esoteric knowledge on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Western esotericism, also known as the Western mystery tradition, is a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements that developed within

Western esotericism, also known as the Western mystery tradition, is a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements that developed within

Some scholars have used ''Western esotericism'' to refer to "inner traditions" concerned with a "universal spiritual dimension of reality, as opposed to the merely external ('exoteric') religious institutions and dogmatic systems of established religions." This approach views Western esotericism as just one variant of a worldwide esotericism at the heart of all world religions and cultures, reflecting a hidden esoteric reality. This use is closest to the original meaning of the word in late antiquity, where it applied to secret spiritual teachings that were reserved for a specific elite and hidden from the masses. This definition was popularised in the published work of 19th-century esotericists like A.E. Waite, who sought to combine their own mystical beliefs with a historical interpretation of esotericism. It subsequently became a popular approach within several esoteric movements, most notably

Some scholars have used ''Western esotericism'' to refer to "inner traditions" concerned with a "universal spiritual dimension of reality, as opposed to the merely external ('exoteric') religious institutions and dogmatic systems of established religions." This approach views Western esotericism as just one variant of a worldwide esotericism at the heart of all world religions and cultures, reflecting a hidden esoteric reality. This use is closest to the original meaning of the word in late antiquity, where it applied to secret spiritual teachings that were reserved for a specific elite and hidden from the masses. This definition was popularised in the published work of 19th-century esotericists like A.E. Waite, who sought to combine their own mystical beliefs with a historical interpretation of esotericism. It subsequently became a popular approach within several esoteric movements, most notably

Another approach to Western esotericism treats it as a world view that embraces "enchantment" in contrast to world views influenced by post- Cartesian, post- Newtonian, and positivist science that sought to " dis-enchant" the world. That approach understands esotericism as comprising those world views that eschew a belief in instrumental causality and instead adopt a belief that all parts of the universe are interrelated without a need for causal chains. It stands as a radical alternative to the disenchanted world views that have dominated Western culture since the

Another approach to Western esotericism treats it as a world view that embraces "enchantment" in contrast to world views influenced by post- Cartesian, post- Newtonian, and positivist science that sought to " dis-enchant" the world. That approach understands esotericism as comprising those world views that eschew a belief in instrumental causality and instead adopt a belief that all parts of the universe are interrelated without a need for causal chains. It stands as a radical alternative to the disenchanted world views that have dominated Western culture since the

The origins of Western esotericism are in the Hellenistic Eastern Mediterranean, then part of the

The origins of Western esotericism are in the Hellenistic Eastern Mediterranean, then part of the

A distinct strain of esoteric thought developed in Germany, where it became known as ''

A distinct strain of esoteric thought developed in Germany, where it became known as ''

''Thule-Gesellschaft''

. which later became the

In the 1960s and 1970s, esotericism came to be increasingly associated with the growing counter-culture in the West, whose adherents understood themselves in participating in a spiritual revolution that marked the

In the 1960s and 1970s, esotericism came to be increasingly associated with the growing counter-culture in the West, whose adherents understood themselves in participating in a spiritual revolution that marked the

The academic study of Western esotericism was pioneered in the early 20th century by historians of the ancient world and the European Renaissance, who came to recognise that—even though previous scholarship had ignored it—the effect of pre-Christian and non-rational schools of thought on European society and culture was worthy of academic attention. One of the key centres for this was the

The academic study of Western esotericism was pioneered in the early 20th century by historians of the ancient world and the European Renaissance, who came to recognise that—even though previous scholarship had ignored it—the effect of pre-Christian and non-rational schools of thought on European society and culture was worthy of academic attention. One of the key centres for this was the

Aries: Journal for the Study of Western Esotericism

', Leiden: Brill, since 2001. *

Aries Book Series: Texts and Studies in Western Esotericism

'', Leiden: Brill, since 2006. *

'', East Lansing, Michigan State University (MSU). An online resource since 1999

VIII (2006)

IX (2007)

* * * * * Hanegraaff, Wouter J.,

The Study of Western Esotericism: New Approaches to Christian and Secular Culture

", in Peter Antes, Armin W. Geertz and Randi R. Warne, ''New Approaches to the Study of Religion'', vol. I: ''Regional, Critical, and Historical Approaches'', Berlin / New York: Walter de Gruyter, 2004. * * * Kelley, James L., ''Anatomyzing Divinity: Studies in Science, Esotericism and Political Theology'', Trine Day, 2011, . * Martin, Pierre, ''Esoterische Symbolik heute – in Alltag. Sprache und Einweihung''. Basel: Edition Oriflamme, 2010, illustrated . * Martin, Pierre, ''Le Symbolisme Esotérique Actuel – au Quotidien, dans le Langage et pour l'Auto-initiation''. Basel: Edition Oriflamme, 2011, illustrated * * *

Center for History of Hermetic Philosophy and Related Currents

University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Association for the Study of Esotericism (ASE)European Society for the Study of Western Esotericism (ESSWE)Centre for Magic and Esotericism

University of Exeter, United Kingdom

Aries: Journal for the Study of Western Esotericism''Esoterica'' academic journalThe Secret History of Western Esotericism Podcast (SHWEP)

* {{Western culture Western Esotericism, Western

Western esotericism, also known as the Western mystery tradition, is a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements that developed within

Western esotericism, also known as the Western mystery tradition, is a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements that developed within Western society

Western culture, also known as Western civilization, European civilization, Occidental culture, Western society, or simply the West, refers to the Cultural heritage, internally diverse culture of the Western world. The term "Western" encompas ...

. These ideas and currents are united since they are largely distinct both from orthodox Judeo-Christian religion and Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the Epistemology, epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "the position that reason has precedence over other ways of acquiring knowledge", often in contrast to ot ...

. It has influenced, or contributed to, various forms of Western philosophy

Western philosophy refers to the Philosophy, philosophical thought, traditions and works of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the Pre ...

, mysticism

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute (philosophy), Absolute, but may refer to any kind of Religious ecstasy, ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or Spirituality, spiritual meani ...

, religion

Religion is a range of social system, social-cultural systems, including designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics in religion, ethics, or ...

, science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

, pseudoscience

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable cl ...

, art

Art is a diverse range of cultural activity centered around ''works'' utilizing creative or imaginative talents, which are expected to evoke a worthwhile experience, generally through an expression of emotional power, conceptual ideas, tec ...

, literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, Play (theatre), plays, and poetry, poems. It includes both print and Electroni ...

, and music

Music is the arrangement of sound to create some combination of Musical form, form, harmony, melody, rhythm, or otherwise Musical expression, expressive content. Music is generally agreed to be a cultural universal that is present in all hum ...

.

The idea of grouping a wide range of Western traditions and philosophies together under the term ''esotericism'' developed in 17th-century Europe. Various academics have debated numerous definitions of Western esotericism. One view adopts a definition from certain esotericist schools of thought themselves, treating "esotericism" as a perennial

In horticulture, the term perennial ('' per-'' + '' -ennial'', "through the year") is used to differentiate a plant from shorter-lived annuals and biennials. It has thus been defined as a plant that lives more than 2 years. The term is also ...

hidden inner tradition

A tradition is a system of beliefs or behaviors (folk custom) passed down within a group of people or society with symbolic meaning or special significance with origins in the past. A component of cultural expressions and folklore, common e ...

. A second perspective sees esotericism as a category of movements that embrace an "enchanted" worldview in the face of increasing disenchantment. A third views Western esotericism as encompassing all of Western culture's "rejected knowledge" that is accepted neither by the scientific establishment nor orthodox religious authorities.

The earliest traditions of Western esotericism emerged in the Eastern Mediterranean

The Eastern Mediterranean is a loosely delimited region comprising the easternmost portion of the Mediterranean Sea, and well as the adjoining land—often defined as the countries around the Levantine Sea. It includes the southern half of Turkey ...

during Late Antiquity

Late antiquity marks the period that comes after the end of classical antiquity and stretches into the onset of the Early Middle Ages. Late antiquity as a period was popularized by Peter Brown (historian), Peter Brown in 1971, and this periodiza ...

, where Hermeticism

Hermeticism, or Hermetism, is a philosophical and religious tradition rooted in the teachings attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, a syncretism, syncretic figure combining elements of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth. This system e ...

