissimilar body structures. The loci of these pleiotropic toolkit genes have large, complicated and modular

The protein products of the regulatory toolkit are reused not by duplication and modification, but by a complex mosaic of pleiotropy, being applied unchanged in many independent developmental processes, giving pattern to many dissimilar body structures. The loci of these pleiotropic toolkit genes have large, complicated and modular  Such a cascading regulatory network has been studied in detail in the development of the fruit fly embryo. The young embryo is oval in shape, like a

Such a cascading regulatory network has been studied in detail in the development of the fruit fly embryo. The young embryo is oval in shape, like a  The Bicoid, Hunchback and Caudal proteins in turn regulate the transcription of gap genes such as ''giant'', ''knirps'', ''Krüppel'', and ''tailless'' in a striped pattern, creating the first level of structures that will become segments. The proteins from these in turn control the pair-rule genes, which in the next stage set up 7 bands across the embryo's long axis. Finally, the segment polarity genes such as '' engrailed'' split each of the 7 bands into two, creating 14 future segments.

This process explains the accurate conservation of toolkit gene sequences, which has resulted in deep homology and functional equivalence of toolkit proteins in dissimilar animals (seen, for example, when a mouse protein controls fruit fly development). The interactions of transcription factors and cis-regulatory elements, or of signalling proteins and receptors, become locked in through multiple usages, making almost any mutation deleterious and hence eliminated by natural selection.

The mechanism that sets up every

The Bicoid, Hunchback and Caudal proteins in turn regulate the transcription of gap genes such as ''giant'', ''knirps'', ''Krüppel'', and ''tailless'' in a striped pattern, creating the first level of structures that will become segments. The proteins from these in turn control the pair-rule genes, which in the next stage set up 7 bands across the embryo's long axis. Finally, the segment polarity genes such as '' engrailed'' split each of the 7 bands into two, creating 14 future segments.

This process explains the accurate conservation of toolkit gene sequences, which has resulted in deep homology and functional equivalence of toolkit proteins in dissimilar animals (seen, for example, when a mouse protein controls fruit fly development). The interactions of transcription factors and cis-regulatory elements, or of signalling proteins and receptors, become locked in through multiple usages, making almost any mutation deleterious and hence eliminated by natural selection.

The mechanism that sets up every

Evolutionary developmental biology, informally known as evo-devo, is a field of biological research that compares the developmental processes of different

Evolutionary developmental biology, informally known as evo-devo, is a field of biological research that compares the developmental processes of different organism

An organism is any life, living thing that functions as an individual. Such a definition raises more problems than it solves, not least because the concept of an individual is also difficult. Many criteria, few of them widely accepted, have be ...

s to infer how developmental processes evolved

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

.

The field grew from 19th-century beginnings, where embryology

Embryology (from Ancient Greek, Greek ἔμβρυον, ''embryon'', "the unborn, embryo"; and -λογία, ''-logy, -logia'') is the branch of animal biology that studies the Prenatal development (biology), prenatal development of gametes (sex ...

faced a mystery: zoologists

This is a list of notable zoologists who have published names of new taxa under the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature.

A

* Abe – Tokiharu Abe (1911–1996)

* Abeille de Perrin, Ab. – Elzéar Abeille de Perrin (1843–1910)

* ...

did not know how embryonic development

In developmental biology, animal embryonic development, also known as animal embryogenesis, is the developmental stage of an animal embryo. Embryonic development starts with the fertilization of an egg cell (ovum) by a sperm, sperm cell (spermat ...

was controlled at the molecular level. Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

noted that having similar embryos implied common ancestry, but little progress was made until the 1970s. Then, recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA (rDNA) molecules are DNA molecules formed by laboratory methods of genetic recombination (such as molecular cloning) that bring together genetic material from multiple sources, creating sequences that would not otherwise be fo ...

technology at last brought embryology together with molecular genetics

Molecular genetics is a branch of biology that addresses how differences in the structures or expression of DNA molecules manifests as variation among organisms. Molecular genetics often applies an "investigative approach" to determine the st ...

. A key early discovery was that of homeotic genes that regulate development in a wide range of eukaryote

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

s.

The field is composed of multiple core evolutionary concepts. One is deep homology, the finding that dissimilar organs such as the eyes of insect

Insects (from Latin ') are Hexapoda, hexapod invertebrates of the class (biology), class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (Insect morphology#Head, head, ...

s, vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

s and cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan Taxonomic rank, class Cephalopoda (Greek language, Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral symm ...

molluscs, long thought to have evolved separately, are controlled by similar genes such as '' pax-6'', from the evo-devo gene toolkit. These genes are ancient, being highly conserved among phyla

Phyla, the plural of ''phylum'', may refer to:

* Phylum, a biological taxon between Kingdom and Class

* by analogy, in linguistics, a large division of possibly related languages, or a major language family which is not subordinate to another

Phy ...

; they generate the patterns in time and space which shape the embryo, and ultimately form the body plan

A body plan, (), or ground plan is a set of morphology (biology), morphological phenotypic trait, features common to many members of a phylum of animals. The vertebrates share one body plan, while invertebrates have many.

This term, usually app ...

of the organism. Another is that species do not differ much in their structural genes, such as those coding for enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

s; what does differ is the way that gene expression is regulated by the toolkit genes. These genes are reused, unchanged, many times in different parts of the embryo and at different stages of development, forming a complex cascade of control, switching other regulatory genes as well as structural genes on and off in a precise pattern. This multiple pleiotropic reuse explains why these genes are highly conserved, as any change would have many adverse consequences which natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

would oppose.

New morphological features and ultimately new species are produced by variations in the toolkit, either when genes are expressed in a new pattern, or when toolkit genes acquire additional functions. Another possibility is the neo-Lamarckian theory that epigenetic changes are later consolidated at gene level, something that may have been important early in the history of multicellular life.

