Cretaceous period on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Cretaceous ( ) is a

The lower boundary of the Cretaceous is currently undefined, and the Jurassic–Cretaceous boundary is currently the only system boundary to lack a defined

The lower boundary of the Cretaceous is currently undefined, and the Jurassic–Cretaceous boundary is currently the only system boundary to lack a defined

The high sea level and warm climate of the Cretaceous meant large areas of the continents were covered by warm, shallow seas, providing habitat for many marine organisms. The Cretaceous was named for the extensive chalk deposits of this age in Europe, but in many parts of the world, the deposits from the Cretaceous are of marine

The high sea level and warm climate of the Cretaceous meant large areas of the continents were covered by warm, shallow seas, providing habitat for many marine organisms. The Cretaceous was named for the extensive chalk deposits of this age in Europe, but in many parts of the world, the deposits from the Cretaceous are of marine

The production of large quantities of magma, variously attributed to mantle plumes or to extensional tectonics, further pushed sea levels up, so that large areas of the continental crust were covered with shallow seas. The Tethys Sea connecting the tropical oceans east to west also helped to warm the global climate. Warm-adapted plant fossils are known from localities as far north as Alaska and Greenland, while

The production of large quantities of magma, variously attributed to mantle plumes or to extensional tectonics, further pushed sea levels up, so that large areas of the continental crust were covered with shallow seas. The Tethys Sea connecting the tropical oceans east to west also helped to warm the global climate. Warm-adapted plant fossils are known from localities as far north as Alaska and Greenland, while

Flowering plants (angiosperms) make up around 90% of living plant species today. Prior to the rise of angiosperms, during the Jurassic and the Early Cretaceous, the higher flora was dominated by

Flowering plants (angiosperms) make up around 90% of living plant species today. Prior to the rise of angiosperms, during the Jurassic and the Early Cretaceous, the higher flora was dominated by

File:Tyrannosaurus-rex-Profile-steveoc86.png, ''

Rhynchocephalians (which today only includes the tuatara) disappeared from North America and Europe after the Early Cretaceous, and were absent from North Africa and northern South America by the early

Rhynchocephalians (which today only includes the tuatara) disappeared from North America and Europe after the Early Cretaceous, and were absent from North Africa and northern South America by the early

Choristodera, Choristoderes, a group of freshwater aquatic reptiles that first appeared during the preceding Jurassic, underwent a major evolutionary radiation in Asia during the Early Cretaceous, which represents the high point of choristoderan diversity, including long necked forms such as ''Hyphalosaurus'' and the first records of the gharial-like Neochoristodera, which appear to have evolved in the regional absence of aquatic neosuchian crocodyliformes. During the Late Cretaceous the neochoristodere ''Champsosaurus'' was widely distributed across western North America. Due to the extreme climatic warmth in the Arctic, choristoderans were able to colonise it too during the Late Cretaceous.

Choristodera, Choristoderes, a group of freshwater aquatic reptiles that first appeared during the preceding Jurassic, underwent a major evolutionary radiation in Asia during the Early Cretaceous, which represents the high point of choristoderan diversity, including long necked forms such as ''Hyphalosaurus'' and the first records of the gharial-like Neochoristodera, which appear to have evolved in the regional absence of aquatic neosuchian crocodyliformes. During the Late Cretaceous the neochoristodere ''Champsosaurus'' was widely distributed across western North America. Due to the extreme climatic warmth in the Arctic, choristoderans were able to colonise it too during the Late Cretaceous.

File:Kronosaurus hunt1DB.jpg, A scene from the early Cretaceous: a ''Woolungasaurus'' is attacked by a ''Kronosaurus''.

File:Tylosaurus pembinensis 1DB.jpg, ''Tylosaurus'' was a large

UCMP Berkeley Cretaceous pageCretaceous Microfossils: 180+ images of Foraminifera

* {{Authority control Cretaceous, Geological periods

geological period

The geologic time scale or geological time scale (GTS) is a representation of time based on the geologic record, rock record of Earth. It is a system of chronological dating that uses chronostratigraphy (the process of relating stratum, strata ...

that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 million years ago

Million years ago, abbreviated as Mya, Myr (megayear) or Ma (megaannum), is a unit of time equal to (i.e. years), or approximately 31.6 teraseconds.

Usage

Myr is in common use in fields such as Earth science and cosmology. Myr is also used w ...

(Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era is the Era (geology), era of Earth's Geologic time scale, geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous Period (geology), Periods. It is characterized by the dominance of archosaurian r ...

Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ninth and longest geological period of the entire Phanerozoic

The Phanerozoic is the current and the latest of the four eon (geology), geologic eons in the Earth's geologic time scale, covering the time period from 538.8 million years ago to the present. It is the eon during which abundant animal and ...

. The name is derived from the Latin , 'chalk

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock. It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed deep under the sea by the compression of microscopic plankton that had settled to the sea floor. Ch ...

', which is abundant in the latter half of the period. It is usually abbreviated K, for its German translation .

The Cretaceous was a period with a relatively warm climate

Climate is the long-term weather pattern in a region, typically averaged over 30 years. More rigorously, it is the mean and variability of meteorological variables over a time spanning from months to millions of years. Some of the meteoro ...

, resulting in high eustatic sea levels that created numerous shallow inland seas

An inland sea (also known as an epeiric sea or an epicontinental sea) is a continental body of water which is very large in area and is either completely surrounded by dry land (landlocked), or connected to an ocean by a river, strait or " arm of ...

. These oceans and seas were populated with now-extinct

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

marine reptile

Marine reptiles are reptiles which have become secondarily adapted for an aquatic or semiaquatic life in a marine environment. Only about 100 of the 12,000 extant reptile species and subspecies are classed as marine reptiles, including mari ...

s, ammonites

Ammonoids are extinct, (typically) coiled-shelled cephalopods comprising the subclass Ammonoidea. They are more closely related to living octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish (which comprise the clade Coleoidea) than they are to nautiluses (family N ...

, and rudists

Rudists are a group of extinct box-, tube- or ring-shaped Marine (ocean), marine Heterodonta, heterodont bivalves belonging to the order Hippuritida that arose during the Late Jurassic and became so diverse during the Cretaceous that they were m ...

, while dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

s continued to dominate on land. The world was largely ice-free, although there is some evidence of brief periods of glaciation during the cooler first half, and forests extended to the poles.

Many of the dominant taxonomic groups present in modern times can be ultimately traced back to origins in the Cretaceous. During this time, new groups of mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s and birds

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

appeared, including the earliest relatives of placentals and marsupial

Marsupials are a diverse group of mammals belonging to the infraclass Marsupialia. They are natively found in Australasia, Wallacea, and the Americas. One of marsupials' unique features is their reproductive strategy: the young are born in a r ...

s (Eutheria

Eutheria (from Greek , 'good, right' and , 'beast'; ), also called Pan-Placentalia, is the clade consisting of Placentalia, placental mammals and all therian mammals that are more closely related to placentals than to marsupials.

Eutherians ...

and Metatheria

Metatheria is a mammalian clade that includes all mammals more closely related to marsupials than to placentals. First proposed by Thomas Henry Huxley in 1880, it is a more inclusive group than the marsupials; it contains all marsupials as wel ...

respectively), with the earliest crown group

In phylogenetics, the crown group or crown assemblage is a collection of species composed of the living representatives of the collection, the most recent common ancestor of the collection, and all descendants of the most recent common ancestor ...

birds appearing towards to the end of the Cretaceous. Teleost

Teleostei (; Ancient Greek, Greek ''teleios'' "complete" + ''osteon'' "bone"), members of which are known as teleosts (), is, by far, the largest group of ray-finned fishes (class Actinopterygii), with 96% of all neontology, extant species of f ...

fish, the most diverse group of modern vertebrates continued to diversify during the Cretaceous with the appearance of their most diverse subgroup Acanthomorpha during this period. During the Early Cretaceous, flowering plant

Flowering plants are plants that bear flowers and fruits, and form the clade Angiospermae (). The term angiosperm is derived from the Ancient Greek, Greek words (; 'container, vessel') and (; 'seed'), meaning that the seeds are enclosed with ...

s appeared and began to rapidly diversify, becoming the dominant group of plant

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with c ...

s across the Earth by the end of the Cretaceous, coincident with the decline and extinction

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

of previously widespread gymnosperm

The gymnosperms ( ; ) are a group of woody, perennial Seed plant, seed-producing plants, typically lacking the protective outer covering which surrounds the seeds in flowering plants, that include Pinophyta, conifers, cycads, Ginkgo, and gnetoph ...

groups.

