Arius on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Arius (; grc-koi, Ἄρειος, ; 250 or 256 – 336) was a

Cyrenaic

The Cyrenaics or Kyrenaics ( grc, Κυρηναϊκοί, Kyrēnaïkoí), were a sensual hedonist Greek school of philosophy founded in the 4th century BCE, supposedly by Aristippus of Cyrene, although many of the principles of the school are belie ...

presbyter

Presbyter () is an honorific title for Christian clergy. The word derives from the Greek ''presbyteros,'' which means elder or senior, although many in the Christian antiquity would understand ''presbyteros'' to refer to the bishop functioning a ...

, ascetic, and priest best known for the doctrine of Arianism. His teachings about the nature of the Godhead in Christianity

Godhead (or '' godhood'') refers to the essence or substance (''ousia'') of the Christian God, especially as existing in three persons — God the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.God the Father's uniqueness and Christ's subordination under the Father, and his

The Christological debate could no longer be contained within the Alexandrian

The Christological debate could no longer be contained within the Alexandrian  According to some accounts in the hagiography of

According to some accounts in the hagiography of

Things went differently in the

Things went differently in the

The part of Arius's Thalia quoted in Athanasius's ''De Synodis'' is the longest extant fragment. The most commonly cited edition of ''De Synodis'' is by Hans-Georg Opitz. A translation of this fragment has been made by Aaron J. West, but based not on Opitz' text but on a previous edition: "When compared to Opitz' more recent edition of the text, we found that our text varies only in punctuation, capitalization, and one variant reading (χρόνῳ for χρόνοις, line 5)." Here is the Opitz edition with the West translation:

A slightly different edition of the fragment of the Thalia from ''De Synodis'' is given by G.C. Stead, and served as the basis for a translation by R.P.C. Hanson. Stead argued that the Thalia was written in anapestic meter, and edited the fragment to show what it would look like in anapests with different line breaks. Hanson based his translation of this fragment directly on Stead's text. Here is Stead's edition with Hanson's translation.

The part of Arius's Thalia quoted in Athanasius's ''De Synodis'' is the longest extant fragment. The most commonly cited edition of ''De Synodis'' is by Hans-Georg Opitz. A translation of this fragment has been made by Aaron J. West, but based not on Opitz' text but on a previous edition: "When compared to Opitz' more recent edition of the text, we found that our text varies only in punctuation, capitalization, and one variant reading (χρόνῳ for χρόνοις, line 5)." Here is the Opitz edition with the West translation:

A slightly different edition of the fragment of the Thalia from ''De Synodis'' is given by G.C. Stead, and served as the basis for a translation by R.P.C. Hanson. Stead argued that the Thalia was written in anapestic meter, and edited the fragment to show what it would look like in anapests with different line breaks. Hanson based his translation of this fragment directly on Stead's text. Here is Stead's edition with Hanson's translation.

Part I

Accessed 13 December 2009. * * Sozomen, Hermias. Edward Walford, Translator

Merchantville, NJ: Evolution Publishing, 2018. Online a

* Parvis, Sara. ''Marcellus of Ancyra And the Lost Years of the Arian Controversy 325–345''. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. * Rusch, William C. ''The Trinitarian Controversy''. Sources of Early Christian Thought, 1980. * Philip Schaff, Schaff, Philip. "Theological Controversies and the Development of Orthodoxy". In ''History of the Christian Church'', Vol III, Ch. IX. Online a

CCEL

Accessed 13 December 2009. * Wace, Henry. ''A Dictionary of Christian Biography and Literature to the End of the Sixth Century A.D., with an Account of the Principal Sects a.d Heresies''. Online a

CCEL

Accessed 13 December 2009.

The Complete Extant Works of Arius

From the

opposition

Opposition may refer to:

Arts and media

* ''Opposition'' (Altars EP), 2011 EP by Christian metalcore band Altars

* The Opposition (band), a London post-punk band

* '' The Opposition with Jordan Klepper'', a late-night television series on Com ...

to what would become the dominant Christology

In Christianity, Christology (from the Greek grc, Χριστός, Khristós, label=none and grc, -λογία, -logia, label=none), translated literally from Greek as "the study of Christ", is a branch of theology that concerns Jesus. Differ ...

