Euphausiidae on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Krill ''(Euphausiids)'' (: krill) are small and exclusively marine

Krill are

Krill are

The life cycle of krill is relatively well understood, despite minor variations in detail from species to species. After krill hatch, they experience several larval stagesŌĆö''nauplius (larva), nauplius'', ''pseudometanauplius'', ''metanauplius'', ''calyptopsis'', and ''furcilia'', each of which divides into sub-stages. The pseudometanauplius stage is exclusive to species that lay their eggs within an ovigerous sac: so-called "sac-spawners". The larvae grow and ecdysis, moult repeatedly as they develop, replacing their rigid exoskeleton when it becomes too small. Smaller animals moult more frequently than larger ones. Yolk reserves within their body nourish the larvae through metanauplius stage.

By the calyptopsis stages cellular differentiation, differentiation has progressed far enough for them to develop a mouth and a digestive tract, and they begin to eat phytoplankton. By that time their yolk reserves are exhausted and the larvae must have reached the photic zone, the upper layers of the ocean where algae flourish. During the furcilia stages, segments with pairs of swimmerets are added, beginning at the frontmost segments. Each new pair becomes functional only at the next moult. The number of segments added during any one of the furcilia stages may vary even within one species depending on environmental conditions. After the final furcilia stage, an immature juvenile emerges in a shape similar to an adult, and subsequently develops gonads and matures sexually.

The life cycle of krill is relatively well understood, despite minor variations in detail from species to species. After krill hatch, they experience several larval stagesŌĆö''nauplius (larva), nauplius'', ''pseudometanauplius'', ''metanauplius'', ''calyptopsis'', and ''furcilia'', each of which divides into sub-stages. The pseudometanauplius stage is exclusive to species that lay their eggs within an ovigerous sac: so-called "sac-spawners". The larvae grow and ecdysis, moult repeatedly as they develop, replacing their rigid exoskeleton when it becomes too small. Smaller animals moult more frequently than larger ones. Yolk reserves within their body nourish the larvae through metanauplius stage.

By the calyptopsis stages cellular differentiation, differentiation has progressed far enough for them to develop a mouth and a digestive tract, and they begin to eat phytoplankton. By that time their yolk reserves are exhausted and the larvae must have reached the photic zone, the upper layers of the ocean where algae flourish. During the furcilia stages, segments with pairs of swimmerets are added, beginning at the frontmost segments. Each new pair becomes functional only at the next moult. The number of segments added during any one of the furcilia stages may vary even within one species depending on environmental conditions. After the final furcilia stage, an immature juvenile emerges in a shape similar to an adult, and subsequently develops gonads and matures sexually.

During the mating season, which varies by species and climate, the male deposits a spermatophore, sperm sack at the female's genital opening (named ''thelycum''). The females can carry several thousand eggs in their ovary, which may then account for as much as one third of the animal's body mass. Krill can have multiple broods in one season, with interbrood intervals lasting on the order of days.

Krill employ two types of spawning mechanism. The 57 species of the genera ''Bentheuphausia'', ''Euphausia'', ''Meganyctiphanes'', ''Thysanoessa'', and ''Thysanopoda'' are "broadcast spawners": the female releases the fertilised eggs into the water, where they usually sink, disperse, and are on their own. These species generally hatch in the nauplius 1 stage, but have recently been discovered to hatch sometimes as metanauplius or even as calyptopis stages. The remaining 29 species of the other genera are "sac spawners", where the female carries the eggs with her, attached to the rearmost pairs of thoracopods until they hatch as metanauplii, although some species like ''Nematoscelis difficilis'' may hatch as nauplius or pseudometanauplius.

During the mating season, which varies by species and climate, the male deposits a spermatophore, sperm sack at the female's genital opening (named ''thelycum''). The females can carry several thousand eggs in their ovary, which may then account for as much as one third of the animal's body mass. Krill can have multiple broods in one season, with interbrood intervals lasting on the order of days.

Krill employ two types of spawning mechanism. The 57 species of the genera ''Bentheuphausia'', ''Euphausia'', ''Meganyctiphanes'', ''Thysanoessa'', and ''Thysanopoda'' are "broadcast spawners": the female releases the fertilised eggs into the water, where they usually sink, disperse, and are on their own. These species generally hatch in the nauplius 1 stage, but have recently been discovered to hatch sometimes as metanauplius or even as calyptopis stages. The remaining 29 species of the other genera are "sac spawners", where the female carries the eggs with her, attached to the rearmost pairs of thoracopods until they hatch as metanauplii, although some species like ''Nematoscelis difficilis'' may hatch as nauplius or pseudometanauplius.

Most krill are swarming animals; the sizes and densities of such swarms vary by species and region. For ''Euphausia superba'', swarms reach 10,000 to 60,000 individuals per cubic metre. Swarming is a defensive mechanism, confusing smaller predators that would like to pick out individuals. In 2012, Gandomi and Alavi presented what appears to be a Swarm intelligence#Krill herd algorithm, successful stochastic algorithm for modelling the behaviour of krill swarms. The algorithm is based on three main factors: " (i) movement induced by the presence of other individuals (ii) foraging activity, and (iii) random diffusion."

Most krill are swarming animals; the sizes and densities of such swarms vary by species and region. For ''Euphausia superba'', swarms reach 10,000 to 60,000 individuals per cubic metre. Swarming is a defensive mechanism, confusing smaller predators that would like to pick out individuals. In 2012, Gandomi and Alavi presented what appears to be a Swarm intelligence#Krill herd algorithm, successful stochastic algorithm for modelling the behaviour of krill swarms. The algorithm is based on three main factors: " (i) movement induced by the presence of other individuals (ii) foraging activity, and (iii) random diffusion."

