Human nature comprises the fundamental

disposition

A disposition is a quality of character, a habit, a preparation, a state of readiness, or a tendency to act in a specified way.

The terms dispositional belief and occurrent belief refer, in the former case, to a belief that is held in the mind b ...

s and characteristics—including ways of

thinking

In their most common sense, the terms thought and thinking refer to cognitive processes that can happen independently of sensory stimulation. Their most paradigmatic forms are judging, reasoning, concept formation, problem solving, and delibe ...

,

feeling

According to the '' APA Dictionary of Psychology'', a feeling is "a self-contained phenomenal experience"; feelings are "subjective, evaluative, and independent of the sensations, thoughts, or images evoking them". The term ''feeling'' is closel ...

, and

acting

Acting is an activity in which a story is told by means of its enactment by an actor who adopts a character—in theatre, television, film, radio, or any other medium that makes use of the mimetic mode.

Acting involves a broad range of sk ...

—that

human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are Hominidae, great apes characterized by their Prehistory of nakedness and clothing ...

s are said to have

naturally. The term is often used to denote the

essence

Essence () has various meanings and uses for different thinkers and in different contexts. It is used in philosophy and theology as a designation for the property (philosophy), property or set of properties or attributes that make an entity the ...

of

humankind

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are great apes characterized by their hairlessness, bipedalism, and high intelligen ...

, or what it '

means

Means may refer to:

* Means LLC, an anti-capitalist media worker cooperative

* Means (band), a Christian hardcore band from Regina, Saskatchewan

* Means, Kentucky, a town in the US

* Means (surname)

* Means Johnston Jr. (1916–1989), US Navy ...

' to be human. This usage has proven to be controversial in that there is dispute as to whether or not such an essence actually exists.

Arguments about human nature have been a central focus of

philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

for centuries and the concept continues to provoke lively philosophical debate.

While both concepts are distinct from one another, discussions regarding human nature are typically related to those regarding the comparative importance of

gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

s and

environment in

human development Human development may refer to:

* Development of the human body

** This includes physical developments such as growth, and also development of the brain

* Developmental psychology

* Development theory

* Human development (economics)

* Human Develo ...

(i.e., '

nature versus nurture

Nature versus nurture is a long-standing debate in biology and society about the relative influence on human beings of their genetics, genetic inheritance (nature) and the environmental conditions of their development (nurture). The alliterative ex ...

'). Accordingly, the concept also continues to play a role in academic fields, such as both the

natural

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the laws, elements and phenomena of the physical world, including life. Although humans are part ...

and the

social science

Social science (often rendered in the plural as the social sciences) is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of societies and the relationships among members within those societies. The term was formerly used to refer to the ...

s, and

philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, in which various theorists claim to have yielded insight into human nature. Human nature is traditionally contrasted with human attributes that vary among

societies

A society () is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. ...

, such as those associated with specific

culture

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

s.

The concept of nature as a standard by which to make judgments is traditionally said to have begun in

Greek philosophy

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC. Philosophy was used to make sense of the world using reason. It dealt with a wide variety of subjects, including astronomy, epistemology, mathematics, political philosophy, ethics, metaphysic ...

, at least in regard to its heavy influence on

Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

and

Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

ern languages and perspectives.

[ Gilden, Hilail, ed. 1989. "Progress or Return." In ''An Introduction to Political Philosophy: Ten Essays by Leo Strauss''. Detroit: ]Wayne State University Press

Wayne State University Press (or WSU Press) is a university press that is part of Wayne State University

Wayne State University (WSU) is a public university, public research university in Detroit, Michigan, United States. Founded in 186 ...

. By

late antiquity

Late antiquity marks the period that comes after the end of classical antiquity and stretches into the onset of the Early Middle Ages. Late antiquity as a period was popularized by Peter Brown (historian), Peter Brown in 1971, and this periodiza ...

and

medieval times

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and t ...

, the particular approach that came to be dominant was that of

Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

's

teleology

Teleology (from , and )Partridge, Eric. 1977''Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English'' London: Routledge, p. 4187. or finalityDubray, Charles. 2020 912Teleology. In ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' 14. New York: Robert Appleton ...

, whereby human nature was believed to exist somehow independently of individuals, causing humans to simply become what they become. This, in turn, has been understood as also demonstrating a special connection between human nature and

divinity

Divinity (from Latin ) refers to the quality, presence, or nature of that which is divine—a term that, before the rise of monotheism, evoked a broad and dynamic field of sacred power. In the ancient world, divinity was not limited to a single ...

, whereby human nature is understood in terms of

final

Final, Finals or The Final may refer to:

*Final examination or finals, a test given at the end of a course of study or training

*Final (competition), the last or championship round of a sporting competition, match, game, or other contest which d ...

and

formal

Formal, formality, informal or informality imply the complying with, or not complying with, some set of requirements ( forms, in Ancient Greek). They may refer to:

Dress code and events

* Formal wear, attire for formal events

* Semi-formal atti ...

causes Causes, or causality, is the relationship between one event and another. It may also refer to:

* Causes (band), an indie band based in the Netherlands

* Causes (company)

Causes is a for-profit civic-technology app and website that enables users ...

. More specifically, this perspective believes that nature itself (or a nature-creating divinity) has intentions and goals, including the goal for humanity to live naturally. Such understandings of human nature see this nature as an "idea", or "

form

Form is the shape, visual appearance, or configuration of an object. In a wider sense, the form is the way something happens.

Form may also refer to:

*Form (document), a document (printed or electronic) with spaces in which to write or enter dat ...

" of a human. However, the existence of this invariable and

metaphysical

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of h ...

human nature is subject of much historical debate, continuing into modern times.

Against Aristotle's notion of a fixed human nature, the relative malleability of man has been argued especially strongly in recent centuries—firstly by early

modernists

Modernism was an early 20th-century movement in literature, visual arts, and music that emphasized experimentation, abstraction, and subjective experience. Philosophy, politics, architecture, and social issues were all aspects of this moveme ...

such as

Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan (Hobbes book), Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory. He is considered t ...

,

John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

and

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Republic of Geneva, Genevan philosopher (''philosophes, philosophe''), writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment through ...

. In his ''

Emile, or On Education

''Emile, or On Education'' () is a treatise on the nature of education and on the nature of man written by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who considered it to be the "best and most important" of all his writings. Due to a section of the book entitled "Pr ...

'', Rousseau wrote: "We do not know what our nature permits us to be." Since the early 19th century, such thinkers as

Darwin,

Freud

Sigmund Freud ( ; ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies seen as originating from conflicts in t ...

,

Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

,

Kierkegaard,

Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche became the youngest pro ...

, and

Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was a French philosopher, playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and literary critic, considered a leading figure in 20th-century French ph ...

, as well as

structuralists

Structuralism is an intellectual current and methodological approach, primarily in the social sciences, that interprets elements of human culture by way of their relationship to a broader system. It works to uncover the structural patterns tha ...

and

postmodernists

Postmodernism encompasses a variety of artistic, cultural, and philosophical movements that claim to mark a break from modernism. They have in common the conviction that it is no longer possible to rely upon previous ways of depicting the worl ...

more generally, have also sometimes argued against a fixed or ''innate'' human nature.

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

's ''

theory of evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, resulting in certai ...

'' has particularly changed the shape of the discussion, supporting the proposition that the ancestors of modern humans were not like humans today. As in much of modern science, such theories seek to explain with little or no recourse to metaphysical causation. They can be offered to explain the origins of human nature and its underlying mechanisms, or to demonstrate capacities for change and diversity which would arguably violate the concept of a fixed human nature.