The Cretaceous (along with the Mesozoic) ended with the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event

The Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) extinction event, also known as the K–T extinction, was the extinction event, mass extinction of three-quarters of the plant and animal species on Earth approximately 66 million years ago. The event cau ...

, a large mass extinction

An extinction event (also known as a mass extinction or biotic crisis) is a widespread and rapid decrease in the biodiversity on Earth. Such an event is identified by a sharp fall in the diversity and abundance of multicellular organisms. It occ ...

in which many groups, including non-avian dinosaurs, pterosaur

Pterosaurs are an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 million to 66 million years ago). Pterosaurs are the earli ...

s, and large marine reptile

Marine reptiles are reptiles which have become secondarily adapted for an aquatic or semiaquatic life in a marine environment. Only about 100 of the 12,000 extant reptile species and subspecies are classed as marine reptiles, including mari ...

s, died out, widely thought to have been caused by the impact of a large asteroid that formed the Chicxulub crater

The Chicxulub crater is an impact crater buried underneath the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. Its center is offshore, but the crater is named after the onshore community of Chicxulub Pueblo (not the larger coastal town of Chicxulub Puerto). I ...

in the Gulf of Mexico. The end of the Cretaceous is defined by the abrupt Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary

The Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) boundary, formerly known as the Cretaceous–Tertiary (K–T) boundary, is a geological signature, usually a thin band of rock containing much more iridium than other bands. The K–Pg boundary marks the end o ...

(K–Pg boundary), a geologic signature associated with the mass extinction that lies between the Mesozoic and Cenozoic

The Cenozoic Era ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterized by the dominance of mammals, insects, birds and angiosperms (flowering plants). It is the latest of three g ...

Eras.

Etymology and history

The Cretaceous as a separate period was first defined by Belgian geologist Jean d'Omalius d'Halloy in 1822 as the ''Terrain Crétacé'', usingstrata

In geology and related fields, a stratum (: strata) is a layer of Rock (geology), rock or sediment characterized by certain Lithology, lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separated by v ...

in the Paris Basin

The Paris Basin () is one of the major geological regions of France. It developed since the Triassic over remnant uplands of the Variscan orogeny (Hercynian orogeny). The sedimentary basin, no longer a single drainage basin, is a large sag in ...

and named for the extensive beds of chalk

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock. It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed deep under the sea by the compression of microscopic plankton that had settled to the sea floor. Ch ...

(calcium carbonate

Calcium carbonate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is a common substance found in Rock (geology), rocks as the minerals calcite and aragonite, most notably in chalk and limestone, eggshells, gastropod shells, shellfish skel ...

deposited by the shells of marine invertebrate

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordata, chordate s ...

s, principally coccoliths), found in the upper Cretaceous of Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

. The name Cretaceous was derived from the Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

''creta'', meaning ''chalk''. The twofold division of the Cretaceous was implemented by Conybeare and Phillips in 1822. Alcide d'Orbigny

Alcide Charles Victor Marie Dessalines d'Orbigny (6 September 1802 – 30 June 1857) was a French naturalist who made major contributions in many areas, including zoology (including malacology), palaeontology, geology, archaeology and anthropol ...

in 1840 divided the French Cretaceous into five ''étages'' (stages): the Neocomian, Aptian, Albian, Turonian, and Senonian, later adding the ''Urgonian'' between Neocomian and Aptian and the Cenomanian between the Albian and Turonian.

Geology

Subdivisions

The Cretaceous is divided into Early andLate Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the more recent of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''cre ...

epochs, or Lower and Upper Cretaceous series

Series may refer to:

People with the name

* Caroline Series (born 1951), English mathematician, daughter of George Series

* George Series (1920–1995), English physicist

Arts, entertainment, and media

Music

* Series, the ordered sets used i ...

. In older literature, the Cretaceous is sometimes divided into three series: Neocomian (lower/early), Gallic (middle) and Senonian (upper/late). A subdivision into 12 stages, all originating from European stratigraphy, is now used worldwide. In many parts of the world, alternative local subdivisions are still in use.

From youngest to oldest, the subdivisions of the Cretaceous period are:

Boundaries

The lower boundary of the Cretaceous is currently undefined, and the Jurassic–Cretaceous boundary is currently the only system boundary to lack a defined

The lower boundary of the Cretaceous is currently undefined, and the Jurassic–Cretaceous boundary is currently the only system boundary to lack a defined Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point

A Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP), sometimes referred to as a golden spike, is an internationally agreed upon reference point on a stratigraphic section which defines the lower boundary of a stage on the geologic time scale. ...

(GSSP). Placing a GSSP for this boundary has been difficult because of the strong regionality of most biostratigraphic markers, and the lack of any chemostratigraphic events, such as isotope

Isotopes are distinct nuclear species (or ''nuclides'') of the same chemical element. They have the same atomic number (number of protons in their Atomic nucleus, nuclei) and position in the periodic table (and hence belong to the same chemica ...

excursions (large sudden changes in ratios of isotopes) that could be used to define or correlate a boundary. Calpionellid

Calpionellids are an extinct group of eukaryotic single celled organisms of uncertain affinities. Their fossils are found in marine rocks of Upper Jurassic to Lower Cretaceous age. They were planktonic organisms with urn-shaped, calcitic t ...

s, an enigmatic group of plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms that drift in Hydrosphere, water (or atmosphere, air) but are unable to actively propel themselves against ocean current, currents (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are ca ...

ic protist

A protist ( ) or protoctist is any eukaryotic organism that is not an animal, land plant, or fungus. Protists do not form a natural group, or clade, but are a paraphyletic grouping of all descendants of the last eukaryotic common ancest ...

s with urn-shaped calcitic tests

Test(s), testing, or TEST may refer to:

* Test (assessment), an educational assessment intended to measure the respondents' knowledge or other abilities

Arts and entertainment

* ''Test'' (2013 film), an American film

* ''Test'' (2014 film) ...

briefly abundant during the latest Jurassic to earliest Cretaceous, have been suggested as the most promising candidates for fixing the Jurassic–Cretaceous boundary. In particular, the first appearance '' Calpionella alpina'', coinciding with the base of the eponymous Alpina subzone, has been proposed as the definition of the base of the Cretaceous. The working definition for the boundary has often been placed as the first appearance of the ammonite '' Strambergella jacobi'', formerly placed in the genus '' Berriasella'', but its use as a stratigraphic indicator has been questioned, as its first appearance does not correlate with that of ''C. alpina''. The boundary is officially considered by the International Commission on Stratigraphy

The International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS), sometimes unofficially referred to as the International Stratigraphic Commission, is a daughter or major subcommittee grade scientific organization that concerns itself with stratigraphy, strati ...

to be approximately 145 million years ago, but other estimates have been proposed based on U-Pb geochronology, ranging as young as 140 million years ago.

The upper boundary of the Cretaceous is sharply defined, being placed at an iridium

Iridium is a chemical element; it has the symbol Ir and atomic number 77. This very hard, brittle, silvery-white transition metal of the platinum group, is considered the second-densest naturally occurring metal (after osmium) with a density ...

-rich layer found worldwide that is believed to be associated with the Chicxulub impact crater, with its boundaries circumscribing parts of the Yucatán Peninsula

The Yucatán Peninsula ( , ; ) is a large peninsula in southeast Mexico and adjacent portions of Belize and Guatemala. The peninsula extends towards the northeast, separating the Gulf of Mexico to the north and west of the peninsula from the C ...

and extending into the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

. This layer has been dated at 66.043 Mya.