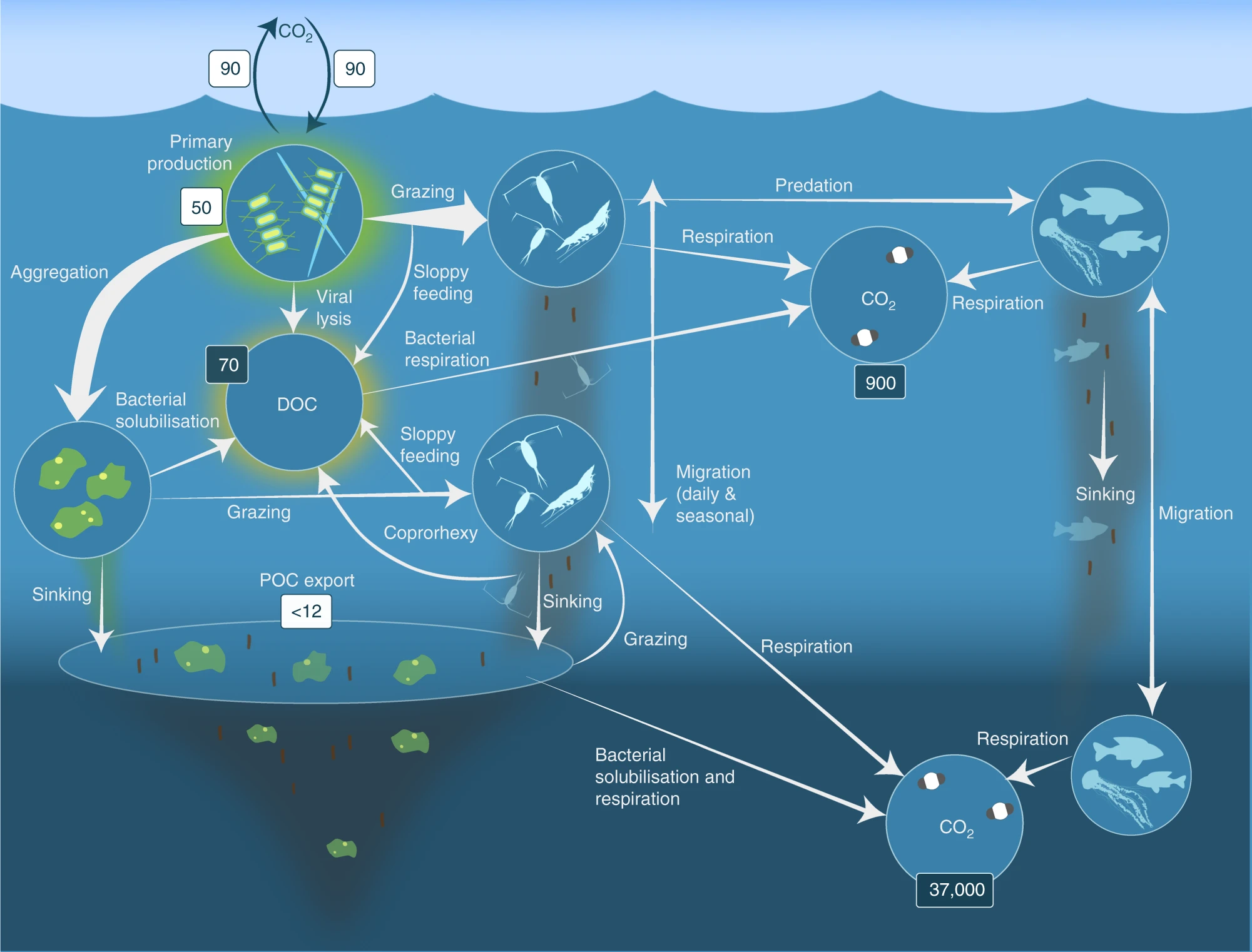

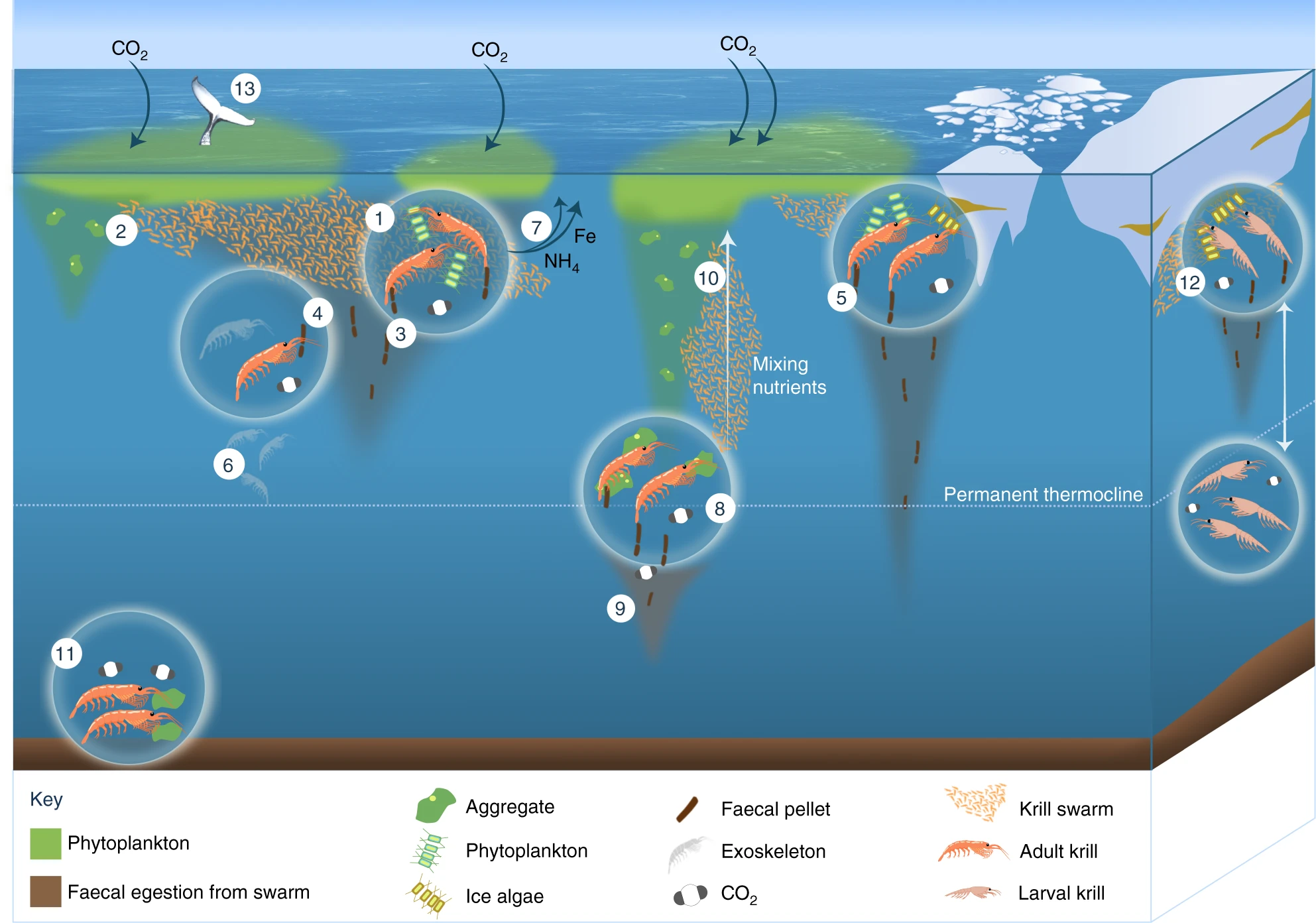

Krill typically follow a diurnality, diurnal Diel vertical migration, vertical migration. It has been assumed that they spend the day at greater depths and rise during the night toward the surface. The deeper they go, the more they reduce their activity, apparently to reduce encounters with predators and to conserve energy. Swimming activity in krill varies with stomach fullness. Sated animals that had been feeding at the surface swim less actively and therefore sink below the mixed layer. As they sink they produce feces which employs a role in the Antarctic carbon cycle. Krill with empty stomachs swim more actively and thus head towards the surface.

Vertical migration may be a 2ŌĆō3 times daily occurrence. Some species (e.g., ''Euphausia superba'', ''E. pacifica'', ''E. hanseni'', ''Pseudeuphausia latifrons'', and ''Thysanoessa spinifera'') form surface swarms during the day for feeding and reproductive purposes even though such behaviour is dangerous because it makes them extremely vulnerable to predators.

Experimental studies using ''Artemia salina'' as a model suggest that the vertical migrations of krill several hundreds of metres, in groups tens of metres deep, could collectively create enough downward jets of water to have a significant effect on ocean mixing.

Dense swarms can elicit a feeding frenzy among fish, birds and mammal predators, especially near the surface. When disturbed, a swarm scatters, and some individuals have even been observed to moult instantly, leaving the exuvia behind as a decoy.

Krill normally swim at a pace of 5ŌĆō10 cm/s (2ŌĆō3 body lengths per second), using their swimmerets for propulsion. Their larger migrations are subject to ocean currents. When in danger, they show an escape reaction called Caridoid escape reaction, lobsteringŌĆöflicking their Caudal (anatomical term), caudal structures, the telson and the uropods, they move backwards through the water relatively quickly, achieving speeds in the range of 10 to 27 body lengths per second, which for large krill such as ''E. superba'' means around . Their swimming performance has led many researchers to classify adult krill as nekton, micro-nektonic life-forms, i.e., small animals capable of individual motion against (weak) currents. Larval forms of krill are generally considered zooplankton.

Krill typically follow a diurnality, diurnal Diel vertical migration, vertical migration. It has been assumed that they spend the day at greater depths and rise during the night toward the surface. The deeper they go, the more they reduce their activity, apparently to reduce encounters with predators and to conserve energy. Swimming activity in krill varies with stomach fullness. Sated animals that had been feeding at the surface swim less actively and therefore sink below the mixed layer. As they sink they produce feces which employs a role in the Antarctic carbon cycle. Krill with empty stomachs swim more actively and thus head towards the surface.

Vertical migration may be a 2ŌĆō3 times daily occurrence. Some species (e.g., ''Euphausia superba'', ''E. pacifica'', ''E. hanseni'', ''Pseudeuphausia latifrons'', and ''Thysanoessa spinifera'') form surface swarms during the day for feeding and reproductive purposes even though such behaviour is dangerous because it makes them extremely vulnerable to predators.

Experimental studies using ''Artemia salina'' as a model suggest that the vertical migrations of krill several hundreds of metres, in groups tens of metres deep, could collectively create enough downward jets of water to have a significant effect on ocean mixing.

Dense swarms can elicit a feeding frenzy among fish, birds and mammal predators, especially near the surface. When disturbed, a swarm scatters, and some individuals have even been observed to moult instantly, leaving the exuvia behind as a decoy.

Krill normally swim at a pace of 5ŌĆō10 cm/s (2ŌĆō3 body lengths per second), using their swimmerets for propulsion. Their larger migrations are subject to ocean currents. When in danger, they show an escape reaction called Caridoid escape reaction, lobsteringŌĆöflicking their Caudal (anatomical term), caudal structures, the telson and the uropods, they move backwards through the water relatively quickly, achieving speeds in the range of 10 to 27 body lengths per second, which for large krill such as ''E. superba'' means around . Their swimming performance has led many researchers to classify adult krill as nekton, micro-nektonic life-forms, i.e., small animals capable of individual motion against (weak) currents. Larval forms of krill are generally considered zooplankton.

The Antarctic krill is an important species in the context of Marine biogeochemical cycles, biogeochemical cycling and in the Antarctic food web. It plays a prominent role in the Southern Ocean because of its ability to Nutrient cycle, cycle nutrients and to feed penguins and Baleen whale, baleen and

The Antarctic krill is an important species in the context of Marine biogeochemical cycles, biogeochemical cycling and in the Antarctic food web. It plays a prominent role in the Southern Ocean because of its ability to Nutrient cycle, cycle nutrients and to feed penguins and Baleen whale, baleen and

"Euphausiacea (Crustacea) of the North Pacific"

''Bulletin of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography''. Volume 6 Number 8, 1955. * Edward Brinton, Brinton, Edward

"Euphausiids of Southeast Asian waters"

''Naga Report'' volume 4, part 5. La Jolla: University of California, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, 1975. * Conway, D. V. P.; White, R. G.; Hugues-Dit-Ciles, J.; Galienne, C. P.; Robins, D. B.:

'', [https://web.archive.org/web/20070927161104/http://www.mba.ac.uk/nmbl/publications/occpub/guide/section13.pdf ''Order'' Euphausiacea], Occasional Publication of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom No. 15, Plymouth, UK, 2003. * Everson, I. (ed.): ''Krill: biology, ecology and fisheries''. Oxford, Blackwell Science; 2000. . * * Mauchline, J.

Euphausiacea: ''Adults''

, Conseil International pour l'Exploration de la Mer, 1971. Identification sheets for adult krill with many line drawings. PDF file, 2 Megabyte, Mb. * Mauchline, J.

Euphausiacea: ''Larvae''

, Conseil International pour l'Exploration de la Mer, 1971. Identification sheets for larval stages of krill with many line drawings. PDF file, 3 Mb. * Tett, P.:

', lecture notes from

from Napier University. * Tett, P.:

Bioluminescence

', lecture notes from the 1999/2000 edition of that same course.

Webcam of Krill Aquarium at Australian Antarctic Division

'Antarctic Energies'

animation by Lisa Roberts {{Authority control Krill, Commercial crustaceans Edible crustaceans Extant Early Cretaceous first appearances Taxa named by James Dwight Dana

crustacean

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthrop ...

s of the order Euphausiacea, found in all of the world's oceans. The name "krill" comes from the Norwegian word ', meaning "small fry of fish", which is also often attributed to species of fish.

Krill are considered an important trophic level

The trophic level of an organism is the position it occupies in a food web. Within a food web, a food chain is a succession of organisms that eat other organisms and may, in turn, be eaten themselves. The trophic level of an organism is the ...

connection near the bottom of the food chain

A food chain is a linear network of links in a food web, often starting with an autotroph (such as grass or algae), also called a producer, and typically ending at an apex predator (such as grizzly bears or killer whales), detritivore (such as ...

