corvée labor on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Corvée () is a form of unpaid

Corvée () is a form of unpaid

From the Egyptian Old Kingdom (, the

From the Egyptian Old Kingdom (, the

In the Russian Tsardom and the

In the Russian Tsardom and the

File:Marlik clay bowl REM.JPG, Clay bowl, , one day corvée ration(?). Marlik, Iran

File:Amarna letter mp3h8879.jpg, Amarna letter 365, Nuribta

Corvée () is a form of unpaid

Corvée () is a form of unpaid forced labour

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, or violence, including death or other forms of ...

that is intermittent in nature, lasting for limited periods of time, typically only a certain number of days' work each year. Statute labour is a corvée imposed by a state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

for the purposes of public works

Public works are a broad category of infrastructure projects, financed and procured by a government body for recreational, employment, and health and safety uses in the greater community. They include public buildings ( municipal buildings, ...

. As such it represents a form of levy (taxation

A tax is a mandatory financial charge or levy imposed on an individual or legal person, legal entity by a governmental organization to support government spending and public expenditures collectively or to Pigouvian tax, regulate and reduce nega ...

). Unlike other forms of levy, such as a tithe

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Modern tithes are normally voluntary and paid in money, cash, cheques or v ...

, a corvée does not require the population to have land, crops or cash.

The obligation for tenant farmers to perform corvée work for landlords on private landed estate

In real estate, a landed property or landed estate is a property that generates income for the owner (typically a member of the gentry) without the owner having to do the actual work of the estate.

In medieval Western Europe, there were two compe ...

s was widespread throughout history before the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

. The term is most typically used in reference to medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

and early modern Europe

Early modern Europe, also referred to as the post-medieval period, is the period of European history between the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, roughly the mid 15th century to the late 18th century. Histori ...

, where work was often expected by a feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of struc ...

landowner of their vassals, or by a monarch of their subjects.

The application of the term is not limited to feudal Europe; corvée has also existed in modern and ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

, ancient Sumer, ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of Rome, founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, collapse of the Western Roman Em ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

, the Incan

The Inca Empire, officially known as the Realm of the Four Parts (, ), was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The administrative, political, and military center of the empire was in the city of Cusco. The Inca civilisation rose fr ...

civilization, Haiti

Haiti, officially the Republic of Haiti, is a country on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and south of the Bahamas. It occupies the western three-eighths of the island, which it shares with the Dominican ...

under Henry I and under American occupation (1915–1934), and Portugal's African colonies until the mid-1960s. Forms of statute labour officially existed until the early 20th century in Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

and the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

.

Etymology

The word ''corvée'' has its origins in Rome, and reached English via French. In thelater Roman Empire

In historiography, the Late or Later Roman Empire, traditionally covering the period from 284 CE to 641 CE, was a time of significant transformation in Roman governance, society, and religion. Diocletian's reforms, including the establishment of t ...

the citizens performed in lieu of paying taxes; often it consisted of road and bridge work. Roman landlords could also demand a certain number of days' labour from their tenants, and from freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, slaves were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their owners), emancipation (granted freedom as part of a larger group), or self- ...

; in the latter case the work was called . In medieval Europe, the tasks that serf

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed du ...

s or villein

A villein is a class of serfdom, serf tied to the land under the feudal system. As part of the contract with the lord of the manor, they were expected to spend some of their time working on the lord's fields in return for land. Villeins existe ...

s were required to perform on a yearly basis for their lords were called . Plowing and harvesting were principal activities to which this applied. In times of need, the lord could demand additional work called (). This term evolved into , then , and finally ''corvée'', and the meaning broadened to encompass both the regular and exceptional tasks. The word survives in modern usage, meaning any kind of inevitable or disagreeable chore.