At the end of the Cretaceous, the impact of a large body with the Earth may have been the punctuation mark at the end of a progressive decline in biodiversity

Biodiversity is the variability of life, life on Earth. It can be measured on various levels. There is for example genetic variability, species diversity, ecosystem diversity and Phylogenetics, phylogenetic diversity. Diversity is not distribut ...

during the Maastrichtian age. The result was the extinction of three-quarters of Earth's plant and animal species. The impact created the sharp break known as the K–Pg boundary (formerly known as the K–T boundary). Earth's biodiversity required substantial time to recover from this event, despite the probable existence of an abundance of vacant ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of Resource (biology), resources an ...

s.

Despite the severity of the K-Pg extinction event, there were significant variations in the rate of extinction between and within different clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

s. Species that depended on photosynthesis

Photosynthesis ( ) is a system of biological processes by which photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical energy necessary to fuel their metabo ...

declined or became extinct as atmospheric particles blocked solar energy

Solar energy is the radiant energy from the Sun's sunlight, light and heat, which can be harnessed using a range of technologies such as solar electricity, solar thermal energy (including solar water heating) and solar architecture. It is a ...

. As is the case today, photosynthesizing organisms, such as phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater Aquatic ecosystem, ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek language, Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), mea ...

and land plant

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with c ...

s, formed the primary part of the food chain

A food chain is a linear network of links in a food web, often starting with an autotroph (such as grass or algae), also called a producer, and typically ending at an apex predator (such as grizzly bears or killer whales), detritivore (such as ...

in the late Cretaceous, and all else that depended on them suffered, as well. Herbivorous

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically evolved to feed on plants, especially upon vascular tissues such as foliage, fruits or seeds, as the main component of its diet. These more broadly also encompass animals that eat n ...

animals, which depended on plants and plankton as their food, died out as their food sources became scarce; consequently, the top predator

Predation is a biological interaction in which one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common List of feeding behaviours, feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation ...

s, such as ''Tyrannosaurus rex

''Tyrannosaurus'' () is a genus of large theropoda, theropod dinosaur. The type species ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' ( meaning 'king' in Latin), often shortened to ''T. rex'' or colloquially t-rex, is one of the best represented theropods. It live ...

'', also perished. Yet only three major groups of tetrapod

A tetrapod (; from Ancient Greek :wiktionary:τετρα-#Ancient Greek, τετρα- ''(tetra-)'' 'four' and :wiktionary:πούς#Ancient Greek, πούς ''(poús)'' 'foot') is any four-Limb (anatomy), limbed vertebrate animal of the clade Tetr ...

s disappeared completely; the non-avian dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

s, the plesiosaurs

The Plesiosauria or plesiosaurs are an Order (biology), order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared in the latest Triassic Period (geology), Period, possibly in the Rhaetian st ...

and the pterosaur

Pterosaurs are an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 million to 66 million years ago). Pterosaurs are the earli ...

s. The other Cretaceous groups that did not survive into the Cenozoic the ichthyosaur

Ichthyosauria is an order of large extinct marine reptiles sometimes referred to as "ichthyosaurs", although the term is also used for wider clades in which the order resides.

Ichthyosaurians thrived during much of the Mesozoic era; based on fo ...

s, last remaining temnospondyls ( Koolasuchus), and nonmammalian were already extinct millions of years before the event occurred.

Coccolithophorids and mollusc

Mollusca is a phylum of protostome, protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant taxon, extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum ...

s, including ammonite

Ammonoids are extinct, (typically) coiled-shelled cephalopods comprising the subclass Ammonoidea. They are more closely related to living octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish (which comprise the clade Coleoidea) than they are to nautiluses (family N ...

s, rudists, freshwater snail

Freshwater snails are gastropod mollusks that live in fresh water. There are many different families. They are found throughout the world in various habitats, ranging from ephemeral pools to the largest lakes, and from small seeps and springs t ...

s, and mussel

Mussel () is the common name used for members of several families of bivalve molluscs, from saltwater and Freshwater bivalve, freshwater habitats. These groups have in common a shell whose outline is elongated and asymmetrical compared with other ...

s, as well as organisms whose food chain included these shell builders, became extinct or suffered heavy losses. For example, ammonites

Ammonoids are extinct, (typically) coiled-shelled cephalopods comprising the subclass Ammonoidea. They are more closely related to living octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish (which comprise the clade Coleoidea) than they are to nautiluses (family N ...

are thought to have been the principal food of mosasaur

Mosasaurs (from Latin ''Mosa'' meaning the 'Meuse', and Ancient Greek, Greek ' meaning 'lizard') are an extinct group of large aquatic reptiles within the family Mosasauridae that lived during the Late Cretaceous. Their first fossil remains wer ...

s, a group of giant marine lizard

Lizard is the common name used for all Squamata, squamate reptiles other than snakes (and to a lesser extent amphisbaenians), encompassing over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most Island#Oceanic isla ...

s related to snakes that became extinct at the boundary.

Omnivores

An omnivore () is an animal that regularly consumes significant quantities of both plant and animal matter. Obtaining energy and nutrients from plant and animal matter, omnivores digest carbohydrates, protein, fat, and fiber, and metabolize t ...

, insectivores, and carrion

Carrion (), also known as a carcass, is the decaying flesh of dead animals.

Overview

Carrion is an important food source for large carnivores and omnivores in most ecosystems. Examples of carrion-eaters (or scavengers) include crows, vultures ...

-eaters survived the extinction event, perhaps because of the increased availability of their food sources. At the end of the Cretaceous, there seem to have been no purely herbivorous or carnivorous

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose nutrition and energy requirements are met by consumption of animal tissues (mainly mu ...

mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s. Mammals and birds that survived the extinction fed on insect

Insects (from Latin ') are Hexapoda, hexapod invertebrates of the class (biology), class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (Insect morphology#Head, head, ...

s, larva

A larva (; : larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into their next life stage. Animals with indirect development such as insects, some arachnids, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase ...

e, worm

Worms are many different distantly related bilateria, bilateral animals that typically have a long cylindrical tube-like body, no limb (anatomy), limbs, and usually no eyes.

Worms vary in size from microscopic to over in length for marine ...

s, and snails, which in turn fed on dead plant and animal matter. Scientists theorise that these organisms survived the collapse of plant-based food chains because they fed on detritus

In biology, detritus ( or ) is organic matter made up of the decomposition, decomposing remains of organisms and plants, and also of feces. Detritus usually hosts communities of microorganisms that colonize and decomposition, decompose (Reminera ...

.

In stream

A stream is a continuous body of water, body of surface water Current (stream), flowing within the stream bed, bed and bank (geography), banks of a channel (geography), channel. Depending on its location or certain characteristics, a strea ...

communities

A community is a Level of analysis, social unit (a group of people) with a shared socially-significant characteristic, such as place (geography), place, set of Norm (social), norms, culture, religion, values, Convention (norm), customs, or Ide ...

, few groups of animals became extinct. Stream communities rely less on food from living plants and more on detritus that washes in from land. This particular ecological niche buffered them from extinction. Similar, but more complex patterns have been found in the oceans. Extinction was more severe among animals living in the water column

The (oceanic) water column is a concept used in oceanography to describe the physical (temperature, salinity, light penetration) and chemical ( pH, dissolved oxygen, nutrient salts) characteristics of seawater at different depths for a defined ...

than among animals living on or in the seafloor. Animals in the water column are almost entirely dependent on primary production

In ecology, primary production is the synthesis of organic compounds from atmospheric or aqueous carbon dioxide. It principally occurs through the process of photosynthesis, which uses light as its source of energy, but it also occurs through ...

from living phytoplankton, while animals living on or in the ocean floor

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as seabeds.

The structure of the seabed of the global ocean is governed by plate tectonics. Most of ...

feed on detritus or can switch to detritus feeding.