. They feed on phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater Aquatic ecosystem, ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek language, Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), mea ...

and, to a lesser extent, zooplankton, and are also the main source of food for many larger animals. In the Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the world ocean, generally taken to be south of 60th parallel south, 60┬░ S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is the seco ...

, one species, the Antarctic krill

Antarctic krill (''Euphausia superba'') is a species of krill found in the Antarctica, Antarctic waters of the Southern Ocean. It is a small, swimming crustacean that lives in large schools, called swarms, sometimes reaching densities of 10,000Ō ...

, makes up an estimated biomass

Biomass is a term used in several contexts: in the context of ecology it means living organisms, and in the context of bioenergy it means matter from recently living (but now dead) organisms. In the latter context, there are variations in how ...

of around 379 million tonne

The tonne ( or ; symbol: t) is a unit of mass equal to 1,000 kilograms. It is a non-SI unit accepted for use with SI. It is also referred to as a metric ton in the United States to distinguish it from the non-metric units of the s ...

s, making it among the species with the largest total biomass. Over half of this biomass is eaten by whales, seals

Seals may refer to:

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, or "true seal"

** Fur seal

* Seal (emblem), a device to impress an emblem, used as a means of a ...

, penguins, seabirds, squid

A squid (: squid) is a mollusc with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight cephalopod limb, arms, and two tentacles in the orders Myopsida, Oegopsida, and Bathyteuthida (though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also ...

, and fish each year. Most krill species display large daily vertical migrations, providing food for predators near the surface at night and in deeper waters during the day.

Krill are fished commercially in the Southern Ocean and in the waters around Japan. The total global harvest amounts to 150,000ŌĆō200,000 tonnes annually, mostly from the Scotia Sea

The Scotia Sea is a sea located at the northern edge of the Southern Ocean at its boundary with the South Atlantic Ocean. It is bounded on the west by the Drake Passage and on the north, east, and south by the Scotia Arc, an undersea ridge and is ...

. Most krill catch is used for aquaculture

Aquaculture (less commonly spelled aquiculture), also known as aquafarming, is the controlled cultivation ("farming") of aquatic organisms such as fish, crustaceans, mollusks, algae and other organisms of value such as aquatic plants (e.g. Nelu ...

and aquarium

An aquarium (: aquariums or aquaria) is a vivarium of any size having at least one transparent side in which aquatic plants or animals are kept and displayed. fishkeeping, Fishkeepers use aquaria to keep fish, invertebrates, amphibians, aquati ...

feeds, as bait

Bait may refer to:

General

* Bait (luring substance), bait as a luring substance

** Fishing bait, bait used for fishing

Film

* ''Bait'' (1950 film), a British crime film by Frank Richardson

* ''Bait'' (1954 film), an American noir film by Hugo ...

in sport fishing

Recreational fishing, also called sport fishing or game fishing, is fishing for leisure, exercise or competition. It can be contrasted with commercial fishing, which is occupational fishing activities done for profit; or subsistence fishing, ...

, or in the pharmaceutical industry. Krill are also used for human consumption in several countries. They are known as in Japan and as ''camarones'' in Spain and the Philippines. In the Philippines, they are also called ''alamang'' and are used to make a salty paste called ''bagoong

''Bago├│ng'' (; ) is a Philippine condiment partially or completely made of either fermented fish (''bago├│ng isd├ó'') or krill or shrimp paste (''bago├│ng alam├Īng'') with salt. The fermentation process also produces fish sauce known as ''pat ...

''.

Krill are also the main food for baleen whale

Baleen whales (), also known as whalebone whales, are marine mammals of the order (biology), parvorder Mysticeti in the infraorder Cetacea (whales, dolphins and porpoises), which use baleen plates (or "whalebone") in their mouths to sieve plankt ...

s, including the blue whale

The blue whale (''Balaenoptera musculus'') is a marine mammal and a baleen whale. Reaching a maximum confirmed length of and weighing up to , it is the largest animal known ever to have existed. The blue whale's long and slender body can ...

.

Taxonomy

Krill belong to the largearthropod

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

subphylum

In zoological nomenclature, a subphylum is a taxonomic rank below the rank of phylum.

The taxonomic rank of " subdivision" in fungi and plant taxonomy is equivalent to "subphylum" in zoological taxonomy. Some plant taxonomists have also used th ...

, the Crustacea

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthrop ...

. The most familiar and largest group of crustaceans, the class

Class, Classes, or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used d ...

Malacostraca

Malacostraca is the second largest of the six classes of pancrustaceans behind insects, containing about 40,000 living species, divided among 16 orders. Its members, the malacostracans, display a great diversity of body forms and include crab ...

, includes the superorder

Order () is one of the eight major hierarchical taxonomic ranks in Linnaean taxonomy. It is classified between family and class. In biological classification, the order is a taxonomic rank used in the classification of organisms and recognized ...

Eucarida

Eucarida is a superorder of the Malacostraca, a class of the crustacean subphylum, comprising the decapods, krill, and Angustidontida. They are characterised by having the carapace fused to all thoracic segments, and by the possession of stalked ...

comprising the three orders, Euphausiacea (krill), Decapoda

The Decapoda or decapods, from Ancient Greek ╬┤╬Ą╬║╬¼Žé (''dek├Īs''), meaning "ten", and ŽĆ╬┐ŽŹŽé (''po├║s''), meaning "foot", is a large order of crustaceans within the class Malacostraca, and includes crabs, lobsters, crayfish, shrimp, a ...

(shrimp, prawns, lobsters, crabs), and the planktonic Amphionidacea

''Amphionides reynaudii'' is a species of caridean shrimp, whose identity and position in the crustacean system remained enigmatic for a long time. It is a small (less than one inch long) planktonic crustacean found throughout the world's tropic ...

.

The order Euphausiacea comprises two families

Family (from ) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictability, structure, and safety as ...

. The more abundant Euphausiidae contains 10 different genera

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family as used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In binomial nomenclature, the genus name forms the first part of the binomial s ...

with a total of 85 species. Of these, the genus ''Euphausia

''Euphausia'' is the largest genus of krill, and is placed in the family Euphausiidae. There are 31 species known in this genus, including Antarctic krill (''Euphausia superba'') and ice krill ('' Euphausia crystallorophias'') from the Southern ...

'' is the largest, with 31 species. The lesser-known family, the Bentheuphausiidae, has only one species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

, '' Bentheuphausia amblyops'', a bathypelagic

The bathypelagic zone or bathyal zone (from Greek ╬▓╬▒╬ĖŽŹŽé (bath├Įs), deep) is the part of the open ocean that extends from a depth of below the ocean surface. It lies between the mesopelagic above and the abyssopelagic below. The bathypela ...

krill living in deep waters below . It is considered the most primitive extant krill species.

Well-known species of the Euphausiidae of commercial krill fisheries include Antarctic krill

Antarctic krill (''Euphausia superba'') is a species of krill found in the Antarctica, Antarctic waters of the Southern Ocean. It is a small, swimming crustacean that lives in large schools, called swarms, sometimes reaching densities of 10,000Ō ...

(''Euphausia superba''), Pacific krill (''E. pacifica'') and Northern krill

Northern krill (''Meganyctiphanes norvegica'') is a species of krill that lives in the North Atlantic Ocean including the Norwegian Sea, North Sea, and parts of the Mediterranean. It is an important component of the zooplankton, providing food fo ...

(''Meganyctiphanes norvegica'').

Phylogeny

, the order Euphausiacea is believed to bemonophyletic

In biological cladistics for the classification of organisms, monophyly is the condition of a taxonomic grouping being a clade ŌĆō that is, a grouping of organisms which meets these criteria:

# the grouping contains its own most recent co ...

due to several unique conserved morphological characteristics (autapomorphy

In phylogenetics, an autapomorphy is a distinctive feature, known as a Synapomorphy, derived trait, that is unique to a given taxon. That is, it is found only in one taxon, but not found in any others or Outgroup (cladistics), outgroup taxa, not ...

) such as its naked filamentous gills and thin thoracopods and by molecular studies.

There have been many theories of the location of the order Euphausiacea. Since the first description of ''Thysanopode tricuspide'' by Henri Milne-Edwards

Henri Milne-Edwards (23 October 1800 ŌĆō 29 July 1885) was a French zoologist.

Biography

Henri Milne-Edwards was the 27th child of William Edwards, an English planter and colonel of the militia in Jamaica and Elisabeth Vaux, a Frenchwoman. Hen ...

in 1830, the similarity of their biramous thoracopods had led zoologists to group euphausiids and Mysidacea in the order Schizopoda

Schizopoda is a former taxonomical classification of a division of the class Malacostraca

Malacostraca is the second largest of the six classes of pancrustaceans behind insects, containing about 40,000 living species, divided among 16 order ...

, which was split by Johan Erik Vesti Boas

Johan Erik Vesti Boas (2 July 1855 ŌĆō 25 January 1935),"Biographical Etymology of Marine Organism Names. B" (biographies of scientists with names beginning "B"), Hans G. Hansson, Tj├żrn├Č Marine Biological Laboratory, University of Gothenburg a ...

in 1883 into two separate orders. Later, William Thomas Calman

William Thomas Calman (29 December 1871 ŌĆō 29 September 1952) was a Scottish zoologist, specialising in the Crustacea. From 1927 to 1936 he was Keeper of Zoology at the British Museum (Natural History) (now the Natural History Museum).

Life

...

