Archibald Macleish on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

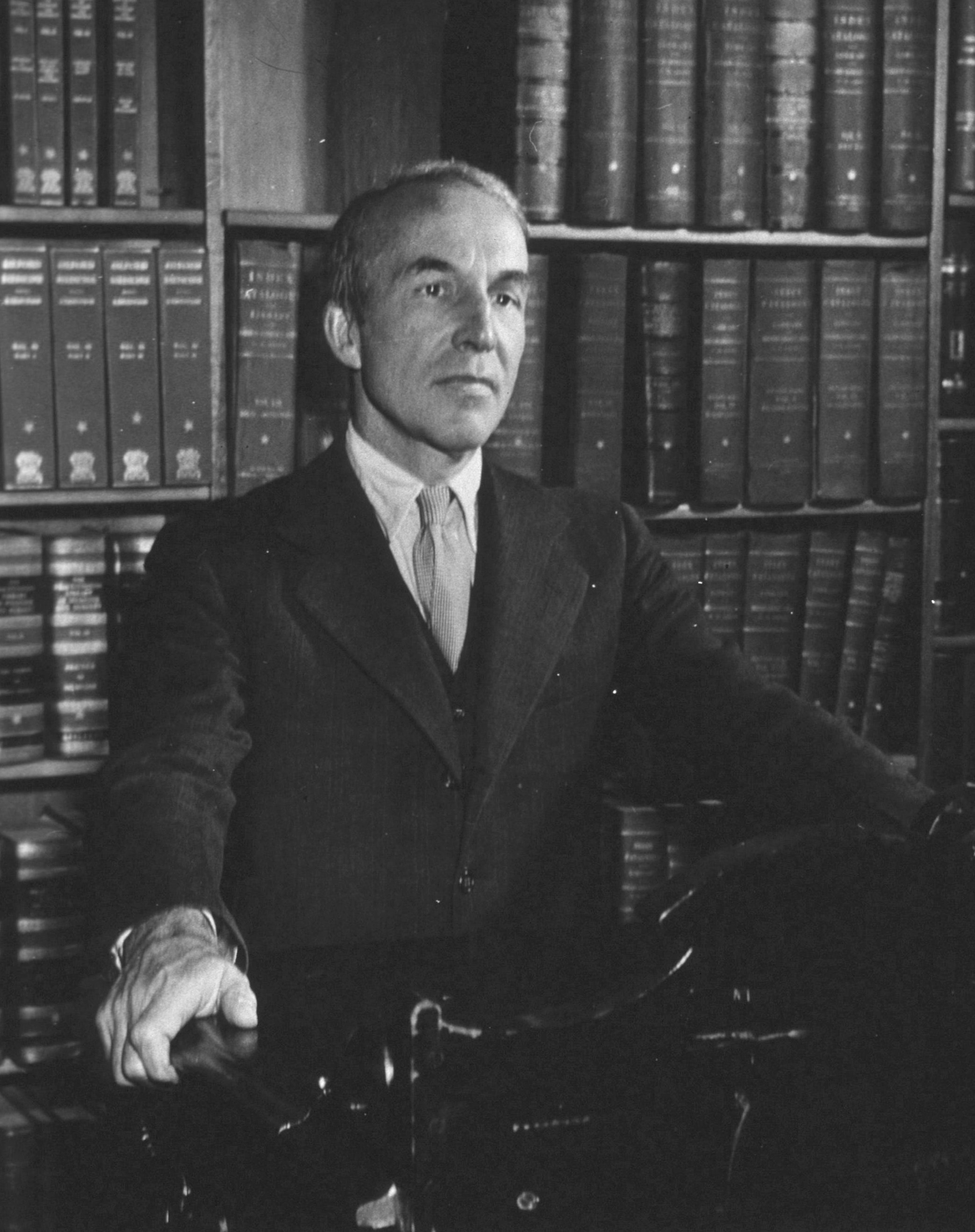

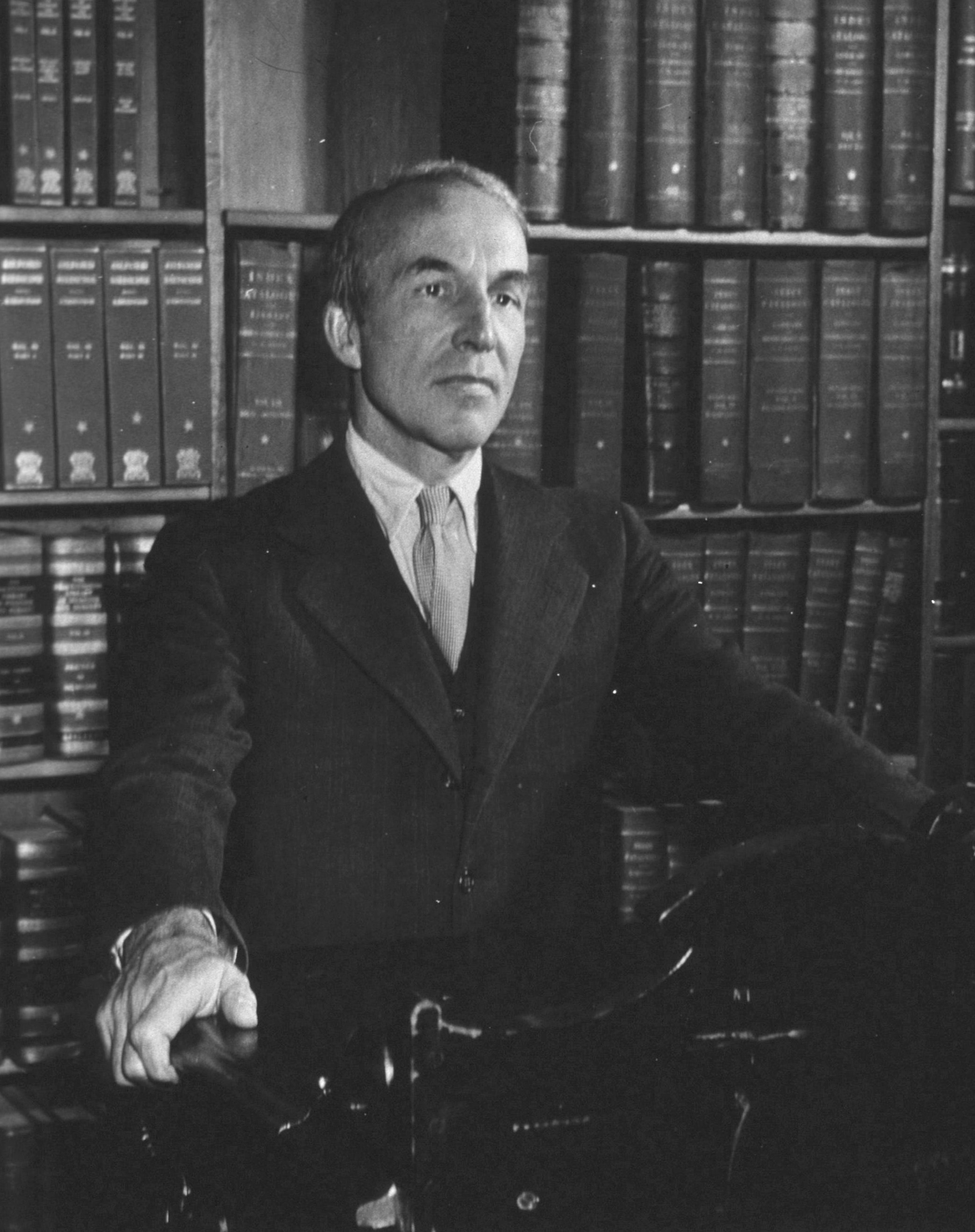

Archibald MacLeish (May 7, 1892 – April 20, 1982) was an American poet and writer, who was associated with the modernist school of poetry. MacLeish studied English at

A question from MacLeish's daughter, Mimi, led him to realize, "Nothing is more difficult for the beginning librarian than to discover nwhat profession he was engaged." Mimi, his daughter, had inquired about what her daddy was to do all day, "...hand out books?" MacLeish created his own job description and set out to learn about how the library was currently organized. In October 1944, MacLeish described that he did not set out to reorganize the library, rather "...one problem or another demanded action, and each problem solved led on to another that needed attention."

MacLeish's chief accomplishments had their start in instituting daily staff meetings with division chiefs, the chief assistant librarian, and other administrators. He then set about setting up various committees on various projects, including acquisitions policy, fiscal operations, cataloging, and outreach. The committees alerted MacLeish to various problems throughout the library. Putnam was conspicuously not invited to attend these meetings, resulting in the librarian emeritus' feelings being "mortally hurt", but according to MacLeish, it was necessary to exclude Putnam; otherwise, "he would have been sitting there listening to talk about himself which he would take personally."

First and foremost, under Putnam, the library was acquiring more books than it could catalog. A report in December 1939, found that over one-quarter of the library's collection had not yet been cataloged. MacLeish solved the problem of acquisitions and cataloging through establishing another committee instructed to seek advice from specialists outside of the Library of Congress. The committee found many subject areas of the library to be adequate and many other areas to be, surprisingly, inadequately provided for. A set of general principles on acquisitions was then developed to ensure that, though it was impossible to collect everything, the Library of Congress would acquire the bare minimum of canons to meet its mission. These principles included acquiring all materials necessary to members of Congress and government officers, all materials expressing and recording the life and achievements of the people of the United States, and materials of other societies past and present that are of the most immediate concern to the peoples of the United States.

