Ornithological Advances on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ornithology, from

The word "ornithology" comes from the late 16th-century Latin ''ornithologia'' meaning "bird science" from the

The word "ornithology" comes from the late 16th-century Latin ''ornithologia'' meaning "bird science" from the

Early written records provide valuable information on the past distributions of species. For instance,

Early written records provide valuable information on the past distributions of species. For instance,

William Turner's ''Historia Avium'' (''History of Birds''), published at

William Turner's ''Historia Avium'' (''History of Birds''), published at

The emergence of ornithology as a scientific discipline began in the 18th century, when

The emergence of ornithology as a scientific discipline began in the 18th century, when  The search for patterns in the variations of birds was attempted by many.

The search for patterns in the variations of birds was attempted by many.  For Darwin, the problem was how species arose from a common ancestor, but he did not attempt to find rules for delineation of species. The

For Darwin, the problem was how species arose from a common ancestor, but he did not attempt to find rules for delineation of species. The  John Hurrell Crook studied the behaviour of weaverbirds and demonstrated the links between ecological conditions, behaviour, and social systems. Principles from

John Hurrell Crook studied the behaviour of weaverbirds and demonstrated the links between ecological conditions, behaviour, and social systems. Principles from

The rise of field guides for the identification of birds was another major innovation. The early guides such as Thomas Bewick's two-volume guide and William Yarrell's three-volume guide were cumbersome, and mainly focused on identifying specimens in the hand. The earliest of the new generation of field guides was prepared by Florence Merriam, sister of

The rise of field guides for the identification of birds was another major innovation. The early guides such as Thomas Bewick's two-volume guide and William Yarrell's three-volume guide were cumbersome, and mainly focused on identifying specimens in the hand. The earliest of the new generation of field guides was prepared by Florence Merriam, sister of

The earliest approaches to modern bird study involved the collection of eggs, a practice known as

The earliest approaches to modern bird study involved the collection of eggs, a practice known as  The use of bird skins to document species has been a standard part of systematic ornithology. Bird skins are prepared by retaining the key bones of the wings, legs, and skull along with the skin and feathers. In the past, they were treated with

The use of bird skins to document species has been a standard part of systematic ornithology. Bird skins are prepared by retaining the key bones of the wings, legs, and skull along with the skin and feathers. In the past, they were treated with

The capture and marking of birds enable detailed studies of life history. Techniques for capturing birds are varied and include the use of bird liming for perching birds,

The capture and marking of birds enable detailed studies of life history. Techniques for capturing birds are varied and include the use of bird liming for perching birds,  The bird in the hand may be examined and

The bird in the hand may be examined and  Captured birds are often marked for future recognition. Rings or bands provide long-lasting identification, but require capture for the information on them to be read. Field-identifiable marks such as coloured bands, wing tags, or dyes enable short-term studies where individual identification is required.

Captured birds are often marked for future recognition. Rings or bands provide long-lasting identification, but require capture for the information on them to be read. Field-identifiable marks such as coloured bands, wing tags, or dyes enable short-term studies where individual identification is required.

Studies of

Studies of

With the widespread interest in birds, use of a large number of people to work on collaborative ornithological projects that cover large geographic scales has been possible. These

With the widespread interest in birds, use of a large number of people to work on collaborative ornithological projects that cover large geographic scales has been possible. These

Spring Alive

in Europe. These projects help to identify distributions of birds, their population densities and changes over time, arrival and departure dates of migration, breeding seasonality, and even population genetics. The results of many of these projects are published as bird atlases. Studies of migration using bird ringing or colour marking often involve the cooperation of people and organizations in different countries.

The role of some species of birds as pests has been well known, particularly in agriculture. Granivorous birds such as the

The role of some species of birds as pests has been well known, particularly in agriculture. Granivorous birds such as the

*

Ornithologie

' (1773–1792) Francois Nicholas Martinet Digital Edition Smithsonian Digital Libraries *

History of ornithology and ornithology collections in Victoria, Australia

on Culture Victoria *

* {{Authority control Ornithology, Subfields of zoology Scoutcraft

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

ὄρνις (''órnis''), meaning "bird", and -logy

''-logy'' is a suffix in the English language, used with words originally adapted from Ancient Greek ending in ('). The earliest English examples were anglicizations of the French '' -logie'', which was in turn inherited from the Latin '' -l ...

from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study", is a branch of zoology

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

dedicated to the study of bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s. Several aspects of ornithology differ from related disciplines, due partly to the high visibility and the aesthetic

Aesthetics (also spelled esthetics) is the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature of beauty and taste, which in a broad sense incorporates the philosophy of art.Slater, B. H.Aesthetics ''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy,'' , acces ...

appeal of birds. It has also been an area with a large contribution made by amateurs in terms of time, resources, and financial support. Studies on birds have helped develop key concepts in biology including evolution, behaviour and ecology such as the definition of species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

, the process of speciation

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which populations evolve to become distinct species. The biologist Orator F. Cook coined the term in 1906 for cladogenesis, the splitting of lineages, as opposed to anagenesis, phyletic evolution within ...

, instinct

Instinct is the inherent inclination of a living organism towards a particular complex behaviour, containing innate (inborn) elements. The simplest example of an instinctive behaviour is a fixed action pattern (FAP), in which a very short to me ...

, learning

Learning is the process of acquiring new understanding, knowledge, behaviors, skills, value (personal and cultural), values, Attitude (psychology), attitudes, and preferences. The ability to learn is possessed by humans, non-human animals, and ...

, ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of Resource (biology), resources an ...

s, guilds

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular territory. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradespeople belonging to a professional association. They so ...

, insular biogeography

Insular biogeography or island biogeography is a field within biogeography that examines the factors that affect the species richness and diversification of isolated natural communities. The theory was originally developed to explain the pattern o ...

, phylogeography

Phylogeography is the study of the historical processes that may be responsible for the past to present geographic distributions of genealogical lineages. This is accomplished by considering the geographic distribution of individuals in light of ge ...

, and conservation.

While early ornithology was principally concerned with descriptions and distributions of species, ornithologists today seek answers to very specific questions, often using birds as models to test hypotheses or predictions based on theories. Most modern biological theories apply across life forms, and the number of scientists who identify themselves as "ornithologists" has therefore declined. A wide range of tools and techniques are used in ornithology, both inside the laboratory and out in the field, and innovations are constantly made. Most biologists who recognise themselves as "ornithologists" study specific biology research areas, such as anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of morphology concerned with the study of the internal structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old scien ...

, physiology

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

, taxonomy

image:Hierarchical clustering diagram.png, 280px, Generalized scheme of taxonomy

Taxonomy is a practice and science concerned with classification or categorization. Typically, there are two parts to it: the development of an underlying scheme o ...

(phylogenetics

In biology, phylogenetics () is the study of the evolutionary history of life using observable characteristics of organisms (or genes), which is known as phylogenetic inference. It infers the relationship among organisms based on empirical dat ...

), ecology

Ecology () is the natural science of the relationships among living organisms and their Natural environment, environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community (ecology), community, ecosystem, and biosphere lev ...

, or behaviour

Behavior (American English) or behaviour (British English) is the range of actions of Individual, individuals, organisms, systems or Artificial intelligence, artificial entities in some environment. These systems can include other systems or or ...

.

Definition and etymology

The word "ornithology" comes from the late 16th-century Latin ''ornithologia'' meaning "bird science" from the

The word "ornithology" comes from the late 16th-century Latin ''ornithologia'' meaning "bird science" from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

ὄρνις ''ornis'' ("bird") and λόγος ''logos'' ("theory, science, thought").

History

The history of ornithology largely reflects the trends in thehistory of biology

The history of biology traces the study of the life, living world from ancient to Modernity, modern times. Although the concept of ''biology'' as a single coherent field arose in the 19th century, the biological sciences emerged from history o ...

, as well as many other scientific disciplines, including ecology

Ecology () is the natural science of the relationships among living organisms and their Natural environment, environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community (ecology), community, ecosystem, and biosphere lev ...

, anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of morphology concerned with the study of the internal structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old scien ...

, physiology

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

, paleontology

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure ge ...

, and more recently, molecular biology. Trends include the move from mere descriptions to the identification of patterns, thus towards elucidating the processes that produce these patterns.

