Battle of Thermopylae on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

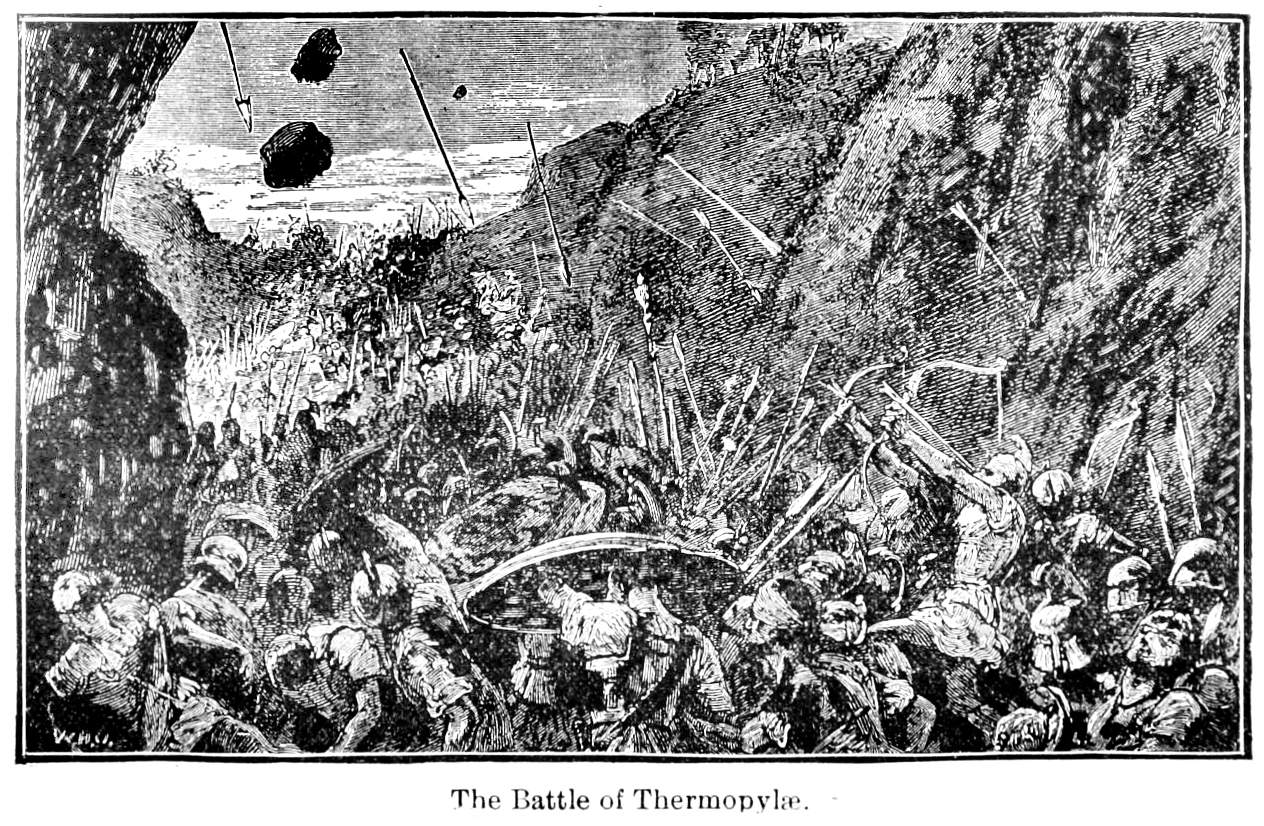

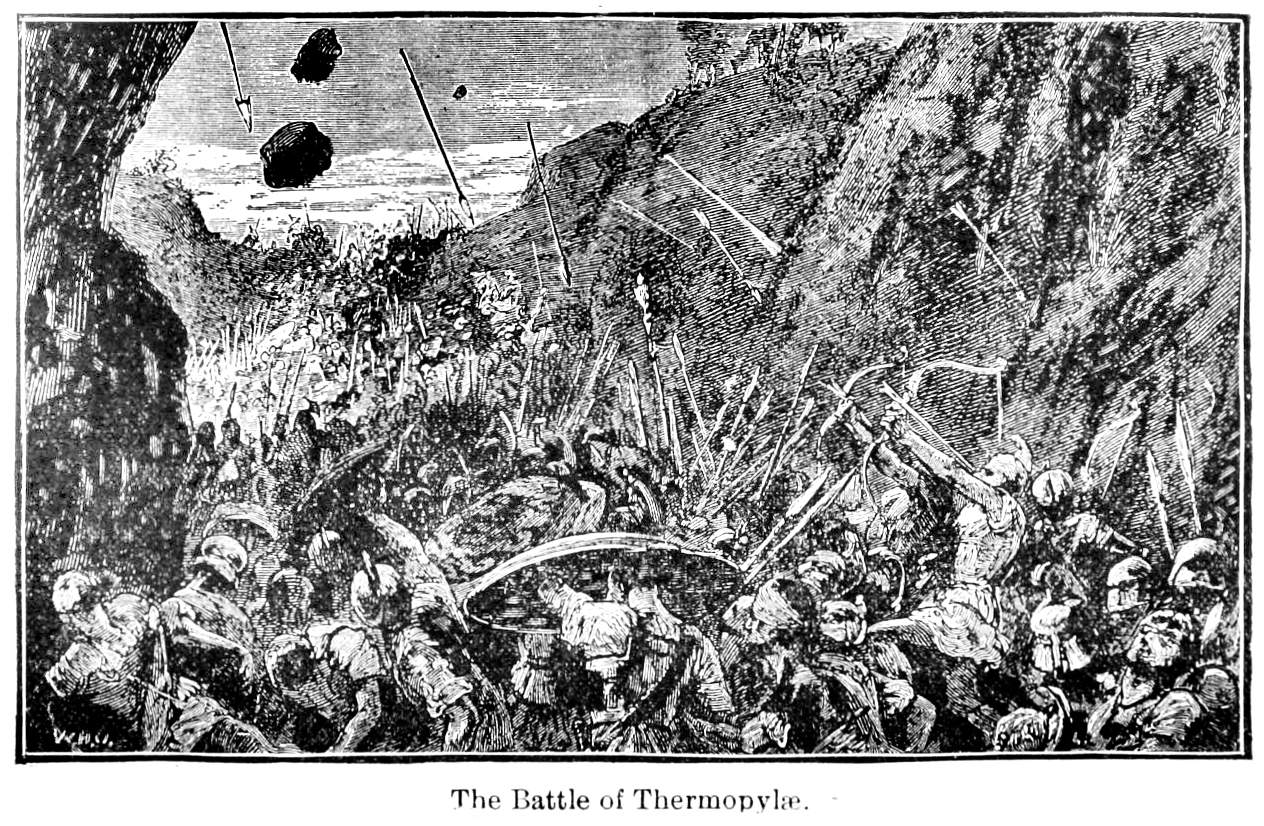

The Battle of Thermopylae ( ) was fought in 480 BC between the

The city-states of

The city-states of  Darius sent emissaries to all the Greek city-states in 491 BC asking for a gift of " earth and water" as tokens of their submission to him.Holland, pp. 178–179 Having had a demonstration of his power the previous year, the majority of Greek cities duly obliged. In Athens, however, the ambassadors were put on trial and then executed by throwing them in a pit; in Sparta, they were simply thrown down a well. This meant that Sparta was also effectively at war with Persia. However, in order to appease the Persian king somewhat, two Spartans were voluntarily sent to

Darius sent emissaries to all the Greek city-states in 491 BC asking for a gift of " earth and water" as tokens of their submission to him.Holland, pp. 178–179 Having had a demonstration of his power the previous year, the majority of Greek cities duly obliged. In Athens, however, the ambassadors were put on trial and then executed by throwing them in a pit; in Sparta, they were simply thrown down a well. This meant that Sparta was also effectively at war with Persia. However, in order to appease the Persian king somewhat, two Spartans were voluntarily sent to  At this, Darius began raising a huge new army with which to completely subjugate Greece; however, in 486 BC, his

At this, Darius began raising a huge new army with which to completely subjugate Greece; however, in 486 BC, his

VII, 145

and a confederate alliance of

VII, 173

Shortly afterwards, they received the news that Xerxes had crossed the Hellespont. Themistocles, therefore, suggested a second strategy to the Greeks: the route to southern Greece (Boeotia, Attica, and the Peloponnesus) would require Xerxes' army to travel through the very narrow pass of