History

Early theories

Philosophers began to think about how animals acquired form in the womb inclassical antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

. Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

asserts in his ''Physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

'' treatise that according to Empedocles

Empedocles (; ; , 444–443 BC) was a Ancient Greece, Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is known best for originating the Cosmogony, cosmogonic theory of the four cla ...

, order "spontaneously" appears in the developing embryo. In his ''The Parts of Animals

''Parts of Animals'' (or ''On the Parts of Animals''; Ancient Greek, Greek Περὶ ζῴων μορίων; Latin ''De Partibus Animalium'') is one of Aristotle's major Aristotle's biology, texts on biology. It was written around 350 BC. The whole ...

'' treatise, he argues that Empedocles' theory was wrong. In Aristotle's account, Empedocles stated that the vertebral column

The spinal column, also known as the vertebral column, spine or backbone, is the core part of the axial skeleton in vertebrates. The vertebral column is the defining and eponymous characteristic of the vertebrate. The spinal column is a segmente ...

is divided into vertebrae because, as it happens, the embryo twists about and snaps the column into pieces. Aristotle argues instead that the process has a predefined goal: that the "seed" that develops into the embryo began with an inbuilt "potential" to become specific body parts, such as vertebrae. Further, each sort of animal gives rise to animals of its own kind: humans only have human babies.

Recapitulation

recapitulation theory

The theory of recapitulation, also called the biogenetic law or embryological parallelism—often expressed using Ernst Haeckel's phrase "ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny"—is a historical hypothesis that the development of the embryo of an ...

of evolutionary development was proposed by Étienne Serres in 1824–26, echoing the 1808 ideas of Johann Friedrich Meckel. They argued that the embryos of 'higher' animals went through or recapitulated a series of stages, each of which resembled an animal lower down the great chain of being

The great chain of being is a hierarchical structure of all matter and life, thought by medieval Christianity to have been decreed by God. The chain begins with God and descends through angels, Human, humans, Animal, animals and Plant, plants to ...

. For example, the brain of a human embryo looked first like that of a fish

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic animal, aquatic, Anamniotes, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fish fin, fins and craniate, a hard skull, but lacking limb (anatomy), limbs with digit (anatomy), digits. Fish can ...

, then in turn like that of a reptile

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology), orders: Testudines, Crocodilia, Squamata, and Rhynchocepha ...

, bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

, and mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

before becoming clearly human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are Hominidae, great apes characterized by their Prehistory of nakedness and clothing ...

. The embryologist Karl Ernst von Baer

Karl Ernst Ritter von Baer Edler von Huthorn (; – ) was a Baltic German scientist and explorer. Baer was a naturalist, biologist, geologist, meteorologist, geographer, and is considered a, or the, founding father of embryology. He was a m ...

opposed this, arguing in 1828 that there was no linear sequence as in the great chain of being, based on a single body plan

A body plan, (), or ground plan is a set of morphology (biology), morphological phenotypic trait, features common to many members of a phylum of animals. The vertebrates share one body plan, while invertebrates have many.

This term, usually app ...

, but a process of epigenesis in which structures differentiate. Von Baer instead recognized four distinct animal body plan

A body plan, (), or ground plan is a set of morphology (biology), morphological phenotypic trait, features common to many members of a phylum of animals. The vertebrates share one body plan, while invertebrates have many.

This term, usually app ...

s: radiate, like starfish

Starfish or sea stars are Star polygon, star-shaped echinoderms belonging to the class (biology), class Asteroidea (). Common usage frequently finds these names being also applied to brittle star, ophiuroids, which are correctly referred to ...

; molluscan, like clam

Clam is a common name for several kinds of bivalve mollusc. The word is often applied only to those that are deemed edible and live as infauna, spending most of their lives halfway buried in the sand of the sea floor or riverbeds. Clams h ...

s; articulate, like lobster

Lobsters are Malacostraca, malacostracans Decapoda, decapod crustaceans of the family (biology), family Nephropidae or its Synonym (taxonomy), synonym Homaridae. They have long bodies with muscular tails and live in crevices or burrows on th ...

s; and vertebrate, like fish. Zoologists then largely abandoned recapitulation, though Ernst Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; ; 16 February 1834 – 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, natural history, naturalist, eugenics, eugenicist, Philosophy, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biology, marine biologist and artist ...

revived it in 1866.

Evolutionary morphology

embryology

Embryology (from Ancient Greek, Greek ἔμβρυον, ''embryon'', "the unborn, embryo"; and -λογία, ''-logy, -logia'') is the branch of animal biology that studies the Prenatal development (biology), prenatal development of gametes (sex ...

faced a mystery. Animals were seen to develop into adults of widely differing body plan

A body plan, (), or ground plan is a set of morphology (biology), morphological phenotypic trait, features common to many members of a phylum of animals. The vertebrates share one body plan, while invertebrates have many.

This term, usually app ...

, often through similar stages, from the egg, but zoologists knew almost nothing about how embryonic development

In developmental biology, animal embryonic development, also known as animal embryogenesis, is the developmental stage of an animal embryo. Embryonic development starts with the fertilization of an egg cell (ovum) by a sperm, sperm cell (spermat ...

was controlled at the molecular level, and therefore equally little about how developmental processes had evolved. Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

argued that a shared embryonic structure implied a common ancestor. For example, Darwin cited in his 1859 book ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

'' the shrimp

A shrimp (: shrimp (American English, US) or shrimps (British English, UK)) is a crustacean with an elongated body and a primarily Aquatic locomotion, swimming mode of locomotion – typically Decapods belonging to the Caridea or Dendrobranchi ...

-like larva

A larva (; : larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into their next life stage. Animals with indirect development such as insects, some arachnids, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase ...

of the barnacle

Barnacles are arthropods of the subclass (taxonomy), subclass Cirripedia in the subphylum Crustacean, Crustacea. They are related to crabs and lobsters, with similar Nauplius (larva), nauplius larvae. Barnacles are exclusively marine invertebra ...