(1904) ranked the Mysidacea

The Mysidacea is a group of shrimp-like crustaceans in the superorder Peracarida, comprising the two extant orders Mysida and Lophogastrida

Lophogastrida is an Order (biology), order of malacostracan crustaceans in the superorder Peracarida, c ...

in the superorder Peracarida

The superorder Peracarida is a large group of malacostracan crustaceans, having members in marine, freshwater, and terrestrial habitats. They are chiefly defined by the presence of a brood pouch, or ''marsupium'', formed from thin flattened pla ...

and euphausiids in the superorder Eucarida

Eucarida is a superorder of the Malacostraca, a class of the crustacean subphylum, comprising the decapods, krill, and Angustidontida. They are characterised by having the carapace fused to all thoracic segments, and by the possession of stalked ...

, although even up to the 1930s the order Schizopoda was advocated. It was later also proposed that order Euphausiacea should be grouped with the Penaeidae

Penaeidae is a family of marine crustaceans in the suborder Dendrobranchiata, which are often referred to as penaeid shrimp or penaeid prawns. The Penaeidae contain many species of economic importance, such as the tiger prawn, whiteleg shrimp, ...

(family of prawns) in the Decapoda based on developmental similarities, as noted by Robert Gurney

Robert Gurney (31 July 1879 ŌĆō 5 March 1950) was a British zoologist from the Gurney family, most famous for his monographs on ''British Freshwater Copepoda'' (1931ŌĆō1933) and the ''Larvae of Decapod Crustacea'' (1942). He was not affiliated ...

and Isabella Gordon

Isabella Gordon OBE Zoological Society of London, FZS Linnean Society of London, FLS (18 May 1901 ŌĆō 11 May 1988) was a Scottish marine biologist who specialised in carcinology and was an expert in crabs and sea spiders. She worked at the Natu ...

. The reason for this debate is that krill share some morphological features of decapods and others of mysids.

Molecular studies have not unambiguously grouped them, possibly due to the paucity of key rare species such as ''Bentheuphausia amblyops'' in krill and ''Amphionides reynaudii'' in Eucarida. One study supports the monophyly of Eucarida (with basal Mysida), another groups Euphausiacea with Mysida (the Schizopoda), while yet another groups Euphausiacea with Hoplocarida

Hoplocarida is a subclass of crustaceans. The only extant members are the mantis shrimp (Stomatopoda), but two other orders existed in the Palaeozoic

The Paleozoic ( , , ; or Palaeozoic) Era is the first of three geological eras of the Phane ...

.

Timeline

No extant fossil can be unequivocally assigned to Euphausiacea. Some extincteumalacostraca

Eumalacostraca is a subclass of crustaceans, containing almost all living malacostracans, or about 40,000 described species. The remaining subclasses are the Phyllocarida and possibly the Hoplocarida. Eumalacostracans have 19 segments (5 cephalic ...

n taxa

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; : taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular name and ...

have been thought to be euphausiaceans such as '' Anthracophausia'', ''Crangopsis

''Crangopsis'' is an extinct genus of crustacean

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea ( ...

''ŌĆönow assigned to the Aeschronectida

Aeschronectida is an extinct order of mantis shrimp-like crustaceans which lived in the Mississippian subperiod in what is now Montana. They exclusively lived in the Carboniferous, or the age of amphibians. They have been found mostly in the U.S ...

(Hoplocarida)ŌĆöand ''Palaeomysis''. All dating of speciation

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which populations evolve to become distinct species. The biologist Orator F. Cook coined the term in 1906 for cladogenesis, the splitting of lineages, as opposed to anagenesis, phyletic evolution within ...

events were estimated by molecular clock

The molecular clock is a figurative term for a technique that uses the mutation rate of biomolecules to deduce the time in prehistory when two or more life forms diverged. The biomolecular data used for such calculations are usually nucleot ...

methods, which placed the last common ancestor of the krill family Euphausiidae (order Euphausiacea minus ''Bentheuphausia amblyops'') to have lived in the Lower Cretaceous

Lower may refer to:

* ''Lower'' (album), 2025 album by Benjamin Booker

* Lower (surname)

* Lower Township, New Jersey

*Lower Receiver (firearms)

* Lower Wick Gloucestershire, England

See also

* Nizhny

{{Disambiguation ...

about .

Distribution

Krill occur worldwide in all oceans, although many individual species haveendemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

or neritic

The neritic zone (or sublittoral zone) is the relatively shallow part of the ocean above the drop-off of the continental shelf, approximately in depth.

From the point of view of marine biology it forms a relatively stable and well-illuminated ...

(''i.e.,'' coastal) distributions. '' Bentheuphausia amblyops'', a bathypelagic

The bathypelagic zone or bathyal zone (from Greek ╬▓╬▒╬ĖŽŹŽé (bath├Įs), deep) is the part of the open ocean that extends from a depth of below the ocean surface. It lies between the mesopelagic above and the abyssopelagic below. The bathypela ...

species, has a cosmopolitan distribution

In biogeography, a cosmopolitan distribution is the range of a taxon that extends across most or all of the surface of the Earth, in appropriate habitats; most cosmopolitan species are known to be highly adaptable to a range of climatic and en ...

within its deep-sea habitat.

Species of the genus ''Thysanoessa

Thysanoessa is a genus of the krill that play critical roles in the marine food web. They're abundant in Arctic and Antarctic areas, feeding on zooplankton and detritus to obtain energy. Thysanoessa are responsible for the transportation of carbo ...

'' occur in both Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for se ...

and Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is bounded by the cont ...

oceans. The Pacific is home to ''Euphausia pacifica

''Euphausia pacifica'', the North Pacific krill, is a euphausid that lives in the northern Pacific Ocean.

In Japan, ''E. pacifica'' is called ''isada krill'' or ' (ŃāäŃāÄŃāŖŃéĘŃé¬ŃéŁŃéóŃā¤). It is found from Suruga Bay northwards, including all ...

''. Northern krill occur across the Atlantic from the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

northward.

Species with neritic distributions include the four species of the genus ''Nyctiphanes

''Nyctiphanes'' is a genus of krill, comprising four species with an anti-tropical distribution. Based on molecular phylogenetic analyses of the cytochrome oxidase gene and 16S ribosomal DNA, ''Nyctiphanes'' is believed to have evolved during ...

''.D'Amato, M.E. ''et al.'': "", in ''Marine Biology vol. 155, no. 2'', pp. 243ŌĆō247, August 2008. They are highly abundant along the upwelling

Upwelling is an physical oceanography, oceanographic phenomenon that involves wind-driven motion of dense, cooler, and usually nutrient-rich water from deep water towards the ocean surface. It replaces the warmer and usually nutrient-depleted sur ...

regions of the California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares MexicoŌĆōUnited States border, an ...

, Humboldt Humboldt may refer to:

People

* Alexander von Humboldt, German natural scientist, brother of Wilhelm von Humboldt

* Wilhelm von Humboldt, German linguist, philosopher, and diplomat, brother of Alexander von Humboldt

Fictional characters

* Hu ...

, Benguela

Benguela (; Umbundu: Luombaka) is a city in western Angola, capital of Benguela Province. Benguela is one of Angola's most populous cities with a population of 555,124 in the city and 561,775 in the municipality, at the 2014 census.

History

Por ...

, and Canarias current systems. Another species having only neritic distribution is ''E. crystallorophias'', which is endemic to the Antarctic coastline.

Species with endemic distributions include ''Nyctiphanes capensis

''Nyctiphanes'' is a genus of krill, comprising four species with an anti-tropical distribution. Based on molecular phylogenetic analyses of the cytochrome oxidase gene and 16S ribosomal DNA, ''Nyctiphanes'' is believed to have evolved during t ...

'', which occurs only in the Benguela current, '' E. mucronata'' in the Humboldt current, and the six ''Euphausia'' species native to the Southern Ocean.

In the Antarctic, seven species are known, one in genus ''Thysanoessa'' ('' T. macrura'') and six in ''Euphausia''. The Antarctic krill

Antarctic krill (''Euphausia superba'') is a species of krill found in the Antarctica, Antarctic waters of the Southern Ocean. It is a small, swimming crustacean that lives in large schools, called swarms, sometimes reaching densities of 10,000Ō ...

(''Euphausia superba'') commonly lives at depths reaching , whereas ice krill ('' Euphausia crystallorophias'') reach depth of , though they commonly inhabit depths of at most . Krill perform Diel Vertical Migrations (DVM) in large swarms, and acoustic data has shown these migrations to go up to 400 metres in depth. Both are found at latitude

In geography, latitude is a geographic coordinate system, geographic coordinate that specifies the north-south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from ŌłÆ90┬░ at t ...

s south of 55┬░ S, with ''E. crystallorophias'' dominating south of 74┬░ S and in regions of pack ice

Pack or packs may refer to:

Music

* Packs (band), a Canadian indie rock band

* ''Packs'' (album), by Your Old Droog

* ''Packs'', a Berner album

Places

* Pack, Styria, defunct Austrian municipality

* Pack, Missouri, United States (US)

* ...

. Other species known in the Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the world ocean, generally taken to be south of 60th parallel south, 60┬░ S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is the seco ...

are '' E. frigida'', '' E. longirostris'', '' E. triacantha'' and '' E. vallentini''.

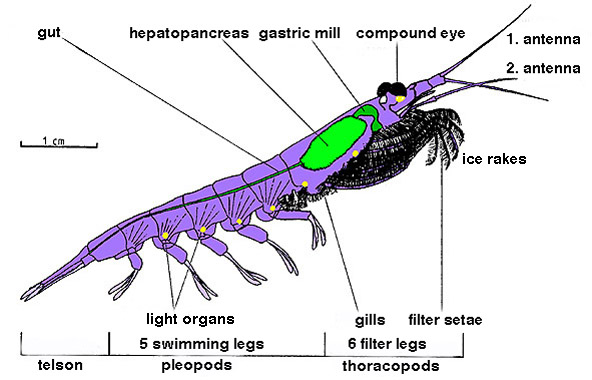

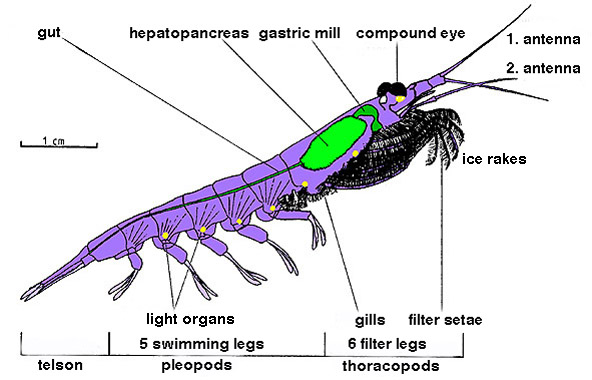

Anatomy and morphology

Krill are

Krill are crustaceans

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of Arthropod, arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquat ...

and, like all crustaceans, they have a chitin

Chitin (carbon, C8hydrogen, H13oxygen, O5nitrogen, N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of N-Acetylglucosamine, ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cell ...

ous exoskeleton

An exoskeleton () . is a skeleton that is on the exterior of an animal in the form of hardened integument, which both supports the body's shape and protects the internal organs, in contrast to an internal endoskeleton (e.g. human skeleton, that ...