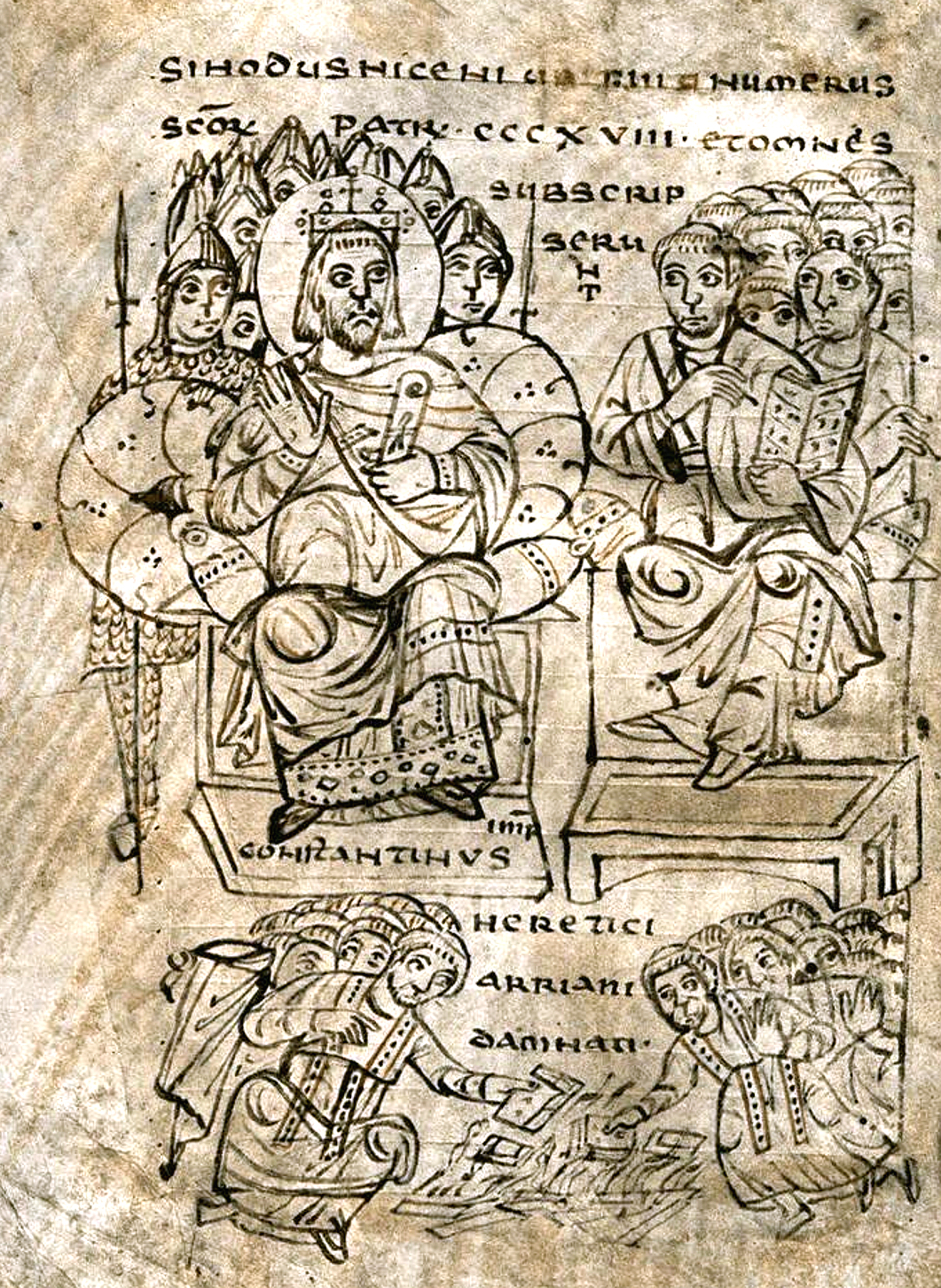

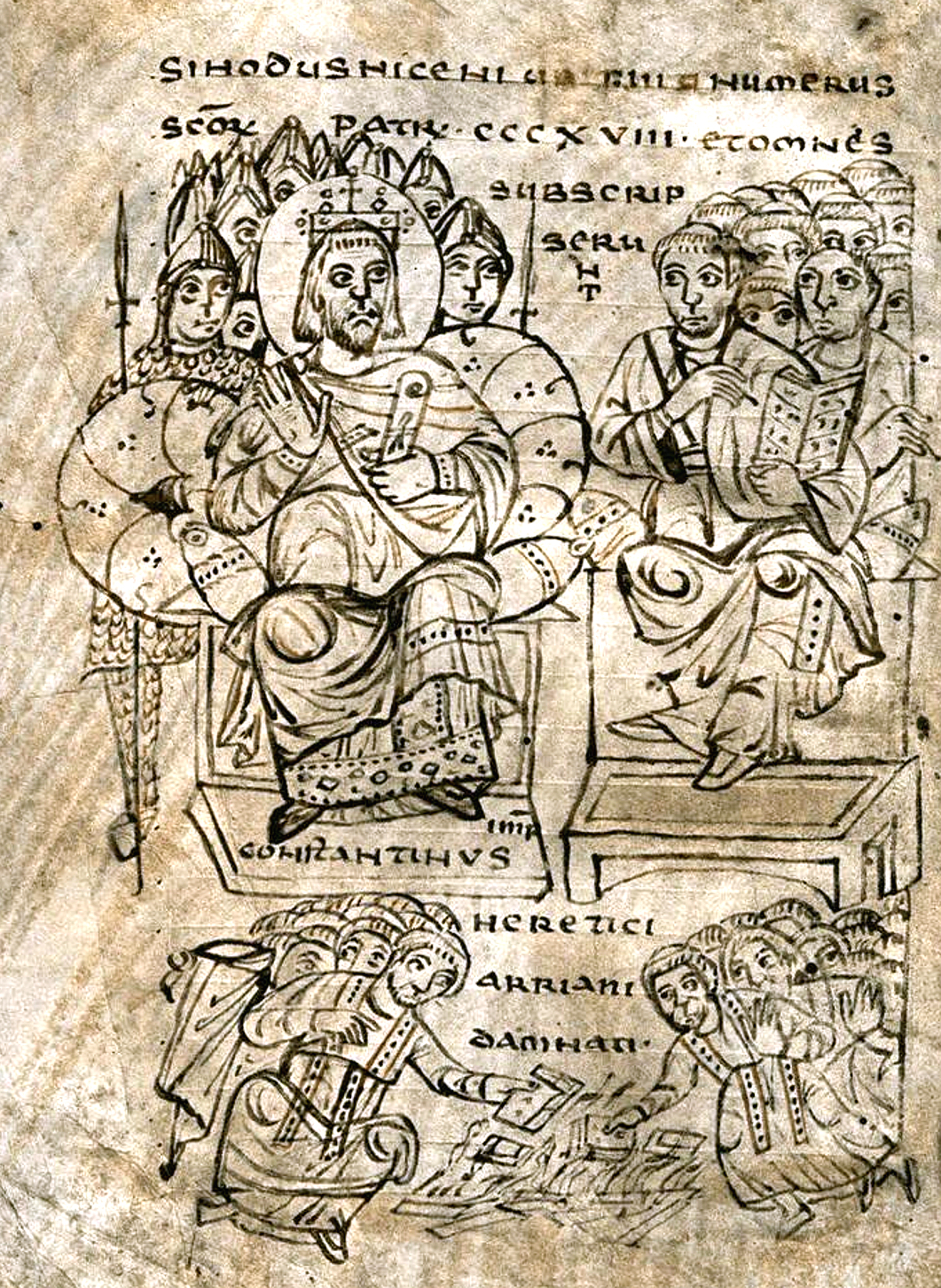

, Homoousian Christology, made him a primary topic of the First Council of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea (; grc, Νίκαια ) was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea (now İznik, Turkey) by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in AD 325.