, Gnosticism

Gnosticism (from Ancient Greek language, Ancient Greek: , Romanization of Ancient Greek, romanized: ''gnōstikós'', Koine Greek: Help:IPA/Greek, �nostiˈkos 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems that coalesced ...

and Neoplatonism

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common id ...

developed as schools of thought distinct from what became mainstream Christianity. Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

Europe saw increasing interest in many of these older ideas, with various intellectuals combining pagan

Paganism (, later 'civilian') is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Christianity, Judaism, and Samaritanism. In the time of the ...

philosophies with the Kabbalah

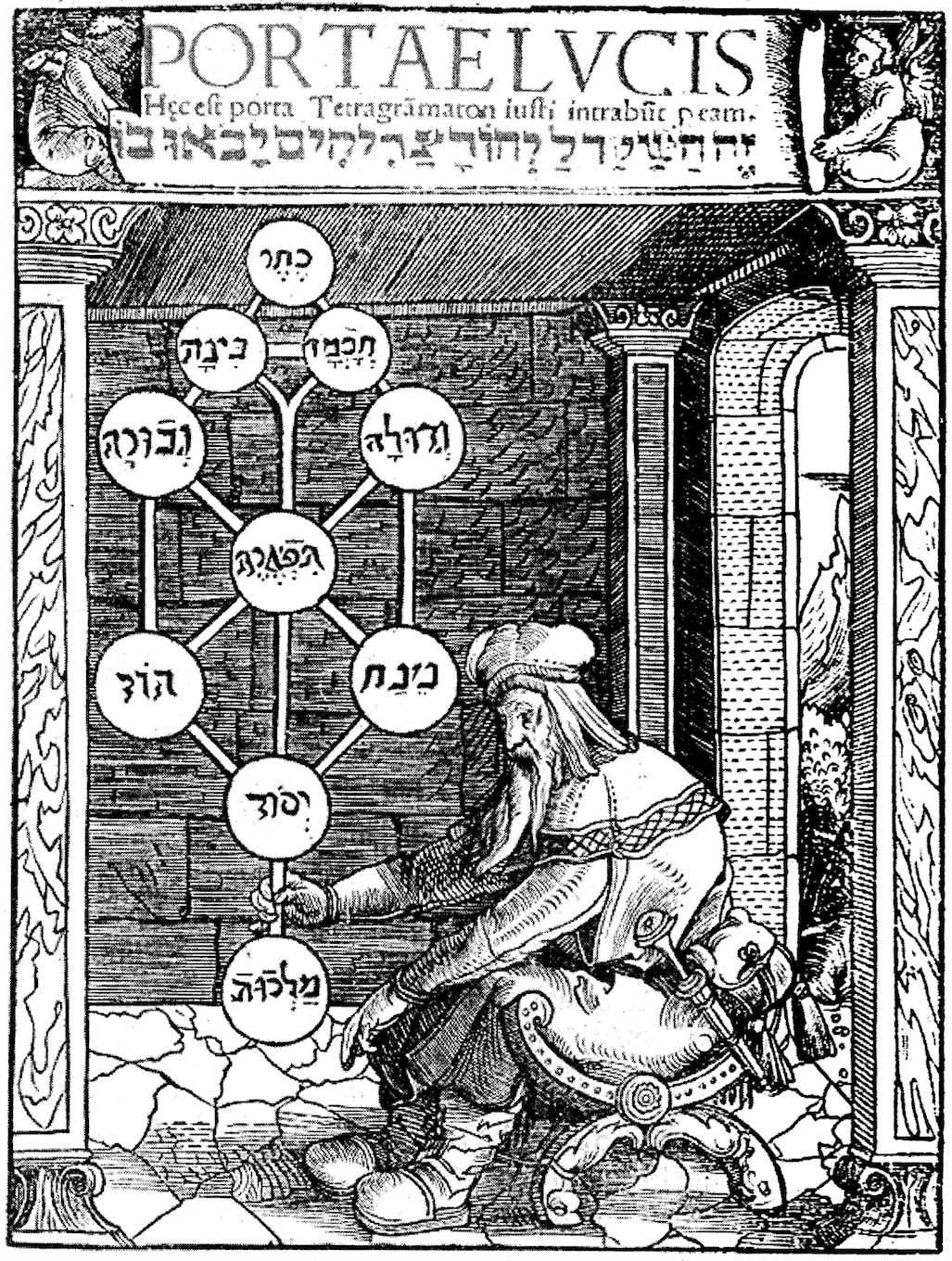

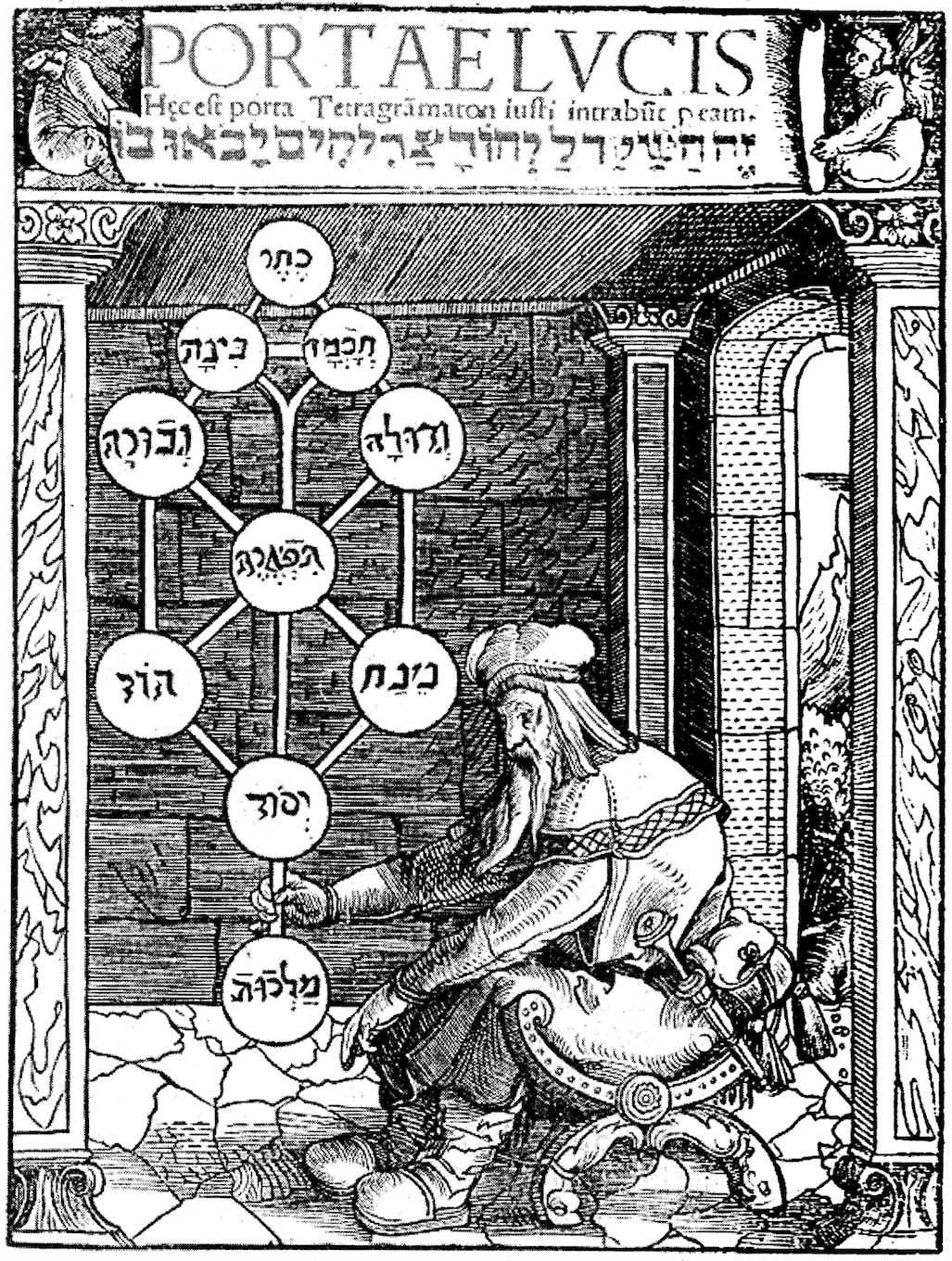

Kabbalah or Qabalah ( ; , ; ) is an esoteric method, discipline and school of thought in Jewish mysticism. It forms the foundation of Mysticism, mystical religious interpretations within Judaism. A traditional Kabbalist is called a Mekubbal ...

and Christian philosophy, resulting in the emergence of esoteric movements like Christian Kabbalah

Christian Kabbalah arose during the Renaissance due to Christian scholars' interest in the mysticism of Kabbalah, Jewish Kabbalah, which they interpreted according to Christian theology. Often spelled Cabala to distinguish it from the Jewish for ...

and Christian theosophy

Christian theosophy, also known as Boehmian theosophy and theosophy, refers to a range of positions within Christianity that focus on the attainment of direct, unmediated knowledge of the nature of divinity and the origin and purpose of the unive ...