, whose sessile adults looked nothing like other arthropods

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

; Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

and Cuvier had classified them as mollusc

Mollusca is a phylum of protostome, protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant taxon, extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum ...

s. Darwin also noted Alexander Kowalevsky's finding that the tunicate, too, was not a mollusc, but in its larval stage had a notochord

The notochord is an elastic, rod-like structure found in chordates. In vertebrates the notochord is an embryonic structure that disintegrates, as the vertebrae develop, to become the nucleus pulposus in the intervertebral discs of the verteb ...

and pharyngeal slits which developed from the same germ layers as the equivalent structures in vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

s, and should therefore be grouped with them as chordates

A chordate ( ) is a bilaterian animal belonging to the phylum Chordata ( ). All chordates possess, at some point during their larval or adult stages, five distinctive physical characteristics ( synapomorphies) that distinguish them from ot ...

.

19th century zoology thus converted embryology

Embryology (from Ancient Greek, Greek ἔμβρυον, ''embryon'', "the unborn, embryo"; and -λογία, ''-logy, -logia'') is the branch of animal biology that studies the Prenatal development (biology), prenatal development of gametes (sex ...

into an evolutionary science, connecting phylogeny

A phylogenetic tree or phylogeny is a graphical representation which shows the evolutionary history between a set of species or Taxon, taxa during a specific time.Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, M ...

with homologies between the germ layers of embryos. Zoologists including Fritz Müller

Johann Friedrich Theodor Müller (; 31 March 182221 May 1897), better known as Fritz Müller (), and also as Müller-Desterro, was a German biologist who emigrated to southern Brazil, where he lived in and near the city of Blumenau, Santa Cata ...

proposed the use of embryology to discover phylogenetic relationships between taxa. Müller demonstrated that crustaceans

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of Arthropod, arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquat ...

shared the Nauplius larva, identifying several parasitic species that had not been recognized as crustaceans. Müller also recognized that natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

must act on larvae, just as it does on adults, giving the lie to recapitulation, which would require larval forms to be shielded from natural selection. Two of Haeckel's other ideas about the evolution of development have fared better than recapitulation: he argued in the 1870s that changes in the timing (heterochrony

In evolutionary developmental biology, heterochrony is any genetically controlled difference in the timing, rate, or duration of a Developmental biology, developmental process in an organism compared to its ancestors or other organisms. This lea ...

) and changes in the positioning within the body ( heterotopy) of aspects of embryonic development would drive evolution by changing the shape of a descendant's body compared to an ancestor's. It took a century before these ideas were shown to be correct.

In 1917,

In 1917, D'Arcy Thompson

Sir D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson CB FRS FRSE (2 May 1860 – 21 June 1948) was a Scottish biologist, mathematician and classics scholar. He was a pioneer of mathematical and theoretical biology, travelled on expeditions to the Bering Strait ...

wrote a book on the shapes of animals, showing with simple mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

how small changes to parameter

A parameter (), generally, is any characteristic that can help in defining or classifying a particular system (meaning an event, project, object, situation, etc.). That is, a parameter is an element of a system that is useful, or critical, when ...

s, such as the angles of a gastropod

Gastropods (), commonly known as slugs and snails, belong to a large Taxonomy (biology), taxonomic class of invertebrates within the phylum Mollusca called Gastropoda ().

This class comprises snails and slugs from saltwater, freshwater, and fro ...

's spiral shell, can radically alter an animal's form, though he preferred a mechanical to evolutionary explanation. But without molecular evidence, progress stalled.

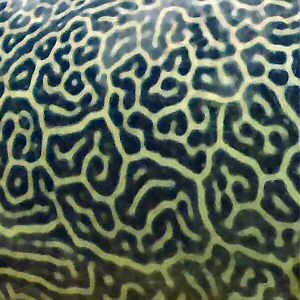

In 1952, Alan Turing

Alan Mathison Turing (; 23 June 1912 – 7 June 1954) was an English mathematician, computer scientist, logician, cryptanalyst, philosopher and theoretical biologist. He was highly influential in the development of theoretical computer ...

published his paper "The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis

"The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis" is an article that the English mathematician Alan Turing wrote in 1952. It describes how patterns in nature, such as stripes and spirals, can arise naturally from a homogeneous, uniform state. The theory, w ...

", on the development of patterns in animals' bodies. He suggested that morphogenesis could be explained by a reaction–diffusion system, a system of reacting chemicals able to diffuse through the body. He modelled catalysed chemical reactions using partial differential equations

In mathematics, a partial differential equation (PDE) is an equation which involves a multivariable function and one or more of its partial derivatives.

The function is often thought of as an "unknown" that solves the equation, similar to how ...

, showing that patterns emerged when the chemical reaction produced both a catalyst

Catalysis () is the increase in rate of a chemical reaction due to an added substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed by the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recycles quick ...

(A) and an inhibitor (B) that slowed down production of A. If A and B then diffused at different rates, A dominated in some places, and B in others. The Russian biochemist Boris Belousov had run experiments with similar results, but was unable to publish them because scientists thought at that time that creating visible order violated the second law of thermodynamics

The second law of thermodynamics is a physical law based on Universal (metaphysics), universal empirical observation concerning heat and Energy transformation, energy interconversions. A simple statement of the law is that heat always flows spont ...

.

The modern synthesis of the early 20th century

In the so-called modern synthesis of the early 20th century, between 1918 and 1930Ronald Fisher

Sir Ronald Aylmer Fisher (17 February 1890 – 29 July 1962) was a British polymath who was active as a mathematician, statistician, biologist, geneticist, and academic. For his work in statistics, he has been described as "a genius who a ...

brought together Darwin's theory of evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

, with its insistence on natural selection, heredity

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic infor ...

, and variation, and Gregor Mendel

Gregor Johann Mendel Order of Saint Augustine, OSA (; ; ; 20 July 1822 – 6 January 1884) was an Austrian Empire, Austrian biologist, meteorologist, mathematician, Augustinians, Augustinian friar and abbot of St Thomas's Abbey, Brno, St. Thom ...

