Aphid Icon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Aphids are small

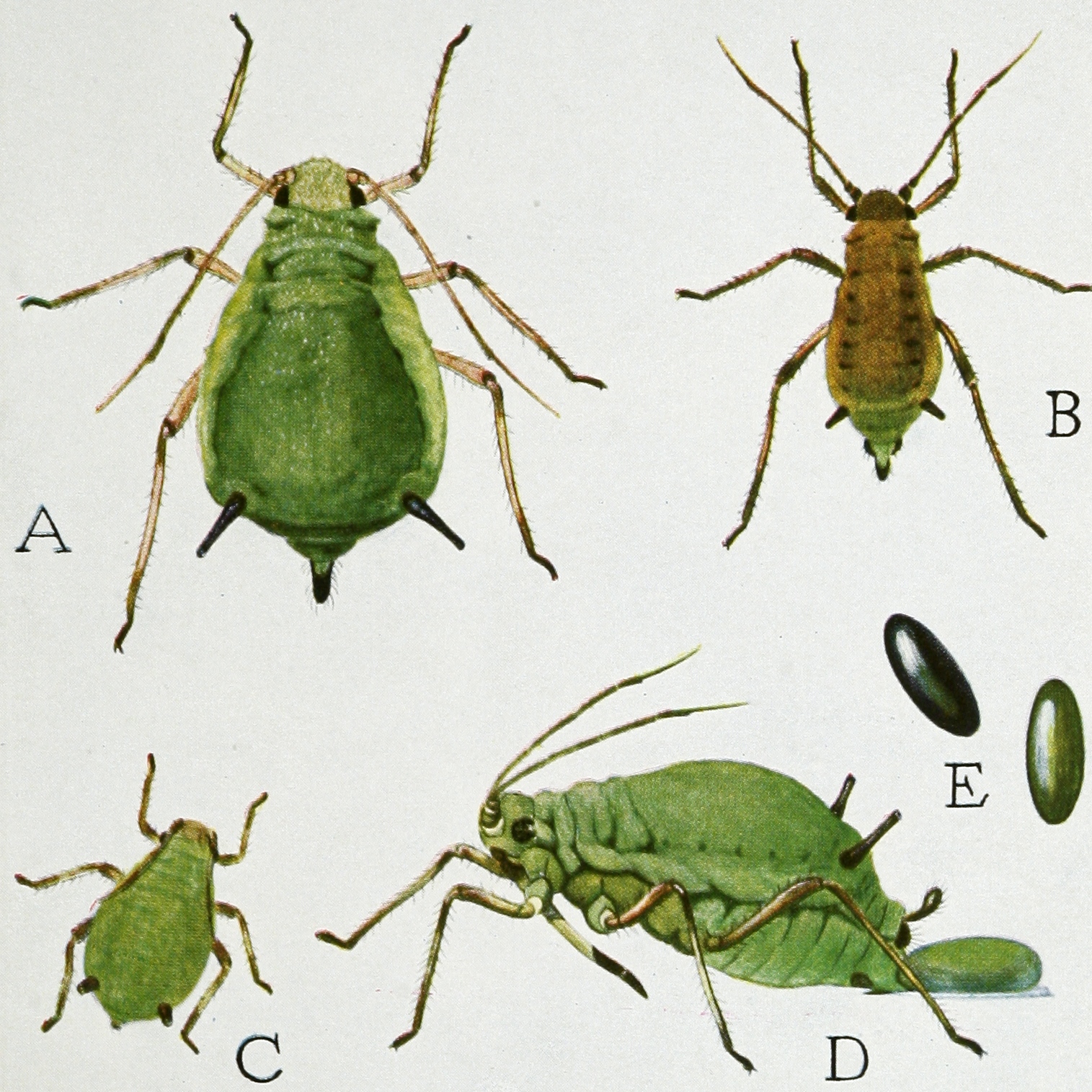

Most aphids have soft bodies, which may be green, black, brown, pink, or almost colorless. Aphids have antennae with two short, broad basal segments and up to four slender terminal segments. They have a pair of

Most aphids have soft bodies, which may be green, black, brown, pink, or almost colorless. Aphids have antennae with two short, broad basal segments and up to four slender terminal segments. They have a pair of

The simplest reproductive strategy is for an aphid to have a single host all year round. On this it may alternate between sexual and asexual generations (holocyclic) or alternatively, all young may be produced by

The simplest reproductive strategy is for an aphid to have a single host all year round. On this it may alternate between sexual and asexual generations (holocyclic) or alternatively, all young may be produced by  In autumn, aphids reproduce sexually and oviparity, lay eggs. Environmental factors such as a change in photoperiod and temperature, or perhaps a lower food quantity or quality, causes females to parthenogenetically produce sexual females and males. The males are genetically identical to their mothers except that, with the aphids' X0 sex-determination system, they have one fewer sex chromosome. These sexual aphids may lack wings or even mouthparts. Sexual females and males mate, and females lay eggs that develop outside the mother. The eggs survive the winter and hatch into winged (alate) or wingless females the following spring. This occurs in, for example, the Biological life cycle, life cycle of the rose aphid (''Macrosiphum rosae''), which may be considered typical of the family. However, in warm environments, such as in the

In autumn, aphids reproduce sexually and oviparity, lay eggs. Environmental factors such as a change in photoperiod and temperature, or perhaps a lower food quantity or quality, causes females to parthenogenetically produce sexual females and males. The males are genetically identical to their mothers except that, with the aphids' X0 sex-determination system, they have one fewer sex chromosome. These sexual aphids may lack wings or even mouthparts. Sexual females and males mate, and females lay eggs that develop outside the mother. The eggs survive the winter and hatch into winged (alate) or wingless females the following spring. This occurs in, for example, the Biological life cycle, life cycle of the rose aphid (''Macrosiphum rosae''), which may be considered typical of the family. However, in warm environments, such as in the

Dysaphis plantaginea

') reproduction, but contributes to the development of aphids with wings, which can transmit the virus more easily to new host plants. Additionally, symbiotic bacteria that live inside of the aphids can also alter aphid reproductive strategies based on the exposure to environmental stressors. In the autumn, host-alternating (heteroecious) aphid species produce a special winged generation that flies to different host plants for the sexual part of the life cycle. Flightless female and male sexual forms are produced and lay eggs. Some species such as ''Aphis fabae'' (black bean aphid), ''Metopolophium dirhodum'' (rose-grain aphid), ''Myzus persicae'' (peach-potato aphid), and ''Rhopalosiphum padi'' (bird cherry-oat aphid) are serious pests. They overwinter on primary hosts on trees or bushes; in summer, they migrate to their secondary host on a herbaceous plant, often a crop, then the gynoparae return to the tree in autumn. Another example is the soybean aphid (''Aphis glycines''). As fall approaches, the soybean plants begin to senesce from the bottom upwards. The aphids are forced upwards and start to produce winged forms, first females and later males, which fly off to the primary host, buckthorn. Here they mate and overwinter as eggs.

In the autumn, host-alternating (heteroecious) aphid species produce a special winged generation that flies to different host plants for the sexual part of the life cycle. Flightless female and male sexual forms are produced and lay eggs. Some species such as ''Aphis fabae'' (black bean aphid), ''Metopolophium dirhodum'' (rose-grain aphid), ''Myzus persicae'' (peach-potato aphid), and ''Rhopalosiphum padi'' (bird cherry-oat aphid) are serious pests. They overwinter on primary hosts on trees or bushes; in summer, they migrate to their secondary host on a herbaceous plant, often a crop, then the gynoparae return to the tree in autumn. Another example is the soybean aphid (''Aphis glycines''). As fall approaches, the soybean plants begin to senesce from the bottom upwards. The aphids are forced upwards and start to produce winged forms, first females and later males, which fly off to the primary host, buckthorn. Here they mate and overwinter as eggs.

Some species of

Some species of  An interesting variation in ant–aphid relationships involves Lycaenidae, lycaenid butterflies and ''Myrmica'' ants. For example, ''Niphanda fusca'' butterflies lay eggs on plants where ants tend herds of aphids. The eggs hatch as caterpillars which feed on the aphids. The ants do not defend the aphids from the caterpillars, since the caterpillars produce a pheromone which deceives the ants into treating them like ants, and carrying the caterpillars into their nest. Once there, the ants feed the caterpillars, which in return produce honeydew for the ants. When the caterpillars reach full size, they crawl to the colony entrance and form Cocoon (silk), cocoons. After two weeks, the adult butterflies emerge and take flight. At this point, the ants attack the butterflies, but the butterflies have a sticky wool-like substance on their wings that disables the ants' jaws, allowing the butterflies to fly away without being harmed.

