The Bank of England is the

central bank

A central bank, reserve bank, national bank, or monetary authority is an institution that manages the monetary policy of a country or monetary union. In contrast to a commercial bank, a central bank possesses a monopoly on increasing the mo ...

of the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the

English Government's banker and debt manager, and still one of the bankers for the

government of the United Kingdom

His Majesty's Government, abbreviated to HM Government or otherwise UK Government, is the central government, central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. , it is the world's second oldest central bank.

The bank was privately owned by stockholders from its foundation in 1694 until it was nationalised in 1946 by the

Attlee ministry

Clement Attlee was invited by King George VI to form the first Attlee ministry in the United Kingdom on 26 July 1945, succeeding Winston Churchill as prime minister of the United Kingdom. The Labour Party (UK), Labour Party had won a landslide ...

. In 1998 it became an independent public organisation, wholly owned by the

Treasury Solicitor

The Government Legal Department (previously called the Treasury Solicitor's Department) is the largest in-house legal organisation in the United Kingdom's Government Legal Profession.

The department is headed by the Treasury Solicitor (formall ...

on behalf of the government,

with a mandate to support the economic policies of the government of the day, but independence in maintaining price stability. In the 21st century the bank took on increased responsibility for maintaining and monitoring

financial stability

Financial stability is the absence of system-wide episodes in which a financial crisis occurs and is characterised as an economy with Volatility (finance), low volatility. It also involves financial systems' stress-resilience being able to cope wi ...

in the UK, and it increasingly functions as a statutory

regulator.

The bank's headquarters have been in London's main financial district, the

City of London

The City of London, also known as ''the City'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and Districts of England, local government district with City status in the United Kingdom, city status in England. It is the Old town, his ...

, since 1694, and on

Threadneedle Street since 1734. It is sometimes known as "The Old Lady of Threadneedle Street", a name taken from a satirical cartoon by

James Gillray

James Gillray (13 August 1756Gillray, James and Draper Hill (1966). ''Fashionable contrasts''. Phaidon. p. 8.Baptism register for Fetter Lane (Moravian) confirms birth as 13 August 1756, baptism 17 August 1756 1June 1815) was a British list of c ...

in 1797. The road junction outside is known as

Bank Junction.

The bank, among other things, is custodian to the official

gold reserves of the United Kingdom (and those of around 30 other countries). , the bank held around of gold, worth £141 billion. These estimates suggest that the vault could hold as much as 3% of the 171,300 tonnes of gold mined throughout human history.

Functions

According to its

strapline

Advertising slogans are short phrases used in advertising campaigns to generate publicity and unify a company's marketing strategy. The phrases may be used to attract attention to a distinctive product feature or reinforce a company's brand.

Etymo ...

, the bank's core purpose is 'promoting the good of the people of the United Kingdom by maintaining monetary and financial stability'.

This is achieved in a variety of ways:

Monetary stability

Stable prices and secure forms of payment are the two main criteria for monetary stability.

Stable prices

Stable prices are maintained by seeking to ensure that price increases meet the Government's inflation target. The bank aims to meet this target by adjusting the base

interest rate

An interest rate is the amount of interest due per period, as a proportion of the amount lent, deposited, or borrowed (called the principal sum). The total interest on an amount lent or borrowed depends on the principal sum, the interest rate, ...

(known as the

bank rate

Bank rate, also known as discount rate in American English, and (familiarly) the base rate in British English, is the rate of interest which a central bank charges on its loans and advances to a commercial bank. The bank rate is known by a numb ...

), which is decided by the bank's

Monetary Policy Committee (MPC). (The MPC has devolved responsibility for managing

monetary policy

Monetary policy is the policy adopted by the monetary authority of a nation to affect monetary and other financial conditions to accomplish broader objectives like high employment and price stability (normally interpreted as a low and stable rat ...

;

HM Treasury

His Majesty's Treasury (HM Treasury or HMT), and informally referred to as the Treasury, is the Government of the United Kingdom’s economic and finance ministry. The Treasury is responsible for public spending, financial services policy, Tax ...

has reserve powers to give orders to the committee "if they are required in the public interest and by extreme economic circumstances", but Parliament must endorse such orders within 28 days.)

