The Underground Railroad was an organized network of secret routes and safe houses used by

freedom seekers

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th centuries to describe people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called fre ...

to escape to the

abolitionist Northern United States and

Eastern Canada

Eastern Canada (, also the Eastern provinces, Canadian East or the East) is generally considered to be the region of Canada south of Hudson Bay/ Hudson Strait and east of Manitoba, consisting of the following provinces (from east to west): Newf ...

. Enslaved Africans and

African Americans

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa ...

escaped from slavery as early as the 16th century and many of their escapes were unaided.

However, a network of safe houses generally known as the Underground Railroad began to organize in the 1780s among

Abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

Societies in the

North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

.

It ran north and grew steadily until the

Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War. The Proclamation had the eff ...

was signed in 1863 by President

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

.

[Vox, Lisa]

"How Did Slaves Resist Slavery?"

, ''African-American History'', About.com. Retrieved July 17, 2011. The escapees sought primarily to escape into

free states, and potentially from there to Canada.

The network, primarily the work of

free

Free may refer to:

Concept

* Freedom, the ability to act or change without constraint or restriction

* Emancipate, attaining civil and political rights or equality

* Free (''gratis''), free of charge

* Gratis versus libre, the difference betw ...

and enslaved African Americans, was assisted by

abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. T ...

and others sympathetic to the cause of the

escapees

Escape or Escaping may refer to:

Arts and media Film

* ''Escape'' (1928 film), a German silent drama film

* ''Escape!'' (film), a 1930 British crime film starring Austin Trevor and Edna Best

* ''Escape'' (1940 film), starring Robert Taylor and ...

. The enslaved people who risked capture and those who aided them are also collectively referred to as the passengers and conductors of the Railroad, respectively.

Various other routes led to Mexico, where slavery had been abolished, and to islands in the

Caribbean

The Caribbean ( , ; ; ; ) is a region in the middle of the Americas centered around the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, mostly overlapping with the West Indies. Bordered by North America to the north, Central America ...

that were not part of the slave trade. An earlier escape route running south toward

Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

, then a

Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many countries in the Americas

**Spanish cuisine

**Spanish history

**Spanish culture

...

possession (except 1763–1783), existed from the late 17th century until approximately 1790. During the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, freedom seekers escaped to Union lines in the South to obtain their freedom. One estimate suggests that by 1850, approximately 100,000 slaves had escaped to freedom via the network.

According to former professor of

Pan-African

Pan-Africanism is a nationalist movement that aims to encourage and strengthen bonds of solidarity between all indigenous peoples and diasporas of African ancestry. Based on a common goal dating back to the Atlantic slave trade, the Trans-Sa ...

studies J. Blaine Hudson, who was dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at the

University of Louisville

The University of Louisville (UofL) is a public university, public research university in Louisville, Kentucky, United States. It is part of the Kentucky state university system. Chartered in 1798 as the Jefferson Seminary, it became in the 19t ...

, by the end of the Civil War, 500,000 or more African Americans self-emancipated from slavery on the Underground Railroad.

Origin of the name

Eric Foner

Eric Foner (; born February 7, 1943) is an American historian. He writes extensively on American political history, the history of freedom, the early history of the Republican Party, African American biography, the American Civil War, Reconstr ...

wrote that the term "was perhaps first used by a Washington newspaper in 1839, quoting a young slave hoping to escape bondage via a railroad that 'went underground all the way to Boston'". Dr. Robert Clemens Smedley wrote that following slave catchers' failed searches and lost traces of fugitives as far north as

Columbia, Pennsylvania

Columbia, formerly Wright's Ferry, is a borough (town) in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, United States. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 10,222. It is southeast of Harrisburg, on the east (left) bank of the Susquehanna River, ...

, they declared in bewilderment that "there must be an underground railroad somewhere," giving origin to the term.

Scott Shane

Scott Shane (born May 22, 1954 in Augusta, Georgia) is an American journalist and author, employed by ''The New York Times'' until 2023, reporting principally about the United States United States Intelligence Community, intelligence community. ...

wrote that the first documented use of the term was in an article written by

Thomas Smallwood

Thomas Smallwood (1801–1883) was a freedman," a daring activist and searing writer" who worked alongside fellow abolitionist Charles Turner Torrey on the Underground Railroad. The two men created what some historians believe was the first branc ...

in the August 10, 1842, edition of ''Tocsin of Liberty'', an abolitionist newspaper published in Albany. He also wrote that the 1879 book ''Sketches in the History of the Underground Railroad'' said the phrase was mentioned in an 1839 Washington newspaper article and that the book's author said 40 years later that he had quoted the article from memory as closely as he could.

Terminology

Members of the Underground Railroad often used specific terms, based on the metaphor of the railway. For example:

* People who helped fugitive slaves find the railroad were "agents"

* Guides were known as "conductors"

* Hiding places were "stations" or "way stations"

* "Station masters" hid escaping slaves in their homes

* People escaping slavery were referred to as "passengers" or "cargo"

* Fugitive slaves would obtain a "ticket"

* Similar to common

gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christianity, Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the second century Anno domino, AD the term (, from which the English word originated as a calque) came to be used also for the books in which the message w ...

lore, the "wheels would keep on turning"

* Financial benefactors of the Railroad were known as "stockholders"

* Promised Land – code word for Canada

* River Jordan – code word for Ohio River

* Heaven – code for freedom or Canada

The

Big Dipper

The Big Dipper (American English, US, Canadian English, Canada) or the Plough (British English, UK, Hiberno-English, Ireland) is an asterism (astronomy), asterism consisting of seven bright stars of the constellation Ursa Major; six of them ar ...

(whose "bowl" points to the

North Star

Polaris is a star in the northern circumpolar constellation of Ursa Minor. It is designated α Ursae Minoris ( Latinized to ''Alpha Ursae Minoris'') and is commonly called the North Star or Pole Star. With an apparent magnitude t ...

) was known as the

drinkin' gourd. The Railroad was often known as the "freedom train" or "Gospel train", which headed towards "Heaven" or "the Promised Land", i.e., Canada.

Political background

For the fugitive slaves who "rode" the Underground Railroad, many of them considered Canada their final destination. An estimated 30,000 to 40,000 of them settled in Canada, half of whom came between 1850 and 1860. Others settled in

free states in the north. Thousands of court cases for escaping fugitive slaves were recorded between the

Revolutionary War and the

Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

. Under the original

Fugitive Slave Act of 1793

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was an Act of the United States Congress to give effect to the Fugitive Slave Clause of the U.S. Constitution ( Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3), which was later superseded by the Thirteenth Amendment, and to al ...

, officials from free states were required to assist slaveholders or their agents who recaptured fugitives, but some state legislatures prohibited this. The law made it easier for slaveholders and slave catchers to capture African Americans and return them to slavery, and in some cases allowed them to enslave free blacks. It also created an eagerness among abolitionists to help enslaved people, resulting in the growth of anti-slavery societies and the Underground Railroad.

With heavy lobbying by Southern politicians, the

Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that temporarily defused tensions between slave and free states during the years leading up to the American Civil War. Designe ...

was passed by

Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

after the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

. It included a more stringent

Fugitive Slave Law

The fugitive slave laws were laws passed by the United States Congress in 1793 and 1850 to provide for the return of slaves who escaped from one state into another state or territory. The idea of the fugitive slave law was derived from the Fugi ...

; ostensibly, the compromise addressed regional problems by compelling officials of free states to assist slave catchers, granting them immunity to operate in free states. Because the law required sparse documentation to claim a person was a fugitive, slave catchers also kidnapped

free blacks, especially children, and sold them into slavery. Southern politicians often exaggerated the number of escaped slaves and often blamed these escapes on Northerners interfering with Southern property rights. The law deprived people suspected of being slaves of the right to defend themselves in court, making it difficult to prove free status. Some Northern states enacted

personal liberty laws

In the context of slavery in the United States, the personal liberty laws were laws passed by several U.S. states in the North to counter the Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Different laws did this in different ways, including allowing jur ...

that made it illegal for public officials to capture or imprison former slaves. The perception that Northern states ignored the fugitive slave laws and regulations was a major justification offered for

secession

Secession is the formal withdrawal of a group from a Polity, political entity. The process begins once a group proclaims an act of secession (such as a declaration of independence). A secession attempt might be violent or peaceful, but the goal i ...

.