History

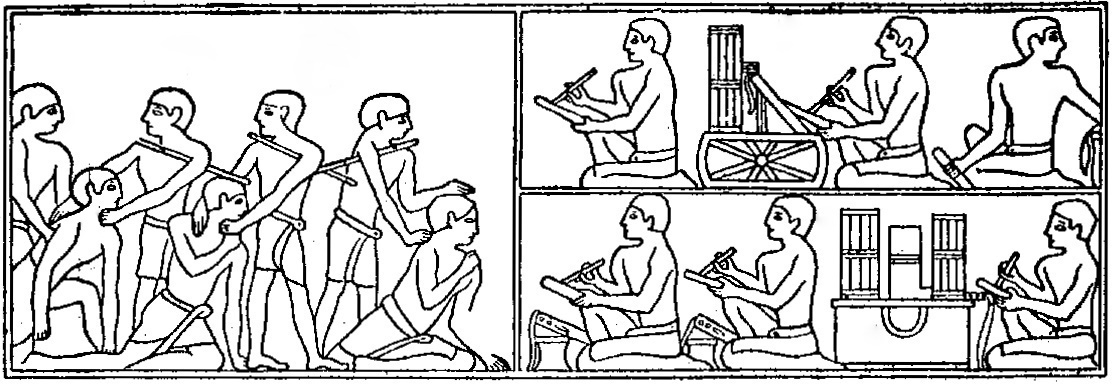

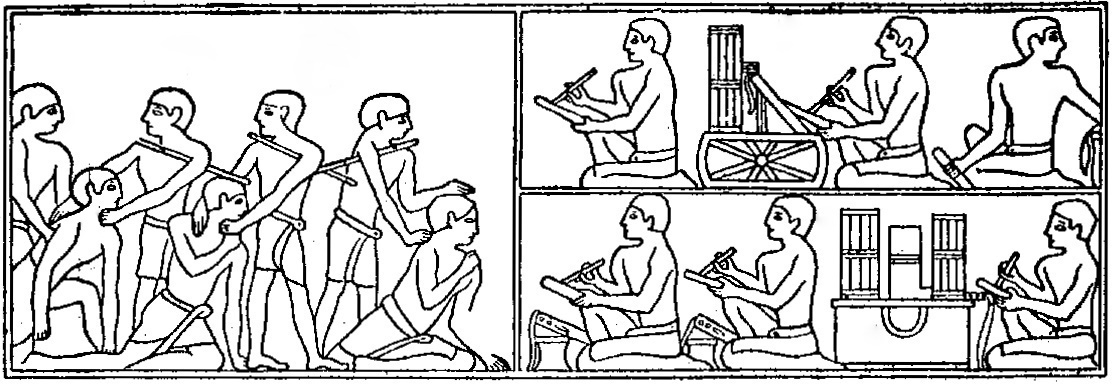

Egypt

From the Egyptian Old Kingdom (, the

From the Egyptian Old Kingdom (, the 4th Dynasty

The Fourth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (notated Dynasty IV) is characterized as a "golden age" of the Old Kingdom of Egypt. Dynasty IV lasted from to c. 2498 BC. It was a time of peace and prosperity as well as one during which trade with othe ...

) onward, corvée contributed to government projects. During the times of the Nile River

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the longest river i ...

floods, it was used for construction projects such as pyramids

A pyramid () is a Nonbuilding structure, structure whose visible surfaces are triangular in broad outline and converge toward the top, making the appearance roughly a Pyramid (geometry), pyramid in the geometric sense. The base of a pyramid ca ...

, temples, quarries, canals, roads, and other works.

The 1350 BC Amarna letters, mostly addressed to the pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian language, Egyptian: ''wikt:pr ꜥꜣ, pr ꜥꜣ''; Meroitic language, Meroitic: 𐦲𐦤𐦧, ; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') was the title of the monarch of ancient Egypt from the First Dynasty of Egypt, First Dynasty ( ...

of Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

, have one short letter on the topic of corvée. Of the 382 Amarna letters, there is an undamaged letter from Biridiya

Biridiya was the ruler of Megiddo, northern part of the southern Levant, in the 14th century BC. At the time Megiddo was a city-state submitting to the Egyptian Empire. He is part of the intrigues surrounding the rebel Labaya of Shechem.

History ...

of Megiddo Megiddo may refer to:

Places and sites in Israel

* Tel Megiddo, site of an ancient city in Israel's Jezreel valley

* Megiddo Airport, a domestic airport in Israel

* Megiddo church (Israel)

* Megiddo, Israel, a kibbutz in Israel

* Megiddo Juncti ...

entitled " Furnishing corvée workers".

Later, during the Ptolemaic dynasty

The Ptolemaic dynasty (; , ''Ptolemaioi''), also known as the Lagid dynasty (, ''Lagidai''; after Ptolemy I's father, Lagus), was a Macedonian Greek royal house which ruled the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Ancient Egypt during the Hellenistic period. ...

, Ptolemy V

Ptolemy V Epiphanes Eucharistus (, ''Ptolemaĩos Epiphanḗs Eukháristos'' "Ptolemy the Manifest, the Beneficent"; 9 October 210–September 180 BC) was the King of Ptolemaic Egypt from July or August 204 BC until his death in 180 BC.

Ptolemy ...

in his Rosetta Stone Decree of 196 BC listed 22 accomplishments to be honored and ten rewards granted to him for the former. One of the shorter accomplishments, near the middle of the list, is:

The statement implies it was a common practice.

Until the late 19th century, many of the Egyptian Public Works

The Egyptian Department of Public Works was established in the early 19th century, and concentrates mainly on public works relating to irrigation and hydraulic engineering. These irrigation projects have constituted the bulk of work performed by th ...

, including the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

, were built using corvée. Legally, the practice ended in Egypt after 1882, when the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

took control of the country and opposed forced labour on principle, but its abolition was postponed until Egypt had paid off its foreign debts. During the 19th century corvée had expanded into a national program. It was favoured for short-term projects such as building irrigation works and dams. However, Nile Delta

The Nile Delta (, or simply , ) is the River delta, delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's larger deltas—from Alexandria in the west to Port Said in the eas ...

landowners replaced it with cheap temporary labour recruited from Upper Egypt

Upper Egypt ( ', shortened to , , locally: ) is the southern portion of Egypt and is composed of the Nile River valley south of the delta and the 30th parallel North. It thus consists of the entire Nile River valley from Cairo south to Lake N ...

. As a result, it was used only in scattered locales, and even then there was peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasan ...

resistance. It began to disappear as Egypt modernized after 1860, and had fully vanished by the 1890s.

Europe

Medieval agricultural corvée was not entirely unpaid. By custom the workers could expect small payments, often in the form of food and drink consumed on the spot. Corvée sometimes included military conscription, and the term is also occasionally used in a slightly divergent sense to mean forced requisition of military supplies; this most often took the form of ''cartage'', a lord's right to demand wagons for military transport. Because agricultural corvée tended to be demanded by the lord at the same time that the peasants needed to tend their own plotse.g. at planting and harvestit was an object of serious resentment. By the 16th century its use in agricultural settings was on the decline and it became increasingly replaced by paid labour. It nevertheless persisted in many areas of Europe until the French Revolution and beyond.Austria, the Holy Roman Empire, and Germany

Corvée, specificallysocage

Socage () was one of the feudal duties and land tenure forms in the English feudal system. It eventually evolved into the freehold tenure called "free and common socage", which did not involve feudal duties. Farmers held land in exchange for ...