Another ant mimicry, ant-mimicking gall aphid, ''Paracletus cimiciformis'' (Eriosomatinae), has evolved a complex double strategy involving two morphs of the same clone and ''Tetramorium'' ants. Aphids of the round morph cause the ants to farm them, as with many other aphids. The flat morph aphids are aggressive mimicry, aggressive mimics with a "wolf in sheep's clothing" strategy: they have hydrocarbons in their cuticle that mimic those of the ants, and the ants carry them into the brood chamber of the ants' nest and raise them like ant larvae. Once there, the flat morph aphids behave like predators, drinking the body fluids of ant larvae.

An interesting variation in ant–aphid relationships involves Lycaenidae, lycaenid butterflies and ''Myrmica'' ants. For example, ''Niphanda fusca'' butterflies lay eggs on plants where ants tend herds of aphids. The eggs hatch as caterpillars which feed on the aphids. The ants do not defend the aphids from the caterpillars, since the caterpillars produce a pheromone which deceives the ants into treating them like ants, and carrying the caterpillars into their nest. Once there, the ants feed the caterpillars, which in return produce honeydew for the ants. When the caterpillars reach full size, they crawl to the colony entrance and form Cocoon (silk), cocoons. After two weeks, the adult butterflies emerge and take flight. At this point, the ants attack the butterflies, but the butterflies have a sticky wool-like substance on their wings that disables the ants' jaws, allowing the butterflies to fly away without being harmed.

Another ant mimicry, ant-mimicking gall aphid, ''Paracletus cimiciformis'' (Eriosomatinae), has evolved a complex double strategy involving two morphs of the same clone and ''Tetramorium'' ants. Aphids of the round morph cause the ants to farm them, as with many other aphids. The flat morph aphids are aggressive mimicry, aggressive mimics with a "wolf in sheep's clothing" strategy: they have hydrocarbons in their cuticle that mimic those of the ants, and the ants carry them into the brood chamber of the ants' nest and raise them like ant larvae. Once there, the flat morph aphids behave like predators, drinking the body fluids of ant larvae.

Most aphids have little protection from predators. Some species interact with plant tissues forming a gall, an abnormal swelling of plant tissue. Aphids can live inside the gall, which provides protection from predators and the elements. A number of galling aphid species are known to produce specialised "soldier" forms, sterile nymphs with defensive features which defend the gall from invasion. For example, Alexander's horned aphids are a type of soldier aphid that has a hard exoskeleton and pincer (biology), pincer-like mouthparts. A woolly aphid, ''Colophina clematis'', has first instar "soldier" larvae that protect the aphid colony, killing larvae of ladybirds, hoverflies and the flower bug ''Anthocoris nemoralis'' by climbing on them and inserting their stylets.

Although aphids cannot fly for most of their life cycle, they can escape predators and accidental ingestion by herbivores by dropping off the plant onto the ground. Others species use the soil as a permanent protection, feeding on the vascular systems of roots and remaining underground all their lives. They are often attended by ants, for the honeydew they produce and are carried from plant to plant by the ants through their tunnels.

Some species of aphid, known as "woolly aphids" (Eriosomatinae), excrete a "fluffy wax coating" for protection. The cabbage aphid, ''Brevicoryne brassicae'', sequesters secondary metabolites from its host, stores them and releases chemicals that produce a violent chemical reaction and strong mustard oil smell to repel predators. Peptides produced by aphids, Thaumatins, are thought to provide them with resistance to some fungi.

It was common at one time to suggest that the cornicles were the source of the honeydew, and this was even included in the ''Shorter Oxford English Dictionary'' and the 2008 edition of the ''World Book Encyclopedia''. In fact, honeydew secretions are produced from the anus of the aphid, while cornicles mostly produce defensive chemicals such as waxes. There also is evidence of cornicle wax Kairomone, attracting aphid predators in some cases.

Some clones of ''Aphis craccivora'' are sufficiently toxic to the invasive and dominant predatory ladybird ''Harmonia axyridis'' to suppress it locally, favouring other ladybird species; the toxicity is in this case narrowly specific to the dominant predator species.

Most aphids have little protection from predators. Some species interact with plant tissues forming a gall, an abnormal swelling of plant tissue. Aphids can live inside the gall, which provides protection from predators and the elements. A number of galling aphid species are known to produce specialised "soldier" forms, sterile nymphs with defensive features which defend the gall from invasion. For example, Alexander's horned aphids are a type of soldier aphid that has a hard exoskeleton and pincer (biology), pincer-like mouthparts. A woolly aphid, ''Colophina clematis'', has first instar "soldier" larvae that protect the aphid colony, killing larvae of ladybirds, hoverflies and the flower bug ''Anthocoris nemoralis'' by climbing on them and inserting their stylets.

Although aphids cannot fly for most of their life cycle, they can escape predators and accidental ingestion by herbivores by dropping off the plant onto the ground. Others species use the soil as a permanent protection, feeding on the vascular systems of roots and remaining underground all their lives. They are often attended by ants, for the honeydew they produce and are carried from plant to plant by the ants through their tunnels.

Some species of aphid, known as "woolly aphids" (Eriosomatinae), excrete a "fluffy wax coating" for protection. The cabbage aphid, ''Brevicoryne brassicae'', sequesters secondary metabolites from its host, stores them and releases chemicals that produce a violent chemical reaction and strong mustard oil smell to repel predators. Peptides produced by aphids, Thaumatins, are thought to provide them with resistance to some fungi.

It was common at one time to suggest that the cornicles were the source of the honeydew, and this was even included in the ''Shorter Oxford English Dictionary'' and the 2008 edition of the ''World Book Encyclopedia''. In fact, honeydew secretions are produced from the anus of the aphid, while cornicles mostly produce defensive chemicals such as waxes. There also is evidence of cornicle wax Kairomone, attracting aphid predators in some cases.

Some clones of ''Aphis craccivora'' are sufficiently toxic to the invasive and dominant predatory ladybird ''Harmonia axyridis'' to suppress it locally, favouring other ladybird species; the toxicity is in this case narrowly specific to the dominant predator species.

Plants mount local and systemic defenses against aphid attack. Young leaves in some plants contain chemicals that discourage attack while the older leaves have lost this resistance, while in other plant species, resistance is acquired by older tissues and the young shoots are vulnerable. Volatile products from interplanted onions have been shown to prevent aphid attack on adjacent potato plants by encouraging the production of terpenoids, a benefit exploited in the traditional practice of companion planting, while plants neighboring infested plants showed increased root growth at the expense of the extension of aerial parts. The wild potato, ''Solanum berthaultii'', produces an aphid alarm pheromone, (E)-β-farnesene, as an allomone, a pheromone to ward off attack; it effectively repels the aphid ''Myzus persicae'' at a range of up to 3 millimetres. ''S. berthaultii'' and other wild potato species have a further anti-aphid defence in the form of glandular hairs which, when broken by aphids, discharge a sticky liquid that can immobilise some 30% of the aphids infesting a plant.

Plants exhibiting aphid damage can have a variety of symptoms, such as decreased growth rates, mottled leaves, yellowing, stunted growth, curled leaves, browning, wilting, low yields, and death. The removal of sap creates a lack of vigor in the plant, and aphid saliva is toxic to plants. Aphids frequently transmit

Plants mount local and systemic defenses against aphid attack. Young leaves in some plants contain chemicals that discourage attack while the older leaves have lost this resistance, while in other plant species, resistance is acquired by older tissues and the young shoots are vulnerable. Volatile products from interplanted onions have been shown to prevent aphid attack on adjacent potato plants by encouraging the production of terpenoids, a benefit exploited in the traditional practice of companion planting, while plants neighboring infested plants showed increased root growth at the expense of the extension of aerial parts. The wild potato, ''Solanum berthaultii'', produces an aphid alarm pheromone, (E)-β-farnesene, as an allomone, a pheromone to ward off attack; it effectively repels the aphid ''Myzus persicae'' at a range of up to 3 millimetres. ''S. berthaultii'' and other wild potato species have a further anti-aphid defence in the form of glandular hairs which, when broken by aphids, discharge a sticky liquid that can immobilise some 30% of the aphids infesting a plant.

Plants exhibiting aphid damage can have a variety of symptoms, such as decreased growth rates, mottled leaves, yellowing, stunted growth, curled leaves, browning, wilting, low yields, and death. The removal of sap creates a lack of vigor in the plant, and aphid saliva is toxic to plants. Aphids frequently transmit  The coating of plants with honeydew can contribute to the spread of fungi which can damage plants. Honeydew produced by aphids has been observed to reduce the effectiveness of fungicides as well.

A hypothesis that insect feeding may improve plant fitness was floated in the mid-1970s by Owen and Wiegert. It was felt that the excess honeydew would nourish soil micro-organisms, including nitrogen fixers. In a nitrogen-poor environment, this could provide an advantage to an infested plant over an uninfested plant. However, this does not appear to be supported by observational evidence.