Routes and methods of escape

Underground Railroad routes went north to free states and Canada, to the Caribbean, to United States western territories, and to

Indian territories. Some fugitive slaves traveled south into Mexico for their freedom. Many escaped by sea, including

Ona Judge, who had been enslaved by President

George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

. Some historians view the waterways of the South as an important component for freedom seekers to escape as water sources were pathways to freedom. In addition, historians of the Underground Railroad found 200,000 runaway slave advertisements in North American newspapers from the middle of the 1700s until the end of the American Civil War. Freedom seekers in

Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

hid on

steamboat

A steamboat is a boat that is marine propulsion, propelled primarily by marine steam engine, steam power, typically driving propellers or Paddle steamer, paddlewheels. The term ''steamboat'' is used to refer to small steam-powered vessels worki ...

s heading to

Mobile, Alabama

Mobile ( , ) is a city and the county seat of Mobile County, Alabama, United States. The population was 187,041 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. After a successful vote to annex areas west of the city limits in July 2023, Mobil ...

in hopes of blending in among the city's free Black community, and also hid on other steamboats leaving Alabama that were headed further northward into free territories and free states. In 1852, a law was passed by the Alabama legislature to reduce the number of freedom seekers escaping on boats. The law penalized slaveholders and captains of vessels if they allowed enslaved people on board without a pass. Alabama freedom seekers also made canoes to escape. Freedom seekers escaped from their enslavers in

Panama

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in Latin America at the southern end of Central America, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and ...

on boats heading for California by way of the Panama route. Slaveholders used the Panama route to reach California. In Panama slavery was illegal and

Black Panamanians encouraged enslaved people from the United States to escape into the local city of Panama.

Freedom seekers created methods to throw off the

slave catcher

A slave catcher is a person employed to track down and return escaped slaves to their enslavers. The first slave catchers in the Americas were active in European colonies in the West Indies during the sixteenth century. In colonial Virginia a ...

s' bloodhounds from tracking their scent. One method was using a combination of hot pepper, lard, and vinegar on their shoes. In North Carolina freedom seekers put

turpentine

Turpentine (which is also called spirit of turpentine, oil of turpentine, terebenthine, terebenthene, terebinthine and, colloquially, turps) is a fluid obtainable by the distillation of resin harvested from living trees, mainly pines. Principall ...

on their shoes to prevent slave catchers' dogs from tracking their scents, in Texas escapees used paste made from a charred bullfrog. Other runaways escaped into the swamps to wash off their scent.

Most escapes occurred at night when the runaways could hide under the cover of darkness.

Another method freedom seekers used to prevent capture was carrying forged free passes. During slavery, free Blacks showed proof of their freedom by carrying a pass that proved they were free. Free Blacks and enslaved people created forged free passes for freedom seekers as they traveled through slave states.

North to free states and Canada

Structure

Despite the thoroughfare's name, the escape network was neither literally underground nor a railroad. (The first literal underground railroad did not exist

until 1863.) According to

John Rankin, "It was so called because they who took passage on it disappeared from public view as really as if they had gone into the ground. After the fugitive slaves entered a depot on that road no trace of them could be found. They were secretly passed from one depot to another until they arrived at a destination where they were able to remain free." It was known as a railroad, using rail terminology such as stations and conductors, because that was the transportation system in use at the time.

The Underground Railroad did not have a headquarters or governing body, nor were there published guides, maps, pamphlets, or even newspaper articles. It consisted of meeting points, secret routes, transportation, and

safe house

A safe house (also spelled safehouse) is a dwelling place or building whose unassuming appearance makes it an inconspicuous location where one can hide out, take shelter, or conduct clandestine activities.

Historical usage

It may also refer to ...

s, all of them maintained by

abolitionist sympathizers and communicated by

word of mouth

Word of mouth is the passing of information from person to person using oral communication, which could be as simple as telling someone the time of day. Storytelling is a common form of word-of-mouth communication where one person tells others a ...

, although there is also a report of a numeric code used to encrypt messages. Participants generally organized in small, independent groups; this helped to maintain secrecy. People escaping enslavement would move north along the route from one way station to the next. "Conductors" on the railroad came from various backgrounds and included

free-born blacks, white abolitionists, the formerly enslaved (either escaped or

manumitted

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing slaves

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and ...

), and Native Americans. Believing that slavery was "contrary to the ethics of Jesus", Christian congregations and clergy played a role, especially the

Religious Society of Friends

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

(

Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestantism, Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally ...

),

Congregationalists

Congregationalism (also Congregational Churches or Congregationalist Churches) is a Reformed Christian (Calvinist) tradition of Protestant Christianity in which churches practice congregational government. Each congregation independently a ...

,

Wesleyan Methodists The Wesleyan Church is a Methodist Christian denomination aligned with the holiness movement.

Wesleyan Church may also refer to:

* Wesleyan Methodist Church of Australia, the Australian branch of the Wesleyan Church

Denominations

* Allegheny W ...

, and

Reformed Presbyterians, as well as the anti-slavery branches of

mainstream denominations which entered into

schism

A schism ( , , or, less commonly, ) is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization, movement, or religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a split in what had previously been a single religious body, suc ...

over the issue, such as the

Methodist Episcopal Church

The Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) was the oldest and largest Methodist denomination in the United States from its founding in 1784 until 1939. It was also the first religious denomination in the US to organize itself nationally. In 1939, th ...

and the

Baptists

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

. The role of free blacks was crucial; without it, there would have been almost no chance for fugitives from slavery to reach freedom safely. The groups of underground railroad "agents" worked in organizations known as

vigilance committee

A vigilance committee is a group of private citizens who take it upon themselves to administer law and order or exercise power in places where they consider the governmental structures or actions inadequate. Prominent historical examples of vigi ...

s.

Free Black communities in Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and New York helped freedom seekers escape from slavery.

Black Churches were stations on the Underground Railroad, and Black communities in the North hid freedom seekers in their churches and homes. Historian Cheryl Janifer Laroche explained in her book, ''Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad The Geography of Resistance'' that: "Blacks, enslaved and free, operated as the main actors in the central drama that was the Underground Railroad." Laroche further explained how some authors center white abolitionists and white people involved in the antislavery movement as the main factors for freedom seekers escapes and overlook the important role of free Black communities. In addition, author Diane Miller states: "Traditionally, historians have overlooked the agency of African Americans in their own quest for freedom by portraying the Underground Railroad as an organized effort by white religious groups, often Quakers, to aid 'helpless' slaves." Historian Larry Gara argues that many of the stories of the Underground Railroad belong in folklore and not history. The actions of real historical figures such as Harriet Tubman,

Thomas Garrett

Thomas Garrett (August 21, 1789 – January 25, 1871) was an American abolitionist and assisted in the Underground Railroad movement before the American Civil War. He helped more than 2,500 African Americans escape slavery.

For his effort ...

, and Levi Coffin are exaggerated, and Northern abolitionists who guided the enslaved to Canada are hailed as the heroes of the Underground Railroad. This narrative minimizes the intelligence and agency of enslaved Black people who liberated themselves, and implies that freedom seekers needed the help of Northerners to escape.

Geography

The Underground Railroad benefited greatly from the geography of the U.S.–Canada border: Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania and most of New York were separated from Canada by water, over which transport was usually easy to arrange and relatively safe. The main route for freedom seekers from the South led up the Appalachians, Harriet Tubman going via

Harpers Ferry

Harpers Ferry is a historic town in Jefferson County, West Virginia, United States. The population was 269 at the 2020 United States census. Situated at the confluence of the Potomac River, Potomac and Shenandoah River, Shenandoah Rivers in the ...

, through the highly anti-slavery

Western Reserve

The Connecticut Western Reserve was a portion of land claimed by the Colony of Connecticut and later by the state of Connecticut in what is now mostly the northeastern region of Ohio. Warren, Ohio was the Historic Capital in Trumbull County. T ...

region of northeastern Ohio to the vast shore of Lake Erie, and then to Canada by boat. A smaller number, traveling by way of New York or New England, went via

Syracuse

Syracuse most commonly refers to:

* Syracuse, Sicily, Italy; in the province of Syracuse

* Syracuse, New York, USA; in the Syracuse metropolitan area

Syracuse may also refer to:

Places

* Syracuse railway station (disambiguation)

Italy

* Provi ...

(home of

Samuel May

Samuel Joseph May (September 12, 1797 – July 1, 1871) was an American reformer during the nineteenth century who championed education, women's rights, and abolition of slavery. May argued on behalf of all working people that the rights of ...

) and

Rochester, New York

Rochester is a city in and the county seat, seat of government of Monroe County, New York, United States. It is the List of municipalities in New York, fourth-most populous city and 10th most-populated municipality in New York, with a populati ...

(home of

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 14, 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He was the most impor ...

), crossing the

Niagara River

The Niagara River ( ) flows north from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario, forming part of the border between Ontario, Canada, to the west, and New York, United States, to the east. The origin of the river's name is debated. Iroquoian scholar Bruce T ...

or

Lake Ontario

Lake Ontario is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is bounded on the north, west, and southwest by the Canadian province of Ontario, and on the south and east by the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. The Canada–United Sta ...

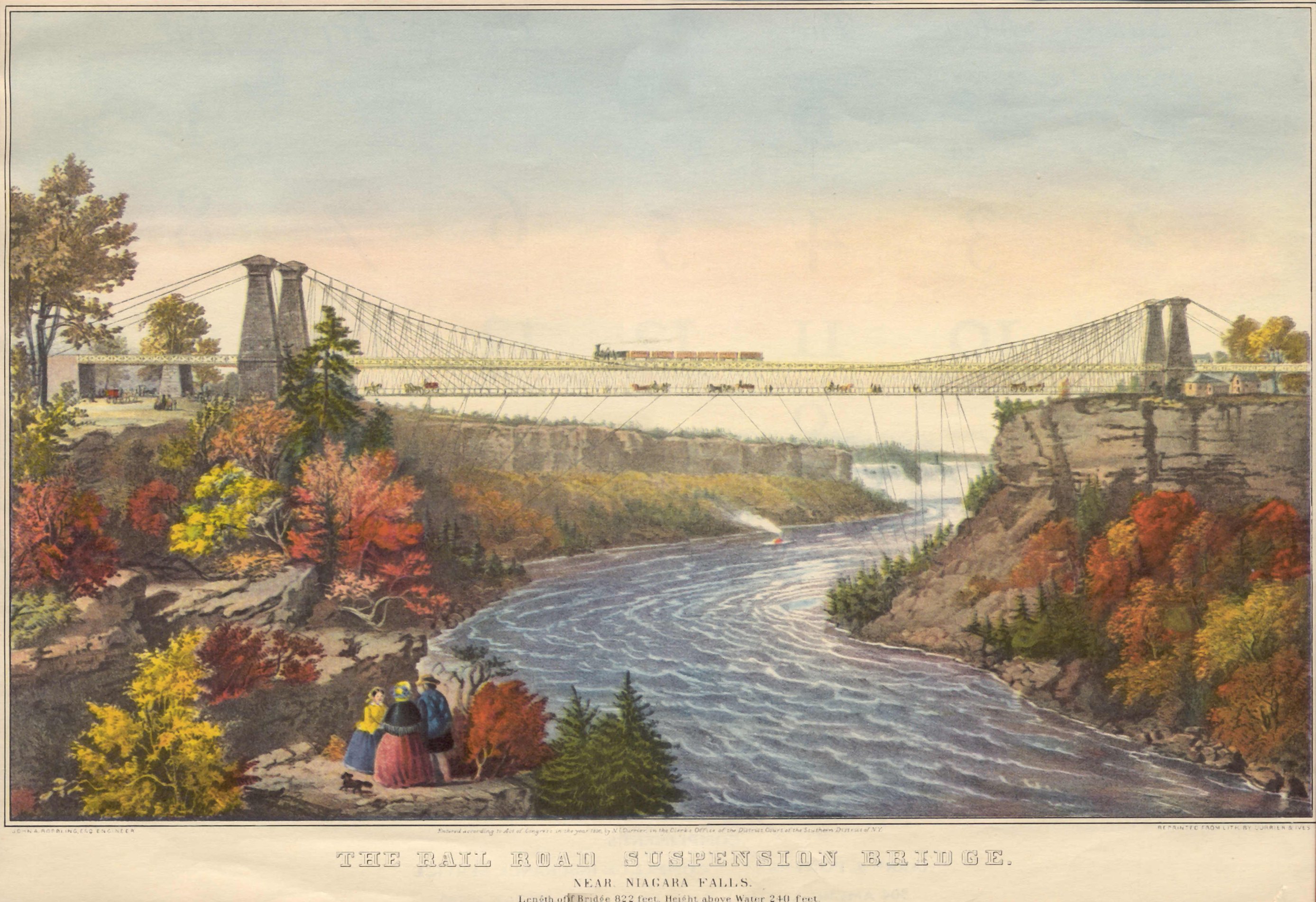

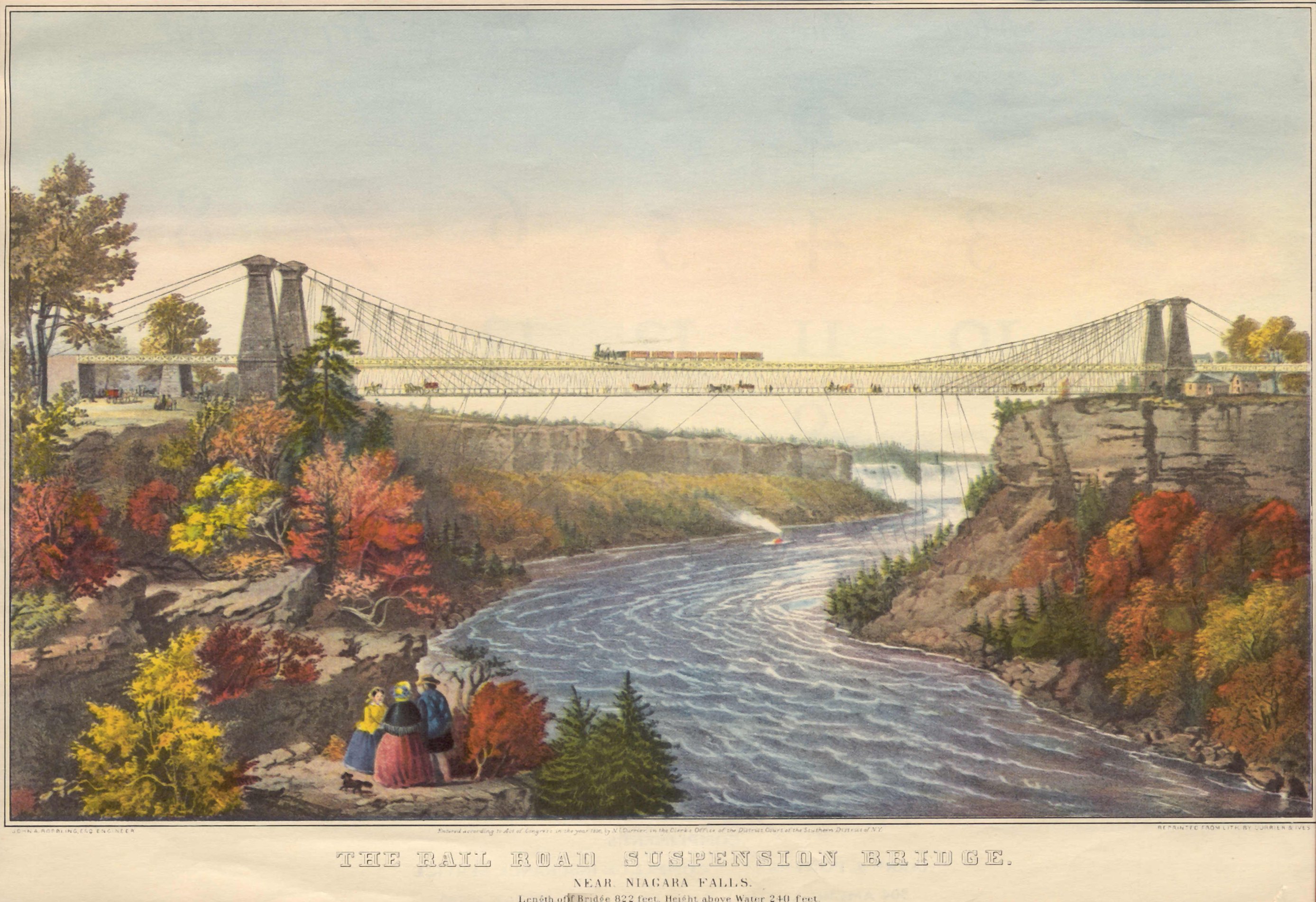

into Canada. By 1848 the

Niagara Falls Suspension Bridge

The Niagara Falls Suspension Bridge stood from 1855 to 1897 across the Niagara River and was the world's first working railway suspension bridge. It spanned and stood downstream of Niagara Falls, where it connected Niagara Falls, Ontario to ...

had been built—it crossed the Niagara River and connected New York to Canada. Enslaved runaways used the bridge to escape their bondage, and Harriet Tubman used the bridge to take freedom seekers into Canada. Those traveling via the New York

Adirondacks

The Adirondack Mountains ( ) are a massif of mountains in Northeastern New York (state), New York which form a circular dome approximately wide and covering about . The region contains more than 100 peaks, including Mount Marcy, which is the hi ...

, sometimes via Black communities like

Timbuctoo, New York

Timbuctoo, New York, was a mid-19th century farming community of African-American homesteaders in the remote town of North Elba, New York. It was located in the vicinity of , near today's Lake Placid village (which did not exist then), in the ...

, entered Canada via

Ogdensburg, on the

St. Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (, ) is a large international river in the middle latitudes of North America connecting the Great Lakes to the North Atlantic Ocean. Its waters flow in a northeasterly direction from Lake Ontario to the Gulf of St. Lawren ...

, or on

Lake Champlain

Lake Champlain ( ; , ) is a natural freshwater lake in North America. It mostly lies between the U.S. states of New York (state), New York and Vermont, but also extends north into the Canadian province of Quebec.

The cities of Burlington, Ve ...

(

Joshua Young

Joshua Young (September 23, 1823 – February 7, 1904) was an abolitionist Congregational Unitarian minister who crossed paths with many famous people of the mid-19th century. He received national publicity and lost his pulpit for presiding in 1 ...

assisted). The western route, used by

John Brown John Brown most often refers to:

*John Brown (abolitionist) (1800–1859), American who led an anti-slavery raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in 1859

John Brown or Johnny Brown may also refer to:

Academia

* John Brown (educator) (1763–1842), Ir ...

among others, led from Missouri west to free Kansas and north to free Iowa, then east via Chicago to the

Detroit River

The Detroit River is an List of international river borders, international river in North America. The river, which forms part of the border between the U.S. state of Michigan and the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Ont ...

.

Thomas Downing was a free Black man in New York and operated his Oyster restaurant as a stop on the Underground Railroad.

Freedom seekers

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th centuries to describe people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called fre ...

(runaway slaves) escaping slavery and seeking freedom hid in the basement of Downing's restaurant. Enslaved people helped freedom seekers escape from slavery. Arnold Gragstone was enslaved and helped runaways escape from slavery by guiding them across the

Ohio River

The Ohio River () is a river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing in a southwesterly direction from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to its river mouth, mouth on the Mississippi Riv ...

for their freedom.

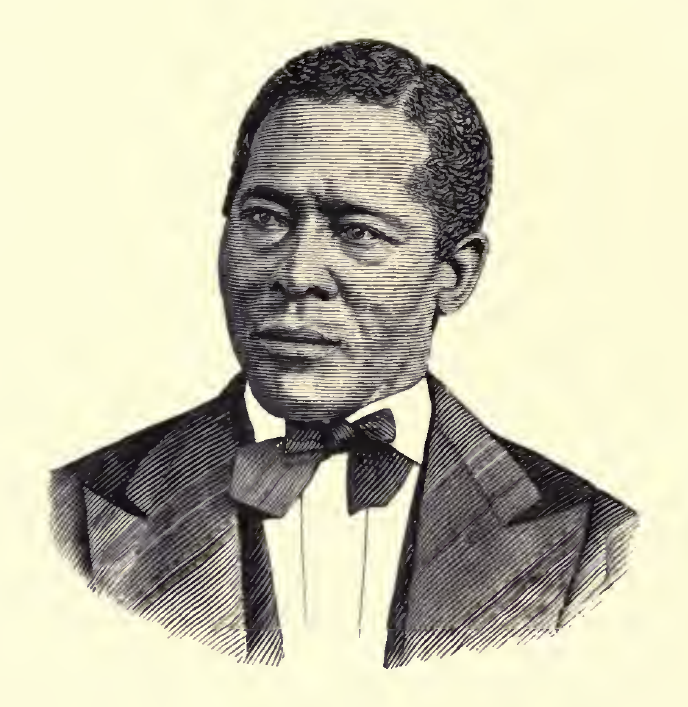

William Still

William Still (October 7, 1819 – July 14, 1902) was an African-American abolitionist based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He was a conductor of the Underground Railroad and was responsible for aiding and assisting at least 649 slaves to freedom ...

, sometimes called "The Father of the Underground Railroad", helped hundreds of slaves escape (as many as 60 a month), sometimes hiding them in his

Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

home. He kept careful records, including short biographies of the people, that contained frequent railway metaphors. He maintained correspondence with many of them, often acting as a middleman in communications between people who had escaped slavery and those left behind. He later published these accounts in the book ''The Underground Railroad: Authentic Narratives and First-Hand Accounts'' (1872), a valuable resource for historians to understand how the system worked and learn about individual ingenuity in escapes.

According to Still, messages were often encoded so that they could be understood only by those active in the railroad. For example, the following message, "I have sent via at two o'clock four large hams and two small hams", indicated that four adults and two children were sent by train from

Harrisburg

Harrisburg ( ; ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), U.S. commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the county seat, seat of Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, Dauphin County. With a population of 50, ...

to Philadelphia. The additional word ''via'' indicated that the "passengers" were not sent on the usual train, but rather via

Reading, Pennsylvania

Reading ( ; ) is a city in Berks County, Pennsylvania, United States, and its county seat. The city had a population of 95,112 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census and is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, fourth-most populous ...

. In this case, the authorities were tricked into going to the regular location (station) in an attempt to intercept the runaways, while Still met them at the correct station and guided them to safety. They eventually escaped either further north or to Canada, where slavery had been

abolished during the 1830s.

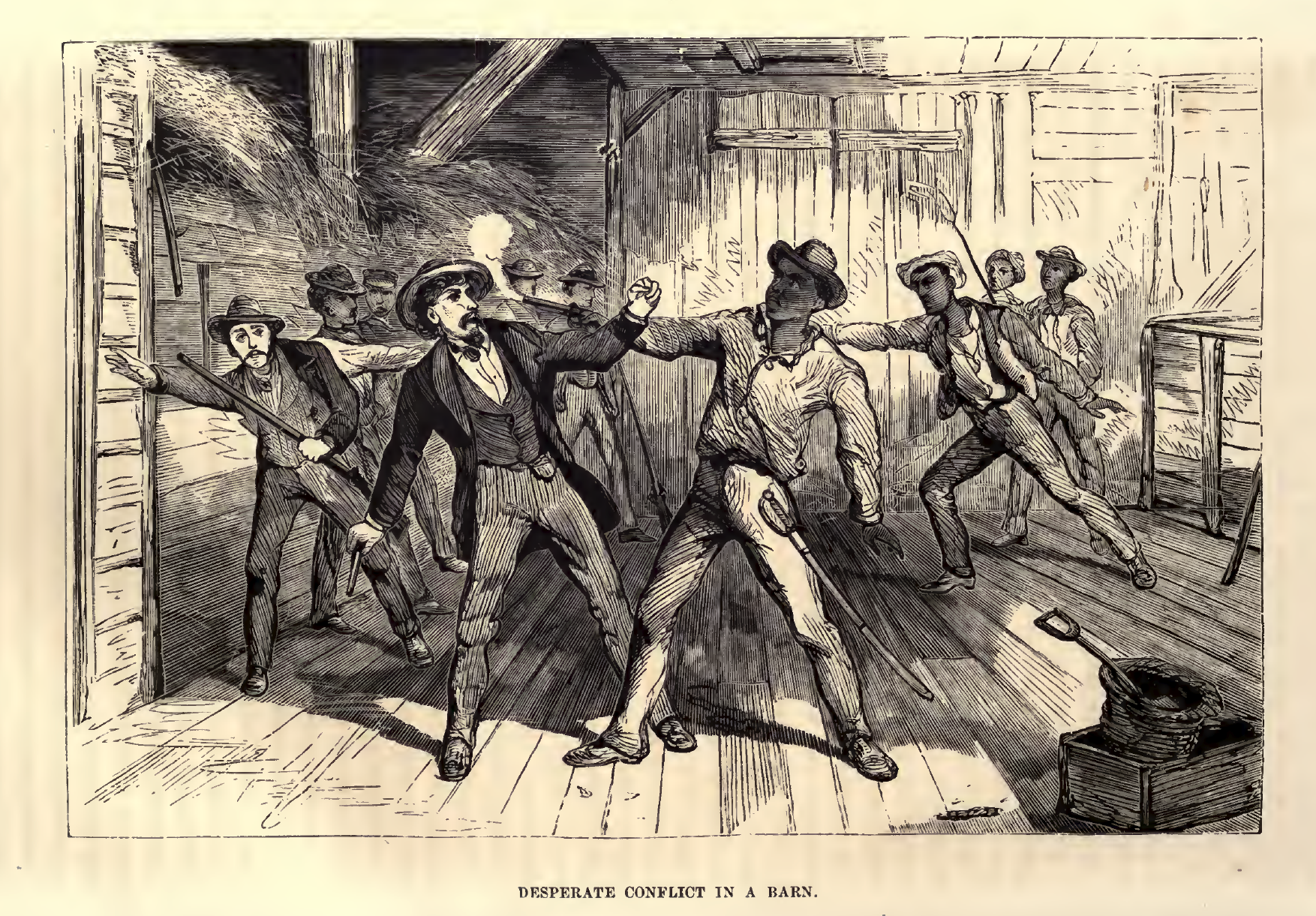

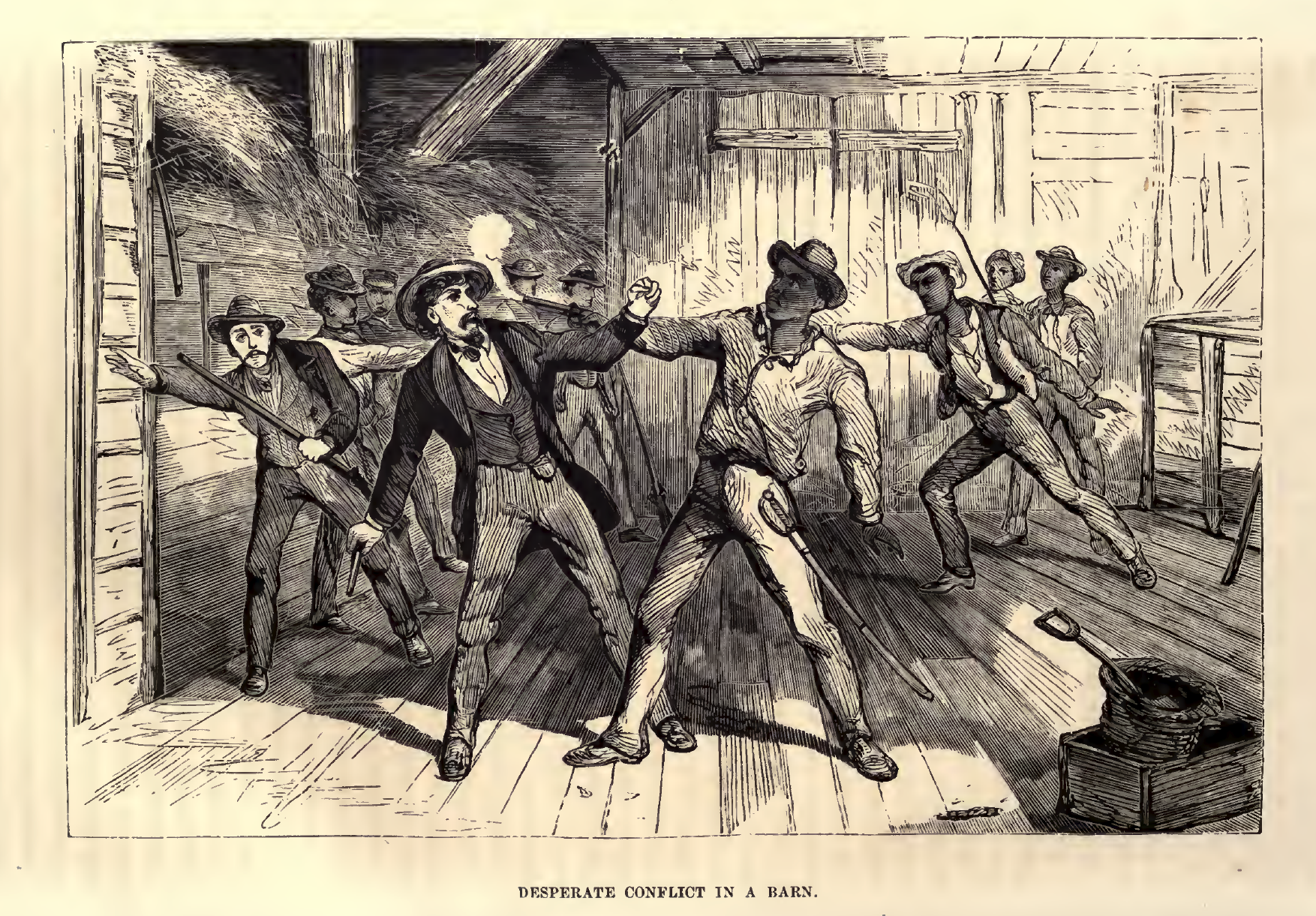

To reduce the risk of infiltration, many people associated with the Underground Railroad

knew only their part of the operation and not of the whole scheme. "Conductors" led or transported the "passengers" from station to station. A conductor sometimes pretended to be enslaved to enter a

plantation

Plantations are farms specializing in cash crops, usually mainly planting a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Plantations, centered on a plantation house, grow crops including cotton, cannabis, tob ...

. Once a part of a plantation, the conductor would direct the runaways to the North. Enslaved people traveled at night, about to each station. They rested, and then a message was sent to the next station to let the station master know the escapees were on their way. They would stop at the so-called "stations" or "depots" during the day and rest. The stations were often located in basements, barns, churches, or in hiding places in caves.

The resting spots where the freedom seekers could sleep and eat were given the code names "stations" and "depots", which were held by "station masters". "Stockholders" gave money or supplies for assistance. Using biblical references, fugitives referred to Canada as the "

Promised Land

In the Abrahamic religions, the "Promised Land" ( ) refers to a swath of territory in the Levant that was bestowed upon Abraham and his descendants by God in Abrahamic religions, God. In the context of the Bible, these descendants are originally ...

" or "Heaven" and the

Ohio River

The Ohio River () is a river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing in a southwesterly direction from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to its river mouth, mouth on the Mississippi Riv ...

, which marked the boundary between

slave states and free states

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were prohibited. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave ...

, as the "

River Jordan

The Jordan River or River Jordan (, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn''; , ''Nəhar hayYardēn''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Sharieat'' (), is a endorheic basin, endorheic river in the Levant that flows roughly north to south through the Sea of Galilee and d ...

".

Traveling conditions

Although the freedom seekers sometimes traveled on boat or train, they usually traveled on foot or by wagon, sometimes lying down, covered with hay or similar products, in groups of one to three escapees. Some groups were considerably larger. Abolitionist

Charles Turner Torrey

Charles Turner Torrey (November 21, 1813 – May 9, 1846) was a leading American Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist. Although largely lost to historians until recently, Torrey pushed the abolitionist movement to more political and ...

and his colleagues rented horses and wagons and often transported as many as 15 or 20 people at a time. Free and enslaved black men occupied as mariners (sailors) helped enslaved people escape from slavery by providing a ride on their ship, providing information on the safest and best escape routes, and safe locations on land, and locations of trusted people for assistance. Enslaved African-American mariners had information about slave revolts occurring in the Caribbean, and relayed this news to enslaved people they had contact with in American ports. Free and enslaved African-American mariners assisted

Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman (born Araminta Ross, – March 10, 1913) was an American abolitionist and social activist. After escaping slavery, Tubman made some 13 missions to rescue approximately 70 enslaved people, including her family and friends, us ...

in her rescue missions. Black mariners provided to her information about the best escape routes and helped her on her rescue missions. In

New Bedford, Massachusetts

New Bedford is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States. It is located on the Acushnet River in what is known as the South Coast region. At the 2020 census, New Bedford had a population of 101,079, making it the state's ninth-l ...

, freedom seekers stowed away on ships leaving the docks with the assistance of Black and white crewmembers and hid in the ships' cargoes during their journey to freedom.

Enslaved people living near rivers escaped on boats and canoes. In 1855,

Mary Meachum

John Berry Meachum (May 3, 1789 – February 26, 1854) was an American pastor, businessman, educator and founder of the First African Baptist Church in St. Louis, the oldest black church west of the Mississippi River. At a time when it was illeg ...

, a free Black woman, attempted to help eight or nine slaves escape from slavery on the

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

near St. Louis, Missouri to the free state of Illinois. To assist with the escape were white antislavery activists and an African American guide from Illinois named "Freeman." However, the escape was not successful because word of the escape reached police agents and slave catchers who waited across the river on the Illinois shore. Breckenridge, Burrows and Meachum were arrested. Prior to this escape attempt, Mary Meachum and her husband John, a former slave, were agents on the Underground Railroad and helped other slaves escape from slavery crossing the Mississippi River.

Routes were often purposely indirect to confuse pursuers. Most escapes were by individuals or small groups; occasionally, there were mass escapes, such as with the

''Pearl'' incident. The journey was often considered particularly difficult and dangerous for women or children. Children were sometimes hard to keep quiet or were unable to keep up with a group. In addition, enslaved women were rarely allowed to leave the plantation, making it harder for them to escape in the same ways that men could. Although escaping was harder for women, some women were successful. One of the most famous and successful conductors (people who secretly traveled into slave states to rescue those seeking freedom) was

Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman (born Araminta Ross, – March 10, 1913) was an American abolitionist and social activist. After escaping slavery, Tubman made some 13 missions to rescue approximately 70 enslaved people, including her family and friends, us ...

, a woman who escaped slavery.

Due to the risk of discovery, information about routes and safe havens was passed along by word of mouth, although in 1896 there is a reference to a numerical code used to encrypt messages. Southern newspapers of the day were often filled with pages of notices soliciting information about fugitive slaves and offering sizable rewards for their capture and return.

Federal marshals and professional

bounty hunter

A bounty hunter is a private agent working for a bail bondsman who captures fugitives or criminals for a commission or bounty. The occupation, officially known as a bail enforcement agent or fugitive recovery agent, has traditionally operated ...

s known as

slave catcher

A slave catcher is a person employed to track down and return escaped slaves to their enslavers. The first slave catchers in the Americas were active in European colonies in the West Indies during the sixteenth century. In colonial Virginia a ...

s pursued freedom seekers as far as the

Canada–U.S. border.

Freedom seekers

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th centuries to describe people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called fre ...

(runaway slaves) foraged, fished, and hunted for food on their journey to freedom on the Underground Railroad. With these ingredients, they prepared one-pot meals (stews), a West African cooking method. Enslaved and free Black people left food outside their front doors to provide nourishment to the freedom seekers. The meals created on the Underground Railroad became a part of the foodways of Black Americans called

soul food

Soul food is the ethnic cuisine of African Americans. Originating in the Southern United States, American South from the cuisines of Slavery in the United States, enslaved Africans transported from Africa through the Atlantic slave trade, sou ...

.

Maroons

The majority of

freedom seekers

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th centuries to describe people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called fre ...

that escaped from slavery did not have help from an abolitionist. Although there are stories of black and white abolitionists helping freedom seekers escape from slavery, many escapes were unaided.

Other Underground Railroad escape routes for freedom seekers were

maroon communities

Maroons are descendants of Africans in the Americas and islands of the Indian Ocean who escaped from slavery, through flight or manumission, and formed their own settlements. They often mixed with Indigenous peoples, eventually evolving into ...

. Maroon communities were hidden places, such as wetlands or marshes, where escaped slaves established their own independent communities. Examples of maroon communities in the United States include the

Black Seminole

The Black Seminoles, or Afro-Seminoles, are an ethnic group of mixed Native American and African origin associated with the Seminole people in Florida and Oklahoma. They are mostly blood descendants of the Seminole people, free Africans, and e ...

communities in Florida, as well as groups that lived in the

Great Dismal Swamp

The Great Dismal Swamp is a large swamp in the Coastal Plain Region of southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina in the eastern United States, between Norfolk, Virginia, and Elizabeth City, North Carolina. It is located in parts of t ...

in Virginia and in the

Okefenokee swamp

The Okefenokee Swamp is a shallow, 438,000-acre (177,000 ha), peat-filled wetland straddling the Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia–Florida line in the United States. A majority of the swamp is protected by the Okefenokee National Wildlife Ref ...

of Georgia and Florida, among others.

In the 1780s, Louisiana had a maroon community in the

bayou

In usage in the Southern United States, a bayou () is a body of water typically found in a flat, low-lying area. It may refer to an extremely slow-moving stream, river (often with a poorly defined shoreline), marshy lake, wetland, or creek. They ...

s of

Saint Malo

Saint-Malo (, , ; Gallo: ; ) is a historic French port in Ille-et-Vilaine, Brittany.

The walled city on the English Channel coast had a long history of piracy, earning much wealth from local extortion and overseas adventures. In 1944, the All ...

. The leader of the Saint Malo maroon community was

Jean Saint Malo

Jean Saint Malo in French (died June 19, 1784), also known as Juan San Maló in Spanish, was the leader of a group of runaway enslaved Africans, known as Maroons, in Spanish Louisiana.

Saint Malo and his band escaped to a marshy area near Lake ...

, a freedom seeker who escaped to live among other runaways in the swamps and bayous of Saint Malo. The population of maroons was fifty and the Spanish colonial government broke up the community and on June 19, 1784, Jean Saint Malo was executed. Colonial

South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

had a number of maroon settlements in its marshland regions in the

Lowcountry

The Lowcountry (sometimes Low Country or just low country) is a geographic and cultural region along South Carolina's coast, including the Sea Islands. The region includes significant salt marshes and other coastal waterways, making it an impor ...

and near rivers. Maroons in South Carolina fought to maintain their freedom and prevent enslavement in

Ashepoo in 1816,

Williamsburg County

Williamsburg County is a county located in the U.S. state of South Carolina. As of the 2020 census its population was 31,026. The county seat and largest community is Kingstree. After a previous incarnation of Williamsburg County, the current ...

in 1819,

Georgetown in 1820, Jacksonborough in 1822, and near Marion in 1861. Historian

Herbert Aptheker

Herbert Aptheker (July 31, 1915 – March 17, 2003) was an American Marxist historian and political activist. He wrote more than 50 books, mostly in the fields of African-American history and general U.S. history, most notably, ''American Negro ...

found evidence that fifty maroon communities existed in the United States between 1672 and 1864. The history of maroons showed how the enslaved resisted enslavement by living in free independent settlements. Historical archeologist Dan Sayer says that historians downplay the importance of maroon settlements and place valor in white involvement in the Underground Railroad, which he argues shows a racial bias, indicating a "...reluctance to acknowledge the strength of black resistance and initiative."

Freedom routes into Native American lands

From colonial America into the 19th century,

Indigenous peoples

There is no generally accepted definition of Indigenous peoples, although in the 21st century the focus has been on self-identification, cultural difference from other groups in a state, a special relationship with their traditional territ ...

of North America assisted and protected enslaved Africans journey to freedom.

However, not all Indigenous communities were accepting of freedom seekers, some of whom they enslaved themselves or returned to their former enslavers.

The earliest accounts of escape are from the 16th century. In 1526, Spaniards established the first European colony in the continental United States in South Carolina called

San Miguel de Gualdape

San Miguel de Gualdape (sometimes San Miguel de Guadalupe) was a short-lived Spanish colony founded in 1526 by Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón. It was established somewhere on the coast of present-day Georgetown, South Carolina, but the exact locati ...

. The enslaved Africans revolted and historians suggest they escaped to

Shakori

The Shakori were an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands. They were thought to be a Siouan people, closely allied with other nearby tribes such as the Eno and the Sissipahaw. As their name is also recorded as Shaccoree, they may be ...

Indigenous communities.

As early as 1689,

enslaved Africans

Slavery has historically been widespread in Africa. Systems of servitude and slavery were once commonplace in parts of Africa, as they were in much of the rest of the Ancient history, ancient and Post-classical history, medieval world. When t ...

fled from the

South Carolina Lowcountry

The Lowcountry (sometimes Low Country or just low country) is a geographic and cultural region along South Carolina's coast, including the Sea Islands. The region includes significant salt marshes and other coastal waterways, making it an impor ...

to

Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida () was the first major European land-claim and attempted settlement-area in northern America during the European Age of Discovery. ''La Florida'' formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba in the Viceroyalty of New Spain, and th ...

seeking freedom.

[

] The

Seminole Nation

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, an ...

accepted

Gullah

The Gullah () are a subgroup of the African Americans, African American ethnic group, who predominantly live in the South Carolina Lowcountry, Lowcountry region of the U.S. states of North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida within ...

runaways (today called

Black Seminoles

The Black Seminoles, or Afro-Seminoles, are an ethnic group of mixed Native Americans in the United States, Native American and African American, African origin associated with the Seminole people in Florida and Oklahoma. They are mostly blood de ...

) into their lands. This was a southern route on the Underground Railroad into Seminole Indian lands that went from Georgia and the Carolinas into Florida. In Northwest Ohio in the 18th and 19th centuries, three

Indigenous/Native American nations, the

Shawnee

The Shawnee ( ) are a Native American people of the Northeastern Woodlands. Their language, Shawnee, is an Algonquian language.

Their precontact homeland was likely centered in southern Ohio. In the 17th century, they dispersed through Ohi ...

, Ottawa, and

Wyandot

Wyandot may refer to:

Native American ethnography

* Wyandot people, who have been called Wyandotte, Huron, Wendat and Quendat

* Wyandot language, an Iroquoian language

* Wyandot Nation of Kansas, an unrecognized tribe and nonprofit organization ...

assisted freedom seekers escape from slavery. The Ottawa people accepted and protected runaways in their villages. Other escapees were taken to

Fort Malden

Fort Malden, formally known as Fort Amherstburg, is a defence fortification located in Amherstburg, Ontario. It was built in 1795 by Great Britain in order to ensure the security of British North America against any potential threat of Americ ...

by the Ottawa. In

Upper Sandusky, Wyandot people allowed a

maroon community of freedom seekers in their lands called Negro Town for four decades.