. The 17th century saw the development of initiatory societies professing esoteric knowledge such as Rosicrucianism

Rosicrucianism () is a spiritual and cultural movement that arose in early modern Europe in the early 17th century after the publication of several texts announcing to the world a new esoteric order. Rosicrucianism is symbolized by the Rose ...

and Freemasonry

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

, while the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

of the 18th century led to the development of new forms of esoteric thought. The 19th century saw the emergence of new trends of esoteric thought now known as occultism

The occult () is a category of esoteric or supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of organized religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving a 'hidden' or 'secret' agency, such as magic and mystic ...

. Significant groups in this century included the Societas Rosicruciana in Anglia

Societas Rosicruciana in Anglia (Rosicrucian Society of England) or SRIA is a Rosicrucian esoteric Christianity, esoteric Christian order formed by Robert Wentworth Little between 1865King 1989, page 28 and 1867. While the SRIA is not a Masonic ...

, the Theosophical Society

The Theosophical Society is the organizational body of Theosophy, an esoteric new religious movement. It was founded in New York City, U.S.A. in 1875. Among its founders were Helena Blavatsky, a Russian mystic and the principal thinker of the ...

and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn

The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn (), more commonly the Golden Dawn (), was a secret society devoted to the study and practice of occult Hermeticism and metaphysics during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Known as a magical order, ...

. Also important in this connection is Martinus Thomsen

Martinus Thomsen, referred to as Martinus, (11 August 1890 – 8 March 1981) was a Danish people, Danish author. Born into a poor family and with a limited education, Martinus claimed to have had a profound Spirituality, spiritual experience in M ...

's " spiritual science". Modern paganism

Modern paganism, also known as contemporary paganism and neopaganism, spans a range of new religious movements variously influenced by the Paganism, beliefs of pre-modern peoples across Europe, North Africa, and the Near East. Despite some comm ...

developed within occultism and includes religious movements such as Wicca

Wicca (), also known as "The Craft", is a Modern paganism, modern pagan, syncretic, Earth religion, Earth-centred religion. Considered a new religious movement by Religious studies, scholars of religion, the path evolved from Western esote ...

. Esoteric ideas permeated the counterculture of the 1960s

The counterculture of the 1960s was an anti-establishment cultural phenomenon and political movement that developed in the Western world during the mid-20th century. It began in the early 1960s, and continued through the early 1970s. It is ofte ...

and later cultural tendencies, which led to the New Age

New Age is a range of Spirituality, spiritual or Religion, religious practices and beliefs that rapidly grew in Western world, Western society during the early 1970s. Its highly eclecticism, eclectic and unsystematic structure makes a precise d ...

phenomenon in the 1970s.

The idea that these disparate movements could be classified as "Western esotericism" developed in the late 18th century, but these esoteric currents were largely ignored as a subject of academic enquiry. The academic study of Western esotericism only emerged in the late 20th century, pioneered by scholars like Frances Yates and Antoine Faivre

Antoine Faivre (5 June 1934 – 19 December 2021) was a French scholar of Western esotericism. He played a major role in the founding of the discipline as a scholarly field of study, and he was the first-ever person to be appointed to an academ ...

.

Etymology

The concept of the "esoteric" originated in the 2nd century with the coining of theAncient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

adjective

An adjective (abbreviations, abbreviated ) is a word that describes or defines a noun or noun phrase. Its semantic role is to change information given by the noun.

Traditionally, adjectives are considered one of the main part of speech, parts of ...

("belonging to an inner circle"); the earliest known example of the word appeared in a satire authored by Lucian of Samosata

Lucian of Samosata (Λουκιανὸς ὁ Σαμοσατεύς, 125 – after 180) was a Hellenized Syria (region), Syrian satire, satirist, rhetorician and pamphleteer who is best known for his characteristic tongue-in-cheek style, with whi ...

( – after 180).

In the 15th and 16th centuries, differentiations in Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

between ''exotericus'' and ''esotericus'' (along with ''internus'' and ''externus'') were common in the scholar discourse on ancient philosophy. The categories of ''doctrina vulgaris'' and ''doctrina arcana'' are found among Cambridge Platonists

The Cambridge Platonists were an influential group of Platonist philosophers and Christian theologians at the University of Cambridge that existed during the 17th century. The leading figures were Ralph Cudworth and Henry More.

Group and its nam ...

. Perhaps for the first time in English, Thomas Stanley, between 1655 and 1660, would refer to the Pythagorean ''exoterick'' and ''esoterick''. John Toland

John Toland (30 November 167011 March 1722) was an Irish rationalist philosopher and freethinker, and occasional satirist, who wrote numerous books and pamphlets on political philosophy and philosophy of religion, which are early expressions ...

in 1720 would state that the so-called nowadays "esoteric distinction" was a universal phenomenon, present in both the West and the East. As for the noun "esotericism", probably the first mention in German of ''Esoterismus'' appeared in a 1779 work by Johann Georg Hamann

Johann Georg Hamann (; ; 27 August 1730 – 21 June 1788) was a German Lutheran philosopher from Königsberg known as "the Wizard of the North" who was one of the leading figures of post-Kantian philosophy. His work was used by his student J. G ...

, and the use of ''Esoterik'' in 1790 by Johann Gottfried Eichhorn

Johann Gottfried Eichhorn (16 October 1752, in Dörrenzimmern – 27 June 1827, in Göttingen) was a German Protestant theologian of the Enlightenment and an early orientalist. He was a member of the Göttingen school of history.

Education and ...

. But the word ''esoterisch'' had already existed at least since 1731–1736, as found in the works of Johann Jakob Brucker

Johann Jakob Brucker (; ; 22 January 1696 – 26 November 1770) was a German historian of philosophy.

Life

He was born at Augsburg. He was destined for the Lutheran Church, and graduated at the University of Jena in 1718. He returned to Augsburg ...

; this author rejected everything that is characterized today as an "esoteric corpus". In this 18th century context, these terms referred to Pythagoreanism

Pythagoreanism originated in the 6th century BC, based on and around the teachings and beliefs held by Pythagoras and his followers, the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras established the first Pythagorean community in the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek co ...

or Neoplatonic theurgy

Theurgy (; from the Greek θεουργία ), also known as divine magic, is one of two major branches of the magical arts, Pierre A. Riffard, ''Dictionnaire de l'ésotérisme'', Paris: Payot, 1983, 340. the other being practical magic or thau ...

, but the concept was particularly sedimentated by two streams of discourses: speculations about the influences of the Egyptians on ancient philosophy and religion, and their associations with Masonic

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

discourses and other secret societies, who claimed to keep such ancient secrets until the Enlightenment; and the emergence of orientalist academic studies, which since the 17th century identified the presence of mysteries, secrets or esoteric "ancient wisdom" in Persian, Arab, Indian and Far Eastern texts and practices (see also Early Western reception of Eastern esotericism).

The noun

In grammar, a noun is a word that represents a concrete or abstract thing, like living creatures, places, actions, qualities, states of existence, and ideas. A noun may serve as an Object (grammar), object or Subject (grammar), subject within a p ...

"esotericism" (in its French form "ésotérisme") first appeared in 1828 in the work by Protestant historian of gnosticism Jacques Matter (1791–1864), (3 vols.).