The largest air-breathing survivors of the event, crocodilian

Crocodilia () is an Order (biology), order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles that are known as crocodilians. They first appeared during the Late Cretaceous and are the closest living relatives of birds. Crocodilians are a type of crocodylomorp ...

s and champsosaurs, were semiaquatic and had access to detritus. Modern crocodilians can live as scavengers and can survive for months without food and go into hibernation when conditions are unfavorable, and their young are small, grow slowly, and feed largely on invertebrates and dead organisms or fragments of organisms for their first few years. These characteristics have been linked to crocodilian survival at the end of the Cretaceous.

Geologic formations

The high sea level and warm climate of the Cretaceous meant large areas of the continents were covered by warm, shallow seas, providing habitat for many marine organisms. The Cretaceous was named for the extensive chalk deposits of this age in Europe, but in many parts of the world, the deposits from the Cretaceous are of marine

The high sea level and warm climate of the Cretaceous meant large areas of the continents were covered by warm, shallow seas, providing habitat for many marine organisms. The Cretaceous was named for the extensive chalk deposits of this age in Europe, but in many parts of the world, the deposits from the Cretaceous are of marine limestone

Limestone is a type of carbonate rock, carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material Lime (material), lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different Polymorphism (materials science) ...

, a rock type that is formed under warm, shallow marine conditions. Due to the high sea level, there was extensive space

Space is a three-dimensional continuum containing positions and directions. In classical physics, physical space is often conceived in three linear dimensions. Modern physicists usually consider it, with time, to be part of a boundless ...

for such sedimentation

Sedimentation is the deposition of sediments. It takes place when particles in suspension settle out of the fluid in which they are entrained and come to rest against a barrier. This is due to their motion through the fluid in response to th ...

. Because of the relatively young age and great thickness of the system, Cretaceous rocks are evident in many areas worldwide.

Chalk

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock. It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed deep under the sea by the compression of microscopic plankton that had settled to the sea floor. Ch ...

is a rock type characteristic for (but not restricted to) the Cretaceous. It consists of coccolith

Coccoliths are individual plates or scales of calcium carbonate formed by coccolithophores (single-celled phytoplankton such as ''Emiliania huxleyi'') and cover the cell surface arranged in the form of a spherical shell, called a '' coccosphere'' ...

s, microscopically small calcite

Calcite is a Carbonate minerals, carbonate mineral and the most stable Polymorphism (materials science), polymorph of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). It is a very common mineral, particularly as a component of limestone. Calcite defines hardness 3 on ...

skeletons of coccolithophore

Coccolithophores, or coccolithophorids, are single-celled organisms which are part of the phytoplankton, the autotrophic (self-feeding) component of the plankton community. They form a group of about 200 species, and belong either to the kingdom ...

s, a type of algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthesis, photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular ...

that prospered in the Cretaceous seas.

Stagnation of deep-sea currents in middle Cretaceous times caused anoxic conditions in the sea water leaving the deposited organic matter undecomposed. Half of the world's petroleum reserves were laid down at this time in the anoxic conditions of what would become the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Mexico. In many places around the world, dark anoxic shale

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of Clay mineral, clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g., Kaolinite, kaolin, aluminium, Al2Silicon, Si2Oxygen, O5(hydroxide, OH)4) and tiny f ...

s were formed during this interval, such as the Mancos Shale of western North America. These shales are an important source rock

In petroleum geology, source rock is a sedimentary rock which has generated hydrocarbons or which has the potential to generate hydrocarbons. Source rocks are one of the necessary elements of a working petroleum system. They are organic-rich sedim ...

for oil and gas

A fossil fuel is a flammable carbon compound- or hydrocarbon-containing material formed naturally in the Earth's crust from the buried remains of prehistoric organisms (animals, plants or microplanktons), a process that occurs within geologi ...

, for example in the subsurface of the North Sea.

Europe

In northwestern Europe, chalk deposits from the Upper Cretaceous are characteristic for theChalk Group

The Chalk Group (often just called the Chalk) is the lithostratigraphic unit (a certain number of rock strata) which contains the Upper Cretaceous limestone succession in southern and eastern England. The same or similar rock sequences occur ac ...

, which forms the white cliffs of Dover

The White Cliffs of Dover are the region of English coastline facing the Strait of Dover and France. The cliff face, which reaches a height of , owes its striking appearance to its composition of chalk accented by streaks of black flint, depo ...

on the south coast of England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

and similar cliffs on the French Normandian coast. The group is found in England, northern France, the Low Countries

The Low Countries (; ), historically also known as the Netherlands (), is a coastal lowland region in Northwestern Europe forming the lower Drainage basin, basin of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta and consisting today of the three modern "Bene ...

, northern Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

and in the subsurface of the southern part of the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

. Chalk is not easily consolidated and the Chalk Group still consists of loose sediments in many places. The group also has other limestone

Limestone is a type of carbonate rock, carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material Lime (material), lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different Polymorphism (materials science) ...

s and arenites. Among the fossils it contains are sea urchin

Sea urchins or urchins () are echinoderms in the class (biology), class Echinoidea. About 950 species live on the seabed, inhabiting all oceans and depth zones from the intertidal zone to deep seas of . They typically have a globular body cove ...

s, belemnites, ammonite

Ammonoids are extinct, (typically) coiled-shelled cephalopods comprising the subclass Ammonoidea. They are more closely related to living octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish (which comprise the clade Coleoidea) than they are to nautiluses (family N ...

s and sea reptiles such as ''Mosasaurus

''Mosasaurus'' (; "lizard of the Meuse (river), Meuse River") is the type genus (defining example) of the mosasaurs, an extinct group of aquatic Squamata, squamate reptiles. It lived from about 82 to 66 million years ago during the Campanian an ...

''.

In southern Europe, the Cretaceous is usually a marine system consisting of competent limestone beds or incompetent marl

Marl is an earthy material rich in carbonate minerals, Clay minerals, clays, and silt. When Lithification, hardened into rock, this becomes marlstone. It is formed in marine or freshwater environments, often through the activities of algae.

M ...

s. Because the Alpine mountain chains did not yet exist in the Cretaceous, these deposits formed on the southern edge of the European continental shelf

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an islan ...

, at the margin of the Tethys Ocean

The Tethys Ocean ( ; ), also called the Tethys Sea or the Neo-Tethys, was a prehistoric ocean during much of the Mesozoic Era and early-mid Cenozoic Era. It was the predecessor to the modern Indian Ocean, the Mediterranean Sea, and the Eurasia ...

.

North America

During the Cretaceous, the present North American continent was isolated from the other continents. In the Jurassic, the North Atlantic already opened, leaving a proto-ocean between Europe and North America. From north to south across the continent, theWestern Interior Seaway

The Western Interior Seaway (also called the Cretaceous Seaway, the Niobraran Sea, the North American Inland Sea, or the Western Interior Sea) was a large inland sea (geology), inland sea that existed roughly over the present-day Great Plains of ...

started forming. This inland sea separated the elevated areas of Laramidia

Laramidia was an island continent that existed during the Late Cretaceous period (99.6–66 Year#SI prefix multipliers, Ma), when the Western Interior Seaway split the continent of North America in two. In the Mesozoic era, Laramidia was an island ...

in the west and Appalachia

Appalachia ( ) is a geographic region located in the Appalachian Mountains#Regions, central and southern sections of the Appalachian Mountains in the east of North America. In the north, its boundaries stretch from the western Catskill Mountai ...

in the east. Three dinosaur clades found in Laramidia (troodontids, therizinosaurids and oviraptorosaurs) are absent from Appalachia from the Coniacian through the Maastrichtian.

Paleogeography

During the Cretaceous, the late-Paleozoic

The Paleozoic ( , , ; or Palaeozoic) Era is the first of three Era (geology), geological eras of the Phanerozoic Eon. Beginning 538.8 million years ago (Ma), it succeeds the Neoproterozoic (the last era of the Proterozoic Eon) and ends 251.9 Ma a ...