This ecumenical council was the first effort ...

convened by Emperor Constantine the Great

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterran ...

in 325.

After Emperors Licinius

Valerius Licinianus Licinius (c. 265 – 325) was Roman emperor from 308 to 324. For most of his reign he was the colleague and rival of Constantine I, with whom he co-authored the Edict of Milan, AD 313, that granted official toleration to C ...

and Constantine legalized and formalized the Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

of the time in the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

, Constantine sought to unify the newly recognized Church and remove theological divisions. The Christian Church was divided over disagreements on Christology

In Christianity, Christology (from the Greek grc, Χριστός, Khristós, label=none and grc, -λογία, -logia, label=none), translated literally from Greek as "the study of Christ", is a branch of theology that concerns Jesus. Differ ...

, or the nature of the relationship between the first and second persons of the Trinity. Homoousian Christians, including Athanasius of Alexandria, used Arius and Arianism as epithets to describe those who disagreed with their doctrine of coequal Trinitarianism

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the ...

, a Homoousian Christology

In Christianity, Christology (from the Greek grc, Χριστός, Khristós, label=none and grc, -λογία, -logia, label=none), translated literally from Greek as "the study of Christ", is a branch of theology that concerns Jesus. Differ ...

representing God the Father and Jesus Christ the Son as "of one essence" ("consubstantial") and coeternal

Eternity, in common parlance, means infinite time that never ends or the quality, condition, or fact of being everlasting or eternal. Classical philosophy, however, defines eternity as what is timeless or exists outside time, whereas sempiter ...

.

Negative writings describe Arius's theology as one imputing there was a time before the Son of God existed—that is, when only God the Father existed. Despite concerted opposition, Arian Christian churches persisted for centuries throughout Europe (especially in various Germanic kingdoms), the Middle East, and North Africa. They were suppressed by military conquest or by voluntary royal conversion between the fifth and seventh centuries.

The Son's precise relationship with the Father had been discussed for decades before Arius's advent; Arius intensified the controversy and carried it to a Church-wide audience, where others like Eusebius of Nicomedia proved much more influential in the long run. In fact, some later Arians disavowed the name, claiming not to have been familiar with the man or his specific teachings. However, because the conflict between Arius and his foes brought the issue to the theological forefront, the doctrine they said he proclaimed—though he had definitely not originated—is generally labeled as "his".

Early life and personality

Reconstructing the life and doctrine of Arius has proven to be a difficult task, as none of his original writings survive. Emperor Constantine ordered their burning while Arius was still living, and any that survived this purge were later destroyed by his orthodox opponents. Those works which have survived are quoted in the works of churchmen who denounced him as a heretic. This leads some — but not all — scholars to question their reliability. His father's name is given as Ammonius. Arius is believed to have been a student at the exegetical school inAntioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

, where he studied under Saint Lucian. Having returned to Alexandria, Arius, according to a single source, sided with Meletius of Lycopolis

Melitius or Meletius (died 327) was bishop of Lycopolis in Egypt. He is known mainly as the founder and namesake of the Melitians (c. 305), one of several schismatic sects in early church history which were concerned about the ease with which la ...

in his dispute over the re-admission of those who had denied Christianity under fear of Roman torture, and was ordained a deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Chur ...

under the latter's auspices. He was excommunicated

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

by Bishop Peter of Alexandria in 311 for supporting Meletius, but under Peter's successor Achillas

Achillas ( el, Ἀχιλλᾶς) was one of the guardians of the Egyptian king Ptolemy XIII Theos Philopator, and commander of the king's troops, when Pompey fled to Egypt in 48 BC. He was called by Julius Caesar a man of extraordinary daring, a ...

, Arius was re-admitted to Christian communion and in 313 made presbyter

Presbyter () is an honorific title for Christian clergy. The word derives from the Greek ''presbyteros,'' which means elder or senior, although many in the Christian antiquity would understand ''presbyteros'' to refer to the bishop functioning a ...

of the Baucalis district in Alexandria.

Although his character has been severely assailed by his opponents, Arius appears to have been a man of personal ascetic achievement, pure morals, and decided convictions. Paraphrasing Epiphanius of Salamis

Epiphanius of Salamis ( grc-gre, Ἐπιφάνιος; c. 310–320 – 403) was the bishop of Salamis, Cyprus, at the end of the 4th century. He is considered a saint and a Church Father by both the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic Churches. He g ...

, an opponent of Arius, Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

historian Warren H. Carroll

Warren H. Carroll (March 24, 1932 – July 17, 2011) was the founder and first president of Christendom College in Front Royal, Virginia. He authored multiple works of Roman Catholic church history.

Biography

The son of Herbert Allen Carroll a ...

describes him as ''"tall and lean, of distinguished appearance and polished address. Women doted on him, charmed by his beautiful manners, touched by his appearance of asceticism. Men were impressed by his aura of intellectual superiority."''

Though Arius was also accused by his opponents of being too liberal and too loose in his theology, engaging in heresy (as defined by his opponents), some historians argue that Arius was actually quite conservative, and that he deplored how, in his view, Christian theology was being too freely mixed with Greek paganism

Religious practices in ancient Greece encompassed a collection of beliefs, rituals, and mythology, in the form of both popular public religion and cult practices. The application of the modern concept of "religion" to ancient cultures has been ...

.

The Arian controversy

Beginnings

TheTrinitarian

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the Fa ...

historian Socrates of Constantinople

Socrates of Constantinople ( 380 – after 439), also known as Socrates Scholasticus ( grc-gre, Σωκράτης ὁ Σχολαστικός), was a 5th-century Greek Christian church historian, a contemporary of Sozomen and Theodoret.