/ref> It was also the time of the

VII, 205

The Spartan force was reinforced ''en route'' to Thermopylae by contingents from various cities and numbered more than 7,000 by the time it arrived at the pass. Leonidas chose to camp at, and defend, the "middle gate", the narrowest part of the pass of Thermopylae, where the Phocians had built a defensive wall some time before. News also reached Leonidas, from the nearby city of Trachis, that there was a mountain track that could be used to outflank the pass of Thermopylae. Leonidas stationed 1,000 Phocians on the heights to prevent such a manoeuvre.Herodotu

VII, 217

/ref> Finally, in mid-August, the Persian army was sighted across the Malian Gulf approaching Thermopylae. With the Persian army's arrival at Thermopylae the Greeks held a council of war. Some Peloponnesians suggested withdrawal to the Isthmus of Corinth and blocking the passage to Peloponnesus. The Phocians and Locrians, whose states were located nearby, became indignant and advised defending Thermopylae and sending for more help. Leonidas calmed the panic and agreed to defend Thermopylae.Herodotu

VII, 207

According to Plutarch, when one of the soldiers complained that, "Because of the arrows of the barbarians it is impossible to see the sun", Leonidas replied, "Won't it be nice, then, if we shall have shade in which to fight them?" Herodotus reports a similar comment, but attributes it to Dienekes. Xerxes sent a Persian emissary to negotiate with Leonidas. The Greeks were offered their freedom, the title "Friends of the Persian People", and the opportunity to re-settle on land better than that they possessed.Holland, pp. 270–271 When Leonidas refused these terms, the ambassador carried a written message by Xerxes, asking him to "Hand over your arms". Leonidas' famous response to the Persians was ''" Molṑn labé"'' (Μολὼν λαβέ – literally, "having come, take

The number of troops which Xerxes mustered for the second invasion of Greece has been the subject of endless dispute, most notably between ancient sources, which report very large numbers, and modern scholars, who surmise much smaller figures. Herodotus claimed that there were, in total, 2.6 million military personnel, accompanied by an equivalent number of support personnel.Herodotu

The number of troops which Xerxes mustered for the second invasion of Greece has been the subject of endless dispute, most notably between ancient sources, which report very large numbers, and modern scholars, who surmise much smaller figures. Herodotus claimed that there were, in total, 2.6 million military personnel, accompanied by an equivalent number of support personnel.Herodotu

VII, 186

The poet

VII, 202

and Diodorus Siculus,Diodorus Siculu

XI, 4

the Greek army included the following forces: Notes: * The number of Peloponnesians :Diodorus suggests that there were 1,000 Lacedemonians and 3,000 other Peloponnesians, totalling 4,000. Herodotus agrees with this figure in one passage, quoting an inscription by

VII, 228

However, elsewhere, in the passage summarised by the above table, Herodotus tallies 3,100 Peloponnesians at Thermopylae before the battle. Herodotus also reports that at Xerxes' public showing of the dead, "helots were also there for them to see",Herodotu

VIII, 25

but he does not say how many or in what capacity they served. Thus, the difference between his two figures can be squared by supposing (without proof) that there were 900 helots (three per Spartan) present at the battle.Macan, note to Herodotus VIII, 25 If helots were present at the battle, there is no reason to doubt that they served in their traditional role as armed retainers to individual Spartans. Alternatively, Herodotus' "missing" 900 troops might have been Further confusing the issue is Diodorus' ambiguity about whether his count of 1,000 Lacedemonians included the 300 Spartans. At one point he says: "Leonidas, when he received the appointment, announced that only one thousand men should follow him on the campaign". However, he then says: "There were, then, of the Lacedemonians one thousand, and with them three hundred Spartiates". It is therefore impossible to be clearer on this point.

Pausanias' account agrees with that of Herodotus (whom he probably read) except that he gives the number of Locrians, which Herodotus declined to estimate. Residing in the direct path of the Persian advance, they gave all the fighting men they had – according to Pausanias 6,000 men – which added to Herodotus' 5,200 would have given a force of 11,200.

Many modern historians, who usually consider Herodotus more reliable,Green, p. 140 add the 1,000 Lacedemonians and the 900 helots to Herodotus' 5,200 to obtain 7,100 or about 7,000 men as a standard number, neglecting Diodorus' Melians and Pausanias' Locrians.Bury, pp. 271–282 However, this is only one approach, and many other combinations are plausible. Furthermore, the numbers changed later on in the battle when most of the army retreated and only approximately 3,000 men remained (300 Spartans, 700 Thespians, 400 Thebans, possibly up to 900 helots, and 1,000 Phocians stationed above the pass, less the casualties sustained in the previous days).

Further confusing the issue is Diodorus' ambiguity about whether his count of 1,000 Lacedemonians included the 300 Spartans. At one point he says: "Leonidas, when he received the appointment, announced that only one thousand men should follow him on the campaign". However, he then says: "There were, then, of the Lacedemonians one thousand, and with them three hundred Spartiates". It is therefore impossible to be clearer on this point.

Pausanias' account agrees with that of Herodotus (whom he probably read) except that he gives the number of Locrians, which Herodotus declined to estimate. Residing in the direct path of the Persian advance, they gave all the fighting men they had – according to Pausanias 6,000 men – which added to Herodotus' 5,200 would have given a force of 11,200.

Many modern historians, who usually consider Herodotus more reliable,Green, p. 140 add the 1,000 Lacedemonians and the 900 helots to Herodotus' 5,200 to obtain 7,100 or about 7,000 men as a standard number, neglecting Diodorus' Melians and Pausanias' Locrians.Bury, pp. 271–282 However, this is only one approach, and many other combinations are plausible. Furthermore, the numbers changed later on in the battle when most of the army retreated and only approximately 3,000 men remained (300 Spartans, 700 Thespians, 400 Thebans, possibly up to 900 helots, and 1,000 Phocians stationed above the pass, less the casualties sustained in the previous days).

From a strategic point of view, by defending Thermopylae, the Greeks were making the best possible use of their forces. As long as they could prevent a further Persian advance into Greece, they had no need to seek a decisive battle and could, thus, remain on the defensive. Moreover, by defending two constricted passages (Thermopylae and Artemisium), the Greeks' inferior numbers became less of a factor. Conversely, for the Persians the problem of supplying such a large army meant they could not remain in the same place for very long.Holland, pp. 285–287 The Persians, therefore, had to retreat or advance, and advancing required forcing the pass of Thermopylae.

Tactically, the pass at Thermopylae was ideally suited to the Greek style of warfare. A hoplite

From a strategic point of view, by defending Thermopylae, the Greeks were making the best possible use of their forces. As long as they could prevent a further Persian advance into Greece, they had no need to seek a decisive battle and could, thus, remain on the defensive. Moreover, by defending two constricted passages (Thermopylae and Artemisium), the Greeks' inferior numbers became less of a factor. Conversely, for the Persians the problem of supplying such a large army meant they could not remain in the same place for very long.Holland, pp. 285–287 The Persians, therefore, had to retreat or advance, and advancing required forcing the pass of Thermopylae.

Tactically, the pass at Thermopylae was ideally suited to the Greek style of warfare. A hoplite

VII, 176

The name "Hot Gates" comes from the

VIII, 201

The terrain of the battlefield was nothing that Xerxes and his forces were accustomed to. Although coming from a mountainous country, the Persians were not prepared for the real nature of the country they had invaded. The pure ruggedness of this area is caused by torrential downpours for four months of the year, combined with an intense summer season of scorching heat that cracks the ground. Vegetation is scarce and consists of low, thorny shrubs. The hillsides along the pass are covered in thick brush, with some plants reaching high. With the sea on one side and steep, impassable hills on the other, King Leonidas and his men chose the perfect topographical position to battle the Persian invaders. Today, the pass is not near the sea, but is several kilometres inland because of

On the fifth day after the Persian arrival at Thermopylae and the first day of the battle, Xerxes finally resolved to attack the Greeks. First, he ordered 5,000 archers to shoot a barrage of arrows, but they were ineffective; they shot from at least 100 yards away, according to modern day scholars, and the Greeks' wooden shields (sometimes covered with a very thin layer of bronze) and bronze helmets deflected the arrows.

After that, Xerxes sent a force of 10,000

On the fifth day after the Persian arrival at Thermopylae and the first day of the battle, Xerxes finally resolved to attack the Greeks. First, he ordered 5,000 archers to shoot a barrage of arrows, but they were ineffective; they shot from at least 100 yards away, according to modern day scholars, and the Greeks' wooden shields (sometimes covered with a very thin layer of bronze) and bronze helmets deflected the arrows.