The term "esotericism" thus came into use in the wake of the Age of Enlightenment and of its critique of institutionalised religion, during which alternative religious groups such as the Rosicrucians

Rosicrucianism () is a spirituality, spiritual and cultural movement that arose in early modern Europe in the early 17th century after the publication of several texts announcing to the world a new Western esotericism, esoteric order. Rosicruc ...

began to disassociate themselves from the dominant Christianity in Western Europe. During the 19th and 20th centuries, scholars increasingly saw the term "esotericism" as meaning something distinct from Christianity—as a subculture at odds with the Christian mainstream from at least the time of the Renaissance. After being introduced by Jacques Matter in French, the occultist and ceremonial magician Eliphas Lévi (1810–1875) popularized the term in the 1850s. Lévi also introduced the term , a notion that he developed against the background of contemporary socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

and Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

discourses. "Esotericism" and "occultism" were often employed as synonyms until later scholars distinguished the concepts.

Philosophical usage

In the context ofAncient Greek philosophy

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC. Philosophy was used to make sense of the world using reason. It dealt with a wide variety of subjects, including astronomy, epistemology, mathematics, political philosophy, ethics, metaphysics ...

, the terms "esoteric" and "exoteric" were sometimes used by scholars not to denote that there was secrecy, but to distinguish two procedures of research and education: the first reserved for teachings that were developed "within the walls" of the philosophical school, among a circle of thinkers ("eso-" indicating what is unseen, as in the classes internal to the institution), and the second referring to those whose works were disseminated to the public in speeches and published ("exo-": outside). The initial meaning of this last word is implied when Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

coined the term "exoteric speeches" (), perhaps to refer to the speeches he gave outside his school.

However, Aristotle never employed the term "esoteric" and there is no evidence that he dealt with specialized secrets; there is a dubious report by Aulus Gellius

Aulus Gellius (c. 125after 180 AD) was a Roman author and grammarian, who was probably born and certainly brought up in Rome. He was educated in Athens, after which he returned to Rome. He is famous for his ''Attic Nights'', a commonplace book, ...

, according to which Aristotle disclosed the exoteric subjects of politics, rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse ( trivium) along with grammar and logic/ dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or w ...

and ethics to the general public in the afternoon, while he reserved the morning for "akroatika" (acroamatics), referring to natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

and logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

, taught during a walk with his students. Furthermore, the term "exoteric" for Aristotle could have another meaning, hypothetically referring to an extracosmic reality, ''ta exo'', superior to and beyond Heaven, requiring abstraction and logic. This reality stood in contrast to what he called ''enkyklioi logoi,'' knowledge "from within the circle", involving the intracosmic physics that surrounds everyday life. There is a report by Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-si ...

and Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

, however, which states that the Lyceum's school texts were circulated internally, their publication was more controlled than the exoteric ones, and that these "esoteric" texts were rediscovered and compiled only with the efforts of Andronicus of Rhodes

Andronikos of Rhodes (; ; ) was a Greek philosopher from Rhodes who was also the scholarch (head) of the Peripatetic school. He is most famous for publishing a new edition of the works of Aristotle that forms the basis of the texts that survive t ...

.

Plato would have orally transmitted intramural teachings to his disciples, the supposed "esoteric" content of which regarding the First Principles is particularly highlighted by the Tübingen School

Tübingen (; ) is a traditional university city in central Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is situated south of the state capital, Stuttgart, and developed on both sides of the Neckar and Ammer rivers. about one in three of the 90,000 people ...

as distinct from the apparent written teachings conveyed in his books or public lectures. Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a 19th-century German idealism, German idealist. His influence extends across a wide range of topics from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political phi ...

commented on the analysis of this distinction in the modern hermeneutics

Hermeneutics () is the theory and methodology of interpretation, especially the interpretation of biblical texts, wisdom literature, and philosophical texts. As necessary, hermeneutics may include the art of understanding and communication.

...

of Plato and Aristotle:

To express an external object not much is required, but to communicate an idea a capacity must be present, and this always remains something esoteric, so that there has never been anything purely exoteric about what philosophers say.In any case, drawing from the tradition of discourses that supposedly revealed a vision of the

absolute

Absolute may refer to:

Companies

* Absolute Entertainment, a video game publisher

* Absolute Radio, (formerly Virgin Radio), independent national radio station in the UK

* Absolute Software Corporation, specializes in security and data risk ma ...

and truth present in mythology

Myth is a genre of folklore consisting primarily of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society. For scholars, this is very different from the vernacular usage of the term "myth" that refers to a belief that is not true. Instead, the ...

and initiatory rites of mystery religions

Mystery religions, mystery cults, sacred mysteries or simply mysteries (), were religious schools of the Greco-Roman world for which participation was reserved to initiates ''(mystai)''. The main characteristic of these religious schools was th ...

, Plato and his philosophy began the Western perception of esotericism, to the point that Kocku von Stuckrad stated "esoteric ontology and anthropology would hardly exist without Platonic philosophy." In his dialogues, he uses expressions that refer to cultic secrecy (for example, , , one of the Ancient Greek expressions referring to the prohibition of revealing a secret, in the context of mysteries). In '' Theaetetus'' 152c, there is an example of this concealment strategy:

Can it be, then, thatTheProtagoras Protagoras ( ; ; )Guthrie, p. 262–263. was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher and rhetorical theorist. He is numbered as one of the sophists by Plato. In his dialogue '' Protagoras'', Plato credits him with inventing the role of the professional ...was a very ingenious person who threw out this obscure utterance for the unwashed like us but reserved the truth as a secret doctrine (ἐν ἀπορρήτῳ τὴν ἀλήθειαν) to be revealed to his disciples?

Neoplatonists

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common i ...

intensified the search for a "hidden truth" under the surface of teachings, myths and texts, developing the hermeneutics and allegorical exegesis of Plato, Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

, Orpheus

In Greek mythology, Orpheus (; , classical pronunciation: ) was a Thracians, Thracian bard, legendary musician and prophet. He was also a renowned Ancient Greek poetry, poet and, according to legend, travelled with Jason and the Argonauts in se ...

and others. Plutarch, for example, developed the justification of a theological esotericism, and Numenius wrote "On the Secrets of Plato" (''Peri tôn para Platoni aporrhèta'').

Probably based on the "exôtikos/esôtikos" dichotomy, the Hellenic world developed the classical distinction between exoteric/esoteric, stimulated by criticism from various currents such as the Patristics

Patristics, also known as Patrology, is a branch of theological studies focused on the writings and teachings of the Church Fathers, between the 1st to 8th centuries CE. Scholars analyze texts from both orthodox and heretical authors. Patristics e ...

. According to examples in Lucian, Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus (; September 129 – AD), often Anglicization, anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Ancient Rome, Roman and Greeks, Greek physician, surgeon, and Philosophy, philosopher. Considered to be one o ...

and Clement of Alexandria

Titus Flavius Clemens, also known as Clement of Alexandria (; – ), was a Christian theology, Christian theologian and philosopher who taught at the Catechetical School of Alexandria. Among his pupils were Origen and Alexander of Jerusalem. A ...

, at that time it was a common practice among philosophers to keep secret writings and teachings. A parallel secrecy and reserved elite was also found in the contemporary environment of Gnosticism

Gnosticism (from Ancient Greek language, Ancient Greek: , Romanization of Ancient Greek, romanized: ''gnōstikós'', Koine Greek: Help:IPA/Greek, �nostiˈkos 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems that coalesced ...

. Later, Iamblichus

Iamblichus ( ; ; ; ) was a Neoplatonist philosopher who determined a direction later taken by Neoplatonism. Iamblichus was also the biographer of the Greek mystic, philosopher, and mathematician Pythagoras. In addition to his philosophical co ...

would present his definition (close to the modern one), as he classified the ancient Pythagoreans

Pythagoreanism originated in the 6th century BC, based on and around the teachings and beliefs held by Pythagoras and his followers, the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras established the first Pythagorean community in the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek co ...

as either "exoteric" mathematicians or "esoteric" acousmatics, the latter being those who disseminated enigmatic teachings and hidden allegorical meanings.