The coating of plants with honeydew can contribute to the spread of fungi which can damage plants. Honeydew produced by aphids has been observed to reduce the effectiveness of fungicides as well.

A hypothesis that insect feeding may improve plant fitness was floated in the mid-1970s by Owen and Wiegert. It was felt that the excess honeydew would nourish soil micro-organisms, including nitrogen fixers. In a nitrogen-poor environment, this could provide an advantage to an infested plant over an uninfested plant. However, this does not appear to be supported by observational evidence.

Insecticide control of aphids is difficult, as they breed rapidly, so even small areas missed may enable the population to recover promptly. Aphids may occupy the undersides of leaves where spray misses them, while systemic insecticides do not move satisfactorily into flower petals. Finally, some aphid species are insecticide resistance, resistant to common insecticide classes including carbamates, organophosphates, and pyrethroids.

For small backyard infestations, spraying plants thoroughly with a strong water jet every few days may be sufficient protection. An insecticidal soap solution can be an effective household remedy to control aphids, but it only kills aphids on contact and has no residual effect. Soap spray may damage plants, especially at higher concentrations or at temperatures above ; some plant species are sensitive to soap sprays.

Insecticide control of aphids is difficult, as they breed rapidly, so even small areas missed may enable the population to recover promptly. Aphids may occupy the undersides of leaves where spray misses them, while systemic insecticides do not move satisfactorily into flower petals. Finally, some aphid species are insecticide resistance, resistant to common insecticide classes including carbamates, organophosphates, and pyrethroids.

For small backyard infestations, spraying plants thoroughly with a strong water jet every few days may be sufficient protection. An insecticidal soap solution can be an effective household remedy to control aphids, but it only kills aphids on contact and has no residual effect. Soap spray may damage plants, especially at higher concentrations or at temperatures above ; some plant species are sensitive to soap sprays.

Aphid populations can be sampled using yellow-pan or Volker Moericke, Moericke traps. These are yellow containers with water that attract aphids. Aphids respond positively to green and their attraction to yellow may not be a true colour preference but related to brightness. Their visual receptors peak in sensitivity from 440 to 480 nm and are insensitive in the red region. Moericke found that aphids avoided landing on white coverings placed on soil and were repelled even more by shiny aluminium surfaces. Integrated pest management of various species of aphids can be achieved using biological insecticides based on fungi such as ''Lecanicillium lecanii'', ''Beauveria bassiana'' or ''Isaria fumosorosea''. Fungi are the main pathogens of aphids; Entomophthorales can quickly cut aphid numbers in nature.

Aphids may also be Biological pest control, controlled by the release of natural enemies, in particular lady beetles and parasitoid wasps. However, since adult lady beetles tend to fly away within 48 hours after release, without laying eggs, repeated applications of large numbers of lady beetles are needed to be effective. For example, one large, heavily infested rose bush may take two applications of 1500 beetles each.

The ability to produce allomones such as farnesene to repel and disperse aphids and to attract their predators has been experimentally transferred to transgenic ''Arabidopsis thaliana'' plants using an Eβf synthase gene in the hope that the approach could protect transgenic crops. Eβ farnesene has however found to be ineffective in crop situations although stabler synthetic forms help improve the effectiveness of control using fungal spores and insecticides through increased uptake caused by movements of aphids.

Aphid populations can be sampled using yellow-pan or Volker Moericke, Moericke traps. These are yellow containers with water that attract aphids. Aphids respond positively to green and their attraction to yellow may not be a true colour preference but related to brightness. Their visual receptors peak in sensitivity from 440 to 480 nm and are insensitive in the red region. Moericke found that aphids avoided landing on white coverings placed on soil and were repelled even more by shiny aluminium surfaces. Integrated pest management of various species of aphids can be achieved using biological insecticides based on fungi such as ''Lecanicillium lecanii'', ''Beauveria bassiana'' or ''Isaria fumosorosea''. Fungi are the main pathogens of aphids; Entomophthorales can quickly cut aphid numbers in nature.

Aphids may also be Biological pest control, controlled by the release of natural enemies, in particular lady beetles and parasitoid wasps. However, since adult lady beetles tend to fly away within 48 hours after release, without laying eggs, repeated applications of large numbers of lady beetles are needed to be effective. For example, one large, heavily infested rose bush may take two applications of 1500 beetles each.

The ability to produce allomones such as farnesene to repel and disperse aphids and to attract their predators has been experimentally transferred to transgenic ''Arabidopsis thaliana'' plants using an Eβf synthase gene in the hope that the approach could protect transgenic crops. Eβ farnesene has however found to be ineffective in crop situations although stabler synthetic forms help improve the effectiveness of control using fungal spores and insecticides through increased uptake caused by movements of aphids.

Aphids of southeastern U.S. woody ornamentals

''Acyrthosiphon pisum''

MetaPathogen – facts, life cycle, life cycle image

Agricultural Research Service

Insect Olfaction of Plant Odour: Colorado Potato Beetle and Aphid Studies

Center for Invasive Species Research On the University of Florida / Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences ''Featured Creatures'' website:

''Aphis gossypii'', melon or cotton aphid

{{Authority control Aphids, Agricultural pest insects Insect pests of temperate forests Insect pests of ornamental plants Insect vectors of plant pathogens Sternorrhyncha Extant Permian first appearances Insects in culture

sap

Sap is a fluid transported in xylem cells (vessel elements or tracheids) or phloem sieve tube elements of a plant. These cells transport water and nutrients throughout the plant.

Sap is distinct from latex, resin, or cell sap; it is a separ ...

-sucking insect

Insects (from Latin ') are pancrustacean hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (head, thorax and abdomen), three pairs ...

s and members of the superfamily

SUPERFAMILY is a database and search platform of structural and functional annotation for all proteins and genomes. It classifies amino acid sequences into known structural domains, especially into SCOP superfamilies. Domains are functional, str ...

Aphidoidea. Common names include greenfly and blackfly, although individuals within a species can vary widely in color. The group includes the fluffy white woolly aphids. A typical life cycle involves flightless females giving live birth to female nymphs

A nymph ( grc, νύμφη, nýmphē, el, script=Latn, nímfi, label=Modern Greek; , ) in ancient Greek folklore is a minor female nature deity. Different from Greek goddesses, nymphs are generally regarded as personifications of nature, are ty ...

—who may also be already pregnant

Pregnancy is the time during which one or more offspring develops ( gestates) inside a woman's uterus (womb). A multiple pregnancy involves more than one offspring, such as with twins.

Pregnancy usually occurs by sexual intercourse, but ...

, an adaptation scientists call telescoping generations—without the involvement of males. Maturing rapidly, females breed profusely so that the number of these insects multiplies quickly. Winged females may develop later in the season, allowing the insects to colonize new plants. In temperate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (23.5° to 66.5° N/S of Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ranges throughout t ...

regions, a phase of sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction is a type of reproduction that involves a complex life cycle in which a gamete ( haploid reproductive cells, such as a sperm or egg cell) with a single set of chromosomes combines with another gamete to produce a zygote th ...

occurs in the autumn

Autumn, also known as fall in American English and Canadian English, is one of the four temperate seasons on Earth. Outside the tropics, autumn marks the transition from summer to winter, in September (Northern Hemisphere) or March ( S ...

, with the insects often overwintering as eggs

Humans and human ancestors have scavenged and eaten animal eggs for millions of years. Humans in Southeast Asia had domesticated chickens and harvested their eggs for food by 1,500 BCE. The most widely consumed eggs are those of fowl, especial ...

.

The life cycle of some species involves an alternation between two species of host plants, for example between an annual crop and a woody plant

A woody plant is a plant that produces wood as its structural tissue and thus has a hard stem. In cold climates, woody plants further survive winter or dry season above ground, as opposite to herbaceous plants that die back to the ground until s ...

. Some species feed on only one type of plant, while others are generalists, colonizing many plant groups. About 5,000 species of aphid have been described, all included in the family Aphididae

The Aphididae are a very large insect family in the aphid superfamily ( Aphidoidea), of the order Hemiptera. These insects suck the sap from plant leaves. Several thousand species are placed in this family, many of which are considered plant/cr ...

. Around 400 of these are found on food

Food is any substance consumed by an organism for nutritional support. Food is usually of plant, animal, or fungal origin, and contains essential nutrients, such as carbohydrates, fats, proteins, vitamins, or minerals. The substance is ...

and fiber crops, and many are serious pests of agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled peop ...

and forestry

Forestry is the science and craft of creating, managing, planting, using, conserving and repairing forests, woodlands, and associated resources for human and environmental benefits. Forestry is practiced in plantations and natural stands. ...

, as well as an annoyance for gardener

A gardener is someone who practices gardening, either professionally or as a hobby.