's laws of genetics into a coherent structure for evolutionary biology

Evolutionary biology is the subfield of biology that studies the evolutionary processes such as natural selection, common descent, and speciation that produced the diversity of life on Earth. In the 1930s, the discipline of evolutionary biolo ...

. Biologists assumed that an organism was a straightforward reflection of its component genes: the genes coded for proteins, which built the organism's body. Biochemical pathways (and, they supposed, new species) evolved through mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, ...

s in these genes. It was a simple, clear and nearly comprehensive picture: but it did not explain embryology. Sean B. Carroll has commented that had evo-devo's insights been available, embryology would certainly have played a central role in the synthesis.

The evolutionary embryologist Gavin de Beer anticipated evolutionary developmental biology in his 1930 book '' Embryos and Ancestors'', by showing that evolution could occur by heterochrony

In evolutionary developmental biology, heterochrony is any genetically controlled difference in the timing, rate, or duration of a Developmental biology, developmental process in an organism compared to its ancestors or other organisms. This lea ...

, such as in the retention of juvenile features in the adult. This, de Beer argued, could cause apparently sudden changes in the fossil record

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

, since embryos fossilise poorly. As the gaps in the fossil record had been used as an argument against Darwin's gradualist evolution, de Beer's explanation supported the Darwinian position. However, despite de Beer, the modern synthesis largely ignored embryonic development to explain the form of organisms, since population genetics appeared to be an adequate explanation of how forms evolved.

The lac operon

Jacques Monod

Jacques Lucien Monod (; 9 February 1910 – 31 May 1976) was a French biochemist who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1965, sharing it with François Jacob and André Lwoff "for their discoveries concerning genetic control of e ...

, Jean-Pierre Changeux and François Jacob

François Jacob (; 17 June 1920 – 19 April 2013) was a French biologist who, together with Jacques Monod, originated the idea that control of enzyme levels in all cells occurs through regulation of transcription. He shared the 1965 Nobel ...

discovered the lac operon in the bacterium

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among the ...

''Escherichia coli

''Escherichia coli'' ( )Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. is a gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus '' Escherichia'' that is commonly fo ...

''. It was a cluster of gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

s, arranged in a feedback control loop

A control loop is the fundamental building block of control systems in general and industrial control systems in particular. It consists of the process sensor, the controller function, and the final control element (FCE) which controls the proce ...

so that its products would only be made when "switched on" by an environmental stimulus. One of these products was an enzyme that splits a sugar, lactose; and lactose

Lactose is a disaccharide composed of galactose and glucose and has the molecular formula C12H22O11. Lactose makes up around 2–8% of milk (by mass). The name comes from (Genitive case, gen. ), the Latin word for milk, plus the suffix ''-o ...

itself was the stimulus that switched the genes on. This was a revelation, as it showed for the first time that genes, even in organisms as small as a bacterium, are subject to precise control. The implication was that many other genes were also elaborately regulated.

The birth of evo-devo and a second synthesis

In 1977, a revolution in thinking about evolution and developmental biology began, with the arrival ofrecombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA (rDNA) molecules are DNA molecules formed by laboratory methods of genetic recombination (such as molecular cloning) that bring together genetic material from multiple sources, creating sequences that would not otherwise be fo ...

technology in genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinians, Augustinian ...

, the book ''Ontogeny and Phylogeny'' by Stephen J. Gould and the paper "Evolution and Tinkering" by François Jacob

François Jacob (; 17 June 1920 – 19 April 2013) was a French biologist who, together with Jacques Monod, originated the idea that control of enzyme levels in all cells occurs through regulation of transcription. He shared the 1965 Nobel ...

. Gould laid to rest Haeckel's interpretation of evolutionary embryology, while Jacob set out an alternative theory.

This led to a second synthesis, at last including embryology as well as molecular genetics

Molecular genetics is a branch of biology that addresses how differences in the structures or expression of DNA molecules manifests as variation among organisms. Molecular genetics often applies an "investigative approach" to determine the st ...

, phylogeny, and evolutionary biology to form evo-devo. In 1978, Edward B. Lewis discovered homeotic genes that regulate embryonic development in ''Drosophila

''Drosophila'' (), from Ancient Greek δρόσος (''drósos''), meaning "dew", and φίλος (''phílos''), meaning "loving", is a genus of fly, belonging to the family Drosophilidae, whose members are often called "small fruit flies" or p ...

'' fruit flies, which like all insects are arthropods

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

, one of the major phyla

Phyla, the plural of ''phylum'', may refer to:

* Phylum, a biological taxon between Kingdom and Class

* by analogy, in linguistics, a large division of possibly related languages, or a major language family which is not subordinate to another

Phy ...

of invertebrate animals.

Bill McGinnis quickly discovered homeotic gene sequences, homeobox

A homeobox is a Nucleic acid sequence, DNA sequence, around 180 base pairs long, that regulates large-scale anatomical features in the early stages of embryonic development. Mutations in a homeobox may change large-scale anatomical features of ...

es, in animals in other phyla, in vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

s such as frog

A frog is any member of a diverse and largely semiaquatic group of short-bodied, tailless amphibian vertebrates composing the order (biology), order Anura (coming from the Ancient Greek , literally 'without tail'). Frog species with rough ski ...

s, bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s, and mammals

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three middle e ...

; they were later also found in fungi

A fungus (: fungi , , , or ; or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as one ...

such as yeast

Yeasts are eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms classified as members of the fungus kingdom (biology), kingdom. The first yeast originated hundreds of millions of years ago, and at least 1,500 species are currently recognized. They are est ...

s, and in plant

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with c ...

s. There were evidently strong similarities in the genes that controlled development across all the eukaryote

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

s.

In 1980, Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard and Eric Wieschaus

Eric Francis Wieschaus (born June 8, 1947 in South Bend, Indiana) is an American Evolutionary developmental biology, evolutionary developmental biologist and 1995 Nobel Prize-winner.