Conceptual development

The concept of "Western esotericism" represents a modern scholarly construct rather than a pre-existing, self-defined tradition of thought. In the late 17th century, several European Christian thinkers presented the argument that one could categorise certain traditions of Western philosophy and thought together, thus establishing the category now labelled "Western esotericism". The first to do so, (1659–1698), a GermanLutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

theologian, wrote ''Platonisch-Hermetisches Christianity'' (1690–91). A hostile critic of various currents of Western thought that had emerged since the Renaissance—among them Paracelsianism, Weigelianism, and Christian theosophy

Christian theosophy, also known as Boehmian theosophy and theosophy, refers to a range of positions within Christianity that focus on the attainment of direct, unmediated knowledge of the nature of divinity and the origin and purpose of the unive ...

—in his book he labelled all of these traditions under the category of "Platonic–Hermetic Christianity", portraying them as heretical

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Christianity, Judai ...

to what he saw as "true" Christianity. Despite his hostile attitude toward these traditions of thought, Colberg became the first to connect these disparate philosophies and to study them under one rubric, also recognising that these ideas linked back to earlier philosophies from late antiquity

Late antiquity marks the period that comes after the end of classical antiquity and stretches into the onset of the Early Middle Ages. Late antiquity as a period was popularized by Peter Brown (historian), Peter Brown in 1971, and this periodiza ...

.

In 18th-century Europe, during the Age of Enlightenment, these esoteric traditions came to be regularly categorised under the labels of "superstition

A superstition is any belief or practice considered by non-practitioners to be irrational or supernatural, attributed to fate or magic (supernatural), magic, perceived supernatural influence, or fear of that which is unknown. It is commonly app ...

", "magic

Magic or magick most commonly refers to:

* Magic (supernatural), beliefs and actions employed to influence supernatural beings and forces

** ''Magick'' (with ''-ck'') can specifically refer to ceremonial magic

* Magic (illusion), also known as sta ...

", and "the occult

''The Occult: A History'' is a 1971 nonfiction occult book by English writer, Colin Wilson. Topics covered include Aleister Crowley, George Gurdjieff, Helena Blavatsky, Kabbalah, primitive magic, Franz Mesmer, Grigori Rasputin, Daniel Dunglas H ...

"—terms often used interchangeably. The modern academy, then in the process of developing, consistently rejected and ignored topics coming under "the occult", thus leaving research into them largely to enthusiasts outside of academia. Indeed, according to historian of esotericism Wouter J. Hanegraaff (born 1961), rejection of "occult" topics was seen as a "crucial identity marker" for any intellectuals seeking to affiliate themselves with the academy.

Scholars established this category in the late 18th century after identifying "structural similarities" between "the ideas and world views of a wide variety of thinkers and movements" that, previously, had not been in the same analytical grouping. According to the scholar of esotericism Wouter J. Hanegraaff, the term provided a "useful generic label" for "a large and complicated group of historical phenomena that had long been perceived as sharing an ''air de famille''."

Various academics have emphasised that esotericism is a phenomenon unique to the Western world. As Faivre stated, an "empirical perspective" would hold that "esotericism is a Western notion." As scholars such as Faivre and Hanegraaff have pointed out, there is no comparable category of "Eastern" or "Oriental" esotericism. The emphasis on ''Western'' esotericism was nevertheless primarily devised to distinguish the field from a ''universal'' esotericism. Hanegraaff has characterised these as "recognisable world views and approaches to knowledge that have played an important though always controversial role in the history of Western culture". Historian of religion Henrik Bogdan asserted that Western esotericism constituted "a third pillar of Western culture" alongside "doctrinal faith and rationality", being deemed heretical by the former and irrational by the latter. Scholars nevertheless recognise that various non-Western traditions have exerted "a profound influence" over Western esotericism, citing the example of the Theosophical Society

The Theosophical Society is the organizational body of Theosophy, an esoteric new religious movement. It was founded in New York City, U.S.A. in 1875. Among its founders were Helena Blavatsky, a Russian mystic and the principal thinker of the ...

's incorporation of Hindu

Hindus (; ; also known as Sanātanīs) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism, also known by its endonym Sanātana Dharma. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pp. 35–37 Historically, the term has also be ...

and Buddhist

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

concepts like reincarnation

Reincarnation, also known as rebirth or transmigration, is the Philosophy, philosophical or Religion, religious concept that the non-physical essence of a living being begins a new lifespan (disambiguation), lifespan in a different physical ...

into its doctrines. Given these influences and the imprecise nature of the term "Western", the scholar of esotericism Kennet Granholm has argued that academics should cease referring to "''Western'' esotericism" altogether, instead simply favouring "esotericism" as a descriptor of this phenomenon. Egil Asprem has endorsed this approach.

Definition

The historian of esotericismAntoine Faivre

Antoine Faivre (5 June 1934 – 19 December 2021) was a French scholar of Western esotericism. He played a major role in the founding of the discipline as a scholarly field of study, and he was the first-ever person to be appointed to an academ ...

noted that "never a precise term, sotericismhas begun to overflow its boundaries on all sides", with both Faivre and Karen-Claire Voss stating that Western esotericism consists of "a vast spectrum of authors, trends, works of philosophy, religion, art, literature, and music".

Scholars broadly agree on which currents of thought fall within a category of ''esotericism''—ranging from ancient Gnosticism and Hermeticism through to Rosicrucianism

Rosicrucianism () is a spiritual and cultural movement that arose in early modern Europe in the early 17th century after the publication of several texts announcing to the world a new esoteric order. Rosicrucianism is symbolized by the Rose ...

and the Kabbalah

Kabbalah or Qabalah ( ; , ; ) is an esoteric method, discipline and school of thought in Jewish mysticism. It forms the foundation of Mysticism, mystical religious interpretations within Judaism. A traditional Kabbalist is called a Mekubbal ...

and on to more recent phenomenon such as the New Age

New Age is a range of Spirituality, spiritual or Religion, religious practices and beliefs that rapidly grew in Western world, Western society during the early 1970s. Its highly eclecticism, eclectic and unsystematic structure makes a precise d ...

movement. Nevertheless, ''esotericism'' itself remains a controversial term, with scholars specialising in the subject disagreeing as to how best to define it.

As a universal secret inner tradition

Some scholars have used ''Western esotericism'' to refer to "inner traditions" concerned with a "universal spiritual dimension of reality, as opposed to the merely external ('exoteric') religious institutions and dogmatic systems of established religions." This approach views Western esotericism as just one variant of a worldwide esotericism at the heart of all world religions and cultures, reflecting a hidden esoteric reality. This use is closest to the original meaning of the word in late antiquity, where it applied to secret spiritual teachings that were reserved for a specific elite and hidden from the masses. This definition was popularised in the published work of 19th-century esotericists like A.E. Waite, who sought to combine their own mystical beliefs with a historical interpretation of esotericism. It subsequently became a popular approach within several esoteric movements, most notably

Some scholars have used ''Western esotericism'' to refer to "inner traditions" concerned with a "universal spiritual dimension of reality, as opposed to the merely external ('exoteric') religious institutions and dogmatic systems of established religions." This approach views Western esotericism as just one variant of a worldwide esotericism at the heart of all world religions and cultures, reflecting a hidden esoteric reality. This use is closest to the original meaning of the word in late antiquity, where it applied to secret spiritual teachings that were reserved for a specific elite and hidden from the masses. This definition was popularised in the published work of 19th-century esotericists like A.E. Waite, who sought to combine their own mystical beliefs with a historical interpretation of esotericism. It subsequently became a popular approach within several esoteric movements, most notably Martinism

Martinism is a form of Christian mysticism and esoteric Christianity concerned with the fall of the first man, his materialistic state of being, deprived of his own, divine source, and the process of his eventual (if not inevitable) return, call ...

and Traditionalism

Traditionalism is the adherence to traditional beliefs or practices. It may also refer to:

Religion

* Traditional religion, a religion or belief associated with a particular ethnic group

* Traditionalism (19th-century Catholicism), a 19th-cen ...

.

This definition, originally developed by esotericists themselves, became popular among French academics during the 1980s, exerting a strong influence over the scholars Mircea Eliade

Mircea Eliade (; – April 22, 1986) was a Romanian History of religion, historian of religion, fiction writer, philosopher, and professor at the University of Chicago. One of the most influential scholars of religion of the 20th century and in ...

, Henry Corbin

Henry Corbin (14 April 1903 – 7 October 1978) was a French philosopher, theologian, and Iranologist, professor of Islamic studies at the École pratique des hautes études. He was influential in extending the modern study of traditional Islami ...