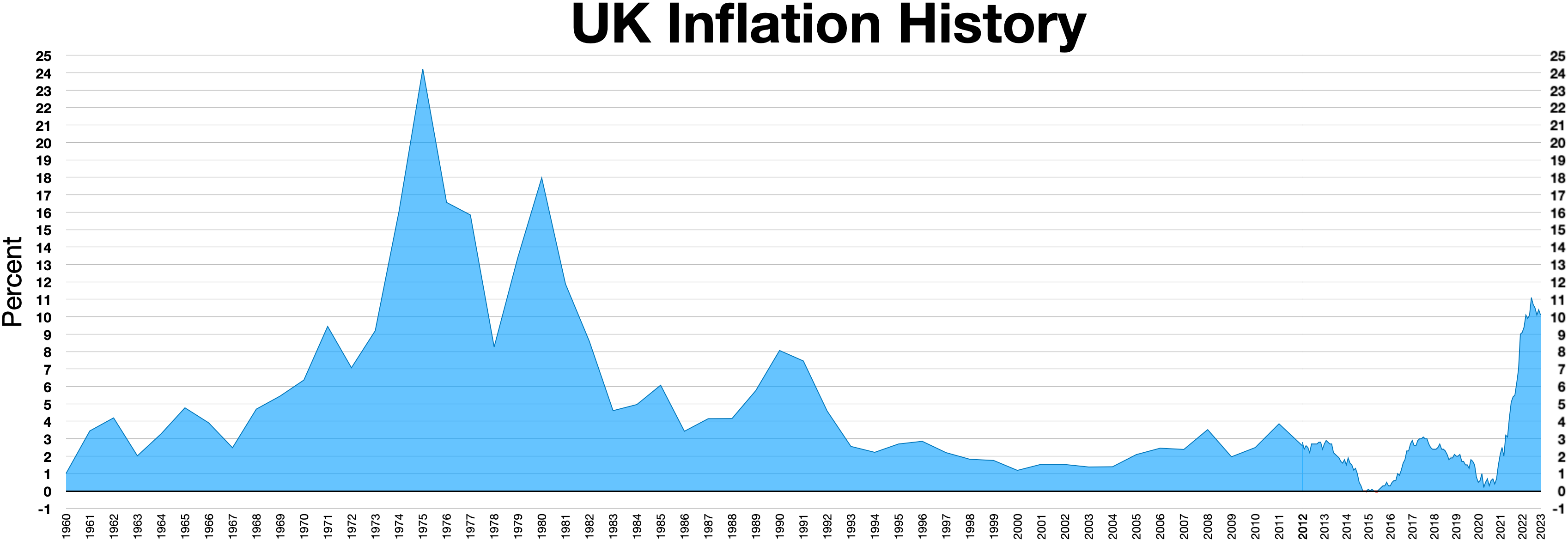

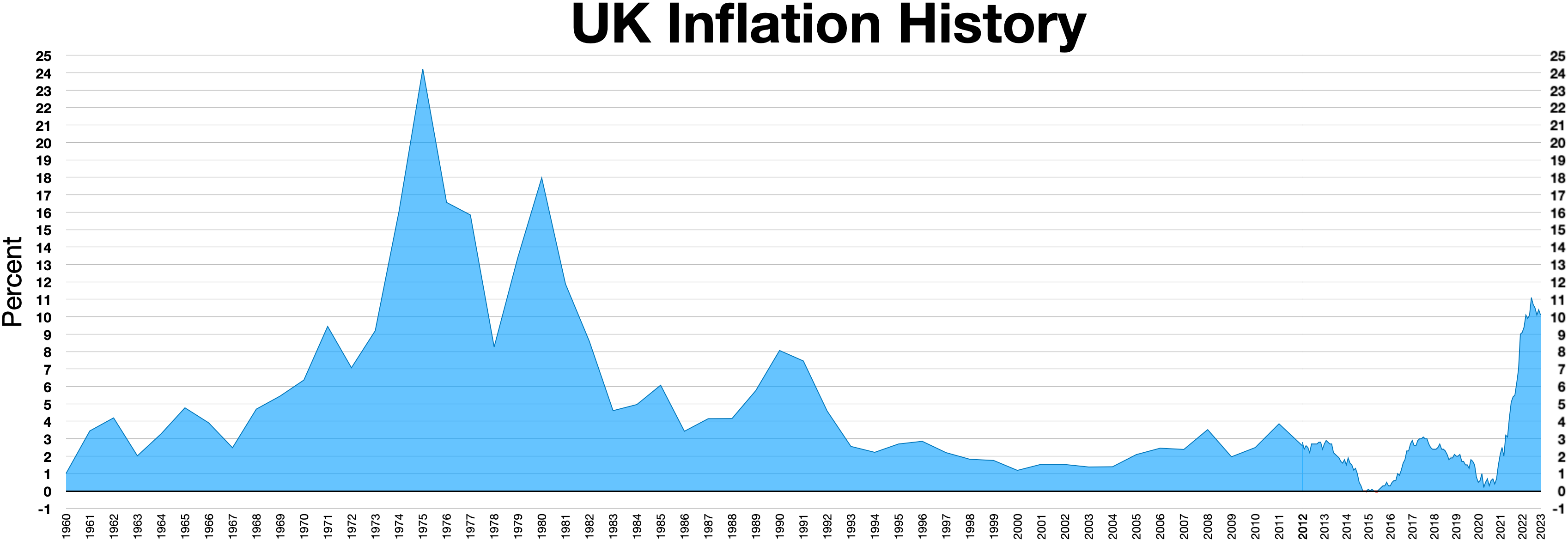

As of 2024 the inflation target is 2%; if this target is missed the Governor is required to write an open letter to the

Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

explaining the situation and proposing remedies. Other than setting the base interest rate, the main tool at the bank's disposal in this regard is

quantitative easing

Quantitative easing (QE) is a monetary policy action where a central bank purchases predetermined amounts of government bonds or other financial assets in order to stimulate economic activity. Quantitative easing is a novel form of monetary polic ...

.

Secure forms of payment

The bank has a monopoly on the issue of

banknotes

A banknote or bank notealso called a bill (North American English) or simply a noteis a type of paper money that is made and distributed ("issued") by a bank of issue, payable to the bearer on demand. Banknotes were originally issued by commer ...

in England and Wales and regulates the issuance of banknotes by commercial banks in Scotland and Northern Ireland. (Scottish and Northern Irish banks retain the right to issue their own banknotes, but they must be backed one-for-one with deposits at the bank, excepting a few million pounds representing the value of notes they had in circulation in 1845.)

In addition the bank supervises other

payment systems

A payment system is any system used to settle financial transactions through the transfer of monetary value. This includes the institutions, payment instruments such as payment cards, people, rules, procedures, standards, and technologies that mak ...

, acting as a

settlement agent and operating

Real-time gross settlement

Real-time gross settlement (RTGS) systems are specialist funds transfer systems where the transfer of money or securities takes place from one bank to any other bank on a "real-time" and on a " gross" basis to avoid settlement risk. Settlement ...

systems including

CHAPS

Chaparreras or chaps () are a type of sturdy over-pants (overalls) or leggings of Mexican origin, made of leather, without a seat, made up of two separate legs that are fastened to the waist with straps or belt. They are worn over trousers and ...

. In 2024 the bank was settling around £500 billion worth of payments between banks each day.

Financial stability

Maintaining financial stability involves protecting the UK's savers, investors and borrowers against threats to the financial system as a whole.

Threats are detected by the bank's surveillance and

market intelligence functions, and dealt with through financial and other operations (both at home and abroad). The majority of these safeguards were put in place in after the

2008 financial crisis

The 2008 financial crisis, also known as the global financial crisis (GFC), was a major worldwide financial crisis centered in the United States. The causes of the 2008 crisis included excessive speculation on housing values by both homeowners ...

:

Regulation

In 2011 the bank's

Prudential Regulation Authority was established to regulate and supervise all major banks, building societies, credit unions, insurers and investment firms in the UK ('

microprudential regulation'). The bank also has a statutory supervisory role in relation to

financial market

A financial market is a market in which people trade financial securities and derivatives at low transaction costs. Some of the securities include stocks and bonds, raw materials and precious metals, which are known in the financial marke ...

infrastructures.

Risk management

At the same time, the bank's

Financial Policy Committee (FPC) was set up to identify and monitor

risks in the financial system, and to take appropriate action where necessary ('

macroprudential regulation'). The FPC publishes its findings (and actions taken) in a biannual Financial Stability Report.

Banking services

The bank provides

wholesale banking

Wholesale banking is the provision of services by banks to larger customers or organizations such as mortgage brokers, large corporate clients, mid-sized companies, real estate developers and investors, international trade finance businesses, ...

services to the UK Government (and to over a hundred overseas central banks).

It manages the UK's

Exchange Equalisation Account on behalf of

HM Treasury

His Majesty's Treasury (HM Treasury or HMT), and informally referred to as the Treasury, is the Government of the United Kingdom’s economic and finance ministry. The Treasury is responsible for public spending, financial services policy, Tax ...

and it maintains the government's

Consolidated Fund account. It also manages the country's

foreign exchange reserves and is custodian of the UK's (and others')

gold reserves

A gold reserve is the gold held by a national central bank, intended mainly as a guarantee to redeem promises to pay depositors, note holders (e.g. paper money), or trading peers, during the eras of the gold standard, and also as a store of v ...

.

The bank also offers 'liquidity support and other services to banks and other financial institutions'.

Commercial banks

A commercial bank is a financial institution that accepts Deposit (finance), deposits from the public and gives loans for the purposes of consumption and investment to make a Profit (economics), profit.

It can also refer to a bank or a division o ...

customarily keep a sizeable proportion of their

cash reserves on

deposit at the Bank of England. These

central bank reserves are used by the banks to settle payments with one another; (for this reason the Bank of England is sometimes called 'the bankers' bank').

In exceptional circumstances, the Bank may act as the

lender of last resort

In public finance, a lender of last resort (LOLR) is a financial entity, generally a central bank, that acts as the provider of liquidity to a financial institution which finds itself unable to obtain sufficient liquidity in the interbank ...

by extending credit when no other institution will.

As a regulator and central bank, the Bank of England has not offered consumer banking services for many years, but it still does manage some public-facing services (such as exchanging superseded bank notes).

Until 2017, Bank staff were entitled to open current accounts directly with the Bank of England and were given the unique sort code of 10-00-00.

Resolution

Under the terms of the

Banking Act 2009 the bank is the UK's Resolution Authority for any bank or building society judged '

too big to fail

"Too big to fail" (TBTF) is a theory in banking and finance that asserts that certain corporations, particularly financial institutions, are so large and so interconnected with an economy that their failure would be disastrous to the greater e ...

'; as such it is empowered to act in the event of a

bank failure 'to protect the UK's vital financial services and financial stability'.

Historic services and responsibilities

Between 1715 and 1998, the Bank of England managed Government Stocks (which formed the bulk of the

national debt

A country's gross government debt (also called public debt or sovereign debt) is the financial liabilities of the government sector. Changes in government debt over time reflect primarily borrowing due to past government deficits. A deficit occ ...

): the bank was responsible for issuing stocks to stockholders, paying dividends and maintaining a register of transfers;

however in 1998, following the decision to grant the bank operational independence, responsibility for government debt management was transferred to a new

Debt Management Office, which also took over Exchequer cash management and responsibility for issuing Treasury bills from the bank in 2000.