, was essential to the feudal system of the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy, also known as Habsburg Empire, or Habsburg Realm (), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities (composite monarchy) that were ruled by the House of Habsburg. From the 18th century it is ...

and later Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

, and most German states that belonged to the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

. Farmers and peasants were obliged to do hard agricultural work for their nobility, typically six months of the year. When a cash economy became established, the duty was gradually replaced by the duty to pay taxes.

After the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in History of Europe, European history. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine ...

, the demand for corvée grew too high and the system became dysfunctional. Its official decline is linked to the abolition of serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed du ...

by Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor

Joseph II (13 March 1741 – 20 February 1790) was Holy Roman Emperor from 18 August 1765 and sole ruler of the Habsburg monarchy from 29 November 1780 until his death. He was the eldest son of Empress Maria Theresa and her husband, Francis I, ...

and Habsburg ruler, in 1781. It continued to exist however, and was only abolished during the revolutions of 1848

The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespre ...

, along with the legal inequality between the nobility and common people.

Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; ; ) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. In a narrow, geographic sense, it roughly encompasses the territories of present-day Czechia that fall within the Elbe River's drainage basin, but historic ...

(or the Czech lands

The Czech lands or the Bohemian lands (, ) is a historical-geographical term which denotes the three historical regions of Bohemia, Moravia, and Czech Silesia out of which Czechoslovakia, and later the Czech Republic and Slovakia, were formed. ...

) was a part of the Holy Roman Empire as well as the Habsburg monarchy, and corvée was called in Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus

*Czech (surnam ...

. In Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

and other Slavic languages

The Slavic languages, also known as the Slavonic languages, are Indo-European languages spoken primarily by the Slavs, Slavic peoples and their descendants. They are thought to descend from a proto-language called Proto-Slavic language, Proto- ...

denotes any kind of work, but in Czech it specifically refers to unpaid unfree work, corvée or serf labour, or drudgery. The Czech word was imported to part of Germany where corvée was known as , and into Hungarian as . The word was later used by Czech writer Karel Čapek

Karel Čapek (; 9 January 1890 – 25 December 1938) was a Czech writer, playwright, critic and journalist. He has become best known for his science fiction, including his novel '' War with the Newts'' (1936) and play '' R.U.R.'' (''Rossum' ...

, who after a recommendation by his brother Josef Čapek introduced the word ''robot

A robot is a machine—especially one Computer program, programmable by a computer—capable of carrying out a complex series of actions Automation, automatically. A robot can be guided by an external control device, or the robot control, co ...

'' for (originally anthropomorphic) machines that do unpaid work for their owners in his 1920 play '' R.U.R.''

France

In France corvée existed until 4 August 1789, shortly after the beginning of the French Revolution, when it was abolished along with a number of other feudal privileges of the French landlords. At that time it was usually directed mainly towards improving the roads. It was greatly resented, and contributed to the widespread discontent that preceded the revolution. Counterrevolution revived corvée in France in 1824, 1836, and 1871, under the name . Every able-bodied man had to give three days' labour or its money equivalent in order to vote. It also continued to exist under the seigneurial system in what had beenNew France

New France (, ) was the territory colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Kingdom of Great Br ...

, in British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestown, ...

.

In 1866, during the French occupation of Mexico, the French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (, , ), is the principal Army, land warfare force of France, and the largest component of the French Armed Forces; it is responsible to the Government of France, alongside the French Navy, Fren ...

under Marshal François Achille Bazaine

François Achille Bazaine (13 February 181123 September 1888) was an officer of the French army. Rising from the ranks, during four decades of distinguished service (including 35 years on campaign) under Louis-Philippe I, Louis-Philippe and then ...

set up a corvée system to provide labour for public works instead of a system of fines.

Romanian principalities

In Romania, corvée was called .Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

described the corvée system of the Danubian Principalities

The Danubian Principalities (, ) was a conventional name given to the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, which emerged in the early 14th century. The term was coined in the Habsburg monarchy after the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774) ...

as a pre-capitalist form of compulsory over-work. The labour the peasants needed for their own maintenance was distinctly separate from the work they supplied to the landowner (the boyar

A boyar or bolyar was a member of the highest rank of the feudal nobility in many Eastern European states, including Bulgaria, Kievan Rus' (and later Russia), Moldavia and Wallachia (and later Romania), Lithuania and among Baltic Germans. C ...

, or in Romanian

Romanian may refer to:

*anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Romania

**Romanians, an ethnic group

**Romanian language, a Romance language

***Romanian dialects, variants of the Romanian language

**Romanian cuisine, traditional ...

) as surplus labour

Surplus labor () is a concept used by Karl Marx in his critique of political economy. It means labor performed in excess of the labor necessary to produce the means of livelihood of the worker ("necessary labor"). The "surplus" in this context mea ...

. The 14 days of labour due to the landowneras prescribed by the corvée code in the actually amounted to 42 days, because the working day was considered the time required for the production of an average daily product, "and that average daily product is determined in so crafty a way that no Cyclops

In Greek mythology and later Roman mythology, the Cyclopes ( ; , ''Kýklōpes'', "Circle-eyes" or "Round-eyes"; singular Cyclops ; , ''Kýklōps'') are giant one-eyed creatures. Three groups of Cyclopes can be distinguished. In Hesiod's ''Th ...

would be done with it in 24 hours." The corvée code was supposed to abolish serfdom, but did not achieve anything toward this goal.

