|

Leachia Dislocata

''Leachia'' is a genus containing eight species of glass squids. The genus was formerly divided into two subgenera: ''Leachia'' and ''Pyrgopsis'', but is no longer. Members of this genus live in tropical and sub-tropical waters worldwide. Description The mantle is up to 20 cm long in the largest species. ''Leachia'' are characterised by the presence of two parallel ridges bearing raised cartilage spikes, which run along the underside of the body near the head. They have large round fins, which often constitute 20–30% of the entire mantle length. Like most glass squids, members of this genus possess a ring of light organs around their eyes. Bioluminescent cells produce light that cancels the shadow cast by their large eyes. Typical of cranchiid squids, juvenile ''Leachia'' species have stalked eyes. As they mature, females develop light organs on the ends of their third arm pairs. These are thought to be used in mating displays to attract males. Species * ''Lea ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Charles Alexandre Lesueur

Charles Alexandre Lesueur (1 January 1778 in Le Havre – 12 December 1846 in Le Havre) was a French naturalist, artist, and explorer. He was a prolific natural-history collector, gathering many type specimens in Australia, Southeast Asia, and North America, and was also responsible for describing numerous species, including the spiny softshell turtle ('' Apalone spinifera''), smooth softshell turtle ('' A. mutica''), and common map turtle ('' Graptemys geographica''). Both Mount Lesueur and Lesueur National Park in Western Australia are named in his honor. Early life Charles Alexandre Lesueur was born on January 1, 1778, to Jean-Baptiste Denis Lesueur and Charlotte Thieullent. Charlotte died when Charles was sixteen years old, and Charles' maternal grandmother took care of him and his siblings. Charles attended the Collège du Havre and possibly the Ecole publique des mathématiques et d'hydrographie. He was in military service in a cadet battalion at age fifteen and ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Alphonse Trémeau De Rochebrune

Alphonse Amédée Trémeau de Rochebrune was a French botanist, malacologist and a zoologist. He was born on 18 September 1836 in Saint-Savin, and died on 23 April 1912 in Paris. Biography The son of a curator of the Museum of Angoulême, he became a military surgeon and reached the rank of adjutant in 1870. After obtaining his doctorate in 1874, he travelled to Saint-Louis in Senegal. In 1878, he joined the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle as an assistant in the Laboratory of Anthropology, and then replaced Victor Bertin (1849–1880), as assistant naturalist in the Laboratory of molluscs, worms and zoophytes, after Bertin's death. He held this post until his retirement in 1911. He addressed, in one hundred fifty publications, to a variety of subjects: from geology to paleontology, botany to malacology. These include his 1860 catalogue of wild flowering plants in the Department of Charente, co-written with Savatier Alexander. From 1882 to 1883, Rochebrune took part in ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Mark Norman (marine Biologist)

Mark Douglas Norman is a marine biologist living in southern Australia, where he works through the University of Melbourne and Museum Victoria. For over a decade, Norman has been working exclusively with cephalopods and he is one of the leading scientists in the field, having discovered over 150 new species of octopuses. The best known of these is probably the mimic octopus The mimic octopus (''Thaumoctopus mimicus'') is a species of octopus from the Indo-Pacific region. Like other octopuses, it uses its chromatophores to disguise itself with its background. However, it is noteworthy for being able to impersonate a .... Mark Norman is the author of ''Cephalopods: A World Guide'', a book published in 2000 containing over 800 colour photographs of cephalopods in their natural habitat. References Australian marine biologists Teuthologists Living people Year of birth missing (living people) {{Biologist-stub ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Cephalopod Limb

All cephalopods possess flexible limbs extending from their heads and surrounding their cephalopod beak, beaks. These appendages, which function as muscular hydrostats, have been variously termed arms, legs or tentacles. Description In the scientific literature, a cephalopod ''arm'' is often treated as distinct from a ''Tentacle#Tentacles in invertebrates, tentacle'', though the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, often with the latter acting as an umbrella term for cephalopod limbs. Generally, arms have suckers along most of their length, as opposed to tentacles, which have suckers only near their ends.Young, R.E., M. Vecchione & K.M. Mangold 1999Cephalopoda Glossary Tree of Life web project. Barring a few exceptions, octopuses have eight arms and no tentacles, while squid and cuttlefish have eight arms (or two "legs" and six "arms") and two tentacles.Norman, M. 2000. ''Cephalopods: A World Guide''. ConchBooks, Hackenheim. p. 15. "There is some confusion around the ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Cranchiid