Early knowledge and study

Humans have had an observational relationship with birds sinceprehistory

Prehistory, also called pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the first known use of stone tools by hominins million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use ...

, with some stone-age drawings being amongst the oldest indications of an interest in birds. Birds were perhaps important as food sources, and bones of as many as 80 species have been found in excavations of early Stone Age

The Stone Age was a broad prehistory, prehistoric period during which Rock (geology), stone was widely used to make stone tools with an edge, a point, or a percussion surface. The period lasted for roughly 3.4 million years and ended b ...

settlements. Water bird

A water bird, alternatively waterbird or aquatic bird, is a bird that lives on or around water. In some definitions, the term ''water bird'' is especially applied to birds in freshwater ecosystems, although others make no distinction from seabi ...

and seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adaptation, adapted to life within the marine ecosystem, marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent ...

remains have also been found in shell mound

A midden is an old dump for domestic waste. It may consist of animal bones, human excrement, botanical material, mollusc shells, potsherds, lithics (especially debitage), and other artifacts and ecofacts associated with past human occup ...

s on the island of Oronsay off the coast of Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

.

Cultures around the world have rich vocabularies related to birds. Traditional bird names are often based on detailed knowledge of the behaviour, with many names being onomatopoeic

Onomatopoeia (or rarely echoism) is a type of word, or the process of creating a word, that phonetically imitates, resembles, or suggests the sound that it describes. Common onomatopoeias in English include animal noises such as ''oink'', '' ...

, and still in use. Traditional knowledge may also involve the use of birds in folk medicine and knowledge of these practices are passed on through oral traditions (see ethnoornithology). Hunting of wild birds as well as their domestication would have required considerable knowledge of their habits. Poultry

Poultry () are domesticated birds kept by humans for the purpose of harvesting animal products such as meat, Eggs as food, eggs or feathers. The practice of animal husbandry, raising poultry is known as poultry farming. These birds are most typ ...

farming and falconry

Falconry is the hunting of wild animals in their natural state and habitat by means of a trained bird of prey. Small animals are hunted; squirrels and rabbits often fall prey to these birds. Two traditional terms are used to describe a person ...

were practised from early times in many parts of the world. Artificial incubation of poultry was practised in China around 246 BC and around at least 400 BC in Egypt. The Egyptians also made use of birds in their hieroglyphic scripts, many of which, though stylized, are still identifiable to species. Early written records provide valuable information on the past distributions of species. For instance,

Early written records provide valuable information on the past distributions of species. For instance, Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; ; 355/354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian. At the age of 30, he was elected as one of the leaders of the retreating Ancient Greek mercenaries, Greek mercenaries, the Ten Thousand, who had been ...

records the abundance of the ostrich

Ostriches are large flightless birds. Two living species are recognised, the common ostrich, native to large parts of sub-Saharan Africa, and the Somali ostrich, native to the Horn of Africa.

They are the heaviest and largest living birds, w ...

in Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , ''māt Aššur'') was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization that existed as a city-state from the 21st century BC to the 14th century BC and eventually expanded into an empire from the 14th century BC t ...

(Anabasis, i. 5); this subspecies from Asia Minor is extinct and all extant ostrich races are today restricted to Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

. Other old writings such as the Vedas

FIle:Atharva-Veda samhita page 471 illustration.png, upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the ''Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas ( or ; ), sometimes collectively called the Veda, are a large body of relig ...

(1500–800 BC) demonstrate the careful observation of avian life histories and include the earliest reference to the habit of brood parasitism

Brood parasitism is a subclass of parasitism and phenomenon and behavioural pattern of animals that rely on others to raise their young. The strategy appears among birds, insects and fish. The brood parasite manipulates a host, either of the ...

by the Asian koel (''Eudynamys scolopaceus''). Like writing, the early art of China, Japan, Persia, and India also demonstrate knowledge, with examples of scientifically accurate bird illustrations.

Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

in 350 BC in his ''History of animals

''History of Animals'' (, ''Ton peri ta zoia historion'', "Inquiries on Animals"; , "History of Animals") is one of the major texts on biology by the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle. It was written in sometime between the mid-fourth centur ...

'' noted the habit of bird migration

Bird migration is a seasonal movement of birds between breeding and wintering grounds that occurs twice a year. It is typically from north to south or from south to north. Animal migration, Migration is inherently risky, due to predation and ...

, moulting, egg laying, and lifespans, as well as compiling a list of 170 different bird species. However, he also introduced and propagated several myths, such as the idea that swallow

The swallows, martins, and saw-wings, or Hirundinidae are a family of passerine songbirds found around the world on all continents, including occasionally in Antarctica. Highly adapted to aerial feeding, they have a distinctive appearance. The ...

s hibernated in winter, although he noted that cranes migrated from the steppes of Scythia

Scythia (, ) or Scythica (, ) was a geographic region defined in the ancient Graeco-Roman world that encompassed the Pontic steppe. It was inhabited by Scythians, an ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic people.

Etymology

The names ...

to the marshes at the headwaters of the Nile

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the List of river sy ...

. The idea of swallow hibernation became so well established that even as late as in 1878, Elliott Coues

Elliott Ladd Coues (; September 9, 1842 – December 25, 1899) was an American army surgeon, historian, ornithologist, and author. He led surveys of the Arizona Territory, and later as secretary of the United States Geological and Geographi ...

could list as many as 182 contemporary publications dealing with the hibernation of swallows and little published evidence to contradict the theory. Similar misconceptions existed regarding the breeding of barnacle geese

The barnacle goose (''Branta leucopsis'') is a species of goose that belongs to the genus '' Branta'' of black geese, which contains species with extensive black in the plumage, distinguishing them from the grey '' Anser'' species. Despite its s ...

. Their nests had not been seen, and they were believed to grow by transformations of goose barnacles

Goose barnacles, also called percebes, turtle-claw barnacles, stalked barnacles, gooseneck barnacles, are filter-feeding crustaceans that live attached to hard surfaces of rocks and flotsam in the ocean intertidal zone. Goose barnacles formerl ...

, an idea that became prevalent from around the 11th century and noted by Bishop Giraldus Cambrensis (Gerald of Wales

Gerald of Wales (; ; ; ) was a Cambro-Norman priest and historian. As a royal clerk to the king and two archbishops, he travelled widely and wrote extensively. He studied and taught in France and visited Rome several times, meeting the Pope. He ...

) in ''Topographia Hiberniae

''Topographia Hibernica'' (Latin for ''Topography of Ireland''), also known as ''Topographia Hiberniae'', is an account of the landscape and people of Ireland written by Gerald of Wales around 1188, soon after the Norman invasion of Ireland. ...

'' (1187). Around 77 AD, Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

described birds, among other creatures, in his '' Historia Naturalis''.

The earliest record of falconry comes from the reign of Sargon II (722–705 BC) in Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , ''māt Aššur'') was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization that existed as a city-state from the 21st century BC to the 14th century BC and eventually expanded into an empire from the 14th century BC t ...

. Falconry is thought to have made its entry to Europe only after AD 400, brought in from the east after invasions by the Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th centuries AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was par ...

and Alans

The Alans () were an ancient and medieval Iranian peoples, Iranic Eurasian nomads, nomadic pastoral people who migrated to what is today North Caucasus – while some continued on to Europe and later North Africa. They are generally regarded ...

. Starting from the eighth century, numerous Arabic works on the subject and general ornithology were written, as well as translations of the works of ancient writers from Greek and Syriac. In the 12th and 13th centuries, crusades and conquest had subjugated Islamic territories in southern Italy, central Spain, and the Levant under European rule, and for the first time translations into Latin of the great works of Arabic and Greek scholars were made with the help of Jewish and Muslim scholars, especially in Toledo, which had fallen into Christian hands in 1085 and whose libraries had escaped destruction. Michael Scot

Michael Scot (Latin: Michael Scotus; 1175 – ) was a Scottish mathematician and scholar in the Middle Ages. He was educated at University of Oxford, Oxford and University of Paris, Paris, and worked in Bologna and Toledo, Spain, Toledo, where ...

us from Scotland made a Latin translation of Aristotle's work on animals from Arabic here around 1215, which was disseminated widely and was the first time in a millennium that this foundational text on zoology became available to Europeans. Falconry was popular in the Norman court in Sicily, and a number of works on the subject were written in Palermo

Palermo ( ; ; , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital (political), capital of both the autonomous area, autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan province. The ...

. Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen (1194–1250) learned about an falconry during his youth in Sicily and later built up a menagerie

A menagerie is a collection of captive animals, frequently exotic, kept for display; or the place where such a collection is kept, a precursor to the modern zoo or zoological garden.

The term was first used in 17th-century France, referring to ...

and sponsored translations of Arabic texts, among which the popular Arabic work known as the '' Liber Moaminus'' by an unknown author which was translated into Latin by Theodore of Antioch from Syria in 1240–1241 as the ''De Scientia Venandi per Aves'', and also Michael Scotus (who had removed to Palermo) translated Ibn Sīnā

Ibn Sina ( – 22 June 1037), commonly known in the West as Avicenna ( ), was a preeminent philosopher and physician of the Muslim world, flourishing during the Islamic Golden Age, serving in the courts of various Iranian rulers. He is oft ...

's '' Kitāb al-Ḥayawān'' of 1027 for the Emperor, a commentary and scientific update of Aristotle's work which was part of Ibn Sīnā's massive '' Kitāb al-Šifāʾ''. Frederick II eventually wrote his own treatise on falconry, the ''De arte venandi cum avibus

''De Arte Venandi cum Avibus'' () is a Latin treatise on ornithology and falconry written in the 1240s by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II. One of the surviving manuscripts is dedicated to his son Manfred. Manuscripts of ''De arte venandi cu ...

'', in which he related his ornithological observations and the results of the hunts and experiments his court enjoyed performing.

Several early German and French scholars compiled old works and conducted new research on birds. These included Guillaume Rondelet

Guillaume Rondelet (27 September 150730 July 1566), also known as Rondeletus/Rondeletius, was Regius professor of medicine at the University of Montpellier in southern France and Chancellor of the University between 1556 and his death in 1566. He ...

, who described his observations in the Mediterranean, and Pierre Belon

Pierre Belon (1517–1564) was a French traveller, natural history, naturalist, writer and diplomat. Like many others of the Renaissance period, he studied and wrote on a range of topics including ichthyology, ornithology, botany, comparative anat ...

, who described the fish and birds that he had seen in France and the Levant. Belon's ''Book of Birds'' (1555) is a folio volume with descriptions of some 200 species. His comparison of the skeleton of humans and birds is considered as a landmark in comparative anatomy

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of different species. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny (the evolution of species).

The science began in the classical era, continuing in t ...

. Volcher Coiter (1534–1576), a Dutch anatomist, made detailed studies of the internal structures of birds and produced a classification of birds, ''De Differentiis Avium'' (around 1572), that was based on structure and habits. Konrad Gesner

Conrad Gessner (; ; 26 March 1516 – 13 December 1565) was a Swiss physician, naturalist, bibliographer, and philologist. Born into a poor family in Zürich, Switzerland, his father and teachers quickly realised his talents and supported him t ...