In the 18th and 19th centuries in areas around the

Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula, including parts of the Ea ...

and

Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic states, South Atlantic regions of the United States. It borders Maryland to its south and west, Pennsylvania to its north, New Jersey ...

,

Nanticoke people

The Nanticoke people are a Native American Algonquian-speaking people, whose traditional homelands are in Chesapeake Bay area, including Delaware. Today they continue to live in the Northeastern United States, especially Delaware, and in Okl ...

hid freedom seekers in their villages. The Nanticoke people lived in small villages near the

Pocomoke River

The Pocomoke River stretches approximately U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed April 1, 2011 from southern Delaware through southeastern Maryland in the United States. At i ...

; the river rises in several forks in the

Great Cypress Swamp

The Great Cypress Swamp (also known as ''Burnt Swamp'', ''Great Pocomoke Swamp'', ''Cypress Swamp'', or ''Big Cypress Swamp''), is a forested freshwater swamp located on the Delmarva Peninsula in south Delaware and southeastern Maryland, United St ...

in southern

Sussex County, Delaware

Sussex County is a county in the southern part of the U.S. state of Delaware, on the Delmarva Peninsula. As of the 2020 census, the population was 237,378, making it the state's second most populated county behind New Castle and ahead of Ke ...

. African Americans escaping slavery were able to hide in swamps, and the water washed off the scent of enslaved runaways, making it difficult for dogs to track their scent. As early as the 18th century, mixed-blood communities formed.

In

Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

, freedom seekers escaped to Shawnee villages located along the

Potomac River

The Potomac River () is in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States and flows from the Potomac Highlands in West Virginia to Chesapeake Bay in Maryland. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography D ...

. Slaveholders in Virginia and Maryland filed numerous complaints and court petitions against the Shawnee and Nanticoke for hiding freedom seekers in their villages.

Odawa

The Odawa (also Ottawa or Odaawaa ) are an Indigenous North American people who primarily inhabit land in the Eastern Woodlands region, now in jurisdictions of the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada. Their territory long prec ...

people also accepted freedom seekers into their villages. The Odawa transferred the runaways to the

Ojibwe

The Ojibwe (; Ojibwe writing systems#Ojibwe syllabics, syll.: ᐅᒋᐺ; plural: ''Ojibweg'' ᐅᒋᐺᒃ) are an Anishinaabe people whose homeland (''Ojibwewaki'' ᐅᒋᐺᐘᑭ) covers much of the Great Lakes region and the Great Plains, n ...

who escorted them to Canada.

Some enslaved people who escaped slavery and fled to Native American villages stayed in their communities. White pioneers who traveled to Kentucky and the

Ohio Territory saw "

Black Shawnees" living with Indigenous people in the

trans-Appalachian west. During the colonial era in

New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

and in the

Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, ...

Nation in Florida, African Americans and Indigenous marriages occurred.

South to Florida and Mexico

Background

Beginning in the 16th century, Spaniards brought enslaved Africans to

New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

, including

Mission Nombre de Dios

Mission Nombre de Dios is a Catholic mission founded in 1587 in St. Augustine, Florida, on the west side of Matanzas Bay. It is part of the Diocese of St. Augustine and is likely the oldest extant mission in the continental United States. T ...

in what would become the city of

St. Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced the development of Western philosop ...

in

Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida () was the first major European land-claim and attempted settlement-area in northern America during the European Age of Discovery. ''La Florida'' formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba in the Viceroyalty of New Spain, and th ...

. Over time, free

Afro-Spaniards

Afro-Spaniards are Spanish people of African descent, including North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa and those of Afro-Caribbean, African American or Afro Latin American descent. The Spanish government does not collect data on ethnicity or racial se ...

took up various trades and occupations and served in the

colonial militia.

After King

Charles II of Spain

Charles II (6 November 1661 – 1 November 1700) was King of Spain from 1665 to 1700. The last monarch from the House of Habsburg, which had ruled Spain since 1516, he died without an heir, leading to a European Great Power conflict over the succ ...

proclaimed Spanish Florida a safe haven for escaped slaves from British North America, they began escaping to Florida by the hundreds from as far north as

New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

. The Spanish established

Fort Mose

Fort Mose (originally known as Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose oyal Grace of Saint Teresa of Mose and later as Fort Mose, or alternatively Fort Moosa or Fort Mossa) is a former Spanish fort in St. Augustine, Florida. In 1738, the governor of ...

for free Blacks in the St. Augustine area in 1738.

In 1806, enslaved people arrived at the

Stone Fort in

Nacogdoches, Texas

Nacogdoches ( ) is a city in East Texas and the county seat of Nacogdoches County, Texas, United States. The 2020 U.S. census recorded the city's population at 32,147. Stephen F. Austin State University is located in Nacogdoches and special ...

seeking freedom. They arrived with a forged passport from a Kentucky judge. The Spanish refused to return them back to the United States. More freedom seekers traveled through Texas the following year.

Enslaved people were emancipated by crossing the border from the United States into Mexico, which was a

Spanish colony

The Spanish Empire, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy or the Catholic Monarchy, was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976. In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered in the European Age of Discovery. It ...

into the nineteenth century. In the United States, enslaved people were considered property. That meant that they did not have rights to marry and they could be sold away from their partners. They also did not have rights to fight inhumane and cruel punishment. In

New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

, fugitive slaves were recognized as humans. They were allowed to join the Catholic Church and marry. They also were protected from inhumane and cruel punishment.

During the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

,

U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of the United Stat ...

general

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

invaded

Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida () was the first major European land-claim and attempted settlement-area in northern America during the European Age of Discovery. ''La Florida'' formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba in the Viceroyalty of New Spain, and th ...

in part because enslaved people had run away from plantations in the Carolinas and Georgia to Florida. Some of the runaways joined the

Black Seminoles

The Black Seminoles, or Afro-Seminoles, are an ethnic group of mixed Native Americans in the United States, Native American and African American, African origin associated with the Seminole people in Florida and Oklahoma. They are mostly blood de ...

who later moved to Mexico.

However, Mexico sent mixed signals on its position against slavery. Sometimes it allowed enslaved people to be returned to slavery and it allowed Americans to move into Spanish territorial property in order to populate the North, where the Americans would then establish cotton plantations, bringing enslaved people to work the land.

In 1829, Mexican president

Vicente Guerrero

Vicente Ramón Guerrero Saldaña (; baptized 10 August 1782 – 14 February 1831) was a Mexican military officer from 1810–1821 and a statesman who became the nation's second president in 1829. He was one of the leading generals who fought ag ...

(who was a mixed race black man) formally abolished slavery in Mexico. Freedom seekers from Southern plantations in the

Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion of the Southern United States. The term is used to describe the states which were most economically dependent on Plantation complexes in the Southern United States, plant ...

, particularly from Louisiana, Mississippi and Texas, escaped slavery and headed for Mexico.

At that time, Texas was part of Mexico. The

Texas Revolution

The Texas Revolution (October 2, 1835 – April 21, 1836) was a rebellion of colonists from the United States and Tejanos (Hispanic Texans) against the Centralist Republic of Mexico, centralist government of Mexico in the Mexican state of ...

, initiated in part to legalize slavery, resulted in the formation of the

Republic of Texas

The Republic of Texas (), or simply Texas, was a country in North America that existed for close to 10 years, from March 2, 1836, to February 19, 1846. Texas shared borders with Centralist Republic of Mexico, the Republic of the Rio Grande, an ...

in 1836. Following the

Battle of San Jacinto

The Battle of San Jacinto (), fought on April 21, 1836, in present-day La Porte and Deer Park, Texas, was the final and decisive battle of the Texas Revolution. Led by General Samuel Houston, the Texan Army engaged and defeated General A ...

, there were some enslaved people who withdrew from the Houston area with the Mexican army, seeing the troops as a means to escape slavery. When Texas joined the Union in 1845, it was a

slave state

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were prohibited. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave s ...

and the Rio Grande became the international border with Mexico.

Pressure between free and slave states deepened as Mexico abolished slavery and western states joined the Union as free states. As more free states were added to the Union, the lesser the influence of slave state representatives in Congress.