Secondly, MacLeish set about reorganizing the operational structure. Leading scholars in

A question from MacLeish's daughter, Mimi, led him to realize, "Nothing is more difficult for the beginning librarian than to discover nwhat profession he was engaged." Mimi, his daughter, had inquired about what her daddy was to do all day, "...hand out books?" MacLeish created his own job description and set out to learn about how the library was currently organized. In October 1944, MacLeish described that he did not set out to reorganize the library, rather "...one problem or another demanded action, and each problem solved led on to another that needed attention."

MacLeish's chief accomplishments had their start in instituting daily staff meetings with division chiefs, the chief assistant librarian, and other administrators. He then set about setting up various committees on various projects, including acquisitions policy, fiscal operations, cataloging, and outreach. The committees alerted MacLeish to various problems throughout the library. Putnam was conspicuously not invited to attend these meetings, resulting in the librarian emeritus' feelings being "mortally hurt", but according to MacLeish, it was necessary to exclude Putnam; otherwise, "he would have been sitting there listening to talk about himself which he would take personally."

First and foremost, under Putnam, the library was acquiring more books than it could catalog. A report in December 1939, found that over one-quarter of the library's collection had not yet been cataloged. MacLeish solved the problem of acquisitions and cataloging through establishing another committee instructed to seek advice from specialists outside of the Library of Congress. The committee found many subject areas of the library to be adequate and many other areas to be, surprisingly, inadequately provided for. A set of general principles on acquisitions was then developed to ensure that, though it was impossible to collect everything, the Library of Congress would acquire the bare minimum of canons to meet its mission. These principles included acquiring all materials necessary to members of Congress and government officers, all materials expressing and recording the life and achievements of the people of the United States, and materials of other societies past and present that are of the most immediate concern to the peoples of the United States.

Secondly, MacLeish set about reorganizing the operational structure. Leading scholars in

Archibald MacLeish also assisted with the development of the new " Research and Analysis Branch" of the

Archibald MacLeish also assisted with the development of the new " Research and Analysis Branch" of the

Bob Dylan’s First Musical Had a Devil of a Time

''The New York Times'', November 3, 2020, ''accessed November 5, 2020.'' MacLeish greatly admired T. S. Eliot and

National Book Foundation. Retrieved 2012-03-02.

(With acceptance speech by MacLeish and essay by John Murillo from the Awards 60-year anniversary blog.) *1953: Bollingen Prize in Poetry *1959: Pulitzer Prize for Drama ('' J.B.'') *1959: Tony Award for Best Play (''J.B.'') *1976: elected to the

"Verse Play for Radio by Archibald MacLeish"

''The Hartford Courant Magazine''. December 18, 1938. p. 7. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

*''Colloquy for the States'' (1943)

*'' The American Story: Ten Broadcasts'' (1944)

*''The Trojan Horse'' (1952)

*''This Music Crept By Me on the Waters'' (1953)

*'' J.B.'' (1958)

*''Three Short Plays: The Secret of Freedom. Air Raid. The Fall of the City.'' (1961)

*''An Evening's Journey to Conway'' (1967)

*''Herakles'' (1967)

*''Scratch'' (1971)

*''Magic Prison: the Poetry of Emily Dickinson'' (1975)

*''The Great American Fourth of July Parade'' (1975)

*''Six Plays'' (1980)

addition

at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Archibald MacLeish Collection

at the Harry Ransom Center

Archibald MacLeish Papers

at

Archibald MacLeish's Grave

*

The Fall of the City

Columbia Workshop, CBS radio, 1937

"Archibald MacLeish"

''Academy of American Poets'' * {{DEFAULTSORT:Macleish, Archibald 1892 births 1982 deaths 20th-century American dramatists and playwrights 20th-century American poets American librarians American people of Scottish descent Amherst College faculty Bollingen Prize recipients Dern family Fortune (magazine) people Harvard Law School alumni Hotchkiss School alumni Librarians of Congress Lost Generation writers Members of Skull and Bones Members of the American Philosophical Society Military personnel from Illinois National Book Award winners People from Glencoe, Illinois People of the United States Office of War Information Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients Presidents of the American Academy of Arts and Letters Psi Upsilon Pulitzer Prize for Drama winners Pulitzer Prize for Poetry winners Tony Award winners United States Army officers United States Army personnel of World War I United States assistant secretaries of state Writers from Illinois Yale University alumni

Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...

and law at Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

. He enlisted in and saw action during the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and lived in Paris in the 1920s. On returning to the United States, he contributed to Henry Luce's magazine '' Fortune'' from 1929 to 1938. For five years, MacLeish was the ninth Librarian of Congress, a post he accepted at the urging of President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

. From 1949 to 1962, he was Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory at Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher lear ...

