Arthur Schopenhauer on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Arthur Schopenhauer ( ; ; 22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher. He is known for his 1818 work '' The World as Will and Representation'' (expanded in 1844), which characterizes the phenomenal world as the manifestation of a blind and irrational noumenal

Arthur Schopenhauer was born on 22 February 1788 in

Arthur Schopenhauer was born on 22 February 1788 in  Arthur spent two years as a merchant in honor of his dead father. During this time, he had doubts about being able to start a new life as a scholar. Most of his prior education was as a practical merchant and he had trouble learning Latin; a prerequisite for an academic career.

His mother moved away, with her daughter Adele, to

Arthur spent two years as a merchant in honor of his dead father. During this time, he had doubts about being able to start a new life as a scholar. Most of his prior education was as a practical merchant and he had trouble learning Latin; a prerequisite for an academic career.

His mother moved away, with her daughter Adele, to

After his efforts in academia, he continued to travel extensively, visiting

After his efforts in academia, he continued to travel extensively, visiting  In 1851, Schopenhauer published '' Parerga and Paralipomena'', which contains essays that are supplementary to his main work. It was his first successful, widely read book, partly due to the work of his disciples who wrote praising reviews. The essays that proved most popular were the ones that actually did not contain the basic philosophical ideas of his system. Many academic philosophers considered him a great stylist and cultural critic but did not take his philosophy seriously. His early critics liked to point out similarities of his ideas to those of Fichte and Schelling, or to claim that there were numerous contradictions in his philosophy. Both criticisms enraged Schopenhauer. He was becoming less interested in intellectual fights, but encouraged his disciples to do so. His private notes and correspondence show that he acknowledged some of the criticisms regarding contradictions, inconsistencies, and vagueness in his philosophy, but claimed that he was not concerned about harmony and agreement in his propositions and that some of his ideas should not be taken literally but instead as metaphors.

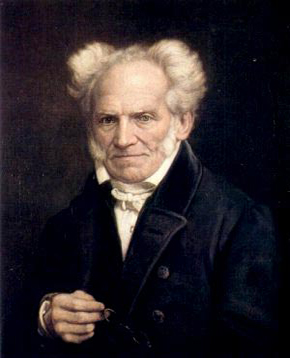

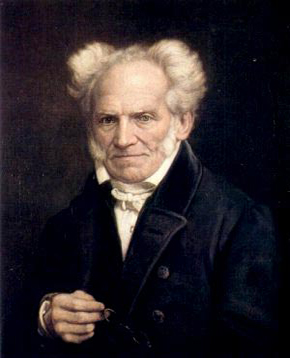

Academic philosophers were also starting to notice his work. In 1856, the University of Leipzig sponsored an essay contest about Schopenhauer's philosophy, which was won by Rudolf Seydel's very critical essay. Schopenhauer's friend Jules Lunteschütz made the first of his four portraits of him—which Schopenhauer did not particularly like—which was soon sold to a wealthy landowner, Carl Ferdinand Wiesike, who built a house to display it. Schopenhauer seemed flattered and amused by this, and would claim that it was his first chapel. As his fame increased, copies of paintings and photographs of him were being sold and admirers were visiting the places where he had lived and written his works. People visited Frankfurt's ''Englischer Hof'' to observe him dining. Admirers gave him gifts and asked for autographs. He complained that he still felt isolated due to his not very social nature and the fact that many of his good friends had already died from old age.

In 1851, Schopenhauer published '' Parerga and Paralipomena'', which contains essays that are supplementary to his main work. It was his first successful, widely read book, partly due to the work of his disciples who wrote praising reviews. The essays that proved most popular were the ones that actually did not contain the basic philosophical ideas of his system. Many academic philosophers considered him a great stylist and cultural critic but did not take his philosophy seriously. His early critics liked to point out similarities of his ideas to those of Fichte and Schelling, or to claim that there were numerous contradictions in his philosophy. Both criticisms enraged Schopenhauer. He was becoming less interested in intellectual fights, but encouraged his disciples to do so. His private notes and correspondence show that he acknowledged some of the criticisms regarding contradictions, inconsistencies, and vagueness in his philosophy, but claimed that he was not concerned about harmony and agreement in his propositions and that some of his ideas should not be taken literally but instead as metaphors.

Academic philosophers were also starting to notice his work. In 1856, the University of Leipzig sponsored an essay contest about Schopenhauer's philosophy, which was won by Rudolf Seydel's very critical essay. Schopenhauer's friend Jules Lunteschütz made the first of his four portraits of him—which Schopenhauer did not particularly like—which was soon sold to a wealthy landowner, Carl Ferdinand Wiesike, who built a house to display it. Schopenhauer seemed flattered and amused by this, and would claim that it was his first chapel. As his fame increased, copies of paintings and photographs of him were being sold and admirers were visiting the places where he had lived and written his works. People visited Frankfurt's ''Englischer Hof'' to observe him dining. Admirers gave him gifts and asked for autographs. He complained that he still felt isolated due to his not very social nature and the fact that many of his good friends had already died from old age.

He remained healthy in his own old age, which he attributed to regular walks no matter the weather and always getting enough sleep. He had a great appetite and could read without glasses, but his

He remained healthy in his own old age, which he attributed to regular walks no matter the weather and always getting enough sleep. He had a great appetite and could read without glasses, but his

For Schopenhauer, human "willing"—desiring, craving, etc.—is at the root of

For Schopenhauer, human "willing"—desiring, craving, etc.—is at the root of

Schopenhauer's politics were an echo of his system of ethics, which he elucidated in detail in his ''Die beiden Grundprobleme der Ethik'' (the two essays ''On the Freedom of the Will'' and ''On the Basis of Morality'').

In occasional political comments in his '' Parerga and Paralipomena'' and ''Manuscript Remains'', Schopenhauer described himself as a proponent of limited government. Schopenhauer shared the view of

Schopenhauer's politics were an echo of his system of ethics, which he elucidated in detail in his ''Die beiden Grundprobleme der Ethik'' (the two essays ''On the Freedom of the Will'' and ''On the Basis of Morality'').

In occasional political comments in his '' Parerga and Paralipomena'' and ''Manuscript Remains'', Schopenhauer described himself as a proponent of limited government. Schopenhauer shared the view of

Schopenhauer viewed personality and

Schopenhauer viewed personality and

"Schopenhauer on the Rights of Animals." ''European Journal of Philosophy'' 25/2 (2017):250–269

. For him, all individual animals, including humans, are essentially phenomenal manifestations of the one underlying Will. For him the word "will" designates force, power, impulse, energy, and desire; it is the closest word we have that can signify both the essence of all external things and our own direct, inner experience. Since every living thing possesses will, humans and animals are fundamentally the same and can recognize themselves in each other. For this reason, he claimed that a good person would have sympathy for animals, who are our fellow sufferers. In 1841, he praised the establishment in London of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, and in Philadelphia of the Animals' Friends Society. Schopenhauer went so far as to protest using the pronoun "it" in reference to animals because that led to treatment of them as though they were inanimate things. To reinforce his points, Schopenhauer referred to anecdotal reports of the look in the eyes of a monkey who had been shot and also the grief of a baby elephant whose mother had been killed by a hunter. Schopenhauer was very attached to his succession of pet poodles. He criticized

Schopenhauer read the Latin translation of the ancient Hindu texts, the ''

Schopenhauer read the Latin translation of the ancient Hindu texts, the ''