Early life

Born in South Bend, Indiana, he attended John Carro ...

described gap genes which help to create the segmentation pattern in fruit fly embryos; they and Lewis won a Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

for their work in 1995.

Later, more specific similarities were discovered: for example, the distal-less gene was found in 1989 to be involved in the development of appendages or limbs in fruit flies, the fins of fish, the wings of chickens, the parapodia of marine annelid

The annelids (), also known as the segmented worms, are animals that comprise the phylum Annelida (; ). The phylum contains over 22,000 extant species, including ragworms, earthworms, and leeches. The species exist in and have adapted to vario ...

worms, the ampullae and siphons of tunicates, and the tube feet

Tube or tubes may refer to:

* Tube (2003 film), ''Tube'' (2003 film), a 2003 Korean film

* "Tubes" (Peter Dale), performer on the Soccer AM#Tubes, Soccer AM television show

* Tube (band), a Japanese rock band

* Tube & Berger, the alias of dance/e ...

of sea urchin

Sea urchins or urchins () are echinoderms in the class (biology), class Echinoidea. About 950 species live on the seabed, inhabiting all oceans and depth zones from the intertidal zone to deep seas of . They typically have a globular body cove ...

s. It was evident that the gene must be ancient, dating back to the last common ancestor of bilateral animals (before the Ediacaran

The Ediacaran ( ) is a geological period of the Neoproterozoic geologic era, Era that spans 96 million years from the end of the Cryogenian Period at 635 Million years ago, Mya to the beginning of the Cambrian Period at 538.8 Mya. It is the last ...

Period, which began some 635 million years ago). Evo-devo had started to uncover the ways that all animal bodies were built during development.

The control of body structure

Deep homology

Roughly spherical eggs of different animals give rise to unique morphologies, from jellyfish to lobsters, butterflies to elephants. Many of these organisms share the same structural genes for bodybuilding proteins like collagen and enzymes, but biologists had expected that each group of animals would have its own rules of development. The surprise of evo-devo is that the shaping of bodies is controlled by a rather small percentage of genes, and that these regulatory genes are ancient, shared by all animals. Thegiraffe

The giraffe is a large Fauna of Africa, African even-toed ungulate, hoofed mammal belonging to the genus ''Giraffa.'' It is the Largest mammals#Even-toed Ungulates (Artiodactyla), tallest living terrestrial animal and the largest ruminant on ...

does not have a gene for a long neck, any more than the elephant

Elephants are the largest living land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant ('' Loxodonta africana''), the African forest elephant (''L. cyclotis''), and the Asian elephant ('' Elephas maximus ...

has a gene for a big body. Their bodies are patterned by a system of switching which causes development of different features to begin earlier or later, to occur in this or that part of the embryo, and to continue for more or less time.

The puzzle of how embryonic development was controlled began to be solved using the fruit fly ''Drosophila melanogaster

''Drosophila melanogaster'' is a species of fly (an insect of the Order (biology), order Diptera) in the family Drosophilidae. The species is often referred to as the fruit fly or lesser fruit fly, or less commonly the "vinegar fly", "pomace fly" ...

'' as a model organism

A model organism is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the workings of other organisms. Mo ...

. The step-by-step control of its embryogenesis was visualized by attaching fluorescent dyes of different colours to specific types of protein made by genes expressed in the embryo. A dye such as green fluorescent protein, originally from a jellyfish, was typically attached to an antibody

An antibody (Ab) or immunoglobulin (Ig) is a large, Y-shaped protein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which is used by the immune system to identify and neutralize antigens such as pathogenic bacteria, bacteria and viruses, includin ...

specific to a fruit fly protein, forming a precise indicator of where and when that protein appeared in the living embryo.