Computershare took over as the registrar for UK Government bonds (

gilt-edged securities

Gilt-edged securities, also referred to as gilts, are bonds issued by the UK Government. The term is of British origin, and referred to the debt securities issued by the Bank of England on behalf of His Majesty's Treasury, whose paper certifi ...

or 'gilts') from the bank at the end of 2004. The bank, however, continues to act as

settlement agent for the Debt Management Office and custodian of its

securities

A security is a tradable financial asset. The term commonly refers to any form of financial instrument, but its legal definition varies by jurisdiction. In some countries and languages people commonly use the term "security" to refer to any for ...

.

Ever since its foundation in 1694, the bank had provided a

retail banking

Retail banking, also known as consumer banking or personal banking, is the provision of services by a bank to the general public, rather than to companies, corporations or other banks, which are often described as wholesale banking (corporate ...

service for the Government; however in 2008 it decided to withdraw from offering these services, which are now provided by a range of other financial institutions and managed by the

Government Banking Service.

Until 2016, the bank provided personal banking services as a privilege for employees.

Previously, the bank had maintained private and commercial accounts for all sorts of customers, including individuals, small businesses and public organisations; but a change of policy following the

First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

saw the bank increasingly withdraw from this type of business to focus more clearly on its central banking role.

History

Founding

During the

Nine Years' War

The Nine Years' War was a European great power conflict from 1688 to 1697 between Kingdom of France, France and the Grand Alliance (League of Augsburg), Grand Alliance. Although largely concentrated in Europe, fighting spread to colonial poss ...

, the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

was defeated by the

French Navy

The French Navy (, , ), informally (, ), is the Navy, maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the four military service branches of History of France, France. It is among the largest and most powerful List of navies, naval forces i ...

in the 1690

Battle of Beachy Head, causing consternation in the government of

William III of England

William III (William Henry; ; 4 November 1650 – 8 March 1702), also known as William of Orange, was the sovereign Prince of Orange from birth, Stadtholder of County of Holland, Holland, County of Zeeland, Zeeland, Lordship of Utrecht, Utrec ...

. The English government decided to rebuild the Royal Navy into a force that was capable of challenging the French on equal terms; however, their ability to do so was hampered both by a lack of available public funds and the government's low credit. This lack of credit made it impossible for the English government to borrow the £1.5m that it wanted to use to expand the Royal Navy.

Concept

In 1691,

William Paterson had proposed establishing a national bank as a means of bolstering public finances. As he later wrote in his pamphlet ''A Brief Account of the Intended Bank of England'' (1694): While his scheme was not immediately acted upon, it did provide the basis for the bank's first Charter and the legislation which made its establishment possible.

Two other key figures in the bank's creation were

Charles Montagu, the Member of Parliament for Maldon, who played a crucial role in steering the proposals through Parliament (and was afterwards appointed

Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

); and

Michael Godfrey, who helped persuade City financiers of its benefits (and was subsequently chosen to be the bank's first Deputy Governor).

It has also been claimed (by

W. R. Scott, among others)

that

William Phips

Sir William Phips (or Phipps; February 2, 1651 – February 18, 1695) was the first royally appointed governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, and the first native-born person from New England to be knighted. Phips was famous in his lifeti ...

played a timely, if incidental, role: his successful expedition to retrieve booty from a sunken Spanish

galleon

Galleons were large, multi-decked sailing ships developed in Spain and Portugal.

They were first used as armed cargo carriers by Europe, Europeans from the 16th to 18th centuries during the Age of Sail, and they were the principal vessels dr ...

(the ''

Nuestra Señora de la Concepción

''Nuestra Señora de la Concepción'' ( Spanish: "Our Lady of the (Immaculate) Conception") was a 120-ton Spanish galleon that sailed the Peru–Panama trading route during the 16th century. This ship has earned a place in maritime history not ...

'') helped create an ideal market for the bank's foundation: flooding the market with bullion and creating an enthusiasm for

joint-stock ventures.

Legislation

Paterson's proposal required the Government to set up a fund from which

interest

In finance and economics, interest is payment from a debtor or deposit-taking financial institution to a lender or depositor of an amount above repayment of the principal sum (that is, the amount borrowed), at a particular rate. It is distinct f ...

would be paid to the subscribers. It was decided that this would be provided for by income from

tonnage

Tonnage is a measure of the capacity of a ship, and is commonly used to assess fees on commercial shipping. The term derives from the taxation paid on '' tuns'' or casks of wine. In modern maritime usage, "tonnage" specifically refers to a cal ...

, and certain other shipping

duties routinely levied by HM

Exchequer

In the Civil Service (United Kingdom), civil service of the United Kingdom, His Majesty's Exchequer, or just the Exchequer, is the accounting process of central government and the government's ''Transaction account, current account'' (i.e., mon ...

; therefore Parliament approved the bank's establishment by means of the

Tonnage Act 1694 ('An Act for granting to theire Majesties severall Rates and Duties upon Tunnage of Shipps and Vessells and upon Beere Ale and other Liquors for secureing certaine Recompenses and Advantages in the said Act mentioned to such Persons as shall voluntarily advance the summe of Fifteen hundred thousand Pounds towards the carrying on the Warr against France').

To induce subscription to the loan, the subscribers were to be

incorporated by the name of the Governor and Company of the Bank of England. Public finances were in such dire condition at the time that the terms of the loan (as laid down in the Act of Parliament) were that it was to be serviced at a rate of 8% per annum; there was also a service charge of £4,000 per annum payable to the bank for the management of the loan.

The Act limited the subscribers' investment to a maximum of £10,000 each in the first instance, and £1,200,000 in total (it was envisaged that the Exchequer would raise the remaining £300,000 through other forms of borrowing).

Incorporation

The

royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but ...

of the Bank of England was granted on 27 July 1694, three months after the passing of the Act.

In the end the £1.2 million was raised in 12 days; 1,268 people subscribed. Their holdings were known as Bank Stock (Bank Stock continued to be held in private ownership until 1946 when the Bank of England was nationalised). The majority of the original subscribers were of 'the

mercantile middle classes of London' (though

tradesmen and

artisans

An artisan (from , ) is a skilled worker, skilled craft worker who makes or creates material objects partly or entirely by handicraft, hand. These objects may be wikt:functional, functional or strictly beauty, decorative, for example furnit ...

also subscribed).

Most (more than two-thirds) contributed less than £1,000. As a proportion of the total amount raised, 25% came from '

esquire

Esquire (, ; abbreviated Esq.) is usually a courtesy title. In the United Kingdom, ''esquire'' historically was a title of respect accorded to men of higher social rank, particularly members of the landed gentry above the rank of gentleman ...

s', 21% from merchants and 15% from titled

aristocrats

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense economic, political, and social influence. In Western Christian co ...

. Twelve per cent of the original subscribers were women.

(jointly) invested £10,000, the maximum permitted sum, as did a handful of others (including Sir

John Houblon).

Investment in the navy duly took place. As a side effect, the huge industrial effort needed (including establishing

ironworks

An ironworks or iron works is an industrial plant where iron is smelted and where heavy iron and steel products are made. The term is both singular and plural, i.e. the singular of ''ironworks'' is ''ironworks''.

Ironworks succeeded bloome ...

to make more nails and advances in agriculture feeding the quadrupled strength of the navy) started to transform the economy. This helped the new

Kingdom of Great Britain

Great Britain, also known as the Kingdom of Great Britain, was a sovereign state in Western Europe from 1707 to the end of 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, which united the Kingd ...

–

England and Scotland were formally united in 1707 – to become powerful. The power of the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

made Britain the dominant world power in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Governance

The first Governor of the bank was

John Houblon, and the first Deputy Governor

Michael Godfrey. (330 years later, in 1994, the bank would issue a

£50 note depicting Houblon to mark its

tercentenary.)