Kant's influence on Schopenhauer's development, personally as well as in philosophy, was extensive. Kant's philosophy lies at the foundation of Schopenhauer's, and he had high praise for the Transcendental Aesthetic section of Kant's ''Critique of Pure Reason''. Schopenhauer maintained that Kant stands in the same relation to philosophers such as Berkeley and

Kant's influence on Schopenhauer's development, personally as well as in philosophy, was extensive. Kant's philosophy lies at the foundation of Schopenhauer's, and he had high praise for the Transcendental Aesthetic section of Kant's ''Critique of Pure Reason''. Schopenhauer maintained that Kant stands in the same relation to philosophers such as Berkeley and

Schopenhauer remained the most influential German philosopher until the

Schopenhauer remained the most influential German philosopher until the  Early in his career,

Early in his career,

The Art of Controversy (Die Kunst, Recht zu behalten)

''. (bilingual) The Art of Being Right''">' The Art of Being Right''*

Studies in Pessimism

' – audiobook from LibriVox * ''The World as Will and Idea'' at the

Volume I

' **

Volume II

' **

Volume III

' * "On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason" and "On the will in nature". Two essays: *

Internet Archive

Translated by Mrs. Karl Hillebrand (1903). *

Cornell University Library Historical Monographs Collection

Reprinted by Cornell University Library Digital Collections

Facsimile edition of Schopenhauer's manuscripts

i

SchopenhauerSource

*

''

Arthur Schopenhauer: His Life and His Philosophy

' (London: Longmans, Green & Co, 1876)

Arthur Schopenhauer and China. ''Sino-Platonic Papers'' Nr. 200 (April 2010)

(PDF, 8.7 Mb PDF, 164 p.). Contains extensive appendixes with transcriptions and English translations of Schopenhauer's early notes about Buddhism and Indian philosophy. * App, Urs, ''Schopenhauers Kompass. Die Geburt einer Philosophie.'' UniversityMedia, Rorschach/ Kyoto 2011. * Atwell, John. ''Schopenhauer on the Character of the World, The Metaphysics of Will''. * Atwell, John, ''Schopenhauer, The Human Character''. * Edwards, Anthony. ''An Evolutionary Epistemological Critique of Schopenhauer's Metaphysics''. 123 Books, 2011. * Copleston, Frederick, ''Schopenhauer: Philosopher of Pessimism'', 1946 (reprinted London: Search Press, 1975). * Gardiner, Patrick, 1963. ''Schopenhauer''. Penguin Books. * Janaway, Christopher, 2002. ''Schopenhauer: A Very Short introduction''. Oxford University Press. * Janaway, Christopher, 2003. ''Self and World in Schopenhauer's Philosophy''. Oxford University Press. * Magee, Bryan, ''The Philosophy of Schopenhauer'', Oxford University Press (1988, reprint 1997). * Marcin, Raymond B. ''In Search of Schopenhauer's Cat: Arthur Schopenhauer's Quantum-Mystical Theory of Justice''. Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 2005. * Norberg, Jakob

Schopenhauer's Politics

* Mannion, Gerard, "Schopenhauer, Religion and Morality – The Humble Path to Ethics", Ashgate Press, New Critical Thinking in Philosophy Series, 2003, 314pp. * Whittaker, Thomas

Schopenhauer

* Zimmern, Helen, '' Arthur Schopenhauer, his Life and Philosophy'', London, Longman, and Co., 1876. * Kastrup, Bernardo. ''Decoding Schopenhauer's Metaphysics – The key to understanding how it solves the hard problem of consciousness and the paradoxes of quantum mechanics.'' Winchester/Washington, iff Books, 2020. * de Botton, Alain: ''

Tagebuch eines Ehrgeizigen: Arthur Schopenhauers Studienjahre in Berlin

" ''Avinus Magazin'' (in German). * Luchte, James, 2009,

The Body of Sublime Knowledge: The Aesthetic Phenomenology of Arthur Schopenhauer

" ''Heythrop Journal'', Volume 50, Number 2, pp. 228–242. * Mazard, Eisel, 2005,

Schopenhauer and the Empirical Critique of Idealism in the History of Ideas.

" On Schopenhauer's (debated) place in the history of European philosophy and his relation to his predecessors. * Sangharakshita, 2004,

Schopenhauer and aesthetic appreciation.

*

Oxenford's "Iconoclasm in German Philosophy," (See p. 388)

* Thacker, Eugene, 2020. "A Philosophy in Ruins, An Unquiet Void." Introduction to Arthur Schopenhauer, ''On the Suffering of the World''. Repeater Books. .

Arthur Schopenhauer

an article by Mary Troxell in the ''

Kant's philosophy as rectified by Schopenhauer

* ttp://ljhammond.com/classics/cl1.htm#scho A Quick Introduction to Schopenhauer* Ross, Kelley L., 1998,

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860)

. Two short essays, on Schopenhauer's life and work, and on his dim view of academia. {{DEFAULTSORT:Schopenhauer, Arthur 1788 births 1860 deaths 19th-century atheists 19th-century German philosophers Academic staff of the Humboldt University of Berlin German animal rights scholars Anti-natalists Atheist philosophers Burials at Frankfurt Main Cemetery German epistemologists German atheists German ethicists German people of Dutch descent German scholars of Buddhism German idealists Kantian philosophers German philosophers of art Philosophers of pessimism Philosophers of psychology University of Göttingen alumni Writers from Gdańsk

will

Will may refer to:

Common meanings

* Will and testament, instructions for the disposition of one's property after death

* Will (philosophy), or willpower

* Will (sociology)

* Will, volition (psychology)

* Will, a modal verb - see Shall and will

...

. Building on the transcendental idealism

Transcendental idealism is a philosophical system founded by German philosopher Immanuel Kant in the 18th century. Kant's epistemological program is found throughout his '' Critique of Pure Reason'' (1781). By ''transcendental'' (a term that des ...

of Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

, Schopenhauer developed an atheistic metaphysical and ethical system that rejected the contemporaneous ideas of German idealism

German idealism is a philosophical movement that emerged in Germany in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It developed out of the work of Immanuel Kant in the 1780s and 1790s, and was closely linked both with Romanticism and the revolutionary ...

.

Schopenhauer was among the first philosophers in the Western tradition to share and affirm significant tenets of Indian philosophy

Indian philosophy consists of philosophical traditions of the Indian subcontinent. The philosophies are often called darśana meaning, "to see" or "looking at." Ānvīkṣikī means “critical inquiry” or “investigation." Unlike darśan ...

, such as asceticism

Asceticism is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from worldly pleasures through self-discipline, self-imposed poverty, and simple living, often for the purpose of pursuing Spirituality, spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world ...

, denial of the self

In philosophy, the self is an individual's own being, knowledge, and values, and the relationship between these attributes.

The first-person perspective distinguishes selfhood from personal identity. Whereas "identity" is (literally) same ...

, and the notion of the world-as-appearance. His work has been described as an exemplary manifestation of philosophical pessimism

Philosophical pessimism is a philosophical tradition that argues that life is not worth living and that non-existence is preferable to existence. Thinkers in this tradition emphasize that suffering outweighs pleasure, happiness is fleeting or u ...

. Though his work failed to garner substantial attention during his lifetime, he had a posthumous impact across various disciplines, including philosophy, literature, and science. His writing on aesthetics

Aesthetics (also spelled esthetics) is the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature of beauty and taste (sociology), taste, which in a broad sense incorporates the philosophy of art.Slater, B. H.Aesthetics ''Internet Encyclopedia of Ph ...