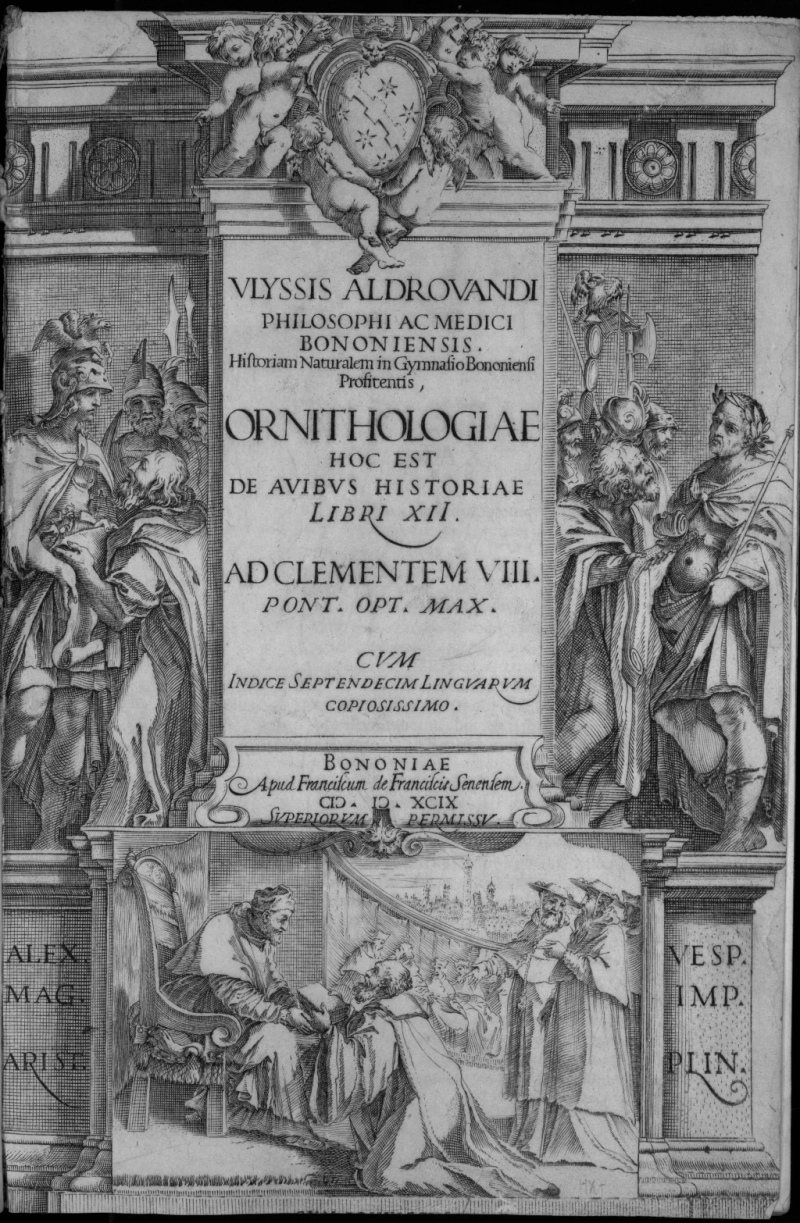

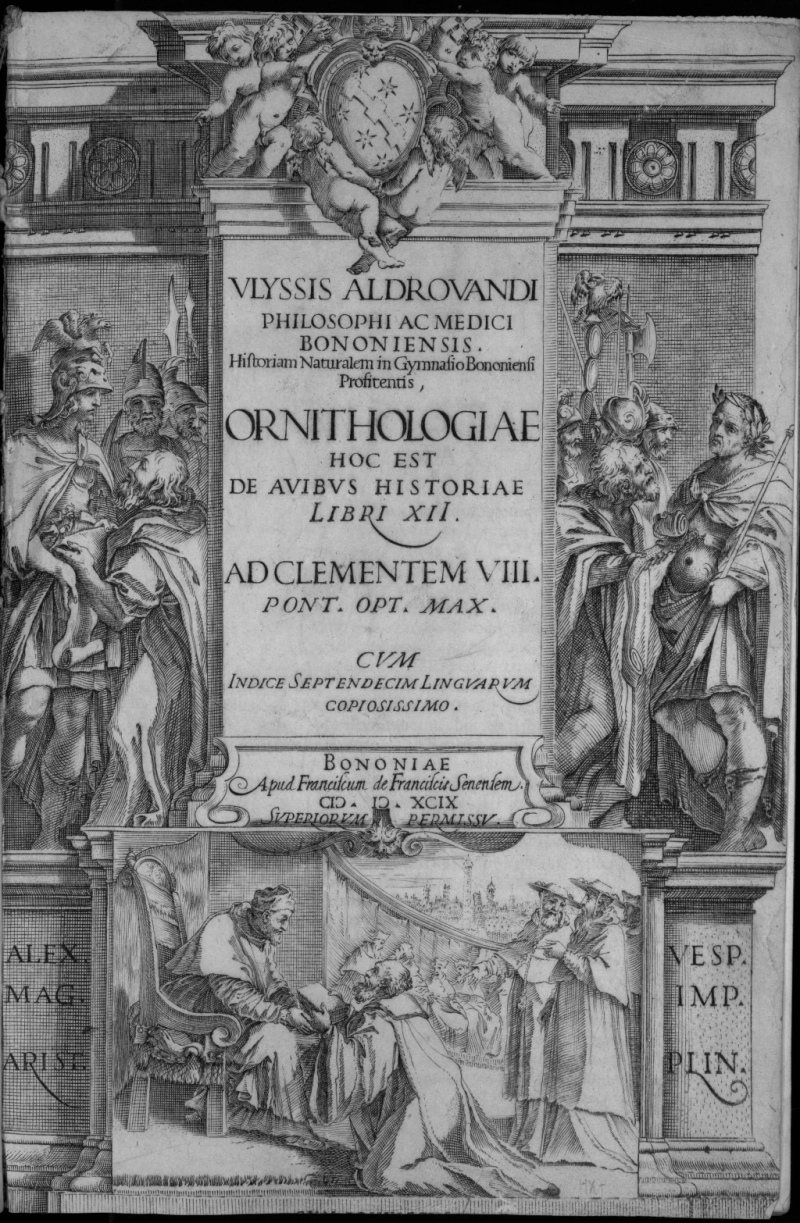

wrote the ''Vogelbuch'' and ''Icones avium omnium'' around 1557. Like Gesner, Ulisse Aldrovandi

Ulisse Aldrovandi (11 September 1522 – 4 May 1605) was an Italian naturalist, the moving force behind Bologna's botanical garden, one of the first in Europe. Carl Linnaeus and the comte de Buffon reckoned him the father of natural history stud ...

, an encyclopedic naturalist, began a 14-volume natural history with three volumes on birds, entitled ''ornithologiae hoc est de avibus historiae libri XII'', which was published from 1599 to 1603. Aldrovandi showed great interest in plants and animals, and his work included 3000 drawings of fruits, flowers, plants, and animals, published in 363 volumes. His ''Ornithology'' alone covers 2000 pages and included such aspects as the chicken

The chicken (''Gallus gallus domesticus'') is a domesticated subspecies of the red junglefowl (''Gallus gallus''), originally native to Southeast Asia. It was first domesticated around 8,000 years ago and is now one of the most common and w ...

and poultry techniques. He used a number of traits including behaviour, particularly bathing and dusting, to classify bird groups.

William Turner's ''Historia Avium'' (''History of Birds''), published at

William Turner's ''Historia Avium'' (''History of Birds''), published at Cologne

Cologne ( ; ; ) is the largest city of the States of Germany, German state of North Rhine-Westphalia and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with nearly 1.1 million inhabitants in the city pr ...

in 1544, was an early ornithological work from England. He noted the commonness of kite

A kite is a tethered heavier than air flight, heavier-than-air craft with wing surfaces that react against the air to create Lift (force), lift and Drag (physics), drag forces. A kite consists of wings, tethers and anchors. Kites often have ...

s in English cities where they snatched food out of the hands of children. He included folk beliefs such as those of anglers. Anglers believed that the osprey

The osprey (; ''Pandion haliaetus''), historically known as sea hawk, river hawk, and fish hawk, is a diurnal, fish-eating bird of prey with a cosmopolitan range. It is a large raptor, reaching more than in length and a wingspan of . It ...

emptied their fishponds and would kill them, mixing the flesh of the osprey into their fish bait. Turner's work reflected the violent times in which he lived, and stands in contrast to later works such as Gilbert White

Gilbert White (18 July 1720 – 26 June 1793) was a "parson-naturalist", a pioneering English naturalist, ecologist, and ornithologist. He is best known for his '' Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne''.

Life

White was born on 18 Jul ...

's 1789 '' The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne'' that were written in a tranquil era.

In the 17th century, Francis Willughby

Francis Willughby (sometimes spelt Willoughby, ) Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (22 November 1635 – 3 July 1672) was an English ornithology, ornithologist, ichthyology, ichthyologist and mathematician, and an early student of linguistics an ...

(1635–1672) and John Ray

John Ray Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (November 29, 1627 – January 17, 1705) was a Christian England, English Natural history, naturalist widely regarded as one of the earliest of the English parson-naturalists. Until 1670, he wrote his ...

(1627–1705) created the first major system of bird classification that was based on function and morphology rather than on form or behaviour. Willughby's ''Ornithologiae libri tres'' (1676) completed by John Ray is sometimes considered to mark the beginning of scientific ornithology. Ray also worked on ''Ornithologia'', which was published posthumously in 1713 as ''Synopsis methodica avium et piscium''. The earliest list of British birds, ''Pinax Rerum Naturalium Britannicarum'', was written by Christopher Merrett in 1667, but authors such as John Ray considered it of little value. Ray did, however, value the expertise of the naturalist Sir Thomas Browne

Sir Thomas Browne ( "brown"; 19 October 160519 October 1682) was an English polymath and author of varied works which reveal his wide learning in diverse fields including science and medicine, religion and the esoteric. His writings display a d ...

(1605–82), who not only answered his queries on ornithological identification and nomenclature, but also those of Willoughby and Merrett in letter correspondence. Browne himself in his lifetime kept an eagle, owl, cormorant, bittern, and ostrich, penned a tract on falconry, and introduced the words "incubation" and "oviparous" into the English language.

Towards the late 18th century, Mathurin Jacques Brisson

Mathurin Jacques Brisson (; 30 April 1723 – 23 June 1806) was a French zoologist and natural philosophy, natural philosopher.

Brisson was born on 30 April 1723 at Fontenay-le-Comte in the Vendée department of western France. Note that page 14 ...

(1723–1806) and Comte de Buffon

Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (; 7 September 1707 – 16 April 1788) was a French naturalist, mathematician, and cosmologist. He held the position of ''intendant'' (director) at the ''Jardin du Roi'', now called the Jardin des plant ...

(1707–1788) began new works on birds. Brisson produced a six-volume work ''Ornithologie'' in 1760 and Buffon's included nine volumes (volumes 16–24) on birds ''Histoire naturelle des oiseaux'' (1770–1785) in his work on science '' Histoire naturelle générale et particulière'' (1749–1804). Jacob Temminck sponsored François Le Vaillant

François () is a French masculine given name and surname, equivalent to the English name Francis.

People with the given name

* François Amoudruz (1926–2020), French resistance fighter

* François-Marie Arouet (better known as Voltaire; ...

753–1824to collect bird specimens in Southern Africa and Le Vaillant's six-volume ''Histoire naturelle des oiseaux d'Afrique'' (1796–1808) included many non-African birds. His other bird books produced in collaboration with the artist Barraband are considered among the most valuable illustrated guides ever produced. Louis Pierre Vieillot

Louis Pierre Vieillot (10 May 1748, Yvetot – 24 August 1830, Sotteville-lès-Rouen) was a French ornithologist.

Vieillot is the author of the first scientific descriptions and Linnaean names of a number of birds, including species he collected ...

(1748–1831) spent 10 years studying North American birds and wrote the ''Histoire naturelle des oiseaux de l'Amerique septentrionale'' (1807–1808?). Vieillot pioneered in the use of life histories and habits in classification. Alexander Wilson composed a nine-volume work, ''American Ornithology'', published 1808–1814, which is the first such record of North American birds, significantly antedating Audubon. In the early 19th century, Lewis and Clark

Lewis may refer to:

Names

* Lewis (given name), including a list of people with the given name

* Lewis (surname), including a list of people with the surname

Music

* Lewis (musician), Canadian singer

* " Lewis (Mistreated)", a song by Radiohe ...

studied and identified many birds in the western United States. John James Audubon

John James Audubon (born Jean-Jacques Rabin, April 26, 1785 – January 27, 1851) was a French-American Autodidacticism, self-trained artist, natural history, naturalist, and ornithology, ornithologist. His combined interests in art and ornitho ...

, born in 1785, observed and painted birds in France and later in the Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

and Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

valleys. From 1827 to 1838, Audubon published '' The Birds of America'', which was engraved by Robert Havell Sr. and his son Robert Havell Jr. Containing 435 engravings, it is often regarded as the greatest ornithological work in history.

