Ceratomorpha on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Perissodactyla (, ), or odd-toed ungulates, is an order of

Perissodactyla (, ), or odd-toed ungulates, is an order of

The main axes of both the front and rear feet pass through the third toe, which is always the largest. The remaining toes have been reduced in size to varying degrees. Tapirs, which are adapted to walking on soft ground, have four toes on their fore feet and three on their hind feet. Living rhinos have three toes on both the front and hind feet. Modern equines possess only a single toe; however, their feet are equipped with hooves, which almost completely cover the toe. Rhinos and tapirs, by contrast, have hooves covering only the leading edge of the toes, with the bottom being soft.

The main axes of both the front and rear feet pass through the third toe, which is always the largest. The remaining toes have been reduced in size to varying degrees. Tapirs, which are adapted to walking on soft ground, have four toes on their fore feet and three on their hind feet. Living rhinos have three toes on both the front and hind feet. Modern equines possess only a single toe; however, their feet are equipped with hooves, which almost completely cover the toe. Rhinos and tapirs, by contrast, have hooves covering only the leading edge of the toes, with the bottom being soft.

Odd-toed ungulates have a long upper jaw with an extended

Odd-toed ungulates have a long upper jaw with an extended

Most extant perissodactyl species occupy a small fraction of their original range. Members of this group are now found only in Central and South America, eastern and southern Africa, and central, southern, and southeastern Asia. During the peak of odd-toed ungulate existence, from the

Most extant perissodactyl species occupy a small fraction of their original range. Members of this group are now found only in Central and South America, eastern and southern Africa, and central, southern, and southeastern Asia. During the peak of odd-toed ungulate existence, from the

Odd-toed ungulates are characterized by a long gestation period and a small litter size, usually delivering a single young. The gestation period is 330–500 days, being longest in rhinos. Newborn perissodactyls are

Odd-toed ungulates are characterized by a long gestation period and a small litter size, usually delivering a single young. The gestation period is 330–500 days, being longest in rhinos. Newborn perissodactyls are

There are many perissodactyl fossils of multivariant form. The major lines of development include the following groups:

*

There are many perissodactyl fossils of multivariant form. The major lines of development include the following groups:

* Brontotherioidea were among the earliest known large mammals, consisting of the families of Brontotheriidae (synonym Titanotheriidae), the most well-known representative being '' Megacerops'' and the more basal family Lambdotheriidae. They were generally characterized in their late phase by a bony horn at the transition from the nose to the frontal bone and flat molars suitable for chewing soft plant food. The Brontotheroidea, which were almost exclusively confined to North America and Asia, died out at the beginning of the Upper

Brontotherioidea were among the earliest known large mammals, consisting of the families of Brontotheriidae (synonym Titanotheriidae), the most well-known representative being '' Megacerops'' and the more basal family Lambdotheriidae. They were generally characterized in their late phase by a bony horn at the transition from the nose to the frontal bone and flat molars suitable for chewing soft plant food. The Brontotheroidea, which were almost exclusively confined to North America and Asia, died out at the beginning of the Upper

The Perissodactyla appeared relatively abruptly at the beginning of the Lower Paleocene about 63 million years ago, both in North America and Asia, in the form of phenacodontids and hyopsodontids. The oldest finds from an extant group originate among other sources, from '' Sifrhippus'', an ancestor of the horses from the Willswood lineup in northwestern

The Perissodactyla appeared relatively abruptly at the beginning of the Lower Paleocene about 63 million years ago, both in North America and Asia, in the form of phenacodontids and hyopsodontids. The oldest finds from an extant group originate among other sources, from '' Sifrhippus'', an ancestor of the horses from the Willswood lineup in northwestern

In 1758, in his seminal work ''Systema Naturae'',

In 1758, in his seminal work ''Systema Naturae'',

Perissodactyla (, ), or odd-toed ungulates, is an order of

Perissodactyla (, ), or odd-toed ungulates, is an order of ungulates

Ungulates ( ) are members of the diverse clade Euungulata ("true ungulates"), which primarily consists of large mammals with hooves. Once part of the clade "Ungulata" along with the clade Paenungulata, "Ungulata" has since been determined to b ...

. The order includes about 17 living species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

divided into three families

Family (from ) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictability, structure, and safety as ...

: Equidae

Equidae (commonly known as the horse family) is the Taxonomy (biology), taxonomic Family (biology), family of Wild horse, horses and related animals, including Asinus, asses, zebra, zebras, and many extinct species known only from fossils. The fa ...

(horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 mi ...

s, asses, and zebra

Zebras (, ) (subgenus ''Hippotigris'') are African equines with distinctive black-and-white striped coats. There are three living species: Grévy's zebra (''Equus grevyi''), the plains zebra (''E. quagga''), and the mountain zebra (''E. ...

s), Rhinocerotidae (rhinoceros

A rhinoceros ( ; ; ; : rhinoceros or rhinoceroses), commonly abbreviated to rhino, is a member of any of the five extant taxon, extant species (or numerous extinct species) of odd-toed ungulates (perissodactyls) in the family (biology), famil ...

es), and Tapiridae (tapir

Tapirs ( ) are large, herbivorous mammals belonging to the family Tapiridae. They are similar in shape to a Suidae, pig, with a short, prehensile nose trunk (proboscis). Tapirs inhabit jungle and forest regions of South America, South and Centr ...

s). They typically have reduced the weight-bearing toes to three or one of the five original toes, though tapirs retain four toes on their front feet. The nonweight-bearing toes are either present, absent, vestigial

Vestigiality is the retention, during the process of evolution, of genetically determined structures or attributes that have lost some or all of the ancestral function in a given species. Assessment of the vestigiality must generally rely on co ...

, or positioned posteriorly. By contrast, artiodactyls

Artiodactyls are placental mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla ( , ). Typically, they are ungulates which bear weight equally on two (an even number) of their five toes (the third and fourth, often in the form of a hoof). The other thre ...

(even-toed ungulates) bear most of their weight equally on four or two (an even number) of the five toes: their third and fourth toes. Another difference between the two is that perissodactyls digest plant cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the chemical formula, formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of glycosidic bond, β(1→4) linked glucose, D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important s ...

in their intestines

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascular system. ...

, rather than in one or more stomach

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the upper gastrointestinal tract of Human, humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The Ancient Greek name for the stomach is ''gaster'' which is used as ''gastric'' in medical t ...

chambers as artiodactyls, with the exception of Suina

Suina (also known as Suiformes) is a suborder of omnivorous, non- ruminant artiodactyl mammals that includes the domestic pig and peccaries. A member of this clade is known as a suine. Suina includes the family Suidae, termed suids, known ...

, do.

The order was considerably more diverse in the past, with notable extinct groups including the brontotheres, palaeotheres, chalicotheres, and the paraceratheres, with the paraceratheres including the largest known land mammals to have ever existed.

Despite their very different appearances, they were recognized as related families in the 19th century by the zoologist Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

, who also coined the order's name.

Anatomy

The largest odd-toed ungulates are rhinoceroses, and the extinct ''Paraceratherium

''Paraceratherium'' is an extinct genus of hornless rhinocerotoids belonging to the family Paraceratheriidae. It is one of the largest terrestrial mammals that has ever existed and lived from the early to late Oligocene epoch (34–23 ...

'', a hornless rhino from the Oligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch (geology), epoch of the Paleogene Geologic time scale, Period that extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that defin ...