A land reform

Land reform (also known as agrarian reform) involves the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership, land use, and land transfers. The reforms may be initiated by governments, by interested groups, or by revolution.

Lan ...

took place in 1864, after the Danubian Principalities unified and formed the United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia

The United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia (), commonly called United Principalities or Wallachia and Moldavia, was the personal union of the Principality of Moldavia and the Principality of Wallachia. The union was formed on when Alexa ...

, which abolished corvée and turned the peasants into free proprietors. The former owners were promised compensation, which was to be paid from a fund the peasants had to contribute to for 15 years. Besides the annual fee, the peasants also had to pay for the newly owned land, although at a price below market value. These debts made many peasants return to a life of semi-serfdom.

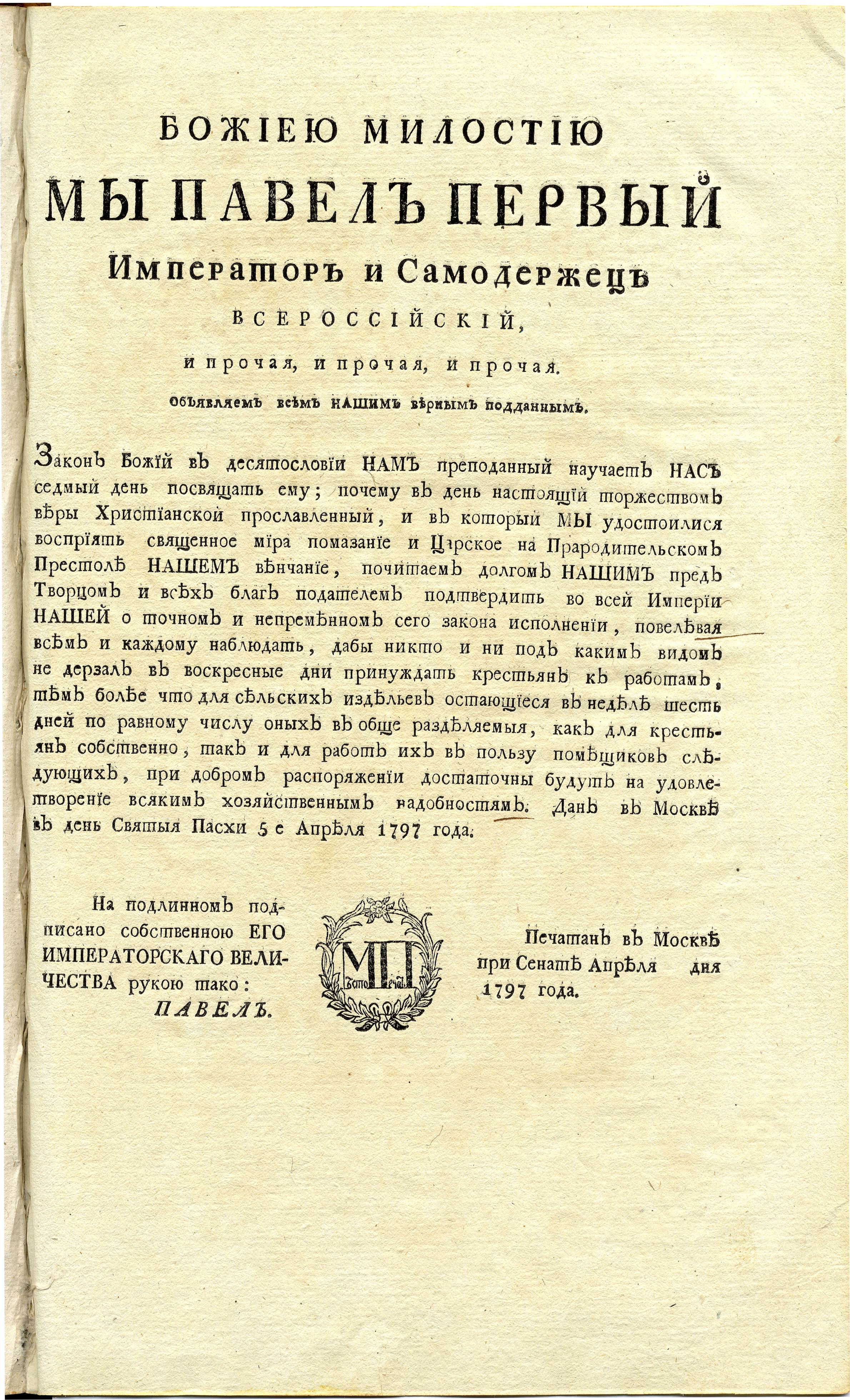

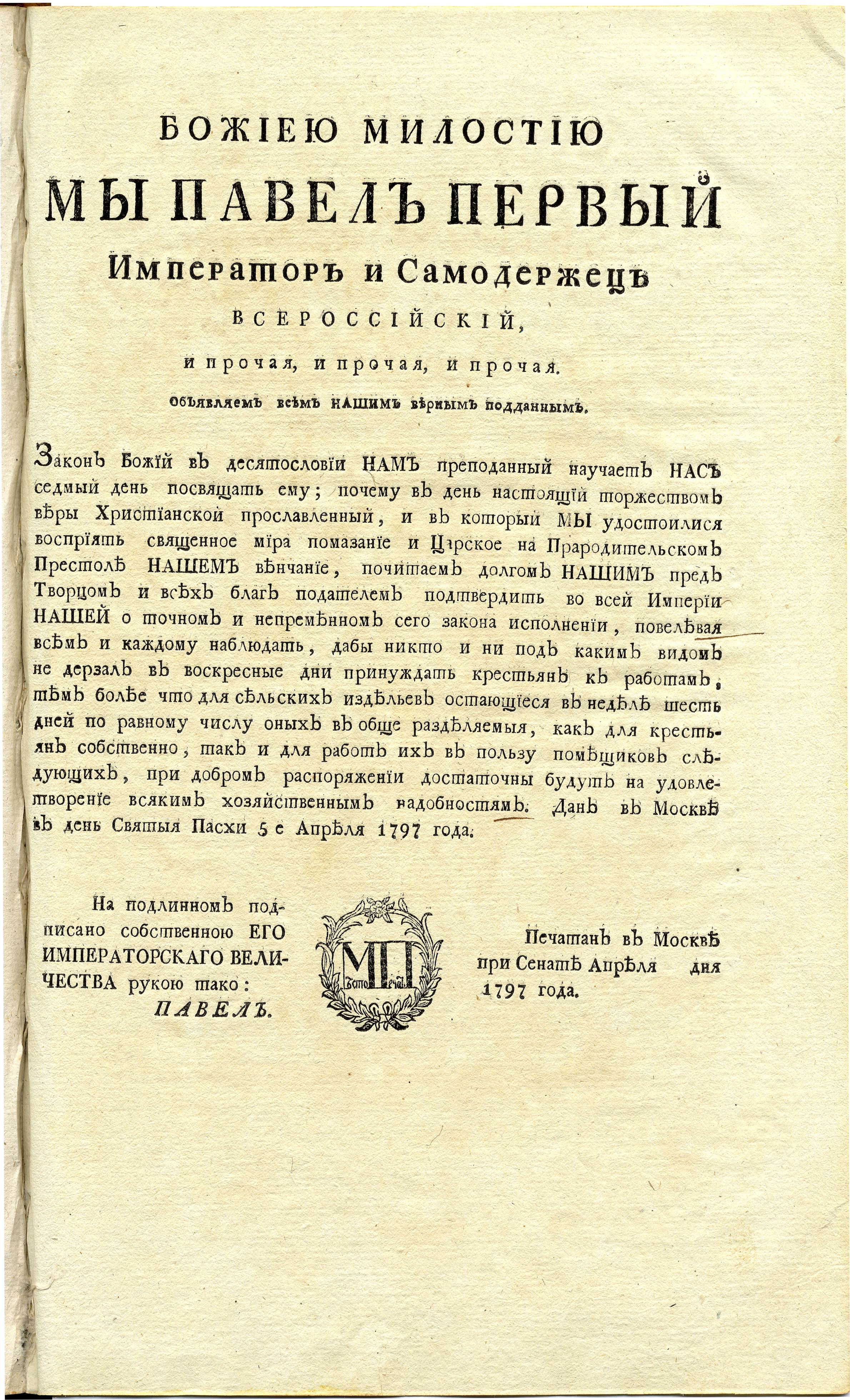

Russian Empire

In the Russian Tsardom and the

In the Russian Tsardom and the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

there were a number of permanent corvées called (), which included carriage corvée (), coachman corvée (), and lodging corvée (), among others.

In the context of Russian history, the term ''corvée'' is also sometimes used to translate the terms () or (), which refer to the obligatory work that the Russian serfs performed for the pomeshchik (Russian landed nobility

Landed nobility or landed aristocracy is a category of nobility in the history of various countries, for which landownership was part of their noble privileges. The landed nobility show noblesse oblige, they have duty to fulfill their social resp ...

) on their land. While no official government regulation on the duration of labour existed, a 1797 ukase

In Imperial Russia, a ukase () or ukaz ( ) was a proclamation of the tsar, government, or a religious leadership (e.g., Patriarch of Moscow and all Rus' or the Most Holy Synod) that had the force of law. " Edict" and " decree" are adequate trans ...