, morality

Morality () is the categorization of intentions, Decision-making, decisions and Social actions, actions into those that are ''proper'', or ''right'', and those that are ''improper'', or ''wrong''. Morality can be a body of standards or principle ...

, and psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

has influenced many thinkers and artists.

Early life

Arthur Schopenhauer was born on 22 February 1788 in

Arthur Schopenhauer was born on 22 February 1788 in Gdańsk

Gdańsk is a city on the Baltic Sea, Baltic coast of northern Poland, and the capital of the Pomeranian Voivodeship. With a population of 486,492, Data for territorial unit 2261000. it is Poland's sixth-largest city and principal seaport. Gdań ...

(then part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

; later in the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (, ) was a German state that existed from 1701 to 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Rev. ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1946. It played a signif ...

as Danzig) on Św. Ducha 47 (in Prussia Heiliggeistgasse), the son of and his wife Johanna Schopenhauer (née Trosiener), both descendants of wealthy German patrician families. While they came from a Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

background, neither of them were very religious; both supported the French Revolution, were republicans, cosmopolitans, and Anglophiles. When Gdańsk became part of Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

in 1793, Heinrich moved to Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg,. is the List of cities in Germany by population, second-largest city in Germany after Berlin and List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, 7th-lar ...

—a free city with a republican constitution. His firm continued trading in Danzig, where most of their extended families remained. Adele

Adele Laurie Blue Adkins (; born 5 May 1988) is an English singer-songwriter. Regarded as a British cultural icon, icon, she is known for her mezzo-soprano vocals and sentimental songwriting. List of awards and nominations received by Adele, ...

, Arthur's only sibling, was born on 12 July 1797.

In 1797, Arthur was sent to Le Havre

Le Havre is a major port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy (administrative region), Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the Seine, river Seine on the English Channel, Channe ...

to live with the family of his father's business associate, Grégoire de Blésimaire. He seemed to enjoy his two-year stay there, learning to speak French and fostering a life-long friendship with Jean Anthime Grégoire de Blésimaire. As early as 1799, Arthur started playing the flute.

In 1803, he accompanied his parents on a European tour of Holland

Holland is a geographical regionG. Geerts & H. Heestermans, 1981, ''Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal. Deel I'', Van Dale Lexicografie, Utrecht, p 1105 and former provinces of the Netherlands, province on the western coast of the Netherland ...

, Britain, France, Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

, Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

, and Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

. Viewed as primarily a pleasure tour, Heinrich used the opportunity to visit some of his business associates abroad.

Heinrich presented Arthur with a choice: he could either stay at home to begin preparations for university or travel with them to further his merchant education. Arthur chose to travel with them. He deeply regretted his choice later because the merchant training was very tedious. He spent twelve weeks of the tour attending school in Wimbledon

Wimbledon most often refers to:

* Wimbledon, London, a district of southwest London

* Wimbledon Championships, the oldest tennis tournament in the world and one of the four Grand Slam championships

Wimbledon may also refer to:

Places London

* W ...

, where he was confused by strict and intellectual Anglicans, whom he described as shallow. He continued to sharply criticize Anglican religiosity later in life despite his general Anglophilia. He was also under pressure from his father, who became very critical of his educational results.

In 1805, Heinrich drowned in a canal near their home in Hamburg. Although it was possible that his death was accidental, his wife and son believed that it was suicide. He was prone to anxiety

Anxiety is an emotion characterised by an unpleasant state of inner wikt:turmoil, turmoil and includes feelings of dread over Anticipation, anticipated events. Anxiety is different from fear in that fear is defined as the emotional response ...

and depression, each becoming more pronounced later in his life. Heinrich had become so fussy that even his wife started to doubt his mental health. "There was, in the father's life, some dark and vague source of fear which later made him hurl himself to his death from the attic of his house in Hamburg."

Arthur showed similar moodiness during his youth and often acknowledged that he inherited it from his father. There were other instances of serious mental health problems on his father's side of the family. Despite his hardship, Schopenhauer liked his father and later referred to him in a positive light. Heinrich Schopenhauer left the family with a significant inheritance split in three among Johanna and the children. Arthur Schopenhauer was entitled to control of his part when he reached the age of majority. He invested it conservatively in government bonds and earned annual interest that was more than double the salary of a university professor. After quitting his merchant apprenticeship, with encouragement from his mother, he dedicated himself to studies at the Ernestine Gymnasium, Gotha, in Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg. While there, he also enjoyed a social life among the local nobility, spending large amounts of money, which deeply concerned his frugal mother. He left the Gymnasium after writing a satirical poem about one of the schoolmasters. Although Arthur claimed he left voluntarily, his mother's letter indicates that he may have been expelled.

Arthur spent two years as a merchant in honor of his dead father. During this time, he had doubts about being able to start a new life as a scholar. Most of his prior education was as a practical merchant and he had trouble learning Latin; a prerequisite for an academic career.

His mother moved away, with her daughter Adele, to

Arthur spent two years as a merchant in honor of his dead father. During this time, he had doubts about being able to start a new life as a scholar. Most of his prior education was as a practical merchant and he had trouble learning Latin; a prerequisite for an academic career.

His mother moved away, with her daughter Adele, to Weimar

Weimar is a city in the state (Germany), German state of Thuringia, in Central Germany (cultural area), Central Germany between Erfurt to the west and Jena to the east, southwest of Leipzig, north of Nuremberg and west of Dresden. Together w ...

—then the centre of German literature

German literature () comprises those literature, literary texts written in the German language. This includes literature written in Germany, Austria, the German parts of Switzerland and Belgium, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, South Tyrol in Italy ...

—to enjoy social life among writers and artists. Arthur and his mother did not part on good terms. In one letter, she wrote: "You are unbearable and burdensome, and very hard to live with; all your good qualities are overshadowed by your conceit, and made useless to the world simply because you cannot restrain your propensity to pick holes in other people." His mother, Johanna, was generally described as vivacious and sociable. She died 24 years later. Some of Arthur's negative opinions about women may be rooted in his troubled relationship with his mother.

Arthur moved to Hamburg to live with his friend Jean Anthime, who was also studying to become a merchant.

Education

He moved to Weimar but did not live with his mother, who even tried to discourage him from coming by explaining that they would not get along very well. Their relationship deteriorated even further due to their temperamental differences. He accused his mother of being financially irresponsible, flirtatious and seeking to remarry, which he considered an insult to his father's memory. His mother, while professing her love to him, criticized him sharply for being moody, tactless, and argumentative, and urged him to improve his behavior so that he would not alienate people. Arthur concentrated on his studies, which were now going very well, and he also enjoyed the usual social life such as balls, parties and theater. By that time Johanna's famous salon was well established among local intellectuals and dignitaries, the most celebrated of them beingGoethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

. Arthur attended her parties, usually when he knew that Goethe would be there—although the famous writer and statesman seemed not even to notice the young and unknown student. It is possible that Goethe kept a distance because Johanna warned him about her son's depressive and combative nature, or because Goethe was then on bad terms with Arthur's language instructor and roommate, Franz Passow. Schopenhauer was also captivated by the beautiful Karoline Jagemann, mistress of Karl August, Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, and he wrote to her his only known love poem. Despite his later celebration of asceticism and negative views of sexuality, Schopenhauer occasionally had sexual affairs—usually with women of lower social status, such as servants, actresses, and sometimes even paid prostitutes. In a letter to his friend Anthime he claims that such affairs continued even in his mature age and admits that he had two out-of-wedlock daughters (born in 1819 and 1836), both of whom died in infancy. In their youthful correspondence Arthur and Anthime were somewhat boastful and competitive about their sexual exploits—but Schopenhauer seemed aware that women usually did not find him very charming or physically attractive, and his desires often remained unfulfilled.