Governance was vested in the Governor, his Deputy and a 'Court' of 24 Directors (most of whom were

merchant bankers recruited from the City); the Directors were elected annually by a 'General Court' of all the Bank's registered stockholders (collectively known as 'the Proprietors'). The

common seal of the Court of Directors, adopted on 30 July 1694, depicted '

Britannia

The image of Britannia () is the national personification of United Kingdom, Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used by the Romans in classical antiquity, the Latin was the name variously appli ...

sitting and looking on a Bank of mony'; Britannia has been the bank's emblem ever since.

The Court appointed three senior officers who, alongside the Governor and Deputy Governor, were responsible for its day-to-day running of the bank: the Secretary and Sollicitor, the First Accomptant and the First Cashier. (Their successors, the Secretary, Chief Accountant and

Chief Cashier, continued to head up the main divisions of the bank's operations for the next 250 years: the Chief Cashier and the Chief Accountant had oversight of the 'cash side' and the 'stock side' of the bank, respectively, while the Secretary oversaw its internal administration.)

Besides these officers, the bank in 1694 was staffed by seventeen clerks and two doorkeepers.

Premises

The bank initially did not have its own building, first opening on 1 August 1694 in

Mercers' Hall on

Cheapside

Cheapside is a street in the City of London, the historic and modern financial centre of London, England, which forms part of the A40 road, A40 London to Fishguard road. It links St Martin's Le Grand with Poultry, London, Poultry. Near its eas ...

. This however was found to be too small and from 31 December 1694 the bank operated from

Grocers' Hall (located then on

Poultry

Poultry () are domesticated birds kept by humans for the purpose of harvesting animal products such as meat, Eggs as food, eggs or feathers. The practice of animal husbandry, raising poultry is known as poultry farming. These birds are most typ ...

), where it would remain for almost 40 years.

(Houblon had served as Master of the

Grocers' Company in 1690–1691.)

Operation

The Act of Parliament prohibited the bank from trading in goods or merchandise of any kind, though it was allowed to deal in gold and silver

bullion

Bullion is non-ferrous metal that has been refined to a high standard of elemental purity. The term is ordinarily applied to bulk metal used in the production of coins and especially to precious metals such as gold and silver. It comes from ...

, and in

bills of exchange.

Before very long, the bank was maximising its profits by issuing

banknotes

A banknote or bank notealso called a bill (North American English) or simply a noteis a type of paper money that is made and distributed ("issued") by a bank of issue, payable to the bearer on demand. Banknotes were originally issued by commer ...

, taking

deposits

A deposit account is a bank account maintained by a financial institution in which a customer can deposit and withdraw money. Deposit accounts can be savings accounts, current accounts or any of several other types of accounts explained below.

...

and lending on

mortgages

A mortgage loan or simply mortgage (), in civil law jurisdictions known also as a hypothec loan, is a loan used either by purchasers of real property to raise funds to buy real estate, or by existing property owners to raise funds for any pur ...

.

In its early days the bank made significant losses, not least by accepting

clipped coins in exchange for its banknotes.

The establishment of a Land Bank (by

John Asgill and

Nicholas Barbon) in 1695, and a currency shortage occasioned by the

Great Recoinage of 1696, both threatened the bank's position;

but Parliament intervened, passing

another Act that year, which authorised the bank to increase its capital to over £2.2 million through the enlarging of its stock by new subscriptions.

18th century

In 1700, the

Hollow Sword Blade Company The Hollow Sword Blades Company was a British joint-stock company founded in 1691 by a goldsmith, Sir Stephen Evance, for the manufacture of hollow-ground rapiers.

In 1700 the company was purchased by a syndicate of businessmen who used the corpo ...

was purchased by a group of businessmen who wished to establish a competing English bank (in an action that would today be considered a "back door listing"). The Bank of England's initial monopoly on English banking was due to expire in 1710. However, it was instead renewed, and the Sword Blade company failed to achieve its goal.

The idea and reality of the

national debt

A country's gross government debt (also called public debt or sovereign debt) is the financial liabilities of the government sector. Changes in government debt over time reflect primarily borrowing due to past government deficits. A deficit occ ...

came about at around this time, and this was also largely managed by the bank. Through the 1715

Ways and Means Act, Parliament authorised the bank to receive subscriptions for a government issue of 5% annuities, designed to raise £910,000; this marked the start of the bank's role in managing Government Stocks, which were a means for people to invest in government debt (previously Government borrowing had been administered directly by the Exchequer).

The bank was obliged by the Act to pay half-yearly

dividends

A dividend is a distribution of profits by a corporation to its shareholders, after which the stock exchange decreases the price of the stock by the dividend to remove volatility. The market has no control over the stock price on open on the ex ...

and to keep a book record of all transfers (as it was already accustomed to do with regard to its own Bank Stock).

The bank did not have a monopoly on lending to the government, however: the

South Sea Company

The South Sea Company (officially: The Governor and Company of the merchants of Great Britain, trading to the South Seas and other parts of America and for the encouragement of the Fishery) was a British joint-stock company founded in Ja ...

had been established in 1711, and in 1720 it too became responsible for part of the UK's national debt, becoming a major competitor to the Bank of England. While the "South Sea Bubble" disaster soon ensued, the company continued managing part of the UK national debt until 1853. The

East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company that was founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to Indian Ocean trade, trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (South A ...

too was a lender of choice for the government.

In 1734 there were ninety-six members of staff at the bank.

The bank's charter was renewed in 1742, and again in 1764. By the 1742 Act the bank became the only

joint-stock company

A joint-stock company (JSC) is a business entity in which shares of the company's stock can be bought and sold by shareholders. Each shareholder owns company stock in proportion, evidenced by their shares (certificates of ownership). Shareho ...

allowed to issue bank notes in the metropolis.

Threadneedle Street

The Bank of England moved to its current location, on the site of Sir John Houblon's house and garden in Threadneedle Street (close by the church of

St Christopher le Stocks), in 1734.

(The estate had been purchased ten years earlier; Houblon had died in 1712, but his widow lived on in the house until her death in 1731, after which the house was demolished and work on the bank began.)

The newly built premises, designed by George Sampson, occupied a narrow plot (around wide) extending north from Threadneedle Street.

The front building contained

transfer offices on the first floor, beneath which was an entrance arch leading to a courtyard. Facing the entrance was the 'main building' of the bank:

a

large Hall () in which bank notes were issued and exchanged,

and where deposits and withdrawals could be made.

(Sampson's Great Hall, later known as the Pay Hall, remained ''in situ'' and in use until

Herbert Baker

Sir Herbert Baker (9 June 1862 – 4 February 1946) was an English architect remembered as the dominant force in South African architecture for two decades, and a major designer of some of New Delhi's most notable government structures. He was ...

's comprehensive rebuilding in the late 1920s.)

Beyond the Hall was a quadrangle of buildings enclosing a 'spacious and commodious Court-yard' (later known as Bullion Court). On the south side of the quadrangle were the Court Room and Committee Room, on the north side was a large Accountants' Office; on either side were

arcaded walkways, with rooms for the senior officers, while the upper floors contained offices and apartments.

Beneath the quadrangle were the vaults ('that have very strong Walls and Iron Gates, for the Preservation of the Cash'); access to the courtyard was provided, by way of a passage leading to a 'grand Gateway' on Bartholomew Lane, for the coaches and waggons 'that come frequently loaded with Gold and Silver Bullion'.

The pediment above the entrance to the main Hall was decorated with a carved ''

alto relievo'' figure of

Britannia

The image of Britannia () is the national personification of United Kingdom, Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used by the Romans in classical antiquity, the Latin was the name variously appli ...

(who had appeared on the

common seal of the bank since 30 July 1694); the sculptor was

Robert Taylor, who went on to be appointed Architect, in succession to Sampson, in 1764. Inside, the east end of the Hall was dominated by a large statue by

John Cheere of King William III, lauded in an accompanying Latin inscription as the bank's founder (''conditor'');

at the opposite end, a large

Venetian window looked out on St Christopher's churchyard.