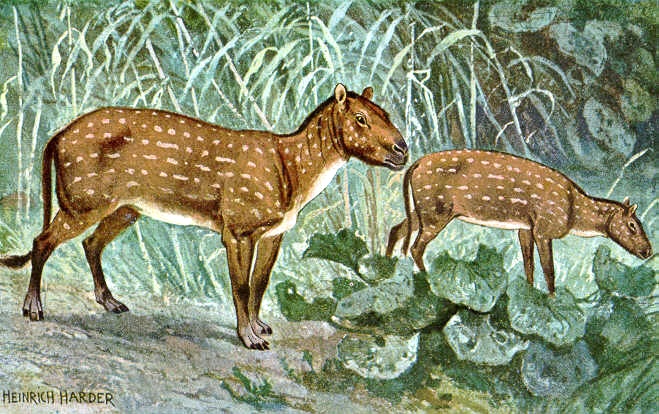

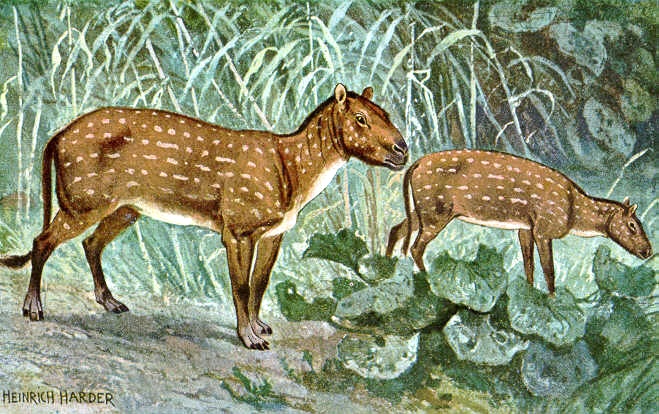

, is considered one of the largest land mammals of all time. At the other extreme, an early member of the order, the prehistoric horse ''Eohippus

''Eohippus'' is an extinct genus of small equid ungulates. The only species is ''E. angustidens'', which was long considered a species of ''Hyracotherium'' (now strictly defined as a member of the Palaeotheriidae rather than the Equidae). Its rem ...

'', had a withers height of only . Apart from dwarf varieties of the domestic horse and donkey, living perissodactyls reach a body length of and a weight of . While rhinos have only sparse hair and exhibit a thick epidermis

The epidermis is the outermost of the three layers that comprise the skin, the inner layers being the dermis and Subcutaneous tissue, hypodermis. The epidermal layer provides a barrier to infection from environmental pathogens and regulates the ...

, tapirs and horses have dense, short coats. Most species are grey or brown, although zebra

Zebras (, ) (subgenus ''Hippotigris'') are African equines with distinctive black-and-white striped coats. There are three living species: Grévy's zebra (''Equus grevyi''), the plains zebra (''E. quagga''), and the mountain zebra (''E. ...

s and young tapir

Tapirs ( ) are large, herbivorous mammals belonging to the family Tapiridae. They are similar in shape to a Suidae, pig, with a short, prehensile nose trunk (proboscis). Tapirs inhabit jungle and forest regions of South America, South and Centr ...

s are striped.

Limbs

The main axes of both the front and rear feet pass through the third toe, which is always the largest. The remaining toes have been reduced in size to varying degrees. Tapirs, which are adapted to walking on soft ground, have four toes on their fore feet and three on their hind feet. Living rhinos have three toes on both the front and hind feet. Modern equines possess only a single toe; however, their feet are equipped with hooves, which almost completely cover the toe. Rhinos and tapirs, by contrast, have hooves covering only the leading edge of the toes, with the bottom being soft.

The main axes of both the front and rear feet pass through the third toe, which is always the largest. The remaining toes have been reduced in size to varying degrees. Tapirs, which are adapted to walking on soft ground, have four toes on their fore feet and three on their hind feet. Living rhinos have three toes on both the front and hind feet. Modern equines possess only a single toe; however, their feet are equipped with hooves, which almost completely cover the toe. Rhinos and tapirs, by contrast, have hooves covering only the leading edge of the toes, with the bottom being soft.

Ungulate

Ungulates ( ) are members of the diverse clade Euungulata ("true ungulates"), which primarily consists of large mammals with Hoof, hooves. Once part of the clade "Ungulata" along with the clade Paenungulata, "Ungulata" has since been determined ...

s have stances that require them to stand on the tips of their toes. Equine

Equinae is a subfamily of the family Equidae, known from the Hemingfordian stage of the Early Miocene (16 million years ago) onwards. They originated in North America, before dispersing to every continent except Australia and Antarctica. They are ...

ungulates with only one digit or hoof have decreased mobility in their limbs, which allows for faster running speeds and agility.

Differences in limb structure and physiology between ungulate

Ungulates ( ) are members of the diverse clade Euungulata ("true ungulates"), which primarily consists of large mammals with Hoof, hooves. Once part of the clade "Ungulata" along with the clade Paenungulata, "Ungulata" has since been determined ...

s and other mammals can be seen in the shape of the humerus

The humerus (; : humeri) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius (bone), radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extrem ...

. For example, often shorter, thicker, bones belong to the largest and heaviest ungulates like the rhinoceros

A rhinoceros ( ; ; ; : rhinoceros or rhinoceroses), commonly abbreviated to rhino, is a member of any of the five extant taxon, extant species (or numerous extinct species) of odd-toed ungulates (perissodactyls) in the family (biology), famil ...

.

The ulna

The ulna or ulnar bone (: ulnae or ulnas) is a long bone in the forearm stretching from the elbow to the wrist. It is on the same side of the forearm as the little finger, running parallel to the Radius (bone), radius, the forearm's other long ...

e and fibula

The fibula (: fibulae or fibulas) or calf bone is a leg bone on the lateral side of the tibia, to which it is connected above and below. It is the smaller of the two bones and, in proportion to its length, the most slender of all the long bones. ...

e are reduced in horses. A common feature that clearly distinguishes this group from other mammals is the articulation between the astragalus

Astragalus may refer to:

* ''Astragalus'' (plant), a large genus of herbs and small shrubs

*Astragalus (bone)

The talus (; Latin for ankle or ankle bone; : tali), talus bone, astragalus (), or ankle bone is one of the group of foot bones known ...

, the scaphoid

The scaphoid bone is one of the carpal bones of the wrist. It is situated between the hand and forearm on the thumb side of the wrist (also called the lateral or radial side). It forms the radial border of the carpal tunnel. The scaphoid bone ...

and the cuboid

In geometry, a cuboid is a hexahedron with quadrilateral faces, meaning it is a polyhedron with six Face (geometry), faces; it has eight Vertex (geometry), vertices and twelve Edge (geometry), edges. A ''rectangular cuboid'' (sometimes also calle ...

, which greatly restricts the mobility of the foot. The thigh is relatively short, and the clavicle

The clavicle, collarbone, or keybone is a slender, S-shaped long bone approximately long that serves as a strut between the scapula, shoulder blade and the sternum (breastbone). There are two clavicles, one on each side of the body. The clavic ...

is absent.

Skull and teeth

diastema

A diastema (: diastemata, from Greek , 'space') is a space or gap between two teeth. Many species of mammals have diastemata as a normal feature, most commonly between the incisors and molars. More colloquially, the condition may be referred to ...

between the front and cheek teeth

A tooth (: teeth) is a hard, calcified structure found in the jaws (or mouths) of many vertebrates and used to break down food. Some animals, particularly carnivores and omnivores, also use teeth to help with capturing or wounding prey, tear ...

, giving them an elongated head. The various forms of snout between families are due to differences in the form of the premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammals h ...

. The lacrimal bone

The lacrimal bones are two small and fragile bones of the facial skeleton; they are roughly the size of the little fingernail and situated at the front part of the medial wall of the orbit. They each have two surfaces and four borders. Several bon ...

has projecting cusps in the eye sockets and a wide contact with the nasal bone. The temporomandibular joint

In anatomy, the temporomandibular joints (TMJ) are the two joints connecting the jawbone to the skull. It is a bilateral Synovial joint, synovial articulation between the temporal bone of the skull above and the condylar process of mandible be ...

is high and the mandible

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone i ...

is enlarged.

Rhinos have one or two horns made of agglutinated keratin

Keratin () is one of a family of structural fibrous proteins also known as ''scleroproteins''. It is the key structural material making up Scale (anatomy), scales, hair, Nail (anatomy), nails, feathers, horn (anatomy), horns, claws, Hoof, hoove ...

, unlike the horns of even-toed ungulate

Artiodactyls are placental mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla ( , ). Typically, they are ungulates which bear weight equally on two (an even number) of their five toes (the third and fourth, often in the form of a hoof). The other t ...

s (Bovidae

The Bovidae comprise the family (biology), biological family of cloven-hoofed, ruminant mammals that includes Bos, cattle, bison, Bubalina, buffalo, antelopes (including Caprinae, goat-antelopes), Ovis, sheep and Capra (genus), goats. A member o ...

and pronghorn

The pronghorn (, ) (''Antilocapra americana'') is a species of artiodactyl (even-toed, hoofed) mammal indigenous to interior western and central North America. Though not an antelope, it is known colloquially in North America as the American ante ...

), which have a bony core.