He left Weimar to become a student at the University of Göttingen

The University of Göttingen, officially the Georg August University of Göttingen (, commonly referred to as Georgia Augusta), is a Public university, public research university in the city of Göttingen, Lower Saxony, Germany. Founded in 1734 ...

in 1809. There are no written reasons about why Schopenhauer chose that university instead of the then more famous University of Jena

The University of Jena, officially the Friedrich Schiller University Jena (, abbreviated FSU, shortened form ''Uni Jena''), is a public research university located in Jena, Thuringia, Germany.

The university was established in 1558 and is cou ...

, but Göttingen was known as more modern and scientifically oriented, with less attention given to theology. Law or medicine were usual choices for young men of Schopenhauer's status who also needed career and income; he chose medicine due to his scientific interests. Among his notable professors were Bernhard Friedrich Thibaut, Arnold Hermann Ludwig Heeren, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach

Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (11 May 1752 – 22 January 1840) was a German physician, naturalist, physiologist and anthropologist. He is considered to be a main founder of zoology and anthropology as comparative, scientific disciplines. He has be ...

, Friedrich Stromeyer, Heinrich Adolf Schrader, Johann Tobias Mayer and Konrad Johann Martin Langenbeck. He studied metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of ...

, psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

and logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

under Gottlob Ernst Schulze, the author of '' Aenesidemus'', who made a strong impression and advised him to concentrate on Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

and Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

. He decided to switch from medicine to philosophy around 1810–11 and he left Göttingen, which did not have a strong philosophy program: besides Schulze, the only other philosophy professor was Friedrich Bouterwek, whom Schopenhauer disliked. He did not regret his medicinal and scientific studies; he claimed that they were necessary for a philosopher, and even in Berlin he attended more lectures in sciences than in philosophy. During his days at Göttingen, he spent considerable time studying, but also continued his flute playing and social life. His friends included Friedrich Gotthilf Osann, Karl Witte, Christian Charles Josias von Bunsen

Christian Charles Josias, Baron von Bunsen (; 25 August 1791 – 28 November 1860), was a German diplomat and scholar. He worked in the Papal States and England for a large part of his career.

Life Early life

Bunsen was born at Korbach, a ...

, and William Backhouse Astor Sr.

He arrived at the newly founded University of Berlin

The Humboldt University of Berlin (, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin, Germany.

The university was established by Frederick William III on the initiative of Wilhelm von Humbol ...

for the winter semester of 1811–12. At the same time, his mother had just begun her literary career; she published her first book in 1810, a biography of her friend Karl Ludwig Fernow, which was a critical success. Arthur attended lectures by the prominent post-Kantian philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte

Johann Gottlieb Fichte (; ; 19 May 1762 – 29 January 1814) was a German philosopher who became a founding figure of the philosophical movement known as German idealism, which developed from the theoretical and ethical writings of Immanuel Ka ...

, but quickly found many points of disagreement with his epistemology; he also found Fichte's lectures tedious and hard to understand. He later mentioned Fichte only in critical, negative terms—seeing his philosophy as a lower-quality version of Kant's and considering it useful only because Fichte's poor arguments unintentionally highlighted some failings of Kantianism. He also attended the lectures of the famous Protestant theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher, whom he also quickly came to dislike. His notes and comments on Schleiermacher's lectures show that Schopenhauer was becoming very critical of religion and moving towards atheism

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the Existence of God, existence of Deity, deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the ...

. He learned by self-directed reading; besides Plato, Kant and Fichte he also read the works of Schelling, Fries

French fries, or simply fries, also known as chips, and finger chips (Indian English), are ''List of culinary knife cuts#Batonnet, batonnet'' or ''Julienning, julienne''-cut deep frying, deep-fried potatoes of disputed origin. They are prepa ...

, Jacobi, Bacon

Bacon is a type of Curing (food preservation), salt-cured pork made from various cuts of meat, cuts, typically the pork belly, belly or less fatty parts of the back. It is eaten as a side dish (particularly in breakfasts), used as a central in ...

, Locke, and much current scientific literature. He attended philological courses by August Böckh and Friedrich August Wolf and continued his naturalistic interests with courses by Martin Heinrich Klaproth, Paul Erman, Johann Elert Bode, Ernst Gottfried Fischer, Johann Horkel, Friedrich Christian Rosenthal and Hinrich Lichtenstein

Martin H nrich Carl Lichtenstein (10 January 1780 – 2 September 1857) was a German physician, List of explorers, explorer, botanist and zoologist. He explored parts of southern Africa and collected natural history specimens extensively and ...

(Lichtenstein was also a friend whom he met at one of his mother's parties in Weimar).

Early work

Schopenhauer left Berlin in a rush in 1813, fearing that the city could be attacked and that he could be pressed into military service as Prussia had just joined the war against France. He returned to Weimar but left after less than a month, disgusted by the fact that his mother was now living with her supposed lover, , a civil servant twelve years younger than she; he considered the relationship an act of infidelity to his father's memory. He settled for a while in Rudolstadt, hoping that no army would pass through the small town. He spent his time in solitude, hiking in the mountains and theThuringian Forest

The Thuringian Forest (''Thüringer Wald'' in German language, German ) is a mountain range in the southern parts of the Germany, German state of Thuringia, running northwest to southeast. Skirting from its southerly source in foothills to a gorg ...

and writing his dissertation, ''On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason

''On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason'' () is an elaboration on the classical principle of sufficient reason, written by German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer as his doctoral dissertation in 1813. The principle of sufficie ...

''.

Schopenhauer completed his dissertation at about the same time as the French army was defeated at the Battle of Leipzig. He became irritated by the arrival of soldiers in the town and accepted his mother's invitation to visit her in Weimar. She tried to convince him that her relationship with Gerstenbergk was platonic and that she had no intention of remarrying. But Schopenhauer remained suspicious and often came in conflict with Gerstenbergk because he considered him untalented, pretentious, and nationalistic. His mother had just published her second book, ''Reminiscences of a Journey in the Years 1803, 1804, and 1805'', a description of their family tour of Europe, which quickly became a hit. She found his dissertation incomprehensible and said it was unlikely that anyone would ever buy a copy. In a fit of temper Arthur told her that people would read his work long after the "rubbish" she wrote was totally forgotten. In fact, although they considered her novels of dubious quality, the Brockhaus publishing firm held her in high esteem because they consistently sold well. Hans Brockhaus later claimed that his predecessors "saw nothing in this manuscript, but wanted to please one of our best-selling authors by publishing her son's work. We published more and more of her son Arthur's work and today nobody remembers Johanna, but her son's works are in steady demand and contribute to Brockhaus' reputation." He kept large portraits of the pair in his office in Leipzig

Leipzig (, ; ; Upper Saxon: ; ) is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Saxony. The city has a population of 628,718 inhabitants as of 2023. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, eighth-largest city in Ge ...

for the edification of his new editors.