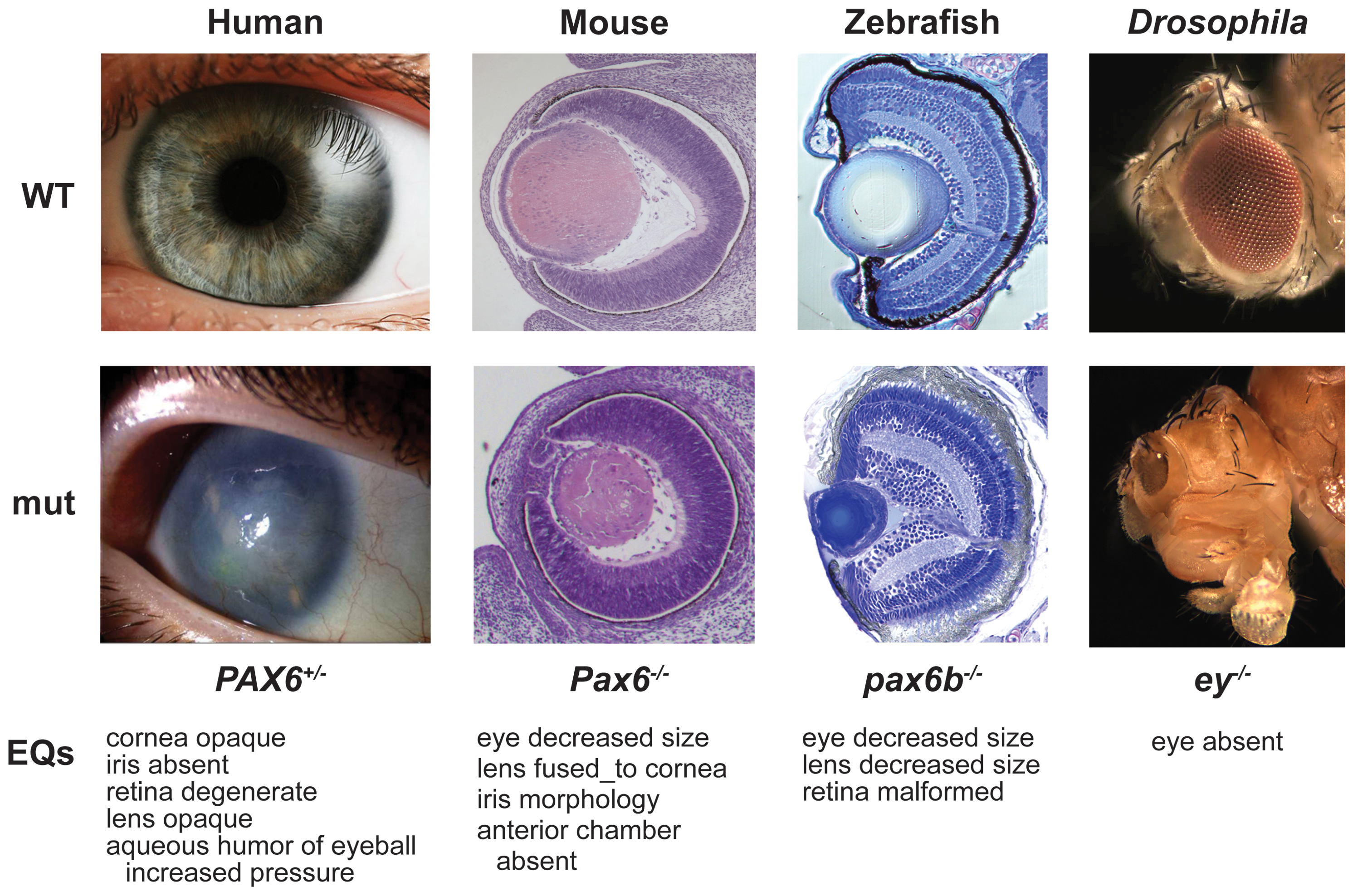

Using such a technique, in 1994 Walter Gehring found that the '' pax-6'' gene, vital for forming the eyes of fruit flies, exactly matches an eye-forming gene in mice and humans. The same gene was quickly found in many other groups of animals, such as

Using such a technique, in 1994 Walter Gehring found that the '' pax-6'' gene, vital for forming the eyes of fruit flies, exactly matches an eye-forming gene in mice and humans. The same gene was quickly found in many other groups of animals, such as squid

A squid (: squid) is a mollusc with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight cephalopod limb, arms, and two tentacles in the orders Myopsida, Oegopsida, and Bathyteuthida (though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also ...

, a cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan Taxonomic rank, class Cephalopoda (Greek language, Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral symm ...

mollusc

Mollusca is a phylum of protostome, protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant taxon, extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum ...

. Biologists including Ernst Mayr

Ernst Walter Mayr ( ; ; 5 July 1904 – 3 February 2005) was a German-American evolutionary biologist. He was also a renowned Taxonomy (biology), taxonomist, tropical explorer, ornithologist, Philosophy of biology, philosopher of biology, and ...

had believed that eyes had arisen in the animal kingdom at least 40 times, as the anatomy of different types of eye varies widely. For example, the fruit fly's compound eye

A compound eye is a Eye, visual organ found in arthropods such as insects and crustaceans. It may consist of thousands of ommatidium, ommatidia, which are tiny independent photoreception units that consist of a cornea, lens (anatomy), lens, and p ...

is made of hundreds of small lensed structures ( ommatidia); the human eye

The human eye is a sensory organ in the visual system that reacts to light, visible light allowing eyesight. Other functions include maintaining the circadian rhythm, and Balance (ability), keeping balance.

The eye can be considered as a living ...

has a blind spot where the optic nerve

In neuroanatomy, the optic nerve, also known as the second cranial nerve, cranial nerve II, or simply CN II, is a paired cranial nerve that transmits visual system, visual information from the retina to the brain. In humans, the optic nerve i ...

enters the eye, and the nerve fibres run over the surface of the retina

The retina (; or retinas) is the innermost, photosensitivity, light-sensitive layer of tissue (biology), tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some Mollusca, molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focus (optics), focused two-dimensional ...

, so light has to pass through a layer of nerve fibres before reaching the detector cells in the retina, so the structure is effectively "upside-down"; in contrast, the cephalopod eye has the retina, then a layer of nerve fibres, then the wall of the eye "the right way around". The evidence of ''pax-6'', however, was that the same genes controlled the development of the eyes of all these animals, suggesting that they all evolved from a common ancestor. Ancient genes had been conserved through millions of years of evolution to create dissimilar structures for similar functions, demonstrating deep homology between structures once thought to be purely analogous. This notion was later extended to the evolution of embryogenesis

An embryo ( ) is the initial stage of development for a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male ...

and has caused a radical revision of the meaning of homology in evolutionary biology.

Gene toolkit

phyla

Phyla, the plural of ''phylum'', may refer to:

* Phylum, a biological taxon between Kingdom and Class

* by analogy, in linguistics, a large division of possibly related languages, or a major language family which is not subordinate to another

Phy ...

, meaning that they are ancient and very similar in widely separated groups of animals. Differences in deployment of toolkit genes affect the body plan and the number, identity, and pattern of body parts. Most toolkit genes are parts of signalling pathways: they encode transcription factor

In molecular biology, a transcription factor (TF) (or sequence-specific DNA-binding factor) is a protein that controls the rate of transcription (genetics), transcription of genetics, genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA, by binding t ...

s, cell adhesion

Cell adhesion is the process by which cells interact and attach to neighbouring cells through specialised molecules of the cell surface. This process can occur either through direct contact between cell surfaces such as Cell_junction, cell junc ...

proteins, cell surface receptor

Receptor may refer to:

* Sensory receptor, in physiology, any neurite structure that, on receiving environmental stimuli, produces an informative nerve impulse

*Receptor (biochemistry), in biochemistry, a protein molecule that receives and respond ...

proteins and signalling ligands

In coordination chemistry, a ligand is an ion or molecule with a functional group that binds to a central metal atom to form a coordination complex. The bonding with the metal generally involves formal donation of one or more of the ligand's ...

that bind to them, and secreted morphogens

A morphogen is a substance whose non-uniform distribution governs the Natural patterns, pattern of tissue development in the process of morphogenesis or pattern formation, one of the core processes of developmental biology, establishing positio ...

that diffuse through the embryo. All of these help to define the fate of undifferentiated cells in the embryo. Together, they generate the patterns in time and space which shape the embryo, and ultimately form the body plan

A body plan, (), or ground plan is a set of morphology (biology), morphological phenotypic trait, features common to many members of a phylum of animals. The vertebrates share one body plan, while invertebrates have many.