, and the early work of Faivre. Within the academic field of religious studies

Religious studies, also known as religiology or the study of religion, is the study of religion from a historical or scientific perspective. There is no consensus on what qualifies as ''religion'' and definition of religion, its definition is h ...

, those who study different religions in search of an inner universal dimension to them all are termed "religionists". Such religionist ideas also exerted an influence on more recent scholars like Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke

Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke (15 January 195329 August 2012) was a British historian and professor of Western esotericism at the University of Exeter, best known for his authorship of several scholarly books on the history of Germany between the W ...

and Arthur Versluis

Arthur Versluis (born 1959) is a professor and Department Chair of Religious Studies in the College of Arts & Letters at Michigan State University.

Academic career

Versluis did his Ph.D research at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. His thesis ...

.

Versluis for instance defined "Western esotericism" as "inner or hidden spiritual knowledge transmitted through Western European historical currents that in turn feed into North American and other non-European settings". He added that these Western esoteric currents all shared a core characteristic, "a claim to gnosis

Gnosis is the common Greek noun for knowledge ( γνῶσις, ''gnōsis'', f.). The term was used among various Hellenistic religions and philosophies in the Greco-Roman world. It is best known for its implication within Gnosticism, where ...

, or direct spiritual insight into cosmology or spiritual insight", and accordingly he suggested that these currents could be referred to as "Western gnostic" just as much as "Western esoteric".

There are various problems with this model for understanding Western esotericism. The most significant is that it rests upon the conviction that there really is a "universal, hidden, esoteric dimension of reality" that objectively exists. The existence of this universal inner tradition has not been discovered through scientific or scholarly enquiry; this had led some to claim that it does not exist, though Hanegraaff thought it better to adopt a view based in methodological agnosticism by stating that "we simply do not know—and cannot know" if it exists or not. He noted that, even if such a true and absolute nature of reality really existed, it would only be accessible through "esoteric" spiritual practices, and could not be discovered or measured by the "exoteric" tools of scientific and scholarly enquiry. Hanegraaff pointed out that an approach that seeks a common inner hidden core of all esoteric currents masks that such groups often differ greatly, being rooted in their own historical and social contexts and expressing mutually exclusive ideas and agendas. A third issue was that many of those currents widely recognised as esoteric never concealed their teachings, and in the 20th century came to permeate popular culture, thus problematizing the claim that esotericism could be defined by its hidden and secretive nature. He noted that when scholars adopt this definition, it shows that they subscribe to the religious doctrines espoused by the very groups they are studying.

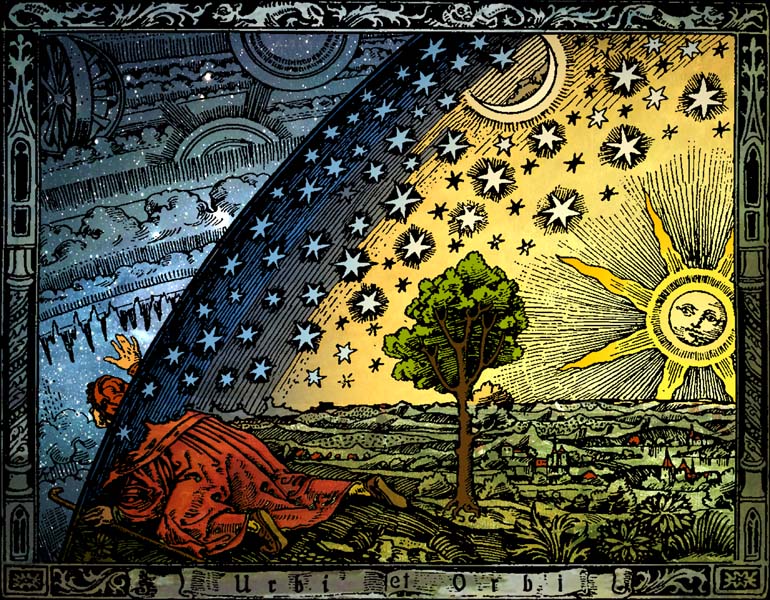

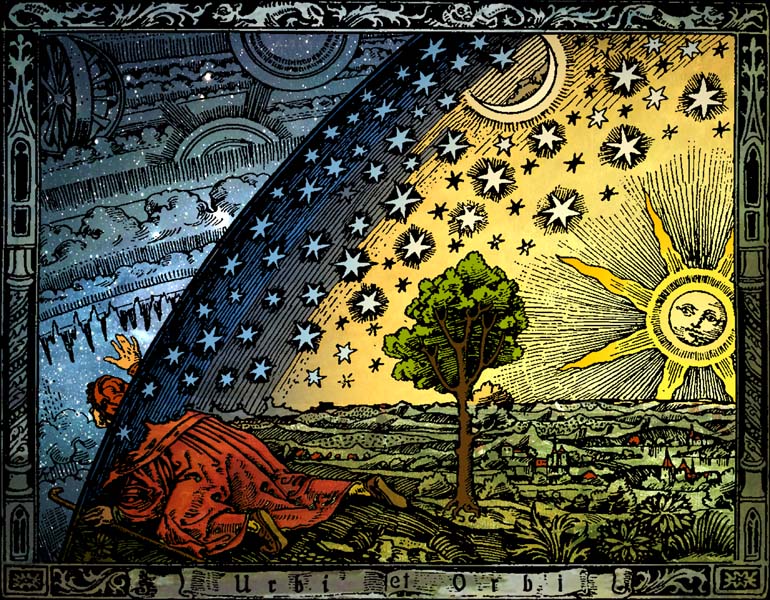

As an enchanted world view

Another approach to Western esotericism treats it as a world view that embraces "enchantment" in contrast to world views influenced by post- Cartesian, post- Newtonian, and positivist science that sought to " dis-enchant" the world. That approach understands esotericism as comprising those world views that eschew a belief in instrumental causality and instead adopt a belief that all parts of the universe are interrelated without a need for causal chains. It stands as a radical alternative to the disenchanted world views that have dominated Western culture since the

Another approach to Western esotericism treats it as a world view that embraces "enchantment" in contrast to world views influenced by post- Cartesian, post- Newtonian, and positivist science that sought to " dis-enchant" the world. That approach understands esotericism as comprising those world views that eschew a belief in instrumental causality and instead adopt a belief that all parts of the universe are interrelated without a need for causal chains. It stands as a radical alternative to the disenchanted world views that have dominated Western culture since the Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of History of science, modern science during the early modern period, when developments in History of mathematics#Mathematics during the Scientific Revolution, mathemati ...

, and must therefore always be at odds with secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin , or or ), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. The origins of secularity can be traced to the Bible itself. The concept was fleshed out through Christian hi ...

culture.

An early exponent of this definition was the historian of Renaissance thought Frances Yates in her discussions of a ''Hermetic Tradition'', which she saw as an "enchanted" alternative to established religion and rationalistic science. The primary exponent of this view was Faivre, who published a series of criteria for how to define "Western esotericism" in 1992. Faivre claimed that esotericism was "identifiable by the presence of six fundamental characteristics or components", four of which were "intrinsic" and thus vital to defining something as being esoteric, while the other two were "secondary" and thus not necessarily present in every form of esotericism. He listed these characteristics as follows:

# "Correspondences": This is the idea that there are both real and symbolic correspondences existing between all things within the universe. As examples for this, Faivre pointed to the esoteric concept of the macrocosm and microcosm, often presented as the dictum of "as above, so below", as well as the astrological idea that the actions of the planets have a direct corresponding influence on the behaviour of human beings.

# "Living Nature": Faivre argued that all esotericists envision the natural universe as being imbued with its own life force, and that as such they understand it as being "complex, plural, hierarchical".

# "Imagination and Mediations": Faivre believed that all esotericists place great emphasis on both the human imagination

Imagination is the production of sensations, feelings and thoughts informing oneself. These experiences can be re-creations of past experiences, such as vivid memories with imagined changes, or completely invented and possibly fantastic scenes ...

, and mediations—"such as rituals, symbolic images, mandalas, intermediary spirits"—and mantras as tools that provide access to worlds and levels of reality existing between the material world and the divine.