Also contrary to his mother's prediction, Schopenhauer's dissertation made an impression on Goethe, to whom he sent it as a gift. Although it is doubtful that Goethe agreed with Schopenhauer's philosophical positions, he was impressed by his intellect and extensive scientific education. Their subsequent meetings and correspondence were a great honor to a young philosopher, who was finally acknowledged by his intellectual hero. They mostly discussed Goethe's newly published (and somewhat lukewarmly received) work on color theory

Color theory, or more specifically traditional color theory, is a historical body of knowledge describing the behavior of colors, namely in color mixing, color contrast effects, color harmony, color schemes and color symbolism. Modern color th ...

. Schopenhauer soon started writing his own treatise on the subject, ''On Vision and Colors

''On Vision and Colors'' (originally translated as ''On Vision and Colours''; ) is a treatise by Arthur Schopenhauer that was published in May 1816 when the author was 28 years old. Schopenhauer had extensive discussions with Johann Wolfgang von G ...

'', which in many points differed from his teacher's. Although they remained polite towards each other, their growing theoretical disagreements—and especially Schopenhauer's extreme self-confidence and tactless criticisms—soon made Goethe become distant again and after 1816 their correspondence became less frequent. Schopenhauer later admitted that he was greatly hurt by this rejection, but he continued to praise Goethe, and considered his color theory a great introduction to his own.

Another important experience during his stay in Weimar was his acquaintance with Friedrich Majer—a historian of religion, orientalist and disciple of Herder

A herder is a pastoralism, pastoral worker responsible for the care and management of a herd or flock of domestic animals, usually on extensive management, open pasture. It is particularly associated with nomadic pastoralism, nomadic or transhuma ...

—who introduced him to Eastern philosophy

Eastern philosophy (also called Asian philosophy or Oriental philosophy) includes the various philosophies that originated in East and South Asia, including Chinese philosophy, Japanese philosophy, Korean philosophy, and Vietnamese philoso ...

(see also Indology). Schopenhauer was immediately impressed by the ''Upanishads

The Upanishads (; , , ) are late Vedic and post-Vedic Sanskrit texts that "document the transition from the archaic ritualism of the Veda into new religious ideas and institutions" and the emergence of the central religious concepts of Hind ...

'' (he called them "the production of the highest human wisdom", and believed that they contained superhuman concepts) and the Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha (),*

*

*

was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism. According to Buddhist legends, he was ...

, and put them on a par with Plato and Kant. He continued his studies by reading the ''Bhagavad Gita

The Bhagavad Gita (; ), often referred to as the Gita (), is a Hindu texts, Hindu scripture, dated to the second or first century BCE, which forms part of the Hindu epic, epic poem Mahabharata. The Gita is a synthesis of various strands of Ind ...

'', an amateurish German journal ''Asiatisches Magazin'', and ''Asiatick Researches'' by the Asiatic Society. Schopenhauer held a profound respect for Indian philosophy

Indian philosophy consists of philosophical traditions of the Indian subcontinent. The philosophies are often called darśana meaning, "to see" or "looking at." Ānvīkṣikī means “critical inquiry” or “investigation." Unlike darśan ...

; and loved Hindu texts

Hindu texts or Hindu scriptures are manuscripts and voluminous historical literature which are related to any of the diverse traditions within Hinduism. Some of the major Hindus, Hindu texts include the Vedas, the Upanishads, and the Itihasa. ...

. Although he never revered a Buddhist text he regarded Buddhism

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

as the most distinguished religion. His studies on Hindu and Buddhist texts were constrained by the lack of adequate literature, and the latter were mostly restricted to Theravada Buddhism. He also claimed that he formulated most of his ideas independently, and only later realized the similarities with Buddhism.

Schopenhauer read the Latin translation and praised the Upanishads in his main work, '' The World as Will and Representation'' (1819), as well as in his '' Parerga and Paralipomena'' (1851), and commented

In the whole world there is no study so beneficial and so elevating as that of the Upanishads. It has been the solace of my life, it will be the solace of my death.As the relationship with his mother fell to a new low, in May 1814 he left Weimar and moved to

Dresden

Dresden (; ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; , ) is the capital city of the States of Germany, German state of Saxony and its second most populous city after Leipzig. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, 12th most p ...

. He continued his philosophical studies, enjoyed the cultural life, socialized with intellectuals and engaged in sexual affairs. His friends in Dresden were Johann Gottlob von Quandt, Friedrich Laun, Karl Christian Friedrich Krause and Ludwig Sigismund Ruhl, a young painter who made a romanticized portrait of him in which he improved some of Schopenhauer's unattractive physical features. His criticisms of local artists occasionally caused public quarrels when he ran into them in public. Schopenhauer's main occupation during his stay in Dresden was his seminal philosophical work, '' The World as Will and Representation'', which he started writing in 1814 and finished in 1818. He was recommended to the publisher Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus

Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus (4 May 1772 – 20 August 1823) was a German encyclopedia publisher and editor, famed for publishing the '' Conversations-Lexikon'', which is now published as the Brockhaus encyclopedia.

Biography

Brockhaus was edu ...

by Baron Ferdinand von Biedenfeld, an acquaintance of his mother. Although Brockhaus accepted his manuscript, Schopenhauer made a poor impression because of his quarrelsome and fussy attitude, as well as very poor sales of the book after it was published in December 1818.

In September 1818, while waiting for his book to be published and conveniently escaping an affair with a maid that caused an unwanted pregnancy, Schopenhauer left Dresden for a year-long vacation in Italy. He visited Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

, Bologna

Bologna ( , , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in northern Italy. It is the List of cities in Italy, seventh most populous city in Italy, with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nationalities. Its M ...

, Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

, Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

and Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

, travelling alone or accompanied by mostly English tourists he met. He spent the winter months in Rome, where he accidentally met his acquaintance Karl Witte and engaged in numerous quarrels with German tourists in the Caffè Greco, among them Johann Friedrich Böhmer, who also mentioned his insulting remarks and unpleasant character. He enjoyed art, architecture, and ancient ruins, attended plays and operas, and continued his philosophical contemplation and love affairs. One of his affairs supposedly became serious, and for a while he contemplated marriage to a rich Italian noblewoman—but, despite his mentioning this several times, no details are known and it may have been Schopenhauer exaggerating. He corresponded regularly with his sister Adele and became close to her as her relationship with Johanna and Gerstenbergk also deteriorated. She informed him about their financial troubles as the banking house of A. L. Muhl in Danzig—in which her mother invested their whole savings and Arthur a third of his—was near bankruptcy. Arthur offered to share his assets, but his mother refused and became further enraged by his insulting comments. The women managed to receive only thirty percent of their savings while Arthur, using his business knowledge, took a suspicious and aggressive stance towards the banker and eventually received his part in full. The affair additionally worsened the relationships among all three members of the Schopenhauer family.

He shortened his stay in Italy because of the trouble with Muhl and returned to Dresden. Disturbed by the financial risk and the lack of responses to his book he decided to take an academic position since it provided him with both income and an opportunity to promote his views. He contacted his friends at universities in Heidelberg, Göttingen and Berlin and found Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

most attractive. He scheduled his lectures to coincide with those of the famous philosopher G. W. F. Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a 19th-century German idealism, German idealist. His influence extends across a wide range of topics from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political phi ...