-to-early-Mesozoic supercontinent

In geology, a supercontinent is the assembly of most or all of Earth's continent, continental blocks or cratons to form a single large landmass. However, some geologists use a different definition, "a grouping of formerly dispersed continents", ...

of Pangaea

Pangaea or Pangea ( ) was a supercontinent that existed during the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras. It assembled from the earlier continental units of Gondwana, Euramerica and Siberia during the Carboniferous period approximately 335 mi ...

completed its tectonic

Tectonics ( via Latin ) are the processes that result in the structure and properties of the Earth's crust and its evolution through time. The field of ''planetary tectonics'' extends the concept to other planets and moons.

These processes ...

breakup into the present-day continent

A continent is any of several large geographical regions. Continents are generally identified by convention (norm), convention rather than any strict criteria. A continent could be a single large landmass, a part of a very large landmass, as ...

s, although their positions were substantially different at the time. As the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

widened, the convergent-margin mountain building ( orogenies) that had begun during the Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 143.1 Mya. ...

continued in the North American Cordillera, as the Nevadan orogeny

The Nevadan orogeny occurred along the western margin of North America during the Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous approximately 155 Ma to 145 Ma. Throughout the duration of this orogeny there were at least two different kinds of orogenic process ...

was followed by the Sevier and Laramide orogenies.

Gondwana

Gondwana ( ; ) was a large landmass, sometimes referred to as a supercontinent. The remnants of Gondwana make up around two-thirds of today's continental area, including South America, Africa, Antarctica, Australia (continent), Australia, Zea ...

had begun to break up during the Jurassic Period, but its fragmentation accelerated during the Cretaceous and was largely complete by the end of the period. South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a considerably smaller portion in the Northern Hemisphere. It can also be described as the southern Subregion#Americas, subregion o ...

, Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...

, and Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

rifted away from Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

(though India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

and Madagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

remained attached to each other until around 80 million years ago); thus, the South Atlantic and Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

s were newly formed. Such active rifting lifted great undersea mountain chains along the welts, raising eustatic sea levels worldwide. To the north of Africa the Tethys Sea continued to narrow. During most of the Late Cretaceous, North America would be divided in two by the Western Interior Seaway

The Western Interior Seaway (also called the Cretaceous Seaway, the Niobraran Sea, the North American Inland Sea, or the Western Interior Sea) was a large inland sea (geology), inland sea that existed roughly over the present-day Great Plains of ...

, a large interior sea, separating Laramidia

Laramidia was an island continent that existed during the Late Cretaceous period (99.6–66 Year#SI prefix multipliers, Ma), when the Western Interior Seaway split the continent of North America in two. In the Mesozoic era, Laramidia was an island ...

to the west and Appalachia

Appalachia ( ) is a geographic region located in the Appalachian Mountains#Regions, central and southern sections of the Appalachian Mountains in the east of North America. In the north, its boundaries stretch from the western Catskill Mountai ...

to the east, then receded late in the period, leaving thick marine deposits sandwiched between coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other Chemical element, elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal i ...

beds. Bivalve palaeobiogeography also indicates that Africa was split in half by a shallow sea during the Coniacian and Santonian, connecting the Tethys with the South Atlantic by way of the central Sahara and Central Africa, which were then underwater. Yet another shallow seaway ran between what is now Norway and Greenland, connecting the Tethys to the Arctic Ocean and enabling biotic exchange between the two oceans. At the peak of the Cretaceous transgression, one-third of Earth's present land area was submerged.

The Cretaceous is justly famous for its chalk

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock. It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed deep under the sea by the compression of microscopic plankton that had settled to the sea floor. Ch ...

; indeed, more chalk formed in the Cretaceous than in any other period in the Phanerozoic

The Phanerozoic is the current and the latest of the four eon (geology), geologic eons in the Earth's geologic time scale, covering the time period from 538.8 million years ago to the present. It is the eon during which abundant animal and ...

. Mid-ocean ridge activity—or rather, the circulation of seawater through the enlarged ridges—enriched the oceans in calcium; this made the oceans more saturated, as well as increased the bioavailability of the element for Coccolithophores, calcareous nanoplankton. These widespread carbonates and other sedimentary rock, sedimentary deposits make the Cretaceous rock record especially fine. Famous Geologic formation, formations from North America include the rich marine fossils of Kansas's Smoky Hill Chalk Member and the terrestrial fauna of the late Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation. Other important Cretaceous exposures occur in Europe (e.g., the Weald) and China (the Yixian Formation). In the area that is now India, massive lava beds called the Deccan Traps erupted in the very late Cretaceous and early Paleocene.

Climate

Palynology, Palynological evidence indicates the Cretaceous climate had three broad phases: a Berriasian–Barremian warm-dry phase, an Aptian–Santonian warm-wet phase, and a Campanian–Maastrichtian cool-dry phase. As in the Cenozoic, the 400,000 year eccentricity cycle was the dominant orbital cycle governing carbon flux between different reservoirs and influencing global climate. The location of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) was roughly the same as in the present. The cooling trend of the last epoch of the Jurassic, the Tithonian, continued into the Berriasian, the first age of the Cretaceous. The North Atlantic seaway opened and enabled the flow of cool water from the Boreal Ocean into the Tethys. There is evidence that snowfalls were common in the higher latitudes during this age, and the tropics became wetter than during the Triassic and Jurassic. Glaciation was restricted to high-latitude mountains, though seasonal snow may have existed farther from the poles. After the end of the first age, however, temperatures began to increase again, with a number of thermal excursions, such as the middle Valanginian Weissert Event, Weissert Thermal Excursion (WTX), which was caused by the Paraná-Etendeka Large Igneous Province's activity. It was followed by the middle Hauterivian Faraoni Thermal Excursion (FTX) and the early Barremian Hauptblatterton Thermal Event (HTE). The HTE marked the ultimate end of the Tithonian-early Barremian Cool Interval (TEBCI). During this interval, precession was the dominant orbital driver of environmental changes in the Vocontian Basin. For much of the TEBCI, northern Gondwana experienced a monsoonal climate. A shallow thermocline existed in the mid-latitude Tethys. The TEBCI was followed by the Barremian-Aptian Warm Interval (BAWI). This hot climatic interval coincides with Manihiki Plateau, Manihiki and Ontong Java Plateau volcanism and with the Selli Event. Early Aptian tropical sea surface temperatures (SSTs) were 27–32 °C, based on TEX86, TEX86 measurements from the equatorial Pacific. During the Aptian, Milankovitch cycles governed the occurrence of anoxic events by modulating the intensity of the hydrological cycle and terrestrial runoff. The early Aptian was also notable for its millennial scale hyperarid events in the mid-latitudes of Asia. The BAWI itself was followed by the Aptian-Albian Cold Snap (AACS) that began about 118 Ma. A short, relatively minor ice age may have occurred during this so-called "cold snap", as evidenced by glacial dropstones in the western parts of the Tethys Ocean and the expansion of calcareous nannofossils that dwelt in cold water into lower latitudes. The AACS is associated with an arid period in the Iberian Peninsula. Temperatures increased drastically after the end of the AACS, which ended around 111 Ma with the Paquier/Urbino Thermal Maximum, giving way to the Mid-Cretaceous Hothouse (MKH), which lasted from the early Albian until the early Campanian. Faster rates of seafloor spreading and entry of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere are believed to have initiated this period of extreme warmth, along with high flood basalt activity. The MKH was punctuated by multiple thermal maxima of extreme warmth. The Leenhardt Thermal Event (LTE) occurred around 110 Ma, followed shortly by the l’Arboudeyesse Thermal Event (ATE) a million years later. Following these two hyperthermals was the Amadeus Event, Amadeus Thermal Maximum around 106 Ma, during the middle Albian. Then, around a million years after that, occurred the Petite Verol Thermal Event (PVTE). Afterwards, around 102.5 Ma, the Event 6 Thermal Event (EV6) took place; this event was itself followed by the Breistroffer Thermal Maximum around 101 Ma, during the latest Albian. Approximately 94 Ma, the Cenomanian-Turonian Thermal Maximum occurred, with this hyperthermal being the most extreme hothouse interval of the Cretaceous and being associated with a sea level highstand. Temperatures cooled down slightly over the next few million years, but then another thermal maximum, the Coniacian Thermal Maximum, happened, with this thermal event being dated to around 87 Ma. Atmospheric CO2 levels may have varied by thousands of ppm throughout the MKH. Mean annual temperatures at the poles during the MKH exceeded 14 °C. Such hot temperatures during the MKH resulted in a very gentle temperature gradient from the equator to the poles; the latitudinal temperature gradient during the Cenomanian-Turonian Thermal Maximum was 0.54 °C per ° latitude for the Southern Hemisphere and 0.49 °C per ° latitude for the Northern Hemisphere, in contrast to present day values of 1.07 and 0.69 °C per ° latitude for the Southern and Northern hemispheres, respectively. This meant weaker global winds, which drive the ocean currents, and resulted in less upwelling and more stagnant oceans than today. This is evidenced by widespread blackshale