. They have anatomy similar to a standard decapod

The Decapoda or decapods, from Ancient Greek ╬┤╬Ą╬║╬¼Žé (''dek├Īs''), meaning "ten", and ŽĆ╬┐ŽŹŽé (''po├║s''), meaning "foot", is a large order of crustaceans within the class Malacostraca, and includes crabs, lobsters, crayfish, shrimp, and p ...

with their bodies made up of three parts: the cephalothorax is composed of the head

A head is the part of an organism which usually includes the ears, brain, forehead, cheeks, chin, eyes, nose, and mouth, each of which aid in various sensory functions such as sight, hearing, smell, and taste. Some very simple ani ...

and the thorax

The thorax (: thoraces or thoraxes) or chest is a part of the anatomy of mammals and other tetrapod animals located between the neck and the abdomen.

In insects, crustaceans, and the extinct trilobites, the thorax is one of the three main di ...

, which are fused, and the abdomen

The abdomen (colloquially called the gut, belly, tummy, midriff, tucky, or stomach) is the front part of the torso between the thorax (chest) and pelvis in humans and in other vertebrates. The area occupied by the abdomen is called the abdominal ...

, which bears the ten swimming appendages, and the tail fan. This outer shell of krill is transparent in most species.

Krill feature intricate compound eye

A compound eye is a Eye, visual organ found in arthropods such as insects and crustaceans. It may consist of thousands of ommatidium, ommatidia, which are tiny independent photoreception units that consist of a cornea, lens (anatomy), lens, and p ...

s. Some species adapt to different lighting conditions through the use of screening pigment

A pigment is a powder used to add or alter color or change visual appearance. Pigments are completely or nearly solubility, insoluble and reactivity (chemistry), chemically unreactive in water or another medium; in contrast, dyes are colored sub ...

s.

They have two antennae and several pairs of thoracic legs called pereiopod

The anatomy of a decapod consists of 20 body segments grouped into two main body parts: the cephalothorax and the pleon (abdomen). Each segment ŌĆō often called a somite ŌĆō may possess one pair of appendages, although in various groups these m ...

s or thoracopod

The arthropod leg is a form of jointed appendage of arthropods, usually used for walking. Many of the terms used for arthropod leg segments (called podomeres) are of Latin origin, and may be confused with terms for bones: ''coxa'' (meaning hip (a ...

s, so named because they are attached to the thorax. Their number varies among genera and species. These thoracic legs include feeding legs and grooming legs.

Krill are probably the sister clade of decapods because all species have five pairs of swimming legs called "swimmerets" in common with the latter, very similar to those of a lobster

Lobsters are Malacostraca, malacostracans Decapoda, decapod crustaceans of the family (biology), family Nephropidae or its Synonym (taxonomy), synonym Homaridae. They have long bodies with muscular tails and live in crevices or burrows on th ...

or freshwater crayfish

Crayfish are freshwater crustaceans belonging to the infraorder Astacidea, which also contains lobsters. Taxonomically, they are members of the Superfamily (taxonomy), superfamilies Astacoidea and Parastacoidea. They breathe through feather- ...

.

In spite of having ten swimmerets, otherwise known as pleopods

The anatomy of a decapod consists of 20 body segments grouped into two main body parts: the cephalothorax and the pleon (abdomen). Each segment ŌĆō often called a somite ŌĆō may possess one pair of appendages, although in various groups these ma ...

, krill cannot be considered decapods. They lack any true ground-based legs due to all their pereiopods having been converted into grooming and auxiliary feeding legs. In Decapoda

The Decapoda or decapods, from Ancient Greek ╬┤╬Ą╬║╬¼Žé (''dek├Īs''), meaning "ten", and ŽĆ╬┐ŽŹŽé (''po├║s''), meaning "foot", is a large order of crustaceans within the class Malacostraca, and includes crabs, lobsters, crayfish, shrimp, a ...

, there are ten functioning pereiopods, giving them their name; whereas here there are no remaining locomotive pereiopods. Nor are there consistently ten pereiopods at all.

Most krill are about long as adults. A few species grow to sizes on the order of . The largest krill species, ''Thysanopoda cornuta'', lives deep in the open ocean. Krill can be easily distinguished from other crustaceans such as true shrimp

A shrimp (: shrimp (American English, US) or shrimps (British English, UK)) is a crustacean with an elongated body and a primarily Aquatic locomotion, swimming mode of locomotion ŌĆō typically Decapods belonging to the Caridea or Dendrobranchi ...

by their externally visible gill

A gill () is a respiration organ, respiratory organ that many aquatic ecosystem, aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow r ...

s.

Except for '' Bentheuphausia amblyops'', krill are bioluminescent

Bioluminescence is the emission of light during a chemiluminescence reaction by living organisms. Bioluminescence occurs in multifarious organisms ranging from marine vertebrates and invertebrates, as well as in some fungi, microorganisms inc ...

animals having organs called photophore

A photophore is a specialized anatomical structure found in a variety of organisms that emits light through the process of boluminescence. This light may be produced endogenously by the organism itself (symbiotic) or generated through a mut ...

s that can emit light. The light is generated by an enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

-catalysed chemiluminescence

Chemiluminescence (also chemoluminescence) is the emission of light (luminescence) as the result of a chemical reaction, i.e. a chemical reaction results in a flash or glow of light. A standard example of chemiluminescence in the laboratory se ...

reaction, wherein a luciferin

Luciferin () is a generic term for the light-emitting chemical compound, compound found in organisms that generate bioluminescence. Luciferins typically undergo an enzyme-catalyzed reaction with Oxygen, molecular oxygen. The resulting transforma ...

(a kind of pigment) is activated by a luciferase

Luciferase is a generic term for the class of oxidative enzymes that produce bioluminescence, and is usually distinguished from a photoprotein. The name was first used by Raphaël Dubois who invented the words ''luciferin'' and ''luciferase'' ...

enzyme. Studies indicate that the luciferin of many krill species is a fluorescent

Fluorescence is one of two kinds of photoluminescence, the emission of light by a substance that has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation. When exposed to ultraviolet radiation, many substances will glow (fluoresce) with color ...

tetrapyrrole

Tetrapyrroles are a class of chemical compounds that contain four pyrrole or pyrrole-like rings. The pyrrole/pyrrole derivatives are linked by ( or units), in either a linear or a cyclic fashion. Pyrroles are a five-atom ring with four carbon ...

similar but not identical to dinoflagellate

The Dinoflagellates (), also called Dinophytes, are a monophyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes constituting the phylum Dinoflagellata and are usually considered protists. Dinoflagellates are mostly marine plankton, but they are also commo ...

luciferin and that the krill probably do not produce this substance themselves but acquire it as part of their diet, which contains dinoflagellates. Krill photophores are complex organs with lenses and focusing abilities, and can be rotated by muscles. The precise function of these organs is as yet unknown; possibilities include mating, social interaction or orientation and as a form of counter-illumination camouflage to compensate their shadow against overhead ambient light.

Ecology

Feeding

Many krill arefilter feeders

Filter feeders are aquatic animals that acquire nutrients by feeding on organic matters, food particles or smaller organisms (bacteria, microalgae and zooplanktons) suspended in water, typically by having the water pass over or through a spec ...

: their frontmost appendage

An appendage (or outgrowth) is an external body part or natural prolongation that protrudes from an organism's body such as an arm or a leg. Protrusions from single-celled bacteria and archaea are known as cell-surface appendages or surface app ...

s, the thoracopods, form very fine combs with which they can filter out their food from the water. These filters can be very fine in species (such as ''Euphausia'' spp.) that feed primarily on phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater Aquatic ecosystem, ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek language, Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), mea ...

, in particular on diatom

A diatom (Neo-Latin ''diatoma'') is any member of a large group comprising several Genus, genera of algae, specifically microalgae, found in the oceans, waterways and soils of the world. Living diatoms make up a significant portion of Earth's B ...

s, which are unicellular algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthesis, photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular ...

. Krill are mostly omnivorous

An omnivore () is an animal that regularly consumes significant quantities of both plant and animal matter. Obtaining energy and nutrients from plant and animal matter, omnivores digest carbohydrates, protein, fat, and fiber, and metabolize ...

, although a few species are carnivorous

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose nutrition and energy requirements are met by consumption of animal tissues (mainly mu ...

, preying on small zooplankton and fish larvae

A larva (; : larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into their next life stage. Animals with indirect developmental biology, development such as insects, some arachnids, amphibians, or cnidarians typical ...

.

Krill are an important element of the aquatic food chain

A food chain is a linear network of links in a food web, often starting with an autotroph (such as grass or algae), also called a producer, and typically ending at an apex predator (such as grizzly bears or killer whales), detritivore (such as ...