by Paul I of Russia

Paul I (; – ) was Emperor of Russia from 1796 until his assassination in 1801.

Paul remained overshadowed by his mother, Catherine the Great, for most of his life. He adopted the Pauline Laws, laws of succession to the Russian throne—rules ...

described a of three days a week as normal and sufficient for the landowner's needs.

In the Black Earth Region, 70% to 77% of the serfs performed and the rest paid levies ().

Haiti

The independent Kingdom of Haiti based atCap-Haïtien

Cap-Haïtien (; ; "Haitian Cape") is a List of communes of Haiti, commune of about 400,000 people on the north coast of Haiti and capital of the Departments of Haiti, department of Nord (Haitian department), Nord. Previously named ''Cap‑Fran� ...

under Henri Christophe

Henri Christophe (; 6 October 1767 – 8 October 1820) was a key leader in the Haitian Revolution and the only monarch of the Kingdom of Haiti.

Born in the British West Indies, British Caribbean, Christophe was possibly of Senegambian descent ...

imposed a corvée system upon the common citizenry which was used for massive fortifications to protect against French invasion. Plantation owners could pay the government and have labourers work for them instead. This enabled the Kingdom of Haiti to maintain a stronger economic structure than the Republic of Haiti

Haiti, officially the Republic of Haiti, is a country on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and south of the Bahamas. It occupies the western three-eighths of the island, which it shares with the Dominican ...

based in Port-au-Prince

Port-au-Prince ( ; ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Haiti, most populous city of Haiti. The city's population was estimated at 1,200,000 in 2022 with the metropolitan area estimated at a population of 2,618,894. The me ...

in the South under Alexandre Pétion

Alexandre Sabès Pétion (; 2 April 1770 – 29 March 1818) was the first president of the Republic of Haiti from 1807 until his death in 1818. One of Haiti's founding fathers, Pétion belonged to the revolutionary quartet that also includes ...

which had a system of agrarian reform distributing land to the labourers.