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of Clay mineral, clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g., Kaolinite, kaolin, aluminium, Al2Silicon, Si2Oxygen, O5(hydroxide, OH)4) and tiny f ...

deposition and frequent anoxic events. Tropical SSTs during the late Albian most likely averaged around 30 °C. Despite this high SST, seawater was not hypersaline at this time, as this would have required significantly higher temperatures still. On land, arid zones in the Albian regularly expanded northward in tandem with expansions of subtropical high pressure belts. The Cedar Mountain Formation's Soap Wash flora indicates a mean annual temperature of between 19 and 26 °C in Utah at the Albian-Cenomanian boundary. Tropical SSTs during the Cenomanian-Turonian Thermal Maximum were at least 30 °C, though one study estimated them as high as between 33 and 42 °C. An intermediate estimate of ~33-34 °C has also been given. Meanwhile, deep ocean temperatures were as much as warmer than today's; one study estimated that deep ocean temperatures were between 12 and 20 °C during the MKH. The poles were so warm that ectothermic reptiles were able to inhabit them.

Beginning in the Santonian, near the end of the MKH, the global climate began to cool, with this cooling trend continuing across the Campanian. This period of cooling, driven by falling levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide, caused the end of the MKH and the transition into a cooler climatic interval, known formally as the Late Cretaceous-Early Palaeogene Cool Interval (LKEPCI). Tropical SSTs declined from around 35 °C in the early Campanian to around 28 °C in the Maastrichtian. Deep ocean temperatures declined to 9 to 12 °C, though the shallow temperature gradient between tropical and polar seas remained. Regional conditions in the Western Interior Seaway

The Western Interior Seaway (also called the Cretaceous Seaway, the Niobraran Sea, the North American Inland Sea, or the Western Interior Sea) was a large inland sea (geology), inland sea that existed roughly over the present-day Great Plains of ...

changed little between the MKH and the LKEPCI. During this period of relatively cool temperatures, the ITCZ became narrower, while the strength of both summer and winter monsoons in East Asia was directly correlated to atmospheric Carbon dioxide, CO2 concentrations. Laramidia likewise had a seasonal, monsoonal climate. The Maastrichtian was a time of chaotic, highly variable climate. Two upticks in global temperatures are known to have occurred during the Maastrichtian, bucking the trend of overall cooler temperatures during the LKEPCI. Between 70 and 69 Ma and 66–65 Ma, isotopic ratios indicate elevated atmospheric CO2 pressures with levels of 1000–1400 ppmV and mean annual temperatures in west Texas between . Atmospheric CO2 and temperature relations indicate a doubling of pCO2 was accompanied by a ~0.6 °C increase in temperature. The latter warming interval, occurring at the very end of the Cretaceous, was triggered by the activity of the Deccan Traps. The LKEPCI lasted into the Late Paleocene, Late Palaeocene, when it gave way to another supergreenhouse interval.

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

fossils have been found within 15 degrees of the Cretaceous south pole. It was suggested that there was Antarctica, Antarctic marine glaciation in the Turonian Age, based on isotopic evidence. However, this has subsequently been suggested to be the result of inconsistent isotopic proxies, with evidence of polar rainforests during this time interval at 82° S. Rafting by ice of stones into marine environments occurred during much of the Cretaceous, but evidence of deposition directly from glaciers is limited to the Early Cretaceous of the Eromanga Basin in southern Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

.