He is the ...

reports that Arius sparked the controversy that bears his name when Alexander of Alexandria, who had succeeded Achillas

Achillas ( el, Ἀχιλλᾶς) was one of the guardians of the Egyptian king Ptolemy XIII Theos Philopator, and commander of the king's troops, when Pompey fled to Egypt in 48 BC. He was called by Julius Caesar a man of extraordinary daring, a ...

as the Bishop of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

, gave a sermon stating the similarity of the Son to the Father. Arius interpreted Alexander's speech as being a revival of Sabellianism

In Christianity, Sabellianism is the Western Church equivalent to Patripassianism in the Eastern Church, which are both forms of theological modalism. Condemned as heresy, Modalism is the belief that the Father, Son and Holy Spirit are three diff ...

, condemned it, and then argued that ''"if the Father begat the Son, he that was begotten had a beginning of existence: and from this it is evident, that there was a time when the Son was not. It therefore necessarily follows, that he'' he Son

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

''had his substance from nothing."'' This quote describes the essence of Arius's doctrine.

Socrates of Constantinople believed that Arius was influenced in his thinking by the teachings of Lucian of Antioch

Lucian of Antioch (c. 240 – January 7, 312), known as Lucian the Martyr, was a Christian presbyter, theologian and martyr. He was noted for both his scholarship and ascetic piety.

History

According to Suidas, Lucian was born at Samosata, Kom ...

, a celebrated Christian teacher and martyr. In a letter to Patriarch Alexander of Constantinople

Alexander of Constantinople ( grc-gre, Ἀλέξανδρος; c. 237/240 – c. 340) was a bishop of Byzantium and the first Archbishop of Constantinople (the city was renamed during his episcopacy). Scholars consider most of the available inform ...

Arius's bishop, Alexander of Alexandria, wrote that Arius derived his theology from Lucian. The express purpose of Alexander's letter was to complain of the doctrines that Arius was spreading, but his charge of heresy against Arius is vague and unsupported by other authorities. Furthermore, Alexander's language, like that of most controversialists in those days, is quite bitter and abusive. Moreover, even Alexander never accused Lucian of having taught Arianism; rather, he accused Lucian ''ad invidiam'' of heretical tendencies—which apparently, according to him, were transferred to his pupil, Arius. The noted Russian historian Alexander Vasiliev refers to Lucian as "the Arius before Arius".

Origen and Arius

Like many third-century Christian scholars, Arius was influenced by the writings ofOrigen

Origen of Alexandria, ''Ōrigénēs''; Origen's Greek name ''Ōrigénēs'' () probably means "child of Horus" (from , "Horus", and , "born"). ( 185 – 253), also known as Origen Adamantius, was an early Christian scholar, ascetic, and theo ...

, widely regarded as the first great theologian of Christianity. However, while both agreed on the subordination of the Son to the Father, and Arius drew support from Origen's theories on the ''Logos

''Logos'' (, ; grc, λόγος, lógos, lit=word, discourse, or reason) is a term used in Western philosophy, psychology and rhetoric and refers to the appeal to reason that relies on logic or reason, inductive and deductive reasoning. Ari ...

'', the two did not agree on everything. Arius clearly argued that the ''Logos'' had a beginning and that the Son, therefore, was not eternal, the Logos being the highest of the Created Order. This idea is summarized in the statement "there was a time when the Son was not." By way of contrast, Origen believed the relation of the Son to the Father had no beginning, and that the Son was "eternally generated".

Arius objected to Origen's doctrine, complaining about it in his letter to the Nicomedian Eusebius, who had also studied under Lucian. Nevertheless, despite disagreeing with Origen on this point, Arius found solace in his writings, which used expressions that favored Arius's contention that the ''Logos'' was of a different substance than the Father, and owed his existence to his Father's will. However, because Origen's theological speculations were often proffered to stimulate further inquiry rather than to put an end to any given dispute, both Arius and his opponents were able to invoke the authority of this revered (at the time) theologian during their debate.

Arius emphasized the supremacy and uniqueness of God the Father, meaning that the Father alone is infinite and eternal and almighty, and that therefore the Father's divinity must be greater than the Son's. Arius taught that the Son had a beginning, contrary to Origen, who taught that the Son was less than the Father only in power, but not in time. Arius maintained that the Son possessed neither the eternity nor the true divinity of the Father, but was rather made "God" only by the Father's permission and power, and that the Logos was rather the very first and the most perfect of God's productions, before ages.

Initial responses

The Bishop of Alexandria exiled the presbyter following a council of local priests. Arius's supporters vehemently protested. Numerous bishops and Christian leaders of the era supported his cause, among them Eusebius of Nicomedia.First Council of Nicaea

The Christological debate could no longer be contained within the Alexandrian

The Christological debate could no longer be contained within the Alexandrian diocese

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associa ...

. By the time Bishop Alexander finally acted against Arius, Arius's doctrine had spread far beyond his own see; it had become a topic of discussion—and disturbance—for the entire Church. The Church was now a powerful force in the Roman world, with Emperors Licinius

Valerius Licinianus Licinius (c. 265 – 325) was Roman emperor from 308 to 324. For most of his reign he was the colleague and rival of Constantine I, with whom he co-authored the Edict of Milan, AD 313, that granted official toleration to C ...

and Constantine I

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to Constantine the Great and Christianity, convert to Christiani ...

having legalized it in 313 through the Edict of Milan

The Edict of Milan ( la, Edictum Mediolanense; el, Διάταγμα τῶν Μεδιολάνων, ''Diatagma tōn Mediolanōn'') was the February 313 AD agreement to treat Christians benevolently within the Roman Empire. Frend, W. H. C. ( ...

