Cuba–United States relations on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Relations between the

Relations between the

Jane Franklin. Ocean Press; 1997. . The desire to procure Cuba intensified in the 1840s, not only in the context of manifest destiny but also in the interest of Southern power. Cuba, with some half a million slaves, would provide Southerners with extra leverage in Congress. In the late 1840s, President The Cuban rebellion 1868–1878 against Spanish rule, called by historians the

The Cuban rebellion 1868–1878 against Spanish rule, called by historians the

After some rebel successes in Cuba's second war of independence in 1897, U.S. President

After some rebel successes in Cuba's second war of independence in 1897, U.S. President

In April 1961, an armed invasion by about 1,500 CIA trained Cuban exiles at the

In April 1961, an armed invasion by about 1,500 CIA trained Cuban exiles at the  A U.S. Senate Select Intelligence Committee report later confirmed over eight attempted plots to kill Castro between 1960 and 1965, as well as additional plans against other Cuban leaders. After weathering the failed Bay of Pigs invasion, Cuba observed as U.S. armed forces staged a mock invasion of a

A U.S. Senate Select Intelligence Committee report later confirmed over eight attempted plots to kill Castro between 1960 and 1965, as well as additional plans against other Cuban leaders. After weathering the failed Bay of Pigs invasion, Cuba observed as U.S. armed forces staged a mock invasion of a  In 1977, Cuba and the United States signed a maritime boundary treaty, agreeing on the location of their

In 1977, Cuba and the United States signed a maritime boundary treaty, agreeing on the location of their

Miami Herald April 19, 2001 Long-term consensus between Latin American nations has not emerged.Cuba, the U.N. Human Rights Commission and the OAS Race

Council on Hemispheric Affairs By the

In January 2006,

In January 2006,

In 2003, the United States

In 2003, the United States

In April 2009, Obama, who had received nearly half of the Cuban Americans vote in the 2008 presidential election, began implementing a less strict policy towards Cuba. Obama stated that he was open to dialogue with Cuba, but that he would only lift the trade embargo if Cuba underwent political change. In March 2009, Obama signed into law a congressional spending bill which eased some economic sanctions on Cuba and eased travel restrictions on Cuban-Americans (defined as persons with a relative "who is no more than three generations removed from that person") traveling to Cuba. The April executive decision further removed time limits on Cuban-American travel to the island. Another restriction loosened in April 2009 was in the realm of

In April 2009, Obama, who had received nearly half of the Cuban Americans vote in the 2008 presidential election, began implementing a less strict policy towards Cuba. Obama stated that he was open to dialogue with Cuba, but that he would only lift the trade embargo if Cuba underwent political change. In March 2009, Obama signed into law a congressional spending bill which eased some economic sanctions on Cuba and eased travel restrictions on Cuban-Americans (defined as persons with a relative "who is no more than three generations removed from that person") traveling to Cuba. The April executive decision further removed time limits on Cuban-American travel to the island. Another restriction loosened in April 2009 was in the realm of  Beginning in 2013, Cuban and U.S. officials held secret talks brokered in part by

Beginning in 2013, Cuban and U.S. officials held secret talks brokered in part by

The U.S. continues to operate a naval base at

The U.S. continues to operate a naval base at

Excerpt

*Bergad, Laird W. ''Histories of Slavery in Brazil, Cuba, and the United States'' (Cambridge U. Press, 2007). 314 pp. * Bernell, David. ''Constructing US foreign policy: The curious case of Cuba'' (2012). * Freedman, Lawrence. ''Kennedy's Wars: Berlin, Cuba, Laos, and Vietnam'' (Oxford UP, 2000) * Grenville, John A. S. and George Berkeley Young. ''Politics, Strategy, and American Diplomacy: Studies in Foreign Policy, 1873-1917'' (1966) pp 179–200 on "The dangers of Cuban independence: 1895-1897" * Hernández, Jose M. ''Cuba and the United States: Intervention and Militarism, 1868–1933'' (2013) * Horne, Gerald. ''Race to Revolution: The United States and Cuba during Slavery and Jim Crow.'' New York: Monthly Review Press, 2014. * Jones, Howard. ''The Bay of Pigs'' (Oxford University Press, 2008) * Laguardia Martinez, Jacqueline et al. ''Changing Cuba-U.S. Relations: Implications for CARICOM States'' (2019

online

* LeoGrande, William M. "Enemies evermore: US policy towards Cuba after Helms-Burton." ''Journal of Latin American Studies'' 29.1 (1997): 211–221

Online

* LeoGrande, William M. and

Excerpt

* Mackinnon, William P. "Hammering Utah, Squeezing Mexico, and Coveting Cuba: James Buchanan's White House Intriques" ''Utah Historical Quarterly'', 80#2 (2012), pp. 132–15 https://doi.org/10.2307/45063308 in 1850s * Offner, John L. ''An Unwanted War: The Diplomacy of the United States and Spain over Cuba, 1895–1898'' (U of North Carolina Press, 1992

online free to borrow

*Pérez, Louis A., Jr. ''Cuba and the United States: Ties of Singular Intimacy'' (2003

online free to borrow

* Sáenz, Eduardo, and Rovner Russ Davidson, eds. ''The Cuban Connection: Drug Trafficking, Smuggling, and Gambling in Cuba from the 1920s to the Revolution'' (U of North Carolina Press, 2008) * Smith, Wayne. ''The Closest of Enemies: A Personal and Diplomatic History of the Castro Years'' (1988), by American diplomat in Havana * Welch, Richard E. ''Response to Revolution: The United States and the Cuban Revolution, 1959–1961'' (U of North Carolina Press, 1985) * White, Nigel D. "Ending the US embargo of Cuba: international law in dispute." ''Journal of Latin American Studies'' 51.1 (2019): 163–186

Online

History of Cuba – U.S. relationsPost-Soviet Relations Between Cuba and the US

from th

Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital ArchivesCold War International History Project: Primary Document Collection on US-Cuban Relations

*BBC

Timeline: US-Cuba RelationsU.S. Commission for Assistance to a Free Cuba

* ttp://www.democracynow.org/2014/10/2/secret_history_of_us_cuba_ties Secret History of U.S.-Cuba Ties Reveals Henry Kissinger Plan to Bomb Havana for Fighting Apartheid '' Democracy Now!'' 2 October 2014. {{DEFAULTSORT:Cuba-United States Relations

Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

restored diplomatic relations on July 20, 2015. Relations had been severed in 1961 during the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

. U.S. diplomatic representation in Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

is handled by the United States Embassy in Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

, and there is a similar Cuban Embassy in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

The United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, however, continues to maintain its commercial, economic, and financial embargo, making it illegal for U.S. corporations to do business with Cuba.

Relations began in early colonial times and were focused around extensive trade. In the 19th century, manifest destiny

Manifest destiny was a cultural belief in the 19th century in the United States, 19th-century United States that American settlers were destined to expand across North America.

There were three basic tenets to the concept:

* The special vir ...

increasingly led to American desire to buy, conquer, or otherwise take some control of Cuba. This included an attempt to buy it from Spain in 1848 during the Polk administration

The presidency of James K. Polk began on March 4, 1845, when James K. Polk was United States presidential inauguration, inaugurated as President of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1849. He was a Democratic Party (United States), Democrat, ...