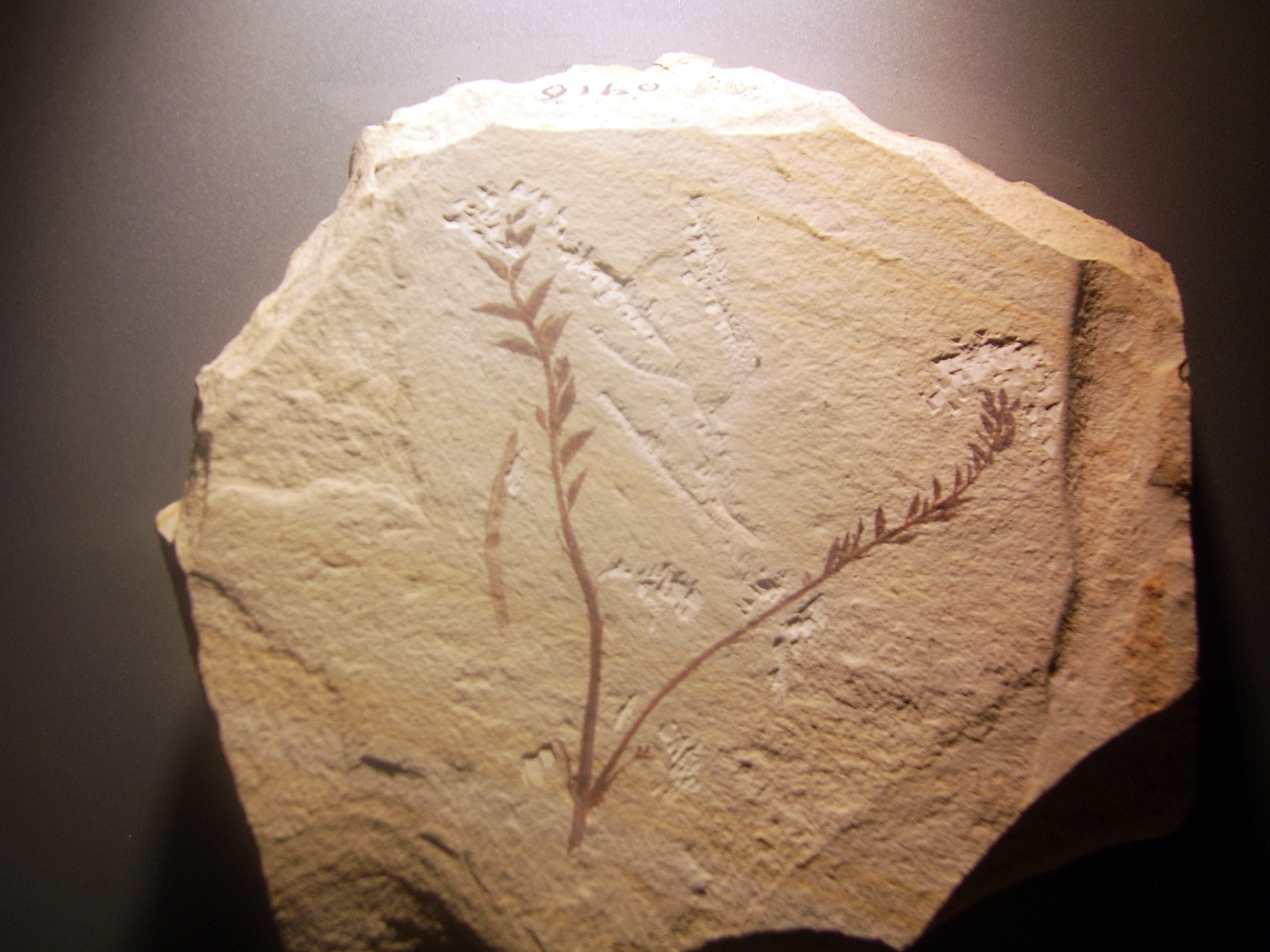

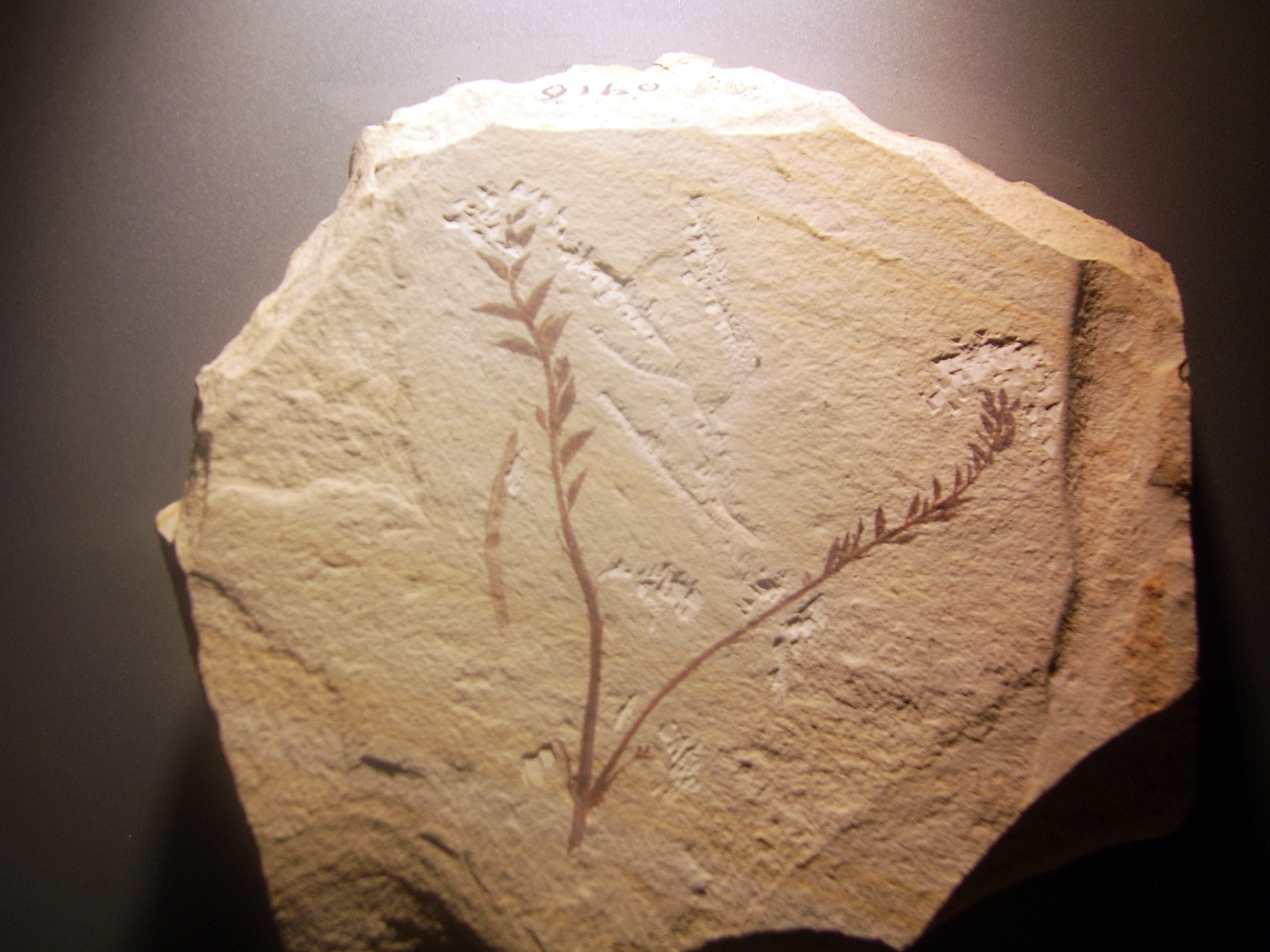

Flora

Flowering plants (angiosperms) make up around 90% of living plant species today. Prior to the rise of angiosperms, during the Jurassic and the Early Cretaceous, the higher flora was dominated by

Flowering plants (angiosperms) make up around 90% of living plant species today. Prior to the rise of angiosperms, during the Jurassic and the Early Cretaceous, the higher flora was dominated by gymnosperm

The gymnosperms ( ; ) are a group of woody, perennial Seed plant, seed-producing plants, typically lacking the protective outer covering which surrounds the seeds in flowering plants, that include Pinophyta, conifers, cycads, Ginkgo, and gnetoph ...

groups, including cycads, Pinophyta, conifers, ginkgophytes, Gnetophyta, gnetophytes and close relatives, as well as the extinct Bennettitales. Other groups of plants included Pteridospermatophyta, pteridosperms or "seed ferns", a collective term that refers to disparate groups of extinct seed plants with fern-like foliage, including groups such as Corystospermaceae and Caytoniales. The exact origins of angiosperms are uncertain, although molecular evidence suggests that they are not closely related to any living group of gymnosperms.

The earliest widely accepted evidence of flowering plants are monosulcate (single-grooved) pollen grains from the late Valanginian (~ 134 million years ago) found in Israel and Italy, initially at low abundance. Molecular clock estimates conflict with fossil estimates, suggesting the diversification of Crown group, crown-group angiosperms during the Late Triassic or the Jurassic, but such estimates are difficult to reconcile with the heavily sampled pollen record and the distinctive tricolpate to tricolporoidate (triple grooved) pollen of Eudicots, eudicot angiosperms. Among the oldest records of Angiosperm macrofossils are ''Montsechia'' from the Barremian aged La Huérguina Formation, Las Hoyas beds of Spain and ''Archaefructus'' from the Barremian-Aptian boundary Yixian Formation in China. Tricolpate pollen distinctive of eudicots first appears in the Late Barremian, while the earliest remains of monocots are known from the Aptian. Flowering plants underwent a rapid radiation beginning during the middle Cretaceous, becoming the dominant group of land plants by the end of the period, coincident with the decline of previously dominant groups such as conifers. The oldest known fossils of Poaceae, grasses are from the Albian, with the family having diversified into modern groups by the end of the Cretaceous. The oldest large angiosperm trees are known from the Turonian (c. 90 Mya) of New Jersey, with the trunk having a preserved diameter of and an estimated height of .

During the Cretaceous, ferns in the order Polypodiales, which make up 80% of living fern species, would also begin to diversify.

Terrestrial fauna

On land,mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s were generally small sized, but a very relevant component of the Fauna (animals), fauna, with cimolodont multituberculates outnumbering dinosaurs in some sites. Neither true marsupial

Marsupials are a diverse group of mammals belonging to the infraclass Marsupialia. They are natively found in Australasia, Wallacea, and the Americas. One of marsupials' unique features is their reproductive strategy: the young are born in a r ...

s nor placentals existed until the very end, but a variety of non-marsupial metatherians and non-placental eutherians had already begun to diversify greatly, ranging as carnivores (Deltatheroida), aquatic foragers (Stagodontidae) and herbivores (''Schowalteria'', Zhelestidae). Various "archaic" groups like eutriconodonts were common in the Early Cretaceous, but by the Late Cretaceous northern mammalian faunas were dominated by multituberculates and therians, with dryolestoids dominating South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a considerably smaller portion in the Northern Hemisphere. It can also be described as the southern Subregion#Americas, subregion o ...

.

The apex predators were archosaurian reptiles, especially dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

s, which were at their most diverse stage. Avians such as the ancestors of modern-day birds

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

also diversified. They inhabited every continent, and were even found in cold polar latitudes. Pterosaurs were common in the early and middle Cretaceous, but as the Cretaceous proceeded they declined for poorly understood reasons (once thought to be due to competition with early birds, but now it is understood avian adaptive radiation is not consistent with pterosaur decline). By the end of the period only three highly specialized Family (biology), families remained; Pteranodontidae, Nyctosauridae, and Azhdarchidae.

