Copernican model on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Copernican heliocentrism is the astronomical

Copernican heliocentrism is the astronomical

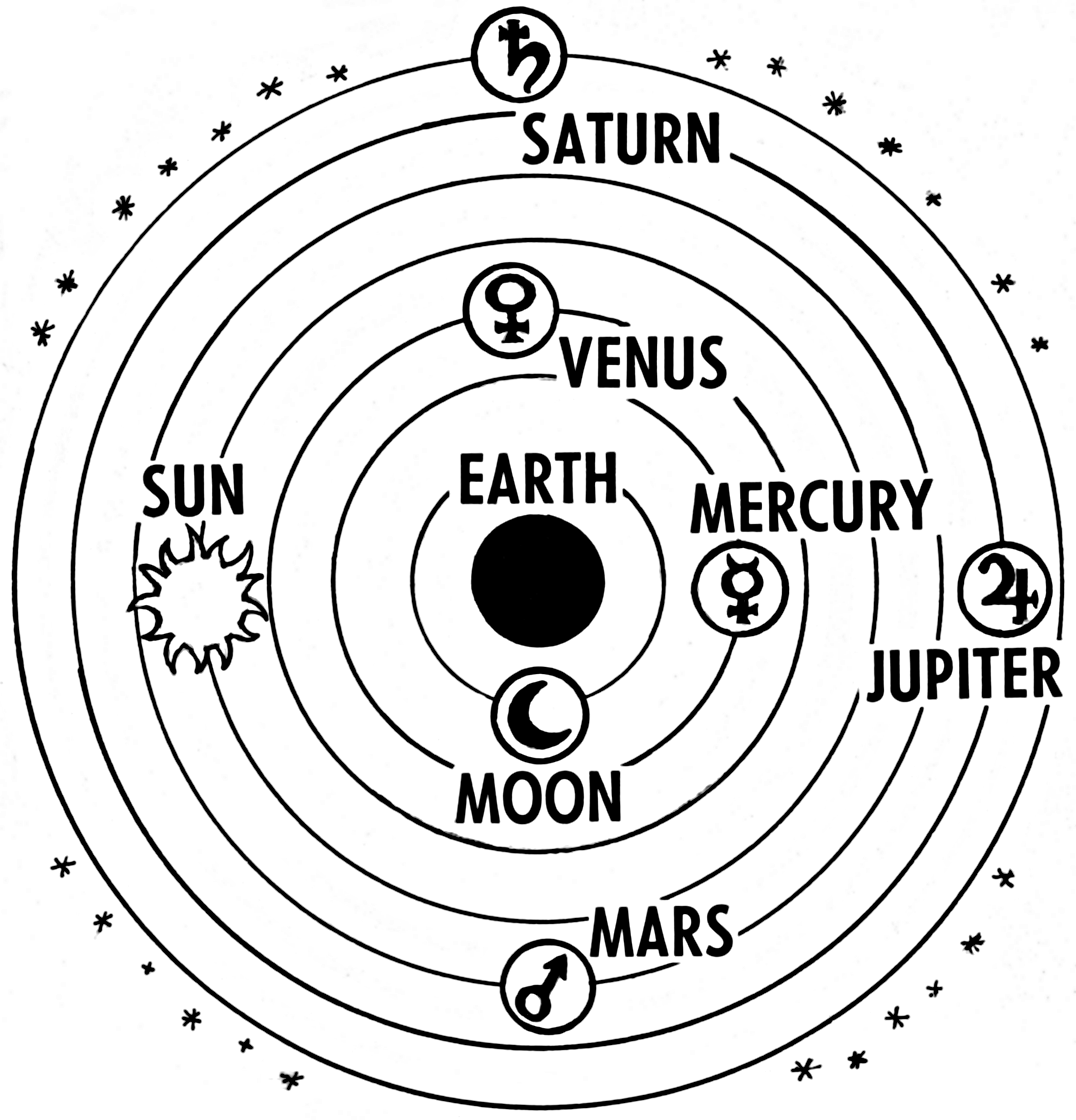

The prevailing astronomical model of the cosmos in Europe in the 1,400 years leading up to the 16th century was the Ptolemaic System, a geocentric model created by the Roman citizen

The prevailing astronomical model of the cosmos in Europe in the 1,400 years leading up to the 16th century was the Ptolemaic System, a geocentric model created by the Roman citizen

Copernicus used what is now known as the

Copernicus used what is now known as the

124137–38)

Saliba (2009, pp.160–65). However, no likely candidate for this conjectured work has come to light, and other scholars have argued that Copernicus could well have developed these ideas independently of the late Islamic tradition.Goddu (2010, pp.261–69, 476–86), Huff (2010

pp.263–64)

di Bono (1995), Veselovsky (1973). Nevertheless, Copernicus cited some of the Islamic astronomers whose theories and observations he used in ''De Revolutionibus'', namely

From publication until about 1700, few astronomers were convinced by the Copernican system, though the work was relatively widely circulated (around 500 copies of the first and second editions have survived, Gingerich (2004), p.248 which is a large number by the scientific standards of the time). Few of Copernicus' contemporaries were ready to concede that the Earth actually moved. Even forty-five years after the publication of ''De Revolutionibus'', the astronomer Tycho Brahe went so far as to construct a cosmology precisely equivalent to that of Copernicus, but with the Earth held fixed in the center of the celestial sphere instead of the Sun. It was another generation before a community of practicing astronomers appeared who accepted heliocentric cosmology.