Description

A gardener is any person involved in gardening, arguably the oldest occupation, from the hobbyist in a residential garden, the home-owner supple ...

s. So-called dairying ant

Ants are eusocial insects of the family Formicidae and, along with the related wasps and bees, belong to the order Hymenoptera. Ants evolved from vespoid wasp ancestors in the Cretaceous period. More than 13,800 of an estimated total of 22,0 ...

s have a mutualistic relationship with aphids, tending them for their honeydew, and protecting them from predator

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill ...

s.

Aphids are among the most destructive insect pests on cultivated plants in temperate regions. In addition to weakening the plant by sucking sap, they act as vectors for plant virus

Plant viruses are viruses that affect plants. Like all other viruses, plant viruses are obligate intracellular parasites that do not have the molecular machinery to replicate without a host. Plant viruses can be pathogenic to higher plants.

...

es and disfigure ornamental plants with deposits of honeydew and the subsequent growth of sooty mould

Sooty mold (also spelled sooty mould) is a collective term for different Ascomycete fungi, which includes many genera, commonly '' Cladosporium'' and '' Alternaria''. It grows on plants and their fruit, but also environmental objects, like fences ...

s. Because of their ability to rapidly increase in numbers by asexual reproduction and telescopic development, they are a highly successful group of organisms from an ecological standpoint.

Control of aphids is not easy. Insecticides

Insecticides are substances used to kill insects. They include ovicides and larvicides used against insect eggs and larvae, respectively. Insecticides are used in agriculture, medicine, industry and by consumers. Insecticides are claimed t ...

do not always produce reliable results, given resistance to several classes of insecticide and the fact that aphids often feed on the undersides of leaves. On a garden scale, water jets and soap sprays are quite effective. Natural enemies include predatory ladybugs, hoverfly

Hover flies, also called flower flies or syrphid flies, make up the insect family Syrphidae. As their common name suggests, they are often seen hovering or nectaring at flowers; the adults of many species feed mainly on nectar and pollen, while ...

larvae, parasitic wasp

Parasitoid wasps are a large group of hymenopteran superfamilies, with all but the wood wasps ( Orussoidea) being in the wasp-waisted Apocrita. As parasitoids, they lay their eggs on or in the bodies of other arthropods, sooner or later cau ...

s, aphid midge larvae, crab spider

The Thomisidae are a family of spiders, including about 170 genera and over 2,100 species. The common name crab spider is often linked to species in this family, but is also applied loosely to many other families of spiders. Many members of t ...

s, lacewing

The insect order (biology), order Neuroptera, or net-winged insects, includes the lacewings, Mantispidae, mantidflies, antlions, and their relatives. The order consists of some 6,000 species. Neuroptera can be grouped together with the Megalopt ...

larvae, and entomopathogenic fungi. An integrated pest management

Integrated pest management (IPM), also known as integrated pest control (IPC) is a broad-based approach that integrates both chemical and non-chemical practices for economic control of pests. IPM aims to suppress pest populations below the eco ...

strategy using biological pest control

Biological control or biocontrol is a method of controlling pests, such as insects, mites, weeds, and plant diseases, using other organisms. It relies on predation, parasitism, herbivory, or other natural mechanisms, but typically also i ...

can work, but is difficult to achieve except in enclosed environments such as greenhouses

A greenhouse (also called a glasshouse, or, if with sufficient heating, a hothouse) is a structure with walls and roof made chiefly of transparent material, such as glass, in which plants requiring regulated climatic conditions are grown.These ...

.

Distribution

Aphids are distributed worldwide, but are most common intemperate zone

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (23.5° to 66.5° N/S of Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ranges throughout ...

s. In contrast to many taxa

In biology, a taxon ( back-formation from '' taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular n ...

, aphid species diversity is much lower in the tropics

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the Equator. They are defined in latitude by the Tropic of Cancer in the Northern Hemisphere at N and the Tropic of Capricorn in

the Southern Hemisphere at S. The tropics are also referred ...

than in the temperate zones. They can migrate great distances, mainly through passive dispersal by winds. Winged aphids may also rise up in the day as high as 600 m where they are transported by strong winds. For example, the currant-lettuce aphid, '' Nasonovia ribisnigri'', is believed to have spread from New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 List of islands of New Zealand, smaller islands. It is the ...

to Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

around 2004 through easterly winds. Aphids have also been spread by human transportation of infested plant materials, making some species nearly cosmopolitan in their distribution.

Evolution

Fossil history

Aphids, and the closely related adelgids and phylloxerans, probably evolved from acommon ancestor

Common descent is a concept in evolutionary biology applicable when one species is the ancestor of two or more species later in time. All living beings are in fact descendants of a unique ancestor commonly referred to as the last universal comm ...

some , in the Early Permian 01 or '01 may refer to:

* The year 2001, or any year ending with 01

* The month of January

* 1 (number)

Music

* 01'' (Richard Müller album), 2001

* ''01'' (Son of Dave album), 2000

* ''01'' (Urban Zakapa album), 2011

* ''O1'' (Hiroyuki Sawano ...

period. They probably fed on plants like Cordaitales

Cordaitales are an extinct order of gymnosperms, known from the early Carboniferous to the late Permian. Many Cordaitales had elongated strap-like leaves, resembling some modern-day conifers of the Araucariaceae and Podocarpaceae. They had cone ...

or Cycadophyta

Cycads are seed plants that typically have a stout and woody ( ligneous) trunk with a crown of large, hard, stiff, evergreen and (usually) pinnate leaves. The species are dioecious, that is, individual plants of a species are either male or ...

. With their soft bodies, aphids do not fossilize well, and the oldest known fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

is of the species '' Triassoaphis cubitus'' from the Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.36 Mya. The Triassic is the first and shortest period ...

. They do however sometimes get stuck in plant exudates which solidify into amber

Amber is fossilized tree resin that has been appreciated for its color and natural beauty since Neolithic times. Much valued from antiquity to the present as a gemstone, amber is made into a variety of decorative objects."Amber" (2004). In M ...

. In 1967, when Professor Ole Heie wrote his monograph ''Studies on Fossil Aphids'', about sixty species have been described from the Triassic, Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The J ...

, Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

and mostly the Tertiary

Tertiary ( ) is a widely used but obsolete term for the geologic period from 66 million to 2.6 million years ago.

The period began with the demise of the non- avian dinosaurs in the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, at the start ...

periods, with Baltic amber

The Baltic region is home to the largest known deposit of amber, called Baltic amber or succinite. It was produced sometime during the Eocene epoch, but exactly when is controversial. It has been estimated that these forests created more than 1 ...

contributing another forty species. The total number of species was small, but increased considerably with the appearance of the angiosperm

Flowering plants are plants that bear flowers and fruits, and form the clade Angiospermae (), commonly called angiosperms. They include all forbs (flowering plants without a woody stem), grasses and grass-like plants, a vast majority of br ...

s , as this allowed aphids to specialise, the speciation of aphids going hand-in-hand with the diversification of flowering plants. The earliest aphids were probably polyphagous

Feeding is the process by which organisms, typically animals, obtain food. Terminology often uses either the suffixes -vore, -vory, or -vorous from Latin ''vorare'', meaning "to devour", or -phage, -phagy, or -phagous from Greek φαγ� ...

, with monophagy developing later. It has been hypothesized that the ancestors of the Adelgidae

The Adelgidae are a small family of the Hemiptera closely related to the aphids, and often included in the Aphidoidea with the Phylloxeridae or placed within the superfamily Phylloxeroidea as a sister of the Aphidoidea within the infraorder A ...

lived on conifer

Conifers are a group of cone-bearing seed plants, a subset of gymnosperms. Scientifically, they make up the division Pinophyta (), also known as Coniferophyta () or Coniferae. The division contains a single extant class, Pinopsida. All ex ...

s while those of the Aphididae fed on the sap of Podocarpaceae

Podocarpaceae is a large family of mainly Southern Hemisphere conifers, known in English as podocarps, comprising about 156 species of evergreen trees and shrubs.James E. Eckenwalder. 2009. ''Conifers of the World''. Portland, Oregon: Timber Pre ...

or Araucariaceae

Araucariaceae – also known as araucarians – is an extremely ancient family of coniferous trees. The family achieved its maximum diversity during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods and the early Cenozoic, when it was distributed almost world ...

that survived extinctions in the late Cretaceous. Organs like the cornicles did not appear until the Cretaceous period. One study alternatively suggests that ancestral aphids may have lived on angiosperm bark and that feeding on leaves may be a derived trait

In phylogenetics, an apomorphy (or derived trait) is a novel character or character state that has evolved from its ancestral form (or plesiomorphy). A synapomorphy is an apomorphy shared by two or more taxa and is therefore hypothesized to have ...

. The Lachninae

Lachninae is a subfamily of the family Aphididae, containing some of the largest aphids, and they are sometimes referred to as "giant aphids". Members of this subfamily typically have greatly reduced cornicles compared to other aphids, and the ...

have long mouth parts that are suitable for living on bark and it has been suggested that the mid-Cretaceous ancestor fed on the bark of angiosperm trees, switching to leaves of conifer hosts in the late Cretaceous. The Phylloxeridae may well be the oldest family still extant, but their fossil record is limited to the Lower Miocene

The Early Miocene (also known as Lower Miocene) is a sub-epoch of the Miocene Epoch made up of two stages: the Aquitanian and Burdigalian stages.

The sub-epoch lasted from 23.03 ± 0.05 Ma to 15.97 ± 0.05 Ma (million years ago). It was prec ...

'' Palaeophylloxera''.

Taxonomy

Late 20th-century reclassification within the Hemiptera reduced the old taxon "Homoptera" to two suborders:Sternorrhyncha

The Sternorrhyncha suborder of the Hemiptera contains the aphids, whiteflies, and scale insects, groups which were traditionally included in the now-obsolete order "Homoptera". "Sternorrhyncha" refers to the rearward position of the mouthparts re ...

(aphids, whiteflies, scales

Scale or scales may refer to:

Mathematics

* Scale (descriptive set theory), an object defined on a set of points

* Scale (ratio), the ratio of a linear dimension of a model to the corresponding dimension of the original

* Scale factor, a number ...

, psyllids, etc.) and Auchenorrhyncha

The Auchenorrhyncha suborder of the Hemiptera contains most of the familiar members of what was called the "Homoptera" – groups such as cicadas, leafhoppers, treehoppers, planthoppers, and spittlebugs. The aphids and scale insects are the ot ...

(cicada

The cicadas () are a superfamily, the Cicadoidea, of insects in the order Hemiptera (true bugs). They are in the suborder Auchenorrhyncha, along with smaller jumping bugs such as leafhoppers and froghoppers. The superfamily is divided into two ...

s, leafhopper

A leafhopper is the common name for any species from the family Cicadellidae. These minute insects, colloquially known as hoppers, are plant feeders that suck plant sap from grass, shrubs, or trees. Their hind legs are modified for jumping, and ...

s, treehopper

Treehoppers (more precisely typical treehoppers to distinguish them from the Aetalionidae) and thorn bugs are members of the family Membracidae, a group of insects related to the cicadas and the leafhoppers. About 3,200 species of treehoppers in ...

s, planthopper

A planthopper is any insect in the infraorder Fulgoromorpha, in the suborder Auchenorrhyncha, a group exceeding 12,500 described species worldwide. The name comes from their remarkable resemblance to leaves and other plants of their environment ...

s, etc.) with the suborder Heteroptera containing a large group of insects known as the true bugs

Hemiptera (; ) is an order of insects, commonly called true bugs, comprising over 80,000 species within groups such as the cicadas, aphids, planthoppers, leafhoppers, assassin bugs, bed bugs, and shield bugs. They range in size from to a ...

. The infraorder Aphidomorpha within the Sternorrhyncha varies with circumscription with several fossil groups being especially difficult to place but includes the Adelgoidea, the Aphidoidea and the Phylloxeroidea. Some authors use a single superfamily Aphidoidea within which the Phylloxeridae and Adelgidae are also included while others have Aphidoidea with a sister superfamily Phylloxeroidea within which the Adelgidae and Phylloxeridae are placed. Early 21st-century reclassifications substantially rearranged the families within Aphidoidea: some old families were reduced to subfamily rank (''e.g.'', Eriosomatidae

Woolly aphids (subfamily: Eriosomatinae) are sap-sucking insects that produce a filamentous waxy white covering which resembles cotton or wool. The adults are winged and move to new locations where they lay egg masses. The nymphs often form ...

), and many old subfamilies were elevated to family rank. The most recent authoritative classifications have three superfamilies Adelgoidea, Phylloxeroidea and Aphidoidea. The Aphidoidea includes a single large family Aphididae

The Aphididae are a very large insect family in the aphid superfamily ( Aphidoidea), of the order Hemiptera. These insects suck the sap from plant leaves. Several thousand species are placed in this family, many of which are considered plant/cr ...

that includes all the ~5000 extant species.

Phylogeny

External

Aphids, adelgids, and phylloxerids are very closely related, and are all within the suborder Sternorrhyncha, the plant-sucking bugs. They are either placed in the insect superfamily Aphidoidea or into the superfamily Phylloxeroidea which contains the family Adelgidae and the family Phylloxeridae. Like aphids, phylloxera feed on the roots, leaves, and shoots of grape plants, but unlike aphids, do not produce honeydew orcornicle

The cornicle (or siphuncule) is one of a pair of small upright backward-pointing tubes found on the dorsal side of the 5th or 6th abdominal segments of aphids. They are sometimes mistaken for cerci. They are no more than pores in some species.

...

secretions. Phylloxera (''Daktulosphaira vitifoliae'') are insects which caused the Great French Wine Blight

The Great French Wine Blight was a severe blight of the mid-19th century that destroyed many of the vineyards in France and laid waste to the wine industry. It was caused by an aphid that originated in North America and was carried across the At ...

that devastated European viticulture

Viticulture (from the Latin word for ''vine'') or winegrowing (wine growing) is the cultivation and harvesting of grapes. It is a branch of the science of horticulture. While the native territory of ''Vitis vinifera'', the common grape vine, ran ...

in the 19th century. Similarly, adelgids or woolly conifer aphids, also feed on plant phloem and are sometimes described as aphids, but are more properly classified as aphid-like insects, because they have no cauda or cornicles.

The treatment of the groups especially concerning fossil groups varies greatly due to difficulties in resolving relationships. Most modern treatments include the three superfamilies, the Adelogidea, the Aphidoidea, and the Phylloxeroidea within the infraorder Aphidomorpha along with several fossil groups but other treatments have the Aphidomorpha containing the Aphidoidea with the families Aphididae, Phylloxeridae and Adelgidae; or the Aphidomorpha with two superfamilies, Aphidoidea and Phylloxeroidea, the latter containing the Phylloxeridae and the Adelgidae.

The phylogenetic tree of the Sternorrhyncha is inferred from analysis of small subunit (18S) ribosomal RNA

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) is a type of non-coding RNA which is the primary component of ribosomes, essential to all cells. rRNA is a ribozyme which carries out protein synthesis in ribosomes. Ribosomal RNA is transcribed from ribosomal ...

.

Internal

The phylogenetic tree, based on Papasotiropoulos 2013 and Kim 2011, with additions from Ortiz-Rivas and Martinez-Torres 2009, shows the internalphylogeny

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological spe ...

of the Aphididae.

It has been suggested that the phylogeny of the aphid groups might be revealed by examining the phylogeny of their bacterial endosymbiont

An ''endosymbiont'' or ''endobiont'' is any organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism most often, though not always, in a mutualistic relationship.

(The term endosymbiosis is from the Greek: ἔνδον ''endon'' "withi ...

s, especially the obligate endosymbiont '' Buchnera''. The results depend on the assumption that the symbionts are strictly transmitted vertically through the generations. This assumption is well supported by the evidence, and several phylogenetic relationships have been suggested on the basis of endosymbiont studies.

Anatomy

Most aphids have soft bodies, which may be green, black, brown, pink, or almost colorless. Aphids have antennae with two short, broad basal segments and up to four slender terminal segments. They have a pair of

Most aphids have soft bodies, which may be green, black, brown, pink, or almost colorless. Aphids have antennae with two short, broad basal segments and up to four slender terminal segments. They have a pair of compound eye

A compound eye is a visual organ found in arthropods such as insects and crustaceans. It may consist of thousands of ommatidia, which are tiny independent photoreception units that consist of a cornea, lens, and photoreceptor cells which dis ...

s, with an ocular tubercle behind and above each eye, made up of three lenses (called triommatidia). They feed on sap using sucking mouthparts called stylets, enclosed in a sheath called a rostrum, which is formed from modifications of the mandible

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movable bon ...

and maxilla

The maxilla (plural: ''maxillae'' ) in vertebrates is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The ...

of the insect mouthparts.

They have long, thin legs with two-jointed, two-clawed tarsi. The majority of aphids are wingless, but winged forms are produced at certain times of year in many species. Most aphids have a pair of cornicles (siphunculi), abdominal tubes on the dorsal surface of their fifth abdominal segment, through which they exude droplets of a quick-hardening defensive fluid containing triacylglycerol

A triglyceride (TG, triacylglycerol, TAG, or triacylglyceride) is an ester derived from glycerol and three fatty acids (from '' tri-'' and '' glyceride'').

Triglycerides are the main constituents of body fat in humans and other vertebrates, a ...

s, called cornicle wax. Other defensive compounds can also be produced by some species. Aphids have a tail-like protrusion called a cauda above their rectal apertures. They have lost their Malpighian tubules

The Malpighian tubule system is a type of excretory and osmoregulatory system found in some insects, myriapods, arachnids and tardigrades.