. Krill convert the primary production

In ecology, primary production is the synthesis of organic compounds from atmospheric or aqueous carbon dioxide. It principally occurs through the process of photosynthesis, which uses light as its source of energy, but it also occurs through ...

of their prey into a form suitable for consumption by larger animals that cannot feed directly on the minuscule algae. Northern krill and some other species have a relatively small filtering basket and actively hunt copepod

Copepods (; meaning 'oar-feet') are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat (ecology), habitat. Some species are planktonic (living in the water column), some are benthos, benthic (living on the sedimen ...

s and larger zooplankton.

Predation

Many animals feed on krill, ranging from smaller animals like fish or penguins to larger ones likeseals

Seals may refer to:

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, or "true seal"

** Fur seal

* Seal (emblem), a device to impress an emblem, used as a means of a ...

and baleen whale

Baleen whales (), also known as whalebone whales, are marine mammals of the order (biology), parvorder Mysticeti in the infraorder Cetacea (whales, dolphins and porpoises), which use baleen plates (or "whalebone") in their mouths to sieve plankt ...

s.

Disturbances of an ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) is a system formed by Organism, organisms in interaction with their Biophysical environment, environment. The Biotic material, biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and en ...

resulting in a decline in the krill population can have far-reaching effects. During a coccolithophore

Coccolithophores, or coccolithophorids, are single-celled organisms which are part of the phytoplankton, the autotrophic (self-feeding) component of the plankton community. They form a group of about 200 species, and belong either to the kingdom ...

bloom in the Bering Sea

The Bering Sea ( , ; rus, ąæąĄ╠üčĆąĖąĮą│ąŠą▓ąŠ ą╝ąŠ╠üčĆąĄ, r=B├®ringovo m├│re, p=╦łb╩▓er╩▓╔¬n╔Ī╔Öv╔Ö ╦łmor╩▓e) is a marginal sea of the Northern Pacific Ocean. It forms, along with the Bering Strait, the divide between the two largest landmasse ...

in 1998, for instance, the diatom concentration dropped in the affected area. Krill cannot feed on the smaller coccolithophores, and consequently the krill population (mainly ''E. pacifica'') in that region declined sharply. This in turn affected other species: the shearwater

Shearwaters are medium-sized long-winged seabirds in the petrel family Procellariidae. They have a global marine distribution, but are most common in temperate and cold waters, and are pelagic outside the breeding season.

Description

These tube ...

population dropped. The incident was thought to have been one reason salmon

Salmon (; : salmon) are any of several list of commercially important fish species, commercially important species of euryhaline ray-finned fish from the genera ''Salmo'' and ''Oncorhynchus'' of the family (biology), family Salmonidae, native ...

did not spawn that season.

Several single-celled endoparasitoid

In evolutionary ecology, a parasitoid is an organism that lives in close association with its host (biology), host at the host's expense, eventually resulting in the death of the host. Parasitoidism is one of six major evolutionarily stable str ...

ic ciliate

The ciliates are a group of alveolates characterized by the presence of hair-like organelles called cilia, which are identical in structure to flagellum, eukaryotic flagella, but are in general shorter and present in much larger numbers, with a ...

s of the genus '' Collinia'' can infect species of krill and devastate affected populations. Such diseases were reported for ''Thysanoessa

Thysanoessa is a genus of the krill that play critical roles in the marine food web. They're abundant in Arctic and Antarctic areas, feeding on zooplankton and detritus to obtain energy. Thysanoessa are responsible for the transportation of carbo ...

inermis'' in the Bering Sea and also for ''E. pacifica'', ''Thysanoessa spinifera'', and ''T. gregaria'' off the North American Pacific coast. Some ectoparasite

Parasitism is a Symbiosis, close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives (at least some of the time) on or inside another organism, the Host (biology), host, causing it some harm, and is Adaptation, adapted str ...

s of the family Dajidae (epicaridean isopod

Isopoda is an Order (biology), order of crustaceans. Members of this group are called isopods and include both Aquatic animal, aquatic species and Terrestrial animal, terrestrial species such as woodlice. All have rigid, segmented exoskeletons ...

s) afflict krill (and also shrimp and mysid

Mysida is an order of small, shrimp-like crustaceans in the malacostracan superorder Peracarida. Their common name opossum shrimps stems from the presence of a brood pouch or "marsupium" in females. The fact that the larvae are reared in thi ...

s); one such parasite is '' Oculophryxus bicaulis'', which was found on the krill ''Stylocheiron affine'' and ''S. longicorne''. It attaches itself to the animal's eyestalk and sucks blood from its head; it apparently inhibits the host's reproduction, as none of the afflicted animals reached maturity.

Climate change

Present-day climate change includes both global warmingŌĆöthe ongoing increase in Global surface temperature, global average temperatureŌĆöand its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate variability and change, Climate change in ...

poses another threat to krill populations.

Plastics

Preliminary research indicates krill can digestmicroplastic

Microplastics are "synthetic solid particles or polymeric matrices, with regular or irregular shape and with size ranging from 1 ╬╝m to 5 mm, of either primary or secondary manufacturing origin, which are insoluble in water." Microplastics ar ...

s under in diameter, breaking them down and excreting them back into the environment in smaller form.

Life history and behavior

The life cycle of krill is relatively well understood, despite minor variations in detail from species to species. After krill hatch, they experience several larval stagesŌĆö''nauplius (larva), nauplius'', ''pseudometanauplius'', ''metanauplius'', ''calyptopsis'', and ''furcilia'', each of which divides into sub-stages. The pseudometanauplius stage is exclusive to species that lay their eggs within an ovigerous sac: so-called "sac-spawners". The larvae grow and ecdysis, moult repeatedly as they develop, replacing their rigid exoskeleton when it becomes too small. Smaller animals moult more frequently than larger ones. Yolk reserves within their body nourish the larvae through metanauplius stage.

By the calyptopsis stages cellular differentiation, differentiation has progressed far enough for them to develop a mouth and a digestive tract, and they begin to eat phytoplankton. By that time their yolk reserves are exhausted and the larvae must have reached the photic zone, the upper layers of the ocean where algae flourish. During the furcilia stages, segments with pairs of swimmerets are added, beginning at the frontmost segments. Each new pair becomes functional only at the next moult. The number of segments added during any one of the furcilia stages may vary even within one species depending on environmental conditions. After the final furcilia stage, an immature juvenile emerges in a shape similar to an adult, and subsequently develops gonads and matures sexually.

The life cycle of krill is relatively well understood, despite minor variations in detail from species to species. After krill hatch, they experience several larval stagesŌĆö''nauplius (larva), nauplius'', ''pseudometanauplius'', ''metanauplius'', ''calyptopsis'', and ''furcilia'', each of which divides into sub-stages. The pseudometanauplius stage is exclusive to species that lay their eggs within an ovigerous sac: so-called "sac-spawners". The larvae grow and ecdysis, moult repeatedly as they develop, replacing their rigid exoskeleton when it becomes too small. Smaller animals moult more frequently than larger ones. Yolk reserves within their body nourish the larvae through metanauplius stage.

By the calyptopsis stages cellular differentiation, differentiation has progressed far enough for them to develop a mouth and a digestive tract, and they begin to eat phytoplankton. By that time their yolk reserves are exhausted and the larvae must have reached the photic zone, the upper layers of the ocean where algae flourish. During the furcilia stages, segments with pairs of swimmerets are added, beginning at the frontmost segments. Each new pair becomes functional only at the next moult. The number of segments added during any one of the furcilia stages may vary even within one species depending on environmental conditions. After the final furcilia stage, an immature juvenile emerges in a shape similar to an adult, and subsequently develops gonads and matures sexually.

Reproduction

During the mating season, which varies by species and climate, the male deposits a spermatophore, sperm sack at the female's genital opening (named ''thelycum''). The females can carry several thousand eggs in their ovary, which may then account for as much as one third of the animal's body mass. Krill can have multiple broods in one season, with interbrood intervals lasting on the order of days.

Krill employ two types of spawning mechanism. The 57 species of the genera ''Bentheuphausia'', ''Euphausia'', ''Meganyctiphanes'', ''Thysanoessa'', and ''Thysanopoda'' are "broadcast spawners": the female releases the fertilised eggs into the water, where they usually sink, disperse, and are on their own. These species generally hatch in the nauplius 1 stage, but have recently been discovered to hatch sometimes as metanauplius or even as calyptopis stages. The remaining 29 species of the other genera are "sac spawners", where the female carries the eggs with her, attached to the rearmost pairs of thoracopods until they hatch as metanauplii, although some species like ''Nematoscelis difficilis'' may hatch as nauplius or pseudometanauplius.

During the mating season, which varies by species and climate, the male deposits a spermatophore, sperm sack at the female's genital opening (named ''thelycum''). The females can carry several thousand eggs in their ovary, which may then account for as much as one third of the animal's body mass. Krill can have multiple broods in one season, with interbrood intervals lasting on the order of days.

Krill employ two types of spawning mechanism. The 57 species of the genera ''Bentheuphausia'', ''Euphausia'', ''Meganyctiphanes'', ''Thysanoessa'', and ''Thysanopoda'' are "broadcast spawners": the female releases the fertilised eggs into the water, where they usually sink, disperse, and are on their own. These species generally hatch in the nauplius 1 stage, but have recently been discovered to hatch sometimes as metanauplius or even as calyptopis stages. The remaining 29 species of the other genera are "sac spawners", where the female carries the eggs with her, attached to the rearmost pairs of thoracopods until they hatch as metanauplii, although some species like ''Nematoscelis difficilis'' may hatch as nauplius or pseudometanauplius.