After deploying to Haiti in 1915 as an expression of the Roosevelt Corollary

In the history of United States foreign policy, the Roosevelt Corollary was an addition to the Monroe Doctrine articulated by President Theodore Roosevelt in his 1904 State of the Union Address, largely as a consequence of the Venezuelan cri ...

to the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine is a foreign policy of the United States, United States foreign policy position that opposes European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It holds that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign ...

, the U.S. Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. U.S. federal law names six armed forces: the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and the Coast Guard. Since 1949, all of the armed forces, except th ...

enforced a corvée system in the interest of making improvements to infrastructure.Paul Farmer, ''The Uses of Haiti'' (Common Courage Press: 1994)

Imperial China

Imperial China had a system of conscripting labour from the public, equated to theWestern

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

corvée system by many historians. Qin Shi Huang

Qin Shi Huang (, ; February 25912 July 210 BC), born Ying Zheng () or Zhao Zheng (), was the founder of the Qin dynasty and the first emperor of China. He is widely regarded as the first ever supreme leader of a unitary state, unitary d ...

, the first emperor, and following dynasties imposed it for public works like the Great Wall

The Great Wall of China (, literally "ten thousand Li (unit), ''li'' long wall") is a series of fortifications in China. They were built across the historical northern borders of ancient Chinese states and Imperial China as protection agains ...

, the Grand Canal, and the system of national roads and highways. However, as the imposition was exorbitant and punishment for failure draconian, Qin Shi Huang was resented by the people and criticized by many historians. Corvée labour was effectively abolished following the Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty, officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 1368 to 1644, following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming was the last imperial dynasty of ...

.

Inca Empire and modern Peru

TheInca Empire

The Inca Empire, officially known as the Realm of the Four Parts (, ), was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The administrative, political, and military center of the empire was in the city of Cusco. The History of the Incas, Inca ...

levied tribute labour through a system called ''Mit'a

Mit'a () was a system of mandatory labor service in the Inca Empire, as well as in Spain's empire in the Americas. Its close relative, the regionally mandatory Minka is still in use in Quechua communities today and known as in Spanish.

''Mit ...

'' which was perceived as a public service to the empire. At its height of efficiency, some subsistence farmers could be called to as many as 300 days of ''mit'a'' per year. The Spanish colonial rulers co-opted this system after the Spanish conquest of Peru

The Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire, also known as the Conquest of Peru, was one of the most important campaigns in the Spanish colonization of the Americas. After years of preliminary exploration and military skirmishes, 168 Spaniards, ...

to use natives as a source of forced labour

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, or violence, including death or other forms of ...

on ''encomiendas'' and in silver mines. The Incan system that focused on public works found a comeback during the 1960s government of Fernando Belaúnde Terry as a federal effort, with positive effects on Peruvian infrastructure.

Remnants of the system are still found today in modern Peru, such as the Mink'a

''Mink'a'', ''Minka'', ''Minga'' (from Quechua ''minccacuni'', meaning "asking for help by promising something") also ''mingaco'' is an Inca tradition of community work/voluntary collective labor for purposes of social utility and community infra ...

() communal work that is levied in Quechua communities in the Andes

The Andes ( ), Andes Mountains or Andean Mountain Range (; ) are the List of longest mountain chains on Earth, longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range ...

. An example is the campesino village of Ocra close to Cusco

Cusco or Cuzco (; or , ) is a city in southeastern Peru, near the Sacred Valley of the Andes mountain range and the Huatanay river. It is the capital of the eponymous Cusco Province, province and Cusco Region, department.

The city was the cap ...

, where each adult is required to perform four days of unpaid labour per month on community projects.

India

Corvée-style labour ( inSanskrit

Sanskrit (; stem form ; nominal singular , ,) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in northwest South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural ...

) existed in ancient India and lasted until the early 20th century. The practice is mentioned in the ''Mahabharata

The ''Mahābhārata'' ( ; , , ) is one of the two major Sanskrit Indian epic poetry, epics of ancient India revered as Smriti texts in Hinduism, the other being the ''Ramayana, Rāmāyaṇa''. It narrates the events and aftermath of the Kuru ...

'', where forced labourers are said to accompany the army. Manusmriti

The ''Manusmṛti'' (), also known as the ''Mānava-Dharmaśāstra'' or the Laws of Manu, is one of the many legal texts and constitutions among the many ' of Hinduism.

Over fifty manuscripts of the ''Manusmriti'' are now known, but the earli ...

says that mechanics and artisans should be made to work for the king one day a month; other writers advocated for one day of work every fortnight

A fortnight is a unit of time equal to 14 days (two weeks). The word derives from the Old English term , meaning "" (or "fourteen days", since the Anglo-Saxons counted by nights).

Astronomy and tides

In astronomy, a ''lunar fortnight'' is hal ...

(in all Indian lunar calendars, every month is divided into two fortnights, corresponding to the waxing and the waning moons). For poorer citizens, forced labour was seen as a way to pay their taxes since they could not pay ordinary taxes. Citizens, especially skilled workers, were sometimes made to both pay ordinary taxes and work for the state. If called to work, citizens could pay in cash or kind to discharge their obligations in some cases. In the Maurya

The Maurya Empire was a geographically extensive Iron Age historical power in South Asia with its power base in Magadha. Founded by Chandragupta Maurya around c. 320 BCE, it existed in loose-knit fashion until 185 BCE. The primary sourc ...

and post-Maurya time period, forced labour had become a regular source of income for the state. Written evidence shows rulers granting lands and villages with and without the right to forced labour from workers of those lands.