Classical Greek philosophy

Philosophy in

classical Greece

Classical Greece was a period of around 200 years (the 5th and 4th centuries BC) in ancient Greece,The "Classical Age" is "the modern designation of the period from about 500 B.C. to the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C." ( Thomas R. Mar ...

is the ultimate origin of the

Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

conception of the nature of things.

According to

Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

, the philosophical study of human nature itself originated with

Socrates

Socrates (; ; – 399 BC) was a Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher from Classical Athens, Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and as among the first moral philosophers of the Ethics, ethical tradition ...

, who turned philosophy from study of the

heaven

Heaven, or the Heavens, is a common Religious cosmology, religious cosmological or supernatural place where beings such as deity, deities, angels, souls, saints, or Veneration of the dead, venerated ancestors are said to originate, be throne, ...

s to study of the human things. Though leaving no written works, Socrates is said to have studied the question of how a person should best live. It is clear from the works of his students,

Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

and

Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; ; 355/354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian. At the age of 30, he was elected as one of the leaders of the retreating Ancient Greek mercenaries, Greek mercenaries, the Ten Thousand, who had been ...

, and also from the accounts of Aristotle (Plato's student), that Socrates was a

rationalist and believed that the best life and the life most suited to human nature involved

reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing valid conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, religion, scien ...

ing. The

Socratic school was the dominant surviving influence in philosophical discussion in the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, amongst

Islamic

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

,

Christian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

, and

Jewish philosophers

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly inte ...

.

The

human soul

''Human Soul'' is an album by the English musician Graham Parker.

The album peaked at No. 165 on the ''Billboard'' 200. Parker supported the album by touring with Dave Edmunds's Rock and Roll Revue.

Production

''Human Soul'' was originally div ...

in the works of Plato and Aristotle has a nature that is divided in a specifically human way. One part is specifically human and rational, being further divided into (1) a part which is rational on its own; and (2) a spirited part which can understand reason. Other parts of the soul are home to desires or passions similar to those found in animals. In both Aristotle and Plato's ideas, spiritedness (''

thumos

''Thumos'', also spelled ''thymos'' (), is the Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek concept of (as in "a spirited stallion" or "spirited debate"). The word indicates a physical association with breath or blood and is also used to express the human desi ...

'') is distinguished from the other passions (). The proper function of the "rational" was to rule the other parts of the soul, helped by spiritedness. By this account, using one's reason is the best way to live, and philosophers are the highest types of humans.

Aristotle

Aristotle—Plato's most famous student—made some of the most famous and influential statements about human nature. In his works, apart from using a similar scheme of a divided human soul, some clear statements about human nature are made:

* In contrast to other animals, humans have reason or language (''logos'') in their soul (''psyche''). According to Aristotle this means that the work (''ergos'') of a human is the actualization (''

energeia'') of the soul in accordance with reason. Based upon this reasoning, the

medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

followers of Aristotle formulated the doctrine that man is the "

Rational Animal

The term rational animal (Latin: ''animal rationale'' or ''animal rationabile'') refers to a classical definition of humanity or human nature, associated with Aristotelianism.

History

While the Latin term itself originates in scholasticism, it r ...

".

* Man is a conjugal animal: An animal that is born to couple in adulthood. In doing so, man builds a household (''

oikos

''Oikos'' ( ; : ) was, in Ancient Greece, two related but distinct concepts: the family and the family's house. Its meaning shifted even within texts.

The ''oikos'' was the basic unit of society in most Greek city-states. For regular Attic_G ...

'') and, in more successful cases, a

clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, a clan may claim descent from a founding member or apical ancestor who serves as a symbol of the clan's unity. Many societie ...

or small village run upon

patriarchal

Patriarchy is a social system in which positions of authority are primarily held by men. The term ''patriarchy'' is used both in anthropology to describe a family or clan controlled by the father or eldest male or group of males, and in fem ...

lines. However, humans naturally tend to connect their villages into cities (poleis), which are more self-sufficient and complete.

* Man is a political animal: An animal with an

innate propensity to develop more complex communities (i.e. the size of a city or town), with systems of

law-making

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior, with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a science and as the art ...

and a

division of labor

The division of labour is the separation of the tasks in any economic system or organisation so that participants may specialise (Departmentalization, specialisation). Individuals, organisations, and nations are endowed with or acquire specialis ...

. This type of community is different in kind from a

large family, and requires the use of

human reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing valid conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, religion, scien ...

. Cities should not be run by a patriarch, like a village.

* Man is a

mimetic

Mimesis (; , ''mīmēsis'') is a term used in literary criticism and philosophy that carries a wide range of meanings, including ''imitatio'', imitation, Similarity (philosophy), similarity, receptivity, representation (arts), representation, m ...

animal: Man loves to use his

imagination

Imagination is the production of sensations, feelings and thoughts informing oneself. These experiences can be re-creations of past experiences, such as vivid memories with imagined changes, or completely invented and possibly fantastic scenes ...

, and not only to make laws and run

town council

A town council, city council or municipal council is a form of local government for small municipalities.

Usage of the term varies under different jurisdictions.

Republic of Ireland

In 2002, 49 urban district councils and 26 town commissi ...

s: "

enjoy looking at accurate likenesses of things which are themselves painful to see, obscene beasts, for instance, and corpses.…

hereason why we enjoy seeing likenesses is that, as we look, we learn and infer what each is, for instance, 'that is so and so.

For Aristotle, reason is not only what is most special about humanity compared to other animals, but it is also what we were meant to achieve at our best. Much of Aristotle's description of human nature is still influential today. However, the particular teleological idea that humans are "meant" or intended to be something has become much less popular in

modern times.

Theory of four causes

For the Socratics, human nature, and all natures, are

metaphysical

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of h ...

concepts. Aristotle developed the standard presentation of this approach with his ''theory of

four causes

The four causes or four explanations are, in Aristotelianism, Aristotelian thought, categories of questions that explain "the why's" of something that exists or changes in nature. The four causes are the: #Material, material cause, the #Formal, f ...

'', whereby every living thing exhibits four aspects, or "causes:"

#

matter

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic pa ...

(''

hyle'');

#

form

Form is the shape, visual appearance, or configuration of an object. In a wider sense, the form is the way something happens.

Form may also refer to:

*Form (document), a document (printed or electronic) with spaces in which to write or enter dat ...

(''

eidos

Eidos may refer to:

* Eidos (philosophy), a Greek term meaning "form" "essence", "type" or "species"

* Eidos Interactive, a British video game publisher

** SCi Entertainment Group, its parent, which was briefly renamed Eidos Ltd.

** Eidos Hungary ...

'');

#

effect

Effect may refer to:

* A result or change of something

** List of effects

** Cause and effect, an idiom describing causality

Pharmacy and pharmacology

* Drug effect, a change resulting from the administration of a drug

** Therapeutic effect, ...

(''kinoun''); and

#

end

End, END, Ending, or ENDS may refer to:

End Mathematics

*End (category theory)

* End (topology)

* End (graph theory)

* End (group theory) (a subcase of the previous)

* End (endomorphism) Sports and games

*End (gridiron football)

*End, a division ...

(''

telos

Telos (; ) is a term used by philosopher Aristotle to refer to the final cause of a natural organ or entity, or of human art. ''Telos'' is the root of the modern term teleology, the study of purposiveness or of objects with a view to their aims, ...

'').