For his contemporaries, the ideas presented by Copernicus were not markedly easier to use than the geocentric theory and did not produce more accurate predictions of planetary positions. Copernicus was aware of this and could not present any observational "proof", relying instead on arguments about what would be a more complete and elegant system. The Copernican model appeared to be contrary to common sense and to contradict the Bible.

Tycho Brahe's arguments against Copernicus are illustrative of the physical, theological, and even astronomical grounds on which heliocentric cosmology was rejected. Tycho, arguably the most accomplished astronomer of his time, appreciated the elegance of the Copernican system, but objected to the idea of a moving Earth on the basis of physics, astronomy, and religion. The

From publication until about 1700, few astronomers were convinced by the Copernican system, though the work was relatively widely circulated (around 500 copies of the first and second editions have survived, Gingerich (2004), p.248 which is a large number by the scientific standards of the time). Few of Copernicus' contemporaries were ready to concede that the Earth actually moved. Even forty-five years after the publication of ''De Revolutionibus'', the astronomer Tycho Brahe went so far as to construct a cosmology precisely equivalent to that of Copernicus, but with the Earth held fixed in the center of the celestial sphere instead of the Sun. It was another generation before a community of practicing astronomers appeared who accepted heliocentric cosmology.

For his contemporaries, the ideas presented by Copernicus were not markedly easier to use than the geocentric theory and did not produce more accurate predictions of planetary positions. Copernicus was aware of this and could not present any observational "proof", relying instead on arguments about what would be a more complete and elegant system. The Copernican model appeared to be contrary to common sense and to contradict the Bible.

Tycho Brahe's arguments against Copernicus are illustrative of the physical, theological, and even astronomical grounds on which heliocentric cosmology was rejected. Tycho, arguably the most accomplished astronomer of his time, appreciated the elegance of the Copernican system, but objected to the idea of a moving Earth on the basis of physics, astronomy, and religion. The

Heliocentric Pantheon

{{DEFAULTSORT:Copernican Heliocentrism History of astronomy Nicolaus Copernicus Copernican Revolution

Copernican heliocentrism is the astronomical

Copernican heliocentrism is the astronomical model

A model is an informative representation of an object, person or system. The term originally denoted the plans of a building in late 16th-century English, and derived via French and Italian ultimately from Latin ''modulus'', a measure.

Models c ...