The Liaoning lagerstätte (Yixian Formation) in China is an important site, full of preserved remains of numerous types of small dinosaurs, birds and mammals, that provides a glimpse of life in the Early Cretaceous. The coelurosaur dinosaurs found there represent types of the group Maniraptora, which includes modern birds and their closest non-avian relatives, such as dromaeosaurs, oviraptorosaurs, therizinosaurs, troodontids along with other avialans. Fossils of these dinosaurs from the Liaoning lagerstätte are notable for the presence of hair-like feathers.

Insects diversified during the Cretaceous, and the oldest known ants, termites and some lepidopterans, akin to Butterfly, butterflies and moths, appeared. Aphids, grasshoppers and gall wasps appeared.

Tyrannosaurus rex

''Tyrannosaurus'' () is a genus of large theropoda, theropod dinosaur. The type species ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' ( meaning 'king' in Latin), often shortened to ''T. rex'' or colloquially t-rex, is one of the best represented theropods. It live ...

'', one of the largest land predators of all time, lived during the Late Cretaceous

File: Velociraptor Restoration.png, Up to 2 m long and 0.5 m high at the hip, ''Velociraptor'' was feathered and roamed the Late Cretaceous

File: Triceratops by Tom Patker.png, ''Triceratops'', one of the most recognizable genera of the Cretaceous

File:Quetzalcoatlus07.jpg, The azhdarchid ''Quetzalcoatlus'', one of the largest animals to ever fly, lived during the Late Cretaceous

File:Confuciusornis sanctus mmartyniuk.png, ''Confuciusornis'', a genus of crow-sized birds from the Early Cretaceous

File:Ichthyornis restoration.jpeg, ''Ichthyornis'' was a toothed, seabird-like ornithuran from the Late Cretaceous

Rhynchocephalians

Rhynchocephalians (which today only includes the tuatara) disappeared from North America and Europe after the Early Cretaceous, and were absent from North Africa and northern South America by the early

Rhynchocephalians (which today only includes the tuatara) disappeared from North America and Europe after the Early Cretaceous, and were absent from North Africa and northern South America by the early Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the more recent of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''cre ...

. The cause of the decline of Rhynchocephalia remains unclear, but has often been suggested to be due to competition with advanced lizards and mammals. They appear to have remained diverse in high-latitude southern South America during the Late Cretaceous, where lizards remained rare, with their remains outnumbering terrestrial lizards 200:1.

Choristodera

Choristodera, Choristoderes, a group of freshwater aquatic reptiles that first appeared during the preceding Jurassic, underwent a major evolutionary radiation in Asia during the Early Cretaceous, which represents the high point of choristoderan diversity, including long necked forms such as ''Hyphalosaurus'' and the first records of the gharial-like Neochoristodera, which appear to have evolved in the regional absence of aquatic neosuchian crocodyliformes. During the Late Cretaceous the neochoristodere ''Champsosaurus'' was widely distributed across western North America. Due to the extreme climatic warmth in the Arctic, choristoderans were able to colonise it too during the Late Cretaceous.

Choristodera, Choristoderes, a group of freshwater aquatic reptiles that first appeared during the preceding Jurassic, underwent a major evolutionary radiation in Asia during the Early Cretaceous, which represents the high point of choristoderan diversity, including long necked forms such as ''Hyphalosaurus'' and the first records of the gharial-like Neochoristodera, which appear to have evolved in the regional absence of aquatic neosuchian crocodyliformes. During the Late Cretaceous the neochoristodere ''Champsosaurus'' was widely distributed across western North America. Due to the extreme climatic warmth in the Arctic, choristoderans were able to colonise it too during the Late Cretaceous.

Marine fauna

In the seas, batoidea, rays, modern sharks and teleosts became common. Marine reptiles includedichthyosaur

Ichthyosauria is an order of large extinct marine reptiles sometimes referred to as "ichthyosaurs", although the term is also used for wider clades in which the order resides.

Ichthyosaurians thrived during much of the Mesozoic era; based on fo ...

s in the early and mid-Cretaceous (becoming extinct during the late Cretaceous Cenomanian-Turonian anoxic event), plesiosaurs throughout the entire period, and mosasaur

Mosasaurs (from Latin ''Mosa'' meaning the 'Meuse', and Ancient Greek, Greek ' meaning 'lizard') are an extinct group of large aquatic reptiles within the family Mosasauridae that lived during the Late Cretaceous. Their first fossil remains wer ...

s appearing in the Late Cretaceous. Sea turtles in the form of Cheloniidae and Panchelonioidea lived during the period and survived the extinction event. Panchelonioidea is today represented by a single species; the leatherback sea turtle. The Hesperornithiformes were flightless, marine diving birds that swam like grebes.

''Baculites'', an ammonite

Ammonoids are extinct, (typically) coiled-shelled cephalopods comprising the subclass Ammonoidea. They are more closely related to living octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish (which comprise the clade Coleoidea) than they are to nautiluses (family N ...

genus with a straight shell, flourished in the seas along with reef-building rudist clams. Inoceramidae, Inoceramids were also particularly notable among Cretaceous bivalves, and they have been used to identify major biotic turnovers such as at the Turonian-Coniacian boundary. Predatory gastropods with drilling habits were widespread. Globotruncanid foraminifera and echinoderms such as sea urchins and Asteroidea, starfish (sea stars) thrived. Ostracods were abundant in Cretaceous marine settings; ostracod species characterised by high male sexual investment had the highest rates of extinction and turnover. Thylacocephala, a class of crustaceans, went extinct in the Late Cretaceous. The first radiation of the diatoms (generally silicon dioxide, siliceous shelled, rather than calcareous) in the oceans occurred during the Cretaceous; freshwater diatoms did not appear until the Miocene. Calcareous nannoplankton were important components of the marine microbiota and important as biostratigraphic markers and recorders of environmental change.

The Cretaceous was also an important interval in the evolution of bioerosion, the production of borings and scrapings in rocks, hardgrounds and shells.

mosasaur

Mosasaurs (from Latin ''Mosa'' meaning the 'Meuse', and Ancient Greek, Greek ' meaning 'lizard') are an extinct group of large aquatic reptiles within the family Mosasauridae that lived during the Late Cretaceous. Their first fossil remains wer ...

, carnivorous marine reptiles that emerged in the late Cretaceous.

File:Hesperornis BW (white background).jpg, Strong-swimming and toothed predatory waterbird ''Hesperornis'' roamed late Cretacean oceans.

File:DiscoscaphitesirisCretaceous.jpg, The ammonite

Ammonoids are extinct, (typically) coiled-shelled cephalopods comprising the subclass Ammonoidea. They are more closely related to living octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish (which comprise the clade Coleoidea) than they are to nautiluses (family N ...

''Discoscaphites iris'', Owl Creek Formation (Upper Cretaceous), Ripley, Mississippi

File:The fossils from Cretaceous age found in Lebanon.jpg, A plate with ''Nematonotus sp.'', ''Pseudostacus sp.'' and a partial ''Dercetis triqueter'', found in Hakel, Lebanon

File:Cretoxyrhina attacking Pteranodon.png, ''Cretoxyrhina'', one of the largest Cretaceous sharks, attacking a ''Pteranodon'' in the Western Interior Seaway

The Western Interior Seaway (also called the Cretaceous Seaway, the Niobraran Sea, the North American Inland Sea, or the Western Interior Sea) was a large inland sea (geology), inland sea that existed roughly over the present-day Great Plains of ...

See also

* Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction * Cretaceous Thermal Maximum * List of fossil sites (with link directory) * South Polar region of the CretaceousReferences

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * —detailed coverage of various aspects of the evolutionary history of the insects. * * *External links

UCMP Berkeley Cretaceous page

* {{Authority control Cretaceous, Geological periods