Slave states and slave hunters

The Southern Underground Railroad went through slave states, lacking the abolitionist societies and the organized system of the north. People who spoke out against slavery were subject to mobs, physical assault, and being hanged. There were slave catchers who looked for runaway slaves. There were never more than a few hundred free blacks in Texas, which meant that free blacks did not feel safe in the state. The network to freedom was informal, random, and dangerous.

U.S. military

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. U.S. federal law names six armed forces: the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and the Coast Guard. Since 1949, all of the armed forces, except th ...

forts, established along the Rio Grande border during the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

of the 1840s, captured and returned fleeing enslaved people to their slaveholders.

The

Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was a law passed by the 31st United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern interests in slavery and Northern Free-Soilers.

The Act was one ...

made it a criminal offense to aid fleeing enslaved people in

free states. Similarly, the United States government wanted to enact a treaty with Mexico to facilitate the capture and return of escaped slaves in that country. Mexico, however, continued its practice of allowing any slave who crossed its border to be free. Slave catchers, though, continued to cross the southern border into Mexico and illegally capture black people and return them to slavery. A group of slave hunters became the

Texas Rangers.

Routes

Thousands of freedom seekers traveled along a network from the southern United States to Texas and ultimately Mexico. Southern enslaved people generally traveled across "unforgiving country" on foot or horseback while pursued by lawmen and slave hunters. Some stowed away on ferries bound for a Mexican port from

New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

, Louisiana and

Galveston, Texas

Galveston ( ) is a Gulf Coast of the United States, coastal resort town, resort city and port off the Southeast Texas coast on Galveston Island and Pelican Island (Texas), Pelican Island in the U.S. state of Texas. The community of , with a pop ...

. There were some who transported cotton to

Brownsville, Texas

Brownsville ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Texas and the county seat of Cameron County, Texas, Cameron County, located on the western Gulf Coast in South Texas, adjacent to the Mexico–United States border, border with Matamoros, Tamaulipas ...

on wagons and then crossed into Mexico at

Matamoros.

Many traveled through North Carolina, Arkansas, Alabama, Louisiana, or Mississippi toward Texas and ultimately Mexico. People fled slavery from

Indian Territory

Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United States, ...

(now Oklahoma).

Black Seminoles

The Black Seminoles, or Afro-Seminoles, are an ethnic group of mixed Native Americans in the United States, Native American and African American, African origin associated with the Seminole people in Florida and Oklahoma. They are mostly blood de ...

traveled on a southwestern route from Florida into Mexico.

Going overland meant that the last 150 miles or so were traversed through the difficult and extremely hot terrain of the

Nueces Strip

The Nueces Strip or Wild Horse Desert is the area of South Texas between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande.

According to the narrative of Spanish missionary Juan Agustín Morfi, there were so many wild horses swarming in the Nueces Strip i ...

located between the

Nueces River

The Nueces River ( ; , ) is a river in the U.S. state of Texas, about long. It drains a region in central and southern Texas southeastward into the Gulf of Mexico. It is the southernmost major river in Texas northeast of the Rio Grande. ''Nu ...

and the

Rio Grande

The Rio Grande ( or ) in the United States or the Río Bravo (del Norte) in Mexico (), also known as Tó Ba'áadi in Navajo language, Navajo, is one of the principal rivers (along with the Colorado River) in the Southwestern United States a ...

. There was little shade and a lack of potable water in this brush country. Escapees were more likely to survive the trip if they had a horse and a gun.

The

National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an List of federal agencies in the United States, agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, within the US Department of the Interior. The service manages all List ...

identified a route from

Natchitoches, Louisiana

Natchitoches ( ; , ), officially the City of Natchitoches, is a small city in, and the parish seat of, Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana, Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana, United States. At the 2020 United States census, the city's population was ...

to

Monclova

Monclova (), is a city and the seat of the surrounding municipality of the same name in the northern Mexican state of Coahuila. According to the 2015 census, the city had 231,107 inhabitants. Its metropolitan area has 381,432 inhabitants and ...

,

Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

in 2010 that is roughly the southern Underground Railroad path. It is also believed that ''

El Camino Real de los Tejas

EL, El or el may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Fictional entities

* El, a character from the manga series ''Shugo Chara!'' by Peach-Pit

* Eleven (''Stranger Things'') (El), a fictional character in the TV series ''Stranger Things''

* El, fami ...

'' was a path for freedom. It was made a

National Historic Trail

The National Trails System is a series of trails in the United States designated "to promote the preservation of, public access to, travel within, and enjoyment and appreciation of the open-air, outdoor areas and historic resources of the Nati ...

by President

George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician and businessman who was the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Bush family and the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he i ...

in 2004.

Assistance

Some journeyed on their own without assistance, and others were helped by people along the southern Underground Railroad. Assistance included guidance, directions, shelter, and supplies.

Black people, black and white couples, and anti-slavery German immigrants provided support, but most of the help came from Mexican laborers. So much so that enslavers came to distrust any Mexican, and a law was enacted in Texas that forbade Mexicans from talking to enslaved people. Mexican migrant workers developed relationships with enslaved black workers whom they worked with. They offered guidance, such as what it would be like to cross the border, and empathy. Having realized the ways in which Mexicans were helping enslaved people to escape, slaveholders and residents of Texan towns pushed people out of the town, whipped them in public, or lynched them.

Some border officials helped enslaved people crossing into Mexico. In

Monclova

Monclova (), is a city and the seat of the surrounding municipality of the same name in the northern Mexican state of Coahuila. According to the 2015 census, the city had 231,107 inhabitants. Its metropolitan area has 381,432 inhabitants and ...

,

Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

a border official took up a collection in the town for a family in need of food, clothing, and money to continue on their journey south and out of reach of slave hunters.

Once they crossed the border, some Mexican authorities helped former enslaved people from being returned to the United States by slave hunters.

Freedom seekers that were taken on ferries to Mexican ports were aided by Mexican ship captains, one of whom was caught in Louisiana and indicted for helping enslaved people escape.

Knowing the repercussions of running away or being caught helping someone runaway, people were careful to cover their tracks, and public and personal records about fugitive slaves are scarce. In greater supply are records by people who promoted slavery or attempted to catch fugitive slaves. More than 2,500 escapes are documented by the Texas Runaway Slave Project at

Stephen F. Austin State University

Stephen F. Austin State University (SFASU or SFA) is a public university in Nacogdoches, Texas, in the United States. Named after Stephen F. Austin, one of the founders of Texas, SFA was founded as a teachers college in 1923 and built on part ...

.

Southern freedom seekers

Advertisements were placed in newspapers offering rewards for the return of their "property". Slave catchers traveled through Mexico. There were

Black Seminoles

The Black Seminoles, or Afro-Seminoles, are an ethnic group of mixed Native Americans in the United States, Native American and African American, African origin associated with the Seminole people in Florida and Oklahoma. They are mostly blood de ...

, or ''Los Mascogos'' who lived in northern Mexico who provided armed resistance.

Sam Houston

Samuel Houston (, ; March 2, 1793 – July 26, 1863) was an American general and statesman who played a prominent role in the Texas Revolution. He served as the first and third president of the Republic of Texas and was one of the first two indi ...

, president of the

Republic of Texas

The Republic of Texas (), or simply Texas, was a country in North America that existed for close to 10 years, from March 2, 1836, to February 19, 1846. Texas shared borders with Centralist Republic of Mexico, the Republic of the Rio Grande, an ...

, was the slaveholder to

Tom

Tom or TOM may refer to:

* Tom (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the name.

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''Tom'' (1973 film), or ''The Bad Bunch'', a blaxploitation film

* ''Tom'' (2002 film) ...

who ran away. He headed to Texas and once there he enlisted in the Mexican military.

One enslaved man was branded with the letter "R" on each side of his cheek after a failed attempt to escape slavery. He tried again in the winter of 1819, leaving the cotton plantation of his enslaver on horseback. With four others, they traveled southwest to Mexico at the risk of being attacked by hostile Native Americans, apprehended by slave catchers, or attacked by "horse-eating alligators".

Many people did not make it to Mexico. In 1842, a Mexican man and a black woman left

Jackson County, Texas

Jackson County is a county in the U.S. state of Texas. As of the 2020 census its population was 14,988. Its county seat is Edna. The county was created in 1835 as a municipality in Mexico and in 1836 was organized as a county (of the Repub ...

on two horses, but they were caught at the

Lavaca River

The Lavaca River is a navigable river in Texas. It begins in the northeastern part of Gonzales County, and travels generally southeast for until it empties into Lavaca Bay, a component of Matagorda Bay.

History

The navigable Texas river's na ...

. The wife, an enslaved woman, was valuable to her owner so she was returned to slavery. Her husband, possibly a farm laborer or an indentured servant, was immediately lynched.