. He was awarded three Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prizes () are 23 annual awards given by Columbia University in New York City for achievements in the United States in "journalism, arts and letters". They were established in 1917 by the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made his fo ...

s for his work.

Early years

MacLeish was born on May 7, 1892, in Glencoe, Illinois. His father, Scottish-born Andrew MacLeish, worked as a dry-goods merchant and was a founder of the Chicago department store Carson Pirie Scott. His mother, Martha (née Hillard), was a college professor and had served as president of Rockford College. He grew up on an estate borderingLake Michigan

Lake Michigan ( ) is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is the second-largest of the Great Lakes by volume () and depth () after Lake Superior and the third-largest by surface area (), after Lake Superior and Lake Huron. To the ...

. He attended the Hotchkiss School from 1907 to 1911. For his college education, MacLeish went to Yale University, where he majored in English, was elected to Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States. It was founded in 1776 at the College of William & Mary in Virginia. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal arts and sciences, ...

, and was selected for the Skull and Bones society. He then enrolled in Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a Private university, private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, Harvard Law School is the oldest law school in continuous operation in the United ...

, where he served as an editor of the ''Harvard Law Review

The ''Harvard Law Review'' is a law review published by an independent student group at Harvard Law School. According to the ''Journal Citation Reports'', the ''Harvard Law Review''s 2015 impact factor of 4.979 placed the journal first out of ...

''.

His studies were interrupted by World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, in which he served first as an ambulance driver and later as an artillery officer. He fought at the Second Battle of the Marne. His brother, Kenneth MacLeish, was killed in action during the war. He graduated from law school in 1919, taught law for a semester for the government department at Harvard, then worked briefly as an editor for ''The New Republic

''The New Republic'' (often abbreviated as ''TNR'') is an American magazine focused on domestic politics, news, culture, and the arts from a left-wing perspective. It publishes ten print magazines a year and a daily online platform. ''The New Y ...

''. He next spent three years practicing law with the Boston firm Choate, Hall & Stewart. MacLeish expressed his disillusion with war in his poem ''Memorial Rain'', published in 1926.

Years in Paris

In 1923, MacLeish left his law firm and moved with his wife to Paris, where they joined the community of literary expatriates that included such members as Gertrude Stein andErnest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway ( ; July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer and journalist. Known for an economical, understated style that influenced later 20th-century writers, he has been romanticized fo ...

. They also became part of the famed coterie of Riviera hosts Gerald and Sarah Murphy, which included Hemingway, Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald, John Dos Passos

John Roderigo Dos Passos (; January 14, 1896 – September 28, 1970) was an American novelist, most notable for his U.S.A. (trilogy), ''U.S.A.'' trilogy.

Born in Chicago, Dos Passos graduated from Harvard College in 1916. He traveled widely as a ...

, Fernand Léger, Jean Cocteau

Jean Maurice Eugène Clément Cocteau ( , ; ; 5 July 1889 11 October 1963) was a French poet, playwright, novelist, designer, film director, visual artist and critic. He was one of the foremost avant-garde artists of the 20th-c ...

, Pablo Picasso

Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz y Picasso (25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973) was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, Ceramic art, ceramicist, and Scenic ...

, John O'Hara, Cole Porter, Dorothy Parker, and Robert Benchley. He returned to America in 1928. From 1930 to 1938, he worked as a writer and editor for Henry Luce's ''Fortune'', during which he also became increasingly politically active, especially with antifascist causes. By the 1930s, he considered capitalism to be "symbolically dead" and wrote the verse play '' Panic'' (1935) in response.

While in Paris, Harry Crosby, publisher of the Black Sun Press, offered to publish MacLeish's poetry. Both MacLeish and Crosby had overturned the normal expectations of society, rejecting conventional careers in the legal and banking fields. Crosby published MacLeish's long poem "Einstein" in a deluxe edition of 150 copies that sold quickly. MacLeish was paid $200 for his work. In 1932, MacLeish published his long poem "Conquistador", which presents Cortés's conquest of the Aztecs as symbolic of the American experience. In 1933, "Conquistador" was awarded a Pulitzer Prize, the first of three awarded to MacLeish.

In 1934, he wrote a libretto for ', a ballet by Nicolas Nabokov and Léonide Massine ( Ballet Russe de Monte-Carlo); it premiered in Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

with great success.