, and a secret attempt to buy it in 1854 during the Pierce administration

The presidency of Franklin Pierce began on March 4, 1853, when Franklin Pierce was inaugurated, and ended on March 4, 1857. Pierce, a Democrat from New Hampshire, took office as the 14th United States president after routing Whig Party nominee ...

known as the Ostend Manifesto, which backfired, caused a scandal and severely weakened Pierce's presidency. The hold of the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

on possessions in the Americas had already been reduced in the 1820s as a result of the Spanish American wars of independence

The Spanish American wars of independence (25 September 1808 – 29 September 1833; es, Guerras de independencia hispanoamericanas) were numerous wars in Spanish America with the aim of political independence from Spanish rule during the early ...

; only Cuba and Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and Unincorporated ...

remained under Spanish rule until the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

(1898) that resulted from the Cuban War of Independence

The Cuban War of Independence (), fought from 1895 to 1898, was the last of three liberation wars that Cuba fought against Spain, the other two being the Ten Years' War (1868–1878) and the Little War (1879–1880). The final three months ...

. Under the Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

, Cuba became a U.S. protectorate from 1898 to 1902; the U.S. gained a position of economic and political dominance over the island, which persisted after it became formally independent in 1902.

Following the Cuban Revolution of 1959, bilateral relations deteriorated substantially. On August 6, 1960, the Cuban government, under President Osvaldo Dorticós Torrado and Prime Minister Fidel Castro, nationalized all American owned oil refineries located within Cuba's national borders. Along with sugar factories and mines, Cuba seized approximately $1.7 billion in U.S. oil assets. In October 1960, the U.S. imposed and subsequently tightened a comprehensive set of restrictions and bans against the Cuban government, ostensibly in retaliation for the nationalization

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to pri ...

of U.S. corporations' property by Cuba. In 1961 the U.S. severed diplomatic ties with Cuba and attempted to use exiles and Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

officers to invade the country. In November of that year, the U.S. engaged in a campaign of terrorism

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

and covert operations over several years in an attempt to bring down the Cuban government. The terrorist campaign killed a significant number of civilians. In October 1962 the Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

occurred between the U.S. and Soviet Union over Soviet deployments of ballistic missiles in Cuba. Throughout the Cold War, the US heavily countered Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 200 ...

's attempts to "spread communism" throughout Latin America and Africa. The Nixon, Ford, Kennedy, and Johnson administrations resorted to back-channel talks to negotiate with the Cuban government during the Cold War.

In 2014, U.S. President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the U ...

and new Cuban President Raúl Castro

Raúl Modesto Castro Ruz (; ; born 3 June 1931) is a retired Cuban politician and general who served as the first secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba, the most senior position in the one-party communist state, from 2011 to 2021, succeedi ...

(the younger brother of Fidel Castro) announced the beginning of a process of normalizing relations between Cuba and the U.S., which media sources have named "the Cuban Thaw

The Cuban thaw ( es, Deshielo cubano) was the normalization of Cuba–United States relations that began in December 2014 ending a 54-year stretch of hostility between the nations. In March 2016, Barack Obama became the first U.S. president to ...

". Negotiated in secret in Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

and the Vatican City

Vatican City (), officially the Vatican City State ( it, Stato della Città del Vaticano; la, Status Civitatis Vaticanae),—'

* german: Vatikanstadt, cf. '—' (in Austria: ')

* pl, Miasto Watykańskie, cf. '—'

* pt, Cidade do Vati ...

, and with the assistance of Pope Francis

Pope Francis ( la, Franciscus; it, Francesco; es, link=, Francisco; born Jorge Mario Bergoglio, 17 December 1936) is the head of the Catholic Church. He has been the bishop of Rome and sovereign of the Vatican City State since 13 March 2013. ...

, the agreement led to the lifting of some U.S. travel restrictions, fewer restrictions on remittance

A remittance is a non-commercial transfer of money by a foreign worker, a member of a diaspora community, or a citizen with familial ties abroad, for household income in their home country or homeland. Money sent home by migrants competes wit ...

s, access to the Cuban financial system for U.S. banks, and the establishment of a U.S. embassy in Havana, which closed after Cuba became closely allied with the USSR in 1961. The countries' respective "interests sections" in one another's capitals were upgraded to embassies in 2015. In 2016, President Barack Obama visited Cuba, becoming the first sitting U.S. president in 88 years to visit the island.

On June 16, 2017, President Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of Pe ...

announced that he was suspending the policy for unconditional sanctions relief for Cuba, while also leaving the door open for a "better deal" between the U.S. and Cuba. On November 8, 2017, it was announced that the business and travel restrictions which were loosened by the Obama administration

Barack Obama's tenure as the 44th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 2009, and ended on January 20, 2017. A Democrat from Illinois, Obama took office following a decisive victory over Republican ...

would be reinstated and they went into effect on 9 November. On June 4, 2019, the Trump administration

Donald Trump's tenure as the List of presidents of the United States, 45th president of the United States began with Inauguration of Donald Trump, his inauguration on January 20, 2017, and ended on January 20, 2021. Trump, a Republican Party ...

announced new restrictions on American travel to Cuba.

Since taking office in 2021, the Biden administration has been labeled as "tougher than Donald Trump on the island's government," although it has later reversed some of the restrictions placed during the Trump administration. However, in May 2022, the United States refused to invite the island nation to attend the 9th Summit of the Americas, drawing criticism from other Latin American countries.