, whom Schopenhauer described as a "clumsy charlatan". He was especially appalled by Hegel's supposedly poor knowledge of natural sciences and tried to engage him in a quarrel about it already at his test lecture in March 1820. Hegel was also facing political suspicions at the time, when many progressive professors were fired, while Schopenhauer carefully mentioned in his application that he had no interest in politics. Despite their differences and the arrogant request to schedule lectures at the same time as his own, Hegel still voted to accept Schopenhauer to the university. Only five students turned up to Schopenhauer's lectures, and he dropped out of academia

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of tertiary education. The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, founded approximately 386 BC at Akademia, a sanctuary of Athena, the go ...

. A late essay, "On University Philosophy", expressed his resentment towards the work conducted in academies.

Later life

After his efforts in academia, he continued to travel extensively, visiting

After his efforts in academia, he continued to travel extensively, visiting Leipzig

Leipzig (, ; ; Upper Saxon: ; ) is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Saxony. The city has a population of 628,718 inhabitants as of 2023. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, eighth-largest city in Ge ...

, Nuremberg

Nuremberg (, ; ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the Franconia#Towns and cities, largest city in Franconia, the List of cities in Bavaria by population, second-largest city in the States of Germany, German state of Bav ...

, Stuttgart

Stuttgart (; ; Swabian German, Swabian: ; Alemannic German, Alemannic: ; Italian language, Italian: ; ) is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, largest city of the States of Germany, German state of ...

, Schaffhausen

Schaffhausen (; ; ; ; ), historically known in English as Shaffhouse, is a list of towns in Switzerland, town with historic roots, a municipalities of Switzerland, municipality in northern Switzerland, and the capital of the canton of Schaffh ...

, Vevey

Vevey (; ; ) is a town in Switzerland in the Vaud, canton of Vaud, on the north shore of Lake Leman, near Lausanne. The German name Vivis is no longer commonly used.

It was the seat of the Vevey (district), district of the same name until 200 ...

, Milan and spending eight months in Florence. Before he left for his three-year travel, Schopenhauer had an incident with his Berlin neighbor, 47-year-old seamstress Caroline Louise Marquet. The details of the August 1821 incident are unknown. He claimed that he had just pushed her from his entrance after she had rudely refused to leave, and that she had purposely fallen to the ground so that she could sue him. She claimed that he had attacked her so violently that she had become paralyzed on her right side and unable to work. She immediately sued him, and the court case lasted until May 1827, when a court found Schopenhauer guilty and forced him to pay her an annual pension until her death in 1842.

Schopenhauer enjoyed Italy, where he studied art and socialized with Italian and English nobles. It was his last visit to the country. He left for Munich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

and stayed there for a year, mostly recuperating from various health problems, some of them possibly caused by venereal diseases (the treatment his doctor used suggests syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms depend on the stage it presents: primary, secondary, latent syphilis, latent or tertiary. The prim ...

). He contacted publishers, offering to translate Hume into German and Kant into English, but his proposals were declined. Returning to Berlin, he began to study Spanish so he could read some of his favorite authors in their original language. He liked Pedro Calderón de la Barca

Pedro Calderón de la Barca y Barreda González de Henao Ruiz de Blasco y Riaño (17 January 160025 May 1681) (, ; ) was a Spanish dramatist, poet, and writer. He is known as one of the most distinguished Spanish Baroque literature, poets and ...

, Lope de Vega

Félix Lope de Vega y Carpio (; 25 November 156227 August 1635) was a Spanish playwright, poet, and novelist who was a key figure in the Spanish Golden Age (1492–1659) of Spanish Baroque literature, Baroque literature. In the literature of ...

, Miguel de Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra ( ; ; 29 September 1547 (assumed) – 22 April 1616 Old Style and New Style dates, NS) was a Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelist ...

, and especially Baltasar Gracián

Baltasar Gracián y Morales (; 8 January 16016 December 1658), better known as Baltasar Gracián, was a Spanish Jesuit priest and Spanish Baroque literature, Baroque prose writer and philosopher. He was born in Belmonte de Gracián, Belmonte, n ...

. He also made failed attempts to publish his translations of their works. A few attempts to revive his lectures—again scheduled at the same time as Hegel's—also failed, as did his inquiries about relocating to other universities.

During his Berlin years, Schopenhauer occasionally mentioned his desire to marry and have a family. For a while he was unsuccessfully courting 17-year-old Flora Weiss, who was 22 years younger than himself. His unpublished writings from that time show that he was already very critical of monogamy

Monogamy ( ) is a social relation, relationship of Dyad (sociology), two individuals in which they form a mutual and exclusive intimate Significant other, partnership. Having only one partner at any one time, whether for life or #Serial monogamy ...

but still not advocating polygyny

Polygyny () is a form of polygamy entailing the marriage of a man to several women. The term polygyny is from Neoclassical Greek πολυγυνία (); .

Incidence

Polygyny is more widespread in Africa than in any other continent. Some scholar ...

—instead musing about a polyamorous relationship that he called "tetragamy". He had an on-and-off relationship with a young dancer, Caroline Richter (she also used the surname Medon after one of her ex-lovers). They met when he was 33 and she was 19 and working at the Berlin Opera. She had already had numerous lovers and a son out of wedlock, and later gave birth to another son, this time to an unnamed foreign diplomat (she soon had another pregnancy but the child was stillborn). As Schopenhauer was preparing to escape from Berlin in 1831, due to a cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

epidemic, he offered to take her with him on the condition that she left her young son behind. She refused and he went alone; in his will he left her a significant sum of money, but insisted that it should not be spent in any way on her second son.

Schopenhauer claimed that, in his last year in Berlin, he had a prophetic dream that urged him to escape from the city. As he arrived in his new home in Frankfurt

Frankfurt am Main () is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Hesse. Its 773,068 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the List of cities in Germany by population, fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located in the forela ...

, he supposedly had another supernatural experience, an apparition of his dead father and his mother, who was still alive. This experience led him to spend some time investigating paranormal

Paranormal events are purported phenomena described in popular culture, folk, and other non-scientific bodies of knowledge, whose existence within these contexts is described as being beyond the scope of normal scientific understanding. Not ...

phenomena and magic. He was quite critical of the available studies and claimed that they were mostly ignorant or fraudulent, but he did believe that there are authentic cases of such phenomena and tried to explain them through his metaphysics as manifestations of the will.

Upon his arrival in Frankfurt, he experienced a period of depression and declining health. He renewed his correspondence with his mother, and she seemed concerned that he might commit suicide like his father. By now Johanna and Adele were living very modestly. Johanna's writing did not bring her much income, and her popularity was waning. Their correspondence remained reserved, and Arthur seemed undisturbed by her death in 1838. His relationship with his sister grew closer and he corresponded with her until she died in 1849.

In July 1832, Schopenhauer left Frankfurt for Mannheim

Mannheim (; Palatine German language, Palatine German: or ), officially the University City of Mannheim (), is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, second-largest city in Baden-Württemberg after Stuttgart, the States of Ger ...

but returned in July 1833 to remain there for the rest of his life, except for a few short journeys. He lived alone except for a succession of pet poodles named Atman and Butz. In 1836, he published ''On the Will in Nature''. In 1838, he sent his essay " On the Freedom of the Will" to the contest of the Royal Norwegian Society of Sciences in 1838 and won the prize in 1839. He sent another essay, " On the Basis of Morality", to the Royal Danish Society of Sciences in 1839, but did not win the (1840) prize despite being the only contestant. The Society was appalled that several distinguished contemporary philosophers were mentioned in a very offensive manner, and claimed that the essay missed the point of the set topic and that the arguments were inadequate. Schopenhauer, who had been very confident that he would win, was enraged by this rejection. He published both essays as ''The Two Basic Problems of Ethics''. The first edition, published September 1840 but with an 1841 date, again failed to draw attention to his philosophy. In the preface to the second edition, in 1860, he was still pouring insults on the Royal Danish Society. Two years later, after some negotiations, he managed to convince his publisher, Brockhaus, to print the second, updated edition of ''The World as Will and Representation''. That book was again mostly ignored and the few reviews were mixed or negative.