Scientific studies

The emergence of ornithology as a scientific discipline began in the 18th century, when

The emergence of ornithology as a scientific discipline began in the 18th century, when Mark Catesby

Mark Catesby (24 March 1683 – 23 December 1749) was an English natural history, naturalist who studied the flora and fauna of the New World. Between 1729 and 1747, Catesby published his ''Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama ...

published his two-volume ''Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands'', a landmark work which included 220 hand-painted engravings and was the basis for many of the species Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

described in the 1758 ''Systema Naturae

' (originally in Latin written ' with the Orthographic ligature, ligature æ) is one of the major works of the Sweden, Swedish botanist, zoologist and physician Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) and introduced the Linnaean taxonomy. Although the syste ...

''. Linnaeus' work revolutionised bird taxonomy by assigning every species a binomial name

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, both of which use Latin grammatical forms, altho ...

, categorising them into different genera. However, ornithology did not emerge as a specialised science until the Victorian era—with the popularization of natural history, and the collection of natural objects such as bird eggs and skins. This specialization led to the formation in Britain of the British Ornithologists' Union

The British Ornithologists' Union (BOU) aims to encourage the study of birds (ornithology) around the world in order to understand their biology and aid their conservation. The BOU was founded in 1858 by Professor Alfred Newton, Henry Baker ...

in 1858. In 1859, the members founded its journal ''The Ibis

''Ibis'' (formerly ''The Ibis''), subtitled ''the International Journal of Avian Science'', is the peer-reviewed scientific journal of the British Ornithologists' Union. It was established in 1859. Topics covered include ecology, conservation, be ...

''. The sudden spurt in ornithology was also due in part to colonialism

Colonialism is the control of another territory, natural resources and people by a foreign group. Colonizers control the political and tribal power of the colonised territory. While frequently an Imperialism, imperialist project, colonialism c ...

. At 100 years later, in 1959, R. E. Moreau noted that ornithology in this period was preoccupied with the geographical distributions of various species of birds.

The bird collectors of the Victorian era observed the variations in bird forms and habits across geographic regions, noting local specialization and variation in widespread species. The collections of museums and private collectors grew with contributions from various parts of the world. The naming of species with binomials and the organization of birds into groups based on their similarities became the main work of museum specialists. The variations in widespread birds across geographical regions caused the introduction of trinomial names.

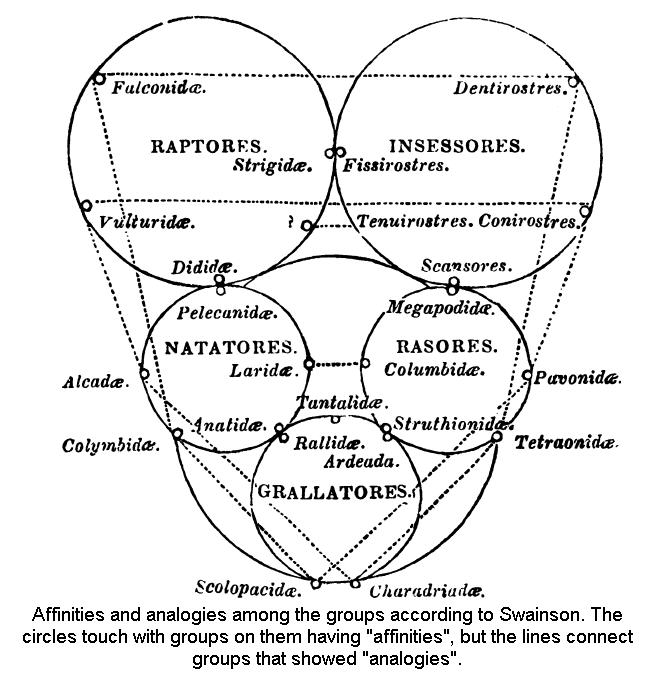

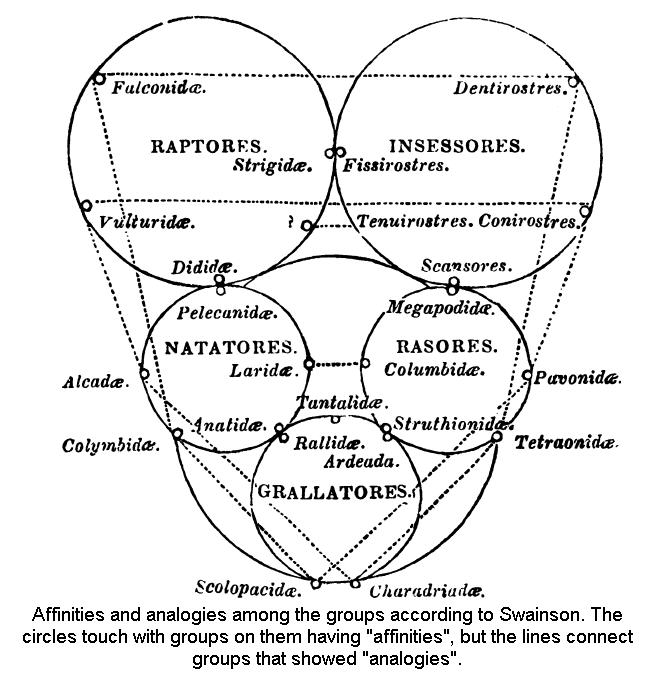

Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling

Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling (; 27 January 1775 – 20 August 1854), later (after 1812) von Schelling, was a German philosopher. Standard histories of philosophy make him the midpoint in the development of German idealism, situating him be ...

(1775–1854), his student Johann Baptist von Spix

Johann Baptist Ritter von Spix (9 February 1781 – 13 March 1826) was a German natural history, biologist. From his expedition to Brazil, he brought to Germany a large variety of specimens of plants, insects, mammals, birds, amphibians and fish. ...

(1781–1826), and several others believed that a hidden and innate mathematical order existed in the forms of birds. They believed that a "natural" classification was available and superior to "artificial" ones. A particularly popular idea was the Quinarian system

The quinarian system was a method of zoological classification which was popular in the mid 19th century, especially among British naturalists. It was largely developed by the entomologist William Sharp Macleay in 1819. The system was further pr ...

popularised by Nicholas Aylward Vigors

Nicholas Aylward Vigors (1785 – 26 October 1840) was an Ireland, Irish zoologist and politician. He popularized the classification of birds on the basis of the quinarian system.

Early life

Vigors was born at Old Leighlin, County Carlow, in 1 ...

(1785–1840), William Sharp Macleay (1792–1865), William Swainson

William Swainson Fellow of the Linnean Society, FLS, Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (8 October 1789 – 6 December 1855), was an English ornithologist, Malacology, malacologist, Conchology, conchologist, entomologist and artist.

Life

Swains ...

, and others. The idea was that nature followed a "rule of five" with five groups nested hierarchically. Some had attempted a rule of four, but Johann Jakob Kaup

Johann Jakob von Kaup (10 April 1803 – 4 July 1873) was a German naturalist. A proponent of natural philosophy, he believed in an innate mathematical order in nature and he attempted biological classifications based on the Quinarian system. Kaup ...

(1803–1873) insisted that the number five was special, noting that other natural entities such as the senses also came in fives. He followed this idea and demonstrated his view of the order within the crow family. Where he failed to find five genera, he left a blank insisting that a new genus would be found to fill these gaps. These ideas were replaced by more complex "maps" of affinities in works by Hugh Edwin Strickland

Hugh Edwin Strickland (2 March 1811 – 14 September 1853) was an English geologist, ornithology, ornithologist, naturalist and systematist. Through the British Association, he proposed a series of rules for the nomenclature of organisms in zool ...

and Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was an English naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He independently conceived the theory of evolution through natural selection; his 1858 pap ...

. A major advance was made by Max Fürbringer

Max Carl Anton Fürbringer (January 30, 1846 – March 6, 1920) was a German anatomist, known for his anatomical investigations of vertebrates and especially for his studies in ornithology on avian morphology and classification. He was responsible ...

in 1888, who established a comprehensive phylogeny of birds based on anatomy, morphology, distribution, and biology. This was developed further by Hans Gadow

Hans Friedrich Gadow (8 March 1855 – 16 May 1928) was a German-born ornithologist who worked in Britain. His work on the classification of birds based on anatomical and morphological characters was influential and made use of by Alexander Wetmo ...

and others.