For example, an

oak tree

An oak is a hardwood tree or shrub in the genus ''Quercus'' of the Fagaceae, beech family. They have spirally arranged leaves, often with lobed edges, and a nut called an acorn, borne within a cup. The genus is widely distributed in the Northe ...

is made of plant cells (matter); grows from an acorn (effect); exhibits the nature of oak trees (form); and grows into a fully mature oak tree (end). According to Aristotle, human nature is an example of a formal cause. Likewise, our 'end' is to become a ''fully actualized human being'' (including fully actualizing the mind). Aristotle suggests that the

human intellect (, ''noûs''), while "smallest in bulk", is the most significant part of the

human psyche and should be cultivated above all else. The cultivation of learning and intellectual growth of the philosopher is thereby also the happiest and least painful life.

Chinese philosophy

Confucianism

Human nature is a central question in

Chinese philosophy

Chinese philosophy (Simplified Chinese characters, simplified Chinese: 中国哲学; Traditional Chinese characters, traditional Chinese: 中國哲學) refers to the philosophical traditions that originated and developed within the historical ...

.

[Tang, Paul C., and N. Basafa. 1988. "Human Nature in Chinese Thought: A Wittgensteinian Treatment." ''Proceedings of the 12th International Wittgenstein Symposium 1988''. ]International Wittgenstein Symposium

The International Wittgenstein Symposium is an international conference dedicated to the work of Ludwig Wittgenstein and its relationship to philosophy and science. It is sponsored by the Austrian Ludwig Wittgenstein Society.

History

In 1976, t ...

. From the

Song dynasty

The Song dynasty ( ) was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 960 to 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song, who usurped the throne of the Later Zhou dynasty and went on to conquer the rest of the Fiv ...

, the theory of innate goodness of human beings became dominant in

Confucianism

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China, and is variously described as a tradition, philosophy, Religious Confucianism, religion, theory of government, or way of li ...

.

[Yen, Hung-Chung. 2015. "Human Nature and Learning in Ancient China." Pp. 19–43 in ''Education as Cultivation in Chinese Culture''. Singapore: ]Springer

Springer or springers may refer to:

Publishers

* Springer Science+Business Media, aka Springer International Publishing, a worldwide publishing group founded in 1842 in Germany formerly known as Springer-Verlag.

** Springer Nature, a multinationa ...

. It is in contrast to the theory of innate evil advocated by

Xunzi.

Mencius

Mencius

Mencius (孟子, ''Mèngzǐ'', ; ) was a Chinese Confucian philosopher, often described as the Second Sage () to reflect his traditional esteem relative to Confucius himself. He was part of Confucius's fourth generation of disciples, inheriting ...

argues that human nature is good.

He understands human nature as the innate tendency to an ideal state that's expected to be formed under the right conditions.

Therefore, humans have the capacity to be good, even though they are not all good.

According to Mencian theory, human nature contains four beginnings () of

morality

Morality () is the categorization of intentions, Decision-making, decisions and Social actions, actions into those that are ''proper'', or ''right'', and those that are ''improper'', or ''wrong''. Morality can be a body of standards or principle ...

.

It consists of a sense of

compassion

Compassion is a social feeling that motivates people to go out of their way to relieve the physical, mental, or emotional pains of others and themselves. Compassion is sensitivity to the emotional aspects of the suffering of others. When based ...

that develops into

benevolence

Benevolence or Benevolent may refer to:

* Benevolent (band)

* Benevolence (phrenology), a faculty in the discredited theory of phrenology

* "Benevolent" (song), a song by Tory Lanez

* Benevolence (tax), a forced loan imposed by English kings from ...

(), a sense of

shame

Shame is an unpleasant self-conscious emotion often associated with negative self-evaluation; motivation to quit; and feelings of pain, exposure, distrust, powerlessness, and worthlessness.

Definition

Shame is a discrete, basic emotion, d ...

and

disdain

In colloquial usage, contempt usually refers to either the act of despising, or having a general lack of respect for something. This set of emotions generally produces maladaptive behaviour. Other authors define contempt as a negative emotio ...

that develops into

righteousness

Righteousness is the quality or state of "being morally right or justifiable" rooted in religious or divine law with a broader spectrum of moral correctness, justice, and virtuous living as dictated by a higher authority or set of spiritual beli ...

(), a sense of

respect

Respect, also called esteem, is a positive feeling or deferential action shown towards someone or something considered important or held in high esteem or regard. It conveys a sense of admiration for good or valuable qualities. It is also th ...

and

courtesy

Courtesy (from the word , from the 12th century) is gentle politeness and courtly manners. In the Middle Ages in Europe, the behaviour expected of the nobility was compiled in courtesy books.

History

The apex of European courtly culture was ...

that develops into

propriety

Etiquette ( /ˈɛtikɛt, -kɪt/) can be defined as a set of norms of personal behavior in polite society, usually occurring in the form of an ethical code of the expected and accepted social behaviors that accord with the conventions and n ...

(), and a sense of

right

Rights are law, legal, social, or ethics, ethical principles of freedom or Entitlement (fair division), entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal sy ...

and

wrong

A wrong or wrength (from Old English – 'crooked') is an act that is illegal or immoral. Legal wrongs are usually quite clearly defined in the law of a state or jurisdiction. They can be divided into civil wrongs and crimes (or ''criminal of ...

that develops into

wisdom

Wisdom, also known as sapience, is the ability to apply knowledge, experience, and good judgment to navigate life’s complexities. It is often associated with insight, discernment, and ethics in decision-making. Throughout history, wisdom ha ...

().

The beginnings of morality are characterized by both

affective

Affect, in psychology, is the underlying experience of feeling, emotion, attachment, or mood. It encompasses a wide range of emotional states and can be positive (e.g., happiness, joy, excitement) or negative (e.g., sadness, anger, fear, dis ...

motivations and

intuitive

Intuition is the ability to acquire knowledge without recourse to conscious reasoning or needing an explanation. Different fields use the word "intuition" in very different ways, including but not limited to: direct access to unconscious knowledg ...

judgments, such as what's right and wrong,

deferential, respectful, or disdainful.

In Mencius' view, goodness is the result of the development of innate tendencies toward the virtues of benevolence, righteousness, wisdom, and propriety.

The tendencies are manifested in

moral emotions

Moral emotions are a variety of social emotions that are involved in forming and communicating moral judgments and decisions, and in motivating behavioral responses to one's own and others' moral behavior. As defined by Jonathan Haidt, moral emo ...

for every human being.

Reflection () upon the manifestations of the four beginnings leads to the development of virtues.

It brings recognition that virtue takes precedence over satisfaction, but a lack of reflection inhibits moral development.

In other words, humans have a constitution comprising

emotional predispositions that direct them to goodness.

Mencius also addresses the question why the capacity for evil is not grounded in human nature.

If an individual becomes bad, it is not the result of his or her constitution, as their constitution contains the emotional predispositions that direct to goodness, but a matter of injuring or not fully developing his or her constitution in the appropriate direction.

He recognizes desires of the senses as natural predispositions distinct from the four beginnings.

People can be misled and led astray by their desires if they do not engage their ethical motivations.

He therefore places responsibility on people to reflect on the manifestations of the four beginnings.

Herein, it is not the function of ears and eyes but the function of the heart to reflect, as sensory organs are associated with sensual desires but the heart is the seat of feeling and thinking. Mencius considers core virtues—benevolence, righteousness, propriety, and wisdom—as internal qualities that humans originally possess, so people can not attain full satisfaction by solely pursuits of self-interest due to their innate morality.