Japan

A corvée-style system called was found in pre-modern Japan. During the 1930s, it was common practice to import corvée labourers from both China andKorea

Korea is a peninsular region in East Asia consisting of the Korean Peninsula, Jeju Island, and smaller islands. Since the end of World War II in 1945, it has been politically Division of Korea, divided at or near the 38th parallel north, 3 ...

to work in coal mines. This practice continued until the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

Madagascar

France annexedMadagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

as a colony

A colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule, which rules the territory and its indigenous peoples separated from the foreign rulers, the colonizer, and their ''metropole'' (or "mother country"). This separated rule was often orga ...

in the late 19th century. Governor-General Joseph Gallieni

Joseph Simon Gallieni (24 April 1849 – 27 May 1916) was a French military officer, active for most of his career as a military commander and administrator in the French colonies where he wrote several books on colonial affairs.

He was rec ...

implemented a hybrid corvée and poll tax

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources. ''Poll'' is an archaic term for "head" or "top of the head". The sen ...

system, partly for revenue, partly for labour resources as the French had just abolished slavery there, and partly to move away from a subsistence economy

A subsistence economy is an economy directed to basic subsistence (the provision of food, clothing and shelter) rather than to the market.

Definition

"Subsistence" is understood as supporting oneself and family at a minimum level. Basic subsiste ...

. The latter involved paying small amounts for the forced labour. This was one attempt by the colonial administration at a solution to the economic tensions that arose under colonialism

Colonialism is the control of another territory, natural resources and people by a foreign group. Colonizers control the political and tribal power of the colonised territory. While frequently an Imperialism, imperialist project, colonialism c ...

. The problems were addressed in a way that was typical of colonialism which, along with the contemporary thinking behind it, is demonstrated in a 1938 work by Sonia E. Howe:

The Philippines

The system of forced labour otherwise known as evolved within the framework of the system, introduced into the South American colonies by the Spanish government. in theSpanish Philippines

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many countries in the Americas

**Spanish cuisine

** Spanish history

** Spanish cultur ...

refers to 40 days' forced manual labour for men from 16 to 60 years of age; these workers built community structures such as churches. Exemption from was possible via paying the (corruption of the Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many countries in the Americas

**Spanish cuisine

**Spanish history

**Spanish culture

...

, meaning 'absence'), which was a daily fine of one and a half reales. In 1884, the required amount of labour was reduced to 15 days. The system was patterned after the system for forced labour in Spanish America

Spanish America refers to the Spanish territories in the Americas during the Spanish colonization of the Americas. The term "Spanish America" was specifically used during the territories' Spanish Empire, imperial era between 15th and 19th centur ...

.

Portugal's African colonies

In Portuguese Africa (e.g.Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique, is a country located in Southeast Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west, and Eswatini and South Afr ...

), the Native Labour Regulations of 1899 stated that all able bodied men must work for six months of every year, and that " ey have full liberty to choose the means through which to comply with this regulation, but if they do not comply in some way, the public authorities will force them to comply."

Africans engaged in subsistence agriculture

Subsistence agriculture occurs when farmers grow crops on smallholdings to meet the needs of themselves and their families. Subsistence agriculturalists target farm output for survival and for mostly local requirements. Planting decisions occu ...

on their own small plots were considered unemployed. The forced labour was sometimes paid, but in cases of rule violations it was sometimes notas punishment. The state benefited from the use of the labour for farming and infrastructure, by high income taxes on those who found work with private employers, and by selling corvée labour to South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

. This system, called , was not abolished in Mozambique until 1962, and continued in some forms until the Carnation Revolution

The Carnation Revolution (), code-named Operation Historic Turn (), also known as the 25 April (), was a military coup by military officers that overthrew the Estado Novo government on 25 April 1974 in Portugal. The coup produced major socia ...

in 1974.

North America

Corvée was used in several states and provinces in North America especially for road maintenance, and this practice persisted to some degree in the United States and Canada. Its popularity with local governments gradually waned after theAmerican Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

with the increasing development of the monetary economy. After the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, some Southern states, with money in short supply, commuted taxing their inhabitants with obligations in the form of labour for public works, or let them pay a fee or tax to avoid it. The system proved unsuccessful because of the poor quality of work. In 1894, the Virginia Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of Virginia is the highest court in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It primarily hears direct appeals in civil cases from the trial-level city and county circuit courts, as well as the criminal law, family law and administrativ ...

ruled that corvée violated the state constitution, and in 1913 Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

became one of the last states to abolish it.

Modern instances

The government ofMyanmar

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and has ...

is well known for its use of the corvée and has defended the practice in its official newspapers.

In Bhutan

Bhutan, officially the Kingdom of Bhutan, is a landlocked country in South Asia, in the Eastern Himalayas between China to the north and northwest and India to the south and southeast. With a population of over 727,145 and a territory of , ...

, the ' calls for citizens to do work, such as dzong

Dzong architecture is used for dzongs, a distinctive type of fortified monastery (, , ) architectural style, architecture found mainly in Bhutan and Tibet. The architecture is massive in style with towering exterior walls surrounding a complex of ...

construction, in lieu of part of their tax obligation to the state.

In Rwanda

Rwanda, officially the Republic of Rwanda, is a landlocked country in the Great Rift Valley of East Africa, where the African Great Lakes region and Southeast Africa converge. Located a few degrees south of the Equator, Rwanda is bordered by ...