Historical background

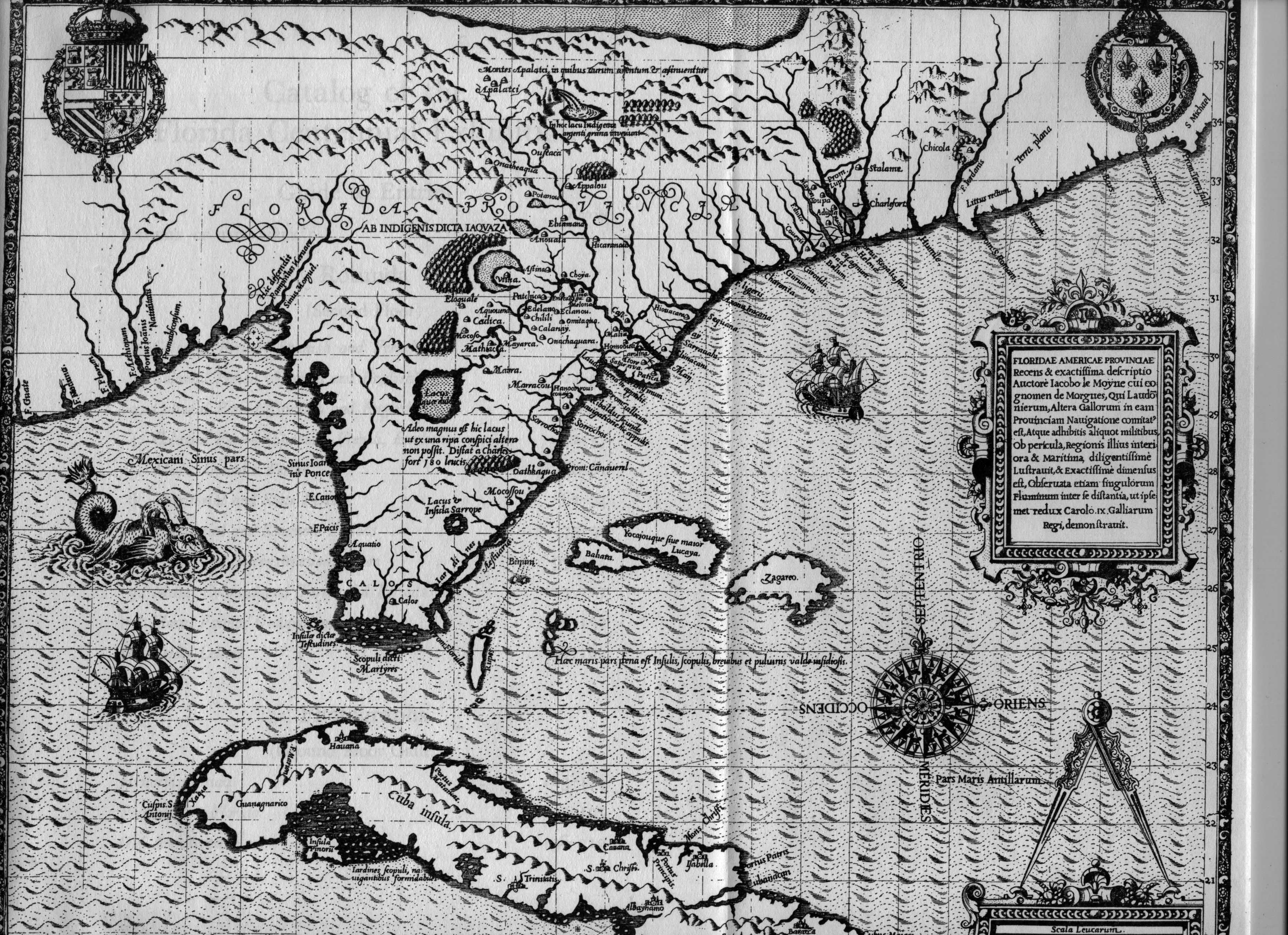

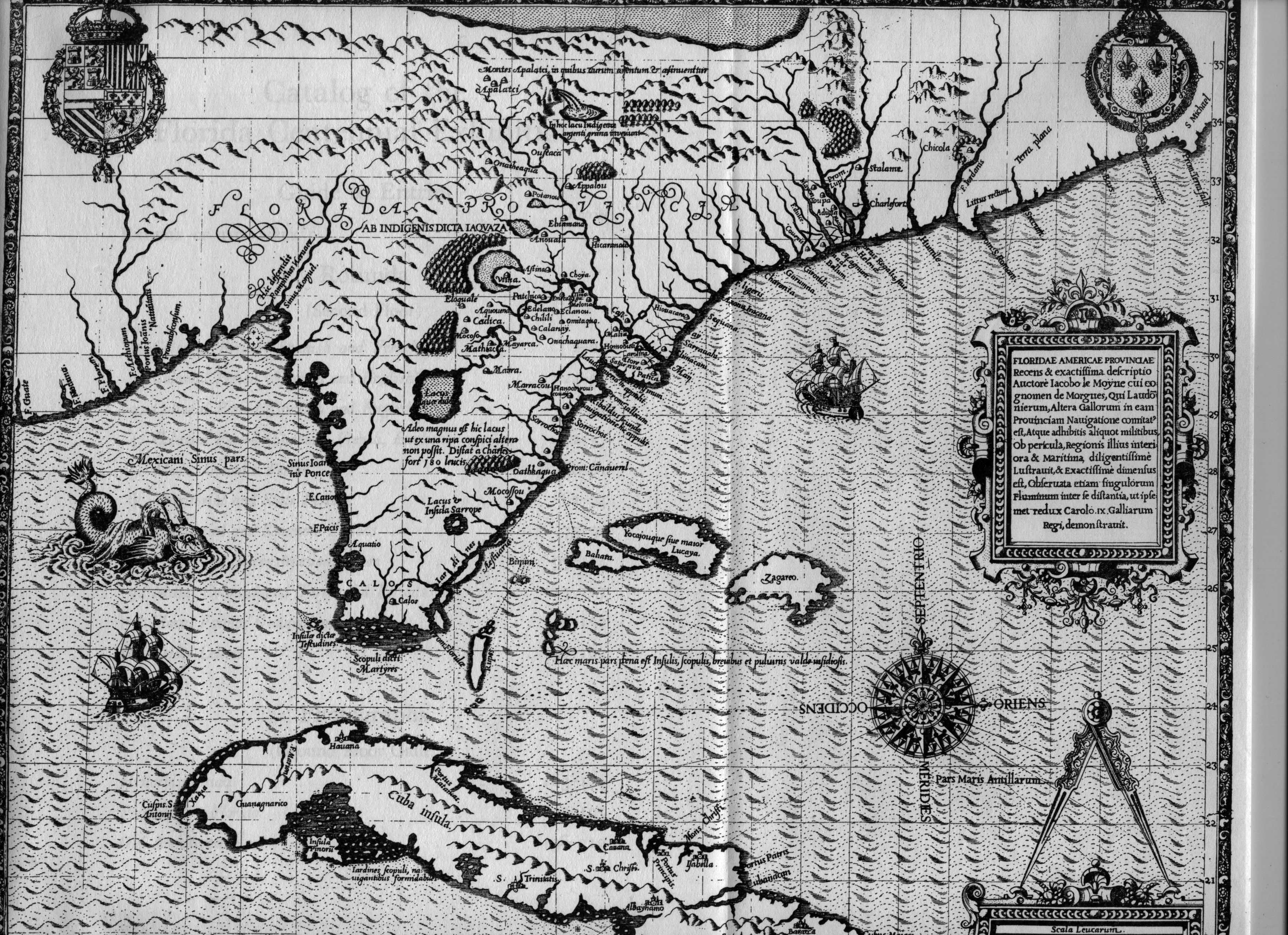

Pre-1800

Relations between the

Relations between the Spanish colony

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its predece ...

of Cuba and polities

A polity is an identifiable political entity – a group of people with a collective identity, who are organized by some form of institutionalized social relations, and have a capacity to mobilize resources. A polity can be any other group of p ...

on the North American mainland first established themselves in the early 18th century through illicit commercial contracts by the European colonies of the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 3 ...

, trading to elude colonial taxes. As both legal and illegal trade increased, Cuba became a comparatively prosperous trading partner in the region, and a center of tobacco and sugar production. During this period Cuban merchants increasingly traveled to North American ports, establishing trade contracts that endured for many years.

The British capture and temporary occupation of Havana in 1762, which many Americans participated in, opened up trade with the colonies in North and South America, and the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

in 1776 provided additional trade opportunities. Spain opened Cuban ports to North American commerce officially in November 1776 and the island became increasingly dependent on that trade.