After that, Xerxes sent a force of 10,000

VII, 210

Diodorus Siculu

XI, 6

The Persians soon launched a

VII, 208

Details of the tactics are scant; Diodorus says, "the men stood shoulder to shoulder", and the Greeks were "superior in valour and in the great size of their shields."Diodorus Siculu

XI, 7

This probably describes the standard Greek phalanx, in which the men formed a wall of overlapping shields and layered spear points protruding out from the sides of the shields, which would have been highly effective as long as it spanned the width of the pass. The weaker shields, and shorter spears and swords of the Persians prevented them from effectively engaging the Greek hoplites.Herodotu

VII, 211.1

211.2

, an

211.3

. Herodotus says that the units for each city were kept together; units were rotated in and out of the battle to prevent fatigue, which implies the Greeks had more men than necessary to block the pass.Herodotu

VII, 204

The Greeks killed so many Medes that Xerxes is said to have stood up three times from the seat from which he was watching the battle.Herodotu

VII, 212

According to Ctesias, the first wave was "cut to ribbons", with only two or three Spartans killed in return. According to Herodotus and Diodorus, Xerxes, having taken the measure of the enemy, threw his best troops into a second assault the same day, the Immortals, an elite corps of 10,000 men. However, the Immortals fared no better than the Medes, and failed to make any headway against the Greeks. The Spartans reportedly used a tactic of feigning retreat, and then turning and killing the enemy troops when they ran after them.

VII, 213

For this act, the name "Ephialtes" received a lasting stigma; it came to mean "nightmare" in the Greek language and to symbolise the archetypal traitor in Greek culture. Herodotus reports that Xerxes sent his commander

At daybreak on the third day, the Phocians guarding the path above Thermopylae became aware of the outflanking Persian column by the rustling of oak leaves. Herodotus says they jumped up and were greatly amazed.Herodotu

At daybreak on the third day, the Phocians guarding the path above Thermopylae became aware of the outflanking Persian column by the rustling of oak leaves. Herodotus says they jumped up and were greatly amazed.Herodotu

VII, 218

Hydarnes was perhaps just as amazed to see them hastily arming themselves as they were to see him and his forces.Holland, p. 291–293 He feared they were Spartans but was informed by Ephialtes that they were not. The Phocians retreated to a nearby hill to make their stand (assuming the Persians had come to attack them). However, not wishing to be delayed, the Persians merely shot a volley of arrows at them, before bypassing them to continue with their

Achaemenid Persian Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, it was the larges ...

under Xerxes I

Xerxes I ( – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was a List of monarchs of Persia, Persian ruler who served as the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 486 BC until his assassination in 465 BC. He was ...

and an alliance of Greek city-states

Polis (: poleis) means 'city' in Ancient Greek. The ancient word ''polis'' had socio-political connotations not possessed by modern usage. For example, Modern Greek πόλη (polē) is located within a (''khôra''), "country", which is a πατ ...

led by Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

under Leonidas I

Leonidas I (; , ''Leōnídas''; born ; died 11 August 480 BC) was king of the Ancient Greek city-state of Sparta. He was the son of king Anaxandridas II and the 17th king of the Agiad dynasty, a Spartan royal house which claimed descent fro ...

. Lasting over the course of three days, it was one of the most prominent battles of both the second Persian invasion of Greece

The second Persian invasion of Greece (480–479 BC) occurred during the Greco-Persian Wars, as King Xerxes I of Persia sought to conquer all of Greece. The invasion was a direct, if delayed, response to the defeat of the first Persian invasi ...

and the wider Graeco-Persian Wars.

The engagement at Thermopylae

Thermopylae (; ; Ancient: , Katharevousa: ; ; "hot gates") is a narrow pass and modern town in Lamia (city), Lamia, Phthiotis, Greece. It derives its name from its Mineral spring, hot sulphur springs."Thermopylae" in: S. Hornblower & A. Spaw ...

occurred simultaneously with the naval Battle of Artemisium

The Battle of Artemisium or Artemision was a series of naval engagements over three days during the second Persian invasion of Greece. The battle took place simultaneously with the land battle at Thermopylae, in August or September 480 BC, off t ...

: between July and September during 480 BC. The second Persian invasion under Xerxes I

Xerxes I ( – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was a List of monarchs of Persia, Persian ruler who served as the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 486 BC until his assassination in 465 BC. He was ...

was a delayed response to the failure of the first Persian invasion, which had been initiated by Darius I

Darius I ( ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his death in 486 BCE. He ruled the empire at its territorial peak, when it included much of West A ...

and ended in 490 BC by an Athenian

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

-led Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

victory at the Battle of Marathon

The Battle of Marathon took place in 490 BC during the first Persian invasion of Greece. It was fought between the citizens of Athens (polis), Athens, aided by Plataea, and a Achaemenid Empire, Persian force commanded by Datis and Artaph ...

. By 480 BC, a decade after the Persian defeat at Marathon

The marathon is a long-distance foot race with a distance of kilometres ( 26 mi 385 yd), usually run as a road race, but the distance can be covered on trail routes. The marathon can be completed by running or with a run/walk strategy. There ...

, Xerxes had amassed a massive land and naval force, and subsequently set out to conquer all of Greece. In response, the Athenian politician and general Themistocles

Themistocles (; ; ) was an Athenian politician and general. He was one of a new breed of non-aristocratic politicians who rose to prominence in the early years of the Athenian democracy. As a politician, Themistocles was a populist, having th ...

proposed that the allied Greeks block the advance of the Persian army at the pass of Thermopylae while simultaneously blocking the Persian navy at the Straits of Artemisium.

Around the start of the invasion, a Greek force of approximately 7,000 men led by Leonidas marched north to block the pass of Thermopylae. Ancient authors vastly inflated the size of the Persian army, with estimates in the millions, but modern scholars estimate it at between 120,000 and 300,000 soldiers. They arrived at Thermopylae by late August or early September; the outnumbered Greeks held them off for seven days (including three of direct battle) before their rear-guard was annihilated in one of history's most famous last stands. During two full days of battle, the Greeks blocked the only road by which the massive Persian army could traverse the narrow pass. After the second day, a local resident named Ephialtes

Ephialtes (, ''Ephialtēs'') was an ancient Athenian politician and an early leader of the democratic movement there. In the late 460s BC, he oversaw reforms that diminished the power of the Areopagus, a traditional bastion of conservatism, and w ...

revealed to the Persians the existence of a path leading behind the Greek lines. Subsequently, Leonidas, aware that his force was being outflanked by the Persians, dismissed the bulk of the Greek army and remained to guard their retreat along with 300 Spartans

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the valley of Evrotas river in Laconia, in southeastern P ...

and 700 Thespians. It has been reported that others also remained, including up to 900 helots

The helots (; , ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their exact characteristic ...

and 400 Thebans

Thebes ( ; , ''Thíva'' ; , ''Thêbai'' .) is a city in Boeotia, Central Greece, and is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world. It is the largest city in Boeotia and a major center for the area along with Livadeia and ...

. With the exception of the Thebans, most of whom reportedly surrendered, the Greeks fought the Persians to the death.

Themistocles

Themistocles (; ; ) was an Athenian politician and general. He was one of a new breed of non-aristocratic politicians who rose to prominence in the early years of the Athenian democracy. As a politician, Themistocles was a populist, having th ...

was in command of the Greek naval force at Artemisium when he received news that the Persians had taken the pass at Thermopylae. Since the Greek defensive strategy had required both Thermopylae and Artemisium to be held, the decision was made to withdraw to the island of Salamis. The Persians overran Boeotia

Boeotia ( ), sometimes Latinisation of names, Latinized as Boiotia or Beotia (; modern Greek, modern: ; ancient Greek, ancient: ), is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the modern regions of Greece, region of Central Greece (adm ...

and then captured the evacuated city of Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

. The Greek fleet—seeking a decisive victory over the Persian armada—attacked and defeated the invading force at the Battle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis ( ) was a naval battle fought in 480 BC, between an alliance of Greek city-states under Themistocles, and the Achaemenid Empire under King Xerxes. It resulted in a victory for the outnumbered Greeks.

The battle was fou ...

in late 480 BC. Wary of being trapped in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

, Xerxes withdrew with much of his army to Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

, reportedly losing many of his troops to starvation and disease while also leaving behind the Persian military commander Mardonius to continue the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

's Greek campaign. However, the following year saw a Greek army decisively defeat Mardonius and his troops at the Battle of Plataea

The Battle of Plataea was the final land battle during the second Persian invasion of Greece. It took place in 479BC near the city of Plataea in Boeotia, and was fought between an alliance of the Polis, Greek city-states (including Sparta, Cla ...

, ending the second Persian invasion.

Both ancient and modern writers have used the Battle of Thermopylae as a flagship example of the power of an army defending its native soil. The performance of the Greek defenders is also used as an example of the advantages of training, equipment, and use of terrain as force multipliers.

Sources

The primary source for the Graeco-Persian Wars is the Greek historianHerodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

. The Sicilian historian Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus or Diodorus of Sicily (; 1st century BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek historian from Sicily. He is known for writing the monumental Universal history (genre), universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty ...

, writing in the 1st century BC in his ''Bibliotheca historica

''Bibliotheca historica'' (, ) is a work of Universal history (genre), universal history by Diodorus Siculus. It consisted of forty books, which were divided into three sections. The first six books are geographical in theme, and describe the h ...

'', also provides an account of the Graeco-Persian wars, partially derived from the earlier Greek historian Ephorus. Diodorus is fairly consistent with Herodotus' writings. These wars are also described in less detail by a number of other ancient historians including Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

, Ctesias of Cnidus

Ctesias ( ; ; ), also known as Ctesias of Cnidus, was a Hellenic civilization, Greek physician and historian from the town of Cnidus in Caria, then part of the Achaemenid Empire.

Historical events

Ctesias, who lived in the fifth century BC, was ...

, and are referred to by other authors, as by Aeschylus

Aeschylus (, ; ; /524 – /455 BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek Greek tragedy, tragedian often described as the father of tragedy. Academic knowledge of the genre begins with his work, and understanding of earlier Greek tragedy is large ...

in ''The Persians

''The Persians'' (, ''Persai'', Latinised as ''Persae'') is an ancient Greek tragedy written during the Classical period of Ancient Greece by the Greek tragedian Aeschylus. It is the second and only surviving part of a now otherwise lost trilog ...

''.

Archaeological evidence, such as the Serpent Column

The Serpent Column ( ' "Three-headed Serpent";, i.e. "the bronze three-headed serpent"; see

See also , . "Serpentine Column"), also known as the Serpentine Column, Plataean Tripod or Delphi Tripod, is an ancient bronze column at the Hippodrom ...

(now in the Hippodrome of Constantinople

The Hippodrome of Constantinople (; ; ) was a Roman circus, circus that was the sporting and social centre of Constantinople, capital of the Byzantine Empire. Today it is a square in Istanbul, Turkey, known as Sultanahmet Square ().

The word ...

), also supports some of Herodotus' specific reports. George B. Grundy was the first modern historian to do a thorough topographical survey of Thermopylae, and led some modern writers (such as Liddell Hart) to revise their views of certain aspects of the battle. Grundy also explored Plataea

Plataea (; , ''Plátaia'') was an ancient Greek city-state situated in Boeotia near the frontier with Attica at the foot of Mt. Cithaeron, between the mountain and the river Asopus, which divided its territory from that of Thebes. Its inhab ...

and wrote a treatise on that battle.

On the Battle of Thermopylae itself, two principal sources, Herodotus' and Simonides

Simonides of Ceos (; ; c. 556 – 468 BC) was a Greek lyric poet, born in Ioulis on Kea (island), Ceos. The scholars of Hellenistic Alexandria included him in the canonical list of the nine lyric poets esteemed by them as worthy of criti ...

' accounts, survive. Herodotus' account in Book VII of his ''Histories'' is such an important source that Paul Cartledge

Paul Anthony Cartledge (born 24 March 1947)"CARTLEDGE, Prof. Paul Anthony", ''Who's Who 2010'', A & C Black, 2010online edition/ref> is a British ancient historian and academic. From 2008 to 2014 he was the A. G. Leventis Professor of Greek ...

wrote: "we either write a history of Thermopylae with erodotus or not at all". Also surviving is an epitome of the account of Ctesias, by the eighth-century Byzantine Photios, though this is "almost worse than useless", missing key events in the battle such as the betrayal of Ephialtes

Ephialtes (, ''Ephialtēs'') was an ancient Athenian politician and an early leader of the democratic movement there. In the late 460s BC, he oversaw reforms that diminished the power of the Areopagus, a traditional bastion of conservatism, and w ...

, and the account of Diodorus Siculus in his ''Universal History''. Diodorus' account seems to have been based on that of Ephorus and contains one significant deviation from Herodotus' account: a supposed night attack against the Persian camp, of which modern scholars have tended to be skeptical.

Background

Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

and Eretria

Eretria (; , , , , literally 'city of the rowers') is a town in Euboea, Greece, facing the coast of Attica across the narrow South Euboean Gulf. It was an important Greek polis in the 6th and 5th century BC, mentioned by many famous writers ...

had aided the unsuccessful Ionian Revolt

The Ionian Revolt, and associated revolts in Aeolis, Doris (Asia Minor), Doris, Ancient history of Cyprus, Cyprus and Caria, were military rebellions by several Greek regions of Asia Minor against Achaemenid Empire, Persian rule, lasting from 499 ...

against the Persian Empire of Darius I

Darius I ( ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his death in 486 BCE. He ruled the empire at its territorial peak, when it included much of West A ...

in 499–494 BC. The Persian Empire was still relatively young and prone to revolts amongst its subject peoples.Holland, p. 47–55 Darius, moreover, was a

usurper and had spent considerable time extinguishing revolts against his rule.

The Ionian revolt threatened the integrity of his empire, and Darius thus vowed to punish those involved, especially the Athenians, "since he was sure that he Ionianswould not go unpunished for their rebellion". Darius also saw the opportunity to expand his empire into the fractious world of Ancient Greece.Holland, 171–178 A preliminary expedition under Mardonius in 492 BC secured the lands approaching Greece, re-conquered Thrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

, and forced Macedon

Macedonia ( ; , ), also called Macedon ( ), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, which later became the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by the royal ...

to become a client kingdom of Persia.

Darius sent emissaries to all the Greek city-states in 491 BC asking for a gift of " earth and water" as tokens of their submission to him.Holland, pp. 178–179 Having had a demonstration of his power the previous year, the majority of Greek cities duly obliged. In Athens, however, the ambassadors were put on trial and then executed by throwing them in a pit; in Sparta, they were simply thrown down a well. This meant that Sparta was also effectively at war with Persia. However, in order to appease the Persian king somewhat, two Spartans were voluntarily sent to

Darius sent emissaries to all the Greek city-states in 491 BC asking for a gift of " earth and water" as tokens of their submission to him.Holland, pp. 178–179 Having had a demonstration of his power the previous year, the majority of Greek cities duly obliged. In Athens, however, the ambassadors were put on trial and then executed by throwing them in a pit; in Sparta, they were simply thrown down a well. This meant that Sparta was also effectively at war with Persia. However, in order to appease the Persian king somewhat, two Spartans were voluntarily sent to Susa

Susa ( ) was an ancient city in the lower Zagros Mountains about east of the Tigris, between the Karkheh River, Karkheh and Dez River, Dez Rivers in Iran. One of the most important cities of the Ancient Near East, Susa served as the capital o ...

for execution, in atonement for the death of the Persian heralds.

Darius then launched an amphibious expeditionary force under Datis and Artaphernes

Artaphernes (Greek language, Greek: Ἀρταφέρνης, Old Persian language, Old Persian: Artafarna, from Median language, Median ''Rtafarnah''), was influential circa 513–492 BC and was a brother of the Achaemenid king of Persia, Darius I. ...

in 490 BC, which attacked Naxos before receiving the submission of the other Cycladic Islands. It then besieged and destroyed Eretria. Finally, it moved to attack Athens, landing at the bay of Marathon

The marathon is a long-distance foot race with a distance of kilometres ( 26 mi 385 yd), usually run as a road race, but the distance can be covered on trail routes. The marathon can be completed by running or with a run/walk strategy. There ...

, where it was met by a heavily outnumbered Athenian army. At the ensuing Battle of Marathon

The Battle of Marathon took place in 490 BC during the first Persian invasion of Greece. It was fought between the citizens of Athens (polis), Athens, aided by Plataea, and a Achaemenid Empire, Persian force commanded by Datis and Artaph ...

, the Athenians won a remarkable victory, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Persian army to Asia.

At this, Darius began raising a huge new army with which to completely subjugate Greece; however, in 486 BC, his

At this, Darius began raising a huge new army with which to completely subjugate Greece; however, in 486 BC, his Egyptian

''Egyptian'' describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of year ...

province revolted, indefinitely postponing any Greek expedition.Holland, p. 203 Darius died while preparing to march on Egypt, and the throne of Persia passed to his son Xerxes I. Xerxes crushed the Egyptian revolt and quickly restarted preparations for the invasion of Greece.Holland, pp. 208–211 No mere expedition, this was to be a full-scale invasion supported by long-term planning, stockpiling, and conscription. Xerxes directed that the Hellespont

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey t ...

be bridged to allow his army to cross to Europe, and that a canal be dug across the isthmus of Mount Athos

Mount Athos (; ) is a mountain on the Athos peninsula in northeastern Greece directly on the Aegean Sea. It is an important center of Eastern Orthodoxy, Eastern Orthodox monasticism.

The mountain and most of the Athos peninsula are governed ...

(cutting short the route where a Persian fleet had been destroyed in 492 BC). These were both feats of exceptional ambition beyond any other contemporary state.Holland, pp. 213–214 By early 480 BC, the preparations were complete, and the army which Xerxes had mustered at Sardis

Sardis ( ) or Sardes ( ; Lydian language, Lydian: , romanized: ; ; ) was an ancient city best known as the capital of the Lydian Empire. After the fall of the Lydian Empire, it became the capital of the Achaemenid Empire, Persian Lydia (satrapy) ...

marched towards Europe, crossing the Hellespont on two pontoon bridge

A pontoon bridge (or ponton bridge), also known as a floating bridge, is a bridge that uses float (nautical), floats or shallow-draft (hull), draft boats to support a continuous deck for pedestrian and vehicle travel. The buoyancy of the support ...

s. According to Herodotus, Xerxes' army was so large that, upon arriving at the banks of the Echeidorus River, his soldiers proceeded to drink it dry. In the face of such imposing numbers, many Greek cities capitulated to the Persian demand for a tribute of earth and water.

The Athenians had also been preparing for war with the Persians since the mid-480s BC, and in 482 BC the decision was taken, under the strategic guidance of the Athenian politician Themistocles

Themistocles (; ; ) was an Athenian politician and general. He was one of a new breed of non-aristocratic politicians who rose to prominence in the early years of the Athenian democracy. As a politician, Themistocles was a populist, having th ...

, to build a massive fleet of trireme

A trireme ( ; ; cf. ) was an ancient navies and vessels, ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizations of the Mediterranean Sea, especially the Phoenicians, ancient Greece, ancient Greeks and ancient R ...

s to resist the Persians.Holland, p. 217–223 However, the Athenians lacked the manpower to fight on both land and sea, requiring reinforcements from other Greek city-states. In 481 BC, Xerxes sent ambassadors around Greece requesting "earth and water" but very deliberately omitting Athens and Sparta. Support thus began to coalesce around these two leading cities. A congress met at Corinth

Corinth ( ; , ) is a municipality in Corinthia in Greece. The successor to the ancient Corinth, ancient city of Corinth, it is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Sin ...

in late autumn of 481 BC,HerodotuVII, 145

and a confederate alliance of

Greek city-states

Polis (: poleis) means 'city' in Ancient Greek. The ancient word ''polis'' had socio-political connotations not possessed by modern usage. For example, Modern Greek πόλη (polē) is located within a (''khôra''), "country", which is a πατ ...

was formed. It had the power to send envoys to request assistance and dispatch troops from the member states to defensive points, after joint consultation. This was remarkable for the disjointed and chaotic Greek world, especially since many of the supposed allies were still technically at war with each other.Holland, p. 226

The congress met again in the spring of 480 BC. A Thessalian

Thessaly ( ; ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thessaly was known as Aeolia (, ), and appea ...

delegation suggested that the Greeks could muster in the narrow Vale of Tempe

The Vale of Tempe or Tembi (; ; ) is a gorge in the Tempi municipality of northern Thessaly, Greece, located between Olympus to the north and Ossa to the south, and between the regions of Thessaly and Macedonia. The gorge was known to the Byz ...

, on the borders of Thessaly, and thereby block Xerxes' advance.Holland, pp. 248–249 A force of 10,000 hoplite

Hoplites ( ) ( ) were citizen-soldiers of Ancient Greek city-states who were primarily armed with spears and shields. Hoplite soldiers used the phalanx formation to be effective in war with fewer soldiers. The formation discouraged the sold ...

s was dispatched to the Vale of Tempe, through which they believed the Persian army would have to pass. However, once there, being warned by Alexander I of Macedon that the vale could be bypassed through Sarantoporo Pass and that Xerxes' army was overwhelming, the Greeks retreated.HerodotuVII, 173

Shortly afterwards, they received the news that Xerxes had crossed the Hellespont. Themistocles, therefore, suggested a second strategy to the Greeks: the route to southern Greece (Boeotia, Attica, and the Peloponnesus) would require Xerxes' army to travel through the very narrow pass of

Thermopylae

Thermopylae (; ; Ancient: , Katharevousa: ; ; "hot gates") is a narrow pass and modern town in Lamia (city), Lamia, Phthiotis, Greece. It derives its name from its Mineral spring, hot sulphur springs."Thermopylae" in: S. Hornblower & A. Spaw ...

, which could easily be blocked by the Greek hoplites, jamming up the overwhelming force of Persians.Holland, pp. 255–257 Furthermore, to prevent the Persians from bypassing Thermopylae by sea, the Athenian and allied navies could block the straits of Artemisium. Congress adopted this dual-pronged strategy. However, in case of Persian breakthrough, the Peloponnesian cities made fall-back plans to defend the Isthmus of Corinth

The Isthmus of Corinth ( Greek: Ισθμός της Κορίνθου) is the narrow land bridge which connects the Peloponnese peninsula with the rest of the mainland of Greece, near the city of Corinth. The wide Isthmus was known in the a ...

, while the women and children of Athens would evacuate ''en masse'' to the Peloponnesian city of Troezen

Troezen (; ancient Greek: Τροιζήν, modern Greek: Τροιζήνα ) is a small town and a former municipality in the northeastern Peloponnese, Greece, on the Argolid Peninsula. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the munic ...

.

Prelude

The Persian army seems to have made slow progress through Thrace and Macedon. News of the imminent Persian approach eventually reached Greece in August thanks to a Greek spy. At this time of the year, the Spartans, ''de facto'' military leaders of the alliance, were celebrating the festival of Carneia. During the Carneia, military activity was forbidden by Spartan law; the Spartans had arrived too late at the Battle of Marathon because of this requirement.Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

br>VII, 206/ref> It was also the time of the

Olympic Games

The modern Olympic Games (Olympics; ) are the world's preeminent international Olympic sports, sporting events. They feature summer and winter sports competitions in which thousands of athletes from around the world participate in a Multi-s ...

, and therefore the Olympic truce, and thus it would have been doubly sacrilegious for the whole Spartan army to march to war.Holland, pp. 258–259. On this occasion, the ephor

The ephors were a board of five magistrates in ancient Sparta. They had an extensive range of judicial, religious, legislative, and military powers, and could shape Sparta's home and foreign affairs.

The word "''ephors''" (Ancient Greek ''éph ...

s decided the urgency was sufficiently great to justify an advance expedition to block the pass, under one of its kings, Leonidas I

Leonidas I (; , ''Leōnídas''; born ; died 11 August 480 BC) was king of the Ancient Greek city-state of Sparta. He was the son of king Anaxandridas II and the 17th king of the Agiad dynasty, a Spartan royal house which claimed descent fro ...

. Leonidas took with him the 300 men of the royal bodyguard, the ''Hippeis''. This expedition was to try to gather as many other Greek soldiers along the way as possible and to await the arrival of the main Spartan army.

The renowned account of the Battle of Thermopylae, as documented by Herodotus, includes a significant consultation with the Oracle at Delphi

Pythia (; ) was the title of the high priestess of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi. She specifically served as its oracle and was known as the Oracle of Delphi. Her title was also historically glossed in English as the Pythoness.

The Pythia w ...

. It is said that the Oracle delivered a prophetic message to the Spartans, foretelling the impending conflict:

Herodotus tells us that Leonidas, in line with the prophecy, was convinced he was going to certain death since his forces were not adequate for a victory, and so he selected only Spartans with living sons.HerodotuVII, 205

The Spartan force was reinforced ''en route'' to Thermopylae by contingents from various cities and numbered more than 7,000 by the time it arrived at the pass. Leonidas chose to camp at, and defend, the "middle gate", the narrowest part of the pass of Thermopylae, where the Phocians had built a defensive wall some time before. News also reached Leonidas, from the nearby city of Trachis, that there was a mountain track that could be used to outflank the pass of Thermopylae. Leonidas stationed 1,000 Phocians on the heights to prevent such a manoeuvre.Herodotu

VII, 217

/ref> Finally, in mid-August, the Persian army was sighted across the Malian Gulf approaching Thermopylae. With the Persian army's arrival at Thermopylae the Greeks held a council of war. Some Peloponnesians suggested withdrawal to the Isthmus of Corinth and blocking the passage to Peloponnesus. The Phocians and Locrians, whose states were located nearby, became indignant and advised defending Thermopylae and sending for more help. Leonidas calmed the panic and agreed to defend Thermopylae.Herodotu

VII, 207

According to Plutarch, when one of the soldiers complained that, "Because of the arrows of the barbarians it is impossible to see the sun", Leonidas replied, "Won't it be nice, then, if we shall have shade in which to fight them?" Herodotus reports a similar comment, but attributes it to Dienekes. Xerxes sent a Persian emissary to negotiate with Leonidas. The Greeks were offered their freedom, the title "Friends of the Persian People", and the opportunity to re-settle on land better than that they possessed.Holland, pp. 270–271 When Leonidas refused these terms, the ambassador carried a written message by Xerxes, asking him to "Hand over your arms". Leonidas' famous response to the Persians was ''" Molṑn labé"'' (Μολὼν λαβέ – literally, "having come, take

hem

A hem in sewing is a garment finishing method, where the edge of a piece of cloth is folded and sewn to prevent unravelling of the fabric and to adjust the length of the piece in garments, such as at the end of the sleeve or the bottom of the ga ...

, but usually translated as "come and take them"). With the Persian emissary returning empty-handed, battle became inevitable. Xerxes delayed for four days, waiting for the Greeks to disperse, before sending troops to attack them.

Opposing forces

Persian army

The number of troops which Xerxes mustered for the second invasion of Greece has been the subject of endless dispute, most notably between ancient sources, which report very large numbers, and modern scholars, who surmise much smaller figures. Herodotus claimed that there were, in total, 2.6 million military personnel, accompanied by an equivalent number of support personnel.Herodotu

The number of troops which Xerxes mustered for the second invasion of Greece has been the subject of endless dispute, most notably between ancient sources, which report very large numbers, and modern scholars, who surmise much smaller figures. Herodotus claimed that there were, in total, 2.6 million military personnel, accompanied by an equivalent number of support personnel.HerodotuVII, 186

The poet

Simonides

Simonides of Ceos (; ; c. 556 – 468 BC) was a Greek lyric poet, born in Ioulis on Kea (island), Ceos. The scholars of Hellenistic Alexandria included him in the canonical list of the nine lyric poets esteemed by them as worthy of criti ...

, who was a contemporary, talks of four million; Ctesias

Ctesias ( ; ; ), also known as Ctesias of Cnidus, was a Greek physician and historian from the town of Cnidus in Caria, then part of the Achaemenid Empire.

Historical events

Ctesias, who lived in the fifth century BC, was physician to the Acha ...

gave 800,000 as the total number of the army that was assembled by Xerxes.

Modern scholars tend to reject the figures given by Herodotus and other ancient sources as unrealistic, resulting from miscalculations or exaggerations on the part of the victors.Holland, p. 237 Modern scholarly estimates are generally in the range 120,000 to 300,000.Holland, p. 394. These estimates usually come from studying the logistical capabilities of the Persians in that era, the sustainability of their respective bases of operations, and the overall manpower constraints affecting them. Whatever the real numbers were, however, it is clear that Xerxes was anxious to ensure a successful expedition by mustering an overwhelming numerical superiority by land and by sea.de Souza, p. 41.

The number of Persian troops present at Thermopylae is therefore as uncertain as the number for the total invasion force. For instance, it is unclear whether the whole Persian army marched as far as Thermopylae, or whether Xerxes left garrisons in Macedon and Thessaly.

Greek army

According to HerodotusHerodotusVII, 202

Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

br>VII, 203and Diodorus Siculus,Diodorus Siculu

XI, 4

the Greek army included the following forces: Notes: * The number of Peloponnesians :Diodorus suggests that there were 1,000 Lacedemonians and 3,000 other Peloponnesians, totalling 4,000. Herodotus agrees with this figure in one passage, quoting an inscription by

Simonides

Simonides of Ceos (; ; c. 556 – 468 BC) was a Greek lyric poet, born in Ioulis on Kea (island), Ceos. The scholars of Hellenistic Alexandria included him in the canonical list of the nine lyric poets esteemed by them as worthy of criti ...

saying there were 4,000 Peloponnesians.HerodotuVII, 228

However, elsewhere, in the passage summarised by the above table, Herodotus tallies 3,100 Peloponnesians at Thermopylae before the battle. Herodotus also reports that at Xerxes' public showing of the dead, "helots were also there for them to see",Herodotu

VIII, 25

but he does not say how many or in what capacity they served. Thus, the difference between his two figures can be squared by supposing (without proof) that there were 900 helots (three per Spartan) present at the battle.Macan, note to Herodotus VIII, 25 If helots were present at the battle, there is no reason to doubt that they served in their traditional role as armed retainers to individual Spartans. Alternatively, Herodotus' "missing" 900 troops might have been

Perioeci

The Perioeci or Perioikoi (, ) were the second-tier citizens of the ''polis'' of Sparta until 200 BC. They lived in several dozen cities within Spartan territories (mostly Laconia and Messenia), which were dependent on Sparta. The ''perioeci'' ...

, and could therefore correspond to Diodorus' 1,000 Lacedemonians.

* The number of Lacedemonians

: Further confusing the issue is Diodorus' ambiguity about whether his count of 1,000 Lacedemonians included the 300 Spartans. At one point he says: "Leonidas, when he received the appointment, announced that only one thousand men should follow him on the campaign". However, he then says: "There were, then, of the Lacedemonians one thousand, and with them three hundred Spartiates". It is therefore impossible to be clearer on this point.

Pausanias' account agrees with that of Herodotus (whom he probably read) except that he gives the number of Locrians, which Herodotus declined to estimate. Residing in the direct path of the Persian advance, they gave all the fighting men they had – according to Pausanias 6,000 men – which added to Herodotus' 5,200 would have given a force of 11,200.

Many modern historians, who usually consider Herodotus more reliable,Green, p. 140 add the 1,000 Lacedemonians and the 900 helots to Herodotus' 5,200 to obtain 7,100 or about 7,000 men as a standard number, neglecting Diodorus' Melians and Pausanias' Locrians.Bury, pp. 271–282 However, this is only one approach, and many other combinations are plausible. Furthermore, the numbers changed later on in the battle when most of the army retreated and only approximately 3,000 men remained (300 Spartans, 700 Thespians, 400 Thebans, possibly up to 900 helots, and 1,000 Phocians stationed above the pass, less the casualties sustained in the previous days).

Further confusing the issue is Diodorus' ambiguity about whether his count of 1,000 Lacedemonians included the 300 Spartans. At one point he says: "Leonidas, when he received the appointment, announced that only one thousand men should follow him on the campaign". However, he then says: "There were, then, of the Lacedemonians one thousand, and with them three hundred Spartiates". It is therefore impossible to be clearer on this point.

Pausanias' account agrees with that of Herodotus (whom he probably read) except that he gives the number of Locrians, which Herodotus declined to estimate. Residing in the direct path of the Persian advance, they gave all the fighting men they had – according to Pausanias 6,000 men – which added to Herodotus' 5,200 would have given a force of 11,200.

Many modern historians, who usually consider Herodotus more reliable,Green, p. 140 add the 1,000 Lacedemonians and the 900 helots to Herodotus' 5,200 to obtain 7,100 or about 7,000 men as a standard number, neglecting Diodorus' Melians and Pausanias' Locrians.Bury, pp. 271–282 However, this is only one approach, and many other combinations are plausible. Furthermore, the numbers changed later on in the battle when most of the army retreated and only approximately 3,000 men remained (300 Spartans, 700 Thespians, 400 Thebans, possibly up to 900 helots, and 1,000 Phocians stationed above the pass, less the casualties sustained in the previous days).

Strategic and tactical considerations

phalanx

The phalanx (: phalanxes or phalanges) was a rectangular mass military formation, usually composed entirely of heavy infantry armed with spears, pikes, sarissas, or similar polearms tightly packed together. The term is particularly used t ...

could block the narrow pass with ease, with no risk of being outflanked by cavalry. Moreover, in the pass, the phalanx would have been very difficult to assault for the more lightly armed Persian infantry. The major weak point for the Greeks was the mountain track which led across the highland parallel to Thermopylae, that could allow their position to be outflanked. Although probably unsuitable for cavalry, this path could easily be traversed by the Persian infantry (many of whom were versed in mountain warfare

Mountain warfare or alpine warfare is warfare in mountains or similarly rough terrain. The term encompasses military operations affected by the terrain, hazards, and factors of combat and movement through rough terrain, as well as the strategies ...