, the centuries-old tradition of '' umuganda'', or community labour, still continues, usually in the form of one Saturday a month when citizens are required to perform work.

Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

maintained corvée for females (ages 18–35) and males (ages 18–45) of 10 days yearly for public works at the discretion of the authorities. This was termed labour duty (). However, in 2006, the Standing Committee of the National Assembly

The National Assembly Standing Committee ( - UBTVQH), formerly organized as the Council of State (), is the highest standing body of the National Assembly of Vietnam, National Assembly (NA) of Vietnam. Its members are elected from among National A ...

voided the decree, effectively abolishing corvée in Vietnam.

The British overseas territory

The British Overseas Territories (BOTs) or alternatively referred to as the United Kingdom Overseas Territories (UKOTs) are the fourteen dependent territory, territories with a constitutional and historical link with the United Kingdom that, ...

of the Pitcairn Islands

The Pitcairn Islands ( ; Pitkern: '), officially Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie and Oeno Islands, are a group of four volcanic islands in the southern Pacific Ocean that form the sole British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the ...

, which has a population of about 50 and no income

Income is the consumption and saving opportunity gained by an entity within a specified timeframe, which is generally expressed in monetary terms. Income is difficult to define conceptually and the definition may be different across fields. F ...

or sales tax

A sales tax is a tax paid to a governing body for the sales of certain goods and services. Usually laws allow the seller to collect funds for the tax from the consumer at the point of purchase. When a tax on goods or services is paid to a govern ...

, has a system of public work whereby all able-bodied people are required to perform, when called upon, jobs such as road maintenance and repairs to public buildings.

Since the mid-late 19th century, most countries have restricted corvée labour to conscription

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it conti ...

(military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. Militaries are typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with their members identifiable by a d ...

or civilian service

Alternative civilian service, also called alternative services, civilian service, non-military service, and substitute service, is a form of national service performed in lieu of military conscription for various reasons, such as conscientious o ...

), or prison labour.

Gallery

See also

*Community service

Community service is unpaid work performed by a person or group of people for the benefit and betterment of their community contributing to a noble cause. In many cases, people doing community service are compensated in other ways, such as gettin ...

* Penal labor in the United States

Penal labor in the United States is the practice of using incarcerated individuals to perform various types of work, either for government-run or private industries. Inmates typically engage in tasks such as manufacturing goods, providing servic ...

* Alternative civilian service

Alternative civilian service, also called alternative services, civilian service, non-military service, and substitute service, is a form of national service performed in lieu of military conscription for various reasons, such as conscientious o ...

* Civil conscription

Civil conscription is the obligation of civilians to perform mandatory labour for the government. This kind of work has to correspond with the exceptions in international agreements, otherwise it could fall under the category of unfree labour. Th ...

* Compulsory Border Guard Service

* Compulsory Fire Service

* Hand and hitch-up services

* Impressment

Impressment, colloquially "the press" or the "press gang", is a type of conscription of people into a military force, especially a naval force, via intimidation and physical coercion, conducted by an organized group (hence "gang"). European nav ...

* Indenture

An indenture is a legal contract that reflects an agreement between two parties. Although the term is most familiarly used to refer to a labor contract between an employer and a laborer with an indentured servant status, historically indentures we ...

* Indigénat for instances of corvée in French colonial Africa

* Mit'a

Mit'a () was a system of mandatory labor service in the Inca Empire, as well as in Spain's empire in the Americas. Its close relative, the regionally mandatory Minka is still in use in Quechua communities today and known as in Spanish.

''Mit ...

* Nuribta (corvée letter to pharaoh)

* Serjeanty

Under feudalism in France and England during the Middle Ages, tenure by serjeanty () was a form of tenure in return for a specified duty other than standard knight-service.

Etymology

The word comes from the French noun , itself from the Latin ...

* Socage

Socage () was one of the feudal duties and land tenure forms in the English feudal system. It eventually evolved into the freehold tenure called "free and common socage", which did not involve feudal duties. Farmers held land in exchange for ...

* Subbotnik

Subbotnik and voskresnik (from rus, суббо́та, p=sʊˈbotə for "Saturday" and , for "Sunday") were days of volunteer unpaid work on weekends after the October Revolution, though the word itself is derived from (''subbota'' for Satur ...

* Tax farming

Farming or tax-farming is a technique of financial management in which the management of a variable revenue stream is assigned by legal contract to a third party and the holder of the revenue stream receives fixed periodic rents from the contr ...

* National Service

National service is a system of compulsory or voluntary government service, usually military service. Conscription is mandatory national service. The term ''national service'' comes from the United Kingdom's National Service (Armed Forces) Act ...

* Workfare

Workfare is a governmental plan under which welfare recipients are required to accept public-service jobs or to participate in job training. Many countries around the world have adopted workfare (sometimes implemented as "work-first" policies) t ...

References

Further reading

* See the chapter on "Corvées: valeur symbolique et poids économique" (5 articles on France, Germany, Italy, Spain and England), in: Bourin (Monique) ed., ''Pour une anthropologie du prélèvement seigneurial dans les campagnes médiévales (XIe–XIVe siècles): réalités et représentations paysannes'', Publications de la Sorbonne, 2004, p. 271–381. * ''The Rosetta Stone'' byE. A. Wallis Budge

Sir Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis Budge (27 July 185723 November 1934) was an English Egyptology, Egyptologist, Orientalism, Orientalist, and Philology, philologist who worked for the British Museum and published numerous works on the ancient ...

, (Dover Publications), c 1929, Dover edition (unabridged), c 1989.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Corvee

Forced labour

Feudal duties

Labor history