19th century

After the opening of the island to world trade in 1818, trade agreements began to replace Spanish commercial connections. In 1820Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

thought Cuba is "the most interesting addition which could ever be made to our system of States" and told Secretary of War John C. Calhoun

John Caldwell Calhoun (; March 18, 1782March 31, 1850) was an American statesman and political theorist from South Carolina who held many important positions including being the seventh vice president of the United States from 1825 to 1832. He ...

that the United States "ought, at the first possible opportunity, to take Cuba." In a letter to the U.S. Minister to Spain Hugh Nelson, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams described the likelihood of U.S. "annexation of Cuba" within half a century despite obstacles: "But there are laws of political as well as of physical gravitation; and if an apple severed by the tempest from its native tree cannot choose but fall to the ground, Cuba, forcibly disjoined from its own unnatural connection with Spain, and incapable of self support, can gravitate only towards the North American Union, which by the same law of nature cannot cast her off from its bosom."Cuba and the United States : A chronological HistoryJane Franklin. Ocean Press; 1997. . The desire to procure Cuba intensified in the 1840s, not only in the context of manifest destiny but also in the interest of Southern power. Cuba, with some half a million slaves, would provide Southerners with extra leverage in Congress. In the late 1840s, President

James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. He previously was the 13th speaker of the House of Representatives (1835–1839) and ninth governor of Tennessee (183 ...

dispatched his minister to Spain Romulus Mitchell Saunders

Romulus Mitchell Saunders (March 3, 1791 – April 21, 1867) was an American politician from North Carolina.

Early life and education

Saunders was born near Milton, Caswell County, North Carolina, the son of William and Hannah Mitchell Saunders ...

with a mission to offer $100 million to buy Cuba. Saunders however did not speak Spanish, and as then Secretary of State James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

noted "even nglishhe sometimes murders". Saunders was a clumsy negotiator, which both entertained and angered the Spanish. Spain replied that they would "prefer seeing ubasunk in the ocean" than sold. It may have been a moot point anyway, as it is unlikely that the Whig majority House would have accepted such an obviously pro-Southern move. The 1848 election of Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

, a Whig, ended formal attempts to purchase the island.

In August 1851, 40 Americans who took part in Narciso López's filibustering Lopez Expedition in Cuba, including the Attorney General's nephew William L. Crittenden, were executed by Spanish authorities in Havana. News of the executions caused a furor in the South, spawning riots in which the Spanish consulate in New Orleans was burned to the ground. In 1854, a secret proposal known as the Ostend Manifesto was devised by U.S. diplomats, interested in adding a slave state to the Union. The Manifesto proposed buying Cuba from Spain for $130 million. If Spain were to reject the offer, the Manifesto implied that, in the name of Manifest Destiny

Manifest destiny was a cultural belief in the 19th century in the United States, 19th-century United States that American settlers were destined to expand across North America.

There were three basic tenets to the concept:

* The special vir ...

, war would be necessary. When the plans became public, because of one author's vocal enthusiasm for the plan, the manifesto caused a scandal, and was rejected, in part because of objections from anti-slavery campaigners.

The Cuban rebellion 1868–1878 against Spanish rule, called by historians the

The Cuban rebellion 1868–1878 against Spanish rule, called by historians the Ten Years' War

The Ten Years' War ( es, Guerra de los Diez Años; 1868–1878), also known as the Great War () and the War of '68, was part of Cuba's fight for independence from Spain. The uprising was led by Cuban-born planters and other wealthy natives. O ...

, gained wide sympathy in the United States. Juntas based in New York raised money and smuggled men and munitions to Cuba while energetically spreading propaganda in American newspapers. The Grant administration turned a blind eye to this violation of American neutrality. In 1869, President Ulysses Grant was urged by popular opinion to support rebels in Cuba with military assistance and to give them U.S. diplomatic recognition. Secretary of State Hamilton Fish

Hamilton Fish (August 3, 1808September 7, 1893) was an American politician who served as the 16th Governor of New York from 1849 to 1850, a United States Senator from New York from 1851 to 1857 and the 26th United States Secretary of State fro ...

wanted stability and favored the Spanish government and did not publicly challenge the popular anti-Spanish American viewpoint. Grant and Fish gave lip service to Cuban independence, called for an end to slavery in Cuba, and quietly opposed American military intervention. Fish worked diligently against popular pressure, and was able to keep Grant from officially recognizing Cuban independence because it would have endangered negotiations with Britain over the Alabama Claims

The ''Alabama'' Claims were a series of demands for damages sought by the government of the United States from the United Kingdom in 1869, for the attacks upon Union merchant ships by Confederate Navy commerce raiders built in British shipyards ...

. Daniel Sickles

Daniel Edgar Sickles (October 20, 1819May 3, 1914) was an American politician, soldier, and diplomat.

Born to a wealthy family in New York City, Sickles was involved in a number of scandals, most notably the 1859 homicide of his wife's lover, U. ...

, the American Minister to Madrid, made no headway. Grant and Fish successfully resisted popular pressures. Grant's message to Congress urged strict neutrality and no official recognition of the Cuban revolt.

By 1877, Americans purchased 83 percent of Cuba's total exports. North Americans were also increasingly taking up residence on the island, and some districts on the northern shore were said to have more the character of America than Spanish settlements. Between 1878 and 1898 American investors took advantage of deteriorating economic conditions of the Ten Years' War

The Ten Years' War ( es, Guerra de los Diez Años; 1868–1878), also known as the Great War () and the War of '68, was part of Cuba's fight for independence from Spain. The uprising was led by Cuban-born planters and other wealthy natives. O ...

to take over estates they had tried unsuccessfully to buy before while others acquired properties at very low prices. Above all this presence facilitated the integration of the Cuban economy into the North American system and weakened Cuba's ties with Spain.

1890s: Independence in Cuba

As Cuban resistance to Spanish rule grew, rebels fighting for independence attempted to get support from U.S. PresidentUlysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

. Grant declined and the resistance was curtailed, though American interests in the region continued. U.S. Secretary of State James G. Blaine

James Gillespie Blaine (January 31, 1830January 27, 1893) was an American statesman and Republican politician who represented Maine in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1863 to 1876, serving as Speaker of the U.S. House of Representative ...

wrote in 1881 of Cuba, "that rich island, the key to the Gulf of Mexico, and the field for our most extended trade in the Western Hemisphere, is, though in the hands of Spain, a part of the American commercial system ... If ever ceasing to be Spanish, Cuba must necessarily become American and not fall under any other European domination." After some rebel successes in Cuba's second war of independence in 1897, U.S. President

After some rebel successes in Cuba's second war of independence in 1897, U.S. President William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

offered to buy Cuba for $300 million. Rejection of the offer, and an explosion that sank the American battleship USS ''Maine'' in Havana harbor, led to the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

. In Cuba the war became known as "the U.S. intervention in Cuba's War of Independence". On 10 December 1898 Spain and the United States signed the Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

and, in accordance with the treaty, Spain renounced all rights to Cuba. The treaty put an end to the Spanish Empire in the Americas and marked the beginning of United States expansion and long-term political dominance in the region. Immediately after the signing of the treaty, the U.S.-owned "Island of Cuba Real Estate Company" opened for business to sell Cuban land to Americans. U.S. military rule of the island lasted until 1902 when Cuba was finally granted formal independence.

Relations from 1900–1959

TheTeller Amendment

The Teller Amendment was an amendment to a joint resolution of the United States Congress, enacted on April 20, 1898, in reply to President William McKinley's War Message. It placed a condition on the United States military's presence in Cuba. Ac ...

to the U.S. declaration of war against Spain in 1898 disavowed any intention of exercising "sovereignty, jurisdiction or control" over Cuba, but the United States only agreed to withdraw its troops from Cuba when Cuba agreed to the eight provisions of the Platt Amendment, an amendment to the 1901 Army Appropriations Act authored by Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

Republican Senator Orville H. Platt

Orville Hitchcock Platt (July 19, 1827 – April 21, 1905) was a United States senator from Connecticut. Platt was a prominent conservative Republican and by the 1890s he became one of the "big four" key Republicans who largely controlled the ma ...