The number and form of the teeth vary according to diet. The incisor

Incisors (from Latin ''incidere'', "to cut") are the front teeth present in most mammals. They are located in the premaxilla above and on the mandible below. Humans have a total of eight (two on each side, top and bottom). Opossums have 18, wher ...

s and canines can be very small or completely absent, as in the two African species of rhinoceros. In horses, usually only the males possess canines. The surface shape and height of the molars

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat tooth, teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammal, mammals. They are used primarily to comminution, grind food during mastication, chewing. The name ''molar'' derives from Latin, '' ...

is heavily dependent on whether soft leaves or hard grass make up the main component of their diets. Three or four cheek teeth are present on each jaw half, so the dental formula

Dentition pertains to the development of teeth and their arrangement in the mouth. In particular, it is the characteristic arrangement, kind, and number of teeth in a given species at a given age. That is, the number, type, and morpho-physiology ...

of odd-toed ungulates is:

The guttural pouch, a small outpocketing of the auditory tube

The Eustachian tube (), also called the auditory tube or pharyngotympanic tube, is a tube that links the nasopharynx to the middle ear, of which it is also a part. In adult humans, the Eustachian tube is approximately long and in diameter. It ...

that drains the middle ear

The middle ear is the portion of the ear medial to the eardrum, and distal to the oval window of the cochlea (of the inner ear).

The mammalian middle ear contains three ossicles (malleus, incus, and stapes), which transfer the vibrations ...

, is a characteristic feature of Perissodactyla. The guttural pouch is of particular concern in equine

Equinae is a subfamily of the family Equidae, known from the Hemingfordian stage of the Early Miocene (16 million years ago) onwards. They originated in North America, before dispersing to every continent except Australia and Antarctica. They are ...

veterinary practice, due to its frequent involvement in some serious infections. Aspergillosis

Aspergillosis is a fungal infection of usually the lungs, caused by the genus ''Aspergillus'', a common mold that is breathed in frequently from the air, but does not usually affect most people. It generally occurs in people with lung diseases su ...

(infection with ''Aspergillus'' mould) of the guttural pouch (also called guttural pouch mycosis) can cause serious damage to the tissues of the pouch, as well as surrounding structures including important cranial nerves

Cranial nerves are the nerves that emerge directly from the brain (including the brainstem), of which there are conventionally considered twelve pairs. Cranial nerves relay information between the brain and parts of the body, primarily to and f ...

(nerves IX-XII: glossopharyngeal, vagus

The vagus nerve, also known as the tenth cranial nerve (CN X), plays a crucial role in the autonomic nervous system, which is responsible for regulating involuntary functions within the human body. This nerve carries both sensory and motor fiber ...

, accessory and hypoglossal nerves) and the internal carotid artery

The internal carotid artery is an artery in the neck which supplies the anterior cerebral artery, anterior and middle cerebral artery, middle cerebral circulation.

In human anatomy, the internal and external carotid artery, external carotid ari ...

. Strangles (''Streptococcus equi equi'' infection) is a highly transmissible respiratory infection of horses that can cause pus to accumulate in the guttural pouch; horses with ''S. equi equi'' colonising their guttural pouch can continue to intermittently shed the bacteria for several months, and should be isolated from other horses during this time to prevent transmission. Due to the intermittent nature of ''S. equi equi'' shedding, prematurely reintroducing an infected horse may risk exposing other horses to the infection, even though the shedding horse appears well and may have previously returned negative samples. The function of the guttural pouch has been difficult to determine, but it is now believed to play a role in cooling blood in the internal carotid artery before it enters the brain.

Gut

All perissodactyls are hindgut fermenters. In contrast toruminant

Ruminants are herbivorous grazing or browsing artiodactyls belonging to the suborder Ruminantia that are able to acquire nutrients from plant-based food by fermenting it in a specialized stomach prior to digestion, principally through microb ...

s, hindgut fermenters store digested food that has left the stomach

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the upper gastrointestinal tract of Human, humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The Ancient Greek name for the stomach is ''gaster'' which is used as ''gastric'' in medical t ...

in an enlarged cecum

The cecum ( caecum, ; plural ceca or caeca, ) is a pouch within the peritoneum that is considered to be the beginning of the large intestine. It is typically located on the right side of the body (the same side of the body as the appendix (a ...

, where the food begins digestion by microbes, with the fermentation continuing in the large colon. No gallbladder

In vertebrates, the gallbladder, also known as the cholecyst, is a small hollow Organ (anatomy), organ where bile is stored and concentrated before it is released into the small intestine. In humans, the pear-shaped gallbladder lies beneath t ...

is present. The stomach of perissodactyls is simply built, while the cecum accommodates up to in horses. The small intestine

The small intestine or small bowel is an organ (anatomy), organ in the human gastrointestinal tract, gastrointestinal tract where most of the #Absorption, absorption of nutrients from food takes place. It lies between the stomach and large intes ...

is very long, reaching up to in horses. Extraction of nutrients from food is relatively inefficient, which probably explains why no odd-toed ungulates are small; nutritional requirements per unit of body weight are lower for large animals, as their surface-area-to-volume ratio

The surface-area-to-volume ratio or surface-to-volume ratio (denoted as SA:V, SA/V, or sa/vol) is the ratio between surface area and volume of an object or collection of objects.

SA:V is an important concept in science and engineering. It is use ...

is smaller.

Lack of carotid rete

Unlike artiodactyls, perissodactyls lack a carotid rete, a heat exchange that reduces the dependence of the temperature of the brain on that of the body. As a result, perissodactyls have limited thermoregulatory flexibility compared to artiodactyls which has restricted them to habitats of low seasonality and rich in food and water, such as tropical forests. In contrast, artiodactyls occupy a wide range of habits ranging from the Arctic Circle to deserts and tropical savannahs.Distribution

Most extant perissodactyl species occupy a small fraction of their original range. Members of this group are now found only in Central and South America, eastern and southern Africa, and central, southern, and southeastern Asia. During the peak of odd-toed ungulate existence, from the

Most extant perissodactyl species occupy a small fraction of their original range. Members of this group are now found only in Central and South America, eastern and southern Africa, and central, southern, and southeastern Asia. During the peak of odd-toed ungulate existence, from the Eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (Ma). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes ...

to the Oligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch (geology), epoch of the Paleogene Geologic time scale, Period that extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that defin ...

, perissodactyls were distributed over much of the globe, the major exceptions being Australia and Antarctica. Horses and tapirs arrived in South America after the formation of the Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama, historically known as the Isthmus of Darien, is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North America, North and South America. The country of Panama is located on the i ...

around 3 million years ago in the Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch (geology), epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.33 to 2.58Baird's tapir

The Baird's tapir (''Tapirus bairdii''), also known as the Central American tapir, is a species of tapir native to Mexico, Central America, and northwestern South America. It is the largest of the three species of tapir native to the Americas, a ...

with a range extending to what is now southern Mexico. The tarpans were pushed to extinction in 19th century Europe. Hunting and habitat destruction

Habitat destruction (also termed habitat loss or habitat reduction) occurs when a natural habitat is no longer able to support its native species. The organisms once living there have either moved elsewhere, or are dead, leading to a decrease ...

have reduced the surviving perissodactyl species to fragmented populations. In contrast, domesticated horses and donkeys have gained a worldwide distribution, and feral animals of both species are now also found in regions outside their original range, such as in Australia.

Lifestyle and diet

Perissodactyls inhabit a number of different habitats, leading to different lifestyles. Tapirs are solitary and inhabit mainly tropical rainforests. Rhinos tend to live alone in rather dry savannas, and in Asia, wet marsh or forest areas. Horses inhabit open areas such as grasslands, steppes, or semi-deserts, and live together in groups. Odd-toed ungulates are exclusively herbivores that feed, to varying degrees, on grass, leaves, and other plant parts. A distinction is often made between primarily grass feeders ( white rhinos,equines

''Equus'' () is a genus of mammals in the perissodactyl family (biology), family Equidae, which includes wild horse, horses, Asinus, asses, and zebras. Within the Equidae, ''Equus'' is the only recognized Extant taxon, extant genus, comprising s ...

) and leaf feeders (tapirs, other rhinos).

Reproduction and development

Odd-toed ungulates are characterized by a long gestation period and a small litter size, usually delivering a single young. The gestation period is 330–500 days, being longest in rhinos. Newborn perissodactyls are

Odd-toed ungulates are characterized by a long gestation period and a small litter size, usually delivering a single young. The gestation period is 330–500 days, being longest in rhinos. Newborn perissodactyls are precocial

Precocial species in birds and mammals are those in which the young are relatively mature and mobile from the moment of birth or hatching. They are normally nidifugous, meaning that they leave the nest shortly after birth or hatching. Altricial ...

, meaning offspring are born already quite independent: for example, young horses can begin to follow the mother after a few hours. The young are nursed for a relatively long time, often into their second year, with rhinos reaching sexual maturity around eight or ten years old, but horses and tapirs maturing around two to four years old. Perissodactyls are long-lived, with several species, such as rhinos, reaching an age of almost 50 years in captivity.

Taxonomy

Outer taxonomy

Traditionally, the odd-toed ungulates were classified with other mammals such asartiodactyls

Artiodactyls are placental mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla ( , ). Typically, they are ungulates which bear weight equally on two (an even number) of their five toes (the third and fourth, often in the form of a hoof). The other thre ...

, hyrax

Hyraxes (), also called dassies, are small, stout, thickset, herbivorous mammals in the family Procaviidae within the order Hyracoidea. Hyraxes are well-furred, rotund animals with short tails. Modern hyraxes are typically between in length a ...

es, elephants

Elephants are the Largest and heaviest animals, largest living land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant (''Loxodonta africana''), the African forest elephant (''L. cyclotis''), and the Asian ele ...

and other "ungulates". A close family relationship with hyraxes was suspected based on similarities in the construction of the ear and the course of the carotid artery Carotid artery may refer to:

* Common carotid artery, often "carotids" or "carotid", an artery on each side of the neck which divides into the external carotid artery and internal carotid artery

* External carotid artery, an artery on each side of ...

.

Molecular genetic studies, however, have shown the ungulates to be polyphyletic

A polyphyletic group is an assemblage that includes organisms with mixed evolutionary origin but does not include their most recent common ancestor. The term is often applied to groups that share similar features known as Homoplasy, homoplasies ...

, meaning that in some cases the similarities are the result of convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last comm ...

rather than common ancestry

Common descent is a concept in evolutionary biology applicable when one species is the ancestor of two or more species later in time. According to modern evolutionary biology, all living beings could be descendants of a unique ancestor commonl ...

. Elephants and hyraxes are now considered to belong to Afrotheria

Afrotheria ( from Latin ''Afro-'' "of Africa" + ''theria'' "wild beast") is a superorder of placental mammals, the living members of which belong to groups that are either currently living in Africa or of African origin: golden moles, elephan ...

, so are not closely related to the perissodactyls. These in turn are in the Laurasiatheria

Laurasiatheria (; "Laurasian beasts") is a superorder of Placentalia, placental mammals that groups together true insectivores (eulipotyphlans), bats (chiropterans), carnivorans, pangolins (Pholidota, pholidotes), even-toed ungulates (Artiodacty ...

, a superorder that had its origin in the former supercontinent Laurasia

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around ( Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during the breakup of Pa ...

. Molecular genetic findings suggest that the cloven Artiodactyla

Artiodactyls are placental mammals belonging to the order (biology), order Artiodactyla ( , ). Typically, they are ungulates which bear weight equally on two (an even number) of their five toes (the third and fourth, often in the form of a hoof ...

(containing the cetacea

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively c ...

ns as a deeply nested subclade) are the sister taxon of the Perissodactyla; together, the two groups form the Euungulata

Ungulates ( ) are members of the diverse clade Euungulata ("true ungulates"), which primarily consists of large mammals with Hoof, hooves. Once part of the clade "Ungulata" along with the clade Paenungulata, "Ungulata" has since been determined ...

. More distant are the bat

Bats are flying mammals of the order Chiroptera (). With their forelimbs adapted as wings, they are the only mammals capable of true and sustained flight. Bats are more agile in flight than most birds, flying with their very long spread-out ...

s (Chiroptera) and Ferae

Ferae ( , , "wild beasts") is a mirorder of Placentalia, placental mammals in grandorder Ferungulata, that groups together clades Pan-Carnivora (that includes carnivorans and their fossil relatives) and Pholidotamorpha (pangolins and their fossi ...

(a common taxon of carnivorans, Carnivora

Carnivora ( ) is an order of placental mammals specialized primarily in eating flesh, whose members are formally referred to as carnivorans. The order Carnivora is the sixth largest order of mammals, comprising at least 279 species. Carnivor ...

, and pangolins, Pholidota

Pangolins, sometimes known as scaly anteaters, are mammals of the order Pholidota (). The one Neontology, extant family, the Manidae, has three genera: ''Manis'', ''Phataginus'', and ''Smutsia''. ''Manis'' comprises four species found in Asia, ...

). In a discredited alternative scenario, a close relationship exists between perissodactyls, carnivorans, and bats, this assembly comprising the Pegasoferae.

According to studies published in March 2015, odd-toed ungulates are in a close family relationship with at least some of the so-called Meridiungulata

South American native ungulates, commonly abbreviated as SANUs, are extinct ungulate-like mammals that were indigenous to South America from the Paleocene (from at least 63 million years ago) until the end of the Late Pleistocene (~12,000 years a ...

, a very diverse group of mammals living from the Paleocene to the Pleistocene in South America, whose systematic unity is largely unexplained. Some of these were classified based on their paleogeographic distribution. However, a close relationship can be worked out to perissodactyls by protein sequencing

Protein sequencing is the practical process of determining the amino acid sequence of all or part of a protein or peptide. This may serve to identify the protein or characterize its post-translational modifications. Typically, partial sequencing o ...

and comparison with fossil collagen from remnants of phylogenetically young members of the Meridiungulata (specifically ''Macrauchenia

''Macrauchenia'' ("long llama", based on the now-invalid llama genus, ''Auchenia'', from Greek "big neck") is an extinct genus of large ungulate native to South America from the Pliocene or Middle Pleistocene to the end of the Late Pleistocene. I ...

'' from the Litopterna

Litopterna (from "smooth heel") is an extinction, extinct order of South American native ungulates that lived from the Paleocene to the Pleistocene-Holocene around 62.5 million to 12,000 years ago (or possibly as late as 3,500 years ago), and we ...

and '' Toxodon'' from the Notoungulata

Notoungulata is an extinct order of ungulates that inhabited South America from the early Paleocene to the end of the Pleistocene, living from approximately 61 million to 11,000 years ago. Notoungulates were morphologically diverse, with forms re ...

). Both kinship groups, the odd-toed ungulates and the Litopterna-Notoungulata, are now in the higher-level taxon of Panperissodactyla. This kinship group is included among the Euungulata, which also contains the even-toed ungulates (Artiodactyla). The separation of the Litopterna-Notoungulata group from the perissodactyls probably took place before the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event

The Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) extinction event, also known as the K–T extinction, was the extinction event, mass extinction of three-quarters of the plant and animal species on Earth approximately 66 million years ago. The event cau ...

. "Condylarths" can probably be considered the starting point for the development of the two groups, as they represent a heterogeneous group of primitive ungulates that mainly inhabited the northern hemisphere in the Paleogene

The Paleogene Period ( ; also spelled Palaeogene or Palæogene) is a geologic period and system that spans 43 million years from the end of the Cretaceous Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Neogene Period Ma. It is the fir ...

.

Modern members

Odd-toed ungulates comprise three living families with around 17 species—in horses, however, the exact count is still controversial. Rhinos and tapirs are more closely related to each other than to horses. According to molecular genetic analysis, the separation of horses from other perissodactyls took place in thePaleocene

The Paleocene ( ), or Palaeocene, is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 66 to 56 mya (unit), million years ago (mya). It is the first epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), ...

some 56 million years ago, while the rhinos and tapirs split off in the lower-middle Eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (Ma). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes ...

, about 47 million years ago.

* Order Perissodactyla

**Suborder Hippomorpha

***Family Equidae

Equidae (commonly known as the horse family) is the Taxonomy (biology), taxonomic Family (biology), family of Wild horse, horses and related animals, including Asinus, asses, zebra, zebras, and many extinct species known only from fossils. The fa ...

: horses and allies, seven species in one genus

**** Wild horse

The wild horse (''Equus ferus'') is a species of the genus Equus (genus), ''Equus'', which includes as subspecies the modern domestication of the horse, domesticated horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') as well as the Endangered species, endangered ...

, ''Equus ferus''

*****Tarpan

The tarpan (''Equus ferus ferus'') was a free-ranging horse population of the Eurasian steppe from the 18th to the 20th century. What qualifies as a tarpan is subject to debate; it is unclear whether tarpans were genuine wild horses, feral domest ...

, †''Equus ferus ferus''

***** Przewalski's horse

Przewalski's horse (''Equus ferus przewalskii'' or ''Equus przewalskii''), also called the takhi, Mongolian wild horse or Dzungarian horse, is a rare and endangered wild horse originally native to the steppes of Central Asia. It is named after t ...

, ''Equus ferus przewalskii''

***** Domestic horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 mi ...

, ''Equus ferus caballus''

**** African wild ass

The African wild ass (''Equus africanus'') or African wild donkey is a wild member of the horse family, Equidae. This species is thought to be the ancestor of the domestic donkey (''Equus asinus''), which is sometimes placed within the same s ...

, ''Equus africanus''

***** Nubian wild ass, ''Equus africanus africanus''

***** Somali wild ass

The Somali wild ass (''Equus africanus somaliensis'') is a subspecies of the African wild ass.

It is found in Somalia, the Southern Red Sea region of Eritrea, and the Afar Region of Ethiopia. The legs of the Somali wild ass are striped, resemb ...

, ''Equus africanus somaliensis''

***** Domesticated ass (donkey

The donkey or ass is a domesticated equine. It derives from the African wild ass, ''Equus africanus'', and may be classified either as a subspecies thereof, ''Equus africanus asinus'', or as a separate species, ''Equus asinus''. It was domes ...

), ''Equus africanus asinus''

***** Atlas wild ass, †''Equus africanus atlanticus''

**** Onager

The onager (, ) (''Equus hemionus''), also known as hemione or Asiatic wild ass, is a species of the family Equidae native to Asia. A member of the subgenus ''Asinus'', the onager was Scientific description, described and given its binomial name ...

or Asiatic wild ass, ''Equus hemionus''

***** Mongolian wild ass

The Mongolian wild ass (''Equus hemionus hemionus''), also known as Mongolian khulan, is the nominate subspecies of the onager. It is found in southern Mongolia and northern China. It was previously found in eastern Kazakhstan and southern Sibe ...

, ''Equus hemionus hemionus''

***** Turkmenian kulan

The Turkmenian kulan (''Equus hemionus kulan''), also called Transcaspian wild ass, Turkmenistani onager or simply the ', is a subspecies of onager (Asiatic wild ass) native to Central Asia. It was declared Endangered in 2016.

The species's po ...

, ''Equus hemionus kulan''

***** Persian onager

The Persian onager (''Equus hemionus onager''), also called the Persian wild ass or Persian zebra, is a subspecies of onager (Asiatic wild ass) native to Iran. It is listed as Critically Endangered species, Critically Endangered, with no more tha ...

, ''Equus hemionus onager''

***** Indian wild ass

The Indian wild ass (''Equus hemionus khur''), also called the Indian wild donkey, Indian onager or, in the local Gujarati language, Ghudkhur and Khur, is a subspecies of the onager native to South Asia.

It is currently listed as Vulnerable b ...

, ''Equus hemionus khur''

***** Syrian wild ass

The Syrian wild ass (''Equus hemionus hemippus''), less commonly known as a hemippe, an achdari, or a Mesopotamian or Syrian onager, is an extinct subspecies of onager native to the Arabian Peninsula and surrounding areas. It ranged across prese ...

, †''Equus hemionus hemippus''

**** Kiang

The kiang (''Equus kiang'') is the largest of the ''Asinus'' subgenus. It is native to the Tibetan Plateau in Ladakh India, northern Pakistan, Tajikistan, China and northern Nepal. It inhabits montane grasslands and shrublands. Other common nam ...

or Tibetan wild ass, ''Equus kiang''

***** Western kiang, ''Equus kiang kiang''

***** Eastern kiang, ''Equus kiang holdereri''

***** Southern kiang, ''Equus kiang polyodon''

**** Plains zebra

The plains zebra (''Equus quagga'', formerly ''Equus burchellii'') is the most common and geographically widespread species of zebra. Its range is fragmented, but spans much of southern and eastern Africa south of the Sahara. Six or seven subspec ...

, ''Equus quagga''

***** Quagga

The quagga ( or ) (''Equus quagga quagga'') is an extinct subspecies of the plains zebra that was endemic to South Africa until it was hunted to extinction in the late 19th century. It was long thought to be a distinct species, but mtDNA ...

, †''Equus quagga quagga''

***** Burchell's zebra

Burchell's zebra (''Equus quagga burchellii'') is a southern subspecies of the plains zebra. It is named after the British explorer and naturalist William John Burchell. Common names include bontequagga, Damaraland zebra, and Zululand zebra (Gray ...

, ''Equus quagga burchellii''

***** Grant's zebra, ''Equus quagga boehmi''

***** Maneless zebra, ''Equus quagga borensis''

***** Chapman's zebra

Chapman's zebra (''Equus quagga chapmani''), named after explorer James Chapman (explorer), James Chapman, is a subspecies of the plains zebra from southern Africa.

Chapman's zebra are native to savannas and similar habitats of north-east South ...

, ''Equus quagga chapmani''

***** Crawshay's zebra, ''Equus quagga crawshayi''

***** Selous' zebra, ''Equus quagga selousi''

**** Mountain zebra

The mountain zebra (''Equus zebra'') is a zebra species in the family Equidae, native to southwestern Africa. There are two subspecies, the Cape mountain zebra (''E. z. zebra'') found in South Africa and Hartmann's mountain zebra (''E. z. hartma ...

, ''Equus zebra''

***** Cape mountain zebra, ''Equus zebra zebra''

*****Hartmann's mountain zebra

Hartmann's mountain zebra (''Equus zebra hartmannae'') is a subspecies of the mountain zebra found in far south-western Angola and western Namibia, easily distinguished from other similar zebra species by its dewlap as well as the lack of stripe ...

, ''Equus zebra hartmannae''

****Grévy's zebra

Grévy's zebra (''Equus grevyi)'', also known commonly as the imperial zebra, is the largest living species of wild equid and the most threatened of the three species of zebras, the other two being the plains zebra and the mountain zebra. Name ...

, ''Equus grevyi''

** Suborder Ceratomorpha

***Family Tapir

Tapirs ( ) are large, herbivorous mammals belonging to the family Tapiridae. They are similar in shape to a Suidae, pig, with a short, prehensile nose trunk (proboscis). Tapirs inhabit jungle and forest regions of South America, South and Centr ...

idae: tapirs, five species in one genus

**** Brazilian tapir, ''Tapirus terrestris''

**** Mountain tapir

The mountain tapir, also known as the Andean tapir or woolly tapir (''Tapirus pinchaque''), is the smallest of the four widely recognized species of tapir. It is found only in certain portions of the Andean Mountain Range in northwestern South A ...

, ''Tapirus pinchaque''

**** Baird's tapir

The Baird's tapir (''Tapirus bairdii''), also known as the Central American tapir, is a species of tapir native to Mexico, Central America, and northwestern South America. It is the largest of the three species of tapir native to the Americas, a ...

, ''Tapirus bairdii''

**** Malayan tapir

The Malayan tapir (''Tapirus indicus''), also called Asian tapir, Asiatic tapir, oriental tapir, Indian tapir, piebald tapir, or black-and-white tapir, is the only living tapir species outside of the Americas. It is native to Southeast Asia from ...

, ''Tapirus indicus''

****Kabomani tapir

The South American tapir (''Tapirus terrestris''), also commonly called the Brazilian tapir (from the Tupian language, Tupi ), the Amazonian tapir, the maned tapir, the lowland tapir, (Portuguese language, Brazilian Portuguese), and ''la sachava ...

, ''Tapirus kabomani''

*** Family Rhinocerotidae

A rhinoceros ( ; ; ; : rhinoceros or rhinoceroses), commonly abbreviated to rhino, is a member of any of the five extant taxon, extant species (or numerous extinct species) of odd-toed ungulates (perissodactyls) in the family (biology), famil ...

: rhinoceroses, five species in four genera

****Black rhinoceros

The black rhinoceros (''Diceros bicornis''), also called the black rhino or the hooked-lip rhinoceros, is a species of rhinoceros native to East Africa, East and Southern Africa, including Angola, Botswana, Eswatini, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Moza ...

, ''Diceros bicornis''

***** Southern black rhinoceros, †''Diceros bicornis bicornis''

***** North-eastern black rhinoceros, †''Diceros bicornis brucii''

***** Chobe black rhinoceros, ''Diceros bicornis chobiensis''

***** Uganda black rhinoceros, ''Diceros bicornis ladoensis''

***** Western black rhinoceros, †''Diceros bicornis longipes''

***** Eastern black rhinoceros, ''Diceros bicornis michaeli''

***** South-central black rhinoceros, ''Diceros bicornis minor''

***** South-western black rhinoceros, ''Diceros bicornis occidentalis''

**** White rhinoceros

The white rhinoceros, also known as the white rhino or square-lipped rhinoceros (''Ceratotherium simum''), is the largest extant species of rhinoceros and the most Sociality, social of all rhino species, characterized by its wide mouth adapted f ...

, ''Ceratotherium simum''

***** Southern white rhinoceros

The southern white rhinoceros or southern white rhino (''Ceratotherium simum simum'') is one of the two subspecies of the white rhinoceros (the other being the much rarer northern white rhinoceros). It is the most common and widespread subspecies ...

, ''Ceratotherium simum simum''

***** Northern white rhinoceros

The northern white rhinoceros or northern white rhino (''Ceratotherium simum cottoni'') is one of two subspecies of the white rhinoceros (the other being the southern white rhinoceros). This subspecies is a grazer in grasslands and savanna wood ...

, ''Ceratotherium simum cottoni''

**** Indian rhinoceros

The Indian rhinoceros (''Rhinoceros unicornis''), also known as the greater one-horned rhinoceros, great Indian rhinoceros or Indian rhino, is a species of rhinoceros found in the Indian subcontinent. It is the second largest living rhinocer ...

, ''Rhinoceros unicornis''

**** Javan rhinoceros, ''Rhinoceros sondaicus''

***** Indonesian Javan rhinoceros, ''Rhinoceros sondaicus sondaicus''

***** Vietnamese Javan rhinoceros, '' Rhinoceros sondaicus annamiticus''

***** Indian Javan rhinoceros, †''Rhinoceros sondaicus inermis''

**** Sumatran rhinoceros

The Sumatran rhinoceros (''Dicerorhinus sumatrensis''), also known as the Sumatran rhino, hairy rhinoceros or Asian two-horned rhinoceros, is a rare member of the family Rhinocerotidae and one of five extant species of rhinoceros; it is the o ...

, ''Dicerorhinus sumatrensis''

***** Western Sumatran rhinoceros, ''Dicerorhinus sumatrensis sumatrensis''

***** Eastern Sumatran rhinoceros, ''Dicerorhinus sumatrensis harrissoni''

***** Northern Sumatran rhinoceros, †''Dicerorhinus sumatrensis lasiotis''

Prehistoric members

There are many perissodactyl fossils of multivariant form. The major lines of development include the following groups:

*

There are many perissodactyl fossils of multivariant form. The major lines of development include the following groups:

*Eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (Ma). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes ...

.

*Equoidea

Equoidea is a superfamily of hippomorph perissodactyls containing the Equidae, Palaeotheriidae, and other basal equoids of unclear affinities, of which members of the genus '' Equus'' are the only extant species. The earliest fossil record of ...

also developed in the Eocene. Palaeotheriidae

Palaeotheriidae is an extinct family of herbivorous perissodactyl mammals that inhabited Europe, with less abundant remains also known from Asia, from the mid-Eocene to the early Oligocene. They are classified in Equoidea, along with the livin ...

are known mainly from Europe. In contrast, the horse family (Equidae

Equidae (commonly known as the horse family) is the Taxonomy (biology), taxonomic Family (biology), family of Wild horse, horses and related animals, including Asinus, asses, zebra, zebras, and many extinct species known only from fossils. The fa ...

) flourished and spread. Over time this group saw a reduction in toe number, extension of the limbs, and the progressive adjustment of the teeth for eating hard grasses.

* Chalicotherioidea represented another characteristic group, consisting of the families Chalicotheriidae and Lophiodontidae. The Chalicotheriidae developed claws instead of hooves and considerable extension of the forelegs. The best-known genera include '' Chalicotherium'' and '' Moropus''. Chalicotherioidea died out in the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( ; referred to colloquially as the ''ice age, Ice Age'') is the geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fin ...

.

*Rhinocerotoidea (rhino relatives) included a large variety of forms from the Eocene up to the Oligocene, including dog-size leaf feeders, semiaquatic animals, and also huge long-necked animals. Only a few had horns on the nose. The Amynodontidae

Amynodontidae ("defensive tooth") is a family of extinct perissodactyls related to true rhinoceroses. They are commonly portrayed as semiaquatic hippo-like rhinos but this description only fits members of the Metamynodontini; other groups of ...

were hippo-like, aquatic animals. Hyracodontidae

The Hyracodontidae are an extinction, extinct Family (biology), family of rhinocerotoids endemic to North America, Europe, and Asia during the Eocene through early Oligocene, living from 48.6 to 26.3 million years ago (Mya), existing about .

The ...

developed long limbs and long necks that were most pronounced in the ''Paraceratherium

''Paraceratherium'' is an extinct genus of hornless rhinocerotoids belonging to the family Paraceratheriidae. It is one of the largest terrestrial mammals that has ever existed and lived from the early to late Oligocene epoch (34–23 ...

'' (formerly known as ''Baluchitherium'' or ''Indricotherium''), the second largest known land mammal ever to have lived (after '' Palaeoloxodon namadicus''). The rhinos (Rhinocerotidae) emerged in the Middle Eocene; five species survive to the present day.

* Tapiroidea reached their greatest diversity in the Eocene, when several families lived in Eurasia and North America. They retained a primitive physique and were noted for developing a trunk. The extinct families within this group include the Helaletidae.

*Several mammal groups traditionally classified as condylarth

Condylarthra is an informal group – previously considered an Order (biology), order – of extinct placental mammals, known primarily from the Paleocene and Eocene epochs. They are considered early, primitive ungulates and is now largely consid ...

s, long-understood to be a wastebasket taxon

Wastebasket taxon (also called a wastebin taxon, dustbin taxon or catch-all taxon) is a term used by some taxonomists to refer to a taxon that has the purpose of classifying organisms that do not fit anywhere else. They are typically defined by e ...

, such as hyopsodontids and phenacodontids, are now understood to be part of the odd-toed ungulate assemblage. Phenacodontids seem to be stem-perissodactyls, while hyopsodontids are closely related to horses and brontotheres, despite their more primitive overall appearance.

* Desmostylia and Anthracobunidae

Anthracobunidae is an extinct family of stem perissodactyls that lived in the early to middle Eocene period. They were originally considered to be a paraphyletic family of primitive proboscideans possibly ancestral to the Moeritheriidae and th ...

have traditionally been placed among the afrotheres, but they may actually represent stem-perissodactyls. They are an early lineage of mammals that took to the water, spreading across semi-aquatic to fully marine niches in the Tethys Ocean

The Tethys Ocean ( ; ), also called the Tethys Sea or the Neo-Tethys, was a prehistoric ocean during much of the Mesozoic Era and early-mid Cenozoic Era. It was the predecessor to the modern Indian Ocean, the Mediterranean Sea, and the Eurasia ...

and the northern Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is bounded by the cont ...

. However, later studies have shown that, while anthracobunids are definite perissodactyls, desmostylians have enough mixed characters to suggest that a position among the Afrotheria is not out of the question.

* Order Perissodactyla

**Superfamily Brontotherioidea

*** † Brontotheriidae

**Suborder Hippomorpha

*** † Hyopsodontidae

*** † Pachynolophidae

*** Superfamily Equoidea

**** † Indolophidae

**** †Palaeotheriidae

Palaeotheriidae is an extinct family of herbivorous perissodactyl mammals that inhabited Europe, with less abundant remains also known from Asia, from the mid-Eocene to the early Oligocene. They are classified in Equoidea, along with the livin ...