The system consists of branching tubules extending from the alimentary canal that absorbs solutes, water ...

.

When host plant quality becomes poor or conditions become crowded, some aphid species produce winged offspring (alate

Alate (Latin ''ālātus'', from ''āla'' (“wing”)) is an adjective and noun used in entomology and botany to refer to something that has wings or winglike structures.

In entomology

In entomology, "alate" usually refers to the winged form o ...

s) that can disperse to other food sources. The mouthparts or eyes can be small or missing in some species and forms.

Diet

Many aphid species are monophagous (that is, they feed on only one plant species). Others, like the green peach aphid, feed on hundreds of plant species across manyfamilies

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Idea ...

. About 10% of species feed on different plants at different times of the year.

A new host plant is chosen by a winged adult by using visual cues, followed by olfaction using the antennae; if the plant smells right, the next action is probing the surface upon landing. The stylus is inserted and saliva secreted, the sap is sampled, the xylem may be tasted and finally, the phloem is tested. Aphid saliva may inhibit phloem-sealing mechanisms and has pectinases that ease penetration. Non-host plants can be rejected at any stage of the probe, but the transfer of viruses occurs early in the investigation process, at the time of the introduction of the saliva, so non-host plants can become infected.

Aphids usually feed passively on sap

Sap is a fluid transported in xylem cells (vessel elements or tracheids) or phloem sieve tube elements of a plant. These cells transport water and nutrients throughout the plant.

Sap is distinct from latex, resin, or cell sap; it is a separ ...

of phloem

Phloem (, ) is the living tissue in vascular plants that transports the soluble organic compounds made during photosynthesis and known as ''photosynthates'', in particular the sugar sucrose, to the rest of the plant. This transport process is ...

vessels in plants, as do many of other hemipterans such as scale insects and cicadas. Once a phloem vessel is punctured, the sap, which is under pressure, is forced into the aphid's food canal. Occasionally, aphids also ingest xylem

Xylem is one of the two types of transport tissue in vascular plants, the other being phloem. The basic function of xylem is to transport water from roots to stems and leaves, but it also transports nutrients. The word ''xylem'' is derived fr ...

sap, which is a more dilute diet than phloem sap as the concentrations of sugars and amino acids are 1% of those in the phloem. Xylem sap is under negative hydrostatic pressure and requires active sucking, suggesting an important role in aphid physiology. As xylem sap ingestion has been observed following a dehydration period, aphids are thought to consume xylem sap to replenish their water balance; the consumption of the dilute sap of xylem permitting aphids to rehydrate. However, recent data showed aphids consume more xylem sap than expected and they notably do so when they are not dehydrated and when their fecundity decreases. This suggests aphids, and potentially, all the phloem-sap feeding species of the order Hemiptera, consume xylem sap for reasons other than replenishing water balance. Although aphids passively take in phloem sap, which is under pressure, they can also draw fluid at negative or atmospheric pressure using the cibarial-pharyngeal pump mechanism present in their head.

Xylem sap consumption may be related to osmoregulation

Osmoregulation is the active regulation of the osmotic pressure of an organism's body fluids, detected by osmoreceptors, to maintain the homeostasis of the organism's water content; that is, it maintains the fluid balance and the concentration ...

. High osmotic pressure in the stomach, caused by high sucrose concentration, can lead to water transfer from the hemolymph to the stomach, thus resulting in hyperosmotic stress and eventually to the death of the insect. Aphids avoid this fate by osmoregulating through several processes. Sucrose concentration is directly reduced by assimilating sucrose toward metabolism and by synthesizing oligosaccharide

An oligosaccharide (/ˌɑlɪgoʊˈsækəˌɹaɪd/; from the Greek ὀλίγος ''olígos'', "a few", and σάκχαρ ''sácchar'', "sugar") is a saccharide polymer containing a small number (typically two to ten) of monosaccharides (simple sug ...

s from several sucrose molecule

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bio ...

s, thus reducing the solute concentration and consequently the osmotic pressure. Oligosaccharides are then excreted through honeydew, explaining its high sugar concentrations, which can then be used by other animals such as ants. Furthermore, water is transferred from the hindgut

The hindgut (or epigaster) is the posterior (caudal) part of the alimentary canal. In mammals, it includes the distal one third of the transverse colon and the splenic flexure, the descending colon, sigmoid colon and up to the ano-rectal junc ...

, where osmotic pressure has already been reduced, to the stomach to dilute stomach content. Eventually, aphids consume xylem sap to dilute the stomach osmotic pressure. All these processes function synergetically, and enable aphids to feed on high-sucrose-concentration plant sap, as well as to adapt to varying sucrose concentrations.

Plant sap is an unbalanced diet for aphids, as it lacks essential amino acid

An essential amino acid, or indispensable amino acid, is an amino acid that cannot be synthesized from scratch by the organism fast enough to supply its demand, and must therefore come from the diet. Of the 21 amino acids common to all life form ...

s, which aphids, like all animals, cannot synthesise, and possesses a high osmotic pressure

Osmotic pressure is the minimum pressure which needs to be applied to a solution to prevent the inward flow of its pure solvent across a semipermeable membrane.

It is also defined as the measure of the tendency of a solution to take in a pure ...

due to its high sucrose

Sucrose, a disaccharide, is a sugar composed of glucose and fructose subunits. It is produced naturally in plants and is the main constituent of white sugar. It has the molecular formula .

For human consumption, sucrose is extracted and refi ...

concentration. Essential amino acids are provided to aphids by bacterial endosymbionts

An ''endosymbiont'' or ''endobiont'' is any organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism most often, though not always, in a mutualistic relationship.

(The term endosymbiosis is from the Greek: ἔνδον ''endon'' "within" ...

, harboured in special cells, bacteriocyte

A bacteriocyte (Greek for ''bacteria cell''), also known as a mycetocyte, is a specialized adipocyte found primarily in certain insect groups such as aphids, tsetse flies, German cockroaches, weevils. These cells contain endosymbiotic organisms ...

s. These symbionts recycle glutamate, a metabolic waste of their host, into essential amino acids.

Carotenoids and photoheterotrophy

Some species of aphids have acquired the ability to synthesise redcarotenoid

Carotenoids (), also called tetraterpenoids, are yellow, orange, and red organic pigments that are produced by plants and algae, as well as several bacteria, and fungi. Carotenoids give the characteristic color to pumpkins, carrots, parsnips, cor ...

s by horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring ( reproduction). ...

from fungi

A fungus (plural, : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of Eukaryote, eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and Mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified ...

. They are the only animals other than two-spotted spider mites and the oriental hornet with this capability. Using their carotenoids, aphids may well be able to absorb solar energy and convert it to a form that their cells can use, ATP

ATP may refer to:

Companies and organizations

* Association of Tennis Professionals, men's professional tennis governing body

* American Technical Publishers, employee-owned publishing company

* ', a Danish pension

* Armenia Tree Project, non ...

. This is the only known example of photoheterotrophy in animals. The carotene

The term carotene (also carotin, from the Latin ''carota'', "carrot") is used for many related unsaturated hydrocarbon substances having the formula C40Hx, which are synthesized by plants but in general cannot be made by animals (with the exc ...

pigments in aphids form a layer close to the surface of the cuticle, ideally placed to absorb sunlight. The excited carotenoids seem to reduce NAD to NADH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) is a coenzyme central to metabolism. Found in all living cells, NAD is called a dinucleotide because it consists of two nucleotides joined through their phosphate groups. One nucleotide contains an aden ...

which is oxidized in the mitochondria for energy.

Reproduction

The simplest reproductive strategy is for an aphid to have a single host all year round. On this it may alternate between sexual and asexual generations (holocyclic) or alternatively, all young may be produced by

The simplest reproductive strategy is for an aphid to have a single host all year round. On this it may alternate between sexual and asexual generations (holocyclic) or alternatively, all young may be produced by parthenogenesis

Parthenogenesis (; from the Greek grc, παρθένος, translit=parthénos, lit=virgin, label=none + grc, γένεσις, translit=génesis, lit=creation, label=none) is a natural form of asexual reproduction in which growth and developmen ...

, egg

An egg is an organic vessel grown by an animal to carry a possibly fertilized egg cell (a zygote) and to incubate from it an embryo within the egg until the embryo has become an animal fetus that can survive on its own, at which point the a ...

s never being laid (anholocyclic). Some species can have both holocyclic and anholocyclic populations under different circumstances but no known aphid species reproduce solely by sexual means. The alternation of sexual and asexual generations may have evolved repeatedly.

However, aphid reproduction is often more complex than this and involves migration between different host plants. In about 10% of species, there is an alternation between woody (primary hosts) on which the aphids overwinter and herbaceous

Herbaceous plants are vascular plants that have no persistent woody stems above ground. This broad category of plants includes many perennials, and nearly all annuals and biennials.