, which would allow the United States to intervene in Cuban affairs if needed for the maintenance of good government and committed Cuba to lease to the U.S. land for naval bases. Cuba leased to the United States the southern portion of Guantánamo Bay, where a United States Naval Station had been established in 1898. The Platt Amendment defined the terms of Cuban-U.S. relations for the following 33 years and provided the legal basis for U.S. military interventions with varying degrees of support from Cuban governments and political parties.

Despite recognizing Cuba's transition into an independent republic, United States Governor Charles Edward Magoon

Charles Edward Magoon (December 5, 1861 – January 14, 1920) was an American lawyer, judge, diplomat, and administrator who is best remembered as a governor of the Panama Canal Zone; he also served as Minister to Panama at the same time. Hi ...

assumed temporary military rule for three more years following a rebellion led in part by José Miguel Gómez

José Miguel Gómez y Arias (6 July 1858 – 13 June 1921) was a Cuban politician and revolutionary who was one of the leaders of the rebel forces in the Cuban War of Independence. He later served as President of Cuba from 1909 to 1913.

Early ...

. In the following 20 years the United States repeatedly intervened militarily in Cuban affairs: 1906–09, 1912

Events January

* January 1 – The Republic of China (1912–49), Republic of China is established.

* January 5 – The Prague Conference (6th All-Russian Conference of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party) opens.

* January 6 ...

and 1917–22. In 1912 U.S. forces were sent to quell protests by Afro-Cubans against discrimination. At first President Woodrow Wilson (1913-1921) and Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

were determined to stay out of Cuban affairs. The political turmoil continued. Cuba joined in the war against Germany, and prospered from American contracts. US Marines were stationed to protect the major sugar plantations in the Sugar Intervention

The Sugar Intervention refers to the events in Cuba between 1917 and 1922, when the United States Marine Corps was stationed on the island.

Background

When conservative Cuban president Mario García Menocal was re-elected in November 1916, libera ...

. However, in 1919 political chaos again threatened the Civil War and Secretary of State Robert Lansing

Robert Lansing (; October 17, 1864 – October 30, 1928) was an American lawyer and diplomat who served as Counselor to the State Department at the outbreak of World War I, and then as United States Secretary of State under President Woodrow Wils ...

sent General Enoch Crowder to stabilize the situation.

By 1926 U.S. companies owned 60% of the Cuban sugar industry and imported 95% of the total Cuban crop, and Washington was generally supportive of successive Cuban governments. President Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States from 1923 to 1929. Born in Vermont, Coolidge was a History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer ...

led the U.S. delegation to the Sixth International Conference of American States from January 15–17, 1928, in Havana, the only international trip Coolidge made during his presidency; it would be the last time a sitting American president visited Cuba until Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the U ...

did so on March 20, 2016. However, internal confrontations between the government of Gerardo Machado

Gerardo Machado y Morales (28 September 1869 – 29 March 1939) was a general of the Cuban War of Independence and President of Cuba from 1925 to 1933.

Machado entered the presidency with widespread popularity and support from the major polit ...

and political opposition led to his military overthrow by Cuban rebels in 1933. U.S. Ambassador

Ambassadors of the United States are persons nominated by the President of the United States, president to serve as the country's diplomat, diplomatic representatives to foreign nations, international organizations, and as Ambassador-at-large, ...

Sumner Welles

Benjamin Sumner Welles (October 14, 1892September 24, 1961) was an American government official and diplomat in the Foreign Service. He was a major foreign policy adviser to President Franklin D. Roosevelt and served as Under Secretary of State ...

requested U.S. military intervention

The United States has formal diplomatic relations with most nations. This includes all UN member and observer states other than Bhutan, Iran, North Korea and Syria, and the UN observer State of Palestine, the last of which the U.S. does not rec ...

. President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, despite his promotion of the Good Neighbor policy toward Latin America, ordered 29 warship

A warship or combatant ship is a naval ship that is built and primarily intended for naval warfare. Usually they belong to the armed forces of a state. As well as being armed, warships are designed to withstand damage and are usually faster a ...

s to Cuba and Key West

Key West ( es, Cayo Hueso) is an island in the Straits of Florida, within the U.S. state of Florida. Together with all or parts of the separate islands of Dredgers Key, Fleming Key, Sunset Key, and the northern part of Stock Island, it cons ...

, alerting United States Marines, and bombers for use if necessary. Machado's replacement, Ramón Grau

Ramón Grau San Martín (13 September 1881 in La Palma, Pinar del Río Province, Spanish Cuba – 28 July 1969 in Havana, Cuba) was a Cuban physician who served as President of Cuba from 1933 to 1934 and from 1944 to 1948. He was the last pres ...

assumed the Presidency

A presidency is an administration or the executive, the collective administrative and governmental entity that exists around an office of president of a state or nation. Although often the executive branch of government, and often personified by a ...

and immediately nullified the Platt amendment. In protest, the United States denied recognition to Grau's government, Ambassador Welles describing the new regime as "communistic" and "irresponsible".

The rise of General Fulgencio Batista in the 1930s to de facto leader and President of Cuba for two terms (1940–44 and 1952–59) led to an era of close co-operation between the governments of Cuba and the United States. The United States and Cuba signed another Treaty of Relations in 1934. Batista's second term as president was initiated by a military coup planned in Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

, and U.S. President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

quickly recognized Batista's return to rule providing military and economic aid. The Batista era witnessed the almost complete domination of Cuba's economy by the United States, as the number of American corporations continued to swell, though corruption was rife and Havana also became a popular sanctuary for American organized crime

Organized crime (or organised crime) is a category of transnational, national, or local groupings of highly centralized enterprises run by criminals to engage in illegal activity, most commonly for profit. While organized crime is generally th ...

figures, notably hosting the infamous Havana Conference

The Havana Conference of 1946 was a historic meeting of United States Mafia and Cosa Nostra leaders in Havana, Cuba. Supposedly arranged by Charles "Lucky" Luciano, the conference was held to discuss important mob policies, rules, and business i ...

in 1946. U.S. Ambassador to Cuba

The United States ambassador to the Republic of Cuba is the official representative of the president of the United States to the head of state of Cuba, and serves as the head of the Embassy of the United States in Havana. Direct bilateral diploma ...

Arthur Gardner later described the relationship between the U.S. and Batista during his second term as President:

In July 1953, an armed conflict broke out in Cuba between rebels led by Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 200 ...

and the Batista government. During the course of the conflict, the U.S. sold 8.238 million dollars worth of weapons to the Cuban government to help quash the rebellion. However, the U.S. was urged to end arms sales to Batista by Cuban president-in-waiting Manuel Urrutia Lleó. Washington made the critical move in March 1958 to end sales of rifles to Batista's forces, thus changing the course of the Cuban Revolution irreversibly towards the rebels. The move was vehemently opposed by U.S. ambassador Earl E. T. Smith, and led U.S. State Department adviser William Wieland to lament that "I know Batista is considered by many as a son of a bitch ... but American interests come first ... at least he was our son of a bitch."