(might be a basal perissodactyl grade instead)

** Clade Tapiromorpha

*** † Isectolophidae (a basal family of Tapiromorpha; from the Eocene epoch)

*** †Suborder Ancylopoda

**** † Lophiodontidae

**** Superfamily Chalicotherioidea

***** † Eomoropidae (basal grade of chalicotheroids)

***** † Chalicotheriidae

*** Suborder Ceratomorpha

**** Superfamily Rhinocerotoidea

Rhinocerotoidea is a superfamily (taxonomy), superfamily of Perissodactyla, perissodactyls that appeared 56 million years ago in the Paleocene. They included four extinct families, the Amynodontidae, the Hyracodontidae, the Paraceratheriidae, an ...

***** †Amynodontidae

Amynodontidae ("defensive tooth") is a family of extinct perissodactyls related to true rhinoceroses. They are commonly portrayed as semiaquatic hippo-like rhinos but this description only fits members of the Metamynodontini; other groups of ...

***** †Hyracodontidae

The Hyracodontidae are an extinction, extinct Family (biology), family of rhinocerotoids endemic to North America, Europe, and Asia during the Eocene through early Oligocene, living from 48.6 to 26.3 million years ago (Mya), existing about .

The ...

**** Superfamily Tapiroidea

***** †Deperetellidae

Deperetellidae is an extinct family of herbivorous odd-toed ungulates containing the genera '' Bahinolophus'', '' Deperetella'', '' Irenolophus'', and '' Teleolophus''. Their closest living relatives are tapirs. Deperetellids are known from the ...

***** † Rhodopagidae (sometimes recognized as a subfamily of deperetellids)

***** † Lophialetidae

***** † Eoletidae (sometimes recognized as a subfamily of lophialetids)

** †Anthracobunidae

Anthracobunidae is an extinct family of stem perissodactyls that lived in the early to middle Eocene period. They were originally considered to be a paraphyletic family of primitive proboscideans possibly ancestral to the Moeritheriidae and th ...

(a family of stem-perissodactyls; from the Early to Middle Eocene epoch)

** † Phenacodontidae (a clade of stem-perissodactyls; from the Early Palaeocene to the Middle Eocene epoch)

Higher classification of perissodactyls

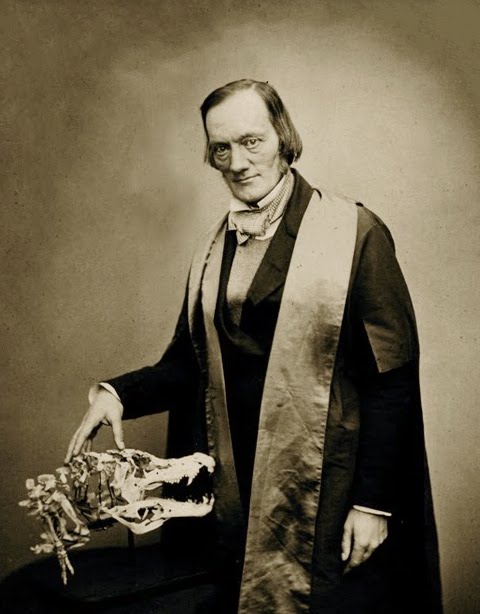

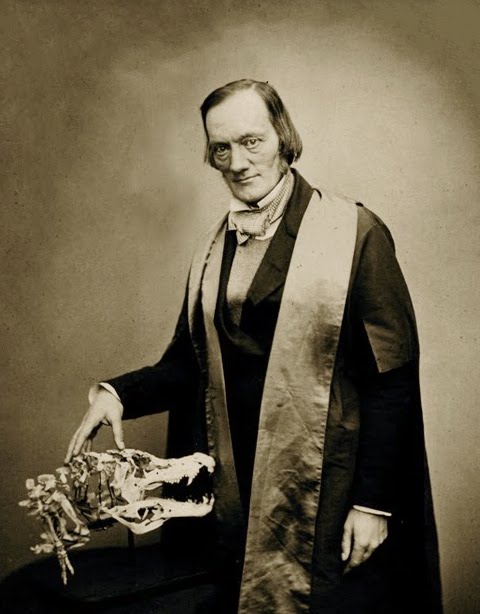

Relationships within the large group of odd-toed ungulates are not fully understood. Initially, after the establishment of "Perissodactyla" byRichard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

in 1848, the present-day representatives were considered equal in rank. In the first half of the 20th century, a more systematic differentiation of odd-toed ungulates began, based on a consideration of fossil forms, and they were placed in two major suborders: Hippomorpha and Ceratomorpha. The Hippomorpha comprises today's horses and their extinct members (Equoidea

Equoidea is a superfamily of hippomorph perissodactyls containing the Equidae, Palaeotheriidae, and other basal equoids of unclear affinities, of which members of the genus '' Equus'' are the only extant species. The earliest fossil record of ...

); the Ceratomorpha consist of tapirs and rhinos plus their extinct members ( Tapiroidea and Rhinocerotoidea

Rhinocerotoidea is a superfamily (taxonomy), superfamily of Perissodactyla, perissodactyls that appeared 56 million years ago in the Paleocene. They included four extinct families, the Amynodontidae, the Hyracodontidae, the Paraceratheriidae, an ...

). The names Hippomorpha and Ceratomorpha were introduced in 1937 by Horace Elmer Wood, in response to criticism of the name "Solidungula" that he proposed three years previously. It had been based on the grouping of horses and Tridactyla and on the rhinoceros/tapir complex. The extinct brontotheriidae were also classified under Hippomorpha and therefore possess a close relationship to horses. Some researchers accept this assignment because of similar dental features, but there is also the view that a very basal position within the odd-toed ungulates places them rather in the group of ''Titanotheriomorpha''.

Originally, the Chalicotheriidae were seen as members of Hippomorpha, and presented as such in 1941. William Berryman Scott thought that, as claw-bearing perissodactyls, they belong in the new suborder Ancylopoda (where Ceratomorpha and Hippomorpha as odd-toed ungulates were combined in the group of Chelopoda). The term Ancylopoda, coined by Edward Drinker Cope

Edward Drinker Cope (July 28, 1840 – April 12, 1897) was an American zoologist, paleontology, paleontologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist, herpetology, herpetologist, and ichthyology, ichthyologist. Born to a wealthy Quaker fam ...

in 1889, had been established for chalicotheres. However, further morphological studies from the 1960s showed a middle position of Ancylopoda between Hippomorpha and Ceratomorpha. Leonard Burton Radinsky saw all three major groups of odd-toed ungulates as peers, based on the extremely long and independent phylogenetic development of the three lines. In the 1980s, Jeremy J. Hooker saw a general similarity between Ancylopoda and Ceratomorpha based on dentition, especially in the earliest members, leading to the unification in 1984 of the two submissions in the interim order, ''Tapiromorpha''. At the same time, he expanded the Ancylopoda to include the ''Lophiodontidae''. The name "Tapiromorpha" goes back to Ernst Haeckel, who coined it in 1873, but it was long considered synonymous to Ceratomorpha because Wood had not considered it in 1937 when Ceratomorpha were named, since the term had been used quite differently in the past. Also in 1984, Robert M. Schoch used the conceptually similar term Moropomorpha, which today applies synonymously to Tapiromorpha. Included within the Tapiromorpha are the now extinct Isectolophidae, a sister group of the Ancylopoda-Ceratomorpha group and thus the most primitive members of this relationship complex.

Evolutionary history

Origins

The evolutionary development of Perissodactyla is well documented in the fossil record. Numerous finds are evidence of theadaptive radiation

In evolutionary biology, adaptive radiation is a process in which organisms diversify rapidly from an ancestral species into a multitude of new forms, particularly when a change in the environment makes new resources available, alters biotic int ...

of this group, which was once much more varied and widely dispersed. '' Radinskya'' from the late Paleocene

The Paleocene ( ), or Palaeocene, is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 66 to 56 mya (unit), million years ago (mya). It is the first epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), ...

of East Asia is often considered to be one of the oldest close relatives of the ungulates. Its 8 cm skull must have belonged to a very small and primitive animal with a π-shaped crown pattern on the enamel of its rear molars similar to that of perissodactyls and their relatives, especially the rhinos. Finds of '' Cambaytherium'' and ''Kalitherium'' in the Cambay shale of western India indicate an origin in Asia dating to the Lower Eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (Ma). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes ...

roughly 54.5 million years ago. Their teeth also show similarities to ''Radinskya'' as well as to the Tethytheria clade. The saddle-shaped configuration of the navicular joints and the mesaxonic construction of the front and hind feet also indicates a close relationship to Tethytheria. However, this construction deviates from that of ''Cambaytherium'', indicating that it is actually a member of a sister group. Ancestors of Perissodactyla may have arrived via an island bridge from the Afro-Arab landmass onto the Indian subcontinent as it drifted north towards Asia. A study on ''Cambaytherium'' suggests an origin in India prior

The term prior may refer to:

* Prior (ecclesiastical), the head of a priory (monastery)

* Prior convictions, the life history and previous convictions of a suspect or defendant in a criminal case

* Prior probability, in Bayesian statistics

* Prio ...

or near its collision with Asia.