).Holland, p 288 Leonidas was made aware of this path by local people from Trachis, and he positioned a detachment of Phocian troops there in order to block this route.Holland, pp. 262–264

Topography of the battlefield

It is often claimed that at the time, the pass of Thermopylae consisted of a track along the shore of the Malian Gulf so narrow that only one chariot could pass through at a time. In fact, as noted below, the pass was 100 metres wide, probably wider than the Greeks could have held against the Persian masses. Herodotus reports that the Phocians had improved the defences of the pass by channelling the stream from the hot springs to create a marsh, and it was a causeway across this marsh which was only wide enough for a single chariot to traverse. In a later passage, describing a Gaulish attempt to force the pass, Pausanias states "The cavalry on both sides proved useless, as the ground at the Pass is not only narrow, but also smooth because of the natural rock, while most of it is slippery owing to its being covered with streams...the losses of the barbarians it was impossible to discover exactly. For the number of them that disappeared beneath the mud was great." On the north side of the roadway was the Malian Gulf, into which the land shelved gently. When at a later date, an army of Gauls led by Brennus attempted to force the pass, the shallowness of the water gave the Greek fleet great difficulty getting close enough to the fighting to bombard the Gauls with ship-borne missile weapons. Along the path itself was a series of three constrictions, or "gates" (''pylai''), and at the centre gate a wall that had been erected by the Phocians, in the previous century, to aid in their defence againstThessalian

Thessaly ( ; ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thessaly was known as Aeolia (, ), and appea ...

invasions.HerodotuVII, 176

The name "Hot Gates" comes from the

hot spring

A hot spring, hydrothermal spring, or geothermal spring is a Spring (hydrology), spring produced by the emergence of Geothermal activity, geothermally heated groundwater onto the surface of the Earth. The groundwater is heated either by shallow ...

s that were located there.HerodotuVIII, 201

The terrain of the battlefield was nothing that Xerxes and his forces were accustomed to. Although coming from a mountainous country, the Persians were not prepared for the real nature of the country they had invaded. The pure ruggedness of this area is caused by torrential downpours for four months of the year, combined with an intense summer season of scorching heat that cracks the ground. Vegetation is scarce and consists of low, thorny shrubs. The hillsides along the pass are covered in thick brush, with some plants reaching high. With the sea on one side and steep, impassable hills on the other, King Leonidas and his men chose the perfect topographical position to battle the Persian invaders. Today, the pass is not near the sea, but is several kilometres inland because of

sedimentation

Sedimentation is the deposition of sediments. It takes place when particles in suspension settle out of the fluid in which they are entrained and come to rest against a barrier. This is due to their motion through the fluid in response to th ...

in the Malian Gulf. The old track appears at the foot of the hills around the plain, flanked by a modern road. Recent core sample

A core sample is a cylindrical section of (usually) a naturally-occurring substance. Most core samples are obtained by drilling with special drills into the substance, such as sediment or rock, with a hollow steel tube, called a core drill. The ...

s indicate that the pass was only wide, and the waters came up to the gates: "Little do the visitors realize that the battle took place across the road from the monument." The pass still is a natural defensive position to modern armies, and forces of the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

in the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

made a defence in 1941 against the invasion by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

mere metres from the original battlefield.

* Maps of the region:

* Image of the battlefield, from the east

Battle

First day

On the fifth day after the Persian arrival at Thermopylae and the first day of the battle, Xerxes finally resolved to attack the Greeks. First, he ordered 5,000 archers to shoot a barrage of arrows, but they were ineffective; they shot from at least 100 yards away, according to modern day scholars, and the Greeks' wooden shields (sometimes covered with a very thin layer of bronze) and bronze helmets deflected the arrows.

After that, Xerxes sent a force of 10,000

On the fifth day after the Persian arrival at Thermopylae and the first day of the battle, Xerxes finally resolved to attack the Greeks. First, he ordered 5,000 archers to shoot a barrage of arrows, but they were ineffective; they shot from at least 100 yards away, according to modern day scholars, and the Greeks' wooden shields (sometimes covered with a very thin layer of bronze) and bronze helmets deflected the arrows.

After that, Xerxes sent a force of 10,000 Medes

The Medes were an Iron Age Iranian peoples, Iranian people who spoke the Median language and who inhabited an area known as Media (region), Media between western Iran, western and northern Iran. Around the 11th century BC, they occupied the m ...

and Cissians to take the defenders prisoner and bring them before him.HerodotuVII, 210

Diodorus Siculu

XI, 6

The Persians soon launched a

frontal assault

A frontal assault is a military tactic which involves a direct, full-force attack on the front line of an enemy force, rather than to the flanks or rear of the enemy. It allows for a quick and decisive victory, but at the cost of subjecting the a ...

, in waves of around 10,000 men, on the Greek position. The Greeks fought in front of the Phocian wall, at the narrowest part of the pass, which enabled them to use as few soldiers as possible.HerodotuVII, 208

Details of the tactics are scant; Diodorus says, "the men stood shoulder to shoulder", and the Greeks were "superior in valour and in the great size of their shields."Diodorus Siculu

XI, 7

This probably describes the standard Greek phalanx, in which the men formed a wall of overlapping shields and layered spear points protruding out from the sides of the shields, which would have been highly effective as long as it spanned the width of the pass. The weaker shields, and shorter spears and swords of the Persians prevented them from effectively engaging the Greek hoplites.Herodotu

VII, 211.1

211.2

, an

211.3

. Herodotus says that the units for each city were kept together; units were rotated in and out of the battle to prevent fatigue, which implies the Greeks had more men than necessary to block the pass.Herodotu

VII, 204

The Greeks killed so many Medes that Xerxes is said to have stood up three times from the seat from which he was watching the battle.Herodotu

VII, 212

According to Ctesias, the first wave was "cut to ribbons", with only two or three Spartans killed in return. According to Herodotus and Diodorus, Xerxes, having taken the measure of the enemy, threw his best troops into a second assault the same day, the Immortals, an elite corps of 10,000 men. However, the Immortals fared no better than the Medes, and failed to make any headway against the Greeks. The Spartans reportedly used a tactic of feigning retreat, and then turning and killing the enemy troops when they ran after them.

Second day

On the second day Xerxes again sent in the infantry to attack the pass, "supposing that their enemies, being so few, were now disabled by wounds and could no longer resist." However, the Persians had no more success on the second day than on the first. Xerxes at last stopped the assault and withdrew to his camp, "totally perplexed". Later that day, however, as Xerxes was pondering what to do next, he received a windfall; a Trachinian named Ephialtes informed him of the mountain path around Thermopylae and offered to guide the Persian army. Ephialtes was motivated by the desire for a reward.HerodotuVII, 213

For this act, the name "Ephialtes" received a lasting stigma; it came to mean "nightmare" in the Greek language and to symbolise the archetypal traitor in Greek culture. Herodotus reports that Xerxes sent his commander

Hydarnes

Hydarnes (), also known as Hydarnes the Elder, was a Persian nobleman, who was one of the seven conspirators who overthrew the Pseudo-Smerdis. His name is the Greek transliteration of the Old Persian name , which may have meant "he who knows the ...

that evening, with the men under his command, the Immortals, to encircle the Greeks via the path. However, he does not say who those men were. The Immortals had been bloodied on the first day, so it is possible that Hydarnes may have been given overall command of an enhanced force including what was left of the Immortals; according to Diodorus, Hydarnes had a force of 20,000 for the mission. The path led from east of the Persian camp along the ridge of Mt. Anopaea behind the cliffs that flanked the pass. It branched, with one path leading to Phocis and the other down to the Malian Gulf at Alpenus, the first town of Locris.

Third day

At daybreak on the third day, the Phocians guarding the path above Thermopylae became aware of the outflanking Persian column by the rustling of oak leaves. Herodotus says they jumped up and were greatly amazed.Herodotu

At daybreak on the third day, the Phocians guarding the path above Thermopylae became aware of the outflanking Persian column by the rustling of oak leaves. Herodotus says they jumped up and were greatly amazed.HerodotuVII, 218

Hydarnes was perhaps just as amazed to see them hastily arming themselves as they were to see him and his forces.Holland, p. 291–293 He feared they were Spartans but was informed by Ephialtes that they were not. The Phocians retreated to a nearby hill to make their stand (assuming the Persians had come to attack them). However, not wishing to be delayed, the Persians merely shot a volley of arrows at them, before bypassing them to continue with their

encirclement

Encirclement is a military term for the situation when a force or target is isolated and surrounded by enemy forces. The situation is highly dangerous for the encircled force. At the military strategy, strategic level, it cannot receive Milit ...

of the main Greek force.