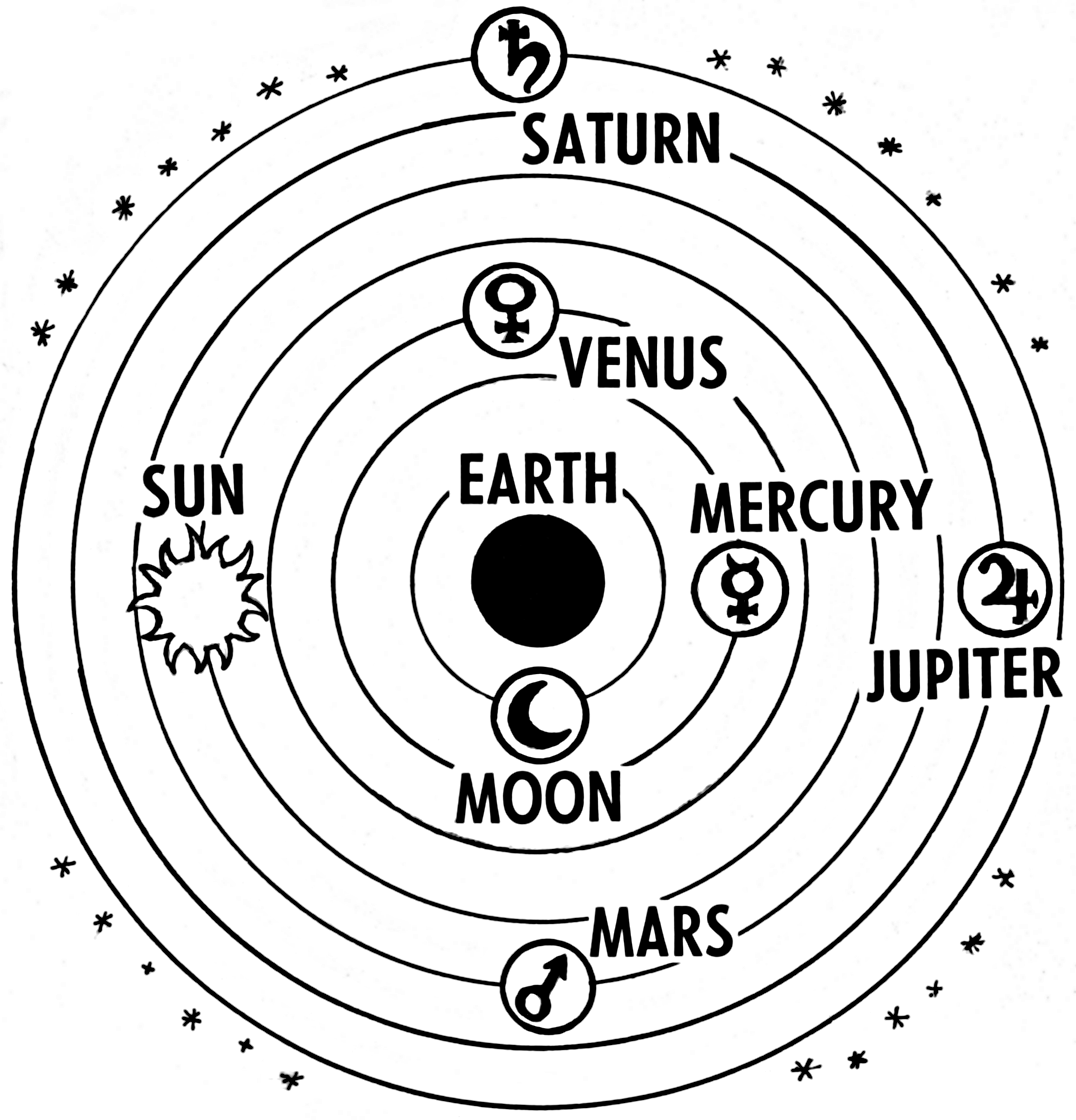

developed by Nicolaus Copernicus and published in 1543. This model positioned the Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

at the center of the Universe, motionless, with Earth and the other planets orbiting around it in circular paths, modified by epicycles, and at uniform speeds. The Copernican model displaced the geocentric model of Ptolemy that had prevailed for centuries, which had placed Earth at the center of the Universe.

Although he had circulated an outline of his own heliocentric theory to colleagues sometime before 1514, he did not decide to publish it until he was urged to do so later by his pupil Rheticus

Georg Joachim de Porris, also known as Rheticus ( /ˈrɛtɪkəs/; 16 February 1514 – 5 December 1576), was a mathematician, astronomer, cartographer, navigational-instrument maker, medical practitioner, and teacher. He is perhaps best known for ...

. Copernicus's challenge was to present a practical alternative to the Ptolemaic model by more elegantly and accurately determining the length of a solar year while preserving the metaphysical implications of a mathematically ordered cosmos. Thus, his heliocentric model retained several of the Ptolemaic elements, causing inaccuracies, such as the planets' circular orbit

A circular orbit is an orbit with a fixed distance around the barycenter; that is, in the shape of a circle.

Listed below is a circular orbit in astrodynamics or celestial mechanics under standard assumptions. Here the centripetal force is ...

s, epicycles, and uniform speeds, while at the same time using ideas such as:

* The Earth is one of several planets revolving around a stationary sun in a determined order.

* The Earth has three motions: daily rotation, annual revolution, and annual tilting of its axis.

* Retrograde motion of the planets is explained by the Earth's motion.

* The distance from the Earth to the Sun is small compared to the distance from the Sun to the stars.

Background

Antiquity

Philolaus (4th century BCE) was one of the first to hypothesize ''movement of the Earth'', probably inspired by Pythagoras' theories about a spherical, moving globe. In the 3rd century BCE,Aristarchus of Samos

Aristarchus of Samos (; grc-gre, Ἀρίσταρχος ὁ Σάμιος, ''Aristarkhos ho Samios''; ) was an ancient Greek astronomer and mathematician who presented the first known heliocentric model that placed the Sun at the center of the k ...

proposed what was, so far as is known, the first serious model of a heliocentric Solar System, having developed some of Heraclides Ponticus' theories (speaking of a "revolution of the Earth on its axis" every 24 hours). Though his original text has been lost, a reference in Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse (;; ) was a Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse in Sicily. Although few details of his life are known, he is regarded as one of the leading scientists i ...

' book '' The Sand Reckoner'' (''Archimedis Syracusani Arenarius & Dimensio Circuli'') describes a work in which Aristarchus advanced the heliocentric model. Archimedes wrote:

It is a common misconception that the heliocentric view was rejected by the contemporaries of Aristarchus. This is the result of Gilles Ménage's translation of a passage from Plutarch's

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his '' ...