In 1938, MacLeish published as a book a long poem "Land of the Free", built around a series of 88 photographs of the rural depression by Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, Arthur Rothstein

Arthur Rothstein (July 17, 1915 – November 11, 1985) was an American photographer. His career spanned five decades, and he received recognition as one of America's premier photojournalists.

Life and career

The son of Jewish immigrants, Rothste ...

, Ben Shahn, and the Farm Security Administration and other agencies. The book influenced Steinbeck's '' The Grapes of Wrath''.

Librarian of Congress

American Libraries has called MacLeish "one of the 100 most influential figures in librarianship during the 20th century" in the United States. MacLeish's career in libraries and public service began, not with an internal desire, but from a combination of the urging of a close friend, Felix Frankfurter, and as MacLeish put it, "The President decided I wanted to be Librarian of Congress."Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

's nomination of MacLeish was a controversial and highly political maneuver fraught with several challenges.

MacLeish sought support from expected places such as the president of Harvard, MacLeish's current place of work, but found none. Support from unexpected places, such as M. Llewellyn Raney of the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, or UChi) is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Its main campus is in the Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood on Chicago's South Side, Chic ...

libraries, alleviated the ALA letter-writing campaign against MacLeish's nomination." The main Republican argument against MacLeish's nomination from within Congress was that he was a poet and was a " fellow traveler" or sympathetic to communist causes. Calling to mind differences with the party he had over the years, MacLeish avowed, "no one would be more shocked to learn I am a Communist than the Communists themselves." In Congress, MacLeish's main advocate was Senate Majority Leader Alben Barkley

Alben William Barkley (; November 24, 1877 – April 30, 1956) was the 35th vice president of the United States serving from 1949 to 1953 under President Harry S. Truman. In 1905, he was elected to local offices and in 1912 as a U.S. rep ...

, Democrat from Kentucky. With President Roosevelt's support and Senator Barkley's skillful defense in the United States Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the United States House of Representatives, U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and ...

, victory in a roll call vote was achieved, with 63 senators voting in favor of MacLeish's appointment. MacLeish was sworn in as Librarian of Congress on July 10, 1939, by the local postmaster at Conway, Massachusetts.

MacLeish became privy to Roosevelt's views on the library during a private meeting with the President. According to Roosevelt, the pay levels were too low and many people would need to be removed. Soon afterward, MacLeish joined the retiring Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam for a luncheon in New York. At the meeting, Putnam relayed his intention to continue working at the library, that he would be given the title of librarian emeritus, and that his office would be down the hall from MacLeish's. The meeting further crystallized for MacLeish that as Librarian of Congress, he would be "an unpopular newcomer, disturbing the status quo."

A question from MacLeish's daughter, Mimi, led him to realize, "Nothing is more difficult for the beginning librarian than to discover nwhat profession he was engaged." Mimi, his daughter, had inquired about what her daddy was to do all day, "...hand out books?" MacLeish created his own job description and set out to learn about how the library was currently organized. In October 1944, MacLeish described that he did not set out to reorganize the library, rather "...one problem or another demanded action, and each problem solved led on to another that needed attention."

MacLeish's chief accomplishments had their start in instituting daily staff meetings with division chiefs, the chief assistant librarian, and other administrators. He then set about setting up various committees on various projects, including acquisitions policy, fiscal operations, cataloging, and outreach. The committees alerted MacLeish to various problems throughout the library. Putnam was conspicuously not invited to attend these meetings, resulting in the librarian emeritus' feelings being "mortally hurt", but according to MacLeish, it was necessary to exclude Putnam; otherwise, "he would have been sitting there listening to talk about himself which he would take personally."

First and foremost, under Putnam, the library was acquiring more books than it could catalog. A report in December 1939, found that over one-quarter of the library's collection had not yet been cataloged. MacLeish solved the problem of acquisitions and cataloging through establishing another committee instructed to seek advice from specialists outside of the Library of Congress. The committee found many subject areas of the library to be adequate and many other areas to be, surprisingly, inadequately provided for. A set of general principles on acquisitions was then developed to ensure that, though it was impossible to collect everything, the Library of Congress would acquire the bare minimum of canons to meet its mission. These principles included acquiring all materials necessary to members of Congress and government officers, all materials expressing and recording the life and achievements of the people of the United States, and materials of other societies past and present that are of the most immediate concern to the peoples of the United States.

Secondly, MacLeish set about reorganizing the operational structure. Leading scholars in

A question from MacLeish's daughter, Mimi, led him to realize, "Nothing is more difficult for the beginning librarian than to discover nwhat profession he was engaged." Mimi, his daughter, had inquired about what her daddy was to do all day, "...hand out books?" MacLeish created his own job description and set out to learn about how the library was currently organized. In October 1944, MacLeish described that he did not set out to reorganize the library, rather "...one problem or another demanded action, and each problem solved led on to another that needed attention."