Expansion

In the second half of the 18th century the bank gradually acquired neighbouring plots of land to enable it to expand, and after 1765 new buildings began to be added by the bank's newly appointed architect Robert Taylor. North-west of the Pay Hall, overlooking St Christopher's churchyard to the south, Taylor built a suite of rooms for the Directors of the bank centred on a new (much larger) Court Room and Committee Room (When the bank was rebuilt in the 1920s-30s, these rooms were removed from their original ground-floor location and reconstructed on the first floor; they continue to be used for meetings of the bank's Court of Directors and Monetary Policy Committee respectively.). East of the Pay Hall, Taylor built a suite of halls and offices dedicated to the management of stocks and dividends, which more or less doubled the size of the bank's footprint (extending it as far as Bartholomew Lane).

These rooms were centred on a large Rotunda, also known as the

Brokers' Exchange, where dealing in Government Stock took place; around it were arranged four sizeable Transfer Offices, each corresponding with a different fund (as described in the 1820s: 'In each office under the several letters of the alphabet, are arranged the books on which the names of all persons having property in the funds are registered, as well as the particulars of their respective interests').

All these offices were top-lit, to avoid the need for windows in the external walls.

In 1782 the church of St Christopher le Stocks was demolished, allowing the bank to expand westwards along Threadneedle Street. The new west wing was completed to Taylor's design in 1786 (its frontage matching that of Taylor's earlier east wing): it housed the Reduced Annuities Office, the Cheque Office and the Dividend Warrant Office (among others). Immediately to the north lay the former churchyard of St Christopher le Stocks, which was preserved within the complex of buildings as a garden (known as the 'Garden Court'). North of Bullion Court, Taylor built a new four-storey Library, to house the bank's expanding collection of archives.

The Bank Picquet

The church's demolition had been prompted by the 1780

Gordon Riots

The Gordon Riots of 1780 were several days' rioting in London motivated by anti-Catholic sentiment. They began with a large and orderly protest against the Papists Act 1778, which was intended to reduce official discrimination against British ...

, during which rioters reportedly climbed on the church to throw projectiles at the buildings of the bank. During the riots, in June 1780, the Lord Mayor of London petitioned the Secretary of State to send a military guard to protect the bank and the Mansion House. Thenceforward a nightly guard (the '

Bank Picquet') was provided by soldiers of the

Household Brigade (a practice which continued until 1973). To house the guard Taylor built a barracks (accessed from a separate entrance on Princes Street) in the north-west corner of the site.

John Soane's rebuilding

Sir Robert Taylor died in 1788 and in his place the bank appointed

John Soane

Sir John Soane (; né Soan; 10 September 1753 – 20 January 1837) was an English architect who specialised in the Neoclassical architecture, Neo-Classical style. The son of a bricklayer, he rose to the top of his profession, becoming professor ...

as Architect and Surveyor (he would remain in post until 1827). Under his direction, the bank was further expanded and partially rebuilt, bit by bit but to a cohesive plan. A survey of the buildings, undertaken at the start of his tenure, identified some problems, which were promptly remedied by Soane: for example in 1795 he rebuilt the Rotunda and two of the adjacent Transfer Offices (the Bank Stock Office and the Four Per Cent Office), replacing Taylor's timber roofs, which were leaking, with more durable stonework.

At the same time Soane was tasked with purchasing properties to the north-east, with compulsory purchase powers granted by the (

33 Geo. 3. c. 15), so as to enable the bank to expand in that direction as far as Lothbury. Between 1794 and 1800 he designed a cohesive set of buildings within the new irregularly-shaped site: he reconfigured Bullion Court and provided a new entrance route for vehicles from the north, which was named Lothbury Court; to the west of this he built a new Chief Cashier's office, and rooms for the Secretary and Chief Accountant; to the east he constructed a new Library block and added a fifth Transfer Office (the

Consols

Consols (originally short for consolidated annuities, but subsequently taken to mean consolidated stock) were government bond, government debt issues in the form of perpetual bonds, redeemable at the option of the government. The first British co ...

Transfer Office) to the north of the other four.

The Brokers' Exchange in the Bank

In the late 18th and early 19th century, prior to the establishment of the

London Stock Exchange

The London Stock Exchange (LSE) is a stock exchange based in London, England. the total market value of all companies trading on the LSE stood at US$3.42 trillion. Its current premises are situated in Paternoster Square close to St Paul's Cath ...

, the Rotunda in the Bank of England was used as a

trading floor

Open outcry is a method of communication between professionals on a stock exchange or futures exchange, typically on a trading floor. It involves shouting and the use of hand signals to transfer information primarily about buy and sell orde ...

'where

stock-brokers,

stock-jobbers, and other persons, meet for the purpose of transacting business in public funds'.

Branching off from the Rotunda were 'offices appropriated to the management of each particular stock' containing books listing every individual's registered interest in the fund. The use of the Rotunda for trading ceased in 1838, but it continued to be used for the cashing of fundholders' dividend warrants.

Conflicts and credit crises

The

credit crisis of 1772 has been described as the first modern banking crisis faced by the Bank of England. The whole

City of London

The City of London, also known as ''the City'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and Districts of England, local government district with City status in the United Kingdom, city status in England. It is the Old town, his ...

was in uproar when

Alexander Fordyce

Alexander Fordyce (7 August 1729 – 8 September 1789) was a Scottish banker, centrally involved in the bank run on Neale, James, Fordyce and Down which led to the credit crisis of 1772. He fled abroad and was declared bankrupt, but in time h ...

was declared

bankrupt

Bankruptcy is a legal process through which people or other entities who cannot repay debts to creditors may seek relief from some or all of their debts. In most jurisdictions, bankruptcy is imposed by a court order, often initiated by the de ...

. In August 1773, the Bank of England assisted the EIC with a loan. The strain upon the reserves of the Bank of England was not eased until towards the end of the year.

During the

American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

, business for the bank was so good that

George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

remained a shareholder throughout the period.

By the bank's charter renewal in 1781, it was also the bankers' bank – keeping enough gold to pay its notes on demand until 26 February 1797 when

war had so diminished

gold reserves

A gold reserve is the gold held by a national central bank, intended mainly as a guarantee to redeem promises to pay depositors, note holders (e.g. paper money), or trading peers, during the eras of the gold standard, and also as a store of v ...

that – following an invasion scare caused by the

Battle of Fishguard days earlier – the government prohibited the bank from paying out in gold by the passing of the bank

Restriction Act 1797. This prohibition lasted until 1821.

In 1798, during the

French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars () were a series of sweeping military conflicts resulting from the French Revolution that lasted from 1792 until 1802. They pitted French First Republic, France against Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain, Habsb ...

, a Corps of bank

Volunteers

Volunteering is an elective and freely chosen act of an individual or group giving their time and labor, often for community service. Many volunteers are specifically trained in the areas they work, such as medicine, education, or emergenc ...

was formed (of between 450 and 500 men) to defend the bank in the event of an invasion. It was disbanded in 1802, but promptly re-formed the following year at the start of the

Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

. Its soldiers were trained, in the event of an invasion, to remove the gold and silver from the vaults to a remote location, along with the banknote printing presses and certain important records. An armoury was provided on site at Threadneedle Street for their arms and

accoutrements.

The Corps was finally disbanded in 1814.

19th century

At the start of the 19th century a plan was enacted by John Soane for the further extension of the bank's premises, this time to the north-west (necessitating the rerouting of Princes Street, to form the new western boundary of the site). Much of the area of the new extension was taken up with steam-powered presses for the printing of banknotes (notes continued to be printed on site until the First World War, when the former

St Luke's Hospital was acquired and converted into the bank's printing works). Soane continued in post until 1833; in the last years before his retirement he completed his rebuilding of Taylor's east wing and reconfigured Sampson and Taylor's street-facing façades to make the entire perimeter of the complex a coherent whole.

In 1811, an 'ingeniously contrived clock' by

Thwaites & Co. was installed above the Pay Hall:

as well as chiming the hours and quarters, it conveyed the time remotely (by means of brass rods extending a total of in length) to dials located in sixteen different offices around the site.