The Galapagos finch

The true finches are small to medium-sized passerine birds in the family Fringillidae. Finches generally have stout conical bills adapted for eating seeds and nuts and often have colourful plumage. They occupy a great range of habitats where the ...

es were especially influential in the development of Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

's theory of evolution. His contemporary Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was an English naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He independently conceived the theory of evolution through natural selection; his 1858 pap ...

also noted these variations and the geographical separations between different forms leading to the study of biogeography

Biogeography is the study of the species distribution, distribution of species and ecosystems in geography, geographic space and through evolutionary history of life, geological time. Organisms and biological community (ecology), communities o ...

. Wallace was influenced by the work of Philip Lutley Sclater

Philip Lutley Sclater (4 November 1829 – 27 June 1913) was an English lawyer and zoologist. In zoology, he was an expert ornithologist, and identified the main zoogeographic regions of the world. He was Secretary of the Zoological Society ...

on the distribution patterns of birds.

For Darwin, the problem was how species arose from a common ancestor, but he did not attempt to find rules for delineation of species. The

For Darwin, the problem was how species arose from a common ancestor, but he did not attempt to find rules for delineation of species. The species problem

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

was tackled by the ornithologist Ernst Mayr

Ernst Walter Mayr ( ; ; 5 July 1904 – 3 February 2005) was a German-American evolutionary biologist. He was also a renowned Taxonomy (biology), taxonomist, tropical explorer, ornithologist, Philosophy of biology, philosopher of biology, and ...

, who was able to demonstrate that geographical isolation and the accumulation of genetic differences led to the splitting of species.

Early ornithologists were preoccupied with matters of species identification. Only systematics counted as true science and field studies were considered inferior through much of the 19th century. In 1901, Robert Ridgway

Robert Ridgway (July 2, 1850 – March 25, 1929) was an American ornithologist specializing in systematics. He was appointed in 1880 by Spencer Fullerton Baird, secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, to be the first full-time curator of birds ...

wrote in the introduction to ''The Birds of North and Middle America'' that:

This early idea that the study of living birds was merely recreation held sway until ecological theories became the predominant focus of ornithological studies. The study of birds in their habitats was particularly advanced in Germany with bird ringing

Bird ringing (UK) or bird banding (US) is the attachment of a small, individually numbered metal or plastic tag to the leg or wing of a wild bird to enable individual identification. This helps in keeping track of the movements of the bird an ...

stations established as early as 1903. By the 1920s, the '' Journal für Ornithologie'' included many papers on the behaviour, ecology, anatomy, and physiology, many written by Erwin Stresemann

Erwin Friedrich Theodor Stresemann (22 November 1889, in Dresden – 20 November 1972, in East Berlin) was a German naturalist and ornithologist. Stresemann was an ornithologist of extensive breadth who compiled one of the first and most comprehe ...

. Stresemann changed the editorial policy of the journal, leading both to a unification of field and laboratory studies and a shift of research from museums to universities. Ornithology in the United States continued to be dominated by museum studies of morphological variations, species identities, and geographic distributions, until it was influenced by Stresemann's student Ernst Mayr

Ernst Walter Mayr ( ; ; 5 July 1904 – 3 February 2005) was a German-American evolutionary biologist. He was also a renowned Taxonomy (biology), taxonomist, tropical explorer, ornithologist, Philosophy of biology, philosopher of biology, and ...

. In Britain, some of the earliest ornithological works that used the word ecology appeared in 1915. ''The Ibis'', however, resisted the introduction of these new methods of study, and no paper on ecology appeared until 1943. The work of David Lack on population ecology was pioneering. Newer quantitative approaches were introduced for the study of ecology and behaviour, and this was not readily accepted. For instance, Claud Ticehurst wrote:

David Lack's studies on population ecology sought to find the processes involved in the regulation of population based on the evolution of optimal clutch sizes. He concluded that population was regulated primarily by density-dependent controls, and also suggested that natural selection produces life-history traits that maximize the fitness of individuals. Others, such as Wynne-Edwards, interpreted population regulation as a mechanism that aided the "species" rather than individuals. This led to widespread and sometimes bitter debate on what constituted the "unit of selection". Lack also pioneered the use of many new tools for ornithological research, including the idea of using radar

Radar is a system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), direction ( azimuth and elevation angles), and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It is a radiodetermination method used to detect and track ...

to study bird migration.

Birds were also widely used in studies of the niche hypothesis and Georgii Gause's competitive exclusion principle. Work on resource partitioning and the structuring of bird communities through competition were made by Robert MacArthur

Robert Helmer MacArthur (April 7, 1930 – November 1, 1972) was a Canadian-born American ecologist who made a major impact on many areas of community and population ecology. He is considered to be one of the founders of ecology.

Early life ...

. Patterns of biodiversity

Biodiversity is the variability of life, life on Earth. It can be measured on various levels. There is for example genetic variability, species diversity, ecosystem diversity and Phylogenetics, phylogenetic diversity. Diversity is not distribut ...

also became a topic of interest. Work on the relationship of the number of species to area and its application in the study of island biogeography

Insular biogeography or island biogeography is a field within biogeography that examines the factors that affect the species richness and diversification of isolated natural communities. The theory was originally developed to explain the pattern ...

was pioneered by E. O. Wilson

Edward Osborne Wilson (June 10, 1929 – December 26, 2021) was an American biologist, naturalist, ecologist, and entomologist known for developing the field of sociobiology.

Born in Alabama, Wilson found an early interest in nature and frequ ...

and Robert MacArthur

Robert Helmer MacArthur (April 7, 1930 – November 1, 1972) was a Canadian-born American ecologist who made a major impact on many areas of community and population ecology. He is considered to be one of the founders of ecology.

Early life ...

. These studies led to the development of the discipline of landscape ecology

Landscape ecology is the science of studying and improving relationships between ecological processes in the environment and particular ecosystems. This is done within a variety of landscape scales, development spatial patterns, and organizatio ...

.

John Hurrell Crook studied the behaviour of weaverbirds and demonstrated the links between ecological conditions, behaviour, and social systems. Principles from

John Hurrell Crook studied the behaviour of weaverbirds and demonstrated the links between ecological conditions, behaviour, and social systems. Principles from economics

Economics () is a behavioral science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interac ...

were introduced to the study of biology by Jerram L. Brown in his work on explaining territorial behaviour. This led to more studies of behaviour that made use of cost-benefit analyses. The rising interest in sociobiology

Sociobiology is a field of biology that aims to explain social behavior in terms of evolution. It draws from disciplines including psychology, ethology, anthropology, evolution, zoology, archaeology, and population genetics. Within the study of ...

also led to a spurt of bird studies in this area.

The study of imprinting behaviour in ducks and geese by Konrad Lorenz

Konrad Zacharias Lorenz (Austrian ; 7 November 1903 – 27 February 1989) was an Austrian zoology, zoologist, ethology, ethologist, and ornithologist. He shared the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Nikolaas Tinbergen and Karl von ...

and the studies of instinct in herring gull Herring gull is a common name for several birds in the genus ''Larus'', all formerly treated as a single species.

Three species are still combined in some taxonomies:

* American herring gull (''Larus smithsonianus'') - North America

* European h ...

s by Nicolaas Tinbergen led to the establishment of the field of ethology

Ethology is a branch of zoology that studies the behavior, behaviour of non-human animals. It has its scientific roots in the work of Charles Darwin and of American and German ornithology, ornithologists of the late 19th and early 20th cen ...

. The study of learning became an area of interest and the study of bird songs has been a model for studies in neuroethology. The study of hormones and physiology in the control of behaviour has also been aided by bird models. These have helped in finding the proximate causes of circadian and seasonal cycles. Studies on migration have attempted to answer questions on the evolution of migration, orientation, and navigation.

The growth of genetics and the rise of molecular biology led to the application of the gene-centered view of evolution

The gene-centered view of evolution, gene's eye view, gene selection theory, or selfish gene theory holds that adaptive evolution occurs through the differential survival of competing genes, increasing the allele frequency of those alleles wh ...

to explain avian phenomena. Studies on kinship and altruism, such as helpers, became of particular interest. The idea of inclusive fitness

Inclusive fitness is a conceptual framework in evolutionary biology first defined by W. D. Hamilton in 1964. It is primarily used to aid the understanding of how social traits are expected to evolve in structured populations. It involves partit ...

was used to interpret observations on behaviour and life history, and birds were widely used models for testing hypotheses based on theories postulated by W. D. Hamilton

William Donald Hamilton (1 August 1936 – 7 March 2000) was a British evolutionary biologist, recognised as one of the most significant evolutionary theorists of the 20th century. Hamilton became known for his theoretical work expounding a ...

and others.

The new tools of molecular biology changed the study of bird systematics, which changed from being based on phenotype

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology (physical form and structure), its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological propert ...

to the underlying genotype

The genotype of an organism is its complete set of genetic material. Genotype can also be used to refer to the alleles or variants an individual carries in a particular gene or genetic location. The number of alleles an individual can have in a ...

. The use of techniques such as DNA–DNA hybridization

In genomics, DNA–DNA hybridization is a molecular biology technique that measures the degree of genetic similarity between DNA sequences. It is used to determine the genetic distance between two organisms and has been used extensively in phylo ...

to study evolutionary relationships was pioneered by Charles Sibley

Charles Gald Sibley (August 7, 1917 – April 12, 1998) was an American ornithologist and molecular biologist. He had an immense influence on the scientific classification of birds, and the work that Sibley initiated has substantially altered our u ...

and Jon Edward Ahlquist

Jon Edward Ahlquist (27 July 1944 –7 May 2020Jon Edw ...

, resulting in what is called the Sibley–Ahlquist taxonomy. These early techniques have been replaced by newer ones based on mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA and mDNA) is the DNA located in the mitochondrion, mitochondria organelles in a eukaryotic cell that converts chemical energy from food into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial DNA is a small portion of the D ...

sequences and molecular phylogenetics

Molecular phylogenetics () is the branch of phylogeny that analyzes genetic, hereditary molecular differences, predominantly in DNA sequences, to gain information on an organism's evolutionary relationships. From these analyses, it is possible to ...

approaches that make use of computational procedures for sequence alignment

In bioinformatics, a sequence alignment is a way of arranging the sequences of DNA, RNA, or protein to identify regions of similarity that may be a consequence of functional, structural biology, structural, or evolutionary relationships between ...

, construction of phylogenetic tree

A phylogenetic tree or phylogeny is a graphical representation which shows the evolutionary history between a set of species or taxa during a specific time.Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA. In ...

s, and calibration of molecular clock

The molecular clock is a figurative term for a technique that uses the mutation rate of biomolecules to deduce the time in prehistory when two or more life forms diverged. The biomolecular data used for such calculations are usually nucleot ...

s to infer evolutionary relationships. Molecular techniques are also widely used in studies of avian population biology

The term population biology has been used with different meanings.

In 1971, Edward O. Wilson ''et al''. used the term in the sense of applying mathematical models to population genetics, community ecology, and population dynamics. Alan Hasting ...

and ecology.

Rise to popularity

The use of field glasses ortelescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, Absorption (electromagnetic radiation), absorption, or Reflection (physics), reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally, it was an optical instrument using len ...

s for bird observation began in the 1820s and 1830s, with pioneers such as J. Dovaston (who also pioneered in the use of bird feeders), but instruction manuals did not begin to insist on the use of optical aids such as "a first-class telescope" or "field glass" until the 1880s.

The rise of field guides for the identification of birds was another major innovation. The early guides such as Thomas Bewick's two-volume guide and William Yarrell's three-volume guide were cumbersome, and mainly focused on identifying specimens in the hand. The earliest of the new generation of field guides was prepared by Florence Merriam, sister of

The rise of field guides for the identification of birds was another major innovation. The early guides such as Thomas Bewick's two-volume guide and William Yarrell's three-volume guide were cumbersome, and mainly focused on identifying specimens in the hand. The earliest of the new generation of field guides was prepared by Florence Merriam, sister of Clinton Hart Merriam

Clinton Hart Merriam (December 5, 1855 – March 19, 1942) was an American zoologist, mammalogist, ornithologist, entomologist, ecologist, ethnographer, geographer, natural history, naturalist and physician. He was commonly known as the "father o ...

, the mammalogist. This was published in 1887 in a series ''Hints to Audubon Workers: Fifty Birds and How to Know Them'' in Grinnell's ''Audubon Magazine

''Audubon'' is the flagship journal of the National Audubon Society. It is profusely illustrated and focuses on subjects related to nature, with a special emphasis on birds. New issues are published bi-monthly for society members. An active bl ...

''. These were followed by new field guides,

from the pioneering illustrated handbooks of Frank Chapman to the classic '' Field Guide to the Birds'' by Roger Tory Peterson

Roger Tory Peterson (August 28, 1908 – July 28, 1996) was an American natural history, naturalist, Conservationist (biology), conservationist, citizen scientist ornithology, ornithologist, artist and illustrator, educator, and a founder of th ...

in 1934, to '' Birds of the West Indies'' published in 1936 by Dr. James Bond - the same who inspired the amateur ornithologist Ian Fleming

Ian Lancaster Fleming (28 May 1908 – 12 August 1964) was a British writer, best known for his postwar ''James Bond'' series of spy novels. Fleming came from a wealthy family connected to the merchant bank Robert Fleming & Co., and his ...

in naming his famous literary spy.

The interest in birdwatching

Birdwatching, or birding, is the observing of birds, either as a recreational activity or as a form of citizen science. A birdwatcher may observe by using their naked eye, by using a visual enhancement device such as binoculars or a telescop ...

grew in popularity in many parts of the world, and the possibility for amateurs to contribute to biological studies was soon realized. As early as 1916, Julian Huxley

Sir Julian Sorell Huxley (22 June 1887 – 14 February 1975) was an English evolutionary biologist, eugenicist and Internationalism (politics), internationalist. He was a proponent of natural selection, and a leading figure in the mid-twentiet ...

wrote a two-part article in ''The Auk

''Ornithology'', formerly ''The Auk'' and ''The Auk: Ornithological Advances'', is a peer-reviewed scientific journal and the official publication of the American Ornithological Society (AOS). It was established in 1884 and is published quarterly ...

'', noting the tensions between amateurs and professionals, and suggested the possibility that the "vast army of bird lovers and bird watchers could begin providing the data scientists needed to address the fundamental problems of biology." The amateur ornithologist Harold F. Mayfield

Harold Ford Mayfield (25 March 1911 – 27 January 2007) was an American business executive and amateur ornithologist who made a major study of Kirtland's warbler and worked for the preservation of their breeding areas. During his study of the war ...

noted that the field was also funded by non-professionals. He noted that in 1975, 12% of the papers in American ornithology journals were written by persons who were not employed in biology related work.

Organizations were started in many countries, and these grew rapidly in membership, most notable among them being the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) is a Charitable_organization#United_Kingdom, charitable organisation registered in Charity Commission for England and Wales, England and Wales and in Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator, ...

(RSPB) in Britain and the Audubon Society

The National Audubon Society (Audubon; ) is an American non-profit environmental organization dedicated to conservation of birds and their habitats. Located in the United States and incorporated in 1905, Audubon is one of the oldest of such orga ...

in the US, which started in 1885. Both these organizations were started with the primary objective of conservation. The RSPB, born in 1889, grew from a small Croydon

Croydon is a large town in South London, England, south of Charing Cross. Part of the London Borough of Croydon, a Districts of England, local government district of Greater London; it is one of the largest commercial districts in Greater Lond ...

-based group of women, including Eliza Phillips, Etta Lemon

Margaretta "Etta" Louisa Lemon (; 22 November 1860 – 8 July 1953) was an English bird Conservation movement, conservationist and a founding member of what is now the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB).

She was born into ...

, Catherine Hall and Hannah Poland. Calling themselves the "Fur, Fin, and Feather Folk", the group met regularly and took a pledge "to refrain from wearing the feathers of any birds not killed for the purpose of food, the ostrich

Ostriches are large flightless birds. Two living species are recognised, the common ostrich, native to large parts of sub-Saharan Africa, and the Somali ostrich, native to the Horn of Africa.