# "Experience of Transmutation": Faivre's fourth intrinsic characteristic of esotericism was the emphasis that esotericists place on fundamentally transforming themselves through their practice, for instance through the spiritual transformation that is alleged to accompany the attainment of gnosis

Gnosis is the common Greek noun for knowledge ( γνῶσις, ''gnōsis'', f.). The term was used among various Hellenistic religions and philosophies in the Greco-Roman world. It is best known for its implication within Gnosticism, where ...

.

# "Practice of Concordance": The first of Faivre's secondary characteristics of esotericism was the belief—held by many esotericists, such as those in the Traditionalist School

Traditionalism, also known as the Traditionalist School, is a school of thought within perennial philosophy. Originating in the thought of René Guénon in the 20th century, it proposes that a single primordial, metaphysical truth forms the so ...

—that there is a fundamental unifying principle or root from which all world religions and spiritual practices emerge. The common esoteric principle is that attaining this unifying principle can bring the world's different belief systems together in unity.

# "Transmission": Faivre's second secondary characteristic was the emphasis on the transmission of esoteric teachings and secrets from a master to their disciple, through a process of initiation

Initiation is a rite of passage marking entrance or acceptance into a group or society. It could also be a formal admission to adulthood in a community or one of its formal components. In an extended sense, it can also signify a transformatio ...

.

Faivre's form of categorisation has been endorsed by scholars like Goodrick-Clarke, and by 2007 Bogdan could note that Faivre's had become "the standard definition" of Western esotericism in use among scholars. In 2013 the scholar Kennet Granholm stated only that Faivre's definition had been "the dominating paradigm for a long while" and that it "still exerts influence among scholars outside the study of Western esotericism". The advantage of Faivre's system is that it facilitates comparing varying esoteric traditions "with one another in a systematic fashion." Other scholars criticised his theory, pointing out various weaknesses. Hanegraaff claimed that Faivre's approach entailed "reasoning by prototype" in that it relied upon already having a "best example" of what Western esotericism should look like, against which other phenomena then had to be compared. The scholar of esotericism Kocku von Stuckrad (born 1966) noted that Faivre's taxonomy was based on his own areas of specialism—Renaissance Hermeticism, Christian Kabbalah, and Protestant Theosophy—and that it was thus not based on a wider understanding of esotericism as it has existed throughout history, from the ancient world to the contemporary period. Accordingly, Von Stuckrad suggested that it was a good typology for understanding "Christian esotericism in the early modern period

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

" but lacked utility beyond that.

As higher knowledge

As an alternative to Faivre's framework, Kocku von Stuckrad developed his own variant, though he argued that this did not represent a "definition" but rather "a framework of analysis" for scholarly usage. He stated that "on the most general level of analysis", esotericism represented "the claim of higher knowledge", a claim to possessing "wisdom that is superior to other interpretations of cosmos and history" that serves as a "master key for answering all questions of humankind." Accordingly, he believed that esoteric groups placed a great emphasis on secrecy, not because they were inherently rooted in elite groups but because the idea of concealed secrets that can be revealed was central to their discourse. Examining the means of accessing higher knowledge, he highlighted two themes that he believed could be found within esotericism, that of mediation through contact with non-human entities, and individual experience. Accordingly, for Von Stuckrad, esotericism could be best understood as "a structural element of Western culture" rather than as a selection of different schools of thought.As rejected knowledge

Hanegraaff proposed an additional definition that "Western esotericism" is a category that represents "the academy's dustbin of rejected knowledge." In this respect, it contains all of the theories and world views rejected by the mainstream intellectual community because they do not accord with "normative conceptions of religion, rationality and science." His approach is rooted within the field of thehistory of ideas

Intellectual history (also the history of ideas) is the study of the history of human thought and of intellectuals, people who conceptualize, discuss, write about, and concern themselves with ideas. The investigative premise of intellectual hist ...

, and stresses the role of change and transformation over time.

Goodrick-Clarke was critical of this approach, believing that it relegated Western esotericism to the position of "a casualty of positivist and materialist perspectives in the nineteenth-century" and thus reinforces the idea that Western esoteric traditions were of little historical importance. Bogdan similarly expressed concern regarding Hanegraaff's definition, believing that it made the category of Western esotericism "all inclusive" and thus analytically useless.

History

Late Antiquity

The origins of Western esotericism are in the Hellenistic Eastern Mediterranean, then part of the

The origins of Western esotericism are in the Hellenistic Eastern Mediterranean, then part of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

, during Late Antiquity

Late antiquity marks the period that comes after the end of classical antiquity and stretches into the onset of the Early Middle Ages. Late antiquity as a period was popularized by Peter Brown (historian), Peter Brown in 1971, and this periodiza ...

. This was a milieu that mixed religious and intellectual traditions from Greece, Egypt, the Levant, Babylon, and Persia—in which globalisation

Globalization is the process of increasing interdependence and integration among the economies, markets, societies, and cultures of different countries worldwide. This is made possible by the reduction of barriers to international trade, th ...

, urbanisation, and multiculturalism

Multiculturalism is the coexistence of multiple cultures. The word is used in sociology, in political philosophy, and colloquially. In sociology and everyday usage, it is usually a synonym for ''Pluralism (political theory), ethnic'' or cultura ...

were bringing about socio-cultural change.

One component of this was Hermeticism, an Egyptian Hellenistic school of thought that takes its name from the legendary Egyptian wise man, Hermes Trismegistus

Hermes Trismegistus (from , "Hermes the Thrice-Greatest") is a legendary Hellenistic period figure that originated as a syncretic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth.A survey of the literary and archaeological eviden ...

. In the 2nd and 3rd centuries, a number of texts attributed to Hermes Trismegistus appeared, including the ''Corpus Hermeticum

The is a collection of 17 Greek writings whose authorship is traditionally attributed to the legendary Hellenistic figure Hermes Trismegistus, a syncretic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth. The treatises were orig ...

'', ''Asclepius

Asclepius (; ''Asklēpiós'' ; ) is a hero and god of medicine in ancient Religion in ancient Greece, Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology. He is the son of Apollo and Coronis (lover of Apollo), Coronis, or Arsinoe (Greek myth), Ars ...

'', and ''The Discourse on the Eighth and Ninth

''The Discourse on the Eighth and Ninth'' is an ancient Hermetic treatise. It is one of the three short texts attributed to the legendary Hellenistic figure Hermes Trismegistus that were discovered among the Nag Hammadi findings.

Insufficient ...

''. Some still debate whether Hermeticism was a purely literary phenomenon or had communities of practitioners who acted on these ideas, but it has been established that these texts discuss the true nature of God, emphasising that humans must transcend rational thought and worldly desires to find salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its c ...

and be reborn into a spiritual body of immaterial light, thereby achieving spiritual unity with divinity.

Another tradition of esoteric thought in Late Antiquity was Gnosticism. Various Gnostic sects existed, and they broadly believed that the divine light had been imprisoned within the material world by a malevolent entity known as the Demiurge

In the Platonic, Neopythagorean, Middle Platonic, and Neoplatonic schools of philosophy, the Demiurge () is an artisan-like figure responsible for fashioning and maintaining the physical universe. Various sects of Gnostics adopted the term '' ...

, who was served by demonic helpers, the Archons

''Archon'' (, plural: , ''árchontes'') is a Greek word that means "ruler", frequently used as the title of a specific public office. It is the masculine present participle of the verb stem , meaning "to be first, to rule", derived from the same ...

. It was the Gnostic belief that people, who were imbued with the divine light, should seek to attain gnosis and thus escape from the world of matter and rejoin the divine source.

A third form of esotericism in Late Antiquity was Neoplatonism

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common id ...

, a school of thought influenced by the ideas of the philosopher Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

. Advocated by such figures as Plotinus

Plotinus (; , ''Plōtînos''; – 270 CE) was a Greek Platonist philosopher, born and raised in Roman Egypt. Plotinus is regarded by modern scholarship as the founder of Neoplatonism. His teacher was the self-taught philosopher Ammonius ...

, Porphyry, Iamblichus

Iamblichus ( ; ; ; ) was a Neoplatonist philosopher who determined a direction later taken by Neoplatonism. Iamblichus was also the biographer of the Greek mystic, philosopher, and mathematician Pythagoras. In addition to his philosophical co ...

, and Proclus

Proclus Lycius (; 8 February 412 – 17 April 485), called Proclus the Successor (, ''Próklos ho Diádokhos''), was a Greek Neoplatonist philosopher, one of the last major classical philosophers of late antiquity. He set forth one of th ...