MacLeish's chief accomplishments had their start in instituting daily staff meetings with division chiefs, the chief assistant librarian, and other administrators. He then set about setting up various committees on various projects, including acquisitions policy, fiscal operations, cataloging, and outreach. The committees alerted MacLeish to various problems throughout the library. Putnam was conspicuously not invited to attend these meetings, resulting in the librarian emeritus' feelings being "mortally hurt", but according to MacLeish, it was necessary to exclude Putnam; otherwise, "he would have been sitting there listening to talk about himself which he would take personally."

First and foremost, under Putnam, the library was acquiring more books than it could catalog. A report in December 1939, found that over one-quarter of the library's collection had not yet been cataloged. MacLeish solved the problem of acquisitions and cataloging through establishing another committee instructed to seek advice from specialists outside of the Library of Congress. The committee found many subject areas of the library to be adequate and many other areas to be, surprisingly, inadequately provided for. A set of general principles on acquisitions was then developed to ensure that, though it was impossible to collect everything, the Library of Congress would acquire the bare minimum of canons to meet its mission. These principles included acquiring all materials necessary to members of Congress and government officers, all materials expressing and recording the life and achievements of the people of the United States, and materials of other societies past and present that are of the most immediate concern to the peoples of the United States.

Secondly, MacLeish set about reorganizing the operational structure. Leading scholars in library science

Library and information science (LIS)Library and Information Sciences is the name used in the Dewey Decimal Classification for class 20 from the 18th edition (1971) to the 22nd edition (2003). are two interconnected disciplines that deal with info ...

were assigned a committee to analyze the library's managerial structure. The committee issued a report a mere two months after it was formed, in April 1940, stating that a major restructuring was necessary. This was no surprise to MacLeish, who had 35 divisions under him. He divided the library's functions into three departments: administration, processing, and reference. All existing divisions were then assigned as appropriate. By including library scientists from inside and outside the Library of Congress, MacLeish was able to gain faith from the library community that he was on the right track. Within a year, MacLeish had completely restructured the Library of Congress, making it work more efficiently and aligning the library to "report on the mystery of things."

Last, but not least, MacLeish promoted the Library of Congress through various forms of public advocacy. Perhaps his greatest display of public advocacy was requesting a budget increase of over a million dollars in his March 1940 budget proposal to Congress. While the library did not receive the full increase, it received an increase of $367,591, the largest one-year increase to date. Much of the increase went toward improved pay levels, increased acquisitions in underserved subject areas, and new positions. MacLeish resigned as Librarian of Congress on December 19, 1944, to take up the post of Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs.

World War II

Archibald MacLeish also assisted with the development of the new " Research and Analysis Branch" of the

Archibald MacLeish also assisted with the development of the new " Research and Analysis Branch" of the Office of Strategic Services

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the first intelligence agency of the United States, formed during World War II. The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines ...

, the precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA; ) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and ...

. "These operations were overseen by the distinguished Harvard University historian William L. Langer, who, with the assistance of the American Council of Learned Societies and Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish, set out immediately to recruit a professional staff drawn from across the social sciences. Over the next 12 months, academic specialists from fields ranging from geography

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

to classical philology descended upon Washington, bringing with them their most promising graduate students, and set up shop in the headquarters of the Research and Analysis (R&A) Branch at Twenty-third and E Streets, and in the new annex to the Library of Congress."

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, MacLeish also served as director of the War Department's Office of Facts and Figures, and as the assistant director of the Office of War Information. These jobs were heavily involved with propaganda, which was well-suited to MacLeish's talents; he had written quite a bit of politically motivated work in the previous decade. He spent a year as the Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs and a further year representing the U.S. at the creation of UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

, where he contributed to the preamble of its 1945 Constitution ("Since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of men that the defenses of peace must be constructed."). After this, he retired from public service and returned to academia

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of tertiary education. The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, founded approximately 386 BC at Akademia, a sanctuary of Athena, the go ...

.

Return to writing

Despite a long history of debate over the merits ofMarxism

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...

, MacLeish came under fire from anticommunists in the 1940s and 1950s, including J. Edgar Hoover and Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican Party (United States), Republican United States Senate, U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death at age ...

. Much of this was due to his involvement with left-wing organizations such as the League of American Writers, and to his friendships with prominent left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy either as a whole or of certain social ...

writers. ''Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

'' magazine's Whittaker Chambers cited him as a fellow traveler in a 1941 article: "By 1938, U. S. Communists could count among their allies such names as Granville Hicks, Newton Arvin, Waldo Frank, Lewis Mumford, Matthew Josephson, Kyle Crichton (Robert Forsythe), Malcolm Cowley, Donald Ogden Stewart, Erskine Caldwell, Dorothy Parker, Archibald MacLeish, Lillian Hellman

Lillian Florence Hellman (June 20, 1905 – June 30, 1984) was an American playwright, Prose, prose writer, Memoir, memoirist, and screenwriter known for her success on Broadway as well as her communist views and political activism. She was black ...