They are the heaviest and largest living birds, w ...

only exempted." The organization did not allow men as members initially, avenging a policy of the British Ornithologists' Union

The British Ornithologists' Union (BOU) aims to encourage the study of birds (ornithology) around the world in order to understand their biology and aid their conservation. The BOU was founded in 1858 by Professor Alfred Newton, Henry Baker ...

to keep out women. Unlike the RSPB, which was primarily conservation oriented, the British Trust for Ornithology

The British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) is an organisation founded in 1932 for the study of birds in the British Isles. The William, Prince of Wales, Prince of Wales has been patron since October 2020.

History

Beginning

In 1931 Max Nicholson ...

was started in 1933 with the aim of advancing ornithological research. Members were often involved in collaborative ornithological projects. These projects have resulted in atlases which detail the distribution of bird species across Britain. In Canada, citizen scientist Elsie Cassels studied migratory birds and was involved in establishing Gaetz Lakes bird sanctuary. In the United States, the Breeding Bird Surveys, conducted by the United States Geological Survey

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), founded as the Geological Survey, is an agency of the U.S. Department of the Interior whose work spans the disciplines of biology, geography, geology, and hydrology. The agency was founded on Mar ...

, have also produced atlases with information on breeding densities and changes in the density and distribution over time. Other volunteer collaborative ornithology projects were subsequently established in other parts of the world.

Techniques

The tools and techniques of ornithology are varied, and new inventions and approaches are quickly incorporated. The techniques may be broadly dealt under the categories of those that are applicable to specimens and those that are used in the field, but the classification is rough and many analysis techniques are usable both in the laboratory and field or may require a combination of field and laboratory techniques.Collections

The earliest approaches to modern bird study involved the collection of eggs, a practice known as

The earliest approaches to modern bird study involved the collection of eggs, a practice known as oology

Oology (; also oölogy) is a branch of ornithology studying bird eggs, Bird nest, nests and breeding behaviour. The word is derived from the Greek ''oion'', meaning egg. Oology can also refer to the hobby of collecting wild birds' eggs, sometime ...

. While collecting became a pastime for many amateurs, the labels associated with these early egg collections made them unreliable for the serious study of bird breeding. To preserve eggs, a tiny hole was made and the contents extracted. This technique became standard with the invention of the blow drill around 1830. Egg collection is no longer popular; however, historic museum collections have been of value in determining the effects of pesticide

Pesticides are substances that are used to control pests. They include herbicides, insecticides, nematicides, fungicides, and many others (see table). The most common of these are herbicides, which account for approximately 50% of all p ...

s such as DDT

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, commonly known as DDT, is a colorless, tasteless, and almost odorless crystalline chemical compound, an organochloride. Originally developed as an insecticide, it became infamous for its environmental impacts. ...

on physiology. Museum bird collections

Bird collections are curated repositories of scientific Biological specimen, specimens consisting of birds and their parts. They are a research resource for ornithology, the science of birds, and for other scientific disciplines in which informa ...

continue to act as a resource for taxonomic studies.

arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol As and atomic number 33. It is a metalloid and one of the pnictogens, and therefore shares many properties with its group 15 neighbors phosphorus and antimony. Arsenic is not ...

to prevent fungal and insect (mostly dermestid) attack. Arsenic, being toxic, was replaced by less-toxic borax

The BORAX Experiments were a series of safety experiments on boiling water nuclear reactors conducted by Argonne National Laboratory in the 1950s and 1960s at the National Reactor Testing Station in eastern Idaho.

. Amateur and professional collectors became familiar with these skinning techniques and started sending in their skins to museums, some of them from distant locations. This led to the formation of huge collections of bird skins in museums in Europe and North America. Many private collections were also formed. These became references for comparison of species, and the ornithologists at these museums were able to compare species from different locations, often places that they themselves never visited. Morphometrics

Morphometrics (from Greek μορΦή ''morphe'', "shape, form", and -μετρία ''metria'', "measurement") or morphometry refers to the quantitative analysis of ''form'', a concept that encompasses size and shape. Morphometric analyses are co ...

of these skins, particularly the lengths of the tarsus, bill, tail, and wing became important in the descriptions of bird species. These skin collections have been used in more recent times for studies on molecular phylogenetics

Molecular phylogenetics () is the branch of phylogeny that analyzes genetic, hereditary molecular differences, predominantly in DNA sequences, to gain information on an organism's evolutionary relationships. From these analyses, it is possible to ...

by the extraction of ancient DNA

Ancient DNA (aDNA) is DNA isolated from ancient sources (typically Biological specimen, specimens, but also environmental DNA). Due to degradation processes (including Crosslinking of DNA, cross-linking, deamination and DNA fragmentation, fragme ...

. The importance of type specimens in the description of species make skin collections a vital resource for systematic ornithology. However, with the rise of molecular techniques, establishing the taxonomic status of new discoveries, such as the Bulo Burti boubou (''Laniarius liberatus'', no longer a valid species) and the Bugun liocichla (''Liocichla bugunorum''), using blood, DNA and feather samples as the holotype

A holotype (Latin: ''holotypus'') is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of s ...

material, has now become possible.

Other methods of preservation include the storage of specimens in spirit. Such wet specimens have special value in physiological and anatomical study, apart from providing better quality of DNA for molecular studies. Freeze drying

Freeze drying, also known as lyophilization or cryodesiccation, is a low temperature dehydration process that involves freezing the product and lowering pressure, thereby removing the ice by sublimation. This is in contrast to dehydration by ...

of specimens is another technique that has the advantage of preserving stomach contents and anatomy, although it tends to shrink, making it less reliable for morphometrics.

In the field

The study of birds in the field was helped enormously by improvements in optics. Photography made it possible to document birds in the field with great accuracy. High-power spotting scopes today allow observers to detect minute morphological differences that were earlier possible only by examination of the specimen "in the hand". The capture and marking of birds enable detailed studies of life history. Techniques for capturing birds are varied and include the use of bird liming for perching birds,

The capture and marking of birds enable detailed studies of life history. Techniques for capturing birds are varied and include the use of bird liming for perching birds, mist net

Mist nets are nets used to capture wild birds and bats. They are used by hunters and poachers to catch and kill animals, but also by ornithologists and chiropterologists for banding and other research projects. Mist nets are typically made of ...

s for woodland birds, cannon netting for open-area flocking birds, the '' bal-chatri'' trap for raptors, decoys and funnel traps for water birds.

The bird in the hand may be examined and

The bird in the hand may be examined and measurements

Measurement is the quantification of attributes of an object or event, which can be used to compare with other objects or events.

In other words, measurement is a process of determining how large or small a physical quantity is as compared to ...

can be made, including standard lengths and weights. Feather moult and skull ossification provide indications of age and health. Sex can be determined by examination of anatomy in some sexually nondimorphic species. Blood samples may be drawn to determine hormonal conditions in studies of physiology, identify DNA markers for studying genetics and kinship in studies of breeding biology and phylogeography. Blood may also be used to identify pathogens and arthropod-borne viruses. Ectoparasite

Parasitism is a Symbiosis, close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives (at least some of the time) on or inside another organism, the Host (biology), host, causing it some harm, and is Adaptation, adapted str ...

s may be collected for studies of coevolution and zoonoses

A zoonosis (; plural zoonoses) or zoonotic disease is an infectious disease of humans caused by a pathogen (an infectious agent, such as a virus, bacterium, parasite, fungi, or prion) that can jump from a non-human vertebrate to a human. When h ...

. In many cryptic species, measurements (such as the relative lengths of wing feathers in warblers) are vital in establishing identity.Mark and recapture

Mark and recapture is a method commonly used in ecology to estimate an animal population's size where it is impractical to count every individual. A portion of the population is captured, marked, and released. Later, another portion will be captu ...

techniques make demographic

Demography () is the statistics, statistical study of human populations: their size, composition (e.g., ethnic group, age), and how they change through the interplay of fertility (births), mortality (deaths), and migration.

Demographic analy ...

studies possible. Ringing has traditionally been used in the study of migration. In recent times, satellite transmitters provide the ability to track migrating birds in near-real time.

Techniques for estimating population density

Population density (in agriculture: Standing stock (disambiguation), standing stock or plant density) is a measurement of population per unit land area. It is mostly applied to humans, but sometimes to other living organisms too. It is a key geog ...

include point counts, transect

A transect is a path along which one counts and records occurrences of the objects of study (e.g. plants).