''On the Apparent Face in the Orb of the Moon''. Plutarch reported that Cleanthes

Cleanthes (; grc-gre, Κλεάνθης; c. 330 BC – c. 230 BC), of Assos, was a Greek Stoic philosopher and boxer who was the successor to Zeno of Citium as the second head ('' scholarch'') of the Stoic school in Athens. Originally a boxer, ...

(a contemporary of Aristarchus and head of the Stoics) as a worshiper of the Sun and opponent to the heliocentric model, was jokingly told by Aristarchus that he should be charged with impiety. Ménage, shortly after the trials of Galileo and Giordano Bruno, amended an accusative (identifying the object of the verb) with a nominative (the subject of the sentence), and vice versa, so that the impiety accusation fell over the heliocentric sustainer. The resulting misconception of an isolated and persecuted Aristarchus is still transmitted today.

In 499 CE, the Indian astronomer and mathematician Aryabhata

Aryabhata (ISO: ) or Aryabhata I (476–550 CE) was an Indian mathematician and astronomer of the classical age of Indian mathematics and Indian astronomy. He flourished in the Gupta Era and produced works such as the '' Aryabhatiya'' (which ...

propounded a planetary model that explicitly incorporated Earth's rotation

Earth's rotation or Earth's spin is the rotation of planet Earth around its own axis, as well as changes in the orientation of the rotation axis in space. Earth rotates eastward, in prograde motion. As viewed from the northern polar star Polari ...

about its axis, which he explains as the cause of what appears to be an apparent westward motion of the stars. He also believed that the orbits of planets are elliptical. Aryabhata's followers were particularly strong in South India, where his principles of the diurnal rotation of Earth, among others, were followed and a number of secondary works were based on them.

Middle Ages

Islamic astronomers

Several Islamic astronomers questioned the Earth's apparent immobility and centrality within the universe. Some accepted that the Earth rotates around its axis, such asAbu Sa'id al-Sijzi

Abu Sa'id Ahmed ibn Mohammed ibn Abd al-Jalil al-Sijzi (c. 945 - c. 1020, also known as al-Sinjari and al-Sijazi; fa, ابوسعید سجزی; Al-Sijzi is short for "Al-Sijistani") was an Iranian Muslim astronomer, mathematician, and astrolog ...

, who invented an astrolabe

An astrolabe ( grc, ἀστρολάβος ; ar, ٱلأَسْطُرلاب ; persian, ستارهیاب ) is an ancient astronomical instrument that was a handheld model of the universe. Its various functions also make it an elaborate inclin ...

based on a belief held by some of his contemporaries "that the motion we see is due to the Earth's movement and not to that of the sky". That others besides al-Sijzi held this view is further confirmed by a reference from an Arabic work in the 13th century which states: "According to the geometers r engineers

R, or r, is the eighteenth letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''ar'' (pronounced ), plural ''ars'', or in Irelan ...

(''muhandisīn''), the earth is in constant circular motion, and what appears to be the motion of the heavens is actually due to the motion of the earth and not the stars".

In the 12th century, Nur ad-Din al-Bitruji proposed a complete alternative to the Ptolemaic system (although not heliocentric). He declared the Ptolemaic system as an imaginary model, successful at predicting planetary positions but not real or physical. Al-Btiruji's alternative system spread through most of Europe during the 13th century. Mathematical techniques developed in the 13th to 14th centuries by the Arab and Persian astronomers Mo'ayyeduddin al-Urdi

Al-Urdi (full name: Moayad Al-Din Al-Urdi Al-Amiri Al-Dimashqi) () (d. 1266) was a medieval Syrian Arab astronomer and geometer.

Born circa 1200, presumably (from the nisba ''al‐ʿUrḍī'') in the village of ''ʿUrḍ'' in the Syrian desert b ...

, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi

Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Tūsī ( fa, محمد ابن محمد ابن حسن طوسی 18 February 1201 – 26 June 1274), better known as Nasir al-Din al-Tusi ( fa, نصیر الدین طوسی, links=no; or simply Tusi in the West ...

, and Ibn al-Shatir

ʿAbu al-Ḥasan Alāʾ al‐Dīn ʿAlī ibn Ibrāhīm al-Ansari known as Ibn al-Shatir or Ibn ash-Shatir ( ar, ابن الشاطر; 1304–1375) was an Arab astronomer, mathematician and engineer. He worked as ''muwaqqit'' (موقت, religious t ...

for geocentric models of planetary motions closely resemble some of the techniques used later by Copernicus in his heliocentric models.

European astronomers

= Ptolemaic system

= The prevailing astronomical model of the cosmos in Europe in the 1,400 years leading up to the 16th century was the Ptolemaic System, a geocentric model created by the Roman citizen

The prevailing astronomical model of the cosmos in Europe in the 1,400 years leading up to the 16th century was the Ptolemaic System, a geocentric model created by the Roman citizen Claudius Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

in his ''Almagest

The ''Almagest'' is a 2nd-century Greek-language mathematical and astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the stars and planetary paths, written by Claudius Ptolemy ( ). One of the most influential scientific texts in history, it canon ...