. Emperor Constantine had taken a personal interest in several ecumenical issues, including the Donatist

Donatism was a Christian sect leading to a schism in the Church, in the region of the Church of Carthage, from the fourth to the sixth centuries. Donatists argued that Christian clergy must be faultless for their ministry to be effective and the ...

controversy in 316, and he wanted to bring an end to the Christological dispute. To this end, the emperor sent Hosius, bishop of Córdoba to investigate and, if possible, resolve the controversy. Hosius was armed with an open letter from the Emperor: ''"Wherefore let each one of you, showing consideration for the other, listen to the impartial exhortation of your fellow-servant."'' But as the debate continued to rage despite Hosius's efforts, Constantine in AD 325 took an unprecedented step: he called a council to be composed of church prelate

A prelate () is a high-ranking member of the Christian clergy who is an ordinary or who ranks in precedence with ordinaries. The word derives from the Latin , the past participle of , which means 'carry before', 'be set above or over' or 'pre ...

s from all parts of the empire to resolve this issue, possibly at Hosius's recommendation.

All secular dioceses of the empire sent one or more representatives to the council, save for Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the period in classical antiquity when large parts of the island of Great Britain were under occupation by the Roman Empire. The occupation lasted from AD 43 to AD 410. During that time, the territory conquered wa ...

; the majority of the bishops came from the East. Pope Sylvester I

Pope Sylvester I (also Silvester, 285 – 31 December 335) was the bishop of Rome from 31 January 314 until his death. He filled the see of Rome at an important era in the history of the Western Church, yet very little is known of him. The acco ...

, himself too aged to attend, sent two priests as his delegates. Arius himself attended the council, as did his bishop, Alexander. Also there were Eusebius of Caesarea, Eusebius of Nicomedia and the young deacon Athanasius

Athanasius I of Alexandria, ; cop, ⲡⲓⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ ⲁⲑⲁⲛⲁⲥⲓⲟⲩ ⲡⲓⲁⲡⲟⲥⲧⲟⲗⲓⲕⲟⲥ or Ⲡⲁⲡⲁ ⲁⲑⲁⲛⲁⲥⲓⲟⲩ ⲁ̅; (c. 296–298 – 2 May 373), also called Athanasius the Great, ...

, who would become the champion of the Trinitarian view ultimately adopted by the council and spend most of his life battling Arianism. Before the main conclave convened, Hosius initially met with Alexander and his supporters at Nicomedia

Nicomedia (; el, Νικομήδεια, ''Nikomedeia''; modern İzmit) was an ancient Greek city located in what is now Turkey. In 286, Nicomedia became the eastern and most senior capital city of the Roman Empire (chosen by the emperor Diocleti ...

. The council would be presided over by the emperor himself, who participated in and even led some of its discussions.

At this First Council of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea (; grc, Νίκαια ) was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea (now İznik, Turkey) by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in AD 325.

This ecumenical council was the first effort ...

twenty-two bishops, led by Eusebius of Nicomedia, came as supporters of Arius. But when some of Arius's writings were read aloud, they are reported to have been denounced as blasphemous by most participants. Those who upheld the notion that Christ was co-eternal and con-substantial with the Father were led by the bishop Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

. Athanasius was not allowed to sit in on the Council since he was only an arch-deacon. But Athanasius is seen as doing the legwork and concluded (as Bishop Alexander conveyed in the Athanasian Trinitarian defense and also according to the Nicene Creed adopted at this Council) that the Son was of the same essence (homoousios) with the Father (or one in essence with the Father), and was eternally generated from that essence of the Father. Those who instead insisted that the Son of God came after God the Father in time and substance, were led by Arius the presbyter. For about two months, the two sides argued and debated, with each appealing to Scripture to justify their respective positions. Arius argued for the supremacy of God the Father, and maintained that the Son of God was simply the oldest and most beloved Creature of God, made from nothing, because of being the direct offspring. Arius taught that the pre-existent Son was God's First Production (the very first thing that God actually ever ''did'' in His entire eternal existence up to that point), before all ages. Thus he insisted that only God the Father had no beginning, and that the Father alone was infinite and eternal. Arius maintained that the Son had a beginning. Thus, said Arius, only the Son was directly created and begotten of God; furthermore, there was a time that He had no existence. He was capable of His own free will, said Arius, and thus "were He in the truest sense a son, He must have come after the Father, therefore the time obviously was when He was not, and hence He was a finite being." Arius appealed to Scripture, quoting verses such as : "the Father is greater than I". And also : "the firstborn of all creation." Thus, Arius insisted that the Father's Divinity

Divinity or the divine are things that are either related to, devoted to, or proceeding from a deity.divine< ...

was greater than the Son's, and that the Son was under God the Father, and not co-equal or co-eternal with Him.

Nicholas of Myra

Saint Nicholas of Myra, ; la, Sanctus Nicolaus (traditionally 15 March 270 – 6 December 343), also known as Nicholas of Bari, was an early Christian bishop of Greek descent from the maritime city of Myra in Asia Minor (; modern-day Demre ...

, debate at the council became so heated that at one point, Nicholas struck Arius across the face. The majority of the bishops ultimately agreed upon a creed, known thereafter as the Nicene creed. It included the word ''homoousios'', meaning "consubstantial", or "one in essence", which was incompatible with Arius's beliefs. On June 19, 325, council and emperor issued a circular to the churches in and around Alexandria: Arius and two of his unyielding partisans (Theonas and Secundus) were deposed and exiled to Illyricum, while three other supporters—Theognis of Nicaea

Theognis of Nicaea ( grc-gre, Θέογνις) was a 4th-century Bishop of Nicaea, excommunicated after the First Council of Nicaea for not denouncing Arius and his nontrinitarianism strongly enough.

He is best known to history

History (de ...

, Eusebius of Nicomedia and Maris of Chalcedon—affixed their signatures solely out of deference to the emperor. The following is part of the ruling made by the emperor denouncing Arius's teachings with fervor.

Exile, return, and death

The Homoousian party's victory at Nicaea was short-lived, however. Despite Arius's exile and the alleged finality of the Council's decrees, the Arian controversy recommenced at once. When Bishop Alexander died in 327, Athanasius succeeded him, despite not meeting the age requirements for a hierarch. Still committed to pacifying the conflict between Arians and Trinitarians, Constantine gradually became more lenient toward those whom the Council of Nicaea had exiled. Though he never repudiated the council or its decrees, the emperor ultimately permitted Arius (who had taken refuge in Palestine) and many of his adherents to return to their homes, once Arius had reformulated his Christology to mute the ideas found most objectionable by his critics. Athanasius was exiled following his condemnation by theFirst Synod of Tyre

The First Synod of Tyre or the Council of Tyre (335 AD) was a gathering of bishops called together by Emperor Constantine I for the primary purpose of evaluating charges brought against Athanasius, the Patriarch of Alexandria.