Definitions of "herb" and "herbaceous"

The fourth edition ...

(secondary) host plants, where they reproduce abundantly in the summer. A few species can produce a soldier caste, other species show extensive polyphenism

A polyphenic trait is a trait for which multiple, discrete phenotypes can arise from a single genotype as a result of differing environmental conditions. It is therefore a special case of phenotypic plasticity.

There are several types of polyphen ...

under different environmental conditions and some can control the sex ratio of their offspring depending on external factors.

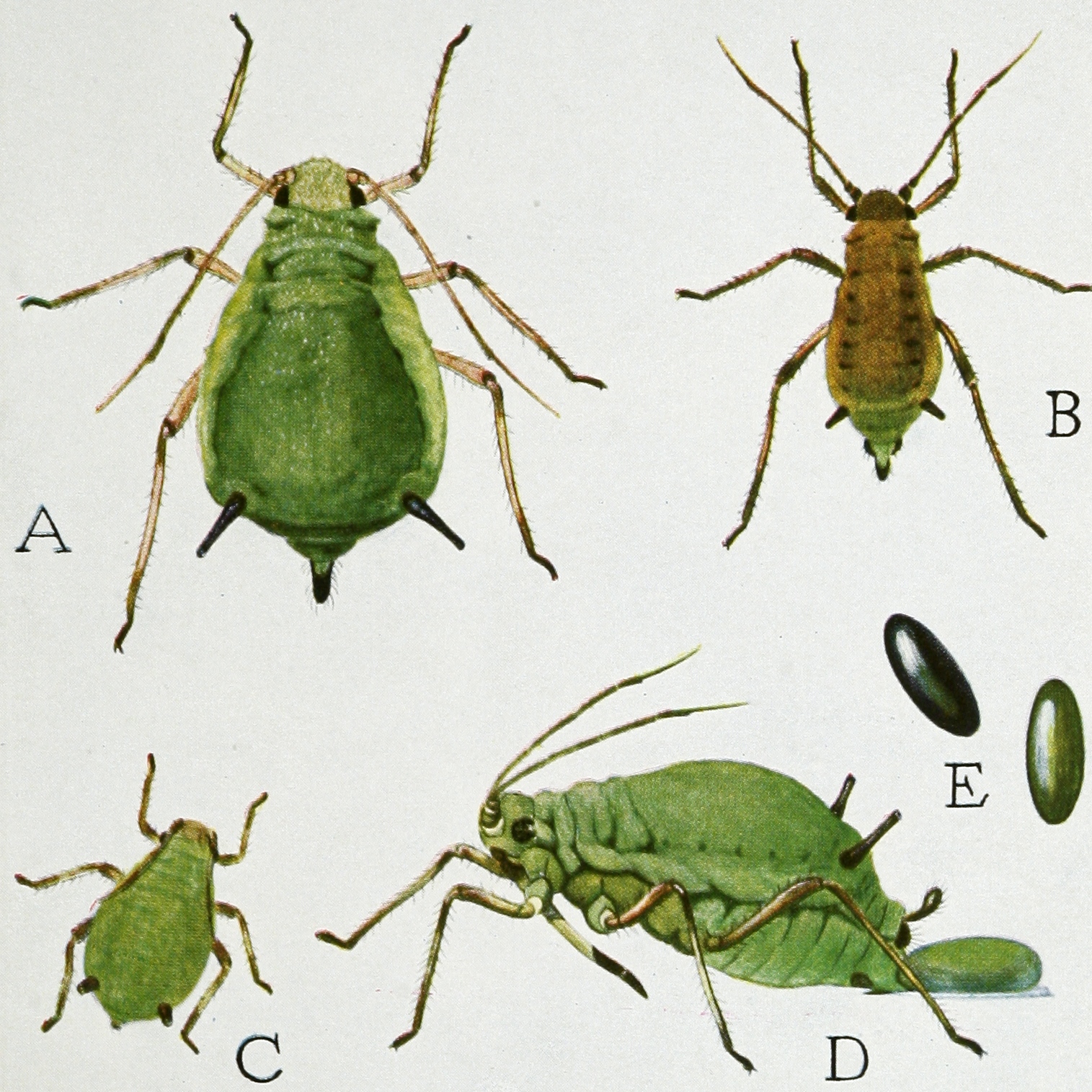

When a typical sophisticated reproductive strategy is used, only females are present in the population at the beginning of the seasonal cycle (although a few species of aphids have been found to have both male and female sexes at this time). The overwintering eggs that hatch in the spring result in females, called fundatrices (stem mothers). Reproduction typically does not involve males (parthenogenesis

Parthenogenesis (; from the Greek grc, παρθένος, translit=parthénos, lit=virgin, label=none + grc, γένεσις, translit=génesis, lit=creation, label=none) is a natural form of asexual reproduction in which growth and developmen ...

) and results in a live birth (viviparity). The live young are produced by pseudoplacental viviparity, which is the development of eggs, deficient in the yolk, the embryos fed by a tissue acting as a placenta. The young emerge from the mother soon after hatching.

Eggs are parthenogenetically produced without meiosis and the offspring are clonal to their mother, so they are all female (thelytoky). The embryos develop within the mothers' ovarioles, which then give birth to live (already hatched) first-instar female nymphs. As the eggs begin to develop immediately after ovulation, an adult female can house developing female nymphs which already have parthenogenetically developing embryos inside them (i.e. they are born pregnant). This telescoping generations, telescoping of generations enables aphids to increase in number with great rapidity. The offspring resemble their parent in every way except size. Thus, a female's diet can affect the body size and birth rate of more than two generations (daughters and granddaughters).

This process repeats itself throughout the summer, producing multiple generations that typically live 20 to 40 days. For example, some species of cabbage aphids (like ''Brevicoryne brassicae'') can produce up to 41 generations of females in a season. Thus, one female hatched in spring can theoretically produce billions of descendants, were they all to survive.

In autumn, aphids reproduce sexually and oviparity, lay eggs. Environmental factors such as a change in photoperiod and temperature, or perhaps a lower food quantity or quality, causes females to parthenogenetically produce sexual females and males. The males are genetically identical to their mothers except that, with the aphids' X0 sex-determination system, they have one fewer sex chromosome. These sexual aphids may lack wings or even mouthparts. Sexual females and males mate, and females lay eggs that develop outside the mother. The eggs survive the winter and hatch into winged (alate) or wingless females the following spring. This occurs in, for example, the Biological life cycle, life cycle of the rose aphid (''Macrosiphum rosae''), which may be considered typical of the family. However, in warm environments, such as in the

In autumn, aphids reproduce sexually and oviparity, lay eggs. Environmental factors such as a change in photoperiod and temperature, or perhaps a lower food quantity or quality, causes females to parthenogenetically produce sexual females and males. The males are genetically identical to their mothers except that, with the aphids' X0 sex-determination system, they have one fewer sex chromosome. These sexual aphids may lack wings or even mouthparts. Sexual females and males mate, and females lay eggs that develop outside the mother. The eggs survive the winter and hatch into winged (alate) or wingless females the following spring. This occurs in, for example, the Biological life cycle, life cycle of the rose aphid (''Macrosiphum rosae''), which may be considered typical of the family. However, in warm environments, such as in the tropics

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the Equator. They are defined in latitude by the Tropic of Cancer in the Northern Hemisphere at N and the Tropic of Capricorn in

the Southern Hemisphere at S. The tropics are also referred ...

or a greenhouse, aphids may go on reproducing asexually for many years.

Aphids reproducing asexually by parthenogenesis

Parthenogenesis (; from the Greek grc, παρθένος, translit=parthénos, lit=virgin, label=none + grc, γένεσις, translit=génesis, lit=creation, label=none) is a natural form of asexual reproduction in which growth and developmen ...

can have genetically identical winged and non-winged female progeny. Control is complex; some aphids alternate during their life-cycles between genetic control (Polymorphism (biology), polymorphism) and environmental control (polyphenism

A polyphenic trait is a trait for which multiple, discrete phenotypes can arise from a single genotype as a result of differing environmental conditions. It is therefore a special case of phenotypic plasticity.

There are several types of polyphen ...

) of production of winged or wingless forms. Winged progeny tend to be produced more abundantly under unfavorable or stressful conditions. Some species produce winged progeny in response to low food quality or quantity. e.g. when a host plant is starting to senesce. The winged females migrate to start new colonies on a new host plant. For example, the apple aphid (''Aphis pomi''), after producing many generations of wingless females gives rise to winged forms that fly to other branches or trees of its typical food plant. Aphids that are attacked by ladybugs, Neuroptera, lacewings, parasitoid wasps, or other predators can change the dynamics of their progeny production. When aphids are attacked by these predators, alarm pheromones, in particular Farnesene, beta-farnesene, are released from the cornicle

The cornicle (or siphuncule) is one of a pair of small upright backward-pointing tubes found on the dorsal side of the 5th or 6th abdominal segments of aphids. They are sometimes mistaken for cerci. They are no more than pores in some species.