,'' dating from about 150 CE. Throughout the Middle Ages it was spoken of as the authoritative text on astronomy, although its author remained a little understood figure frequently mistaken as one of the Ptolemaic rulers of Egypt. The Ptolemaic system drew on many previous theories that viewed Earth as a stationary center of the universe. Stars were embedded in a large outer sphere which rotated relatively rapidly, while the planets dwelt in smaller spheres between—a separate one for each planet. To account for apparent anomalies in this view, such as the apparent retrograde motion

Apparent retrograde motion is the apparent motion of a planet in a direction opposite to that of other bodies within its system, as observed from a particular vantage point. Direct motion or prograde motion is motion in the same direction as ...

of the planets, a system of deferents and epicycles was used. The planet was said to revolve in a small circle (the epicycle) about a center, which itself revolved in a larger circle (the deferent) about a center on or near the Earth.

A complementary theory to Ptolemy's employed homocentric spheres: the spheres within which the planets rotated could themselves rotate somewhat. This theory predated Ptolemy (it was first devised by Eudoxus of Cnidus

Eudoxus of Cnidus (; grc, Εὔδοξος ὁ Κνίδιος, ''Eúdoxos ho Knídios''; ) was an ancient Greek astronomer, mathematician, scholar, and student of Archytas and Plato. All of his original works are lost, though some fragments are ...

; by the time of Copernicus it was associated with Averroes

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psychology ...

). Also popular with astronomers were variations such as eccentrics—by which the rotational axis was offset and not completely at the center. The planets were also made to have exhibit irregular motions that deviated from a uniform and circular path. The eccentrics of the planets motions were analyzed to have made reverse motions over periods of observations. This retrograde motion created the foundation for why these particular pathways became known as epicycles.

Ptolemy's unique contribution to this theory was the equant

Equant (or punctum aequans) is a mathematical concept developed by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD to account for the observed motion of the planets. The equant is used to explain the observed speed change in different stages of the plan ...

—a point about which the center of a planet's epicycle moved with uniform angular velocity, but which was offset from the center of its deferent. This violated one of the fundamental principles of Aristotelian cosmology—namely, that the motions of the planets should be explained in terms of uniform circular motion, and was considered a serious defect by many medieval astronomers. In Copernicus' day, the most up-to-date version of the Ptolemaic system was that of Peurbach

Georg von Peuerbach (also Purbach, Peurbach; la, Purbachius; born May 30, 1423 – April 8, 1461) was an Austrian astronomer, poet, mathematician and instrument maker, best known for his streamlined presentation of Ptolemaic astronomy in the ''Th ...

(1423–1461) and Regiomontanus (1436–1476).

= Post-Ptolemy

= Since the 13th century, European scholars were well aware of problems with Ptolemaic astronomy. The debate was precipitated by the reception by Averroes' criticism of Ptolemy, and it was again revived by the recovery of Ptolemy's text and its translation into Latin in the mid-15th century."Averroes' criticism of Ptolemaic astronomy precipitated this debate in Europe. ..The recovery of Ptolemy's texts and their translation from Greek into Latin in the middle of the fifteenth century stimulated further consideration of these issues." Osler (2010), p.42 Otto E. Neugebauer in 1957 argued that the debate in 15th-century Latin scholarship must also have been informed by the criticism of Ptolemy produced after Averroes, by theIlkhanid

The Ilkhanate, also spelled Il-khanate ( fa, ایل خانان, ''Ilxānān''), known to the Mongols as ''Hülegü Ulus'' (, ''Qulug-un Ulus''), was a khanate established from the southwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. The Ilkhanid realm, ...

-era (13th to 14th centuries) Persian school of astronomy associated with the Maragheh observatory

The Maragheh observatory (Persian: رصدخانه مراغه), also spelled Maragha, Maragah, Marageh, and Maraga, was an astronomical observatory established in the mid 13th century under the patronage of the Ilkhanid Hulagu and the directorship ...

(especially the works of al-Urdi, al-Tusi and al-Shatir).

The state of the question as received by Copernicus is summarized in the ''Theoricae novae planetarum'' by Georg von Peuerbach

Georg von Peuerbach (also Purbach, Peurbach; la, Purbachius; born May 30, 1423 – April 8, 1461) was an Austrian astronomer, poet, mathematician and instrument maker, best known for his streamlined presentation of Ptolemaic astronomy in the ''Th ...

, compiled from lecture notes by Peuerbach's student Regiomontanus in 1454, but not printed until 1472. Peuerbach attempts to give a new, mathematically more elegant presentation of Ptolemy's system, but he does not arrive at heliocentrism. Regiomontanus was the teacher of Domenico Maria Novara da Ferrara

Domenico Maria Novara (1454–1504) was an Italian scientist.