The alignment of hyopsodontids and phenacodontids to Perissodactyla in general suggests an older Laurasian origin and distribution for the clade, dispersed across the northern continents already in the early Paleocene. These forms already show a fairly well-developed molar morphology, with no intermediary forms as evidence of the course of its development. The close relationship between meridiungulate mammals and perissoodactyls in particular is of interest since the latter appeared in South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a considerably smaller portion in the Northern Hemisphere. It can also be described as the southern Subregion#Americas, subregion o ...

soon after the K–T event, implying rapid ecological radiation and dispersal after mass extinction.

Phylogeny

The Perissodactyla appeared relatively abruptly at the beginning of the Lower Paleocene about 63 million years ago, both in North America and Asia, in the form of phenacodontids and hyopsodontids. The oldest finds from an extant group originate among other sources, from '' Sifrhippus'', an ancestor of the horses from the Willswood lineup in northwestern

The Perissodactyla appeared relatively abruptly at the beginning of the Lower Paleocene about 63 million years ago, both in North America and Asia, in the form of phenacodontids and hyopsodontids. The oldest finds from an extant group originate among other sources, from '' Sifrhippus'', an ancestor of the horses from the Willswood lineup in northwestern Wyoming

Wyoming ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States, Western United States. It borders Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho t ...

. The distant ancestors of tapirs appeared not too long after that in the Ghazij lineup in Balochistan

Balochistan ( ; , ), also spelled as Baluchistan or Baluchestan, is a historical region in West and South Asia, located in the Iranian plateau's far southeast and bordering the Indian Plate and the Arabian Sea coastline. This arid region o ...

, such as ''Ganderalophus'', as well as ''Litolophus'' from the Chalicotheriidae line, or ''Eotitanops'' from the group of brontotheriidae. Initially, the members of the different lineages looked quite similar, with an arched back and generally four toes on the front and three on the hind feet. ''Eohippus

''Eohippus'' is an extinct genus of small equid ungulates. The only species is ''E. angustidens'', which was long considered a species of ''Hyracotherium'' (now strictly defined as a member of the Palaeotheriidae rather than the Equidae). Its rem ...

'', which is considered a member of the horse family, outwardly resembled ''Hyrachyus

''Hyrachyus'' (from ''Hyrax'' and "pig") is an extinct genus of perissodactyl mammal that lived in Eocene Europe, North America, and Asia. Its remains have also been found in Jamaica. It is closely related to ''Lophiodon''.Hayden, F.V''Report of ...

'', the first representative of the rhino and tapir line. All were small compared to later forms and lived as fruit and foliage eaters in forests. The first of the megafauna

In zoology, megafauna (from Ancient Greek, Greek μέγας ''megas'' "large" and Neo-Latin ''fauna'' "animal life") are large animals. The precise definition of the term varies widely, though a common threshold is approximately , this lower en ...

to emerge were the brontotheres, in the Middle and Upper Eocene. ''Megacerops'', known from North America, reached a withers height of and could have weighed just over . The decline of brontotheres at the end of the Eocene is associated with competition arising from the advent of more successful herbivores.

More successful lines of odd-toed ungulates emerged at the end of the Eocene when dense jungles gave way to steppe, such as the chalicotheriid rhinos, and their immediate relatives; their development also began with very small forms. ''Paraceratherium

''Paraceratherium'' is an extinct genus of hornless rhinocerotoids belonging to the family Paraceratheriidae. It is one of the largest terrestrial mammals that has ever existed and lived from the early to late Oligocene epoch (34–23 ...

'', one of the largest mammals ever to walk the earth, evolved during this era. They weighed up to and lived throughout the Oligocene in Eurasia. About 20 million years ago, at the onset of the Miocene, the perissodactyls first reached Africa when it became connected to Eurasia because of the closing of the Tethys Ocean

The Tethys Ocean ( ; ), also called the Tethys Sea or the Neo-Tethys, was a prehistoric ocean during much of the Mesozoic Era and early-mid Cenozoic Era. It was the predecessor to the modern Indian Ocean, the Mediterranean Sea, and the Eurasia ...

. For the same reason, however, new animals such as the mammoth

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus.'' They lived from the late Miocene epoch (from around 6.2 million years ago) into the Holocene until about 4,000 years ago, with mammoth species at various times inhabi ...

s also entered the ancient settlement areas of odd-toed ungulates, creating competition that led to the extinction of some of their lines. The rise of ruminant

Ruminants are herbivorous grazing or browsing artiodactyls belonging to the suborder Ruminantia that are able to acquire nutrients from plant-based food by fermenting it in a specialized stomach prior to digestion, principally through microb ...

s, which occupied similar ecological niches and had a much more efficient digestive system, is also associated with the decline in diversity of odd-toed ungulates. A significant cause for the decline of perissodactyls was climate change during the Miocene, leading to a cooler and drier climate accompanied by the spread of open landscapes. However, some lines flourished, such as the horses and rhinos; anatomical adaptations made it possible for them to consume tougher grass food. This led to open land forms that dominated newly created landscapes. With the emergence of the Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama, historically known as the Isthmus of Darien, is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North America, North and South America. The country of Panama is located on the i ...

in the Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch (geology), epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.33 to 2.58Elasmotherium

''Elasmotherium'' is an extinct genus of large rhinoceros that lived in Eastern Europe, Central Asia and East Asia during Late Miocene through to the Late Pleistocene, with the youngest reliable dates of at least 39,000 years ago. It was ...

''. Whether over-hunting by humans (overkill hypothesis), climatic change, or a combination of both factors was responsible for the extinction of ice age mega-fauna, remains controversial.

Research history

In 1758, in his seminal work ''Systema Naturae'',

In 1758, in his seminal work ''Systema Naturae'', Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

(1707–1778) classified horses (''Equus'') together with hippo

The hippopotamus (''Hippopotamus amphibius;'' ; : hippopotamuses), often shortened to hippo (: hippos), further qualified as the common hippopotamus, Nile hippopotamus and river hippopotamus, is a large semiaquatic Mammal, mammal native to su ...

s (''Hippopotamus''). At that time, this category also included the tapirs (''Tapirus''), more precisely the lowland or South American tapir (''Tapirus terrestus''), the only tapir then known in Europe. Linnaeus classified this tapir as ''Hippopotamus terrestris'' and put both genera in the group of the ''Belluae'' ("beasts"). He combined the rhinos with the Glires

Glires (, Latin ''glīrēs'' 'dormice') is a clade (sometimes ranked as a grandorder) consisting of rodents and lagomorphs ( rabbits, hares, and pikas). The hypothesis that these form a monophyletic group has been long debated based on morph ...

, a group now consisting of the lagomorphs and rodent

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the Order (biology), order Rodentia ( ), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and Mandible, lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal specie ...

s. Mathurin Jacques Brisson

Mathurin Jacques Brisson (; 30 April 1723 – 23 June 1806) was a French zoologist and natural philosophy, natural philosopher.

Brisson was born on 30 April 1723 at Fontenay-le-Comte in the Vendée department of western France. Note that page 14 ...

(1723–1806) first separated the tapirs and hippos in 1762 with the introduction of the concept ''le tapir''. He also separated the rhinos from the rodents, but did not combine the three families now known as the odd-toed ungulates. In the transition to the 19th century, the individual perissodactyl genera were associated with various other groups, such as the proboscidea

Proboscidea (; , ) is a taxonomic order of afrotherian mammals containing one living family (Elephantidae) and several extinct families. First described by J. Illiger in 1811, it encompasses the elephants and their close relatives. Three l ...

n and even-toed ungulate

Artiodactyls are placental mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla ( , ). Typically, they are ungulates which bear weight equally on two (an even number) of their five toes (the third and fourth, often in the form of a hoof). The other t ...

s. In 1795, Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (1772–1844) and Georges Cuvier