...

s. These alarm pheromones cause several behavioral modifications that, depending on the aphid species, can include walking away and dropping off the host plant. Additionally, alarm pheromone perception can induce the aphids to produce winged progeny that can leave the host plant in search of a safer feeding site. Viral infections, which can be extremely harmful to aphids, can also lead to the production of winged offspring. For example, ''Ambidensovirus, Densovirus'' infection has a negative impact on rosy apple aphid (Dysaphis plantaginea

') reproduction, but contributes to the development of aphids with wings, which can transmit the virus more easily to new host plants. Additionally, symbiotic bacteria that live inside of the aphids can also alter aphid reproductive strategies based on the exposure to environmental stressors.

In the autumn, host-alternating (heteroecious) aphid species produce a special winged generation that flies to different host plants for the sexual part of the life cycle. Flightless female and male sexual forms are produced and lay eggs. Some species such as ''Aphis fabae'' (black bean aphid), ''Metopolophium dirhodum'' (rose-grain aphid), ''Myzus persicae'' (peach-potato aphid), and ''Rhopalosiphum padi'' (bird cherry-oat aphid) are serious pests. They overwinter on primary hosts on trees or bushes; in summer, they migrate to their secondary host on a herbaceous plant, often a crop, then the gynoparae return to the tree in autumn. Another example is the soybean aphid (''Aphis glycines''). As fall approaches, the soybean plants begin to senesce from the bottom upwards. The aphids are forced upwards and start to produce winged forms, first females and later males, which fly off to the primary host, buckthorn. Here they mate and overwinter as eggs.

In the autumn, host-alternating (heteroecious) aphid species produce a special winged generation that flies to different host plants for the sexual part of the life cycle. Flightless female and male sexual forms are produced and lay eggs. Some species such as ''Aphis fabae'' (black bean aphid), ''Metopolophium dirhodum'' (rose-grain aphid), ''Myzus persicae'' (peach-potato aphid), and ''Rhopalosiphum padi'' (bird cherry-oat aphid) are serious pests. They overwinter on primary hosts on trees or bushes; in summer, they migrate to their secondary host on a herbaceous plant, often a crop, then the gynoparae return to the tree in autumn. Another example is the soybean aphid (''Aphis glycines''). As fall approaches, the soybean plants begin to senesce from the bottom upwards. The aphids are forced upwards and start to produce winged forms, first females and later males, which fly off to the primary host, buckthorn. Here they mate and overwinter as eggs.

Ecology

Ant mutualism

Some species of

Some species of ant

Ants are eusocial insects of the family Formicidae and, along with the related wasps and bees, belong to the order Hymenoptera. Ants evolved from vespoid wasp ancestors in the Cretaceous period. More than 13,800 of an estimated total of 22,0 ...

s farm aphids, protecting them on the plants where they are feeding, and consuming the honeydew the aphids release from the Rectum, terminations of their Gastrointestinal tract, alimentary canals. This is a Mutualism (biology), mutualistic relationship, with these dairying ants milking the aphids by stroking them with their antenna (biology), antennae. Although mutualistic, the feeding behaviour of aphids is altered by ant attendance. Aphids attended by ants tend to increase the production of honeydew in smaller drops with a greater concentration of amino acids.

Some farming ant species gather and store the aphid eggs in their nests over the winter. In the spring, the ants carry the newly hatched aphids back to the plants. Some species of dairying ants (such as the European yellow meadow ant, ''Lasius flavus'') manage large herds of aphids that feed on roots of plants in the ant colony. Queens leaving to start a new colony take an aphid egg to found a new herd of underground aphids in the new colony. These farming ants protect the aphids by fighting off aphid predators. Some bees in coniferous forests collect aphid honeydew to make Honey#Honeydew honey, forest honey.

Bacterial endosymbiosis

Endosymbiosis with micro-organisms is common in insects, with more than 10% of insect species relying on intracellular bacteria for their development and survival. Aphids harbour a vertically transmitted (from parent to its offspring) obligate symbiosis with ''Buchnera aphidicola'', the primary symbiont, inside specialized cells, the bacteriocytes. Five of the bacteria genes have been transferred to the aphid nucleus. The original association may is estimated to have occurred in a common ancestor and enabled aphids to exploit a new ecological niche, feeding on phloem-sap of vascular plants. ''B. aphidicola'' provides its host with essential amino acids, which are present in low concentrations in plant sap. The metabolites from endosymbionts are also excreted in honeydew. The stable intracellular conditions, as well as the bottleneck effect experienced during the transmission of a few bacteria from the mother to each nymph, increase the probability of transmission of mutations and gene deletions. As a result, the size of the ''B. aphidicola'' genome is greatly reduced, compared to its putative ancestor. Despite the apparent loss of transcription factors in the reduced genome, gene expression is highly regulated, as shown by the ten-fold variation in expression levels between different genes under normal conditions. ''Buchnera aphidicola'' gene transcription, although not well understood, is thought to be regulated by a small number of global transcriptional regulators and/or through nutrient supplies from the aphid host. Some aphid colonies also harbour secondary or facultative (optional extra) bacterial symbionts. These are vertically transmitted, and sometimes also horizontally (from one lineage to another and possibly from one species to another). So far, the role of only some of the secondary symbionts has been described; ''Regiella insecticola'' plays a role in defining the host-plant range, ''Hamiltonella defensa'' provides resistance to parasitoids but only when it is in turn infected by the bacteriophage APSE, and ''Serratia symbiotica'' prevents the deleterious effects of heat.Predators

Aphids are eaten by many bird and insect predators. In a study on a farm in North Carolina, six species of Passerine, passerine bird consumed nearly a million aphids per day between them, the top predators being the American goldfinch, with aphids forming 83% of its diet, and the vesper sparrow. Insects that attack aphids include the adults and larvae of predatory ladybirds,hoverfly

Hover flies, also called flower flies or syrphid flies, make up the insect family Syrphidae. As their common name suggests, they are often seen hovering or nectaring at flowers; the adults of many species feed mainly on nectar and pollen, while ...

larvae, parasitic wasps, aphid midge larvae, "aphid lions" (the larvae of green lacewings), and arachnids such as spiders. Among ladybirds, ''Myzia oblongoguttata'' is a dietary specialist which only feeds on conifer aphids, whereas ''Adalia bipunctata'' and ''Coccinella septempunctata'' are generalists, feeding on large numbers of species. The eggs are laid in batches, each female laying several hundred. Female hoverflies lay several thousand eggs. The adults feed on pollen and nectar but the larvae feed voraciously on aphids; ''Eupeodes corollae'' adjusts the number of eggs laid to the size of the aphid colony.

Aphids are often infected by bacteria, viruses, and fungi. They are affected by the weather, such as precipitation (meteorology), precipitation, temperature and wind. Fungi that attack aphids include ''Neozygites fresenii'', ''Entomophthora'', ''Beauveria bassiana'', ''Metarhizium anisopliae'', and entomopathogenic fungi such as ''Lecanicillium lecanii''. Aphids brush against the microscopic spores. These stick to the aphid, germinate, and penetrate the aphid's skin. The fungus grows in the aphid's hemolymph. After about three days, the aphid dies and the fungus releases more spores into the air. Infected aphids are covered with a woolly mass that progressively grows thicker until the aphid is obscured. Often, the visible fungus is not the one that killed the aphid, but a secondary infection.

Aphids can be easily killed by unfavourable weather, such as late spring freezes. Excessive heat kills the symbiotic bacteria that some aphids depend on, which makes the aphids infertile. Rain prevents winged aphids from dispersing, and knocks aphids off plants and thus kills them from the impact or by starvation, but cannot be relied on for aphid control.

Anti-predator defences

Most aphids have little protection from predators. Some species interact with plant tissues forming a gall, an abnormal swelling of plant tissue. Aphids can live inside the gall, which provides protection from predators and the elements. A number of galling aphid species are known to produce specialised "soldier" forms, sterile nymphs with defensive features which defend the gall from invasion. For example, Alexander's horned aphids are a type of soldier aphid that has a hard exoskeleton and pincer (biology), pincer-like mouthparts. A woolly aphid, ''Colophina clematis'', has first instar "soldier" larvae that protect the aphid colony, killing larvae of ladybirds, hoverflies and the flower bug ''Anthocoris nemoralis'' by climbing on them and inserting their stylets.

Although aphids cannot fly for most of their life cycle, they can escape predators and accidental ingestion by herbivores by dropping off the plant onto the ground. Others species use the soil as a permanent protection, feeding on the vascular systems of roots and remaining underground all their lives. They are often attended by ants, for the honeydew they produce and are carried from plant to plant by the ants through their tunnels.