Life

Born in Ferrara, for 21 years he was professor of astronomy at the University of Bologna, and in 1500 he also lectured in mathematics at Rome. He was notable as a Platonist ast ...

, who was in turn the teacher of Copernicus. There is a possibility that Regiomontanus already arrived at a theory of heliocentrism before his death in 1476, as he paid particular attention to the heliocentric theory of Aristarchus in a late work and mentions the "motion of the Earth" in a letter.

Copernican theory

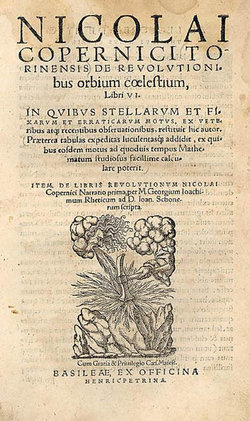

Copernicus' major work, ''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium'' (English translation: ''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres'') is the seminal work on the heliocentric theory of the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) of the Polish Renaissance. The book, ...

'' - ''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres'' (first edition 1543 in Nuremberg, second edition 1566 in Basel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS), ...

), was a compendium of six books published during the year of his death, though he had arrived at his theory several decades earlier. The work marks the beginning of the shift away from a geocentric (and anthropocentric

Anthropocentrism (; ) is the belief that human beings are the central or most important entity in the universe. The term can be used interchangeably with humanocentrism, and some refer to the concept as human supremacy or human exceptionalism. F ...

) universe with the Earth at its center. Copernicus held that the Earth is another planet revolving around the fixed Sun once a year and turning on its axis once a day. But while Copernicus put the Sun at the center of the celestial spheres, he did not put it at the exact center of the universe, but near it. Copernicus' system used only uniform circular motions, correcting what was seen by many as the chief inelegance in Ptolemy's system.

The Copernican model replaced Ptolemy's equant

Equant (or punctum aequans) is a mathematical concept developed by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD to account for the observed motion of the planets. The equant is used to explain the observed speed change in different stages of the plan ...

circles with more epicycles. 1,500 years of Ptolemy's model help create a more accurate estimate of the planets motions for Copernicus. This is the main reason that Copernicus' system had even more epicycles than Ptolemy's. The more epicycles proved to have more accurate measurements of how the planets were truly positioned, "although not enough to get excited about". The Copernican system can be summarized in several propositions, as Copernicus himself did in his early ''Commentariolus

The ''Commentariolus'' (''Little Commentary'') is Nicolaus Copernicus's brief outline of an early version of his revolutionary heliocentric theory of the universe. After further long development of his theory, Copernicus published the mature ver ...

'' that he handed only to friends, probably in the 1510s. The "little commentary" was never printed. Its existence was only known indirectly until a copy was discovered in Stockholm around 1880, and another in Vienna a few years later.

The major features of Copernican theory are:

# Heavenly motions are uniform, eternal, and circular or compounded of several circles (epicycles).

# The center of the universe is near the Sun.

# Around the Sun, in order, are Mercury, Venus, the Earth and Moon, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and the fixed stars.

# The Earth has three motions: daily rotation, annual revolution, and annual tilting of its axis.

# Retrograde motion of the planets is explained by the Earth's motion, which in short was also influenced by planets and other celestial bodies around Earth.

# The distance from the Earth to the Sun is small compared to the distance to the stars.

Inspiration came to Copernicus not from observation of the planets, but from reading two authors, Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

and Plutarch. In Cicero's writings, Copernicus found an account of the theory of Hicetas. Plutarch provided an account of the Pythagoreans Heraclides Ponticus

Heraclides Ponticus ( grc-gre, Ἡρακλείδης ὁ Ποντικός ''Herakleides''; c. 390 BC – c. 310 BC) was a Greek philosopher and astronomer who was born in Heraclea Pontica, now Karadeniz Ereğli, Turkey, and migrated to Athens. He ...

, Philolaus, and Ecphantes. These authors had proposed a moving Earth, which did ''not'' revolve around a central Sun. Copernicus cited Aristarchus and Philolaus in an early manuscript of his book which survives, stating: "Philolaus believed in the mobility of the earth, and some even say that Aristarchus of Samos was of that opinion". For unknown reasons (although possibly out of reluctance to quote pre-Christian sources), Copernicus did not include this passage in the publication of his book.

Copernicus used what is now known as the

Copernicus used what is now known as the Urdi lemma

Al-Urdi (full name: Moayad Al-Din Al-Urdi Al-Amiri Al-Dimashqi) () (d. 1266) was a medieval Syrian Arab astronomer and geometer.