, Dashiell Hammett, John Steinbeck, George Soule, many another."

In 1949, MacLeish became the Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory at Harvard University. He held this position until his retirement in 1962. In 1959, his play '' J.B.'' won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. From 1963 to 1967, he was the John Woodruff Simpson Lecturer at Amherst College

Amherst College ( ) is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Amherst, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1821 as an attempt to relocate Williams College by its then-president Zepha ...

. In 1969, MacLeish met Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan (legally Robert Dylan; born Robert Allen Zimmerman, May 24, 1941) is an American singer-songwriter. Described as one of the greatest songwriters of all time, Dylan has been a major figure in popular culture over his nearly 70-year ...

, and asked him to contribute songs to ''Scratch'', a musical MacLeish was writing, based on the story " The Devil and Daniel Webster" by Stephen Vincent Benét. The collaboration was a failure and ''Scratch'' opened without any music; Dylan describes their collaboration in the third chapter of his autobiography '' Chronicles, Vol. 1''.Adam LangerBob Dylan’s First Musical Had a Devil of a Time

''The New York Times'', November 3, 2020, ''accessed November 5, 2020.'' MacLeish greatly admired T. S. Eliot and

Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an List of poets from the United States, American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Ita ...

, and his work shows quite a bit of their influence. He was the literary figure who played the most important role in Ezra Pound’s release from St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, D.C., where he was held between 1946 and 1958, after being found unfit to stand trial for high treason. MacLeish's early work was very traditionally modernist and accepted the contemporary modernist position holding that a poet was isolated from society. His most well-known poem, " Ars Poetica," contains a classic statement of the modernist aesthetic: "A poem should not mean / But be." He later broke with modernism's pure aesthetic. MacLeish himself was greatly involved in public life and came to believe that this was not only an appropriate, but also an inevitable role for a poet.

In 1969, MacLeish was commissioned by ''The New York Times'' to write a poem to celebrate the Apollo 11 Moon landing, which he entitled "Voyage to the Moon." The poem appeared on the front page of the July 21, 1969 edition of ''Time'' magazine. A. M. Rosenthal, then-editor of ''Time'', later recounted: "We decided what the front page of ''Time'' would need when the men landed was a poem. What the poet wrote would count most, but we also wanted to say to our readers, look, this paper does not know how to express how it feels this day and perhaps you don't either, so here is a fellow, a poet, who will try for all of us. We called one poet who just did not think much of moons or us, and then decided to reach higher for somebody with more zest in his soul – for Archibald MacLeish, winner of three Pulitzer Prizes. He turned in his poem on time and entitled it 'Voyage to the Moon.'"

Legacy

MacLeish worked to promote the arts, culture, and libraries. Among other impacts, MacLeish was the first Librarian of Congress to begin the process of naming what would become the United States Poet Laureate. The Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress came from a donation in 1937 from Archer M. Huntington, a wealthy ship builder. Like many donations, it came with strings attached. In this case, Huntington wanted poet Joseph Auslander to be named to the position. MacLeish found little value in Auslander's writing. However, MacLeish was happy that having Auslander in the post attracted many other poets, such as Robinson Jeffers and Robert Frost, to hold readings at the library. He set about establishing the consultantship as a revolving post rather than a lifetime position. In 1943, MacLeish displayed his love of poetry and the Library of Congress by naming Louise Bogan to the position. Bogan, who had long been a hostile critic of MacLeish's own writing, asked MacLeish why he appointed her to the position; MacLeish replied that she was the best person for the job. For MacLeish, promoting the Library of Congress and the arts was vitally more important than petty personal conflicts. In the June 5, 1972, issue of '' The American Scholar'', MacLeish laid out in an essay his philosophy on libraries and librarianship, further shaping modern thought on the subject: Two collections of MacLeish's papers are held at theYale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. These are the Archibald MacLeish Collection and the Archibald MacLeish Collection Addition. Additionally, more than 13,500 items from his papers and his personal library are held in the Archibald MacLeish Collection at Greenfield Community College in Greenfield, Massachusetts.

Smith College's MacLeish Field Station is named after MacLeish and his wife Ada, who were close friends of former Smith president Jill Ker Conway and introduced her to the natural environment around Northampton, Massachusetts.