The '

panic of 1825

The Panic of 1825 was a stock market crash that originated in the Bank of England, arising partly from speculative investments in Latin America, including the fictitious country of Poyais. The crisis was felt most acutely in Britain, where it led ...

' highlighted risks inherent in the bank's three-way split loyalties: to its stockholders, to the Government (and thereby to the public), and to its commercial banking customers. In 1825–26 the bank was able to avert a liquidity crisis when

Nathan Mayer Rothschild

Nathan Mayer Rothschild (16 September 1777 – 28 July 1836), also known as Baron Nathan Mayer Rothschild, was a British-German banker, businessman and finance, financier. Born in Free City of Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main, he was the third of ...

succeeded in supplying it with gold; nevertheless, after the crisis, many country and provincial banks failed prompting numerous commercial bankruptcies.

The passing of the

Country Bankers Act 1826 allowed the bank to open provincial branches for the better distribution of its banknotes (at the time small country banks, some of which were significantly

undercapitalised, issued their own notes); by the end of the following year eight Bank of England branches had been set up around the country.

The

Bank Charter Act 1844 tied the issue of notes to the gold reserves and gave the Bank of England sole rights with regard to the issue of banknotes in England. Private banks that had previously had that right retained it, provided that their headquarters were outside London and that they deposited security against the notes that they issued; but they were offered inducements to relinquish this right. (The last private bank in England to issue its own notes was Thomas Fox's

Fox, Fowler and Company bank in

Wellington

Wellington is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the third-largest city in New Zealand (second largest in the North Island ...

, which rapidly expanded until it merged with Lloyds Bank in 1927. They remained legal tender until 1964. (There are nine notes left in circulation; one is housed at

Tone Dale House, Wellington.))

The bank acted as

lender of last resort

In public finance, a lender of last resort (LOLR) is a financial entity, generally a central bank, that acts as the provider of liquidity to a financial institution which finds itself unable to obtain sufficient liquidity in the interbank ...

for the first time in the

panic of 1866.

20th century

Until 1931 Britain was on the

gold standard

A gold standard is a backed currency, monetary system in which the standard economics, economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the ...

, meaning the value of sterling was fixed by the price of gold. That year, the Bank of England had to

take Britain off the gold standard due to the effects of

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

spreading to Europe.

1913 attempted bombing

A

terrorist

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of violence against non-combatants to achieve political or ideological aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violence during peacetime or in the context of war aga ...

bombing was attempted outside the Bank of England building on 4 April 1913. A bomb was discovered smoking and ready to explode next to railings outside the building.

The bomb had been planted as part of the

suffragette bombing and arson campaign

Suffragettes in Great Britain and Ireland orchestrated a bombing and arson campaign between the years 1912 and 1914. The campaign was instigated by the Women's Social and Political Union, Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), and was a part ...

, in which the

Women's Social and Political Union

The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) was a women-only political movement and leading militant organisation campaigning for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom founded in 1903. Known from 1906 as the suffragettes, its membership and p ...

(WSPU) launched a series of politically motivated bombing and arson attacks nationwide as part of their campaign for women's suffrage.

The bomb was defused before it could detonate, in what was then one of the busiest public streets in the capital, which likely prevented many civilian casualties.

The bomb had been planted the day after WSPU leader

Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst (; Goulden; 15 July 1858 – 14 June 1928) was a British political activist who organised the British suffragette movement and helped women to win in 1918 the women's suffrage, right to vote in United Kingdom of Great Brita ...

was sentenced to three years' imprisonment for carrying out a bombing on the home of politician

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

.

The remains of the bomb, which was built into a

milk churn, are now on display at the

City of London Police Museum.

Restructuring and rebuilding

During the governorship of

Montagu Norman

Montagu Collet Norman, 1st Baron Norman DSO PC (6 September 1871 – 4 February 1950) was an English banker, best known for his role as the Governor of the Bank of England from 1920 to 1944.

Norman led the bank during the toughest period in ...

, from 1920 to 1944, the bank made deliberate efforts to move away from

commercial bank

A commercial bank is a financial institution that accepts deposits from the public and gives loans for the purposes of consumption and investment to make a profit.

It can also refer to a bank or a division of a larger bank that deals with whol ...

ing and become a central bank. A later Governor,

Robin Leigh-Pemberton, described it as 'a time of rapid change, in which we began to move away from the clerical traditions of 200 years

..and to accept specialisation, mechanisation and modern management disciplines'.

Economists and statisticians began to be employed at the bank in increasing number. In 1931 the 'Peacock Committee', set up to advise on organisational improvements, published recommendations which included the appointment of paid executive Directors (alongside the traditional non-executive members of the Court). It also recommended reconfiguration of the bank's traditional departmental structures.

The work of the bank had significantly increased since the end of the First World War, and the decision was taken to expand. Between 1925 and 1939 the bank's headquarters on Threadneedle Street were comprehensively rebuilt by

Herbert Baker

Sir Herbert Baker (9 June 1862 – 4 February 1946) was an English architect remembered as the dominant force in South African architecture for two decades, and a major designer of some of New Delhi's most notable government structures. He was ...

. (This involved the demolition of most of Sir John Soane's buildings, an act described by architectural historian

Nikolaus Pevsner

Sir Nikolaus Bernhard Leon Pevsner (30 January 1902 – 18 August 1983) was a German-British art historian and architectural historian best known for his monumental 46-volume series of county-by-county guides, ''The Buildings of England'' (195 ...

as "the greatest architectural crime, in the

City of London

The City of London, also known as ''the City'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and Districts of England, local government district with City status in the United Kingdom, city status in England. It is the Old town, his ...

, of the twentieth century".) Initially the plan had been to retain Soane's banking halls behind the curtain wall, but this proved challenging so they were instead demolished and rebuilt in facsimile.

The demolition and rebuilding took place in stages, with staff moving from one part of the building to another (or, in some cases, into temporary accommodation at

Finsbury Circus

Finsbury Circus is a park in the Coleman Street Ward of the City of London, England. The 2 acre park is the largest public open space within the City's boundaries.

It is not to be confused with Finsbury Square, just north of the City, or Fins ...

). The bullion and securities remained on site throughout. During reconstruction human remains pertaining to the old churchyard of St Christopher le Stocks were exhumed and reburied at

Nunhead Cemetery

Nunhead Cemetery is one of the Magnificent Seven cemeteries in London, England. It is perhaps the least famous and celebrated of them. The cemetery is located in Nunhead in the London Borough of Southwark and was originally known as All Saint ...

.

Baker's

steel-framed building stands seven storeys high, with a further three vault storeys extending below ground level. It is decorated with sculpture and bronze work by

Charles Wheeler, plasterwork by Joseph Armitage and mosaics by

Boris Anrep.

The bank today is a

Grade I listed

In the United Kingdom, a listed building is a structure of particular architectural or historic interest deserving of special protection. Such buildings are placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Hi ...

building.

1939 saw the introduction of

Exchange Controls in the United Kingdom at the outbreak of the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

; these were administered by the bank.

During WWII, over 10% of the face value of circulating Pound Sterling banknotes were forgeries produced by Germany.

A number of the bank's operations and staff were relocated to Hampshire for the duration of the war, including the printing works (which moved to

Overton), the Accountant's Department (which went to

Hurstbourne Park) and various other offices. Those who remained at Threadneedle Street, including the Directors, moved their offices into the underground vaults.

Post-war nationalisation

In 1946, shortly after the end of Montagu Norman's tenure,

the bank was nationalised by the

Labour government. At the same time the number of Directors was reduced to sixteen (four of whom were full-time Executive Directors).

The bank pursued the multiple goals of Keynesian economics after 1945, especially "easy money" and low-interest rates to support aggregate demand. It tried to keep a fixed exchange rate and attempted to deal with inflation and sterling weakness by credit and exchange controls.