This term, usually app ...

of the organism. Among the most important toolkit genes are the ''Hox'' genes. These transcription factors contain the homeobox

A homeobox is a Nucleic acid sequence, DNA sequence, around 180 base pairs long, that regulates large-scale anatomical features in the early stages of embryonic development. Mutations in a homeobox may change large-scale anatomical features of ...

protein-binding DNA motif, also found in other toolkit genes, and create the basic pattern of the body along its front-to-back axis.

Hox genes determine where repeating parts, such as the many vertebra

Each vertebra (: vertebrae) is an irregular bone with a complex structure composed of bone and some hyaline cartilage, that make up the vertebral column or spine, of vertebrates. The proportions of the vertebrae differ according to their spina ...

e of snake

Snakes are elongated limbless reptiles of the suborder Serpentes (). Cladistically squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales much like other members of the group. Many species of snakes have s ...

s, will grow in a developing embryo or larva. ''Pax-6'', already mentioned, is a classic toolkit gene. Although other toolkit genes are involved in establishing the plant bodyplan

A body plan, (), or ground plan is a set of morphological features common to many members of a phylum of animals. The vertebrates share one body plan, while invertebrates have many.

This term, usually applied to animals, envisages a "blueprin ...

, homeobox

A homeobox is a Nucleic acid sequence, DNA sequence, around 180 base pairs long, that regulates large-scale anatomical features in the early stages of embryonic development. Mutations in a homeobox may change large-scale anatomical features of ...

genes are also found in plants, implying they are common to all eukaryote

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

s.

The embryo's regulatory networks

The protein products of the regulatory toolkit are reused not by duplication and modification, but by a complex mosaic of pleiotropy, being applied unchanged in many independent developmental processes, giving pattern to many dissimilar body structures. The loci of these pleiotropic toolkit genes have large, complicated and modular

The protein products of the regulatory toolkit are reused not by duplication and modification, but by a complex mosaic of pleiotropy, being applied unchanged in many independent developmental processes, giving pattern to many dissimilar body structures. The loci of these pleiotropic toolkit genes have large, complicated and modular cis-regulatory element

''Cis''-regulatory elements (CREs) or ''cis''-regulatory modules (CRMs) are regions of non-coding DNA which regulate the transcription of neighboring genes. CREs are vital components of genetic regulatory networks, which in turn control morpho ...

s. For example, while a non-pleiotropic rhodopsin

Rhodopsin, also known as visual purple, is a protein encoded by the ''RHO'' gene and a G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR). It is a light-sensitive receptor protein that triggers visual phototransduction in rod cells. Rhodopsin mediates dim ...

gene in the fruit fly has a cis-regulatory element just a few hundred base pair

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA ...

s long, the pleiotropic eyeless cis-regulatory region contains 6 cis-regulatory elements in over 7000 base pairs. The regulatory networks involved are often very large. Each regulatory protein controls "scores to hundreds" of cis-regulatory elements. For instance, 67 fruit fly transcription factors controlled on average 124 target genes each. All this complexity enables genes involved in the development of the embryo to be switched on and off at exactly the right times and in exactly the right places. Some of these genes are structural, directly forming enzymes, tissues and organs of the embryo. But many others are themselves regulatory genes, so what is switched on is often a precisely-timed cascade of switching, involving turning on one developmental process after another in the developing embryo.

rugby ball

A rugby ball is an elongated ellipsoidal ball used in both codes of rugby football. Its measurements and weight are specified by World Rugby and the Rugby League International Federation, the governing bodies for both codes, rugby union and rugby ...

. A small number of genes produce messenger RNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is created during the ...

s that set up concentration gradients along the long axis of the embryo. In the early embryo, the '' bicoid'' and ''hunchback'' genes are at high concentration near the anterior end, and give pattern to the future head and thorax; the ''caudal'' and '' nanos'' genes are at high concentration near the posterior end, and give pattern to the hindmost abdominal segments. The effects of these genes interact; for instance, the Bicoid protein blocks the translation of ''caudal'' messenger RNA, so the Caudal protein concentration becomes low at the anterior end. Caudal later switches on genes which create the fly's hindmost segments, but only at the posterior end where it is most concentrated.

animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Biology, biological Kingdom (biology), kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, ...

's front-back axis is the same, implying a common ancestor. There is a similar mechanism for the back-belly axis for bilateria

Bilateria () is a large clade of animals characterised by bilateral symmetry during embryonic development. This means their body plans are laid around a longitudinal axis with a front (or "head") and a rear (or "tail") end, as well as a left� ...

n animals, but it is reversed between arthropod

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

s and vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

s. Another process, gastrulation

Gastrulation is the stage in the early embryonic development of most animals, during which the blastula (a single-layered hollow sphere of cells), or in mammals, the blastocyst, is reorganized into a two-layered or three-layered embryo known as ...

of the embryo, is driven by Myosin II molecular motors, which are not conserved across species. The process may have been started by movements of sea water in the environment, later replaced by the evolution of tissue movements in the embryo.

The origins of novelty

Among the more surprising and, perhaps, counterintuitive (from a neo-Darwinian viewpoint) results of recent research in evolutionary developmental biology is that the diversity ofbody plan

A body plan, (), or ground plan is a set of morphology (biology), morphological phenotypic trait, features common to many members of a phylum of animals. The vertebrates share one body plan, while invertebrates have many.