The family Cranchiidae comprises the approximately 60 species of glass squid, also known as cockatoo squid, cranchiid, cranch squid, or bathyscaphoid squid. Cranchiid squid occur in surface and midwater depths of open oceans around the world. They range in mantle length from to over , in the case of the colossal squid. The common name, glass squid, derives from the transparent nature of most species. Cranchiid squid spend much of their lives in partially sunlit shallow waters, where their transparency provides camouflage. They are characterised by a swollen body and short arms, which bear two rows of suckers or hooks. The third arm pair is often enlarged. Many species are bioluminescent organisms and possess light organs on the undersides of their eyes, used to cancel their shadows. Eye morphology varies widely, ranging from large and circular to telescopic and stalked. A large, fluid-filled chamber containing ammonia solution is used to aid buoyancy. This buoyancy syste ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Bioluminescence

Bioluminescence is the production and emission of light by living organisms. It is a form of chemiluminescence. Bioluminescence occurs widely in marine vertebrates and invertebrates, as well as in some fungi, microorganisms including some bioluminescent bacteria, and terrestrial arthropods such as fireflies. In some animals, the light is bacteriogenic, produced by symbiotic bacteria such as those from the genus '' Vibrio''; in others, it is autogenic, produced by the animals themselves. In a general sense, the principal chemical reaction in bioluminescence involves a light-emitting molecule and an enzyme, generally called luciferin and luciferase, respectively. Because these are generic names, luciferins and luciferases are often distinguished by the species or group, e.g. firefly luciferin. In all characterized cases, the enzyme catalyzes the oxidation of the luciferin. In some species, the luciferase requires other cofactors, such as calcium or magnesium ions, and s ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Photophore

A photophore is a glandular organ that appears as luminous spots on various marine animals, including fish and cephalopods. The organ can be simple, or as complex as the human eye; equipped with lenses, shutters, color filters and reflectors, however unlike an eye it is optimized to produce light, not absorb it. The bioluminescence can variously be produced from compounds during the digestion of prey, from specialized mitochondrial cells in the organism called photocytes ("light producing" cells), or, similarly, associated with symbiotic bacteria in the organism that are cultured. The character of photophores is important in the identification of deep sea fishes. Photophores on fish are used for attracting food or for camouflage from predators by counter-illumination. Photophores are found on some cephalopods including the firefly squid, which can create impressive light displays, as well as numerous other deep sea organisms such as the pocket shark Mollisquama mississipp ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Cephalopod Fin

Cephalopod fins, sometimes known as wings,Young, R.E., M. Vecchione & K.M. Mangold (1999)Cephalopoda Glossary Tree of Life Web Project. are paired flap-like locomotory appendages. They are found in ten-limbed cephalopods (including squid, bobtail squid, cuttlefish, and ''Spirula'') as well as in the eight-limbed cirrate octopuses and vampire squid. Many extinct cephalopod groups also possessed fins. Nautiluses and the more familiar incirrate octopuses lack swimming fins. An extreme development of the cephalopod fin is seen in the bigfin squid of the family Magnapinnidae. Fins project from the mantle and are often positioned dorsally. In most cephalopods, the fins are restricted to the posterior end of the mantle, but in cuttlefish and some squid they span the mantle's entire length. Fin attachment varies greatly among cephalopods, though in all cases it involves specialised fin cartilage (which reaches its greatest development in Octopodiformes). A fin may be attached to ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Cartilage