Wong (2018) underscores that Mencius' characterization of human nature as good means that "it contains predispositions to feel and act in morally appropriate ways and to make intuitive normative judgments that can with the right nurturing conditions give human beings guidance as to the proper emphasis to be given to the desires of the senses."

Xunzi

Xunzi understands human nature as the basic faculties, capacities, and desires that people have from birth.

He views it as the animalistic instincts exhibited by humans before education, which includes greed, idleness, and desires.

[ He suggests that people can not get rid of these instincts, so the existence of this human nature necessitates education and cultivation of goodness.][

Xunzi argues that human nature is evil and that any goodness is the result of human activity.]Ivanhoe

''Ivanhoe: A Romance'' ( ) by Walter Scott is a historical novel published in three volumes, in December 1819, as one of the Waverley novels. It marked a shift away from Scott's prior practice of setting stories in Scotland and in the more ...

(1994), means that humans do not have a conception of morality and therefore must acquire it through learning, lest destructive and alienating competition inevitably arises from human desire.

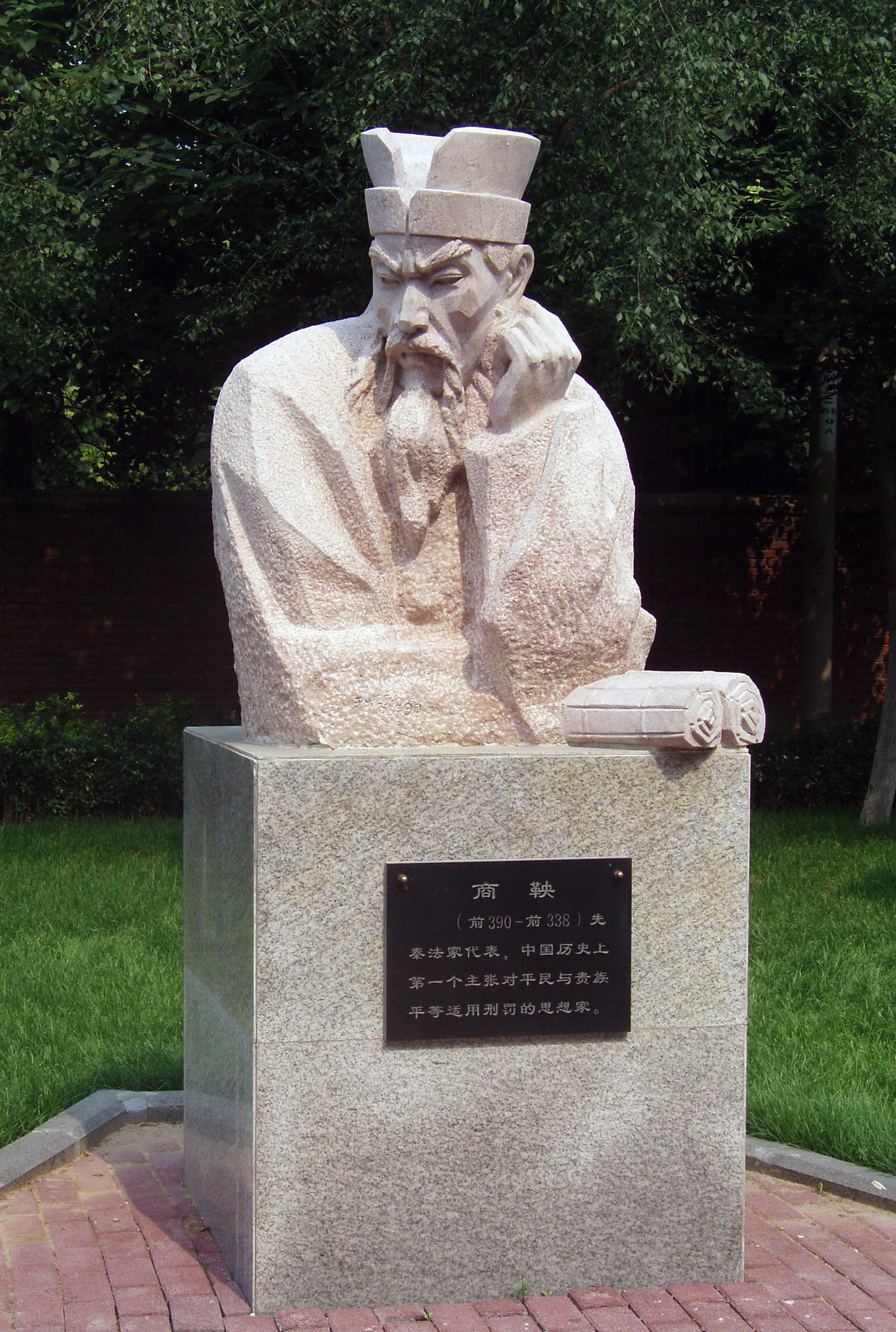

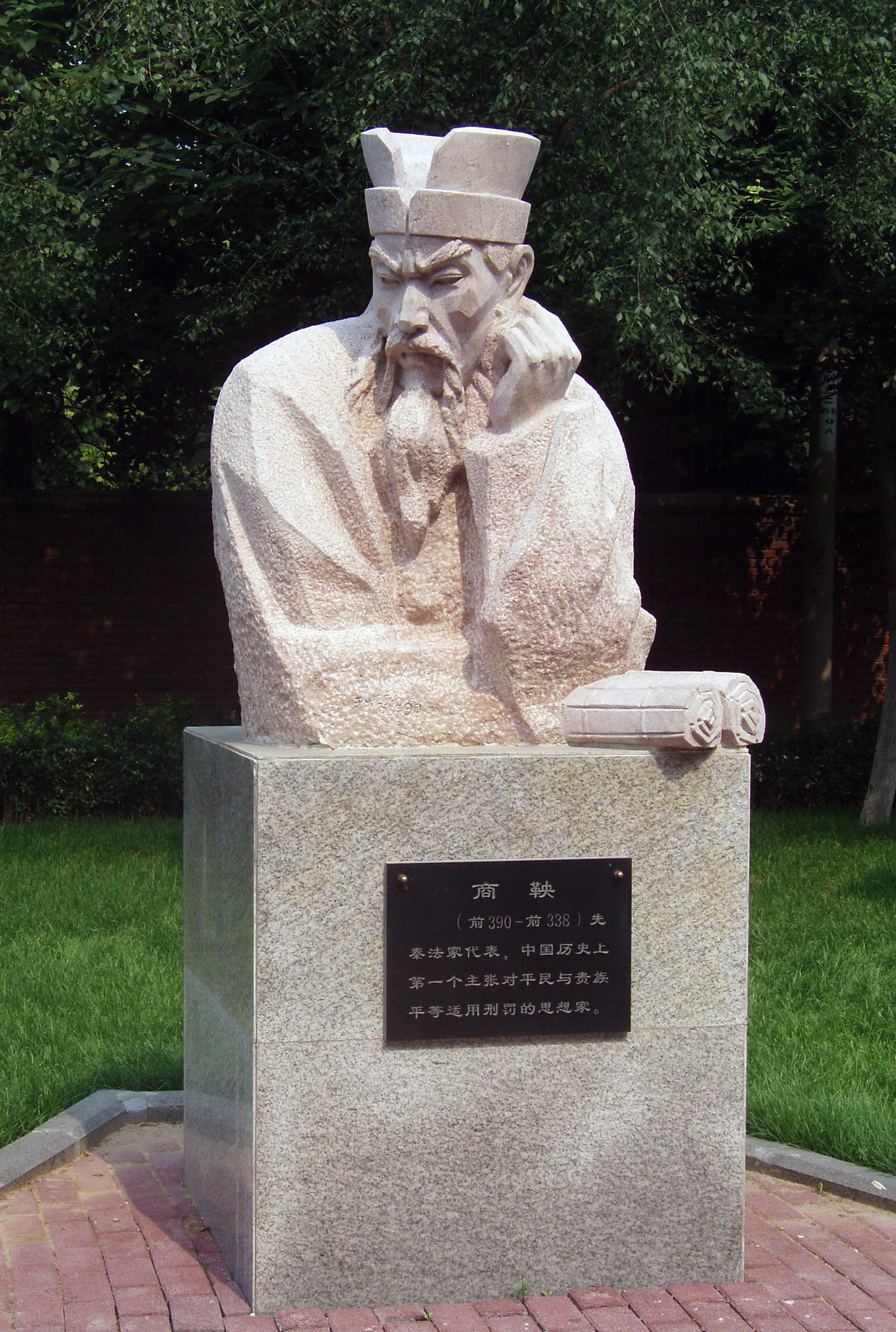

Legalism

Legalism is based on a distrust of human nature.

Legalism is based on a distrust of human nature.[ It dismisses the possibility that people can overcome their selfishness and considers the possibility that people can be driven by moral commitment to be exceptionally rare.]Han Fei

Han Fei (233 BC), also known as Han Feizi, was a Chinese Legalist philosopher and statesman during the Warring States period. He was a prince of the state of Han.

Han Fei is often considered the greatest representative of Legalism for th ...

emphasize clear and impersonal norms and standards (such as laws, regulations, and rules) as the basis to maintain order.[ He argues that competition for external goods produces disorder during times of ]scarcity

In economics, scarcity "refers to the basic fact of life that there exists only a finite amount of human and nonhuman resources which the best technical knowledge is capable of using to produce only limited maximum amounts of each economic good. ...

due to this nature.[ If there is no scarcity, humans may treat each other well, but they will not become nice; it is that they do not turn to disorder when scarcity is absent.][ Han Fei also argues that people are all motivated by their unchanging selfish core to want whatever advantage they can gain from whomever they can gain such advantage, which especially comes to expression in situations where people can act with ]impunity

Impunity is the ability to act with exemption from punishments, losses, or other negative consequences. In the international law of human rights, impunity is failure to bring perpetrators of human rights violations to justice and, as such, itsel ...

.[

Legalists posit that the selfishness in human nature can be an asset rather than a threat to a state.]political system

In political science, a political system means the form of Political organisation, political organization that can be observed, recognised or otherwise declared by a society or state (polity), state.

It defines the process for making official gov ...

that presupposes this human selfishness is the only viable system.power

Power may refer to:

Common meanings

* Power (physics), meaning "rate of doing work"

** Engine power, the power put out by an engine

** Electric power, a type of energy

* Power (social and political), the ability to influence people or events

Math ...

struggle.[ They view the usage of reward and punishment as effective political controls, as it is in human nature to have likes and dislikes.]Shang Yang

Shang Yang (; c. 390 – 338 BC), also known as Wei Yang () and originally surnamed Gongsun, was a Politician, statesman, chancellor and reformer of the Qin (state), State of Qin. Arguably the "most famous and most influential statesman of the ...

, it is crucial to investigate the disposition of people in terms of rewards and penalties when a law is established.[

In Han Fei's view, the only realistic option is a political system that produces equivalents of '']junzi

The word junzi ( or "Son of the Vassal, or Monarch") is a Chinese philosophical term often translated as "gentleman", "superior person",Sometimes "exemplary person". Paul R. Goldin translates it "noble man" in an attempt to capture both its earl ...

'' (君子, who are virtuous exemplars in Confucianism) but not actual ''junzi''.[ This does not mean, however, that Han Fei makes a distinction between ''seeming'' and ''being'' good, as he does not entertain the idea that humans are good.][ Rather, as human nature is constituted by self-interest, he argues that humans can be shaped behaviorally to yield social order if it is in the individual's own self-interest to abide by the norms (i.e., different interests are aligned to each other and the ]social good

In philosophy, economics, and political science, the common good (also commonwealth, common weal, general welfare, or public benefit) is either what is shared and beneficial for all or most members of a given community, or alternatively, what is ...

), which is most efficiently ensured if the norms are publicly and impartially enforced.

Medieval and Renaissance philosophy

Medieval conceptions of man were particularly stimulated by two sources, viz. the

Medieval conceptions of man were particularly stimulated by two sources, viz. the Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

and the Classical philosophical tradition. In Scripture, two passages especially provided the foundation of a dynamic anthropology: Gen 1, 26 and Wis 2, 23 where it is said that man was created in the “image of God”. No theologian

Theology is the study of religious belief from a religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of ...

could dispense with a reflection on the foundations and consequences of the vision of man implied in this statement. While Bernard of Clairvaux

Bernard of Clairvaux, Cistercians, O.Cist. (; 109020 August 1153), venerated as Saint Bernard, was an abbot, Mysticism, mystic, co-founder of the Knights Templar, and a major leader in the reform of the Benedictines through the nascent Cistercia ...

considered that man was the image of God by inamissible free will

Free will is generally understood as the capacity or ability of people to (a) choice, choose between different possible courses of Action (philosophy), action, (b) exercise control over their actions in a way that is necessary for moral respon ...

(''De gratia et libero arbitrio'', IV, 9; IX, 28), the majority of authors envisaged a likeness between God and man that was based on reason. Thus, according to Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

, man can be called ''imago Dei'' by reason of his intellectual Nature, for “intellectual nature imitates God especially in that God knows himself and loves himself” (''Summa theologiae

The ''Summa Theologiae'' or ''Summa Theologica'' (), often referred to simply as the ''Summa'', is the best-known work of Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), a scholastic theologian and Doctor of the Church. It is a compendium of all of the main the ...

'' I a, q. 93, a. 4). According to Bonaventure

Bonaventure ( ; ; ; born Giovanni di Fidanza; 1221 – 15 July 1274) was an Italian Catholic Franciscan bishop, Cardinal (Catholic Church), cardinal, Scholasticism, scholastic theologian and philosopher.

The seventh Minister General ( ...

, all created being is a vestige of God, while beings endowed with intelligence are images of God since God is present in acts of memory

Memory is the faculty of the mind by which data or information is encoded, stored, and retrieved when needed. It is the retention of information over time for the purpose of influencing future action. If past events could not be remembe ...

, intellect

Intellect is a faculty of the human mind that enables reasoning, abstraction, conceptualization, and judgment. It enables the discernment of truth and falsehood, as well as higher-order thinking beyond immediate perception. Intellect is dis ...

and will

Will may refer to:

Common meanings

* Will and testament, instructions for the disposition of one's property after death

* Will (philosophy), or willpower

* Will (sociology)

* Will, volition (psychology)

* Will, a modal verb - see Shall and will

...

as their principle.

By an original fusion of Christology

In Christianity, Christology is a branch of Christian theology, theology that concerns Jesus. Different denominations have different opinions on questions such as whether Jesus was human, divine, or both, and as a messiah what his role would b ...

and the doctrine of man as image of God, Meister Eckhart

Eckhart von Hochheim ( – ), commonly known as Meister Eckhart (), Master Eckhart or Eckehart, claimed original name Johannes Eckhart, wished to go beyond the traditional distinction between the Son, image of the Father, and man created in the image of God. The motif of man as a microcosm in which the universe is reflected is of ancient origin. This understanding of the human being enjoyed immense success in the 12th century

The 12th century is the period from 1101 to 1200 in accordance with the Julian calendar.

In the history of European culture, this period is considered part of the High Middle Ages and overlaps with what is often called the Golden Age' of the ...

when authors as different as Bernardus Silvestris

Bernardus Silvestris, also known as Bernard Silvestris and Bernard Silvester, was a medieval Platonist philosopher and poet of the 12th century.

Biography

Little is known about Bernardus's life. In the nineteenth century, it was assumed that Bern ...

and Godfrey of Saint Victor made use of it. Hildegard of Bingen

Hildegard of Bingen Benedictines, OSB (, ; ; 17 September 1179), also known as the Sibyl of the Rhine, was a German Benedictines, Benedictine abbess and polymath active as a writer, composer, philosopher, Christian mysticism, mystic, visiona ...

and Honorius Augustodunensis

Honorius Augustodunensis (c. 1080 – c. 1140), commonly known as Honorius of Autun, was a 12th-century Christian theologian.

Life

Augustodunensis said that he is ''Honorius Augustodunensis ecclesiae presbyter et scholasticus''. "Augustodunensis" ...

developed a whole system of correspondences between “the little world” and the universe, the macrocosm, correspondences that also played a far from negligible role in medieval medicine and the doctrine of the four temperaments

The four temperament theory is a proto-psychological theory which suggests that there are four fundamental personality types: sanguine, choleric, melancholic, and phlegmatic. Most formulations include the possibility of mixtures among the types ...

.

The origin of the definition of man as a “rational animal

The term rational animal (Latin: ''animal rationale'' or ''animal rationabile'') refers to a classical definition of humanity or human nature, associated with Aristotelianism.

History

While the Latin term itself originates in scholasticism, it r ...

” also went back to Antiquity. The problem of the relation between the Soul

The soul is the purported Mind–body dualism, immaterial aspect or essence of a Outline of life forms, living being. It is typically believed to be Immortality, immortal and to exist apart from the material world. The three main theories that ...

and the body which was implicitly contained in this definition, gave rise to very important debates after the arrival of Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

in the West and the Translation of Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

and Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

philosophical texts. The dualist

Dualism most commonly refers to:

* Mind–body dualism, a philosophical view which holds that mental phenomena are, at least in certain respects, not physical phenomena, or that the mind and the body are distinct and separable from one another

* P ...

position whose cause was brilliantly defended by Bonaventure stated that man was composed of two substances, the soul being joined to the body “as mover”. It is patent that the postulate of ontological autonomy of the soul, supposed in this position, accords easily with the religious belief in the immortality of the soul

Immortality is the concept of eternal life. Some species possess " biological immortality" due to an apparent lack of the Hayflick limit.

From at least the time of the ancient Mesopotamians, there has been a conviction that gods may be phy ...

. The Aristotelian doctrine of the soul as “act of the organic body” and hence as the form

Form is the shape, visual appearance, or configuration of an object. In a wider sense, the form is the way something happens.

Form may also refer to:

*Form (document), a document (printed or electronic) with spaces in which to write or enter dat ...

of the body seemed to pose more of a problem as a thesis on which to base immortality. In accepting Aristotelian hylomorphism

Hylomorphism is a philosophical doctrine developed by the Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle, which conceives every physical entity or being ('' ousia'') as a compound of matter (potency) and immaterial form (act), with the generic form as imm ...

, Thomas Aquinas insisted on the unity of the human composite. The intellective soul is hence the form by which “man is a being in act, a body, a living thing, an animal and a man” (''Summa theologiae'' I a, q. 76, a. 6, ad 1). By the act of intellection, which, in its exercise, is independent of the body, Thomas tried to demonstrate that the soul is capable of existing without the body: “Hence the intellectual principle, in other words the spirit, the intellect, possesses by itself an activity in which the body has no part. Now nothing can act by itself that does not exist by itself. … It remains that the human soul, i.e. the intellect, the spirit, is an incorporeal and subsistent reality” (''Summa theologiae'' I a, q. 75, a. 2). By the 14th century (William of Ockham

William of Ockham or Occam ( ; ; 9/10 April 1347) was an English Franciscan friar, scholastic philosopher, apologist, and theologian, who was born in Ockham, a small village in Surrey. He is considered to be one of the major figures of medie ...

, Jean Buridan

Jean Buridan (; ; Latin: ''Johannes Buridanus''; – ) was an influential 14thcentury French scholastic philosopher.

Buridan taught in the faculty of arts at the University of Paris for his entire career and focused in particular on logic and ...

), the philosophical proofs of the soul's immortality were contested, but the debate was particularly lively in the 15th and early 16th centuries. Marsilio Ficino

Marsilio Ficino (; Latin name: ; 19 October 1433 – 1 October 1499) was an Italian scholar and Catholic priest who was one of the most influential humanist philosophers of the early Italian Renaissance. He was an astrologer, a reviver of Neo ...

’s '' Platonic Theology'' (1474) can be understood as a vast defence of the immortality of the soul, while Pietro Pomponazzi

Pietro Pomponazzi (16 September 1462 – 18 May 1525) was an Italian philosopher. He is sometimes known by his Latin name, ''Petrus Pomponatius''.

Biography

Pietro Pomponazzi was born in Mantua and began his education there. He completed h ...

(† 1525) fought most vigorously against the very idea of any proof in favour of immortality.

The rediscovery of the Aristotelian corpus favoured the discussion of another anthropological formula. In his ''Politics

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

'' (I, 2; 1253 a 1-2), Aristotle advanced the idea that man was a “political animal”. This conception opened up the possibility of a political anthropology of which Marsilius of Padua

Marsilius of Padua (; born ''Marsilio Mainardi'', ''Marsilio de i Mainardini'' or ''Marsilio Mainardini''; – ) was an Italian scholar, trained in medicine, who practiced a variety of professions. He was also an important 14th-century pol ...

and Dante Alighieri

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

provide remarkable examples. Membership of the human community was perceived as a constitutive element of humanity. In this context, certain authors reflected on communication and discovered that language

Language is a structured system of communication that consists of grammar and vocabulary. It is the primary means by which humans convey meaning, both in spoken and signed language, signed forms, and may also be conveyed through writing syste ...

was also constitutive of humanity. It is proper to man, said Thomas Aquinas, to use words to express his thoughts: “It is true that the other animals communicate their passions, roughly, as the dog expresses his anger by barking … Hence, man is much more communicative towards others than any animal whatever that we see living gregariously, like the crane, the ant or the bee” (''De regno'', ch. 1). The theme of the dignity of man manifests yet another aspect of medieval anthropology. An astonishing expression of it appears in John Scotus Eriugena

John Scotus Eriugena, also known as Johannes Scotus Erigena, John the Scot or John the Irish-born ( – c. 877), was an Irish Neoplatonist philosopher, theologian and poet of the Early Middle Ages. Bertrand Russell dubbed him "the most ...

’s ''De divisione naturae

''De Divisione Naturae'' ("The Division of Nature") is the title given by Thomas Gale to his edition (1681) of the work originally titled by 9th-century theologian Johannes Scotus Eriugena ''Periphyseon''.''John Scotus Erigena'', ''The Age of B ...

'' (book IV) where it is said of man that “his substance is the notion by which he knows himself” ('' PL'', 122, 770A).

This optimism contrasts with the perspectives sketched out by Lotario dei Segni, the future Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III (; born Lotario dei Conti di Segni; 22 February 1161 – 16 July 1216) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 until his death on 16 July 1216.

Pope Innocent was one of the most power ...

, in the opusculum ''De Miseria Condicionis Humane

''De Miseria Condicionis Humane'' (''On the wretchedness of the human condition''), also known as ''Liber de contemptu mundi, sive De miseria humanae conditionis,'' is a twelfth-century religious text written in Latin by Cardinal Lotario dei Segn ...

'' (1195–119) which offers a striking picture of man's weaknesses and infirmities. When in 1452 Giannozzo Manetti

Giannozzo Manetti (1396–1459) was an Italian politician and diplomat from Florence, who was also a humanist scholar of the early Italian Renaissance and an anti-Semitic polemicist.

Manetti was the son of a wealthy merchant. His public career ...

eulogized the beauty and excellence of man, body and Soul, he wished to reply to the lamentation of Innocent, whose work had an immense success. Giovanni Pico della Mirandola

Giovanni Pico dei conti della Mirandola e della Concordia ( ; ; ; 24 February 146317 November 1494), known as Pico della Mirandola, was an Italian Renaissance nobleman and philosopher. He is famed for the events of 1486, when, at the age of 23, ...

too, in his celebrated ''Discourse on the dignity of man'', expounded a very high idea of man. Pico celebrated first the radical freedom

Freedom is the power or right to speak, act, and change as one wants without hindrance or restraint. Freedom is often associated with liberty and autonomy in the sense of "giving oneself one's own laws".

In one definition, something is "free" i ...

of man, who is capable of choosing himself, i.e. of giving himself his own essence: “I have given you neither a determined place, nor a face of your own, says the creator, nor any particular gift, O Adam, so that your place, your face and your gifts you may will, conquer and possess by yourself. Nature encloses other species in laws established by me. But you, whom no boundary limits, by your own free will, in whose hands I have placed you, define yourself.”

This anthropology, which has been celebrated as the beginning of modernity, is not in opposition to religion since this dignity of man belongs to him precisely because he is the image of God according to the biblical word. Yet, with an unprecedented intensity, Pico was able to give a luminous and powerful expression to this profound truth that “man outruns in advance all defined concept of man” ().

Christian theology

In Christian theology, there are two ways of "conceiving human nature:" The first is "spiritual, Biblical, and theistic"; and the second is "natural

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the laws, elements and phenomena of the physical world, including life. Although humans are part ...

, cosmical, and anti-theistic".[ Tulloch, John. 1876. ''Christian Doctrine of Sin''. Armstrong: Scribner.] The focus in this section is on the former. As William James

William James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher and psychologist. The first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States, he is considered to be one of the leading thinkers of the late 19th c ...

put it in his study of human nature from a religious perspective, "religion" has a "department of human nature".

Various views of human nature have been held by theologians. However, there are some "basic assertions" in all " biblical anthropology:"

# "Humankind has its origin in God, its creator."

# "Humans bear the 'image of God

The "image of God" (; ; ) is a concept and theological doctrine in Judaism and Christianity. It is a foundational aspect of Judeo-Christian belief with regard to the fundamental understanding of human nature. It stems from the primary text in Gen ...

'."

# Humans are "to rule the rest of creation".

The Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

contains no single "doctrine of human nature". Rather, it provides material for more philosophical descriptions of human nature. For example, Creation as found in the Book of Genesis

The Book of Genesis (from Greek language, Greek ; ; ) is the first book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. Its Hebrew name is the same as its incipit, first word, (In the beginning (phrase), 'In the beginning'). Genesis purpor ...

provides a theory on human nature.

''Catechism of the Catholic Church

The ''Catechism of the Catholic Church'' (; commonly called the ''Catechism'' or the ''CCC'') is a reference work that summarizes the Catholic Church's doctrine. It was Promulgation (Catholic canon law), promulgated by Pope John Paul II in 1992 ...

'', under the chapter "Dignity of the human person", provides an article about man as image of God, vocation to beatitude, freedom, human acts, passions, moral conscience, virtues, and sin.

Created human nature

As originally created, the Bible describes "two elements" in human nature: "the body and the breath or spirit of life breathed into it by God". By this was created a "living soul", meaning a "living person". According to Genesis 1

Genesis may refer to:

Religion

* Book of Genesis, the first book of the biblical scriptures of both Judaism and Christianity, describing the creation of the Earth and of humankind

* Genesis creation narrative, the first several chapters of the Bo ...

:27, this living person was made in the "image of God

The "image of God" (; ; ) is a concept and theological doctrine in Judaism and Christianity. It is a foundational aspect of Judeo-Christian belief with regard to the fundamental understanding of human nature. It stems from the primary text in Gen ...

". From the biblical perspective, "to be human is to bear the image of God."[ Hoekema, Anthony A. 1986. ''Created in God's Image''. Michigan: ]Eerdmans

William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company is a religious publishing house based in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Founded in 1911 by Dutch American William B. Eerdmans and still independently owned with William's daughter-in-law Anita Eerdmans as presid ...

.

Genesis does not elaborate the meaning of "the image of God", but scholars find suggestions. One is that being created in the image of God distinguishes human nature from that of the beasts. Another is that as God is "able to make decisions and rule" so humans made in God's image are "able to make decisions and rule". A third is that humankind possesses an inherent ability "to set goals" and move toward them.

Fallen human nature

By Adam

Adam is the name given in Genesis 1–5 to the first human. Adam is the first human-being aware of God, and features as such in various belief systems (including Judaism, Christianity, Gnosticism and Islam).

According to Christianity, Adam ...

's fall into sin, "human nature" became "corrupt", although it retains the image of God

The "image of God" (; ; ) is a concept and theological doctrine in Judaism and Christianity. It is a foundational aspect of Judeo-Christian belief with regard to the fundamental understanding of human nature. It stems from the primary text in Gen ...

. Both the Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

and the New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

teach that "sin is universal."Psalm 51

Psalm 51, one of the penitential psalms, is the 51st psalm of the Book of Psalms, beginning in English in the King James Version: "Have mercy upon me, O God". In the slightly different numbering system used in the Greek Septuagint and Latin V ...

:5 reads: "For behold I was conceived in iniquities; and in sins did my mother conceive me." Jesus taught that everyone is a "sinner naturally" because it is humanity's "nature and disposition to sin".Romans 7

Romans 7 is the seventh chapter of the Epistle to the Romans in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. It is authored by Paul the Apostle, while he was in Corinth in the mid-50s AD, with the help of an amanuensis (secretary), Tertius, who add ...

:18, speaks of his "sinful nature".

Such a "recognition that there is something wrong with the moral nature of man is found in all religions."Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced the development of Western philosop ...

coined a term for the assessment that all humans are born sinful: original sin

Original sin () in Christian theology refers to the condition of sinfulness that all humans share, which is inherited from Adam and Eve due to the Fall of man, Fall, involving the loss of original righteousness and the distortion of the Image ...

. Original sin is "the tendency to sin innate in all human beings". The doctrine of original sin is held by the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

and most mainstream Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

denominations, but rejected by the Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, officially the Orthodox Catholic Church, and also called the Greek Orthodox Church or simply the Orthodox Church, is List of Christian denominations by number of members, one of the three major doctrinal and ...

, which holds the similar doctrine of ancestral fault

Ancestral sin, generational sin, or ancestral fault (; ; ), is the doctrine that teaches that individuals inherit the divine judgement, judgement for the sin of their ancestors. It exists primarily as a concept in Mediterranean religions (e.g. in C ...

.