Background

Athana ...

in 335 (though he was later recalled), and the Synod of Jerusalem the following year restored Arius to communion. The emperor directed Alexander of Constantinople to receive Arius, despite the bishop's objections; Bishop Alexander responded by earnestly praying that Arius might perish before this could happen.

Modern scholars consider that the subsequent death of Arius may have been the result of poisoning by his opponents. In contrast, some contemporaries of Arius asserted that the circumstances of his death were miraculous – consequence of Arius's heretical

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

views. The latter view was evident in the account of Arius's death by a bitter enemy, Socrates Scholasticus

Socrates of Constantinople ( 380 – after 439), also known as Socrates Scholasticus ( grc-gre, Σωκράτης ὁ Σχολαστικός), was a 5th-century Greek Christian church historian, a contemporary of Sozomen and Theodoret.

He is th ...

.

The death of Arius did not end the Arian controversy, and would not be settled for centuries, in some parts of the Christian world.

Arianism after Arius

Immediate aftermath

Historians report that Constantine, who had not been baptized for most of his lifetime, was baptized on his deathbed in 337 by the Arian bishop, Eusebius of Nicomedia.Constantius II

Constantius II (Latin: ''Flavius Julius Constantius''; grc-gre, Κωνστάντιος; 7 August 317 – 3 November 361) was Roman emperor from 337 to 361. His reign saw constant warfare on the borders against the Sasanian Empire and Germanic ...

, who succeeded Constantine, was also an Arian sympathizer. Under him, Arianism reached its high point at the Third Council of Sirmium The Councils of Sirmium were the five episcopal councils held in Sirmium in 347, 351, 357, 358 and finally in 375 or 378. The third—the most important of the councils—marked a temporary compromise between Arianism and the Western bishops of the ...

in 357. The Seventh Arian Confession (Second Sirmium Confession) held, regarding the doctrines ''homoousios'' (of one substance) and ''homoiousios'' (of similar substance), that both were non-biblical; and that the Father is greater than the Son.

But since many persons are disturbed by questions concerning what is called in Latin ''substantia'', but in Greek ''ousia'', that is, to make it understood more exactly, as to 'coessential', or what is called, 'like-in-essence', there ought to be no mention of any of these at all, nor exposition of them in the Church, for this reason and for this consideration, that in divine Scripture nothing is written about them, and that they are above men's knowledge and above men's understanding.(This confession was later dubbed the

Blasphemy of Sirmium

Blasphemy is a speech crimes, speech crime and religious crime usually defined as an utterance that shows contempt, disrespects or insults a deity, an object considered sacred or something considered inviolable. Some religions regard blasphemy ...

.)

Following the abortive effort by Julian the Apostate to restore paganism in the empire, the emperor Valens

Valens ( grc-gre, Ουάλης, Ouálēs; 328 – 9 August 378) was Roman emperor from 364 to 378. Following a largely unremarkable military career, he was named co-emperor by his elder brother Valentinian I, who gave him the eastern half of ...

— himself an Arian — renewed the persecution of Nicene bishops. However, Valens's successor Theodosius I

Theodosius I ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος ; 11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also called Theodosius the Great, was Roman emperor from 379 to 395. During his reign, he succeeded in a crucial war against the Goths, as well as in two ...

ended Arianism once and for all among the elites of the Eastern Empire through a combination of imperial decree, persecution, and the calling of the Second Ecumenical Council

The First Council of Constantinople ( la, Concilium Constantinopolitanum; grc-gre, Σύνοδος τῆς Κωνσταντινουπόλεως) was a council of Christian bishops convened in Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey) in AD 381 b ...

in 381, which condemned Arius anew while reaffirming and expanding the Nicene Creed. This generally ended the influence of Arianism among the non-Germanic peoples of the Roman Empire.

Arianism in the West

Things went differently in the

Things went differently in the Western Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period fr ...

. During the reign of Constantius II, the Arian Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

convert Ulfilas

Ulfilas (–383), also spelled Ulphilas and Orphila, all Latinisation of names, Latinized forms of the unattested Gothic language, Gothic form *𐍅𐌿𐌻𐍆𐌹𐌻𐌰 Wulfila, literally "Little Wolf", was a Goths, Goth of Cappadocian Ancie ...

was consecrated a bishop by Eusebius of Nicomedia and sent to missionize his people. His success ensured the survival of Arianism among the Goths and Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The Vandals migrated to the area betw ...

until the beginning of the eighth century, when their kingdoms succumbed to the adjacent Niceans or they accepted Nicean Christianity. Arians continued to exist in North Africa, Spain and portions of Italy until they were finally suppressed during the sixth and seventh centuries.

In the 12th century, the Benedictine

, image = Medalla San Benito.PNG

, caption = Design on the obverse side of the Saint Benedict Medal

, abbreviation = OSB

, formation =

, motto = (English: 'Pray and Work')

, foun ...

abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the male head of a monastery in various Western religious traditions, including Christianity. The office may also be given as an honorary title to a clergyman who is not the head of a monastery. The ...

Peter the Venerable described the Islamic prophet Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mo ...

as "the successor of Arius and the precursor to the Antichrist

In Christian eschatology, the Antichrist refers to people prophesied by the Bible to oppose Jesus Christ and substitute themselves in Christ's place before the Second Coming. The term Antichrist (including one plural form)1 John ; . 2 John . ...

". During the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and ...

, a Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

sect known as the Polish Brethren

The Polish Brethren (Polish: ''Bracia Polscy'') were members of the Minor Reformed Church of Poland, a Nontrinitarian Protestant church that existed in Poland from 1565 to 1658. By those on the outside, they were called " Arians" or " Socinians" ( ...

were often referred to as Arians due to their antitrinitarian doctrine.