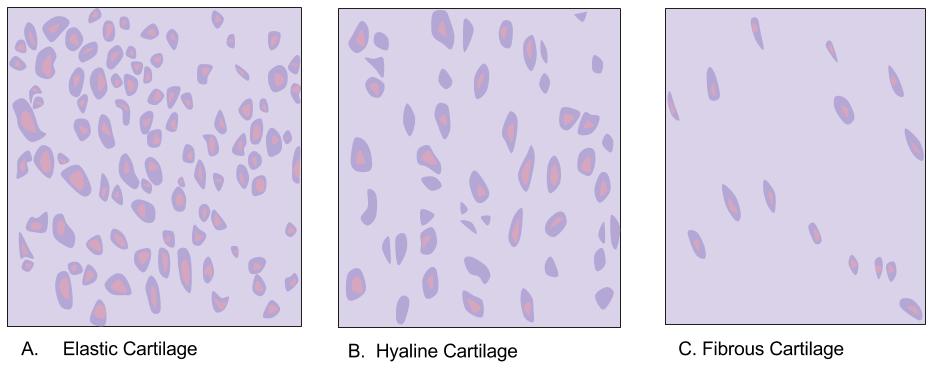

Cartilage is a resilient and smooth type of connective tissue. In tetrapods, it covers and protects the ends of long bones at the joints as articular cartilage, and is a structural component of many body parts including the rib cage, the neck and the bronchial tubes, and the intervertebral discs. In other taxa, such as chondrichthyans, but also in cyclostomes, it may constitute a much greater proportion of the skeleton. It is not as hard and rigid as bone, but it is much stiffer and much less flexible than muscle. The matrix of cartilage is made up of glycosaminoglycans, proteoglycans, collagen fibers and, sometimes, elastin. Because of its rigidity, cartilage often serves the purpose of holding tubes open in the body. Examples include the rings of the trachea, such as the cricoid cartilage and carina. Cartilage is composed of specialized cells called chondrocytes that produce a large amount of collagenous extracellular matrix, abundant ground substance that is rich in p ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Mantle (mollusc)

The mantle (also known by the Latin word pallium meaning mantle, robe or cloak, adjective pallial) is a significant part of the anatomy of molluscs: it is the dorsal body wall which covers the visceral mass and usually protrudes in the form of flaps well beyond the visceral mass itself. In many species of molluscs the epidermis of the mantle secretes calcium carbonate and conchiolin, and creates a shell. In sea slugs there is a progressive loss of the shell and the mantle becomes the dorsal surface of the animal. The words mantle and pallium both originally meant cloak or cape, see mantle (vesture). This anatomical structure in molluscs often resembles a cloak because in many groups the edges of the mantle, usually referred to as the ''mantle margin'', extend far beyond the main part of the body, forming flaps, double-layered structures which have been adapted for many different uses, including for example, the siphon. Mantle cavity The ''mantle cavity'' is a central ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Subgenus

In biology, a subgenus (plural: subgenera) is a taxonomic rank directly below genus. In the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, a subgeneric name can be used independently or included in a species name, in parentheses, placed between the generic name and the specific epithet: e.g. the tiger cowry of the Indo-Pacific, ''Cypraea'' (''Cypraea'') ''tigris'' Linnaeus, which belongs to the subgenus ''Cypraea'' of the genus ''Cypraea''. However, it is not mandatory, or even customary, when giving the name of a species, to include the subgeneric name. In the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICNafp), the subgenus is one of the possible subdivisions of a genus. There is no limit to the number of divisions that are permitted within a genus by adding the prefix "sub-" or in other ways as long as no confusion can result. Article 4 The secondary ranks of section and series are subordinate to subgenus. An example is ''Banksia'' subg. ''Isostyl ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Glass Squid

The family Cranchiidae comprises the approximately 60 species of glass squid, also known as cockatoo squid, cranchiid, cranch squid, or bathyscaphoid squid. Cranchiid squid occur in surface and midwater depths of open oceans around the world. They range in mantle length from to over , in the case of the colossal squid. The common name, glass squid, derives from the transparent nature of most species. Cranchiid squid spend much of their lives in partially sunlit shallow waters, where their transparency provides camouflage. They are characterised by a swollen body and short arms, which bear two rows of suckers or hooks. The third arm pair is often enlarged. Many species are bioluminescent organisms and possess light organs on the undersides of their eyes, used to cancel their shadows. Eye morphology varies widely, ranging from large and circular to telescopic and stalked. A large, fluid-filled chamber containing ammonia solution is used to aid buoyancy. This buoyancy syste ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |