Cleopatra on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator (; The name Cleopatra is pronounced , or sometimes in both British and American English, see and respectively. Her name was pronounced in the Greek dialect of Egypt (see Koine Greek phonology). She was also styled as Thea Neotera () and Philopatris (); see 70/69 BC10 or 12 August 30 BC) was Queen of the

Ptolemaic

Ptolemaic

Gabinius was put on trial in Rome for abusing his authority, for which he was acquitted, but his second trial for accepting bribes led to his exile, from which he was recalled seven years later in 48 BC by Caesar. Crassus replaced him as governor of Syria and extended his provincial command to Egypt, but Crassus was killed by the Parthians at the

Gabinius was put on trial in Rome for abusing his authority, for which he was acquitted, but his second trial for accepting bribes led to his exile, from which he was recalled seven years later in 48 BC by Caesar. Crassus replaced him as governor of Syria and extended his provincial command to Egypt, but Crassus was killed by the Parthians at the

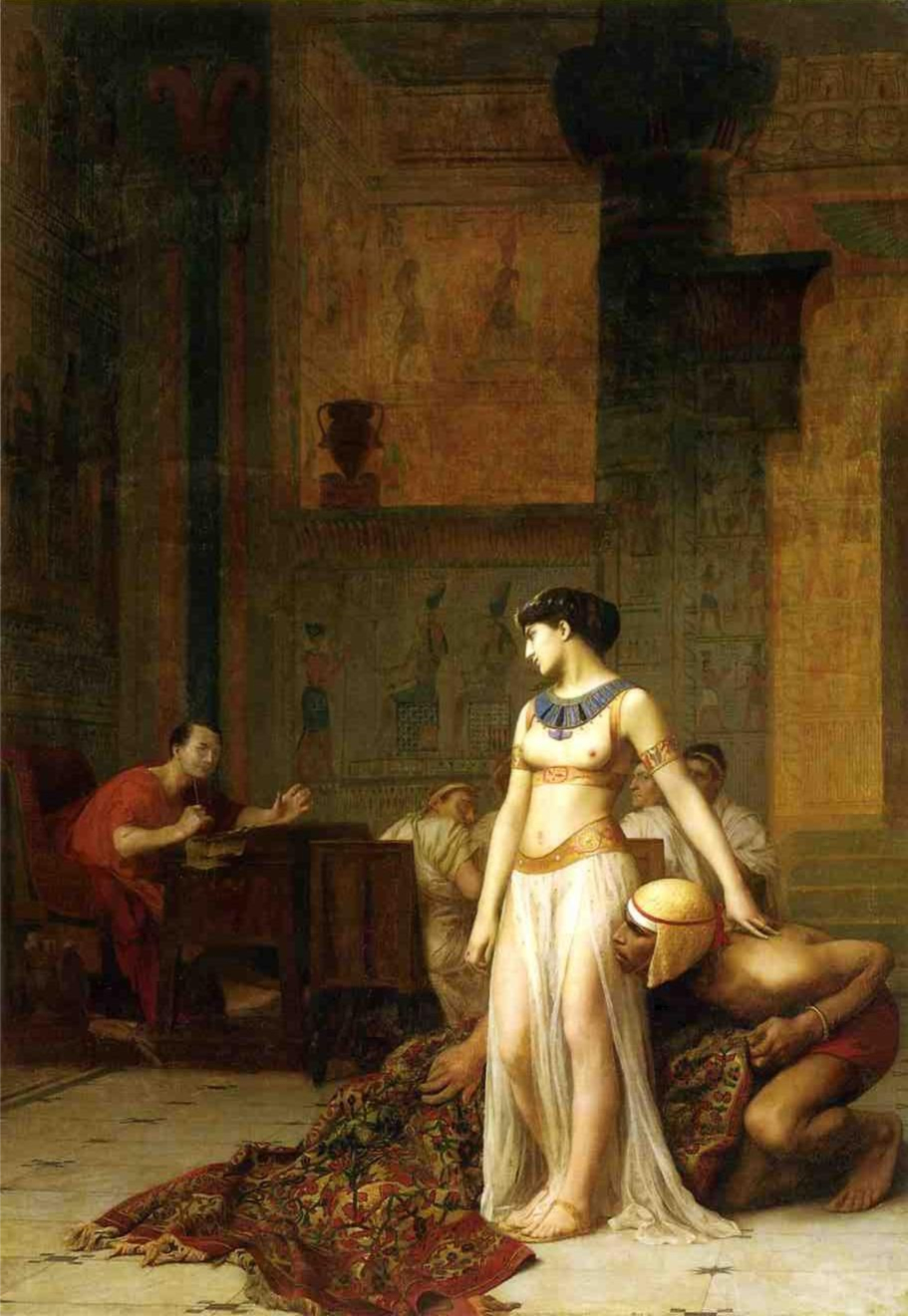

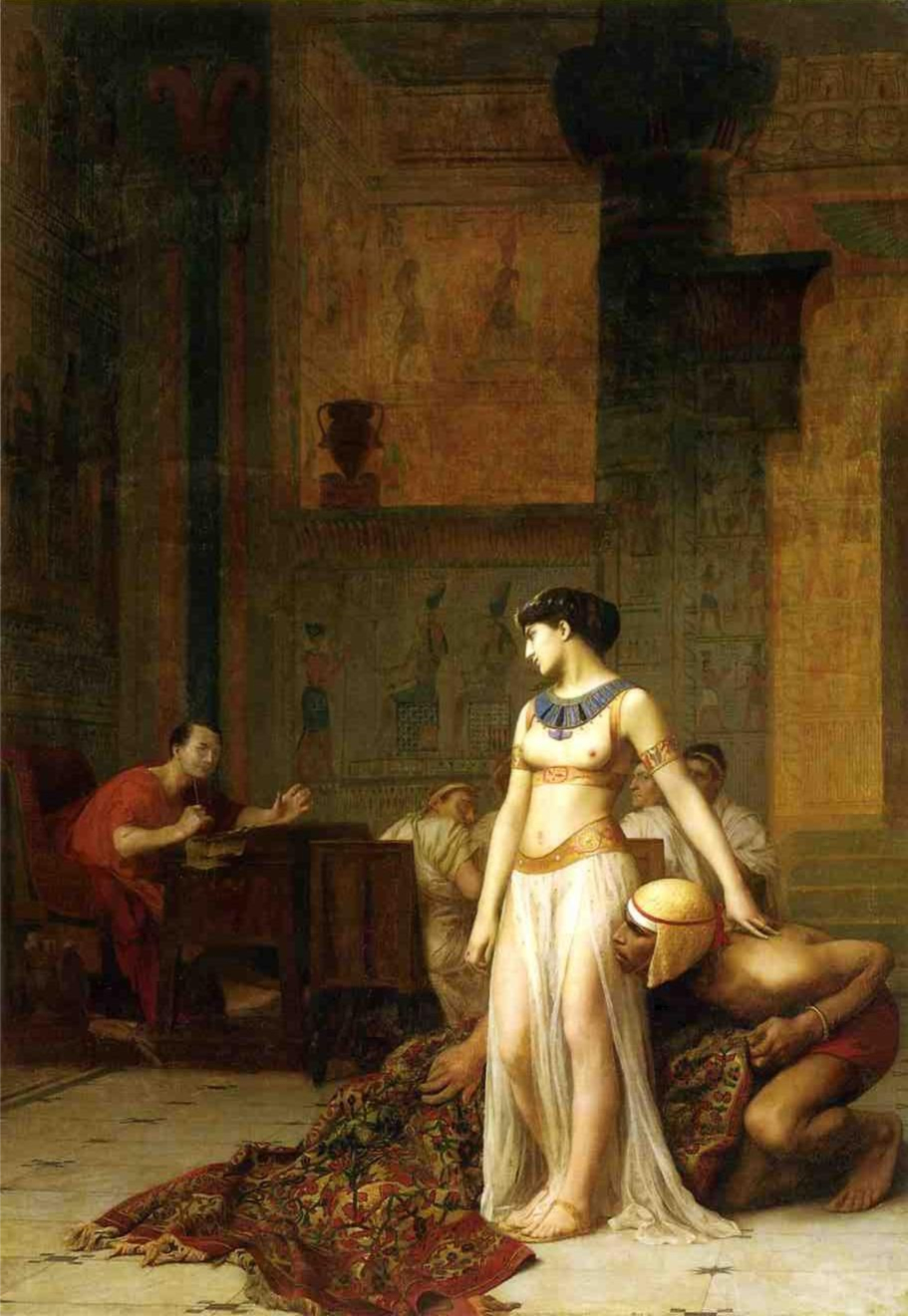

Ptolemy XIII arrived at Alexandria at the head of his army, in clear defiance of Caesar's demand that he disband and leave his army before his arrival. Cleopatra initially sent emissaries to Caesar, but upon allegedly hearing that Caesar was inclined to having affairs with royal women, she came to Alexandria to see him personally. Historian

Ptolemy XIII arrived at Alexandria at the head of his army, in clear defiance of Caesar's demand that he disband and leave his army before his arrival. Cleopatra initially sent emissaries to Caesar, but upon allegedly hearing that Caesar was inclined to having affairs with royal women, she came to Alexandria to see him personally. Historian

Octavian, Antony, and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus formed the

Octavian, Antony, and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus formed the

Mark Antony's Parthian campaign in the east was disrupted by the events of the

Mark Antony's Parthian campaign in the east was disrupted by the events of the  Antony's enlargement of the Ptolemaic realm by relinquishing directly controlled Roman territory was exploited by his rival Octavian, who tapped into the public sentiment in Rome against the empowerment of a foreign queen at the expense of their Republic. Octavian, fostering the narrative that Antony was neglecting his virtuous Roman wife Octavia, granted both her and

Antony's enlargement of the Ptolemaic realm by relinquishing directly controlled Roman territory was exploited by his rival Octavian, who tapped into the public sentiment in Rome against the empowerment of a foreign queen at the expense of their Republic. Octavian, fostering the narrative that Antony was neglecting his virtuous Roman wife Octavia, granted both her and

In an event held at the gymnasium soon after the triumph, Cleopatra dressed as Isis and declared that she was the Queen of Kings with her son Caesarion,

In an event held at the gymnasium soon after the triumph, Cleopatra dressed as Isis and declared that she was the Queen of Kings with her son Caesarion,

In a speech to the Roman Senate on the first day of his consulship on 1January 33 BC, Octavian accused Antony of attempting to subvert Roman freedoms and territorial integrity as a slave to his Oriental queen. Before Antony and Octavian's joint ''

In a speech to the Roman Senate on the first day of his consulship on 1January 33 BC, Octavian accused Antony of attempting to subvert Roman freedoms and territorial integrity as a slave to his Oriental queen. Before Antony and Octavian's joint '' During the spring of 32 BC Antony and Cleopatra traveled to Athens, where she persuaded Antony to send Octavia an official declaration of divorce. This encouraged Plancus to advise Octavian that he should seize Antony's will, invested with the

During the spring of 32 BC Antony and Cleopatra traveled to Athens, where she persuaded Antony to send Octavia an official declaration of divorce. This encouraged Plancus to advise Octavian that he should seize Antony's will, invested with the

Cleopatra had Caesarion enter into the ranks of the '' ephebi'', which, along with reliefs on a stele from Koptos dated 21 September 31 BC, demonstrated that Cleopatra was now grooming her son to become the sole ruler of Egypt. In a show of solidarity, Antony also had

Cleopatra had Caesarion enter into the ranks of the '' ephebi'', which, along with reliefs on a stele from Koptos dated 21 September 31 BC, demonstrated that Cleopatra was now grooming her son to become the sole ruler of Egypt. In a show of solidarity, Antony also had  Octavian entered Alexandria, occupied the palace, and seized Cleopatra's three youngest children. When she met with Octavian, Cleopatra told him bluntly, "I will not be led in a triumph" (), according to

Octavian entered Alexandria, occupied the palace, and seized Cleopatra's three youngest children. When she met with Octavian, Cleopatra told him bluntly, "I will not be led in a triumph" (), according to

I.21.129

. However, Duane W. Roller, relaying Theodore Cressy Skeat, affirms that Caesarion's reign "was essentially a fiction created by Egyptian chronographers to close the gap between leopatra'sdeath and official Roman control of Egypt" ().Plutarch, translated by , wrote in vague terms that "Octavian had Caesarion killed later, after Cleopatra's death." Octavian was convinced by the advice of the philosopher

Following the tradition of Macedonian rulers, Cleopatra ruled Egypt and other territories such as Cyprus as an absolute monarch, serving as the sole lawgiver of her kingdom. She was the chief religious authority in her realm, presiding over religious ceremonies dedicated to the deities of both the

Following the tradition of Macedonian rulers, Cleopatra ruled Egypt and other territories such as Cyprus as an absolute monarch, serving as the sole lawgiver of her kingdom. She was the chief religious authority in her realm, presiding over religious ceremonies dedicated to the deities of both the

Surviving coinage of Cleopatra's reign include specimens from every regnal year, from 51 to 30 BC. Cleopatra, the only Ptolemaic queen to issue coins on her own behalf, almost certainly inspired her partner Caesar to become the first living Roman to present his portrait on his own coins. writes the following: "Cleopatra was the only female Ptolemy to issue coins on her own behalf, some showing her as Venus-Aphrodite. Caesar now followed her example and, taking the same bold step, became the first living Roman to appear on coins, his rather haggard profile accompanied by the title 'Parens Patriae', 'Father of the Fatherland'." Cleopatra was the first foreign queen to have her image appear on

Surviving coinage of Cleopatra's reign include specimens from every regnal year, from 51 to 30 BC. Cleopatra, the only Ptolemaic queen to issue coins on her own behalf, almost certainly inspired her partner Caesar to become the first living Roman to present his portrait on his own coins. writes the following: "Cleopatra was the only female Ptolemy to issue coins on her own behalf, some showing her as Venus-Aphrodite. Caesar now followed her example and, taking the same bold step, became the first living Roman to appear on coins, his rather haggard profile accompanied by the title 'Parens Patriae', 'Father of the Fatherland'." Cleopatra was the first foreign queen to have her image appear on

File:Cleopatra VII, Marble, 40-30 BC, Vatican Museums 001.jpg, Cleopatra, mid-1st century BC, with a "melon" hairstyle and

The

The

The '' Bust of Cleopatra'' in the

The '' Bust of Cleopatra'' in the

File:Bust of Cleopatra at the Royal Ontario Museum.jpg, A granite Egyptian bust of Cleopatra from the

In modern times Cleopatra has become an icon of popular culture, a reputation shaped by theatrical representations dating back to the Renaissance as well as paintings and films. This material largely surpasses the scope and size of existent historiographic literature about her from classical antiquity and has made a greater impact on the general public's view of Cleopatra than the latter. The 14th-century English poet

In modern times Cleopatra has become an icon of popular culture, a reputation shaped by theatrical representations dating back to the Renaissance as well as paintings and films. This material largely surpasses the scope and size of existent historiographic literature about her from classical antiquity and has made a greater impact on the general public's view of Cleopatra than the latter. The 14th-century English poet

In Victorian Britain, Cleopatra was highly associated with many aspects of ancient Egyptian culture and her image was used to market various household products, including oil lamps,

In Victorian Britain, Cleopatra was highly associated with many aspects of ancient Egyptian culture and her image was used to market various household products, including oil lamps,

Print

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * . * * * * * * * * * * * . * * * * * * * * * * * * . * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Ancient Roman depictions of Cleopatra VII of Egypt

at YouTube * * , a Victorian children's book

"Mysterious Death of Cleopatra"

at the

Cleopatra VII

a

BBC History

Cleopatra VII

at

How History and Hollywood Got 'Cleopatra' Wrong

.

Cleopatra: Facts & Biography

. ''

The Timeline of the Life of Cleopatra

."

Cleopatra's Daughter: While Antony and Cleopatra have been immortalised in history and in popular culture, their offspring have been all but forgotten. Their daughter, Cleopatra Selene, became an important ruler in her own right

. ''

Ptolemaic Kingdom

The Ptolemaic Kingdom (; , ) or Ptolemaic Empire was an ancient Greek polity based in Ancient Egypt, Egypt during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 305 BC by the Ancient Macedonians, Macedonian Greek general Ptolemy I Soter, a Diadochi, ...

of Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

from 51 to 30 BC, and the last active Hellenistic

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

pharaoh.She was also a diplomat, naval commander, linguist, and medical author; see and . A member of the Ptolemaic dynasty

The Ptolemaic dynasty (; , ''Ptolemaioi''), also known as the Lagid dynasty (, ''Lagidai''; after Ptolemy I's father, Lagus), was a Macedonian Greek royal house which ruled the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Ancient Egypt during the Hellenistic period. ...

, she was a descendant of its founder Ptolemy I Soter

Ptolemy I Soter (; , ''Ptolemaîos Sōtḗr'', "Ptolemy the Savior"; 367 BC – January 282 BC) was a Macedonian Greek general, historian, and successor of Alexander the Great who went on to found the Ptolemaic Kingdom centered on Egypt. Pto ...

, a Macedonian Greek general and companion of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

. writes about Ptolemy I Soter

Ptolemy I Soter (; , ''Ptolemaîos Sōtḗr'', "Ptolemy the Savior"; 367 BC – January 282 BC) was a Macedonian Greek general, historian, and successor of Alexander the Great who went on to found the Ptolemaic Kingdom centered on Egypt. Pto ...

: "The Ptolemaic dynasty, of which Cleopatra was the last representative, was founded at the end of the fourth century BC. The Ptolemies were not of Egyptian extraction, but stemmed from Ptolemy Soter, a Macedonian Greek in the entourage of Alexander the Great."For additional sources that describe the Ptolemaic dynasty as " Macedonian Greek", please see , , , and . Alternatively, describes them as a "Macedonian, Greek-speaking" dynasty. Other sources such as and describe the Ptolemies as "Greco-Macedonian", or rather Macedonians who possessed a Greek culture, as in . Her first language was Koine Greek

Koine Greek (, ), also variously known as Hellenistic Greek, common Attic, the Alexandrian dialect, Biblical Greek, Septuagint Greek or New Testament Greek, was the koiné language, common supra-regional form of Greek language, Greek spoken and ...

, and she is the only Ptolemaic ruler known to have learned the Egyptian language

The Egyptian language, or Ancient Egyptian (; ), is an extinct branch of the Afro-Asiatic languages that was spoken in ancient Egypt. It is known today from a large corpus of surviving texts, which were made accessible to the modern world ...

, among several others. After her death, Egypt became a province of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

, marking the end of the Hellenistic period in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

, which had begun during the reign of Alexander (336–323 BC). notes that the Hellenistic period, beginning with the reign of Alexander the Great, came to an end with the death of Cleopatra in 30 BC. Michael Grant stresses that the Hellenistic Greeks were viewed by contemporary Romans as having declined and diminished in greatness since the age of Classical Greece

Classical Greece was a period of around 200 years (the 5th and 4th centuries BC) in ancient Greece,The "Classical Age" is "the modern designation of the period from about 500 B.C. to the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C." ( Thomas R. Mar ...

, an attitude that has continued even into the works of modern historiography

Historiography is the study of the methods used by historians in developing history as an academic discipline. By extension, the term ":wikt:historiography, historiography" is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiog ...

. Regarding Hellenistic Egypt, Grant argues, "Cleopatra VII, looking back upon all that her ancestors had done during that time, was not likely to make the same mistake. But she and her contemporaries of the first century BC had another, peculiar, problem of their own. Could the 'Hellenistic Age' (which we ourselves often regard as coming to an end in about her time) still be said to exist at all, could ''any'' Greek age, now that the Romans were the dominant power? This was a question never far from Cleopatra's mind. But it is quite certain that she considered the Greek epoch to be by no means finished, and intended to do everything in her power to ensure its perpetuation."

Born in Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, Cleopatra was the daughter of Ptolemy XII Auletes

Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysus ( – 51 BC) was a king of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Ancient Egypt, Egypt who ruled from 80 to 58 BC and then again from 55 BC until his death in 51 BC. He was commonly known as Auletes (, "the Flautist"), referring to ...

, who named her his heir before his death in 51 BC. Cleopatra began her reign alongside her brother Ptolemy XIII

Ptolemy XIII Theos Philopator (, ''Ptolemaĩos''; c. 62 BC – 13 January 47 BC) was Pharaoh of Egypt from 51 to 47 BC, and one of the last members of the Ptolemaic dynasty (305–30 BC). He was the son of Ptolemy XII and the brother of and co ...

, but falling-out between them led to a civil war. Roman statesman Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey ( ) or Pompey the Great, was a Roman general and statesman who was prominent in the last decades of the Roman Republic. ...

fled to Egypt after losing the 48 BC Battle of Pharsalus against his rival Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

, the Roman dictator

A Roman dictator was an extraordinary Roman magistrate, magistrate in the Roman Republic endowed with full authority to resolve some specific problem to which he had been assigned. He received the full powers of the state, subordinating the oth ...

, in Caesar's civil war

Caesar's civil war (49–45 BC) was a civil war during the late Roman Republic between two factions led by Julius Caesar and Pompey. The main cause of the war was political tensions relating to Caesar's place in the Republic on his expected ret ...

. Pompey had been a political ally of Ptolemy XII, but Ptolemy XIII had him ambushed and killed before Caesar arrived and occupied Alexandria. Caesar then attempted to reconcile the rival Ptolemaic siblings, but Ptolemy XIII's forces besieged Cleopatra and Caesar at the palace. Shortly after the siege was lifted by reinforcements, Ptolemy XIII died in the Battle of the Nile

The Battle of the Nile (also known as the Battle of Aboukir Bay; ) was fought between the Royal Navy and the French Navy at Abu Qir Bay, Aboukir Bay in Ottoman Egypt, Egypt between 1–3 August 1798. It was the climax of the Mediterranean ca ...

. Caesar declared Cleopatra and her brother Ptolemy XIV

Ptolemy XIV Philopator (, ; c. 59 – 44 BC) was a Pharaoh of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt, who reigned from 47 until his death in 44 BC.

Biography

Following the death of his older brother Ptolemy XIII of Egypt on January 13, 47 BC, and accor ...

joint rulers, and maintained a private affair with Cleopatra which produced a son, Caesarion

Ptolemy XV Caesar (; , ; 47 BC – late August 30 BC), nicknamed Caesarion (, , "Little Caesar"), was the last pharaoh of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt, reigning with his mother Cleopatra VII from 2 September 44 BC until her death by 10 or 12 ...

. Cleopatra traveled to Rome as a client queen in 46 and 44 BC, where she stayed at Caesar's villa

A villa is a type of house that was originally an ancient Roman upper class country house that provided an escape from urban life. Since its origins in the Roman villa, the idea and function of a villa have evolved considerably. After the f ...

. After Caesar's assassination, followed shortly afterwards by the sudden death of Ptolemy XIV (possibly murdered on Cleopatra's order), she named Caesarion co-ruler as Ptolemy XV.

In the Liberators' civil war

The Liberators' civil war (43–42 BC) was started by the Second Triumvirate to avenge Julius Caesar's assassination. The war was fought by the forces of Mark Antony and Octavian (the Second Triumvirate members, or ''Triumvirs'') against the fo ...

of 43–42 BC, Cleopatra sided with the Roman Second Triumvirate

The Second Triumvirate was an extraordinary commission and magistracy created at the end of the Roman republic for Mark Antony, Lepidus, and Octavian to give them practically absolute power. It was formally constituted by law on 27 November ...

formed by Caesar's heir Octavian

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in ...

, Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman people, Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the Crisis of the Roman Republic, transformation of the Roman Republic ...

, and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus. After their meeting at Tarsos in 41 BC, the queen had an affair with Antony which produced three children. Antony became increasingly reliant on Cleopatra for both funding and military aid during his invasions of the Parthian Empire

The Parthian Empire (), also known as the Arsacid Empire (), was a major Iranian political and cultural power centered in ancient Iran from 247 BC to 224 AD. Its latter name comes from its founder, Arsaces I, who led the Parni tribe ...

and the Kingdom of Armenia. The Donations of Alexandria

The Donations of Alexandria (autumn 34 BC) was a political act by Cleopatra VII and Mark Antony in which they distributed lands held by Rome and Parthia among Cleopatra's children and gave them many titles, especially for Caesarion, the son of ...

declared their children rulers over various territories under Antony's authority. Octavian portrayed this event as an act of treason, forced Antony's allies in the Roman Senate

The Roman Senate () was the highest and constituting assembly of ancient Rome and its aristocracy. With different powers throughout its existence it lasted from the first days of the city of Rome (traditionally founded in 753 BC) as the Sena ...

to flee Rome in 32 BC, and declared war on Cleopatra. After defeating Antony and Cleopatra's naval fleet at the 31 BC Battle of Actium

The Battle of Actium was a naval battle fought between Octavian's maritime fleet, led by Marcus Agrippa, and the combined fleets of both Mark Antony and Cleopatra. The battle took place on 2 September 31 BC in the Ionian Sea, near the former R ...

, Octavian's forces invaded Egypt in 30 BC and defeated Antony, leading to Antony's suicide. After his death, Cleopatra reportedly killed herself to avoid being publicly displayed by Octavian in Roman triumph

The Roman triumph (') was a civil ceremony and religious rite of ancient Rome, held to publicly celebrate and sanctify the success of a military commander who had led Roman forces to victory in the service of the state or, in some historical t ...

al procession, probably by poisoning.

Cleopatra's legacy survives in ancient and modern works of art. Roman historiography

During the Second Punic War with Carthage, Rome's earliest known annalists Quintus Fabius Pictor and Lucius Cincius Alimentus recorded history in Greek, and relied on Greek historians such as Timaeus. Roman histories were not written in Classi ...

and Latin poetry

The history of Latin poetry can be understood as the adaptation of Greek models. The verse comedies of Plautus, the earliest surviving examples of Latin literature, are estimated to have been composed around 205–184 BC.

History

Scholars conv ...

produced a generally critical view of the queen that pervaded later Medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

and Renaissance literature. In the visual arts, her ancient depictions include Roman busts, paintings

Painting is a visual art, which is characterized by the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called "matrix" or " support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with a brush. Other implements, ...

, and sculptures

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable sc ...

, cameo carvings and glass

Glass is an amorphous (non-crystalline solid, non-crystalline) solid. Because it is often transparency and translucency, transparent and chemically inert, glass has found widespread practical, technological, and decorative use in window pane ...

, Ptolemaic and Roman coinage

Roman currency for most of Roman history consisted of gold, silver, bronze, orichalcum and copper coinage. From its introduction during the Republic, in the third century BC, through Imperial times, Roman currency saw many changes in form, deno ...

, and relief

Relief is a sculpture, sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces remain attached to a solid background of the same material. The term ''wikt:relief, relief'' is from the Latin verb , to raise (). To create a sculpture in relief is to give ...

s. In Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

and Baroque art

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from the early 17th century until the 1750s. It followed Renaissance art and Mannerism and preceded the Rococo (in ...

, she was the subject of many works including operas, paintings, poetry, sculptures, and theatrical dramas. She has become a pop culture icon of Egyptomania since the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the reign of Queen Victoria, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. Slightly different definitions are sometimes used. The era followed the ...

, and in modern times, Cleopatra has appeared in the applied and fine arts, burlesque

A burlesque is a literary, dramatic or musical work intended to cause laughter by caricaturing the manner or spirit of serious works, or by ludicrous treatment of their subjects.

satire, Hollywood films, and brand images for commercial products.

Etymology

The Latinized formCleopatra

Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator (; The name Cleopatra is pronounced , or sometimes in both British and American English, see and respectively. Her name was pronounced in the Greek dialect of Egypt (see Koine Greek phonology). She was ...

comes from the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

(), meaning "glory of her father", from (, "glory") and (, "father"). The masculine form would have been written either as () or (). Cleopatra was the name of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

's sister Cleopatra of Macedonia

Cleopatra of Macedonia (Greek: Κλεοπάτρα της Μακεδονίας; 355/354 BC – 308 BC), or Cleopatra of Epirus (Greek: Κλεοπάτρα της Ηπείρου) was an ancient Macedonian princess and later queen regent of Epirus ...

, as well as the wife of Meleager

In Greek mythology, Meleager (, ) was a hero venerated in his '' temenos'' at Calydon in Aetolia. He was already famed as the host of the Calydonian boar hunt in the epic tradition that was reworked by Homer. Meleager is also mentioned as o ...

in Greek mythology

Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the Ancient Greece, ancient Greeks, and a genre of ancient Greek folklore, today absorbed alongside Roman mythology into the broader designation of classical mythology. These stories conc ...

, Cleopatra Alcyone. Through the marriage of Ptolemy V Epiphanes

Ptolemy V Epiphanes Eucharistus (, ''Ptolemaĩos Epiphanḗs Eukháristos'' "Ptolemy the Manifest, the Beneficent"; 9 October 210–September 180 BC) was the Pharaoh, King of Ptolemaic Egypt from July or August 204 BC until his death in 180 BC.

...

and Cleopatra I Syra (a Seleucid princess), the name entered the Ptolemaic dynasty

The Ptolemaic dynasty (; , ''Ptolemaioi''), also known as the Lagid dynasty (, ''Lagidai''; after Ptolemy I's father, Lagus), was a Macedonian Greek royal house which ruled the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Ancient Egypt during the Hellenistic period. ...

. Cleopatra's adopted title () means "goddess who loves her father". offers an alternative rendering of the title Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator as "Cleopatra the Father-Loving Goddess".

Background

Ptolemaic

Ptolemaic pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian language, Egyptian: ''wikt:pr ꜥꜣ, pr ꜥꜣ''; Meroitic language, Meroitic: 𐦲𐦤𐦧, ; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') was the title of the monarch of ancient Egypt from the First Dynasty of Egypt, First Dynasty ( ...

s were crowned by the Egyptian high priest of Ptah at Memphis, but resided in the multicultural and largely Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

city of Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, established by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

.For a thorough explanation about the foundation of Alexandria by Alexander the Great and its largely Hellenistic Greek

Koine Greek (, ), also variously known as Hellenistic Greek, common Attic, the Alexandrian dialect, Biblical Greek, Septuagint Greek or New Testament Greek, was the common supra-regional form of Greek spoken and written during the Hellenistic ...

nature during the Ptolemaic period, along with a survey of the various ethnic groups residing there, see .For further validation about the founding of Alexandria by Alexander the Great, see .For further validation of Ptolemaic rulers being crowned at Memphis, see . They spoke Greek and governed Egypt as Hellenistic

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

Greek monarchs, refusing to learn the native Egyptian language.The refusal of Ptolemaic rulers to speak the native language, Demotic Egyptian

Demotic (from ''dēmotikós'', 'popular') is the ancient Egyptian script derived from northern forms of hieratic used in the Nile Delta. The term was first used by the Greek historian Herodotus to distinguish it from hieratic and Egyptian hiero ...

, is why Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

(i.e. Koine Greek

Koine Greek (, ), also variously known as Hellenistic Greek, common Attic, the Alexandrian dialect, Biblical Greek, Septuagint Greek or New Testament Greek, was the koiné language, common supra-regional form of Greek language, Greek spoken and ...

) was used along with Late Egyptian on official court documents such as the Rosetta Stone

The Rosetta Stone is a stele of granodiorite inscribed with three versions of a Rosetta Stone decree, decree issued in 196 BC during the Ptolemaic dynasty of ancient Egypt, Egypt, on behalf of King Ptolemy V Epiphanes. The top and middle texts ...

().As explained by , Ptolemaic Alexandria was considered a ''polis

Polis (: poleis) means 'city' in Ancient Greek. The ancient word ''polis'' had socio-political connotations not possessed by modern usage. For example, Modern Greek πόλη (polē) is located within a (''khôra''), "country", which is a πατ ...

'' (city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world throughout history, including cities such as Rome, ...

) separate from the country of Egypt, with citizenship reserved for Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

and Ancient Macedonians

The Macedonians (, ) were an ancient tribe that lived on the alluvial plain around the rivers Haliacmon and lower Vardar, Axios in the northeastern part of Geography of Greece#Mainland, mainland Greece. Essentially an Ancient Greece, ancient ...

, but various other ethnic groups resided there, especially the Jews, as well as native Egyptians, Syrians, and Nubians

Nubians () ( Nobiin: ''Nobī,'' ) are a Nilo-Saharan speaking ethnic group indigenous to the region which is now northern Sudan and southern Egypt. They originate from the early inhabitants of the central Nile valley, believed to be one of th ...

.For further validation, see .For the multiple languages spoken by Cleopatra, see and .For further validation about Ancient Greek being the official language of the Ptolemaic dynasty, see . In contrast, Cleopatra could speak multiple languages by adulthood and was the first Ptolemaic ruler known to have learned the Egyptian language.For further information, see . Plutarch implies that she also spoke Ethiopian

Ethiopians are the native inhabitants of Ethiopia, as well as the global diaspora of Ethiopia. Ethiopians constitute several component ethnic groups, many of which are closely related to ethnic groups in neighboring Eritrea and other parts of ...

, the language of the " Troglodytes", Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

(or Aramaic

Aramaic (; ) is a Northwest Semitic language that originated in the ancient region of Syria and quickly spread to Mesopotamia, the southern Levant, Sinai, southeastern Anatolia, and Eastern Arabia, where it has been continually written a ...

), Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

, the "Syrian language" (perhaps Syriac), Median

The median of a set of numbers is the value separating the higher half from the lower half of a Sample (statistics), data sample, a statistical population, population, or a probability distribution. For a data set, it may be thought of as the “ ...

, and Parthian, and she could apparently also speak Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, although her Roman contemporaries would have preferred to speak with her in her native Koine Greek

Koine Greek (, ), also variously known as Hellenistic Greek, common Attic, the Alexandrian dialect, Biblical Greek, Septuagint Greek or New Testament Greek, was the koiné language, common supra-regional form of Greek language, Greek spoken and ...

.For the list of languages spoken by Cleopatra as mentioned by the ancient historian Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

, see , who also mentions that the rulers of Ptolemaic Egypt Ptolemaic is the adjective formed from the name Ptolemy, and may refer to:

Pertaining to the Ptolemaic dynasty

* Ptolemaic dynasty, the Macedonian Greek dynasty that ruled Egypt founded in 305 BC by Ptolemy I Soter

*Ptolemaic Kingdom

Pertaining ...

gradually abandoned the Ancient Macedonian language

Ancient Macedonian was the language of the ancient Macedonians which was either a Ancient Greek dialects, dialect of Ancient Greek or a separate Hellenic languages, Hellenic language. It was spoken in the kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), ...

. For further information and validation see . Aside from Greek, Egyptian, and Latin, these languages reflected Cleopatra's desire to restore North African and West Asian

West Asia (also called Western Asia or Southwest Asia) is the westernmost region of Asia. As defined by most academics, UN bodies and other institutions, the subregion consists of Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula, Iran, Mesopotamia, the Armenian ...

territories that once belonged to the Ptolemaic Kingdom

The Ptolemaic Kingdom (; , ) or Ptolemaic Empire was an ancient Greek polity based in Ancient Egypt, Egypt during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 305 BC by the Ancient Macedonians, Macedonian Greek general Ptolemy I Soter, a Diadochi, ...

.

Roman interventionism in Egypt predated the reign of Cleopatra

The reign of Cleopatra VII of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt began with the death of her father, Ptolemy XII Auletes, by March 51 BC. It ended with her suicide in August 30 BC, which also marked the conclusion of the Hellenistic period and ...

. When her grandfather Ptolemy IX Lathyros

Ptolemy IX Soter II Ptolemy IX also took the same title 'Soter' as Ptolemy I. In older references and in more recent references by the German historian Huss, Ptolemy IX may be numbered VIII. (, ''Ptolemaĩos Sōtḗr'' 'Ptolemy ...

died in late 81 BC, he was succeeded by his daughter Berenice III

Berenice III (Greek: Βερενίκη; 120–80 BC), also known as Cleopatra, ruled between 101 and 80 BC. Modern scholars studying Berenice III refer to her sometimes as Cleopatra Berenice. She was co-ruling queen of Ptolemaic Egypt with her ...

. With opposition building at the royal court against the idea of a sole reigning female monarch, Berenice III accepted joint rule and marriage with her cousin and stepson Ptolemy XI Alexander II, an arrangement made by the Roman dictator Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (, ; 138–78 BC), commonly known as Sulla, was a Roman people, Roman general and statesman of the late Roman Republic. A great commander and ruthless politician, Sulla used violence to advance his career and his co ...

. Ptolemy XI had his wife killed shortly after their marriage in 80 BC, and was lynched soon after in the resulting riot over the assassination. Ptolemy XI, and perhaps his uncle Ptolemy IX or father Ptolemy X Alexander I

Ptolemy X Alexander I (, ''Ptolemaĩos Aléxandros'') was the Ptolemaic king of Cyprus from 114 BC until 107 BC and of Egypt from 107 BC until his death in 88 BC. He ruled in co-regency with his mother Cleopatra III as Ptolemy Philometor Soter ...

, willed the Ptolemaic Kingdom to Rome as collateral for loans, giving the Romans legal grounds to take over Egypt, their client state

A client state in the context of international relations is a State (polity), state that is economically, politically, and militarily subordinated to a more powerful controlling state. Alternative terms for a ''client state'' are satellite state, ...

, after the assassination of Ptolemy XI. The Romans chose instead to divide the Ptolemaic realm among the illegitimate sons of Ptolemy IX, bestowing Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

on Ptolemy XII Auletes

Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysus ( – 51 BC) was a king of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Ancient Egypt, Egypt who ruled from 80 to 58 BC and then again from 55 BC until his death in 51 BC. He was commonly known as Auletes (, "the Flautist"), referring to ...

and Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

on another namesake son.

Biography

Early childhood

Cleopatra VII was born in early 69 BC to the ruling Ptolemaic pharaoh Ptolemy XII and an uncertain mother, states that Cleopatra could have been born in either late 70 BC or early 69 BC. presumably Ptolemy XII's wifeCleopatra V Tryphaena

Cleopatra V (; died ) was a Ptolemaic Queen of Egypt. She is the only surely attested wife of Ptolemy XII. Her only known child is Berenice IV, but she was also possibly the mother of Cleopatra VII. It is unclear if she died around the ti ...

(who may have been the same person as Cleopatra VI Tryphaena),For further information and validation see , , , , and . For alternate speculation, see and . For a comparison of arguments about Cleopatra's maternity, see . the mother of Cleopatra's older sister, Berenice IV Epiphaneia.Due to discrepancies in academic works, in which some consider Cleopatra VI to be either a daughter of Ptolemy XII or his wife, identical to that of Cleopatra V, states that Ptolemy XII had six children, while mentions only five. Cleopatra Tryphaena disappears from official records a few months after the birth of Cleopatra in 69 BC. The three younger children of Ptolemy XII, Cleopatra's sister Arsinoe IV and brothers Ptolemy XIII Theos Philopator

Ptolemy XIII Theos Philopator (, ''Ptolemaĩos''; c. 62 BC – 13 January 47 BC) was Pharaoh of Egypt from 51 to 47 BC, and one of the last members of the Ptolemaic dynasty (305–30 BC). He was the son of Ptolemy XII and the brother of and co ...

and Ptolemy XIV Philopator, were born in the absence of his wife. Cleopatra's childhood tutor was Philostratos, from whom she learned the Greek arts of oration and philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

. During her youth Cleopatra presumably studied at the Musaeum

The Mouseion of Alexandria (; ), which arguably included the Library of Alexandria, was an institution said to have been founded by Ptolemy I Soter and his son Ptolemy II Philadelphus. Originally, the word ''mouseion'' meant any place that w ...

, including the Library of Alexandria

The Great Library of Alexandria in Alexandria, Egypt, was one of the largest and most significant libraries of the ancient world. The library was part of a larger research institution called the Mouseion, which was dedicated to the Muses, ...

.

Reign and exile of Ptolemy XII

In 65 BC theRoman censor

The censor was a magistrate in ancient Rome who was responsible for maintaining the census, supervising public morality, and overseeing certain aspects of the government's finances.

Established under the Roman Republic, power of the censor was lim ...

Marcus Licinius Crassus

Marcus Licinius Crassus (; 115–53 BC) was a ancient Rome, Roman general and statesman who played a key role in the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire. He is often called "the richest man in Rome".Wallechinsky, Da ...

argued before the Roman Senate

The Roman Senate () was the highest and constituting assembly of ancient Rome and its aristocracy. With different powers throughout its existence it lasted from the first days of the city of Rome (traditionally founded in 753 BC) as the Sena ...

that Rome should annex Ptolemaic Egypt, but his proposed bill and the similar bill of tribune

Tribune () was the title of various elected officials in ancient Rome. The two most important were the Tribune of the Plebs, tribunes of the plebs and the military tribunes. For most of Roman history, a college of ten tribunes of the plebs ac ...

Servilius Rullus in 63 BC were rejected. Ptolemy XII responded to the threat of possible annexation by offering remuneration

Remuneration is the pay or other financial compensation provided in exchange for an employee's ''services performed'' (not to be confused with giving (away), or donating, or the act of providing to). Remuneration is one component of reward managem ...

and lavish gifts to powerful Roman statesmen, such as Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey ( ) or Pompey the Great, was a Roman general and statesman who was prominent in the last decades of the Roman Republic. ...

during his campaign against Mithridates VI of Pontus

Mithridates or Mithradates VI Eupator (; 135–63 BC) was the ruler of the Kingdom of Pontus in northern Anatolia from 120 to 63 BC, and one of the Roman Republic's most formidable and determined opponents. He was an effective, ambitious, and r ...

, and eventually Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

after he became Roman consul

The consuls were the highest elected public officials of the Roman Republic ( to 27 BC). Romans considered the consulship the second-highest level of the ''cursus honorum''an ascending sequence of public offices to which politicians aspire ...

in 59 BC.For further information and validation, see . In 1972, Michael Grant calculated that 6,000 talents, the price of Ptolemy XII's fee for receiving the title "friend and ally of the Roman people" from the triumvirs Pompey and Julius Caesar, would be worth roughly £7 million or US$17 million, roughly the entire annual tax revenue for Ptolemaic Egypt. However, Ptolemy XII's profligate behavior bankrupted him, and he was forced to acquire loans from the Roman banker Gaius Rabirius Postumus.

In 58 BC the Romans annexed Cyprus and on accusations of piracy drove Ptolemy of Cyprus, Ptolemy XII's brother, to commit suicide instead of enduring exile to Paphos

Paphos, also spelled as Pafos, is a coastal city in southwest Cyprus and the capital of Paphos District. In classical antiquity, two locations were called Paphos: #Old Paphos, Old Paphos, today known as Kouklia, and #New Paphos, New Paphos. It i ...

.For political background information on the Roman annexation of Cyprus, a move pushed for in the Roman Senate

The Roman Senate () was the highest and constituting assembly of ancient Rome and its aristocracy. With different powers throughout its existence it lasted from the first days of the city of Rome (traditionally founded in 753 BC) as the Sena ...

by Publius Clodius Pulcher

Publius Clodius Pulcher ( – 18 January 52 BC) was a Roman politician and demagogue. A noted opponent of Cicero, he was responsible during his plebeian tribunate in 58 BC for a massive expansion of the Roman grain dole as well as Cic ...

, see . Ptolemy XII remained publicly silent on the death of his brother, a decision which, along with ceding traditional Ptolemaic territory to the Romans, damaged his credibility among subjects already enraged by his economic policies. Ptolemy XII was then exiled from Egypt by force, traveling first to Rhodes

Rhodes (; ) is the largest of the Dodecanese islands of Greece and is their historical capital; it is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, ninth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Administratively, the island forms a separ ...

, then Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

, and finally the villa

A villa is a type of house that was originally an ancient Roman upper class country house that provided an escape from urban life. Since its origins in the Roman villa, the idea and function of a villa have evolved considerably. After the f ...

of triumvir

In the Roman Republic, or were commissions of three men appointed for specific tasks. There were many tasks that commissions could be established to conduct, such as administer justice, mint coins, support religious tasks, or found colonies.

M ...

Pompey in the Alban Hills, near Praeneste, Italy.For further information, see .

Ptolemy XII spent roughly up to a year there on the outskirts of Rome, ostensibly accompanied by his daughter Cleopatra, then about 11. expresses little doubt about this: "deposed in late summer 58 BC and fearing for his life, Auletes

An ''aulos'' (plural ''auloi''; , plural ) or ''Tibia (reedpipe), tibia'' (Latin) was a wind instrument in Music of ancient Greece, ancient Greece, often depicted in Ancient Greek art, art and also attested by classical archaeology, archaeolog ...

had fled both his palace and his kingdom, although he was not completely alone. For one Greek source reveals he had been accompanied 'by one of his daughters', and since his eldest Berenice IV, was monarch, and the youngest, Arsinoe, little more than a toddler, it is generally assumed that this must have been his middle daughter and favourite child, eleven-year-old Cleopatra." Berenice IV sent an embassy to Rome to advocate for her rule and oppose the reinstatement of her father. Ptolemy had assassins kill the leaders of the embassy, an incident that was covered up by his powerful Roman supporters.For further information, see . When the Roman Senate denied Ptolemy XII the offer of an armed escort and provisions for a return to Egypt, he decided to leave Rome in late 57 BC and reside at the Temple of Artemis

The Temple of Artemis or Artemision (; ), also known as the Temple of Diana, was a Greek temple dedicated to an ancient, localised form of the goddess Artemis (equated with the Religion in ancient Rome, Roman goddess Diana (mythology), Diana) ...

in Ephesus

Ephesus (; ; ; may ultimately derive from ) was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek city on the coast of Ionia, in present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in the 10th century BC on the site of Apasa, the former Arzawan capital ...

.

The Roman financiers of Ptolemy XII remained determined to restore him to power. Pompey persuaded Aulus Gabinius, the Roman governor of Syria, to invade Egypt and restore Ptolemy XII, offering him 10,000 talents for the proposed mission. Although it put him at odds with Roman law

Roman law is the law, legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (), to the (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor Justinian I.

Roman law also den ...

, Gabinius invaded Egypt in the spring of 55 BC by way of Hasmonean Judea, where Hyrcanus II

John Hyrcanus II (, ''Yohanan Hurqanos''; died 30 BCE), a member of the Hasmonean dynasty, was for a long time the Jewish High Priest in the 1st century BCE. He was also briefly King of Judea 67–66 BCE and then the ethnarch (ruler) of J ...

had Antipater the Idumaean

Antipater I the Idumaean (113 or 114 BCE – 43 BCE) was the founder of the Herodian dynasty and father of Herod the Great. According to Josephus, he was the son of Antipas and had formerly held that name. A native of Edom, Idumaea (a region sout ...

, father of Herod the Great

Herod I or Herod the Great () was a History of the Jews in the Roman Empire, Roman Jewish client king of the Herodian kingdom of Judea. He is known for his colossal building projects throughout Judea. Among these works are the rebuilding of the ...

, furnish the Roman-led army with supplies. As a young cavalry officer, Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman people, Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the Crisis of the Roman Republic, transformation of the Roman Republic ...

was under Gabinius's command. He distinguished himself by preventing Ptolemy XII from massacring the inhabitants of Pelousion, and for rescuing the body of Archelaos, the husband of Berenice IV, after he was killed in battle, ensuring him a proper royal burial. Cleopatra, then 14 years of age, would have traveled with the Roman expedition into Egypt; years later, Antony would profess that he had fallen in love with her at this time.

Battle of Carrhae

The Battle of Carrhae () was fought in 53 BC between the Roman Republic and the Parthian Empire near the ancient town of Carrhae (present-day Harran, Turkey). An invading force of seven Roman legion, legions of Roman heavy infantry under Marcus ...

in 53 BC. Ptolemy XII had Berenice IV and her wealthy supporters executed, seizing their properties. He allowed Gabinius's largely Germanic and Gallic Roman garrison, the Gabiniani

The (in English: Gabinians) were 2000 Roman legionaries and 500 cavalrymen stationed in Egypt by the Roman general Aulus Gabinius after he had reinstated the Pharaoh Ptolemy XII Auletes on the Egyptian throne in 55 BC. The soldiers were left ...

, to harass people in the streets of Alexandria and installed his longtime Roman financier Rabirius as his chief financial officer.For further information on Roman financier Rabirius, as well as the Gabiniani left in Egypt by Gabinius, see .

Within a year Rabirius was placed under protective custody and sent back to Rome after his life was endangered for draining Egypt of its resources.For further information, see . Despite these problems, Ptolemy XII created a will designating Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII as his joint heirs, oversaw major construction projects such as the Temple of Edfu and a temple at Dendera, and stabilized the economy.For further information, see . On 31 May 52 BC, Cleopatra was made a regent to Ptolemy XII, as indicated by an inscription in the Temple of Hathor at Dendera.Papyri of 51 BC were dated as the "thirtieth year of Auletes which is the first year of Cleopatra". See . Rabirius was unable to collect the entirety of Ptolemy XII's debt by the time of the latter's death, and so it was passed on to his successors Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII.

Reign

Accession to the throne

Ptolemy XII died sometime before 22 March 51 BC, when Cleopatra, in her first act as queen, began her voyage to Hermonthis, near Thebes, to install a new sacred Buchis bull, worshiped as an intermediary for the godMontu

Montu was a falcon-god of war in the ancient Egyptian religion, an embodiment of the conquering vitality of the pharaoh.Hart, George, ''A Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses'', Routledge, 1986, . p. 126. He was particularly worshipped in ...

in the Ancient Egyptian religion

Ancient Egyptian religion was a complex system of Polytheism, polytheistic beliefs and rituals that formed an integral part of ancient Egyptian culture. It centered on the Egyptians' interactions with Ancient Egyptian deities, many deities belie ...

.For further information, see and . states that the partial solar eclipse

A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between Earth and the Sun, thereby obscuring the view of the Sun from a small part of Earth, totally or partially. Such an alignment occurs approximately every six months, during the eclipse season i ...

of 7March 51 BC marked the death of Ptolemy XII and accession of Cleopatra to the throne, although she apparently suppressed the news of his death, alerting the Roman Senate to this fact months later in a message they received on 30 June 51 BC.However, claims that the Senate was informed of his death on 1August 51 BC. Michael Grant indicates that Ptolemy XII could have been alive as late as May, while an ancient Egyptian source affirms he was still ruling with Cleopatra by 15 July 51 BC, although by this point Cleopatra most likely "hushed up her father's death" so that she could consolidate her control of Egypt. Cleopatra faced several pressing issues and emergencies shortly after taking the throne. These included famine caused by drought and a low level of the annual flooding of the Nile

The flooding of the Nile (commonly referred to as ''the Inundation'') and its silt Deposition (geology), deposition was a natural cycle first attested in Ancient Egypt. It was of singular importance in the history and culture of Egypt. Governments ...

, and lawless behavior instigated by the Gabiniani

The (in English: Gabinians) were 2000 Roman legionaries and 500 cavalrymen stationed in Egypt by the Roman general Aulus Gabinius after he had reinstated the Pharaoh Ptolemy XII Auletes on the Egyptian throne in 55 BC. The soldiers were left ...

, the now unemployed and assimilated Roman soldiers left by Gabinius to garrison Egypt. Inheriting her father's debts, Cleopatra also owed the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

17.5 million drachma

Drachma may refer to:

* Ancient drachma, an ancient Greek currency

* Modern drachma

The drachma ( ) was the official currency of modern Greece from 1832 until the launch of the euro in 2001.

First modern drachma

The drachma was reintroduce ...

s.

In 50 BC Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus

Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus ( – 48 BC) was a politician of the Roman Republic. He was a conservative and upholder of the established social order who served in several magisterial positions alongside Julius Caesar and conceived a lifelong e ...

, proconsul

A proconsul was an official of ancient Rome who acted on behalf of a Roman consul, consul. A proconsul was typically a former consul. The term is also used in recent history for officials with delegated authority.

In the Roman Republic, military ...

of Syria, sent his two eldest sons to Egypt, most likely to negotiate with the Gabiniani and recruit them as soldiers in the desperate defense of Syria against the Parthians. The Gabiniani tortured and murdered these two, perhaps with secret encouragement by rogue senior administrators in Cleopatra's court. Cleopatra sent the Gabiniani culprits to Bibulus as prisoners awaiting his judgment, but he sent them back to Cleopatra and chastised her for interfering in their adjudication, which was the prerogative of the Roman Senate. Bibulus, siding with Pompey in Caesar's Civil War

Caesar's civil war (49–45 BC) was a civil war during the late Roman Republic between two factions led by Julius Caesar and Pompey. The main cause of the war was political tensions relating to Caesar's place in the Republic on his expected ret ...

, failed to prevent Caesar from landing a naval fleet in Greece, which ultimately allowed Caesar to reach Egypt in pursuit of Pompey.

By 29 August 51 BC, official documents started listing Cleopatra as the sole ruler, evidence that she had rejected her brother Ptolemy XIII as a co-ruler. She had probably married him, but there is no record of this. The Ptolemaic practice of sibling marriage

This article lists well-known individuals who had romantic or marital ties with their sibling(s) at any point in history. It does not include coupled siblings in works of fiction, although those from mythology and religion are included.

Termino ...

was introduced by Ptolemy II

Ptolemy II Philadelphus (, ''Ptolemaîos Philádelphos'', "Ptolemy, sibling-lover"; 309 – 28 January 246 BC) was the pharaoh of Ptolemaic Egypt from 284 to 246 BC. He was the son of Ptolemy I, the Macedonian Greek general of Alexander the G ...

and his sister Arsinoe II

Arsinoë II (, 316 BC – between 270 and 268 BC) was Queen consort of Thrace, Anatolia, and Macedonia by her first and second marriage, to king Lysimachus and king Ptolemy Keraunos respectively, and then Queen of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egy ...

. A long-held royal Egyptian practice, it was loathed by contemporary Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

. writes the following about the sibling marriage of Ptolemy II and Arsinoe II: "Ptolemy Keraunos

Ptolemy Ceraunus ( ; c. 319 BC – January/February 279 BC) was a member of the Ptolemaic dynasty and briefly king of Macedon. As the son of Ptolemy I Soter, he was originally heir to the throne of Ptolemaic Egypt, but he was displaced in fa ...

, who wanted to become king of Macedon

Macedonia ( ; , ), also called Macedon ( ), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, which later became the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by the royal ...

... killed Arsinoë's small children in front of her. Now queen without a kingdom, Arsinoë fled to Egypt, where she was welcomed by her full brother Ptolemy II. Not content, however, to spend the rest of her life as a guest at the Ptolemaic court, she had Ptolemy II's wife exiled to Upper Egypt and married him herself around 275 B.C. Though such an incestuous marriage was considered scandalous by the Greeks, it was allowed by Egyptian custom. For that reason, the marriage split public opinion into two factions. The loyal side celebrated the couple as a return of the divine marriage of Zeus

Zeus (, ) is the chief deity of the List of Greek deities, Greek pantheon. He is a sky father, sky and thunder god in ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, who rules as king of the gods on Mount Olympus.

Zeus is the child ...

and Hera

In ancient Greek religion, Hera (; ; in Ionic Greek, Ionic and Homeric Greek) is the goddess of marriage, women, and family, and the protector of women during childbirth. In Greek mythology, she is queen of the twelve Olympians and Mount Oly ...

, whereas the other side did not refrain from profuse and obscene criticism. One of the most sarcastic commentators, a poet with a very sharp pen, had to flee Alexandria. The unfortunate poet was caught off the shore of Crete by the Ptolemaic navy, put in an iron basket, and drowned. This and similar actions seemingly slowed down vicious criticism." By the reign of Cleopatra, however, it was considered a normal arrangement for Ptolemaic rulers.

Despite Cleopatra's rejection of him, Ptolemy XIII still retained powerful allies, notably the eunuch Potheinos, his childhood tutor, regent, and administrator of his properties. Others involved in the cabal against Cleopatra included Achillas, a prominent military commander, and Theodotus of Chios, another tutor of Ptolemy XIII. Cleopatra seems to have attempted a short-lived alliance with her brother Ptolemy XIV, but by the autumn of 50 BC Ptolemy XIII had the upper hand in their conflict and began signing documents with his name before that of his sister, followed by the establishment of his first regnal date in 49 BC.For further information, see .

Assassination of Pompey

In the summer of 49 BC, Cleopatra and her forces were still fighting against Ptolemy XIII within Alexandria when Pompey's son Gnaeus Pompeius arrived, seeking military aid on behalf of his father. After returning to Italy from the wars in Gaul andcrossing the Rubicon

The phrase "crossing the Rubicon" is an idiom that means "passing a point of no return". Its meaning comes from allusion to the crossing of the river Rubicon from the north by Julius Caesar in early January 49 BC. The exact date is unknown ...

in January of 49 BC, Caesar had forced Pompey and his supporters to flee to Greece. In perhaps their last joint decree, both Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII agreed to Gnaeus Pompeius's request and sent his father 60 ships and 500 troops, including the Gabiniani, a move that helped erase some of the debt owed to Rome. Losing the fight against her brother, Cleopatra was then forced to flee Alexandria and withdraw to the region of Thebes. By the spring of 48 BC Cleopatra had traveled to Roman Syria

Roman Syria was an early Roman province annexed to the Roman Republic in 64 BC by Pompey in the Third Mithridatic War following the defeat of King of Armenia Tigranes the Great, who had become the protector of the Hellenistic kingdom of Syria.

...

with her younger sister, Arsinoe IV, to gather an invasion force that would head to Egypt. She returned with an army, but her advance to Alexandria was blocked by her brother's forces, including some Gabiniani mobilized to fight against her, so she camped outside Pelousion in the eastern Nile Delta

The Nile Delta (, or simply , ) is the River delta, delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's larger deltas—from Alexandria in the west to Port Said in the eas ...

.

In Greece, Caesar and Pompey's forces engaged each other at the decisive Battle of Pharsalus on 9August 48 BC, leading to the destruction of most of Pompey's army and his forced flight to Tyre, Lebanon

Tyre (; ; ; ; ) is a city in Lebanon, and one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world. It was one of the earliest Phoenician metropolises and the legendary birthplace of Europa (cons ...

.For further information, see and . Given his close relationship with the Ptolemies, Pompey ultimately decided that Egypt would be his place of refuge, where he could replenish his forces.For further information, see . Ptolemy XIII's advisers, however, feared the idea of Pompey using Egypt as his base in a protracted Roman civil war. In a scheme devised by Theodotus, Pompey arrived by ship near Pelousion after being invited by a written message, only to be ambushed and stabbed to death on 28 September 48 BC.For further information, see and . Ptolemy XIII believed he had demonstrated his power and simultaneously defused the situation by having Pompey's head, severed and embalmed, sent to Caesar, who arrived in Alexandria by early October and took up residence at the royal palace. Caesar expressed grief and outrage over the killing of Pompey and called on both Ptolemy XIII and Cleopatra to disband their forces and reconcile with each other.For further information, see and .

Relationship with Julius Caesar

Ptolemy XIII arrived at Alexandria at the head of his army, in clear defiance of Caesar's demand that he disband and leave his army before his arrival. Cleopatra initially sent emissaries to Caesar, but upon allegedly hearing that Caesar was inclined to having affairs with royal women, she came to Alexandria to see him personally. Historian

Ptolemy XIII arrived at Alexandria at the head of his army, in clear defiance of Caesar's demand that he disband and leave his army before his arrival. Cleopatra initially sent emissaries to Caesar, but upon allegedly hearing that Caesar was inclined to having affairs with royal women, she came to Alexandria to see him personally. Historian Cassius Dio

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history of ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

records that she did so without informing her brother, dressed in an attractive manner, and charmed Caesar with her wit. Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

provides an entirely different account that alleges she was bound inside a bed sack to be smuggled into the palace to meet Caesar.For further information, see and .

When Ptolemy XIII realized that his sister was in the palace consorting directly with Caesar, he attempted to rouse the populace of Alexandria into a riot, but he was arrested by Caesar, who used his oratorical skills to calm the frenzied crowd. Caesar then brought Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII before the assembly of Alexandria, where Caesar revealed the written will of Ptolemy XII—previously possessed by Pompey—naming Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII as his joint heirs.For further information, see . Caesar then attempted to arrange for the other two siblings, Arsinoe IV and Ptolemy XIV, to rule together over Cyprus, thus removing potential rival claimants to the Egyptian throne while also appeasing the Ptolemaic subjects still bitter over the loss of Cyprus to the Romans in 58 BC.

Judging that this agreement favored Cleopatra over Ptolemy XIII and that the latter's army of 20,000, including the Gabiniani, could most likely defeat Caesar's army of 4,000 unsupported troops, Potheinos decided to have Achillas lead their forces to Alexandria to attack both Caesar and Cleopatra.For further information, see . After Caesar managed to execute Potheinos, Arsinoe IV joined forces with Achillas and was declared queen, but soon afterward had her tutor Ganymedes kill Achillas and take his position as commander of her army.For further information, see . Ganymedes then tricked Caesar into requesting the presence of the erstwhile captive Ptolemy XIII as a negotiator, only to have him join the army of Arsinoe IV. The resulting siege of the palace, with Caesar and Cleopatra trapped together inside, lasted into the following year of 47 BC.For further information, see and .

Sometime between January and March of 47 BC, Caesar's reinforcements arrived, including those led by Mithridates of Pergamon and Antipater the Idumaean

Antipater I the Idumaean (113 or 114 BCE – 43 BCE) was the founder of the Herodian dynasty and father of Herod the Great. According to Josephus, he was the son of Antipas and had formerly held that name. A native of Edom, Idumaea (a region sout ...

.For further information, see .As part of the siege of Alexandria, states that Caesar's reinforcements came in January, but says that his reinforcements came in March. Ptolemy XIII and Arsinoe IV withdrew their forces to the Nile

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the List of river sy ...

, where Caesar attacked them. Ptolemy XIII tried to flee by boat, but it capsized, and he drowned.For further information and validation, see and . Ganymedes may have been killed in the battle. Theodotus was found years later in Asia, by Marcus Junius Brutus

Marcus Junius Brutus (; ; 85 BC – 23 October 42 BC) was a Roman politician, orator, and the most famous of the assassins of Julius Caesar. After being adopted by a relative, he used the name Quintus Servilius Caepio Brutus, which was reta ...

, and executed. Arsinoe IV was forcefully paraded in Caesar's triumph in Rome before being exiled to the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus. Cleopatra was conspicuously absent from these events and resided in the palace, most likely because she had been pregnant with Caesar's child since September 48 BC.

Caesar's term as consul had expired at the end of 48 BC. However, Antony, an officer of his, helped to secure Caesar's appointment as dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute Power (social and political), power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a polity. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to r ...

lasting for a year, until October 47 BC, providing Caesar with the legal authority to settle the dynastic dispute in Egypt. Wary of repeating the mistake of Cleopatra's sister Berenice IV in having a female monarch as sole ruler, Caesar appointed the 12-year-old Ptolemy XIV as joint ruler with the 22-year-old Cleopatra in a nominal sibling marriage, but Cleopatra continued living privately with Caesar.For further information and validation, see and . states that at this point (47 BC) Ptolemy XIV was 12 years old, while claims that he was still only 10 years of age. The exact date at which Cyprus was returned to her control is not known, although she had a governor there by 42 BC.

Caesar is alleged to have joined Cleopatra for a cruise of the Nile and sightseeing of Egyptian monuments, although this may be a romantic tale reflecting later well-to-do Roman proclivities and not a real historical event. The historian Suetonius

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus (), commonly referred to as Suetonius ( ; – after AD 122), was a Roman historian who wrote during the early Imperial era of the Roman Empire. His most important surviving work is ''De vita Caesarum'', common ...

provided considerable details about the voyage, including use of '' Thalamegos'', the pleasure barge constructed by Ptolemy IV, which during his reign measured in length and in height and was complete with dining rooms, state rooms, holy shrines, and promenades along its two decks, resembling a floating villa. Caesar could have had an interest in the Nile cruise owing to his fascination with geography; he was well-read in the works of Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (; ; – ) was an Ancient Greek polymath: a Greek mathematics, mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theory, music theorist. He was a man of learning, becoming the chief librarian at the Library of A ...

and Pytheas

Pytheas of Massalia (; Ancient Greek: Πυθέας ὁ Μασσαλιώτης ''Pythéās ho Massaliōtēs''; Latin: ''Pytheas Massiliensis''; born 350 BC, 320–306 BC) was a Greeks, Greek List of Graeco-Roman geographers, geographer, explo ...

, and perhaps wanted to discover the source of the river, but turned back before reaching Ethiopia.

Caesar departed from Egypt around April 47 BC, allegedly to confront Pharnaces II of Pontus, the son of Mithridates VI of Pontus, who was stirring up trouble for Rome in Anatolia. It is possible that Caesar, married to the prominent Roman woman Calpurnia, also wanted to avoid being seen together with Cleopatra when she had their son. He left three legions in Egypt, later increased to four, under the command of the freedman

A freedman or freedwoman is a person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, slaves were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their owners), emancipation (granted freedom as part of a larger group), or self- ...

Rufio, to secure Cleopatra's tenuous position, but also perhaps to keep her activities in check.

Caesarion

Ptolemy XV Caesar (; , ; 47 BC – late August 30 BC), nicknamed Caesarion (, , "Little Caesar"), was the last pharaoh of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt, reigning with his mother Cleopatra VII from 2 September 44 BC until her death by 10 or 12 ...

, Cleopatra's alleged child with Caesar, was born sometime in 47, possibly on 23 June 47 BC if stele

A stele ( ) or stela ( )The plural in English is sometimes stelai ( ) based on direct transliteration of the Greek, sometimes stelae or stelæ ( ) based on the inflection of Greek nouns in Latin, and sometimes anglicized to steles ( ) or stela ...

at the Serapeum of Saqqara

The Serapeum of Saqqara was the ancient Egyptian burial place for sacred bulls of the Apis cult at Memphis. It was believed that the bulls were incarnations of the god Ptah, which would become immortal after death as ''Osiris-Apis'', a name w ...

that mentions "King Caesar" refers to him.For further information and validation, see and ; for date being disputed, see . Perhaps owing to his still childless marriage with Calpurnia, Caesar remained publicly silent about Caesarion (but perhaps accepted his parentage in private). writes the following about Caesar and his parentage of Caesarion: "The matter of parentage became so tangled in the propaganda war between Antonius and Octavian in the late 30s B.C.—it was essential for one side to prove and the other to reject Caesar's role—that it is impossible today to determine Caesar's actual response. The extant information is almost contradictory: it was said that Caesar denied parentage in his will but acknowledged it privately and allowed the use of the name Caesarion. Caesar's associate C. Oppius even wrote a pamphlet proving that Caesarion was not Caesar's child, and C. Helvius Cinna—the poet who was killed by rioters after Antonius' funeral oration—was prepared in 44 B.C. to introduce legislation to allow Caesar to marry as many wives as he wished for the purpose of having children. Although much of this talk was generated after Caesar's death, it seems that he wished to be as quiet as possible about the child but had to contend with Cleopatra's repeated assertions." Cleopatra, on the other hand, made repeated official declarations about Caesarion's parentage, naming Caesar as the father.