Arianism today

There are several contemporary Christian and Post-Christian denominations today that echo Arian thinking. Members ofthe Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, informally known as the LDS Church or Mormon Church, is a nontrinitarian Christian church that considers itself to be the restoration of the original church founded by Jesus Christ. The ch ...

(LDS Church) are sometimes accused of being Arians by their detractors. However, the Christology

In Christianity, Christology (from the Greek grc, Χριστός, Khristós, label=none and grc, -λογία, -logia, label=none), translated literally from Greek as "the study of Christ", is a branch of theology that concerns Jesus. Differ ...

of the Latter-day Saints differs in several significant aspects from Arian theology.

The Jehovah's Witnesses teach that the son is a created being, and is not actually God.

Some Christians in the Unitarian Universalist

Unitarian or Unitarianism may refer to:

Christian and Christian-derived theologies

A Unitarian is a follower of, or a member of an organisation that follows, any of several theologies referred to as Unitarianism:

* Unitarianism (1565–present) ...

movement are influenced by Arian ideas. Contemporary Unitarian Universalist Christians often may be either Arian or Socian in their Christology, seeing Jesus as a distinctive moral figure but not equal or eternal with God the Father; or they may follow Origen

Origen of Alexandria, ''Ōrigénēs''; Origen's Greek name ''Ōrigénēs'' () probably means "child of Horus" (from , "Horus", and , "born"). ( 185 – 253), also known as Origen Adamantius, was an early Christian scholar, ascetic, and theo ...

's logic of Universal Salvation, and thus potentially affirm the Trinity, but assert that all are already saved.

Arius's doctrine

Introduction

In explaining his actions against Arius, Alexander of Alexandria wrote a letter to Alexander of Constantinople and Eusebius of Nicomedia (where the emperor was then residing), detailing the errors into which he believed Arius had fallen. According to Alexander, Arius taught: Alexander also refers to Arius's poetical ''Thalia'':The Logos

This question of the exact relationship between the Father and the Son (a part of the theological science ofChristology

In Christianity, Christology (from the Greek grc, Χριστός, Khristós, label=none and grc, -λογία, -logia, label=none), translated literally from Greek as "the study of Christ", is a branch of theology that concerns Jesus. Differ ...

) had been raised some fifty years before Arius, when Paul of Samosata

Paul of Samosata ( grc-gre, Παῦλος ὁ Σαμοσατεύς, lived from 200 to 275 AD) was Bishop of Antioch from 260 to 268 and the originator of the Paulianist heresy named after him. He was a believer in monarchianism, a nontrinitarian ...

was deposed in 269 for agreeing with those who used the word homoousios

Homoousion ( ; grc, ὁμοούσιον, lit=same in being, same in essence, from , , "same" and , , "being" or "essence") is a Christian theological term, most notably used in the Nicene Creed for describing Jesus ( God the Son) as "same in b ...

(Greek for same substance) to express the relation between the Father and the Son. This term was thought at that time to have a Sabellian tendency, though—as events showed—this was on account of its scope not having been satisfactorily defined. In the discussion which followed Paul's deposition, Dionysius, the Bishop of Alexandria, used much the same language as Arius did later, and correspondence survives in which Pope Dionysius

Pope Dionysius was the bishop of Rome from 22 July 259 to his death on 26 December 268. His task was to reorganize the Roman church, after the persecutions of Emperor Valerian I and the edict of toleration by his successor Gallienus. He also h ...

blames him for using such terminology. Dionysius responded with an explanation widely interpreted as vacillating. The Synod of Antioch, which condemned Paul of Samosata, had expressed its disapproval of the word ''homoousios'' in one sense, while Bishop Alexander undertook its defense in another. Although the controversy seemed to be leaning toward the opinions later championed by Arius, no firm decision had been made on the subject; in an atmosphere so intellectual as that of Alexandria, the debate seemed bound to resurface—and even intensify—at some point in the future.

Arius endorsed the following doctrines about The Son or The Word (''Logos

''Logos'' (, ; grc, λόγος, lógos, lit=word, discourse, or reason) is a term used in Western philosophy, psychology and rhetoric and refers to the appeal to reason that relies on logic or reason, inductive and deductive reasoning. Ari ...

'', referring to Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

; see the ):

# that the Word (''Logos

''Logos'' (, ; grc, λόγος, lógos, lit=word, discourse, or reason) is a term used in Western philosophy, psychology and rhetoric and refers to the appeal to reason that relies on logic or reason, inductive and deductive reasoning. Ari ...

'') and the Father were not of the same essence (''ousia'');

# that the Son was a created being (''ktisma'' or ''poiema''); and

# that the worlds were created through him, so he must have existed before them and before all time.

# However, there was a "once" rius did not use words meaning "time", such as ''chronos'' or ''aion''when He did not exist, before he was begotten of the Father.

Extant writings

Three surviving letters attributed to Arius are his letter to Alexander of Alexandria, his letter to Eusebius of Nicomedia, and his confession to Constantine. In addition, several letters addressed by others to Arius survive, together with brief quotations contained within the polemical works of his opponents. These quotations are often short and taken out of context, and it is difficult to tell how accurately they quote him or represent his true thinking.The Thalia

Arius's ''Thalia'' (literally, "Festivity", "banquet"), a popularized work combining prose and verse and summarizing his views on the Logos, survives in quoted fragmentary form. In the Thalia, Arius says that God's first thought was the creation of the Son, before all ages, thereforetime

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, ...

started with the creation of the ''Logos'' or Word in Heaven (lines 1-9, 30-32); explains how the Son could still be God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

, even if he did not exist eternally (lines 20-23); and endeavors to explain the ultimate incomprehensibility of the Father to the Son (lines 33-39). The two available references from this work are recorded by his opponent Athanasius: the first is a report of Arius's teaching in ''Orations Against the Arians'', 1:5-6. This paraphrase has negative comments interspersed throughout, so it is difficult to consider it as being completely reliable.