Born circa 1200, presumably (from the nisba ''al‐ʿUrḍī'') in the village of ''ʿUrḍ'' in the Syrian desert b ...

and the Tusi couple in the same planetary models as found in Arabic sources. Furthermore, the exact replacement of the equant by two epicycles used by Copernicus in the ''Commentariolus'' was found in an earlier work by al-Shatir. Al-Shatir's lunar and Mercury models are also identical to those of Copernicus. This has led some scholars to argue that Copernicus must have had access to some yet to be identified work on the ideas of those earlier astronomers.Linton (2004, p124

Saliba (2009, pp.160–65).

pp.263–64)

di Bono (1995), Veselovsky (1973). Nevertheless, Copernicus cited some of the Islamic astronomers whose theories and observations he used in ''De Revolutionibus'', namely

al-Battani

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Jābir ibn Sinān al-Raqqī al-Ḥarrānī aṣ-Ṣābiʾ al-Battānī ( ar, محمد بن جابر بن سنان البتاني) ( Latinized as Albategnius, Albategni or Albatenius) (c. 858 – 929) was an astron ...

, Thabit ibn Qurra, al-Zarqali, Averroes

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psychology ...

, and al-Bitruji

Nur ad-Din al-Bitruji () (also spelled Nur al-Din Ibn Ishaq al-Betrugi and Abu Ishâk ibn al-Bitrogi) (known in the West by the Latinized name of Alpetragius) (died c. 1204) was an Iberian-Arab astronomer and a Qadi in al-Andalus. Al-Biṭrūjī ...

.

''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium''

When Copernicus' compendium was published, it contained an unauthorized, anonymous preface by a friend of Copernicus, the Lutheran theologianAndreas Osiander

Andreas Osiander (; 19 December 1498 – 17 October 1552) was a German Lutheran theologian and Protestant reformer.

Career

Born at Gunzenhausen, Ansbach, in the region of Franconia, Osiander studied at the University of Ingolstadt before b ...

. This cleric stated that Copernicus wrote his heliocentric account of the Earth's movement as a mathematical hypothesis, not as an account that contained truth or even probability. Since Copernicus' hypothesis was believed to contradict the Old Testament account of the Sun's movement around the Earth ( Joshua 10:12-13), this was apparently written to soften any religious backlash against the book. However, there is no evidence that Copernicus himself considered the heliocentric model as merely mathematically convenient, separate from reality.

Copernicus' actual compendium began with a letter from his (by then deceased) friend Nikolaus von Schönberg

Nikolaus von Schönberg (11 August 1472 – 7 September 1537) was a German Catholic cardinal and Archbishop of Capua.

Biography

Born in Rothschönberg near Meissen to a noble family which already had several Bishops of Meissen, Nikolaus became ...

, Cardinal Archbishop of Capua, urging Copernicus to publish his theory. Then, in a lengthy introduction, Copernicus dedicated the book to Pope Paul III, explaining his ostensible motive in writing the book as relating to the inability of earlier astronomers to agree on an adequate theory of the planets, and noting that if his system increased the accuracy of astronomical predictions it would allow the Church to develop a more accurate calendar. At that time, a reform of the Julian Calendar was considered necessary and was one of the major reasons for the Church's interest in astronomy.

The work itself is divided into six books:

# The first is a general vision of the heliocentric theory, and a summarized exposition of his idea of the World.

# The second is mainly theoretical, presenting the principles of spherical astronomy and a list of stars (as a basis for the arguments developed in the subsequent books).

# The third is mainly dedicated to the apparent motions of the Sun and to related phenomena.

# The fourth is a description of the Moon and its orbital motions.

# The fifth is a concrete exposition of the new system, including planetary longitude.

# The sixth is further concrete exposition of the new system, including planetary latitude.

Early criticisms

Aristotelian physics

Aristotelian physics is the form of natural science described in the works of the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BC). In his work ''Physics'', Aristotle intended to establish general principles of change that govern all natural bodies, ...

of the time (modern Newtonian physics was still a century away) offered no physical explanation for the motion of a massive body like Earth, but could easily explain the motion of heavenly bodies by postulating that they were made of a different sort of substance called aether that moved naturally. So Tycho said that the Copernican system “... expertly and completely circumvents all that is superfluous or discordant in the system of Ptolemy. On no point does it offend the principle of mathematics. Yet it ascribes to the Earth, that hulking, lazy body, unfit for motion, a motion as quick as that of the aethereal torches, and a triple motion at that.” Thus many astronomers accepted some aspects of Copernicus's theory at the expense of others.

Copernican Revolution

TheCopernican Revolution

The Copernican Revolution was the paradigm shift from the Ptolemaic model of the heavens, which described the cosmos as having Earth stationary at the center of the universe, to the heliocentric model with the Sun at the center of the Solar Syst ...

, a paradigm shift from the Ptolemaic model of the heavens, which described the cosmos as having Earth as a stationary body at the center of the universe, to the heliocentric model with the Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

at the center of the Solar System, spanned over a century, beginning with the publication of Copernus' ''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium'' (English translation: ''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres'') is the seminal work on the heliocentric theory of the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) of the Polish Renaissance. The book, ...