After the war, the very large Accountant's Department (which managed the stock side of the bank) moved back to London from Hampshire. Its designated office-space at Threadneedle Street, however, had in the meantime been taken over by the Exchange Control office. The department was instead provided with temporary accommodation (once more in Finsbury Circus), pending construction of a new building, which would occupy a two-acre

bombsite immediately to the east of

St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of St Paul the Apostle, is an Anglican cathedral in London, England, the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London in the Church of Engl ...

. 'Bank of England New Change' was designed by Victor Heal and opened in 1957 (at the time it was London's biggest post-war rebuilding project); the new building contained several staff amenities alongside the office accommodation and, at street level, retail units were let to an assortment of businesses. The bank had the building on a 200-year lease; but with the advent of computerisation staff numbers were drastically reduced in the 1980s-90s; parts of the building were let to other firms (most notably the law firm

Allen & Overy

Allen & Overy LLP was a British multinational corporation, multinational law firm headquartered in London, England. The firm has 590 partners and over 5,800 employees worldwide. In 2023 A&O reported an increase in revenue to GBP2.1 billion ...

). The bank sold the building in 2000 and in 2007 it was demolished;

One New Change now stands on the site.

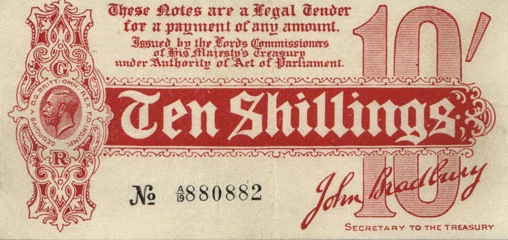

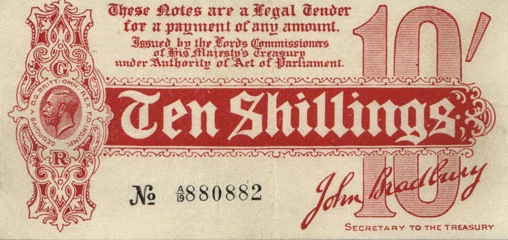

The bank's "

10 bob note" was withdrawn from circulation in 1970 in preparation for

Decimal Day

Decimal Day () in the United Kingdom and in Republic of Ireland, Ireland was Monday 15 February 1971, the day on which each country decimalised its respective £sd currency of pound sterling, pounds, Shilling (British coin), shillings, and pe ...

in 1971.

In 1977 the bank set up a wholly owned subsidiary called

Bank of England Nominees Limited (BOEN), a now-defunct private limited company, with two of its hundred £1 shares issued. According to its memorandum of association, its objectives were: "To act as Nominee or agent or attorney either solely or jointly with others, for any person or persons, partnership, company, corporation, government, state, organisation, sovereign, province, authority, or public body, or any group or association of them". Bank of England Nominees Limited was granted an exemption by

Edmund Dell, Secretary of State for Trade, from the disclosure requirements under Section 27(9) of the Companies Act 1976, because "it was considered undesirable that the disclosure requirements should apply to certain categories of shareholders". The Bank of England is also protected by its

royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but ...

status and the

Official Secrets Act

An Official Secrets Act (OSA) is legislation that provides for the protection of Classified information, state secrets and official information, mainly related to national security. However, in its unrevised form (based on the UK Official Secret ...

. BOEN was a vehicle for governments and heads of state to invest in UK companies (subject to approval from the Secretary of State), providing they undertake "not to influence the affairs of the company". In its later years, BOEN was no longer exempt from company law disclosure requirements. Although a

dormant company, dormancy does not preclude a company actively operating as a nominee shareholder. BOEN had two shareholders: the Bank of England, and the Secretary of the Bank of England.

The

reserve requirement

Reserve requirements are central bank regulations that set the minimum amount that a commercial bank must hold in liquid assets. This minimum amount, commonly referred to as the Bank reserves, commercial bank's reserve, is generally determined ...

for banks to hold a minimum fixed proportion of their deposits as reserves at the Bank of England was abolished in 1981: see for more details. The contemporary transition from Keynesian economics to Chicago economics was analysed by

Nicholas Kaldor

Nicholas Kaldor, Baron Kaldor (12 May 1908 – 30 September 1986), born Káldor Miklós, was a Hungarian-born British economist. He developed the "compensation" criteria called Kaldor–Hicks efficiency for welfare spending, welfare comparisons ...

in ''The Scourge of Monetarism''.

The handing over of monetary policy to the bank became a key plank of the

Liberal Democrats' economic policy for the

1992 general election.

Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

MP

Nicholas Budgen had also proposed this as a

private member's bill

A private member's bill is a bill (proposed law) introduced into a legislature by a legislator who is not acting on behalf of the executive branch. The designation "private member's bill" is used in most Westminster system jurisdictions, in wh ...

in 1996, but the bill failed as it had the support of neither the government nor the opposition.

The UK government left the expensive-to-maintain

European Exchange Rate Mechanism

The European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II) is a system introduced by the European Economic Community on 1 January 1999 alongside the introduction of a single currency, the euro (replacing ERM 1 and the euro's predecessor, the ECU) as ...

in September 1992, in an action that cost HM Treasury over £3 billion. This led to closer communication between the government and the bank.

In 1993, the bank produced its first ''Inflation Report'' for the government, detailing inflationary trends and pressures. This annually produced report remains one of the bank's major publications.

The success of

inflation targeting in the United Kingdom has been attributed to the bank's focus on transparency.

The Bank of England has been a leader in producing innovative ways of communicating information to the public, especially through its Inflation Report, which many other central banks have emulated.

The bank celebrated its three-hundredth birthday in 1994.

In 1996, the bank produced its first ''Financial Stability Review''. This annual publication became known as the ''Financial Stability Report'' in 2006.

Also that year, the bank set up its

real-time gross settlement

Real-time gross settlement (RTGS) systems are specialist funds transfer systems where the transfer of money or securities takes place from one bank to any other bank on a "real-time" and on a " gross" basis to avoid settlement risk. Settlement ...

(RTGS) system to improve risk-free settlement between UK banks.

On 6 May 1997, following the

1997 general election that brought a Labour government to power for the first time since 1979, it was announced by the Chancellor of the Exchequer,

Gordon Brown

James Gordon Brown (born 20 February 1951) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 2007 to 2010. Previously, he was Chancellor of the Ex ...

, that the bank would be granted operational independence over monetary policy. Under the terms of the

Bank of England Act 1998 (which came into force on 1 June 1998) the bank's

Monetary Policy Committee

The Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) is a committee of the Bank of England, which meets for three and a half days, eight times a year, to decide the official interest rate in the United Kingdom (the Bank of England Base Rate).

It is also respo ...

(MPC) was given sole responsibility for setting interest rates to meet the Government's

Retail Prices Index (RPI) inflation target of 2.5%. The target has changed to 2% since the

Consumer Price Index

A consumer price index (CPI) is a statistical estimate of the level of prices of goods and services bought for consumption purposes by households. It is calculated as the weighted average price of a market basket of Goods, consumer goods and ...

(CPI) replaced the Retail Prices Index as the Treasury's inflation index. If inflation overshoots or undershoots the target by more than 1% the Governor has to write a letter to the

Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

explaining why, and how he will remedy the situation.

Independent central banks that adopt an inflation target are known as

Friedmanite central banks. This change in Labour's politics was described by

Skidelsky in ''The Return of the Master'' as a mistake and as an adoption of the

rational expectations hypothesis as promulgated by

Alan Walters. Inflation targets combined with central bank independence have been characterised as a "starve the beast" strategy creating a lack of money in the public sector.

in June 1998 responsibility for the regulation and supervision of the banking and insurance industries was transferred from the bank to the

Financial Services Authority

The Financial Services Authority (FSA) was a quasi-judicial body accountable for the regulation of the financial services industry in the United Kingdom between 2001 and 2013. It was founded as the Securities and Investments Board (SIB) in 1985 ...