"The corruption of original sin extends to every aspect of human nature": to "reason and will" as well as to "appetites and impulses". This condition is sometimes called "total depravity

Total depravity (also called radical corruption or pervasive depravity) is a Protestant theological doctrine derived from the concept of original sin

Original sin () in Christian theology refers to the condition of sinfulness that all h ...

". Total depravity does not mean that humanity is as "thoroughly depraved" as it could become. Commenting on Romans 2:14, John Calvin

John Calvin (; ; ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French Christian theology, theologian, pastor and Protestant Reformers, reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of C ...

writes that all people have "some notions of justice and rectitude ... which are implanted by nature" all people.

Adam embodied the "whole of human nature" so when Adam sinned "all of human nature sinned." The Old Testament does not explicitly link the "corruption of human nature" to Adam's sin. However, the "universality of sin" implies a link to Adam. In the New Testament, Paul concurs with the "universality of sin". He also makes explicit what the Old Testament implied: the link between humanity's "sinful nature" and Adam's sin In Romans 5

Romans 5 is the fifth chapter of the Epistle to the Romans in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. It is authored by Paul the Apostle, while he was in Corinth in the mid-50s AD, with the help of an amanuensis (secretary), Tertius, who adds ...

:19, Paul writes, "through dam'sdisobedience humanity became sinful." Paul also applied humanity's sinful nature to himself: "there is nothing good in my sinful nature."

The theological "doctrine of original sin" as an inherent element of human nature is not based only on the Bible. It is in part a "generalization from obvious facts" open to empirical observation.

Empirical view

A number of experts on human nature have described the manifestations of original (i.e., the innate tendency to) sin as empirical facts.

* Biologist Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins (born 26 March 1941) is a British evolutionary biology, evolutionary biologist, zoologist, science communicator and author. He is an Oxford fellow, emeritus fellow of New College, Oxford, and was Simonyi Professor for the Publ ...

, in his ''The Selfish Gene

''The Selfish Gene'' is a 1976 book on evolution by ethologist Richard Dawkins that promotes the gene-centred view of evolution, as opposed to views focused on the organism and the group. The book builds upon the thesis of George C. Willia ...

'', states that "a predominant quality" in a successful surviving gene is "ruthless selfishness". Furthermore, "this gene selfishness will usually give rise to selfishness in individual behavior."

* Child psychologist Burton L. White finds a "selfish" trait in children from birth, a trait that expresses itself in actions that are "blatantly selfish".

* Sociologist William Graham Sumner

William Graham Sumner (October 30, 1840 – April 12, 1910) was an American clergyman, social scientist, and neoclassical liberal. He taught social sciences at Yale University, where he held the nation's first professorship in sociology and bec ...

finds it a fact that "everywhere one meets "fraud, corruption, ignorance, selfishness, and all the other vices of human nature". He enumerates "the vices and passions of human nature" as "cupidity, lust, vindictiveness, ambition, and vanity". Sumner finds such human nature to be universal: in all people, in all places, and in all stations in society.

* Psychiatrist Thomas Anthony Harris, on the basis of his "data at hand", observes "sin, or badness, or evil, or 'human nature', whatever we call the flaw in our species, is apparent in every person." Harris calls this condition "intrinsic badness" or "original sin".

Empirical discussion questioning the genetic exclusivity of such an intrinsic badness proposition is presented by researchers Elliott Sober

Elliott R. Sober (born 6 June 1948) is an American philosopher. He is noted for his work in philosophy of biology and general philosophy of science. Sober is Hans Reichenbach Professor and William F. Vilas Research Professor Emeritus in the Depar ...

and David Sloan Wilson

David Sloan Wilson (born 1949) is an American evolutionary biologist and a Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Biological Sciences and Anthropology at Binghamton University. He is a son of author Sloan Wilson, a co-founder of Evolution Institu ...

. In their book, ''Unto Others: The Evolution and Psychology of Unselfish Behavior'', they propose a theory of multilevel group selection

Group selection is a proposed mechanism of evolution in which natural selection acts at the level of the group, instead of at the level of the individual or gene.

Early authors such as V. C. Wynne-Edwards and Konrad Lorenz argued that the beha ...

in support of an inherent genetic "altruism

Altruism is the concern for the well-being of others, independently of personal benefit or reciprocity.

The word ''altruism'' was popularised (and possibly coined) by the French philosopher Auguste Comte in French, as , for an antonym of egoi ...

" in opposition to the original sin exclusivity for human nature.

20th-century liberal theology

Liberal theologians in the early 20th century described human nature as "basically good", needing only "proper training and education". But the above examples document the return to a "more realistic view" of human nature "as basically sinful and self-centered

Egocentrism refers to difficulty differentiating between self and other. More specifically, it is difficulty in accurately perceiving and understanding perspectives other than one's own.

Egocentrism is found across the life span: in infancy, ear ...

". Human nature needs "to be regenerated ... to be able to live the unselfish life".

Regenerated human nature

According to the Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writte ...

, "Adam's disobedience corrupted human nature" but God mercifully "regenerates". "Regeneration is a radical change" that involves a "renewal of our uman

Uman (, , ) is a city in Cherkasy Oblast, central Ukraine. It is located to the east of Vinnytsia. Located in the east of the historical region of Podolia, the city rests on the banks of the Umanka River. Uman serves as the administrative c ...

nature". Thus, to counter original sin, Christianity purposes "a complete transformation of individuals" by Christ.

The goal of Christ's coming is that fallen humanity might be "conformed to or transformed into the image of Christ who is the perfect image of God", as in 2 Corinthians 4:4. The New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

makes clear the "universal need" for regeneration. A sampling of biblical portrayals of regenerating human nature and the behavioral results follow.

:*being "transformed by the renewing of your minds" (Romans 12

Romans 12 is the twelfth chapter of the Epistle to the Romans in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. It is authored by Paul the Apostle, while he was in Corinth in the mid-50s AD, with the help of an amanuensis (secretary), Tertius, who ad ...

:2)

:*being transformed from one's "old self" (or "old man") into a "new self" (or "new man") ( Colossians 3:9–10)

:*being transformed from people who "hate others" and "are hard to get along with" and who are "jealous, angry, and selfish" to people who are "loving, happy, peaceful, patient, kind, good, faithful, gentle, and self-controlled" (Galatians 5

Galatians 5 is the fifth chapter of the Epistle to the Galatians in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. It is authored by Paul the Apostle for the churches in Galatia, written between AD 49–58. This chapter contains a discussion about cir ...

:20–23)

:*being transformed from looking "to your own interests" to looking "to the interests of others" ( Philippians 2:4)

Early modern philosophy

Although this new realism applied to the study of human life from the beginning—for example, in Machiavelli's works—the definitive argument for the final rejection of Aristotle was associated especially with Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England under King James I. Bacon argued for the importance of nat ...

. Bacon sometimes wrote as if he accepted the traditional four causes ("It is a correct position that "true knowledge is knowledge by causes." And causes again are not improperly distributed into four kinds: the material, the formal, the efficient, and the final") but he adapted these terms and rejected one of the three: But of these the final cause rather corrupts than advances the sciences, except such as have to do with human action. The discovery of the formal is despaired of. The efficient and the material (as they are investigated and received, that is, as remote causes, without reference to the latent process leading to the form) are but slight and superficial, and contribute little, if anything, to true and active science.

This line of thinking continued with René Descartes

René Descartes ( , ; ; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and Modern science, science. Mathematics was paramou ...

, whose new approach returned philosophy or science to its pre-Socratic