, Neoplatonism held that the human soul had fallen from its divine origins into the material world, but that it could progress, through a number of hierarchical spheres of being, to return to its divine origins once more. The later Neoplatonists performed theurgy

Theurgy (; from the Greek θεουργία ), also known as divine magic, is one of two major branches of the magical arts, Pierre A. Riffard, ''Dictionnaire de l'ésotérisme'', Paris: Payot, 1983, 340. the other being practical magic or thau ...

, a ritual practice attested in such sources as the ''Chaldean Oracles

The ''Chaldean Oracles'' are a set of spiritual and philosophical texts widely used by Neoplatonist philosophers from the 3rd to the 6th century CE. While the original texts have been lost, they have survived in the form of fragments consisting m ...

''. Scholars are still unsure of precisely what theurgy involved, but know it involved a practice designed to make gods appear, who could then raise the theurgist's mind to the reality of the divine.

Middle Ages

After thefall of Rome

The fall of the Western Roman Empire, also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome, was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vast ...

, alchemy

Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

and philosophy and other aspects of the tradition were largely preserved in the Arab and Near Eastern world and reintroduced into Western Europe by Jews and by the cultural contact between Christians and Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

s in Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

and southern Italy. The 12th century saw the development of the Kabbalah in southern Italy and medieval Spain

Spain in the Middle Ages is a period in the history of Spain that began in the 5th century following the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ended with the beginning of the early modern period in 1492.

The history of Spain is marked by waves o ...

.

The medieval period

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

also saw the publication of grimoire

A grimoire () (also known as a book of spells, magic book, or a spellbook) is a textbook of magic, typically including instructions on how to create magical objects like talismans and amulets, how to perform magical spells, charms, and divin ...

s, which offered often elaborate formulas for theurgy

Theurgy (; from the Greek θεουργία ), also known as divine magic, is one of two major branches of the magical arts, Pierre A. Riffard, ''Dictionnaire de l'ésotérisme'', Paris: Payot, 1983, 340. the other being practical magic or thau ...

and thaumaturgy

Thaumaturgy () is the practical application of magic to effect change in the physical world. Historically, thaumaturgy has been associated with the manipulation of natural forces, the creation of wonders, and the performance of magical feats t ...

. Many of the grimoires seem to have kabbalistic influence. Figures in alchemy from this period seem to also have authored or used grimoires. Medieval sects deemed heretical such as the Waldensians

The Waldensians, also known as Waldenses (), Vallenses, Valdesi, or Vaudois, are adherents of a church tradition that began as an ascetic movement within Western Christianity before the Reformation. Originally known as the Poor of Lyon in the l ...

were thought to have utilized esoteric concepts.

Renaissance and Early Modern period

During theRenaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

, a number of European thinkers began to synthesize "pagan

Paganism (, later 'civilian') is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Christianity, Judaism, and Samaritanism. In the time of the ...

" (that is, not Christian) philosophies, which were then being made available through Arabic translations, with Christian thought and the Jewish kabbalah. The earliest of these individuals was the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

philosopher Plethon

Georgios Gemistos Plethon (; /1360 – 1452/1454), commonly known as Gemistos Plethon, was a Byzantine Greeks, Greek scholar and one of the most renowned philosophers of the Late Byzantine era. He was a chief pioneer of the revival of Greek scho ...

(1355/60–1452?), who argued that the ''Chaldean Oracles'' represented an example of a superior religion of ancient humanity that had been passed down by the Platonists

Platonism is the philosophy of Plato and philosophical systems closely derived from it, though contemporary Platonists do not necessarily accept all doctrines of Plato. Platonism has had a profound effect on Western thought. At the most fundam ...

.

Plethon's ideas interested the ruler of Florence, Cosimo de' Medici

Cosimo di Giovanni de' Medici (27 September 1389 – 1 August 1464) was an Italian banker and politician who established the House of Medici, Medici family as effective rulers of Florence during much of the Italian Renaissance. His power derive ...

, who employed Florentine thinker Marsilio Ficino

Marsilio Ficino (; Latin name: ; 19 October 1433 – 1 October 1499) was an Italian scholar and Catholic priest who was one of the most influential humanist philosophers of the early Italian Renaissance. He was an astrologer, a reviver of Neo ...

(1433–1499) to translate Plato's works into Latin. Ficino went on to translate and publish the works of various Platonic figures, arguing that their philosophies were compatible with Christianity, and allowing for the emergence of a wider movement in Renaissance Platonism, or Platonic Orientalism. Ficino also translated part of the ''Corpus Hermeticum

The is a collection of 17 Greek writings whose authorship is traditionally attributed to the legendary Hellenistic figure Hermes Trismegistus, a syncretic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth. The treatises were orig ...

'', though the rest was translated by his contemporary, Lodovico Lazzarelli

Ludovico Lazzarelli (4 February 1447 – 23 June 1500) was an Italian poet, philosopher, courtier, hermeticist and (likely) magician (paranormal), magician and diviner of the early Renaissance.

Born at San Severino Marche, he had contact with ma ...

(1447–1500).

Another core figure in this intellectual milieu was Giovanni Pico della Mirandola

Giovanni Pico dei conti della Mirandola e della Concordia ( ; ; ; 24 February 146317 November 1494), known as Pico della Mirandola, was an Italian Renaissance nobleman and philosopher. He is famed for the events of 1486, when, at the age of 23, ...

(1463–1494), who achieved notability in 1486 by inviting scholars from across Europe to come and debate with him 900 theses that he had written. Pico della Mirandola argued that all of these philosophies reflected a grand universal wisdom. Pope Innocent VIII

Pope Innocent VIII (; ; 1432 – 25 July 1492), born Giovanni Battista Cybo (or Cibo), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 29 August 1484 to his death, in July 1492. Son of the viceroy of Naples, Cybo spent his ea ...

condemned these ideas, criticising him for attempting to mix pagan and Jewish ideas with Christianity.

Pico della Mirandola's increased interest in Jewish kabbalah led to his development of a distinct form of Christian Kabbalah

Christian Kabbalah arose during the Renaissance due to Christian scholars' interest in the mysticism of Kabbalah, Jewish Kabbalah, which they interpreted according to Christian theology. Often spelled Cabala to distinguish it from the Jewish for ...

. His work was built on by the German Johannes Reuchlin (1455–1522) who authored an influential text on the subject, '' De Arte Cabalistica''. Christian Kabbalah was expanded in the work of the German Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (; ; 14 September 1486 – 18 February 1535) was a German Renaissance polymath, physician, legal scholar, soldier, knight, theologian, and occult writer. Agrippa's ''Three Books of Occult Philosophy'' pub ...

(1486–1535/36), who used it as a framework to explore the philosophical and scientific traditions of Antiquity in his work '' De occulta philosophia libri tres''. The work of Agrippa and other esoteric philosophers had been based in a pre-Copernican worldview, but following the arguments of Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

, a more accurate understanding of the cosmos was established. Copernicus' theories were adopted into esoteric strains of thought by Giordano Bruno

Giordano Bruno ( , ; ; born Filippo Bruno; January or February 1548 – 17 February 1600) was an Italian philosopher, poet, alchemist, astrologer, cosmological theorist, and esotericist. He is known for his cosmological theories, which concep ...

(1548–1600), whose ideas were deemed heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Heresy in Christian ...

by the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, which eventually publicly executed him.

Naturphilosophie

"''Naturphilosophie''" (German for "nature-philosophy") is a term used in English-language philosophy to identify a current in the philosophical tradition of German idealism, as applied to the study of nature in the earlier 19th century. German ...

''. Though influenced by traditions from Late Antiquity

Late antiquity marks the period that comes after the end of classical antiquity and stretches into the onset of the Early Middle Ages. Late antiquity as a period was popularized by Peter Brown (historian), Peter Brown in 1971, and this periodiza ...

and medieval Kabbalah, it only acknowledged two main sources of authority: Biblical scripture and the natural world. The primary exponent of this approach was Paracelsus

Paracelsus (; ; 1493 – 24 September 1541), born Theophrastus von Hohenheim (full name Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim), was a Swiss physician, alchemist, lay theologian, and philosopher of the German Renaissance.

H ...