'' and ending with the work of Isaac Newton. While not warmly received by his contemporaries, his model did have a large influence on later scientists such as Galileo and Johannes Kepler, who adopted, championed and (especially in Kepler's case) sought to improve it. However, in the years following publication of ''de Revolutionibus'', for leading astronomers such as Erasmus Reinhold, the key attraction of Copernicus's ideas was that they reinstated the idea of uniform circular motion for the planets.

During the 17th century, several further discoveries eventually led to the wider acceptance of heliocentrism:

* Using detailed observations by Tycho Brahe, Kepler discovered Mars's orbit was an ellipse with the Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

at one focus and its speed varied with its distance to the Sun. This discovery was detailed in his 1609 book ''Astronomia nova

''Astronomia nova'' (English: ''New Astronomy'', full title in original Latin: ) is a book, published in 1609, that contains the results of the astronomer Johannes Kepler's ten-year-long investigation of the motion of Mars.

One of the most si ...

'' along with the claim all planets had elliptical orbits and non-uniform motion, stating "And finally... the sun itself... will melt all this Ptolemaic apparatus like butter".

* Using the newly invented telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, absorption, or reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally meaning only an optical instrument using lenses, curved mirrors, or a combination of both to observ ...

, in 1610 Galileo discovered the four large moons of Jupiter (evidence that the Solar System contained bodies that did not orbit Earth), the phases of Venus (more observational evidence not properly explained by the Ptolemaic theory) and the rotation of the Sun about a fixed axisFixed, that is, in the Copernican system. In a geostatic system the apparent annual variation in the motion of sunspots could only be explained as the result of an implausibly complicated precession of the Sun's axis of rotation (Linton, 2004, p.212; Sharratt, 1994, p.166; Drake, 1970, pp.191–196) as indicated by the apparent annual variation in the motion of sunspots;

* With a telescope, Giovanni Zupi

Giovanni Battista Zupi or ''Zupus'' (2 November 1589 – 26 August 1667) was an Italian astronomer, mathematician, and Jesuit priest.

He was born in Catanzaro. In 1639, Giovanni was the first person to discover that the planet Mercury had or ...

saw the phases of Mercury in 1639;

* Isaac Newton in 1687 proposed universal gravity and the inverse-square law of gravitational attraction to explain Kepler's elliptical planetary orbits.

Modern views

Substantially correct

From a modern point of view, the Copernican model has a number of advantages. Copernicus gave a clear account of the cause of the seasons: that the Earth's axis is not perpendicular to the plane of its orbit. In addition, Copernicus's theory provided a strikingly simple explanation for the apparent retrograde motions of the planets—namely as parallactic displacements resulting from the Earth's motion around the Sun—an important consideration in Johannes Kepler's conviction that the theory was substantially correct. In the heliocentric model the planets' apparent retrograde motions' occurring at opposition to the Sun are a natural consequence of their heliocentric orbits. In the geocentric model, however, these are explained by thead hoc

Ad hoc is a Latin phrase meaning literally 'to this'. In English, it typically signifies a solution for a specific purpose, problem, or task rather than a generalized solution adaptable to collateral instances. (Compare with ''a priori''.)

Com ...

use of epicycles, whose revolutions are mysteriously tied to that of the Sun's.

Modern historiography

Whether Copernicus' propositions were "revolutionary" or "conservative" has been a topic of debate in thehistoriography of science

The historiography of science or the historiography of the history of science is the study of the history and methodology of the sub-discipline of history, known as the history of science, including its disciplinary aspects and practices (methods ...

. In his book '' The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe'' (1959), Arthur Koestler

Arthur Koestler, (, ; ; hu, Kösztler Artúr; 5 September 1905 – 1 March 1983) was a Hungarian-born author and journalist. Koestler was born in Budapest and, apart from his early school years, was educated in Austria. In 1931, Koestler join ...

attempted to deconstruct the Copernican "revolution" by portraying Copernicus as a coward who was reluctant to publish his work due to a crippling fear of ridicule. Thomas Kuhn argued that Copernicus only transferred "some properties to the Sun's many astronomical functions previously attributed to the earth." Historians have since argued that Kuhn underestimated what was "revolutionary" about Copernicus' work, and emphasized the difficulty Copernicus would have had in putting forward a new astronomical theory relying alone on simplicity in geometry, given that he had no experimental evidence.

See also

*Copernican principle

In physical cosmology, the Copernican principle states that humans, on the Earth or in the Solar System, are not privileged observers of the universe, that observations from the Earth are representative of observations from the average position ...

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* Analyses the varieties of argument used by Copernicus in ''De revolutionibus''. *External links

Heliocentric Pantheon

{{DEFAULTSORT:Copernican Heliocentrism History of astronomy Nicolaus Copernicus Copernican Revolution