Moulting

Moulting occurs whenever a specimen outgrows its rigid exoskeleton. Young animals, growing faster, moult more often than older and larger ones. The frequency of moulting varies widely by species and is, even within one species, subject to many external factors such as latitude, water temperature, and food availability. The subtropical species ''Nyctiphanes simplex'', for instance, has an overall inter-moult period of two to seven days: larvae moult on the average every four days, while juveniles and adults do so, on average, every six days. For ''E. superba'' in the Antarctic sea, inter-moult periods ranging between 9 and 28 days depending on the temperature between have been observed, and for ''Meganyctiphanes norvegica'' in the North Sea the inter-moult periods range also from 9 and 28 days but at temperatures between . ''E. superba'' is able to reduce its body size when there is not enough food available, moulting also when its exoskeleton becomes too large. Similar shrinkage has also been observed for ''E. pacifica'', a species occurring in the Pacific Ocean from polar to temperate zones, as an adaptation to abnormally high water temperatures. Shrinkage has been postulated for other temperate-zone species of krill as well.Lifespan

Some high-latitude species of krill can live for more than six years (e.g., ''Euphausia superba''); others, such as the mid-latitude species ''Euphausia pacifica'', live for only two years. Subtropical or tropical species' longevity is still shorter, e.g., ''Nyctiphanes simplex'', which usually lives for only six to eight months.Swarming

Most krill are swarming animals; the sizes and densities of such swarms vary by species and region. For ''Euphausia superba'', swarms reach 10,000 to 60,000 individuals per cubic metre. Swarming is a defensive mechanism, confusing smaller predators that would like to pick out individuals. In 2012, Gandomi and Alavi presented what appears to be a Swarm intelligence#Krill herd algorithm, successful stochastic algorithm for modelling the behaviour of krill swarms. The algorithm is based on three main factors: " (i) movement induced by the presence of other individuals (ii) foraging activity, and (iii) random diffusion."

Most krill are swarming animals; the sizes and densities of such swarms vary by species and region. For ''Euphausia superba'', swarms reach 10,000 to 60,000 individuals per cubic metre. Swarming is a defensive mechanism, confusing smaller predators that would like to pick out individuals. In 2012, Gandomi and Alavi presented what appears to be a Swarm intelligence#Krill herd algorithm, successful stochastic algorithm for modelling the behaviour of krill swarms. The algorithm is based on three main factors: " (i) movement induced by the presence of other individuals (ii) foraging activity, and (iii) random diffusion."

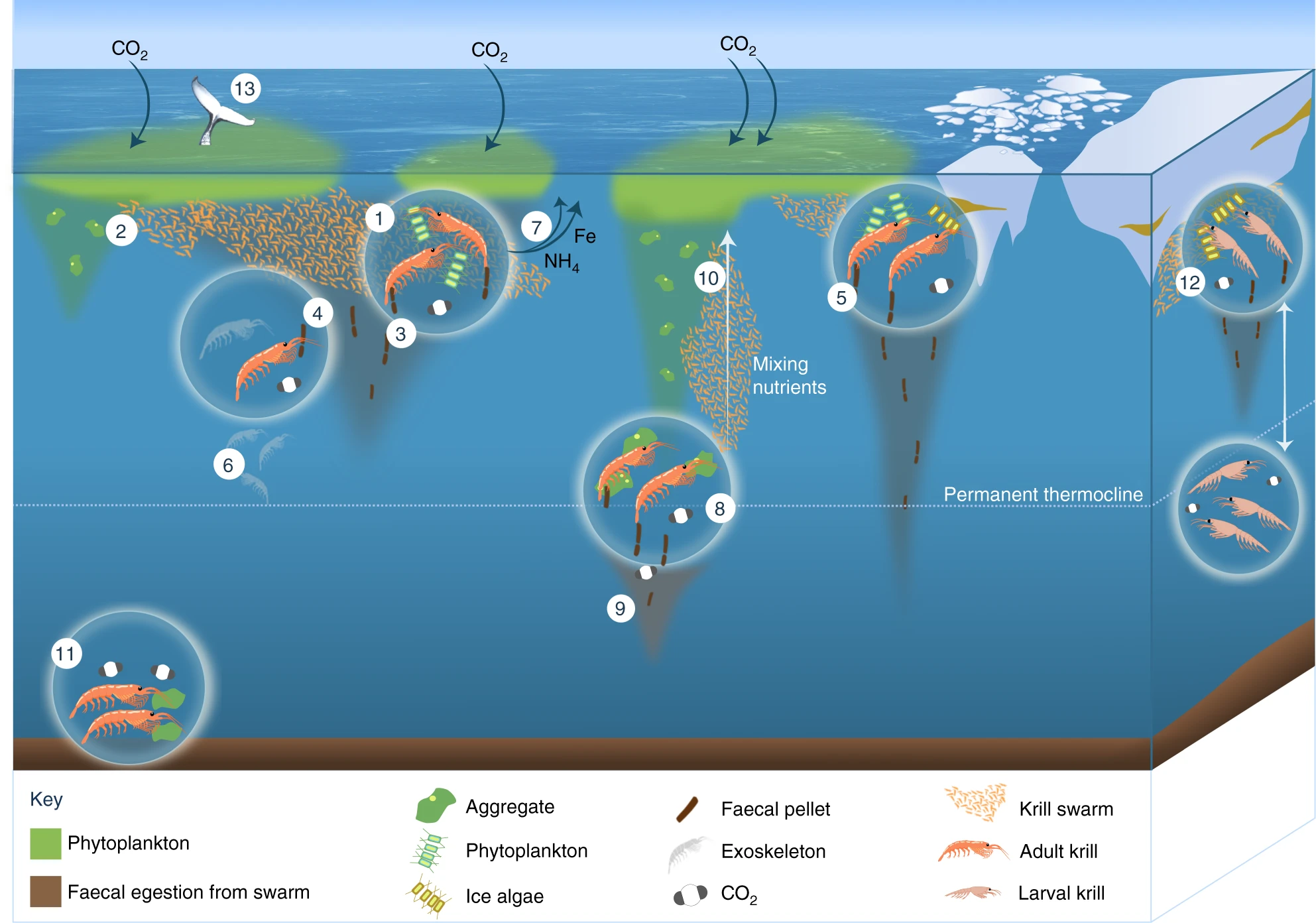

Vertical migration

Krill typically follow a diurnality, diurnal Diel vertical migration, vertical migration. It has been assumed that they spend the day at greater depths and rise during the night toward the surface. The deeper they go, the more they reduce their activity, apparently to reduce encounters with predators and to conserve energy. Swimming activity in krill varies with stomach fullness. Sated animals that had been feeding at the surface swim less actively and therefore sink below the mixed layer. As they sink they produce feces which employs a role in the Antarctic carbon cycle. Krill with empty stomachs swim more actively and thus head towards the surface.

Vertical migration may be a 2ŌĆō3 times daily occurrence. Some species (e.g., ''Euphausia superba'', ''E. pacifica'', ''E. hanseni'', ''Pseudeuphausia latifrons'', and ''Thysanoessa spinifera'') form surface swarms during the day for feeding and reproductive purposes even though such behaviour is dangerous because it makes them extremely vulnerable to predators.

Experimental studies using ''Artemia salina'' as a model suggest that the vertical migrations of krill several hundreds of metres, in groups tens of metres deep, could collectively create enough downward jets of water to have a significant effect on ocean mixing.

Dense swarms can elicit a feeding frenzy among fish, birds and mammal predators, especially near the surface. When disturbed, a swarm scatters, and some individuals have even been observed to moult instantly, leaving the exuvia behind as a decoy.

Krill normally swim at a pace of 5ŌĆō10 cm/s (2ŌĆō3 body lengths per second), using their swimmerets for propulsion. Their larger migrations are subject to ocean currents. When in danger, they show an escape reaction called Caridoid escape reaction, lobsteringŌĆöflicking their Caudal (anatomical term), caudal structures, the telson and the uropods, they move backwards through the water relatively quickly, achieving speeds in the range of 10 to 27 body lengths per second, which for large krill such as ''E. superba'' means around . Their swimming performance has led many researchers to classify adult krill as nekton, micro-nektonic life-forms, i.e., small animals capable of individual motion against (weak) currents. Larval forms of krill are generally considered zooplankton.

Krill typically follow a diurnality, diurnal Diel vertical migration, vertical migration. It has been assumed that they spend the day at greater depths and rise during the night toward the surface. The deeper they go, the more they reduce their activity, apparently to reduce encounters with predators and to conserve energy. Swimming activity in krill varies with stomach fullness. Sated animals that had been feeding at the surface swim less actively and therefore sink below the mixed layer. As they sink they produce feces which employs a role in the Antarctic carbon cycle. Krill with empty stomachs swim more actively and thus head towards the surface.

Vertical migration may be a 2ŌĆō3 times daily occurrence. Some species (e.g., ''Euphausia superba'', ''E. pacifica'', ''E. hanseni'', ''Pseudeuphausia latifrons'', and ''Thysanoessa spinifera'') form surface swarms during the day for feeding and reproductive purposes even though such behaviour is dangerous because it makes them extremely vulnerable to predators.

Experimental studies using ''Artemia salina'' as a model suggest that the vertical migrations of krill several hundreds of metres, in groups tens of metres deep, could collectively create enough downward jets of water to have a significant effect on ocean mixing.

Dense swarms can elicit a feeding frenzy among fish, birds and mammal predators, especially near the surface. When disturbed, a swarm scatters, and some individuals have even been observed to moult instantly, leaving the exuvia behind as a decoy.

Krill normally swim at a pace of 5ŌĆō10 cm/s (2ŌĆō3 body lengths per second), using their swimmerets for propulsion. Their larger migrations are subject to ocean currents. When in danger, they show an escape reaction called Caridoid escape reaction, lobsteringŌĆöflicking their Caudal (anatomical term), caudal structures, the telson and the uropods, they move backwards through the water relatively quickly, achieving speeds in the range of 10 to 27 body lengths per second, which for large krill such as ''E. superba'' means around . Their swimming performance has led many researchers to classify adult krill as nekton, micro-nektonic life-forms, i.e., small animals capable of individual motion against (weak) currents. Larval forms of krill are generally considered zooplankton.