Schopenhauer began to attract some followers, mostly outside academia, among practical professionals (several of them were lawyers) who pursued private philosophical studies. He jokingly referred to them as "evangelists" and "apostles". One of the most active early followers was Julius Frauenstädt, who wrote numerous articles promoting Schopenhauer's philosophy. He was also instrumental in finding another publisher after Brockhaus declined to publish ''Parerga and Paralipomena'', believing that it would be another failure. Though Schopenhauer later stopped corresponding with him, claiming that he did not adhere closely enough to his ideas, Frauenstädt continued to promote Schopenhauer's work. They renewed their communication in 1859 and Schopenhauer named him heir for his literary estate. Frauenstädt also became the editor of the first collected works of Schopenhauer.

In 1848, Schopenhauer witnessed violent upheaval in Frankfurt after General Hans Adolf Erdmann von Auerswald and Prince Felix Lichnowsky were murdered. He became worried for his own safety and property. Even earlier in life he had had such worries and kept a sword and loaded pistols near his bed to defend himself from thieves. He gave a friendly welcome to Austrian soldiers who wanted to shoot revolutionaries from his window and as they were leaving he gave one of the officers his opera glasses to help him monitor rebels. The rebellion passed without any loss to Schopenhauer and he later praised Alfred I, Prince of Windisch-Grätz for restoring order. He even modified his will, leaving a large part of his property to a Prussian fund that helped soldiers who became invalids while fighting rebellion in 1848 or the families of soldiers who died in battle. As Young Hegelians were advocating change and progress, Schopenhauer claimed that misery is natural for humans and that, even if some utopian society were established, people would still fight each other out of boredom, or would starve due to overpopulation.

In 1851, Schopenhauer published '' Parerga and Paralipomena'', which contains essays that are supplementary to his main work. It was his first successful, widely read book, partly due to the work of his disciples who wrote praising reviews. The essays that proved most popular were the ones that actually did not contain the basic philosophical ideas of his system. Many academic philosophers considered him a great stylist and cultural critic but did not take his philosophy seriously. His early critics liked to point out similarities of his ideas to those of Fichte and Schelling, or to claim that there were numerous contradictions in his philosophy. Both criticisms enraged Schopenhauer. He was becoming less interested in intellectual fights, but encouraged his disciples to do so. His private notes and correspondence show that he acknowledged some of the criticisms regarding contradictions, inconsistencies, and vagueness in his philosophy, but claimed that he was not concerned about harmony and agreement in his propositions and that some of his ideas should not be taken literally but instead as metaphors.

Academic philosophers were also starting to notice his work. In 1856, the University of Leipzig sponsored an essay contest about Schopenhauer's philosophy, which was won by Rudolf Seydel's very critical essay. Schopenhauer's friend Jules Lunteschütz made the first of his four portraits of him—which Schopenhauer did not particularly like—which was soon sold to a wealthy landowner, Carl Ferdinand Wiesike, who built a house to display it. Schopenhauer seemed flattered and amused by this, and would claim that it was his first chapel. As his fame increased, copies of paintings and photographs of him were being sold and admirers were visiting the places where he had lived and written his works. People visited Frankfurt's ''Englischer Hof'' to observe him dining. Admirers gave him gifts and asked for autographs. He complained that he still felt isolated due to his not very social nature and the fact that many of his good friends had already died from old age.

In 1851, Schopenhauer published '' Parerga and Paralipomena'', which contains essays that are supplementary to his main work. It was his first successful, widely read book, partly due to the work of his disciples who wrote praising reviews. The essays that proved most popular were the ones that actually did not contain the basic philosophical ideas of his system. Many academic philosophers considered him a great stylist and cultural critic but did not take his philosophy seriously. His early critics liked to point out similarities of his ideas to those of Fichte and Schelling, or to claim that there were numerous contradictions in his philosophy. Both criticisms enraged Schopenhauer. He was becoming less interested in intellectual fights, but encouraged his disciples to do so. His private notes and correspondence show that he acknowledged some of the criticisms regarding contradictions, inconsistencies, and vagueness in his philosophy, but claimed that he was not concerned about harmony and agreement in his propositions and that some of his ideas should not be taken literally but instead as metaphors.

Academic philosophers were also starting to notice his work. In 1856, the University of Leipzig sponsored an essay contest about Schopenhauer's philosophy, which was won by Rudolf Seydel's very critical essay. Schopenhauer's friend Jules Lunteschütz made the first of his four portraits of him—which Schopenhauer did not particularly like—which was soon sold to a wealthy landowner, Carl Ferdinand Wiesike, who built a house to display it. Schopenhauer seemed flattered and amused by this, and would claim that it was his first chapel. As his fame increased, copies of paintings and photographs of him were being sold and admirers were visiting the places where he had lived and written his works. People visited Frankfurt's ''Englischer Hof'' to observe him dining. Admirers gave him gifts and asked for autographs. He complained that he still felt isolated due to his not very social nature and the fact that many of his good friends had already died from old age.

He remained healthy in his own old age, which he attributed to regular walks no matter the weather and always getting enough sleep. He had a great appetite and could read without glasses, but his

He remained healthy in his own old age, which he attributed to regular walks no matter the weather and always getting enough sleep. He had a great appetite and could read without glasses, but his hearing

Hearing, or auditory perception, is the ability to perceive sounds through an organ, such as an ear, by detecting vibrations as periodic changes in the pressure of a surrounding medium. The academic field concerned with hearing is auditory sci ...

had been declining since his youth and he developed problems with rheumatism

Rheumatism or rheumatic disorders are conditions causing chronic, often intermittent pain affecting the joints or connective tissue. Rheumatism does not designate any specific disorder, but covers at least 200 different conditions, including a ...

. He remained active and lucid, continued his reading, writing and correspondence until his death. The numerous notes that he made during these years, amongst others on aging, were published posthumously

Posthumous may refer to:

* Posthumous award, an award, prize or medal granted after the recipient's death

* Posthumous publication, publishing of creative work after the author's death

* Posthumous (album), ''Posthumous'' (album), by Warne Marsh, 1 ...

under the title ''Senilia''. In the spring of 1860 his health began to decline, and he experienced shortness of breath and heart palpitations; in September he suffered inflammation of the lungs and, although he was starting to recover, he remained very weak. The last friend to visit him was Wilhelm Gwinner; according to him, Schopenhauer was concerned that he would not be able to finish his planned additions to ''Parerga and Paralipomena'' but was at peace with dying. He died of pulmonary-respiratory failure on 21 September 1860 while sitting at home on his couch. He died at the age of 72 and had a funeral conducted by a Lutheran minister.

Philosophy

Theory of perception

In November 1813Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

invited Schopenhauer to help him on his Theory of Colours

''Theory of Colours'' () is a book by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe about the poet's views on the nature of colours and how they are perceived by humans. It was published in German in 1810 and in English in 1840. The book contains detailed descri ...

. Although Schopenhauer considered colour theory a minor matter, he accepted the invitation out of admiration for Goethe. Nevertheless, these investigations led him to his most important discovery in epistemology: finding a demonstration for the ''a priori'' nature of causality.

Kant openly admitted that it was Hume's skeptical assault on causality that motivated the critical investigations in ''Critique of Pure Reason

The ''Critique of Pure Reason'' (; 1781; second edition 1787) is a book by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, in which the author seeks to determine the limits and scope of metaphysics. Also referred to as Kant's "First Critique", it was foll ...

'' and gave an elaborate proof to show that causality is ''a priori''. After G. E. Schulze had made it plausible that Kant had not disproven Hume's skepticism, it was up to those loyal to Kant's project to prove this important matter.

The difference between the approaches of Kant and Schopenhauer was this: Kant simply declared that the empirical content of perception is "given" to us from outside, an expression with which Schopenhauer often expressed his dissatisfaction. He, on the other hand, was occupied with the questions: how do we get this empirical content of perception; how is it possible to comprehend subjective sensations "limited to my skin" as the objective perception of things that lie "outside" of me?

Causality is therefore not an empirical concept drawn from objective perceptions, as Hume had maintained; instead, as Kant had said, objective perception presupposes knowledge of causality.

By this intellectual operation, comprehending every effect in our sensory organs as having an external cause, the external world arises. With vision, finding the cause is essentially simplified due to light acting in straight lines. We are seldom conscious of the process that interprets the double sensation in both eyes as coming from one object, that inverts the impressions on the retinas, and that uses the change in the apparent position of an object relative to more distant objects provided by binocular vision to perceive depth and distance.

Schopenhauer stresses the importance of the intellectual nature of perception; the senses furnish the raw material by which the intellect produces the world as representation. He set out his theory of perception for the first time in ''On Vision and Colors

''On Vision and Colors'' (originally translated as ''On Vision and Colours''; ) is a treatise by Arthur Schopenhauer that was published in May 1816 when the author was 28 years old. Schopenhauer had extensive discussions with Johann Wolfgang von G ...

'', and, in the subsequent editions of ''Fourfold Root'', an extensive exposition is given in § 21.

World as representation

Schopenhauer saw his philosophy as an extension of Kant's, and used the results of Kant's theoretical and epistemological investigations (transcendental idealism

Transcendental idealism is a philosophical system founded by German philosopher Immanuel Kant in the 18th century. Kant's epistemological program is found throughout his '' Critique of Pure Reason'' (1781). By ''transcendental'' (a term that des ...

) as starting point for his own. Kant had argued that the empirical

Empirical evidence is evidence obtained through sense experience or experimental procedure. It is of central importance to the sciences and plays a role in various other fields, like epistemology and law.

There is no general agreement on how t ...

world is merely a complex of appearances whose existence and connection occur only in our mental representation

A mental representation (or cognitive representation), in philosophy of mind, cognitive psychology, neuroscience, and cognitive science, is a hypothetical internal cognitive symbol that represents external reality or its abstractions.

Mental re ...

s. Schopenhauer did not deny that the external world existed and was known empirically, yet he followed Kant in claiming that our knowledge and experience of the world is always in some sense dependent on ''us''. For Schopenhauer in particular, the spatiotemporal form and causal structure of the external world are contributed to our experiences of it by the mind as it renders perceptions. Schopenhauer reiterates this in the first sentence of his main work: "The world is my representation (''Die Welt ist meine Vorstellung'')". Everything that there is for cognition (the entire world) exists simply as an object in relation to a subject—a 'representation' to a subject. Everything that belongs to the world is, therefore, 'subject-dependent'. In Book One of ''The World as Will and Representation'', Schopenhauer considers the world from this angle—that is, insofar as it is representation.

Kant had previously argued that we perceive reality as something spatial and temporal not because reality is inherently spatial and temporal, but because that is how our minds operate in perceiving an object. Therefore, understanding objects in space and time represents our 'contribution' to an experience. For Schopenhauer, Kant's 'greatest service' lay in the 'differentiation between phenomena

A phenomenon ( phenomena), sometimes spelled phaenomenon, is an observable Event (philosophy), event. The term came into its modern Philosophy, philosophical usage through Immanuel Kant, who contrasted it with the noumenon, which ''cannot'' be ...

and the thing-in-itself ( noumena), based on the proof that between everything and us there is always a perceiving mind.' In other words, Kant's primary achievement is to demonstrate that instead of being a blank slate where reality merely reveals its character, the mind, with sensory support, actively participates in constructing reality. Thus, Schopenhauer believed that Kant had shown that the everyday world of experience, and indeed the entire material world related to space and time, is merely 'appearance' or 'phenomena,' entirely distinct from the thing-in-itself.'

World as will

In Book Two of ''The World as Will and Representation'', Schopenhauer considers what the world is beyond the aspect of it that appears to us—that is, the aspect of the world beyond representation, the world considered " in-itself" or " noumena", its inner essence. The very being in-itself of all things, Schopenhauer argues, is will (''Wille''). The empirical world that appears to us as representation has plurality and is ordered in a spatio-temporal framework. The world as thing in-itself must exist outside the subjective forms of space and time. Although the world manifests itself to our experience as a multiplicity of objects (the "objectivation" of the will), each element of this multiplicity has the same blind essence striving towards existence and life. Human rationality is merely a secondary phenomenon that does not distinguish humanity from the rest of nature at the fundamental, essential level. The advanced cognitive abilities of human beings, Schopenhauer argues, serve the ends of willing—an illogical, directionless, ceaseless striving that condemns the human individual to a life of suffering unredeemed by any final purpose. Schopenhauer's philosophy of the will as the essential reality behind the world as representation is often called metaphysical voluntarism. For Schopenhauer, understanding the world as will leads to ethical concerns (see the ethics section below for further detail), which he explores in the Fourth Book of ''The World as Will and Representation'' and again in his two prize essays on ethics, '' On the Freedom of the Will'' and '' On the Basis of Morality''. No individual human actions are free, Schopenhauer argues, because they are events in the world of appearance and thus are subject to the principle of sufficient reason: a person's actions are a necessary consequence of motives and the given character of the individual human. Necessity extends to the actions of human beings just as it does to every other appearance, and thus we cannot speak of freedom of individual willing. Albert Einstein quoted the Schopenhauerian idea that "a man can ''do'' as he will, but not ''will'' as he will." Yet the will as thing in-itself is free, as it exists beyond the realm of representation and thus is not constrained by any of the forms of necessity that are part of the principle of sufficient reason. According to Schopenhauer, salvation from our miserable existence can come through the will's being "tranquillized" by the metaphysical insight that reveals individuality to be merely an illusion. The saint or 'great soul' intuitively "recognizes the whole, comprehends its essence, and finds that it is constantly passing away, caught up in vain strivings, inner conflict, and perpetual suffering". The negation of the will, in other words, stems from the insight that the world in-itself (free from the forms of space and time) is one. Ascetic practices, Schopenhauer remarks, are used to aid the will's "self-abolition", which brings about a blissful, redemptive "will-less" state of emptiness that is free from striving or suffering.Art and aesthetics

For Schopenhauer, human "willing"—desiring, craving, etc.—is at the root of

For Schopenhauer, human "willing"—desiring, craving, etc.—is at the root of suffering

Suffering, or pain in a broad sense, may be an experience of unpleasantness or aversion, possibly associated with the perception of harm or threat of harm in an individual. Suffering is the basic element that makes up the negative valence (psyc ...