Learning from a runner that the Phocians had not held the path, Leonidas called a council of war

A council of warCymaean by birth, warned the Greeks. Some of the Greeks argued for withdrawal, but Leonidas resolved to stay at the pass with the Spartans. Upon discovering that his army had been encircled, Leonidas told his allies that they could leave if they wanted to. While many of the Greeks took him up on his offer and fled, around 2,000 soldiers stayed behind to fight and die. Knowing that the end was near, the Greeks marched into the open field and met the Persians head-on. Many of the Greek contingents then either chose to withdraw (without orders) or were ordered to leave by Leonidas (Herodotus admits that there is some doubt about which actually happened).Herodotu

VII, 219

The contingent of 700 Thespians, led by their general Demophilus, refused to leave and committed themselves to the fight.Herodotu

VII, 222

Also present were the 400 Thebans and probably the At dawn, Xerxes made

At dawn, Xerxes made

VII, 223

A Persian force of 10,000 men, comprising light infantry and cavalry, charged at the front of the Greek formation. The Greeks this time sallied forth from the wall to meet the Persians in the wider part of the pass, in an attempt to slaughter as many Persians as they could. They fought with spears, until every spear was shattered, and then switched to '' xiphē'' (short swords). In this struggle, Herodotus states that two of Xerxes' brothers fell:

VII, 224

As the Immortals approached, the Greeks withdrew and took a stand on a hill behind the wall. The Thebans "moved away from their companions, and with hands upraised, advanced toward the barbarians..." (Rawlinson translation), but a few were slain before their surrender was accepted. The king later had the Theban prisoners branded with the royal mark.Herodotu

VII 233

Of the remaining defenders, Herodotus says:

VIII, 24

The Greek rearguard, meanwhile, was annihilated, with a probable loss of 2,000 men, including those killed on the first two days of battle. Herodotus says, at one point 4,000 Greeks died, but assuming the Phocians guarding the track were not killed during the battle (as Herodotus implies), this would be almost every Greek soldier present (by Herodotus' own estimates), and this number is probably too high.

After the Persians' departure, the Greeks collected their dead and buried them on the hill. A full 40 years after the battle, Leonidas' bones were returned to Sparta, where he was buried again with full honours; funeral games were held every year in his memory.

With Thermopylae now opened to the Persian army, the continuation of the blockade at Artemisium by the Greek fleet became irrelevant. The simultaneous naval Battle of Artemisium had been a tactical stalemate, and the Greek navy was able to retreat in good order to the

After the Persians' departure, the Greeks collected their dead and buried them on the hill. A full 40 years after the battle, Leonidas' bones were returned to Sparta, where he was buried again with full honours; funeral games were held every year in his memory.

With Thermopylae now opened to the Persian army, the continuation of the blockade at Artemisium by the Greek fleet became irrelevant. The simultaneous naval Battle of Artemisium had been a tactical stalemate, and the Greek navy was able to retreat in good order to the  Following Thermopylae, the Persian army proceeded to sack and burn Plataea and Thespiae, the Boeotian cities that had not submitted, before it marched on the now evacuated city of Athens and accomplished the Achaemenid destruction of Athens. Meanwhile, the Greeks (for the most part Peloponnesians) preparing to defend the Isthmus of Corinth, demolished the single road that led through it and built a wall across it. As at Thermopylae, making this an effective strategy required the Greek navy to stage a simultaneous blockade, barring the passage of the Persian navy across the Saronic Gulf, so that troops could not be landed directly on the Peloponnese.Holland, pp. 299–303 However, instead of a mere blockade, Themistocles persuaded the Greeks to seek a decisive victory against the Persian fleet. Luring the Persian navy into the Straits of Salamis, the Greek fleet was able to destroy much of the Persian fleet in the

Following Thermopylae, the Persian army proceeded to sack and burn Plataea and Thespiae, the Boeotian cities that had not submitted, before it marched on the now evacuated city of Athens and accomplished the Achaemenid destruction of Athens. Meanwhile, the Greeks (for the most part Peloponnesians) preparing to defend the Isthmus of Corinth, demolished the single road that led through it and built a wall across it. As at Thermopylae, making this an effective strategy required the Greek navy to stage a simultaneous blockade, barring the passage of the Persian navy across the Saronic Gulf, so that troops could not be landed directly on the Peloponnese.Holland, pp. 299–303 However, instead of a mere blockade, Themistocles persuaded the Greeks to seek a decisive victory against the Persian fleet. Luring the Persian navy into the Straits of Salamis, the Greek fleet was able to destroy much of the Persian fleet in the

VIII, 97

though nearly all of them died of starvation and disease on the return voyage.Herodotu

VIII, 115

He left a hand-picked force, under Mardonius, to complete the conquest the following year. However, under pressure from the Athenians, the Peloponnesians eventually agreed to try to force Mardonius to battle, and they marched on Attica. Mardonius retreated to Boeotia to lure the Greeks into open terrain, and the two sides eventually met near the city of Plataea.Holland, pp. 338–341 At the Thermopylae is one of the most famous battles in European ancient history, repeatedly referenced in ancient, recent, and contemporary culture. In Western culture at least, it is the Greeks who are lauded for their performance in battle.Holland, p. ''xviii''. However, within the context of the Persian invasion, Thermopylae was undoubtedly a defeat for the Greeks.Lazenby, p. 151. It seems clear that the Greek strategy was to hold off the Persians at Thermopylae and Artemisium; whatever they may have intended, it was presumably not their desire to surrender all of Boeotia and Attica to the Persians. The Greek position at Thermopylae, despite being massively outnumbered, was nearly impregnable. If the position had been held for even a little longer, the Persians might have had to retreat for lack of food and water. Thus, despite the heavy losses, forcing the pass was strategically a Persian victory, but the successful retreat of the bulk of the Greek troops was in its own sense a victory as well. The battle itself had shown that even when heavily outnumbered, the Greeks could put up an effective fight against the Persians, and the defeat at Thermopylae had turned Leonidas and the men under his command into martyrs. That boosted the morale of all Greek soldiers in the second Persian invasion.

It is sometimes stated that Thermopylae was a

Thermopylae is one of the most famous battles in European ancient history, repeatedly referenced in ancient, recent, and contemporary culture. In Western culture at least, it is the Greeks who are lauded for their performance in battle.Holland, p. ''xviii''. However, within the context of the Persian invasion, Thermopylae was undoubtedly a defeat for the Greeks.Lazenby, p. 151. It seems clear that the Greek strategy was to hold off the Persians at Thermopylae and Artemisium; whatever they may have intended, it was presumably not their desire to surrender all of Boeotia and Attica to the Persians. The Greek position at Thermopylae, despite being massively outnumbered, was nearly impregnable. If the position had been held for even a little longer, the Persians might have had to retreat for lack of food and water. Thus, despite the heavy losses, forcing the pass was strategically a Persian victory, but the successful retreat of the bulk of the Greek troops was in its own sense a victory as well. The battle itself had shown that even when heavily outnumbered, the Greeks could put up an effective fight against the Persians, and the defeat at Thermopylae had turned Leonidas and the men under his command into martyrs. That boosted the morale of all Greek soldiers in the second Persian invasion.

It is sometimes stated that Thermopylae was a

IX, 1

Alternatively, the argument is sometimes advanced that the last stand at Thermopylae was a successful delaying action that gave the Greek navy time to prepare for the Battle of Salamis. However, compared to the probable time (about one month) between Thermopylae and Salamis, the time bought was negligible. Furthermore, this idea also neglects the fact that a Greek navy was fighting at Artemisium during the Battle of Thermopylae, incurring losses in the process. George Cawkwell suggests that the gap between Thermopylae and Salamis was caused by Xerxes' systematically reducing Greek opposition in Phocis and Boeotia, and not as a result of the Battle of Thermopylae; thus, as a delaying action, Thermopylae was insignificant compared to Xerxes' own procrastination. Far from labelling Thermopylae as a Pyrrhic victory, modern academic treatises on the Graeco-Persian Wars tend to emphasise the success of Xerxes in breaching the formidable Greek position and the subsequent conquest of the majority of Greece. For instance, Cawkwell states: "he was successful on both land and sea, and the Great Invasion began with a brilliant success. ... Xerxes had every reason to congratulate himself", while Lazenby describes the Greek defeat as "disastrous". The fame of Thermopylae is thus principally derived not from its effect on the outcome of the war but for the inspirational example it set. Thermopylae is famous because of the heroism of the doomed rearguard, who, despite facing certain death, remained at the pass. Ever since, the events of Thermopylae have been the source of effusive praise from many sources: "Salamis, Plataea, Mycale and Sicily are the fairest sister-victories which the Sun has ever seen, yet they would never dare to compare their combined glory with the glorious defeat of King Leonidas and his men". A second reason is the example it set of free men, fighting for their country and their freedom:

A well-known

A well-known

In 1997 a second monument was officially unveiled by the Greek government, dedicated to the 700 Thespians who fought with the Spartans The monument is made of marble and features a bronze statue depicting the god

In 1997 a second monument was officially unveiled by the Greek government, dedicated to the 700 Thespians who fought with the Spartans The monument is made of marble and features a bronze statue depicting the god