The second quotation is found in the document ''On the Councils of Arminum and Seleucia'', also known as ''De Synodis'', pg. 15. This second passage is entirely in irregular verse, and seems to be a direct quotation or a compilation of quotations; it may have been written by someone other than Athanasius, perhaps even a person sympathetic to Arius. This second quotation does not contain several statements usually attributed to Arius by his opponents, is in metrical form, and resembles other passages that have been attributed to Arius. It also contains some positive statements about the Son. But although these quotations seem reasonably accurate, their proper context is lost, thus their place in Arius's larger system of thought is impossible to reconstruct.

The part of Arius's Thalia quoted in Athanasius's ''De Synodis'' is the longest extant fragment. The most commonly cited edition of ''De Synodis'' is by Hans-Georg Opitz. A translation of this fragment has been made by Aaron J. West, but based not on Opitz' text but on a previous edition: "When compared to Opitz' more recent edition of the text, we found that our text varies only in punctuation, capitalization, and one variant reading (χρόνῳ for χρόνοις, line 5)." Here is the Opitz edition with the West translation:

A slightly different edition of the fragment of the Thalia from ''De Synodis'' is given by G.C. Stead, and served as the basis for a translation by R.P.C. Hanson. Stead argued that the Thalia was written in anapestic meter, and edited the fragment to show what it would look like in anapests with different line breaks. Hanson based his translation of this fragment directly on Stead's text. Here is Stead's edition with Hanson's translation.

The part of Arius's Thalia quoted in Athanasius's ''De Synodis'' is the longest extant fragment. The most commonly cited edition of ''De Synodis'' is by Hans-Georg Opitz. A translation of this fragment has been made by Aaron J. West, but based not on Opitz' text but on a previous edition: "When compared to Opitz' more recent edition of the text, we found that our text varies only in punctuation, capitalization, and one variant reading (χρόνῳ for χρόνοις, line 5)." Here is the Opitz edition with the West translation:

A slightly different edition of the fragment of the Thalia from ''De Synodis'' is given by G.C. Stead, and served as the basis for a translation by R.P.C. Hanson. Stead argued that the Thalia was written in anapestic meter, and edited the fragment to show what it would look like in anapests with different line breaks. Hanson based his translation of this fragment directly on Stead's text. Here is Stead's edition with Hanson's translation.

See also

*Anomoeanism

In 4th-century Christianity, the Anomoeans , and known also as Heterousians , Aetians , or Eunomians , were a sect that upheld an extreme form of Arianism, that Jesus Christ was not of the same nature (consubstantial) as God the Father nor was of ...

* Arian controversy

The Arian controversy was a series of Christian disputes about the nature of Christ that began with a dispute between Arius and Athanasius of Alexandria, two Christian theologians from Alexandria, Egypt. The most important of these controversies ...

* Arianism

* Semi-Arianism

Semi-Arianism was a position regarding the relationship between God the Father and the Son of God, adopted by some 4th-century Christians. Though the doctrine modified the teachings of Arianism, it still rejected the doctrine that Father, Son, ...

* Nontrinitarianism

Nontrinitarianism is a form of Christianity that rejects the mainstream Christian doctrine of the Trinity—the belief that God is three distinct hypostases or persons who are coeternal, coequal, and indivisibly united in one being, or essenc ...

* Oneness Pentecostalism

Oneness Pentecostalism (also known as Apostolic, Jesus' Name Pentecostalism, or the Jesus Only movement) is a nontrinitarian religious movement within the Protestant Christian family of churches known as Pentecostalism. It derives its distincti ...

* Unitarianism

Unitarianism (from Latin ''unitas'' "unity, oneness", from ''unus'' "one") is a nontrinitarian branch of Christian theology. Most other branches of Christianity and the major Churches accept the doctrine of the Trinity which states that there i ...

* First Council of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea (; grc, Νίκαια ) was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea (now İznik, Turkey) by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in AD 325.

This ecumenical council was the first effort ...

References

Works cited

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *General references

Primary sources

* * Athanasius of Alexandria. ''History of the Arians''. Online at CCELPart I

Accessed 13 December 2009. * * Sozomen, Hermias. Edward Walford, Translator

Merchantville, NJ: Evolution Publishing, 2018. Online a

Secondary sources

* * Latinovic, Vladimir. ''Arius Conservativus? The Question of Arius' Theological Belonging'' in: Studia Patristica, XCV, p. 27-42. Peeters, 2017. Online a* Parvis, Sara. ''Marcellus of Ancyra And the Lost Years of the Arian Controversy 325–345''. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. * Rusch, William C. ''The Trinitarian Controversy''. Sources of Early Christian Thought, 1980. * Philip Schaff, Schaff, Philip. "Theological Controversies and the Development of Orthodoxy". In ''History of the Christian Church'', Vol III, Ch. IX. Online a

CCEL

Accessed 13 December 2009. * Wace, Henry. ''A Dictionary of Christian Biography and Literature to the End of the Sixth Century A.D., with an Account of the Principal Sects a.d Heresies''. Online a

CCEL

Accessed 13 December 2009.

External links

*The Complete Extant Works of Arius

From the

Wisconsin Lutheran College

Wisconsin Lutheran College (WLC) is a private liberal arts college affiliated with the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod and located on the border of Milwaukee and Wauwatosa, Wisconsin. It has an enrollment of about 1,200 students and is accre ...

website page entitled "Fourth Century Christianity".

*

*

{{Authority control

256 births

336 deaths

3rd-century Arian Christians

3rd-century Christian theologians

3rd-century Romans

3rd-century writers

4th-century Arian Christians

4th-century Christian theologians

4th-century Romans

4th-century writers

Antitrinitarians

Deaths onstage

Egyptian Christian clergy

Founders of religions

Libyan Christians

People declared heretics by the first seven ecumenical councils

People excommunicated by the Catholic Church

Roman-era philosophers in Alexandria

Nature of Jesus Christ