Personal life

In 1916, he married Ada Hitchcock, a musician. MacLeish had three children: Kenneth, Mary Hillard, and William, the author of a memoir of his father, ''Uphill with Archie'' (2001). He died in 1982, at the age of 89.Awards and honors

*1933: Pulitzer Prize for Poetry (''Conquistador '') *1946: Commandeur de la Legion d'honneur *1950: elected to theAmerican Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (The Academy) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and other ...

*1953: Pulitzer Prize for Poetry (''Collected Poems 1917–1952'')

*1953: National Book Award for Poetry (''Collected Poems, 1917–1952'')"National Book Awards – 1953"National Book Foundation. Retrieved 2012-03-02.

(With acceptance speech by MacLeish and essay by John Murillo from the Awards 60-year anniversary blog.) *1953: Bollingen Prize in Poetry *1959: Pulitzer Prize for Drama ('' J.B.'') *1959: Tony Award for Best Play (''J.B.'') *1976: elected to the

American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS) is an American scholarly organization and learned society founded in 1743 in Philadelphia that promotes knowledge in the humanities and natural sciences through research, professional meetings, publicat ...

*1977: Presidential Medal of Freedom

Works

Poetry collections

*''Class Poem'' (1915) *''Songs for a Summer's Day'' (1915) *''Tower of Ivory'' (1917) *''The Happy Marriage'' (1924) *''The Pot of Earth'' (1925) *''Nobodaddy'' (1926) *''Streets in the Moon'' (1926) *''The Hamlet of A. Macleish'' (1928) *''Einstein'' (1929) *''New Found Land'' (1930) *''Conquistador'' (1932) *'' Elpenor'' (1933) *''Frescoes for Mr. Rockefeller's City'' (1933) *''Poems, 1924–1933'' (1935) *''Public Speech'' (1936) *''The Land of the Free'' (1938) *''Actfive and Other Poems'' (1948) *''Collected Poems'' (1952) *''Songs for Eve'' (1954) *''The Collected Poems of Archibald MacLeish'' (1962) *''The Wild Old Wicked Man and Other Poems'' (1968) *''The Human Season, Selected Poems 1926–1972'' (1972) *''New and Collected Poems, 1917–1976'' (1976)Prose

*''Jews in America'' (1936) *''America Was Promises'' (1939) *''The Irresponsibles: A Declaration'' (1940) *''The American Cause'' (1941) *''A Time to Speak'' (1941) *''American Opinion and the War: the Rede Lecture'' (1942) *''A Time to Act: Selected Addresses'' (1943) *''Freedom Is the Right to Choose'' (1951) *''Art Education and the Creative Process'' (1954) *''Poetry and Experience'' (1961) *''The Dialogues of Archibald MacLeish and Mark Van Doren'' (1964) *'' The Eleanor Roosevelt Story'' (1965) *''A Continuing Journey'' (1968) *''Champion of a Cause: Essays and Addresses on Librarianship'' (1971) *''Poetry and Opinion: the Pisan Cantos of Ezra Pound'' (1974) *''Riders on the Earth: Essays & Recollections ''(1978) *''Letters of Archibald MacLeish, 1907–1982'' (1983)Drama

*''Union Pacific'' (ballet) (1934) *'' Panic'' (1935) *'' The Fall of the City'' (1937) *''Air Raid: A Verse Play for Radio'' (1938)''The Hartford Courant Magazine''. December 18, 1938. p. 7. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

See also

* List of ambulance drivers during World War INotes

References

*External links

* * Archibald MacLeish Collection anaddition

at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Archibald MacLeish Collection

at the Harry Ransom Center

Archibald MacLeish Papers

at

Mount Holyoke College

Mount Holyoke College is a Private college, private Women's colleges in the United States, women's Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in South Hadley, Massachusetts, United States. It is the oldest member of the h ...

Archibald MacLeish's Grave

*

The Fall of the City

Columbia Workshop, CBS radio, 1937

"Archibald MacLeish"

''Academy of American Poets'' * {{DEFAULTSORT:Macleish, Archibald 1892 births 1982 deaths 20th-century American dramatists and playwrights 20th-century American poets American librarians American people of Scottish descent Amherst College faculty Bollingen Prize recipients Dern family Fortune (magazine) people Harvard Law School alumni Hotchkiss School alumni Librarians of Congress Lost Generation writers Members of Skull and Bones Members of the American Philosophical Society Military personnel from Illinois National Book Award winners People from Glencoe, Illinois People of the United States Office of War Information Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients Presidents of the American Academy of Arts and Letters Psi Upsilon Pulitzer Prize for Drama winners Pulitzer Prize for Poetry winners Tony Award winners United States Army officers United States Army personnel of World War I United States assistant secretaries of state Writers from Illinois Yale University alumni