Post-revolution relations

U.S. PresidentDwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

officially recognized the new Cuban government after the 1959 Cuban Revolution which had overthrown the Batista government, but relations between the two governments deteriorated rapidly. Within days Earl E. T. Smith, U.S. Ambassador to Cuba, was replaced by Philip Bonsal. The U.S. government became increasingly concerned by Cuba's agrarian reforms Agrarian reform can refer either, narrowly, to government-initiated or government-backed redistribution of agricultural land (see land reform) or, broadly, to an overall redirection of the agrarian system of the country, which often includes land re ...

and the nationalization

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to pri ...

of industries owned by U.S. citizens. Between 15 and 26 April 1959, Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 200 ...

and a delegation of representatives visited the U.S. as guests of the Press Club. This visit was perceived by many as a charm offensive

Charm offensive may refer to:

* ''Charm. Offensive.'', a 2017 album by Die!_Die!_Die!

* '' Charm Offensive'', a 2018 album by Damien Done

* ''Armando Iannucci's Charm Offensive

''Armando Iannucci's Charm Offensive'' is a British radio comedy p ...

on the part of Castro and his recently initiated government, and his visit included laying a wreath at the Lincoln memorial. After a meeting between Castro and Vice President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

, where Castro outlined his reform plans for Cuba, the U.S. began to impose gradual trade restrictions on the island. On 4 September 1959, Ambassador Bonsal met with Cuban Premier Fidel Castro to express "serious concern at the treatment being given to American private interests in Cuba both agriculture and utilities."

The Escambray rebellion was a six-year rebellion (1959–1965) in the Escambray Mountains

The Escambray Mountains () are a mountain range in the central region of Cuba, in the provinces of Sancti Spíritus, Cienfuegos and Villa Clara.

Overview

The Escambray Mountains are located in the south-central region of the island, extending a ...

by a group of insurgents who opposed the Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

n government led by Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 200 ...

. The rebelling group of insurgents was a mix of former Batista

Batista is a Spanish language, Spanish or Portuguese language, Portuguese surname. Notable persons with the name include:

* Batista (footballer, born 1955), Brazilian football player

* Dave Bautista, American actor and professional wrestler, also ...

soldiers, local farmers, and former allied guerrillas who had fought alongside Castro against Batista during the Cuban Revolution.

As state intervention and take-over of privately owned businesses continued, trade restrictions on Cuba increased. The U.S. stopped buying Cuban sugar and refused to supply its former trading partner with much needed oil, with a devastating effect on the island's economy, leading to Cuba turning to their newfound trading partner, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, for petroleum. In March 1960, tensions increased when the French freighter ''La Coubre

The French freighter ''La Coubre'' () exploded in the harbour of Havana, Cuba, on 4 March 1960 while it was unloading 76 tons of grenades and munitions. Seventy-five to 100 people were killed, and many were injured. Fidel Castro alleged it wa ...

'' exploded in Havana Harbor, killing over 75 people. Fidel Castro blamed the United States and compared the incident to the sinking of the ''Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north ...

'', though admitting he could provide no evidence for his accusation. That same month, President Eisenhower quietly authorized the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

(CIA) to organize, train, and equip Cuban refugees as a guerrilla force to overthrow Castro.

Each time the Cuban government nationalized property belonging to American citizens, the American government took countermeasures, resulting in the prohibition of all exports to Cuba on 19 October 1960. Consequently, Cuba began to consolidate trade relations with the USSR, leading the U.S. to break off all remaining official diplomatic relations. Later that year, U.S. diplomats Edwin L. Sweet and William G. Friedman were arrested and expelled from the island having been charged with "encouraging terrorist acts, granting asylum, financing subversive publications and smuggling weapons". On 3 January 1961 the U.S. withdrew diplomatic recognition of the Cuban government and closed the embassy in Havana.

Presidential candidate

A candidate, or nominee, is the prospective recipient of an award or honor, or a person seeking or being considered for some kind of position; for example:

* to be elected to an office — in this case a candidate selection procedure occurs.

* t ...

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination i ...

believed that Eisenhower's policy toward Cuba had been mistaken. He criticized what he saw as use of U.S. government influence to advance the interest and increase the profits of private U.S. companies instead of helping Cuba to achieve economic progress, saying that Americans dominated the island's economy and had given support to one of the bloodiest and most repressive dictatorships in the history of Latin America. "We let Batista put the U.S. on the side of tyranny, and we did nothing to convince the people of Cuba and Latin America that we wanted to be on the side of freedom".

In April 1961, an armed invasion by about 1,500 CIA trained Cuban exiles at the

In April 1961, an armed invasion by about 1,500 CIA trained Cuban exiles at the Bay of Pigs

The Bay of Pigs ( es, Bahía de los Cochinos) is an inlet of the Gulf of Cazones located on the southern coast of Cuba. By 1910, it was included in Santa Clara Province, and then instead to Las Villas Province by 1961, but in 1976, it was reas ...

was defeated by the Cuban armed forces. President Kennedy's complete assumption of responsibility for the venture, which provoked a popular reaction against the invasion, proved to be a further propaganda boost for the Cuban government. The U.S. began the formulation of new plans aimed at destabilizing the Cuban government. The U.S. government engaged in an extensive series of terrorist attacks

The following is a list of terrorist incidents that have not been carried out by a state or its forces (see state terrorism and state-sponsored terrorism). Assassinations are listed at List of assassinated people.

Definitions of terrori ...

in Cuba. These activities were collectively known as the "Cuban Project

The Cuban Project, also known as Operation Mongoose, was an extensive campaign of terrorist attacks against civilians and covert operations carried out by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency in Cuba. It was officially authorized on November 3 ...

" or ''Operation Mongoose

The Cuban Project, also known as Operation Mongoose, was an extensive campaign of terrorist attacks against civilians and covert operations carried out by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency in Cuba. It was officially authorized on November ...

''. The attacks formed a CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

-coordinated program of terrorist bombings, political and military sabotage, and psychological operations, as well as assassination attempts on key political leaders. The Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, that advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and the ...

also proposed attacks on mainland U.S. targets, hijackings and assaults on Cuban refugee boats to generate U.S. public support for military action against the Cuban government, these proposals were known collectively as Operation Northwoods

Operation Northwoods was a proposed false flag operation against American citizens that originated within the US Department of Defense of the United States government in 1962. The proposals called for CIA operatives to both stage and actually co ...

.

A U.S. Senate Select Intelligence Committee report later confirmed over eight attempted plots to kill Castro between 1960 and 1965, as well as additional plans against other Cuban leaders. After weathering the failed Bay of Pigs invasion, Cuba observed as U.S. armed forces staged a mock invasion of a

A U.S. Senate Select Intelligence Committee report later confirmed over eight attempted plots to kill Castro between 1960 and 1965, as well as additional plans against other Cuban leaders. After weathering the failed Bay of Pigs invasion, Cuba observed as U.S. armed forces staged a mock invasion of a Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

island in 1962 named Operation Ortsac

Operation Ortsac was the code name for a possible invasion of Cuba planned by the United States military in 1962. The name was derived from then Cuban President Fidel Castro by spelling his surname backwards.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, upon ...

. The purpose of the invasion was to overthrow a leader whose name, Ortsac, was Castro spelled backwards. Tensions between the two nations reached their peak in 1962, after U.S. reconnaissance aircraft photographed the Soviet construction of intermediate-range missile sites. The discovery led to the Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

.

Trade relations also deteriorated in equal measure. In 1962, President Kennedy broadened the partial trade restrictions imposed after the revolution by Eisenhower to a ban on all trade with Cuba, except for non-subsidized sale of foods and medicines. A year later travel and financial transactions by U.S. citizens with Cuba was prohibited. The United States embargo against Cuba

The United States embargo against Cuba prevents American businesses, and businesses organized under U.S. law or majority-owned by American citizens, from conducting trade with Cuban interests. It is the most enduring trade embargo in modern hist ...

was to continue in varying forms. Despite tensions between the United States and Cuba during the Kennedy years, relations began to thaw somewhat after the Cuban Missile Crisis. Back channels that had already been established at the height of tensions between the two nations began to expand in 1963. Though Attorney General Robert Kennedy worried that such contact would hurt his brother's chances of re-election, President John Kennedy continued these contacts resulting in several meetings U.S. ambassador William Atwood and Cuban officials such as Carlos Lechuga. Other contacts would be established directly between President Kennedy and Fidel Castro through media figures such as Lisa Howard and French reporter Jean Daniel days before the Kennedy Assassination with Castro stating "I am willing to declare Goldwater my friend if that will guarantee Kennedy's re-election".

Castro would continue efforts to improve relations with the incoming Johnson administration sending a message to Johnson encouraging dialogue saying:

Continued tensions over various issues would hamper further efforts to normalization relations that started at the end of the Kennedy administration such as the Guantanamo dispute of 1964, or Cuba's embrace of American political dissidents such as Black Panther leaders who took refuge in Cuba during the 1960s. Perhaps the biggest clash during the Johnson administration would be the capture of Che Guevara in 1967 by Bolivia forces assisted by the CIA and U.S. Special forces.

Through the late 1960s and early 1970s a sustained period of aircraft hijackings between Cuba and the U.S. by citizens of both nations led to a need for cooperation. By 1974, U.S. elected officials had begun to visit the island. Three years later, during the Carter

Carter(s), or Carter's, Tha Carter, or The Carter(s), may refer to:

Geography United States

* Carter, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Carter, Mississippi, an unincorporated community

* Carter, Montana, a census-designated place

* Carter, ...

administration, the U.S. and Cuba simultaneously opened interests sections in each other's capitals.

In 1977, Cuba and the United States signed a maritime boundary treaty, agreeing on the location of their

In 1977, Cuba and the United States signed a maritime boundary treaty, agreeing on the location of their border

Borders are usually defined as geographical boundaries, imposed either by features such as oceans and terrain, or by political entities such as governments, sovereign states, federated states, and other subnational entities. Political borders c ...

in the Straits of Florida. The treaty was never sent to the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

for ratification

Ratification is a principal's approval of an act of its agent that lacked the authority to bind the principal legally. Ratification defines the international act in which a state indicates its consent to be bound to a treaty if the parties inten ...

, but the agreement has been implemented by the U.S. State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other nati ...

. In 1980, after 10,000 Cubans crammed into the Peruvian embassy seeking political asylum, Castro stated that any who wished to do so could leave Cuba, in what became known as the Mariel boatlift. Approximately 125,000 people left Cuba for the United States.

Beginning in the 1970s a growing and coordinated effort by US-based Cuban dissident

The Cuban dissident movement is a political movement in Cuba whose aim is to replace the current government with a liberal democracy. According to Human Rights Watch, the Cuban government represses nearly all forms of political dissent.

Backgrou ...

groups organized to confront the Castro regime through international bodies such as the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

. The United Nations Human Rights Council in particular would become a major front in these confrontations as issues of human rights became more widely known, especially in the 1980s as the United States itself became more directly involved during the Reagan administration, which had a tougher anti-Castro stance. In 1981 the Reagan administration announced a tightening of the embargo. The U.S. also re-established the travel ban, prohibiting U.S. citizens from spending money in Cuba. The ban was later supplemented to include Cuban government officials or their representatives visiting the U.S.

A significant turning point in the international United Nations efforts came in 1984 when the Miami-based Center for Human Rights led by Jesus Permuy

Jesús A. Permuy (born 1935) is a Cuban-American architect, urban planner, human rights activist, art collector, and businessman. He is known for an extensive career of community projects and initiatives in Florida, Washington, D.C., and Latin A ...

successfully lobbied to have Cuba's diplomatic representative, Luis Sola Vila, removed from a key subcommittee of the UN Human Rights Council and replaced with a representative from Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, a Christian-Democratic ally in opposition of the Castro government. The following year Radio y Televisión Martí

Radio Televisión Martí is an American state-run radio and television international broadcaster based in Miami, Florida, financed by the federal government of the United States through the U.S. Agency for Global Media (formerly Broadcasting Boar ...

, backed by the Reagan administration, began to broadcast news and information from the U.S. to Cuba. In 1987 when US President Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

appointed Armando Valladares

Armando Valladares Perez (born May 30, 1937) is a Cuban-American poet, diplomat and former political prisoner for his involvement in the Cuban dissident movement.

In 1960, he was arrested by the Cuban government for conflicting reasons; the Cub ...

, former Cuban political prisoner of 22 years, as the US ambassador to the United Nations Human Rights Committee

The United Nations Human Rights Committee is a treaty body composed of 18 experts, established by a 1966 human rights treaty, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). The Committee meets for three four-week sessions per y ...

.

Since 1990, the United States has presented various resolutions to the annual UN Human Rights Commission

The United Nations Commission on Human Rights (UNCHR) was a functional commission within the overall framework of the United Nations from 1946 until it was replaced by the United Nations Human Rights Council in 2006. It was a subsidiary body of t ...

criticizing Cuba's human rights record. The proposals and subsequent diplomatic disagreements have been described as a "nearly annual ritual".U.N. panel condemns Cuba for rights abusesMiami Herald April 19, 2001 Long-term consensus between Latin American nations has not emerged.Cuba, the U.N. Human Rights Commission and the OAS Race

Council on Hemispheric Affairs By the

end of the Cold War

End, END, Ending, or variation, may refer to:

End

*In mathematics:

**End (category theory)

**End (topology)

**End (graph theory)

** End (group theory) (a subcase of the previous)

**End (endomorphism)

*In sports and games

**End (gridiron football) ...

in 1992, there had been a substantial change in Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

as the United Nations Human Rights Committee representatives had shifted from initial rejection, then indifference and towards embrace of the anti-Castro Cuban human rights

Human rights are Morality, moral principles or Social norm, normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for ce ...

movement's diplomatic efforts.

After the Cold War

TheCold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

ended with the dissolution of the Soviet Union

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, also negatively connoted as rus, Разва́л Сове́тского Сою́за, r=Razvál Sovétskogo Soyúza, ''Ruining of the Soviet Union''. was the process of internal disintegration within the Sov ...

in the early 1990s, leaving Cuba without its major international sponsor. The ensuing years were marked by economic difficulty in Cuba, a time known as the Special Period. U.S. law allowed private humanitarian aid to Cuba for part of this time. However, the long-standing U.S. embargo was reinforced in October 1992 by the Cuban Democracy Act

The Cuban Democracy Act (CDA), also known as the Torricelli Act or the Torricelli-Graham Bill, was a bill introduced and sponsored by U.S. Congressman Robert Torricelli and aimed to tighten the U.S. embargo on Cuba. It reimplemented the ban of U.S. ...

(the "Torricelli Law") and in 1996 by the Cuban Liberty and Democracy Solidarity Act (known as the Helms-Burton Act). The 1992 act prohibited foreign-based subsidiaries of U.S. companies from trading with Cuba, travel to Cuba by U.S. citizens, and family remittances to Cuba. Sanctions could also be applied to non-U.S. companies trading with Cuba. As a result, multinational companies had to choose between Cuba and the U.S., the latter being a much larger market.

On 24 February 1996, two unarmed Cessna 337s flown by the group " Brothers to the Rescue" were shot down by Cuban Air Force MiG-29, killing three Cuban-Americans and one Cuban U.S. resident. The Cuban government claimed that the planes had entered into Cuban airspace.

Some veterans of CIA's 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion, while no longer being sponsored by the CIA, are still active, though they are now in their seventies or older. Members of Alpha 66

Alpha 66 is an anti-Castro paramilitary organization. The group was originally formed by Cuban exiles in the early 1960s and was most active in the late 1970s and 1980s. Its activities declined in the 1980s. Historian Alan McPherson describes it a ...

, an anti-Castro paramilitary organization, continue to practice their AK-47 skills in a camp in South Florida.

In January 1999, U.S. President Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

eased travel restrictions to Cuba in an effort to increase cultural exchanges between the two nations. The Clinton administration

Bill Clinton's tenure as the 42nd president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1993, and ended on January 20, 2001. Clinton, a Democrat from Arkansas, took office following a decisive election victory over Re ...

approved a two-game exhibition series between the Baltimore Orioles

The Baltimore Orioles are an American professional baseball team based in Baltimore. The Orioles compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) American League East, East division. As one of the American L ...

and the Cuba national baseball team

The Cuba national baseball team (Spanish: ''Selección de béisbol de Cuba'') represents Cuba at regional and international levels. The team is made up from the most professional players from the Cuban national baseball system. Cuba has been des ...

, marking the end of the hiatus since 1959 that a Major League Baseball

Major League Baseball (MLB) is a professional baseball organization and the oldest major professional sports league in the world. MLB is composed of 30 total teams, divided equally between the National League (NL) and the American League (AL), ...

team played in Cuba.

At the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

Millennium Summit in September 2000, Castro and Clinton spoke briefly at a group photo session and shook hands. U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan commented afterwards, "For a U.S. president and a Cuban president to shake hands for the first time in over 40 years—I think it is a major symbolic achievement". While Castro said it was a gesture of "dignity and courtesy", the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

denied the encounter was of any significance. In November 2001, U.S. companies began selling food to the country for the first time since Washington imposed the trade embargo after the revolution. In 2002, former U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he previously served as th ...

became the first former or sitting U.S. president to visit Cuba since 1928.

Tightening embargo

Relations deteriorated again following the election ofGeorge W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Republican Party, Bush family, and son of the 41st president George H. W. Bush, he ...

. During his campaign Bush appealed for the support of Cuban-Americans by emphasizing his opposition to the government of Fidel Castro and supporting tighter embargo restrictions.Perez, Louis A. Cuba: Between Reform And Revolution, New York, NY. 2006, p326 Cuban American

Cuban Americans ( es, cubanoestadounidenses or ''cubanoamericanos'') are Americans who trace their cultural heritage to Cuba regardless of phenotype or ethnic origin. The word may refer to someone born in the United States of Cuban descent or t ...

s, who until 2008 tended to vote Republican, expected effective policies and greater participation in the formation of policies regarding Cuba-U.S. relations. Approximately three months after his inauguration, the Bush administration began expanding travel restrictions. The United States Department of the Treasury

The Department of the Treasury (USDT) is the national treasury and finance department of the federal government of the United States, where it serves as an executive department. The department oversees the Bureau of Engraving and Printing and t ...

issued greater efforts to deter American citizens from illegally traveling to the island. Also in 2001, five Cuban agents were convicted on 26 counts of espionage, conspiracy to commit murder, and other illegal activities in the United States. On 15 June 2009, the U.S. Supreme Court denied review of their case. Tensions heightened as the Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security Affairs, John R. Bolton, accused Cuba of maintaining a biological weapons program. Many in the United States, including ex-president Carter, expressed doubts about the claim. Later, Bolton was criticized for pressuring subordinates who questioned the quality of the intelligence John Bolton had used as the basis for his assertion. Bolton identified the Castro government as part of America's "axis of evil," highlighting the fact that the Cuban leader visited several U.S. foes, including Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya bo ...

, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

and Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

.

Following his 2004 reelection, Bush

Bush commonly refers to:

* Shrub, a small or medium woody plant

Bush, Bushes, or the bush may also refer to:

People

* Bush (surname), including any of several people with that name

**Bush family, a prominent American family that includes:

*** ...

declared Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

to be one of the few "outposts of tyranny

"Outposts of tyranny" was a term used in 2005 by United States Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and subsequently by others in the U.S. government to characterize the governments of certain countries as being totalitarian regimes or dictatorship ...

" remaining in the world.

In January 2006,

In January 2006, United States Interests Section in Havana

The United States Interests Section of the Embassy of Switzerland in Havana, Cuba or USINT Havana (the State Department telegraphic address) represented United States interests in Cuba from September 1, 1977, to July 20, 2015. It was staffed by ...

began, in an attempt to break Cuba's "information blockade", displaying messages, including quotes from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is an international document adopted by the United Nations General Assembly that enshrines the Human rights, rights and freedoms of all human beings. Drafted by a UN Drafting of the Universal De ...

, on a scrolling "electronic billboard" in the windows of their top floor. Following a protest march organized by the Cuban government, the government erected a large number of poles, carrying black flags with single white stars, obscuring the messages.

On 10 October 2006, the United States announced the creation of a task force made up of officials from several U.S. agencies to pursue more aggressively American violators of the U.S. trade embargo against Cuba, with penalties as severe as 10 years of prison and hundreds of thousands of dollars in fines for violators of the embargo.

In November 2006, U.S. Congressional auditors accused the development agency USAID

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is an independent agency of the U.S. federal government that is primarily responsible for administering civilian foreign aid and development assistance. With a budget of over $27 bi ...

of failing properly to administer its program for promoting democracy in Cuba. They said USAID had channeled tens of millions of dollars through exile groups in Miami, which were sometimes wasteful or kept questionable accounts. The report said the organizations had sent items such as chocolate and cashmere jerseys to Cuba. Their report concluded that 30% of the exile groups who received USAID grants showed questionable expenditures.

After Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 200 ...

's announcement of resignation in 2008, U.S. Deputy Secretary of State John Negroponte

John Dimitri Negroponte (; born July 21, 1939) is an American diplomat. He is currently a James R. Schlesinger Distinguished Professor at the Miller Center for Public Affairs at the University of Virginia. He is a former J.B. and Maurice C. Sha ...

said that the United States would maintain its embargo.

Vision for "democratic transition"

In 2003, the United States

In 2003, the United States Commission for Assistance to a Free Cuba

The United States Commission for Assistance to a Free Cuba (CAFC) was created by United States President George W. Bush on October 10, 2003, to, according to him, explore ways the U.S. can help hasten and ease a democratic transition in Cuba.

Memb ...