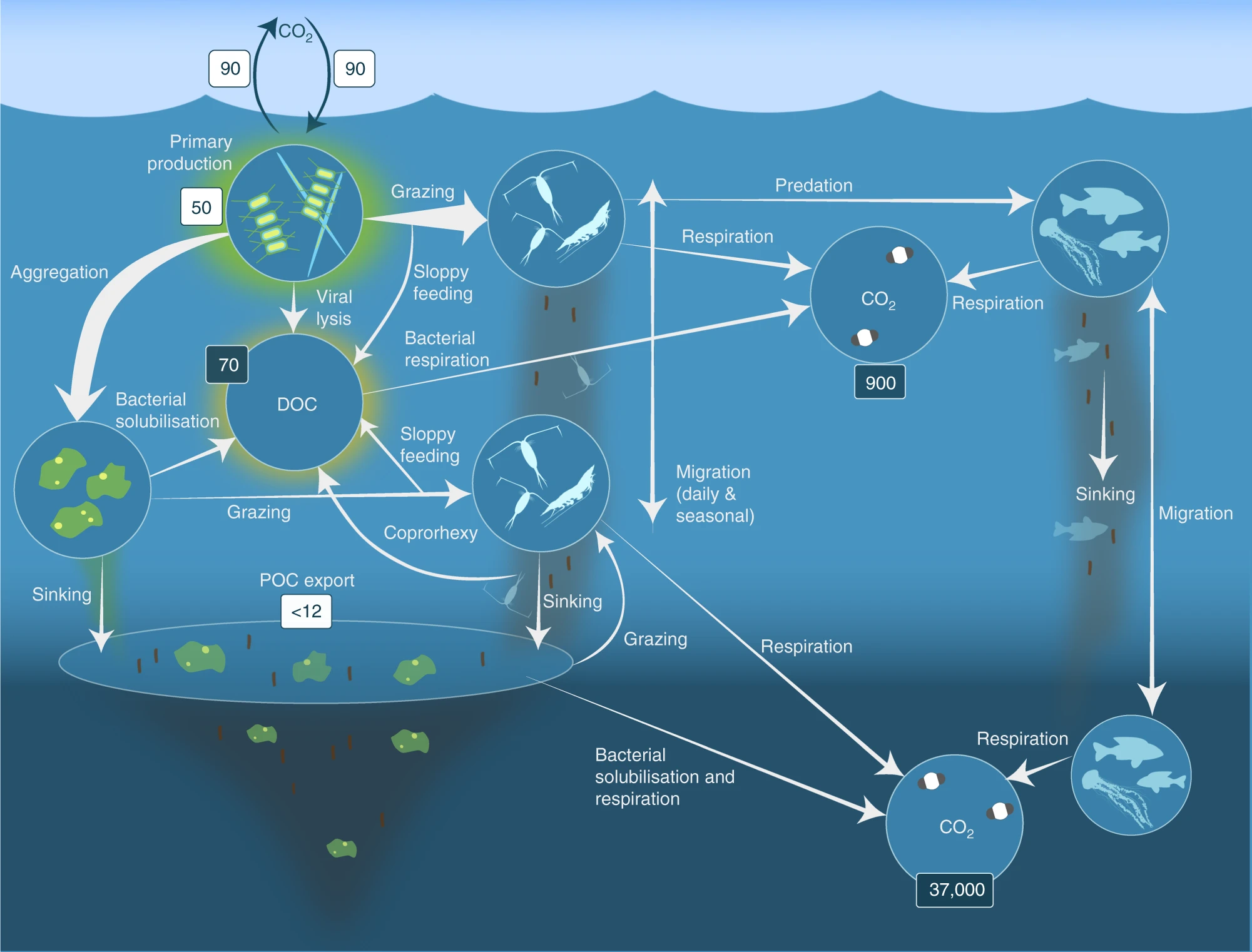

Biogeochemical cycles

The Antarctic krill is an important species in the context of Marine biogeochemical cycles, biogeochemical cycling and in the Antarctic food web. It plays a prominent role in the Southern Ocean because of its ability to Nutrient cycle, cycle nutrients and to feed penguins and Baleen whale, baleen and

The Antarctic krill is an important species in the context of Marine biogeochemical cycles, biogeochemical cycling and in the Antarctic food web. It plays a prominent role in the Southern Ocean because of its ability to Nutrient cycle, cycle nutrients and to feed penguins and Baleen whale, baleen and blue whale

The blue whale (''Balaenoptera musculus'') is a marine mammal and a baleen whale. Reaching a maximum confirmed length of and weighing up to , it is the largest animal known ever to have existed. The blue whale's long and slender body can ...

s.

Human uses

Harvesting history

Krill have been harvested as a food source for humans and domesticated animals since at least the 19th century, and possibly earlier in Japan, where it was known as ''okiami''. Large-scale fishing developed in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and now occurs only in Antarctic waters and in the seas around Japan. Historically, the largest krill fishery nations were Japan and the Soviet Union, or, after the latter's dissolution, Russia and Ukraine. The harvest peaked, which in 1983 was about 528,000 tonnes in the Southern Ocean alone (of which the Soviet Union took in 93%), is now managed as a precaution against overfishing. In 1993, two events caused a decline in krill fishing: Russia exited the industry; and the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) defined maximum catch quotas for a sustainable fisheries, sustainable exploitation of Antarctic krill. After an October 2011 review, the Commission decided not to change the quota. The annual Antarctic catch stabilised at around 100,000 tonnes, which is roughly one fiftieth of the CCAMLR catch quota. The main limiting factor was probably high costs along with political and legal issues. The Japanese fishery saturated at some 70,000 tonnes. Although krill are found worldwide, fishing in Southern Oceans are preferred because the krill are more "catchable" and abundant in these regions. Particularly in Antarctic seas which are considered as wikt:pristine, pristine, they are considered a "clean product". In 2018 it was announced that almost every krill fishing company operating in Antarctica will abandon operations in huge areas around the Antarctic Peninsula from 2020, including "buffer zones" around breeding colonies of penguins.Human consumption

Although the total Biomass (ecology), biomass of Antarctic krill may be as abundant as 400 million tonnes, the human impact on this keystone species is growing, with a 39% increase in total fishing yield to 294,000 tonnes over 2010ŌĆō2014. Major countries involved in krill harvesting are Norway (56% of total catch in 2014), the Republic of Korea (19%), and China (18%). Krill is a rich source of protein and omega-3 fatty acids which are under development in the early 21st century as human food, dietary supplements as oil capsules, livestock food, and pet food. Krill tastes salty with a somewhat stronger fish flavor than shrimp. For mass consumption and commercially prepared products, they must be peeled to remove the inedibleexoskeleton

An exoskeleton () . is a skeleton that is on the exterior of an animal in the form of hardened integument, which both supports the body's shape and protects the internal organs, in contrast to an internal endoskeleton (e.g. human skeleton, that ...

.

In 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration published a letter of no objection for a manufactured krill oil product to be generally recognized as safe (GRAS) for human consumption.

Krill (and other planktonic shrimp

A shrimp (: shrimp (American English, US) or shrimps (British English, UK)) is a crustacean with an elongated body and a primarily Aquatic locomotion, swimming mode of locomotion ŌĆō typically Decapods belonging to the Caridea or Dendrobranchi ...

, notably ''Acetes'' spp.) are most widely consumed in Southeast Asia, where it is fermentation (food), fermented (with the shells intact) and usually ground finely to make shrimp paste. It can be stir-fried and eaten paired with white rice or used to add umami flavors to a wide variety of traditional dishes. The liquid from the fermentation process is also harvested as fish sauce.

Bio-inspired robotics

Krill are agile swimmers in the intermediate Reynolds number regime, in which there are not many solutions for uncrewed underwater robotics, and have inspired robotic platforms to both study their locomotion as well as find design solutions for underwater robots.See also

*Antarctic krill

Antarctic krill (''Euphausia superba'') is a species of krill found in the Antarctica, Antarctic waters of the Southern Ocean. It is a small, swimming crustacean that lives in large schools, called swarms, sometimes reaching densities of 10,000Ō ...

* Cold-water shrimp

* Crustacean

* Krill fishery

* Krill oil

* Northern krill

Northern krill (''Meganyctiphanes norvegica'') is a species of krill that lives in the North Atlantic Ocean including the Norwegian Sea, North Sea, and parts of the Mediterranean. It is an important component of the zooplankton, providing food fo ...

* Krill paradox

References

Further reading

* Boden, Brian P.; Martin W. Johnson, Johnson, Martin W.; Brinton, Edward"Euphausiacea (Crustacea) of the North Pacific"

''Bulletin of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography''. Volume 6 Number 8, 1955. * Edward Brinton, Brinton, Edward

"Euphausiids of Southeast Asian waters"

''Naga Report'' volume 4, part 5. La Jolla: University of California, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, 1975. * Conway, D. V. P.; White, R. G.; Hugues-Dit-Ciles, J.; Galienne, C. P.; Robins, D. B.:

'', [https://web.archive.org/web/20070927161104/http://www.mba.ac.uk/nmbl/publications/occpub/guide/section13.pdf ''Order'' Euphausiacea], Occasional Publication of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom No. 15, Plymouth, UK, 2003. * Everson, I. (ed.): ''Krill: biology, ecology and fisheries''. Oxford, Blackwell Science; 2000. . * * Mauchline, J.

Euphausiacea: ''Adults''

, Conseil International pour l'Exploration de la Mer, 1971. Identification sheets for adult krill with many line drawings. PDF file, 2 Megabyte, Mb. * Mauchline, J.

Euphausiacea: ''Larvae''

, Conseil International pour l'Exploration de la Mer, 1971. Identification sheets for larval stages of krill with many line drawings. PDF file, 3 Mb. * Tett, P.:

', lecture notes from

from Napier University. * Tett, P.:

Bioluminescence

', lecture notes from the 1999/2000 edition of that same course.

External links

Webcam of Krill Aquarium at Australian Antarctic Division

'Antarctic Energies'

animation by Lisa Roberts {{Authority control Krill, Commercial crustaceans Edible crustaceans Extant Early Cretaceous first appearances Taxa named by James Dwight Dana