This term, usually app ...

s and morphology in organisms across many phyla

Phyla, the plural of ''phylum'', may refer to:

* Phylum, a biological taxon between Kingdom and Class

* by analogy, in linguistics, a large division of possibly related languages, or a major language family which is not subordinate to another

Phy ...

are not necessarily reflected in diversity at the level of the sequences of genes, including those of the developmental genetic toolkit and other genes involved in development. Indeed, as John Gerhart and Marc Kirschner have noted, there is an apparent paradox: "where we most expect to find variation, we find conservation, a lack of change". So, if the observed morphological novelty between different clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

s does not come from changes in gene sequences (such as by mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, ...

), where does it come from? Novelty may arise by mutation-driven changes in gene regulation.

Variations in the toolkit

Variations in the toolkit may have produced a large part of the morphological evolution of animals. The toolkit can drive evolution in two ways. A toolkit gene can be expressed in a different pattern, as when the beak of Darwin's large ground-finch was enlarged by the '' BMP'' gene, or when snakes lost their legs as ''distal-less'' became under-expressed or not expressed at all in the places where other reptiles continued to form their limbs. Or, a toolkit gene can acquire a new function, as seen in the many functions of that same gene, ''distal-less'', which controls such diverse structures as the mandible in vertebrates, legs and antennae in the fruit fly, and eyespot pattern inbutterfly

Butterflies are winged insects from the lepidopteran superfamily Papilionoidea, characterized by large, often brightly coloured wings that often fold together when at rest, and a conspicuous, fluttering flight. The oldest butterfly fossi ...

wing

A wing is a type of fin that produces both Lift (force), lift and drag while moving through air. Wings are defined by two shape characteristics, an airfoil section and a planform (aeronautics), planform. Wing efficiency is expressed as lift-to-d ...

s. Given that small changes in toolbox genes can cause significant changes in body structures, they have often enabled the same function convergently or in parallel. ''distal-less'' generates wing patterns in the butterflies '' Heliconius erato'' and '' Heliconius melpomene'', which are Müllerian mimics. In so-called facilitated variation, their wing patterns arose in different evolutionary events, but are controlled by the same genes. Developmental changes can contribute directly to speciation

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which populations evolve to become distinct species. The biologist Orator F. Cook coined the term in 1906 for cladogenesis, the splitting of lineages, as opposed to anagenesis, phyletic evolution within ...

.

Consolidation of epigenetic changes

Evolutionary innovation may sometimes begin in Lamarckian style with epigenetic alterations of gene regulation or phenotype generation, subsequently consolidated by changes at the gene level. Epigenetic changes include modification of DNA by reversible methylation, as well as nonprogrammed remoulding of the organism by physical and other environmental effects due to the inherent plasticity of developmental mechanisms. The biologists Stuart A. Newman and Gerd B. Müller have suggested that organisms early in the history of multicellular life were more susceptible to this second category of epigenetic determination than are modern organisms, providing a basis for early macroevolutionary changes.Developmental bias

Development in specific lineages can be biased either positively, towards a given trajectory or phenotype, or negatively, away from producing certain types of change; either may be absolute (the change is always or never produced) or relative. Evidence for any such direction in evolution is however hard to acquire and can also result from developmental constraints that limit diversification. For example, in thegastropod

Gastropods (), commonly known as slugs and snails, belong to a large Taxonomy (biology), taxonomic class of invertebrates within the phylum Mollusca called Gastropoda ().

This class comprises snails and slugs from saltwater, freshwater, and fro ...

s, the snail-type shell is always built as a tube that grows both in length and in diameter; selection has created a wide variety of shell shapes such as flat spirals, cowries and tall turret spirals within these constraints. Among the centipede

Centipedes (from Neo-Latin , "hundred", and Latin , "foot") are predatory arthropods belonging to the class Chilopoda (Ancient Greek , ''kheilos'', "lip", and Neo-Latin suffix , "foot", describing the forcipules) of the subphylum Myriapoda, ...

s, the Lithobiomorpha always have 15 trunk segments as adults, probably the result of a developmental bias towards an odd number of trunk segments. Another centipede order, the Geophilomorpha

Geophilomorpha is an order of centipedes commonly known as soil centipedes. The name "Geophilomorpha" is from Ancient Greek roots meaning "formed to love the earth." This group is the most diverse centipede order, with 230 genera. These centiped ...

, the number of segments varies in different species between 27 and 191, but the number is always odd, making this an absolute constraint; almost all the odd numbers in that range are occupied by one or another species.

Ecological evolutionary developmental biology

Ecological evolutionary developmental biology, informally known as eco-evo-devo, integrates research from developmental biology andecology

Ecology () is the natural science of the relationships among living organisms and their Natural environment, environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community (ecology), community, ecosystem, and biosphere lev ...

to examine their relationship with evolutionary theory. Researchers study concepts and mechanisms such as developmental plasticity, epigenetic inheritance, genetic assimilation, niche construction and symbiosis

Symbiosis (Ancient Greek : living with, companionship < : together; and ''bíōsis'': living) is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction, between two organisms of different species. The two organisms, termed symbionts, can fo ...

.

See also

* Arthropod head problem *Cell signaling

In biology, cell signaling (cell signalling in British English) is the Biological process, process by which a Cell (biology), cell interacts with itself, other cells, and the environment. Cell signaling is a fundamental property of all Cell (biol ...

* '' Evolution & Development'' (journal)

* Human evolutionary developmental biology

* '' Just So Stories'' (as seen by evolutionary developmental biologists)

* Plant evolutionary developmental biology

* Recapitulation theory

The theory of recapitulation, also called the biogenetic law or embryological parallelism—often expressed using Ernst Haeckel's phrase "ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny"—is a historical hypothesis that the development of the embryo of an ...

Notes

References

Citations

Sources

* * * *External links

* {{Authority control Evolutionary developmental biology Subfields of evolutionary biology Developmental biology Extended evolutionary synthesis