. A

memorandum of understanding described the terms under which the bank, the Treasury, and the FSA would work toward the common aim of increased financial stability. (Ten years later, however, after the

2008 financial crisis

The 2008 financial crisis, also known as the global financial crisis (GFC), was a major worldwide financial crisis centered in the United States. The causes of the 2008 crisis included excessive speculation on housing values by both homeowners ...

, new banking legislation transferred the responsibility for regulation and supervision of the banking and insurance industries back to the Bank of England).

21st century

The bank decided to sell its banknote-printing operations to

De La Rue

De La Rue plc (, ) is a British company headquartered in Basingstoke, England, that produces secure digital and physical protections for goods, trade, and identities in 140 countries. It sells to governments, central banks, and businesses. Its ...

in December 2002, under the advice of Close Brothers Corporate Finance Ltd.

Mervyn King became the

Governor of the Bank of England

The governor of the Bank of England is the most senior position in the Bank of England. It is nominally a civil service post, but the appointment tends to be from within the bank, with the incumbent choosing and mentoring a successor. The governor ...

on 30 June 2003.

In 2009, a request made to

HM Treasury

His Majesty's Treasury (HM Treasury or HMT), and informally referred to as the Treasury, is the Government of the United Kingdom’s economic and finance ministry. The Treasury is responsible for public spending, financial services policy, Tax ...

under the

Freedom of Information Act sought details about the 3% Bank of England stock owned by unnamed shareholders whose identity the bank is not at liberty to disclose. In a letter of reply dated 15 October 2009, HM Treasury explained that "Some of the 3% Treasury stock which was used to compensate former owners of bank stock has not been redeemed. However, interest is paid out twice a year and it is not the case that this has been accumulating and compounding."

In 2010, the incoming Chancellor announced his intention to merge the Financial Services Authority back into the bank. In 2011 an interim

Financial Policy Committee (FPC) was created (as a mirror committee to the Monetary Policy Committee) to spearhead the bank's new mandate on financial stability. The

Financial Services Act 2012 gave the bank additional functions and bodies, including an independent FPC, the

Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA), and more powers to supervise financial market infrastructure providers.

It also created the independent

Financial Conduct Authority

The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) is a financial regulatory body in the United Kingdom. It operates independently of the UK Government and is financed by charging fees to members of the financial services industry. The FCA regulates financi ...

. These bodies are responsible for

macroprudential regulation of all UK banks and insurance companies.

Canadian

Mark Carney

Mark Joseph Carney (born March 16, 1965) is a Canadian politician and economist who has served as the 24th and current Prime Minister of Canada, prime minister of Canada since 2025. He has served as Leader of the Liberal Party of Canada, lead ...

assumed the post of

Governor of the Bank of England

The governor of the Bank of England is the most senior position in the Bank of England. It is nominally a civil service post, but the appointment tends to be from within the bank, with the incumbent choosing and mentoring a successor. The governor ...

on 1 July 2013. He served an initial five-year term rather than the typical eight. He became the first Governor not to be a United Kingdom citizen but has since been granted citizenship. At Government request, his term was extended to 2019, then again to 2020. , the bank also had four

Deputy Governors.

BOEN was dissolved, following liquidation, in July 2017.

Andrew Bailey succeeded Carney as the Governor of the Bank of England on 16 March 2020.

Asset purchase facility

The bank has operated, since January 2009, an Asset Purchase Facility (APF) to buy "high-quality assets financed by the issue of Treasury bills and the

DMO's cash management operations" and thereby improve liquidity in the credit markets.

It has, since March 2009, also provided the mechanism by which the bank's policy of

quantitative easing

Quantitative easing (QE) is a monetary policy action where a central bank purchases predetermined amounts of government bonds or other financial assets in order to stimulate economic activity. Quantitative easing is a novel form of monetary polic ...

(QE) is achieved, under the auspices of the MPC. Along with managing the QE funds, which were £895 bn at peak, the APF continues to operate its corporate facilities. Both are undertaken by a subsidiary company of the Bank of England, the Bank of England Asset Purchase Facility Fund Limited (BEAPFF).

QE was primarily designed as an instrument of monetary policy. The mechanism required the Bank of England to purchase government bonds on the secondary market, financed by creating new

central bank money. This would have the effect of increasing the asset prices of the bonds purchased, thereby lowering yields and dampening longer-term interest rates. The policy's aim was initially to ease liquidity constraints in the sterling reserves system but evolved into a wider policy to provide economic stimulus.

QE was enacted in six tranches between 2009 and 2020. At its peak in 2020, the portfolio totalled £895 billion, comprising £875 billion of UK government bonds and £20 billion of high-grade commercial bonds.

In February 2022, the Bank of England announced its intention to commence winding down the QE portfolio. Initially this would be achieved by not replacing tranches of maturing bonds, and would later be accelerated through active bond sales.

In August 2022, the Bank of England reiterated its intention to accelerate the QE wind-down through active bond sales. This policy was affirmed in an exchange of letters between the Bank of England and the UK Chancellor of the Exchequer in September 2022. Between February 2022 and September 2022, a total of £37.1bn of government bonds matured, reducing the outstanding stock from £875.0bn at the end of 2021 to £837.9bn. In addition, a total of £1.1bn of corporate bonds matured, reducing the stock from £20.0bn to £18.9bn, with sales of the remaining stock planned to begin on 27 September.

Banknote issues

The bank has issued banknotes since 1694. Notes were originally hand-written; although they were partially printed from 1725 onwards, cashiers still had to sign each note and make them payable to someone. Notes were fully printed from 1855. Until 1928 all notes were "White Notes", printed in black and with a blank reverse. In the 18th and 19th centuries, White Notes were issued in £1 and £2 denominations. During the 20th century, White Notes were issued in denominations between £5 and £1000. Until the passing of the

Gold Standard Act 1925 the bank was obliged to pay on demand the value of the note in gold coin to its bearer.

In 1724 the bank entered into a contract with

Henry Portal of

Whitchurch, Hampshire

Whitchurch is a town in the borough of Basingstoke and Deane in Hampshire, England. It is on the River Test, south of Newbury, Berkshire, north of Winchester, east of Andover, Hampshire, Andover and west of Basingstoke. Much of the town is ...

to provide high-quality paper for the printing of banknotes.

The printing itself was undertaken by private printing firms; the

copper plates were kept in the vault, and accompanied during their time at the printer by a bank clerk (who would record the number of copies made); once dry they would be delivered to the bank. The printing operation was brought within the bank's premises (albeit still under private contract) in 1791; in 1808 it was brought fully in-house.

Until the mid-19th century, commercial banks were allowed to issue their own banknotes, and notes issued by provincial banking companies were commonly in circulation. The

Bank Charter Act 1844 began the process of restricting note issue to the bank; new banks were prohibited from issuing their own banknotes, and existing note-issuing banks were not permitted to expand their issue. As provincial banking companies merged to form larger banks, they lost their right to issue notes, and the English private banknote eventually disappeared, leaving the bank with a monopoly of note issues in England and Wales. The last private bank to issue its own banknotes in England and Wales was

Fox, Fowler and Company in 1921.

[; ] However, the limitations of the 1844 Act only affected banks in England and Wales, and today three commercial banks in Scotland and four in Northern Ireland continue to issue their own

banknotes

A banknote or bank notealso called a bill (North American English) or simply a noteis a type of paper money that is made and distributed ("issued") by a bank of issue, payable to the bearer on demand. Banknotes were originally issued by commer ...

, regulated by the bank.

[

] At the start of the

At the start of the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the Currency and Bank Notes Act 1914 was passed, which granted temporary powers to HM Treasury

His Majesty's Treasury (HM Treasury or HMT), and informally referred to as the Treasury, is the Government of the United Kingdom’s economic and finance ministry. The Treasury is responsible for public spending, financial services policy, Tax ...